Introduction

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) encompasses a group of autosomal recessive disorders characterized by impaired adrenal steroidogenesis. Over five types of enzyme deficiency have been identified in CAH, of which the most prevalent form, accounting for over 90% of all cases, is 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21-OHD), which results from pathogenic variants in the

CYP21A2 gene [

1]. The 21-hydroxylase enzyme (CYP21A2), a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase located in the endoplasmic reticulum of the adrenal cortex, is a key component of the steroidogenic pathway. The CYP21A2 catalyzes the conversion of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) to 11-deoxycortisol and progesterone to 11-deoxycorticosterone, the immediate precursors for cortisol and aldosterone [

2]. A deficiency in 21-hydroxylase activity disrupts these pathways, leading to a cascade of pathophysiological consequences [

3,

4,

5]. The resulting impairment in cortisol synthesis disrupts the negative feedback loop of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, causing a compensatory surge in adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion. Chronic overstimulation by ACTH leads to the characteristic hyperplasia of the adrenal glands and, critically, shunts the accumulating steroid precursors away from glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid synthesis and toward the androgen production pathway [

6,

7].

The clinical presentation of 21-OHD exists on a continuous spectrum, traditionally classified into three phenotypes that directly correlate with the degree of residual enzyme function. The most severe, classic forms present in the neonatal period. The salt-wasting (SW) form, resulting from a complete or near-complete loss of enzyme activity, is characterized by life-threatening adrenal crises due to cortisol and aldosterone deficiency, accompanied by severe virilization in female newborns. The simple virilizing (SV) form, associated with 1-5% residual enzyme activity, has sufficient aldosterone production to prevent salt-wasting crises, but the significant androgen excess still causes ambiguous genitalia in females and precocious puberty in both sexes. The non-classic (NC) form is the mildest, with 20-50% residual enzyme activity, and typically presents later in childhood or adulthood with symptoms of hyperandrogenism, such as premature pubarche, hirsutism, and infertility [

8,

9]. The severe form is associated with significant neonatal mortality, and endocrinological and metabolic evaluation as well as appropriate treatment should be initiated immediately [

5,

10,

11].

The first-tier diagnostic screening is radioimmunoassay in newborn screening, testing for the serum levels of 17-OHP that is the precursor of cortisol and the substrate for 21-hydroxylase [

12]. However, 17-OHP levels can be influenced by several factors, including enzyme deficiencies in the steroidogenic pathway, gestational age, birth environment, multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids, and the gender [

13,

14]. This negative predictive value can be improved by incorporating secondary biochemical and molecular screening methods. Biochemical screening includes analysis of 21-deoxycortisol in blood and urine samples using LC-MS, as well as measurement of steroid ratios [

15]. Molecular genetic screening involves the detection of

CYP21A2 mutations in DNA extracted from the same blood used in the newborn screening [

16,

17].

The genetic basis of 21-OHD is uniquely complex. The

CYP21A2 gene is located within the highly variable HLA class III region on chromosome 6p21.3, in close proximity to a non-functional pseudogene,

CYP21A1P, with which it shares 98% sequence homology in exons [

18]. This high degree of identity predisposes the locus to frequent intergenic recombination events, primarily gene conversions, which transfer deleterious sequences from the pseudogene to the functional gene. These events account for approximately 75% of all pathogenic

CYP21A2 alleles, making molecular diagnosis a significant technical challenge [

19,

20].

Current research has demonstrated a strong genotype-phenotype correlation, with

CYP21A2 mutations classified into four groups that help predict clinical presentation [

14,

15,

21]. In mutation group 0 (null), enzymatic activity is completely abolished due to large gene conversions, frameshifts, nonsense mutations, deletions and certain missense mutations. These are typically associated with SW classic alleles [

22]. In group A, both the SW and SV phenotypes may occur, usually resulting from a low level of normally spliced mRNA produced by c.293-13A/G variant in the intron 2 region. This mutation is particularly common, found in approximately 25% of mutant alleles [

23]. In group B, mutations retain <5% of normal enzymatic activity and commonly linked to the SV form [

24]. In group C, missense mutations reduce enzyme activity to about 50% of normal and are associated with the NC form of CAH [

25].

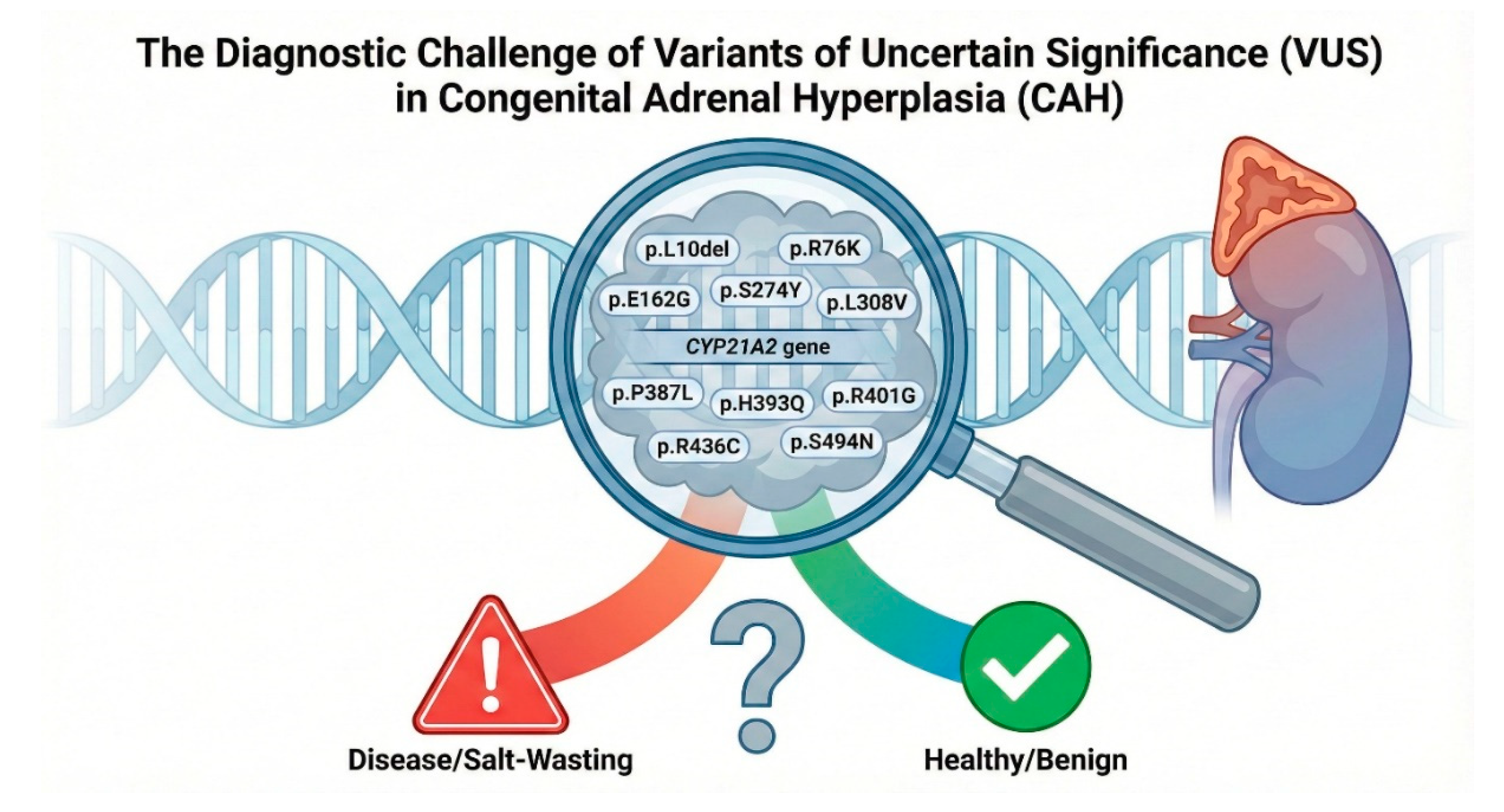

While a strong genotype-phenotype correlation has been established for common mutations, the increasing application of next-generation sequencing in clinical practice has led to the identification of a growing number of rare variants. A significant portion of these remain classified as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in clinical databases such as ClinVar, or have conflicting reports regarding their pathogenicity.[

26] This diagnostic ambiguity presents a major obstacle for accurate molecular diagnosis, prediction of clinical severity, and effective genetic counseling for families affected by CAH. This study was conceived to address the critical knowledge gap for eleven such variants, p.L10del, p.R76K, p.E162G, p.L308V, p.S373N, p.R401G, p.R436C, p.S274Y, p.P387L, p.H393Q and p.S494N, for which functional data are absent, incomplete, or contradictory. Our multi-pronged approach, integrating evolutionary conservation, structural modeling, protein stability predictions, and direct in vitro functional assays, would elucidate the molecular consequences of these variants. Moreover, this comprehensive body of evidence would enable their reclassification according to the rigorous American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)/Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines, thereby resolving diagnostic uncertainty and improving the genotype-phenotype correlation in 21-hydroxylase deficiency.

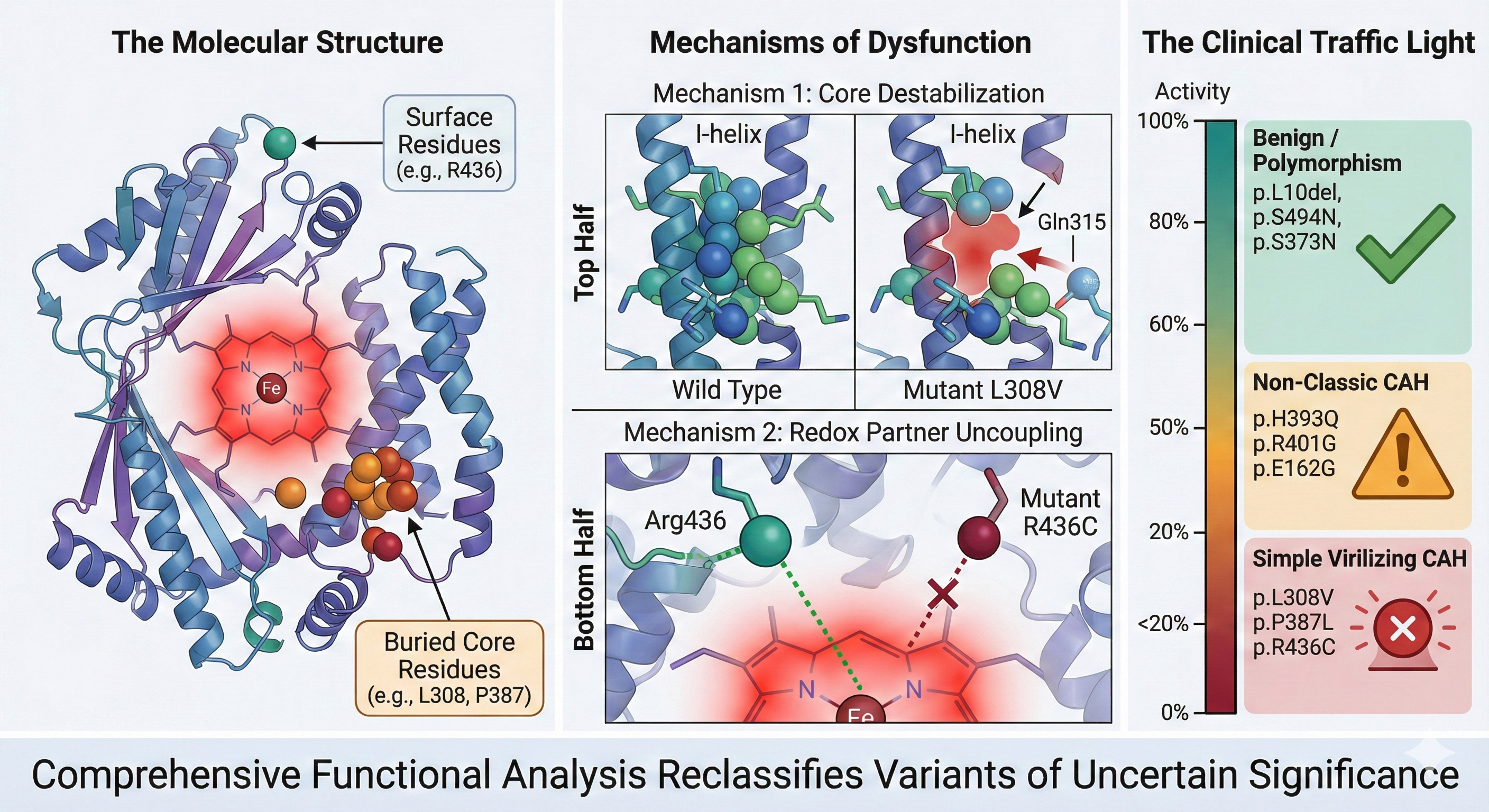

Figure 1.

The clinical conundrum of CYP21A2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS). A schematic illustration of the CYP21A2 gene locus on chromosome 6p21.3, highlighting the eleven missense variants analyzed in this study, p.L10del, p.R76K, p.E162G, p.S274Y, p.L308V, p.S373N, p.P387L, p.H393Q, p.R401G, p.R436C, and p.S494N. We have investigated the diagnostic ambiguity facing clinicians: identifying which of these variants are benign polymorphisms (green) and which are pathogenic mutations capable of causing Salt-Wasting or Simple Virilizing CAH (red).

Figure 1.

The clinical conundrum of CYP21A2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS). A schematic illustration of the CYP21A2 gene locus on chromosome 6p21.3, highlighting the eleven missense variants analyzed in this study, p.L10del, p.R76K, p.E162G, p.S274Y, p.L308V, p.S373N, p.P387L, p.H393Q, p.R401G, p.R436C, and p.S494N. We have investigated the diagnostic ambiguity facing clinicians: identifying which of these variants are benign polymorphisms (green) and which are pathogenic mutations capable of causing Salt-Wasting or Simple Virilizing CAH (red).

Results

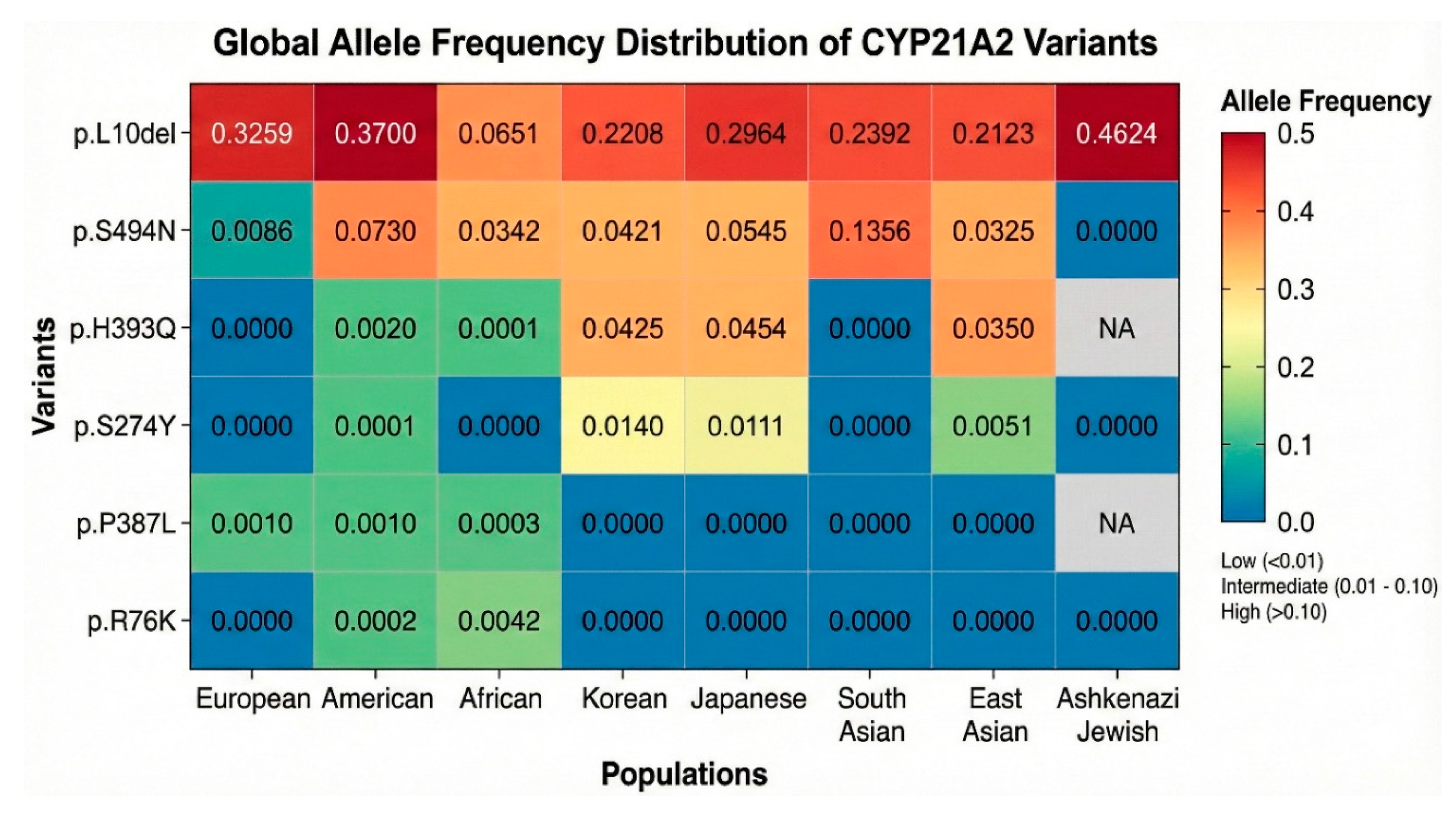

Population Genetics and Allele Frequency Analysis

The first tier of evidence in establishing the pathogenicity of a genetic variant is its frequency within the general population. The prevalence of an allele can serve as a potent filter for pathogenicity; variants causing severe, early-onset recessive disorders like classic CAH are subject to strong negative selection and are therefore expected to be extremely rare. Conversely, alleles present at frequencies significantly higher than the disease carrier frequency are likely benign polymorphisms or associated with very mild, non-classic phenotypes. We analyzed the allele frequencies of the selected CYP21A2 variants across multiple large-scale genomic databases, including gnomAD, ExAC, TOPMed, ALFA, and the 1000 Genomes Project (1000G), as summarized in the Supplementary Table S1.

High-Frequency Variants Indicating Benign Polymorphisms

Analysis of the variant p.L10del (c.17_19delTGC) revealed frequencies that are fundamentally inconsistent with a pathogenic role in a rare Mendelian disorder. In the 38KJPN (Japanese) database, the allele frequency was observed at 0.29641, and in the ALFA database, it was 0.22776. Furthermore, specific subpopulations showed even higher prevalences, such as 0.338 in Northern Sweden and 0.4624 in Ashkenazi Jewish populations (

Figure 2). The presence of this variant in nearly a third to half of the alleles in certain populations suggests it is a common polymorphism (rs61338903) likely devoid of significant deleterious effects on protein function. Similarly, the p.S494N (c.1481G>A) variant was identified at high frequencies in East Asian populations, with an allele frequency of 0.0545 in Japanese (38KJPN) and 0.0421 in Korean cohorts. The minor allele frequency (MAF) in the global ALFA dataset was 0.0068, which, while lower than p.L10del, is still well above the expected frequency for a severe pathogenic allele.

The variant p.R76K (c.227G>A) also exhibited frequencies suggestive of a benign nature. In the ALFA database, it was reported at a remarkably high frequency of 0.51, although other databases like gnomAD exomes reported a more modest 1.13 x 10-4. The high frequency in ALFA (rs368330593) likely reflects specific population structures or technical artifacts in certain datasets, but the overall presence in 1000G at 1.6 x 10-3 supports its classification as a common variant rather than a disease-causing mutation.

Rare Variants Aligning with Pathogenic Potential

In sharp contrast to the variants described above, the remaining eight variants, p.E162G, p.S274Y, p.L308V, p.S373N, p.P387L, p.H393Q, p.R401G, and p.R436C, were characterized by extreme rarity or complete absence in general population databases, a hallmark of alleles under purifying selection. The p.L308V (c.922T>G) variant was detected at an ultra-low frequency of 5 x 10-8 in gnomAD exomes and 1.9 x 10-5 in TOPMed. This scarcity is consistent with a potentially deleterious allele that is efficiently removed from the gene pool or maintained only in heterozygosity. Similarly, p.P387L (c.1160C>T) was found at 2 x 10-4 in ExAC and 3 x 10-4 in 1000G, frequencies that align with carrier rates for rare recessive traits. The p.R436C (c.1306C>T) variant appeared at 5.3 x 10-4 in ALFA and 1.11 x 10-3 in ExAC, again falling within the range of potential pathogenicity. Of particular interest is p.H393Q (c.1179C>G). While rare in European-dominated datasets like ExAC (3.12 x 10-3), it showed a notable enrichment in Asian populations, with a frequency of 0.0455 in the 38KJPN database and 0.043 in the Korean database. This discrepancy suggests a population-specific allele, potentially a founder mutation associated with a milder, non-classic phenotype that has escaped strong negative selection in these groups.

A “Variant Frequency Heatmap” (

Figure 2) was created to visually summarize the findings from the survey of genomic sequence databases (color version in Supplementary Materials). The heatmap displayed a striking dichotomy; the columns for p.L10del are dominated by “hot” colors (red/orange) across almost all populations, visually confirming its status as a ubiquitous polymorphism. The p.S494N row shows “warm” colors specifically in the East Asian and South Asian columns, highlighting its ethnic specificity. Conversely, the rows for p.R76K, p.S274Y, p.P387L, and p.H393Q are predominantly “cool” (blue/green) across European, American, and African populations, indicating near-zero frequencies. This population stratification provided the foundational evidence that p.L10del and p.S494N are likely benign, while the rare variants warranted deeper functional scrutiny to determine their clinical significance.

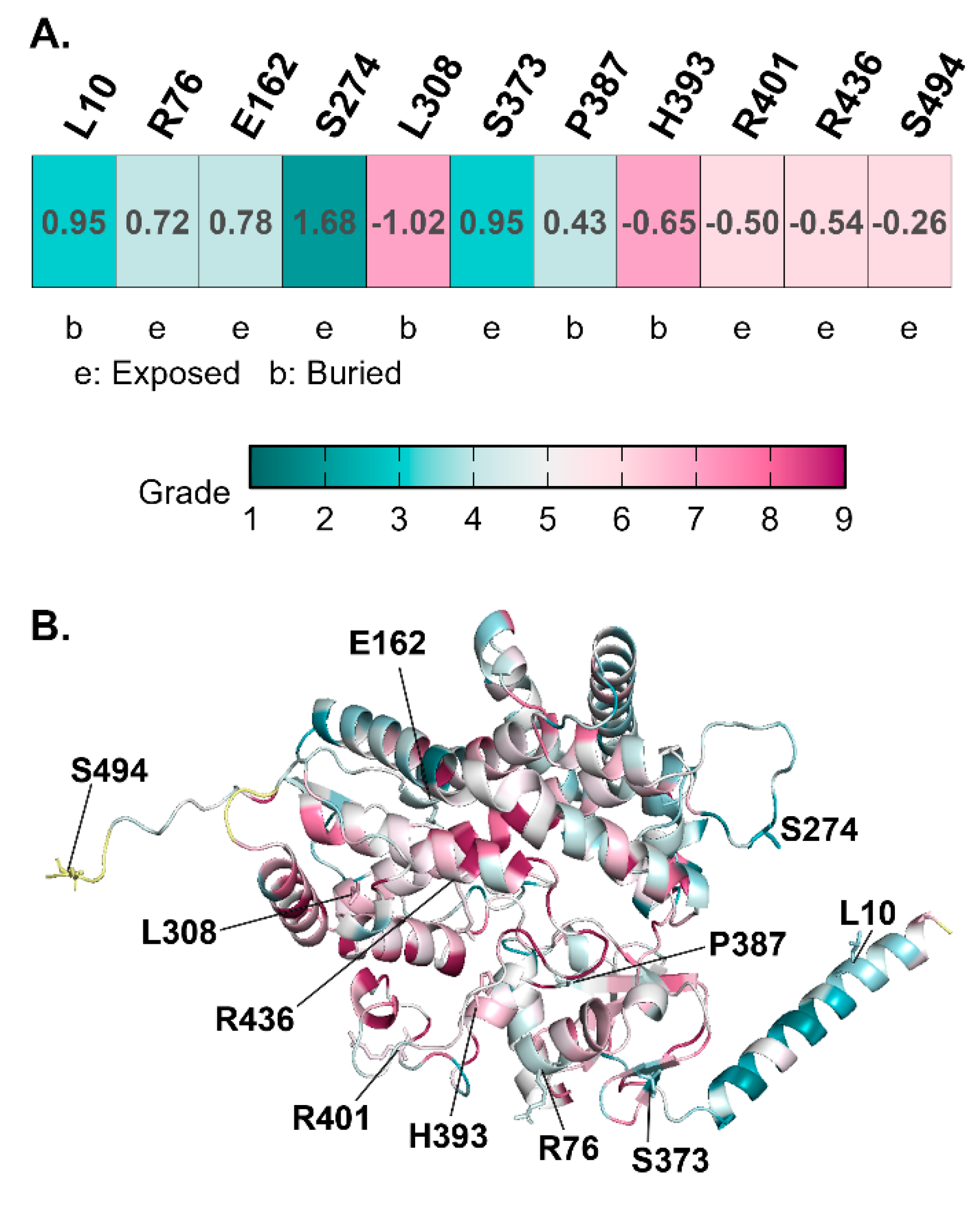

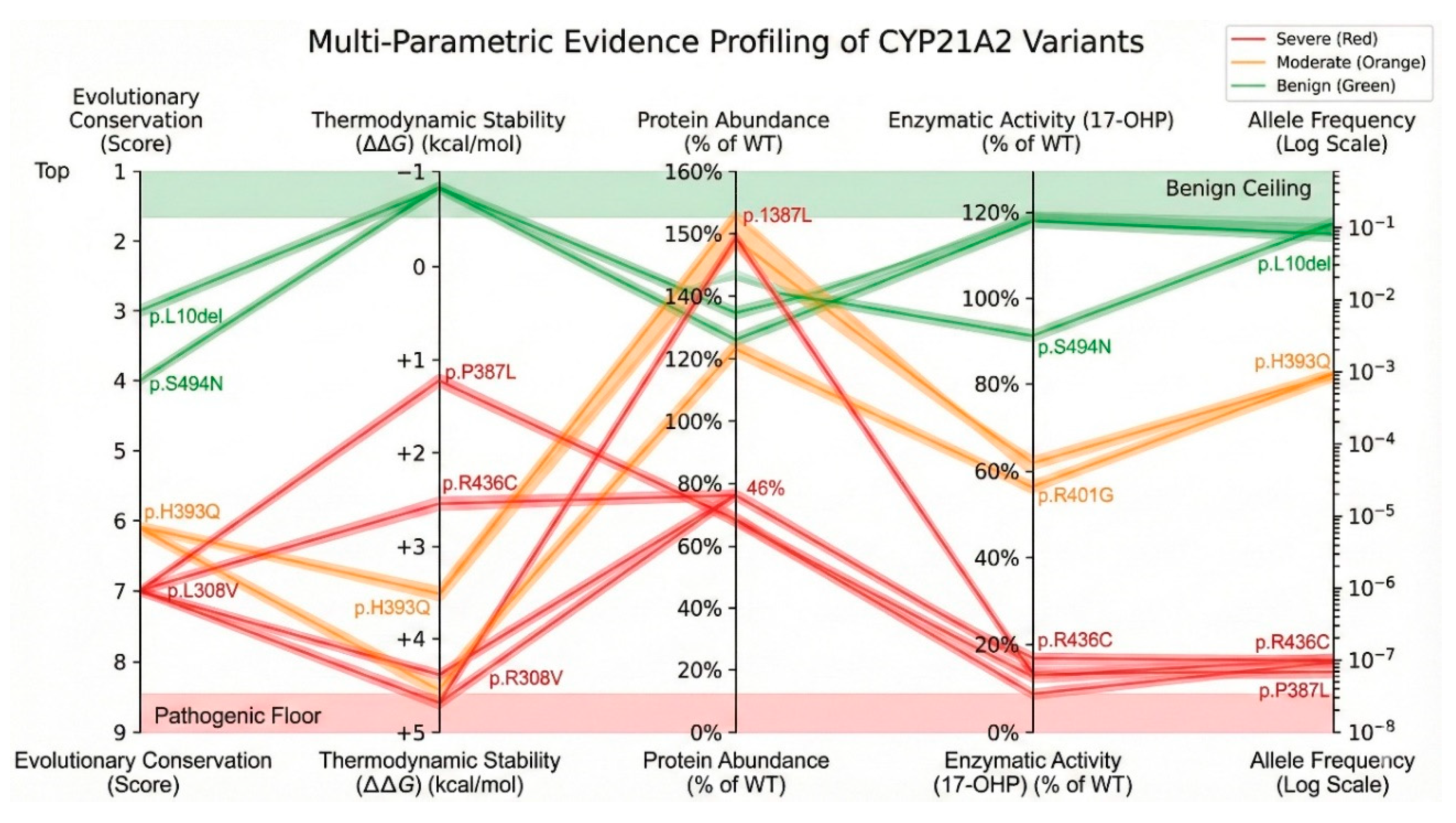

Evolutionary Conservation Analysis (ConSurf)

To understand the functional constraints acting on the CYP21A2 gene, we performed an evolutionary conservation analysis using ConSurf. This method assigns a conservation score to each amino acid position based on the phylogenetic alignment of homologous sequences from diverse species. Residues that are critical for protein folding, stability, or catalysis are typically highly conserved (score 9), while those in flexible loops or non-functional regions tolerate variability (score 1).

The analysis of the eleven variant residues revealed a clear segregation based on their conservation status, as detailed in the Supplementary Table S2. The highly conserved residues included Leu308, located in the I-helix of the cytochrome P450 structure, received a conservation score of 7. The confidence interval for this score was tight (8,7), indicating high certainty. In the multiple sequence alignment (MSA), Leu308 was present in 100/100 sequences, with only a rare Valine substitution observed in 3% of sequences. This strict conservation underscores the structural indispensability of Leu308, which resides in the core of the enzyme and likely plays a role in defining the architecture of the active site. Similarly, Pro387 in the K-L loop scored a 4, with 100/100 sequences retaining this residue. Prolines are unique in their ability to restrict backbone flexibility, often acting as “structural staples.” The absolute conservation of Pro387 suggests that the rigidity it imparts to the K-L loop is critical for the proper folding of the heme-binding pocket. Located on the surface of the L-helix, Arg436 scored a 6. While surface residues are often variable, Arg436 is part of the binding interface for P450 Oxidoreductase (POR). Its positive charge is essential for the electrostatic docking with the electron donor protein. The ConSurf analysis confirms that this interaction interface is evolutionarily constrained. His393, a buried residue scored a 7, with high conservation (100/100 sequences in MSA). Its buried nature suggests a role in packing or stabilizing the core through hydrogen bonding or van der Waals interactions.

Figure 3.

Evolutionary Conservation Mapping on the CYP21A2Structure. (A) ConSurf analysis table showing conservation scores for variant residues (Scale 1-9). Highly conserved residues are critical for function/stability. (B) Three-dimensional structural mapping of conservation scores onto the CYP21A2 structure. The protein backbone is colored by conservation grade: magenta indicates highly conserved core regions, while cyan indicates variable surface loops. Pathogenic variants p.L308V and p.P387L map to the highly conserved magenta core, suggesting intolerance to mutation. In contrast, benign variants p.L10del and p.S494N map to variable cyan regions on the protein periphery. The heme cofactor is shown as sticks.

Figure 3.

Evolutionary Conservation Mapping on the CYP21A2Structure. (A) ConSurf analysis table showing conservation scores for variant residues (Scale 1-9). Highly conserved residues are critical for function/stability. (B) Three-dimensional structural mapping of conservation scores onto the CYP21A2 structure. The protein backbone is colored by conservation grade: magenta indicates highly conserved core regions, while cyan indicates variable surface loops. Pathogenic variants p.L308V and p.P387L map to the highly conserved magenta core, suggesting intolerance to mutation. In contrast, benign variants p.L10del and p.S494N map to variable cyan regions on the protein periphery. The heme cofactor is shown as sticks.

Among the variable residues (Score 1-5), situated in the N-terminal membrane anchor, Leu10 showed high variability (Score 3). The MSA data revealed a variety of residues at this position, consistent with the structural role of this region as a simple tether to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane rather than a precise catalytic element. This low conservation supports the population data suggesting p.L10del is benign. The Ser494, located in the disordered C-terminal tail, Ser494 scored a 6. The presence of this residue in only 2/100 sequences in the alignment highlights the lack of evolutionary pressure on the extreme C-terminus. The Arg76 (Score 4) located on surface, also showed variability, aligning with the high allele frequency of the p.R76K variant.

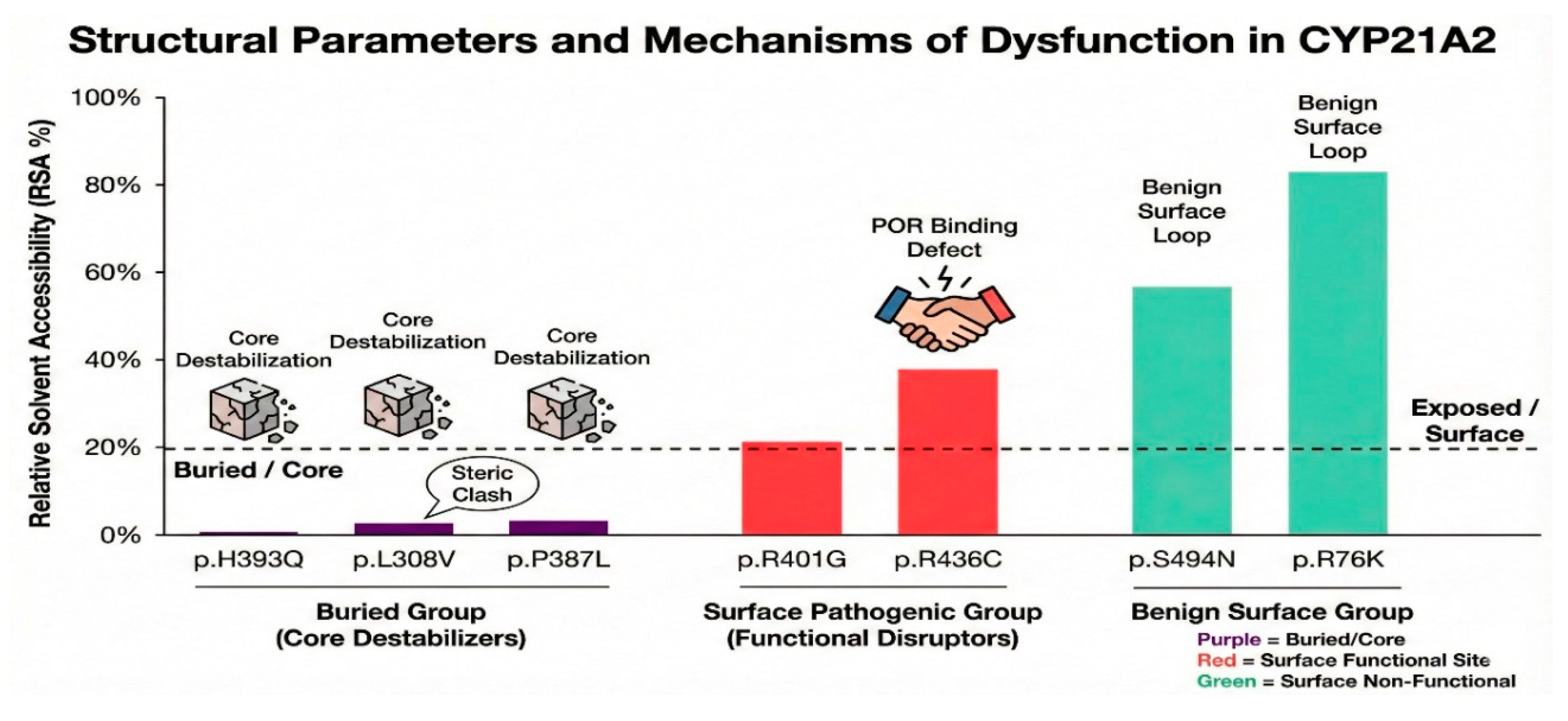

Structural Parameters: Solvent Accessibility and Physicochemical Properties

To further delineate the structural environment of the variants, we calculated the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) and Relative Solvent Accessibility (RSA) for both the wild-type (WT) and mutant residues. These metrics help distinguish between “buried” residues, which contribute to protein core stability, and “exposed” residues, which interact with the solvent or partner proteins (Supplementary Table S3). The physiochemical property analysis reveals distinct structural classes for the variants. Among the buried residues (critical for stability), the His393 residue is almost completely buried, with a Total SASA of only 0.80 Ų and an RSA of 0.35%. The side chain contributes 100% of this minuscule accessible area. The mutation to Glutamine (Q) results in a negligible change in surface area (ΔRSA = 0.02) but introduces a polar residue into a hydrophobic environment. The buried nature explains why this site is so sensitive to mutation; there is no room for structural accommodation. The Pro387 is also deeply buried (Total SASA 4.30 Ų, RSA 2.71%). The mutation to Leucine slightly decreases the SASA (to 3.90 Ų). Being buried in the β-sheet region near the heme, the replacement of the compact Proline with the bulkier Leucine likely introduces steric strain in the core. Leu308 has a Total SASA of 5.08 Ų and an RSA of 2.53%, confirming it is a buried residue. The substitution to Valine increases the SASA slightly to 7.28 Ų (ΔRSA = 1.47). As a core residue in the I-helix, its burial is essential for maintaining the hydrophobic integrity of the active site roof.

Among the surface exposed residues (interaction Sites), the R436 is highly exposed, with a Total SASA of 87.79 Ų and an RSA of 32.04%. The mutation to cysteine significantly reduces the surface area (Total SASA drops to 37.01 Ų), leading to a massive negative change in relative solvent accessibility (ΔRSA = -9.88). This drastic reduction in surface presence, combined with the loss of the arginine’s charge, directly impairs the protein’s ability to interact with the solvent and its redox partner, POR. The R76 residue is also highly exposed (Total SASA 189.19 Ų, RSA 69.05%). The mutation to lysine maintains the basic charge and results in a minor change in RSA (ΔRSA = -1.66). The high exposure and conservation of physicochemical properties (Arg to Lys) explain why this variant is benign. The E162 is moderately exposed (Total SASA 42.81 Ų, RSA 19.20%) and its mutation to Glycine reduces the SASA to 30.74 Ų. The structural parameter analysis reinforces the distinction between core-destabilizing mutations (H393Q, P387L, L308V) and surface-altering mutations (R436C). The extremely low SASA values for the former group indicate that any mutation at these sites must disrupt the dense protein packing, inevitably leading to stability issues.

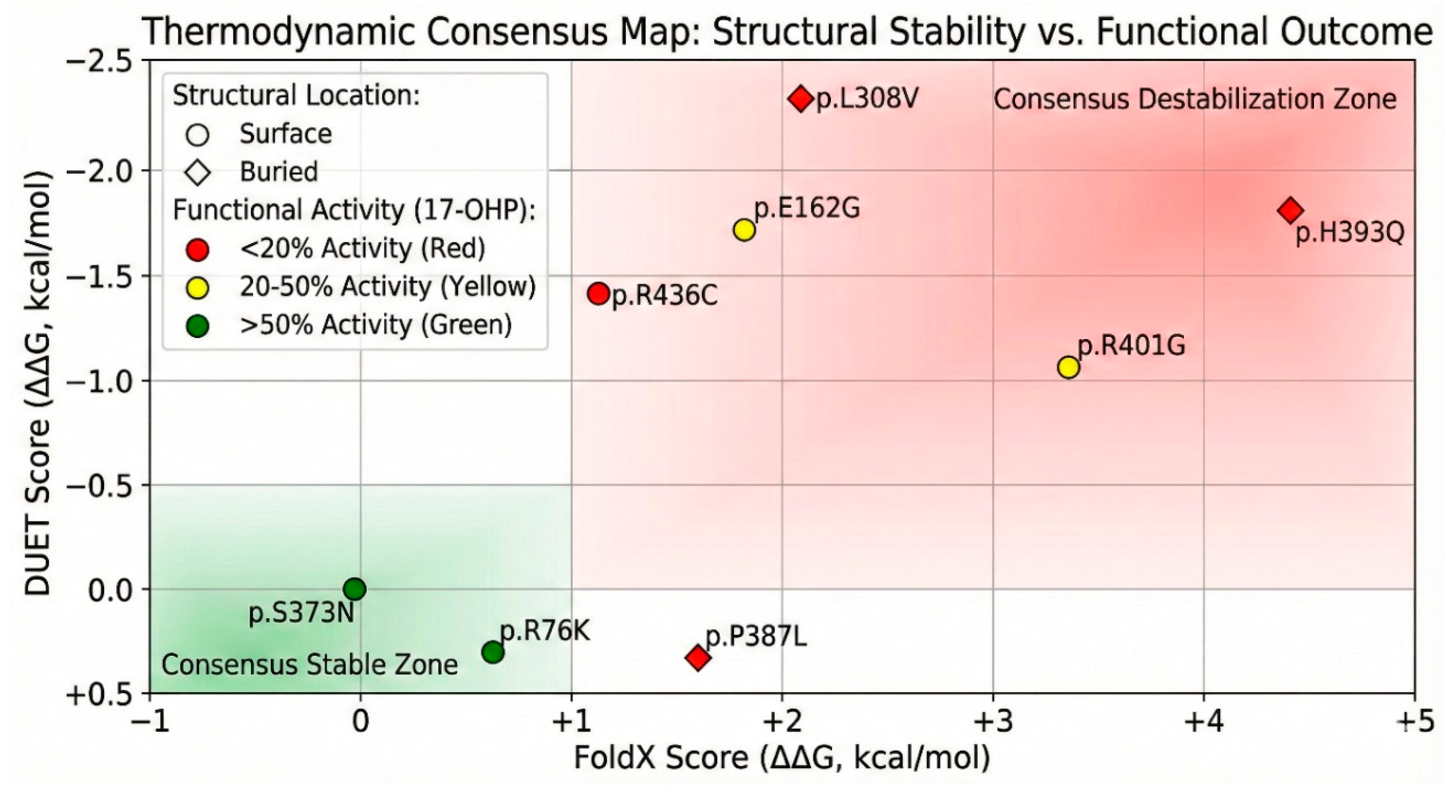

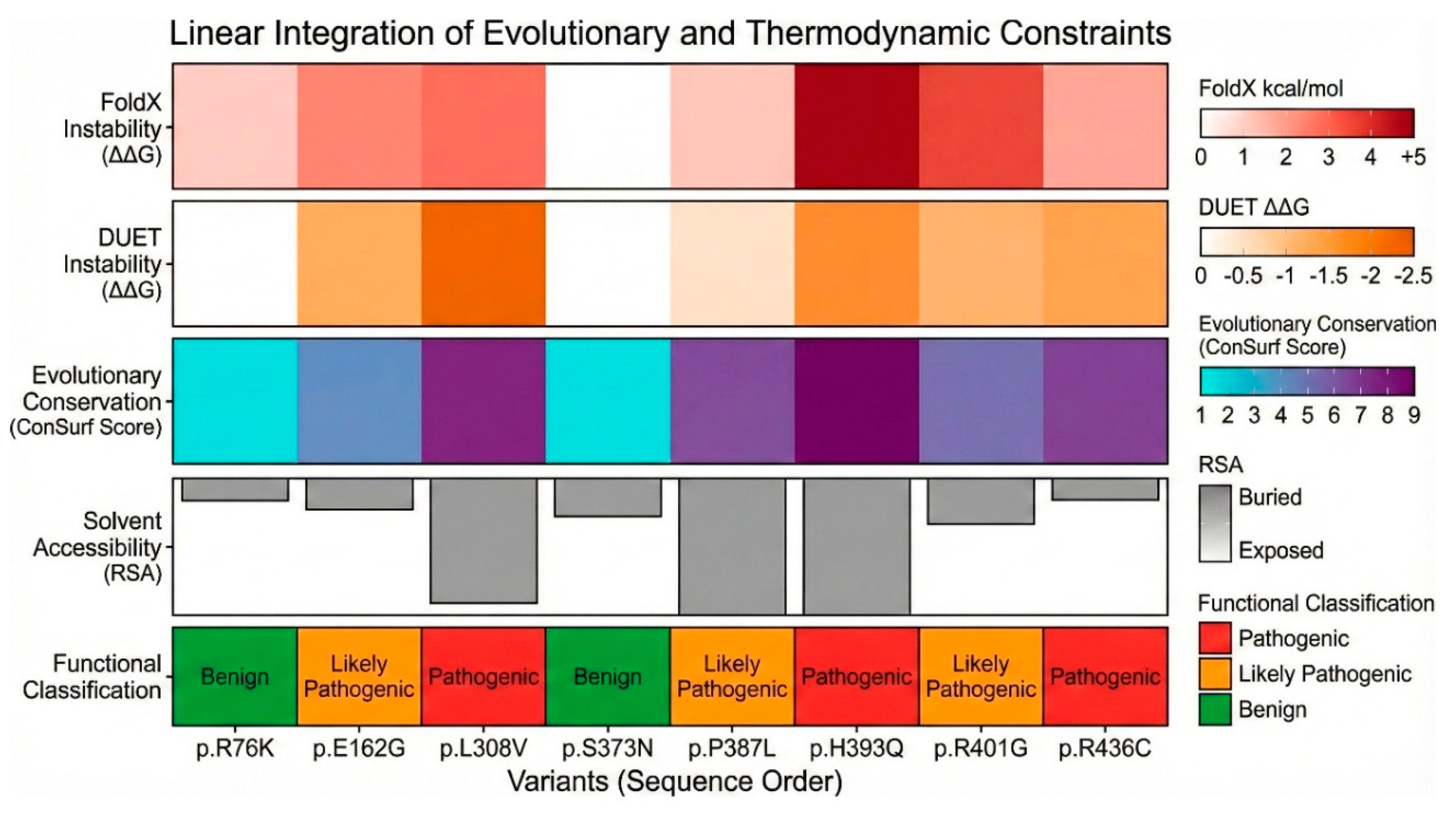

Thermodynamic Stability Predictions: FoldX and DUET

We utilized computational algorithms, FoldX and DUET, to predict the change in Gibbs free energy of folding (ΔΔG) upon mutation. These tools provide a quantitative estimate of how much a mutation destabilizes the protein structure compared to the wild type (Supplementary Table S4: FoldX and DUET ΔΔG predictions). The stability prediction data provided a thermodynamic stratification of the variants. Among the severely destabilizing mutations (ΔΔG > 3 kcal/mol), p.H393Q variant exhibited the highest destabilization score in FoldX, with a ΔΔG of 4.47 ± 0.02 kcal/mol. In the DUET analysis, it showed a score of -1.69 kcal/mol (where negative indicates destabilization). Such a high positive FoldX score predicts a catastrophic loss of stability, likely preventing the protein from folding correctly or targeting it for rapid degradation. This aligns perfectly with its “buried” status; the introduction of glutamine breaks the hydrophobic core. The p.R401G variant also showed severe destabilization, with a FoldX score of 3.42 ± 0.02 kcal/mol. Despite being a surface residue, Arg401 likely participates in critical salt bridges that stabilize the tertiary fold. The loss of this interaction energy significantly compromises the protein structure.

Figure 4.

Predicted Thermodynamic Stability Changes (ΔΔG$). A comparative bar graph of Gibbs free energy changes (ΔΔG) predicted by FoldX and DUET algorithms. (X axis) FoldX: Positive ΔΔG values indicate destabilization. p.H393Q and p.R401G show severe destabilization scores (>3 kcal/mol), predicting a likely disruption of the protein fold. (Y axis) DUET: Negative ΔΔG values indicate destabilization. Consistent with FoldX, p.L308V and p.E162G are predicted to be destabilizing. The benign variants p.S373N and p.R76K exhibit near-neutral scores across both tools, indicating structural tolerability. Data are in Supplementary Table S4. (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials).

Figure 4.

Predicted Thermodynamic Stability Changes (ΔΔG$). A comparative bar graph of Gibbs free energy changes (ΔΔG) predicted by FoldX and DUET algorithms. (X axis) FoldX: Positive ΔΔG values indicate destabilization. p.H393Q and p.R401G show severe destabilization scores (>3 kcal/mol), predicting a likely disruption of the protein fold. (Y axis) DUET: Negative ΔΔG values indicate destabilization. Consistent with FoldX, p.L308V and p.E162G are predicted to be destabilizing. The benign variants p.S373N and p.R76K exhibit near-neutral scores across both tools, indicating structural tolerability. Data are in Supplementary Table S4. (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials).

Among the moderately destabilizing mutations (ΔΔG < 3 kcal/mol), the p.L308V was predicted to have a destabilization of 2.10 ± 0.07 kcal/mol for FoldX, while DUET predicted -2.15 kcal/mol. This consistent prediction of instability suggests that the L308V mutation weakens the I-helix packing, likely creating a cavity or clash that raises the energy of the folded state. For p.P387L, FoldX yielded a score of 1.50 ± 0.86 kcal/mol, and DUET gave 0.16 kcal/mol. While the FoldX score suggests destabilization, the large standard deviation indicates conformational heterogeneity. The loss of the proline’s rigidity likely increases the entropy of the unfolded state, shifting the equilibrium away from the native fold. Interestingly, the p.E162G variant showed a FoldX score of 1.80 ± 0.37 kcal/mol but a DUET score of -1.78 kcal/mol. The conflict suggests complex local dynamics, perhaps involving the flexibility of the D-helix. Among the neutral/stabilizing mutations (ΔΔG ~ 0), the p.S373N had a FoldX predicted score of -0.08 ± 0.08 kcal/mol, and for p.R76K, FoldX predicted score was 0.63 ± 0.10 kcal/mol, indicating that these substitutions are energetically neutral, consistent with their high allele frequencies and likely benign nature.

Figure 5.

Dynamic Structural Stability of CYP21A2 Variants Assessed by Cα Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Cα RMSD (Å) is plotted as a function of simulation time (in ns) for wild-type (WT) CYP21A2 and nine missense variants. (A) Trajectories for 50 ns MD simulations of apo forms of apo enzymes. (B) Trajectories for 100 ns MD simulations of enzyme-substrate (progesterone) complexes.

Figure 5.

Dynamic Structural Stability of CYP21A2 Variants Assessed by Cα Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Cα RMSD (Å) is plotted as a function of simulation time (in ns) for wild-type (WT) CYP21A2 and nine missense variants. (A) Trajectories for 50 ns MD simulations of apo forms of apo enzymes. (B) Trajectories for 100 ns MD simulations of enzyme-substrate (progesterone) complexes.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Assessing Dynamic Stability

When a mutation is introduced in an enzyme, it may have several effects depending on the nature of the mutated residue. Effects comprise steric effects caused by an increased size of the side chain of the mutated residue, electrostatic effects caused by changed protonation, local or even long-range conformational effects due to changed preferences of conformations of side chain and backbone (Gly and Pro) residues. Thus, the structure of a mutated CYP21A2 enzyme may be different or behave differently compared to the wild-type (WT) CYP21A2 enzyme and, accordingly, may present a different binding site to a substrate molecule, which may lead to altered biological activity.

We have performed MD simulations (50 ns) on the apo form of WT CYP21A2 and nine mutants to assess the behavior of the variants over time. We monitored the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the Cα backbone relative to the starting structure (

Figure 6A). The WT protein displayed a classic equilibration profile. The RMSD increased initially as the structure relaxed from the crystal lattice but quickly plateaued at approximately 1.7 Å, maintaining a stable trajectory for the duration of the simulation. This indicates a robust and rigid fold. In stark contrast, all the variant exhibited a different profile drifting towards structures with RMSD values between 2 and 3 Å relative to the initial structure. The profiles are not identical for the variants, but they are significantly different from the profile of the WT protein. It may not be surprising that the WT protein, which has been optimized by evolution, is more stable. We conclude that all variants impose some degree of flexibility into the CYP21A2 fold, but the present MD simulation are too short (50 ns) to unambiguously quantify the relative degree of stability and flexibility of the variants.

To identify if the variants are able to bind a substrate and form stable enzyme-substrate complexes, we performed MD simulations (100 ns) on the WT CYP21A2 complex with progesterone as well as on the progesterone complexes with the nine mutated enzymes. The RMSD for the WT complex fluctuated in the range 2.0-2.5 Å suggesting that the WT complex was slightly more flexible than the apo enzyme. The S274Y had a similar profile, whereas the H393Q and R401G variants immediately changed to structures with RMSD = 2.4 Å and 2.6 Å, respectively, and remained stable for the remaining simulation time. Two complexes, R76K and E162G, were significantly more stable than the WT complex. The remaining variants displayed different degrees of drifting, and we are cautious to conclude too much from these trajectories. Longer and multiple MD simulations would be required to make more firm conclusions.

Static stability predictions were complemented by 100 ns Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to assess the behavior of the variants over time. We monitored the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the Cα backbone relative to the starting structure (

Figure 6). The WT protein (

Figure 6A) displayed a classic equilibration profile. The RMSD increased initially as the structure relaxed from the crystal lattice but quickly plateaued at approximately 2.0 Å, maintaining a stable trajectory for the duration of the simulation. This indicates a robust and rigid fold. In stark contrast, the p.P387L variant exhibited a continuous “drifting” profile. The RMSD did not plateau but continued to rise, exceeding 3.5 Å by the end of the simulation. This behavior is indicative of a protein that is unraveling or exploring non-native conformations. The loss of the rigid proline at position 387 likely unlocks a degree of freedom in the K-L loop that destabilizes the entire domain, leading to progressive unfolding.

The p.L308V variant also showed instability, with significant RMSD fluctuations and a higher average deviation than WT. This dynamic instability corroborates the FoldX prediction; the mutation disrupts the tight packing of the I-helix, allowing the backbone to breathe excessively, which is detrimental to the precise positioning of catalytic residues. The p.R436C variant showed an RMSD profile closer to WT but with localized spikes. This suggests that the global fold remains intact (consistent with its surface location), but specific loops, likely those involved in POR binding, undergo aberrant conformational changes.

In Silico Pathogenicity Prediction: Consensus Analysis

We utilized a battery of 14 computational prediction tools to generate a consensus view of variant pathogenicity. The results, summarized in the “In silico pathogenicity prediction scores” Supplementary Table S5 and Figure S6, provide a preliminary basis for functional classification. Among the unanimous pathogenic consensus, p.P387L was classified as “Deleterious,” “Damaging,” or “Disease” by almost every tool. PolyPhen-2 gave it a score of 1.00 (Probably Damaging), CADD score was 24.7, p.H393Q was also universally considered disease causing with a PolyPhen-2 score 0.93, CADD 16.45, and DANN 0.98. The p.R436C also consistently scored as pathogenic (CADD 26, PolyPhen-2 1.00, SIFT 0). The p.L308V had a high pathogenic scores across the board (CADD 22.4, PolyPhen-2 1.0).

For the unanimous Benign Consensus, the p.S494N was classified as “Benign” or “Neutral” by almost all tools (CADD 0.16, PolyPhen-2 0.003) and p.R76K was also consistently Benign (CADD 12.56, PolyPhen-2 0.01). Mixed results (VUS) were obtained for p.E162G, which generated conflicting predictions. It was called “Possibly Damaging” by PolyPhen-2 (0.57) but “Tolerated” by SIFT (0.52). CADD score was 19.73. This pattern is typical of variants with mild or partial loss of function, often associated with Non-Classic CAH.

Figure 6.

In Silico Pathogenicity Prediction Consensus. A heatmap aggregating scores from 14 computational prediction tools (including CADD, PolyPhen-2, and SIFT) (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials). (Red) High Pathogenicity: The columns for p.L308V, p.P387L, and p.R436C are universally red, indicating a consensus “Deleterious” prediction. (Green) Benign: The columns for p.S494N and p.R76K are predominantly green/blue, indicating a “Benign” consensus. (Mixed) VUS: p.E162G shows conflicting scores (green and red), consistent with its mild functional impairment and association with Non-Classic CAH. Exact numbers are given in Supplementary Table S5. Data were normalized to fit outputs of different tools in one image to a range of 0-1.

Figure 6.

In Silico Pathogenicity Prediction Consensus. A heatmap aggregating scores from 14 computational prediction tools (including CADD, PolyPhen-2, and SIFT) (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials). (Red) High Pathogenicity: The columns for p.L308V, p.P387L, and p.R436C are universally red, indicating a consensus “Deleterious” prediction. (Green) Benign: The columns for p.S494N and p.R76K are predominantly green/blue, indicating a “Benign” consensus. (Mixed) VUS: p.E162G shows conflicting scores (green and red), consistent with its mild functional impairment and association with Non-Classic CAH. Exact numbers are given in Supplementary Table S5. Data were normalized to fit outputs of different tools in one image to a range of 0-1.

Functional Characterization: Protein Expression and Enzymatic Activity

The most definitive evidence for pathogenicity comes from the direct measurement of protein function in vitro. We expressed the variants in HEK293T cells and measured both their steady-state protein levels (Western blot) and their enzymatic activity using radiolabeled Progesterone and 17-OHP.

Protein Expression Levels (Western Blot)

The Western blot data (

Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S2) revealed significant differences in protein stability. Reduced stability was observed for p.L308V and p.R436C which showed markedly reduced protein levels, at approximately 46% and 49% of WT, respectively. This reduction confirms that these mutations destabilize the protein, likely leading to increased turnover or aggregation. For p.L308V, this matches the FoldX and MD data perfectly. Surprisingly, p.H393Q (159%) and p.P387L (122%) showed protein levels higher than WT. Despite the FoldX prediction of severe destabilization, these proteins accumulate in the cell. This accumulation might represent insoluble aggregates or a failure of the degradation machinery to clear the mutant protein. Crucially, as this high protein abundance did not translate into high activity.

Enzymatic Activity Analysis

Enzymatic activity was measured for the conversion of Progesterone (to 11-DOC) and 17-OHP (to 11-Deoxycortisol). The results are presented as a percentage of WT activity, normalized to protein expression (

Figure 7, Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 7.

Enzymatic Activity: Progesterone and 17-Hydroxyprogesterone Conversion. Bar graphs depicting the 21-hydroxylation of Progesterone. (A) Raw activity (% of WT). (B) Activity normalized to protein expression. The p.L308V and p.R436C variants show severe loss of function (<30%), while p.H393Q and p.R401G display moderate impairment (40-70%), characteristic of Non-Classic alleles. C and D, Bar graphs depicting the conversion of 17-OHP, the rate-limiting step for cortisol synthesis. (C) Raw activity. (D) Normalized activity. The variants p.L308V, p.P387L, and p.R436C exhibit severe catalytic failure (<20% activity), definitively classifying them as pathogenic alleles associated with Simple Virilizing CAH. p.L10del retains ~99% activity, confirming its benign status. The dissociation between Progesterone and 17-OHP activity for p.P387L highlights substrate-specific impairment.

Figure 7.

Enzymatic Activity: Progesterone and 17-Hydroxyprogesterone Conversion. Bar graphs depicting the 21-hydroxylation of Progesterone. (A) Raw activity (% of WT). (B) Activity normalized to protein expression. The p.L308V and p.R436C variants show severe loss of function (<30%), while p.H393Q and p.R401G display moderate impairment (40-70%), characteristic of Non-Classic alleles. C and D, Bar graphs depicting the conversion of 17-OHP, the rate-limiting step for cortisol synthesis. (C) Raw activity. (D) Normalized activity. The variants p.L308V, p.P387L, and p.R436C exhibit severe catalytic failure (<20% activity), definitively classifying them as pathogenic alleles associated with Simple Virilizing CAH. p.L10del retains ~99% activity, confirming its benign status. The dissociation between Progesterone and 17-OHP activity for p.P387L highlights substrate-specific impairment.

Severe Loss of Function (Pathogenic - Simple Virilizing): The p.L308V, an Ultra-rare (5 x 10

-8 in gnomAD) is a destabilizing ΔΔG 2.1 kcal/mol) and MD simulations show drifting RMSD (

Figure 5). It had 17-OHP Activity of 18.15% ± 11.30% (p < 0.001) while activity with Progesterone as a substrate was 30.21% ± 16.66% (p < 0.001) of WT. The p.L308V retains less than 20% of normal activity for the key cortisol precursor. This places it firmly in the pathogenic category, likely causing Simple Virilizing (SV) CAH (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). This resolves the conflict with the null p.L308fs mutation; p.L308V is distinct but still severe. The p.P387L had activity with 17-OHP as substrate only 19.13% ± 1.28% (p < 0.001) of the WT, while with Progesterone it showed an Activity of 52.37% ± 0.37% compared to WT. Interestingly, protein levels are high (122%), suggesting the formation of inactive aggregates that escape immediate degradation but cannot function.

This difference in activities with two different common substrates of CYP21A2 shows a significant substrate dissociation. While progesterone activity is preserved at 50% (NC range), 17-OHP activity is reduced to ~19% (SV range). Since cortisol deficiency drives CAH, the low 17-OHP activity dictates the clinical phenotype, classifying this as a pathogenic variant likely causing SV or severe NC CAH. The p.R436C had a 17-OHP Activity of 17.97% ± 6.51% (p < 0.001) and with Progesterone it showed an Activity of 26.20% ± 22.66% (p < 0.001) compared to WT. With <20% activity, p.R436C is a severe allele (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). The impairment of both substrates confirms that the disruption of the POR binding site (predicted by structure) catastrophically reduces the electron transfer efficiency required for catalysis.

Moderate Loss of Function (Likely Pathogenic - Non-Classic): The p.H393Q showed a 17-OHP Activity: 44.01% ± 0.26% (p < 0.001) and with Progesterone its Activity was 70.43% ± 0.44% of WT. The activity is reduced to the 40-50% range. This is the classic hallmark of a Non-Classic (NC) allele. It is not a null mutation, but it is insufficient for normal stress responses. Protein levels are high (159%), likely due to aggregation of the unstable mutant. For p.R401G a 17-OHP Activity of 41.41% ± 10.44% and with Progesterone an Activity of 39.96% ± 9.92% was observed. This consistent ~40% activity across substrates confirms p.R401G as a pathogenic mutation associated with the NC phenotype. For p.E162G we saw a 17-OHP Activity of 52.85% ± 12.3%, indicating a mild NC allele or a very rare polymorphism with functional impact (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Categorization of CYP21A2 variants.

Figure 9.

Categorization of CYP21A2 variants.

Benign Function: This trinucleotide deletion resulting in missing Leu 10 residue in the N-terminal membrane anchor is ubiquitous. Allele frequencies reach 46% in Ashkenazi Jewish populations and 30% in Japanese cohorts. Structurally, Leu10 resides in the flexible transmembrane tether, a region with low conservation scores (ConSurf score 3) that does not participate in catalysis. Functional assays confirm this, showing ~99% of WT activity for 17-OHP and ~110% for Progesterone. p.S373N located on a surface loop, has a neutral free energy change ΔΔG -0.08 kcal/mol). Functional activity at ~93% is indistinguishable from the wild type. The conservative substitution of Arginine to Lysine in p.R76K maintains the positive charge on the protein surface. It is highly exposed (RSA ~69%) and energetically neutral (ΔΔG ~0.6 kcal/mol). Functional assays show ~76% activity. While ALFA reports a high frequency (0.51), gnomAD reports it as rare (10-4), suggesting database artifacts or specific population clusters. The biochemical data supports a benign status. The p.S494N variant shows distinct ethnic stratification, being common (>5%) in East Asian populations but rare in others. It is located in the disordered C-terminal tail (residue 494), which has poor electron density in crystal structures and low conservation (ConSurf score ~4). Functional activity is ~67% for 17-OHP, a reduction that is statistically significant but clinically irrelevant given the high population frequency in healthy individuals. It functions as a benign polymorphism with slightly reduced efficiency.

Structural Mechanisms of Dysfunction

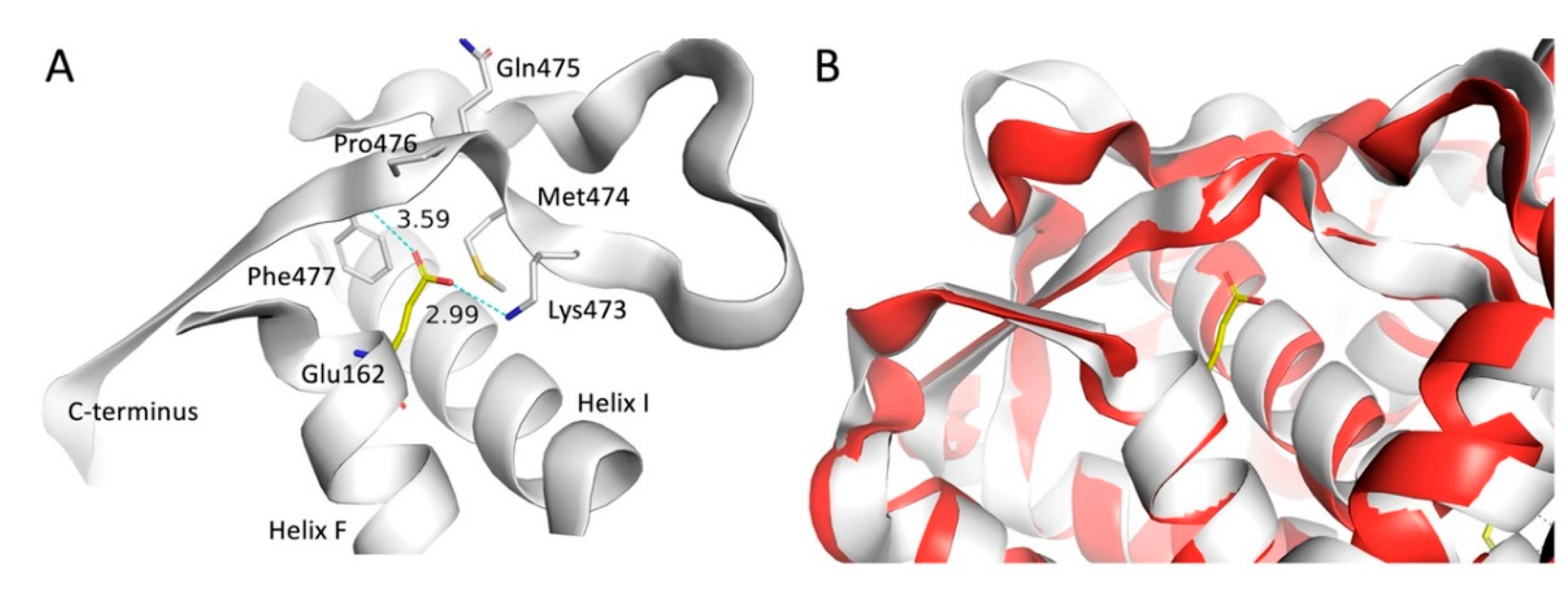

To explain why these mutations cause enzymatic failure, we analyzed the specific molecular interactions in the modeled mutant structures (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). The mutation of glutamate to glycine in the p.E162G variant represents a major structural modification with at least two likely consequences, destabilization of the 3D structure due to lack of hydrogen bonds to the negatively charged sidechain in Glu162 and increased flexibility associated with a glycine residue compared to any alpha-substituted residue. The Glu162 residue is located at the beginning of Helix F with its sidechain pointing across Helix I and forming hydrogen bonds with the sidechain nitrogen atom in Lys473 and the backbone nitrogen atom in Phe477 located in the C-terminal part of the CYP21A2 structure (

Figure 1A). A MD simulation of the E162G variant showed no significant conformational change of the C-terminal part (

Figure 1B).

Figure 10.

Structural consequence of the p.E162G substitution in CYP21A2. (A) WT CYP21A2 with Glu162 and environment formed by Helix F, Helix I and the C-terminus. Hydrogen bonds from Lys473 and Phe477 are shown as dotted lines. (B) Initial (white) and final (red) frames from MD simulation of CYP21A2 E162G shown as cartoon through the Cα atoms. The Glu162 from WT CYP21A2 have been added to the figure to illustrate the point of mutation.

Figure 10.

Structural consequence of the p.E162G substitution in CYP21A2. (A) WT CYP21A2 with Glu162 and environment formed by Helix F, Helix I and the C-terminus. Hydrogen bonds from Lys473 and Phe477 are shown as dotted lines. (B) Initial (white) and final (red) frames from MD simulation of CYP21A2 E162G shown as cartoon through the Cα atoms. The Glu162 from WT CYP21A2 have been added to the figure to illustrate the point of mutation.

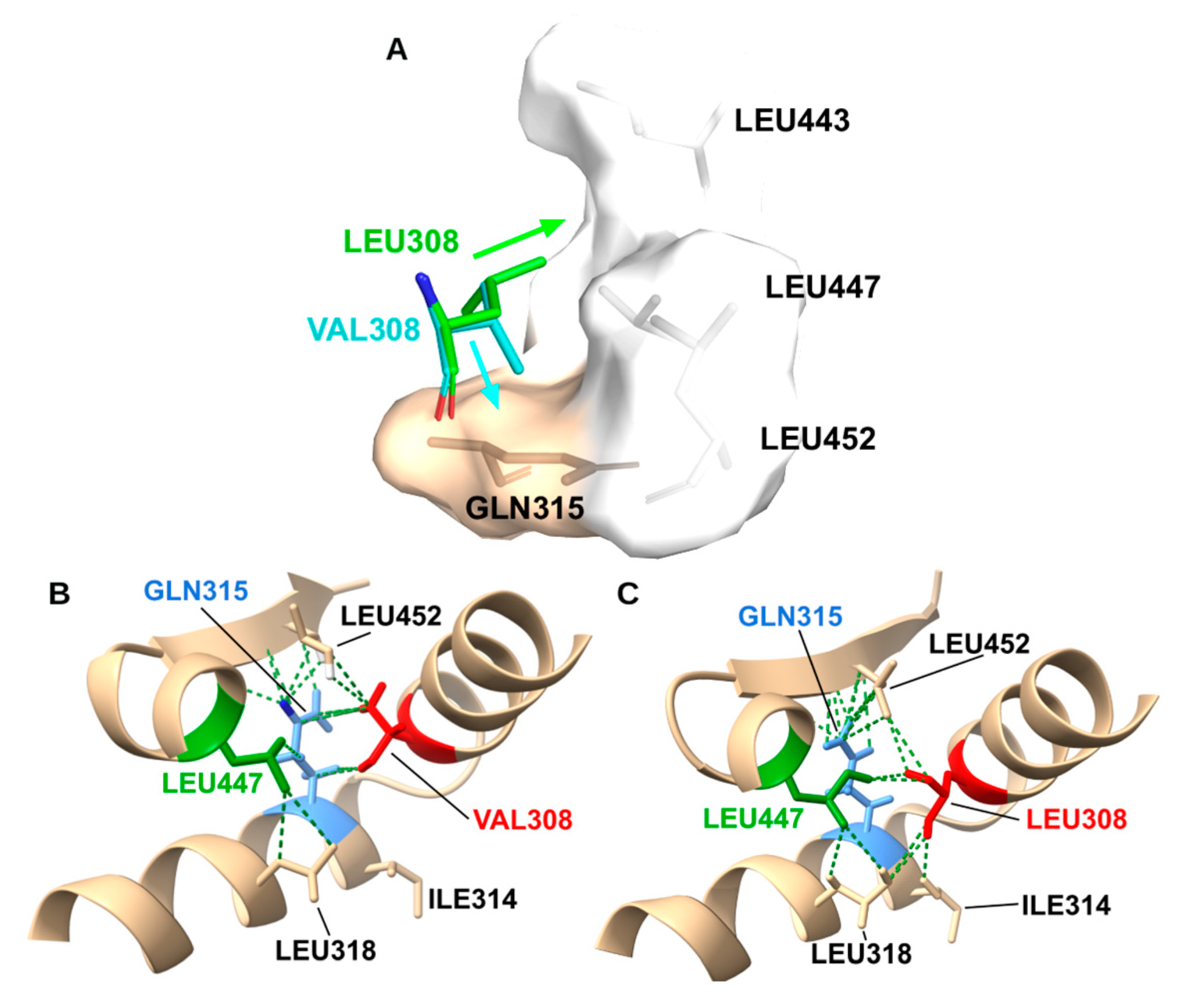

In the WT structure, Leu308 is a keystone residue in the I-helix. Its bulky isobutyl side chain interlocks with Leu318, Ile314, Leu447, and Leu452, creating a hydrophobic network that stabilizes the “kink” in the I-helix essential for oxygen activation (

Figure 11A). The p.L308V mutation introduces a Valine, which while chemically similar, has a different shape (β-branched). Our modeling reveals that the specific rotamer of Valine required to fit in the helix backbone induces a steric clash with Gln315 (

Figure 11B). Simultaneously, the shorter side chain creates a hydrophobic cavity in the packing network with L447/L452. The combination of a steric clash (distorting the backbone) and a packing cavity (destabilizing the core) disrupts the precise geometry of the I-helix. Since the I-helix is responsible for delivering protons to the heme iron, this disruption uncouples the catalytic cycle, explaining the 18% residual activity.

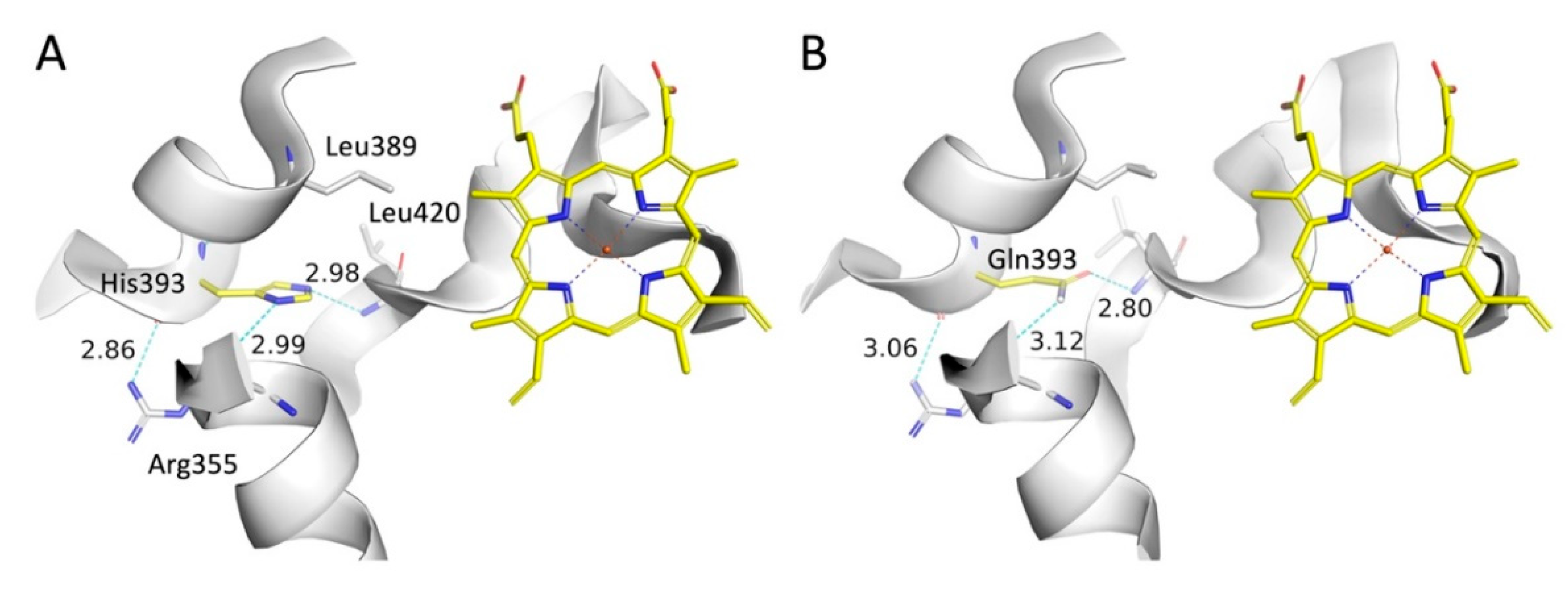

In the p.H393Q variant a histidine is replaced by a glutamine, which must be characterized as a conservative mutation since the sidechains are equal in length, and both contain a hydrogen bond acceptor and a hydrogen bond donor. In the WT CYP21A2 His393 imidazole ring donates a hydrogen bond to the backbone oxygen atom in Arg355 and accept a hydrogen bond from the backbone nitrogen atom in Leu420 (

Figure 12A). The hydrogen bonding pattern is maintained in the mutated form and remains stable during a MD simulation (

Figure 12B).

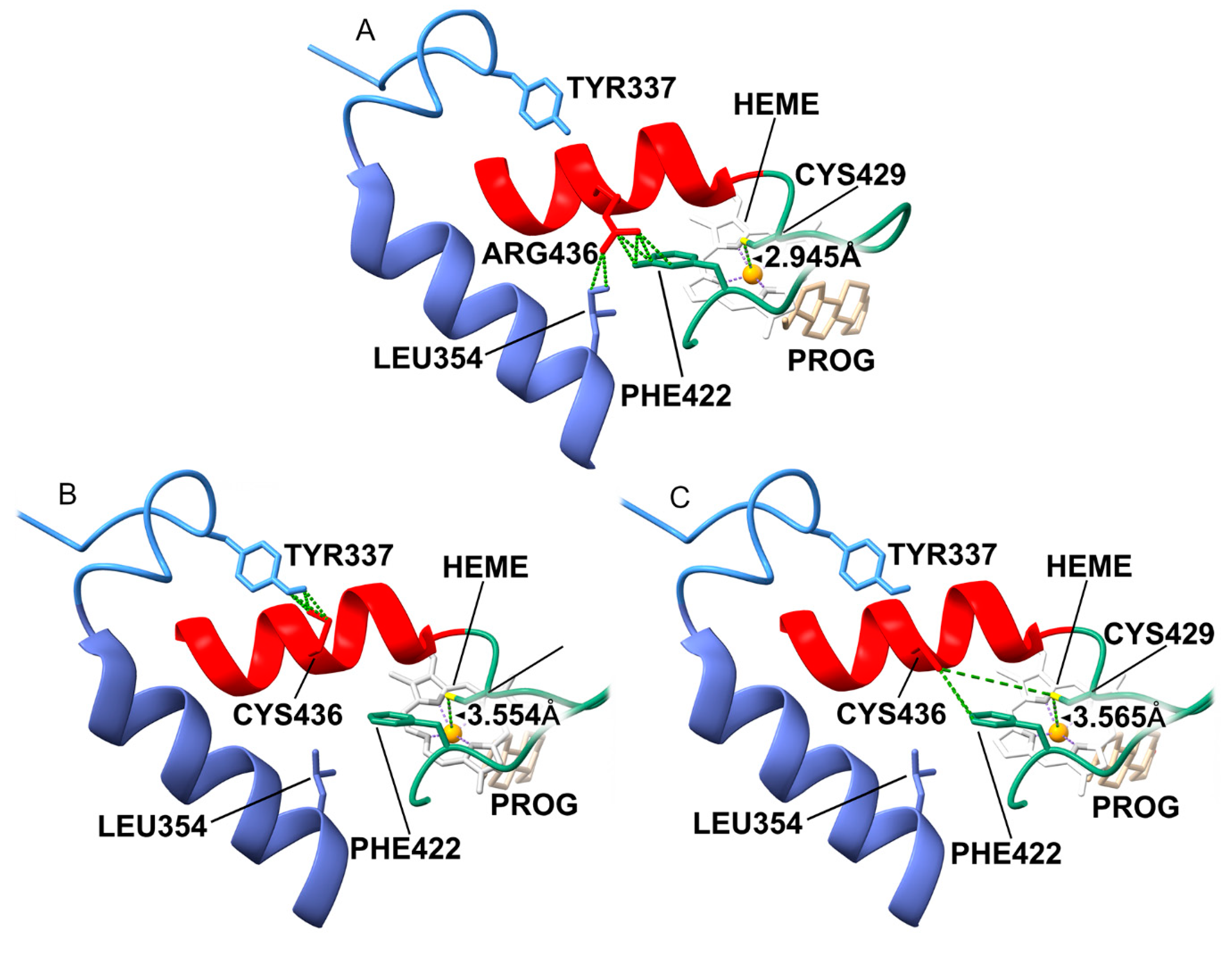

Arg436 acts as a molecular “strut” on the protein surface. In WT, the long Arg436 side chain forms a crucial hydrogen-bond network with Leu354 (J-helix) and Phe422 (

Figure 13A). This network stabilizes the loop containing Cys429, the thiolate ligand that holds the heme iron in place. The mutation to Cysteine (p.R436C) removes this long reach. (

Figure 13B) The short Cysteine cannot bridge the gap to L354 or F422. Without the Arg436 residue, the Cys429-loop becomes flexible. Our model predicts that the Cys429 sulfur atom shifts away from the heme iron, increasing the bond distance from 2.9 Å (optimal) to 3.6 Å (dysfunctional) (

Figure 13C). This increased distance weakens the ligand field strength, altering the redox potential of the heme and making electron transfer from POR inefficient. This explains why a surface mutation causes such a profound (18% activity) catalytic defect.

Discussion

This study represents a definitive functional and structural interrogation of eleven CYP21A2 variants, resolving determining their status from “uncertain” to clinically actionable categories. By synthesizing data from global population frequencies, evolutionary biology, thermodynamic stability, and direct enzymatic assays, we have constructed a comprehensive profile for each variant. The primary clinical imperative of this work was to clarify the pathogenicity of variants with conflicting or absent data. The clinical interpretation of variants at codon 308 has historically been fraught with ambiguity due to the presence of the p.L308fs frameshift allele. This frameshift, resulting from a microdeletion, leads to a truncated, non-functional protein and is a well-documented cause of classic salt-wasting CAH. However, the missense variant p.L308V (c.922T>G) has frequently been conflated with the null allele in clinical databases, leading to conflicting reports regarding its severity. Our study provides the first definitive functional and structural separation of these two entities. While p.L308fs is a null mutation, our data demonstrates that p.L308V is a stable but severely catalytically compromised variant. Structural modeling reveals that the substitution of the leucine isobutyl side chain with the valine isopropyl group, a seemingly conservative change, has significant geometric consequences. The valine side chain induces a specific steric clash with Gln315 and creates a hydrophobic cavity within the highly conserved I-helix. This helix is not merely a structural scaffold; it contains the conserved acid-alcohol pair essential for proton delivery to the heme-bound oxygen intermediate. The distortion of this helix uncouples the proton transfer pathway, explaining the ~18% residual activity observed for 17-OHP. This finding firmly places p.L308V in the pathogenic category, likely associated with the Simple Virilizing (SV) phenotype rather than the Salt-Wasting form seen with the frameshift. Clinically, this distinction is vital: patients carrying p.L308V may have sufficient residual aldosterone production to avoid neonatal salt-wasting crises but remain at high risk for postnatal virilization, necessitating a distinct monitoring protocol.

A central tenet of protein engineering suggests that mutations in the hydrophobic core are destabilizing, while surface mutations are generally tolerated unless they disrupt specific binding sites. Our characterization of p.R436C challenges this simplification in the context of

CYP21A2 (

Figure 14). Despite its high solvent accessibility (RSA >30%) and significant distance from the active site, p.R436C exhibits a catastrophic loss of enzymatic function (<20% activity), comparable to core-destabilizing mutations like p.L308V. We elucidate a novel ‘remote control’ mechanism for this dysfunction. Arg436 acts as a molecular anchor on the protein surface, maintaining a crucial hydrogen-bond network with Leu354 and Phe422. This network rigidifies the internal loop containing Cys429, the proximal thiolate ligand that coordinates the heme iron. Our structural modeling predicts that the p.R436C mutation severs this network, increasing the entropy of the Cys429 loop and causing the sulfur atom to shift away from the iron (Fe-S distance increases from 2.9 Å to ~3.6 Å). This alteration in coordination geometry likely perturbs the redox potential of the heme, impairing the transfer of electrons from P450 Oxidoreductase (POR). Thus, p.R436C represents a ‘functional’ mutation where the protein fold is intact (as evidenced by stable MD trajectories and Western blot), but the catalytic engine is uncoupled from its fuel source. This finding underscores the critical importance of analyzing surface VUS for their role in the obligate protein-protein interaction interfaces that drive P450 function. The p.P387L showed core Instability, with a drifting RMSD profile in MD (structural unraveling) and low 17-OHP activity (19%) and is reclassified as Pathogenic (SV/NC). The kinetic instability suggests that patients might have a “temperature-sensitive” phenotype, where fever or stress precipitates a drop in enzyme function, triggering adrenal crises.

The p.H393Q and p.R401G show intermediate activity (40-45%) and significant destabilization scores and are reclassified as Likely Pathogenic (Non-Classic). These variants are likely responsible for Late-Onset CAH. The stark divergence in allele frequencies observed for p.H393Q and p.S494N emphasizes the necessity of ancestry-matched reference populations in genetic diagnosis. While p.H393Q is effectively absent in European cohorts (ExAC/gnomAD), our analysis reveals a significant enrichment in East Asian databases (Japanese and Korean frequency ~4.5%). Our functional assays characterize p.H393Q as a Non-Classic allele with ~44% residual activity. The combination of high frequency and moderate functional impairment strongly suggests a ‘founder effect’ in East Asian populations, where the allele has drifted to higher prevalence, possibly maintained by the lack of strong negative selection against the milder non-classic phenotype. Similarly, p.S494N appears as a common polymorphism in Asian cohorts (>5%) but is rare elsewhere. The identification of these population-specific alleles has immediate clinical implications. For a patient of East Asian descent presenting with signs of late-onset CAH (e.g., hirsutism, fertility issues), p.H393Q should be a primary target for genotyping. Conversely, its detection in a European patient would be an anomaly requiring careful segregation analysis. Furthermore, the high frequency of the benign p.S494N variant in Asian populations mandates its exclusion from standard diagnostic panels to prevent false-positive diagnoses and unnecessary anxiety for carriers. These findings argue for the implementation of ethnicity-specific filtering in CAH diagnostic pipelines.

Equally important is the removal of benign variants from disease panels to prevent false positives. The p.L10del and p.S494N are widespread polymorphisms with near-WT activity (~100% and ~67% respectively) and variable conservation. They should be classified as Benign and removed from diagnostic consideration for CAH. The p.R76K and p.S373N are also Benign, showing high exposure, low conservation, and normal activity. The distinct mechanisms identified, core destabilization (L308V, P387L) versus surface uncoupling (R436C), suggest different therapeutic possibilities. Core-destabilized mutants are prime candidates for pharmacological chaperone therapy, where small molecules bind to and stabilize the folded state, potentially rescuing the ~18% residual activity to a level sufficient to prevent symptoms. Surface mutants like R436C, which are stable but catalytically inefficient, might require different approaches.

The mechanistic stratification of pathogenic variants into ‘core destabilizers’ and ‘surface disruptors’ provides a roadmap for future precision therapies (

Figure 15). Core-destabilized mutants, such as p.P387L and p.L308V, are characterized by high thermodynamic instability and kinetic unfolding (drifting MD trajectories), yet they often retain the essential catalytic residues. These variants represent ideal candidates for pharmacological chaperone therapy. Small molecules or substrate analogs that bind to the active site could stabilize the folded state, shifting the equilibrium away from unfolded intermediates and rescuing the protein from endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD). Rescuing even a fraction of the enzyme’s activity could be sufficient to convert a severe salt-wasting phenotype into a manageable non-classic form. In contrast, surface mutants like p.R436C, which are thermodynamically stable but functionally decoupled from POR, would likely be refractory to stabilization therapies. For these variants, therapeutic strategies must focus on enhancing the efficiency of the electron transfer complex, perhaps through the modulation of redox partner interactions or gene therapy approaches. By moving beyond a binary ‘pathogenic vs. benign’ classification to a mechanistic understanding of why a variant fails, we pave the way for targeted interventions tailored to the specific molecular defect

While this study utilized a robust HEK293T system, limitations exist. The ratio of POR to P450 in kidney cells differs from the adrenal cortex, which could affect the absolute Vmax values. Furthermore, we focused on the classic pathway; future studies should investigate the impact of these variants on the 11-oxygenated androgen pathway (e.g., 11-ketotestosterone), which is increasingly recognized as a key driver of androgen excess in CAH. Overall, this study elevates the status of p.L308V, p.R436C, p.P387L, p.H393Q, and p.R401G to Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic, while definitively clearing p.L10del and p.S494N. These findings refine the genetic map of CAH, empowering clinicians to provide more accurate diagnoses and personalized care for affected families.

Conclusions

This study addresses a critical gap in the molecular diagnosis of 21-hydroxylase deficiency by providing a definitive functional and structural characterization of eleven

CYP21A2 variants previously classified as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) or having conflicting interpretations. By integrating population data, evolutionary conservation, thermodynamic stability predictions, and direct enzymatic assays, we have successfully reclassified these variants into clinically actionable categories ranging from Benign to Pathogenic (

Figure 16 and

Table 1). Our results exonerate the variants p.L10del, p.S494N, p.R76K, and p.S373N. The high population frequency of p.L10del and p.S494N, combined with their retention of near-wild-type enzymatic activity (66%–99%), confirms they are benign polymorphisms that should be excluded from diagnostic panels to prevent false-positive diagnoses.

Conversely, we provide robust evidence for the pathogenicity of p.L308V, p.P387L, and p.R436C. The p.L308V variant, often confused with the p.L308fs frameshift, is confirmed here as a distinct, severe missense mutation. Structural modeling demonstrates that it destabilizes the I-helix via steric clashes and cavity formation, resulting in a residual activity of ~18% for 17-OHP, consistent with the Simple Virilizing phenotype. Similarly, p.P387L causes severe core destabilization and dynamic instability, while p.R436C disrupts the critical interface with P450 Oxidoreductase, impairing electron transfer despite being located on the protein surface. Both retain < 20% activity and are classified as Pathogenic.

Furthermore, we identified p.H393Q, p.R401G, and p.E162G as alleles associated with moderate loss of function (40–55% residual activity). These variants are likely drivers of the Non-Classic CAH phenotype, with p.H393Q showing a specific enrichment in Asian populations, suggesting a founder effect. In summary, this work refines the genotype-phenotype correlation map for CAH. The elucidation of specific molecular mechanisms, ranging from core destabilization to surface uncoupling, not only resolves diagnostic ambiguity but also highlights potential targets for future pharmacological chaperone therapies aimed at rescuing unstable mutant proteins. These findings will immediately improve the accuracy of genetic counseling and clinical management for patients carrying these specific CYP21A2 alleles.

Figure 2.

Global Allele Frequency Heatmap of CYP21A2 Variants. A heatmap visualization of allele frequencies derived from large-scale population databases (gnomAD, ExAC, TOPMed, ALFA, 1000 Genomes). The color intensity correlates with allele frequency. The p.L10del row displays “hot” colors (orange/red) across multiple populations, indicating frequencies of 20-46%, confirming its status as a common benign polymorphism. p.S494N shows “warm” colors specifically in East Asian and South Asian columns, reflecting an ethnicity-specific polymorphism. The rows for R76K, p.P387L, and p.H393Q are dominated by “cool” colors (blue/green), representing ultra-rare frequencies (<10-4) or absence in general populations, a distribution pattern consistent with alleles under negative selection pressure due to pathogenicity.

Figure 2.

Global Allele Frequency Heatmap of CYP21A2 Variants. A heatmap visualization of allele frequencies derived from large-scale population databases (gnomAD, ExAC, TOPMed, ALFA, 1000 Genomes). The color intensity correlates with allele frequency. The p.L10del row displays “hot” colors (orange/red) across multiple populations, indicating frequencies of 20-46%, confirming its status as a common benign polymorphism. p.S494N shows “warm” colors specifically in East Asian and South Asian columns, reflecting an ethnicity-specific polymorphism. The rows for R76K, p.P387L, and p.H393Q are dominated by “cool” colors (blue/green), representing ultra-rare frequencies (<10-4) or absence in general populations, a distribution pattern consistent with alleles under negative selection pressure due to pathogenicity.

Figure 8.

Summary of stability, functional and enzyme assays.

Figure 8.

Summary of stability, functional and enzyme assays.

Figure 11.

Structural Mechanism of p.L308V: I-Helix Destabilization. (A) The WT Leu308 residue forms a tight hydrophobic packing network within the conserved I-helix. (B) The p.L308V mutation introduces a Valine. Modeling shows that the specific rotamer required for Valine creates a steric clash with Gln315 and a packing void (cavity) due to the shorter side chain. (C) This disruption distorts the I-helix geometry, which is essential for proton delivery to the heme iron, thereby uncoupling the catalytic cycle.

Figure 11.

Structural Mechanism of p.L308V: I-Helix Destabilization. (A) The WT Leu308 residue forms a tight hydrophobic packing network within the conserved I-helix. (B) The p.L308V mutation introduces a Valine. Modeling shows that the specific rotamer required for Valine creates a steric clash with Gln315 and a packing void (cavity) due to the shorter side chain. (C) This disruption distorts the I-helix geometry, which is essential for proton delivery to the heme iron, thereby uncoupling the catalytic cycle.

Figure 12.

Comparison of CYP21A2 WT and H393Q interactions. (A) The imidazole ring in the WT structure makes hydrogen bonds with the Arg355 sidechain and the Leu420 backbone nitrogen. (B) In the Gln393 variant the amide sidechain maintains an identical hydrogen network with the carbonyl oxygen and nitrogen atoms being hydrogen bond acceptor and donor, respectively. The (B) structure is the final structure after a 100 ns MD simulation.

Figure 12.

Comparison of CYP21A2 WT and H393Q interactions. (A) The imidazole ring in the WT structure makes hydrogen bonds with the Arg355 sidechain and the Leu420 backbone nitrogen. (B) In the Gln393 variant the amide sidechain maintains an identical hydrogen network with the carbonyl oxygen and nitrogen atoms being hydrogen bond acceptor and donor, respectively. The (B) structure is the final structure after a 100 ns MD simulation.

Figure 13.

Structural Mechanism of p.R436C: Heme-Ligand Interface Disruption. (A) In WT, Arg436 forms a surface hydrogen-bond network with Leu354 and Phe422, stabilizing the loop containing the heme-ligating Cysteine 429. (B) The p.R436C mutation abolishes this network. (C) The loss of the Arg436 “strut” increases the flexibility of the Cys429 loop, causing the Cys429 sulfur to shift away from the heme iron (distance increases to ~3.6 Å). This alteration in the ligand field impairs electron transfer from P450 Oxidoreductase, causing severe activity loss despite the surface location of the mutation.

Figure 13.

Structural Mechanism of p.R436C: Heme-Ligand Interface Disruption. (A) In WT, Arg436 forms a surface hydrogen-bond network with Leu354 and Phe422, stabilizing the loop containing the heme-ligating Cysteine 429. (B) The p.R436C mutation abolishes this network. (C) The loss of the Arg436 “strut” increases the flexibility of the Cys429 loop, causing the Cys429 sulfur to shift away from the heme iron (distance increases to ~3.6 Å). This alteration in the ligand field impairs electron transfer from P450 Oxidoreductase, causing severe activity loss despite the surface location of the mutation.

Figure 14.

Mechanistic Classification of Variants. A summary of structural parameters (RSA) and functional data (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials). Purple (Buried/Core Destabilizers): p.L308V, p.P387L. Low RSA, high thermodynamic instability. Red (Surface Functional Disruptors): p.R436C, p.R401G. High RSA, severe functional impairment due to disrupted protein-protein or ligand interactions. Green (Benign Surface Variants): p.L10del, p.S494N. High RSA, normal function.

Figure 14.

Mechanistic Classification of Variants. A summary of structural parameters (RSA) and functional data (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials). Purple (Buried/Core Destabilizers): p.L308V, p.P387L. Low RSA, high thermodynamic instability. Red (Surface Functional Disruptors): p.R436C, p.R401G. High RSA, severe functional impairment due to disrupted protein-protein or ligand interactions. Green (Benign Surface Variants): p.L10del, p.S494N. High RSA, normal function.

Figure 15.

Genotype-phenotype linkage based on multiple parameters. Color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials.

Figure 15.

Genotype-phenotype linkage based on multiple parameters. Color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials.

Figure 16.

Revised Clinical Classification Scheme. A proposed “Traffic Light” diagnostic algorithm (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials). Red (Pathogenic/SV): p.L308V, p.P387L, p.R436C. (Action: Carrier screening, high CAH risk). Orange (Likely Pathogenic/NC): p.H393Q, p.R401G, p.E162G. (Action: Monitor for late-onset symptoms). Green (Benign): p.L10del, p.S494N, p.R76K, p.S373N. (Action: Exclude from panels).

Figure 16.

Revised Clinical Classification Scheme. A proposed “Traffic Light” diagnostic algorithm (color version of figure is in Supplementary Materials). Red (Pathogenic/SV): p.L308V, p.P387L, p.R436C. (Action: Carrier screening, high CAH risk). Orange (Likely Pathogenic/NC): p.H393Q, p.R401G, p.E162G. (Action: Monitor for late-onset symptoms). Green (Benign): p.L10del, p.S494N, p.R76K, p.S373N. (Action: Exclude from panels).

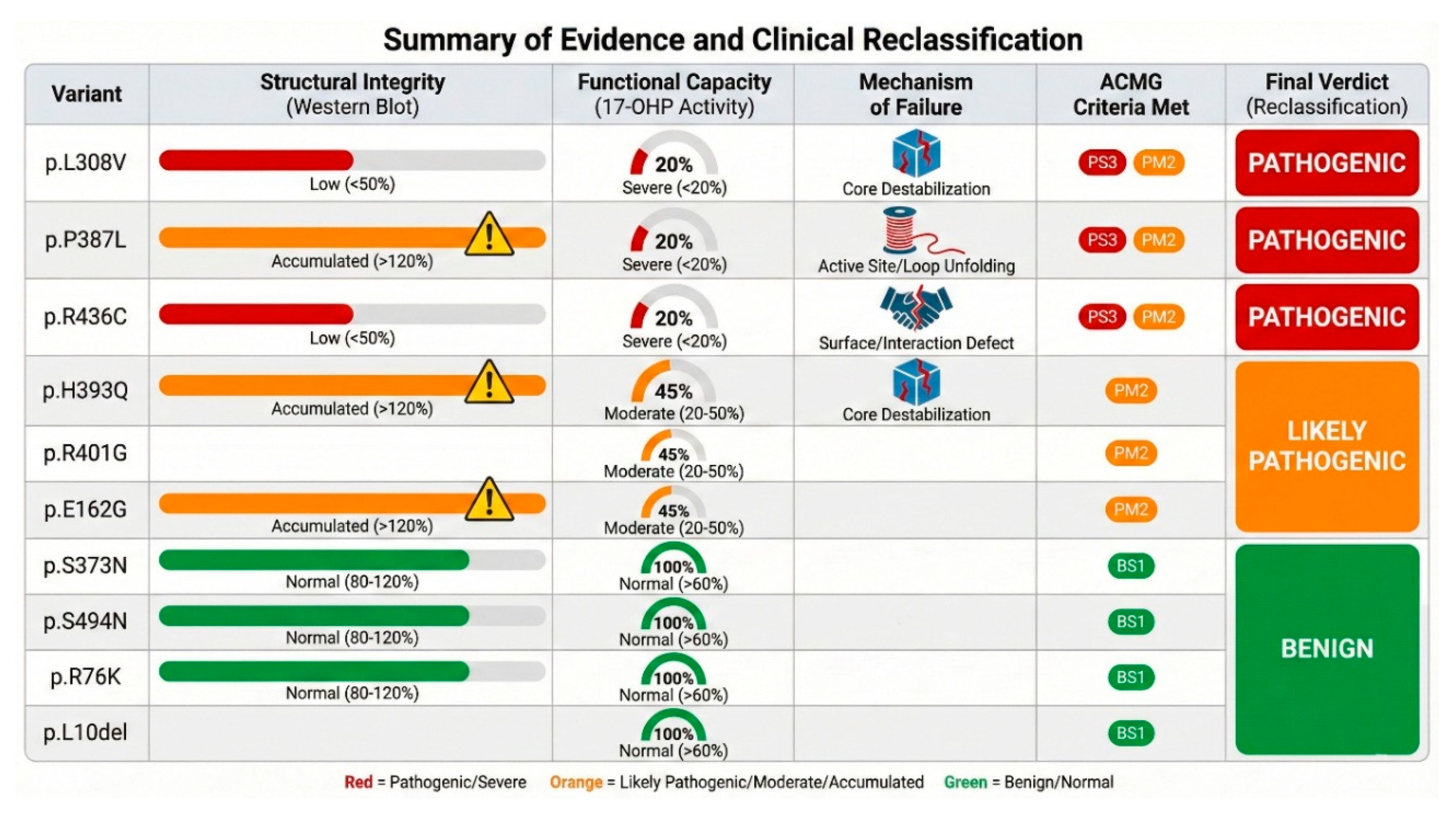

Table 1.

Summary of evidence and proposed reclassification of CYP21A2 variants. ACMG Codes: PS3 (Functional studies show deleterious effect), PM1 (Hotspot/functional domain), PM2 (Absent from controls), PP3 (Computational evidence), BS1 (Allele frequency too high), BP4 (Computational evidence suggests benign).

Table 1.

Summary of evidence and proposed reclassification of CYP21A2 variants. ACMG Codes: PS3 (Functional studies show deleterious effect), PM1 (Hotspot/functional domain), PM2 (Absent from controls), PP3 (Computational evidence), BS1 (Allele frequency too high), BP4 (Computational evidence suggests benign).

| Variant |

Initial ClinVar |

Activity (Prog) % |

Activity (17OHP) % |

Protein Level % |

Structural Mechanism |

Applicable ACMG Criteria |

Proposed Classification |

Predicted Phenotype |

| p.L10del |

Benign |

~111% |

~99% |

~85% |

N-term flexible anchor |

BA1, BS1 |

Benign |

Normal |

| p.R76K |

VUS |

~72% |

~77% |

~142% |

Surface loop, exposed |

BS1, BP4 |

Likely Benign |

Normal |

| p.E162G |

VUS |

~58% |

~53% |

~162% |

Surface stability |

PM1, PM2, PP3 |

Likely Pathogenic |

NC-CAH |

| p.S274Y |

N/A |

~76% |

~46% |

~106% |

Surface loop |

BP4, BS1 |

VUS / Likely Benign |

Normal/Carrier |

| p.L308V |

Likely Path. |

~30% |

~18% |

~46% |

I-helix destabilization, steric clash |

PS3, PM1, PM2, PP3 |

Pathogenic |

SW/SV CAH |

| p.S373N |

Likely Path. |

~92% |

~93% |

~92% |

Surface loop |

BS3, BP4 |

Benign |

Normal |

| p.P387L |

Likely Path. |

~53% |

~19% |

~122% |

Core/K-L loop destabilization |

PS3, PM1, PM2, PP3 |

Pathogenic |

SW/SV CAH |

| p.H393Q |

Likely Benign |

~71% |

~44% |

~159% |

Core packing disruption |

PM1, PM2, PP3 |

Likely Pathogenic |

NC-CAH |

| p.R401G |

VUS |

~40% |

~41% |

~72% |

Surface charge/POR binding |

PS3, PM1, PM2 |

Pathogenic |

SV/NC CAH |

| p.R436C |

Likely Benign |

~26% |

~18% |

~49% |

POR interface/Heme geometry |

PS3, PM1, PM2 |

Pathogenic |

SV/NC CAH |

| p.S494N |

Benign |

~100% |

~67% |

~99% |

C-term disordered tail |

BA1, BS1 |

Benign |

Normal |