1. Introduction

Adamantane and cubane are structurally unique hydrocarbons that represent two extremes in molecular strain and reactivity. Adamantane is a rigid, diamondoid hydrocarbon characterized by a highly symmetrical, cage-like structure composed of fused cyclohexane rings, resulting in an almost strain-free framework. In contrast, cubane is a highly strained cubic hydrocarbon in which carbon–carbon bonds are constrained to approximately 90°, far from the ideal tetrahedral angle, leading to exceptional structural tension and high internal energy [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The fundamental chemical differences between adamantane and cubane arise from their distinct geometries. The fused cyclohexane framework of adamantane minimizes angular and torsional strain, conferring remarkable thermodynamic stability and low chemical reactivity. Reactions of adamantane typically occur at tertiary carbon atoms and require relatively harsh conditions. Conversely, cubane exhibits pronounced reactivity due to the severe angular strain within its carbon skeleton, making it a highly energetic molecule with unusual chemical behavior [

1,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Adamantane possesses low deformation energy, consistent with its stress-free structure, whereas cubane exhibits one of the highest deformation energies among known saturated hydrocarbons and diamondoids, estimated at approximately 159–166 kcal/mol. This exceptionally high strain energy leads to pronounced p-character in the C–C bonds and increased s-character in the C–H bonds of cubane, rendering its hydrogen atoms more acidic than those in adamantane or typical alkanes [

5,

8,

11,

12]. These electronic features underpin many of cubane’s distinctive chemical and physical properties.

From a medicinal chemistry perspective, the lipophilicity, conformational rigidity, and metabolic stability of the adamantane scaffold have made adamantane-containing compounds valuable pharmacophores, particularly in antiviral, antiparkinsonian, and neuroprotective drug development. Several clinically approved drugs incorporate the adamantane moiety, highlighting its pharmacological relevance.

In recent years, cubane has emerged as a promising structural motif in medicinal organic chemistry. Despite its high strain energy, cubane is remarkably stable under physiological conditions and has been increasingly explored as a rigid, three-dimensional bioisostere for benzene rings. Substitution of aromatic rings with cubane can improve metabolic stability, reduce toxicity, and offer novel spatial orientations for interactions with biological targets. The ability to functionalize each carbon atom of the cubane core provides unique opportunities for precise molecular design. However, challenges remain in the scalable synthesis and functional diversification of cubane derivatives [

13,

14,

15,

16].

In this review, we present a comparative analysis of the pharmacological potential of adamantane- and cubane-based compounds bearing various ligands. In addition, using the PASS (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances) computational platform, we evaluate and compare the predicted biological activities and therapeutic potential of cubane-containing molecules, with particular emphasis on their relevance to neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

2. Pharmacological Profile of Adamantane Derivatives

Adamantane and its derivatives were first identified in crude oil obtained from a field near Hodonín, Czechoslovakia, in 1933 [

17,

18,

19]. This discovery initiated the development of a distinct branch of organic and organometallic chemistry focused on adamantane-based compounds, which has since attracted sustained interest due to their unique structural and physicochemical properties [

1,

2,

11,

13].

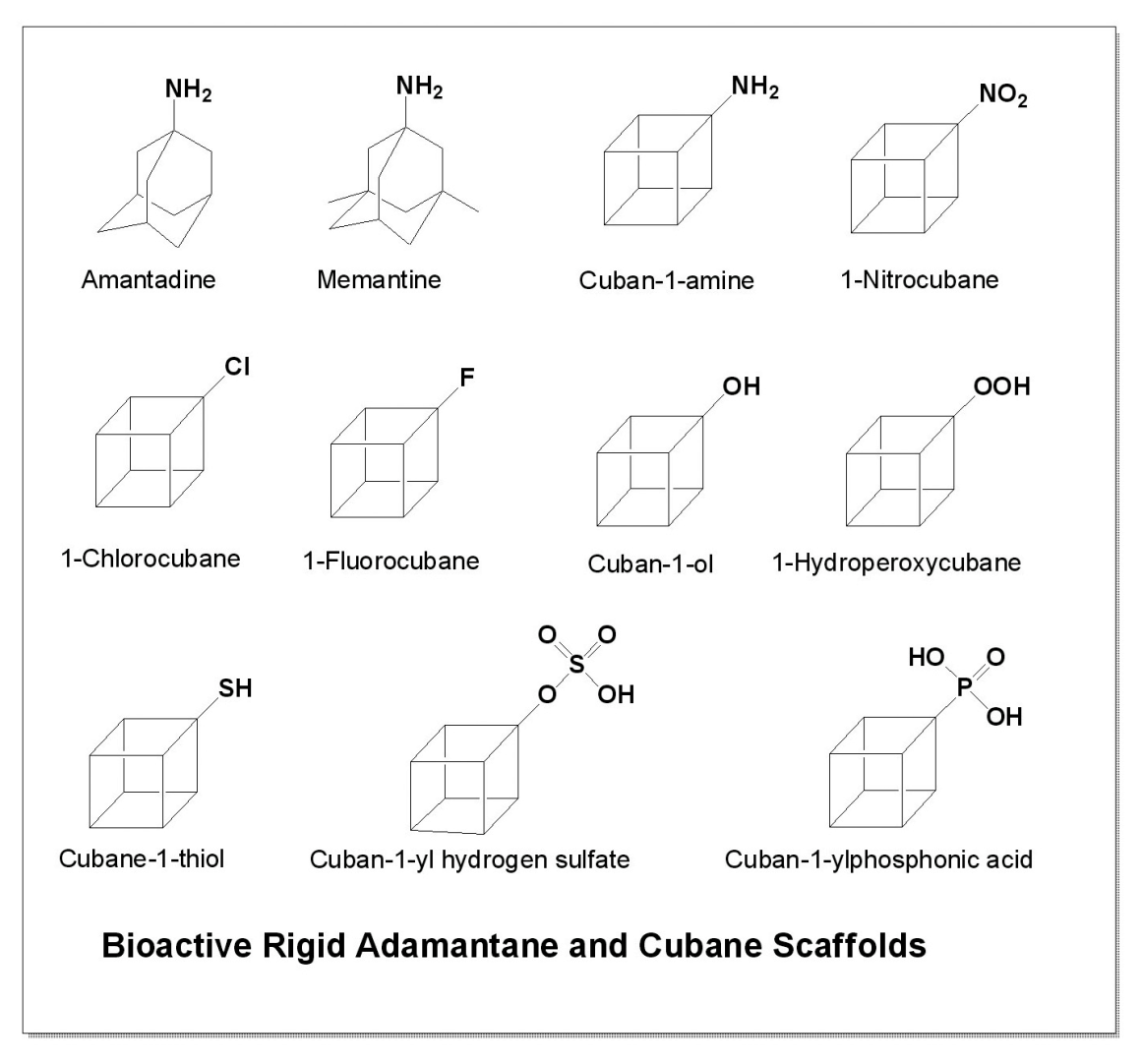

Naturally occurring compounds containing the adamantane skeleton (

Figure 1; biological activities summarized in

Table 1) have been isolated from a variety of plant species, marine invertebrates, and from the tissues of fish belonging to the family Tetraodontidae [

1,

19,

20]. These naturally derived adamantane-type metabolites have demonstrated a wide range of biologically relevant activities and, in several cases, have served as leads or templates for medicinal applications [

1,

2,

20]. To date, approximately 90 natural products containing an adamantane-type core have been reported, with the most biologically active representatives shown in

Figure 1 [

1,

20].

The term adamantane-type structure refers to a characteristic cage-like, tricyclic molecular scaffold composed of ten carbon atoms arranged in a rigid framework featuring four bridgehead and six bridging positions. This architecture closely resembles the carbon framework of diamond and confers exceptional conformational rigidity and stability. Such motifs are found not only in organic natural products, such as polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols (PPAPs), but also in inorganic systems, including organotetrel chalcogenide clusters, highlighting the broad structural and functional relevance of the adamantane topology across diverse chemical classes [

1,

2,

3,

13,

20].

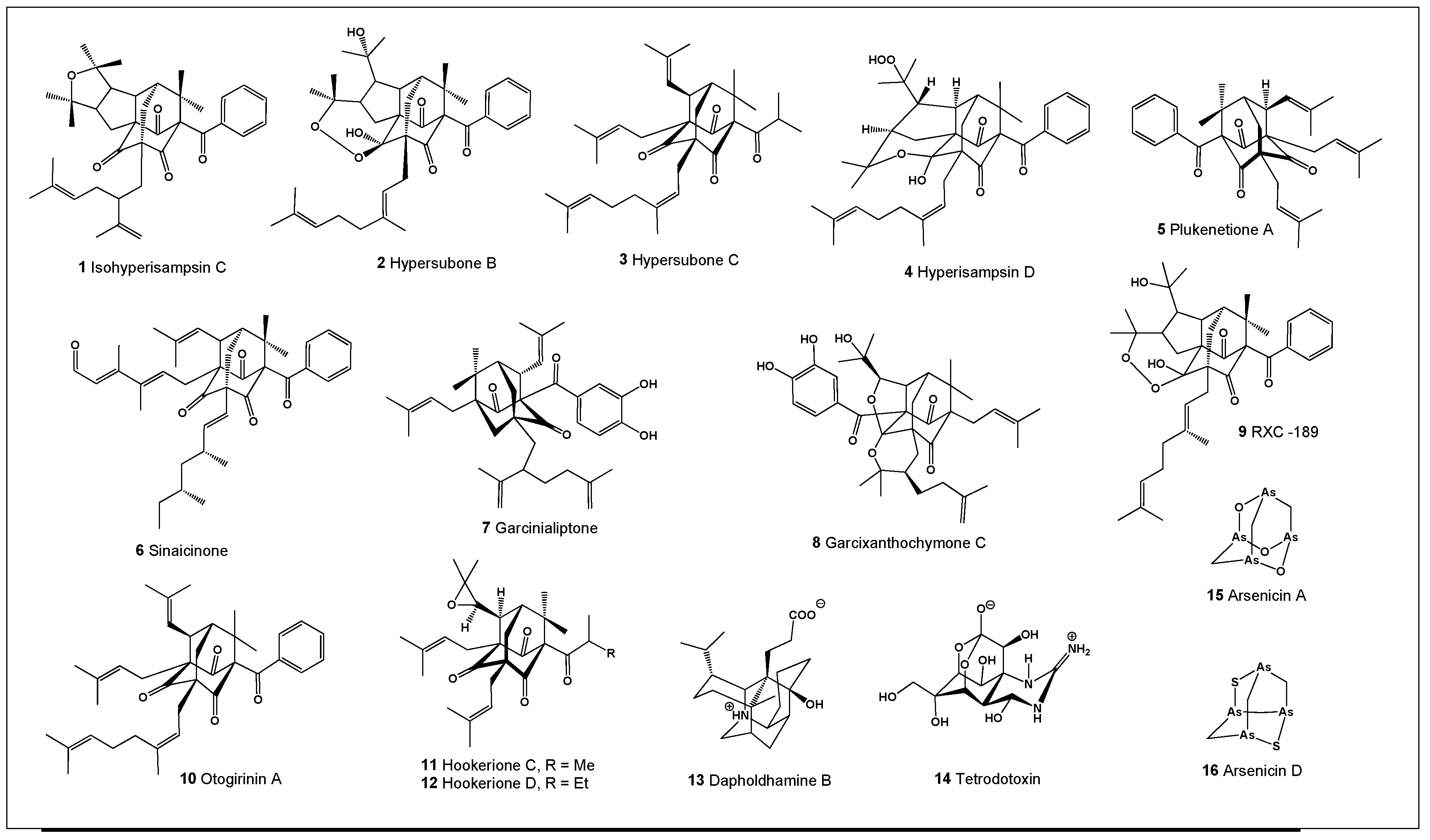

Plants of the genus

Garcinia are rich sources of pharmacologically active PPAPs and have long been used in traditional Chinese medicine. Various plant parts, including fruits, peels, flowers, leaves, bark, and stems, contain adamantane-type PPAPs such as the potent anticancer agent isohyperisampsin C (

1,

Figure 1), among others [

21].

Two adamantane-type PPAPs with unprecedented

seco-adamantane architectures and a tetracyclo[6.3.1.1³,¹⁰.0⁴,⁸]tridecane core, designated hypersubones B (

2) and C (

3), were isolated from Hypericum subsessile. Both compounds exhibited significant cytotoxicity against four human cancer cell lines in vitro, with IC₅₀ values ranging from 0.07 to 7.52 μM [

22]. In addition, hyperisampsin D (

4), isolated from the fruits of

Hypericum sampsonii together with analogues (

2 and

3), showed anticancer activity against human tumor cell lines SGC-7901, HepG2, and HCT-116 [

23].

Plukenetione A (

5) is an unusual adamantane-like member of the polyisoprenylated acylphloroglucinol family, originally isolated from

Clusia plukenetii and

Cuban propolis. This compound exhibits antitumor activity by inducing G₀/G₁ cell cycle arrest and DNA fragmentation in colon cancer cells and may also possess antiviral properties through inhibition of virus-associated enzymes [

24].

Sinaicinone (

6), isolated from the aerial parts of the Egyptian medicinal plant

Hypericum sinaicum, has demonstrated notable anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities [

25]. Garcinialiptone (

7), obtained from the fruits of

Garcinia subelliptica, exhibited cytotoxic activity against several human tumor cell lines, including A549, DU145, KB, and vincristine-resistant KB cells [

26].

Garcixanthochymone C (

8) was isolated from

Garcinia xanthochymus, a tropical fruit tree native to Southeast Asia whose fruits are traditionally used to treat biliary disorders, diarrhea, and dysentery. The compound showed antiproliferative activity against HepG2, A549, SGC7901, and MCF-7 cancer cell lines, supporting the potential of

G. xanthochymus fruit extracts as cancer-preventive agents [

27]. A highly cytotoxic compound designated RXC-189 (

9) was also isolated from the fruits of

Hypericum subsessile collected in Bulgaria [

28].

Otogirinin A (

10), another adamantane-containing metabolite from

Hypericum subsessile, demonstrated pronounced anti-inflammatory activity. This compound stimulated M2 macrophage markers such as arginase-1 and KLF4, inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced nitric oxide (NO) production, suppressed inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression, and reduced TNF-α formation by blocking MAPK/JNK phosphorylation and IκBα degradation. These findings indicate its potential as a candidate for the treatment or prevention of inflammatory diseases [

29].

Two additional adamantane-skeleton metabolites, hookeriones C (

11) and D (

12), isolated from

Hypericum hirsutum grown in Germany, were evaluated in vitro for their effects on human microvascular endothelial cell proliferation using a crystal violet assay. Both compounds exhibited moderate antiproliferative activity compared with hyperforin used as a positive control [

30].

Daphniphyllum alkaloids represent a structurally diverse class of polycyclic natural products produced by plants of the genus

Daphniphyllum. Among them, dapholdhamine D (

13), isolated from the leaves of

Daphniphyllum oldhami, contains an adamantane-type core [

31]. The complex fused-ring architectures and broad biological activities of Daphniphyllum alkaloids—including cytotoxic, antioxidant, vasodilatory, and antiplatelet effects—make them attractive targets for synthetic and biosynthetic investigations [

32].

Finally, among naturally occurring marine toxins, tetrodotoxin (TTX,

14) is one of the most potent and well-known compounds featuring an adamantane-like skeleton. TTX is widely distributed among marine organisms and, among terrestrial taxa, is restricted to certain amphibians. In these species, TTX localized in the skin and eggs serves as a chemical defense against predators. While TTX in marine organisms is generally believed to originate from symbiotic or dietary bacteria, the biosynthetic origin of TTX in terrestrial vertebrates remains controversial and continues to be an active area of research [

33,

34,

35].

Among these compounds, the marine polyarsenic metabolite arsenicin A (

15) represents a remarkable example of a naturally occurring molecule featuring an adamantane-like tetraarsenic cage structure. Arsenicin A (

15) and structurally related polyarsenic compounds have been extensively investigated for their antitumor activity in vitro and were found to be more potent than the clinically approved arsenic trioxide. In addition, a novel natural compound, arsenicin D (

16), was identified through synthetic studies and was subsequently shown to be deficient in Echinochalina bargibanti extracts. Both arsenicin A (

15) and arsenicin D (

16) demonstrated strong growth-inhibitory effects against nine SGS tumor cell lines, with GI₅₀ values in the submicromolar range under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions, while exhibiting high selectivity toward non-tumor cell lines [

36,

37].

To date, naturally occurring molecular structures containing a cubane-type core have not been identified. Consequently, the biological activity of cubane-based compounds discussed in this review is derived exclusively from synthetic analogues, and their pharmacological potential has been evaluated using the PASS approach.

Table 1 summarizes the experimentally reported biological activities of adamantane-type natural compounds isolated from various living organisms, alongside activities predicted using PASS. Comparative analysis indicates that more than 95% of the predicted activities were either experimentally confirmed or showed close correspondence with reported biological effects, supporting the reliability of PASS-based evaluations for this class of compounds.

3. Comparative Activity of Adamantane and Cubane Derivatives

Previously, we investigated the biological activity of natural adamantane-type compounds and a series of synthetic adamantane derivatives bearing various ligands [

20]. The primary objective of that study was to evaluate the predictive reliability of the PASS program for both natural and synthetic adamantanes. Building on these findings, the present work extends this approach to cubane derivatives functionalized with different ligands.

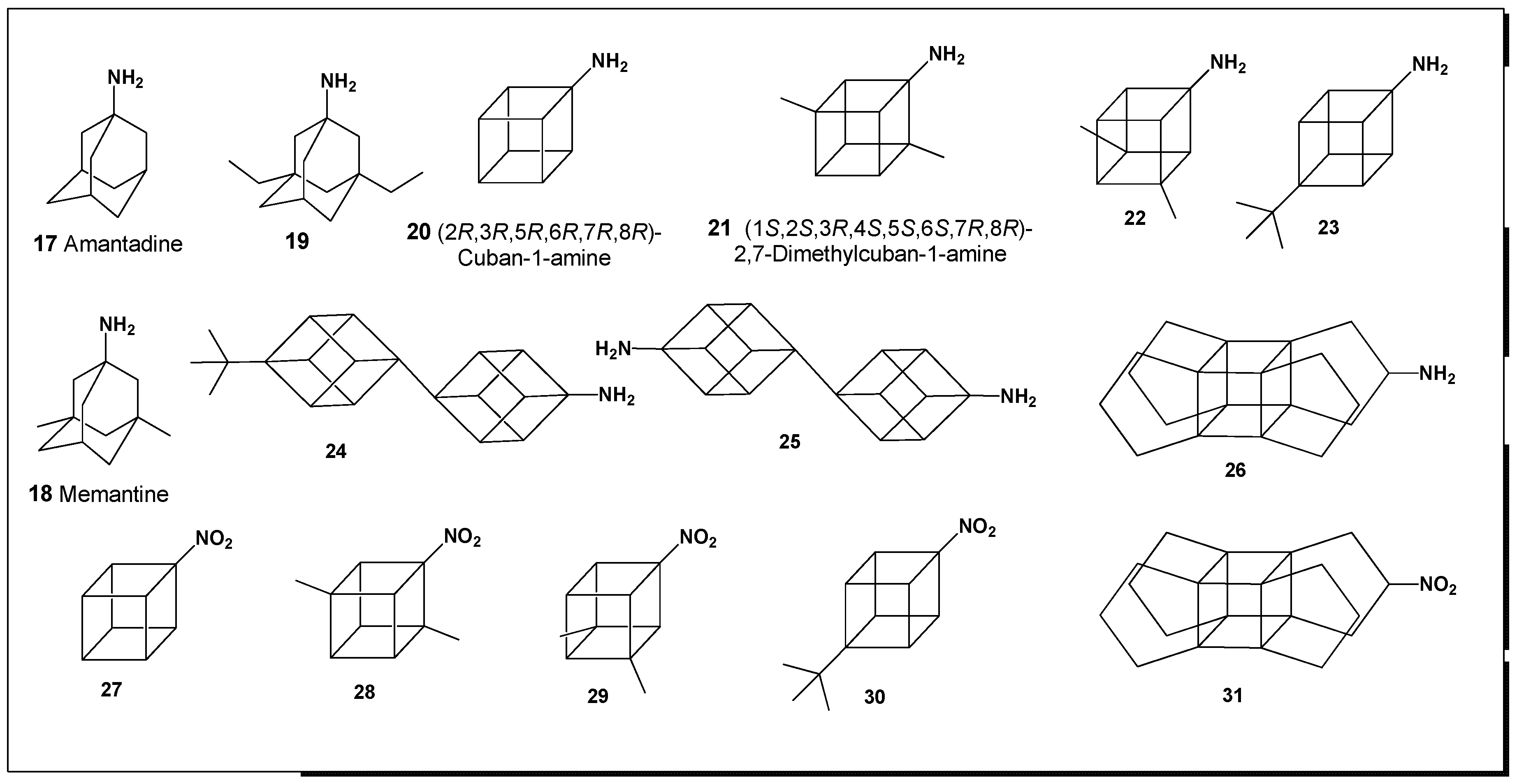

Among the most well-known adamantane derivatives is amantadine (

17, 1-aminoadamantane; structure shown in

Figure 2 and activities summarized in

Table 2), marketed under the trade names Gocovri, Symadine, and Symmetrel. Amantadine was first synthesized in the late 1950s, and its anti-influenza activity was demonstrated in the early 1960s. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 1968 as a prophylactic against Asian influenza and was later authorized for the treatment of influenza A virus infections in 1976 [

5,

13,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

Amantadine was introduced into clinical practice for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease in 1969 [

43,

44] and was subsequently explored for Huntington’s chorea and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease [

45,

46]. More than a decade later, it was also investigated for potential use in Alzheimer’s disease therapy [

47] (see

Table 3). Comparative pharmacological analysis of amantadine using the PASS program revealed a high probability of antiparkinsonian activity (Pa = 93%). Lower but still notable probabilities were predicted for its application in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, antiviral activity was predicted against influenza virus (Pa = 73%), arboviruses (Pa = 70%), and picornaviruses (Pa = 58%). These predictions are in full agreement with numerous experimental and clinical studies reported in the literature [

20,

48,

49,

50,

51].

Another clinically important aminoadamantane is memantine (

18, 1-amino-3,5-dimethyladamantane), also known under the trade names

Axura, Ebixa, and

Namenda. Memantine was synthesized in the late 1970s and rapidly entered clinical evaluation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease [

52,

53] and dementia [

54,

55,

56]. Although memantine is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, it is often considered less favorable than acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, partly due to its adverse effect profile, which may include psychosis, heart failure, headache, constipation, drowsiness, and dizziness.

PASS-based comparative analysis of memantine revealed enhanced predicted activity against neurodegenerative disorders relative to amantadine. Specifically, antiparkinsonian and anti-Alzheimer’s activities were predicted with probabilities of 95% and 83%, respectively (

Table 2). These predictions are well supported by published clinical and pharmacological reviews summarizing extensive studies conducted worldwide [

57,

58,

59,

60].

Given that the experimentally established biological activities of adamantane derivatives represent only a fraction of their potential pharmacological spectrum, we further evaluated their activity profiles using PASS. In this approach, predicted activities are interpreted and prioritized based on flexible selection criteria tailored to specific research objectives. For example, selecting a high threshold Pa value increases the likelihood of experimental confirmation but simultaneously leads to the exclusion of many genuine activities. If Pa > 80% is used as a cutoff, approximately 80% of true activities may be lost; similarly, at Pa > 70%, about 70% of actual activities are excluded.

By default, PASS applies a threshold where Pa ≈ Pi, which provides an average prediction accuracy of approximately 85% during cross-validation after a single prediction cycle. For heterogeneous compound datasets, the average accuracy of PASS predictions reaches approximately 96% [

20].

The predicted biological activity spectra of amantadine (

17), memantine (

18), and (1

R,3

R,5

S,7

R)-3,5-diethyladamantan-1-amine (

19) at Pa > 50% are summarized in

Table 2. As shown, amantadine exhibits a predicted antiparkinsonian activity with a probability of 95.8% (highlighted in bold). In addition, several related pharmacotherapeutic effects are predicted with high confidence, including treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, phobic disorders, rigidity relief, multiple sclerosis, cognitive disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease, with Pa values ranging from 75% to 95% (

Table 2).

Several additional pharmacological effects are also predicted for amantadine, including pronounced anti-ischemic (Pa = 97.7%) and nootropic (Pa = 96.9%) activities. These predictions provide a rationale for further targeted biological and pharmacological investigations of amantadine and, if experimentally validated, may open new avenues for its therapeutic application beyond its currently approved indications.

As evident from the predicted activity spectrum of memantine (

18) presented in

Table 2, the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia is predicted with probabilities of 82.8% and 75.8%, respectively (highlighted in bold). In addition, several related pharmaco-therapeutic effects are predicted with high confidence, including anti-ischemic (Pa = 98.3%) and nootropic (Pa = 97.7%) activities, treatment of Parkinson’s disease (Pa = 95.1%) and neurodegenerative diseases (Pa = 93.5%), as well as potential applications in the treatment of mood disorders (Pa = 88.5%), multiple sclerosis (Pa = 88.1%), and vascular (peripheral) diseases (Pa = 87.9%).

4. Activity of Amino- and Nitro-Cubanes

This group comprises cubane derivatives bearing amino (

20–

26) and nitro (

27–

31) substituents (structures shown in

Figure 2) [

61,

62,

63]. Most of these compounds—particularly those additionally substituted with methyl or

tert-butyl groups—exhibited moderate predicted potential for the treatment of phobic disorders. However, two compounds demonstrated notably distinct biological profiles. Specifically, compound

20 (2R,3R,5R,6R,7R,8R-cuban-1-amine) and compound

27 (2

R,3

R,5

R,6

R,7

R,8

R-1-nitrocubane) showed pronounced antiprotozoal activity against

Plasmodium spp. despite lacking additional alkyl substituents. From a stereochemical perspective, the underlying reasons for this enhanced activity remain unclear and warrant further investigation.

Table 3 summarizes the predicted biological activities of these cubane derivatives. Although these compounds may not represent primary candidates for direct pharmacological development, they are of considerable value as synthetic building blocks for the design and development of novel cubane-based bioactive molecules. Notably, two propellacubane derivatives—one bearing an amino group (

30) and the other a nitro group (

31)—exhibited significant antispasmodic activity, highlighting the influence of scaffold modification on biological response.

In comparison with amino-adamantanes (17–19), which uniformly display pronounced antiparkinsonian activity, amino- and nitro-cubanes (20–31) demonstrate a distinctly different pharmacological profile. These compounds are characterized by a higher predicted potential as diuretic and antispasmodic agents, as well as therapeutic candidates for the treatment of phobic disorders, underscoring the divergent biological behavior of cubane and adamantane scaffolds despite their similar hydrocarbon nature.

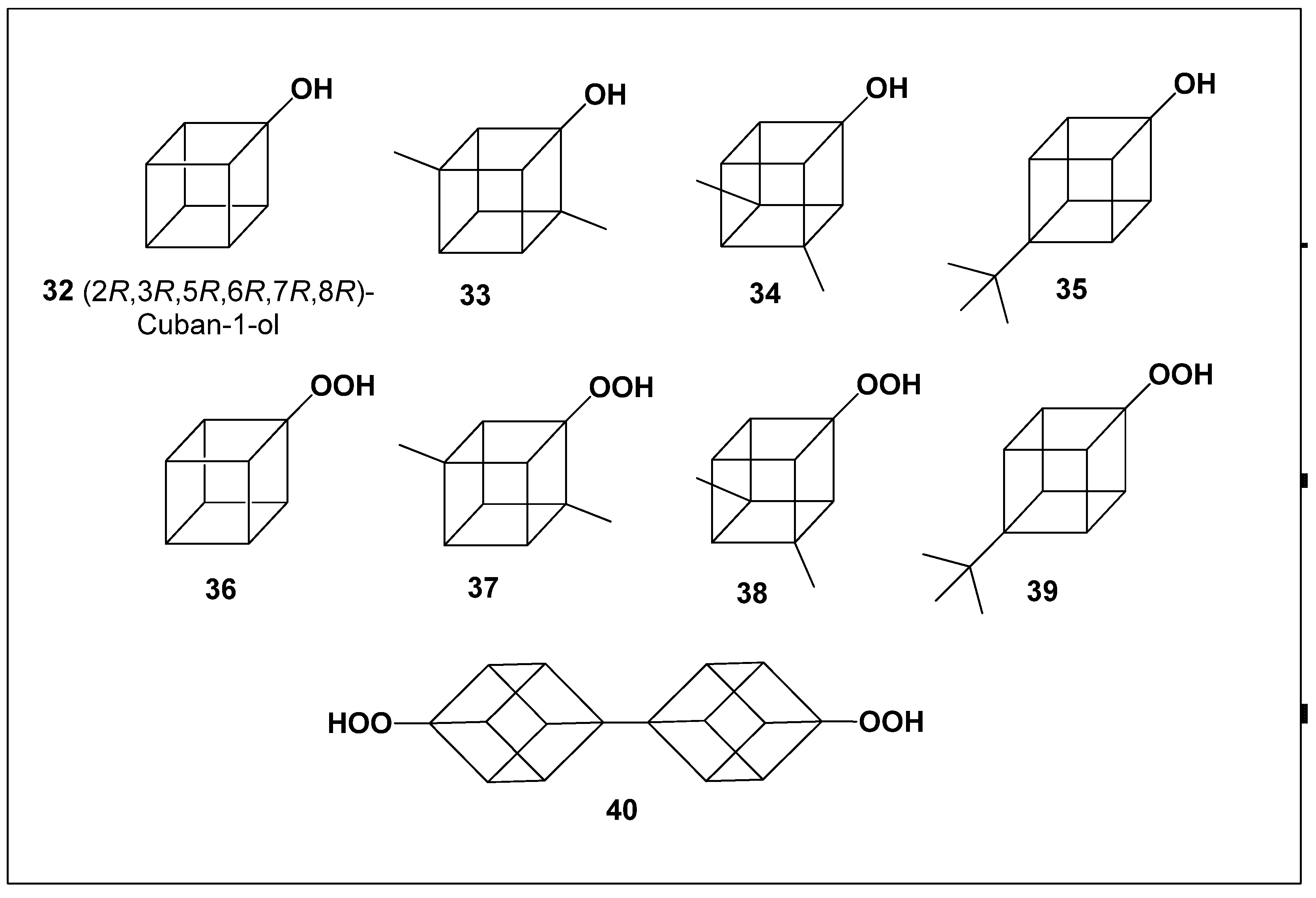

5. Cubane-1-Ols and 1-Hydroperoxycubanes: Biological Activity

This group comprises four cuban-1-ols and five 1-hydroperoxycubanes (

32–

40;

Figure 3). A clear distinction in biological activity was observed between these two subclasses. Compounds

36–

40, which contain a hydroperoxide functionality, exhibited pronounced antiprotozoal activity against

Plasmodium spp., whereas cuban-1-ols

32–

35 demonstrated moderate cardiovascular analeptic effects (

Table 3).

The strong antiprotozoal activity of 1-hydroperoxycubanes (

36–

40) is consistent with well-established data showing that hydroperoxide- and endoperoxide-containing terpenoids and steroids possess potent activity against protozoan parasites, particularly Plasmodium species. This phenomenon has been extensively documented, including in our previous experimental studies and review articles. A consolidated overview of the predicted biological activities of cuban-1-ols and 1-hydroperoxycubanes is provided in

Table 4.

Natural endoperoxides and hydroperoxides are widely distributed in plants, algae, fungi, and marine invertebrates, and many exhibit marked antiprotozoal effects. However, their therapeutic application remains limited, as peroxide-containing compounds are often associated with toxicity and adverse side effects, particularly due to oxidative stress and nonspecific reactivity [

64,

65,

66,

67].

To date, more than 130 peroxide-based compounds have demonstrated significant in vitro anticancer activity in tumor cell assays, drawing the attention of the National Cancer Institute for subsequent in vivo evaluation. Extensive investigations of peroxide-containing natural products from terrestrial and marine sources have led to the identification of numerous cytotoxic agents. Nevertheless, only a small fraction of these compounds have progressed to preclinical or clinical development, largely due to the limited availability of bioactive metabolites from natural sources. This scarcity represents a major bottleneck in drug discovery and underscores the critical importance of total synthesis and synthetic analog development to secure sufficient material for comprehensive pharmacological and toxicological studies [

68,

69,

70].

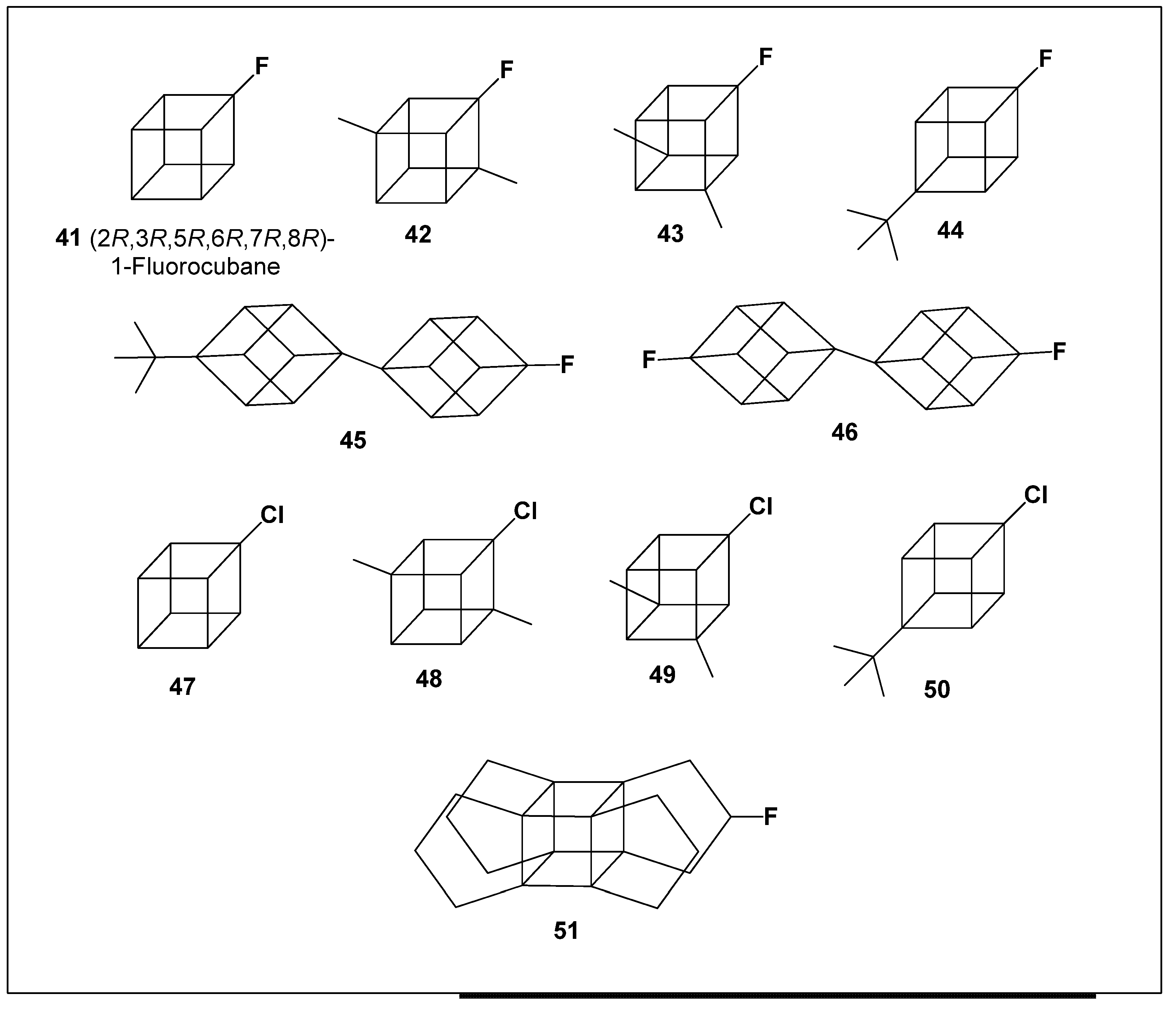

6. Activities of Halogenated Cubanes

Halogenated cubanes have been successfully synthesized and are widely employed as versatile intermediates, particularly in the development of boron-containing derivatives and functionalized cubane frameworks [

71,

72,

73]. To assess their potential biological relevance, fluorinated and chlorinated cubanes were selected as representative model compounds (

Figure 4).

PASS-based analysis of cubane fluoride derivatives revealed a pronounced tendency toward anti-inflammatory activity. Among these compounds,

41 and

46 demonstrated especially strong predicted activity, with probabilities of 91.4% and 93.9%, respectively (

Table 5). In addition to anti-inflammatory effects, fluorinated propellacubane (

33) exhibited a notable predicted antidiabetic activity, suggesting potential applicability in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The biological relevance of fluorinated cage hydrocarbons is further supported by data on fluorinated adamantanes. Notably, 1-fluoro-adamantane has been reported to exhibit a 98–100% probability of antiparkinsonian activity, surpassing the predicted efficacy of well-established drugs such as amantadine and memantine [

20]. This comparison highlights the favorable influence of fluorine substitution on the neuro-pharmacological profile of rigid polycyclic scaffolds.

In contrast, cubane chlorides (

47–

50) displayed a different spectrum of predicted biological activities, with a predominance of psychotropic and neuroactive effects. Among these, 1-chlorocubane (

47) (2

R,3

R,5

R,6

R,7

R,8

R−1−chlorocubane) emerged as the most active compound in this subgroup (

Table 5), indicating its potential as a lead structure for psychotropic drug development.

Consistent with these findings, chlorinated adamantanes and structurally related analogues have previously been reported to exhibit antipsychotic (Pa = 85–91%) and psychotropic (Pa = 74–78%) activities, further supporting the notion that halogen substitution within rigid cage hydrocarbons can significantly modulate central nervous system activity [

20,

74].

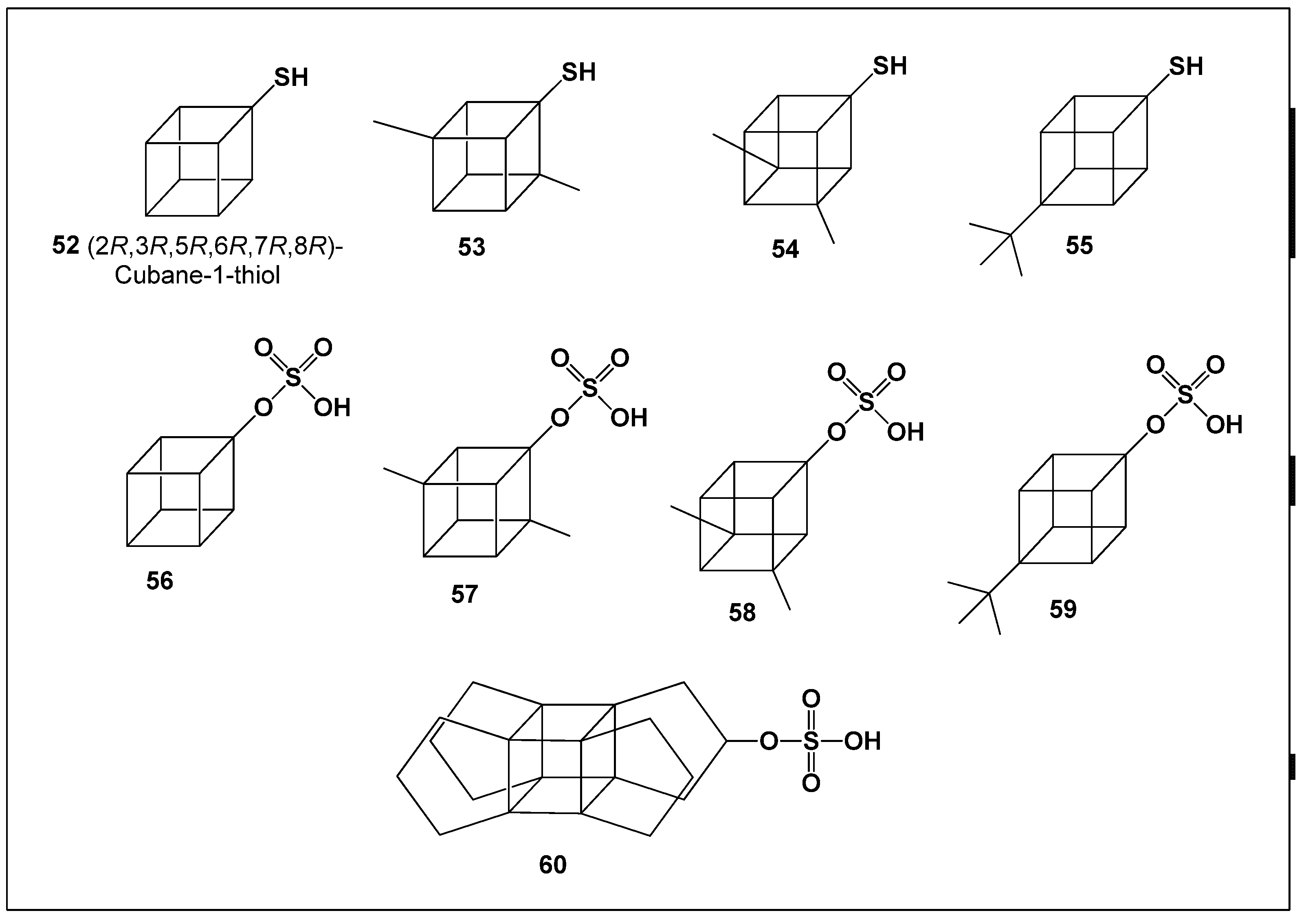

7. Thiols and Sulfate-Containing Cubanes

Cubane-derived thiols [

75,

76] and sulfate esters [

77,

78] are well-established intermediates in organic synthesis and are frequently employed in the construction of structurally complex and functionalized molecular frameworks. Representative compounds selected for biological activity evaluation are shown in

Figure 5.

PASS-based analysis indicated that thiol-substituted cubanes (

52–

55) possess only limited pharmacological potential. These compounds exhibited moderate predicted activity as renal function stimulants, accompanied by weak anti-nephrotoxic properties (

Table 6). Similarly, cuban-1-yl hydrogen sulfates (

56–

59) and propellacubane sulfate (

60) demonstrated moderate to weak biological activity, with predicted effects resembling those of glycopeptide antibiotics, albeit at relatively low confidence levels.

Overall, these findings suggest that thiol cubanes and cubane sulfates are unlikely to represent promising leads for further pharmacological development. Their primary utility remains in synthetic chemistry, where they serve as valuable building blocks rather than bioactive drug candidates.

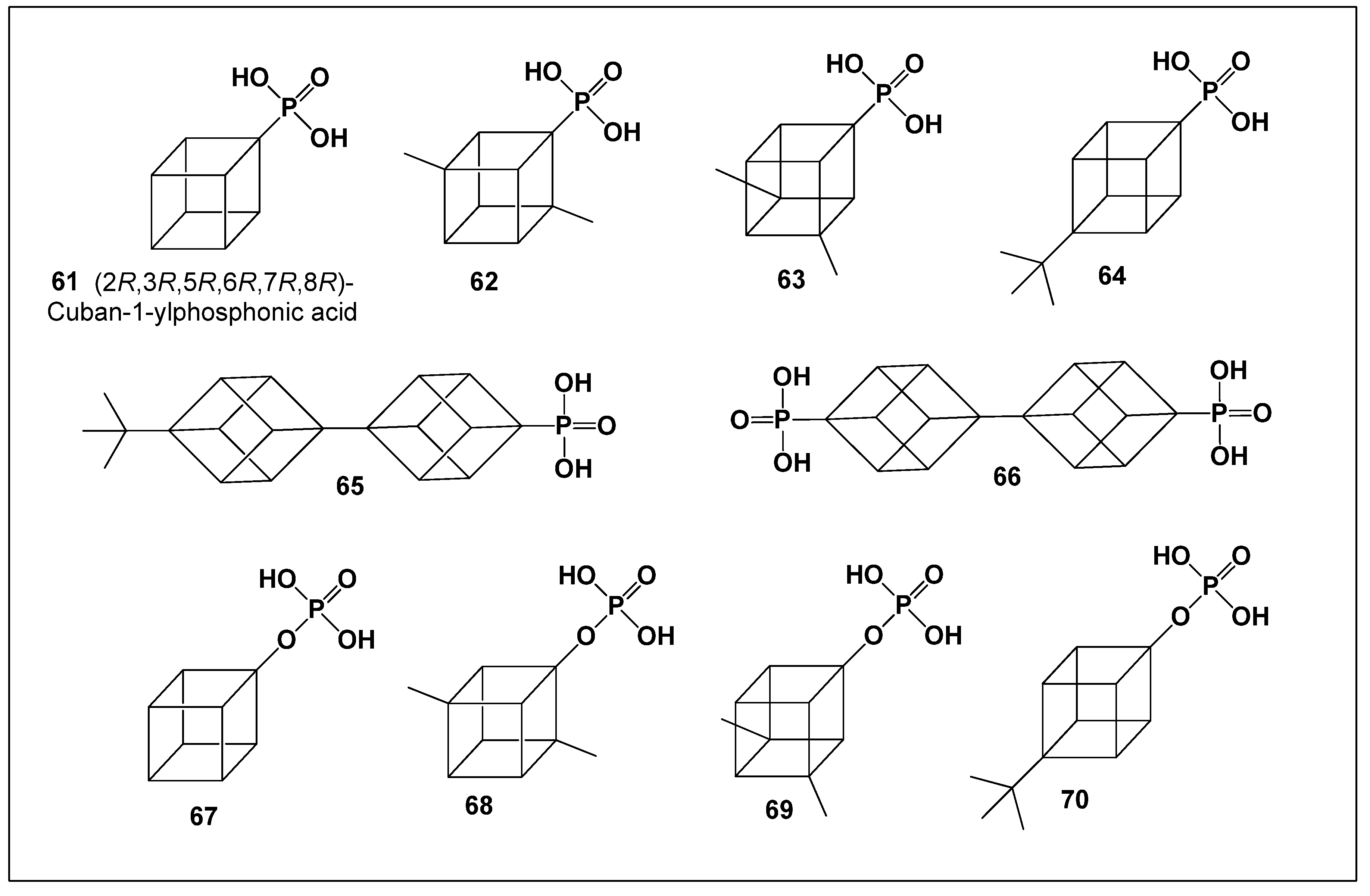

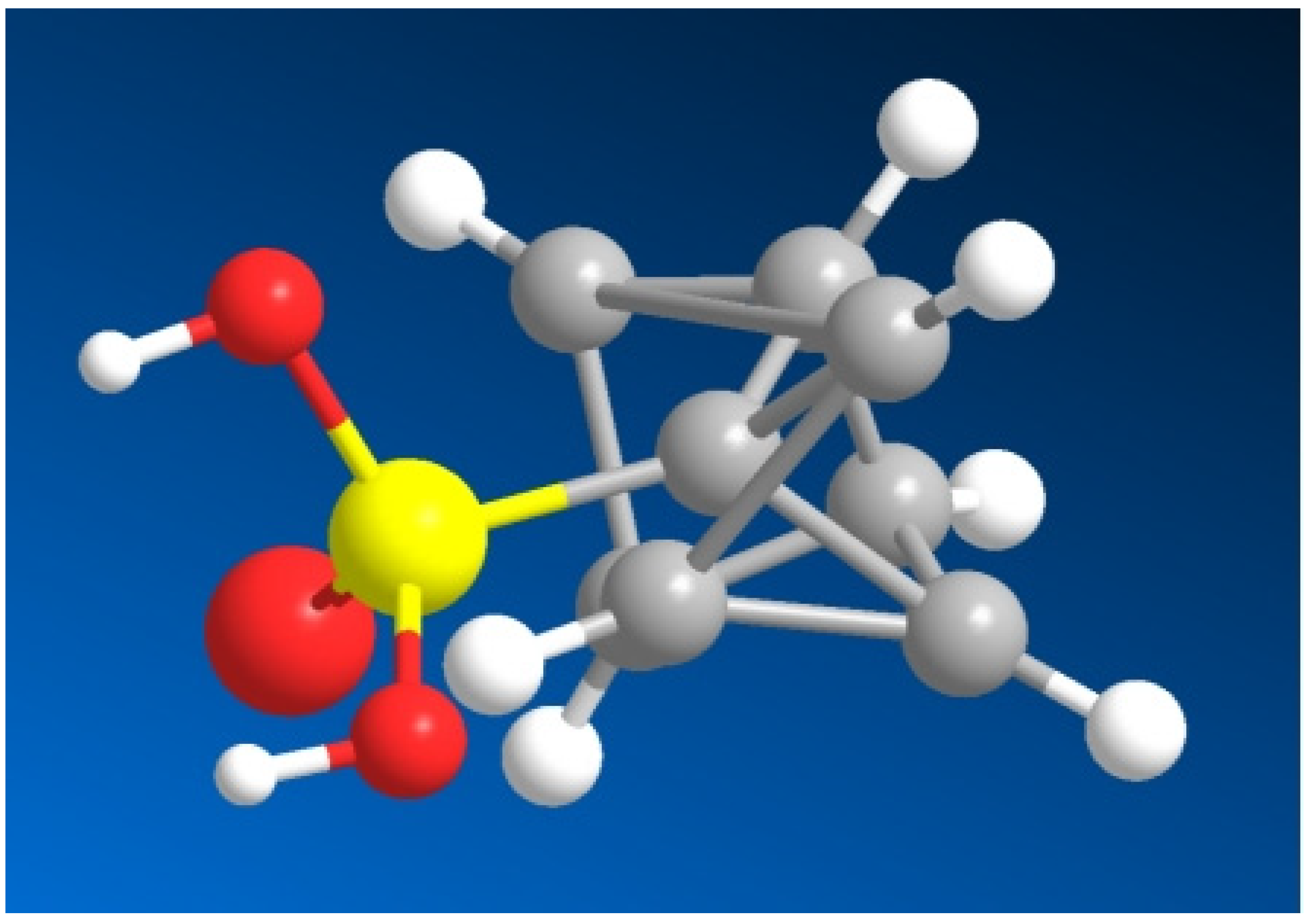

8. Cuban-1-yl-Phosphonic Acids and Cuban-1-yl Dihydrogen Phosphates

In contrast, the evaluation of phosphorus-containing cubane derivatives, specifically cuban-1-yl phosphonic acids and cuban-1-yl dihydrogen phosphates, revealed notably different and highly encouraging results. Remarkably, all tested cuban-1-yl phosphonic acids (

61–

66;

Figure 6) demonstrated predicted antiparkinsonian activity, highlighting this class as a promising scaffold for the development of therapeutics targeting neurodegenerative disorders.

Among these compounds, 62–65 exhibited moderate antiparkinsonian activity, whereas compound 61 (2R,3R,5R,6R,7R,8R−cuban−1−yl-phosphonic acid) and compound 66 ([1,1′−bi(cuban)]−4,4′−yl−phosphonicacid) stood out due to their strong predicted effects. These two derivatives therefore emerge as particularly attractive lead candidates for further experimental validation in models of Parkinson’s disease and related neurodegenerative conditions.

Structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis revealed that substituent type and position significantly influence antiparkinsonian activity within the cuban-1-yl-phosphonic acid series. Introduction of methyl groups at positions 2 and 7 in compound

62, and at positions 3 and 5 in compound

63, resulted in an approximately 8% decrease in predicted activity relative to the parent compound

61 (

Figure 6).

Incorporation of bulkier tert-butyl substituents produced a more pronounced reduction in activity. Specifically, substitution at position 4 in compound 64 (1S,2R,3R,8S)−4−(tert−butyl)cuban−1−yl−phosphonic acid led to a 7.5% decrease, while introduction of a tert-butyl group in compound 65 (4′−(tert−butyl)−[1,1′−bi(cuban)]−4−yl−phosphonicacid) resulted in an 11% reduction in antiparkinsonian potential. These data indicate that steric bulk exerts a stronger negative impact on activity than simple alkyl substitution.

Notably, the difference in predicted activity between compound

61 and the

bi-cubane derivative

66 was minimal (0.52%), indicating nearly equivalent antiparkinsonian efficacy despite their structural divergence. PASS predictions (

Table 7) consistently support the conclusion that cuban-1-yl-phosphonic acids represent a highly promising class of antiparkinsonian agents.

Visualization of the predicted activity profiles using a comparative three-dimensional plot (

Figure 7) further highlights compounds 61, 65, and 66 as exhibiting particularly strong therapeutic potential. In addition to its antiparkinsonian profile, compound 61 is also predicted to display high anxiolytic and psychotropic activity, further enhancing its relevance as a multifunctional neuroactive lead structure.

Phosphate and phosphonate derivatives of adamantane have attracted considerable interest in pharmacological research due to their pronounced neuroactive properties. Among these compounds, phosphate esters of adamantane derivatives demonstrate notable neuroprotective activity with predicted probabilities ranging from 70–82%, and also exhibit potential psychostimulant and antidiabetic effects. However, the most promising representatives of this class are 1-adamantylphosphonic acids, which stand out due to their exceptionally high predicted antiparkinsonian activity (98–100%) and psychotropic effects (97–98%). These findings suggest that 1-adamantylphosphonic acids may surpass amantadine and memantine in therapeutic efficacy in certain clinical contexts [

20].

Predictive modeling further underscores the outstanding pharmacological potential of 1-adamantyl-3,7-dimethylphosphonic acid, which exhibits a 99.5% probability of being effective in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease—significantly exceeding the predicted activities of both amantadine and memantine. In addition, this compound shows strong predicted efficacy for neurodegenerative disorders and dementia, positioning 1-adamantylphosphonic acid derivatives as compelling candidates for Parkinson’s disease therapy. Notably, when used in combination with established drugs such as amantadine or memantine, these compounds may enhance therapeutic outcomes and contribute to more comprehensive management of neurodegenerative diseases [

20,

74].

A comparative analysis of PASS predictions for cuban-1-yl-phosphonic acids, which also demonstrate strong antiparkinsonian properties, and 1-adamantylphosphonic acids (with 98–100% predicted antiparkinsonian activity; see

Figure 6) reveals that phosphonic acids derived from both cubane and adamantane scaffolds possess substantial potential for the prevention and treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Structurally, these compounds share a direct C–P bond, with phosphorus covalently bound to carbon. Phosphonates are known to function as bioisosteres of phosphates and carboxylates, enabling them to interfere with metabolic enzymes and biological pathways. These features collectively make them highly attractive candidates for future neurotherapeutic drug development [

79].

Phosphonates, whether of natural origin or obtained synthetically, are particularly intriguing due to their ability to mimic endogenous biomolecules containing phosphate or carboxylic acid groups, thereby exhibiting diverse and often unique biological activities. Bioinformatic analyses have revealed that genes encoding phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) phosphomutase, a key enzyme involved in phosphonate biosynthesis, are widespread in bacterial genomes [

80,

81,

82]. Despite their biological relevance, phosphonates remain relatively underexplored as bioactive compounds, largely due to challenges associated with their isolation and purification, including high aqueous solubility and low natural production yields. Advances in purification methodologies, coupled with chemoenzymatic synthesis strategies that integrate biosynthetic pathways from diverse phosphonate-producing organisms, could substantially expand phosphonate chemical diversity and accelerate the discovery of novel neuroactive phosphonate-based therapeutics [

20,

74,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86].

Among the cuban-1-yl dihydrogen phosphates (compounds

67–

70), several derivatives have demonstrated remarkable anticancer activity against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines. In particular, compounds

67,

68, and

70 exhibited strong antiproliferative effects, whereas the introduction of methyl or

tert-butyl substituents in compound

70 resulted in a noticeable reduction in activity (

Table 7). In contrast, compound

69, identified as (1

R,2

S,3

R,4

S,5

R,6

R,7

S,8

S)-3,5-dimethyl-cuban-1-yl dihydrogen phosphate, displayed only moderate anesthetic properties and weak anticancer activity, highlighting the significant influence of substituent pattern on biological performance.

9. Prediction of Biological Activity for Adamantane and Cubane Derivatives

It is well established that the chemical structure of a molecule determines its biological activity, a principle known as the structure–activity relationship (SAR). This concept has been recognized for more than 150 years and was formally articulated by Brown and Fraser in 1868 [

87]. However, alternative historical sources indicate that SAR concepts were applied even earlier in toxicology. Notably, Cros reported as early as 1863 a correlation between the toxicity of primary aliphatic alcohols and their solubility in water [

88].

In the present study, we applied computer-aided prediction of biological activity to evaluate 51 cubane derivatives bearing various ligands, alongside natural adamantane-containing compounds and synthetic analogues of adamantane and cubane.

Considering that the experimentally characterized biological activities of natural adamantane derivatives and their synthetic analogues represent only a small fraction of their potential pharmacological profiles, we sought to estimate the full spectrum of possible biological activities using in silico prediction methods. For this purpose, we employed the PASS (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances) computer program [

89,

90,

91].

PASS predicts more than 10,000 types of biological activity, including pharmacological effects, mechanisms of action, and potential adverse properties such as mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, and embryotoxicity, based solely on the structural formula of a compound. The predictions are derived from SAR analysis using a training set comprising approximately one million biologically relevant compounds, including approved drugs, drug candidates, and lead structures. The theoretical foundations and algorithms underlying PASS have been described in detail in multiple publications [

20,

74,

92,

93,

94].

Structural data in MOL or SD file formats serve as input for the PASS program, which generates a list of predicted biological activities for each compound. For every predicted activity, two parameters are calculated: Pa (probability of activity) and Pi (probability of inactivity). These values may be interpreted either as the probabilities of a compound belonging to the classes of active or inactive molecules, respectively, or as the probabilities of type I and type II prediction errors.

The interpretation of PASS results and the selection of promising compounds depend on flexible criteria determined by the specific objectives of a study. Selecting a high Pa threshold increases the likelihood that predicted activities will be experimentally confirmed; however, it also results in the loss of many potentially relevant activities. For example, using Pa > 80% as a cutoff leads to the loss of approximately 80% of known activities, whereas a cutoff of Pa > 70% results in the loss of about 70% of activities, and so forth.

By default, PASS employs a Pa = Pi threshold determined during model training, which yields an average prediction accuracy of approximately 85% in leave-one-out cross-validation across the entire training set of nearly 1,000,000 compounds and 10,000 biological activities. For heterogeneous external validation sets, the average predictive accuracy approaches 90% [

95]. In addition to biological activity prediction, PASS also evaluates drug-likeness according to the methodology described in [

96].

Conclusion

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the structural features and pharmacological potential of adamantane- and cubane-based compounds, emphasizing both naturally occurring adamantane derivatives and synthetically accessible cubane analogues. Despite their similar carbon frameworks, these two scaffolds differ fundamentally in strain energy, geometry, and electronic properties, which translates into markedly different biological activity profiles and therapeutic prospects.

Natural adamantane-containing metabolites, isolated from plants, marine organisms, and microorganisms, exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and neuroprotective effects. These findings reinforce the importance of the adamantane core as a privileged scaffold in drug discovery. Clinically established adamantane derivatives such as amantadine and memantine further demonstrate the relevance of this framework for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

In contrast, cubane-based compounds, although not known to occur in nature, represent a rapidly emerging class of rigid three-dimensional bioisosteres. Their exceptional strain energy, structural symmetry, and ability to tolerate diverse functionalization patterns enable unique interactions with biological targets that are not readily accessible using conventional aromatic systems. PASS-based prediction of biological activity spectra revealed that cubane derivatives possess significant and previously underappreciated pharmacological potential. Notably, cuban-1-yl phosphonic acids and dihydrogen phosphates exhibited strong predicted antiparkinsonian and anticancer activities, in some cases comparable to or exceeding those of established adamantane drugs.

A particularly important finding of this study is the exceptional predicted efficacy of phosphonate derivatives of both adamantane and cubane, which consistently demonstrated high probabilities for antiparkinsonian, neuroprotective, psychotropic, and anxiolytic activities. Given their structural similarity to biological phosphates and carboxylates, these compounds may act as enzyme inhibitors or modulators of metabolic pathways, making them promising candidates for neurodegenerative disease therapy. Hydroperoxy cubanes also emerged as potent antiprotozoal agents, while selected halogenated cubanes displayed anti-inflammatory, psychotropic, and antidiabetic potential.

The application of PASS in silico prediction proved to be a powerful strategy for evaluating large sets of rigid hydrocarbon derivatives and identifying promising lead structures prior to experimental validation. The high concordance between predicted and experimentally confirmed activities for adamantane-type compounds supports the reliability of this approach for prioritizing cubane-based candidates, where experimental data remain scarce.

In conclusion, both adamantane and cubane scaffolds represent highly valuable platforms for the development of next-generation therapeutics, particularly for neurodegenerative, infectious, and oncological diseases. Future research should focus on the synthesis and biological evaluation of cubane phosphonates and peroxides, optimization of their pharmacokinetic properties, and validation of their predicted activities in relevant in vitro and in vivo models. The integration of computational prediction, synthetic chemistry, and biological testing will be essential to fully realize the therapeutic potential of these unique hydrocarbon frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.D.; methodology, V.M.D.; software, A.O.T.; investigation, V.M.D.; resources, V.M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.T. and V.M.D.; writing—review and editing, A.O.T. and V.M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shokova, E.A.; Kim, J.K.; Kovalev, V.V. Adamantane: On the 90th anniversary of its appearance in chemical science. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 60, 1831–1891.

- Fort, R.C.; Schleyer, P.V.R. Adamantane: Consequences of the diamondoid structure. Chem. Rev. 1964, 64, 277–300.

- Bazyleva, A.B.; Blokhin, A.V.; Kabo, G.J.; Charapennikau, M.B.; Emel’yanenko, V.N.; Verevkin, S.P.; Diky, V. Thermodynamic properties of adamantane revisited. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 10064–10072.

- Takebe, H.; Matsubara, S. Cuneanes as potential benzene bioisosteres having chirality. Synthesis 2025, 57, 1441–1447.

- Spasov, A.A.; Khamidova, T.V.; Bugaeva, L.I.; Morozov, I.S. Adamantane derivatives: Pharmacological and toxicological properties. Pharm. Chem. J. 2000, 34, 1–7.

- Schwertfeger, H.; Fokin, A.A.; Schreiner, P.R. Diamonds are a chemist’s best friend: Diamondoid chemistry beyond adamantane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1022–1036.

- Dane, C.; Montgomery, A.P.; Kassiou, M. The adamantane scaffold: Beyond a lipophilic moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, —, 117592.

- Yasukawa, T.; Håheim, K.S.; Cossy, J. Functionalization of cubane: Formation of C–C and C–heteroatom bonds. Helv. Chim. Acta 2024, 107, e202300200.

- Kumar, M.P.; Annie, A.S.; Solanke, J.N.; Dandela, R.; Dhayalan, V. A comprehensive review on selective catalytic methods for functionalization of adamantane scaffolds. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2024, 13, e202400184.

- Rinn, N.; Rojas-León, I.; Peerless, B.; Gowrisankar, S.; Ziese, F.; et al. Adamantane-type clusters: Compounds with a ubiquitous architecture but a wide variety of compositions and unexpected materials properties. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 9438–9509.

- Eaton, P.E. Cubanes: Starting materials for the chemistry of the 1990s and the new century. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 1421–1436.

- Bigness, A.; Vaddypally, S.; Zdilla, M.J.; Mendoza-Cortes, J.L. Ubiquity of cubanes in bioinorganic relevant compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 450, 214168.

- Wanka, L.; Iqbal, K.; Schreiner, P.R. The lipophilic bullet hits the targets: Medicinal chemistry of adamantane derivatives. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3516–3604.

- Spilovska, K.; Zemek, F.; Korabecny, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Soukup, O.; Windisch, M.; Kuca, K. Adamantane—A lead structure for drugs in clinical practice. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 3245–3266.

- Biegasiewicz, K.F.; Griffiths, J.R.; Savage, G.P.; Tsanaktsidis, J.; Priefer, R. Cubane: 50 years later. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6719–6745.

- Mykhailiuk, P.K. Saturated bioisosteres of benzene: Where to go next? Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 2839–2849.

- Landa, S.; Machacek, V. Adamantane, a new hydrocarbon extracted from petroleum. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1933, 5, 1–5.

- Mair, B.J.; Shamaiengar, M.; Krouskop, N.C.; Rossini, F.D. Isolation of adamantane from petroleum. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 2082–2083.

- Petrov, A.; Arefjev, O.A.; Yakubson, Z.V. Hydrocarbons of adamantane series as indices of petroleum catagenesis process. In Advances in Organic Geochemistry 1973; Tissot, B., Bienner, F., Eds.; Editions Technip: Paris, France, 1974; pp. 517–522.

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Pharmacological profile of natural and synthetic compounds with rigid adamantane-based scaffolds as potential agents for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 1225–1241.

- Chen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Teng, H.; Gan, F.; et al. Adamantyl and homoadamantyl derivatives from Garcinia multiflora fruits. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 12291–12299.

- Liao, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Lao, Y.Z.; et al. Hypersubones A and B, new polycyclic acylphloroglucinols with intriguing adamantane-type cores from Hypericum subsessile. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1172–1175.

- Xiao, C.Y.; Mu, Q.; Gibbons, S. The phytochemistry and pharmacology of Hypericum. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2020, 112, 85–182.

- Henry, G.E.; Jacobs, H.; Carrington, C.S.; McLean, S.; Reynolds, W.F. Plukenetione A: An unusual adamantyl ketone from Clusia plukenetii (Guttiferae). Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 8663–8666.

- Řezanka, T.; Sigler, K. Sinaicinone, a complex adamantanyl derivative from Hypericum sinaicum. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 1272–1276.

- Zhang, L.J.; Chiou, C.T.; Cheng, J.J.; Huang, H.C.; et al. Cytotoxic polyisoprenyl benzophenonoids from Garcinia subelliptica. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 557–562.

- Chen, Y.; Gan, F.; Jin, S.; Liu, H.; Wu, S.; et al. Adamantyl derivatives and rearranged benzophenones from Garcinia xanthochymus fruits. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 17289–17296.

- Dragomanova, S. Neuropharmacological Investigation of Myrtenal Conjugates with Aminoadamantane; Medical University of Varna: Varna, Bulgaria, 2024; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses No. 31338203.

- Huang, C.Y.; Chang, T.C.; Wu, Y.J.; et al. Benzophenone and benzoylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum sampsonii with anti-inflammatory mechanism of otogirinin A. Molecules 2020, 25, 4463.

- Max, J.; Heilmann, J. Homoadamantane and adamantane acylphloroglucinols from Hypericum hirsutum. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 1167–1183.

- Zhang, Y.; Di, Y.T.; Mu, S.Z.; Li, C.S.; et al. Dapholdhamines A–D, alkaloids from Daphniphyllum oldhami. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1325–1327.

- Kobayashi, J.I.; Kubota, T. The Daphniphyllum alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 936–962.

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, S.; Yin, S.; Wang, T. Source, ecological function, toxicity, and resistance of tetrodotoxin (TTX) in TTX-bearing organisms: A comprehensive review. Toxin Rev. 2023, 42, 727–740.

- Bane, V.; Lehane, M.; Dikshit, M.; O’Riordan, A.; Furey, A. Tetrodotoxin: Chemistry, toxicity, source, distribution and detection. Toxins 2014, 6, 693–755. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, F.R.; Cobos, E.J.; Tejada, M.Á.; Sánchez-Fernández, C.; González-Cano, R.; Cendán, C.M. Tetrodotoxin (TTX) as a therapeutic agent for pain. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 281–305.

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Levitsky, D.O. Arsenolipids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2004, 43, 403–448.

- Defant, A.; Mancini, I. A comprehensive computational NMR analysis of organic polyarsenicals including the marine sponge-derived arsenicins A–D and their synthetic analogs. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 511.

- Du, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B. The role of statins in dementia or Alzheimer’s disease incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1473796.

- Tang, B.C.; Wang, Y.T.; Ren, J. Basic information about memantine and its treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other clinical applications. iBrain 2023, 9, 340–348.

- Davies, W.L.; Grunert, R.R.; Haff, R.F.; McGahen, J.W.; Neumayer, E.M.; Paulshock, M.; Hoffmann, C.E. Antiviral activity of 1-adamantanamine (amantadine). Science 1964, 144, 862–863.

- Gagneux, A.R.; Meier, R. 1-Substituted 2-heteroadamantanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 10, 1365–1368.

- Hubsher, G.; Haider, M.; Okun, M.S. Amantadine: The journey from fighting flu to treating Parkinson disease. Neurology 2012, 78, 1096–1099.

- Schwab, R.S.; England, A.C., Jr.; Poskanzer, D.C.; Young, R.R. Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1969, 208, 1168–1170.

- Weeth, J.B.; Shealy, C.N.; Mercier, D.A. L-Dopa and amantadine in the therapy of parkinsonism. Wis. Med. J. 1969, 68, 325–328.

- Sanders, W.L.; Dunn, T.L. Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease treated with amantadine: A report of two cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1973, 36, 581–584.

- Scotti, G.; Spinnler, H. Amantadine and Huntington’s chorea. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1325–1326.

- Erkulwater, S.; Pillai, R. Amantadine and the end-stage dementia of Alzheimer’s type. South. Med. J. 1989, 82, 550–554.

- Hermans, P.E.; Cockerill, F.R., III. Antiviral agents. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1983, 58, 217–222.

- Arumugam, H.; Wong, K.H.; Low, Z.Y.; Lal, S.; Choo, W.S. Plant extracts as a source of antiviral agents against influenza A virus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf056.

- Bonomini, A.; Mercorelli, B.; Loregian, A. Antiviral strategies against influenza virus: An update on approved and innovative therapeutic approaches. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 75.

- Tarasov, V.V.; Kudryashov, N.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Kalinina, T.S.; et al. Pharmacological aspects of neuro-immune interactions. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 15–21.

- Ragshaniya, A.; Kumar, V.; Tittal, R.K.; Lal, K. Nascent pharmacological advancement in adamantane derivatives. Arch. Pharm. 2024, 357, 2300595.

- Arpanahi, S.K.; Hamidpour, S.; Jahromi, K.G. Mapping Alzheimer’s disease stages toward its progression: A comprehensive cross-sectional and longitudinal study using resting-state fMRI and graph theory. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 103, 102590.

- Jain, K.K. Evaluation of memantine for neuroprotection in dementia. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2000, 9, 1397–1406.

- Molinuevo, J.L.; Garcia-Gil, V.; Villar, A. Memantine: An antiglutamatergic option for dementia. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2004, 19, 10–18.

- Molinuevo, J.L.; Lladó, A.; Rami, L. Memantine: Targeting glutamate excitotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2005, 20, 77–85.

- Matsunaga, S.; Kishi, T.; Iwata, N. Memantine monotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123289.

- Kishi, T.; Matsunaga, S.; Oya, K.; Nomura, I.; Ikuta, T.; Iwata, N. Memantine for Alzheimer’s disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 60, 401–425.

- Lu, S.; Nasrallah, H.A. The use of memantine in neuropsychiatric disorders: An overview. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 234–248.

- Koseoglu, E. New treatment modalities in Alzheimer’s disease. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 1764–1776.

- Stockdale, T.P.; Williams, C.M. Pharmaceuticals that contain polycyclic hydrocarbon scaffolds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7737–7763.

- Fahrenhorst-Jones, T.; Kong, D.; Burns, J.M.; Pierens, G.K.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Savage, G.P.; Williams, C.M. seco-1-Azacubane-2-carboxylic acid–amide bond comparison to proline. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 12867–12871.

- Subbaiah, M.A.; Meanwell, N.A. Bioisosteres of the phenyl ring: Recent strategic applications in lead optimization and drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 14046–14128.

- Kishi T, Matsunaga S, Oya K, Nomura I, et al. Memantine for Alzheimer's disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 60: 01-425.

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive peroxides as potential therapeutic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 223–251.

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Ermolenko, E.; Savidov, N.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V. Antiprotozoal and antitumor activity of natural polycyclic endoperoxides: Origin, structures and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 686.

- Vil, V.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Poroikov, V.V.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Savidov, N.; Dembitsky, V.M. Peroxy steroids derived from plants and fungi and their biological activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7657–7667.

- Dembitsky, V.M. Antitumor and hepatoprotective activity of natural and synthetic neo-steroids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020, 79, 101048.

- Zhang, S.; He, B.; Qu-Bie, A.; Li, M.; Luo, M.; Feng, M.; Liu, Y. Endoperoxidases in biosynthesis of endoperoxide bonds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 136, 136806.

- Clennan, E.L. Aromatic endoperoxides. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 99, 204–220.

- Paul, S.; Konig, M.F.; Pardoll, D.M.; Bettegowda, C.; Papadopoulos, N.; Wright, K.M.; Zhou, S. Cancer therapy with antibodies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 399–426.

- Segura-Quezada, L.A.; Torres-Carbajal, K.R.; Satkar, Y.; et al. Oxidative halogenation of arenes, olefins and alkynes mediated by iodine(III) reagents. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2021, 18, 159–172.

- Grover, N.; Senge, M.O. Synthetic advances in the C–H activation of rigid scaffold molecules. Synthesis 2020, 52, 3295–3325.

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Dzhemileva, L.; Gloriozova, T.; D’yakonov, V. Natural and synthetic drugs used for the treatment of dementia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 524, 772–783.

- Beinert, H. Iron–sulfur proteins: Ancient structures, still full of surprises. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 5, 2–15.

- Bian, S.; Cowan, J.A. Protein-bound iron–sulfur centers: Form, function, and assembly. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 190, 1049–1066.

- Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Manessi-Zoupa, E.; Escuer, A.; Perlepes, S.P. The sulfate ligand as a promising “player” in 3d-metal cluster chemistry. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2009, 362, 634–650.

- Eaton, P.E.; Pramod, K.; Gilardi, R. Cubanourea: A cubane–propellane. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 5746–5750.

- Shiraishi, T.; Kuzuyama, T. Biosynthetic pathways and enzymes involved in the production of phosphonic acid natural products. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 42–52.

- Schwartz, D.; Recktenwald, J.; Pelzer, S.; Wohlleben, W. Isolation and characterization of the PEP-phosphomutase and phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase genes from the phosphinothricin tripeptide producer Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998, 163, 149–157.

- Ramos-Figueroa, J.S.; Palmer, D.R.; Horsman, G.P. Phosphoenolpyruvate mutase-catalyzed C–P bond formation: Mechanistic ambiguities and opportunities. ChemBioChem 2022, 23, e202200285.

- Villarreal-Chiu, J.F.; Quinn, J.P.; McGrath, J.W. The genes and enzymes of phosphonate metabolism by bacteria and their distribution in the marine environment. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 19.

- Horsman, G.P.; Zechel, D.L. Phosphonate biochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5704–5783.

- Nowack, B. Environmental chemistry of phosphonates. Water Res. 2003, 37, 2533–2546.

- Kononova, S.V.; Nesmeyanova, M.A. Phosphonates and their degradation by microorganisms. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2002, 67, 184–195.

- Galezowska, J.; Gumienna-Kontecka, E. Phosphonates, their complexes and bio-applications: A spectrum of surprising diversity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 105–124.

- Brown, A.C.; Fraser, T.R. The connection of chemical constitution and physiological action. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 1868, 25, 224–242.

- Cros, A.F.A. Action de l'Alcohol Amylique sur l'Organisme; University of Strasbourg: Strasbourg, France, 1863.

- Muratov, E.N.; Bajorath, J.; Sheridan, R.P.; Tetko, I.V.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. QSAR without borders. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3525–3564.

- Lagunin, A.; Stepanchikova, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. PASS: Prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 747–748.

- Dembitsky, V.M. Highly oxygenated cyclobutane rings in biomolecules: Insights into structure and activity. Oxygen 2024, 4, 181–235.

- Dembitsky, V.M. Steroids bearing heteroatoms as potential drugs for medicine. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2698.

- Dembitsky, V.M. Bioactive steroids bearing oxirane rings. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2237.

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Terent’ev, A.O. Azo dyes and the microbial world: Synthesis, breakdown, and bioactivity. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 100.

- Anzali, S.; Barnickel, G.; Cezanne, B.; Krug, M.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. Discriminating between drugs and nondrugs by prediction of activity spectra for substances (PASS). J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 2432–2437.

- Stepanchikova, A.; Lagunin, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. Prediction of biological activity spectra for substances: Evaluation on diverse sets of drug-like structures. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 225–233.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).