Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

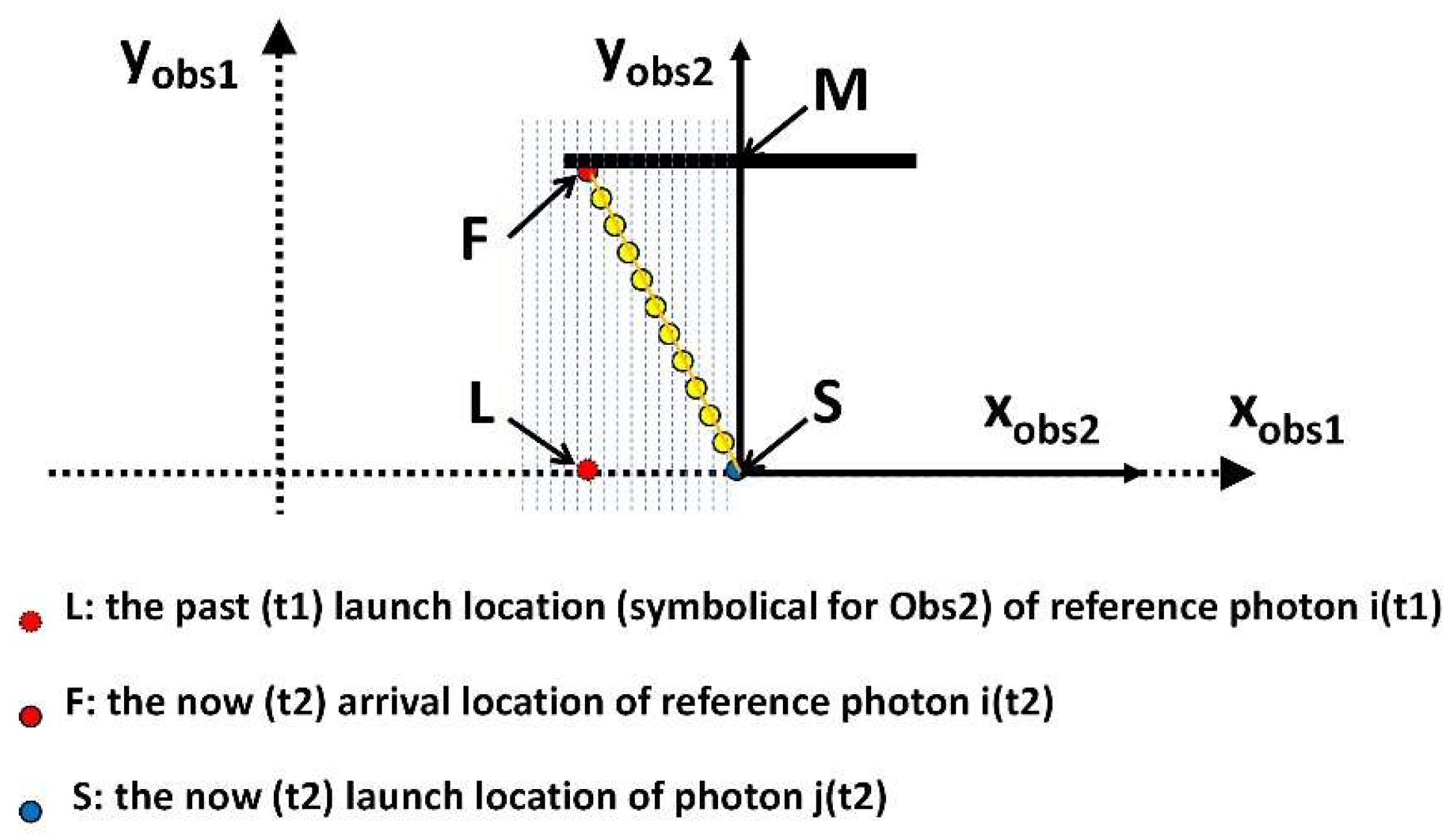

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Photon Trajectories in Real Space

2.1.1. Real-Space Emission and Propagation Model

2.1.2. Analytical Derivation of Lateral Trajectory Shift

- the magnitude of the source velocity v,

- the propagation distance L = c · Δt,

- and the angular orientation α between v and the emission direction.

2.1.3. Implications for the Equivalence Principle

2.1.4. Relevance for Optical Precision Measurement

2.2. Experimental Methodology: Verification of Real-Space Photon Trajectories

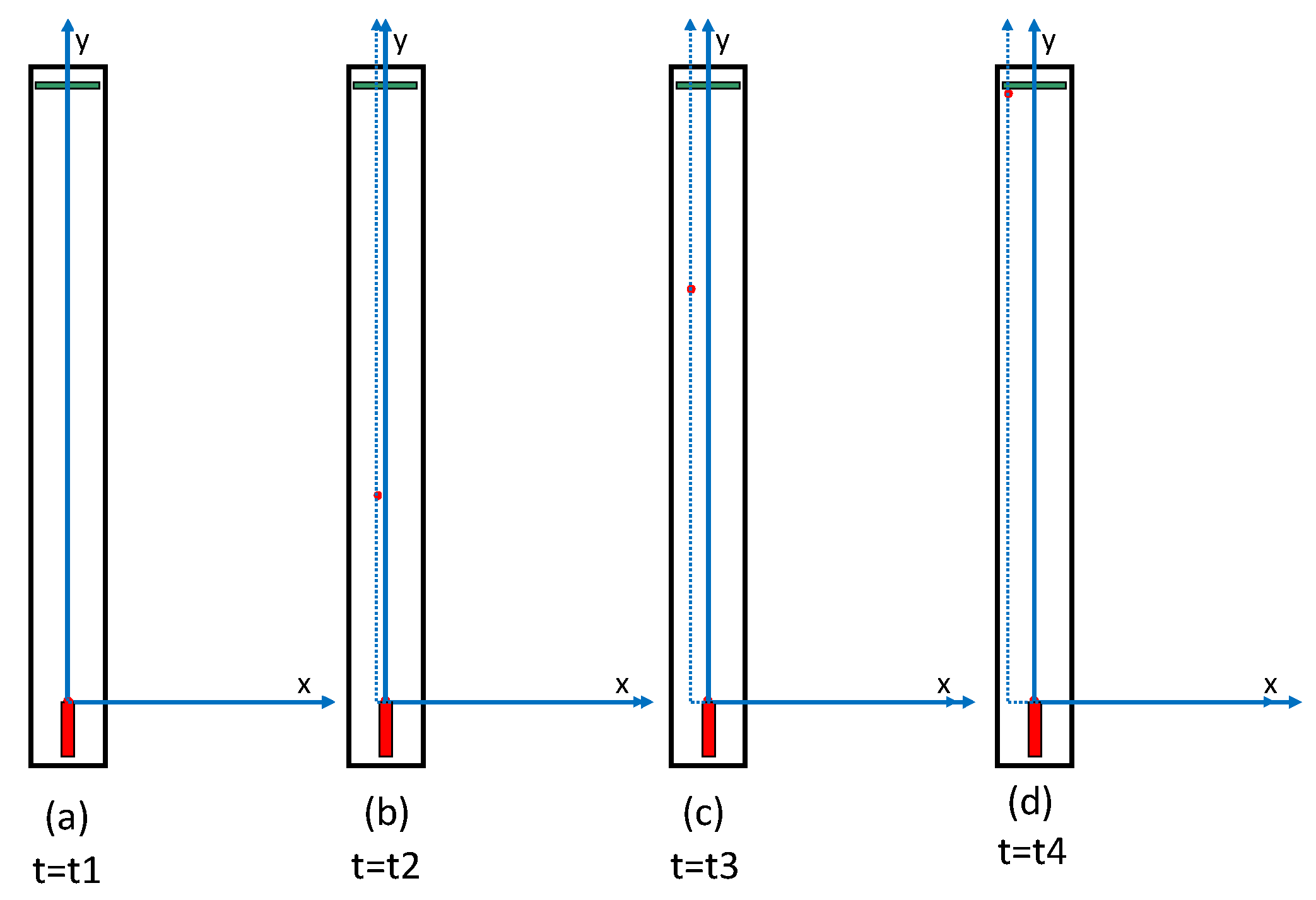

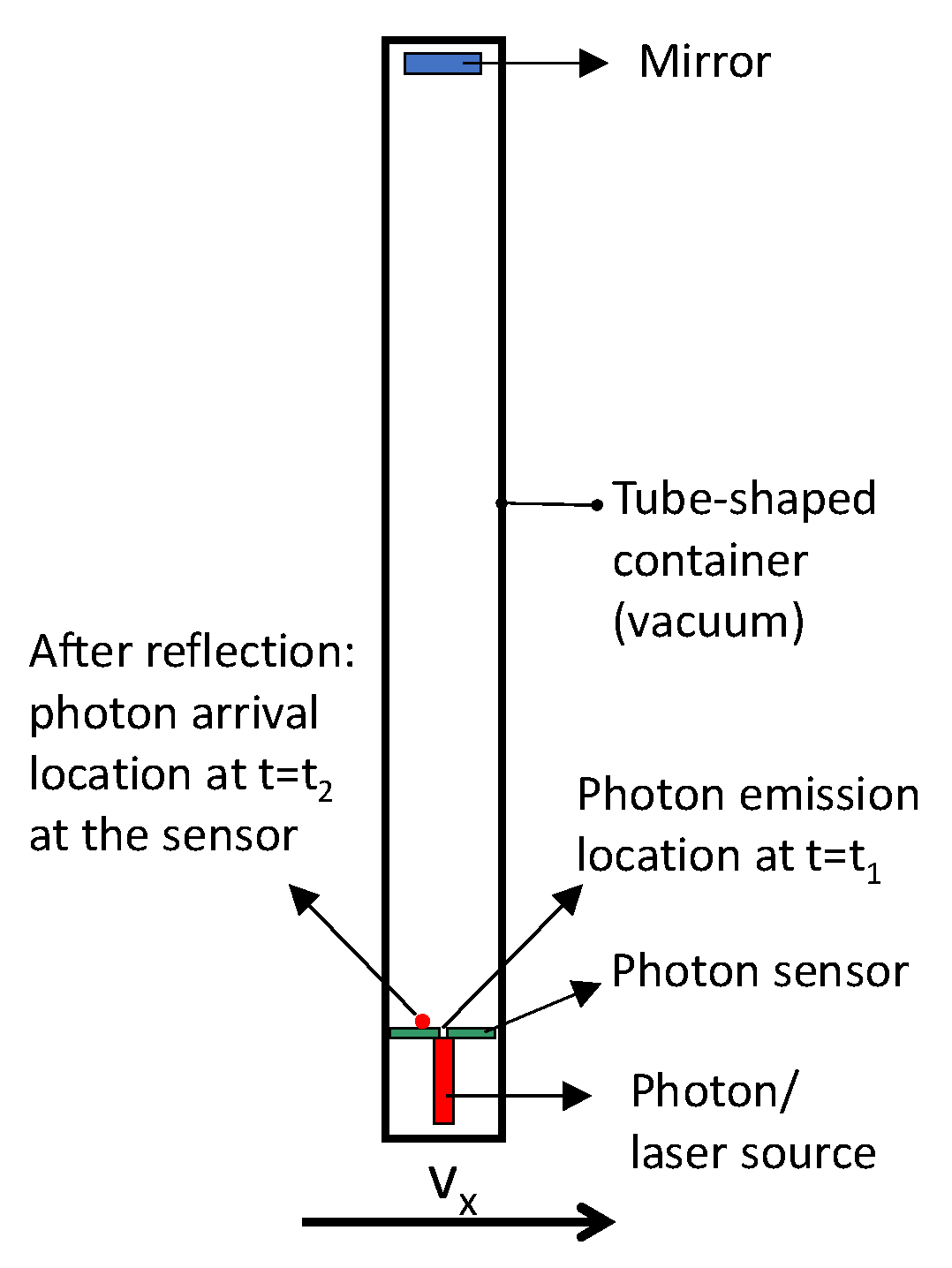

2.2.1. Experimental Principle

2.2.2. Optical Setup

2.2.3. Reference Frame Considerations

2.2.4. Measurement Protocol

2.2.5. Experimental Observables

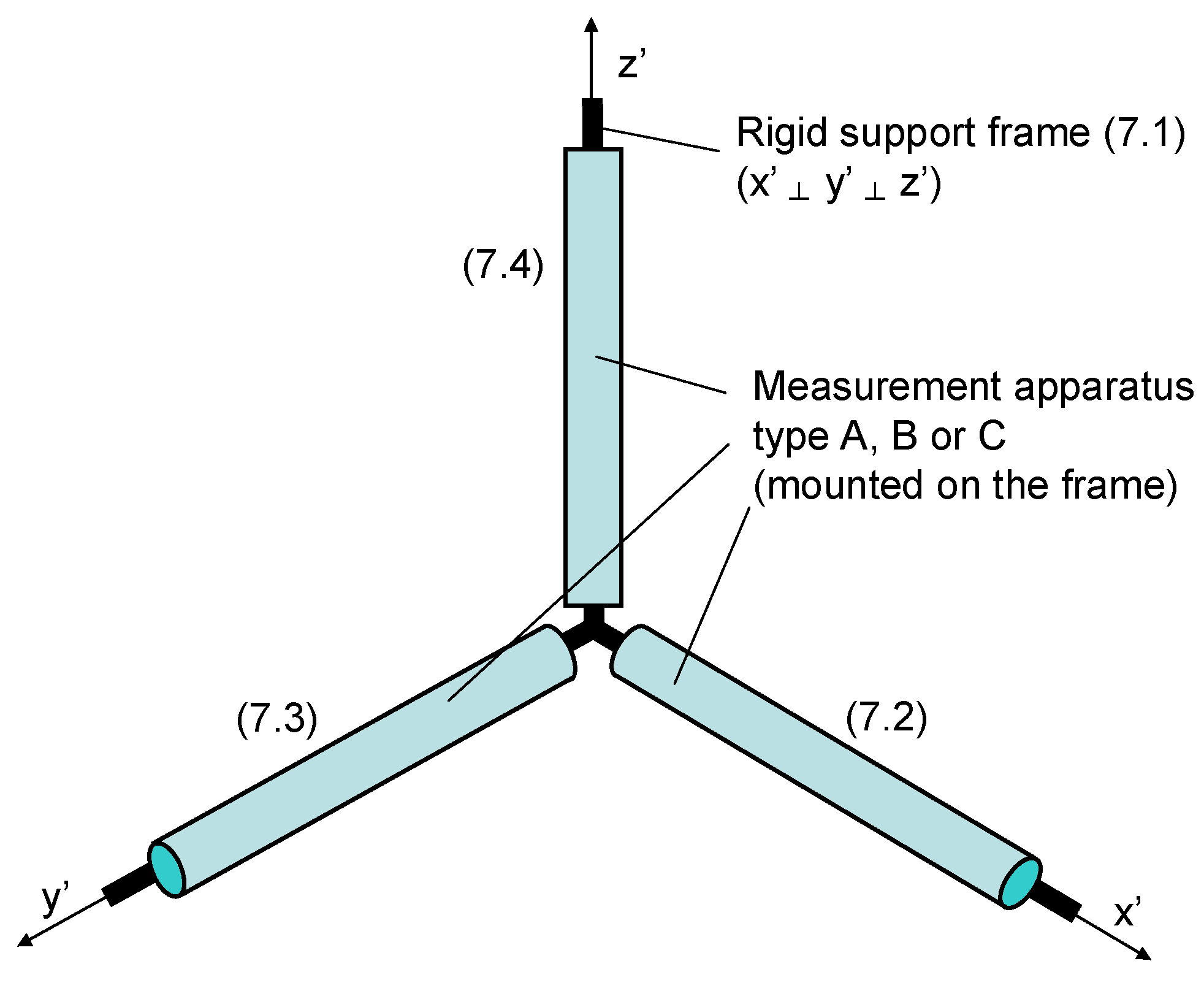

2.3. RVMD Concept and Optical Configuration

2.3.1. Measurement Principle

2.3.2. Optical Configuration

2.3.3. Sensitivity and Scaling Behavior

2.3.4. Reference Frame Independence

2.3.5. Suitability for Space Applications

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Observation of Real-Space Photon Trajectory Deviations

3.2. Temporal Modulation of the Displacement Signal

3.3. Comparison with Theoretical Predictions

3.4. Central Experimental Result: Falsification of the Equivalence Principle

3.5. Implications for Optical Measurement Accuracy

3.6. Applications

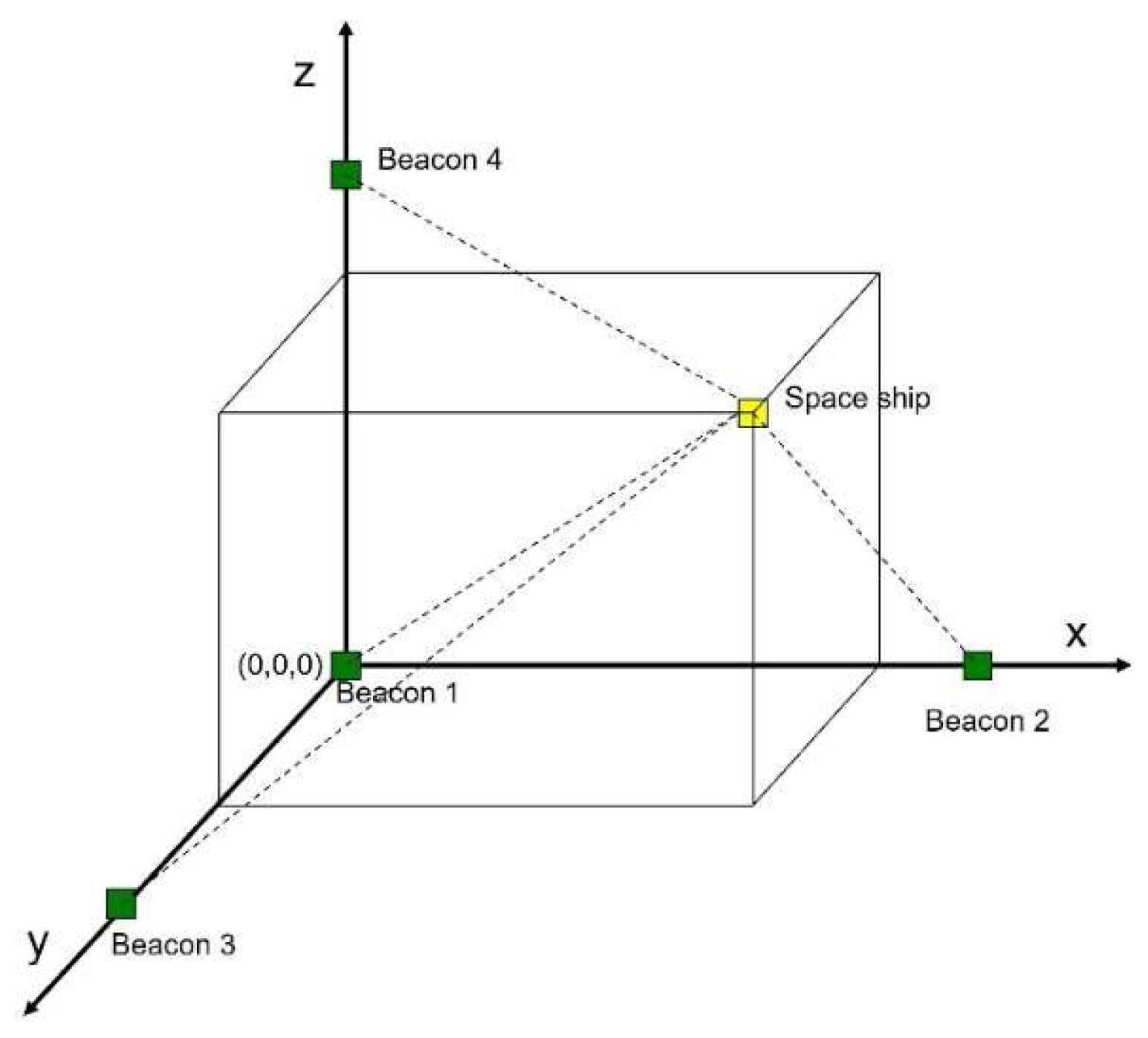

3.6.1. Planets, Moons and Cosmology: Determination of Full Three-Dimensional Real Velocity Vectors

3.6.2. Hazardous Asteroids and Planetary Defense

3.6.3. Real-Space Location Determination and Autonomous Navigation

3.6.4. High-End Theodolites and Terrestrial Precision Surveying

3.6.5. Ultra-Precision Sports Measurements

4. Discussion

4.1. Consequences for Optical Precision Measurement

4.2. Implications for Space Technology Applications

4.3. Orbital Velocity Vector Modulation

4.4. RVMD as an Instrumental Response to Real-Space Effects

4.5. Integration with Spacecraft Metrology Systems

4.6. Broader Implications and Paradigm Shift

4.7. Patent

4.8. Mendeley Data Repository

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

GenAI Disclosure Statement

References

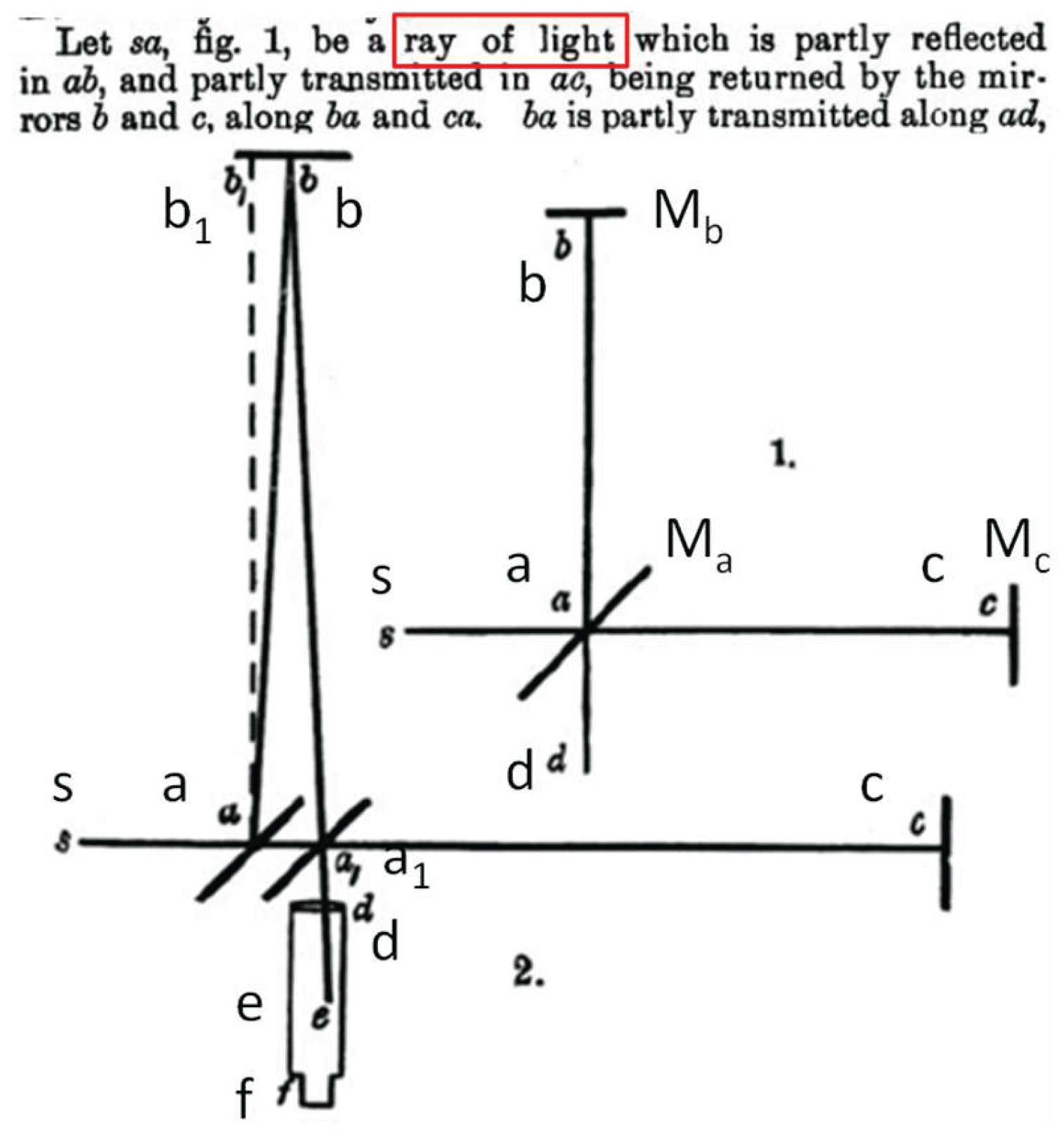

- Michelson, A.; Morley, E. On the relative motion of the Earth and the luminiferous ether. Am. J. Sci. 1887, 203, 333–345. Available online: https://history.aip.org/exhibits/gap/PDF/michelson.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Brauns, E. On two thought experiments revealing two massive theoretical anomalies, proving both the contemporary “ray of light” paradigm to be flawed and the impossibility of a photon to inherit any velocity vector component from its source. Optik 2021, 230 165858, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, E. On a straightforward laser experiment, confirming the previously published irrevocable falsification of the Equivalence Principle paradigm for photon phenomena. Optik 2021, 242 167178, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, E. On the concept and potential applications of a photons based device, measuring the velocity vector of an object, moving at high speed in space. Results in Optics 2023, 10 100349, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Routledge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brauns, E. Downloadable EMDR023_E_Brauns_Figure32. gif. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h/1/files/981b3902-7e32-48ce-b10a-4a390c5db396.

- Brauns, E. Downloadable EMDR006_E_Brauns_Fig09_CS_Obs1_Obs2. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h/1/files/6424057c-b1cb-4b61-a518-645a6e3bb279.

- Brauns, E. Downloadable EMDR022_E_Brauns_Figure04_B. gif. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h/1/files/3651260b-aed1-4c68-be80-bc45e018f23e.

- Brauns, E. Downloadable EMDR007_E_Brauns_Fig09_True_Obs1_Obs2. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h/1/files/3d63dcde-9cc3-4626-9e50-d541c0e39c42.

- Brauns, E. Downloadable EMDR014_E_Brauns_RVMD_USPTO_Patent_20070222971.pdf. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h/1/files/7b247b36-b517-467b-9402-1d923601b449.

- Brauns, E. Mendeley Data Repository (252 files). Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dv3bbhpb4h.

- Brauns, E. A Shattered Equivalence Principle for Photons; printed version by Ridero. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383065789_A_Shattered_Equivalence_Principle_for_Photons.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.