1. Introduction

The control of thin-film morphology is a central requirement in the manufacturing of advanced thin-film-based devices, where surface roughness, grain orientation and interfacial uniformity directly impact device yield, reproducibility and long-term reliability. In micro- and nanoscale systems—including MEMS, sensors, optoelectronic components and energy devices—the fabrication window is often constrained not by material composition but by the ability to reproducibly control film growth at the nanometer scale [

1,

2].

Classical thin-film growth theories provide a robust framework for describing film evolution under intrinsic growth conditions. Burton–Cabrera–Frank (BCF) step-flow theory successfully explains the motion of atomic steps and terrace evolution on crystalline surfaces during epitaxial growth [

3]. Classical nucleation theory quantitatively relates supersaturation and surface energy to nucleation density and island formation [

4]. At larger length scales, Mullins-type surface diffusion models capture curvature-driven interface relaxation and provide the basis for understanding surface smoothening through mass transport [

5,

6]. These approaches have been widely validated and remain central to thin-film science.

However, a defining characteristic of all these classical frameworks is that the energetic landscape governing growth is assumed to be field-free. External perturbations—when considered at all—are typically introduced indirectly, for example through effective changes in temperature, mobility or deposition rate. As a result, these models do not provide explicit mechanisms by which external electric fields couple to surface energetics or kinetics.

This limitation becomes evident in modern manufacturing environments. In sputtering and PLD, substrate bias and plasma-induced electric fields are routinely present; in CVD and ALD, electrostatic charging and externally applied fields have been reported to influence nucleation density and film uniformity [

1,

2]. Numerous experimental studies show that applying external fields can reduce surface roughness, enhance densification and promote preferred crystallographic orientation without modifying chemical precursors or deposition temperature [

7,

8,

9]. Yet these effects cannot be rationalized within BCF, nucleation theory or Mullins-type models, because none of these frameworks contains a term that couples the field directly to surface species.

Existing attempts to address field effects typically rely on phenomenological interpretations. For instance, enhanced smoothening is often attributed to an “effective increase in surface mobility”, while changes in nucleation density are explained post hoc through modified supersaturation or plasma chemistry. While such interpretations may be qualitatively useful, they lack predictive power and fail to explain why similar field-induced effects are observed across fundamentally different deposition techniques.

This gap is particularly evident in continuum growth models. The Edwards–Wilkinson and Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equations describe interface roughening and scaling behavior under stochastic growth conditions [

6,

10], while the Wolf–Villain model incorporates slope-dependent diffusion to account for mound formation [

11]. However, in all these models anisotropy and instability arise from intrinsic surface properties or nonlinearities, not from externally controllable fields. Consequently, they cannot predict a field-controlled suppression of long-wavelength roughening modes or define stability conditions linked to measurable field parameters.

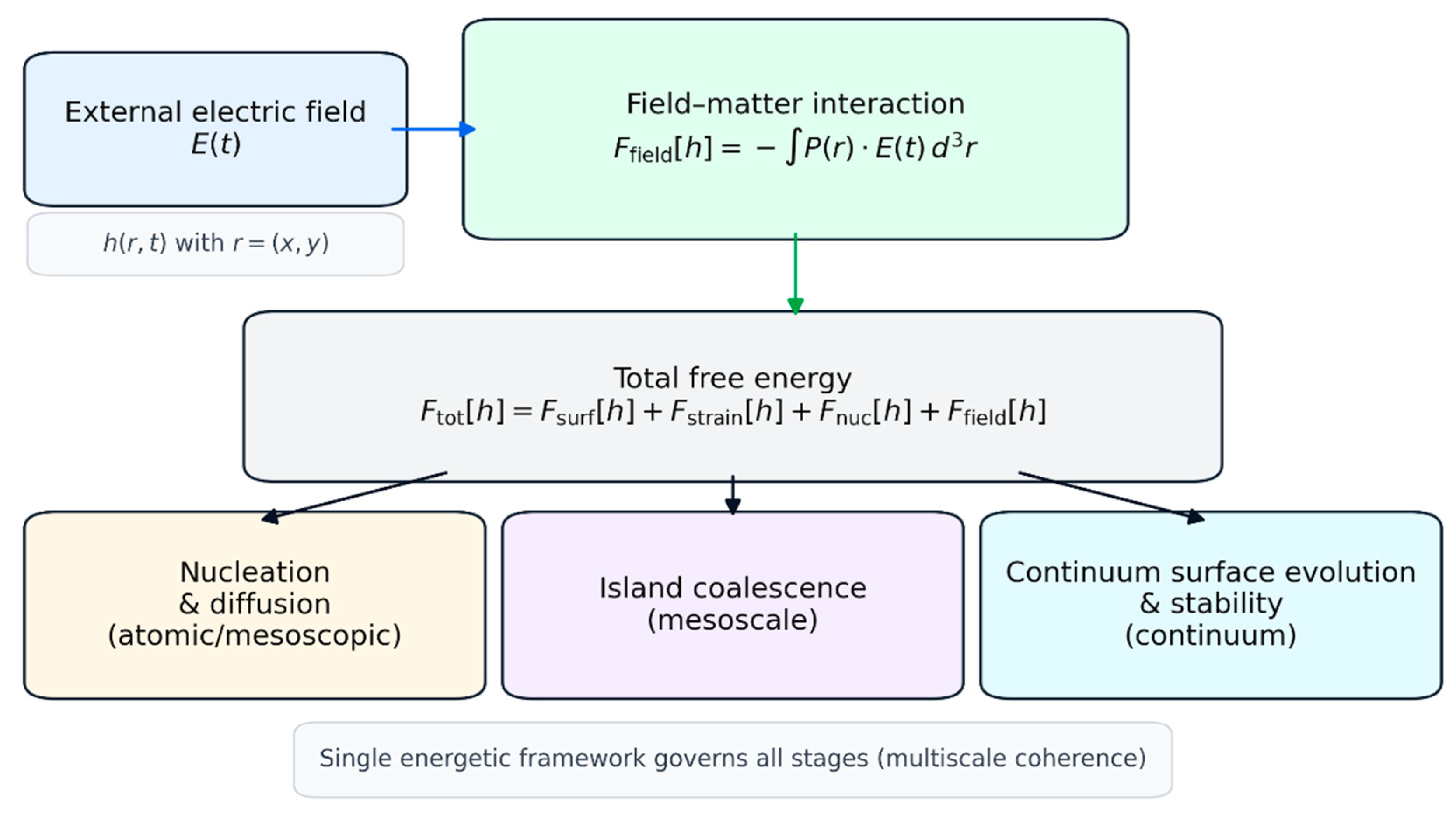

In this work, we address this unresolved problem by introducing the Field-Driven Growth Model (FDGM). The key novelty of the FDGM is the explicit incorporation of field–matter interactions into the free-energy functional governing thin-film growth. Rather than treating external fields as secondary process parameters, the FDGM shows that effective dipolar coupling between surface species and externally applied electric fields directly reshapes the energetic landscape underlying nucleation, diffusion and coalescence.

As a result, the FDGM provides several capabilities absent from existing approaches. First, it introduces a physically grounded mechanism for field-assisted nucleation through a direct reduction of the nucleation barrier, rather than through indirect changes in supersaturation. Second, it predicts anisotropic surface diffusion arising from directional lowering of diffusion barriers, linking microscopic field effects to mesoscopic growth anisotropy. Third, at the continuum scale, the FDGM yields an explicit field-induced stabilization term in the surface evolution equation, leading to a field-controlled cutoff wavelength beyond which roughening modes are suppressed. None of these features can be derived within classical growth models or phenomenological extensions thereof.

By unifying these mechanisms within a single energetic framework, the FDGM fills a critical gap between empirical observations of field-assisted growth and predictive thin-film manufacturing theory. The model explains why field-induced ordering is observed across disparate deposition techniques and provides analytical criteria that directly link external field parameters to morphological outcomes. In doing so, the FDGM establishes a foundation for rational design of field-assisted deposition strategies to target improved surface uniformity in advanced thin-film-based devices. The central concepts and multiscale structure of the FDGM are summarized schematically in

Figure 1.

2. Field-Driven Energetic Framework

Thin-film growth is governed by the evolution of the system toward configurations that minimize an appropriate free-energy functional under non-equilibrium conditions. In classical growth theories, this functional typically includes contributions from surface and interface energies, elastic strain and, implicitly, chemical driving forces associated with deposition flux and supersaturation [

3,

4,

5]. In this section, we generalize this framework by explicitly incorporating the interaction between externally applied electric fields and surface species into the total free energy.

We consider a growing thin film described by a height field

, where

denotes the in-plane coordinates. The total free energy is written as

Here,

accounts for surface and interface energies,

captures elastic contributions arising from lattice mismatch or intrinsic stress, and

represents the energetic cost associated with the formation of stable nuclei and islands, as described within classical nucleation theory [

4]. These terms constitute the standard energetic description underlying BCF step-flow models, continuum surface diffusion theories and related approaches [

3,

5,

6].

The defining extension introduced in the Field-Driven Growth Model (FDGM) is the explicit inclusion of a field–matter interaction term,

where

denotes an externally applied electric field and

is the local polarization density associated with surface adatoms, small clusters, or islands. Such dipolar coupling terms are well established in condensed-matter descriptions of field–matter interactions and provide a physically transparent route to incorporate external fields into the energetic landscape [

12,

13]; they have also been widely invoked in the context of field-assisted thin-film growth [

1,

2].

For polarizable surface species, the polarization can be expressed to leading order as

where

is an effective polarizability that depends on the chemical nature of the adsorbate and its local environment, as described in classical linear-response theory [

12,

13]. In the linear-response regime, Equation (2) recovers the familiar induced-dipole energy scaling

. In this formulation, the polarization is assumed to be predominantly induced rather than permanent, which is appropriate for the moderate field strengths relevant to thin-film manufacturing, where higher-order nonlinear polarization effects can be neglected.

Accordingly, the associated field–matter interaction energy for induced polarization is fundamentally quadratic in the electric field amplitude, . Any effective linear dependence on the field appearing in subsequent sections should therefore be understood as arising from energy differences between metastable and transition (saddle-point) configurations along activated pathways, reflecting geometric asymmetry and induced charge redistribution, rather than from a fundamental linear dipole–field coupling

The temporal evolution of the film surface is assumed to follow gradient dynamics driven by the functional derivative of the total free energy,

where

is an effective mobility and

represents stochastic fluctuations arising from deposition noise and thermal effects. This form is consistent with continuum descriptions of surface evolution under surface-diffusion-limited kinetics [

5,

6], and provides the baseline relaxation dynamics upon which growth-specific terms are later discussed.

The presence of in Equation (4) constitutes the central conceptual advance of the FDGM. Unlike classical growth models, where external perturbations enter only indirectly through modified kinetic coefficients, the FDGM introduces the external field directly into the energetic driving force. As a consequence, nucleation barriers, diffusion pathways, island interactions and large-scale morphological stability are all modified in a consistent and physically grounded manner.

It is important to emphasize that Equation (2) does not assume a specific deposition technique or field configuration. The framework applies equally to static or time-dependent electric fields and is therefore relevant to a wide range of manufacturing environments, including substrate-biased sputtering, plasma-assisted PLD and field-influenced CVD or ALD processes [

1,

2,

8]. The subsequent sections demonstrate how this single additional energetic term propagates across length scales, yielding field-assisted nucleation (

Section 3), anisotropic surface diffusion (

Section 4), directed island coalescence (

Section 5) and field-induced stabilization of surface modes (

Section 6).

Orders of Magnitude and Regime of Applicability

Although the Field-Driven Growth Model (FDGM) is formulated in a general manner, it is important to establish representative orders of magnitude for the relevant parameters in order to clarify the physical regime in which the predicted effects become relevant for realistic thin-film deposition processes.

For electric fields applied during field-assisted growth, typical values range from

–

, as commonly encountered in substrate biasing, plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition, and field-assisted chemical vapor deposition environments [

8,

14,

15,

16]. The effective polarizability of surface adatoms or small clusters is typically of the order

–

, depending on the chemical nature of the species and its local bonding environment [

12,

13]. Within these ranges, the induced-dipole contribution

is generally small compared with bond energies, but it can be comparable to the free-energy differences between competing activated pathways and therefore measurably bias nucleation statistics and early-stage morphology.

While this energy scale is small compared to typical atomic bond energies, it is comparable to

at moderate growth temperatures (300–600 K) and, more importantly, to the energetic differences between competing activated pathways in nucleation and surface diffusion. Recent experimental and modelling studies have shown that electric fields of this magnitude can measurably alter surface reaction energetics, nucleation density and film morphology without modifying chemical precursors or growth temperature [

14,

15,

17]. Consequently, even modest field-induced energetic contributions can have a statistically significant impact on rare-event selection and collective surface evolution.

The FDGM explicitly assumes this regime of moderate field strengths, in which linear polarization provides an adequate description of field–matter interactions [

12,

13] and nonlinear effects such as field-induced desorption, surface ionization or strong electronic restructuring can be neglected. Extension of the model to extreme-field regimes would require additional energetic terms beyond the scope of the present framework.

To guide the reader before we move on to the multiscale formulation,

Table 1 summarizes the key FDGM parameters used throughout the paper, their physical meaning, units/scaling in the model, and practical routes for experimental inference.

3. Field-Assisted Nucleation

Nucleation constitutes the first irreversible step in thin-film growth and plays a decisive role in determining island density, spatial uniformity and the subsequent evolution of film morphology. Within classical nucleation theory, the formation of stable clusters results from a competition between the energetic cost of creating new interfaces and the thermodynamic driving force associated with supersaturation or chemical potential difference [

4].

3.1. Classical Nucleation Barrier

For a cluster of characteristic radius

, the classical free-energy change can be written as

where

is an effective surface energy and

denotes the chemical potential difference driving growth. The critical radius

and the corresponding nucleation barrier

follow from the extremum condition

, yielding

The nucleation rate is then given by

where

is a kinetic pre-factor. This framework successfully describes nucleation under field-free conditions and has been extensively validated across a wide range of thin-film systems [

4,

6].

3.2. Modification of the Nucleation Barrier by External Fields

In the presence of an external electric field, surface adatoms and small clusters may acquire an effective dipole moment due to intrinsic polarity or, more commonly, induced polarization. Within the FDGM introduced in

Section 2, this interaction contributes an additional energetic term associated with the coupling between the cluster polarization and the external field.

At the level of the free-energy functional, the fundamental field-dependent contribution for induced dipoles is quadratic in the electric field, of the form .

However, when evaluating the stability of a given cluster configuration relative to the activated nucleation pathway, the difference in field-modified energy between the saddle-point configuration and the metastable state introduces an effective directional bias. This bias reflects the asymmetry of the nucleation pathway and saddle-point geometry under the applied field, rather than a true linear dipole–field coupling.

Accordingly, the field-related contribution to the cluster free energy difference relevant for nucleation can be written, to leading order, as

where

denotes an effective dipolar projection parameter that encapsulates the quadratic polarization response, the geometry of the critical nucleus and induced charge redistribution along the applied field direction, and

is the external electric field.

The total free energy associated with cluster formation thus becomes

To leading order, the presence of the field does not significantly alter the critical radius

in regimes relevant to thin-film manufacturing, but it does modify the height of the nucleation barrier. Evaluated at

, the effective barrier reads

where

is a geometric factor that accounts for cluster shape, partial wetting and orientation effects [

1,

4].

This formulation should be understood as an effective barrier-bias representation of field-induced asymmetry between competing nucleation pathways, rather than as a fundamental linear field–matter interaction for an induced dipole in a strictly uniform field. In practice, the activation barrier depends on differences in polarization response and/or effective dipole moment between the metastable configuration and the transition-state configuration; therefore, the field-induced contribution can be recast, to leading order, into a directional term proportional to

(see

Appendix A).

3.3. Field-Assisted Nucleation Rate and Physical Implications

Substituting Equation (10) into Equation (7), the nucleation rate in the presence of a field becomes

This expression highlights several important physical consequences absent from classical nucleation theory:

-

Directional bias in nucleation.

Because the barrier reduction depends on the projection , nucleation becomes orientation-dependent. Clusters aligned with the field are energetically favoured, leading to spatially more uniform and directionally correlated nucleation patterns.

-

Enhanced reproducibility.

By reducing the sensitivity of to stochastic fluctuations in , the field-assisted term narrows the distribution of nucleation events. This effect is particularly relevant for manufacturing contexts where reproducibility and uniformity are critical.

It is important to emphasize that the effective dipole moment

introduced here does not require the presence of permanently polar species. In many technologically relevant systems, polarization arises from an induced response of adatoms or small clusters to the external field and to the electronic environment of the substrate, as described within classical electrodynamics of condensed media [

12,

13].

This mechanism is particularly relevant for semiconductors, oxides and partially ionic surfaces, where field-induced charge redistribution can generate transient dipole moments sufficient to influence energetic barriers. Recent studies on oxide and dielectric thin films have directly demonstrated electric-field-induced modifications of nucleation behavior and phase stability consistent with such mechanisms [

9,

14,

17]. In metallic systems, although individual adatom polarization is strongly screened, collective effects associated with clusters, interfaces or near-surface field gradients may still yield non-negligible contributions at the statistical level relevant for nucleation and early-stage growth [

1,

7].

Accordingly, the FDGM does not rely on a restrictive material-specific assumption but rather captures a generic mechanism applicable whenever an effective polarizable response of surface species is present.

3.4. Relation to Existing Approaches and Unresolved Limitations

Previous attempts to rationalize field-assisted nucleation often invoke indirect mechanisms, such as effective changes in surface mobility, local temperature or plasma chemistry. While such interpretations may capture specific experimental trends, they do not provide an explicit energetic mechanism linking the external field to the nucleation barrier itself.

In contrast, the FDGM introduces this link directly at the level of the free-energy functional. The effective linear bias appearing in Equation (10) should be understood as a leading-order manifestation of an underlying field-dependent energy landscape, ensuring consistency with the induced-polarization framework introduced in

Section 2. Importantly, this mechanism cannot be derived within classical nucleation theory or through phenomenological extensions that treat the field solely as a kinetic modifier.

The consequences of the reduced and direction-dependent nucleation barrier propagate to later growth stages. Increased nucleation density and spatial regularity influence adatom capture, island growth and eventual coalescence, providing a natural bridge to the field-induced diffusion anisotropy discussed in

Section 4.

4. Field-Induced Surface Diffusion

Following nucleation, surface diffusion governs mass transport across the growing interface and plays a central role in determining island growth kinetics, coalescence pathways and the development of surface roughness. In classical growth theory, surface diffusion is treated as a thermally activated process driven by gradients in chemical potential, with isotropic diffusion barriers that depend solely on the local atomic environment [

5,

6].

4.1. Classical Description of Surface Diffusion

Under field-free conditions, the surface diffusion coefficient is commonly expressed as

where

is a prefactor related to the attempt frequency and jump distance,

is the activation energy for adatom hopping,

is the Boltzmann constant and

is the substrate temperature. This formulation underlies both atomistic models and continuum descriptions of surface-diffusion-limited growth, including Mullins-type relaxation theories [

5,

6].

Within this framework, diffusion is intrinsically isotropic on sufficiently symmetric surfaces, and any anisotropy arises from crystallographic effects, step-edge barriers or surface reconstruction. External fields do not explicitly appear in the energetic description and therefore cannot directly bias diffusion pathways.

4.2. Modification of the Diffusion Barrier by External Fields

In the FDGM, surface diffusion is affected by the same field–matter interaction introduced in

Section 2. Adatoms migrating across the surface experience a local energetic contribution arising from their interaction with an external electric field through induced polarization effects.

At the level of the free-energy functional, the field-dependent contribution to the adatom energy is quadratic in the electric field. However, during a thermally activated diffusion event, the relevant quantity is the energy difference between the initial adsorption site and the transition (saddle-point) configuration. The asymmetry of these configurations with respect to the field direction gives rise to an effective directional bias. This bias reflects differences in induced polarization and charge redistribution between metastable and saddle-point configurations, rather than a fundamental linear dipole–field interaction.

For a diffusion hop characterized by a direction

relative to the applied field, the effective activation energy can therefore be written as

where

is a coupling coefficient that depends on the polarizability of the diffusing species and the local surface environment. This expression represents a linearised form of the field-induced energetic asymmetry between initial and transition states, valid in the regime of moderate fields and small activation-energy differences, and should not be interpreted as implying a true linear dependence of the total polarization energy on the field amplitude. Diffusion hops aligned with the field direction experience a reduced effective barrier, while hops opposing the field are energetically disfavoured.

The resulting diffusion coefficient becomes explicitly anisotropic,

Such anisotropic diffusion and enhanced directional mass transport have been reported experimentally in energetically assisted and field-assisted growth environments, where preferential mass transport along selected directions leads to smoother surfaces and more uniform island growth [

1,

2,

18].

4.3. Physical Implications of Anisotropic Diffusion

The directional dependence introduced in Equation (14) has several important consequences:

-

Enhanced mass transport along field-favoured directions.

Adatoms preferentially migrate along directions that minimise the effective diffusion barrier, leading to accelerated filling of low-lying regions and suppression of height fluctuations.

-

Coupling between nucleation density and diffusion length.

The increased nucleation density predicted in

Section 3 reduces the average diffusion length, while anisotropic diffusion redistributes mass more efficiently between neighbouring islands. Together, these effects promote homogeneous growth and reduce the likelihood of isolated, fast-growing features.

-

Suppression of kinetic roughening.

By biasing diffusion toward configurations that reduce the total free energy, within an otherwise conserved surface-diffusion framework, field-induced anisotropy counteracts the stochastic amplification of surface roughness typically observed under non-equilibrium deposition conditions.

4.4. Relation to Existing Diffusion Models

Slope-dependent diffusion models, such as the Wolf–Villain model, incorporate anisotropy through intrinsic surface geometry and local slope effects [

11]. While these approaches successfully describe mound formation and kinetic roughening in certain regimes, the anisotropy they predict is not externally tunable and arises solely from surface morphology.

In contrast, the FDGM introduces externally controllable anisotropy through the applied field. The diffusion bias in Equation (14) does not depend on surface slope or crystallography alone, but can be modulated dynamically by adjusting field strength or orientation. This distinction is crucial for manufacturing applications, where external control parameters are preferred over intrinsic material constraints.

Moreover, the anisotropic diffusion derived here emerges from the same field-modified free-energy functional that governs nucleation and, as shown in the following section, island coalescence. This ensures energetic consistency across growth stages, which is absent in phenomenological extensions of classical diffusion models.

4.5. Transition to Mesoscale Coalescence

As islands grow and their diffusion fields overlap, the anisotropic transport of adatoms leads naturally to biased coalescence pathways. Regions that minimise the combined surface, strain and field energy are preferentially filled, driving islands toward energetically favourable configurations. In this sense, directed coalescence emerges as a collective consequence of biased mass transport rather than as a separate force-driven mechanism, providing the physical basis for the processes discussed in

Section 5.

5. Directed Coalescence of Islands

As thin-film growth progresses beyond the initial nucleation and diffusion stages, individual islands expand, interact and eventually coalesce to form a continuous film. The manner in which islands coalesce strongly influences grain size distribution, texture development and defect formation. In classical growth models, coalescence is largely governed by geometric proximity and isotropic mass transport, with limited control over the pathways by which islands merge [

2,

18].

5.1. Classical View of Island Coalescence

Under field-free conditions, island coalescence is typically described as a consequence of surface diffusion and capture-zone overlap. As islands grow, their diffusion fields intersect, leading to material transfer that fills the gaps between neighbouring features. This process is often treated as isotropic and driven by local curvature and chemical potential gradients, without invoking long-range interactions or directional forces [

5,

6].

While such descriptions successfully account for basic coalescence kinetics, they provide little insight into experimentally observed texture selection, grain alignment or enhanced densification under field-assisted growth conditions. In particular, classical models cannot explain why islands appear to merge preferentially along specific directions or why certain grain orientations are stabilised during coalescence.

5.2. Field-Induced Energetic Bias on Islands

Within the FDGM, islands are treated as mesoscale entities characterised by an effective polarisation

, arising from the collective response of their constituent atoms to the external field. The interaction energy between an island and the field can be written as

where

denotes the position of the island’s centre of mass.

In a strictly uniform external field, this term does not generate a net translational force on an isolated island. However, it modifies the energetic cost of island configurations, shapes and orientations, and therefore biases the energetically favorable pathways through which islands exchange mass and evolve during coalescence.

Spatial variations in island polarization, local surface morphology or near-surface field gradients—such as those naturally present close to island edges, steps or plasma sheaths—can further enhance this energetic bias without requiring a macroscopic field gradient.

Accordingly, the role of the field at the mesoscale is not to exert a classical mechanical force on islands, but to reshape the effective energy landscape that governs their interaction and mass-transfer pathways.

This energetic bias derives from the same field–matter coupling introduced at the atomistic scale, ensuring consistency between microscopic diffusion anisotropy and mesoscale island dynamics.

5.3. Directed Coalescence and Texture Selection

The presence of a field-induced energetic bias modifies the landscape governing island interactions. Coalescence no longer occurs solely along the shortest geometric path, but preferentially follows trajectories that minimise the combined surface, strain and field energy. As a result:

-

Directional merging of islands.

Islands tend to coalesce along field-favoured directions, leading to anisotropic grain shapes and aligned grain boundaries.

-

Enhanced densification.

Field-biased mass transport promotes the elimination of voids and narrow gaps that would otherwise persist during isotropic coalescence.

-

Texture stabilisation.

Grain orientations that couple favourably to the external field are selectively stabilised during coalescence, providing a mechanism for field-induced texture control observed in sputtering and PLD processes [

8,

18].

These effects provide a natural explanation for experimental observations of improved film density and orientation under applied fields, even in the absence of a net force acting on individual islands, and cannot be readily explained by diffusion anisotropy alone.

5.4. Relation to Existing Mesoscale Models

Mesoscale coalescence models typically treat islands as passive geometric entities whose interactions are mediated solely by surface diffusion and elastic strain [

2,

18]. While such approaches can capture coarsening dynamics, they do not include external control parameters capable of biasing coalescence pathways.

In contrast, the FDGM introduces an externally controllable energetic contribution that directly influences island interactions. This distinction is particularly important for manufacturing applications, where control over texture and defect density is often more critical than equilibrium grain size.

5.5. Transition to Continuum-Scale Morphology

Directed coalescence represents the final mesoscale manifestation of the field-modified energy landscape. Once islands have merged into a continuous film, the cumulative effects of field-assisted nucleation, anisotropic diffusion and energetically biased coalescence manifest as large-scale morphological changes. In the following section, we formalise this connection by deriving a continuum surface evolution equation that captures the field-induced stabilisation of interface modes.

6. Continuum Surface Evolution and Stability

Once island coalescence has produced a laterally continuous film, thin-film growth can be described at the continuum level by the evolution of the surface height field . At this stage, the cumulative effects of field-assisted nucleation, anisotropic diffusion and directed coalescence manifest as modifications to the stability and relaxation behaviour of surface modes. In this section, we derive the continuum evolution equation within the FDGM framework and analyse its implications for morphological stability.

6.1. Classical Continuum Description

Under surface-diffusion-limited kinetics, the temporal evolution of the surface height is governed by mass conservation,

where

is the surface mass flux. In the continuum description, curvature-driven surface transport is represented by a surface flux driven by gradients of the chemical potential,

where

is an effective surface mobility. For small surface slopes, the chemical potential is proportional to the local curvature,

where

is the surface energy. Substituting Equations (17) and (18) into Equation (16) yields the classical Mullins equation,

where

(units

) is the Mullins surface-smoothing coefficient. In many surface-diffusion models,

(and hence

) can be related to microscopic quantities such as the surface diffusivity

, the atomic volume

, and the near-surface atomic density; however, for the purposes of the present continuum treatment we retain

and

as effective coefficients. This equation describes curvature-driven relaxation of surface roughness through surface diffusion [

5,

6].

Fourier decomposition of the surface profile,

leads to the classical dispersion relation

indicating that all surface modes decay in time, albeit with very slow relaxation for long-wavelength modes (

).

It is important to note that while Equations (16)–(21) describe purely conservative surface-diffusion-limited relaxation, real thin-film growth typically involves additional non-conservative processes, such as attachment–detachment kinetics, surface incorporation and exchange with the deposition flux. In such regimes, the surface height is not strictly conserved locally, and effective non-conservative relaxation terms may arise in the continuum description, consistent with Edwards–Wilkinson–type dynamics.

6.2. Field-Induced Modification of the Continuum Dynamics

To account for the coexistence of surface-diffusion-driven mass transport and attachment–detachment kinetics during thin-film growth, we adopt a generalized continuum description combining conservative and non-conservative relaxation channels. The surface height evolution is therefore written in the canonical form

where

, the first term represents conservative surface diffusion, while the second term accounts for non-conservative relaxation associated with attachment–detachment and incorporation processes during growth.

Within the FDGM, the surface chemical potential derives from the functional derivative of the total free energy defined in

Section 2. At the continuum stage of growth, once nucleation has ceased and the film is laterally continuous, only those free-energy contributions that depend explicitly on the surface height field contribute to the chemical potential. In this regime, the nucleation term no longer depends on

, while elastic strain contributions are assumed to be either constant or weakly dependent on

and are therefore absorbed into effective material parameters. As a result, the chemical potential reduces to

For small height fluctuations around a nominally flat surface, local variations in modify the spatial distribution and density of polarizable surface species exposed to the external field, and therefore the integrated dipolar interaction energy. Expanding the field-dependent contribution about the flat reference state and retaining terms linear in the surface height yields, to leading order, a restoring contribution proportional to the local height deviation .

In the presence of attachment–detachment kinetics or exchange with the deposition flux, this restoring contribution enters the continuum dynamics as an effective non-conservative relaxation term, reflecting the energetic penalty associated with deviations from configurations that minimise the field–matter interaction energy.

Higher-order contributions become relevant only for large amplitudes or steep surface slopes and are neglected here, as the present stability analysis is restricted to the regime of small perturbations, consistent with classical continuum treatments of surface diffusion and morphological relaxation [

4,

5,

11].

The surface energy contribution recovers the classical curvature term in Equation (18). The field-dependent contribution introduces an additional restoring tendency that penalises deviations of the surface profile from configurations that minimise the field–matter interaction energy. Accordingly, the field-induced contribution acts as an effective non-conservative stabilizing channel in the continuum evolution. This contribution can be expressed as a linear stabilising term,

where

is a positive coefficient that quantifies the strength of the field-induced stabilisation. Physically,

represents the rate at which field-modified energetics penalise local height deviations through attachment–detachment and incorporation processes, rather than through purely diffusive mass transport. For time-dependent or alternating fields,

scales with the time-averaged field intensity and the effective polarizability of the surface species, consistent with experimental and theoretical studies of field- and energy-assisted growth processes [

1,

2].

The resulting continuum evolution equation becomes

where

(units

) is the Mullins surface-smoothing coefficient (prefactor of the curvature-driven

term),

is the field-induced relaxation rate, and

represents stochastic noise associated with deposition and thermal fluctuations. In microscopic surface-diffusion models,

can be related to

,

,

,

, and the near-surface atomic density; here it is treated as an effective coefficient [

5,

6].

6.3. Dispersion Relation and Stability Spectrum

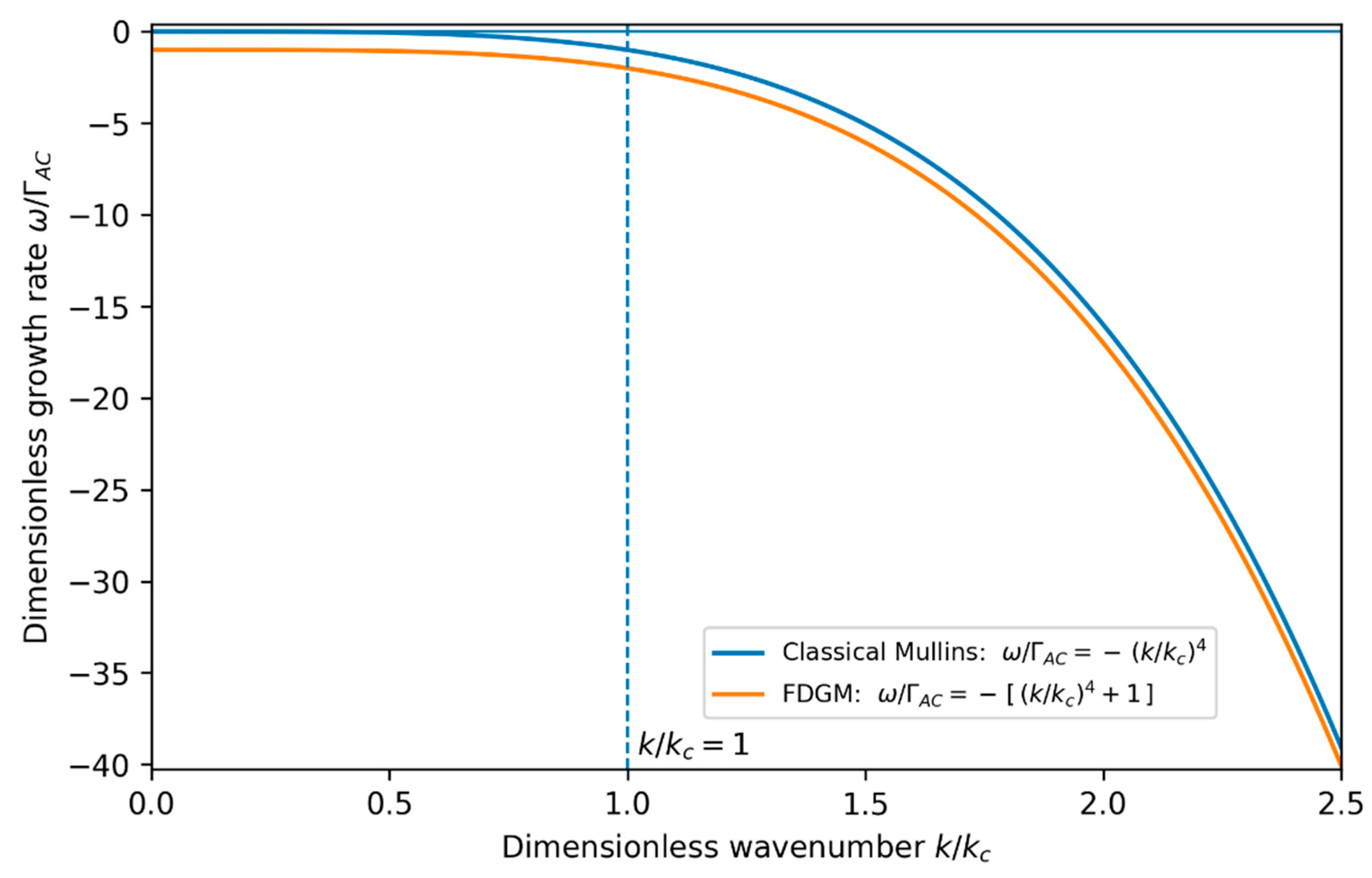

Applying the Fourier decomposition in Equation (21) to Equation (25) yields

The corresponding dispersion relation is therefore

which constitutes a central result of the FDGM in the regime where non-conservative surface kinetics coexist with surface diffusion during growth. Compared to the classical Mullins spectrum in Equation (21), the field-induced term introduces a uniform downward shift of all surface modes.

The resulting dispersion relation is illustrated schematically in

Figure 2, which highlights the uniform downward shift of the stability spectrum induced by the field-dependent term and the enhanced damping of long-wavelength surface modes

The field-induced contribution does not introduce a new instability but instead leads to a constant downward shift of the dispersion spectrum, characteristic of a stabilising non-conservative relaxation channel, so that the FDGM growth rate remains more negative than the classical Mullins prediction for all wave numbers.

6.4. Field-Controlled Stability Cutoff

The relative importance of curvature-driven relaxation and field-induced stabilisation depends on the wavenumber

. Defining a characteristic cutoff wavenumber

through the condition

we obtain

This cutoff therefore represents a crossover between diffusion-dominated relaxation at short wavelengths and field-controlled non-conservative damping at long wavelengths, rather than a sharp instability threshold.

For modes with

, the decay rate is dominated by the field-induced term, and long-wavelength roughening modes are strongly suppressed. In contrast, modes with

relax primarily through classical curvature-driven diffusion. The associated relaxation time is

In the regime

, the decay time becomes approximately independent of wavelength, consistent with the behaviour of strongly damped surface modes in classical continuum descriptions of surface relaxation [

5,

6].

6.5. Implications for Morphological Control

The existence of a field-controlled cutoff wavelength represents a qualitative departure from classical growth theory, in which long-wavelength surface modes are only weakly relaxed by curvature-driven diffusion [

5,

6]. In field-free systems, long-wavelength modes relax extremely slowly and dominate surface roughness at late stages of growth [

5,

6]. Within the FDGM, these modes are actively damped by the external field, providing a direct mechanism for suppressing large-scale roughness.

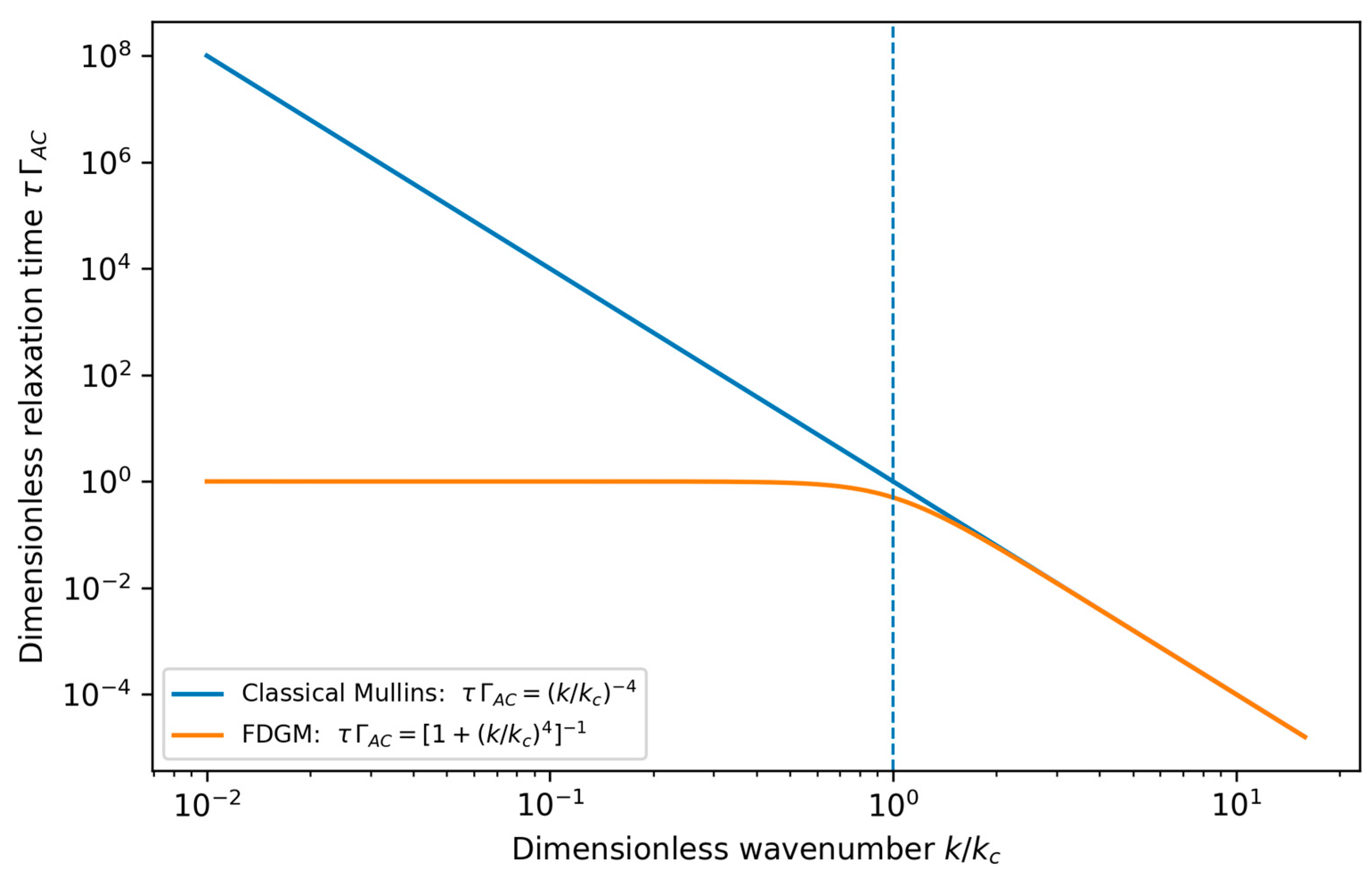

To make this effect explicit,

Figure 3 compares the mode-dependent relaxation time

in the classical Mullins limit and in the FDGM. While curvature-driven relaxation yields

and therefore extremely slow smoothing at long wavelengths, the FDGM introduces a finite field-controlled timescale such that

remains bounded by

for

. This provides a compact quantitative interpretation of the field-controlled “stability horizon” discussed above.

Importantly, the stability condition expressed by Equations (27)–(29) links morphological control to measurable process parameters through and . This connection enables predictive tuning of deposition conditions to achieve uniform surfaces, a capability absent from classical continuum models and phenomenological extensions thereof.

The stabilisation mechanism derived here constitutes the macroscopic manifestation of the same field-modified energetic landscape that governs nucleation, diffusion and coalescence at smaller scales. In the following section, we demonstrate how these processes can be unified within a single energy-minimisation argument spanning all relevant length scales.

The stabilisation mechanism derived here is thus consistent with experimentally relevant growth regimes, where surface diffusion, attachment–detachment and field-modified energetics act simultaneously.

Illustrative Example of Field-Induced Stabilization

To illustrate the quantitative impact of the field-induced stabilization term, consider a system with surface energy

, an effective surface diffusion coefficient

, and an applied field such that the field-induced relaxation rate satisfies

–

. These values are consistent with orders of magnitude reported in recent field-assisted deposition studies and modelling of electric-field-driven growth processes [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Under these conditions, the cutoff wavelength lies in the range of several tens to a few hundreds of nanometres, indicating that morphological fluctuations at length scales relevant for micro- and nanoscale devices can be efficiently damped during growth. This simplified example demonstrates how moderate external fields can exert substantial morphological control without altering growth temperature or chemical composition.

7. Unified Energy-Minimisation Argument Linking Nucleation, Diffusion, Coalescence and Stability

The analyses presented in

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 demonstrate that external fields influence thin-film growth across multiple length scales, from atomic nucleation events to continuum-scale surface stability. In this section, we show that these effects are not independent or phenomenological, but rather arise as consistent manifestations of a single underlying principle: the minimisation of a field-modified free-energy functional.

7.1. Variational Origin of Field-Driven Growth

Within the FDGM, thin-film evolution is governed by the total free energy

where the defining addition is the explicit field–matter interaction term

. The system evolves under non-equilibrium conditions, but its kinetics are still constrained to follow directions that reduce the instantaneous free energy, subject to deposition flux and thermal noise, and allowing for both conservative and non-conservative kinetic channels, consistent with variational and gradient-flow descriptions of surface evolution in non-equilibrium systems [

5,

6,

12]. The gradient-dynamics form introduced in

Section 2 ensures that the functional derivative of

acts as the unifying energetic driving force within the present framework.

From this perspective, the role of the external field is not to introduce a new, independent mechanism at each stage of growth, but to reshape the effective stability spectrum in which all growth processes take place. At the continuum scale, this reshaping appears explicitly as an additional non-conservative damping channel in the linear dispersion relation, producing a uniform downward shift of the growth rates and a pronounced enhancement of long-wavelength relaxation (small

). A direct consequence is that the relaxation time of large-scale surface modes becomes bounded by the field-controlled rate scale, rather than diverging as in purely curvature-driven Mullins relaxation. This field-induced acceleration of long-wavelength smoothing provides a compact quantitative interpretation of the “stabilisation horizon” introduced by the FDGM and is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The dashed line marks , where the diffusive and field-induced damping contributions are equal (). Although the two curves become visually indistinguishable only for , the crossover scale is defined physically by this equality.

7.2. Nucleation as Energy-Barrier Minimisation

At the atomic scale, nucleation corresponds to overcoming an energy barrier associated with the creation of new interfaces. In classical nucleation theory, this barrier is determined solely by surface energy and supersaturation. Within the FDGM, the field contribution lowers the total free energy of cluster configurations favourably oriented with respect to the field-induced energetic landscape, thereby reducing the effective nucleation barrier.

This modification follows directly from minimisation of : configurations in which the dipolar contribution reduces the total energy are statistically favoured. Field-assisted nucleation is therefore not an additional kinetic pathway, but the natural consequence of an altered energetic minimum.

7.3. Diffusion as Biased Descent in a Modified Energy Landscape

Surface diffusion can be viewed as a stochastic exploration of the local energy landscape by adatoms [

5,

6]. In the absence of fields, this landscape is isotropic, and diffusion proceeds with equal probability along symmetry-equivalent directions. The introduction of

breaks this isotropy by tilting the energy landscape in field-favoured directions.

As shown in

Section 4, the resulting anisotropic diffusion coefficients emerge because adatom hops that reduce the field-coupled energy experience lower activation barriers. Diffusion thus follows the steepest descent of the modified free energy, providing a direct link between microscopic field–matter interactions and mesoscopic mass transport.

7.4. Coalescence as Collective Energy Reduction

At the mesoscale, islands represent collective degrees of freedom whose interactions are governed by surface, strain and field energies. Directed coalescence arises when island configurations that minimise the combined energetic contributions are preferentially selected during growth, consistent with energetic descriptions of island coalescence and coarsening in thin films [

5,

6,

18].

From the unified perspective, the field-induced biases in island motion and reshaping can be interpreted as reflecting gradients of in the space of island configurations and attachment pathways, rather than as literal mechanical forces acting on islands in a uniform field. Texture selection, densification and aligned grain boundaries are therefore emergent consequences of collective energy minimisation under an externally modified landscape, mediated by anisotropic attachment–detachment kinetics and biased mass transport during coalescence.

7.5. Morphological Stability as Global Energy Damping

At the continuum scale, deviations of the surface profile from an energetically optimal configuration increase both surface energy and field-coupled energy. The additional stabilising term derived in

Section 6 reflects the system’s tendency to suppress such deviations through an effective non-conservative energetic damping channel.

The field-induced damping of long-wavelength surface modes can thus be interpreted as a global energetic penalty for large-scale height fluctuations. This mechanism enforces convergence toward a morphology that minimises

at the macroscopic level, complementing the local minimisation processes governing nucleation, diffusion and coalescence, in direct analogy with energetic stabilisation mechanisms in classical theories of surface relaxation and morphological stability [

5,

6,

12].

7.6. Multiscale Coherence of the FDGM

Taken together, these arguments establish that the FDGM is not a collection of independent or phenomenological field-induced effects, but a coherent multiscale theory. The same energetic term that biases atomic nucleation also governs diffusion anisotropy, directs island coalescence and stabilises continuum surface modes. Each growth stage can therefore be understood as a scale-specific expression of the same underlying variational principle.

This multiscale coherence distinguishes the FDGM from phenomenological models in which field effects are introduced separately at different stages of growth. By grounding all field-driven phenomena in a single free-energy functional, the FDGM provides conceptual clarity and a basis for predictive modelling.

8. Manufacturing Implications for Thin-Film-Based Devices

Although the Field-Driven Growth Model (FDGM) is formulated as a general theoretical framework, its implications are directly relevant to the manufacturing of advanced thin-film-based devices. By providing explicit energetic mechanisms and analytical stability criteria, the FDGM enables a shift from empirical optimisation toward a more predictive and physically grounded control of thin-film growth processes [

2,

8,

18].

8.1. Control of Nucleation Density Without Chemical Modification

In many manufacturing contexts, control of nucleation density is achieved by adjusting precursor chemistry, deposition rate or substrate temperature. These approaches often involve trade-offs between uniformity, throughput and compatibility with device integration. Within the FDGM, external fields provide an alternative control parameter: the nucleation barrier can, in appropriate regimes, be reduced directly through field–matter coupling, without modifying chemical composition or thermal budgets [

1,

2,

18].

This mechanism is particularly relevant for atomic layer deposition and chemical vapour deposition, where uniform nucleation across large areas and high-aspect-ratio structures is critical. Field-assisted nucleation offers a route to achieve conformal coatings and reduced incubation times while preserving process compatibility with temperature-sensitive substrates [

1,

2].

8.2. Engineering Diffusion and Texture via Field-Controlled Anisotropy

Surface diffusion strongly influences grain size, texture and surface roughness in physical vapour deposition techniques such as sputtering and pulsed-laser deposition. Classical strategies to control diffusion rely on substrate heating or intrinsic material anisotropy, both of which are often difficult to tune independently [

5,

6,

18].

The FDGM predicts that anisotropic diffusion can be externally controlled through the applied field, enabling directional mass transport without altering substrate temperature. This capability provides a theoretical basis for experimentally observed field-induced texture selection and grain alignment, and suggests that external fields may be used as an additional process knob to engineer microstructure in thin films for electronic, optical and sensing applications [

8,

18]. Recent demonstrations of electric-field-assisted microstructure control in oxide thin films further highlight the technological relevance of field-controlled energetic landscapes [

9].

8.3. Suppression of Large-Scale Roughness Through Field-Induced Stabilisation

Surface roughness at length scales comparable to device feature sizes can significantly degrade device performance, particularly in multilayer stacks and interfacial layers. Classical surface-diffusion-driven relaxation suppresses roughness only slowly at long wavelengths, limiting achievable smoothness during continuous growth [

5,

6]. Similar energetic–morphological correlations have been widely discussed in energetic condensation and plasma-assisted deposition contexts, where increased energy flux is known to suppress large-scale roughening and promote densification [

19].

While energetic condensation and plasma-assisted growth achieve roughness suppression through increased kinetic energy flux and localised energetic events, the stabilisation mechanism predicted by the FDGM arises from an explicit field–matter interaction that introduces a persistent restoring contribution to the free-energy landscape. Although both approaches lead to enhanced morphological uniformity, their physical origins and control parameters are fundamentally distinct, with the FDGM explicitly addressing field–matter coupling rather than kinetic energy flux effects.

Within the FDGM, the existence of a field-controlled stability cutoff wavelength establishes a quantitative criterion for suppressing long-wavelength roughening modes. By operating in regimes where the field-induced stabilisation dominates over curvature-driven relaxation, manufacturing processes can actively damp surface fluctuations that would otherwise persist. This mechanism provides a direct route towards thin films with improved uniformity without resorting to post-deposition planarization [

5,

6,

12].

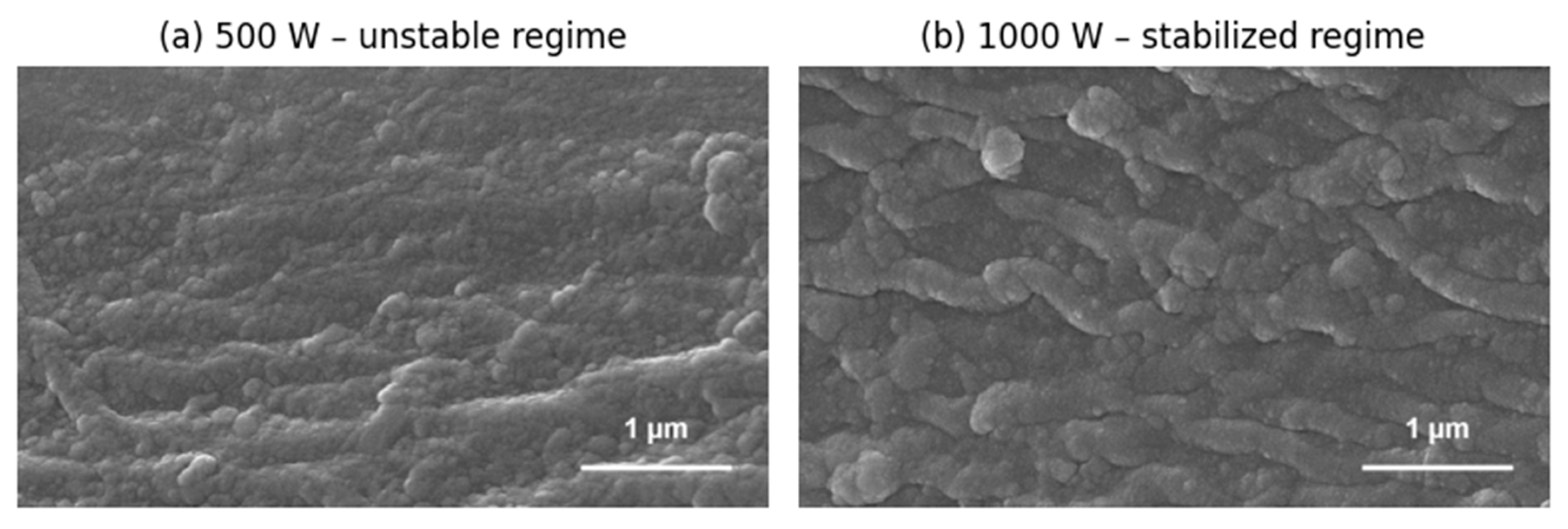

8.4. Qualitative Experimental Illustration

Although the Field-Driven Growth Model (FDGM) is formulated as a general theoretical framework, it is instructive to compare its qualitative predictions with representative morphological trends observed experimentally, without implying a direct one-to-one correspondence. While the applied power modifies the overall energetic conditions of growth rather than introducing a controlled external field, the resulting morphological trends provide a useful qualitative illustration of the stabilization mechanisms captured by the FDGM.

Figure 4 shows SEM images of TiO₂ thin films deposited by reactive DC magnetron sputtering under identical conditions, except for the applied power. The experimental procedure follows that described in detail in [

20]. At 500 W, the surface exhibits pronounced long-wavelength morphological modulations and anisotropic roughening, indicative of an energetically unstable growth regime. In contrast, films deposited at 1000 W display a markedly more homogeneous and isotropic morphology, with the suppression of large-scale surface undulations. These qualitative morphological signatures are consistent at the level of morphological trends with the type of energetic stabilization mechanisms predicted by the FDGM, particularly the suppression of long-wavelength surface modes discussed in

Section 6.

8.5. Process Integration and Scalability

An important advantage of field-assisted growth strategies is their compatibility with existing deposition platforms. External electric (and, in specific material systems, magnetic) fields can often be implemented through substrate biasing, electrode design or magnetic field coils, without substantial modification of reactor geometry or chemistry [

2,

8,

18].

The FDGM provides guidance on how such fields influence growth across length scales, enabling rational selection of field strength, orientation and temporal modulation to target specific morphological outcomes. Because the underlying energetic mechanisms are general, the framework applies across a wide range of materials systems and deposition techniques, supporting scalability from laboratory to industrial manufacturing environments [

1,

2,

18].

8.6. Implications for Thin-Film-Based Device Performance

By linking field parameters to nucleation density, diffusion pathways and morphological stability, the FDGM establishes a physically motivated connection between process conditions and device-relevant film properties. Improved surface uniformity, controlled texture and reduced defect density translate into enhanced electrical performance, optical quality and mechanical reliability in thin-film-based devices [

2,

8,

18].

In this sense, the FDGM does not merely rationalise observed field effects, but provides a physically motivated and predictive theoretical framework for integrating external fields as active control parameters in the manufacturing of next-generation thin-film-based technologies [

1,

2,

18].

9. Discussion

The Field-Driven Growth Model proposed in this work provides a unified theoretical framework for understanding how external electric (and, in specific material systems, magnetic) fields influence thin-film growth across multiple length scales. In this section, we discuss the implications of the FDGM in the context of existing growth theories, clarify its domain of validity, and highlight its conceptual and practical significance.

9.1. Positioning the FDGM Within Classical Growth Theory

Classical thin-film growth models have been remarkably successful in describing a wide range of phenomena under intrinsic growth conditions. Burton–Cabrera–Frank step-flow theory accurately captures terrace and step dynamics during epitaxial growth, classical nucleation theory describes island formation as a balance between surface energy and supersaturation, and Mullins-type models explain curvature-driven surface relaxation through surface diffusion. However, a common and fundamental assumption underlying all these approaches is that the energetic landscape governing growth is unaffected by external fields under intrinsic growth conditions [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The FDGM departs from this assumption by explicitly incorporating field–matter interactions into the free-energy functional. This modification does not invalidate classical theories; rather, it extends them. In the absence of external fields, the FDGM reduces naturally to standard growth models. When fields are present, the same energetic framework predicts additional field-dependent energetic contributions that bias nucleation, diffusion, coalescence and morphological stability in a consistent manner. This continuity with established theory is an important strength of the model [

3,

5,

6].

9.2. Comparison with Edwards–Wilkinson and KPZ Frameworks

Continuum growth models such as the Edwards–Wilkinson (EW) and Kardar–Parisi–Zhang (KPZ) equations have played a central role in understanding kinetic roughening and scaling behaviour of growing interfaces [

6,

10]. The EW equation describes linear diffusive relaxation with stochastic noise, while the KPZ equation introduces a nonlinear term associated with lateral growth, leading to non-Gaussian scaling and roughening.

Within these frameworks, anisotropy and instability arise from intrinsic surface properties, nonlinearities or noise, rather than from externally controllable parameters. Although extensions of EW and KPZ can include anisotropic coefficients, such anisotropy is typically static and material-specific. In contrast, the FDGM introduces an externally tunable stabilisation mechanism that directly suppresses long-wavelength roughening modes through a field-controlled energetic term. This mechanism is fundamentally different from the nonlinear roughening captured by KPZ-type dynamics and cannot be reproduced by adjusting kinetic coefficients alone.

From a universality perspective, the FDGM suggests the existence of a field-driven growth regime in which external fields alter the effective scaling behaviour of the interface. While a full renormalisation-group analysis is beyond the scope of the present work, the analytical suppression of long-wavelength modes indicates that field-assisted growth may not be fully captured within traditional EW or KPZ universality classes [

6,

10]. Recent phase-field modelling studies have similarly demonstrated that external electric fields can modify the energetic landscape governing thin-film crystallization and stability, leading to field-controlled morphological outcomes [

21].

9.3. Relation to Slope-Dependent Diffusion Models

The Wolf–Villain model and related slope-dependent diffusion frameworks [

11] capture important aspects of mound formation and kinetic roughening by introducing diffusion currents that depend on local surface slope. These models successfully describe intrinsic instabilities arising from surface geometry and step-edge barriers.

However, slope-dependent diffusion models treat anisotropy as an emergent property of the surface itself, not as an externally controllable parameter. In contrast, the anisotropic diffusion predicted by the FDGM arises directly from field–matter coupling and can be dynamically tuned through the magnitude, orientation or temporal modulation of the applied field. This distinction is critical for manufacturing applications, where external control parameters offer greater flexibility than intrinsic material constraints [

11], and where energetic rather than purely geometric anisotropy is experimentally accessible.

9.4. Multiscale Coherence and Predictive Capability

A central contribution of the FDGM is its multiscale coherence. The same field-dependent energetic term governs atomic-scale nucleation, mesoscale diffusion and coalescence, and continuum-scale morphological stability. This coherence addresses a long-standing gap in the literature, where field-induced effects are often explained independently at different scales using unrelated mechanisms in the existing thin-film growth literature [

10,

11,36].

By grounding all field effects in a single free-energy functional, the FDGM provides a predictive theoretical basis, rather than purely post hoc interpretation. The analytical stability condition derived for continuum surface modes offers a concrete example: it links measurable process parameters to morphological outcomes in a way that is not accessible within classical growth models [

5,

6,

10,

11].

9.5. Limitations and Scope of Applicability

Like any theoretical framework, the FDGM has limitations. The model assumes moderate field strengths, where linear polarization and dipolar coupling provide an adequate description of field–matter interactions, and where the dominant energetic contributions can be consistently expanded to leading order in the field amplitude. At very high field intensities, nonlinear effects, field-induced desorption or plasma-specific phenomena may become important and require additional terms [

10,

11].

Furthermore, the continuum analysis neglects explicit nonlinearities in the surface evolution equation, such as those associated with strong lateral growth or shadowing effects. While the present formulation captures the dominant stabilizing influence of external fields, future extensions may incorporate nonlinear terms to explore the interplay between field-induced damping and kinetic roughening in greater detail [

6,

10].

While the present formulation is most directly applicable to electric fields acting on polarizable surface species, extension to magnetic fields requires the presence of magnetic moments or susceptibilities and is therefore material-dependent.

In addition, the FDGM describes an averaged, statistical growth regime appropriate for continuum and mesoscale descriptions, in which external fields act primarily by modifying energetic barriers and introducing weak but persistent restoring contributions. While recent experimental and modelling studies confirm that such mechanisms operate under realistic deposition conditions [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17], the model is not intended to capture growth phenomena dominated by highly localized high-energy events, electrical breakdown, or strongly nonlinear plasma effects. In such regimes, a more detailed kinetic, plasma-specific or electrodynamic description would be required to account for transient, non-equilibrium processes beyond the scope of the present energetic framework.

Finally, the FDGM is formulated as a general framework and does not explicitly account for material-specific electronic or magnetic properties. Incorporating such effects may further refine predictions for particular materials systems but does not alter the core energetic principle underlying the model [

10,

11].

9.6. Broader Implications

Despite these limitations, the FDGM offers a new perspective on field-assisted thin-film growth. It explains why similar field-induced ordering phenomena are observed across disparate deposition techniques and materials systems [

1,

2,

8,

18], and it provides a conceptual foundation for treating external fields as active control parameters rather than secondary process conditions.

By unifying nucleation, diffusion, coalescence and stability within a single energetic framework, the FDGM bridges the gap between empirical observations and predictive manufacturing theory. This positioning suggests that field-assisted growth should be viewed not merely as a special case of classical thin-film deposition, but as a distinct regime of non-equilibrium growth with its own governing principles.

10. Conclusions

In this work, we have introduced the Field-Driven Growth Model (FDGM) as a unified theoretical framework for thin-film growth under external electric fields (and, in material-dependent cases, magnetic fields). By explicitly incorporating field–matter interactions into the free-energy functional governing growth, the FDGM provides a physically grounded and internally consistent description of how external fields influence thin-film morphology across multiple length scales.

Starting from a general energetic formulation, we showed that the inclusion of a field-dependent term modifies the fundamental processes of nucleation, surface diffusion and island coalescence in a coherent manner. Field-assisted nucleation emerges naturally from a field-dependent reduction of the nucleation barrier, anisotropic surface diffusion arises from direction-dependent modification of diffusion activation energies, and directed coalescence results from field-induced energetic biases at the mesoscale. At the continuum level, these effects culminate in a field-induced stabilization mechanism that suppresses long-wavelength roughening modes and defines a field-controlled morphological stability cutoff.

A central contribution of the FDGM is the demonstration that these apparently distinct phenomena are not independent mechanisms, but multiscale manifestations of a single underlying principle: the minimization of a field-modified free-energy landscape under non-equilibrium growth conditions. This multiscale coherence distinguishes the FDGM from phenomenological or scale-specific models and provides a transparent physical interpretation of field-assisted growth.

By deriving explicit analytical stability conditions and linking them to measurable process parameters, the FDGM offers predictive capability that is absent from classical growth theories and their extensions. In particular, the identification of a field-controlled cutoff wavelength provides a quantitative criterion for suppressing large-scale roughness during growth, with direct implications for the manufacturing of uniform thin films.

The framework developed here is broadly applicable to a wide range of deposition techniques, including sputtering, pulsed-laser deposition, chemical vapor deposition and atomic layer deposition. By treating external fields as active control parameters rather than secondary perturbations, the FDGM establishes a theoretical foundation for rational design of field-assisted manufacturing strategies in advanced thin-film-based devices.

Future work may extend the FDGM to include nonlinear surface evolution terms, strong-field regimes and explicit material-specific electronic or magnetic responses, as well as to explore scaling behavior through numerical simulations. Nevertheless, the present formulation already captures the essential physics underlying field-driven thin-film growth and provides a robust basis for both experimental interpretation and process optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C.V., M.G.M. and T.E.; methodology, H.C.V. and T.E.; software, H.C.V.; validation, H.C.V., M.G.M. and T.E.; formal analysis, H.C.V. and T.E.; investigation, H.C.V.; resources, M.G.M.; data curation, H.C.V. and T.E.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.V.; writing—review and editing, H.C.V., M.G.M. and T.E.; visualization, H.C.V. and T.E.; supervision, M.G.M. and T.E.; project administration, H.C.V.; funding acquisition, M.G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for the generation of Figure 1. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Units |

| h(r,t) |

surface height field |

m |

| r |

in-plane position vector |

m |

| t |

time |

s |

| E(t) |

applied electric field |

V m⁻¹ |

| P(r) |

effective polarization density of near-surface species |

— |

| α, αₑ |

effective polarizability |

C m² V⁻¹ |

| ΔU |

induced-dipole interaction energy |

J |

| G(r) |

cluster formation free energy (no field) |

J |

| Gₜₒₜ(r) |

cluster formation free energy (with field) |

J |

| r |

cluster radius |

m |

| rc

|

critical radius |

m |

| ΔG* |

nucleation barrier (no field) |

J |

| ΔG*ₑff

|

effective nucleation barrier (with field) |

J |

| J(E) |

nucleation rate (field-dependent) |

— |

| pₑff

|

effective barrier-bias parameter |

J (V m⁻¹)⁻¹ |

| λ |

geometric factor (shape/partial wetting/orientation) |

– |

| Ed

|

diffusion barrier (no field) |

J |

| Ed,eff(θ) |

field-modified diffusion barrier |

J |

| β |

diffusion–field coupling parameter |

J (V m⁻¹)⁻¹ |

| Ds

|

surface diffusion constant |

m² s⁻¹ |

| D(θ,E) |

anisotropic, field-dependent diffusivity |

m² s⁻¹ |

| γ |

surface energy |

J m⁻² |

| Ω |

atomic volume |

m³ |

| kB

|

Boltzmann constant |

J K⁻¹ |

| T |

temperature |

K |

| ν |

surface-diffusion smoothing coefficient (prefactor of ∇⁴h) |

m⁴ s⁻¹ |

| ΓAC

|

field-induced relaxation rate |

s⁻¹ |

| η(r,t) |

stochastic noise term |

— |

| k |

wavenumber |

m⁻¹ |

| kc

|

crossover wavenumber, kc = (ΓAC / ν)1/4

|

m⁻¹ |

| ∇², ∇⁴ |

Laplacian / biharmonic operator (in-plane) |

m⁻², m⁻⁴ |

Appendix A. Why an Induced (Quadratic) Polarization Energy Can Be Represented as an Effective Directional Barrier Bias

In linear response, the polarization of a surface species can be written as

, which yields the familiar induced-polarization energy

Kinetics, however, depend on free-energy differences. The field-dependent contribution to the activation free energy is the difference between the transition-state (TS) and metastable initial (i) configurations:

A convenient generic representation of the field-coupled energy of a configuration includes both an induced (quadratic) term and a possible effective dipolar (linear) term:

where

denotes an effective (possibly environment-induced) dipole moment and

an effective polarizability. Therefore, the barrier shift can be written as

with

and

. Differences in

and/or

naturally arise because the TS and the initial configuration can have different local bonding, charge redistribution, geometry, or orientation relative to the field.

For practical modeling over a restricted process window (i.e., a limited range of applied fields relevant to thin-film manufacturing), it is often useful to recast the field dependence into a compact effective directional bias of the form used in Equations (9)–(10):

where

is a geometric factor (shape/orientation/partial wetting) and

absorbs the microscopic pathway dependence. In particular, one may interpret

and, over a narrow field range around a representative operating point

, treat

as approximately constant (or equivalently linearize the quadratic contribution about

). Importantly, this representation does not claim that an induced dipole in a strictly uniform field produces a fundamental linear coupling; rather, it is an effective barrier-bias parametrization of field-induced asymmetry between competing nucleation pathways.

References

- Thornton, J.A. High Rate Thick Film Growth. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1977, 7, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.J.; Arnell, R.D. Magnetron Sputtering: A Review of Recent Developments and Applications. Vacuum 2000, 56, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, W.K.; Cabrera, N.; Frank, F.C. The Growth of Crystals and the Equilibrium Structure of Their Surfaces. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 1951, 243, 299–358. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, W.W. Flattening of a Nearly Plane Solid Surface Due to Capillarity. J. Appl. Phys. 1959, 30, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, W.W. Theory of Thermal Grooving. J. Appl. Phys. 1957, 28, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, J.A.; Spiller, G.D.T.; Hanbücken, M. Nucleation and Growth of Thin Films. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1984, 47, 399–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.; Myśliwiec, J. Recent Advances in Magnetron Sputtering: From Fundamentals to Industrial Applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.A.; Lichtenberg, A.J. Principles of Plasma Discharges and Materials Processing, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Electric-Field-Assisted Growth and Microstructure Control of Oxide Thin Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.F.; Wilkinson, D.R. The Surface Statistics of a Granular Aggregate. Proc. R. Soc. A 1982, 381, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardar, M.; Parisi, G.; Zhang, Y.C. Dynamic Scaling of Growing Interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 56, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feibelman, P.J. Surface Electromagnetic Fields and Adsorbate Interactions. Prog. Surf. Sci. 2002, 71, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, M.; Grüner, G. Electrodynamics of Solids: Optical Properties of Electrons in Matter. Ann. Phys. 2002, 11, 301–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; et al. Effect of an Electric Field during the Deposition of Silicon Dioxide Thin Films by Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 2089–2102. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Fischer, T.; Mathur, S. Field-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition: New Perspectives for Thin Film Growth. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 20104–20142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, A. Approaches to Rid Cathodic Arc Plasmas of Macro- and Nanoparticles: A Review. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 200, 1893–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Electric-Field-Induced Crystallization of Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 Thin Films Based on Phase-Field Modeling. npj Quantum Mater. 2024, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.E.; Villain, J. Growth with Surface Diffusion. Europhys. Lett. 1990, 13, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Boxman, R.L.; Sanders, D.M.; Martin, P.J. Cathodic Arc Deposition: A Review of Plasma Physics and Coating Properties. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 1995, 13, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleutério, T.; Sério, S.; Vasconcelos, H.C. Growth of Nanostructured TiO2 Thin Films onto Lignocellulosic Fibers through Reactive DC Magnetron Sputtering: A XRD and SEM Study. Coatings 2023, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.-Q.; Shen, J. Phase-Field Modeling of Electric-Field-Induced Phase Transformations in Ferroelectric Thin Films. Acta Mater. 2018, 145, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |