0. Introduction

The rise of digital imaging technology has fundamentally transformed how individuals engage with digital content and their surrounding environments [

24], directly enabling the development of advanced immersive experiences such as virtual and augmented reality. A critical requirement for these platforms is the ability to capture complex scenes from multiple viewpoints to provide users with continuous, seamless panoramic visuals. This is typically achieved by synthesizing and merging image data acquired simultaneously from two or more cameras in a process known as image stitching. Most image stitching methods establish correspondences between images using salient visual features [

6,

7,

21,

22,

23]. These correspondences define a geometric transformation that is used to warp images into a common coordinate frame. The final panorama is then obtained by merging overlapping regions, either directly or with additional mechanisms such as seam selection or blending to reduce visual artifacts. Contributions in the state-of-the-art are most often focused on the refinement or acceleration of one or more of these individual stages.

Geometric warping plays a central role in stitching quality, with homography remaining the dominant transformation model. Owing to its eight degrees of freedom, homography can accurately model full perspective effects and provides exact alignment for planar scenes or pure camera rotations. However, real-world scenes are rarely planar and often contain significant depth variation. In such cases, homography attempts to reconcile non-planar motion using a planar model, leading to over-flexible geometric distortions such as stretching, bending of straight lines, and shape deformation.

A large body of work in image stitching focuses on improving geometric alignment through increasingly flexible warping models. Hybrid deformation models [

18] estimate multiple homographies for different scene regions or depth layers to better preserve structural consistency. Other methods replace global homography with local spline-based registration, such as thin-plate spline (TPS) warps, to increase alignment flexibility [

13,

25]. While these approaches often improve overlap alignment, their additional degrees of freedom frequently introduce excessive geometric deformation, leading to stretched textures, bent lines, and loss of structural realism. Even combinations of homographic and affine transformations [

16] reduce but do not eliminate these artifacts, particularly in scenes with strong parallax.

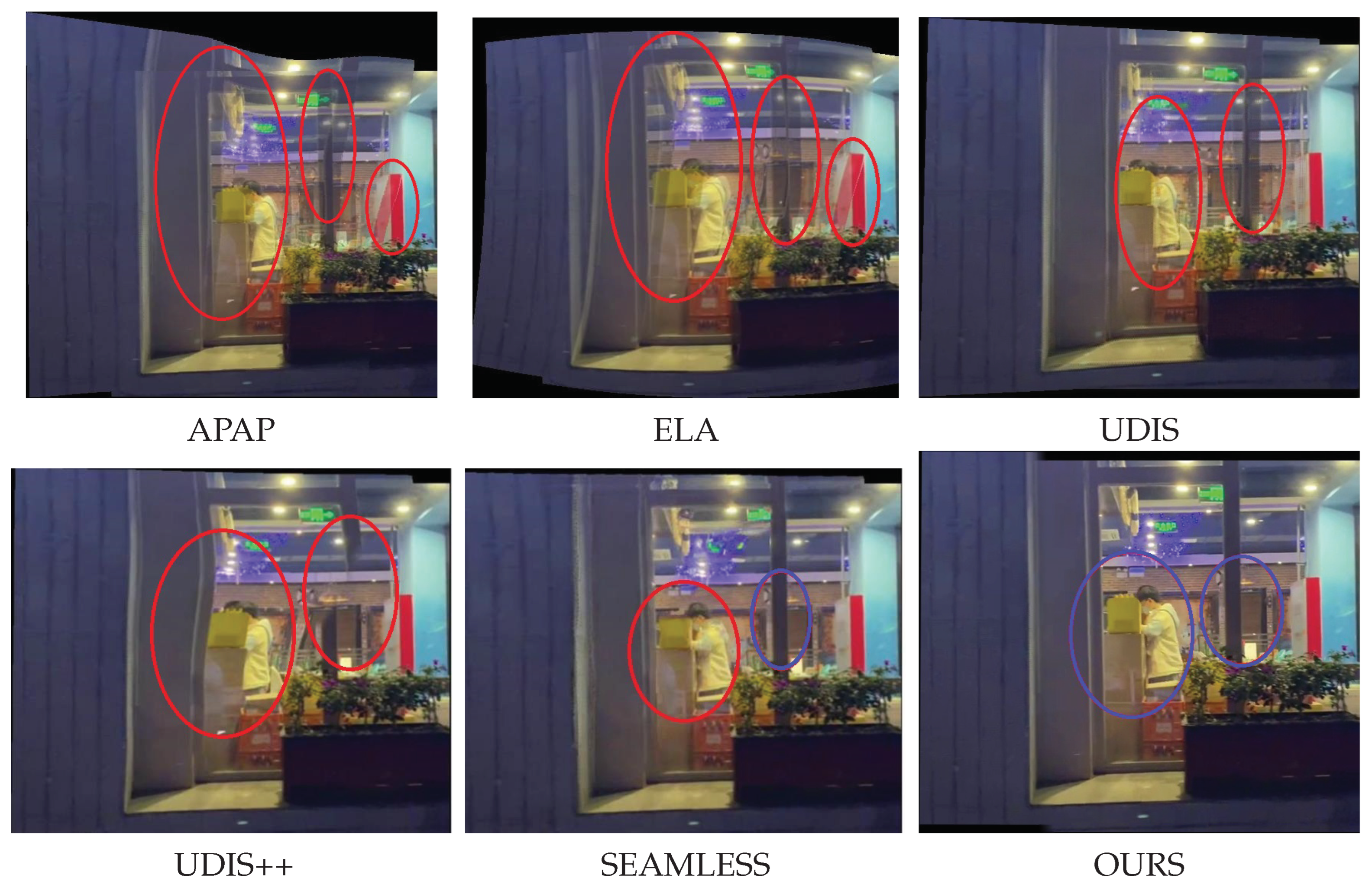

Figure 1 illustrates these limitations in representative state-of-the-art methods (e.g., APAP [

9], ELA [

29], UDIS [

19], UDIS++ [

13], and SEAMLESS [

25]), where visual artifacts such as ripples, ghosting, and information loss are evident (highlighted in red). These artifacts primarily arise from the inherent tendency of homography-based models to compensate for depth induced parallax through non-physical geometric distortions.

In parallel, many stitching methods address misalignment artifacts not by correcting geometry, but by carefully selecting where images are merged. Seam-based approaches define a stitching path through the overlapping region that minimizes visual discrepancy according to a predefined cost function. Representative works [

15,

26,

27,

28] guide seam placement using cues such as intensity differences, gradients, semantic labels, or feature consistency. Although effective in visually hiding some misalignments, these methods often rely on heavy preprocessing pipelines—including semantic segmentation, feature classification, or depth inference which increase computational cost and sensitivity to errors. Furthermore, seam optimization alone does not guarantee geometric consistency across the seam, leaving duplication or ghosting unresolved in many cases.

Overall, stitching methods still face three major challenges. First, global or overly flexible warps (e.g., homography-only or spline-based models) often introduce geometric distortions and compromise structural fidelity. Second, seam selection strategies based on cost-function minimization frequently depend on complex preprocessing steps such as semantic segmentation or feature classification, which increases sensitivity to inaccuracies. Third, even when alignment is locally accurate, blending across regions often lacks consistency, leading to duplication, stretching, or ghosting that reduce the visual realism of the stitched panorama.

This work addresses the above limitations through three contributions. (1) We introduce a hierarchical deformation strategy that combines global affine initialization (using RANSAC-filtered correspondences), local affine refinement within the overlap region, and a smooth free-form deformation (FFD) field regulated by seamguard adaptive smoothing. This multi-scale design preserves structural fidelity while avoiding the excessive distortions of global models and the instability of spline-based warps. (2) within the same seam-selection paradigm, we propose an adequate zone detection strategy that departs from prior methods based on semantic segmentation. Instead of such complex preprocessing, we analyze the disparity consistency of feature correspondences, providing a lightweight, model-free criterion that robustly identifies parallax-minimized regions. (3) we perform anchor-based segmentation aligned with the detected adequate zone, ensuring structural consistency across image pairs and enabling seamless stitching. Unlike prior approaches that stop at defining a seamline and then rely on blending to hide artifacts, our method partitions both images into corresponding vertical slices anchored by refined keypoints. This guarantees one-to-one geometric correspondence across segments, reducing duplication and ghosting in the final panorama.

1. Related Work

Research in image stitching has explored a wide range of strategies, from feature-based methods to deep learning approaches, yet three major limitations persist across the state-of-the-art.

Overall, prior methods still face three major challenges: (1) global or overly flexible warps compromise structural fidelity and introduce geometric distortions; (2) seam selection strategies based on cost-function minimization often rely on complex preprocessing steps (like semantic segmentation or feature classification), increasing sensitivity to inaccuracies that reduce the visual realism of the stitched panorama; and (3) dependence on strong scene assumptions (planarity, dual planes, or consistent surface normals).

2. Seamless and Structurally Consistent Image Stitching

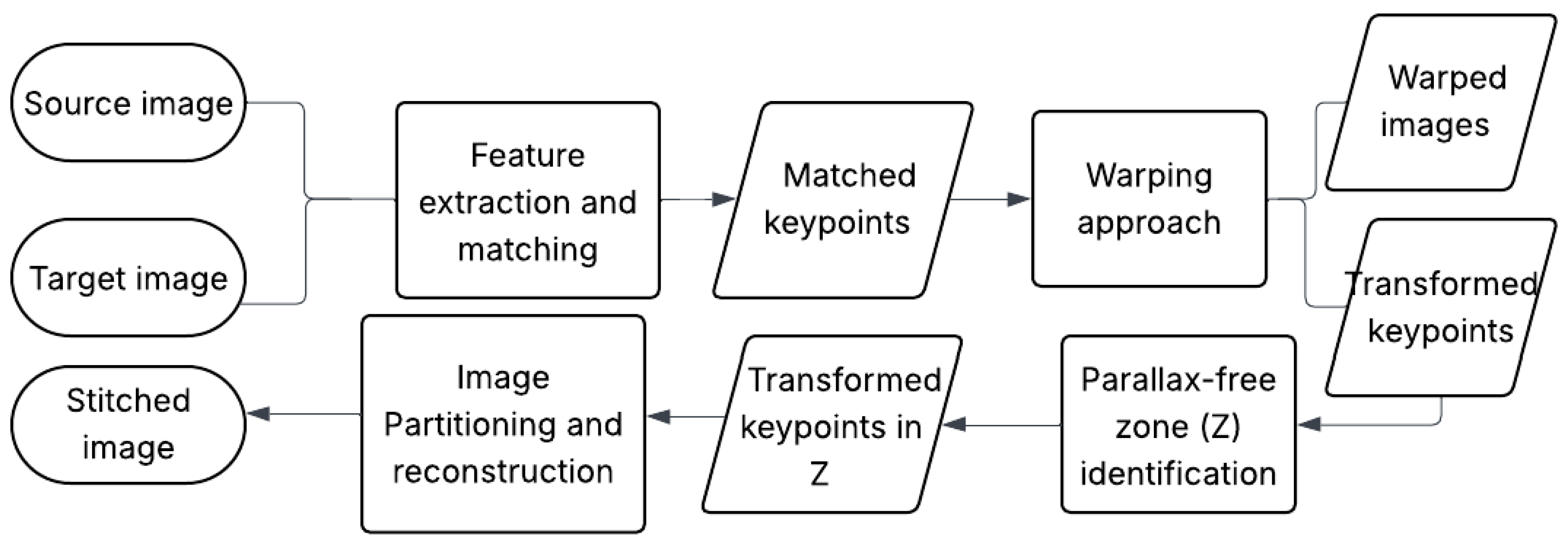

To overcome the excessive distortion and misalignment common in image stitching, we propose a three-stage framework that emphasizes local adaptability, geometry-driven parallax handling, and structurally consistent reconstruction. The method transforms the source image into the domain of the target image while rigorously preserving geometric structure.

2.1. The Three Stage Framework

Local Image Warping: We deliberately move beyond global homographies and spline-based deformations. The source image is coarsely aligned using a global affine transformation (estimated via RANSAC). This is followed by a refinement stage where the overlap is subdivided into local grids, and distinct affine models are fitted to local feature correspondences. This process generates a Smooth Free-Form Deformation (FFD) field, which is blended and adaptively smoothed using a seamguard strategy that utilizes a ramp mask and match density weighting to prevent discontinuities at boundaries. This preserves overall structural fidelity while reducing geometric distortion.

Adequate Parallax Minimized Zone Identification: In contrast to seam selection methods relying on semantic segmentation, we introduce a model free strategy. This method analyzes disparity variations and geometric consistency among matched features to isolate a stable stitching zone that inherently minimizes parallax artifacts.

Image Partitioning and Reconstruction: Within the identified stable zone, an ordered chain of refined keypoints defines the optimal stitching line. Both images are then partitioned into corresponding vertical slices anchored by these keypoints. This anchor-based segmentation enforces structural consistency between the two images by construction: every vertical slice in one image has a direct, aligned counterpart in the other. By tying the seamline to these geometric anchors, our method eliminates the duplication, ghosting, and misalignment issues often associated with blending.

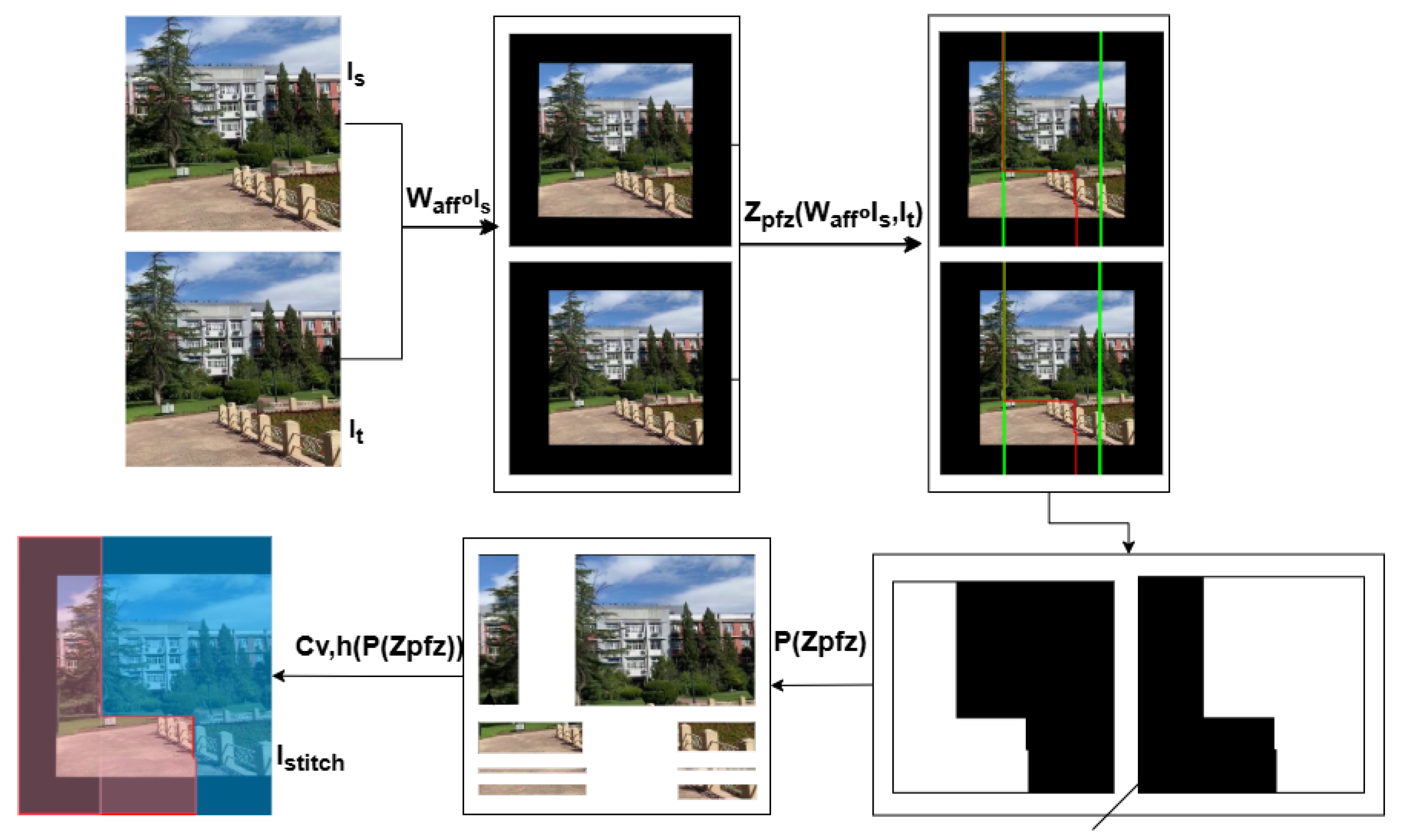

The overall flow of the proposed method is provided in

Figure 2.

2.2. Locally Adaptive Image Warping

Our approach generates a content-aware, seam-guarded deformation field to precisely align a source image () to a target image () using only sparse feature matches. The pipeline is structured in six sequential steps, strategically combining global alignment with local adaptivity. This methodology ensures both structural fidelity and robustness through confidence-weighted blending and specific gating mechanisms.

Step 1: Global Affine Estimation via RANSAC

We begin by detecting, extracting, and matching features using the XFeat algorithm [

23], which is selected for its effective balance between computational efficiency and matching accuracy. From the resulting set of matched keypoints

, we compute a robust global affine transformation

using the RANSAC algorithm. This initial step serves two critical functions: establishing a coarse alignment and filtering outliers. Only the inlier matches, as determined by RANSAC, are retained for all subsequent local refinement steps.

Step 2: Overlap Region and Local Grid Cell Generation

This step defines the area of alignment and prepares it for localized warping.

Using the global affine transformation , the four corners of the source image () are projected into the coordinate space of the target image (), creating a quadrilateral. This quadrilateral is then clipped to the bounds of using the Sutherland-Hodgman algorithm to precisely define the polygonal overlap region. A binary mask, , is generated from this resulting polygon.

Next, a uniform grid is overlaid onto the bounding box of this overlap region. For each resulting grid cell (), the following parameters are computed:

A binary mask , derived from the intersection of the grid cell with .

A centroid , calculated using image moments.

A bounding box (), utilized for subsequent spatial weighting and diagnostics.

Step 5: Seam Guarding via Dual-Channel Gating

The final step in suppressing artifacts near boundaries or in sparse regions is the modulation of the full-resolution deformation field using a multiplicative gate () derived from two primary signals:

Geometric Ramp (): A smootherstep function applied to the signed distance field of the overlap region, with bandwidth proportional to image diagonal ().

Match Density Map (): A Gaussian-blurred heatmap of inlier keypoint locations, normalized to , with kernel standard deviation ().

Dual-Gated Seam Suppression

The final gating mask combines both signals multiplicatively:

where

is the smootherstep function,

controls ramp steepness, and

is the minimum gate value. The guarded deformation field is then smoothed:

This is not post-warp blending; rather, it is a mechanism for pre-warp suppression of unreliable deformations. The final displacement field

is modulated by the gate

G:

This multiplicative gating ensures that the full-resolution displacement is only applied in geometrically stable and feature-supported areas. The combination of geometric and photometric (match-density based) gating for Free-Form Deformation (FFD) fields is, to our knowledge, unprecedented in the image stitching literature.

Step 6: Final Warping and Output

The final source-to-canvas mapping is computed by combining the inverse global affine transformation with the gated deformation field. The source image is then warped into the final canvas space using bilinear interpolation. Concurrently, the target image is pasted onto the output canvas using the pre-computed offset .

For evaluation purposes, the final transformed coordinates of the original inlier matches are computed. This involves a simple translation to canvas coordinates for target points and applying the full warp (global affine + FFD + multiplicative gate) with bilinear interpolation of the displacement field for source points.

These collective innovations enable our method to produce seamless, artifact-free alignments even when operating with sparse, uneven, or noisy feature matches.

2.3. Optimal Stitching Line

2.3.1. Determination of an Adequate Parallax-Free Zone

Identifying an adequate stitching area relies on finding a region containing a high density of reliable feature correspondences governed by a dominant geometric transformation. Initially, regions with low information content, which are quantifiable by low local image variance, are systematically excluded as they produce unstable matches. However, scenes with significant depth often exhibit motion parallax, resulting in a multi-modal distribution of disparity vectors that complicates the search for a consistent seam.

To robustly handle this parallax, our method focuses on isolating the most extensive and stable surface. This is achieved by identifying the dominant motion group, which corresponds to the true inliers for a stable stitch. Specifically, the algorithm locates regions where keypoint disparities are statistically consistent (exhibiting low local variance) and where their local mean converges to the global mean of the primary motion mode. This approach allows the algorithm to robustly handle parallax by isolating the most extensive and stable surface.

Given a set of matched keypoint pairs ((),()), where and denote the coordinates in the source image and and denote the coordinates in the target image, respectively, keypoints are initially sorted using two primary spatial criteria to account for the camera geometry.

First, , reflecting the relative frontal position of the camera of the source image.

, for one camera physically positioned above the other in most cases.

The matched keypoints are partitioned into classes based on their abscissa values (x-coordinates). Each class corresponds to a spatial range, R, which is defined as R=width/20. For every keypoint within a class, we compute its disparity as () and subsequently calculate the mean disparity for that class.

We then iterate through the resulting list of mean disparities (one value per class) and group the corresponding classes into clusters based on the statistical consistency of these mean disparity values. This clustering process isolates the most dominant motion groups, enabling the identification of the parallax-minimized "adequate zone."

|

Algorithm 1: Threshold-Based Disparity Clustering. |

-

Require:

D: A list of mean disparities , where corresponds to the mean disparity of class i. -

Require:

v: A positive, user-defined threshold value for disparity difference. -

Ensure:

C: A set of clusters, where each cluster is a list of consecutive classes from D. - 1:

Initialize an empty list of clusters C

- 2:

Initialize the current cluster with the first class

- 3:

for to n do

- 4:

if then

- 5:

Add class i to

- 6:

else

- 7:

if contains at least two classes then

- 8:

Add to the list of clusters C

- 9:

end if

- 10:

Start a new cluster with class i:

- 11:

end if

- 12:

end for - 13:

if contains at least two classes then

- 14:

Add to the list of clusters C

- 15:

end if - 16:

returnC

|

The optimal stitching cluster is selected based on a scoring metric that evaluates the consistency and reliability of each cluster against three key parameters:

Standard Deviation (): This measures the internal coherence of the cluster. A smaller standard deviation indicates that the individual class mean disparities are tightly grouped around the cluster mean, suggesting a more consistent depth plane.

Cardinality (): This is the total number of keypoints contained within all classes of the cluster. High cardinality indicates that the cluster is supported by a large amount of data, which directly increases the reliability and robustness of its mean disparity calculation.

Disparity Deviation (): This is defined as the absolute difference between the mean disparity of the cluster () and the global mean disparity of all classes ().

To prevent the selection of clusters with low reliability (low cardinality), high incoherence (high standard deviation), or minimal deviation from the global mean (low significance), we define a weighted score,

, for each cluster k given by Equation

5.

where:

: standard deviation of the disparities within the cluster,

C: cardinality (number of keypoints in the cluster),

: weighting factor controlling the influence of the disparity deviation,

: absolute difference between the mean disparity of the cluster and the global mean disparity ,

: a small constant added to avoid division by zero.

The cluster with the highest calculated score, , is selected as the optimal cluster. The "adequate zone" is then defined as the combination of all the classes within this selected cluster.

2.3.2. Keypoint Chain Refinement

Once an adequate overlapping area is identified, the initial set of keypoint correspondences cannot be used directly, as this raw data is inherently unreliable and contains significant outliers or misaligned matches. Using these erroneous points to guide partitioning would create inconsistent divisions between the two images, leading directly to visible stitching artifacts such as ghosting and duplications. Therefore, refining this initial set of keypoints is a critical prerequisite.

A dedicated algorithm is employed to generate two clean, synchronized, and ordered lists of keypoints, forming a coherent "keypoint chain". For brightness consistency, a selection step is performed, determining each keypoint’s intensity and retaining only those with similar levels. An initial anchor is established at the keypoint closest to the image edge. From there, the algorithm iteratively matches each point in the first image with its closest corresponding point in the second based on Euclidean distance. A crucial constraint is applied during this process: each match must be unique in its horizontal (x) position. This filtering step prunes the ambiguous or conflicting matches that cause structural inconsistencies, yielding a refined set of high-confidence pairs.

The optimal stitching line in each image is defined by the path connecting the first element to the last element of the refined set in the corresponding pair.

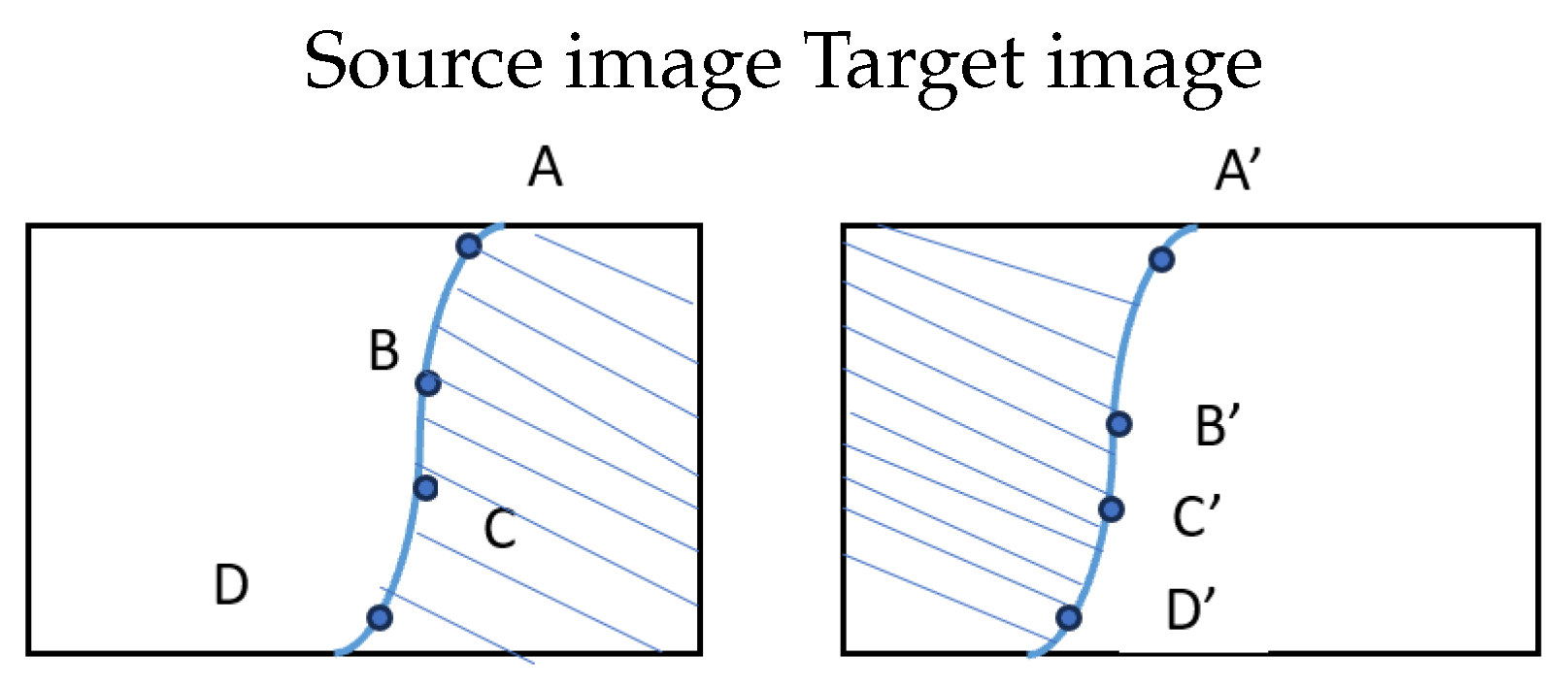

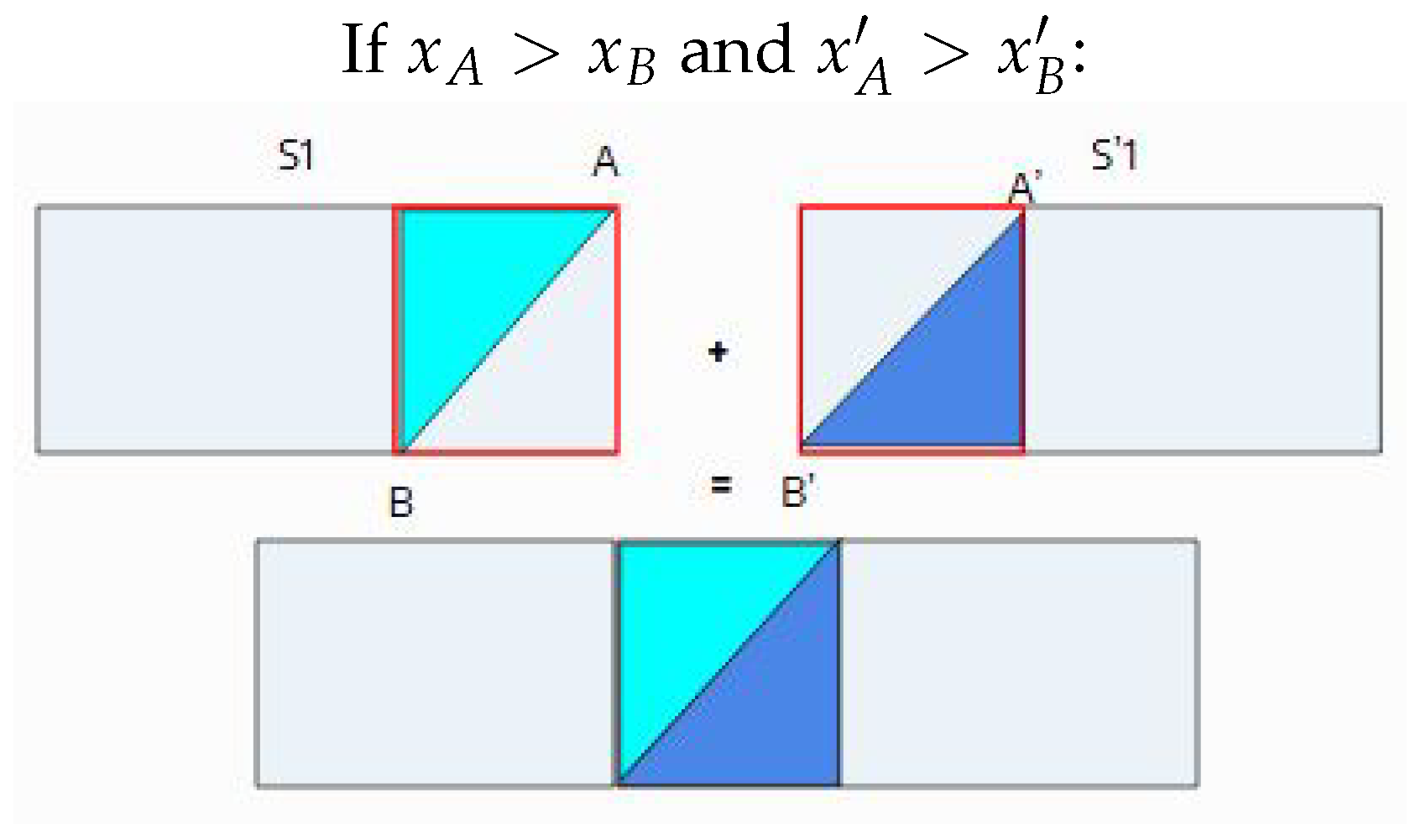

2.4. Partitioning and Reconstruction

2.4.1. Image Partitioning

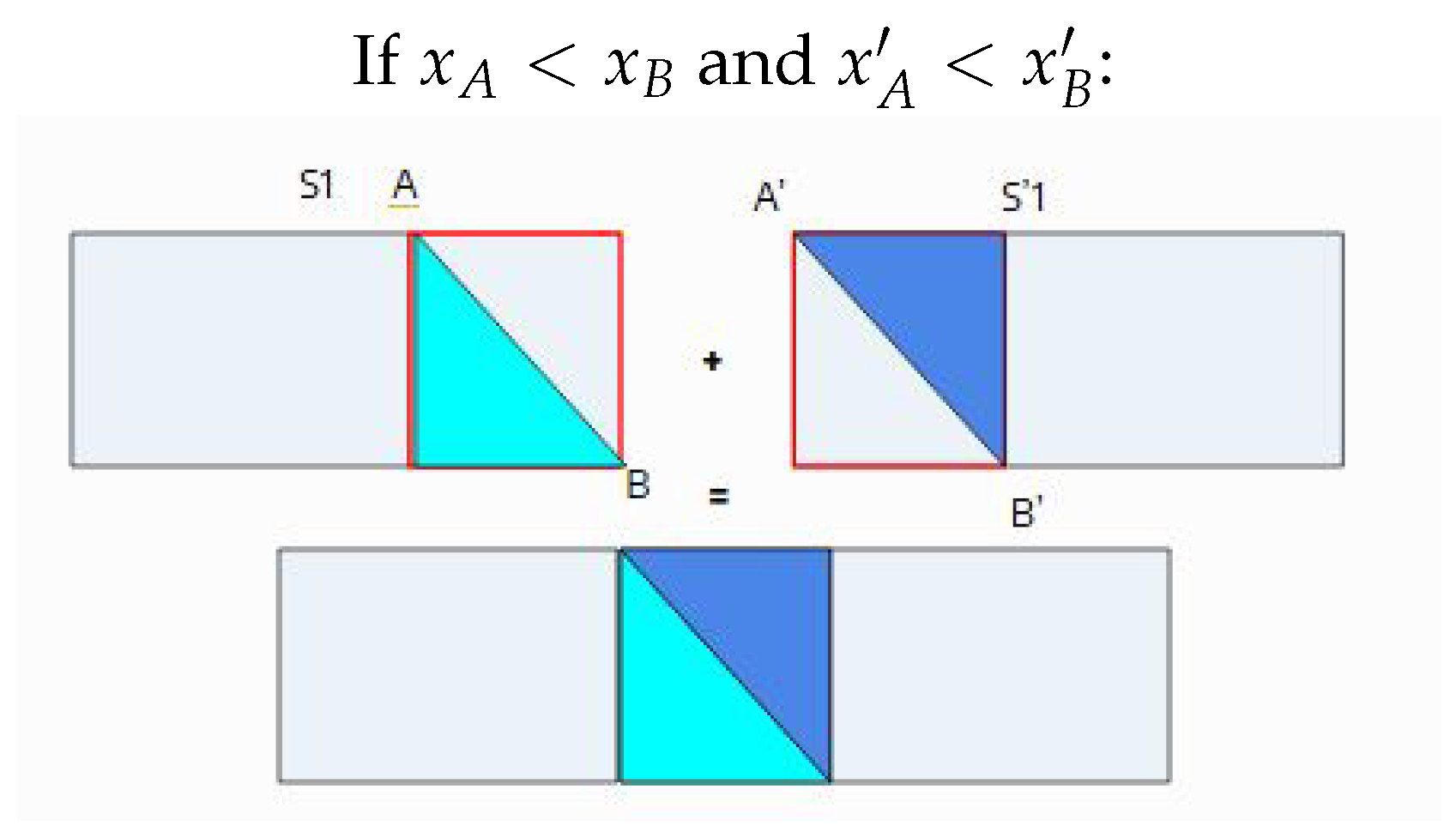

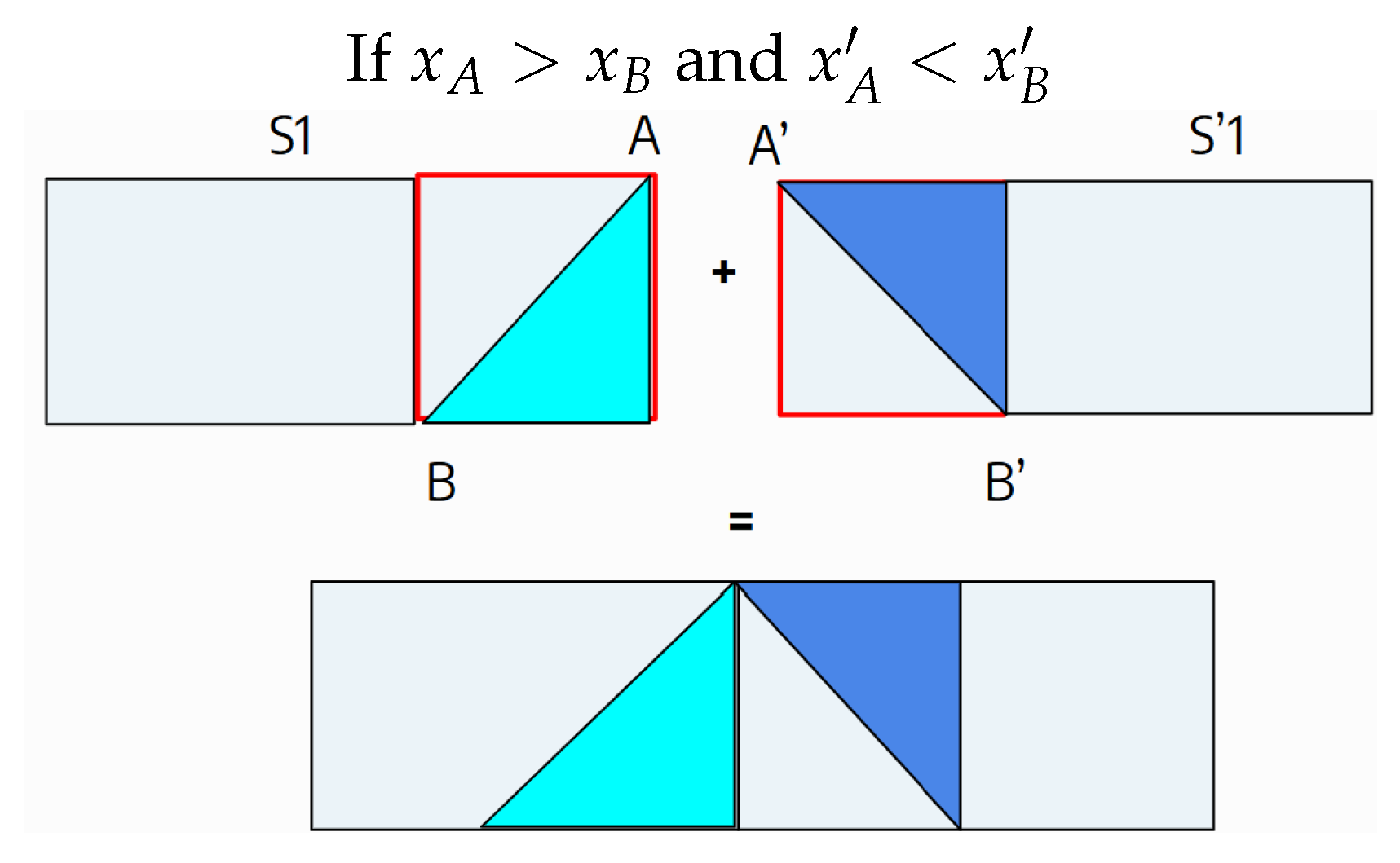

The image partitioning process begins with the optimal stitching line, which is defined by an ordered set of n reliable keypoint pairs (see

Figure 3. These points function as anchors for segmenting each image into

vertical slices.

To ensure the resulting vertical slices are structurally complementary (meaning they maintain consistent relative order and direction between the two images), a directional validation is performed on each consecutive pair of anchors and their corresponding pair () from the second image:

2.4.2. Reconstruction

After the segments have been validated, the process moves to the concatenation phase. Because both input images share the identical partitioning pattern, each segment of the first image corresponds directly to a segment of the second image. Corresponding segments are merged using a simple linear alpha transition: the contribution of the left segment decreases linearly from left to right, while the contribution of the right segment increases symmetrically. A final, light Gaussian smoothing is then applied across the seam area to suppress any residual visible artifacts. The resulting blended composites are concatenated horizontally, and the constructed rows are subsequently stacked vertically to form the final stitched image.

Figure 7 summarizes all the described processes.

3. Experimentation and Results

The experiments were conducted within a Google Colaboratory environment, leveraging 12.67GB of RAM and 107.72 GB of storage. We utilized publicly available and widely recognized datasets provided by [

4,

5,

19]. The code is available on

GitHub.

3.1. Quantitative Evaluation

Table 1 This section summarizes quantitative results for recent algorithms on the UDIS-D dataset (1,106 images grouped by difficulty: easy, moderate, and hard). Alignment accuracy in the overlap region between stitched images is evaluated using

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and the Structural

Similarity Index Measure (SSIM).

As shown in the

Table 1, our method achieves the highest PSNR and SSIM values among all compared approaches, indicating superior stitching quality. This confirms that our geometry-driven strategy consistently reflects better structural preservation and visual fidelity across diverse scenes.

3.2. Qualitative evaluation

We compare our approach against several state-of-the-art methods, including APAP [

9], ELA [

29], UDIS [

19], UDIS++ [

13] and SEAMLESS [

25]. Please feel free to zoom in on the images to better observe the highlighted elements. Additional data is given in the online resource and comprehensive visuals comparisons are provided on

Google Drive.

Figure 8.

APAP [

9], ELA [

29], and UDIS++ [

13] exhibit pronounced ghosting artifacts, while UDIS [

19] produces noticeable blurring and SEAMLESS [

25] introduces stretching in certain regions. Moreover, most of these approaches display a generally blurred texture across the stitched image. In contrast, our method eliminates duplication and preserves the original sharp texture of the input images.

Figure 8.

APAP [

9], ELA [

29], and UDIS++ [

13] exhibit pronounced ghosting artifacts, while UDIS [

19] produces noticeable blurring and SEAMLESS [

25] introduces stretching in certain regions. Moreover, most of these approaches display a generally blurred texture across the stitched image. In contrast, our method eliminates duplication and preserves the original sharp texture of the input images.

Figure 9.

We observe ghosting artifacts in APAP, ELA, UDIS, UDIS++ and a blurred texture in SEAMLESS. Our result is free of these artifacts.

Figure 9.

We observe ghosting artifacts in APAP, ELA, UDIS, UDIS++ and a blurred texture in SEAMLESS. Our result is free of these artifacts.

Figure 10.

Ghosting and blurring artifacts observed in state-of-the-art methods. Our approach produces seamless and visually consistent stitching results.

Figure 10.

Ghosting and blurring artifacts observed in state-of-the-art methods. Our approach produces seamless and visually consistent stitching results.

Figure 11.

Similar artifacts as in

Figure 9 for the state of the art.

Figure 11.

Similar artifacts as in

Figure 9 for the state of the art.

Figure 12.

Similar artifacts as in

Figure 9 for the state of the art.

Figure 12.

Similar artifacts as in

Figure 9 for the state of the art.

Figure 13.

Similar artifacts as in

Figure 9 for the state of the art.

Figure 13.

Similar artifacts as in

Figure 9 for the state of the art.

Figure 14.

Misalignments (tiles in the floor) in APAP, LPC, SPW, and correct alignment in SENA.

Figure 14.

Misalignments (tiles in the floor) in APAP, LPC, SPW, and correct alignment in SENA.

Figure 15.

UDIS++ [

13] and SEAMLESS [

25] present undistinguishable writings due to the blurred texture of the image, and misalignments. In SENA, the writings are clear as in the input images and a single slight misalignment is observed.

Figure 15.

UDIS++ [

13] and SEAMLESS [

25] present undistinguishable writings due to the blurred texture of the image, and misalignments. In SENA, the writings are clear as in the input images and a single slight misalignment is observed.

Qualitative results show that state-of-the-art methods often produce noticeable artifacts, including duplication, texture loss, and stretching of image structures. In contrast, SENA generates sharper, higher-resolution stitched images, while preserving structural integrity and visual realism.

3.3. Ablation Studies

We evaluate here the effectiveness of our three main components — the locally adaptive image warping, the adequate parallax-free zone identification, and the segment-based reconstruction — in improving alignment and removing artifacts.

Figure 16.

Without our warping strategy. This leads to alignment errors and geometric distortions.

Figure 16.

Without our warping strategy. This leads to alignment errors and geometric distortions.

Figure 17.

With our locally-adaptive image warping.

Figure 17.

With our locally-adaptive image warping.

Figure 18.

Without the identification of a parallax-free zone, the stitching might be performed in an unstable region, leading to visual artifacts in the result.

Figure 18.

Without the identification of a parallax-free zone, the stitching might be performed in an unstable region, leading to visual artifacts in the result.

Figure 19.

When identifying a parallax-free zone, the stitching is performed in a more stable region with consistent keypoints, resulting to an improved alignment.

Figure 19.

When identifying a parallax-free zone, the stitching is performed in a more stable region with consistent keypoints, resulting to an improved alignment.

Figure 20.

Without blending.

Figure 20.

Without blending.

Figure 21.

with our blending (linear alpha transition + light Gaussian smoothing).

Figure 21.

with our blending (linear alpha transition + light Gaussian smoothing).

3.4. Limitations

As demonstrated earlier, SENA effectively stitches images while preserving their natural appearance and geometric structure. However, certain limitations remain. The alignment between images is achieved through a multi-stage local deformation process: a global affine transformation estimated via RANSAC provides coarse alignment, which is then refined within the overlap region using locally adaptive affine models interpolated into a smooth Free-Form Deformation (FFD) field. This design allows accurate alignment while mitigating excessive distortion and maintaining shape and texture consistency. Nevertheless, in scenes with complex depth variations, the estimation of local models may become unstable, leading to locally inconsistent deformations or slight geometric discontinuities. Furthermore, the quality of the detected keypoints directly influences the identification of the adequate parallax-minimized zone and the subsequent stitching line extraction. When feature detection or matching is unreliable, artifacts such as minor ghosting, blurring, or local misalignment may still appear in the final panorama.

Figure 22.

Some failure cases

Figure 22.

Some failure cases

4. Conclusion

This work introduced SENA, a structure-preserving image stitching framework explicitly designed to address the geometric limitations of homography-based and over-flexible warping models. Rather than compensating for depth induced parallax through non-physical distortions, SENA adopts a hierarchical affine deformation strategy, combining global affine initialization, local affine refinement within the overlap region, and a smoothly regularized free-form deformation field. This multi-scale design preserves local shape, parallelism, and aspect ratios while providing sufficient flexibility to ensure accurate alignment. To further mitigate parallax-related artifacts, SENA incorporates a geometry-driven stitching mechanism that identifies a parallax minimized adequate zone directly from the consistency of RANSAC filtered correspondences, avoiding reliance on semantic segmentation or learning-based preprocessing. Based on this zone, an anchor-based segmentation strategy is applied, partitioning the overlapping images into corresponding vertical slices aligned by refined keypoints. This guarantees one-to-one geometric correspondence across segments and enforces structural continuity across the stitching boundary, effectively reducing ghosting, duplication, and texture stretching.

Extensive experiments demonstrate that SENA consistently achieves visually coherent panoramas with improved structural fidelity and reduced distortion compared to representative homography-based and spline-based methods. While the method remains robust across a wide range of scenes, performance may degrade under extreme viewpoint changes or in severely texture-deprived environments, where feature extraction becomes unreliable. Future work will explore adaptive local deformation models and hybrid learning-based components to further enhance robustness under such challenging conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.N.T and D.B.M.F; methodology, G.L.N.T and D.B.M.F; software, G.L.N.T and D.B.M.F; validation, G.L.N.T, D.B.M.F, A.H and C.B; formal analysis, G.L.N.T, D.B.M.F and A.H; investigation, G.L.N.T and D.B.M.F.; resources, C.B; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.N.T and D.B.M.F; writing—review and editing, G.L.N.T, D.B.M.F, A.H and C.B.; visualization, G.L.N.T, A.H; supervision, C.B.; project administration, C.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: a paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Communications of the ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Yang, W. Object-level geometric structure preserving for natural image stitching. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2025; Vol. 39, pp. 1926–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Yang, W. Object-level geometric structure preserving for natural image stitching. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Philadelphia, PA,USA, 2025; AAAI; Vol. 39, pp. 1926–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Du, P.; Ning, J.; Cui, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Geometric structure preserving warp for natural image stitching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2022; pp. 3688–3696. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, C.; Wang, C.; Bowen, R.S.; Keyder, E.; Zabih, R. Object-centered image stitching. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 821–835. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. SURF: Speeded up robust features. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2006; Springer: Graz, Austria, 2006; pp. 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International Journal of Computer Vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, L.; Gwun, O. A comparison of SIFT, PCA-SIFT and SURF. International Journal of Image Processing 2009, 3, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza, J.; Chin, T.-J.; Brown, M.S.; Suter, D. As-projective-as-possible image stitching with moving DLT. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Portland, OR, USA, 2013; pp. 2339–2346. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Kim, S.J.; Brown, M.S. Constructing image panoramas using dual-homography warping. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2011; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.; Choudhary, P.; Goel, S.; Parameswaran, S.; Bajpai, P.; Kim, J. Selfie Stitch: Dual homography based image stitching for wide-angle selfie. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW), San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Q.; Li, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhao, H.; Teng, S.; Ye, X.; Latecki, L.J. Leveraging line-point consistence to preserve structures for wide parallax image stitching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021; pp. 12186–12195. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, L.; Lin, C.; Liao, K.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y. Parallax-tolerant unsupervised deep image stitching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2023; pp. 7399–7408. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, F. Parallax-tolerant image stitching. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2014; pp. 3262–3269. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Chen, F.; Cheng, H.; Li, L.; Wang, M. Semantic segmentation guided feature point classification and seam fusion for image stitching. Journal of Algorithms & Computational Technology 2021, 15, 17483026211065399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, L.; He, X. Combined regional homography-affine warp for image stitching. Proceedings of the International Conference on Graphics and Image Processing (ICGIP) 2022, Vol. 12705, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, T.; Li, N. Single-perspective warps in natural image stitching. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2019, 29, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Huang, M.; Yu, B. Structure preservation and seam optimization for parallax-tolerant image stitching. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 78713–78725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Lin, C.; Liao, K.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y. Unsupervised deep image stitching: Reconstructing stitched features to images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 6184–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikka, P.; Asati, A.R.; Shekhar, C. Real time FPGA implementation of a high speed and area optimized Harris corner detection algorithm. Microprocessors and Microsystems 2021, 80, 103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Yang, H.; Han, C. Research on image stitching method based on improved ORB and stitching line calculation. Journal of Electronic Imaging 2022, 31, 051404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Sun, B. Utilization of merge-sorting method to improve stitching efficiency in multi-scene image stitching. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potje, G.; Cadar, F.; Araujo, A.; Martins, R.; Nascimento, E.R. XFeat: Accelerated features for lightweight image matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2024; pp. 2682–2691. [Google Scholar]

- Nghonda, E. Enable 360-Degree Immersion for Outside-In Camera Systems for Live Events. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Garg, A.; Wang, Y.-S. Seamless-through-breaking: Rethinking image stitching for optimal alignment. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision (ACCV), 2024; pp. 4352–4367. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, P.; Jiang, F. Image stitching by feature positioning and seam elimination. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 20869–20881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Chen, J.; Mao, Z.; Zhu, Q. An upscaling–downscaling optimal seamline detection algorithm for very large remote sensing image mosaicking. Remote Sensing 2022, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Dung, L.-R. Stitching strip determination for optimal seamline search. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Imaging, Signal Processing and Communications (ICISPC), 2020; pp. 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Lai, S.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, M. Parallax-tolerant image stitching based on robust elastic warping. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2017, 20, 1672–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Hu, H.-M. A novel projective-consistent plane based image stitching method. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2019, 21, 2561–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lai, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M. Local facet approximation for image stitching. Journal of Electronic Imaging 2018, 27, 013011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Jia, L.; Ye, N.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Sun, J. Content-aware unsupervised deep homography estimation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020; Springer: Glasgow, UK, 2020; pp. 653–669. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, L.; Lin, C.; Liao, K.; Zhao, Y. Learning edge-preserved image stitching from large-baseline deep homography. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.06194. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, L.; Lin, C.; Liao, K.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y. A view-free image stitching network based on global homography. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2020, 73, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).