Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Motivation and Contributions

- 1.

- Existing security frameworks do not adequately account for temporal backdoor attacks that exploit sequential dependencies in financial transaction streams. Most defenses assume static or isolated threat models, overlooking coordinated multi-round adversarial strategies.

- 2.

- Current defense mechanisms are largely single-layered and static, focusing either on aggregation robustness or anomaly detection, without integrating multiple complementary layers that can collectively enhance resilience against adaptive attackers.

- 3.

- Few approaches incorporate dynamic coordination mechanisms to balance security and utility. Static thresholds or fixed strategies cannot adapt to changing adversarial intensity, heterogeneous client behaviors, and evolving network conditions.

- We formalize temporal backdoor threats in federated financial learning by characterizing attack strategies that exploit multi-period dependencies across training rounds.

- We design a multi-layer defense architecture that combines temporal behavior profiling, robust aggregation, and multi-scale verification to jointly enhance detection accuracy and resilience.

- We formulate defense coordination as an MDP problem and develop an RL-based policy using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to dynamically manage defense actions, balancing robustness and model performance.

- We validate DEFEND on multiple benchmark datasets (CIFAR-10, FEMNIST, MNIST) under varying degrees of heterogeneity and adversarial participation, demonstrating superior defense success rates and detection efficiency compared to state-of-the-art baselines.

2. Related Work

2.1. Federated Learning Security in Financial Systems

| Ref | [13] | [23] | [15] | [20] | [24] | [25] | [26] | [27] | [14] | [28] | [29] | Proposed work | |

| Feature | |||||||||||||

| Financial application domain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Federated learning framework | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Temporal attack detection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Multi-layer defense design | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| MDP/RL coordination | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

2.2. Temporal Attack Detection and Defense Mechanisms

2.3. Multi-Layer Defense and MDP-based Coordination

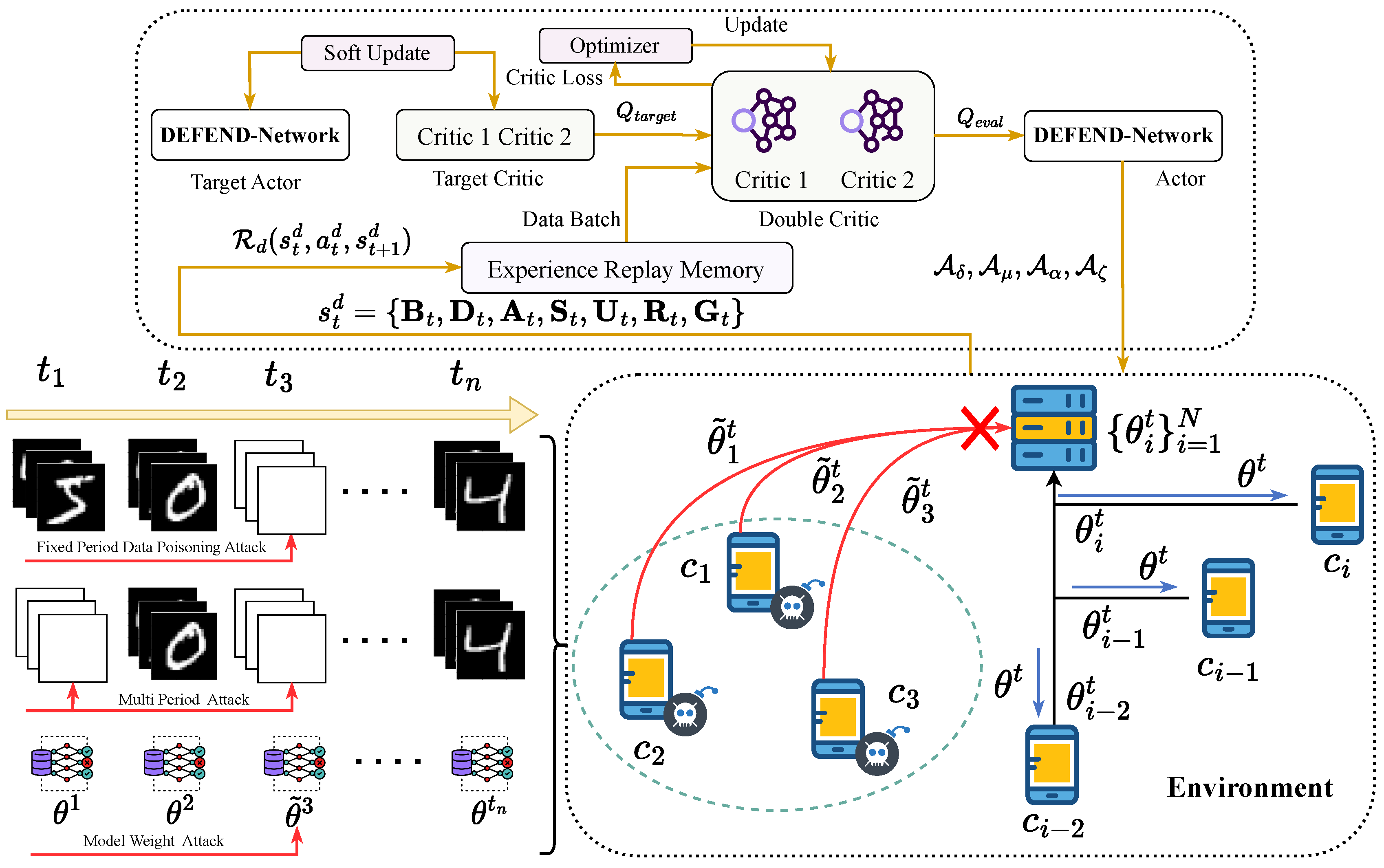

3. Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

3.2. Temporal Backdoor Attack Models

3.2.1. Fixed-Period Data Poisoning Attack

3.2.2. Multi-Period Data Poisoning Attack

3.2.3. Model Weight Poisoning Attack

3.3. Multi-Layer Defense Framework

3.3.1. Temporal Behavioral Analysis Layer

3.3.2. Robust Statistical Aggregation Layer

3.3.3. Multi-Scale Validation Layer

3.4. MDP Framework for Defense Coordination

3.4.1. Defense State Space Design

3.4.2. Defense Action Space Formulation

3.4.3. Defense Transition Dynamics

3.4.4. Defense Reward Function Design

3.4.5. Defense Policy Optimization

| Algorithm 1 DEFEND: DEep Federated Ensemble Network Defense | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

▹ Equation (12) |

|

▹ Equation (14)-(17) |

|

▹ Equation (18) |

|

▹ Equation (19) |

|

|

|

▹ Equation (36) |

|

▹ Equation (60) |

|

▹ Equation (48) |

|

▹ Equation (23) |

|

▹ Equation (24)-(25) |

|

▹ Equation (26) |

|

▹ Equation (28) |

|

▹ Equation (27) |

|

▹ Equation (30) |

|

▹ Equation (32) |

|

▹ Equation (31)-(33) |

|

|

|

▹ Equation (34) |

|

▹ Equation (29) |

|

|

|

▹ Equation (35) |

|

|

|

|

|

▹ Equation (55) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.2.1. Clean Accuracy under Defense

4.2.2. Defense Success Rate

4.2.3. Temporal Detection Efficiency

4.3. Implementation Details

5. Results

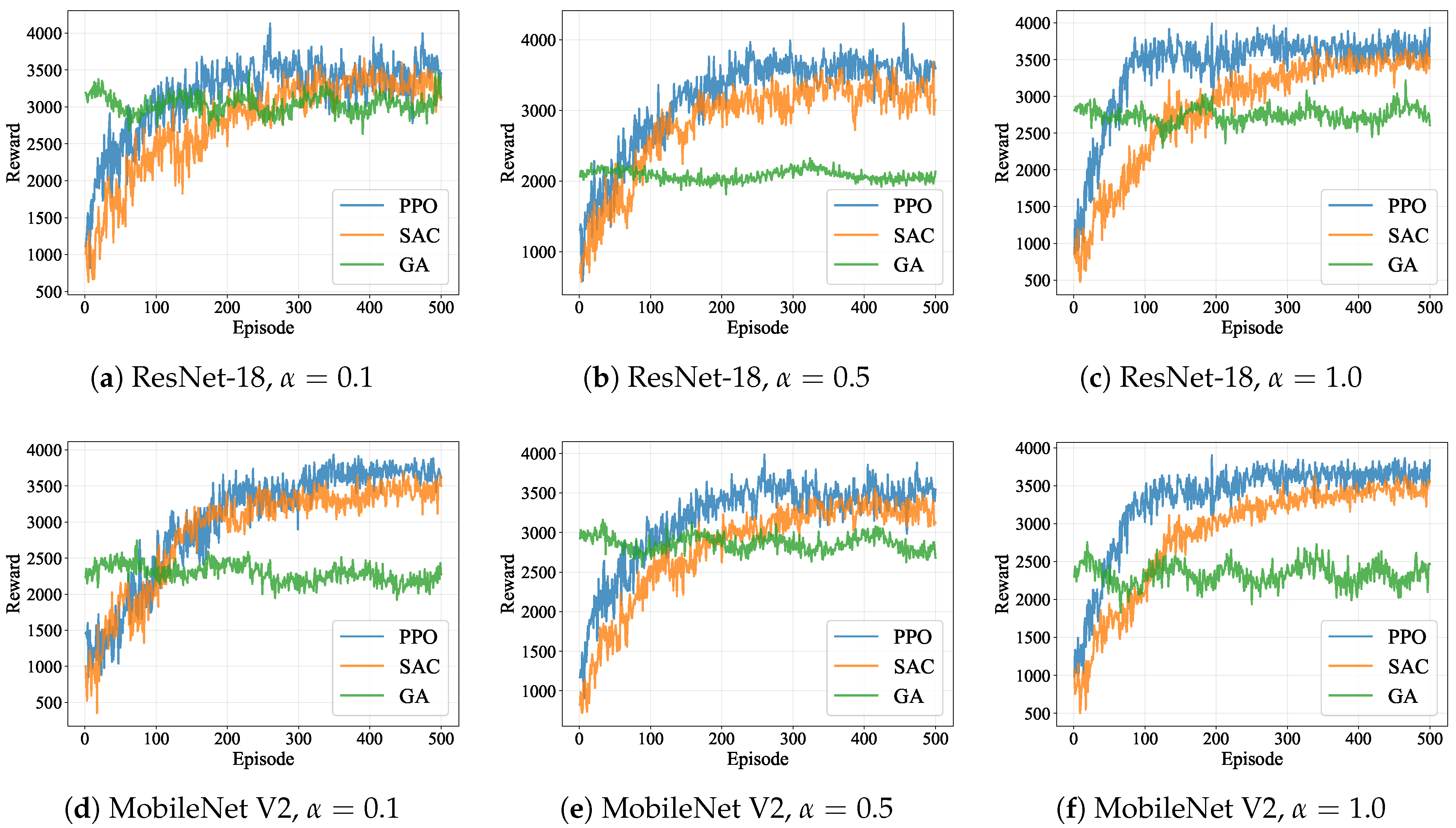

5.1. MDP Policy Learning Performance

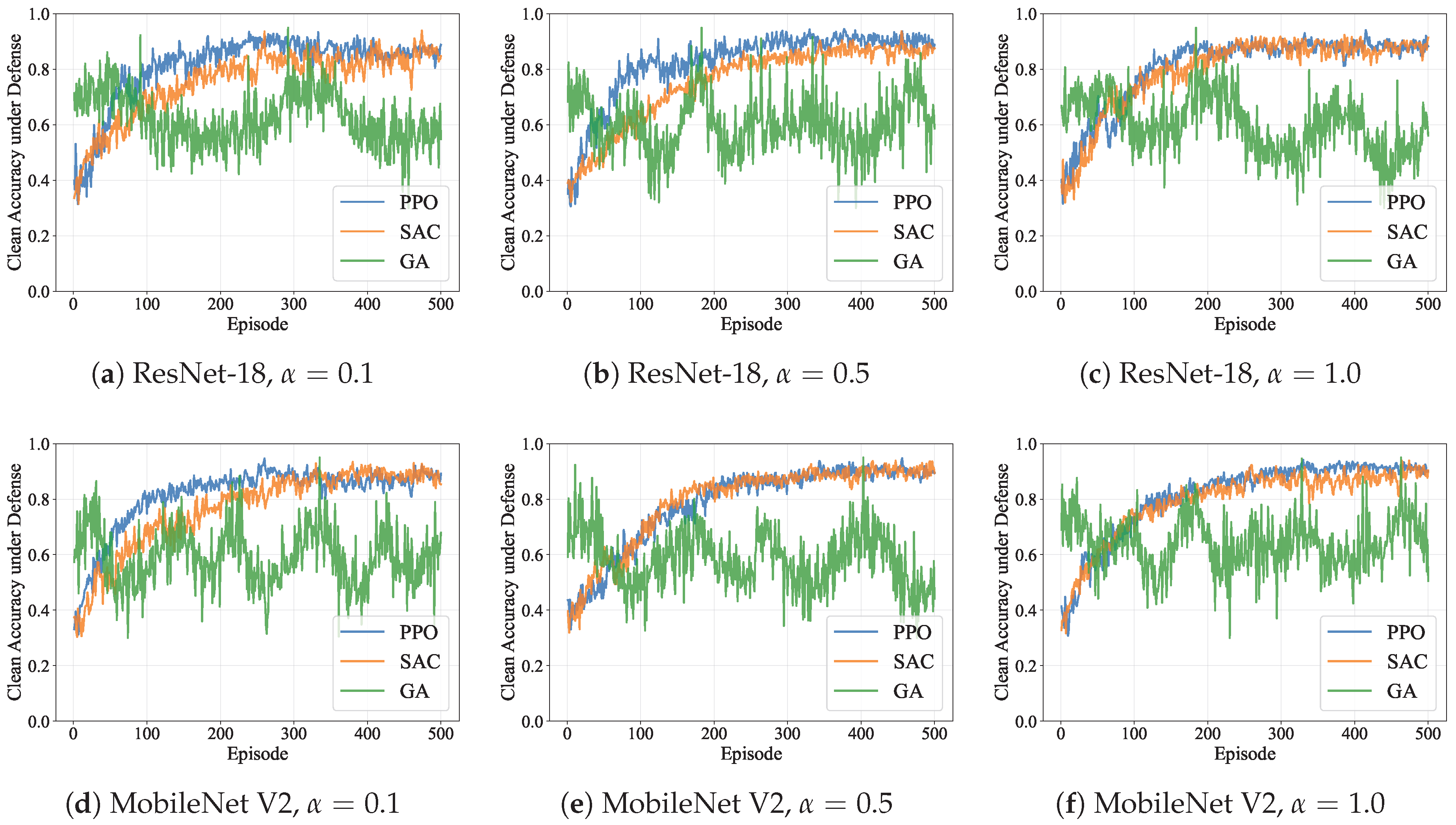

5.2. Clean Accuracy Preservation Performance

5.3. Defense Effectiveness Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Appendix A. Byzantine Robustness Analysis

Appendix A.1. Fundamental Byzantine Robustness Theorem

- 1.

- The Byzantine client fraction satisfies ;

- 2.

- The geometric median approximation error is bounded: , where represents the mean of honest client updates;

- 3.

- The outlier detection mechanism achieves controlled error rates: false positive rate and false negative rate .

Appendix A.2. Corollaries and Extensions

Appendix A.3. Robustness Under Stronger Attack Models

Appendix B. Weiszfeld Algorithm Convergence Analysis

Appendix B.1. Preliminaries and Algorithm Description

Appendix B.2. Main Convergence Theorem

- 1.

- Linear Convergence: The algorithm converges linearly to with rate where

- 2.

- Iteration Complexity: The number of iterations required to achieve ϵ-accuracy iswhere κ is the condition number of the problem;

- 3.

- Acceleration Benefit: The momentum acceleration reduces the convergence constant by a factor of where μ and L are the strong convexity and Lipschitz parameters.

Appendix B.3. Practical Implementation Considerations

Appendix B.4. Robustness Under Approximate Computation

Appendix B.5. Integration with DEFEND Framework

References

- Wen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhang, W. A Survey on Federated Learning: Challenges and Applications. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2023, 14, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadi, A.; Doyle, B.; Gini, F.; Guinamard, K.; Murakonda, S.K.; Liddell, J.; Mellor, P.; Murdoch, S.J.; Naseri, M.; Page, H.; et al. Starlit: Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning to Enhance Financial Fraud Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.10765 (arXiv) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, J.; Yu, S. "X of Information" Continuum: A Survey on AI-Driven Multi-Dimensional Metrics for Next-Generation Networked Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.19657 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Kong, W. Backdoor Attacks and Defenses in Federated Learning: State-of-the-Art, Taxonomy, and Future Directions. IEEE Wireless Communications 2023, 30, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, J.; Duan, Q.; Dong, L.; Cai, Z. Enhancing Vehicular Platooning With Wireless Federated Learning: A Resource-Aware Control Framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.00856 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C.; Man, D.; Yang, W. Beyond Traditional Threats: A Persistent Backdoor Attack on Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI). AAAI, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 21359–21367. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Tao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; Fang, Y. R-ACP: Real-Time Adaptive Collaborative Perception Leveraging Robust Task-Oriented Communications. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ozdayi, M.S.; Kantarcioglu, M.; Gel, Y.R. Defending Against Backdoors in Federated Learning With Robust Learning Rate. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI). AAAI, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 9268–9276. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; Fang, Y. Prioritized Information Bottleneck Theoretic Framework With Distributed Online Learning for Edge Video Analytics. IEEE Transactions on Networking 2025, pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Cai, Z.; Wu, W.; Yin, X. AoI-Aware Resource Management for Smart Health via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, S.; Fan, M.; Liu, X.; Deng, R.H. Privacy-Enhancing and Robust Backdoor Defense for Federated Learning on Heterogeneous Data. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024, 19, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewak, M.; Sahay, S.K.; Rathore, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning in the Advanced Cybersecurity Threat Detection and Protection. Information Systems Frontiers 2023, 25, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, K.I.K.; Li, P.; Sakurai, K.; Dou, D. Trustworthy Federated Learning: Privacy, Security, and Beyond. Knowledge and Information Systems 2025, 67, 2321–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljunaid, S.K.; Almheiri, S.J.; Dawood, H.; Khan, M.A. Secure and Transparent Banking: Explainable AI-Driven Federated Learning Model for Financial Fraud Detection. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2025, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaji, E.; Razavi-Far, R.; Saif, M.; Wang, B.; Yang, Q. Decentralized Federated Learning: A Survey on Security and Privacy. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2024, 10, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingulkar, S.; Pawade, D. Federated Learning Architectures for Credit Risk Assessment: A Comparative Analysis of Vertical, Horizontal, and Transfer Learning Approaches. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Distributed Systems Security (ICBDS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Damoun, F.; Seba, H.; State, R. Privacy-Preserving Behavioral Anomaly Detection in Dynamic Graphs for Card Transactions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Information Systems Engineering (WISE). Springer, 2024, pp. 286–301. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wu, W. Model-Free Cooperative Optimal Output Regulation for Linear Discrete-Time Multi-Agent Systems Using Reinforcement Learning. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2023, 2023, 6350647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Huang, J.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, S. A Dual-Level Game-Theoretic Approach for Collaborative Learning in UAV-Assisted Heterogeneous Vehicle Networks. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Performance, Computing, and Communications Conference (IPCCC). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–8.

- Xiong, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wahaballa, A.; Yeh, K.H. Heterogeneous Privacy-Preserving Blockchain-Enabled Federated Learning for Social Fintech. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2025, pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Ding, Z.; Ostigaard, L.; Huang, J. Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy-Aware Coverage Path Planning for Precision Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Research on Adaptive and Convergent Systems (RACS). ACM, 2025, pp. 1–8.

- Orabi, M.M.; Emam, O.; Fahmy, H. Adapting Security and Decentralized Knowledge Enhancement in Federated Learning Using Blockchain Technology: Literature Review. Journal of Big Data 2025, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.P.; Xiang, Y.; Hasan, M.; Bai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L. A Systematic Literature Review of Robust Federated Learning: Issues, Solutions, and Future Research Directions. ACM Computing Surveys 2025, 57, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Lv, H.; Wang, H.; Feng, G.; Li, X. Practical Cyber Attack Detection With Continuous Temporal Graph in Dynamic Network System. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024, 19, 4851–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh Darban, Z.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Aggarwal, C.; Salehi, M. Deep Learning for Time Series Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 57, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Y.; Hussein, A.R. Dynamic Policy Decision/Enforcement Security Zoning Through Stochastic Games and Meta Learning. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2025, 22, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shi, Z.; Ye, M.; Li, H.; Du, B. Self-Driven Entropy Aggregation for Byzantine-Robust Heterogeneous Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Forty-First International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR, 2024.

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, H. A Multi-Layer Aggregation Backdoor Defense Framework for Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Communication, Remote Sensing and Information Technology (CRSIT). IEEE, 2025, pp. 126–132. [CrossRef]

- Abazari, A.; Ghafouri, M.; Jafarigiv, D.; Atallah, R.; Assi, C. Developing a Security Metric for Assessing the Power Grid’s Posture Against Attacks From EV Charging Ecosystem. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2025, 16, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presekal, A.; Ştefanov, A.; Semertzis, I.; Palensky, P. Spatio-Temporal Advanced Persistent Threat Detection and Correlation for Cyber-Physical Power Systems Using Enhanced GC-LSTM. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2025, 16, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, M.; Dong, A.; Yang, Y. An Active Learning Framework Using Deep Q-Network for Zero-Day Attack Detection. Computers & Security 2024, 139, 103713. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Wu, B.N.; Sun, Y.L.; Xu, Y.P. A Fault-Tolerant and Energy-Efficient Design of a Network Switch Based on a Quantum-Based Nano-Communication Technique. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems 2023, 37, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, A.A.; Ahmed, S.R.; Abdul-Hussein, M.K.; Ahmed, M.R.; Majeed, D.A.; Algburi, S. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Cyber Defense in Network Security. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Cognitive Models and Artificial Intelligence Conference (CMAI). ACM, 2024, pp. 292–297. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, J.; Duan, Q. FedTD3: An Accelerated Learning Approach for UAV Trajectory Planning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wireless Artificial Intelligent Computing Systems and Applications (WASA). Springer, 2025, pp. 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Huang, J.; Duan, Q. Real-Time Intelligent Healthcare Enabled by Federated Digital Twins With AoI Optimization. IEEE Network 2025, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Paparrizos, J.; Boniol, P.; Liu, Q.; Palpanas, T. Advances in Time-Series Anomaly Detection: Algorithms, Benchmarks, and Evaluation Measures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD). ACM, 2025, pp. 6151–6161. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Han, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, S.; Xia, H. Security Defense Strategy Algorithm for Internet of Things Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. High-Confidence Computing 2024, 4, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Han, Z.; Poor, H.V.; Hanzo, L. Age of information in energy harvesting aided massive multiple access networks. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2022, 40, 1441–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhaoui, Y.; Allaoui, A.E.; Amounas, F.; Mohammed, F.; Ziani, S.; Taherdoost, H.; Triantafyllou, S.A.; Bhushan, B. A Multi-Layered Protection System for Enhancing Data Security in Cloud Computing Environments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Environment (AISE). Springer, 2024, pp. 559–568. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ren, Z.; Li, C.; Li, W. A Benders-Combined Safe Reinforcement Learning Framework for Risk-Averse Dispatch Considering Frequency Security Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2025, 72, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, S.; Guo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Fang, Y. Task-Oriented Communications for Visual Navigation With Edge-Aerial Collaboration in Low Altitude Economy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.18317 (arXiv) 2025. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wu, B.; Duan, Q.; Dong, L.; Yu, S. A Fast UAV Trajectory Planning Framework in RIS-Assisted Communication Systems With Accelerated Learning via Multithreading and Federating. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2025, pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Wu, B.N.; Sun, Y.L.; Xu, Y.P. A fault-tolerant and energy-efficient design of a network switch based on a quantum-based nano-communication technique. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems 2023, 37, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset and Client Configuration | ||

| Datasets | – | CIFAR-10, FEMNIST, MNIST |

| Number of clients | N | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 |

| Data distribution | – | Non-IID |

| Dirichlet concentration | 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 | |

| Malicious client ratio | 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 | |

| Model architecture | – | MobileNet V2, ResNet-18 |

| Federated Learning Parameters | ||

| Learning rate | 0.01 | |

| Local epochs | – | 5 |

| Communication rounds | T | 100 |

| Batch size | – | 32 |

| Poisoning ratio | 0.1 | |

| Defense Framework Parameters | ||

| Short window size | 5 | |

| Long window size | 10 | |

| Detection threshold | 0.8 | |

| Temporal regularization | 0.1 | |

| Pattern templates | 10 | |

| Geometric median tolerance | ||

| Reputation decay scales | 3 | |

| MDP and Reinforcement Learning Parameters | ||

| Discount factor | 0.95 | |

| Policy learning rate | – | 0.001 |

| Training episodes | – | 500 |

| Max steps per episode | – | 1000 |

| Exploration rate | 0.1 | |

| Experience buffer size | – | 10,000 |

| Target network update | – | 1000 steps |

| Minimum participation | ||

| N | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.847 ± 0.023 | 0.892 ± 0.019 | 0.924 ± 0.015 |

| 20 | 0.863 ± 0.021 | 0.906 ± 0.017 | 0.938 ± 0.013 |

| 30 | 0.871 ± 0.019 | 0.915 ± 0.016 | 0.947 ± 0.012 |

| 40 | 0.876 ± 0.018 | 0.921 ± 0.015 | 0.952 ± 0.011 |

| 50 | 0.879 ± 0.017 | 0.925 ± 0.014 | 0.956 ± 0.010 |

| N | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.673 ± 0.041 | 0.721 ± 0.038 | 0.768 ± 0.033 |

| 20 | 0.695 ± 0.039 | 0.742 ± 0.035 | 0.789 ± 0.031 |

| 30 | 0.708 ± 0.037 | 0.755 ± 0.033 | 0.802 ± 0.029 |

| 40 | 0.716 ± 0.036 | 0.763 ± 0.032 | 0.811 ± 0.028 |

| 50 | 0.721 ± 0.035 | 0.769 ± 0.031 | 0.817 ± 0.027 |

| N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.943 ± 0.012 | 0.892 ± 0.019 | 0.834 ± 0.026 | 0.768 ± 0.032 |

| 20 | 0.957 ± 0.011 | 0.906 ± 0.017 | 0.847 ± 0.024 | 0.781 ± 0.030 |

| 30 | 0.964 ± 0.010 | 0.915 ± 0.016 | 0.856 ± 0.023 | 0.791 ± 0.029 |

| 40 | 0.969 ± 0.009 | 0.921 ± 0.015 | 0.863 ± 0.022 | 0.798 ± 0.028 |

| 50 | 0.972 ± 0.009 | 0.925 ± 0.014 | 0.867 ± 0.021 | 0.803 ± 0.027 |

| N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.825 ± 0.028 | 0.721 ± 0.038 | 0.612 ± 0.045 | 0.498 ± 0.052 |

| 20 | 0.841 ± 0.026 | 0.742 ± 0.035 | 0.634 ± 0.042 | 0.521 ± 0.049 |

| 30 | 0.852 ± 0.025 | 0.755 ± 0.033 | 0.649 ± 0.040 | 0.537 ± 0.047 |

| 40 | 0.859 ± 0.024 | 0.763 ± 0.032 | 0.658 ± 0.039 | 0.547 ± 0.046 |

| 50 | 0.864 ± 0.023 | 0.769 ± 0.031 | 0.664 ± 0.038 | 0.554 ± 0.045 |

| N | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.821 ± 0.025 | 0.869 ± 0.021 | 0.908 ± 0.017 |

| 20 | 0.836 ± 0.023 | 0.883 ± 0.019 | 0.921 ± 0.015 |

| 30 | 0.845 ± 0.022 | 0.892 ± 0.018 | 0.930 ± 0.014 |

| 40 | 0.851 ± 0.021 | 0.898 ± 0.017 | 0.936 ± 0.013 |

| 50 | 0.855 ± 0.020 | 0.902 ± 0.016 | 0.940 ± 0.012 |

| N | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.657 ± 0.043 | 0.703 ± 0.040 | 0.751 ± 0.036 |

| 20 | 0.678 ± 0.041 | 0.724 ± 0.038 | 0.772 ± 0.034 |

| 30 | 0.691 ± 0.039 | 0.737 ± 0.036 | 0.785 ± 0.032 |

| 40 | 0.699 ± 0.038 | 0.745 ± 0.035 | 0.793 ± 0.031 |

| 50 | 0.704 ± 0.037 | 0.751 ± 0.034 | 0.799 ± 0.030 |

| N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.926 ± 0.014 | 0.869 ± 0.021 | 0.807 ± 0.028 | 0.739 ± 0.035 |

| 20 | 0.940 ± 0.013 | 0.883 ± 0.019 | 0.821 ± 0.026 | 0.753 ± 0.033 |

| 30 | 0.947 ± 0.012 | 0.892 ± 0.018 | 0.831 ± 0.025 | 0.763 ± 0.032 |

| 40 | 0.952 ± 0.011 | 0.898 ± 0.017 | 0.838 ± 0.024 | 0.770 ± 0.031 |

| 50 | 0.955 ± 0.010 | 0.902 ± 0.016 | 0.843 ± 0.023 | 0.775 ± 0.030 |

| N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.809 ± 0.030 | 0.703 ± 0.040 | 0.591 ± 0.047 | 0.474 ± 0.054 |

| 20 | 0.825 ± 0.028 | 0.724 ± 0.038 | 0.613 ± 0.045 | 0.497 ± 0.052 |

| 30 | 0.836 ± 0.027 | 0.737 ± 0.036 | 0.628 ± 0.043 | 0.514 ± 0.050 |

| 40 | 0.843 ± 0.026 | 0.745 ± 0.035 | 0.637 ± 0.042 | 0.525 ± 0.049 |

| 50 | 0.848 ± 0.025 | 0.751 ± 0.034 | 0.644 ± 0.041 | 0.533 ± 0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).