1. Introduction

Embedded systems are fundamental to modern information technology and the Internet of Things (IoT), with applications ranging from consumer electronics to industrial control systems. Securing these systems is particularly critical in IoT environments, given their rapid expansion and the projection of approximately 30 billion connected devices by 2030 [

1]. Firmware security analysis therefore plays a central role in protecting embedded devices, as vulnerabilities in firmware can compromise device integrity, enable unauthorized access, and propagate attacks across connected networks.

EMBA is an open-source firmware security analysis tool that automates reverse engineering and vulnerability detection of embedded systems, providing actionable insights for cybersecurity professionals. EMBA is developed by Siemens cybersecurity engineers led by Michael Messner [

2]. The tool integrates firmware extraction, emulation-based dynamic analysis, and static analysis, and produces structured reports summarizing identified security issues. EMBA automatically detects vulnerabilities such as insecure binaries, outdated software components, vulnerable scripts, and hard-coded credentials [

3]. One of its notable features is the generation of a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) directly from binary firmware, which supports supply chain security assessments by correlating identified components with known vulnerabilities from exploit databases [

4]. In addition, EMBA employs a comprehensive multi-stage analysis approach to identifying zero-day vulnerabilities by examining both compiled binaries and interpreted scripts written in languages such as PHP, Python, and Lua [

5].

As of December 2024, EMBA included 87 analysis modules, these are categorized into four groups: Pre-Modules (P), Core Modules (S), Live Testing Modules (L), and Finishing Modules (F) [

6,

7]. EMBA version 1.4.1 comprises 58 distinct modules, while version 1.4.2 includes 60 modules, both evaluated using a modified default scan configuration [

7]. The experiments presented in this study were conducted using EMBA versions 1.4.1, 1.4.2, and 1.5.0, which was the latest release available as of December 2024. Under the specified experimental settings, version 1.5.0 executed 68 distinct modules, each designed to perform a specific analytical task. Updated versions of EMBA, including version 1.5.2, are publicly available through the official EMBA repository, enabling users to access ongoing improvements and additional functionality [

8]. EMBA is accessible through both a command-line interface and a graphical interface, EMBArk, which presents analysis results in summarized and module-specific reports [

9].

From a deployment perspective, EMBA can be executed on standalone servers or Cloud platforms such as Microsoft Azure. Standalone deployments offer predictable costs, full control over hardware and software resources, and higher assurance for sensitive data handling, but they require ongoing maintenance and are constrained by fixed computational capacity. In contrast, Cloud platforms provide elastic resource allocation, scalability, and collaborative workflows, while introducing additional considerations related to cost variability, data protection, regulatory compliance (e.g., General Data Protection Regulation and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), and system integration complexity. Despite the widespread use of both deployment models, there is limited empirical evidence comparing their impact on firmware security analysis performance, cost, and analytical consistency.

To address this gap, this study aims to provide a systematic, quantitative comparison of the EMBA firmware security analysis tool deployed on a standalone personal computer and a public Cloud environment (Microsoft Azure). The work evaluates performance across multiple EMBA versions using identical configurations, focusing on scan duration, output consistency, and operational cost. The results demonstrate measurable performance differences between deployment environments while indicating comparable vulnerability detection coverage, and they highlight practical trade-offs between cost predictability, scalability, and operational constraints. These findings offer deployment-oriented insights to support informed decision-making by cybersecurity practitioners conducting large-scale or repeated firmware security analyses.

2. Literature Review

This literature review discusses EMBA's technical aspects and its implementation in different settings. Through the examination of theoretical models as well as empirical research, this review determines gaps in the research and provides a basis for studying EMBA's performance in Cloud and standalone server environments.

2.1. White Box Testing

The growing use of IoT devices throughout various industry sectors has increased the necessity for security controls specific to IoT devices. In today’s world, IoT devices often become important targets for cyberattacks because they store personal and sensitive information and can be connected to other devices and networks [

10].

Performing a vulnerability assessment is very important for discovering and fixing IoT device firmware vulnerabilities. The approaches of vulnerability assessments are generally categorized into three types: black-box, gray-box, and white-box testing. The white box testing approach provides a detailed analysis of the system's underlying components, such as source code, design, and architecture [

11]. The degree of detail provided by that strategy allows testers the best possible understanding of code functionality and identifies vulnerable areas, making it possible to identify hidden flaws that other approaches may not recognize. Verma et al. (2017) argue that white-box testing enables effective examination of program control flows, data usage, and structural soundness, making it much more effective at discovering and remedying potential vulnerabilities [

12].

Designed for white-box testing, the EMBA tool is assessing IoT firmware by analyzing extracted binary files and internal structures. EMBA can help to reveal vulnerabilities that might go undetected while using other testing approaches by presenting a transparent view of the inner structure of the system and code base. This approach closely follows the core principles of white-box testing, giving value to code examination and structural analysis.

2.2. Reverse Engineering and Firmware Analysis

Several studies emphasize reverse engineering as a fundamental technique for analyzing IoT device vulnerabilities, providing in-depth examination of internal firmware and system structures that often remain inaccessible through external methods. Shwartz et al. (2018) demonstrate that conventional black-box testing is insufficient for identifying internal weaknesses such as hardcoded credentials, buffer overflows, and insecure firmware configurations. By disassembling firmware and software components, reverse engineering provides detailed visibility into device behavior and security flaws, including weak password protection and insecure configurations, which can be exploited to compromise devices, as shown in laboratory experiments involving modified vulnerable IoT devices [

13].

Tamilkodi et al. (2024) focuses on the vulnerabilities of IoT devices by analyzing malware specifically designed to exploit these devices [

14]. Their work accepts static and dynamic analysis methods using tools such as IDA Pro, Ghidra, and Wireshark for reverse-engineering malware and identifying vulnerabilities. This work highlights several important vulnerabilities that are commonly targeted by malware, including weak authentication, lack of input validation, and weak firmware protection. Also, the study contributes to advanced malware detection and prevention strategies, i.e., IoT malware-oriented approaches, including heuristic or signature-based methods, through malware behavior analysis. The findings emphasize the importance of stringent security practices and proactive vulnerability management to strengthen the resilience of IoT environments against advanced threats.

Similarly, Votipka et al. (2019) emphasizes the critical role of reverse engineering in IoT security analysis, noting that it enables analysts to understand device design, functionality, and operational mechanisms that are otherwise inaccessible [

15].

With the increasing sophistication of IoT devices, reverse engineering has become a critical approach for understanding internal system operations and identifying previously undiscovered vulnerabilities [

16]. Prior studies emphasize that such techniques provide deep visibility into firmware components that are otherwise inaccessible through external testing methods.

Building upon these principles, tools such as EMBA apply reverse engineering techniques to extract and analyze IoT firmware in an automated manner. EMBA’s binary analysis engine uses multiple reverse engineering frameworks like Radare2 and Ghidra and the well-established Static Application Security Testing (SAST) framework Semgrep fully automatically on the most critical binary files [

17].

However, prior research outlines EMBA’s technical capabilities; it does not evaluate how its performance or accuracy varies across different deployment environments, such as Cloud versus standalone servers. This lack of comparative assessment remains an open gap in current firmware security research.

2.3. Static and Dynamic Analysis

Within the reverse engineering process, one phase under the security assessment framework is both static and dynamic analyses. Static analysis is defined by the inspection of either source code or binary code, regardless of its runtime, thus enabling the detection of vulnerabilities like the misuse of unsafe functions and programming errors that may be exploited. Though this process is preferred due to its efficiency and absence of runtime overhead, it often generates false positives and negatives, which lowers its effectiveness when conducted alone (Aggarwal & Jalote, 2006). Dynamic analysis, on the other hand, involves executing software under controlled environments, like sandboxes, to enable real-time inspection of its behaviors. This process is considered more accurate since it has the capability of detecting faults that occur at runtime alone, such as input handling mistakes or communication with other systems [

18]. However, dynamic analysis requires a thorough set of test cases needed to ensure full coverage, which leads to its own complexities along with the respective runtime overhead.

Static analysis is very important for detecting vulnerabilities in IoT devices, since it does not require code execution. This approach is especially suited for discovering software-related issues, such as poor data handling, outdated components, and password security vulnerabilities. As per Ferrara et al. (2020), six out of seven major vulnerabilities among the OWASP IoT Top 10 can be resolved with static analysis, thus demonstrating its utility in mitigating critical threats in IoT environments [

19]. However, there are limitations, especially with respect to discovering hardware or runtime vulnerabilities, which require other forms of analysis. Despite this, static analysis remains a valuable tool for enhancing security analysis of IoT systems.

Static analysis is prone to false positives and does not have the sophistication required to detect some vulnerabilities that occur during runtime. To overcome these inherent deficiencies, EMBA uses dynamic analysis and static analysis together [

20,

21]. Dynamic analysis observes the behavior of the firmware while it is running to detect vulnerabilities that may go undetected by static analysis. For example, dynamic analysis can show vulnerabilities related to input validation or problems due to interactions with external components. By combining the advantages of static and dynamic analysis, EMBA provides a more accurate and complete assessment of potential security vulnerabilities.

The combined approach adopts the model proposed by Aggarwal and Jalote (2006), which posits that combining static and dynamic analyses efficiently overcomes the basic drawbacks of both methods while increasing their overall effectiveness [

18]. The combined approach reduces the number of test cases required by dynamic analysis while at the same time enhancing the accuracy in identifying vulnerabilities, thus making it especially useful in protecting complex IoT systems.

2.4. Emulation and Code Analysis

Code analysis is a critical component in ensuring the security and reliability of IoT firmware, providing a structured approach to identifying potential vulnerabilities at both the design and implementation levels. Unlike reverse engineering, which focuses on understanding system structure and behavior post-hoc, code analysis emphasizes proactive detection of weaknesses through systematic examination of source code, binaries, and execution traces. This process supports early identification of defects and security flaws, which is essential for reducing the risk of exploitation in complex systems (Goseva-Popstojanova & Perhinschi, 2015) [

22].

EMBA incorporates code analysis techniques to improve the detection of firmware vulnerabilities. Static analysis evaluates code without execution, identifying structural weaknesses such as poor input validation, unsafe function usage, and outdated components. Dynamic analysis, often performed in conjunction with emulation, observes the runtime behavior of firmware to detect execution-dependent flaws, including buffer overflows, race conditions, and logical errors (Zhou et al., 2025) [

23]. By combining these approaches, EMBA provides detection accuracy, coverage, and prioritization of high-risk vulnerabilities.

Recent studies further highlight the broader industrial relevance of comprehensive code analysis. Komolafe et al. (2024) [

24] emphasize that integrating static, dynamic, and system-level analysis is essential not only for uncovering hidden vulnerabilities but also for ensuring compliance with security and privacy standards. This integrated approach supports reliability, accountability, and assurance in software-intensive systems across sectors such as manufacturing, aerospace, and critical infrastructure.

In the context of IoT firmware security, code analysis within EMBA supports the identification and remediation of vulnerabilities, mitigating the likelihood of zero-day exploits and improving overall system resilience.

2.5. The Role of EMBA in Firmware Security Analysis

EMBA tool integrates reverse engineering, static and dynamic analysis, and emulation within a single platform to facilitate firmware vulnerability detection. This structure enables systematic and detailed identification of firmware-level security issues. By facilitating the early detection of potential security breaches, especially in IoT devices characterized by long lifespans and limited post-deployment update options, EMBA reduces the likelihood of long-term security risks. Its automated capabilities further strengthen the assessment of IoT security and support proactive vulnerability mitigation prior to device deployment. Due to this architecture, EMBA enhances vulnerability detection procedures while improving the overall security posture of IoT configurations.

Given EMBA’s established relevance in IoT device security, it is appropriate to examine how the existing literature has engaged with it. The reviewed studies provide detailed information into EMBA’s technical capabilities and limitations, while also emphasizing its applications and potential areas for improvement. This literature offers a comprehensive understanding of how EMBA has been used and evaluated, forming the basis for our study. Although our review of the current literature identified no prior article that specifically examined the use of the EMBA tool comparing the Cloud versus a standalone server, several academic articles and online sources have discussed EMBA's capabilities. The EMBA development team has provided extensive information on EMBA, particularly on its GitHub page (GitHub, 2024) [

25], which is an official resource. This webpage provides information about EMBA’s usage and functionalities.

EMBA has been used in several scientific studies. Müller [

26] presents a comprehensive analysis of security vulnerabilities in IoT devices using the TP-Link router as a case study using EMBA. The author notes EMBA can detect a wide variety of vulnerabilities, including misconfigurations in Secure Shell (SSH) servers and code vulnerabilities in Python and Bash scripts; he also notes EMBA’s limitations. Specifically, he concludes EMBA misses detection of weak ciphers in SSH and certain vulnerabilities in Common Gateway Interface (CGI) scripts and compiled binaries. He also notes that EMBA's extensive output can be overwhelming for developers with limited security expertise.

De Ruck et al. [

27] discussed the development and evaluation of B4IoT, a platform designed to generate customized Linux-based firmware benchmarks for assessing firmware security analysis tools. One of the tools mentioned in the article is EMBA. The authors highlight its limitations in detecting specific vulnerabilities. The version of EMBA tested at the time the article was written in 2023 was found to be ineffective at identifying weak ciphers in SSH services like Dropbear or OpenSSH. This shortcoming illustrates the need for additional specialized tools, such as ssh-audit, to complement EMBA for a thorough security assessment. The benchmark tests conducted using the B4IoT platform revealed these gaps, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive toolset for accurate firmware security analysis.

Ahmad and Andras [

28] delve into the technical aspects of performance and scalability in Cloud-based software services. They provide a detailed analysis of the scalability metrics applied to two Cloud platforms: Amazon EC2 and Microsoft Azure. The study demonstrates how different auto-scaling policies and Cloud environments impact the performance of software services, including vulnerability analysis frameworks. By using technical scalability measurements inspired by elasticity metrics, the authors compare the scalability of Cloud-based software services in different scenarios. This research shows the importance of incorporating performance and scalability testing into the development of a lifecycle of Cloud-based applications to ensure optimal resource utilization and service delivery.

Bouras et al. [

29] provides a detailed look at the differences between Cloud-based and standalone server solutions, highlighting how 5G technology enhances the advantages of Cloud computing. The authors argue that Cloud computing provides on-demand access to resources, which leads to greater flexibility and cost savings, especially for medium-sized enterprises. They use mathematical models to analyze capital and operational costs, concluding that Cloud-based systems can result in significant financial benefits. By combining 5G features like lower latency and increased bandwidth, the paper suggests that organizations can improve their efficiency and save money in sectors such as manufacturing and healthcare. Also, this analysis emphasizes the importance of utilizing advanced technologies like 5G to make Cloud computing solutions more effective, aligning with the discussions about the applications of EMBA in security assessments [

29].

Fisher [

30] provides the critical considerations decision-makers face when choosing between Cloud services and traditional standalone server systems. Fisher emphasizes the need to understand the total cost of ownership (TCO) and reminds the reader that Cloud services may offer flexible pricing, but the total costs can accumulate and potentially surpass those of standalone server solutions over time. The article encourages organizations to conduct thorough needs analyses and due diligence before committing to major Cloud investments. This perspective ties in closely with the discussions about the EMBA tool, as both the use of EMBA and investment in Cloud environments for EMBA execution require careful consideration of effectiveness and limitations regarding cost and security in different environments. Fisher’s insights reinforce the need for a comprehensive approach when evaluating technological solutions, especially as organizations navigate the ever-changing landscape of IT infrastructure. While the above articles mainly discuss EMBA's capabilities and limitations in firmware security analysis, none specifically address our desired focus on comparing EMBA's performance on Cloud versus standalone personal computer or evaluating the differences between its various versions.

This literature review synthesizes existing research on EMBA’s technical capabilities and applications, confirming its importance in IoT firmware vulnerability analysis. Despite its robust combination of reverse engineering, static and dynamic analysis, and emulation, prior work focuses primarily on functionality rather than deployment implications. The absence of studies comparing Cloud-based versus standalone EMBA execution highlights a significant gap. Addressing this, the present review establishes the rationale for evaluating how deployment environments affect EMBA’s operational performance and the accuracy of its vulnerability detection.

3. Materials and Methods

To evaluate the performance of the EMBA firmware security analysis tool across different execution environments, a structured and reproducible methodology was designed. The study compares EMBA’s behavior on locally hosted standalone servers and a Microsoft Azure virtual machine configured to closely mirror the standalone systems. The methodological design focuses on three key dimensions: firmware characteristics, platform configurations, and experimental repeatability.

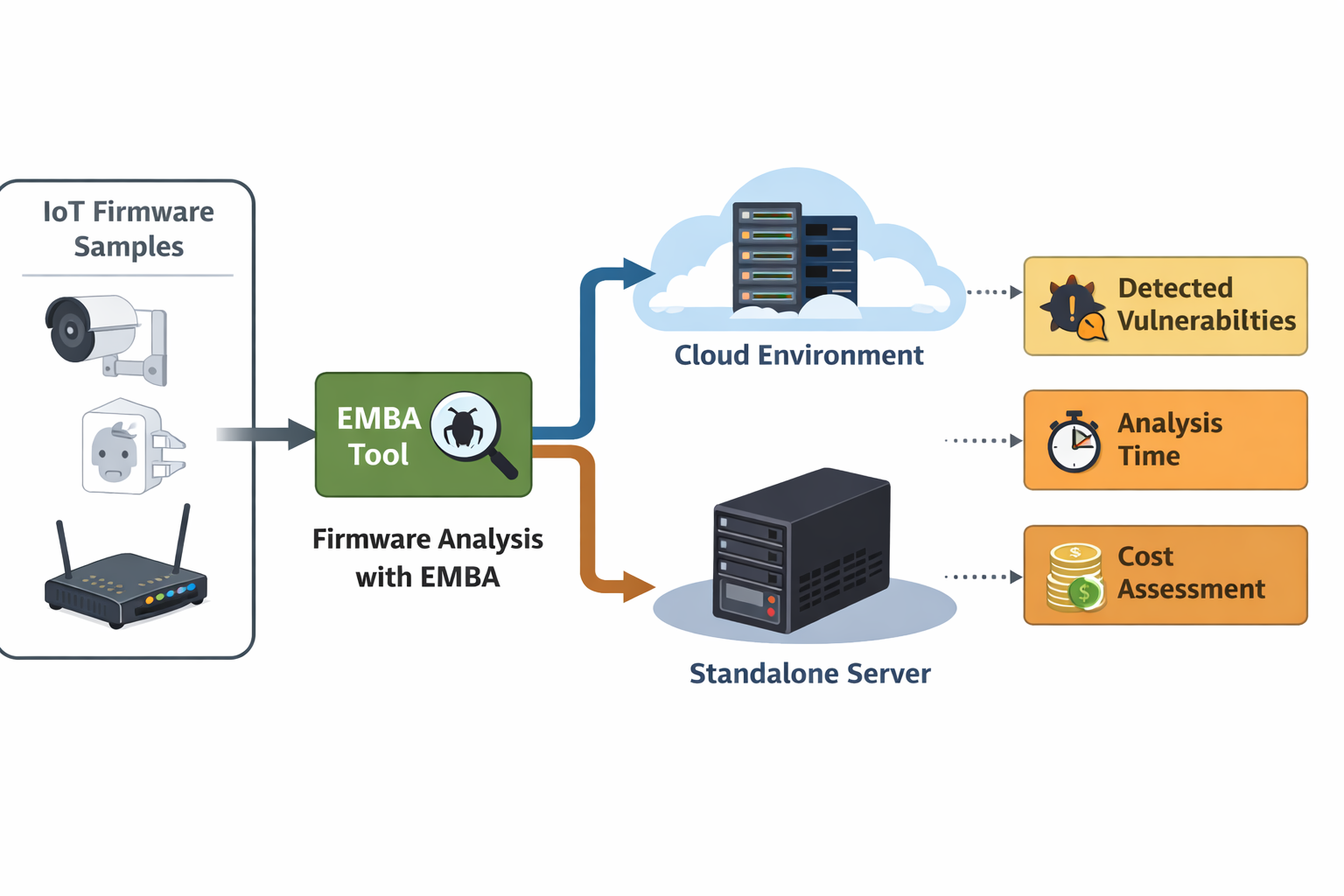

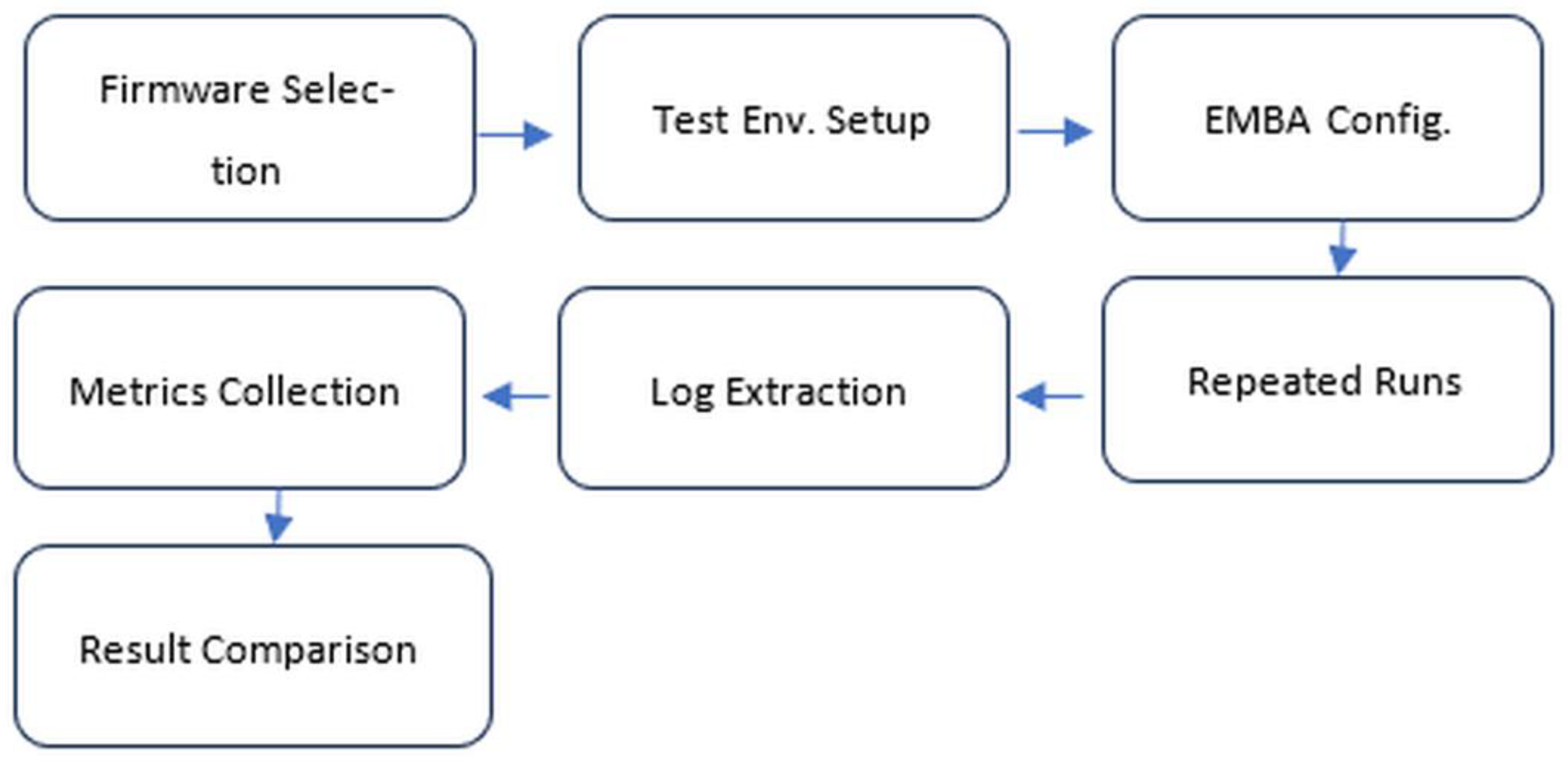

The overall workflow of the EMBA analysis methodology is illustrated in

Figure 1. First, firmware samples are selected based on size categories and representative characteristics. Next, EMBA is configured for the chosen platform, and analysis modules are executed in a controlled and repeatable manner. During execution, runtime data and logs are collected systematically for each firmware sample. Finally, the logs and metrics are extracted and used to assess performance across both standalone servers and the Cloud-based environment. This structured approach ensures comprehensive coverage of firmware behaviors while maintaining experimental reproducibility.

3.1. Firmware Selection and Size Categories

Firmware images were categorized into three representative size groups commonly observed in real-world deployments:

Small: <10 MB

Medium: 10–30 MB

Large: >30 MB

These categories align with typical IoT and Industrial Internet of Things (IioT) scenarios, where smaller images often correspond to consumer devices and larger images to more complex industrial or enterprise systems. From the dataset of approximately 1,500 firmware samples, three firmware samples were selected, one from each size category, based on their ability to execute the majority of EMBA modules. This selection criterion ensures a more meaningful analysis of EMBA’s end-to-end runtime, since many firmware images execute only a subset of modules, leading to incomplete or skewed runtime comparisons.

The chosen samples therefore provide a more accurate representation of the computational resources required for a comprehensive EMBA analysis.

3.2. Experimental Environments

A controlled lab setting was used for the standalone server experiments. Two machines with identical hardware specifications, except for CPU core count, were deployed:

PC1: 4 CPU cores, 32 GB RAM

PC2: 8 CPU cores, 32 GB RAM

This design enables assessment of how EMBA scales additional CPU resources while holding all other factors constant.

For Cloud-based testing, a single Microsoft Azure Virtual Machine (VM) was provisioned with:

8 CPU cores, 32 GB RAM

The Azure VM was intentionally configured to match the more powerful standalone server (PC2) as closely as possible. This alignment ensures that observed performance differences originate from platform characteristics such as virtualization overhead, storage performance, or Cloud scheduling behavior rather than hardware discrepancies. The use of commodity-grade hardware configurations reflects setups accessible to typical practitioners, increasing the practical relevance of the findings.

3.3. EMBA Configuration and Test Execution

This subsection describes the configuration of the EMBA tool, the execution order of analyses, and the system setup used to ensure consistent and reproducible testing across all platforms.

3.3.1. EMBA Versions and Execution Order

To evaluate the evolution of EMBA’s performance and behavior across releases, three consecutive versions of the tool were selected for analysis: EMBA v1.4.1, v1.4.2, and v1.5.0. These versions represent incremental development stages of the tool and allow assessment of changes in module availability, execution behavior, and runtime characteristics.

The experiments were conducted sequentially, and no two firmware analyses were executed simultaneously on the same platform or machine. Each firmware scan was completed before initiating the next test to prevent resource contention and ensure consistent measurement conditions. All scan durations were recorded using the HH:MM:SS format to maintain precision and consistency in runtime reporting.

EMBA v1.4.1 was initially evaluated on a standalone system to establish a baseline. EMBA v1.4.2 was subsequently tested on a higher-performance standalone server to assess the impact of both software updates and increased computational resources. Finally, EMBA v1.5.0, the most recent release at the time of experimentation (October 2024), was evaluated on both a standalone server and a Microsoft Azure Cloud virtual machine using the same execution methodology [

8].

To ensure repeatability and reproducibility, all firmware scans were executed using identical EMBA configurations and the same set of analysis modules. For standalone servers, each test was executed three independent times. All three runs produced highly consistent and nearly identical results, indicating low variance. The results from the final run—representative of all executions—were used in the analysis.

For the Azure virtual machine, only the T8705.bin firmware was executed twice due to the significantly higher cost of Cloud computing. Both runs produced nearly identical outputs in terms of findings and execution time, confirming reproducibility on the Cloud platform. The results from the second run were used in the study.

3.3.2. Scan Profile Configuration

All experiments were conducted using EMBA’s default scan profile with controlled and explicitly documented modifications to balance analysis depth and practical runtime constraints. By default, EMBA disables several long-running modules to optimize scan duration, including S10_binaries_basic_check, S15_radare_decompile_checks, S99_grepit, S110_yara_check, and F20_vul_aggregator [

31].

In addition to the default exclusions, the Ghidra-based decompilation module was manually removed from the scan profile prior to testing. This module was excluded due to its substantial execution time, which would have disproportionately extended scan durations and limited the feasibility of repeated experiments. This adjustment allowed the study to focus on EMBA’s core analysis capabilities while maintaining reasonable time and resource usage.

Across versions, the modified scan profile enabled the execution of 58 modules in EMBA v1.4.1, 60 modules in v1.4.2, and 68 modules in v1.5.0, reflecting the progressive expansion of EMBA’s analysis functionality. All modifications to the scan profile were carefully documented, including the specific configuration lines altered, and screenshots of the configuration file opened in a Nano editor session were captured to support experimental reproducibility.

The YARA parameter remained disabled unless explicitly stated, as enabling YARA-based pattern matching significantly increases scan duration. This configuration choice ensured that all platforms were evaluated under equivalent conditions.

3.3.3. System and Platform Setup

All experiments were conducted on dedicated physical machines running Ubuntu 22.04 LTS, as recommended in EMBA’s documentation, using the x86-64 architecture with sufficient CPU cores and memory for stable execution [

32]. Two standalone servers, differing only in CPU core count, enabled assessment of scalability while controlling other hardware variables. For Cloud-based testing, a Microsoft Azure virtual machine was provisioned with specifications closely matching the higher-performance standalone system, minimizing confounding factors such as virtualization overhead and storage performance.

EMBA supports only x86-64 architecture and officially runs operating systems such as Ubuntu 22.04 and Kali Linux; ARM-based systems were excluded, limiting applicability to embedded environments. All EMBA dependencies were installed according to the official guidelines, and identical software environments and configurations were applied across both standalone and Cloud platforms to ensure consistency [

32].

3.3.4. System Limitations

Three distinct platforms were prepared for testing: two standalone servers (PC1 and PC2) and one Microsoft Azure Cloud virtual machine (VM). Despite this controlled setup, several system-related limitations should be considered when interpreting the results.

The standalone servers were constrained by their hardware configurations. PC1 was equipped with a 4-core Intel Xeon E3-1226 v3 processor and 32 GB of DDR3 RAM, while PC2 provided a more capable setup with an 8-core Intel Core i7 processor and the same memory capacity. Although both systems meet the minimum requirements for running EMBA, they do not represent high-performance or enterprise-grade servers. Consequently, the observed execution times may underrepresent the tool’s potential performance on more powerful hardware, particularly for large or complex firmware images.

The Azure VM used for Cloud-based testing was a Microsoft Azure Standard D8s_v4 instance, configured with 8 virtual CPU cores and 32 GB of RAM. This VM type is optimized for general-purpose workloads rather than compute- or I/O-intensive tasks. Additionally, it lacked local temporary storage and relied on managed disks, which may have introduced additional I/O overhead, potentially affecting execution times relative to standalone deployments.

System resource utilization was monitored during all experiments. Peak memory consumption across both standalone servers and the Azure VM did not exceed approximately 10 GB of RAM, indicating that under the tested conditions and selected firmware samples, EMBA’s performance was not memory-bound. Instead, execution time appeared primarily influenced by CPU processing capacity and disk I/O behavior. Memory usage may vary depending on firmware size, enabled analysis modules, and scan configurations; therefore, these observations are specific to this experimental setup.

Disk space also influenced system stability and performance. Although EMBA requires a minimum of 30 GB of free disk space, at least 100 GB is recommended for optimal operation. In this study, 128 GB was provisioned on all platforms to accommodate extracted firmware files, intermediate artifacts, and analysis outputs. Preliminary attempts to run EMBA with less than the minimum recommended disk space caused operational errors and degraded performance [

32].

Finally, the experimental evaluation focused on a selected subset of firmware images that successfully executed the majority of EMBA modules. While this approach improved comparability and reproducibility, it may not fully capture EMBA’s behavior on firmware that triggers fewer modules or requires alternative analysis paths.

Taken together, these limitations indicate that the reported results reflect performance characteristics within a controlled but constrained experimental environment. Future studies using higher-performance hardware, alternative architecture, and a broader range of firmware samples may provide additional insights into EMBA’s scalability and resource behavior.

4. Results

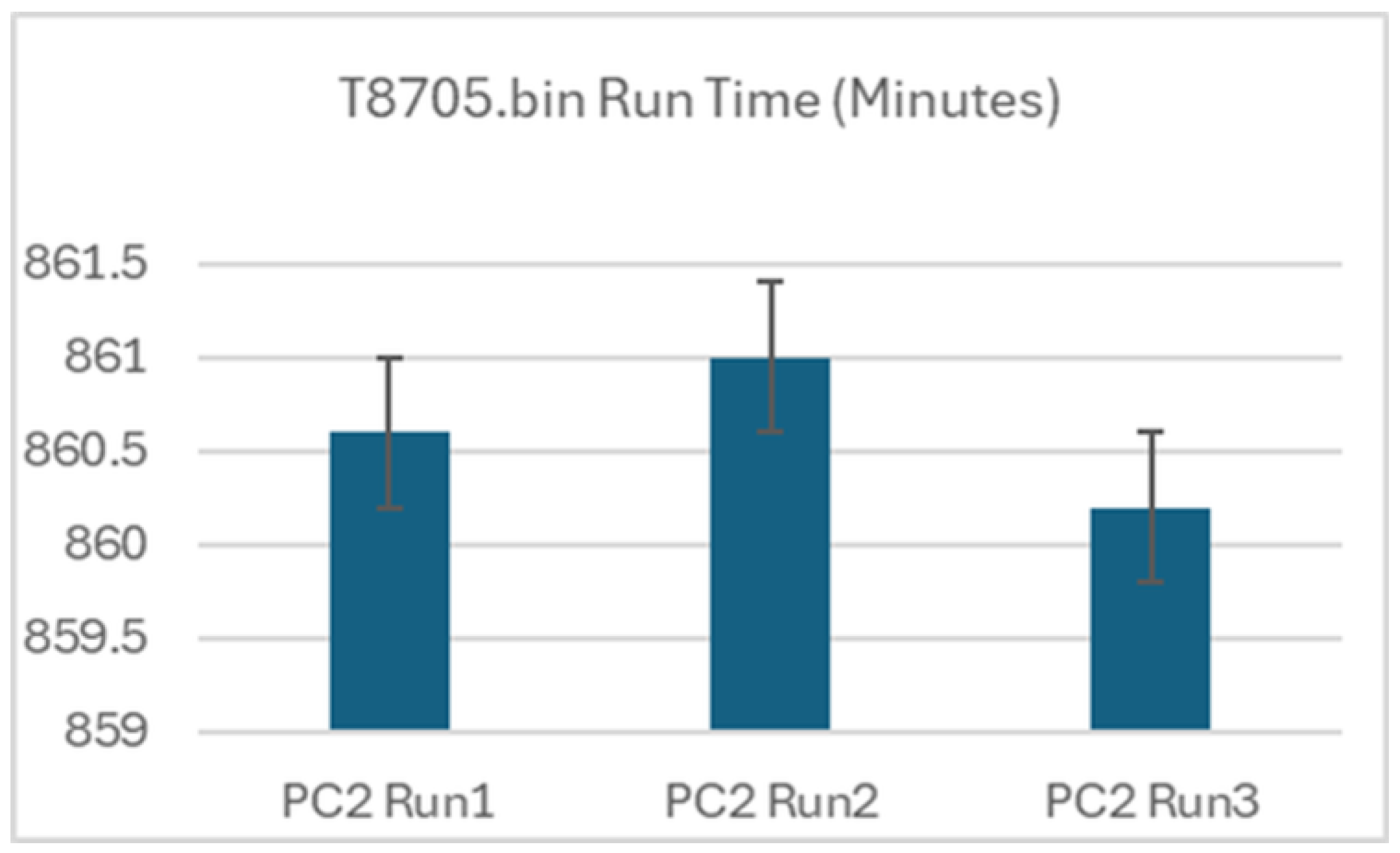

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental results, multiple test repetitions were conducted for the selected firmware sample. For EMBA version 1.5.0 analyzing the T8705.bin firmware, the standalone server (PC2) executed the scan three times, while the Azure virtual machine (VM) executed the same scan twice due to cost constraints.

For all repetitions, the number of detected findings remained constant at 2198, indicating functional consistency of the analysis. Execution times exhibited minimal variation within each platform. On the standalone PC environment (PC2), the three repeated runs yielded execution times of 14:20:35, 14:21:01, and 14:20:13, corresponding to a mean execution time of 860.6 minutes with a standard deviation of approximately 0.40 minutes (~24 seconds). This represents a relative variation of less than 0.05%, demonstrating a high level of repeatability (

Figure 2).

Similarly, the Azure VM runs resulted in execution times of 1 day, 1:45:17 and 1 day, 1:43:20, showing a variation of approximately ±2 minutes between runs. Although a third execution was not performed due to higher operational costs, the close agreement between the two runs provides preliminary evidence of reproducibility within the cloud environment.

This multi-run experimental design enables calculation of basic statistical measures, including mean and standard deviation, directly addressing concerns regarding statistical validation and confirming that observed performance differences are stable and consistent rather than artifacts of isolated measurements.

4.1. EMBA Version 1.4.1 and 1.4.2 Comparison

A detailed performance evaluation of EMBA versions 1.4.1 and 1.4.2 was conducted using identical default scan profiles across two distinct hardware configurations. The systems differed in processor capabilities, with PC1 featuring a quad-core processor and PC2 an octa-core processor. Both systems were equipped with 32 GB of RAM, ensuring sufficient memory for analysis. The most important objective was to assess the number of executed modules, runtime efficiency, and findings across firmware samples of varying sizes.

As shown in

Table 1, the results indicate differences between the two versions and systems. With modified settings, EMBA version 1.4.1 executed 58 modules on PC1, while version 1.4.2 ran 60 modules on PC2 under identical scan profiles. This difference shows software improvements in version 1.4.2 that enable the processing of additional modules. Observations during the tests showed that while modules in version 1.4.1 were executed sequentially, version 1.4.2 introduced the ability to execute certain modules concurrently. Running these modules simultaneously has helped reduce scan times, especially with larger firmware samples, as it takes better advantage of parallel processing.

The correlation between firmware size and scan times also provided additional information. The data show that scan times are not strictly linear with firmware size. For example, the largest firmware sample, S3008.bin (40.8 MB), completed its scan on PC1 in 13 hours, 20 minutes, and 41 seconds, which is significantly shorter than the scan time of 3 days, 13 hours, 1 minute, and 36 seconds for the much smaller T8516.bin (7.04 MB). This finding shows how scan durations are impacted more by the configuration and intricacy of the firmware than by the sheer size of the firmware. The number of scan files, the amount of compression employed, the number of embedded elements, or other components are likely to greatly influence scan durations.

The enhanced runtime efficiency on PC2 reflects both the hardware improvements and the concurrency features introduced in version 1.4.2. These results show the interaction between software improvements in EMBA version 1.4.2 and hardware advancements. Since both EMBA version and hardware configuration changed simultaneously, the observed improvements cannot be attributed solely to software enhancements. The ability of version 1.4.2 to execute modules concurrently, combined with the multi-core architecture of PC2, contributed significantly to runtime reductions. Moreover, the results question the idea that firmware size is the main factor behind scan duration, showing that the structure and complexity of the firmware play a more significant role in performance. Future research could examine these aspects more closely to gain a clearer picture of what truly influences firmware analysis.

4.2. EMBA Version 1.4.2 and 1.5.0 Comparison

The comparison of EMBA versions 1.4.2 and 1.5.0 shows important differences in runtime performance and module execution, tested on PC2 with identical hardware configurations. Both tests ran on a system with an 8-core processor and 32 GB of RAM. The evaluation included three firmware samples of varying sizes: WR940.bin (3.87 MB), T8705.bin (25.5 MB), and R8000.bin (30.2 MB). A key distinction between the two versions was the number of executed modules: EMBA 1.4.2 processed 60 modules, whereas version 1.5.0 executed 68 modules due to the addition of new checks and functionalities with the modified default scan settings.

As shown in

Table 2, for WR940.bin, EMBA 1.4.2 completed the scan in 17 minutes and 47 seconds, while version 1.5.0 took significantly longer at 3 hours, 30 minutes, and 56 seconds. The extended runtime for the smaller firmware sample in version 1.5.0 suggests that the added modules or enhancements may have introduced more comprehensive checks, increasing the overall processing time. In contrast, for the larger firmware sample T8705.bin, version 1.5.0 exhibited a runtime improvement, reducing the scan time from 1 day, 11 hours, 11 minutes, and 31 seconds in version 1.4.2 to 14 hours, 20 minutes, and 35 seconds. Similarly, R8000.chk showed improved efficiency in version 1.5.0, with a runtime of 18 hours, 9 minutes, and 40 seconds, down from 20 hours, 32 minutes, and 4 seconds in version 1.4.2.

The runtime improvements for larger firmware samples in version 1.5.0 can be attributed to enhanced parallel processing capabilities and optimization that enabled the efficient execution of additional modules. These improvements made better use of the multi-core architecture, allowing for faster analysis despite the increased number of modules. However, the extended runtime for WR940.bin suggests that the added modules or checks in version 1.5.0 are the factors contributing to the increased scan duration.

The increase from 60 to 68 modules in version 1.5.0 demonstrates the ongoing expansion of EMBA’s analysis capabilities, reflecting the introduction of new functionalities to enhance the scope and depth of the firmware analysis. While these enhancements improve the tool's effectiveness for larger and more complex firmware, they may also introduce trade-offs in performance for smaller files. This analysis underscores the delicate balance between feature expansion and runtime efficiency in firmware analysis tools. While EMBA 1.5.0 showed clear improvements for larger firmware samples, the extended runtime for WR940.bin highlights the need for further optimization of module execution strategies.

4.3. EMBA Version 1.5.0 and Azure VM Comparison

EMBA version 1.5.0 performance was evaluated in two different environments: a physical machine, PC2, and a virtualized instance on the Microsoft Azure Cloud. Both environments were configured with identical hardware specifications, featuring 8-core processors and 32 GB of RAM with Ubuntu 22.04, ensuring consistency in the experimental setup. EMBA’s default scan configuration was modified, and 68 modules were executed on three firmware samples: WR940.bin, T8705.bin, and R8000.chk. The results showed important differences in performance between the two environments, particularly in execution times and the number of findings.

As shown in

Table 3, the physical machine PC2 generally outperformed the Azure Cloud virtual machine in terms of scan duration, with shorter execution times for WR940.bin and T8705.bin. On PC2, WR940.bin was completed in 3 hours, 30 minutes, and 56 seconds; T8705.bin required 14 hours, 20 minutes, and 35 seconds; and R8000.chk took 18 hours, 9 minutes, and 40 seconds. In contrast, the Azure Cloud VM demonstrated longer processing times for WR940.bin and T8705.bin, with WR940.bin completed in 10 hours, 48 minutes, and 48 seconds, and T8705.bin requiring 1 day, 1 hour, 45 minutes, and 17 seconds. However, for R8000.chk, the Azure Cloud VM performed faster, completing the analysis in 16 hours, 53 minutes, and 55 seconds compared to PC2’s 18 hours, 9 minutes, and 40 seconds. This anomaly suggests that specific workload characteristics or resource allocation strategies in the Azure Cloud environment may occasionally benefit certain types of analysis. Due to budget limitations, we had limited time to conduct the experiments in the Cloud, but the tests we conducted provided representative examples of performance, even if they were not comprehensive.

While both environments produced largely comparable results in terms of findings, moderate variations were observed. For WR940.bin and T8705.bin, the number of findings was nearly identical, with only a slight difference for WR940.bin (2537 on PC2 vs. 2536 on the Azure Cloud VM). However, for R8000.chk, a more noticeable variation was observed, with PC2 identifying 2901 findings compared to 3012 on the Azure Cloud VM. This difference should be investigated further in future work to better understand the impact of execution environment on vulnerability detection results.

These results show the importance of the execution environment in determining the efficiency and reliability of firmware analysis. While physical hardware generally provides superior performance due to dedicated resources and lower latency, certain tasks, as evidenced by the R8000 results, may benefit from the dynamic resource allocation in cloud environments.

4.4. EMBA Version 1.4.1 with Different Firmware Samples

EMBA version 1.4.1 tests were conducted on PC1. PC1 is equipped with a 4-core processor and 32 GB of RAM. Also, predefined modifications were made to EMBA's default scanning configuration. In addition, the tests conducted with EMBA version 1.4.1 analyzed three firmware samples, T8516, T8705, and S3008, focusing on runtime and performance across various modules. The total scan durations varied significantly, with T8516 taking approximately 85 hours, T8705 requiring 68 hours, and S3008 completing in about 13 hours. These differences reflect the varying complexity and size of the firmware samples.

Key modules like P60_deep_extractor and P61_binwalk_extractor showed notable runtime disparities. For instance, P60_deep_extractor took 55 minutes for T8516, 99 minutes for T8705, and only 1 minute 40 seconds for S3008. Similarly, S09_firmware_base_version_check had an extensive runtime for all samples, particularly T8516 and T8705, consuming 34 and 46 hours, respectively, while S3008 required just over 5 hours. Analytical modules like S99_grepit and F20_vul_aggregator also accounted for a significant portion of the runtime, demonstrating the computational intensity of detailed vulnerability assessments. The results indicate EMBA’s capacity to adapt to different firmware architectures while highlighting the variable demands imposed by different firmware complexities.

4.5. Module-Level Performance Analysis of EMBA v1.5.0 on PC2 and Azure VM

EMBA scan results obtained from the PC2 standalone server and Azure Cloud VMs, using three firmware samples (WR940, T8705, and R8000), reveal notable performance discrepancies (see Appendix A.1 Detailed EMBA Module Execution Times). Both environments were configured with identical hardware specifications. 8 CPU cores, 32 GB of RAM, and at least 128 GB of free disk space. Our tests show that EMBA scan times differ notably between the two platforms. Overall, the PC2 generally showed faster module completion times compared to the Azure Cloud VM, with some variations in certain modules. For example, the overall scan time for WR940 was 3:30:56 (HH:MM:SS) on PC2, less than half the time required by the Azure Cloud VM, which was 10:48:48. Similarly, for T8705, PC2 finished in 14:20:35, while the Azure Cloud VM took 25:45:17. However, for the R8000 firmware, the Azure Cloud VM was only slightly faster, with a total time of 16:53:55 versus 18:09:40 on PC2. This shows that the performance disparity between the two environments is not consistent for all firmware samples.

When examining specific modules, several anomalies have been observed. For example, in the WR940 and T8705 firmware samples, S09 (firmware base version check) took significantly more time on the Azure Cloud VM than on PC2, with durations like 21:15:18 on the Azure Cloud VM for T8705 compared to just 10:42:58 on PC2. However, the R8000 firmware showed the reverse pattern, where Azure Cloud VM 2:02:43 outperformed PC2 3:37:27. This indicates that some modules are influenced by the specific firmware sample, which might have unique attributes that either exacerbate or mitigate the environmental performance differences. The S15 (Radare decompile checks) module showed substantial time consumption in both environments. For the R8000 firmware, Azure Cloud VM required 15:11:15, while PC2 completed the task in 16:29:21, further indicating that decompilation tasks are particularly resource-intensive and might behave differently depending on the environment.

Certain modules, like S99 (grepit), exhibited a similar trend, where Azure Cloud VMs’ execution time was almost double that of PC2 for the T8705 firmware sample. However, for R8000, Azure Cloud VM’s time of 3:49:06 was closer to PC2's 5:02:12, suggesting that I/O and disk read/write operations in the Azure Cloud environment might be contributing to these performance disparities. Modules such as S02 (UEFI_FwHunt) and S36 (lighttpd) showed relatively consistent performance across both platforms, which implies that certain types of tasks, perhaps those less reliant on raw I/O or system-level operations, are less sensitive to the differences in environment. The variability in execution times for different modules and firmware samples hints at a complex interaction between the hardware environment and the nature of the tasks being executed. For example, S17 (CWE checker) and S13 (weak function check) revealed marked performance differences, especially with the R8000 firmware, where the Azure Cloud VM took significantly longer than PC2.

On the other hand, certain modules like S115 (user-mode emulator) performed similarly across both platforms. These observations show that specific tasks like deep system analysis or computationally intensive processing may be more affected by the virtualization overhead in the Azure Cloud. On the other hand, other tasks that are less resource-intensive or involve more straightforward processing may exhibit less of a performance gap between the two environments.

Several factors could cause these observed differences. Virtualization overhead in the Azure Cloud VM environment is a likely cause for the slower performance in certain modules, as the abstraction layer could introduce latency, particularly in resource-intensive tasks such as binary analysis and decompilation. Additionally, resource contention could arise in a cloud-based setup, where virtual machines may share physical resources with other instances, affecting performance stability. Network-related delays might also play a role, especially in modules that require external communication or updates during execution. Furthermore, differences in disk I/O handling between the physical PC2 server and the Azure Cloud VM may explain some of the variations, particularly for tasks that involve large-scale data processing or frequent disk access. Ultimately, while both environments offer similar raw hardware specifications, the cloud-based Azure VM environment seems to face additional challenges, likely due to the complexities of virtualization and resource management in a shared infrastructure. Modules like S99_grepit and S118_busybox_verifier exceed 15 hours due to their computational complexity, such as binary decompilation, extensive text searches, and compressed system analysis. Standalone PCs handle these tasks faster due to dedicated resources and efficient local I/O. In contrast, Azure Cloud VMs often face I/O bottlenecks, resource contention, and network latency, leading to longer execution times. Optimizing VM performance with faster storage, dedicated resources, and task parallelization, or using a hybrid setup combining PCs and VMs, can mitigate these delays and enhance efficiency.

The test results also indicated a difference between overall scan time and total module time. Moreover, the results provide supplementary observations into the scanning process. Overall scan time reflects the cumulative time taken by all modules when considered individually, whereas total module time (HH:MM:SS) measures the actual duration of a single EMBA scan. The observed discrepancy between these metrics, particularly in EMBA version 1.4.2, can be attributed to the concurrent execution of certain modules. Unlike version 1.4.1, which processes modules sequentially, version 1.4.2 introduced a concurrency feature that allows multiple modules to run simultaneously. Parallel processing capability greatly reduces the overall module time (HH:MM:SS), while keeping the overall scanning time unchanged, which indicates the cumulative input from all the modules. This advancement not only increases the efficiency of operations but also signifies the essential role of exploiting parallelism in modern-day firmware analysis methods.

5. Discussion

The results presented in the previous section provide a quantitative comparison of EMBA’s execution behavior across standalone and cloud-based platforms under controlled and repeatable conditions. Building on these findings, this section interprets the observed performance characteristics in a broader operational context, focusing on platform-specific trade-offs, deployment implications, and practical considerations for firmware security analysis. Rather than reiterating numerical results, the discussion emphasizes how differences in execution environment influence scalability, cost efficiency, reproducibility, and long-term usability of EMBA in real-world settings.

5.1. Platform Level Implications of EMBA Deployment

The Microsoft Azure Cloud platform offers several measurable advantages for executing EMBA-based firmware analysis, particularly in terms of scalability and accessibility. Cloud infrastructures enable dynamic resource allocation, allowing EMBA to be deployed on virtual machines with configurable CPU and memory resources. This flexibility supports the analysis of firmware images with varying computational demands, which are difficult to achieve on personal computers with fixed hardware configurations. In addition, cloud-based deployments facilitate remote access, enabling geographically distributed teams to perform analyses without reliance on dedicated on-site hardware.

From a cost perspective, cloud platforms follow a pay-as-you-go model that eliminates the need for upfront hardware investment. This model can be advantageous for occasional or short-term analysis tasks, where resources are provided only when needed. However, this benefit must be balanced against operational costs incurred during sustained usage. In this study, running four firmware scans on an Azure virtual machine with 8 CPU cores and 32 GB of RAM resulted in an approximate cost of $250. While acceptable for limited experimentation, such expenses may scale rapidly with increased analysis frequency or higher-performance instance requirements when analyses are performed frequently or when higher-performance virtual machines are required to reduce execution time. Consequently, the cost–performance trade-off becomes a critical factor in long-term deployment decisions.

Security, compliance, and operational complexity also represent important considerations in cloud-based firmware analysis. Analyzing potentially sensitive firmware images in a shared cloud environment requires strict access control mechanisms and adherence to organizational or regulatory compliance requirements. Furthermore, deploying and maintaining EMBA on cloud virtual machines may involve additional technical overhead, including dependency management, permission handling, and system updates. Data transfer overhead is another limitation, as importing and exporting large firmware images can introduce delays and reduce overall workflow efficiency compared to locally hosted systems.

In contrast, standalone servers provide a controlled and predictable environment for EMBA-based firmware analysis. Unlike cloud platforms, standalone deployments eliminate variability introduced by shared infrastructure, virtualization overhead, and network-dependent operations. This deterministic behavior is particularly important for experimental rigor and reproducibility, as repeated scans under identical conditions yield consistent execution times and findings.

From an operational standpoint, standalone servers offer full control over system configuration, storage, and access policies, thereby reducing security and compliance concerns associated with external cloud environments. Firmware images remain locally stored, avoiding both data transfer delays and potential exposure risks. Although standalone servers lack the elasticity of cloud platforms, their fixed hardware configurations ensure stable long-term performance, which is advantageous for continuous or large-scale firmware analysis workloads.

Furthermore, when EMBA is used on a regular basis, the one-time investment cost of a standalone server can become more economical than recurring cloud usage fees. As demonstrated in this study, repeated firmware scans on a local server achieved consistent execution times with minimal variance, supporting the suitability of standalone deployments for systematic, repeatable, and methodologically rigorous firmware security assessments.

5.2. Future Research

Future research should build upon the findings of this study by further strengthening EMBA’s performance evaluation, scalability, and deployment flexibility across diverse environments. One immediate direction is the systematic investigation of module-level optimization, where non-essential analysis modules are selectively excluded or dynamically enabled based on firmware characteristics. Controlled experiments are required to determine how such configurations affect execution time, detection coverage, and overall analytical accuracy.

Another important research direction involves cross-platform cloud comparisons. While this study focused on Microsoft Azure, future work should extend the evaluation to additional cloud providers, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Google Cloud Platform (GCP). Comparative analyses across multiple cloud environments would provide deeper insights into performance variability, cost-efficiency, and deployment trade-offs, enabling informed multi-cloud or hybrid deployment strategies for firmware security analysis.

The role of high-performance hardware also warrants further investigation. Evaluating EMBA on more advanced standalone servers and compute-optimized cloud instances could help quantify performance gains and identify diminishing returns in relation to cost. Such studies would be particularly valuable for organizations seeking to balance execution speed, reproducibility, and operational expenses in large-scale firmware analysis workflows.

Expanding the diversity and scale of firmware samples represents another key avenue for future work. Including a broader range of firmware sizes, architectures, and vendor ecosystems would improve the generalizability of findings and help uncover edge cases that may stress EMBA’s analysis pipeline. Additionally, incorporating complementary firmware analysis tools alongside EMBA could support comparative evaluations, highlighting both strengths and limitations and identifying opportunities for targeted tool enhancements.

A particularly promising direction for future research is the evaluation of EMBArk, the web-based enterprise interface for EMBA. EMBArk introduces a centralized and system-independent approach to firmware analysis, which is especially relevant for enterprise and government environments. Future studies should assess EMBArk’s performance, scalability, and usability in large-scale deployments, focusing on centralized management, result aggregation, and auditability.

Further research may also explore the integration of EMBArk with vulnerability databases, threat intelligence feeds, and Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems. Such integrations could enable real-time risk assessment and transform EMBArk from a visualization layer into a comprehensive firmware security management platform, supporting cloud-native and collaborative security workflows.

Overall, future work should focus on coordinated improvements across both the backend analysis engine (EMBA) and the frontend management interface (EMBArk), with the goal of achieving higher analytical rigor, improved performance, and broader applicability across varied operational and deployment contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the behavior of EMBA, an open-source firmware analysis framework, across standalone servers and cloud-based environments. The analysis focused on execution time, repeatability, cost implications, and operational constraints across different deployment environments. Rather than introducing EMBA as a new tool, the work examined its practical behavior and performance characteristics under controlled and reproducible testing conditions, addressing a gap in empirical evaluations of firmware analysis frameworks across heterogeneous platforms.

The experimental results demonstrate that EMBA produces stable and repeatable outcomes when identical firmware samples and configurations are used. Repeated executions within the same deployment environment yielded nearly identical execution times and identical numbers of findings, confirming that the observed performance differences were not artifacts of single-run measurements. This directly addresses concerns regarding experimental rigor and supports the reliability of the reported comparisons between platforms and EMBA versions.

The findings highlight clear trade-offs between cloud-based and standalone deployments. The Azure Cloud platform offers flexibility, remote accessibility, and elastic resource provisioning, which can be advantageous for collaborative or short-term analysis scenarios. However, for computer-intensive and repeated firmware scans, cloud deployment introduces significant recurring costs, increased deployment complexity, and additional considerations related to data transfer and security. In contrast, standalone servers provide a more predictable and controlled execution environment, enabling reproducible analyses with minimal variance and substantially lower long-term costs when EMBA is used frequently. While standalone systems lack elasticity, their performance and fixed cost structure make them well suited for continuous or large-scale firmware security assessments.

Importantly, this work provides empirical evidence that deployment environment selection has a measurable impact on the efficiency, cost, and practicality of firmware security analysis, even when the same analysis framework, firmware inputs, and configurations are used. By combining controlled experimentation, repeated measurements, and platform-specific observations, the study clarifies the operational conditions under which cloud-based or standalone deployments are more appropriate.

Overall, the results indicate that no single deployment model is universally optimal for EMBA based firmware analysis. Instead, deployment decisions should be aligned with workload scale, analysis frequency, operational complexity, and budget constraints. For limited or short-term analysis scenarios such as a small number of firmware scans (e.g., fewer than ten) cloud-based deployment on platforms such as Azure can be cost-effective and operationally acceptable, as it avoids upfront hardware investment while providing controlled access and managed authentication mechanisms. However, as the volume and frequency of firmware analyses increase, recurring cloud costs and operational overhead become significant. In such cases, acquiring and operating a standalone analysis system represents a more economical and sustainable approach. While cloud platforms offer advantages in terms of centralized access control, login management, and isolation, they also impose additional operational burden related to instance management, monitoring, and cost tracking. Consequently, organizations should evaluate not only performance metrics but also long-term operational effort and security requirements when selecting an execution environment for EMBA-based firmware security workflows.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.N. and O.U.; methodology, K.S.N.; software, K.S.N.; validation, K.S.N. and O.U.; formal analysis, K.S.N.; investigation, K.S.N.; resources, K.S.N.; data curation, K.S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.N.; writing—review and editing, N.L.B.; visualization, K.S.N.; supervision, O.U.; project administration, K.S.N.; funding acquisition, O.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Cyber Manufacturing Innovation Institute (CyManII).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to the proprietary nature of the firmware samples analyzed, the raw firmware files cannot be publicly shared. All analysis procedures, configurations, and summary results are described in the manuscript to allow reproducibility and verification of the study’s findings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy Cyber Manufacturing Innovation Institute. The authors thank CyManII for providing support that made this research possible. Used ChatGPT only for minor language and phrasing edits.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IOT |

Internet of Things |

| IIOT |

Industrial Internet of Things |

| VM |

Virtual Machine |

| PC |

Personal Computer |

| SAST |

Static Application Security Testing |

| SBOM |

Software Bill of Materials |

| TCO |

Total Cost of Ownership |

| SSH |

Secure Shell |

| AMZ |

Amazon Web Service |

| GCP |

Google Cloud Platform |

| CGI |

Common Gateway Interface |

Appendix A

Table A1.

EMBA scan output showing per-module execution times for three firmware samples (WR940, T8705, and R8000) on the standalone PC2 and Azure VM platforms.

Table A1.

EMBA scan output showing per-module execution times for three firmware samples (WR940, T8705, and R8000) on the standalone PC2 and Azure VM platforms.

| |

WR940 |

T8705 |

R8000 |

| Module Name |

PC2 Duration |

Azure VM Duration |

PC2 Duration |

Azure VM Duration |

PC2 Duration |

Azure VM Duration |

| P02_firmware_bin_file_check |

0:00:04 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:12 |

0:00:21 |

0:00:07 |

0:00:07 |

| P40_DJI_extractor |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

| P55_unblob_extractor |

0:00:22 |

0:00:18 |

0:01:59 |

0:01:58 |

0:01:08 |

0:00:37 |

| P60_deep_extractor |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

1:24:15 |

1:31:44 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

| P61_binwalk_extractor |

0:00:00 |

0:00:01 |

0:00:00 |

0:04:05 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

| P65_package_extractor |

0:00:01 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:01 |

0:00:01 |

| P99_prepare_analyzer |

0:00:28 |

0:00:35 |

0:05:01 |

0:04:45 |

0:01:59 |

0:01:02 |

| S26_kernel_vuln_verifier |

0:00:51 |

0:00:36 |

0:08:29 |

0:17:25 |

0:03:17 |

0:02:30 |

| S24_kernel_bin_identifier |

0:00:48 |

0:00:32 |

0:08:26 |

0:17:22 |

0:03:13 |

0:02:27 |

| S12_binary_protection |

0:09:44 |

0:09:55 |

0:08:24 |

0:13:09 |

0:47:31 |

0:23:03 |

| S09_firmware_base_version_check |

0:48:45 |

0:57:18 |

10:42:58 |

21:15:18 |

3:37:27 |

2:02:43 |

| S02_UEFI_FwHunt |

0:00:01 |

0:00:00 |

1:01:41 |

1:46:37 |

0:00:01 |

0:00:00 |

| S03_firmware_bin_base_analyzer |

0:00:21 |

0:00:16 |

10:53:07 |

7:02:49 |

0:01:18 |

0:00:39 |

| S04_windows_basic_analysis |

0:00:01 |

0:00:02 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:01 |

0:00:09 |

0:00:13 |

| S05_firmware_details |

0:00:07 |

0:00:08 |

0:00:58 |

0:00:39 |

0:00:07 |

0:00:09 |

| S06_distribution_identification |

0:00:04 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:30 |

0:00:16 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:05 |

| S07_bootloader_check |

0:00:11 |

0:00:06 |

0:00:43 |

0:21:18 |

0:00:16 |

0:00:11 |

| S08_package_mgmt_extractor |

0:00:08 |

0:00:03 |

0:07:14 |

0:11:58 |

0:00:09 |

0:00:04 |

| S10_binaries_basic_check |

0:02:03 |

0:02:16 |

0:01:40 |

0:00:54 |

0:09:41 |

0:06:50 |

| S13_weak_func_check |

0:12:19 |

0:13:35 |

0:08:50 |

0:11:17 |

2:09:45 |

1:06:04 |

| S14_weak_func_radare_check |

0:29:48 |

0:32:54 |

0:36:08 |

0:09:48 |

2:46:59 |

1:20:15 |

| S15_radare_decompile_checks |

1:42:50 |

2:04:56 |

2:38:05 |

1:20:17 |

16:29:21 |

15:11:15 |

| S16_ghidra_decompile_checks |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

| S17_cwe_checker |

0:01:25 |

1:29:16 |

0:00:27 |

1:25:56 |

0:10:31 |

6:47:38 |

| S18_capa_checker |

0:02:18 |

0:03:46 |

0:21:02 |

1:03:31 |

0:11:55 |

0:12:29 |

| S19_apk_check |

0:00:02 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:01 |

0:00:03 |

| S20_shell_check |

0:00:43 |

0:01:01 |

0:31:29 |

0:21:06 |

0:02:13 |

0:02:28 |

| S21_python_check |

0:00:02 |

0:00:03 |

0:13:37 |

0:07:43 |

0:00:02 |

0:00:04 |

| S22_php_check |

0:00:38 |

0:00:58 |

0:02:25 |

0:01:33 |

0:00:41 |

0:01:01 |

| S23_lua_check |

0:00:21 |

0:00:22 |

0:17:20 |

0:07:47 |

0:01:10 |

0:00:49 |

| S25_kernel_check |

0:02:26 |

0:04:16 |

0:03:04 |

0:01:53 |

0:03:10 |

0:03:54 |

| S27_perl_check |

0:00:04 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:06 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:02 |

0:00:05 |

| S35_http_file_check |

0:04:24 |

0:06:56 |

0:06:04 |

0:05:51 |

0:06:19 |

0:10:45 |

| S36_lighttpd |

0:00:04 |

0:00:09 |

0:00:08 |

0:00:10 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:09 |

| S40_weak_perm_check |

0:00:09 |

0:00:18 |

0:00:18 |

0:00:14 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:10 |

| S45_pass_file_check |

0:00:07 |

0:00:16 |

0:00:57 |

0:01:22 |

0:00:14 |

0:00:30 |

| S50_authentication_check |

0:00:26 |

0:00:49 |

0:01:07 |

0:00:57 |

0:00:12 |

0:00:22 |

| S55_history_file_check |

0:00:03 |

0:00:06 |

0:00:11 |

0:00:06 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:04 |

| S60_cert_file_check |

0:00:03 |

0:00:05 |

0:01:08 |

0:01:03 |

0:07:36 |

0:00:19 |

| S65_config_file_check |

0:00:14 |

0:00:25 |

0:01:31 |

0:01:46 |

0:00:37 |

0:00:31 |

| S75_network_check |

0:00:05 |

0:00:08 |

0:00:19 |

0:00:15 |

0:00:07 |

0:00:06 |

| S80_cronjob_check |

0:00:02 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:13 |

0:00:10 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:04 |

| S85_ssh_check |

0:00:05 |

0:00:08 |

0:00:22 |

0:00:15 |

0:00:09 |

0:00:07 |

| S90_mail_check |

0:00:02 |

0:00:02 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:02 |

| S95_interesting_files_check |

0:00:13 |

0:00:24 |

0:00:31 |

0:00:28 |

0:00:18 |

0:00:12 |

| S99_grepit |

0:55:15 |

1:06:06 |

11:03:09 |

21:23:05 |

5:02:12 |

3:49:06 |

| S100_command_inj_check |

0:00:02 |

0:00:06 |

0:00:07 |

0:00:09 |

0:03:06 |

0:02:15 |

| S106_deep_key_search |

0:00:29 |

0:00:44 |

0:02:11 |

0:04:21 |

0:00:39 |

0:00:53 |

| S107_deep_password_search |

0:00:59 |

0:00:49 |

0:18:12 |

0:12:16 |

0:02:46 |

0:01:12 |

| S108_stacs_password_search |

0:00:22 |

0:00:30 |

0:07:19 |

0:09:21 |

0:01:09 |

0:01:00 |

| S109_jtr_local_pw_cracking |

1:07:24 |

1:10:03 |

0:11:41 |

0:10:01 |

0:00:24 |

0:00:07 |

| S110_yara_check |

0:02:56 |

0:03:28 |

0:55:44 |

1:36:16 |

0:25:33 |

0:28:57 |

| S115_usermode_emulator |

0:06:53 |

0:08:05 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:05 |

0:31:47 |

0:29:38 |

| S116_qemu_version_detection |

0:05:12 |

0:09:20 |

0:00:02 |

0:00:02 |

0:05:14 |

0:19:33 |

| S118_busybox_verifier |

0:19:30 |

0:03:24 |

9:04:40 |

18:58:56 |

1:31:57 |

0:26:35 |

| L10_system_emulation |

1:12:02 |

7:16:48 |

0:00:00 |

0:00:01 |

0:36:37 |

0:41:56 |

| L15_emulated_checks_nmap |

0:01:07 |

0:02:03 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:05:11 |

0:03:13 |

| L20_snmp_checks |

0:00:01 |

0:00:00 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:00:01 |

0:00:01 |

| L22_upnp_hnap_checks |

0:00:04 |

0:00:06 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:00:01 |

0:00:04 |

| L23_vnc_checks |

0:00:00 |

0:00:00 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:00:00 |

0:00:01 |

| L25_web_checks |

0:00:01 |

0:31:37 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:00:02 |

0:00:01 |

| L35_metasploit_check |

0:01:24 |

0:19:42 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:14:15 |

0:19:08 |

| L99_cleanup |

0:00:02 |

0:00:01 |

n/a |

n/a |

0:00:01 |

0:00:01 |

| F02_toolchain |

0:00:03 |

0:00:02 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:03 |

0:00:04 |

0:00:05 |

| F05_qs_resolver |

0:00:14 |

0:00:47 |

0:00:12 |

0:00:27 |

0:00:44 |

0:00:52 |

| F10_license_summary |

0:00:05 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:15 |

0:00:13 |

0:00:12 |

| F15_cyclonedx_sbom |

0:00:04 |

0:00:14 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:07 |

0:00:05 |

0:00:06 |

| F20_vul_aggregator |

0:30:49 |

0:30:23 |

0:29:47 |

0:35:01 |

0:35:57 |

0:32:00 |

| F50_base_aggregator |

0:00:16 |

0:00:19 |

0:00:16 |

0:00:19 |

0:00:27 |

0:00:29 |

| Overall Scan Time |

3:30:56 |

10:48:48 |

14:20:35 |

25:45:17 |

18:09:40 |

16:53:55 |

| Total Module Time |

8:08:06 |

17:18:00 |

52:04:49 |

81:25:06 |

36:16:32 |

34:57:32 |

References

- Vailshery, L.S. Internet of Things (IoT) – Statistics & Facts. Statista 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/2637/internet-of-things/#topicOverview (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- EMBA. People in EMBA Organization. GitHub 2025. Available online: https://github.com/orgs/e-m-b-a/people (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- CyberNoz. EMBA: Open-Source Security Analyzer for Embedded Devices. CyberNoz 2023. Available online: https://cybernoz.com/emba-open-source-security-analyzer-for-embedded-devices/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- EMBA. SBOM Environment. GitHub Wiki 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/wiki/SBOM-environment (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- EMBA. AI-Supported Firmware Analysis. GitHub Wiki 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/wiki/AI-supported-firmware-analysis (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Eckmann, P. EMBA: An Open-Source Firmware Analysis Tool. Medium 2021. Available online: https://p4cx.medium.com/emba-b370ce503602 (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- EMBA. Feature Overview. GitHub Wiki 2024. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/wiki/Feature-overview (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- EMBA. EMBA Releases. GitHub 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/releases/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- EMBA. EMBArk: Graphical Interface for Firmware Analysis. GitHub 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/embark (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Conti, M.; et al. Internet of Things Security and Forensics: Challenges and Opportunities. arXiv 2018. [CrossRef]

- TechTarget. White-Box Testing Definition. TechTarget 2025. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchsoftwarequality/definition/white-box (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Verma, A.; Khatana, A.; Chaudhary, S. A Comparative Study of Black Box Testing and White Box Testing. Int. J. Computer Sciences and Engineering 2017, 5, 301–304.

- Shwartz, O.; et al. Reverse Engineering IoT Devices: Effective Techniques and Methods. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 4965–4976. [CrossRef]

- Tamilkodi, R.; et al. Exploring IoT Device Vulnerabilities Through Malware Analysis and Reverse Engineering. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics (ICDICI), IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–10.

- Votipka, D.; et al. An Observational Investigation of Reverse Engineers’ Processes. arXiv 2019. [CrossRef]

- EMBA. The EMBA Book—Chapter 2: Analysis Core. GitHub Wiki 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/wiki/The-EMBA-book-%E2%80%90-Chapter-2%3A-Analysis-Core (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Anonymous. Leveraging Automated Firmware Analysis with the Open-Source Firmware Analyzer EMBA. Medium 2024. Available online: https://medium.com/@iugkhgf/leveraging-automated-firmware-analysis-with-the-open-source-firmware-analyzer-emba-46d30d587a87 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Aggarwal, A.; Jalote, P. Integrating Static and Dynamic Analysis for Detecting Vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC’06), IEEE, 2006; Vol. 1.

- Ferrara, P.; et al. Static Analysis for Discovering IoT Vulnerabilities. Softw. Tools Technol. Transfer 2021, 23, 71–88.

- EMBA. The EMBA Book—Chapter 3: Analysis Core. GitHub Wiki 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/wiki/The-EMBA-book-%E2%80%90-Chapter-3%3A-Analysis-Core (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- EMBA. The EMBA Book—Chapter 4: System Emulation. GitHub Wiki 2025. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/wiki/The-EMBA-book-%E2%80%90-Chapter-4%3A-System-Emulation (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Goseva-Popstojanova, K.; Perhinschi, A. On the Capability of Static Code Analysis to Detect Security Vulnerabilities. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 68, 18–33.

- Zhou, W.; Shen, S.; Liu, P. IoT Firmware Emulation and Its Security Application in Fuzzing: A Critical Revisit. Future Internet 2025, 17, 19. [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, O.; et al. Reverse Engineering: Techniques, Applications, Challenges, Opportunities. Int. Res. J. Modernization Eng. Technol. Sci. 2024, 6.

- EMBA. EMBA GitHub Main Repository. GitHub 2024. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Müller, T. Internet of Vulnerable Things. Technical Report 2022. Available online: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/otsmr/internet-of-vulnerable-things/main/Internet_of_Vulnerable_Things.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- De Ruck, D.; et al. Linux-Based IoT Benchmark Generator for Firmware Security Analysis Tools. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES ’23), 2023; Article No. 19, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Al-Said Ahmad, A.; Andras, P. Scalability Analysis Comparisons of Cloud-Based Software Services. J. Cloud Comput. 2019, 8, 10.

- Bouras, C.; et al. Techno-Economic Analysis of Cloud Computing Supported by 5G: A Cloud vs. On-Premise Comparison. In Advances on Broadband Wireless Computing, Communication and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Vol. 570, pp. 1–12.

- Fisher, C. Cloud versus Standalone Server Computing. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 1991–2006.

- EMBA. Default Scan Profile. GitHub 2024. Available online: https://github.com/e-m-b-a/emba/blob/master/scan-profiles/default-scan.emba (accessed on 1 November 2024).