Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

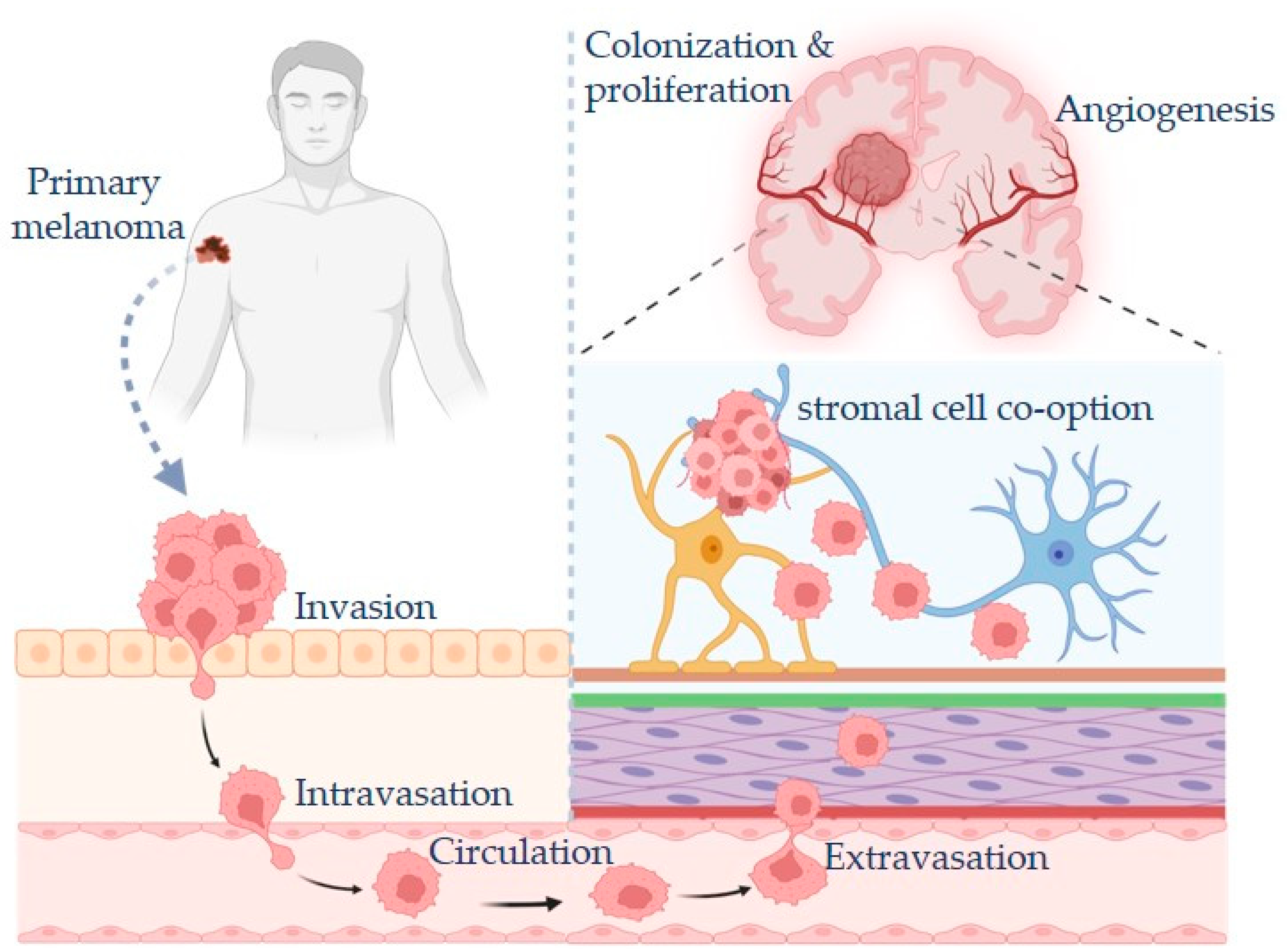

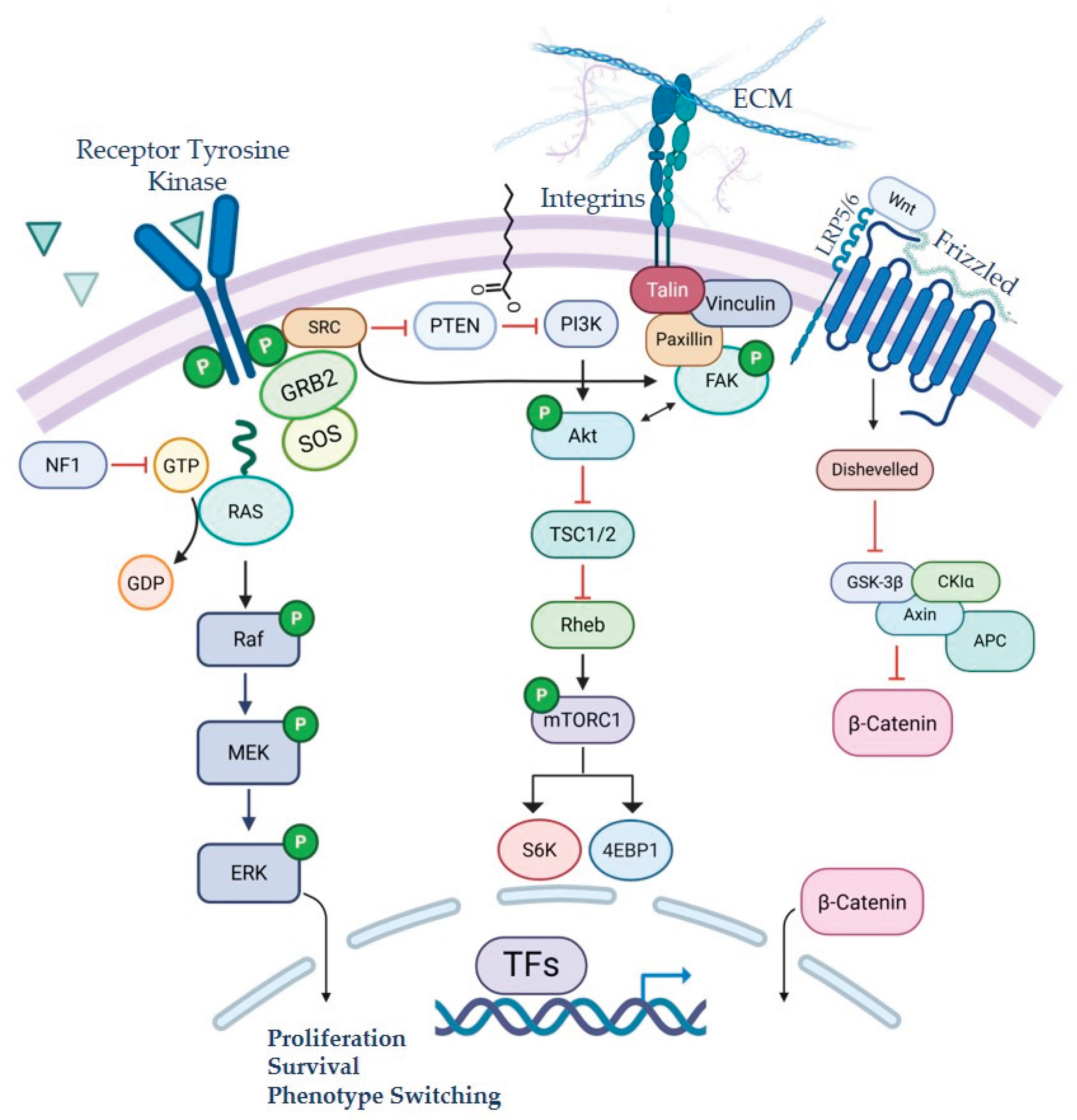

2. Mechanisms of Melanoma Metastasis

2.1. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition [EMT] and Plasticity in Melanoma

2.2. Tumor Microenvironment Contributions to Metastasis

3. Melanoma Brain Metastasis: Unique Challenges and Mechanisms

4. Diagnostic Advances in Melanoma Metastasis

5. Therapeutic Strategies for Melanoma Brain Metastasis

6. Immunological Perspectives in Melanoma Brain Metastasis

7. Translational and Preclinical Models for Studying Brain Metastasis

8. Clinical Management and Multidisciplinary Approaches

9. Future Directions and Research Gaps

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 18F-FDG | 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose |

| AE | Adverse events |

| ARE | Adverse Radiation Effect |

| AKT | Serine/threonine kinase |

| APE1 | Apurinic/apyrimidinic endodeoxyribonuclease 1 |

| ASCO | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| ASTRO | American Society for Radiation Oncology |

| BAMs | Border-associated macrophages |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| BRAF | B-Raf proto-oncogene |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CDK4/6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 |

| CMCs | Circulating melanoma cells |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF1R | Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor |

| CTCs | Circulating tumor cells |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| DICER1 | Dicer 1, ribonuclease III |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DLTs | Dose limiting toxicities |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| FATP2 | Fatty acid transport protein 2 |

| FDG-PET | Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

| FET | O-(2-18F-Fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine |

| GEMM | Genetically-engineered mouse model |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| GTPase | Guanosine triphosphatase |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| icPFS | Intracranial progression-free survival |

| IFNβ | Interferon beta |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| iORR | Intracranial objective response rate |

| IRAEs | Immune-related adverse events |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| MITF | Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSD | Most Successful Dose |

| NGFR | Nerve growth factor receptor |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NRAS | Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| OS | overall survival |

| PBRM1 | Polybromo 1 |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PDGFR | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor |

| PDX | Patient-derived xenograft |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PRRX1 | Paired related homeobox 1 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| SETD2 | SET domain containing 2 |

| sFRP2 | Secreted frizzled related protein 2 |

| SLC27A2 | Solute carrier family 27 member 2 |

| SNO | Society for Neuro-Oncology |

| SOX10 | SRY-box transcription factor 10 |

| SPARC | Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine |

| SRS | Stereotactic radiosurgery |

| S&T | Safety and tolerability |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TCF/LEF | Transcription factor / lymphoid enhancer-binding factor |

| TFs | Transcription factors |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TVEC | Talimogene Laherparepvec |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WBRT | Whole-brain radiotherapy |

| YAP1 | Yes-associated protein 1 |

| ZEB1 | Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 |

| ZEB2/SNAIL2 | Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 / snail family transcriptional repressor 2 |

References

- Sundararajan, S.; Thida, A. M.; Yadlapati, S.; Mukkamalla, S. K. R.; Koya, S. Metastatic Melanoma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Yang, A.; McNamara, M.; Kluger, H. M.; Tran, T.; Olino, K.; Clune, J.; Sznol, M.; Ishizuka, J. J. Causes of death and patterns of metastatic disease at the end of life for patients with advanced melanoma in the immunotherapy era. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, e21522–e21522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R. L.; Kratzer, T. B.; Giaquinto, A. N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75((1)), 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlon, N.; Doddi, S.; Yousif, R.; Najib, S.; Sheikh, T.; Abuhelwa, Z.; Burmeister, C.; Hamouda, D. M. Melanoma Treatments and Mortality Rate Trends in the US, 1975 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5((12)), e2245269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shain, A. H.; Bastian, B. C. From melanocytes to melanomas. Nature Reviews Cancer 2016, 16((6)), 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W. H., Jr.; Elder, D. E.; Guerry, D. t.; Epstein, M. N.; Greene, M. H.; Van Horn, M. A study of tumor progression: the precursor lesions of superficial spreading and nodular melanoma. Hum Pathol 1984, 15((12)), 1147–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. J.; Mihm, M. C., Jr. Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2006, 355((1)), 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasumova, G. G.; Haynes, A. B.; Boland, G. M. Lymphatic versus Hematogenous Melanoma Metastases: Support for Biological Heterogeneity without Clear Clinical Application. J Invest Dermatol 2017, 137((12)), 2466–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratì, S.; Raho, L.; De Giosa, G.; Porcelli, L.; Di Fonte, R.; Fasano, R.; Lacal, P. M.; Graziani, G.; Iacobazzi, R. M.; Azzariti, A. Unraveling vascular mechanisms in melanoma: roles of angiogenesis and vasculogenic mimicry in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Cancer Biol Med 2025, 22((11)), 1327–52. [Google Scholar]

- Caramel, J.; Papadogeorgakis, E.; Hill, L.; Browne, G. J.; Richard, G.; Wierinckx, A.; Saldanha, G.; Osborne, J.; Hutchinson, P.; Tse, G.; Lachuer, J.; Puisieux, A.; Pringle, J. H.; Ansieau, S.; Tulchinsky, E. A switch in the expression of embryonic EMT-inducers drives the development of malignant melanoma. Cancer Cell 2013, 24((4)), 466–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. V.; Tawbi, H.; Margolin, K. A.; Amravadi, R.; Bosenberg, M.; Brastianos, P. K.; Chiang, V. L.; de Groot, J.; Glitza, I. C.; Herlyn, M.; Holmen, S. L.; Jilaveanu, L. B.; Lassman, A.; Moschos, S.; Postow, M. A.; Thomas, R.; Tsiouris, J. A.; Wen, P.; White, R. M.; Turnham, T.; Davies, M. A.; Kluger, H. M. Melanoma central nervous system metastases: current approaches, challenges, and opportunities. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2016, 29((6)), 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.; Johansen, E. L.; Hojholt, K. L.; Pedersen, M. W.; Mogensen, A. M.; Petersen, S. K.; Haslund, C. A.; Donia, M.; Schmidt, H.; Bastholt, L.; Friis, R.; Svane, I. M.; Ellebaek, E. Survival improvements in patients with melanoma brain metastases and leptomeningeal disease in the modern era: Insights from a nationwide study (2015-2022). Eur J Cancer 2025, 217, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate-Daga, D.; Ramello, M. C.; Smalley, I.; Forsyth, P. A.; Smalley, K. S. M. The biology and therapeutic management of melanoma brain metastases. Biochem Pharmacol 2018, 153, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, T.; Niessner, H.; Sinnberg, T.; Thomas, I.; Meiwes, A.; Garbe, C.; Garzarolli, M.; Rauschenberg, R.; Eigentler, T.; Meier, F. An open-label, single-arm, phase II trial of buparlisib in patients with melanoma brain metastases not eligible for surgery or radiosurgery-the BUMPER study. Neurooncol Adv 2020, 2((1)), vdaa140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonzano, E.; Barruscotti, S.; Chiellino, S.; Montagna, B.; Bonzano, C.; Imarisio, I.; Colombo, S.; Guerrini, F.; Saddi, J.; La Mattina, S.; Tomasini, C. F.; Spena, G.; Pedrazzoli, P.; Lancia, A. Current Treatment Paradigms for Advanced Melanoma with Brain Metastases. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26((8)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutzmer, R.; Vordermark, D.; Hassel, J. C.; Krex, D.; Wendl, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Sickmann, T.; Rieken, S.; Pukrop, T.; Höller, C.; Eigentler, T. K.; Meier, F. Melanoma brain metastases - Interdisciplinary management recommendations 2020. Cancer Treat Rev 2020, 89, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G. V.; Atkinson, V.; Lo, S.; Sandhu, S.; Guminski, A. D.; Brown, M. P.; Wilmott, J. S.; Edwards, J.; Gonzalez, M.; Scolyer, R. A.; Menzies, A. M.; McArthur, G. A. Combination nivolumab and ipilimumab or nivolumab alone in melanoma brain metastases: a multicentre randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018, 19((5)), 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, A.; Fajkiel-Madajczyk, A.; Ohla, J.; Woźniak-Dąbrowska, K.; Liss, S.; Gryczka, K.; Smuczyński, W.; Ziółkowska, E.; Bożiłow, D.; Śniegocki, M.; Wiciński, M. Current Treatment of Melanoma Brain Metastases. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawbi, H. A.; Forsyth, P. A.; Algazi, A.; Hamid, O.; Hodi, F. S.; Moschos, S. J.; Khushalani, N. I.; Lewis, K.; Lao, C. D.; Postow, M. A.; Atkins, M. B.; Ernstoff, M. S.; Reardon, D. A.; Puzanov, I.; Kudchadkar, R. R.; Thomas, R. P.; Tarhini, A.; Pavlick, A. C.; Jiang, J.; Avila, A.; Demelo, S.; Margolin, K. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Melanoma Metastatic to the Brain. N Engl J Med 2018, 379((8)), 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M. F.; Simmons, J. L.; Boyle, G. M. Heterogeneity in Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, Y. Z.; Lanjanian, H.; Fayazi, R.; Salimi, M.; Hoseyni, B. H. M.; Noroozizadeh, M. H.; Masoudi-Nejad, A. Heterogeneity and molecular landscape of melanoma: implications for targeted therapy. Mol Biomed 2024, 5((1)), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Fernandez del Ama, L.; Ferguson, J.; Kamarashev, J.; Wellbrock, C.; Hurlstone, A. Heterogeneous tumor subpopulations cooperate to drive invasion. Cell Rep 2014, 8((3)), 688–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shain, A. H.; Yeh, I.; Kovalyshyn, I.; Sriharan, A.; Talevich, E.; Gagnon, A.; Dummer, R.; North, J.; Pincus, L.; Ruben, B.; Rickaby, W.; D'Arrigo, C.; Robson, A.; Bastian, B. C. The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. N Engl J Med 2015, 373((20)), 1926–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C. M.; Urist, M. M.; Karakousis, C. P.; Smith, T. J.; Temple, W. J.; Drzewiecki, K.; Jewell, W. R.; Bartolucci, A. A.; Mihm, M. C., Jr.; Barnhill, R. Efficacy of 2-cm surgical margins for intermediate-thickness melanomas (1 to 4 mm). Results of a multi-institutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg 1993, 218((3)), 262-7; discussion 267-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsky, W. E.; Theodosakis, N.; Bosenberg, M. Melanoma metastasis: new concepts and evolving paradigms. Oncogene 2014, 33((19)), 2413–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, G.; Buccarelli, M.; Arasi, M. B.; Rossi, S.; Pisanu, M. E.; Bellenghi, M.; Lintas, C.; Tabolacci, C. BRAF Mutations in Melanoma: Biological Aspects, Therapeutic Implications, and Circulating Biomarkers. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, G. V.; Menzies, A. M.; Nagrial, A. M.; Haydu, L. E.; Hamilton, A. L.; Mann, G. J.; Hughes, T. M.; Thompson, J. F.; Scolyer, R. A.; Kefford, R. F. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29((10)), 1239–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengarini, C.; Mussi, M.; Veronesi, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Lambertini, M.; Dika, E. BRAF V600K vs. BRAF V600E: a comparison of clinical and dermoscopic characteristics and response to immunotherapies and targeted therapies. Clin Exp Dermatol 2022, 47((6)), 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holderfield, M.; Deuker, M. M.; McCormick, F.; McMahon, M. Targeting RAF kinases for cancer therapy: BRAF-mutated melanoma and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14((7)), 455–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padua, R. A.; Barrass, N.; Currie, G. A. A novel transforming gene in a human malignant melanoma cell line. Nature 1984, 311((5987)), 671–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombino, M.; Capone, M.; Lissia, A.; Cossu, A.; Rubino, C.; De Giorgi, V.; Massi, D.; Fonsatti, E.; Staibano, S.; Nappi, O.; Pagani, E.; Casula, M.; Manca, A.; Sini, M.; Franco, R.; Botti, G.; Caracò, C.; Mozzillo, N.; Ascierto, P. A.; Palmieri, G. BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30((20)), 2522–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, J. A.; Bassett, R. L., Jr.; Ng, C. S.; Curry, J. L.; Joseph, R. W.; Alvarado, G. C.; Rohlfs, M. L.; Richard, J.; Gershenwald, J. E.; Kim, K. B.; Lazar, A. J.; Hwu, P.; Davies, M. A. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer 2012, 118((16)), 4014–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkman, G. L.; Foth, M.; Kircher, D. A.; Holmen, S. L.; McMahon, M. The role of PI3'-lipid signalling in melanoma initiation, progression and maintenance. Experimental Dermatology 2022, 31((1)), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh Durban, V.; Deuker, M. M.; Bosenberg, M. W.; Phillips, W.; McMahon, M. Differential AKT dependency displayed by mouse models of BRAFV600E-initiated melanoma. J Clin Invest 2013, 123((12)), 5104–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P. B.; Kuperwasser, C.; Brunet, J. P.; Ramaswamy, S.; Kuo, W. L.; Gray, J. W.; Naber, S. P.; Weinberg, R. A. The melanocyte differentiation program predisposes to metastasis after neoplastic transformation. Nat Genet 2005, 37((10)), 1047–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodis, E.; Watson, I. R.; Kryukov, G. V.; Arold, S. T.; Imielinski, M.; Theurillat, J. P.; Nickerson, E.; Auclair, D.; Li, L.; Place, C.; Dicara, D.; Ramos, A. H.; Lawrence, M. S.; Cibulskis, K.; Sivachenko, A.; Voet, D.; Saksena, G.; Stransky, N.; Onofrio, R. C.; Winckler, W.; Ardlie, K.; Wagle, N.; Wargo, J.; Chong, K.; Morton, D. L.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Chen, G.; Noble, M.; Meyerson, M.; Ladbury, J. E.; Davies, M. A.; Gershenwald, J. E.; Wagner, S. N.; Hoon, D. S.; Schadendorf, D.; Lander, E. S.; Gabriel, S. B.; Getz, G.; Garraway, L. A.; Chin, L. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell 2012, 150((2)), 251–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankort, D.; Curley, D. P.; Cartlidge, R. A.; Nelson, B.; Karnezis, A. N.; Damsky, W. E., Jr.; You, M. J.; DePinho, R. A.; McMahon, M.; Bosenberg, M. Braf(V600E) cooperates with Pten loss to induce metastatic melanoma. Nat Genet 2009, 41((5)), 544–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, J. M.; Sharma, A.; Cheung, M.; Zimmerman, M.; Cheng, J. Q.; Bosenberg, M. W.; Kester, M.; Sandirasegarane, L.; Robertson, G. P. Deregulated Akt3 activity promotes development of malignant melanoma. Cancer Res 2004, 64((19)), 7002–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. L.; Martinka, M.; Li, G. Prognostic significance of activated Akt expression in melanoma: a clinicopathologic study of 292 cases. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23((7)), 1473–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. A.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Lin, E.; Tellez, C.; Deng, W.; Gopal, Y. N.; Woodman, S. E.; Calderone, T. C.; Ju, Z.; Lazar, A. J.; Prieto, V. G.; Aldape, K.; Mills, G. B.; Gershenwald, J. E. Integrated Molecular and Clinical Analysis of AKT Activation in Metastatic Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009, 15((24)), 7538–7546. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J. H.; Robinson, J. P.; Arave, R. A.; Burnett, W. J.; Kircher, D. A.; Chen, G.; Davies, M. A.; Grossmann, A. H.; VanBrocklin, M. W.; McMahon, M.; Holmen, S. L. AKT1 Activation Promotes Development of Melanoma Metastases. Cell Rep 2015, 13((5)), 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, D. A.; Trombetti, K. A.; Silvis, M. R.; Parkman, G. L.; Fischer, G. M.; Angel, S. N.; Stehn, C. M.; Strain, S. C.; Grossmann, A. H.; Duffy, K. L.; Boucher, K. M.; McMahon, M.; Davies, M. A.; Mendoza, M. C.; VanBrocklin, M. W.; Holmen, S. L. AKT1(E17K) Activates Focal Adhesion Kinase and Promotes Melanoma Brain Metastasis. Mol Cancer Res 2019, 17((9)), 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehranian, C.; Fankhauser, L.; Harter, P. N.; Ratcliffe, C. D. H.; Zeiner, P. S.; Messmer, J. M.; Hoffmann, D. C.; Frey, K.; Westphal, D.; Ronellenfitsch, M. W.; Sahai, E.; Wick, W.; Karreman, M. A.; Winkler, F. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as a preventive target in melanoma brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol 2022, 24((2)), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkman, G. L.; Turapov, T.; Kircher, D. A.; Burnett, W. J.; Stehn, C. M.; O'Toole, K.; Culver, K. M.; Chadwick, A. T.; Elmer, R. C.; Flaherty, R.; Stanley, K. A.; Foth, M.; Lum, D. H.; Judson-Torres, R. L.; Friend, J. E.; VanBrocklin, M. W.; McMahon, M.; Holmen, S. L. Genetic Silencing of AKT Induces Melanoma Cell Death via mTOR Suppression. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2024, 23((3)), 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, T. A.; Patnaik, A.; Fearen, I.; Olmos, D.; Papadopoulos, K.; Tunariu, N.; Sullivan, D.; Yan, L.; De Bono, J. S.; Tolcher, A. W. First-in-class phase I trial of a selective Akt inhibitor, MK2206 (MK), evaluating alternate day (QOD) and once weekly (QW) doses in advanced cancer patients (pts) with evidence of target modulation and antitumor activity. Journal of Clinical Oncology 28, 3009–3009. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Tolcher, A. W.; Papadopoulos, K. P.; Beeram, M.; Rasco, D. W.; Smith, L. S.; Gunn, S.; Smetzer, L.; Mays, T. A.; Kaiser, B.; Wick, M. J.; Alvarez, C.; Cavazos, A.; Mangold, G. L.; Patnaik, A. The Clinical Effect of the Dual-Targeting Strategy Involving PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MEK/ERK Pathways in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2012, 18((8)), 2316–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedri, D.; Karras, P.; Landeloos, E.; Marine, J. C.; Rambow, F. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal-like transition events in melanoma. 2022, 289((5)), 1352–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, M.; Takeda, K.; Nobukuni, Y.; Urabe, K.; Long, J. E.; Meyers, K. A.; Aaronson, S. A.; Miki, T. Ectopic expression of MITF, a gene for Waardenburg syndrome type 2, converts fibroblasts to cells with melanocyte characteristics. Nature Genetics 1996, 14((1)), 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotto, C.; Abbe, P.; Hemesath, T. J.; Bille, K.; Fisher, D. E.; Ortonne, J. P.; Ballotti, R. Microphthalmia gene product as a signal transducer in cAMP-induced differentiation of melanocytes. J Cell Biol 1998, 142((3)), 827–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscà, R.; Ballotti, R. Cyclic AMP a key messenger in the regulation of skin pigmentation. Pigment Cell Res 2000, 13((2)), 60–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E. R.; Horstmann, M. A.; Wells, A. G.; Weilbaecher, K. N.; Takemoto, C. M.; Landis, M. W.; Fisher, D. E. alpha-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone signaling regulates expression of microphthalmia, a gene deficient in Waardenburg syndrome. J Biol Chem 1998, 273((49)), 33042–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J. S.; Hölzel, M.; Lambert, J. P.; Buffa, F. M.; Goding, C. R. The MITF regulatory network in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2022, 35((5)), 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. L.; Lister, J. A.; Zeng, Z.; Ishizaki, H.; Anderson, C.; Kelsh, R. N.; Jackson, I. J.; Patton, E. E. Differentiated melanocyte cell division occurs in vivo and is promoted by mutations in Mitf. Development 2011, 138((16)), 3579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, K. S.; Schlegel, N. C.; Brafford, P.; Sucker, A.; Ugurel, S.; Kumar, R.; Weber, B. L.; Nathanson, K. L.; Phillips, D. J.; Herlyn, M.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R. Metastatic potential of melanomas defined by specific gene expression profiles with no BRAF signature. Pigment Cell Res 2006, 19((4)), 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, S.; Goodall, J.; Denat, L.; Rodriguez, M.; Nuciforo, P.; Hoek, K. S.; Testori, A.; Larue, L.; Goding, C. R. Mitf regulation of Dia1 controls melanoma proliferation and invasiveness. Genes Dev 2006, 20((24)), 3426–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, K.; Yasumoto, K.; Takada, R.; Takada, S.; Watanabe, K.; Udono, T.; Saito, H.; Takahashi, K.; Shibahara, S. Induction of melanocyte-specific microphthalmia-associated transcription factor by Wnt-3a. J Biol Chem 2000, 275((19)), 14013–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsky, R. I.; Raible, D. W.; Moon, R. T. Direct regulation of nacre, a zebrafish MITF homolog required for pigment cell formation, by the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev 2000, 14((2)), 158–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Goodall, J.; Verastegui, C.; Ballotti, R.; Goding, C. R. Direct regulation of the Microphthalmia promoter by Sox10 links Waardenburg-Shah syndrome (WS4)-associated hypopigmentation and deafness to WS2. J Biol Chem 2000, 275((48)), 37978–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verastegui, C.; Bille, K.; Ortonne, J. P.; Ballotti, R. Regulation of the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor gene by the Waardenburg syndrome type 4 gene, SOX10. J Biol Chem 2000, 275((40)), 30757–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondurand, N.; Pingault, V.; Goerich, D. E.; Lemort, N.; Sock, E.; Le Caignec, C.; Wegner, M.; Goossens, M. Interaction among SOX10, PAX3 and MITF, three genes altered in Waardenburg syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 2000, 9((13)), 1907–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potterf, S. B.; Furumura, M.; Dunn, K. J.; Arnheiter, H.; Pavan, W. J. Transcription factor hierarchy in Waardenburg syndrome: regulation of MITF expression by SOX10 and PAX3. Hum Genet 2000, 107((1)), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B. C.; Johnson, G.; Wang, J.; Cohen, C. SOX10: a useful marker for identifying metastatic melanoma in sentinel lymph nodes. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2015, 23((2)), 109–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsky, William E.; Curley, David P.; Santhanakrishnan, M.; Rosenbaum, Lara E.; Platt, James T.; Gould Rothberg, Bonnie E.; Taketo, Makoto M.; Dankort, D.; Rimm, David L.; McMahon, M.; Bosenberg, M. β-Catenin Signaling Controls Metastasis in Braf-Activated Pten-Deficient Melanomas. Cancer Cell 2011, 20((6)), 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, S. J.; Rambow, F.; Kumasaka, M.; Champeval, D.; Bellacosa, A.; Delmas, V.; Larue, L. Beta-catenin inhibits melanocyte migration but induces melanoma metastasis. Oncogene 2013, 32((17)), 2230–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, S. R.; Tracey, L.; Ortiz, P.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Palacios, J.; Pollán, M.; Linares, J.; Serrano, S.; Sáez-Castillo, A. I.; Sánchez, L.; Pajares, R.; Sánchez-Aguilera, A.; Artiga, M. J.; Piris, M. A.; Rodríguez-Peralto, J. L. A High-Throughput Study in Melanoma Identifies Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition as a Major Determinant of Metastasis. Cancer Research 2007, 67((7)), 3450–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, B. D.; Koss, B.; Taylor, E. M.; Storey, A. J.; West, K. L.; Byrum, S. D.; Mackintosh, S. G.; Edmondson, R.; Mahmoud, F.; Shalin, S. C.; Tackett, A. J. Loss of E-Cadherin Inhibits CD103 Antitumor Activity and Reduces Checkpoint Blockade Responsiveness in Melanoma. Cancer Res 2019, 79((6)), 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, N.; Denecker, G.; Bruneel, K.; Blancke, G.; Akay, Ö.; Taminau, J.; De Coninck, J.; De Smedt, E.; Skrypek, N.; Van Loocke, W.; Wouters, J.; Nittner, D.; Köhler, C.; Darling, D. S.; Cheng, P. F.; Raaijmakers, M. I. G.; Levesque, M. P.; Mallya, U. G.; Rafferty, M.; Balint, B.; Gallagher, W. M.; Brochez, L.; Huylebroeck, D.; Haigh, J. J.; Andries, V.; Rambow, F.; Van Vlierberghe, P.; Goossens, S.; van den Oord, J. J.; Marine, J. C.; Berx, G. The EMT Transcription Factor ZEB2 Promotes Proliferation of Primary and Metastatic Melanoma While Suppressing an Invasive, Mesenchymal-Like Phenotype. Cancer Res 2020, 80((14)), 2983–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, E.; Kim, J.; Bendesky, A.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Wolfe, C. J.; Yang, J. Snail2 is an essential mediator of Twist1-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cancer Res 2011, 71((1)), 245–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenouille, N.; Tichet, M.; Dufies, M.; Pottier, A.; Mogha, A.; Soo, J. K.; Rocchi, S.; Mallavialle, A.; Galibert, M. D.; Khammari, A.; Lacour, J. P.; Ballotti, R.; Deckert, M.; Tartare-Deckert, S. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulatory factor SLUG (SNAI2) is a downstream target of SPARC and AKT in promoting melanoma cell invasion. PLoS One 2012, 7((7)), e40378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Yan, B.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Meng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yao, X.; Luo, J. PRRX1 Is a Novel Prognostic Biomarker and Facilitates Tumor Progression Through Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Uveal Melanoma. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 754645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arozarena, I.; Bischof, H.; Gilby, D.; Belloni, B.; Dummer, R.; Wellbrock, C. In melanoma, beta-catenin is a suppressor of invasion. Oncogene 2011, 30((45)), 4531–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Day, S. J.; Hamid, O.; Urba, W. J. Targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4): a novel strategy for the treatment of melanoma and other malignancies. Cancer 2007, 110((12)), 2614–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F. S.; O'Day, S. J.; McDermott, D. F.; Weber, R. W.; Sosman, J. A.; Haanen, J. B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J. C.; Akerley, W.; van den Eertwegh, A. J.; Lutzky, J.; Lorigan, P.; Vaubel, J. M.; Linette, G. P.; Hogg, D.; Ottensmeier, C. H.; Lebbé, C.; Peschel, C.; Quirt, I.; Clark, J. I.; Wolchok, J. D.; Weber, J. S.; Tian, J.; Yellin, M. J.; Nichol, G. M.; Hoos, A.; Urba, W. J. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010, 363((8)), 711–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A. A.; Kirkwood, J. M. Tremelimumab, a fully human monoclonal IgG2 antibody against CTLA4 for the potential treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2007, 9((5)), 505–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J. J.; Cowey, C. L.; Lao, C. D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; Ferrucci, P. F.; Hill, A.; Wagstaff, J.; Carlino, M. S.; Haanen, J. B.; Maio, M.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; McArthur, G. A.; Ascierto, P. A.; Long, G. V.; Callahan, M. K.; Postow, M. A.; Grossmann, K.; Sznol, M.; Dreno, B.; Bastholt, L.; Yang, A.; Rollin, L. M.; Horak, C.; Hodi, F. S.; Wolchok, J. D. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015, 373((1)), 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Schachter, J.; Long, G. V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J. J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M. S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; Larkin, J.; Lorigan, P.; Neyns, B.; Blank, C. U.; Hamid, O.; Mateus, C.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Kosh, M.; Zhou, H.; Ibrahim, N.; Ebbinghaus, S.; Ribas, A. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015, 372((26)), 2521–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Long, G. V.; Brady, B.; Dutriaux, C.; Maio, M.; Mortier, L.; Hassel, J. C.; Rutkowski, P.; McNeil, C.; Kalinka-Warzocha, E.; Savage, K. J.; Hernberg, M. M.; Lebbé, C.; Charles, J.; Mihalcioiu, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Mauch, C.; Cognetti, F.; Arance, A.; Schmidt, H.; Schadendorf, D.; Gogas, H.; Lundgren-Eriksson, L.; Horak, C.; Sharkey, B.; Waxman, I. M.; Atkinson, V.; Ascierto, P. A. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015, 372((4)), 320–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valpione, S.; Galvani, E.; Tweedy, J.; Mundra, P. A.; Banyard, A.; Middlehurst, P.; Barry, J.; Mills, S.; Salih, Z.; Weightman, J.; Gupta, A.; Gremel, G.; Baenke, F.; Dhomen, N.; Lorigan, P. C.; Marais, R. Immune-awakening revealed by peripheral T cell dynamics after one cycle of immunotherapy. Nat Cancer 2020, 1((2)), 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Thomas, L.; Bondarenko, I.; O'Day, S.; Weber, J.; Garbe, C.; Lebbe, C.; Baurain, J. F.; Testori, A.; Grob, J. J.; Davidson, N.; Richards, J.; Maio, M.; Hauschild, A.; Miller, W. H., Jr.; Gascon, P.; Lotem, M.; Harmankaya, K.; Ibrahim, R.; Francis, S.; Chen, T. T.; Humphrey, R.; Hoos, A.; Wolchok, J. D. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2011, 364((26)), 2517–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, R. R.; Soukup, K.; Fournier, N.; Massara, M.; Galland, S.; Kornete, M.; Wischnewski, V.; Lourenco, J.; Croci, D.; Álvarez-Prado, Á. F.; Marie, D. N.; Lilja, J.; Marcone, R.; Calvo, G. F.; Santalla Mendez, R.; Aubel, P.; Bejarano, L.; Wirapati, P.; Ballesteros, I.; Hidalgo, A.; Hottinger, A. F.; Brouland, J.-P.; Daniel, R. T.; Hegi, M. E.; Joyce, J. A. The local microenvironment drives activation of neutrophils in human brain tumors. Cell 2023, 186((21)), 4546–4566.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Breckenridge, C.; Markson, S. C.; Stocking, J. H.; Nayyar, N.; Lastrapes, M.; Strickland, M. R.; Kim, A. E.; de Sauvage, M.; Dahal, A.; Larson, J. M.; Mora, J. L.; Navia, A. W.; Klein, R. H.; Kuter, B. M.; Gill, C. M.; Bertalan, M.; Shaw, B.; Kaplan, A.; Subramanian, M.; Jain, A.; Kumar, S.; Danish, H.; White, M.; Shahid, O.; Pauken, K. E.; Miller, B. C.; Frederick, D. T.; Hebert, C.; Shaw, M.; Martinez-Lage, M.; Frosch, M.; Wang, N.; Gerstner, E.; Nahed, B. V.; Curry, W. T.; Carter, B.; Cahill, D. P.; Boland, G. M.; Izar, B.; Davies, M. A.; Sharpe, A. H.; Suvà, M. L.; Sullivan, R. J.; Brastianos, P. K.; Carter, S. L. Microenvironmental Landscape of Human Melanoma Brain Metastases in Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Cancer Immunol Res 2022, 10((8)), 996–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.; Mei, W.; Robles, I.; Hagerling, C.; Allen, B. M.; Hauge Okholm, T. L.; Nanjaraj, A.; Verbeek, T.; Kalavacherla, S.; van Gogh, M.; Georgiou, S.; Daras, M.; Phillips, J. J.; Spitzer, M. H.; Roose, J. P.; Werb, Z. Cellular architecture of human brain metastases. Cell 2022, 185((4)), 729–745.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willsmore, Z. N.; Harris, R. J.; Crescioli, S.; Hussein, K.; Kakkassery, H.; Thapa, D.; Cheung, A.; Chauhan, J.; Bax, H. J.; Chenoweth, A.; Laddach, R.; Osborn, G.; McCraw, A.; Hoffmann, R. M.; Nakamura, M.; Geh, J. L.; MacKenzie-Ross, A.; Healy, C.; Tsoka, S.; Spicer, J. F.; Papa, S.; Barber, L.; Lacy, K. E.; Karagiannis, S. N. B Cells in Patients With Melanoma: Implications for Treatment With Checkpoint Inhibitor Antibodies. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 622442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurkiewicz, J.; Simiczyjew, A.; Dratkiewicz, E.; Ziętek, M.; Matkowski, R.; Nowak, D. Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22((2)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaglia, V.; Florescu, A.; Zuo, M.; Sheikh-Mohamed, S.; Gommerman, J. L. Stromal Cell-Mediated Coordination of Immune Cell Recruitment, Retention, and Function in Brain-Adjacent Regions. J Immunol 2021, 206((2)), 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shen, M.; Wu, L.; Yang, H.; Yao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Du, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Bai, Y. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: accomplices of tumor progression? Cell Death Dis 2023, 14((9)), 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Andl, T.; Zhang, Y. YAP1 controls the N-cadherin-mediated tumor-stroma interaction in melanoma progression. Oncogene 2024, 43((12)), 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, A.; Uyama, T.; Kobayashi, F.; Yamada, S.; Sugahara, K.; Rapraeger, A. C.; Sanderson, R. D. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 by myeloma cells promotes endothelial invasion and angiogenesis. Blood 2010, 115((12)), 2449–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, J.; Liang, X.; Yin, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Jin, X.; Fiskesund, R.; Tang, K.; Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, W.; Mo, S.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, F.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, J.; Wang, N.; Huang, B. Fibrin Stiffness Mediates Dormancy of Tumor-Repopulating Cells via a Cdc42-Driven Tet2 Epigenetic Program. Cancer Research 2018, 78((14)), 3926–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicea, G. M.; Rebecca, V. W.; Goldman, A. R.; Fane, M. E.; Douglass, S. M.; Behera, R.; Webster, M. R.; Kugel, C. H., 3rd; Ecker, B. L.; Caino, M. C.; Kossenkov, A. V.; Tang, H. Y.; Frederick, D. T.; Flaherty, K. T.; Xu, X.; Liu, Q.; Gabrilovich, D. I.; Herlyn, M.; Blair, I. A.; Schug, Z. T.; Speicher, D. W.; Weeraratna, A. T. Changes in Aged Fibroblast Lipid Metabolism Induce Age-Dependent Melanoma Cell Resistance to Targeted Therapy via the Fatty Acid Transporter FATP2. Cancer Discov 2020, 10((9)), 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicea, G. M.; Patel, P.; Portuallo, M. E.; Fane, M. E.; Wei, M.; Chhabra, Y.; Dixit, A.; Carey, A. E.; Wang, V.; Rocha, M. R.; Behera, R.; Speicher, D. W.; Tang, H.-Y.; Kossenkov, A. V.; Rebecca, V. W.; Wirtz, D.; Weeraratna, A. T. Age-Related Increases in IGFBP2 Increase Melanoma Cell Invasion and Lipid Synthesis. Cancer Research Communications 2024, 4((8)), 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Silva, S.; Benito-Martín, A.; Nogués, L.; Hernández-Barranco, A.; Mazariegos, M. S.; Santos, V.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Ximénez-Embún, P.; Kataru, R. P.; Lopez, A. A.; Merino, C.; Sánchez-Redondo, S.; Graña-Castro, O.; Matei, I.; Nicolás-Avila, J.; Torres-Ruiz, R.; Rodríguez-Perales, S.; Martínez, L.; Pérez-Martínez, M.; Mata, G.; Szumera-Ciećkiewicz, A.; Kalinowska, I.; Saltari, A.; Martínez-Gómez, J. M.; Hogan, S. A.; Saragovi, H. U.; Ortega, S.; Garcia-Martin, C.; Boskovic, J.; Levesque, M. P.; Rutkowski, P.; Hidalgo, A.; Muñoz, J.; Megías, D.; Mehrara, B. J.; Lyden, D.; Peinado, H. Melanoma-derived small extracellular vesicles induce lymphangiogenesis and metastasis through an NGFR-dependent mechanism. Nat Cancer 2021, 2((12)), 1387–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumusay, O.; Coskun, U.; Akman, T.; Ekinci, A. S.; Kocar, M.; Erceleb, O. B.; Yazıcı, O.; Kaplan, M. A.; Berk, V.; Cetin, B.; Taskoylu, B. Y.; Yildiz, A.; Goksel, G.; Alacacioglu, A.; Demirci, U.; Algin, E.; Uysal, M.; Oztop, I.; Oksuzoglu, B.; Dane, F.; Gumus, M.; Buyukberber, S. Predictive factors for the development of brain metastases in patients with malignant melanoma: a study by the Anatolian society of medical oncology. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014, 140((1)), 151–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taillibert, S.; Le Rhun, É. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Cancer Radiother 2015, 19((1)), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, E. A.; Mietz, J.; Arteaga, C. L.; DePinho, R. A.; Mohla, S. Brain metastasis: opportunities in basic and translational research. Cancer Res 2009, 69((15)), 6015–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, G.; Ascha, M. S.; Waite, K. A.; Dmukauskas, M.; Wang, X.; Royce, T. J.; Calip, G. S.; Waxweiler, T.; Rusthoven, C. G.; Kavanagh, B. D.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J. S. Sex Differences in Odds of Brain Metastasis and Outcomes by Brain Metastasis Status after Advanced Melanoma Diagnosis. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16((9)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, I.; Molnár, J.; Fazakas, C.; Haskó, J.; Krizbai, I. A. Role of the blood-brain barrier in the formation of brain metastases. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14((1)), 1383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienast, Y.; von Baumgarten, L.; Fuhrmann, M.; Klinkert, W. E.; Goldbrunner, R.; Herms, J.; Winkler, F. Real-time imaging reveals the single steps of brain metastasis formation. Nat Med 2010, 16((1)), 116–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchan, A.; Kalogirou-Baldwin, P.; Johnson, R.; Kho, D. T.; Joseph, W.; Hucklesby, J.; Finlay, G. J.; O'Carroll, S. J.; Angel, C. E.; Graham, E. S. Real-Time Measurement of Melanoma Cell-Mediated Human Brain Endothelial Barrier Disruption Using Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing Technology. Biosensors (Basel) 2019, 9((2)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchan, A.; Martin, O.; Hucklesby, J. J. W.; Finlay, G.; Johnson, R. H.; Robilliard, L. D.; O'Carroll, S. J.; Angel, C. E.; Graham, E. S. Analysis of Melanoma Secretome for Factors That Directly Disrupt the Barrier Integrity of Brain Endothelial Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M.; Christofori, G. Rebuilding cancer metastasis in the mouse. Mol Oncol 2013, 7((2)), 283–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obenauf, A. C.; Massagué, J. Surviving at a Distance: Organ-Specific Metastasis. Trends Cancer 2015, 1((1)), 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M. S.; Serres, S.; Anthony, D. C.; Sibson, N. R. Functional role of endothelial adhesion molecules in the early stages of brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol 2014, 16((4)), 540–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalise, A. A.; Kakogiannos, N.; Zanardi, F.; Iannelli, F.; Giannotta, M. The blood-brain and gut-vascular barriers: from the perspective of claudins. Tissue Barriers 2021, 9((3)), 1926190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, D. P.; Palmieri, D.; Hua, E.; Hargrave, E.; Herring, J. M.; Qian, Y.; Vega-Valle, E.; Weil, R. J.; Stark, A. M.; Vortmeyer, A. O.; Steeg, P. S. Reactive glia are recruited by highly proliferative brain metastases of breast cancer and promote tumor cell colonization. Clin Exp Metastasis 2008, 25((7)), 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placone, A. L.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A.; Searson, P. C. The role of astrocytes in the progression of brain cancer: complicating the picture of the tumor microenvironment. Tumour Biol 2016, 37((1)), 61–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, S.; Scomparin, A.; Ben-Shushan, D.; Yeini, E.; Ofek, P.; Nahmad, A. D.; Soffer, S.; Ionescu, A.; Ruggiero, A.; Barzel, A.; Brem, H.; Hyde, T. M.; Barshack, I.; Sinha, S.; Ruppin, E.; Weiss, T.; Madi, A.; Perlson, E.; Slutsky, I.; Florindo, H. F.; Satchi-Fainaro, R. MCP-1/CCR2 axis inhibition sensitizes the brain microenvironment against melanoma brain metastasis progression. JCI Insight 2022, 7, (17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yao, J.; Lowery, F. J.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, W. C.; Li, P.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Ellis, K.; Cheerathodi, M.; McCarty, J. H.; Palmieri, D.; Saunus, J.; Lakhani, S.; Huang, S.; Sahin, A. A.; Aldape, K. D.; Steeg, P. S.; Yu, D. Microenvironment-induced PTEN loss by exosomal microRNA primes brain metastasis outgrowth. Nature 2015, 527((7576)), 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Baena, F. J.; Marquez-Galera, A.; Ballesteros-Martinez, P.; Castillo, A.; Diaz, E.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Lopez-Atalaya, J. P.; Sanchez-Laorden, B. Microglial reprogramming enhances antitumor immunity and immunotherapy response in melanoma brain metastases. Cancer Cell 2025, 43((3)), 413–427.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, G. K.; Poorman, K.; Saul, M.; O'Day, S.; Farma, J. M.; Olszanski, A. J.; Gordon, M. S.; Thomas, J. S.; Eisenberg, B.; Flaherty, L.; Weise, A.; Daveluy, S.; Gibney, G.; Atkins, M. B.; Vanderwalde, A. Molecular profiling of melanoma brain metastases compared to primary cutaneous melanoma and to extracranial metastases. Oncotarget 2020, 11((33)), 3118–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, J.; Melms, J. C.; Amin, A. D.; Wang, Y.; Caprio, L. A.; Karz, A.; Tagore, S.; Barrera, I.; Ibarra-Arellano, M. A.; Andreatta, M.; Fullerton, B. T.; Gretarsson, K. H.; Sahu, V.; Mangipudy, V. S.; Nguyen, T. T. T.; Nair, A.; Rogava, M.; Ho, P.; Koch, P. D.; Banu, M.; Humala, N.; Mahajan, A.; Walsh, Z. H.; Shah, S. B.; Vaccaro, D. H.; Caldwell, B.; Mu, M.; Wunnemann, F.; Chazotte, M.; Berhe, S.; Luoma, A. M.; Driver, J.; Ingham, M.; Khan, S. A.; Rapisuwon, S.; Slingluff, C. L., Jr.; Eigentler, T.; Rocken, M.; Carvajal, R.; Atkins, M. B.; Davies, M. A.; Agustinus, A.; Bakhoum, S. F.; Azizi, E.; Siegelin, M.; Lu, C.; Carmona, S. J.; Hibshoosh, H.; Ribas, A.; Canoll, P.; Bruce, J. N.; Bi, W. L.; Agrawal, P.; Schapiro, D.; Hernando, E.; Macosko, E. Z.; Chen, F.; Schwartz, G. K.; Izar, B. Dissecting the treatment-naive ecosystem of human melanoma brain metastasis. Cell 2022, 185((14)), 2591–2608 e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (NCCN), N. C. C. N., NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: melanoma. 2026, Version 1.2026.

- Gaviani, P.; Mullins, M. E.; Braga, T. A.; Hedley-Whyte, E. T.; Halpern, E. F.; Schaefer, P. S.; Henson, J. W. Improved detection of metastatic melanoma by T2*-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006, 27((3)), 605–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Escott, E. J. A variety of appearances of malignant melanoma in the head: a review. Radiographics 2001, 21((3)), 625–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venur, V. A.; Funchain, P.; Kotecha, R.; Chao, S. T.; Ahluwalia, M. S. Changing Treatment Paradigms for Brain Metastases From Melanoma-Part 1: Diagnosis, Prognosis, Symptom Control, and Local Treatment. Oncology (Williston Park) 2017, 31((8)), 602–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, H. W.; Hall, L. T. Molecular Imaging of Brain Metastases with PET. In Metastasis; Sergi, C. M., Ed. Exon Publications Copyright: The Authors.: Brisbane (AU); The authors confirm that the materials included in this chapter do not violate copyright laws. Where relevant, appropriate permissions have been obtained from the original copyright holder(s), and all original sources have been appropriately acknowledged or referenced., 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tabassum, M.; Suman, A. A.; Suero Molina, E.; Pan, E.; Di Ieva, A.; Liu, S. Radiomics and Machine Learning in Brain Tumors and Their Habitat: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.; Jacobs, M. A. Radiomics: a new application from established techniques. Expert Rev Precis Med Drug Dev 2016, 1((2)), 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, E.; Giordani, E.; Ziccheddu, G.; Falcone, I.; Giacomini, P.; Fanciulli, M.; Russillo, M.; Cerro, M.; Ciliberto, G.; Morrone, A.; Guerrisi, A.; Valenti, F. Metastatic Melanoma: Liquid Biopsy as a New Precision Medicine Approach. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24((4)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, P.; Buszka, K.; Zabel, M.; Nowicki, M.; Alix-Panabières, C.; Budna-Tukan, J. Liquid Biopsy in Melanoma: Significance in Diagnostics, Prediction and Treatment Monitoring. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22((18)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Mader, S.; Pantel, K. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in circulating tumor cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2017, 95((2)), 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forschner, A.; Battke, F.; Hadaschik, D.; Schulze, M.; Weißgraeber, S.; Han, C. T.; Kopp, M.; Frick, M.; Klumpp, B.; Tietze, N.; Amaral, T.; Martus, P.; Sinnberg, T.; Eigentler, T.; Keim, U.; Garbe, C.; Döcker, D.; Biskup, S. Tumor mutation burden and circulating tumor DNA in combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma - results of a prospective biomarker study. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7((1)), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. M.; Xu, Y. M.; Huang, L. F.; Wang, X. Z. Exosomes: novel biomarkers for clinical diagnosis. ScientificWorldJournal 2015, 2015, 657086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedaeinia, R.; Manian, M.; Jazayeri, M. H.; Ranjbar, M.; Salehi, R.; Sharifi, M.; Mohaghegh, F.; Goli, M.; Jahednia, S. H.; Avan, A.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. Circulating exosomes and exosomal microRNAs as biomarkers in gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 2017, 24((2)), 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of exosomes in cancer. J Clin Invest 2016, 126((4)), 1208–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namee, N. M.; O'Driscoll, L. Extracellular vesicles and anti-cancer drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2018, 1870((2)), 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesi, G.; Philippidou, D.; Kozar, I.; Kim, Y. J.; Bernardin, F.; Van Niel, G.; Wienecke-Baldacchino, A.; Felten, P.; Letellier, E.; Dengler, S.; Nashan, D.; Haan, C.; Kreis, S. A new ALK isoform transported by extracellular vesicles confers drug resistance to melanoma cells. Mol Cancer 2018, 17((1)), 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, L. J.; Behren, A.; Coleman, B.; Greening, D. W.; Hill, A. F.; Cebon, J. Intercellular Resistance to BRAF Inhibition Can Be Mediated by Extracellular Vesicle-Associated PDGFRβ. Neoplasia 2017, 19((11)), 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amolegbe, S. M.; Johnston, N. C.; Ambrosi, A.; Ganguly, A.; Howcroft, T. K.; Kuo, L. S.; Labosky, P. A.; Rudnicki, D. D.; Satterlee, J. S.; Tagle, D. A.; Happel, C. Extracellular RNA communication: A decade of NIH common fund support illuminates exRNA biology. J Extracell Vesicles 2025, 14((1)), e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthew, R. W.; Sontheimer, E. J. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 2009, 136((4)), 642–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, G. Argonaute proteins: functional insights and emerging roles. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14((7)), 447–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieff, M. D.; Lo, S. N.; Scolyer, R. A.; Heaton, M. J.; Nobes, J. P.; Snelling, A. P.; Carr, M. J.; Nessim, C.; Wade, R.; Peach, A. H.; Kisyova, R.; Mason, J.; Wilson, E. D.; Nolan, G.; Pritchard Jones, R.; Johansson, I.; Olofsson Bagge, R.; Wright, L. J.; Patel, N. G.; Sondak, V. K.; Thompson, J. F.; Zager, J. S. Clinical Outcomes and Risk Stratification of Early-Stage Melanoma Micrometastases From an International Multicenter Study: Implications for the Management of American Joint Committee on Cancer IIIA Disease. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40((34)), 3940–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKie, R. M.; Reid, R.; Junor, B. Fatal melanoma transferred in a donated kidney 16 years after melanoma surgery. N Engl J Med 2003, 348((6)), 567–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xie, R.; Zeng, F.; Cai, H.; Lui, S.; Song, B.; Chen, L.; Wu, M. Advanced Imaging Techniques for Differentiating Pseudoprogression and Tumor Recurrence After Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 790674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Mei, R.; Yu, S.; Shou, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, K.; Qiu, Z.; Xie, T.; Sui, X. Emerging Technologies for the Detection of Cancer Micrometastasis. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2022, 21, 15330338221100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaebe, K.; Li, A. Y.; Das, S. Clinical Biomarkers for Early Identification of Patients with Intracranial Metastatic Disease. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.; Lee, D.; Shim, H. Metabolic positron emission tomography imaging in cancer detection and therapy response. Semin Oncol 2011, 38((1)), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galldiks, N.; Unterrainer, M.; Judov, N.; Stoffels, G.; Rapp, M.; Lohmann, P.; Vettermann, F.; Dunkl, V.; Suchorska, B.; Tonn, J. C.; Kreth, F. W.; Fink, G. R.; Bartenstein, P.; Langen, K. J.; Albert, N. L. Photopenic defects on O-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET: clinical relevance in glioma patients. Neuro Oncol 2019, 21((10)), 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J. F.; Williams, G. J.; Hong, A. M. Radiation therapy for melanoma brain metastases: a systematic review. Radiol Oncol 2022, 56((3)), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Garcia Moreira, C. G.; Iaboni, E.; Tripodo, M.; Ferrarotto, R.; Abbritti, R. V.; Conte, L.; Caffo, M. Tumor Microenvironment in Melanoma Brain Metastasis: A New Potential Target? Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26((11)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, S.; Chen, Y. A.; Zhao, X.; Weber, J. L.; Benedict, J. J.; Mulé, J. J.; Smalley, K. S.; Weber, J. S.; Zager, J. S.; Forsyth, P. A.; Sondak, V. K.; Gibney, G. T. Improved survival of patients with melanoma brain metastases in the era of targeted BRAF and immune checkpoint therapies. Cancer 2018, 124((2)), 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, C. I.; Ferguson, S. D. Surgical Management of Brain Metastasis: Challenges and Nuances. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 847110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proescholdt, M. A.; Schödel, P.; Doenitz, C.; Pukrop, T.; Höhne, J.; Schmidt, N. O.; Schebesch, K.-M. The Management of Brain Metastases—Systematic Review of Neurosurgical Aspects. Cancers 2021, Vol. 13, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W. A.; Das, J. M. Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS) and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Manon, R.; O'Neill, A.; Knisely, J.; Werner-Wasik, M.; Lazarus, H. M.; Wagner, H.; Gilbert, M.; Mehta, M. Phase II trial of radiosurgery for one to three newly diagnosed brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and sarcoma: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study (E 6397). J Clin Oncol 2005, 23((34)), 8870–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrasheed, A. S.; Aleid, A. M.; Alharbi, R. A.; Alamer, M. A.; Alomran, K. A.; Bin Maan, S. A.; Almalki, S. F. Stereotactic radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for intracranial metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Neurol Int 2025, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amseian, G.; Aya, F.; Pineda, C.; González-Ortiz, S.; Mora, J. A.; Olondo, M. L.; Perissinotti, A.; Caballero, G. A.; Aldecoa, I.; Mezquita, L.; Puig, J.; Arance, A.; Bargalló, N.; Oleaga, L. Assessing brain metastasis response to immunotherapy: a pictorial review of atypical responses and intracranial adverse events. Insights Imaging 2025, 16((1)), 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rades, D.; Heisterkamp, C.; Huttenlocher, S.; Bohlen, G.; Dunst, J.; Haatanen, T.; Schild, S. E. Dose escalation of whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases from melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010, 77((2)), 537–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, M.; Beal, K.; Carvajal, R.; Kaley, T. J. Whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastases from melanoma. CNS Oncol 2014, 3((6)), 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, S. S.; Kirkwood, J. M.; Gore, M.; Dreno, B.; Thatcher, N.; Czarnetski, B.; Atkins, M.; Buzaid, A.; Skarlos, D.; Rankin, E. M. Temozolomide for the treatment of brain metastases associated with metastatic melanoma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2004, 22((11)), 2101–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Atkinson, H.; A'Hern, R.; Lorentzos, A.; Gore, M. E. A phase II study of the sequential administration of dacarbazine and fotemustine in the treatment of cerebral metastases from malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 1994, 30a((14)), 2093–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A. M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Grob, J. J.; Dummer, R.; Wolchok, J. D.; Schmidt, H.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ascierto, P. A.; Richards, J. M.; Lebbé, C.; Ferraresi, V.; Smylie, M.; Weber, J. S.; Maio, M.; Bastholt, L.; Mortier, L.; Thomas, L.; Tahir, S.; Hauschild, A.; Hassel, J. C.; Hodi, F. S.; Taitt, C.; de Pril, V.; de Schaetzen, G.; Suciu, S.; Testori, A. Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. N Engl J Med 2016, 375((19)), 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. P.; Othus, M.; Chen, Y.; Wright, G. P.; Yost, K. J.; Hyngstrom, J. R.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Lao, C. D.; Fecher, L. A.; Truong, T.-G.; Eisenstein, J. L.; Chandra, S.; Sosman, J. A.; Kendra, K. L.; Wu, R. C.; Devoe, C. E.; Deutsch, G. B.; Hegde, A.; Khalil, M.; Mangla, A.; Reese, A. M.; Ross, M. I.; Poklepovic, A. S.; Phan, G. Q.; Onitilo, A. A.; Yasar, D. G.; Powers, B. C.; Doolittle, G. C.; In, G. K.; Kokot, N.; Gibney, G. T.; Atkins, M. B.; Shaheen, M.; Warneke, J. A.; Ikeguchi, A.; Najera, J. E.; Chmielowski, B.; Crompton, J. G.; Floyd, J. D.; Hsueh, E.; Margolin, K. A.; Chow, W. A.; Grossmann, K. F.; Dietrich, E.; Prieto, V. G.; Lowe, M. C.; Buchbinder, E. I.; Kirkwood, J. M.; Korde, L.; Moon, J.; Sharon, E.; Sondak, V. K.; Ribas, A. Neoadjuvant–Adjuvant or Adjuvant-Only Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388((9)), 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelbaum, M. A.; Brown, P. D.; Messersmith, H.; Brastianos, P. K.; Burri, S.; Cahill, D.; Dunn, I. F.; Gaspar, L. E.; Gatson, N. T. N.; Gondi, V.; Jordan, J. T.; Lassman, A. B.; Maues, J.; Mohile, N.; Redjal, N.; Stevens, G.; Sulman, E.; van den Bent, M.; Wallace, H. J.; Weinberg, J. S.; Zadeh, G.; Schiff, D. Treatment for Brain Metastases: ASCO-SNO-ASTRO Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40((5)), 492–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G. V.; Trefzer, U.; Davies, M. A.; Kefford, R. F.; Ascierto, P. A.; Chapman, P. B.; Puzanov, I.; Hauschild, A.; Robert, C.; Algazi, A.; Mortier, L.; Tawbi, H.; Wilhelm, T.; Zimmer, L.; Switzky, J.; Swann, S.; Martin, A.-M.; Guckert, M.; Goodman, V.; Streit, M.; Kirkwood, J. M.; Schadendorf, D. Dabrafenib in patients with Val600Glu or Val600Lys BRAF-mutant melanoma metastatic to the brain (BREAK-MB): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2012, 13((11)), 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, M.; Suijkerbuijk, K. P. M.; Aarts, M. J. B.; van den Berkmortel, F. W. P. J.; Blank, C. U.; Blokx, W. A. M.; Boers-Sonderen, M. J.; Boreel, C. D. M.; de Groot, J. W. B.; Haanen, J. B. A. G.; Hospers, G. A. P.; Kapiteijn, E.; van Not, O. J.; Piersma, D.; Rikhof, B.; Stevense-den Boer, A. M.; van der Veldt, A. A. M.; Vreugdenhil, G.; Wouters, M. W. J. M.; van den Eertwegh, A. J. M. Efficacy of encorafenib plus binimetinib in patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma brain metastases: Results from the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry. European Journal of Cancer 2025, 223, 115514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez-Rodas, I.; Álvarez, A.; Arance, A.; Valduvieco, I.; Berciano-Guerrero, M.; Delgado, R.; Soria, A.; Lopez Campos, F.; Sánchez, P.; Romero, J. L.; Martin-Liberal, J.; Lucas, A.; Díaz-Beveridge, R.; Conde-Moreno, A. J.; Álamo de la Gala, M. D. C.; García-Castaño, A.; Prada, P. J.; González Cao, M.; Puertas, E.; Vidal, J.; Foro, P.; Aguado de la Rosa, C.; Corona, J. A.; Cerezuela-Fuentes, P.; López, P.; Luna, P.; Aymar, N.; Puértolas, T.; Sanagustín, P.; Berrocal, A. Encorafenib and binimetinib followed by radiotherapy for patients with BRAFV600-mutant melanoma and brain metastases (E-BRAIN/GEM1802 phase II study). Neuro Oncol 2024, 26((11)), 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolaney, S. M.; Sahebjam, S.; Le Rhun, E.; Bachelot, T.; Kabos, P.; Awada, A.; Yardley, D.; Chan, A.; Conte, P.; Diéras, V.; Lin, N. U.; Bear, M.; Chapman, S. C.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Anders, C. K. A Phase II Study of Abemaciclib in Patients with Brain Metastases Secondary to Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26((20)), 5310–5319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pardridge, W. M. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx 2005, 2((1)), 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gampa, G.; Vaidhyanathan, S.; Sarkaria, J. N.; Elmquist, W. F. Drug delivery to melanoma brain metastases: Can current challenges lead to new opportunities? Pharmacol Res 2017, 123, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Gong, Z.; Wu, D.; Ma, C.; Hou, L.; Niu, X.; Xu, T. Harnessing immunotherapy for brain metastases: insights into tumor–brain microenvironment interactions and emerging treatment modalities. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2023, 16((1)), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, V. P.; Tittarelli, A.; Retamal, M. A. Connexins in melanoma: Potential role of Cx46 in its aggressiveness. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2021, 34((5)), 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltantoyeh, T.; Akbari, B.; Karimi, A.; Mahmoodi Chalbatani, G.; Ghahri-Saremi, N.; Hadjati, J.; Hamblin, M. R.; Mirzaei, H. R. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma: Challenges and Road Ahead. Cells 2021, 10((6)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, R. E.; Zheng, Z.; Lagisetty, K. H.; Burns, W. R.; Tran, E.; Hewitt, S. M.; Abate-Daga, D.; Rosati, S. F.; Fine, H. A.; Ferrone, S.; Rosenberg, S. A.; Morgan, R. A. Multiple chimeric antigen receptors successfully target chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 in several different cancer histologies and cancer stem cells. J Immunother Cancer 2014, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B.; Harrer, D. C.; Schuler-Thurner, B.; Schaft, N.; Schuler, G.; Dörrie, J.; Uslu, U. The siRNA-mediated downregulation of PD-1 alone or simultaneously with CTLA-4 shows enhanced in vitro CAR-T-cell functionality for further clinical development towards the potential use in immunotherapy of melanoma. Exp Dermatol 2018, 27((7)), 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoo, K.; Inagaki, R.; Fujiwara, K.; Sasawatari, S.; Kamigaki, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Okada, N. Immunological quality and performance of tumor vessel-targeting CAR-T cells prepared by mRNA-EP for clinical research. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2016, 3, 16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, L.; Wei, H.; Zhao, S.; Zhong, K.; Mu, M.; Huang, C.; Jiang, C.; Xu, J.; Guo, G.; Zhou, L.; Tong, A. Tandem CAR-T cells targeting CD70 and B7-H3 exhibit potent preclinical activity against multiple solid tumors. Theranostics 2020, 10((17)), 7622–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, H. L.; Kohlhapp, F. J.; Zloza, A. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015, 14((9)), 642–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andtbacka, R. H.; Kaufman, H. L.; Collichio, F.; Amatruda, T.; Senzer, N.; Chesney, J.; Delman, K. A.; Spitler, L. E.; Puzanov, I.; Agarwala, S. S.; Milhem, M.; Cranmer, L.; Curti, B.; Lewis, K.; Ross, M.; Guthrie, T.; Linette, G. P.; Daniels, G. A.; Harrington, K.; Middleton, M. R.; Miller, W. H., Jr.; Zager, J. S.; Ye, Y.; Yao, B.; Li, A.; Doleman, S.; VanderWalde, A.; Gansert, J.; Coffin, R. S. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33((25)), 2780–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletneky, K.; Huesing, J.; Rommelaere, J.; Schlehofer, J. R.; Leuchs, B.; Dahm, M.; Krebs, O.; von Knebel Doeberitz, M.; Huber, B.; Hajda, J. Phase I/IIa study of intratumoral/intracerebral or intravenous/intracerebral administration of Parvovirus H-1 (ParvOryx) in patients with progressive primary or recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: ParvOryx01 protocol. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, F.; Xiong, M.; Yang, H.; Lin, W.; Xie, Y.; Xi, H.; Xue, Q.; Ye, T.; Yu, L. Repurposing of antipsychotic trifluoperazine for treating brain metastasis, lung metastasis and bone metastasis of melanoma by disrupting autophagy flux. Pharmacol Res 2021, 163, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Wu, M.; Ma, H.; Li, S.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y. Repurposing fluphenazine to suppress melanoma brain, lung and bone metastasis by inducing G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and disrupting autophagic flux. Clin Exp Metastasis 2023, 40((2)), 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Jiang, L.; Maldonato, B. J.; Wang, Y.; Holderfield, M.; Aronchik, I.; Winters, I. P.; Salman, Z.; Blaj, C.; Menard, M.; Brodbeck, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, X.; Rosen, M. J.; Gindin, Y.; Lee, B. J.; Evans, J. W.; Chang, S.; Wang, Z.; Seamon, K. J.; Parsons, D.; Cregg, J.; Marquez, A.; Tomlinson, A. C. A.; Yano, J. K.; Knox, J. E.; Quintana, E.; Aguirre, A. J.; Arbour, K. C.; Reed, A.; Gustafson, W. C.; Gill, A. L.; Koltun, E. S.; Wildes, D.; Smith, J. A. M.; Wang, Z.; Singh, M. Translational and Therapeutic Evaluation of RAS-GTP Inhibition by RMC-6236 in RAS-Driven Cancers. Cancer Discov 2024, 14((6)), 994–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holderfield, M.; Lee, B. J.; Jiang, J.; Tomlinson, A.; Seamon, K. J.; Mira, A.; Patrucco, E.; Goodhart, G.; Dilly, J.; Gindin, Y.; Dinglasan, N.; Wang, Y.; Lai, L. P.; Cai, S.; Jiang, L.; Nasholm, N.; Shifrin, N.; Blaj, C.; Shah, H.; Evans, J. W.; Montazer, N.; Lai, O.; Shi, J.; Ahler, E.; Quintana, E.; Chang, S.; Salvador, A.; Marquez, A.; Cregg, J.; Liu, Y.; Milin, A.; Chen, A.; Ziv, T. B.; Parsons, D.; Knox, J. E.; Klomp, J. E.; Roth, J.; Rees, M.; Ronan, M.; Cuevas-Navarro, A.; Hu, F.; Lito, P.; Santamaria, D.; Aguirre, A. J.; Waters, A. M.; Der, C. J.; Ambrogio, C.; Wang, Z.; Gill, A. L.; Koltun, E. S.; Smith, J. A. M.; Wildes, D.; Singh, M. Concurrent inhibition of oncogenic and wild-type RAS-GTP for cancer therapy. Nature 2024, 629((8013)), 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazan, J.; Turapov, T.; Kircher, D. A.; Stanley, K. A.; Culver, K.; Medellin, A. P.; Field, M. N.; Parkman, G. L.; Colman, H.; Coma, S.; Pachter, J. A.; Holmen, S. L. Combined inhibition of focal adhesion kinase and RAF/MEK elicits synergistic inhibition of melanoma growth and reduces metastases. Cell Rep Med 2025, 6((2)), 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Krebs, M. G.; Greystoke, A.; Garces, A. I.; Perez, V. S.; Terbuch, A.; Shinde, R.; Caldwell, R.; Grochot, R.; Rouhifard, M.; Ruddle, R.; Gurel, B.; Swales, K.; Tunariu, N.; Prout, T.; Parmar, M.; Symeonides, S.; Rekowski, J.; Yap, C.; Sharp, A.; Paschalis, A.; Lopez, J.; Minchom, A.; de Bono, J. S.; Banerji, U. Defactinib with avutometinib in patients with solid tumors: the phase 1 FRAME trial. Nature Medicine 2025, 31((9)), 3074–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, H.; Holmen, S. L. Defactinib and Avutometinib, With or Without Encorafenib, for the Treatment of Patients With Brain Metastases From Cutaneous Melanoma (DETERMINE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06194929 (12/26/2025).

- Schreurs, L. D.; Vom Stein, A. F.; Jünger, S. T.; Timmer, M.; Noh, K. W.; Buettner, R.; Kashkar, H.; Neuschmelting, V.; Goldbrunner, R.; Nguyen, P. H. The immune landscape in brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol 2025, 27((1)), 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankowski, R.; Böttcher, C.; Masuda, T.; Geirsdottir, L.; Sagar; Sindram, E.; Seredenina, T.; Muhs, A.; Scheiwe, C.; Shah, M. J.; Heiland, D. H.; Schnell, O.; Grün, D.; Priller, J.; Prinz, M. Mapping microglia states in the human brain through the integration of high-dimensional techniques. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22((12)), 2098–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, R. L.; Klemm, F.; Akkari, L.; Pyonteck, S. M.; Sevenich, L.; Quail, D. F.; Dhara, S.; Simpson, K.; Gardner, E. E.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C. A.; Brennan, C. W.; Tabar, V.; Gutin, P. H.; Joyce, J. A. Macrophage Ontogeny Underlies Differences in Tumor-Specific Education in Brain Malignancies. Cell Rep 2016, 17((9)), 2445–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.; Michels, B.; Niesel, K.; Stein, S.; Farin, H.; Rödel, F.; Sevenich, L. Cellular and Molecular Changes of Brain Metastases-Associated Myeloid Cells during Disease Progression and Therapeutic Response. iScience 2020, 23((6)), 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Karschnia, P.; von Mücke-Heim, I. A.; Mulazzani, M.; Zhou, X.; Blobner, J.; Mueller, N.; Teske, N.; Dede, S.; Xu, T.; Thon, N.; Ishikawa-Ankerhold, H.; Straube, A.; Tonn, J. C.; von Baumgarten, L. In vivo two-photon characterization of tumor-associated macrophages and microglia (TAM/M) and CX3CR1 during different steps of brain metastasis formation from lung cancer. Neoplasia 2021, 23((11)), 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorger, M.; Felding-Habermann, B. Capturing changes in the brain microenvironment during initial steps of breast cancer brain metastasis. Am J Pathol 2010, 176((6)), 2958–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, F.; Möckl, A.; Salamero-Boix, A.; Alekseeva, T.; Schäffer, A.; Schulz, M.; Niesel, K.; Maas, R. R.; Groth, M.; Elie, B. T.; Bowman, R. L.; Hegi, M. E.; Daniel, R. T.; Zeiner, P. S.; Zinke, J.; Harter, P. N.; Plate, K. H.; Joyce, J. A.; Sevenich, L. Compensatory CSF2-driven macrophage activation promotes adaptive resistance to CSF1R inhibition in breast-to-brain metastasis. Nat Cancer 2021, 2((10)), 1086–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebel, E.; Kapolou, K.; Unger, S.; Núñez, N. G.; Utz, S.; Rushing, E. J.; Regli, L.; Weller, M.; Greter, M.; Tugues, S.; Neidert, M. C.; Becher, B. Single-Cell Mapping of Human Brain Cancer Reveals Tumor-Specific Instruction of Tissue-Invading Leukocytes. Cell 2020, 181((7)), 1626–1642.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, F.; Maas, R. R.; Bowman, R. L.; Kornete, M.; Soukup, K.; Nassiri, S.; Brouland, J. P.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C. A.; Brennan, C.; Tabar, V.; Gutin, P. H.; Daniel, R. T.; Hegi, M. E.; Joyce, J. A. Interrogation of the Microenvironmental Landscape in Brain Tumors Reveals Disease-Specific Alterations of Immune Cells. Cell 2020, 181((7)), 1643–1660.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, R.; Yong, V. W. Microglia-T cell conversations in brain cancer progression. Trends Mol Med 2022, 28((11)), 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, K. T.; Blake, K.; Longworth, A.; Coburn, M. A.; Insua-Rodríguez, J.; McMullen, T. P.; Nguyen, Q. H.; Ma, D.; Lev, T.; Hernandez, G. A.; Oganyan, A. K.; Orujyan, D.; Edwards, R. A.; Pridans, C.; Green, K. N.; Villalta, S. A.; Blurton-Jones, M.; Lawson, D. A. Microglia promote anti-tumour immunity and suppress breast cancer brain metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2023, 25((12)), 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischnewski, V.; Maas, R. R.; Aruffo, P. G.; Soukup, K.; Galletti, G.; Kornete, M.; Galland, S.; Fournier, N.; Lilja, J.; Wirapati, P.; Lourenco, J.; Scarpa, A.; Daniel, R. T.; Hottinger, A. F.; Brouland, J. P.; Losurdo, A.; Voulaz, E.; Alloisio, M.; Hegi, M. E.; Lugli, E.; Joyce, J. A. Phenotypic diversity of T cells in human primary and metastatic brain tumors revealed by multiomic interrogation. Nat Cancer 2023, 4((6)), 908–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, L. Immunotherapy revolutionizing brain metastatic cancer treatment: personalized strategies for transformative outcomes. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1418580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, J.; Agardy, D. A.; Kumar, S.; Kourtesakis, A.; Boschert, T.; Jahne, K.; Breckwoldt, M. O.; Bunse, L.; Wick, W.; Davies, M. A.; Platten, M.; Bunse, T. Tumoral Interferon Beta Induces an Immune-Stimulatory Phenotype in Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Melanoma Brain Metastases. Cancer Res Commun 2024, 4((8)), 2189–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Qian, Y.; Xu, G.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Z. Long-term characterization of activated microglia/macrophages facilitating the development of experimental brain metastasis through intravital microscopic imaging. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16((1)), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbenishty, A.; Gadrich, M.; Cottarelli, A.; Lubart, A.; Kain, D.; Amer, M.; Shaashua, L.; Glasner, A.; Erez, N.; Agalliu, D.; Mayo, L.; Ben-Eliyahu, S.; Blinder, P. Prophylactic TLR9 stimulation reduces brain metastasis through microglia activation. PLoS Biol 2019, 17((3)), e2006859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economopoulos, V.; Pannell, M.; Johanssen, V. A.; Scott, H.; Andreou, K. E.; Larkin, J. R.; Sibson, N. R. Inhibition of Anti-Inflammatory Macrophage Phenotype Reduces Tumour Growth in Mouse Models of Brain Metastasis. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 850656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18((3)), 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, A.; Jenner, A. L.; Karimi, E.; Fiset, B.; Quail, D. F.; Walsh, L. A.; Craig, M. Agent-Based Modelling Reveals the Role of the Tumor Microenvironment on the Short-Term Success of Combination Temozolomide/Immune Checkpoint Blockade to Treat Glioblastoma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2023, 387((1)), 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, I.; Chen, Z.; Phadke, M.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Wyatt, C.; Evernden, B.; Messina, J. L.; Sarnaik, A.; Sondak, V. K.; Zhang, C.; Law, V.; Tran, N.; Etame, A.; Macaulay, R. J. B.; Eroglu, Z.; Forsyth, P. A.; Rodriguez, P. C.; Chen, Y. A.; Smalley, K. S. M. Single-Cell Characterization of the Immune Microenvironment of Melanoma Brain and Leptomeningeal Metastases. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27((14)), 4109–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawbi, H. A.; Schadendorf, D.; Lipson, E. J.; Ascierto, P. A.; Matamala, L.; Castillo Gutiérrez, E.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H. J.; Lao, C. D.; De Menezes, J. J.; Dalle, S.; Arance, A.; Grob, J. J.; Srivastava, S.; Abaskharoun, M.; Hamilton, M.; Keidel, S.; Simonsen, K. L.; Sobiesk, A. M.; Li, B.; Hodi, F. S.; Long, G. V. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2022, 386((1)), 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Ciuleanu, T. E.; Lee, J. S.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Kim, S. W.; Mahave, M.; Alexandru, A.; Peters, S.; Pluzanski, A.; Caro, R. B.; Linardou, H.; Burgers, J. A.; Nishio, M.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Azuma, K.; Axelrod, R.; Paz-Ares, L. G.; Ramalingam, S. S.; Borghaei, H.; O'Byrne, K. J.; Li, L.; Bushong, J.; Gupta, R. G.; Grootendorst, D. J.; Eccles, L. J.; Brahmer, J. R. Systemic and Intracranial Outcomes With First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Metastatic NSCLC and Baseline Brain Metastases From CheckMate 227 Part 1. J Thorac Oncol 2023, 18((8)), 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, E. E.; Mueller, K. L.; Adams, D. J.; Anandasabapathy, N.; Aplin, A. E.; Bertolotto, C.; Bosenberg, M.; Ceol, C. J.; Burd, C. E.; Chi, P.; Herlyn, M.; Holmen, S. L.; Karreth, F. A.; Kaufman, C. K.; Khan, S.; Kobold, S.; Leucci, E.; Levy, C.; Lombard, D. B.; Lund, A. W.; Marie, K. L.; Marine, J. C.; Marais, R.; McMahon, M.; Robles-Espinoza, C. D.; Ronai, Z. A.; Samuels, Y.; Soengas, M. S.; Villanueva, J.; Weeraratna, A. T.; White, R. M.; Yeh, I.; Zhu, J.; Zon, L. I.; Hurlbert, M. S.; Merlino, G. Melanoma models for the next generation of therapies. Cancer Cell 2021, 39((5)), 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. P.; Merlino, G.; Van Dyke, T. Preclinical mouse cancer models: a maze of opportunities and challenges. Cell 2015, 163((1)), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühwein, H.; Paul, N. W. Lost in translation?" Animal research in the era of precision medicine. J Transl Med 2025, 23((1)), 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martić-Kehl, M. I.; Schibli, R.; Schubiger, P. A. Can animal data predict human outcome? Problems and pitfalls of translational animal research. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2012, 39((9)), 1492–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodspeed, A.; Heiser, L. M.; Gray, J. W.; Costello, J. C. Tumor-Derived Cell Lines as Molecular Models of Cancer Pharmacogenomics. Mol Cancer Res 2016, 14((1)), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabelli, P.; Coppola, L.; Salvatore, M. Cancer Cell Lines Are Useful Model Systems for Medical Research. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11((8)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Cai, C.; Zhang, H.; Shen, H.; Han, Y. Patient-derived xenograft models in cancer therapy: technologies and applications. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8((1)), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, I.; Kulms, D. A 3D Organotypic Melanoma Spheroid Skin Model. J Vis Exp 2018, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, D. B.; Reis, R. L.; Pirraco, R. P. Modelling the complex nature of the tumor microenvironment: 3D tumor spheroids as an evolving tool. J Biomed Sci 2024, 31((1)), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangani, S.; Kremmydas, S.; Karamanos, N. K. Mimicking the Complexity of Solid Tumors: How Spheroids Could Advance Cancer Preclinical Transformative Approaches. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17((7)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulou, K.; Koutsakis, C.; Piperigkou, Z.; Karamanos, N. K. Recreating the extracellular matrix: novel 3D cell culture platforms in cancer research. 2023, 290((22)), 5238–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, D.; Li, S.; Du, F.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Qin, J. Advances in engineered organoid models of skin for biomedical research. Burns Trauma 2025, 13, tkaf016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedellatif, S. E.; Hosni, R.; Waha, A.; Gielen, G. H.; Banat, M.; Hamed, M.; Güresir, E.; Fröhlich, A.; Sirokay, J.; Wulf, A. L.; Kristiansen, G.; Pietsch, T.; Vatter, H.; Hölzel, M.; Schneider, M.; Toma, M. I. Melanoma Brain Metastases Patient-Derived Organoids: An In Vitro Platform for Drug Screening. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16((8)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorel, L.; Perréard, M.; Florent, R.; Divoux, J.; Coffy, S.; Vincent, A.; Gaggioli, C.; Guasch, G.; Gidrol, X.; Weiswald, L.-B.; Poulain, L. Patient-derived tumor organoids: a new avenue for preclinical research and precision medicine in oncology. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024, 56((7)), 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedellatif, S.-E.; Hosni, R.; Waha, A.; Gielen, G. H.; Banat, M.; Hamed, M.; Güresir, E.; Fröhlich, A.; Sirokay, J.; Wulf, A.-L.; Kristiansen, G.; Pietsch, T.; Vatter, H.; Hölzel, M.; Schneider, M.; Toma, M. I. Melanoma Brain Metastases Patient-Derived Organoids: An In Vitro Platform for Drug Screening. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16((8)), 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, F.; Nesbit, M.; Hsu, M. Y.; Martin, B.; Van Belle, P.; Elder, D. E.; Schaumburg-Lever, G.; Garbe, C.; Walz, T. M.; Donatien, P.; Crombleholme, T. M.; Herlyn, M. Human melanoma progression in skin reconstructs: biological significance of bFGF. Am J Pathol 2000, 156((1)), 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fukunaga-Kalabis, M.; Herlyn, M. The three-dimensional human skin reconstruct model: a tool to study normal skin and melanoma progression. J Vis Exp 2011, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Lin, L.; Ma, Y.; Huang, W.; Luo, Q.; Wen, J. Single-cell transcriptomics profiling reveals cellular origins and molecular drivers underlying melanoma brain metastasis. PLOS ONE 2025, 20((11)), e0336502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In, G. K.; Ribeiro, J. R.; Yin, J.; Xiu, J.; Bustos, M. A.; Ito, F.; Chow, F.; Zada, G.; Hwang, L.; Salama, A. K. S.; Park, S. J.; Moser, J. C.; Darabi, S.; Domingo-Musibay, E.; Ascierto, M. L.; Margolin, K.; Lutzky, J.; Gibney, G. T.; Atkins, M. B.; Izar, B.; Hoon, D. S. B.; VanderWalde, A. M. Multi-omic profiling reveals discrepant immunogenic properties and a unique tumor microenvironment among melanoma brain metastases. npj Precision Oncology 2023, 7((1)), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M. A.; Liu, P.; McIntyre, S.; Kim, K. B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Hwu, W. J.; Hwu, P.; Bedikian, A. Prognostic factors for survival in melanoma patients with brain metastases. Cancer 2011, 117((8)), 1687–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkala, M. R.; Mullangi, S. Malignant Melanoma Metastatic to the Central Nervous System. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Valentini, V.; Boldrini, L.; Mariani, S.; Massaccesi, M. Role of radiation oncology in modern multidisciplinary cancer treatment. Mol Oncol 2020, 14((7)), 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. D.; Perlow, H. K.; Lehrer, E. J.; Wardak, Z.; Soliman, H. Novel radiotherapeutic strategies in the management of brain metastases: Challenging the dogma. Neuro Oncol 2024, 26((12) Suppl 2, S46–s55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. A.; Tang, M.; Shih, K. K.; Khan, M.; Pham, L.; De Moraes, A. R.; O'Brien, B. J.; Bassett, R.; Bruera, E. Characterization of patients with brain metastases referred to palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2024, 23((1)), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Colón, G. R.; Lim, M. Quality of Life and Role of Palliative and Supportive Care for Patients With Brain Metastases and Caregivers: A Review. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 806344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukuri, S. P.; Kaur, A.; Goyal, B.; Kukunoor, H. R.; Sahito, A. F.; Sachdeva, P.; Yerrapragada, G.; Elangovan, P.; Shariff, M. N.; Natarajan, T.; Janarthanan, J.; Richard, S.; Pallikaranai Venkatesaprasath, S.; Karuppiah, S. S.; Iyer, V. N.; Helgeson, S. A.; Arunachalam, S. P. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Liquid Biopsy and Radiomics in Early-Stage Lung Cancer Detection: A Precision Oncology Paradigm. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.; Angelin Rajan, R.; Balasubramaniyam, S.; Elumalai, K. AI-Enhanced Predictive Imaging in Precision Medicine: Advancing Diagnostic Accuracy and Personalized Treatment. iRADIOLOGY 2025, 3((4)), 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G. M.; Jalali, A.; Kircher, D. A.; Lee, W. C.; McQuade, J. L.; Haydu, L. E.; Joon, A. Y.; Reuben, A.; de Macedo, M. P.; Carapeto, F. C. L.; Yang, C.; Srivastava, A.; Ambati, C. R.; Sreekumar, A.; Hudgens, C. W.; Knighton, B.; Deng, W.; Ferguson, S. D.; Tawbi, H. A.; Glitza, I. C.; Gershenwald, J. E.; Vashisht Gopal, Y. N.; Hwu, P.; Huse, J. T.; Wargo, J. A.; Futreal, P. A.; Putluri, N.; Lazar, A. J.; DeBerardinis, R. J.; Marszalek, J. R.; Zhang, J.; Holmen, S. L.; Tetzlaff, M. T.; Davies, M. A. Molecular Profiling Reveals Unique Immune and Metabolic Features of Melanoma Brain Metastases. Cancer Discov 2019, 9((5)), 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, D.; Yu, Y.; Ma, W. Immunotherapy biomarkers in brain metastases: insights into tumor microenvironment dynamics. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1600261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, K.; Zemperligkos, P.; Politis, A.; Lani, E.; Gutierrez-Valencia, E.; Kotsantis, I.; Velonakis, G.; Boviatsis, E.; Stavrinou, L. C.; Kalyvas, A. Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Prognostic Applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Clinical Management of Brain Metastases (BMs). Brain Sci 2025, 15((7)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. The Role of Microglia in Brain Metastases: Mechanisms and Strategies. Aging Dis 2024, 15((1)), 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]