1. Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis is a fatal form of interstitial lung diseases and is chronic, progressive, and irreversible [

1]. It is characterized by the progressive accumulation of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix in the lung [

2]. The fibrotic process is associated with chronic inflammation, metabolic homeostasis, and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) signaling, and the balance between oxidant and antioxidant systems appears to be a key modulator in the regulation of these processes [

3]. Dysregulation of the immune system, together with inflammation, plays a role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. In addition, the process of fibroblast activation also contributes to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. From this perspective, it can be concluded that both inflammatory and epithelial pathways lead to the development of lung fibrosis [

4].

Although smoking is known to be a triggering factor in the development of fibrosis [

5], genetic and environmental factors may also lead to the formation of pulmonary fibrosis [

6]. In addition, pulmonary fibrosis can occur as a result of viral infections, most notably herpesviruses. Previous studies have reported that SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19), Torque teno virus and Epstein–Barr virus can induce pulmonary fibrosis [

7,

8]. Moreover, Additionally, several conditions, including lung cancer, atherosclerosis, gastroesophageal reflux, and diastolic dysfunction, are also thought to be associated with the development of pulmonary fibrosis. The TGF-β/SMAD pathway is one of the best-known fundamental signaling pathways involved in the development of fibrosis. The SMAD family signaling cascade plays a critical role in fibrosis and is essential for the activation of the myofibroblast phenotype, stimulation of extracellular matrix synthesis, and regulation of integrin expression [

9]. Specifically, Smad2/Smad3 phosphorylated by TGF-β translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate the transcription of fibrosis-related target genes such as MMP1, collagen I, and α-SMA [

10].

Pirfenidone, which is used in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis, has been shown to reduce fibroblast proliferation and to suppress the mRNA and protein expression levels of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)–induced α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and procollagen I (Col-I) [

11]. Studies have demonstrated that pirfenidone inhibits TGF-β, which stimulates collagen production, thereby preventing fibroblast proliferation [

12].

In addition to its antifibrotic effects, pirfenidone may cause gastrointestinal, hepatic, and skin-related adverse effects. Moreover, pirfenidone is particularly associated with drug–drug interactions [

13]. Although pirfenidone is used in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis, it remains insufficient for the treatment or suppression of this currently incurable disease, highlighting the need for novel antifibrotic agents with fewer or no adverse effects.

Plants contain secondary metabolites that have fewer or no side effects compared to synthetic compounds and are widely used in the treatment of many diseases. Many of these compounds exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Owing to these properties, medicinal plants could be considered an alternative approach for suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Previous studies have demonstrated that various plant-derived compounds contribute to the suppression of fibrosis by modulating TGF-β, SMAD2, SMAD3, α-SMA, COL1 and TNF-α which plays a critical role in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and extracellular matrix aggregation in fibrosis [

14]. Furthermore, a study conducted on human airway granulation fibroblasts showed that the TGF-β/SMAD2 signaling pathway can be inhibited by phytochemical compounds [

15].

The genus

Thymus, belonging to the Lamiaceae family, comprises approximately 214 species and is primarily distributed across North Africa, Europe, and temperate Asia region [

16].

Compounds such as thymol obtained from Thymus species are used in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries due to their antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, and antispasmodic activities [

17]. Although previous studies have reported antifibrotic roles of

Thymus species in liver and lung fibrosis, these studies are quite limited in number [

18,

19]. While the essential oils of

Thymus species contain a variety of chemical compounds, no studies have yet investigated their antifibrotic effects specifically on pulmonary fibrosis. Within this context, the present study aims to determine the effects of

Thymus syriacus essential oil, which contains significant terpenoid compounds, on the TGF-β/SMAD2 signaling pathway, as well as its role in the expression of α-SMA, collagen I, and the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α.

2. Results

2.1. Assessment of Body Weight and Lung Index Parameters

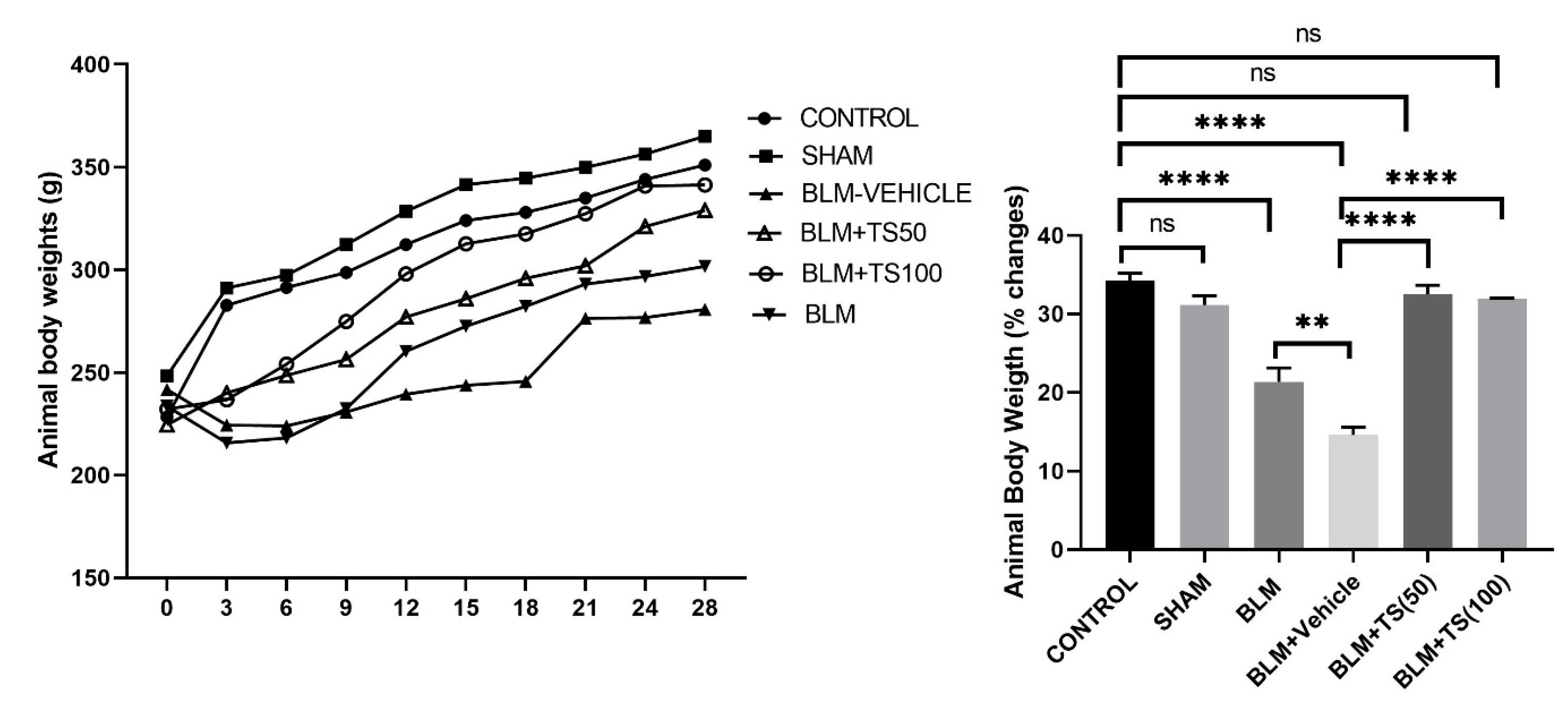

On the day of bleomycin administration, animals were weighed, and starting three days after bleomycin treatment, saline, vehicle, TS-50, and TS-100 were administered. Body weights were recorded every three days until the end of the experiment. The body weight changes and total body weight percentages of the groups were presented in

Figure 1. As shown in the figure 1, control (34.29%) and sham (31.14%) groups gained weight throughout the experimental period, and no significant difference was observed between these two groups in terms of percentage body weight change (p = 0.1839). In contrast, compared with the control group, the BLM (21.36%) and BLM+Vehicle (14.6%) groups exhibited a significantly reduced percentage of weight gain (p < 0.0001 for both groups). However, the BLM+TS50 (32.50%) and BLM + 100 (31.93%) groups showed a significantly greater increase in body weight compared with the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups.

Moreover, the percentage of body weight gain in the BLM+TS50 (32.50%) and BLM+TS100 (31.93%) groups was similar to that of the control group (p = 0.6347 and p = 0.3966, respectively).

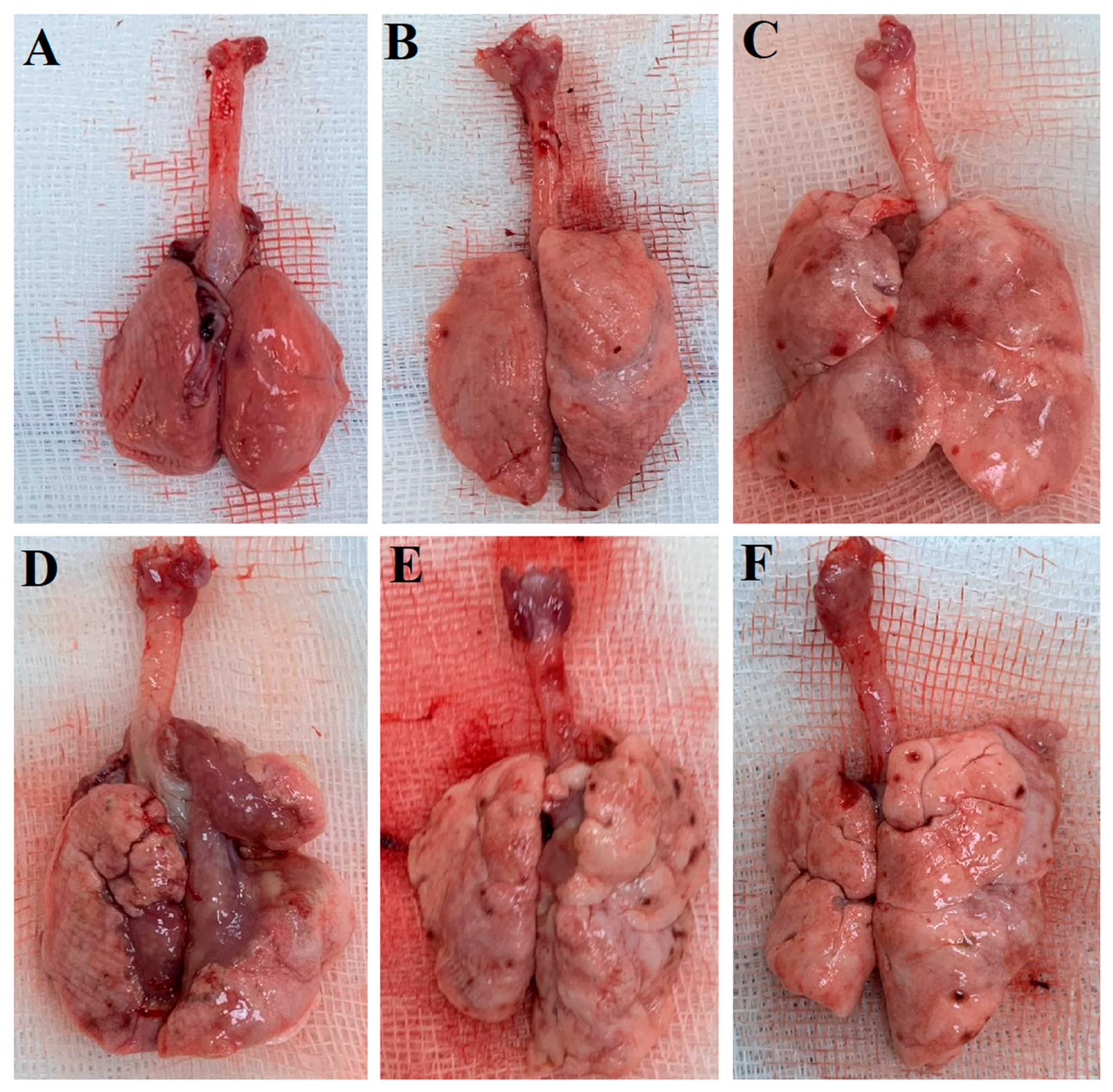

Figure 2 displays lung images of the experimental groups taken after sacrifice on day 28 of the experiment. As can be seen

Figure 2, no pathological changes are visible in the Control and SHAM groups, while fibrotic areas are apparent in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups. On the other hand, fibrotic areas are also visible in the BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100 groups; however, these are shown to be less extensive compared to the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups.

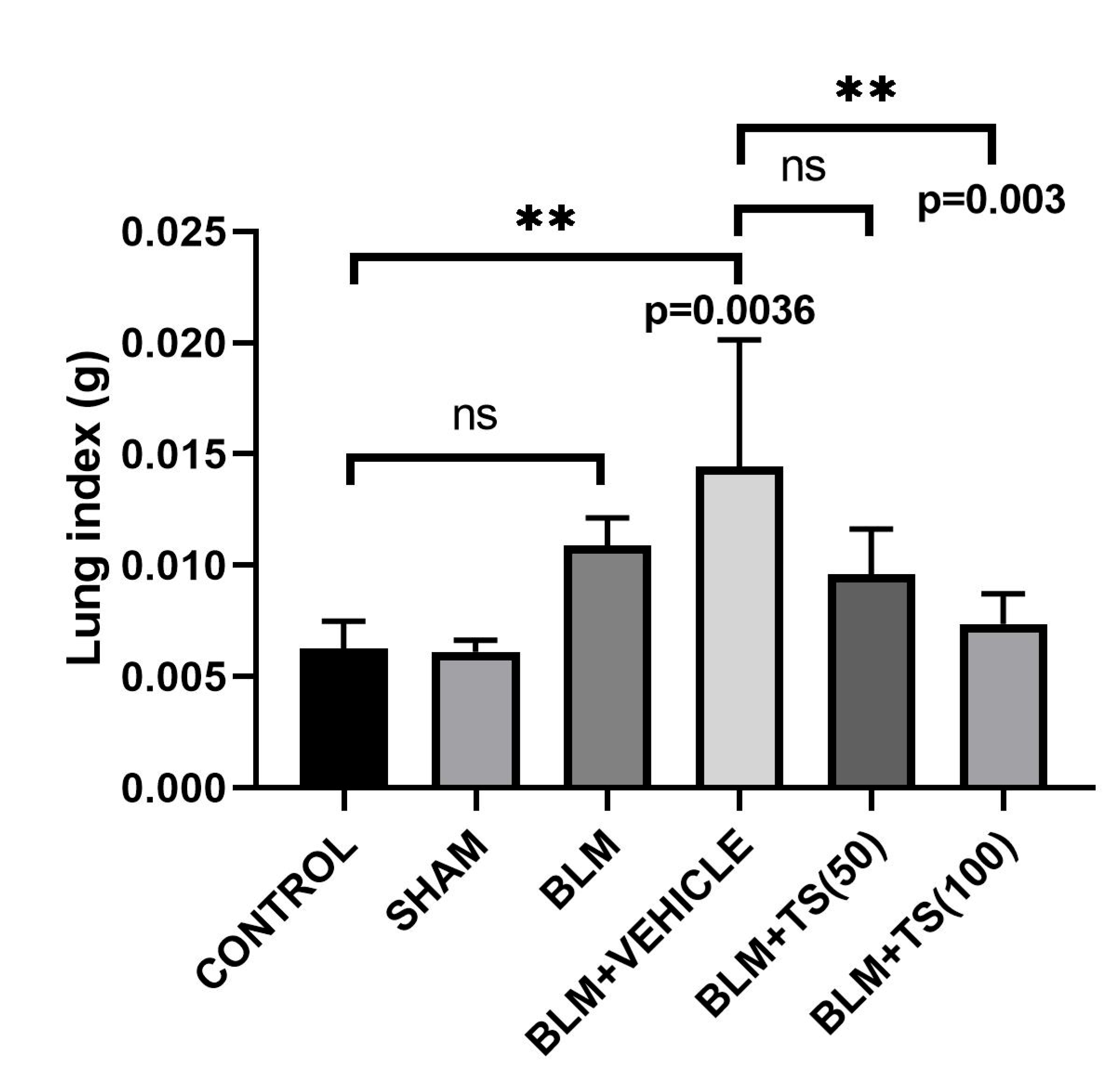

Furthermore, lung index results, obtained by calculating the ratio of lung weight to the final day body weight of the animals, were presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that the lung index score determined in the BLM and BLM + Vehicle groups is higher than that observed in the control and TS-treated groups. However, when compared with the control group, although an increase in the lung index score was observed in the BLM group, this increase was not statistically significant (p = 0.1286); in contrast, the increase observed in the BLM + Vehicle group was statistically significant (p = 0.0036). When compared with the BLM + Vehicle group, a significant decrease in the lung index score was observed in the BLM + TS100 group (p = 0.003). In contrast, although a reduction in the lung index score was calculated in the BLM + TS50 group, this decrease was not statistically significant (p = 0.0814).

2.2. Real-Time PCR Analysis of TGF-β1, SMAD-2, COL1, and α-SMA mRNA Levels in Lung Tissues

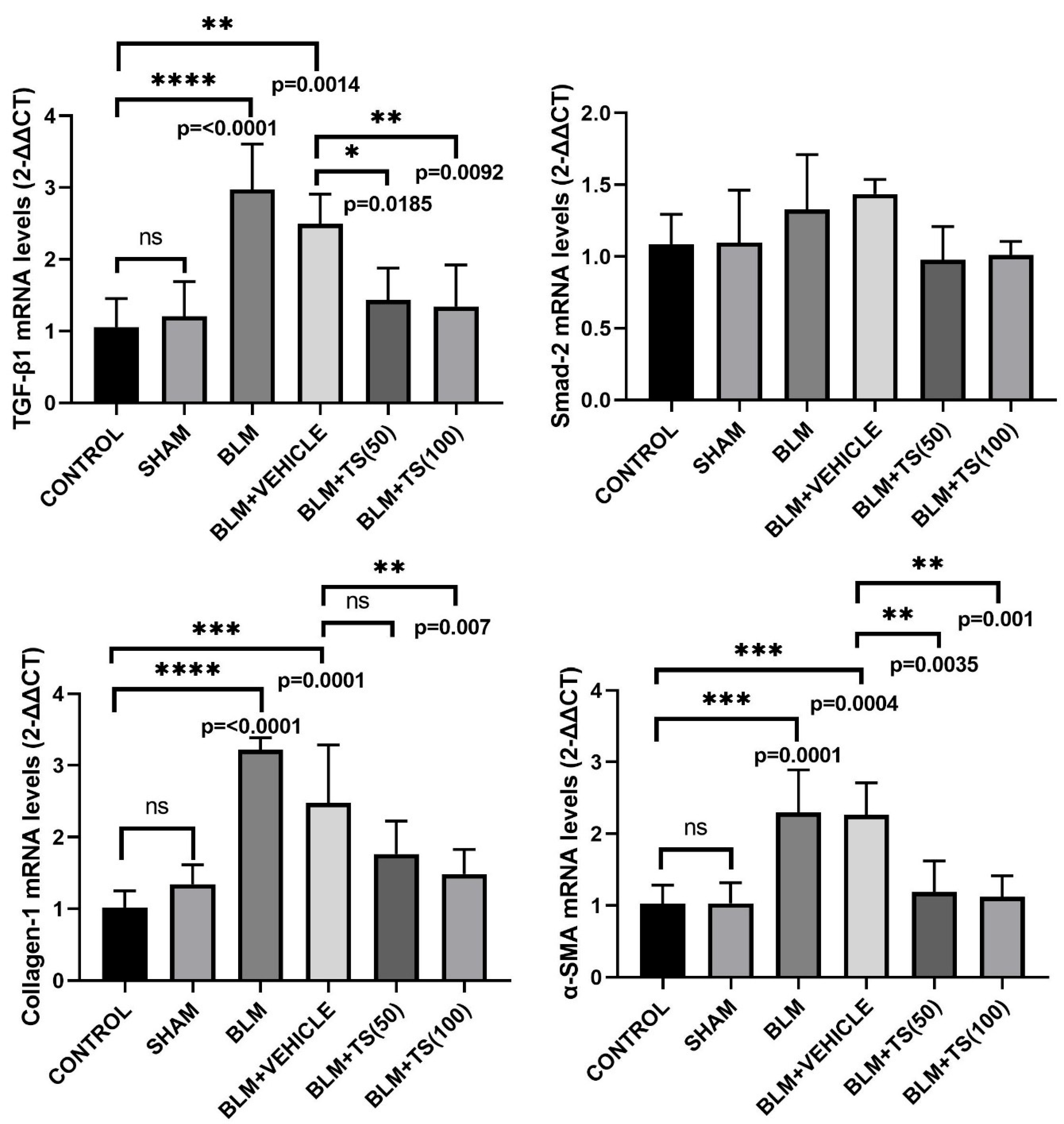

TGF-β1, SMAD-2, COL1, and α-SMA mRNA levels in lung tissues were determined using the Real-Time PCR method, and the results are presented in

Figure 4. As can be seen figure 4, TGF-β1 mRNA levels did not change in the Control and SHAM groups. However, TGF-β1 mRNA levels were significantly elevated in the BLM (2.97-fold) and BLM+Vehicle (2.48-fold) groups compared to the Control group (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0014, respectively). Furthermore, when compared to the BLM+Vehicle group, TGF-β1 levels were found to be significantly decreased in the BLM+TS50 (0.57-fold) and BLM+TS100 (0.54-fold) groups (p = 0.0185 and p = 0.0092, respectively). In addition, SMAD-2 mRNA levels in lung tissues were increased in the BLM and BLM + Vehicle groups compared with the Control and Sham groups, although this increase was not statistically significant (p> 0.05). Furthermore, compared with the BLM+Vehicle group, SMAD-2 levels were reduced in the BLM + TS50 and BLM + TS100 groups, but this reduction was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

COL1 mRNA levels were found to be significantly increased in the BLM (3.15-fold) and BLM+Vehicle (2.42-fold) groups compared to the control group (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0001, respectively). When the BLM+Vehicle and BLM+TS50 groups were compared, a decrease in COL1 levels was observed; however, this decrease was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). On the other hand, COL1 mRNA levels in the BLM+TS100 group were found to be significantly decreased compared to the BLM+Vehicle group (0.59-fold, p = 0.007).

Furthermore, α-SMA mRNA levels were observed to be increased in the BLM (2.23-fold) and BLM+Vehicle (2.2-fold) groups compared to the control group (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.0004, respectively). However, compared to the BLM+Vehicle group, α-SMA mRNA levels were significantly reduced in the BLM+TS50 (0.52-fold) and BLM+TS100 (0.49-fold) groups (p = 0.0035 and p = 0.001, respectively).

2.3. Determination of TGF-β1, SMAD2, COL1, and α-SMA Protein Levels

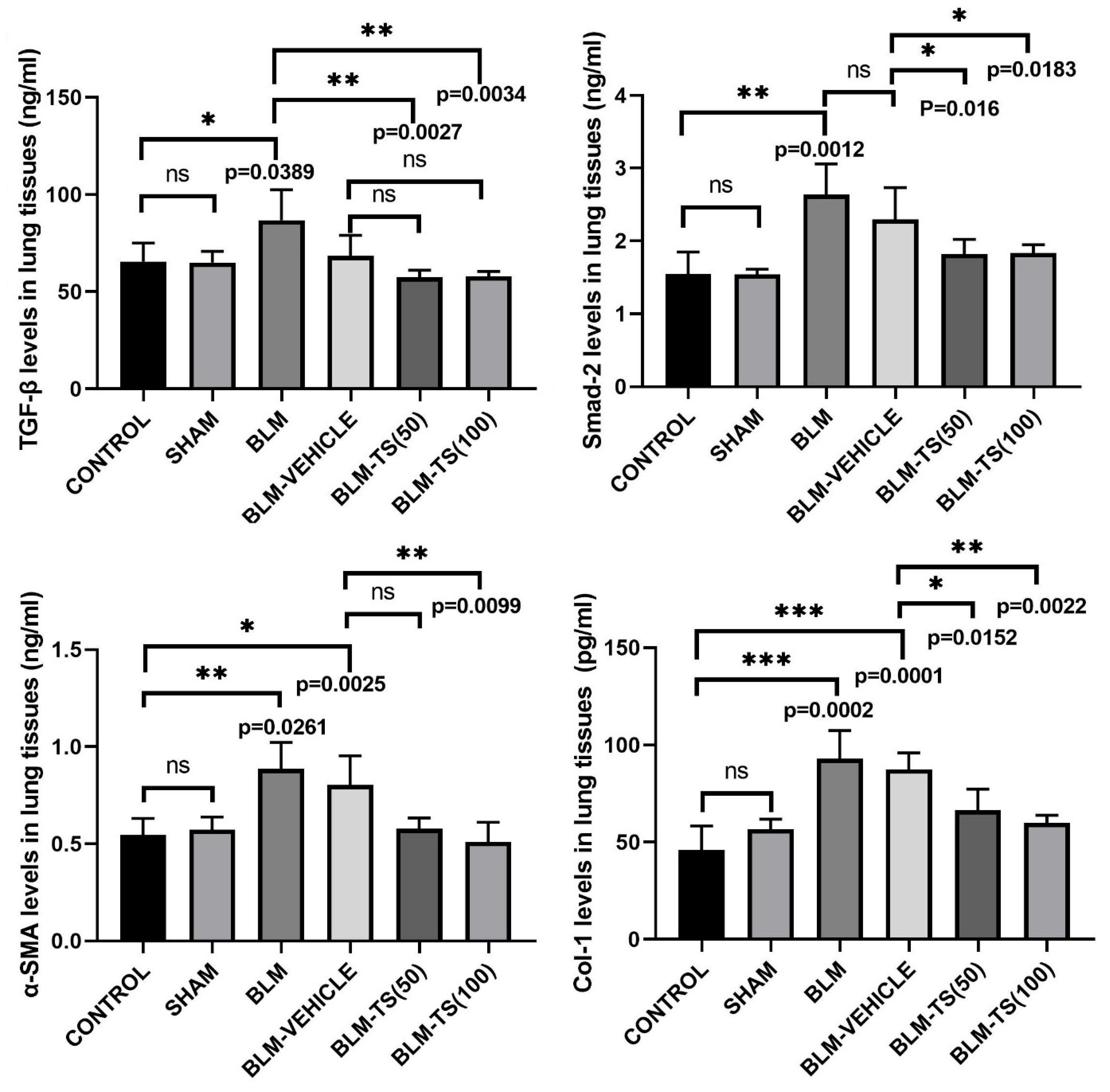

The total protein amounts in the supernatants obtained from lung tissues were determined using the BCA assay, and protein levels were normalized prior to use in the experiments. Subsequently, TGF-β, Smad-2, α-SMA, and Col-1 levels in the lung tissues were compared among the different experimental groups, and the results were presented in Figure 5. No statistically significant difference was detected in TGF-β, Smad-2, α-SMA, and Col-1 levels between the Control and Sham groups. In BLM group, TGF-β levels in lung tissues were found to be significantly increased compared to the Control and Sham groups (p = 0.0389). Similarly, Smad-2, α-SMA, and Col-1 levels were also significantly increased in the BLM group (p = 0.0012, p = 0.0261, and p = 0.0002, respectively), indicating that bleomycin induces a strong fibrotic response.

In the groups treated with TS (BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100), a distinct reduction was observed in the levels of all fibrotic markers compared to the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups. Specifically, TGF-β levels decreased significantly with TS treatment (p = 0.0027 and p = 0.0034), and a similar reduction was detected in Smad-2 levels (p = 0.016 and p = 0.0183). Furthermore, α-SMA and Col-1 levels were found to be significantly decreased following TS administration (p = 0.0099 for α-SMA; p = 0.0152 and p = 0.0022 for Col-1), and these values were determined to be similar to those in the Control/Sham groups.

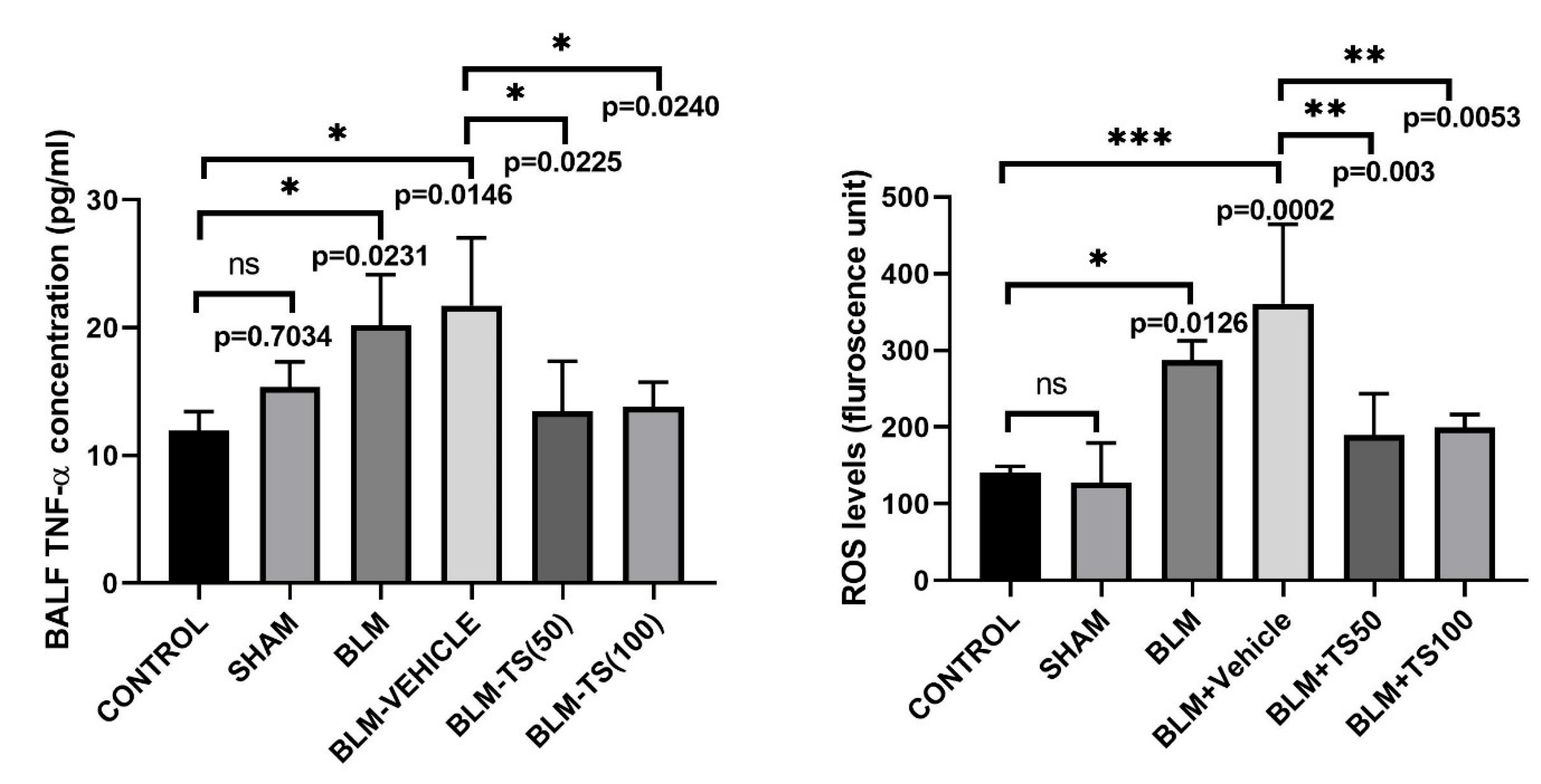

2.4. Determination of TNF-α Levels in BALF

Figure 6 shows the BALF TNF-α concentrations in the Control, SHAM, BLM, and TS groups. No statistically significant difference in TNF-α levels was detected between the Control and Sham groups (p = 0.7034). On the other hand, in the group administered BLM, BALF TNF-α levels were significantly elevated compared to the Control and Sham groups (p = 0.0231 and p = 0.0146, respectively). TNF-α levels in the BLM+Vehicle group were similarly high compared to the BLM group, indicating that vehicle administration had no additional effect on BLM-induced inflammation. In contrast, in the BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100 groups, BALF TNF-α levels were significantly reduced compared to both the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups (p = 0.0225 and p = 0.0240, respectively).

2.5. Determination of ROS Levels in Lung Tissue

ROS levels in lung tissue homogenates were determined fluorometrically using the DCFH-DA method, and the results are expressed in fluorescence units (

Figure 6). As seen in

Figure 6, ROS levels were significantly increased in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups compared to the Control group (p = 0.0126 and p = 0.0002, respectively). When the BLM+Vehicle group was compared to the TS50 and TS100 groups, ROS levels were found to be significantly decreased in both groups (p = 0.003 and p = 0.0053, respectively). However, no significant difference was detected between BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100 groups (p = 0.9998).

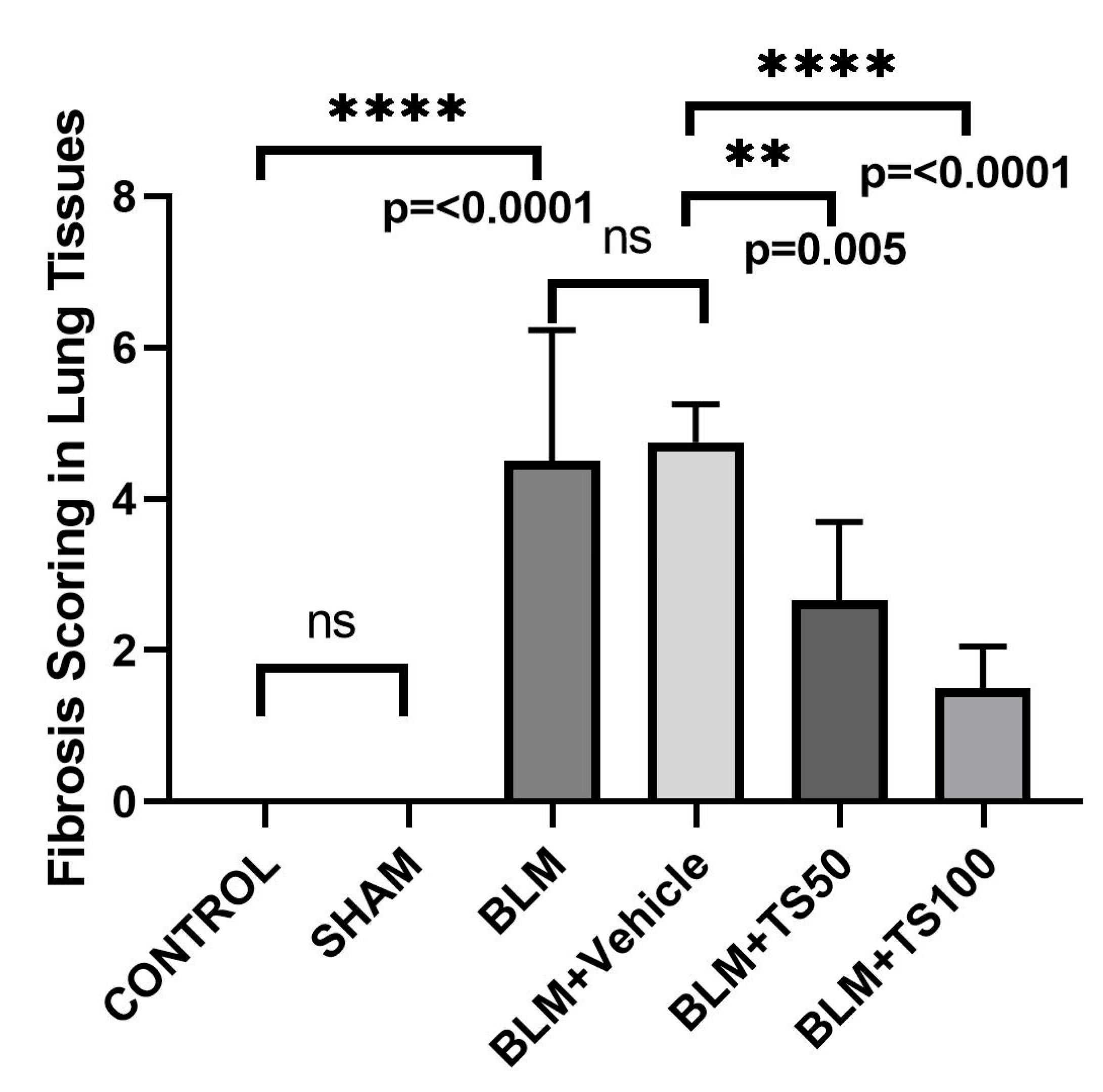

2.6. Histopathological Evaluation and Ashcroft Scoring Results

Lung tissue samples were histopathologically examined using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Masson's trichrome staining methods, and the degree of fibrosis was assessed using the Ashcroft scoring system (

Table 2) [

20]. The fibrosis scoring results were presented in

Figure 7. Compared with the control group, the fibrosis score

(severity of lung fibrosis) was significantly increased in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups (p < 0.0001 for both). In contrast, fibrosis scores were significantly reduced in the BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100 groups compared to the BLM+Vehicle group (p = 0.005 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

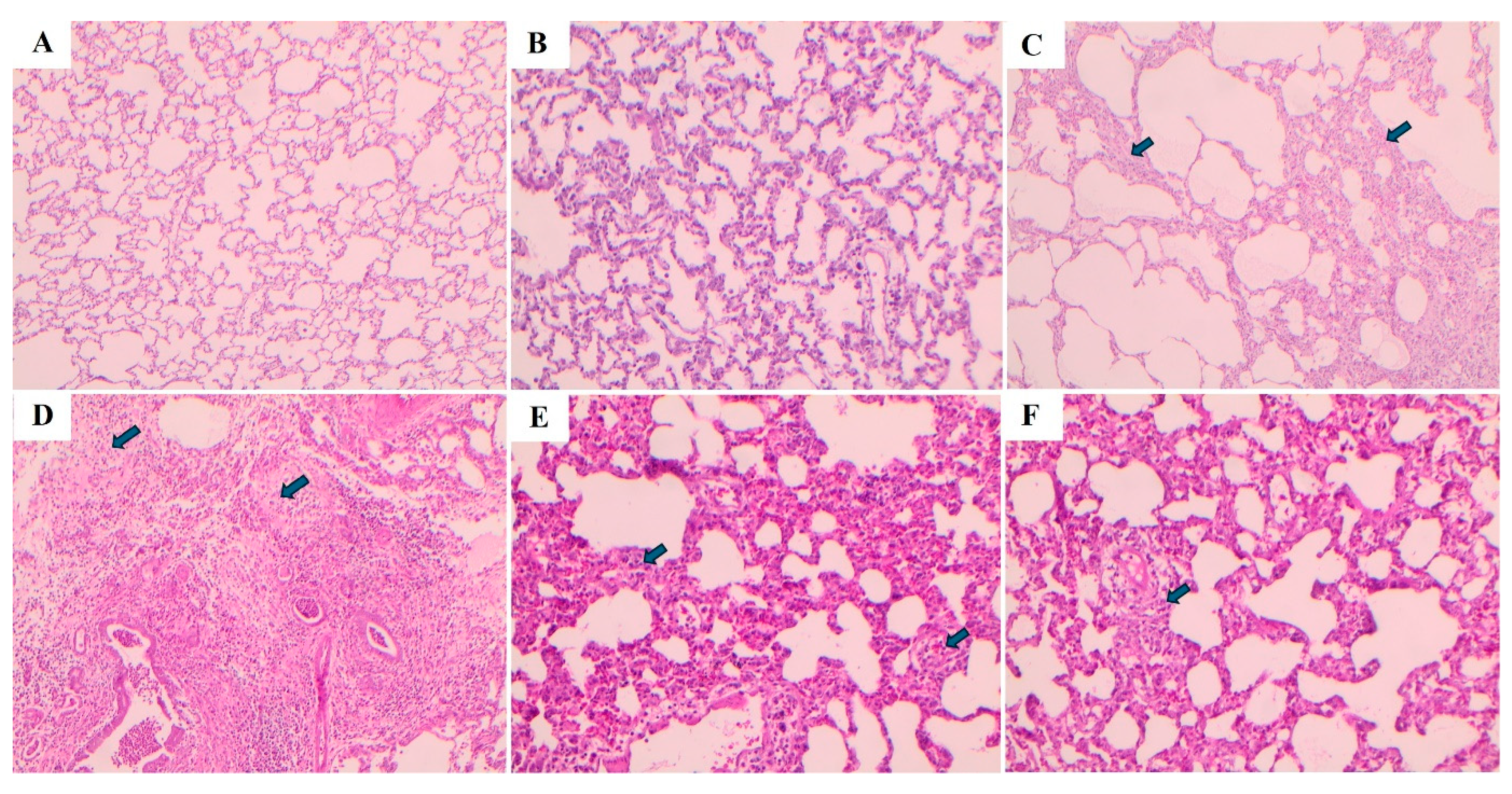

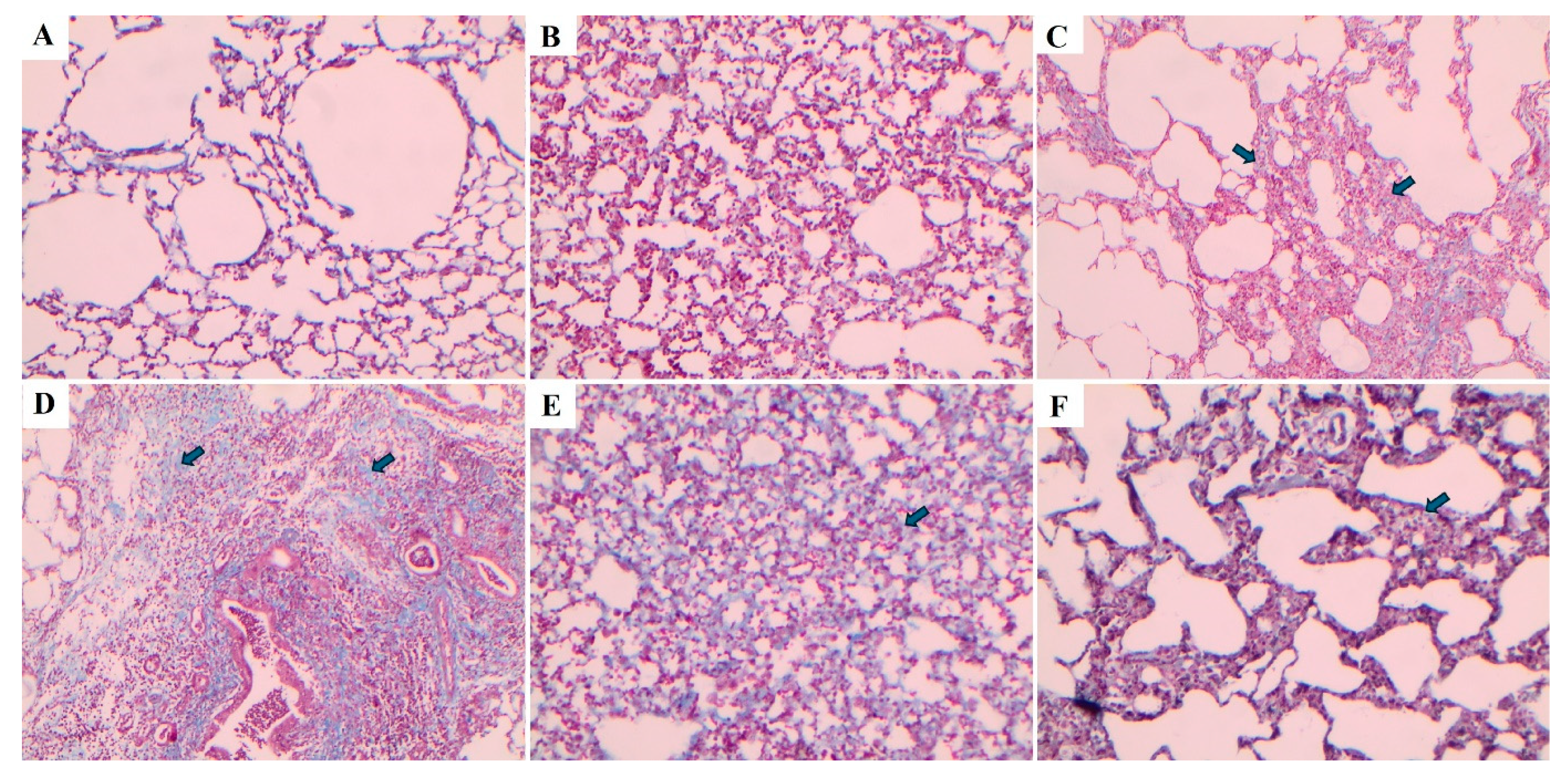

Lung tissues were stained using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Masson's trichrome staining methods, and the images are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively. In the Control and Sham groups, the Ashcroft score was determined as “0”. H&E staining revealed no fibrotic burden in the alveolar septa, and no septal thickening, cellular inflammation, or fibrotic changes were observed. The normal alveolar architecture of the lung parenchyma was fully preserved. Similarly, Masson's trichrome staining showed no increase in connective tissue, indicating that the lung tissue maintained a completely normal histological structure.

In the BLM group, the Ashcroft score was evaluated as “4”. H&E staining revealed variable fibrotic changes between areas in the alveolar septa. Limited, small foci of fibrotic masses were observed in less than 10% of the microscopic fields of the lung tissue. Masson's trichrome staining showed a marked increase in connective tissue, consistent with the presence of these limited fibrotic area. In the BLM + Vehicle group, the Ashcroft score was determined as “5”. H&E staining revealed marked thickening of the alveolar septa and dense fibrotic bands. Large, contiguous fibrotic masses were observed in 10–50% of the microscopic fields. Despite substantial damage to the parenchymal structure, the overall architecture of the lung was preserved. Masson's trichrome staining showed a pronounced increase in connective tissue, consistent with an advanced fibrotic pattern.

In the BLM + TS50 group, the Ashcroft score was evaluated as “3”. H&E staining revealed septal thickening and contiguous fibrotic bands throughout the microscopic fields, with septal thickness reaching approximately three times that of normal. Alveoli were mildly enlarged and sparsely distributed, but no prominent fibrotic masses were observed. Masson's trichrome staining showed a mild increase in connective tissue. In the BLM + TS100 group, the Ashcroft score was determined as “2”. H&E staining demonstrated marked thickening of the alveolar septa (approximately three-fold) with nodular, non-contiguous fibrotic areas. Although alveolar spaces were slightly enlarged and sparse, no significant fibrotic masses were detected. Masson's trichrome staining revealed a very mild increase in connective tissue.

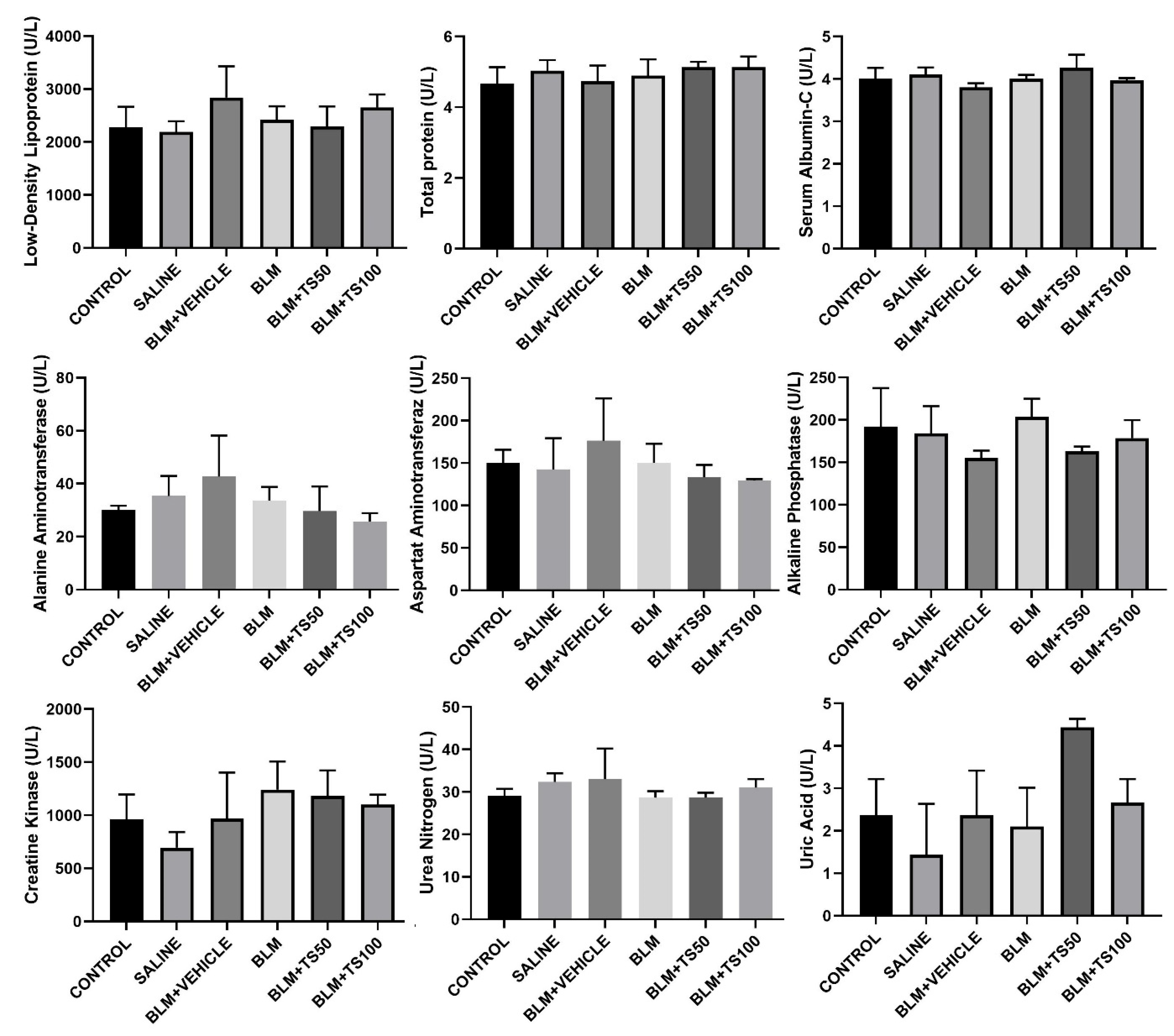

2.7. Evaluation of Serum Biochemical Parameters

Serum biochemical parameters were analyzed to assess potential systemic toxicity and organ functions in the experimental groups, and the results are presented in Figure 10. The parameters examined include low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total protein, serum albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferaz (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), creatine kinase (CK), urea nitrogen, and uric acid. LDL levels showed a similar distribution among the groups, and it was observed that BLM and TS applications did not lead to a significant change in the lipid profile. No significant differences were detected in total protein and serum albumin levels among the control, saline, BLM, and BLM+TS groups. This finding suggests that the treatments did not adversely affect general protein metabolism and nutritional status.

When the levels of liver function indicators ALT, AST, and ALP were evaluated, a slight increasing trend was observed in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups; however, these increases were not at a level indicative of marked hepatotoxicity. In the TS-treated groups (BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100), ALT and AST levels tended to be lower compared to the BLM group, while ALP levels were observed to be close to those of the control group. No significant differences were observed among the groups in creatine kinase levels, which reflect cardiac damage. Kidney function indicators, urea nitrogen and uric acid levels, remained within physiological limits in all groups. Specifically, in the TS-treated groups, urea nitrogen levels were found to be similar to those of the control group, and no clinically significant increase was observed in uric acid levels.

2.8. Evaluation of GC–MS Analysis

GC–MS analysis identified a total of 57 compounds in the TS essential oil, with the identified compounds accounting for 97.15% of the total oil composition (Table 3). As can be seen, the essential oil was found to be rich in monoterpenes (2.8%), oxygenated monoterpenes (78.6%), and sesquiterpenes (7.5%). The most dominant compound was carvacrol, constituting more than half of the total oil components at 53.36%. The second most abundant compound was identified as carvone (15.59%). Other major components included endo-borneol (6.85%) and (+)-2-borneanone (1.87%). Within the sesquiterpene category, compounds such as caryophyllene (1.24%), caryophyllene oxide (1.36%), germacrene-D (0.14%), and δ-cadinene (0.42%) were detected. Notably, globulol (0.37%), isospathulenol (0.40%), and α-/τ-cadinol derivatives were prominent as oxygenated sesquiterpenes. Aliphatic compounds, including n-hexadecanoic acid (0.18%) and eicosane (1.72%), were also detected, albeit at lower concentrations.

3. Discussion

Bleomycin is an agent used in cancer treatment; however, as a side effect, it also triggers pulmonary fibrosis and affects approximately 10% of patients taking the drug[

21].

Fibrosis is characterized by excessive growth, hardening, and/or scar formation in various tissues. It is attributed to the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix components, primarily collagen, and is the end product of chronic inflammatory reactions[

22].

In the BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis model, key factors include oxidative stress and cytokines. Cytokines such as TNF-α and growth factors such as TGF-β play a role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis in association with oxidative stress. TNF-α exacerbates inflammation and supports the fibrotic process due to oxidative stress. Furthermore, fibrosis is characterized by increased TGF-β1 expression [

23,

24,

25]

and TGF-β1 is involved in fibroblast activation, myofibroblast transformation, and the accumulation of collagen and extracellular matrix [

26,

27].

The activation of TGF-β1 triggers the SMAD signaling pathway[

28]. Activated SMAD2/SMAD3 molecules are translocated into the nucleus, where they stimulate fibrosis-related transcription factors and activate genes such as collagen type 1 and α-SMA in the fibrotic mechanism[

29].

The development of pulmonary fibrosis is a critical stage associated with collagen accumulation resulting from the activation of fibroblasts and their differentiation into myofibroblasts[

30].

Excessive collagen accumulation is regarded as a source of severe disruption in the normal histological structure of lung tissue, such as thickening of the alveolar walls. It is accompanied by the loss of alveolar structures in the lung and thickening of the alveolar walls due to follicular accumulations of lymphocytes in the interstitial space. The number of agents used clinically for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis is limited. Drugs such as pirfenidone and nintedanib are used in the treatment of the disease, but these drugs can only slow its progression[

31,

32].

Indeed, the identification of new and non-toxic compounds with antifibrotic effects in this field is of great importance.

Medicinal plants possess a wide range of biological activities, including antioxidant[

33], anticancer[

34], anti-inflammatory[

35], antidiabetic, antimutagenic effects[

36], among others. Furthermore, plants and their isolated compounds have been reported to exhibit significant antifibrotic effects in experimental models of pulmonary fibrosis[

21].

Previous studies have reported that Thymus species may play a role in suppressing pulmonary and liver fibrosis[

18,

19].

the discovery of natural and easily accessible agents with no side effects for the suppression or treatment of pulmonary fibrosis is important, and the antifibrotic effects of Thymus species require more detailed investigation. In this context, our study molecularly investigated the antifibrotic effect of

T. syriacus essential oil in a bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model. Following daily administration of TS essential oil at concentrations of 50 and 100 mg/ml for 28 days, animal body weights were found to be higher compared to the BLM and BLM+vehicle groups. Conversely, only in the BLM and BLM+vehicle groups was a decrease in animal body weight observed relative to the other groups. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have similarly demonstrated that animal body weights decrease in BLM-treated groups and increase with the use of antifibrotic agents[

37].

Furthermore, our study determined that lung index scores increased in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups, whereas they decreased in the TS-treated groups. The increase in lung index scores in BLM groups and their reduction in treatment groups have also been demonstrated in previous studies[

37].

Among the key markers of fibrosis, cytokines such as TNF-alpha and Interleukin-1β play a role[

38].

TNF-α binds to TNFR1 receptors, activating signaling pathways that lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), hydroxyl radical (HO•), and nitric oxide (NO), cause oxidative stress, resulting in tissue damage. The interaction between oxidative stress and TGF-β plays a critical role in inducing fibrosis. By increasing ROS production, TGF-β triggers oxidative stress[

3]. In present study, it has been demonstrated that TNF-α, a marker of bleomycin-induced lung inflammation, was increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) isolated from the lungs of the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups. Furthermore, the rise in TNF-α levels was suppressed in a concentration-dependent manner following treatment with TS essential oil. Additionally, ROS levels were elevated in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle group tissues, while they were reduced in the BLM+TS50 and BLM+TS100 groups. In this context, it can be stated that TS administration significantly suppressed the inflammatory response, indicating that TS may possess anti-inflammatory effects in bleomycin-induced lung inflammation. Studies conducted with different species of the Lamiaceae family have reported that TNF-α levels are suppressed in pulmonary fibrosis[

39].

Based on our literature review, no previous studies have been found demonstrating the effects of Thymus species on TNF-α and ROS levels in lung tissues or BALF.

In addition, it has been demonstrated that various plants belonging to Lamiaceae species play a role in suppressing organ fibrosis triggered by an increase in TGF-β-induced SMAD2 and α-SMA levels[

39]. In this context, our study showed that in groups treated with TS essential oil, the expression of α-SMA and Collagen 1 was suppressed at both the mRNA and protein levels, which is associated with the inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad2 signaling pathway. The reduction in TGF-β/Smad2, α-SMA, and collagen 1 levels at the mRNA and protein levels suggests that TS essential oil significantly attenuates the fibrotic response and indicates that TS may be a potential antifibrotic agent against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis.

In this study, it was demonstrated that bleomycin administration caused significant fibrotic changes in lung tissue and that TS essential oil application reduced the severity of fibrosis, consistent with Ashcroft scores and histopathological findings. Following histopathological examination, fibrotic alterations such as thickening of alveolar septa, adjacent fibrotic bands, and expansion of alveoli were observed in the BLM and BLM+Vehicle groups, whereas these fibrotic changes decreased with TS essential oil treatment. These findings support the conclusion that TS possesses significant potential in suppressing bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Moreover, blood samples taken from all groups were biochemically evaluated for kidney, liver, and cardiac toxicity. Among the examined parameters including low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total protein, serum albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), creatine kinase (CK), urea nitrogen, and uric acid—no significant changes were observed between the control, BLM, and treatment groups. Overall, these findings indicate that bleomycin and TS applications do not cause serious toxicity in systemic biochemical parameters. It was concluded that TS treatment exhibits a safe profile in terms of liver, kidney, and metabolic functions in the bleomycin-induced lung injury model, and that the observed therapeutic effects are independent of systemic side effects.

Finally, in our study, the volatile oil components of

T. syriacus were identified using the GC–MS method. The major constituents of the essential oil were determined to be carvacrol and carvone, respectively, with carvacrol accounting for more than half of the total oil content. Previous studies have similarly demonstrated that carvacrol is the principal component of

T. syriacus essential oil[

40,

41]. Carvacrol has been reported to exhibit antioxidant properties by suppressing malondialdehyde (MDA) production and increasing glutathione levels, as well as anti-inflammatory effects through modulation of inflammatory markers such as TNF-α and IL-6[

42]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that carvacrol plays a role in attenuating renal and hepatic fibrosis through inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway[

43,

44]. Finally, a reduction in inflammation and fibrotic lesions has been shown in a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model following carvacrol treatment[

45]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the antifibrotic effects observed in our study may be largely attributed to the high carvacrol content of

T. syriacus essential oil.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection, Drying, and Essential Oil Extraction of Thymus syriacus

Thymus syriacus was collected on May 30, 2024, from the Gaziantep-Nizip region, Turkey. The species was taxonomically identified by Associate Professor Dr. Mustafa Pehlivan from the Department of Biology, Gaziantep University, and was assigned an individual herbarium number (MPH2022-1). The aerial parts of the collected plants were washed and subsequently air-dried in a dark, well-ventilated environment. For essential oil extraction, the dried plant material was ground into a fine powder and subjected to hydrodistillation using a Clevenger apparatus for 3 hours, yielding 2.09% (w/w) essential oil. The obtained oil was stored at +4 °C until further experimental use.

4.2. Pulmonary Fibrosis Model

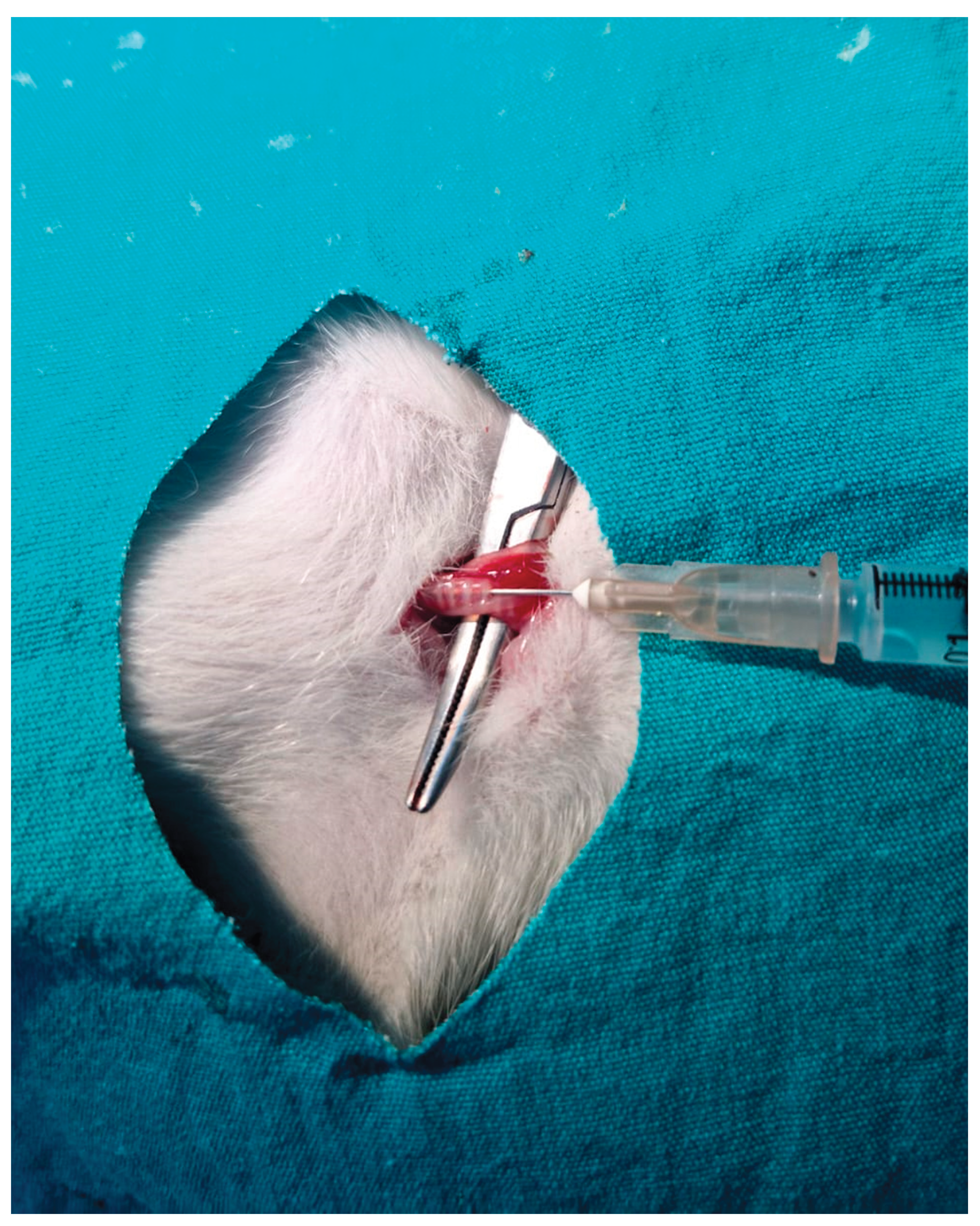

This study was approved by the Adıyaman University Experimental Animals Ethics Committee (protocol number: 2024/044). Male Wistar albino rats, aged 8-12 weeks and bred at the Adıyaman University Experimental Animals Center, were used in the experiments. The animals were maintained under a controlled 12-hour light/dark cycle and provided with ad libitum access to drinking water and standard rat chow

Pulmonary fibrosis was induced in rats via intratracheal administration of bleomycin. Briefly, the pulmonary fibrosis model was established by administering bleomycin at a dose of 5 mg/kg, dissolved in 100 µL of sterile saline, directly into the trachea. Rats were anesthetized, and a small midline incision was made at the cervical region to access the trachea, after which the solution was delivered using an insulin syringe (

Figure 11).

Experimental 1. This group serves as the untreated control, in which no interventions were performed.

Group 2: The sham group consisted of rats that underwent surgical exposure of the trachea only and received 0.1 mL of saline (the bleomycin vehicle).

Group 3: the bleomycin group, pulmonary fibrosis was induced by surgically exposing the trachea and administering bleomycin at a dose of 5 mg/kg.

Group 4: the bleomycin + vehicle group, rats that received bleomycin were additionally administered 0.5 mL of sunflower oil, which served as the vehicle for the essential oils.

Group 5: the bleomycin + Thymus syriacus essential oil group (50 mg/mL), the essential oil was administered via gavage starting on 3 days after bleomycin administration.

Group 6: the bleomycin + Thymus syriacus essential oil group (100 mg/mL), the essential oil was administered via gavage starting on 3 days after bleomycin administration.

On day 28 of the experiment, all animals were sacrificed under ketamine and xylazine anesthesia, and lung tissues were harvested. The thorax was opened via a midline incision under anesthesia, and the trachea was cannulated using a plastic catheter attached to a 10 mL syringe. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected by instilling 5 mL of sterile saline into the lungs five times, with gentle massage to facilitate fluid recovery. The BALF was then centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C to obtain the supernatant for biochemical analyses.

For histopathological examinations, one-third of the lung tissue was fixed in 10% formalin. The remaining tissue samples were stored at −80 °C until further molecular analyses. In addition, blood samples were collected for biochemical analyses and stored at +4 °C.

4.3. Determination of Animal Body Weights

The body weight of the animals was assessed at the beginning and the end of the experiment. The percentage of body weight gain for each group was calculated using the following equation:

where BW is the percentage of body weight gain

, fBW is the final body weight at the end of the experimental period, and iBW is the initial body weight at the beginning of the experimental period.

4.4. Determination of the Lung Index

After the sacrifice of the rats, the lungs, including the trachea, were completely excised and weighed at the end of the experiment to determine the lung-to-body weight ratio. The lung index was calculated using the following formula:

4.5. Determination of Total Protein Levels

Lung tissue samples weighing 100 mg each were homogenized in 1/10 (w/v) cold saline using a homogenizer. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 10000 g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. Total protein levels in the supernatant were determined using a BCA-ELISA kit. The total protein concentrations in the lung samples were measured according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

4.6. Evaluation of the Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine TNF-α in BALF

The levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in the BALF were quantified using a commercial rat-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Finetest, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions

4.7. Determination of TGF-β, SMAD2, Col1, and α-SMA Levels

The levels of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 2 (SMAD2), collagen type I (COL1), and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in lung tissue homogenates were quantified using commercial rat-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (FineTest, China), following the respective manufacturer's protocols.

4.8. RNA Isolation from Lung Tissues and Preparation of cDNA Samples

The lung tissues were placed into sterile tubes and homogenized using a homogenizer. RNA was isolated from the tissues, and the extracted RNA was subsequently reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit according to manufacturer's protocols. . cDNA synthesis reactions were performed for real-time PCR. The forward primer sequences for TGF-β, SMAD2, COL1, and α-SMA are listed in

Table 1.

4.9. Analysis of Gene Expression Using Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Gene expression analyses were performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on a QIAGEN Rotor-Gene Q Real-Time PCR system (QIAGEN Sample & Assay Technologies, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

4.9. Assesment of Histopathological of Lung Tissues

Lung specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 7 days. Following fixation, the specimens were dehydrated through a graded alcohol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 7 μm using a manual microtome (RM 2125; Leica Instruments, Nussloch, Germany). Sections were mounted on slides, deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then stained using a Masson’s trichrome kit (Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy). For histopathological evaluation, sections were photographed at 40× magnification using a light microscope (Axiocam ERc5s; Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) equipped with a digital camera.

4.10. Biochemical Analyses of Blood Samples

For biochemical analyses, blood samples collected in EDTA-containing tubes were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate the serum. The serum was then aliquoted and stored at -20°C until analysis. Clinical biochemistry parameters were measured using an automated analyzer. The liver profile included total protein, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST); the renal profile included urea and uric acid; and the cardiac profile included creatinine kinase (CK).

4.11. Determination of the Phytochemical Content of Thymus syriacus Essential Oil

The chemical composition of the essential oil obtained from Thymus syriacus was determined by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The analysis was performed using an Agilent Technologies 6890 N gas chromatograph equipped with an HP-5 MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness; 5% phenyl methyl siloxane) coupled to an Agilent 5972 mass-selective detector. Electron-ionization (EI) mode was used at 70 eV. Helium was employed as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injector and detector temperatures were set at 220 °C and 290 °C, respectively. The following temperature program was applied to achieve optimal separation: the column temperature was initially held at 50 °C for 2 min, then increased at a rate of 3 °C/min to 250 °C and held for 5 min. Samples were prepared by diluting the essential oil in acetone (1:100, v/v), and 1.0 µL of each diluted sample was injected in splitless mode.

4.12. Statistical Analyses

Statistical comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the antifibrotic properties of T. syriacus (TS) essential oil on the TGF-β1/SMAD2 signaling pathway and its associated fibrotic markers, collagen type I (Col1) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), were investigated in a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model using molecular, biochemical, and histopathological approaches. The results demonstrated that TS essential oil suppresses the TGF-β1/SMAD2 pathway, targets Col1 and α-SMA expression, and consequently inhibits the mechanisms underlying fibrotic formation in lung tissue. In addition, TS administration was shown to exert no toxic effects on vital organs such as the heart, liver, and kidneys.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported the effects of TS on pulmonary fibrotic signaling pathways; therefore, the findings of the present study may represent the first report in this field. Overall, our in vivo results provide evidence that TS essential oil may serve as a potential therapeutic agent by exerting anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, and these findings may contribute to and guide future research in this area.

Nevertheless, this study has some of limitations. These include the lack of protein-level validation of the tested markers using Western blot analysis, the absence of tissue malondialdehyde (MDA) level measurements, and the lack of a positive control treatment such as pirfenidone. Therefore, future studies are recommended to address these limitations. Moreover, while the present study focused solely on the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway, it is suggested that other fibrosis-related mechanisms, particularly the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, should also be investigated following TS essential oil treatment and compared with the TGF-β/SMAD pathway to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its antifibrotic mechanisms

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

P.A. and P.Y. established the experimental animal model and performed molecular tests; O.Y. designed and conducted the research and wrote the manuscript; M.D. analyzed the data and contributed to manuscript writing; M.S. analyzed the pathological data; M.P. performed plant extraction and content analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Gaziantep University Scientific Research Projects Center, grant number FEF.DT.25.10.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Adıyaman University (protocol code 2024-044 and 07.11.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TGF-β |

Transforming Growth Factor beta |

| Col-1 |

Collagen type I |

| α-SMA |

Alpha–Smooth Muscle Actin |

| Smad |

SMAD family signaling proteins |

| GC-MS |

Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| EDTA |

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| BALF |

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid |

| BCA |

Bicinchoninic Acid |

| MMP |

Matrix Metalloproteinase |

References

- King, T.E.; Pardo, A.; Selman, M. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lancet 2011, 378, 1949–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, N.; Tager, A.M. Fibrosis of Two: Epithelial Cell-Fibroblast Interactions in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Marawan, M.E.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Fibrosis: Types, Effects, Markers, Mechanisms for Disease Progression, and Its Relation with Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, T.H.; Mendez, M.; Choi, K.; Subbotina, N.; Courey, A.; Cunningham, A.; Dave, A.; Engelhardt, J.F.; Liu, X.; White, E.S.; et al. Targeted Injury of Type II Alveolar Epithelial Cells Induces Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, M.; Hagood, J.S.; Velazquez-Cruz, R.; Ruiz, V.; Garcia-De-Alba, C.; Rangel-Escareño, C.; Urrea, F.; Becerril, C.; Montaño, M.; Garcia-Trejo, S.; et al. Cigarette Smoke Enhances the Expression of Profibrotic Molecules in Alveolar Epithelial Cells. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; Tonelli, R.; Murray, M.; Samarelli, A.V.; Spagnolo, P. Environmental Causes of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, S.C.; Kim, D.S.; Kondoh, Y.; Chen, E.; Lee, J.S.; Song, J.W.; Huh, J.W.; Taniguchi, H.; Chiu, C.; Boushey, H.; et al. Viral Infection in Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. 2012, 183, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama Amin, B.J.; Kakamad, F.H.; Ahmed, G.S.; Ahmed, S.F.; Abdulla, B.A.; mohammed, S.H.; Mikael, T.M.; Salih, R.Q.; Ali, R. k.; Salh, A.M.; et al. Post COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis; a Meta-Analysis Study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 77, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kage, H.; Borok, Z. EMT and Interstitial Lung Disease: A Mysterious Relationship. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2012, 18, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Cui, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Shang, Z.; Huang, L. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of TGF-β Inhibitors for Liver Fibrosis: Targeting Multiple Signaling Pathways. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2025, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, E.; Gili, E.; Fagone, E.; Fruciano, M.; Iemmolo, M.; Vancheri, C. Effect of Pirfenidone on Proliferation, TGF-β-Induced Myofibroblast Differentiation and Fibrogenic Activity of Primary Human Lung Fibroblasts. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 58, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, C.J.; Ruhrmund, D.W.; Pan, L.; Seiwert, S.D.; Kossen, K. Antifibrotic Activities of Pirfenidone in Animal Models. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2011, 20, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, L.H.; de Andrade, J.A.; Zibrak, J.D.; Padilla, M.L.; Albera, C.; Nathan, S.D.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Stauffer, J.L.; Kirchgaessler, K.U.; Costabel, U. Pirfenidone Safety and Adverse Event Management in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, P. dos S.; Fan, D.; Murphy, E.A.; Carver, W.E. Potential of Plant-Derived Compounds in Preventing and Reversing Organ Fibrosis and the Underlying Mechanisms. Cells 2024, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Lin, X.P.; Zhang, J.M.; Zeng, Y.M.; Chen, X.Y. β-Elemene Suppresses the Proliferation of Human Airway Granulation Fibroblasts via Attenuation of TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 16553–16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, T.; Wang, X.; Shen, M.; Yan, X.; Fan, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Sui, H.; et al. Traditional Uses, Chemical Constituents and Biological Activities of Plants from the Genus Thymus. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1900254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Shukla, I.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Contreras, M. del M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fathi, H.; Nasrabadi, N.N.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Thymol, Thyme, and Other Plant Sources: Health and Potential Uses. Phyther. Res. 2018, 32, 1688–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghffar, E.A.; Obaid, W.A.; Alamoudi, M.O.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Annaz, H.; Abdelfattah, M.A.O.; Sobeh, M. Thymus Fontanesii Attenuates CCl4-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Mild Liver Fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri, S.; Mlika, M.; Nahdi, A.; Ben Ali, R.; Jameleddine, S. Thymus Vulgaris Inhibit Lung Fibrosis Progression and Oxidative Stress Induced by Bleomycin in Wistar Rats. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, R.H.; Gitter, W.; El Mokhtari, N.E.; Mathiak, M.; Both, M.; Bolte, H.; Freitag-Wolf, S.; Bewig, B. Standardized Quantification of Pulmonary Fibrosis in Histological Samples. Biotechniques 2008, 44, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Imenshahidi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Karimi, G. Effects of Plant Extracts and Bioactive Compounds on Attenuation of Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2008, 214, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lyu, L.; Xing, C.; Chen, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, M.; Ai, Z. The Pivotal Role of TGF-β/Smad Pathway in Fibrosis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1649179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Z.A.; Abu-Raghif, A.R.; Tahseen, N.J.; Rashed, K.A.; Shaker, N.S.; Fawzi, H.A. Vinpocetine Alleviated Alveolar Epithelial Cells Injury in Experimental Pulmonary Fibrosis by Targeting PPAR-γ/NLRP3/NF-ΚB and TGF-Β1/Smad2/3 Pathways. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Song, B.; Peng, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S. Zangsiwei Prevents Particulate Matter-Induced Lung Inflammation and Fibrosis by Inhibiting the TGF-β/SMAD Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.S.; Wynn, T.A. Pulmonary Fibrosis: Pathogenesis, Etiology and Regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2009, 2, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, I.; Cavalera, M.; Huang, S.; Su, Y.; Hanna, A.; Chen, B.; Shinde, A. V.; Conway, S.J.; Graff, J.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Protective Effects of Activated Myofibroblasts in the Pressure-Overloaded Myocardium Are Mediated Through Smad-Dependent Activation of a Matrix-Preserving Program. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L. TGF-β/SMAD Pathway and Its Regulation in Hepatic Fibrosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2016, 64, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, F.; Mauviel, A. Transforming Growth Factor-β and Fibrosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, D.J.; Martinez, F.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamali, H.I.; Maher, T.M. Current and Novel Drug Therapies for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2012, 6, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, D.S.; Grossfeld, D.; Renna, H.A.; Agarwala, P.; Spiegler, P.; DeLeon, J.; Reiss, A.B. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Current and Future Treatment. Clin. Respir. J. 2022, 16, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizem Cocelli, Mustafa Pehlivan, Ö.Y. BOLETIN LATINOAMERICANO Y DEL CARIBE DE PLANTAS MEDICINALES Y AROMÁTICAS. Bol. Latinoam. Y DEL CARIBE PLANTAS Med. Y AROMÁTICAS 2021, 20, 394–405. [CrossRef]

- Yumrutaş, Ö.; Yumrutaş, P.; Martinez, J.L.; Pérez, G.A.; Korkmaz, M.; Escobar, J.; Taşdemir, D.; Rios, M.; Parlar, A. Glycyrrhiza Glabra L. Suppress the Proliferation of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Inducing Necrosis Rather than Apoptosis despite Increasing Bax Level. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumrutaş, P.; Korkmaz, M.; Pehlivan, M.; Taşdemir, D.; Yumrutaş, Ö. Roles on Antiproliferation, Apoptosis, Necrosis and Proinflammation of Micromeria Fruticosa Subsp. Brachycalyx Essential Oil Obtained by Hydrodistillation on Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dhanda, A.; Naveen; Aggarwal, N.K.; Singh, A.; Kumar, P. Evaluation of Phytochemical, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antigenotoxic, Antimutagenic and Cytotoxic Potential of Leaf Extracts of Lantana Camara. Vegetos 2024 383 2024, 38, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlar, A.; Arslan, S.O.; Yumrutas, O.; Elibol, E.; Yalcin, A.; Uckardes, F.; Aydin, H.; Dogan, M.F.; Kayhan Kustepe, E.; Ozer, M.K. Effects of Cannabinoid Receptor 2 Synthetic Agonist, AM1241, on Bleomycin Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biotech. Histochem. 2021, 96, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningrum, P.T.; Keman, S.; Sudiana, I.K.; Sulistyorini, L.; Elias, S.M.; Mulyasari, T.M.; Mamun, A. Al;

Ningrum, P.T.; Keman, S.; Sudiana, I.K.; et al. The Effect of Subchronic Polyethylene Microplastic Exposure on Pulmonary Fibrosis Through Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β in Wistar Rats. Microplastics 2025, Vol. 4, 2025, 4. [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Therapeutic Potential and Mechanisms of Rosmarinic Acid and the Extracts of Lamiaceae Plants for the Treatment of Fibrosis of Various Organs. Antioxidants 2024, Vol. 13, 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadir Zayzafon, Adnan Odeh, A.W.A. Determination of Essential Oil Composition by GC-MS and Integral Antioxidant Capacity Using Photochemiluminescence Assay of Two Thymus Leaves: Thymus Syriacus and Thymus Cilicicus from Different Syrian Locations. Herba Pol. 2012, 71–84.

- Al-Mariri, A.; Swied, G.; Oda, A.; Al Hallab, L. Antibacterial Activity of Thymus Syriacus Boiss Essential Oil and Its Components against Some Syrian Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolates. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 38, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Gökçek, İ.; Uyanık, G.; Tutar, T.; Gözer, A. Effects of Carvacrol on Hormonal, Inflammatory, Antioxidant Changes, and Ovarian Reserve in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Wistar Rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024 3984 2024, 398, 4607–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, C.; Gairola, S.; Syed, A.M.; Verma, S.; Mugale, M.N.; Sahu, B.D. Carvacrol Preserves Antioxidant Status and Attenuates Kidney Fibrosis via Modulation of TGF-Β1/Smad Signaling and Inflammation. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10587–10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, R.; Karimi, J.; Tavilani, H.; Khodadadi, I.; Hashemnia, M. Carvacrol Ameliorates the Progression of Liver Fibrosis through Targeting of Hippo and TGF-β Signaling Pathways in Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4)-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2019, 41, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashmforosh, M.; Rajabi Vardanjani, H.; Khorsandi, L.; Shariati, S.; Mohtadi, S.; Khodayar, M.J. Carvacrol Protects Rats against Bleomycin-Induced Lung Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Fibrosis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024 39712 2024, 397, 10075–10089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Body weights of animals measured over 28 days and percentage changes in body weight.

Figure 1.

Body weights of animals measured over 28 days and percentage changes in body weight.

Figure 2.

The lung images of the Control (A), Sham (B), BLM (C), BLM + Vehicle (D), BLM + TS50 (E), and BLM + TS100 (F) groups.

Figure 2.

The lung images of the Control (A), Sham (B), BLM (C), BLM + Vehicle (D), BLM + TS50 (E), and BLM + TS100 (F) groups.

Figure 3.

Lung Index Scores.

Figure 3.

Lung Index Scores.

Figure 4.

TGF-β1, SMAD-2, COL1, and α-SMA mRNA levels in lung tissues.

Figure 4.

TGF-β1, SMAD-2, COL1, and α-SMA mRNA levels in lung tissues.

Figure 5.

TGF-β1, SMAD2, COL1, and α-SMA Protein Levels.

Figure 5.

TGF-β1, SMAD2, COL1, and α-SMA Protein Levels.

Figure 6.

TNF-α levels in BALF and ROS levels in Lung tissues.

Figure 6.

TNF-α levels in BALF and ROS levels in Lung tissues.

Figure 7.

Histological fibrosis scores in lung tissues.

Figure 7.

Histological fibrosis scores in lung tissues.

Figure 8.

Histopathological images of lung tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A: Control, B:SHAM, C:BLM, D:BM+Vehicle, E:BLM+TS50, F:BLM+TS100.

Figure 8.

Histopathological images of lung tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A: Control, B:SHAM, C:BLM, D:BM+Vehicle, E:BLM+TS50, F:BLM+TS100.

Figure 9.

Masson's trichrome-stained lung tissue sections. A: Control, B:SHAM, C:BLM, D:BM+Vehicle, E:BLM+TS50, F:BLM+TS100.

Figure 9.

Masson's trichrome-stained lung tissue sections. A: Control, B:SHAM, C:BLM, D:BM+Vehicle, E:BLM+TS50, F:BLM+TS100.

Figure 10.

Serum Biochemical Parameters.

Figure 10.

Serum Biochemical Parameters.

Figure 11.

Establishment of the pulmonary fibrosis model by intratracheal administration of bleomycin.

Figure 11.

Establishment of the pulmonary fibrosis model by intratracheal administration of bleomycin.

Table 2.

Ashcroft scale for histological grading of lung damage.

Table 2.

Ashcroft scale for histological grading of lung damage.

| Grade |

Histological Findings |

| 0 |

Normal lung, |

| 1 |

Alveoli partly enlarged and rarefied, but no fibrotic masses present |

| 2 |

Alveoli partly enlarged and rarefied, but no fibrotic masses |

| 3 |

Alveoli partly enlarged and rarefied, but no fibrotic masses |

| 4 |

Single fibrotic masses (fibrotic area covering ≤10% of the microscopic field) |

| 5 |

Confluent fibrotic masses (fibrotic area covering >10% and ≤50% of the microscopic field). |

| 6 |

Large contiguous fibrotic masses (fibrotic area covering >50% of the microscopic field) |

| 7 |

Alveoli nearly obliterated with fibrous masses but a few air bubbles remain |

| 8 |

Microscopic field completely occupied by fibrotic masses |

Table 3.

Compounds identified in the GC-MS analysis of T. syriacus essential oil.

Table 3.

Compounds identified in the GC-MS analysis of T. syriacus essential oil.

| NO |

R.T. |

% |

Compounds |

| 1 |

11.833 |

0.09 |

Bicyclo[3.1.0]hex-2-ene, 4-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)- |

| 2 |

11.969 |

0.09 |

Camphene |

| 3 |

13.591 |

0.08 |

1-octen-3-ol |

| 4 |

13.934 |

0.15 |

3-octanone |

| 5 |

14.394 |

0.20 |

3-octanol |

| 6 |

15.356 |

0.24 |

α-Terpinene |

| 7 |

15.740 |

0.52 |

Benzene, methyl(1-methylethyl)- |

| 8 |

17.510 |

0.44 |

γ-terpinene |

| 9 |

19.645 |

0.26 |

Linalool |

| 10 |

21.593 |

0.10 |

Bicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-3-ol,6,6-dimethyl-2-methylene- |

| 11 |

21.935 |

1.87 |

(+)-2-Bornanone |

| 12 |

22.979 |

6.85 |

Endo-borneol |

| 13 |

24.370 |

0.23 |

α-Terpineol |

| 14 |

24.684 |

0.24 |

Dihydrocarvone |

| 15 |

26.378 |

0.18 |

Thymyl methyl ether |

| 16 |

27.247 |

0.83 |

Thymoquinone |

| 17 |

27.430 |

0.24 |

Cis-α-bisabolene |

| 18 |

27.645 |

0.34 |

Linalyl acetate |

| 19 |

29.455 |

53.36 |

Carvacrol |

| 20 |

29.795 |

15.59 |

Carvone |

| 22 |

35.031 |

1.24 |

Caryophyllene |

| 23 |

35.885 |

0.17 |

(+)-Aromadendrene |

| 24 |

37.473 |

2.60 |

1h-cycloprop[e]azulen-7-ol,decahydro-1,1,7-trimethyl-4-methylene |

| 25 |

37.665 |

0.10 |

γ-muurolene |

| 26 |

37.886 |

0.37 |

Globulol |

| 27 |

38.318 |

0.34 |

Ledene |

| 28 |

38.495 |

0.23 |

Naphthalene |

| 29 |

38.723 |

0.40 |

Isospathulenol |

| 30 |

39.100 |

0.14 |

Germacrene-d |

| 31 |

39.486 |

0.42 |

δ-cadinene |

| 32 |

40.741 |

0.12 |

1h-benzocyclohepten-7-ol, |

| 33 |

41.376 |

0.13 |

Cyclohexene, 1,2,4-trimethyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)- |

| 34 |

41.762 |

2.16 |

1h-cycloprop[e]azulen-7-ol, |

| 35 |

41.998 |

1.36 |

Caryophyllene oxide |

| 37 |

43.079 |

0.24 |

3-methyl-5-(2,6,6-trımethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-1-pentyn-3-ol |

| 38 |

43.593 |

0.12 |

Ledene |

| 39 |

43.939 |

0.29 |

1h-cycloprop[e]azulene, |

| 41 |

44.265 |

0.11 |

Tau-cadinol |

| 42 |

44.482 |

0.31 |

4a,7-methano-4ah-naphth[1,8a-b]oxirene, |

| 43 |

44.798 |

0.21 |

α-Cadinol |

| 44 |

44.914 |

0.16 |

Androstan-17-one, 3-ethyl-3-hydroxy |

| 46 |

46.039 |

0.11 |

1-naphthalenamine, 4-bromo |

| 47 |

53.643 |

0.15 |

3-benzylsulfonyl-2,6,6-trimethylbicyclo(3.1.1)heptane |

| 49 |

54.165 |

0.12 |

7,9-di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro[4.5]deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione |

| 51 |

55.666 |

0.18 |

n-Hexadecanoic acid |

| 52 |

61.282 |

1.03 |

Methanesulfonic acid, |

| 54 |

61.728 |

0.10 |

3,3,5,8,10,10-hexamethyltricyclo[6.2.2.0(2,7)]dodeca-5,11-diene-4-spiro-1'-cyclo |

| 55 |

61.991 |

0.53 |

Indan, 2-butyl-5-hexyl |

| 56 |

63.397 |

0.09 |

2,6,11,15-tetramethyl-hexadeca-2,6,8,10,14-pentaene |

| 57 |

66.156 |

1.72 |

Eicosane |

| |

|

2.8 |

Monoterpenes |

| |

|

78.6 |

Oxygenated monoterpenes |

| |

|

7.5 |

Sesquitepernes |

| |

|

8.1 |

Other |

| |

Total |

97.15 |

|

Table 1.

Primer sequences for target mRNA analysis in lung tissue.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for target mRNA analysis in lung tissue.

| Gapdh |

Forward |

CACAGTCAAGGCTGAGAATG |

| |

Reverse |

GCATTGCTGACAATCTTGAG |

| Tgf-β |

Forward |

TACGCCAAAGAAGTCACCCG |

| |

Reverse |

GTGAGCACTGAAGCGAAAGC |

| SMAD2 |

Forward |

AGGGCTTTGAGGCTGTCTACC |

| |

Reverse |

GTCCACGCTGGCATCTTCTG |

| COL1 |

Forward |

GCAAGAGGCGAGAGAGGTTT |

|

|

| |

Reverse |

ACCAACGTTACCAATGGGGC |

|

|

| α-SMA |

Forward |

TTCGTGACTACTGCTGAGCG |

| |

Reverse |

CTGTCAGCAATGCCTGGGTA |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |