1. Introduction

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Western countries immediately imposed SWIFT sanctions against major Russian banks on February 26, 2022 that went into effect in March of that year. The sanctions were three-fold: first to disconnect major Russian banks from using SWIFT transfers of reserve currencies, second, to freeze $320 billion in Russian sovereign assets held abroad, with the largest share, approximately (€194 billion) held in Belgium’s Euroclear system, and third, the U.S., EU, U.K., Canada, and other allies announced coordinated measures to freeze and seize assets belonging to sanctioned Russian oligarchs that began in March 2025. This included yachts, luxury real estate, private jets, and bank accounts linked to individuals close to the Kremlin. The aim was to degrade Russia’s ability to finance its war and trade internationally. The SWIFT sanctions were extended to Gazprombank on November 21, 2024, and further tightened after the first round.

De-dollarization had been taking place gradually, but the efforts accelerated not only due to the sanctions and freezing of assets, but also due to the Bagehot-like money issue the U.S. pursued during the Covid 19 Pandemic and the consequent rise in U.S. inflation. Bagehot’s dictum was not respected, however, forgivable loans and pure transfers were shoveled out the door irrespective of the creditworthiness of the borrowers and recipients.

Dollarization is ultimately the result of the “Triffin Dilemma.” Triffin (1960) noted that a country whose currency is the global reserve currency must supply the world with its currency is required to run a perennial trade deficit, which ultimately threatens its convertibility. However, when the dollar’s convertibility into gold was questioned, the world chose the dollar rather than gold as its medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value. In the form of U.S. Treasuries, the dollar paid a yield above the expected rate of inflation. In terms of transactions, currency and bank dollars are more liquid as a medium of exchange, and the dollar is a simpler unit of account for invoicing.

Nevertheless, as a result of sanctions and seizures of assets, negative real rates on Treasuries, relative dollar depreciation, and the Trump tariffs creating volatility in trade patterns, there has been an active effort to de-dollarize by substituting other assets, notably by the BRICs countries. In addition, some de-dollarization takes place passively by the appreciation of the other assets held as reserves when the dollar depreciates relative to gold and the other assets. The purpose of this study is to estimate the degree of de-dollarization that has taken place in the past decade, both actively and passively.

While there has been much ink spilt on de-dollarization, the evidence suggests that it is a slow, gradual process. Ize & E. Levy Yeyati, (2006), focus on motives of unit of account, usefulness in transactions, and store of value. They analyze both currency substitution for transactions) and asset substitution (for savings and investment). While sanctions seizures and inflation do not play an important role since their study pre-dates these events, Ize and Levy Yeyati find that de-dollarization is a slow process: there was little movement toward the other reserve currencies such as the euro the pound and the yen despite dollar depreciation. Middlebrook & Tadaa (2025) use panel regressions to estimate the impact of inflation interest rate differentials and exchange rate regimes on dollarization ratios. They also find gradual systemic shifts rather than immediate empirical movements in reserves.

Quintana (2025) illustrates the staying power of the dollar in invoicing, transactions, and as a store of value: “Dollar dominance, understood as the outsized role of the U.S. dollar in the global economy, is often traced to the ‘legalised‘ institutional settlement of BrettonWoods, which codified and entrenched the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency.” He argues that “… even in the post-Bretton Woods international monetary system, the global dominance of the US dollar should be understood not as an economic inevitability, but as a set of legal norms, practices, and institutional arrangements that sustains unequal global relations.” Efforts to dollarize include “… bilateral currency swap agreements, diversification of reserve currencies, the promotion and use of local currencies in trade, the adoption of new forms of multilateral development lending, and the development of alternative payment infrastructures, notably employing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). These developments are not purely economic strategies; they are grounded in various legal arrangements, ranging from international agreements to central bank directives, as well as in modes of legal decision-making, discussion, and practice, which are at the core of international financial regulation. from international agreements to central bank directives, as well as in modes of legal decision-making, discussion, and practice, which are at the core of international financial regulation.” Quintana (2025).

2. Materials and Methods

We gather data on the top ten reserve holders by central banks, as ranked by their physical gold holdings in metric tons, excluding the U.S. We report or estimate their U.S. dollar holdings in bonds, assets, and currency, as well as the value of their reported gold reserves in 2015 and 2025. Other assets in terms of reserve currencies such as the pound, the euro, or the yen and any other assets or currencies are treated as a residual in that total reserves are reported in USD, so we deduct the value of dollar and gold reserves in from the total to report “other” reserves.

As a simple valuation problem, the value of total reserves of a central bank are:

where all prices are in terms of USD so

, and the price of gold is in USD per metric tons. The

category stands for the value of all assets other than gold and dollars. For example, for holdings of euros, the price would be USD per euro times the stock of euros held. Naturally, the “other” category will include the sum of all other reserve assets – except gold and USD - times their individual price in dollars.

Clearly, dollar depreciation relative to other currencies and gold will act as de-dollarization since declines as and the price of other currencies and assets rise.

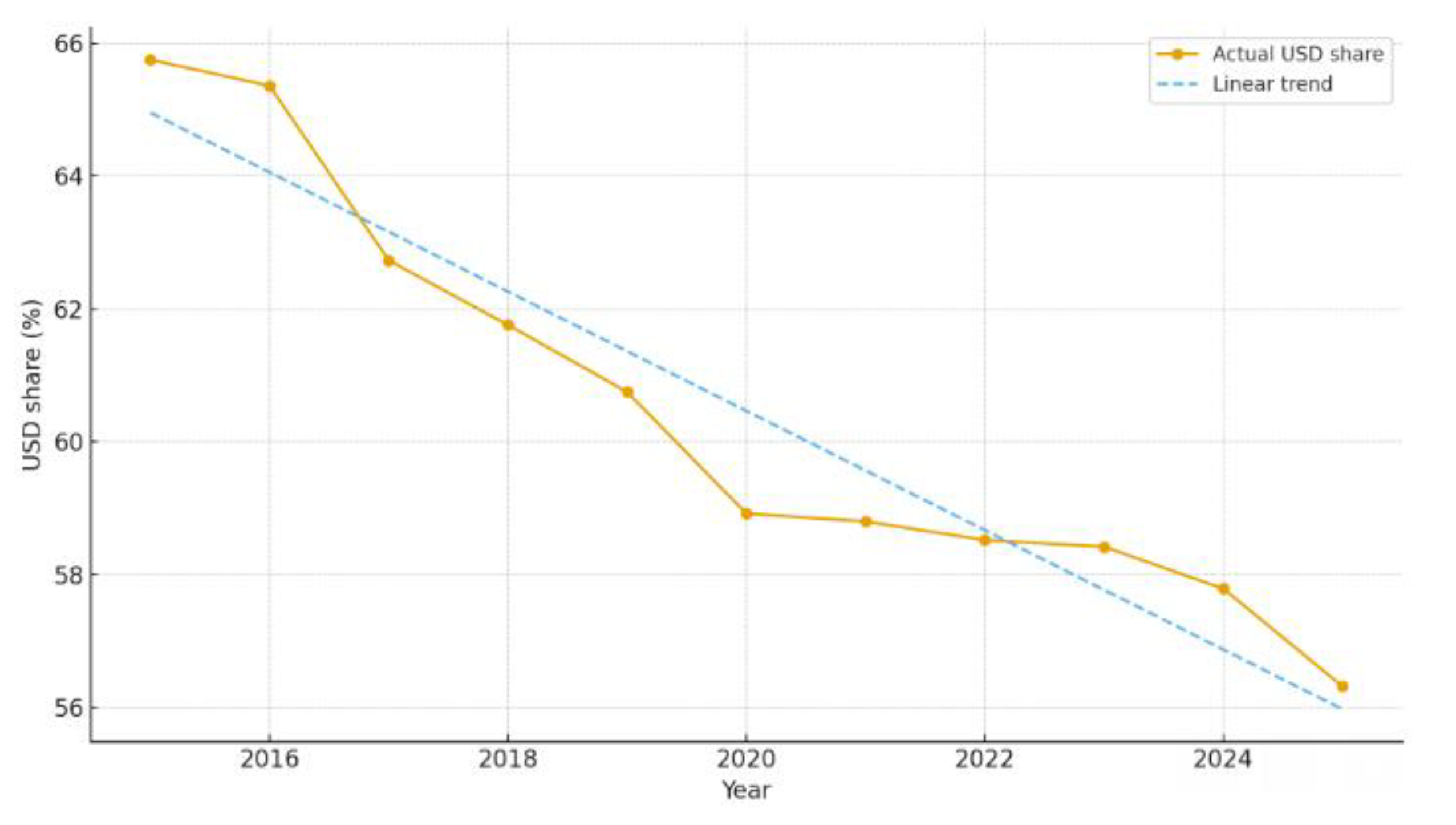

In

Figure 1, the global USD share falls nearly one

percentage points per year on average, an estimated 0.09. From 2015 to 2025: the global share of the USD falls from 66% to 56%, approximately 10%. The decline in the dollar share accelerated slightly after 2021. However, when we include gold as part of total reserves, the picture changes dramatically.

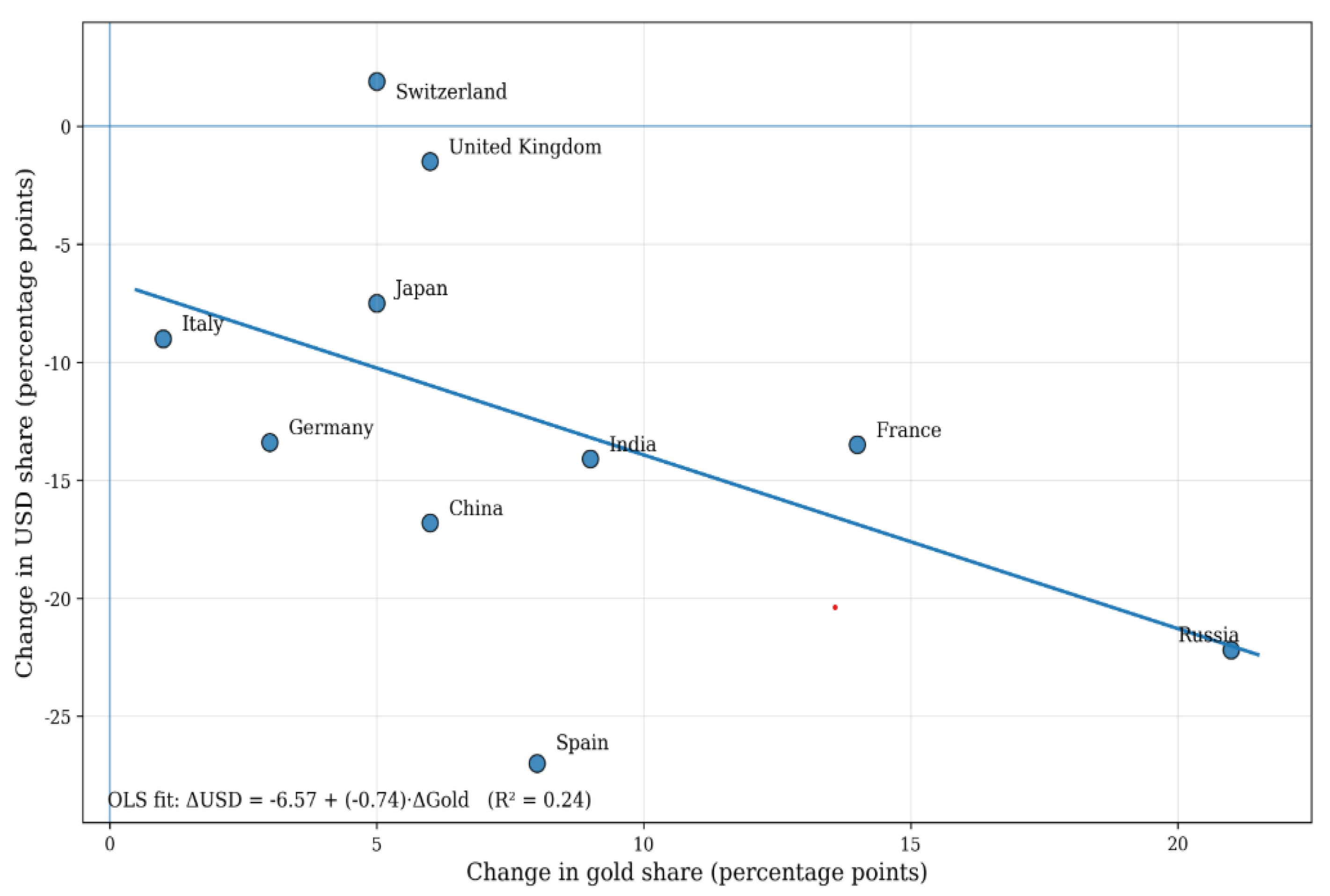

Figure 2 illustrates the change in the share of USD assets on the vertical axis and the change in the share of gold on the horizontal axis.

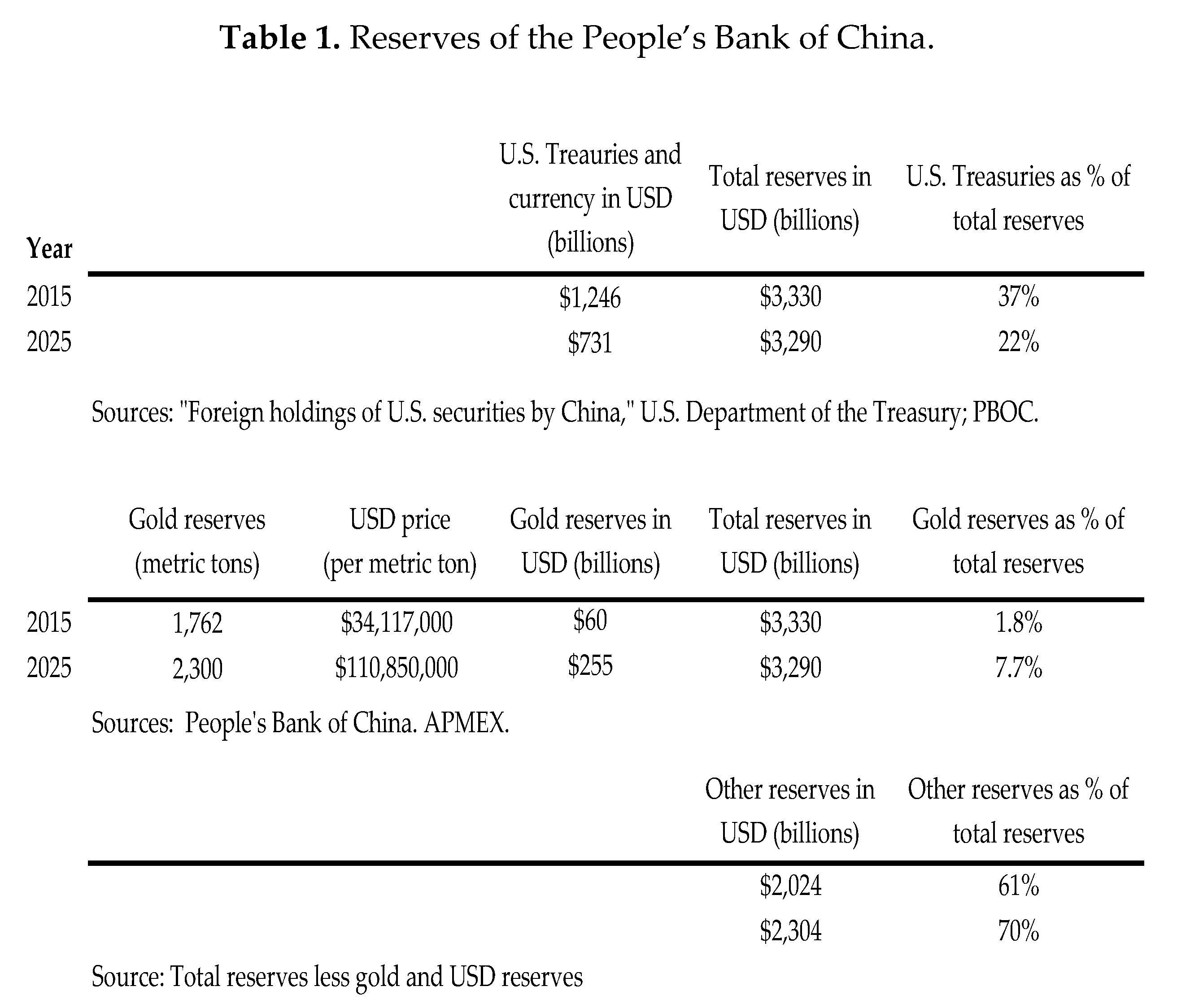

To illustrate the methodology, take China as an example.

Figure 2 breaks down the categories of reserves held by the People’s Bank of China into US Treasuries and USD currency, gold, and other reserves, including other reserve currencies.

China has actively de-dollarized by a net sale of US Treasuries $515 billion USD) and a net purchase of 538 metric tons of gold. The 225% increase in the dollar price of gold combined with a 31% increase resulted in a rise in the share of gold in total reserves.

The combined effect of dollar depreciation, the net sale of US Treasuries and the net purchase of gold resulted in a 15% fall in the percentage of USD assets from 37 to 22%. In the case of gold, the net purchase of gold and the rise in its price accounts for a 6% rise in gold’s share from 1.8% to 7.7%.

3. Results

The methodology is applied to the top 10 gold reserve holding countries globally, not including the U.S. The data and calculations for these countries are available upon request to the authors. In the case of estimations not based on publicly available data, the estimation procedures are reported.

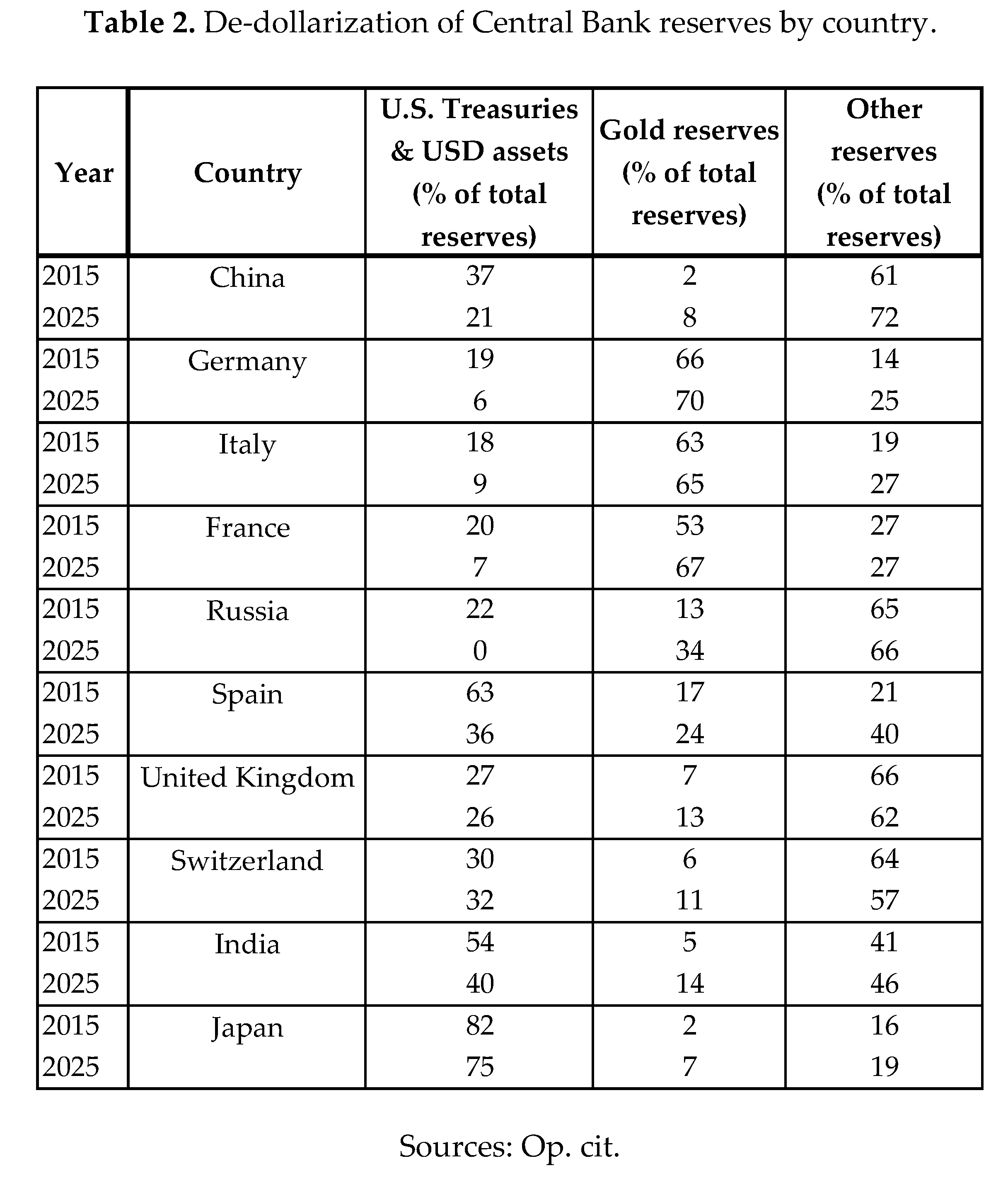

A summary of the key results on de-dollarization is provided in Table 2:

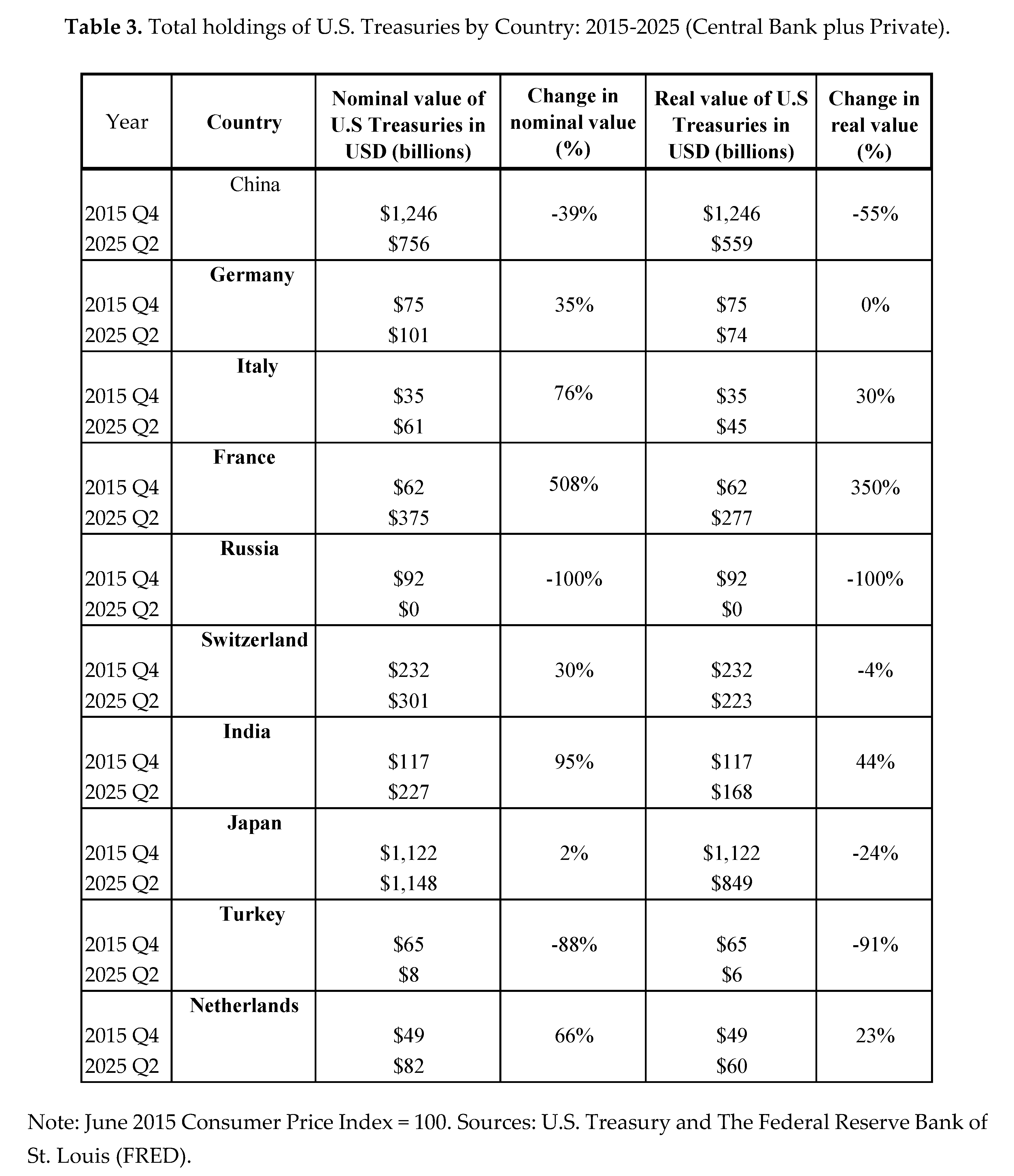

Finally, Table 3 reports price level adjusted real holdings of U.S. Treasuries held by both the central banks and private investors in each country. The purpose of this calculation is to measure the decline in the face value, i. e. the value of the Treasuries if redeemed.

Table 3 measures only the purchasing power of the bonds when the principal is redeemed, not including interest. Parenthetically, U.S. inflation exceeded interest paid on these bonds during the pandemic, 2021-2025.

4. Conclusions

Our results are compatible with previous author’s finding that de-dollarization by diversification to other reserve currencies, while ongoing, is gradual. Dollar depreciation and inflation is gradually taking its toll as well as sanctions. However, the dollar is likely to maintain its position as an invoice currency and in transfers via the SWIFT system, due to its roles as a unit of account and medium of payments. Nevertheless, gold is a threat to the dollar as a store of value. Bilateral currency swaps and alternative payments platforms are also gaining ground on the dollar.

All ten countries experienced a rise in the share of gold in their reserves, even those whose physical gold reserves did not change, namely Germany, Italy, and Spain. All but Switzerland experienced a fall in the share of the USD in reserves. On the other hand, gold’s share increased the most for those that had net purchases of physical gold, by Russia (906 metric tons), China (538 mt), India (322 mt), and Japan (81 mt) boosted also by the substantial rise in the dollar price of gold.

Author Contributions

The idea and methodology of this paper came mostly from Dr. Connolly, at the suggestion of the faculty at the MHBS named in the acknowledgements. The empirical investigation was conducted by Messrs. Chen and Yao. Connolly also wrote the first draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to their colleagues at the University of Miami MHBS, Miguel Iraola, Stefania Albanesi, and Noah Williams for their insightful comments in a brown bag seminar September 3, 2025, and to the editors for their support and encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bagehot, W. (1873). Lombard Street: A description of the money market, Henry S. King & Co.:1-359.

- Goldberg, L.S., and O. Hannaoui (2024). Drivers of dollar share in foreign exchange reserves, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report No. 1087, (February 26).

- Ito, H.; McCauley, R.N. The currency composition of foreign exchange reserves. BIS Working Paper No. 828; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ize, A. and E. Levy Yeyati, (2006). Financial de-dollarization: Is it for real?, IMF Working Paper No. 05/187, 1-31.Posted: March 3, 2006rization: Is it for real?

- Middlebrook, P. J. and Amba Tadaa (2025). The rise of China and de-dollarization in a multi-polar digital world, in: The Great Power Competition, Volume 6, Springer Nature Switzerland: 207-221. [CrossRef]

- Quintana, F. J. (2025). Dollar dominance, de-dollarization, and international law, Journal of International Economic Law, 2025, 28(3), 359–381, Oxford October 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Triffin, R., (1960). Gold and the Dollar Crisis; The Future of Convertibility. New Haven: Yale University Press: 3–14.

- Wong, A. (2007). Measurement and inference in international reserve diversification. Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper 07-6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).