Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The networked nature of interbank connections creates vulnerability to systemic risk, which arises from inter-dependencies caused by common asset holdings when faced with exogenous negative shocks. This paper employs Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs) to reconstruct the network system of asset-holding correlations from the balance sheets of Chinese commercial banks from 2016 to 2022. The reconstructed network is designed to accurately mimic the topology of the real banking system. Subsequently, a novel framework for measuring aggregate network vulnerability is applied. This framework incorporates factors such as bank size, initial shocks, connectedness, leverage, and asset fire sales to identify financial contagion effects. The findings indicate that the reconstructed network system exhibits a good fit to real-world data in both its linkage structure and weight distribution. Furthermore, the cumulative aggregate vulnerability of the network increases non-linearly with the magnitude of the initial shock and the discount level of asset fire sales. The indirect vulnerability for individual banks, resulting from risk contagion triggered by deleveraging and fire sales, is substantially higher than the direct losses from initial shocks. The risk contribution to systemic vulnerability is concentrated in large state-owned banks and national joint-stock commercial banks. In contrast, the institutions most affected by risk shocks are predominantly small and medium-sized rural and urban commercial banks.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

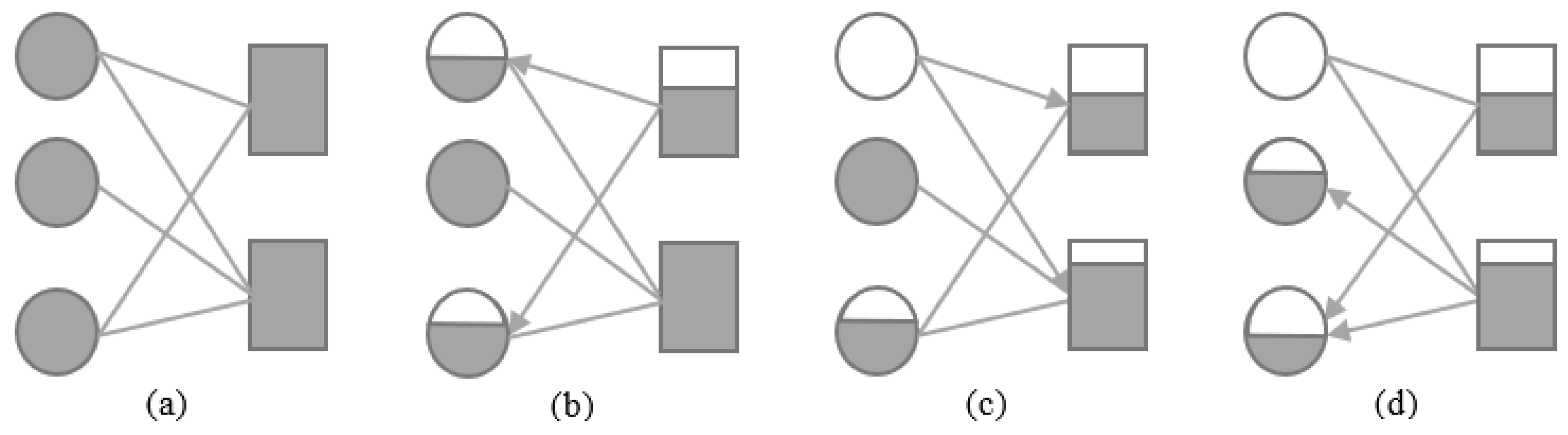

2.1. Network reconstruction

2.2. Network reconstruction

3. Data and Network

3.1. Data and network index

3.2. Data and network index

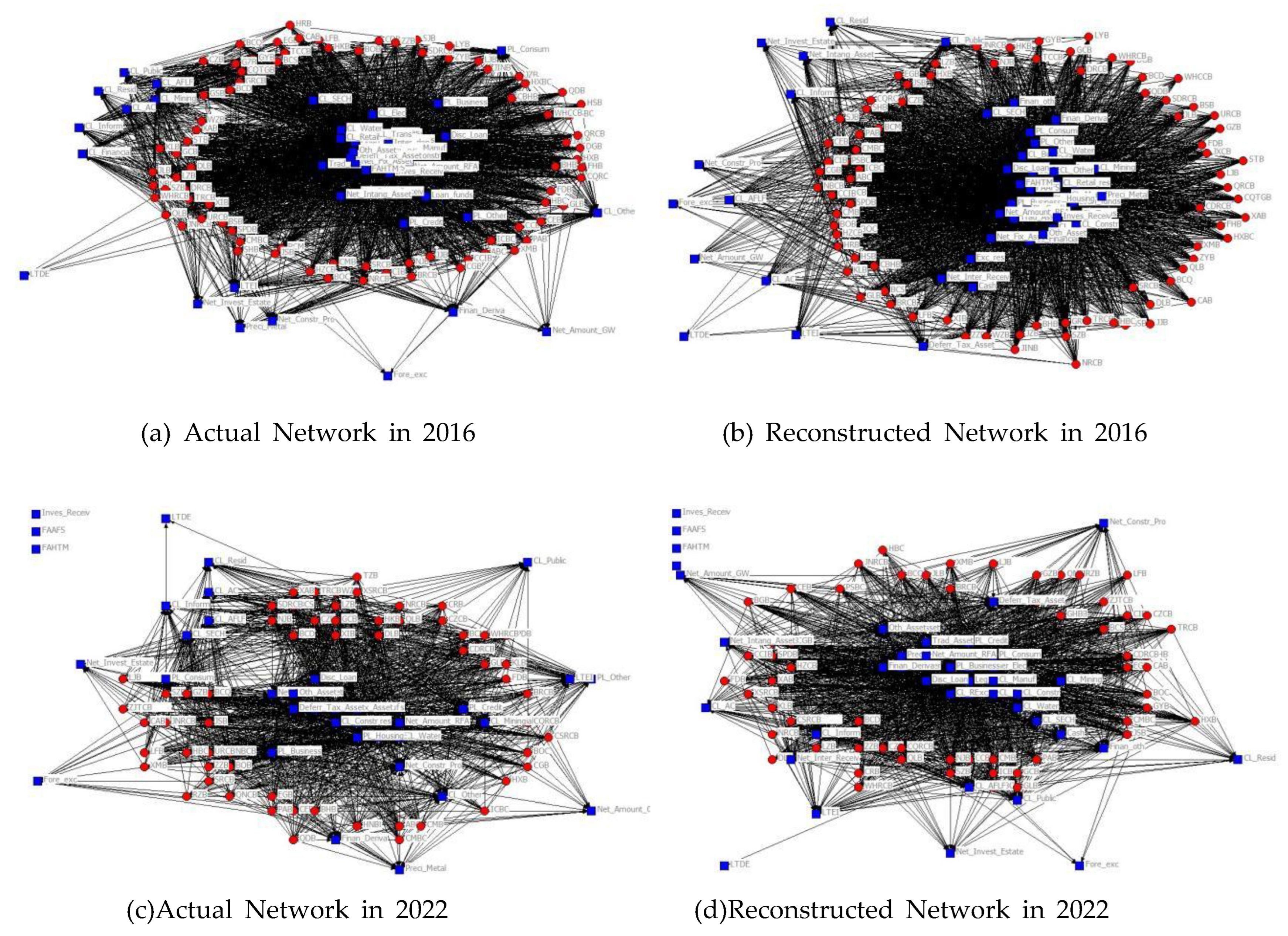

3.2.1. Topology structure

3.2.2. Topology analysis

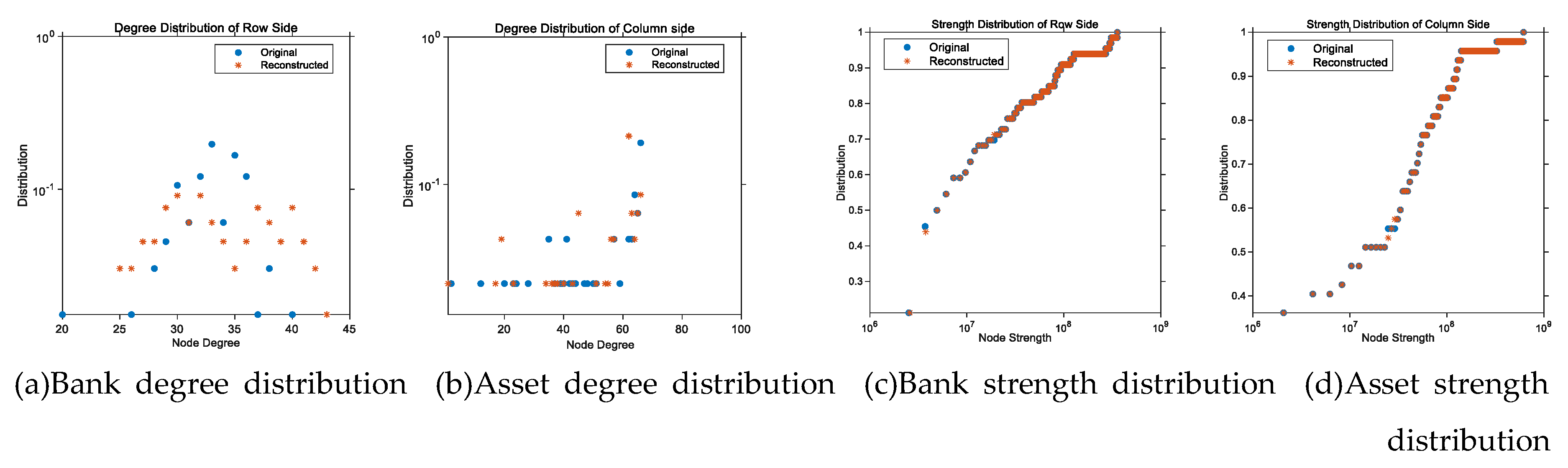

- Degree distribution and Strength distribution

- 2.

- Network density, clustering coefficient, and degree correlation

- 3.

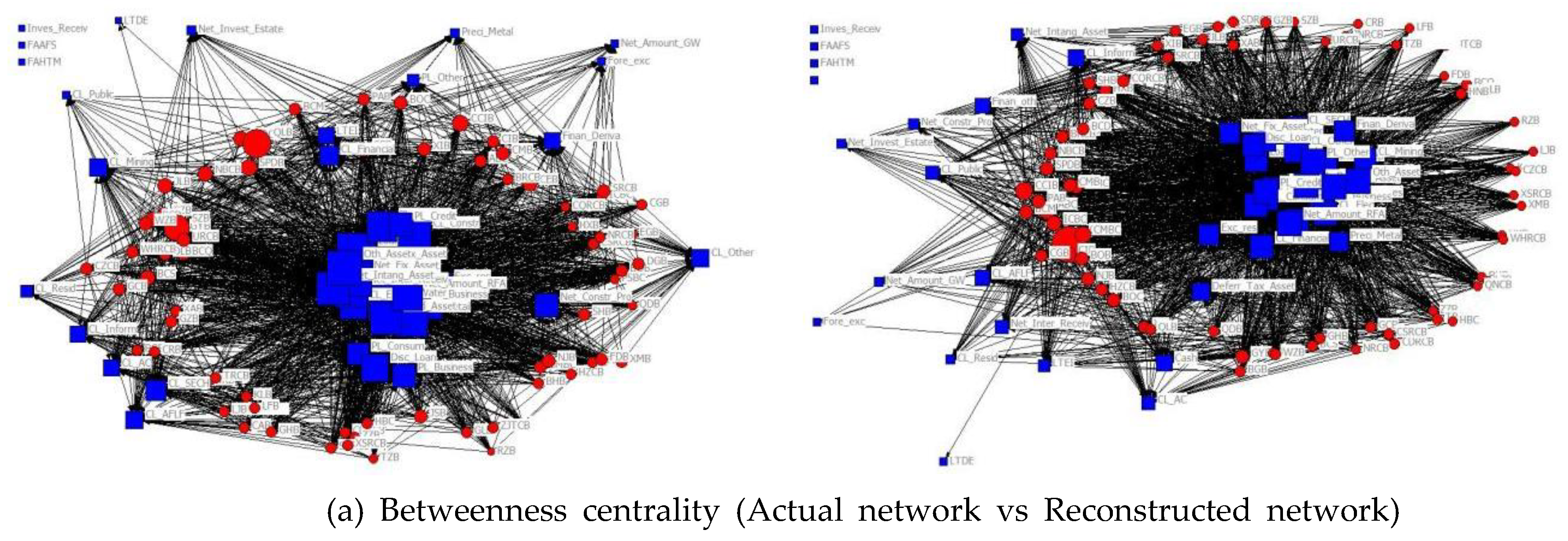

- Betweenness centrality, Closeness centrality, and Eigenvector centrality

- 4.

- Asset concentration

3.2.3. Similarity measurement

4. Simulation Study

4.1. Measuring network aggregate vulnerability

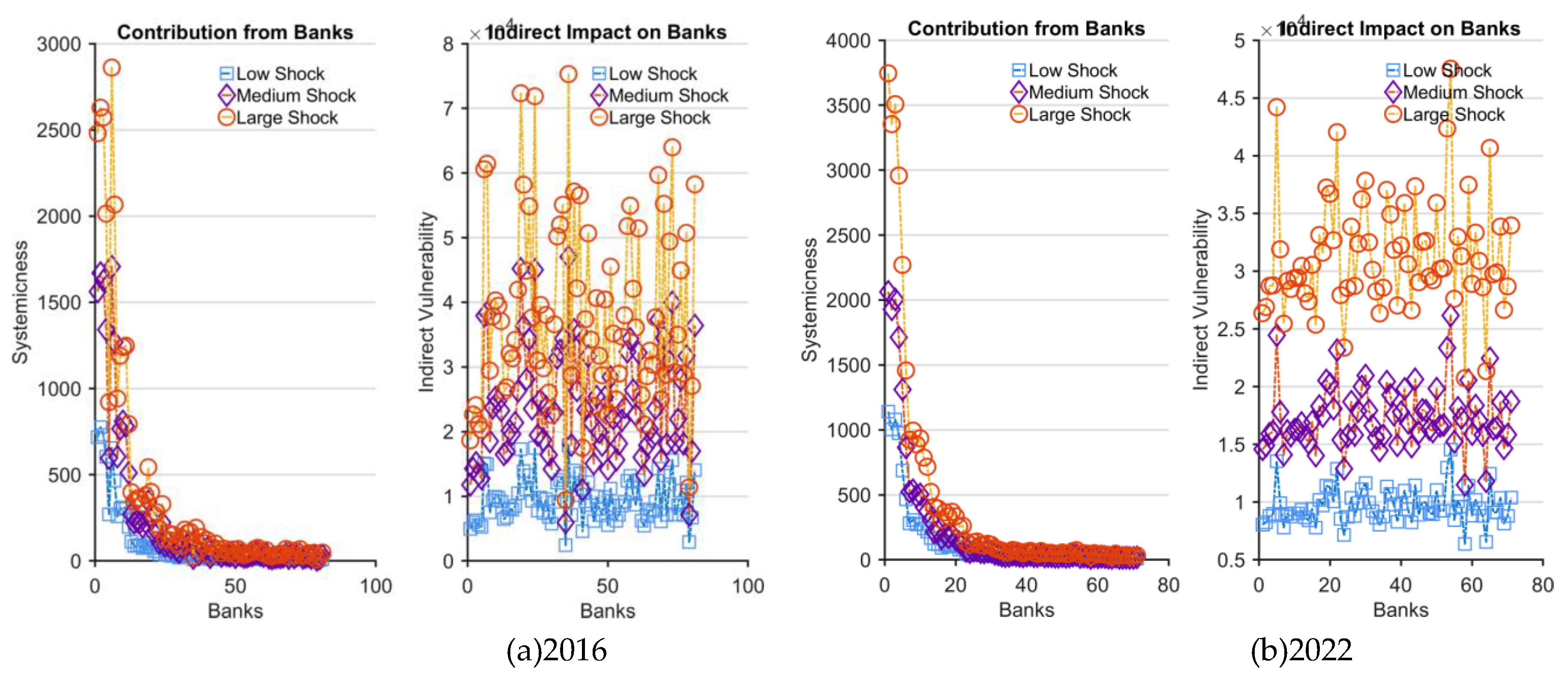

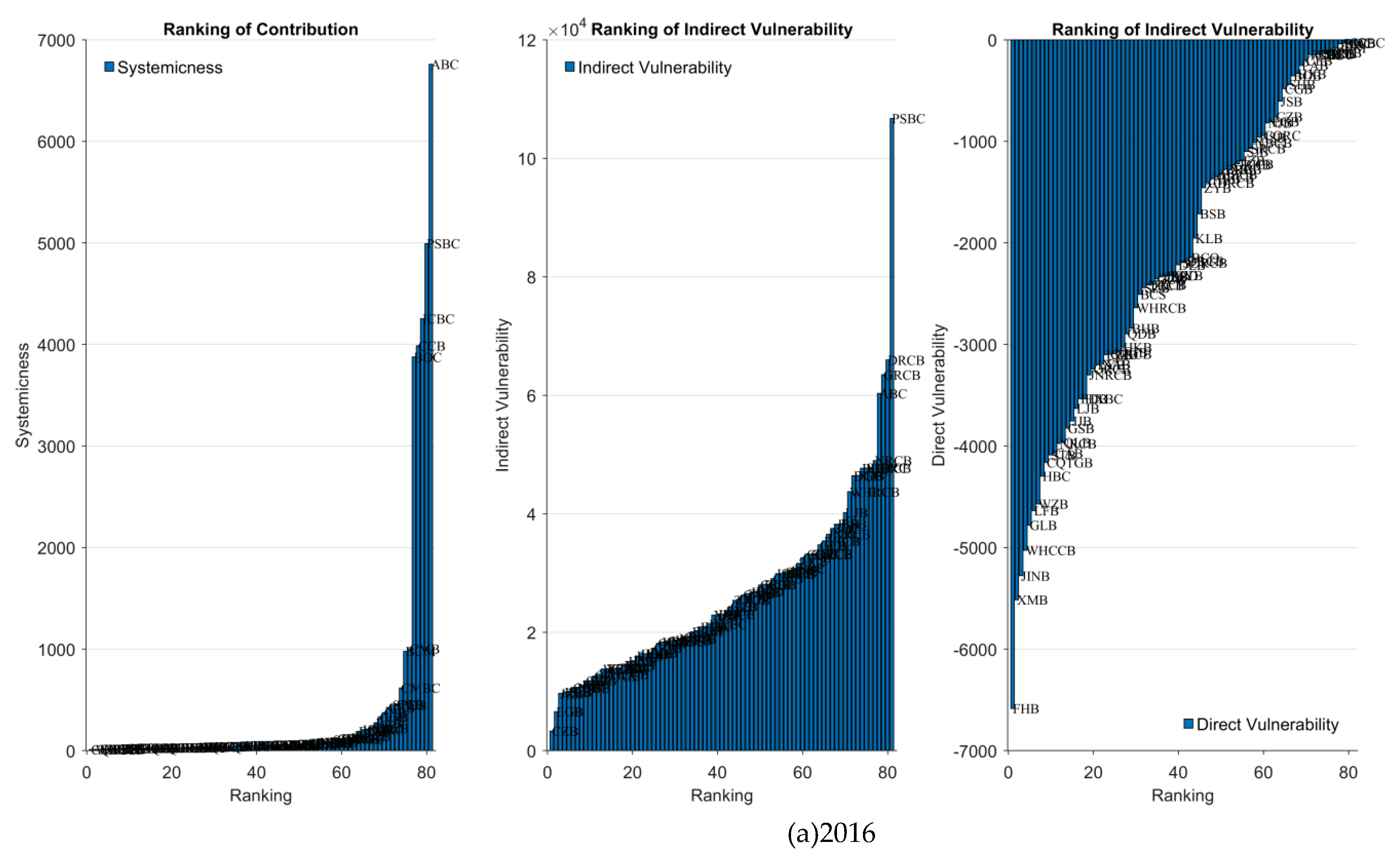

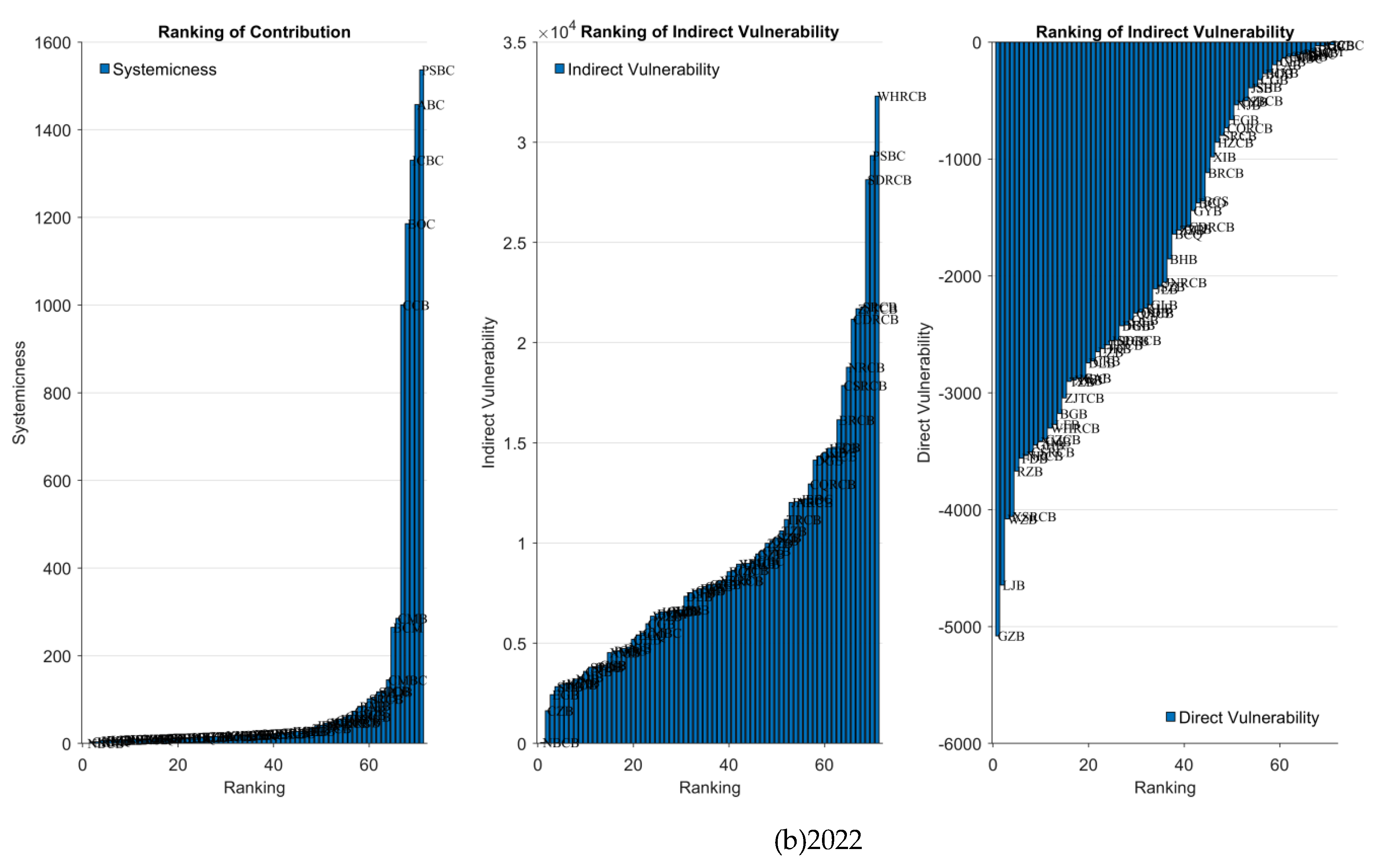

4.2. Contribution from each bank to network vulnerability

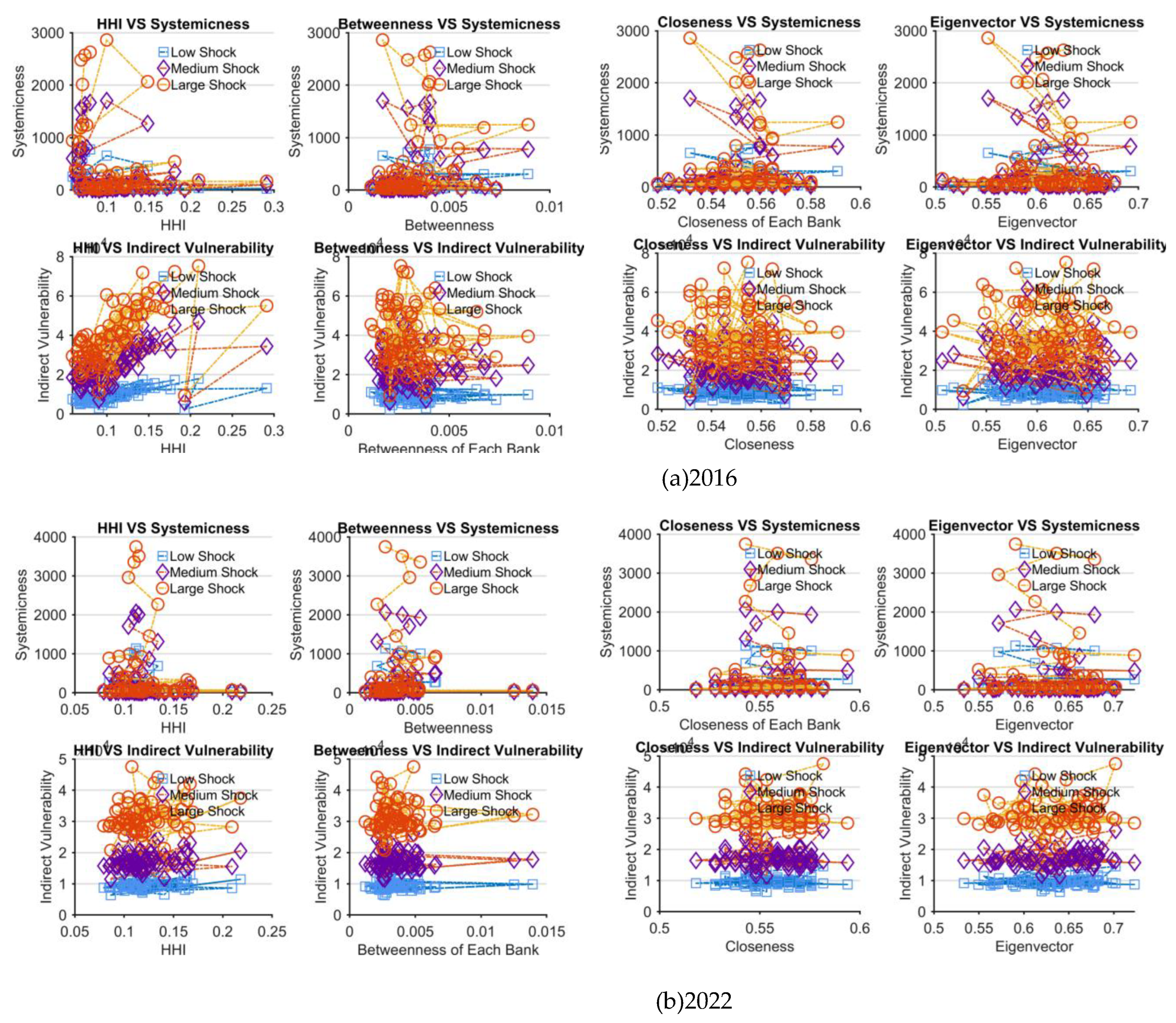

4.3. Network topology structure on network vulnerability

4.4. Impact of risk contagion on individual banks

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Bank Abbreviation | Bank Name | Category |

|---|---|---|

| ICBC | Industrial and Commercial Bank of China | State-Owned Large Commercial Bank |

| CCB | China Construction Bank | State-Owned Large Commercial Bank |

| ABC | Agricultural Bank of China | State-Owned Large Commercial Bank |

| BOC | Bank of China | State-Owned Large Commercial Bank |

| PSBC | Postal Savings Bank of China | State-Owned Large Commercial Bank |

| BCM | Bank of Communications | State-Owned Large Commercial Bank |

| CMB | China Merchants Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| SPDB | Shanghai Pudong Development Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CIB | China's Industrial Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CCIB | China CITIC Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CMBC | China Minsheng Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CEB | China Everbright Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| PAB | Ping An Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| HXB | Huaxia Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CGB | China Guangfa Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CZB | China Zheshang Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| CBHB | China Bohai Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| EGB | Evergrowing Bank | National Joint-Stock Commercial Bank |

| BOB | Bank of Beijing | City Commercial Bank |

| SHB | Bank of Shanghai | City Commercial Bank |

| JSB | Bank of Jiangsu | City Commercial Bank |

| NBCB | Bank of Ningbo | City Commercial Bank |

| NJB | Bank of Nanjing | City Commercial Bank |

| SJB | Shengjing Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| HZCB | Bank of Hangzhou | City Commercial Bank |

| HSB | Huishang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| XIB | Xiamen International Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| TCCB | Tianjin City Commercial Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| JZB | Bank of Jinzhou | City Commercial Bank |

| HRB | Harbin Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| ZYB | Bank of Zhongyuan | City Commercial Bank |

| BSB | Baoshang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| BCS | Bank of Changsha | City Commercial Bank |

| BCD | Bank of Chengdu | City Commercial Bank |

| GCB | Bank of Guangzhou | City Commercial Bank |

| GYB | Bank of Guiyang | City Commercial Bank |

| BCQ | Bank of Chongqing | City Commercial Bank |

| JXCB | Bank of Jiangxi | City Commercial Bank |

| ZZB | Bank of Zhengzhou | City Commercial Bank |

| QDB | Bank of Qingdao | City Commercial Bank |

| HKB | Bank of Hankou | City Commercial Bank |

| JLB | Bank of Jilin | City Commercial Bank |

| DLB | Bank of Dalian | City Commercial Bank |

| DGB | Bank of Dongguan | City Commercial Bank |

| HXBC | Huarong Xiangjiang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| BHB | Bank of Hebei | City Commercial Bank |

| SZB | Bank of Suzhou | City Commercial Bank |

| GLB | Bank of Guilin | City Commercial Bank |

| LZB | Bank of Lanzhou | City Commercial Bank |

| GSB | Gansu Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| LJB | Longjiang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| QLB | Qilu Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| GZB | Guizhou Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| JJB | Jiujiang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| KLB | Kunlun Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| GHB | Guangdong Huaxing Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| CAB | Chang’an Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| FDB | Fudian Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| XAB | Xi’an Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| HBC | Hubei Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| HNB | Hunan Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| BGB | Guangxi Beibu Gulf Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| WZB | Wenzhou Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| XMB | Xiamen Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| LYB | Luoyang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| CZCB | Zhejiang Chouzhou Commercial Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| CQTGB | Chongqing Three Gorges Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| CRB | China Resources Bank of Zhuhai | City Commercial Bank |

| LFB | Langfang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| STB | Sichuan Tianfu Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| WHCCB | Weihai City Commercial Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| JINB | Jinshang Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| GZB | Ganzhou Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| RZB | Rizhao Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| FHB | Fujian Haixia Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| CSRCB | Changshu Rural Commercial Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| TZB | Taizhou Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| BOTS | Bank of Tangshan | City Commercial Bank |

| BYK | Yingkou Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| UCCB | Urumqi City Commercial Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| ZJTCB | Zhejiang Tailong Commercial Bank | City Commercial Bank |

| CQRCB | Chongqing Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| SRCB | Shanghai Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| BRCB | Beijing Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| GRCB | Guangzhou Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| DRCB | Dongguan Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| CDRCB | Chengdu Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| JNRCB | Jiangnan Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| QNCB | Qingdao Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| SDRCB | Shunde Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| QRCB | Qingdao Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| TRCB | Tianjin Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| WHRCB | Wuhan Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| URCB | United Rural Cooperative Bank Of Hangzhou | Rural Commercial Bank |

| NRCB | Nanhai Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| XSRCB | Xiaoshan Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

| ZJRCB | Zijin Rural Commercial Bank | Rural Commercial Bank |

References

- Acemoglu, D.; Ozdaglar, A.; Tahbaz-Salehi, A. Systemic risk and stability in financial networks. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 564–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Colliard, J.E.; Hurlin, C.; et al. Where the risks lie: A survey on systemic risk. Rev. Financ. 2017, 21, 109–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Gale, D. Financial contagion. J. Polit. Econ. 2000, 108, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nier, E.; Yang, J.; Yorulmazer, T.; et al. Network models and financial stability. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2007, 31, 2033–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistrulli, P.E. Assessing financial contagion in the interbank market: Maximum entropy versus observed interbank lending patterns. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calomiris, C.W.; Carlson, M. Interbank networks in the national banking era: Their purpose and their role in the panic of 1893. J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 125, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardoscia, M.; Barucca, P.; Battiston, S.; et al. The Physics of Financial Networks. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Rubens, S.D.S.S.; Tabak, B.M. Network structure analysis of the Brazilian interbank market. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2016, 26, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, P.; Sarlin, P.; Spelta, A. The interconnected nature of financial systems: Direct and common exposures. J. Bank. Financ. 2017, 112, 105149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, M.; Elsinger, H.; Summer, M.; et al. The Network Topology of the Interbank Market. Quant. Financ. 2004, 4, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelyveld, I.V.; Liedorp, F. Interbank Contagion in the Dutch Banking Sector: A Sensitivity Analysis. MPRA Pap. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, Y. Financial networks: contagion, commitment, and private sector bailouts. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 2925–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, P.; Kapadia, S. Contagion in financial networks. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 466, 2401–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladley, D. Contagion and risk-sharing on the inter-bank market. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2013, 37, 1384–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, R.; Tedeschi, G.; Gallegati, M. Bank interlinkages and macroeconomic stability. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2014, 34, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F.; Eisenbach, T.M. Fire-sale Spillovers and Systemic Risk. J. Financ. 2021, 76, 1251–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Vodenska, I.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E. Cascading failures in bipartite graphs: Model for systemic risk propagation. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Carciente, S.; Kenett, D.Y.; Avakian, A.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. Dynamical macroprudential stress testing using network theory. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 59, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccioli, F.; Shrestha, M.; Moore, C.; Farmer, J.D. Stability analysis of financial contagion due to overlapping portfolios. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 46, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccioli, F.; Farmer, J.D.; Foti, N.; Rockmore, D. Overlapping portfolios, contagion, and financial stability. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2015, 51, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Landier, A.; Thesmar, D. Vulnerable banks. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, J.; Lepore, C.; Schaanning, E. Taking Regulation Seriously: Fire Sales Under Solvency and Liquidity Constraints. Bank Engl. Res. Pap. Ser. 2019, No. 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, C.; Fricke, D. Vulnerable asset management? The case of mutual funds. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 52, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, G.; Hanley, K.W.; Nikolova, S.; Pelizzon, L.; Sherman, M.G. Portfolio similarity and asset liquidation in the insurance industry. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.; Noss, J.; Vause, N. The impact of Solvency II Regulations on Life Insurers’ Investment Behaviour. Bank Engl. Staff Work. Pap. 2017, No. 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barucca, P.; Bardoscia, M.; Caccioli, F.; et al. Network valuation in financial systems. Math. Financ. 2021, 30, 1180–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccioli, F.; Ferrara, G.; Ramadiah, A. Modelling fire sale contagion across banks and non-banks. J. Financ. Stab. 2024, 71, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.; van Lelyveld, I.; Banai, Á.; et al. The missing links: A global study on uncovering financial network structures from partial data. J. Financ. Stab. 2018, 35, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squartini, T.; Almog, A.; Caldarelli, G.; et al. Enhanced capital-asset pricing model for the reconstruction of bipartite financial networks. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 032315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gangi, D.; Lillo, F.; Pirino, D. Assessing systemic risk due to fire sales spillover through maximum entropy network reconstruction. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2018, 94, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, A.; Veraart, L.A.M. Adjustable network reconstruction with applications to CDS exposures. J. Multivar. Anal. 2019, 172, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadiah, A.; Caccioli, F.; Fricke, D. Reconstructing and stress testing credit networks. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2020, 111, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, T.; Shin, H.S. Liquidity and leverage. J. Financ. Intermed. 2010, 19, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Number of Banks | 81 | 83 | 76 | 77 | 73 | 66 | 71 |

| Category of Asset | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 |

| Indicator | Symbol | Description | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | D | Number of indirect links as a ratio of the total number of edges (excluding self-loops) | [0,1] |

| Degree | k | Sum of the actual number of edges | [0,∞] |

| Strength | s | Sum of the edge weights between nodes in the network | [0,∞] |

| Degree Distribution | P(k) | Probability distribution of node degree | [0,1] |

| Strength Distribution | P(s) | Probability distribution of node weight | [0,1] |

| Clustering Coefficient | C | The degree to which nodes in a graph tend to cluster together, which is defined as the number of closed triplets (any three nodes with links between all three) over the total number of triplets (including triplets with one link missing) in indirect network | [0,1] |

| Degree Correlation | r | Connectivity tendency between nodes with different eigenvalue | [[-1,1] |

| Betweenness Centrality | B | Extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths between pairs of other nodes in a network, to measure nodes’ importance | [0,1] |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index | HHI | Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of both banks and assets is defined as the sum of the squared allocation. | [0,1] |

| Year | Size | k | D | C | r | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autual Network | 2016 | 81×47 | 2850 | 22.27 | 35.19 | 60.64 | 0.75 | 0.73 | -0.70 |

| 2017 | 83×47 | 2923 | 22.48 | 35.22 | 62.19 | 0.75 | 0.73 | -0.71 | |

| 2018 | 76×47 | 2642 | 21.48 | 34.76 | 56.21 | 0.74 | 0.71 | -0.66 | |

| 2019 | 77×47 | 2593 | 20.91 | 33.68 | 55.17 | 0.72 | 0.71 | -0.63 | |

| 2020 | 73×47 | 2466 | 20.55 | 33.78 | 52.47 | 0.72 | 0.72 | -0.61 | |

| 2021 | 66×47 | 2164 | 19.15 | 32.79 | 46.04 | 0.70 | 0.71 | -0.63 | |

| 2022 | 71×47 | 2373 | 20.11 | 33.42 | 50.49 | 0.71 | 0.73 | -0.67 | |

| Reconstruted Network | 2016 | 81×47 | 2904 | 22.69 | 35.85 | 61.79 | 0.76 | 0.75 | -0.72 |

| 2017 | 83×47 | 2990 | 23.00 | 36.02 | 63.62 | 0.77 | 0.75 | -0.74 | |

| 2018 | 76×47 | 2710 | 22.03 | 35.66 | 57.66 | 0.76 | 0.75 | -0.70 | |

| 2019 | 77×47 | 2665 | 21.49 | 34.61 | 56.70 | 0.74 | 0.72 | -0.69 | |

| 2020 | 73×47 | 2545 | 21.21 | 34.86 | 54.15 | 0.74 | 0.73 | -0.66 | |

| 2021 | 66×47 | 2224 | 19.68 | 33.70 | 47.32 | 0.72 | 0.73 | -0.68 | |

| 2022 | 71×47 | 2426 | 20.56 | 34.17 | 51.62 | 0.73 | 0.75 | -0.72 |

| Category | Metric | Description | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Link-based | Jaccard score | Inverse of the number of links belonging to the original and reconstructed networks divided by the number of links that belong to at least one network | [0,1] |

| Exposure-based | Cosine measure | Cosine of the angle between the original and reconstructed networks | [0,1] |

| Year | Jaccard score | Cosine measure |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| 2017 | 0.70 | 0.92 |

| 2018 | 0.69 | 0.95 |

| 2019 | 0.65 | 0.96 |

| 2020 | 0.66 | 0.95 |

| 2021 | 0.72 | 0.96 |

| 2022 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| Year | Bank | Bank | Year | Bank | Bank | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | ABC | 6759.25 | PSBC | 106722.6 | 2022 | PSBC | 1536.424 | WHRCB | 32305.64 |

| PSBC | 4992.9 | DRCB | 65951.36 | ABC | 1457.434 | PSBC | 29333.99 | ||

| ICBC | 4253.748 | GRCB | 63469.6 | ICBC | 1330.509 | SDRCB | 28132.12 | ||

| CCB | 3986.976 | ABC | 60310.09 | BOC | 1185.45 | SRCB | 21789.19 | ||

| BOC | 3876.179 | NRCB | 48963.01 | CCB | 1000.414 | ZJTCB | 21695.56 | ||

| CMB | 1003.02 | CQRC | 47742.72 | CMB | 285.396 | CDRCB | 21173.36 | ||

| BCM | 979.4315 | SDRCB | 47726.79 | BCM | 264.6488 | NRCB | 18770.98 | ||

| CMBC | 617.5012 | BHB | 47678.8 | CMBC | 144.7064 | CSRCB | 17858.08 | ||

| CCIB | 456.0433 | FDB | 46448.13 | CCIB | 120.0027 | BRCB | 16145.62 | ||

| SPDB | 450.7068 | DGB | 46423.7 | SPDB | 117.7803 | FDB | 14782.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).