Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) touches roughly one percent of the world’s population and exacts a heavy personal and economic toll [

1]. The hallucinations and delusions that dominate clinical charts are only half the story; equally disabling are the early-emerging deficits in memory, attention and executive control that shape a patient’s chances of finishing school, holding a job, or living independently [

2].

Genomic work has confirmed that SCZ is a textbook example of polygenicity. The latest mega-analyses from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium implicate hundreds of common variants, each exerting a tiny nudge on risk [

3]. Turning that long list of loci into a clear biological narrative, however, remains a major hurdle. At present, two developmental processes dominate the conversation.

First, growing evidence points to runaway synaptic pruning during adolescence. In a typical brain, complement proteins and microglia trim weak or redundant connections to streamline circuitry; in SCZ, the shears seem over-active, erasing too many synapses [

4,

5]. Second, a wealth of clinical and pre-clinical data supports the idea that NMDA-type glutamate receptors are under-active, weakening the long-term potentiation needed to stabilise new memories and working-memory traces [

6]. How these two pathways intersect—and how that intersection feeds into the cognitive decline so characteristic of SCZ—remains an open question [

7].

To probe the link, we revisited the PGC Wave 3 GWAS through three complementary lenses: MAGMA for gene-set enrichment, stratified LD-score regression for partitioning heritability, and transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) to infer expression effects. Our focus was genes that govern pruning and plasticity, which we then contrasted with results from a large intelligence GWAS [

8]; N = 269 867. Placing the two traits side by side allows us to pinpoint pathways that are unique to SCZ and to generate testable hypotheses about how mis-timed neurodevelopment may erode cognitive function in the disorder.

Methods

MAGMA Analysis

Summary statistics from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Wave 3 schizophrenia study [

3] were downloaded. The European file contains 7,659,767 autosomal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) taken from 53,386 cases and 77,258 controls, yielding an effective sample size of 58,749. The source file, distributed in VCF format, lists chromosome, variant ID, base-pair position, effect allele, reference allele and p-value. After confirming the layout, we extracted variant IDs, chromosomal coordinates and p-values. Variants on chromosomes X, Y and mitochondrial DNA were removed. A range check detected no p-values outside 0–1. Two text files—one with SNP positions, the other with p-values—were prepared for MAGMA.

Analyses used MAGMA v1.10 [

9]. SNPs were assigned to NCBI 37.3 gene boundaries extended 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream. Linkage disequilibrium was modelled with the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 European reference panel. Gene statistics were calculated with the sample-size option and N = 58,749.

Seven curated gene lists were examined. Two targeted glutamatergic neurotransmission (the original CGR panel with 23 genes in five functional groups and an expanded panel with 130 genes in 14 groups). Two addressed synaptic pruning (a shortened list of 38 genes in 10 categories and an expanded list of 262 genes in 25 categories). A pruning-specific list (225 genes) was generated by removing 37 genes shared between the expanded pruning and glutamate panels. Monoaminergic genes (101 genes in 11 categories) and housekeeping genes (182 genes in 10 categories) served as negative controls.

Competitive gene-set enrichment in MAGMA compares the mean Z-score of genes in a set with the genome-wide distribution while adjusting for gene length, SNP density and sample size. Significance was assessed with Bonferroni correction for seven tests (threshold 0.0071) and with the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR). Pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests contrasted target lists with control lists. Scripts and post-processing ran under Python 3 on Linux.

Genome-wide significance for individual genes was set at p < 2.7 × 10-6 (0.05/18,449). Genes with p < 0.001 were labelled suggestive and those with p < 0.05 nominal. Within each list, we recorded the mean Z-score, the count of nominal hits and the most significant gene; no further correction was applied to these descriptive figures.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis with LD Score Regression

We quantified the contribution of selected biological pathways to schizophrenia risk by applying stratified LD score regression [

10] to European-ancestry summary statistics from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium wave 3 genome-wide association study (effective N = 58,749; [

3]). The VCF file (7,659,767 autosomal SNPs) was screened for the required columns—chromosome, rsID, base-pair position, effect and non-effect alleles, sample size, and association Z-scores—and was reformatted into the five-column layout expected by LD-score tools. Variants on sex chromosomes and those with malformed p-values were removed, leaving only high-quality autosomal markers.

The same seven biologically informed gene lists were evaluated. For each list we generated a binary annotation by marking every 1000 Genomes European SNP [

11] that lay within the extended coordinates. Stratified LD score regression was then run with these custom annotations plus the baseline model supplied with LDSC. Enrichment was defined as the ratio of heritability attributable to annotated SNPs to the proportion of SNPs annotated. One-sided tests assessed whether annotated regions carried more heritability than expected; p-values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction for seven comparisons (α = 0.0071) and by the Benjamini–Hochberg false-discovery rate. To validate the parametric tests we also compared the distribution of association χ² statistics inside and outside each annotation with Mann–Whitney U tests.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study

Genetically predicted gene expression was evaluated with S-PrediXcan [

12]. We began with the European subset of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Wave 3 schizophrenia (SCZ) summary statistics (effective sample = 58,749). After excluding non-autosomal variants, 7,659,767 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) remained [

3]. Required columns—rsID, chromosome, position, reference and alternate alleles, p value, beta, standard error, sample size, allele frequency and imputation quality—were confirmed or derived; Z scores were calculated as beta divided by its standard error.

Expression-prediction weights and covariance matrices were taken from GTEx v8 mashr eQTL models for six brain regions: frontal cortex (BA9), hippocampus, amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), nucleus accumbens and caudate [

13]. S-PrediXcan calculates a gene-level Z score by summing SNP Z scores weighted by prediction coefficients and scaling by the variance of the weighted SNP set.

Analyses centred on the same seven predefined gene sets. For every tissue, nominal significance was defined as p < 0.05 and false-discovery significance as q < 0.05. Gene-set enrichment was tested with a Mann-Whitney U comparison of absolute Z scores for genes inside versus outside each set.

Repeating the Same Pipeline on a IQ GWAS

The entire analytical pipeline, including MAGMA gene-set testing, LDSC partitioned heritability estimation, and S-PrediXcan TWAS, was reproduced utilizing summary statistics from a large-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) GWAS meta-analysis [

8]; N = 269,867. This enabled a direct comparison of enrichment patterns between SCZ and IQ, utilizing identical gene sets and preprocessing steps for both datasets. The results of the IQ GWAS analytical pipeline were also previously reported in another study by the author [

14].

Results

MAGMA Analysis

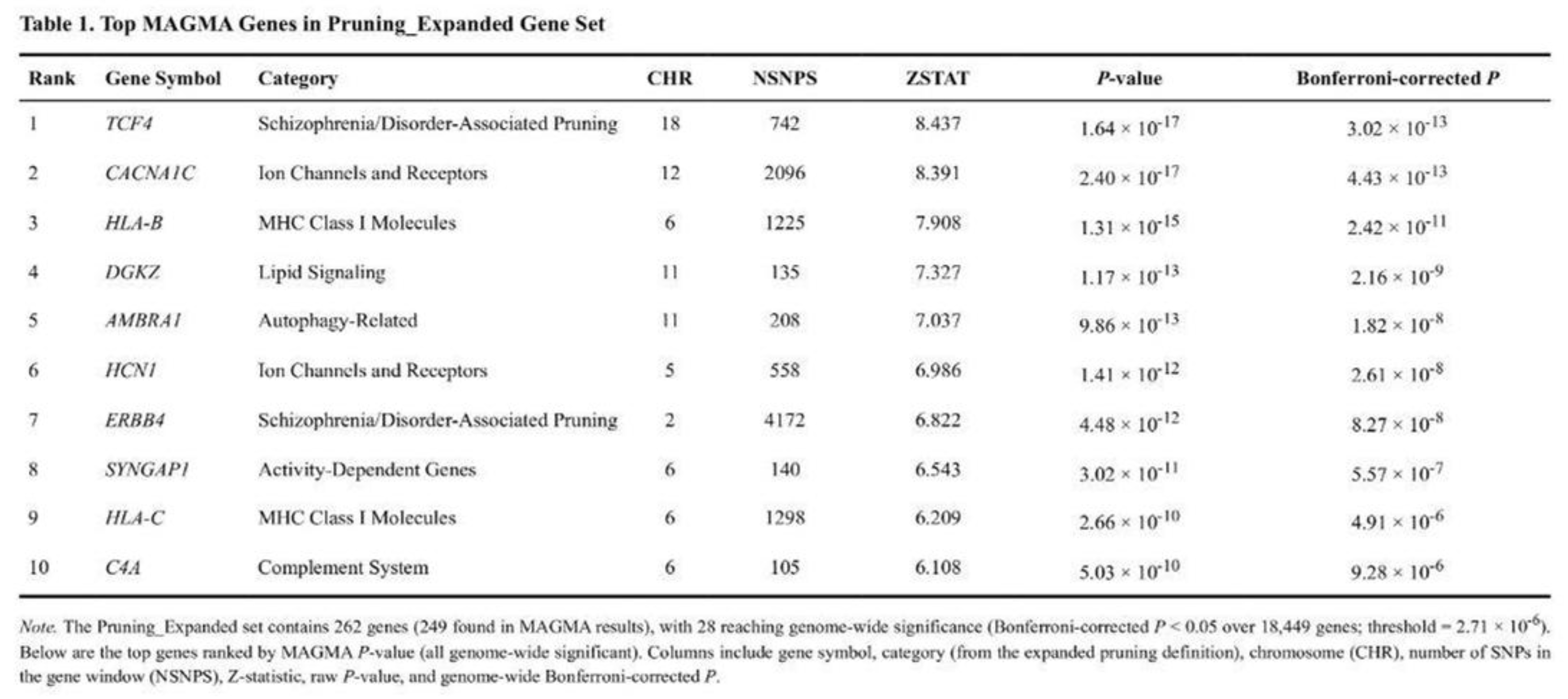

Among 18,449 genes, 705 passed the genome-wide threshold, 2,012 were suggestive and 6,059 were nominal. The most significant locus was DPYD on chromosome 1 (p = 6.4 × 10-24; Bonferroni-adjusted p = 1.2 × 10-19). Several major histocompatibility complex genes (Table 1) also reached genome-wide significance.

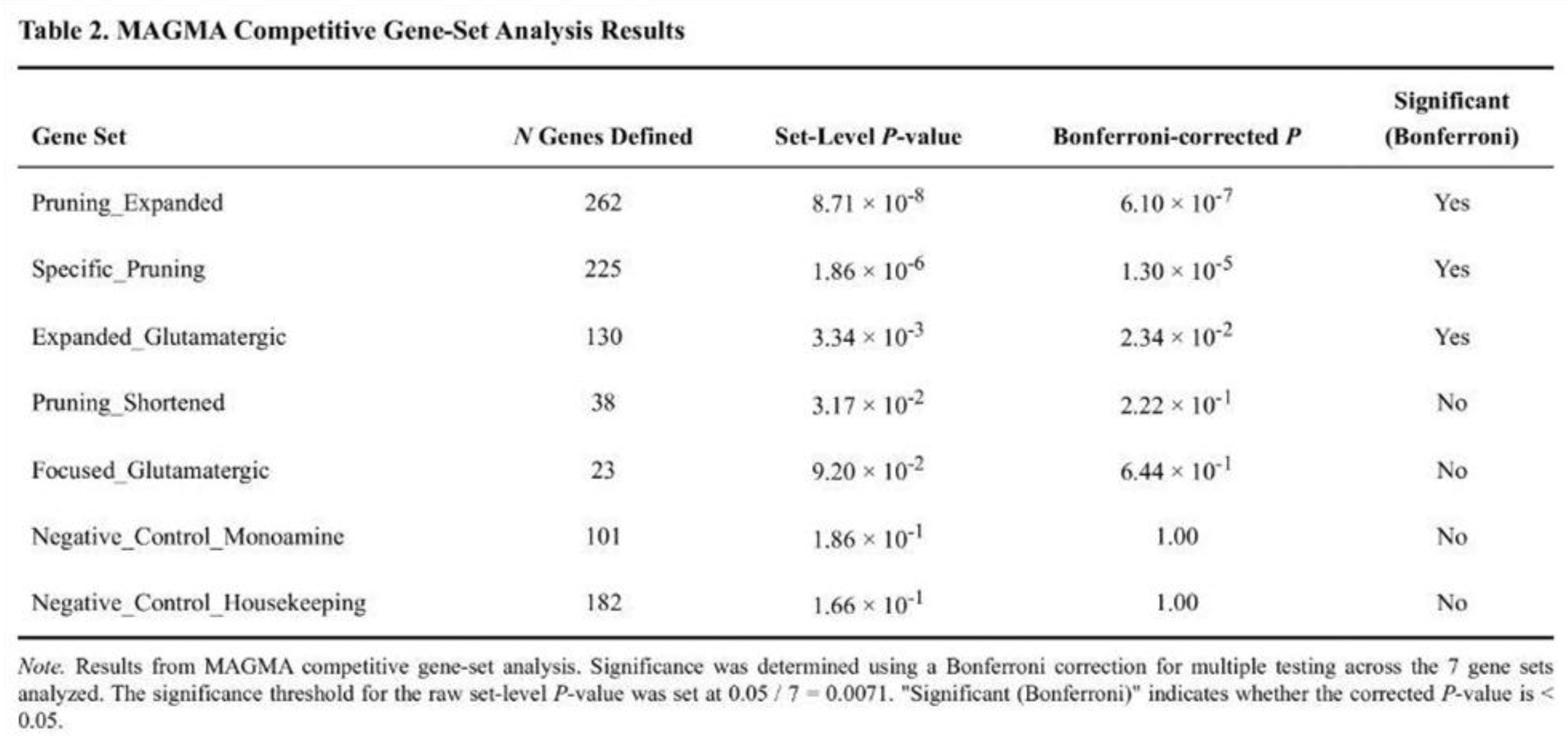

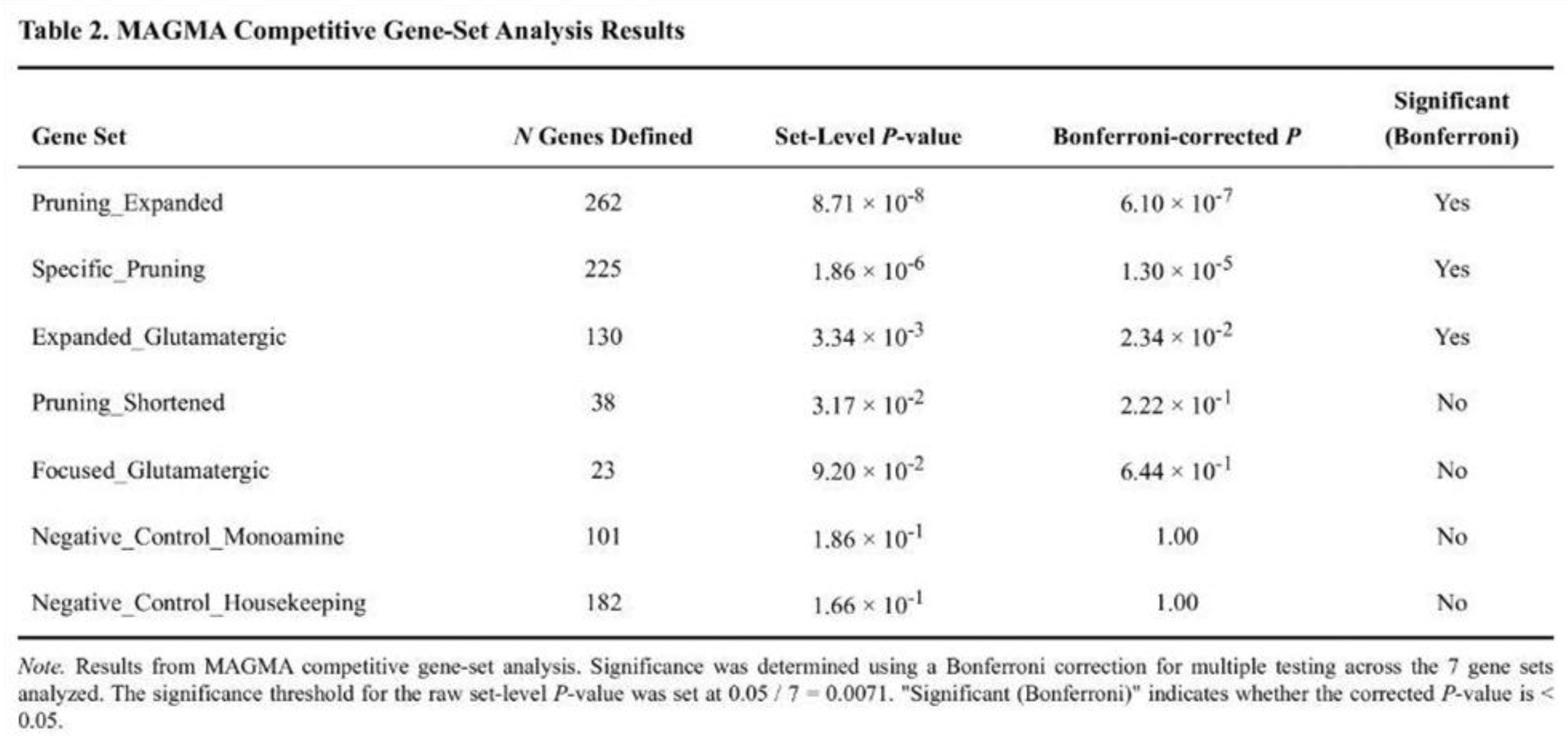

After correction for seven tests, three lists showed enrichment (Table 2). The expanded pruning set produced the strongest signal (t = 5.38, raw p = 8.7 × 10-8; Bonferroni p = 6.1 × 10-7; FDR q = 6.1 × 10-7). The pruning-specific list was also significant (t = 4.75, raw p = 1.9 × 10-6; Bonferroni p = 1.3 × 10-5). The expanded glutamatergic list cleared the FDR threshold (t = 2.76, raw p = 3.3 × 10-3; Bonferroni p = 2.3 × 10-2). The shortened pruning list reached only nominal significance (p = 0.032). Monoamine and housekeeping controls were not enriched (p > 0.16).

Pairwise Mann–Whitney tests confirmed higher Z-score distributions in target sets than in controls; for example, the expanded pruning list versus housekeeping genes yielded U = 22,849 (p = 0.003). Within the shortened pruning list, MHC class I genes drove the signal (mean Z = 4.22; three of five genes nominal). In the expanded pruning list, transcription-factor genes (mean Z = 2.36; five of 10 nominal) and cell-adhesion genes (mean Z = 2.10; five of nine nominal) were prominent.

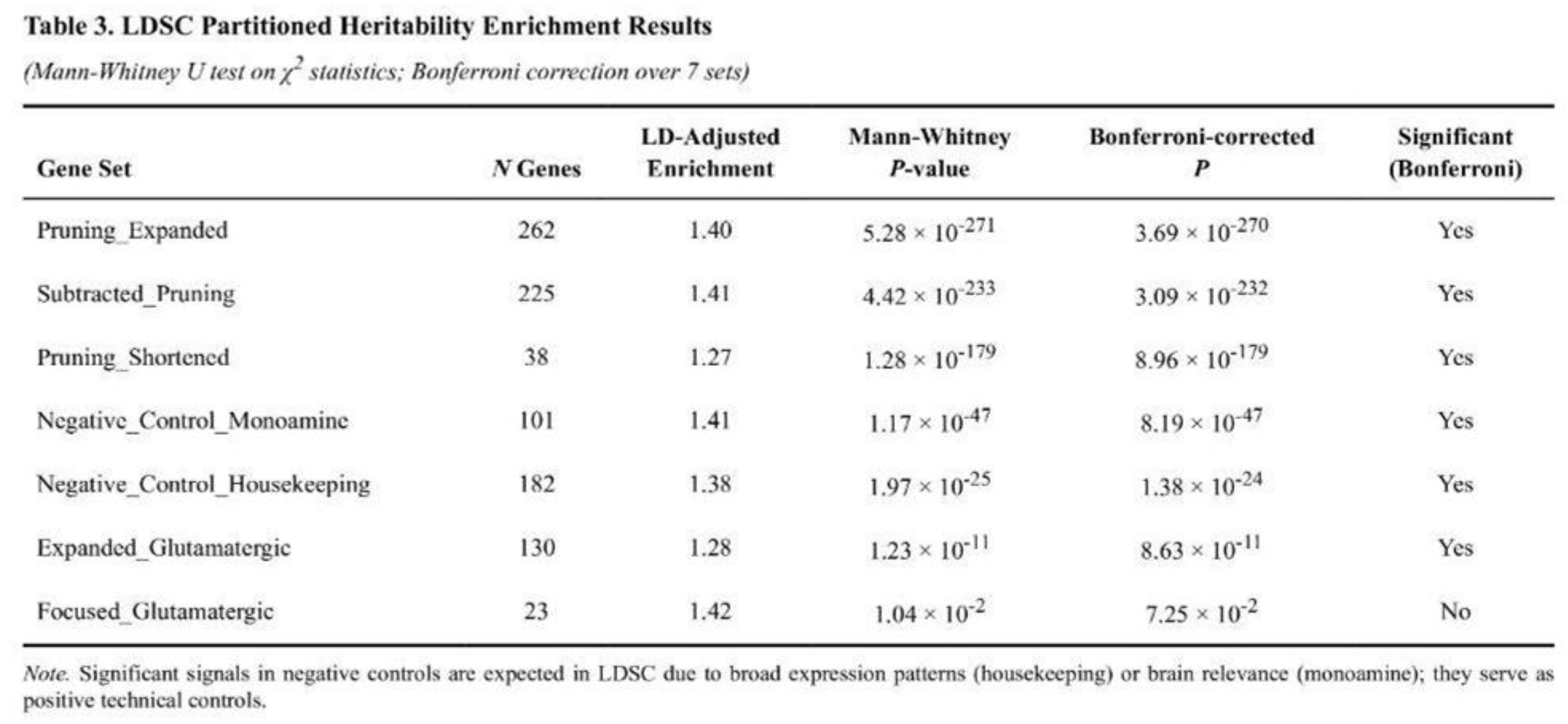

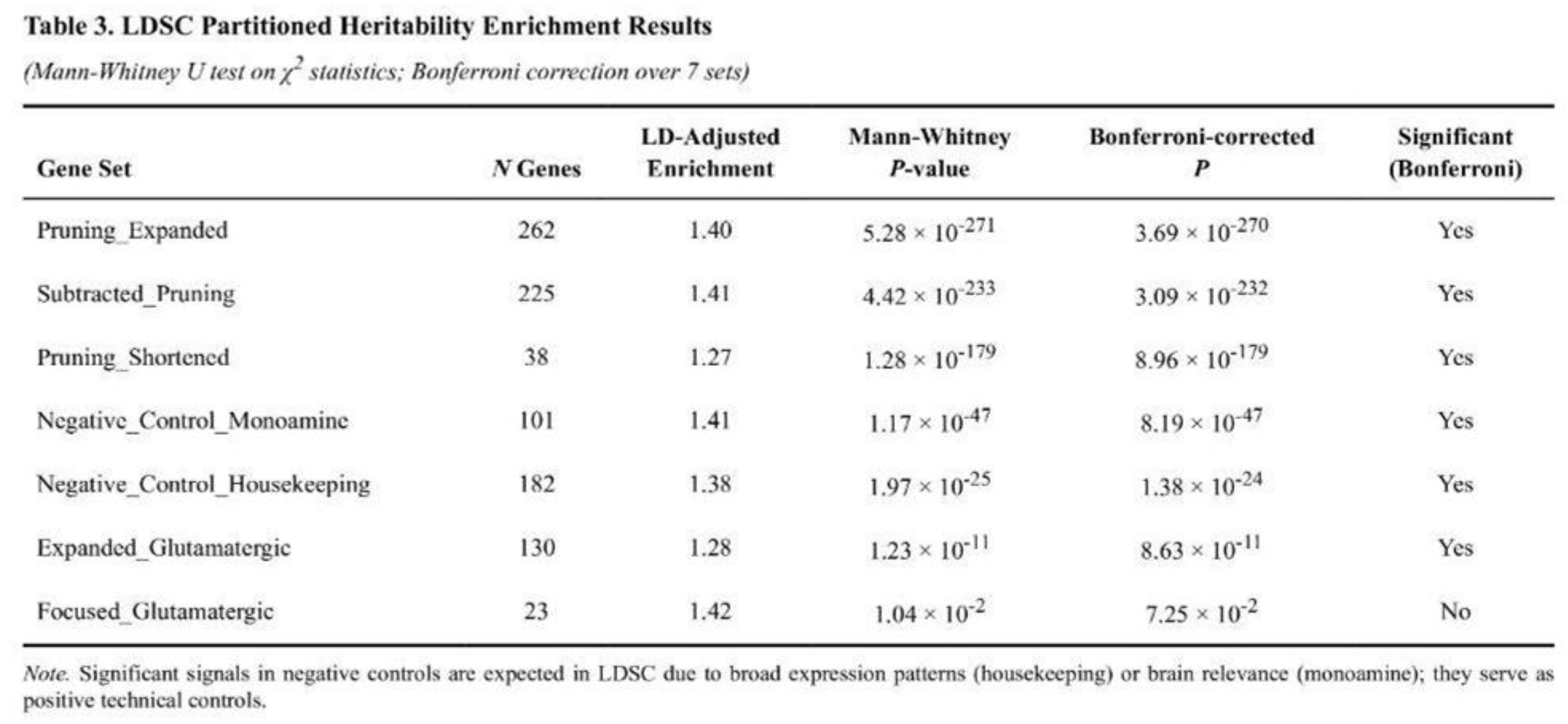

Partitioned Heritability

SNPs overlapping the three pruning-related lists accounted for markedly more schizophrenia heritability than expected from their genomic footprint (Table 3). The shortened pruning list, which labels just 0.17 % of common SNPs, explained 1.85-fold the expected heritability (LD-adjusted enrichment = 1.27; one-tailed p = 5.2 × 10⁻⁸; Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.0071). The pruning-specific set (1.25 % of SNPs) and the expanded pruning set (1.48 % of SNPs) also showed significant enrichment after correction (LD-adjusted enrichments = 1.41 and 1.40; p = 1.4 × 10⁻⁴ and 1.1 × 10⁻⁴, respectively).

Glutamatergic regions displayed smaller effects. The expanded glutamatergic list covered 0.73 % of SNPs and yielded a raw enrichment of 1.05 (LD-adjusted 1.28), producing only nominal significance that did not survive Bonferroni correction. The original 23-gene CGR panel behaved similarly. Among controls, housekeeping genes showed a modest but significant signal (LD-adjusted enrichment = 1.38), whereas monoamine genes were not enriched after multiple-testing correction despite nominal significance. Mann–Whitney analyses paralleled the regression results; pruning annotations had substantially higher median χ² values than their complements (U test p < 10⁻¹⁷⁹ for the shortened list).

Overall, loci related to microglia-mediated synaptic pruning captured the strongest and most consistent share of common-variant risk for schizophrenia, even after removing genes that overlap glutamatergic pathways, whereas glutamatergic and monoaminergic lists showed weaker or control-level signals.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study

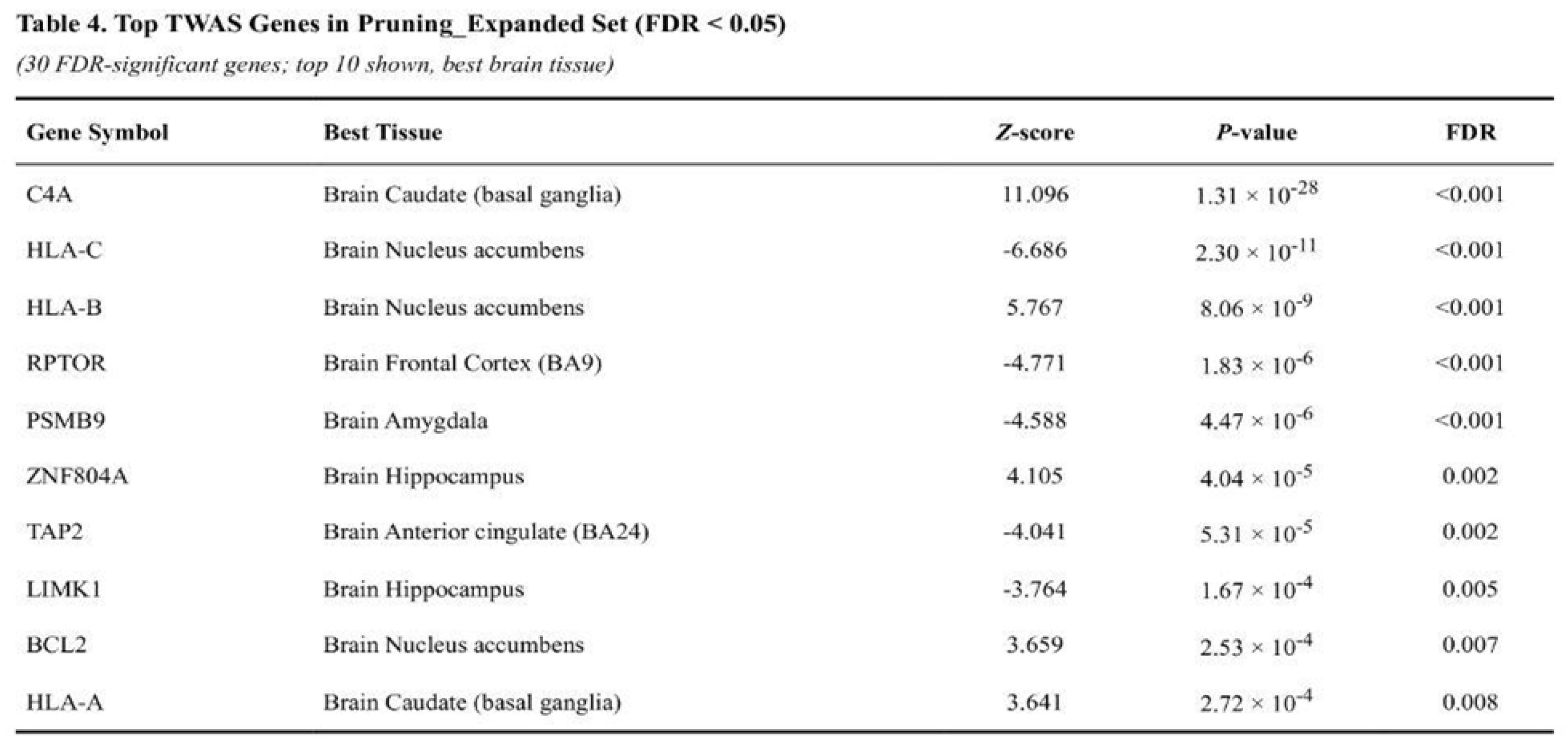

Across the six brain tissues, S-PrediXcan yielded 12,693 nominal gene–tissue associations (4,828 unique genes) and 4,954 q-significant associations (1,887 genes).

The subtracted pruning set produced the strongest enrichment: mean |Z| was 1.12-fold higher than for other genes (Mann-Whitney p = 8.0 × 10⁻⁵). Within this set, 26 of 187 genes met the q < 0.05 threshold; notable findings included C4A (Z = 11.10, p = 1.3 × 10⁻²⁸) and HLA-C (Z = –6.69, p = 2.3 × 10⁻¹¹). Table 4 shows the Top Genes in the expanded pruning set.

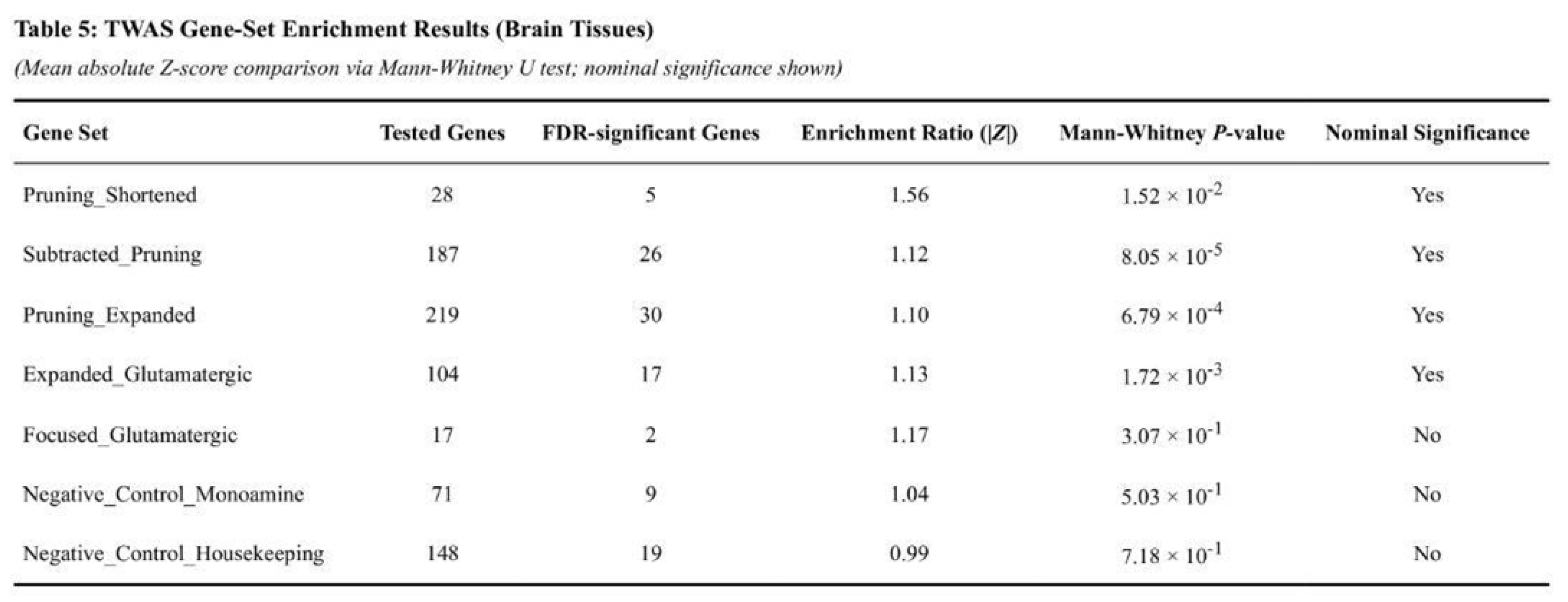

Expanded pruning genes also showed clear enrichment (1.10-fold, p = 6.8 × 10⁻⁴) with 30 of 219 genes q-significant (Table 5). The expanded glutamatergic list had a modest but significant signal (1.13-fold, p = 1.7 × 10⁻³; 17 of 104 genes q-significant). Shortened pruning genes were nominally enriched (1.56-fold, p = 0.015; five of 28 genes q-significant). The focused glutamatergic targets were not enriched (1.17-fold, p = 0.307; two of 17 genes q-significant).

Negative-control groups behaved as expected: the monoaminergic set showed minimal enrichment (1.04-fold, p = 0.503) and the house-keeping set was neutral (0.99-fold, p = 0.718). On average, test sets displayed 1.22-fold enrichment, whereas controls averaged 1.01-fold, underscoring the specificity of pruning-related genes in SCZ risk.

Head-to-Head Comparison of SCZ and IQ GWAS Re-Analyses

Applying the same pipeline to the intelligence meta-analysis by Savage et al. [

8] allowed a direct contrast with our schizophrenia (SCZ) findings. The side-by-side evaluation across MAGMA gene-set tests, LD score–based partitioned heritability, and transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) showed clear differences in how each trait maps onto pruning and glutamatergic biology.

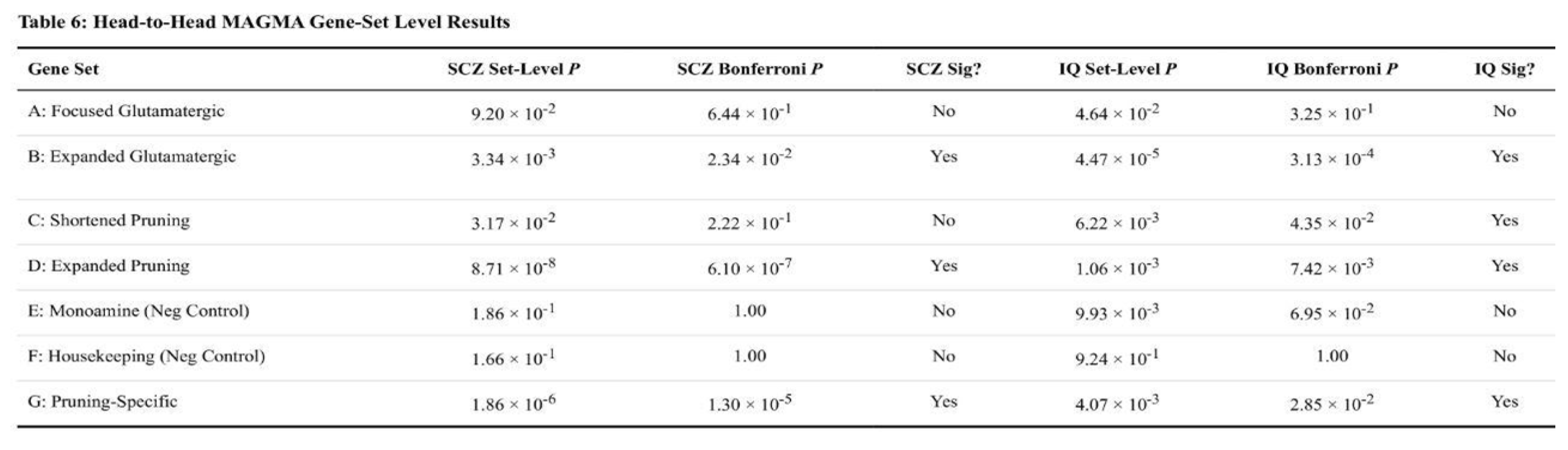

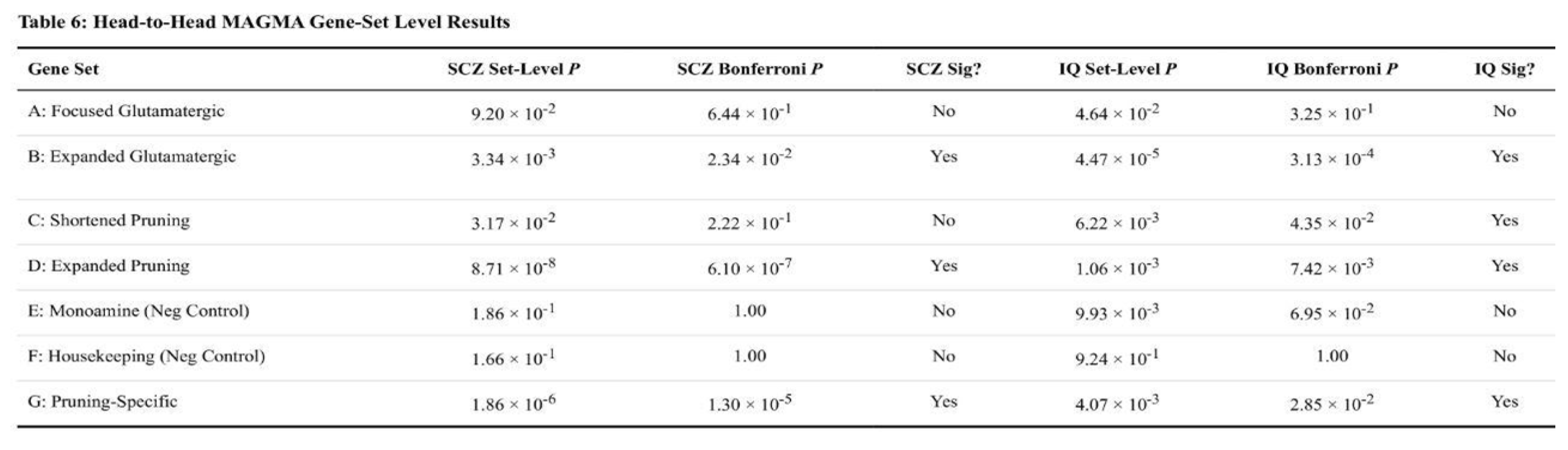

In MAGMA, both disorders displayed significant signals for genes involved in synaptic pruning and glutamate function, yet the effect sizes diverged (Table 6). Expanded pruning genes were markedly enriched for SCZ (Bonferroni-corrected p = 6.1 × 10⁻⁷) but only modestly so for IQ (p = 7.4 × 10⁻³). The pattern reversed for glutamatergic genes: enrichment was stronger for IQ (p = 3.1 × 10⁻⁴) than for SCZ (p = 2.3 × 10⁻²). Pruning-specific tests that removed glutamatergic overlap remained significant for both traits, with a larger signal in SCZ (p = 1.3 × 10⁻⁵ versus IQ p = 2.9 × 10⁻²). Control sets behaved as expected; housekeeping genes were null in both disorders, whereas a nominal monoaminergic signal appeared only for IQ.

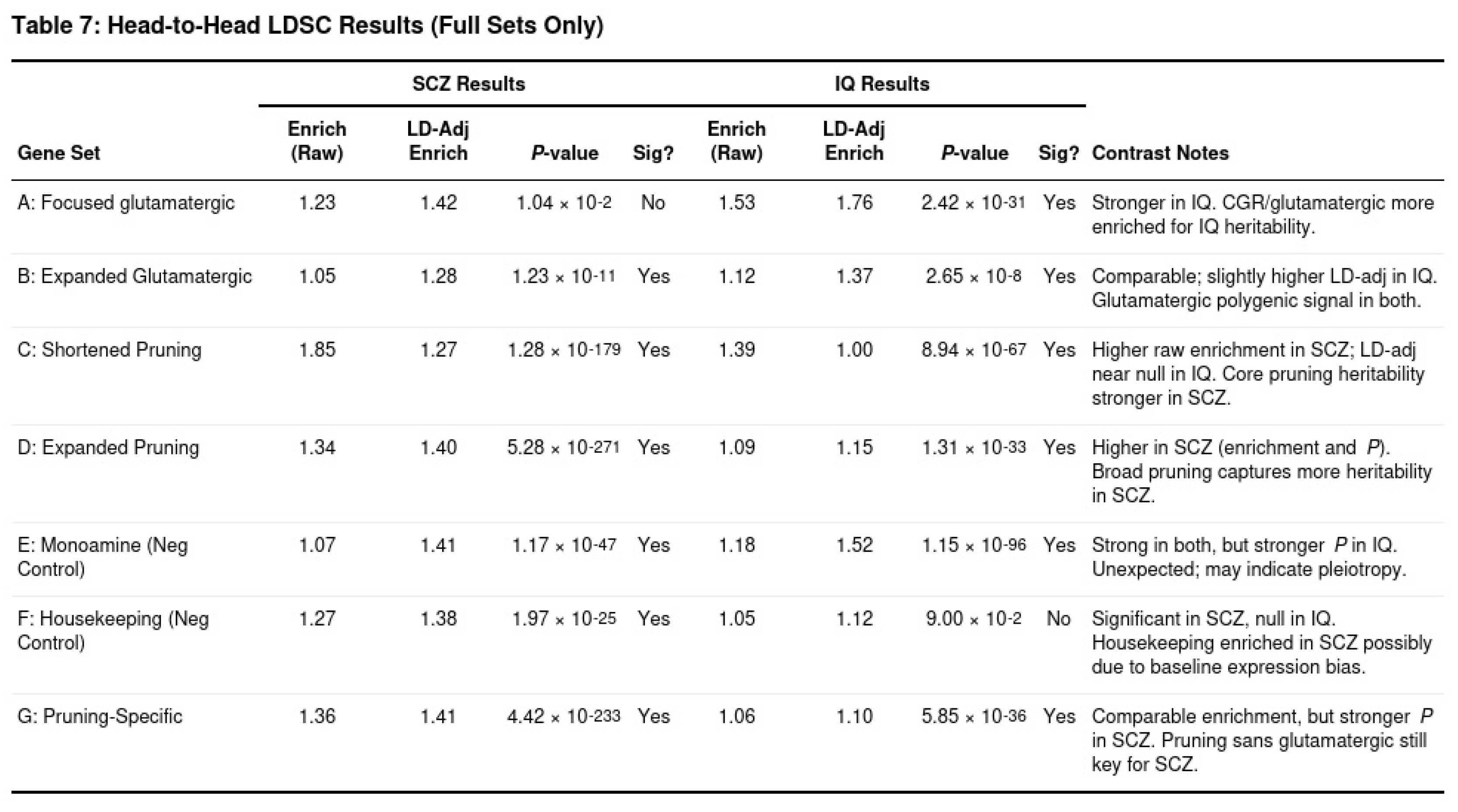

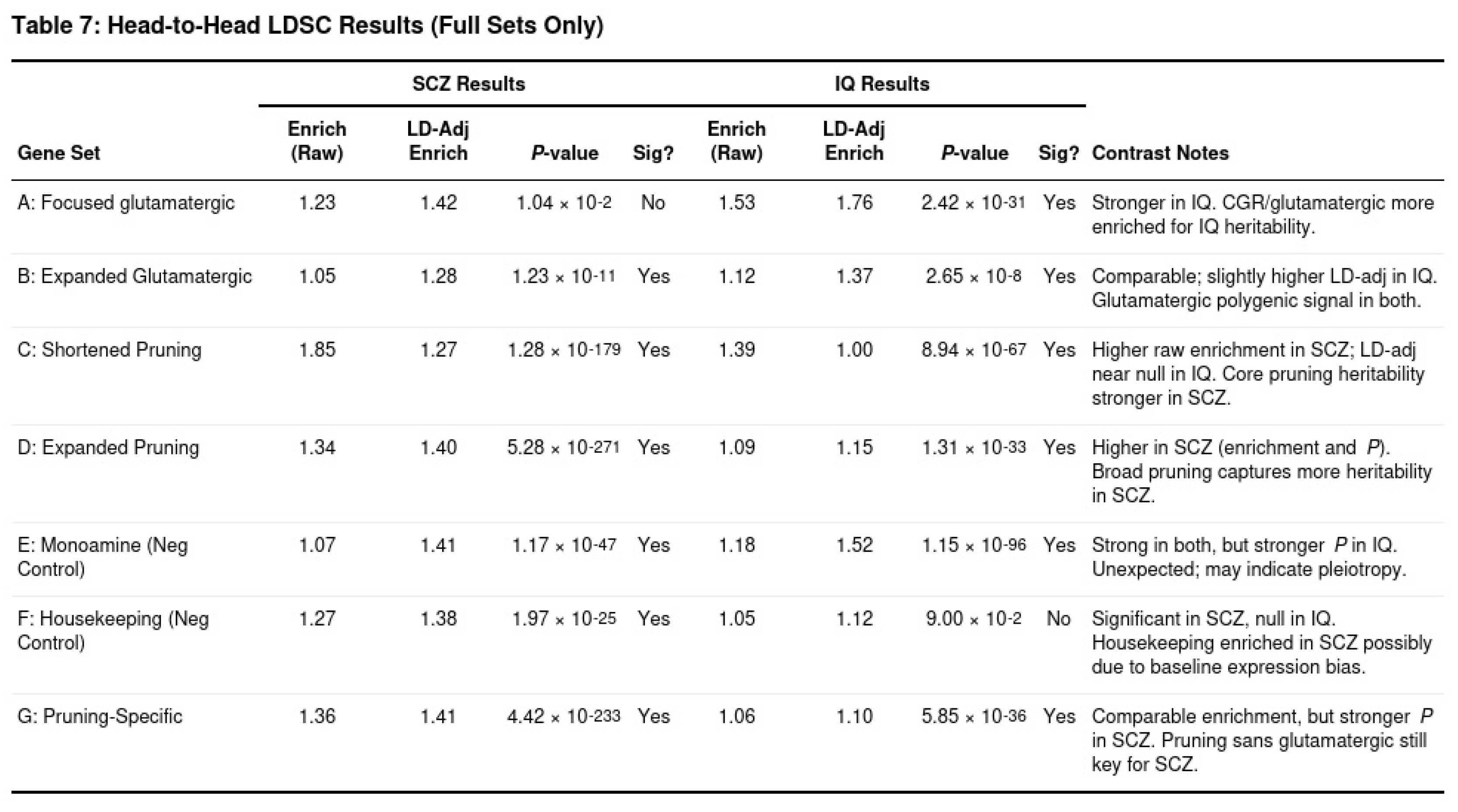

Partitioned heritability results corroborated these trends (Table 7). Pruning annotations captured a substantial share of SCZ SNP heritability (shortened pruning Mann-Whitney p ≈ 10⁻¹⁷⁹, LD-adjusted enrichment ≈ 1.27), far exceeding the corresponding enrichment for IQ (p ≈ 10⁻⁶⁷, enrichment ≈ 1.00). Glutamatergic regions contributed similarly to both traits, although the LD-adjusted estimate was slightly higher for IQ (1.37) than for SCZ (1.28). As often reported with LD score regression, broadly expressed gene sets showed some inflation, but housekeeping genes remained null for IQ, indicating minimal bias.

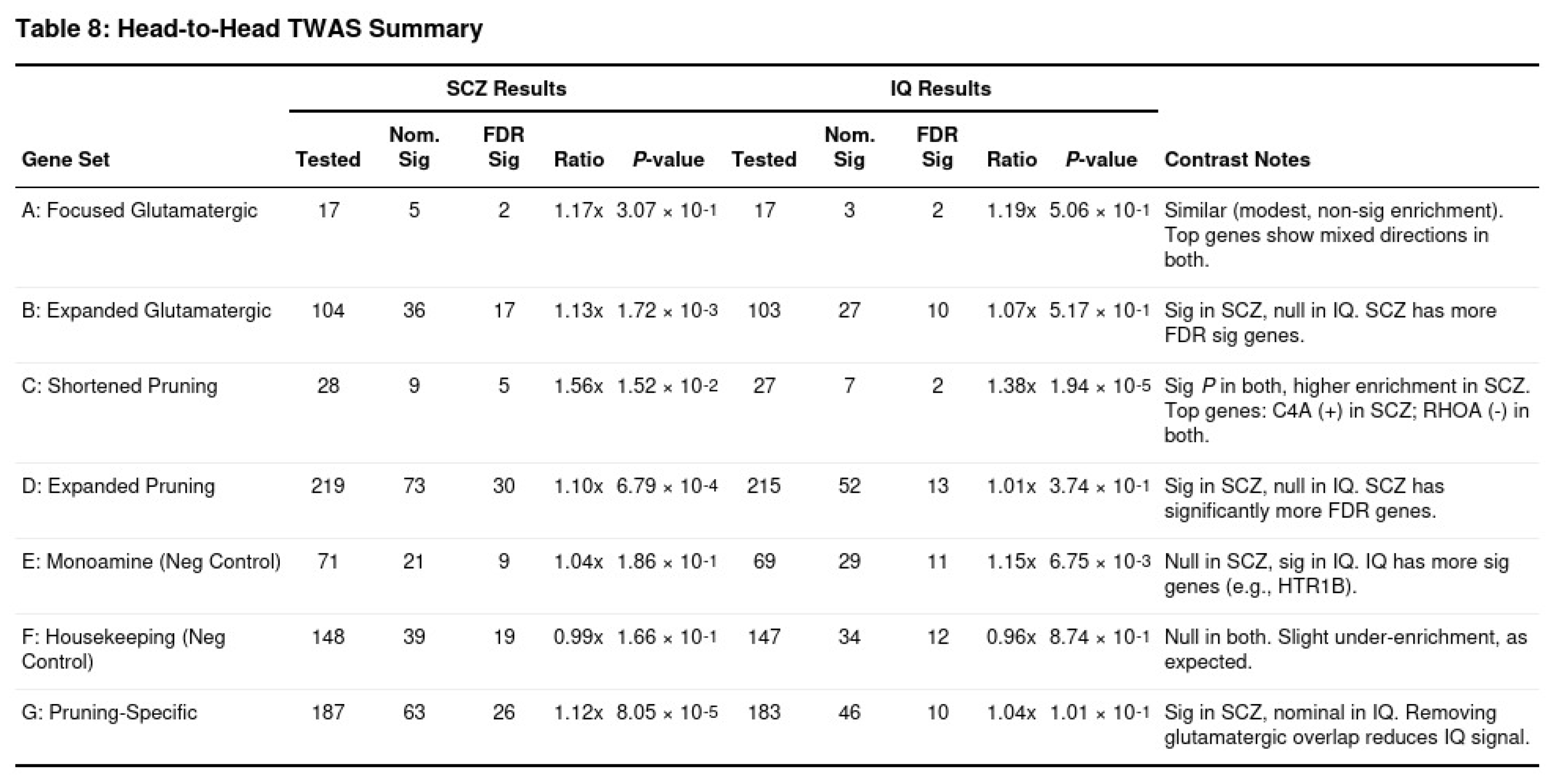

TWAS again highlighted pruning biology in SCZ (Table 8). The shortened pruning set showed a 1.56-fold excess of significant genes in SCZ (p = 1.5 × 10⁻²) compared with a 1.38-fold excess in IQ (p = 1.9 × 10⁻⁵). Glutamatergic enrichment reached significance in SCZ (1.13-fold, p = 1.7 × 10⁻³) yet was absent in IQ. Directionality also differed: pruning genes such as C4A tended to be up-regulated in SCZ, whereas IQ signals leaned toward overall positive effects across plasticity-related genes.

Taken together, all three analytic layers indicate that synaptic pruning genes account for a disproportionate share of SCZ genetic architecture, whereas glutamatergic/plasticity genes show greater relevance for variation in intelligence. The opposing strengths of these pathways underscore pruning excess as a distinguishing feature of SCZ and suggest that efficient glutamatergic signaling may underpin higher cognitive performance.

Discussion

The "Prune-Without-Repair" Model for Schizophrenia

Our convergent findings place pruning biology at the center of schizophrenia risk. Gene-set enrichment using three independent tools repeatedly singled out pruning pathways, whereas analogous tests in an intelligence genome-wide association study (GWAS) gave far weaker signals. This contrast suggests that, in schizophrenia, common variation skews developmental circuit remodeling more than it disrupts general cognitive processes.

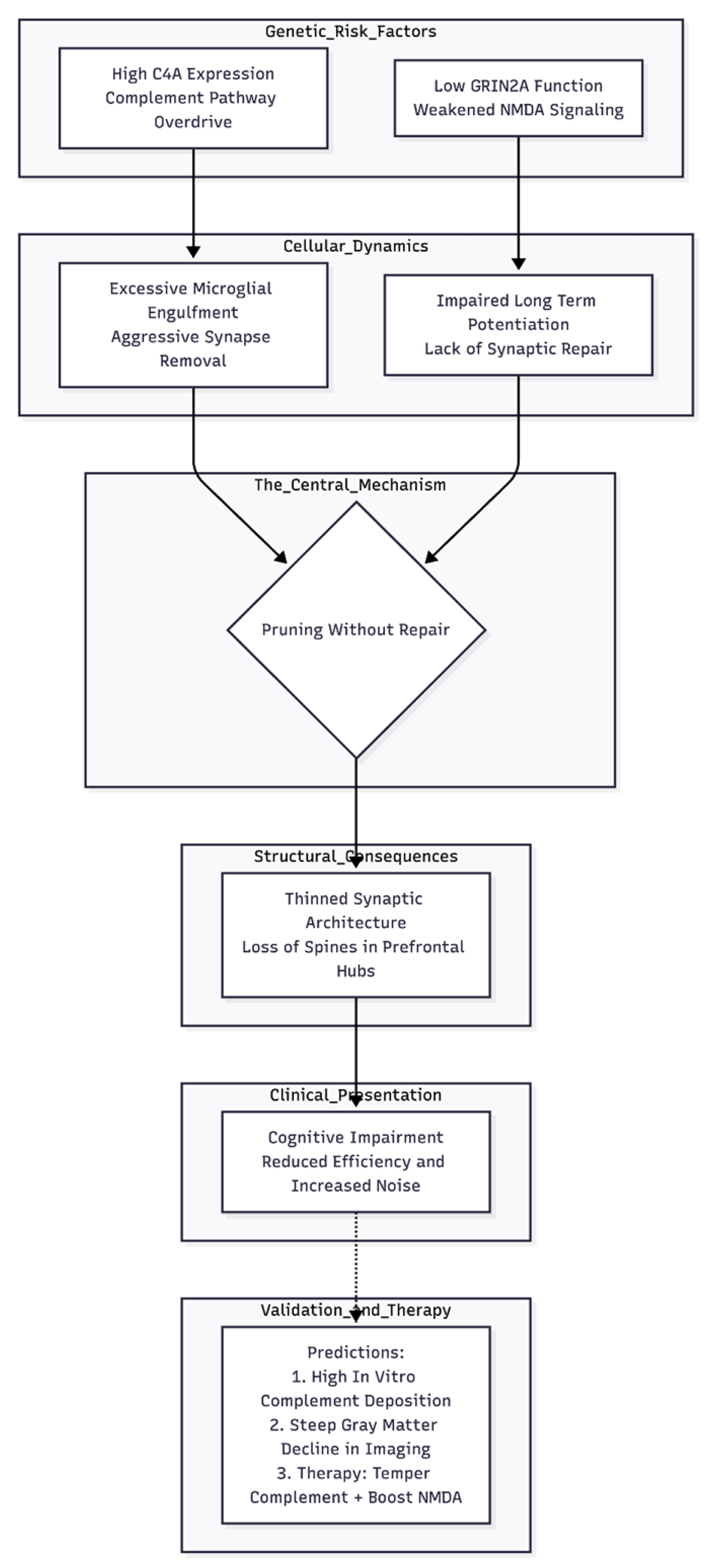

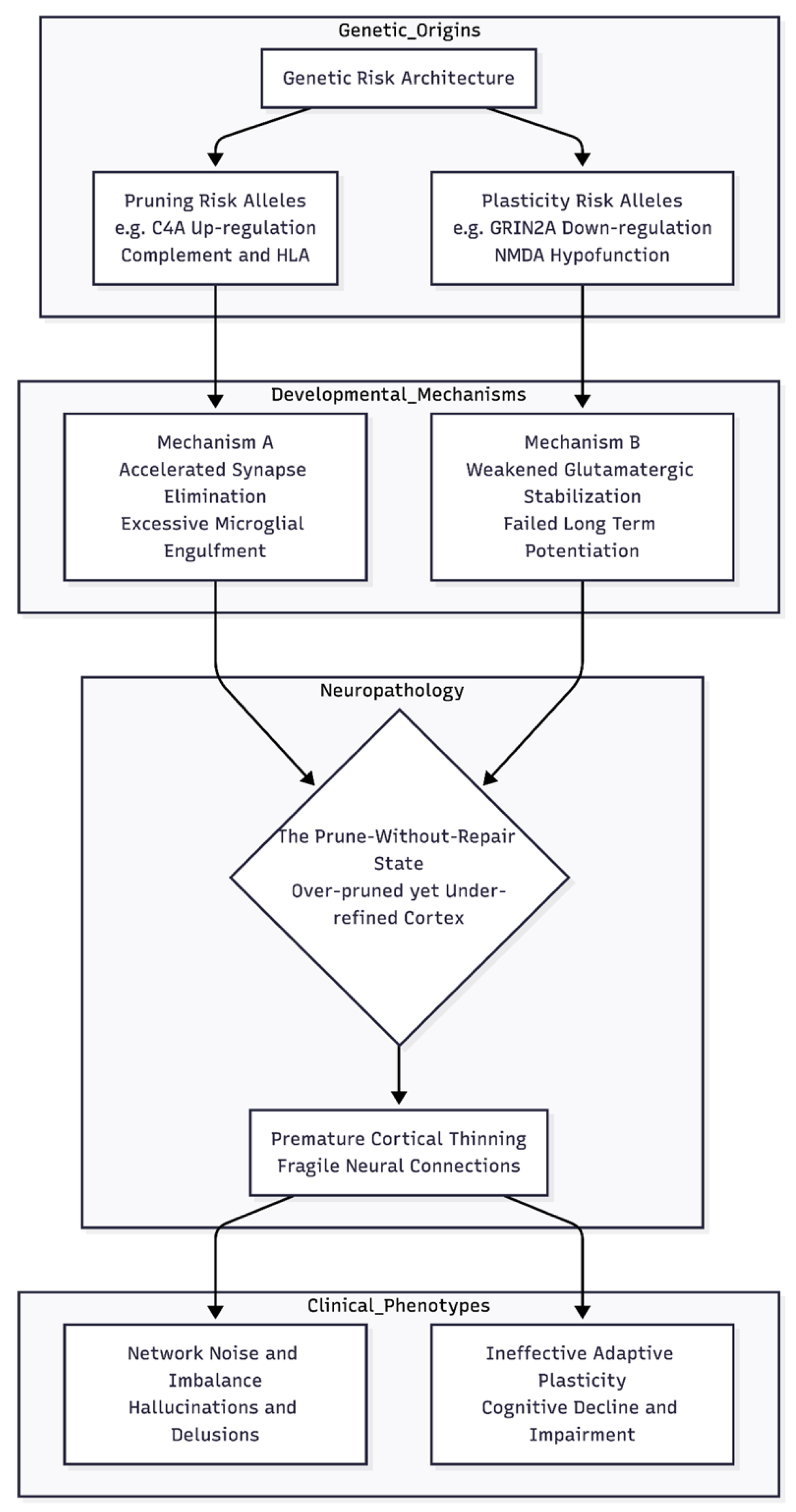

A closer look at the individual analyses clarifies how the risk architecture may operate (

Figure 1). In the MAGMA workflow, expanded pruning genes reached the strongest association (p = 8.7 × 10⁻⁸), surpassing even well-studied glutamatergic sets. Linkage-disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) reinforced this pattern, revealing striking partitioned heritability for shortened pruning annotations (p = 1.3 × 10⁻¹⁷⁹). Transcriptome-wide association (TWAS) then pinpointed specific culprits: C4A showed a large positive Z-score, supporting earlier work that links its up-regulation to illness risk [

4]. By contrast, key glutamatergic genes such as GRIN2A carried nominally negative Z-scores, hinting at reduced synaptic plasticity.

Directionality therefore matters. Risk alleles that enhance pruning machinery—particularly complement and HLA components—could accelerate synapse elimination during adolescence. Simultaneously, alleles that weaken glutamatergic stabilization may leave the remaining connections fragile. The outcome is a cortex that has been "over-pruned" yet under-refined, a scenario consistent with longitudinal imaging that records premature cortical thinning in patients and with post-mortem evidence of excessive microglial engulfment [

5].

This combined "prune-without-repair" model also fits with functional data. Too much complement activity can throw off the balance between excitatory and inhibitory signals, which can cause network noise that shows up in the clinic as hallucinations or delusions [

7]. In the meantime, NMDA or mGlu pathways that don’t work as well may make adaptive plasticity less effective, which could lead to cognitive decline [

6]. Our observation that pruning enrichment persists even after removing glutamatergic overlaps underscores that these pathways interact yet retain independent effects.

The model generates clear predictions. Longitudinal neuroimaging should detect early, region-specific synapse loss in carriers of high C4A copy number, particularly if combined with polygenic scores indexing glutamatergic hypofunction. In vivo or organoid systems that co-express C4A overdrive with NMDA antagonism could reveal additive—or even synergistic—disruptions in circuit maturation. Therapeutically, strategies that temper complement activity while boosting synaptic plasticity may offer a rational route to modify disease course rather than merely suppress symptoms.

Comparative Insights from SCZ and IQ Re-Analyses

Placing the schizophrenia (SCZ) and intelligence quotient (IQ) genome-wide data sets side by side revealed both overlap and sharp contrasts in the biology of synapse remodeling. With three complementary tools—MAGMA, linkage-disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) and transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS)—genes that guide microglial or complement-driven pruning were enriched in both traits, yet the signal was far stronger in SCZ. For example, the shortened-pruning annotation captured an LDSC enrichment with a p value near 10⁻¹⁷⁹ in SCZ but only 10⁻⁶⁷ in IQ, and heritability was concentrated at 1.41-fold versus 1.10-fold, respectively. These gaps suggest that pruning dysregulation is not merely present but central to SCZ, echoing evidence that elevated C4A activity accelerates synaptic loss in disease-sensitive circuits [

4].

Glutamatergic plasticity genes told a different story. They were more prominent in IQ, where the expanded glutamatergic set reached a Bonferroni-corrected p = 3.1 × 10⁻⁴, compared with 2.3 × 10⁻² in SCZ. Efficient NMDA-dependent remodeling therefore appears to favor cognitive performance, whereas in SCZ these same pathways are relatively muted. TWAS directions reinforced this view: SCZ showed positive Z-scores for pruning genes such as C4A—consistent with excess complement activity—and negative scores for plasticity genes such as GRIN2A—consistent with NMDA hypofunction [

6]. IQ, by contrast, tended toward positive associations for guidance molecules like SEMA3F, suggesting that well-regulated pruning coupled with robust plasticity supports higher cognitive ability.

The enrichment profile of control sets also diverged. Monoaminergic genes were modestly enriched in IQ but not in SCZ, perhaps reflecting dopaminergic or serotonergic contributions to motivation and learning that are less relevant to psychotic pathology. Together, the results paint SCZ as a disorder in which pruning overshoots while repair mechanisms lag, whereas IQ reflects a balanced enhancement of both processes.

Our work is correlational, relying on statistical integration of GWAS with gene-expression reference panels [

16]. Causal confirmation will require experimental designs that combine eQTL-based perturbations with longitudinal imaging or cellular models. Even so, the contrast between "prune-without-repair" in SCZ and "prune-and-refine" in IQ offers a plausible mechanistic framework for why closely related pathways can lead either to cognitive gain or to vulnerability to psychosis.

Etiological Hypothesis for Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia

Our side-by-side look at the enrichment data suggests a simple but testable story about why cognition so often falters in schizophrenia. In the illness, gene sets tied to synapse removal were the most over-represented, whereas those linked to glutamatergic plasticity were either weaker or pointed in the opposite direction. In concrete terms, we saw strong positive TWAS Z-scores for C4A—an index of complement-driven microglial pruning—together with modest negative signals for genes such as GRIN2A that support long-term potentiation. The intelligence (IQ) dataset showed the reverse pattern: limited pruning enrichment and directions consistent with efficient, adaptive remodeling.

Placed against earlier laboratory observations, these findings fit a model in which common risk variants nudge microglia toward excess engulfment just as cortical circuits are maturing. Post-mortem and iPSC data already show fewer spines and greater microglial uptake in schizophrenia tissue [

5] and link higher C4A expression to illness risk [

4]. If the complement pathway is overactive while NMDA-dependent strengthening is underactive, the result would be "pruning without repair." Such a combination would thin the synaptic architecture of working-memory and executive networks, increasing neural noise and reducing cognitive efficiency—precisely the deficits that characterize patients [

7].

The hypothesis makes several predictions. First, neurons from high-risk carriers should show higher rates of complement deposition and pruning in vitro, especially when NMDA signaling is dampened. Second, longitudinal imaging of adolescents carrying risk alleles should reveal steeper declines in gray-matter thickness or connectivity within prefrontal hubs. Finally, interventions that temper complement activity or boost glutamatergic plasticity ought to slow cognitive decline. Recent work with minocycline and other complement modifiers provides an early proof of concept, but combination approaches that pair such agents with NMDA modulators may be needed to preserve cognitive reserve through the vulnerable adolescent window.

Novelty and Potential Impact of the Etiological Hypotheses

The present work puts forward two related ideas—one that speaks to schizophrenia (SCZ) in general and another that zeroes in on the illness’s cognitive problems. Both start from well-known notions about faulty synapses, but they join older theories in a new way. The broad SCZ hypothesis suggests that too much synaptic pruning happens while repair and plasticity lag behind, a "prune-and-no-repair" scenario. This view echoes the early pruning model of Feinberg [

15] and aligns with glutamatergic accounts of the disorder [

6]. What is new is the way we blend large-scale genetic findings with transcript-based evidence—showing, for example, that higher C4A expression may drive complement-mediated synapse loss [

4]. By contrasting SCZ with IQ genetics, we highlight that pruning dominates in SCZ whereas plasticity genes weigh more in intellectual ability, sharpening the focus on disease-specific pathways. This comparative angle broadens existing multi-hit frameworks [

5] and points to combined animal tests, such as models that over-express C4A while blocking NMDA receptors.

The cognition-focused hypothesis goes a step further. It links over-pruning and weak plasticity to reduced connections in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus—regions that matter most for everyday functioning [

2]. Researchers have talked about synaptic loss in these areas before [

17], but linking it directly to positive genetic signals for pruning genes and negative signals for plasticity markers like GRIN2A is new. If these ideas are true, they could change the way basic science does experiments that affect both pruning and repair [

18]. Clinically, they hint at dual treatments: complement blockers to curb pruning and NMDA-enhancing drugs to boost cognition—something current antipsychotics rarely improve [

19]. On a public-health level, earlier and cognition-centred care could help many of the roughly 20 million people living with SCZ worldwide [

1].

Figure 2.

The "Pruning Without Repair" Hypothesis for Cognitive Impairment. This flowchart visualizes the proposed etiological pathway where genetic risk factors create a dual failure during adolescent brain development. On one side, high C4A expression drives excessive microglial engulfment; on the other, reduced GRIN2A function prevents the necessary synaptic strengthening (LTP). These forces converge to create a "pruning without repair" state, resulting in physically thinned prefrontal networks and functionally noisy, inefficient cognition. The model concludes with testable predictions for in vitro studies, neuroimaging, and combinatorial therapeutic strategies.

Figure 2.

The "Pruning Without Repair" Hypothesis for Cognitive Impairment. This flowchart visualizes the proposed etiological pathway where genetic risk factors create a dual failure during adolescent brain development. On one side, high C4A expression drives excessive microglial engulfment; on the other, reduced GRIN2A function prevents the necessary synaptic strengthening (LTP). These forces converge to create a "pruning without repair" state, resulting in physically thinned prefrontal networks and functionally noisy, inefficient cognition. The model concludes with testable predictions for in vitro studies, neuroimaging, and combinatorial therapeutic strategies.

Limitations

These proposals also have clear limits. Genetic correlations alone do not prove causation, and transcriptome-wide association studies rely on predicted, not observed, expression, leaving room for hidden biases. Our SCZ-IQ comparison does not account for other disorders that often accompany SCZ; overlapping samples should be tested in future work. The gene sets we used, while carefully chosen, may miss key interactions, and the unexpected IQ link in some "negative-control" pathways hints at pleiotropy or residual confounding.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings spotlight the balance—or imbalance—between pruning and plasticity as a core feature of SCZ. The two hypotheses outlined here refine current disease models and point toward precision therapies. Rigorous functional studies are still needed, but the path they trace could lead to better outcomes for patients.