1. Introduction

Residential heating is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in Europe, where cold winters and high comfort standards drive substantial energy demand. Across the continent, most homes rely on fossil fuel combustion for heating, with natural gas, oil, and coal accounting for most of the energy used in household heating systems. This widespread dependence on fossil fuels makes residential heating one of the leading sources of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other greenhouse gas emissions, directly affecting air quality and accelerating climate change. Recent estimates indicate that the residential sector accounts for nearly 30% of Europe’s total energy consumption, with heating representing the largest share of this demand. Residential heating alone produces approximately 12% of the European Union’s total CO₂ emissions [

1], a figure that varies with seasonal temperatures and energy sources. Countries with colder climates, particularly in Northern and Eastern Europe, often exhibit even higher emissions due to extended heating periods and lower average temperatures.

In the United States, buildings account for roughly 39% of all primary energy consumption and 74% of electricity use [

2]. Thermal end uses—including space conditioning, water heating, and refrigeration—represent about 50% of building energy demand and are projected to increase in the coming years. This growing demand underscores the urgent need for innovative solutions to reduce energy consumption and mitigate environmental impacts in residential buildings worldwide.

Studies estimate that replacing fossil fuel heating systems with heat pumps—which include both aerothermal and geothermal technologies—could reduce household emissions by up to 70–80%. By 2022, approximately 20 million heat pumps had been installed across Europe [

3], helping to displace emissions-intensive natural gas and oil heating systems. According to the European Heat Pump Association (EHPA), these installations are already saving about 50 million tons of CO₂ annually [

4]. As part of the European Green Deal, the EU aims to accelerate this transition, with projections suggesting that heat pumps could supply up to 40% of Europe’s residential heating demand by 2030 [

5]. This large-scale shift is critical for achieving the EU’s net-zero emissions target by 2050, as heat pumps not only reduce direct emissions but also operate more efficiently when paired with renewable electricity sources.

In this context, intelligent HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) systems for residential buildings have become a cornerstone of modern energy-efficient architecture, driven by the growing need for sustainability, occupant comfort, and operational optimization. These systems integrate advanced control techniques—such as model predictive control, fuzzy logic, and adaptive algorithms—to dynamically regulate temperature, humidity, and air quality while minimizing energy consumption. Their applications extend beyond basic climate control, encompassing smart zoning, demand-response strategies, and integration with renewable energy sources, which collectively enhance system resilience and cost-effectiveness. Artificial intelligence methods, including machine learning and neural networks, play a pivotal role in predictive maintenance, fault detection, and real-time optimization, enabling HVAC systems to learn from historical data and adapt to changing environmental conditions. By leveraging these technologies, intelligent HVAC solutions not only reduce carbon footprints but also improve user experience through personalized comfort settings, marking a significant advancement in residential building automation.

This systematic review synthesizes findings from 78 sources examining intelligent HVAC systems for residential buildings, with emphasis on control techniques, applications, and artificial intelligence methods. The included studies span simulation-based investigations, field trials, laboratory experiments, and systematic reviews, covering diverse geographic locations and building types.

The primary objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of advanced HVAC control strategies for residential buildings, with a particular emphasis on AI-driven approaches such as Model Predictive Control, Deep Reinforcement Learning, and neural network-based methods [

11]. By analysing recent developments, comparing performance metrics, and identifying research gaps, this paper aims to support the design and implementation of intelligent, energy-efficient, and occupant-centric HVAC systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology adopted for the systematic review, including selection criteria and classification framework.

Section 3 provides an overview of conventional HVAC control strategies and their limitations.

Section 4 discusses advanced control techniques, focusing on AI-based methods and hybrid approaches.

Section 5 examines practical applications, integration with IoT and smart home technologies, and case studies from recent literature.

Section 6 identifies key challenges, research gaps, and future directions for intelligent HVAC systems. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings and implications for residential building energy management.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

6]. The methodology was designed to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and rigor in identifying, selecting, and synthesizing relevant studies on intelligent HVAC control strategies for residential buildings.

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed across major scientific databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect, covering publications from January 2010 to December 2025. The search terms combined keywords related to HVAC systems, intelligent control, and artificial intelligence, using Boolean operators to refine results. The primary query included: ("HVAC" OR "Heating Ventilation Air Conditioning") AND ("intelligent control" OR "smart control" OR "AI" OR "machine learning" OR "model predictive control" OR "reinforcement learning") AND ("residential" OR "smart home").

Additional sources were identified through backward and forward citation tracking to ensure comprehensive coverage.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria:

Focus on residential buildings or mixed-use buildings with residential components.

Address intelligent HVAC control strategies, including AI-based methods (e.g., MPC, DRL, neural networks).

Present quantitative or qualitative performance metrics, such as energy savings, thermal comfort, or computational efficiency.

Published in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings between 2010 and 2025.

Written in English.

The exclusion criteria were:

Studies focusing exclusively on commercial or industrial buildings.

Papers addressing hardware design without control strategy analysis.

Articles lacking sufficient methodological detail or performance evaluation.

Non-peer-reviewed sources (e.g., blogs, white papers), conference abstracts, patents, and database records without DOI (Digital Object Identifier).

A weighting has been applied to the first three inclusion criteria for the evaluation of the full text in order to select the studies to be included in the final synthesis, considering 0.33 for each criterion, accepting those records that have obtained an overall score higher than 0.7.

2.3. Study Selection Process

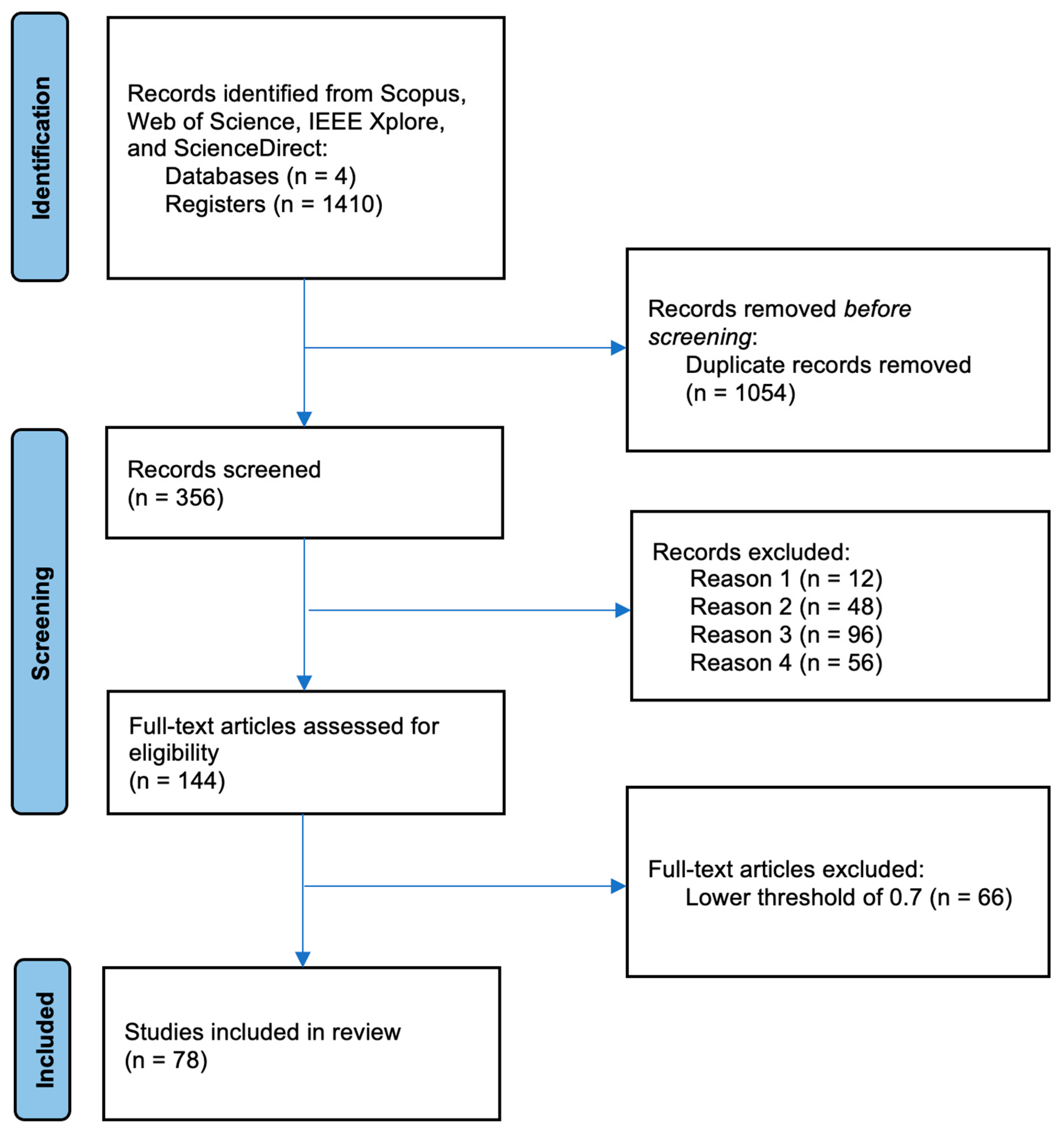

The initial search yielded 1410 records. After removing duplicates, 356 studies remained for screening. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to exclude irrelevant papers, resulting in 144 articles for full-text assessment. Following the application of inclusion/exclusion criteria, 78 studies were retained for final synthesis. The selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1).

2.4. Data Extraction and Classification

Data from the selected studies were extracted using a standardized template, capturing:

Control technique (e.g., MPC, DRL, fuzzy logic, hybrid approaches).

Application context (e.g., thermal comfort optimization, energy efficiency, fault detection).

Performance indicators (e.g., energy savings %, comfort index, computational cost).

Integration aspects (e.g., IoT, renewable energy sources).

The studies were classified into three main categories:

Conventional control strategies and their limitations.

Advanced AI-based methods for HVAC optimization.

Hybrid and integrated approaches combining predictive and adaptive algorithms.

Based on the Elicit assistant [

7], a large language model was used to extract each data column listed below from each paper. The model was provided with the extraction instructions shown for each column.

This language model was employed to extract each data column listed below from the papers. Extraction instructions for each column were provided to the model as shown in

Table 1.

The included studies demonstrate substantial methodological diversity. Simulation-based studies constitute the majority, with several field trials providing real-world validation. The geographic distribution spans North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East, representing diverse climatic conditions from tropical to severe cold regions. Building types predominantly include single-family houses and apartments, though several studies examined commercial or institutional buildings for comparative purposes.

3. Overview of Conventional HVAC Control Strategies and Limitations

Conventional HVAC control strategies have historically relied on simple, rule-based mechanisms and proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers to regulate indoor temperature and air quality. These approaches are widely implemented due to their simplicity, low computational requirements, and ease of integration with existing systems [

8]. Rule-based control typically operates on predefined setpoints and schedules, adjusting heating or cooling output based on fixed thresholds. Similarly, PID controllers modulate system performance by minimizing the error between the desired and actual temperature through proportional, integral, and derivative actions [

9].

While these methods have proven effective in maintaining basic thermal comfort, they exhibit significant limitations in dynamic and complex environments. One major drawback is their inability to adapt to changing conditions such as fluctuating occupancy, variable outdoor temperatures, and intermittent renewable energy supply [

10]. Because conventional controllers rely on static parameters, they cannot anticipate future states or optimize performance under uncertainty. This often results in energy inefficiencies, frequent cycling of equipment, and suboptimal comfort levels.

Another limitation lies in the lack of integration with modern building automation systems and IoT technologies. Traditional controllers are generally designed for isolated operation, without considering interactions between HVAC systems and other building components such as lighting, shading, or energy storage [

11]. Consequently, opportunities for demand-response strategies and grid-interactive optimization remain largely untapped.

Furthermore, conventional control strategies do not incorporate predictive capabilities or learning mechanisms. They are reactive by nature, responding only after deviations occur, which can lead to delayed adjustments and increased energy consumption during peak loads [

12]. In contrast, advanced approaches such as Model Predictive Control (MPC) and machine learning-based algorithms can forecast future conditions and proactively adjust system parameters, significantly improving efficiency and occupant comfort.

In summary, while conventional HVAC control strategies remain prevalent due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness, their inherent limitations—lack of adaptability, predictive capability, and integration—underscore the need for intelligent, AI-driven solutions. These shortcomings have motivated extensive research into advanced control techniques, which are discussed in detail in the following section.

4. Advanced Control Techniques for Intelligent HVAC Systems

The limitations of conventional HVAC control strategies have motivated the development of advanced techniques that leverage predictive algorithms, optimization methods, and artificial intelligence (AI) to improve energy efficiency and occupant comfort. These approaches enable HVAC systems to anticipate future conditions, adapt to dynamic environments, and optimize performance under uncertainty. Among the most prominent methods are Model Predictive Control (MPC), Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), and neural network-based algorithms, which have demonstrated significant potential in residential applications

4.1. Model Predictive Control Approaches

MPC emerges as the most prevalent control technique in intelligent HVAC systems for residential buildings [

13], appearing in approximately 40% of reviewed studies. MPC frameworks demonstrate significant variation in implementation complexity and optimization strategies, making them highly adaptable to diverse residential HVAC applications [

13], [

14], [

15].

Table 2 includes an overview of the main MPC Control approaches and its performance

4.1.1. MPC Framework Variations

The reviewed studies reveal substantial diversity in MPC implementations, ranging from basic centralized approaches to sophisticated hybrid systems integrating artificial intelligence [

37]:

Centralized MPC Systems represent the foundational approach, employing multistep feedback strategies for coordinated control [

16], [

17], [

15]. These systems optimize heating and energy flow among multiple components including heat pumps, baseboards, photovoltaic systems, and battery storage while maintaining thermal comfort constraints. The centralized MPC frameworks demonstrate 13.5% cost reduction against conventional HVAC control systems.

Economic MPC (EMPC) formulations specifically target cost optimization by incorporating time-of-use electricity rates, feed-in tariffs, and demand flexibility indicators [

18]. The EMPC framework demonstrates 7% reduction in total operational electricity costs while achieving flexibility factors ranging from 0.67 to 0.88 compared to conventional PI controllers.

Distributed MPC approaches address scalability challenges by decomposing large optimization problems into smaller sub-problems [

19], [

21]. These systems achieve 11.6% operational cost reduction and 5.5% reduction in electricity consumption while preventing auxiliary heater operation and reducing battery storage usage.

Robust MPC implementations maintain stability and performance specifications under model variations and uncertainty [

22]. These approaches demonstrate superior robustness compared to deterministic MPC while maintaining computational efficiency with solution times around two minutes.

4.1.2. AI Integration with MPC

The integration of artificial intelligence techniques with MPC represents a significant advancement in control sophistication:

Neural Network-Enhanced MPC combines artificial neural networks with traditional MPC frameworks for improved prediction accuracy [

18]. The ANN-MPC [

38] approach achieves computational times under 30 minutes while maintaining temperature control accuracy with RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) values of 0.24-0.27.

Attention-Based LSTM MPC incorporates attention mechanisms with Long Short-Term Memory networks for enhanced adaptability [

26]. The ALSTM-Fast MPC (Attention-based Long Short-Term Memory -Fast MPC) system demonstrates exceptional flexibility in achieving thermal regulation goals while consuming less than 20% of available computational resources.

Deep Neural Network Optimization employs metaheuristic algorithms for MPC parameter tuning [

32]. The Cheetah algorithm-optimized DNN achieves 4% reduction in HVAC energy consumption and 26% improvement in overall grid efficiency while maintaining indoor temperature setpoints within a 0.9°C margin.

4.1.3. Prediction Horizons and Computational Requirements

MPC performance critically depends on prediction horizon selection and computational implementation:

Horizon Length Optimization varies from 10 sampling periods [

35] to 24 hours [

17] depending on building thermal mass and occupancy patterns. The optimal horizon balances prediction accuracy with computational tractability, with longer horizons enabling greater savings but facing diminishing returns beyond certain thresholds [

34].

Computational Efficiency varies significantly across implementations. Standard MPC formulations require substantial computational resources, while neural network-enhanced approaches reduce computational burden while maintaining prediction accuracy. Mixed-integer formulations achieve 9-22% energy cost reduction and up to 22% carbon emission reduction but require sophisticated solvers [

28].

Real-Time Implementation considerations include optimization frequency (typically 15-minute to 1-hour intervals) and solution convergence requirements [

15]. The balance between prediction accuracy and computational feasibility determines practical deployment success.

4.1.4. Performance Outcomes

MPC implementations demonstrate consistent performance advantages across diverse applications:

Energy Savings typically range from 15-20% compared to conventional control methods [

13], with exceptional cases achieving up to 70% during heating seasons [

14]. Economic MPC formulations specifically targeting cost optimization achieve 7-13.5% operational cost reductions while maintaining thermal comfort constraints [

39].

Peak Demand Reduction represents a significant operational benefit, with MPC algorithms achieving 10-35% peak power reduction [

15]. This capability proves particularly valuable for demand response applications and grid integration.

Thermal Comfort Performance maintains temperature tracking errors below 1°F (0.56°C) while achieving energy savings [

14]. The multi-objective optimization inherent in MPC enables explicit trade-off management between energy efficiency and occupant comfort.

4.1.5. Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite demonstrated benefits, MPC implementation faces several practical challenges:

Model Development Complexity requires significant expertise and calibration effort [

18]. Grey-box approaches and data-driven modeling techniques help mitigate this challenge by reducing the need for detailed physical modeling.

Computational Requirements for nonlinear optimization can be substantial, particularly for large-scale applications [

19]. Distributed MPC architectures and model simplification strategies address scalability concerns.

Integration with Existing Systems presents compatibility challenges with legacy building management systems [

40]. Modular architectures and standard communication protocols like BACnet (Building Automation and Control networks) or MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) facilitate integration while minimizing disruption to existing operations.

4.1.6. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

The evolution of MPC approaches continues toward greater intelligence and adaptability:

Hybrid AI-MPC Systems increasingly combine machine learning prediction with optimization-based control [

36]. These approaches leverage the constraint-handling capabilities of MPC while benefiting from the adaptability of artificial intelligence.

Hierarchical Control Architectures decompose complex control problems across multiple levels, enabling coordination between local comfort control and system-wide optimization [

41]. These frameworks achieve 3.95% energy reduction with 8.37% improvement in temperature compliance rates.

Uncertainty Quantification and Robust Design address the stochastic nature of building operations through advanced mathematical formulations [

22]. These approaches ensure reliable performance under varying occupancy patterns, weather conditions, and equipment degradation.

4.1.7. Recommendations for Implementation

Based on the synthesized evidence, successful MPC implementation requires:

Appropriate Model Selection: Choose between centralized, distributed, or hybrid approaches based on system complexity and computational resources

Prediction Horizon Optimization: Balance prediction accuracy with computational feasibility, typically targeting 4-24 hour horizons

AI Integration Strategy: Consider neural network enhancement for improved prediction accuracy and reduced computational burden

Modular Architecture Design: Implement scalable, adaptable frameworks that facilitate integration with existing building systems

Performance Monitoring: Establish baseline comparisons and continuous performance assessment to validate energy savings and comfort maintenance

The evidence demonstrates that MPC represents a mature and effective approach for intelligent HVAC control, with ongoing research addressing implementation challenges and expanding capabilities through artificial intelligence integration.

4.2. Deep Reinforcement Learning Approaches

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has emerged as a leading model-free alternative to MPC, with implementations demonstrating strong adaptability to complex, dynamic environments.

Table 3 includes an overview about the different DRL Approaches.

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has emerged as a leading model-free alternative to traditional control methods in intelligent HVAC systems, demonstrating strong adaptability to complex, dynamic environments without requiring explicit building models [

43], [

44], [

41]. The systematic review reveals that DRL approaches demonstrate significant advantages in adaptability and performance, particularly in complex, dynamic environments where explicit mathematical models are challenging to develop.

4.2.1. Key DRL Algorithms and Implementations

DDPG represents the most successful DRL implementation for HVAC control in the reviewed literature. The algorithm excels in continuous action spaces, making it particularly suitable for HVAC setpoint control.

A 15% reduction in energy costs was achieved compared to the DQN approach proposed by [

43], demonstrating significant

performance results. Comfort violations were also reduced by 79% compared to DQN and by 98% compared to rule-based strategies, according to the same study. Furthermore, the SVR-DNN model combined with the DDPG method improved thermal comfort prediction performance by 20.5% compared to standalone DNN approaches, as reported by [

44].

The

technical implementation of the DDPG method was specifically designed for multi-zone residential HVAC systems, enabling learning through continuous interaction with simulated building environments without requiring prior model knowledge [

43]. This algorithm demonstrated superior performance in handling complex optimization objectives, effectively balancing energy cost reduction with thermal comfort maintenance.

Traditional DQN approaches, while less effective than DDQN in continuous control scenarios, still provide valuable baseline performance for discrete action spaces.

The occupancy-driven LSTM-DDQN framework achieved significant operational improvements: Temperature violation reductions of 9.5-14.6% across three rooms; CO₂ violation reductions of 12.2-17.4%; and HVAC operation time reductions of 10.9-30.4% [

45].

4.2.2. Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning (HDRL)

Advanced DRL implementations leverage hierarchical structures to tackle complex control challenges effectively. For instance, the integration of

Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) and

PPO within a hierarchical framework has demonstrated notable improvements. Specifically, this approach achieved a 3.95% reduction in energy consumption and an 8.37% improvement in temperature compliance rates. Moreover, it enhanced adaptability to dynamic thermal conditions and varying occupancy patterns, as reported by [

41].

In addition

, multi-agent strategies have shown significant potential in distributed energy resource optimization. Hierarchical multi-agent DRL using SAC algorithms enables a layered control structure where lower-level agents focus on balancing comfort and energy efficiency, while upper-level agents optimize the utilization of distributed energy resources. This approach, highlighted by [

47], underscores the growing importance of hierarchical and cooperative learning in achieving scalable and efficient energy management solutions.

4.2.3. Comparative Performance Analysis

The evidence consistently highlights the superiority of DRL over conventional control approaches. In terms of cost reduction, multi-agent DRL achieved a remarkable 51.09% decrease compared to rule-based strategies and a 4.34% improvement over single-agent DRL, as reported by [

46]. Furthermore, field deployment of pre-trained DRL models demonstrated a 30% cost reduction in simulation environments and up to 21% in real-world applications, according to [

42].

Comfort performance results further reinforce DRL’s advantages. DDPG-based control maintained zero temperature violations under optimal conditions, whereas rule-based methods recorded 2,617 minutes of violations [

43]. Additionally, the SVR-DNN combined with DDPG reduced thermal comfort violations by 69.27% compared to rule-based control, as noted by [

44]. These findings underscore DRL’s ability to deliver both economic and comfort benefits in building energy management systems.

Direct algorithm-specific comparisons clearly demonstrate the superiority of DDPG over DQN in continuous control scenarios. DDPG achieved a 15% greater reduction in energy consumption costs compared to DQN, along with a 79% improvement in reducing comfort violations. Furthermore, the average temperature violation under DDPG control was 0°C, whereas DQN recorded an average deviation of 1.00°C, as reported by [

43]. These results highlight DDPG’s effectiveness in optimizing both energy efficiency and occupant comfort in complex HVAC environments.

4.2.4. Implementation Characteristics

Model-free DRL approaches offer a significant advantage by eliminating the need for explicit building models, learning directly through interaction with the environment [

43]. This capability is particularly valuable in scenarios where building physics are complex or poorly characterized, rapid deployment across diverse building types is required, or continuous adaptation to changing conditions is necessary.

Regarding training and deployment considerations, the review indicates that online learning for DRL applications is impractical due to extended training periods and inadequate comfort control during the learning phase. A practical solution involves pre-training on building models prior to deployment; however, creating accurate models for every building introduces cost challenges [

42]. Despite these limitations, well-trained DRL agents exhibit strong generalization and adaptability to unseen environments, with evidence supporting successful deployment across different building configurations and varying user comfort preferences [

43].

4.2.5. Advanced DRL Architectures

The integration of attention mechanisms with LSTM networks significantly enhances DRL performance in building energy management. Attention-LSTM models have achieved impressive forecasting accuracy, with MAPE scores of 3.43% and RMSE scores of 0.0388 for energy prediction, as reported by [

51]. Additionally, the ALSTM-Fast MPC system demonstrated exceptional flexibility and precision in meeting thermal regulation objectives, according to [

26].

Moreover, advanced implementations incorporate ensemble learning techniques alongside DRL to address challenges related to delayed rewards. These approaches leverage both historical and real-time data without depending on highly accurate load forecasting, thereby improving robustness and adaptability in dynamic environments [

47].

4.2.6. Challenges and Limitations

DRL implementations face notable computational challenges, including the need for extensive training episodes to achieve convergence, memory-intensive value storage for complex state spaces, and real-time inference requirements for practical deployment. These factors demand significant computational resources and optimized architectures to ensure efficiency.

Data requirements also play a critical role in successful DRL implementation. High-quality training data, sufficient environmental interaction for learning, and robust handling of sensor noise and system uncertainties are essential to maintain accuracy and reliability in dynamic building environments.

Integration complexity remains a practical barrier during field deployment. Common challenges include control delays between software commands and device responses, requirements for handling software malfunctions, and the need for adaptation to changing comfort ranges and schedules [

42].

Hybrid approaches are gaining traction, combining DRL’s adaptability with the constraint-handling capabilities of traditional control methods such as MPC, where neural networks are employed for prediction within MPC frameworks. Privacy-preserving DRL implementations using federated learning show promise for personalized comfort modeling while maintaining data privacy [

52]. Additionally, edge computing deployments leveraging FPGAs enable low-latency DRL inference, achieving superior performance with inference times as low as 0.002574 seconds compared to traditional CPU and GPU implementations [

53].

In conclusion, Deep Reinforcement Learning represents a major advancement in intelligent HVAC control, consistently outperforming traditional methods in energy efficiency and thermal comfort. Evidence identifies DDPG as the most effective algorithm for continuous control applications, while hierarchical and multi-agent approaches show strong potential for complex, multi-zone systems. Despite challenges related to training and integration, DRL’s model-free nature and adaptive capabilities position it as a leading technology for next-generation HVAC control. The field is evolving toward hybrid solutions that merge DRL’s flexibility with traditional reliability, supported by innovations in edge computing and privacy-preserving learning techniques that address practical deployment concerns.

4.3. Neural Network Architectures

Various neural network architectures serve distinct roles in intelligent HVAC systems, from load prediction to direct control.

Table 4 includes an overview about the different Deep Reinforcement Learning Approaches.

Neural network architectures serve critical roles in intelligent HVAC systems, functioning primarily in load prediction, thermal comfort modeling, and direct control applications. The systematic review reveals diverse implementations ranging from simple feedforward networks to sophisticated fusion models combining multiple architectures.

4.3.1. Key Neural Network Types and Applications

LSTM networks are the most widely used neural architecture for HVAC applications, particularly excelling in temperature prediction and energy forecasting tasks. Their ability to capture temporal dependencies makes them highly effective for dynamic building environments.

LSTM-based models have demonstrated outstanding accuracy in predictive tasks. For temperature prediction, results include a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.0495 and an R² score of 0.9937 [

54]. In energy forecasting, models achieved a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 3.43% and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.0388 (Gobinda Chandra Sarker et al., 2025), [

51]. The optimal prediction horizon was identified as four hours, yielding MAE of 0.0495, MAPE of 0.003, RMSE of 0.0627, and R² of 0.9937 [

54].

Practical applications of LSTM networks in HVAC systems include heat load prediction within MPC frameworks [

28], occupancy-driven HVAC control integrated with DDQN [

45], and multi-step indoor temperature forecasting [

54]. These implementations highlight LSTM’s versatility and effectiveness in optimizing energy efficiency and maintaining thermal comfort.

CNN architectures enable spatial feature extraction from time-series data through innovative transformation techniques. One notable advancement is the CNN-BiLSTM (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory) fusion architecture, which combines CNN and Bidirectional LSTM networks to deliver superior performance through complementary feature extraction capabilities [

54].

CNN components extract spatial features by applying Gramian Angular Field transformation, converting time-series data into two-dimensional images to capture both global and local change trends. Meanwhile, BiLSTM components process temporal dependencies bidirectionally, leveraging forward and backward LSTM sub-networks for enhanced sequence modeling. This fusion approach achieves significant performance gains, including an 83.2% reduction in MAE, a 68.7% reduction in MAPE, and a 69.7% reduction in RMSE compared to standalone models.

Despite its accuracy, the CNN-BiLSTM architecture introduces computational trade-offs. Training time is the longest among compared models at 98 minutes, while prediction time remains efficient at approximately one second. The slower training process is offset by the highest accuracy achieved, making this architecture a compelling choice for advanced HVAC forecasting applications [

54].

ALSTM Networks enhance feature extraction capabilities and prediction accuracy through the integration of attention mechanisms [

51]. These models are applied to energy usage forecasting with 10-minute-ahead predictions, achieving strong performance metrics with a MAPE of 3.4310% and an RMSE of 0.0388. The architecture typically consists of two LSTM layers combined with two fully connected layers, enabling precise short-term energy demand forecasting.

ALSTM-FMPC represents an advanced integration that combines attention mechanisms with MPC frameworks [

26]. This approach offers responsive adaptation to changing temperature setpoints and provides dynamic adaptability, allowing systems to anticipate and efficiently respond to environmental changes. Performance evaluations consistently show that ALSTM-FMPC outperforms traditional LSTM and MPC controllers, making it a highly effective solution for real-time HVAC optimization.

RBFNN have been applied in model-based predictive control strategies, delivering significant energy savings during occupied periods [

29]. These networks enable real-time control with hourly time steps, making them suitable for dynamic HVAC optimization.

GRU are employed for energy prediction tasks and enhanced through metaheuristic optimization techniques [

55]. When combined with the Gorilla Troop Optimizer (GTO), GRU models achieved a 14.5% reduction in operating costs, outperforming traditional architectures such as RNN, CNN, and LSTM.

Deep Autoencoder Networks play a critical role in system identification using the Koopman operator [

56]. Their primary purpose is to linearize nonlinear thermal comfort dynamics, achieving exceptional accuracy with a median error below 0.5% and a maximum error of only 2.5%.

Wavelet Neural Networks are utilized for load prediction tasks, often integrated with ant colony optimization techniques. These models deliver high predictive accuracy, with R² values of 0.9714 for heating load and 0.9783 for cooling load, while reducing errors by 66–85% compared to traditional methods [

57].

4.3.2. Integration with Control Frameworks

Neural networks are increasingly used as prediction engines within MPC frameworks, combining the interpretability of MPC with the learning capabilities of neural networks.

EMPC with ANN employs black-box models to represent building and heating system dynamics, achieving computational efficiency with optimization times under 30 minutes and delivering a 7% reduction in operational costs [

18]. Similarly,

Mixed-Integer MPC with LSTM has been applied to variable-speed heat pump control, using an architecture that includes an LSTM layer followed by three fully connected layers. This approach has demonstrated energy cost reductions of 9–22% and up to 22% reductions in carbon emissions [

28].

Deep Reinforcement Learning Integration further enhances predictive and control capabilities within HVAC systems. The

SVR-DNN with DDPG approach combines Support Vector Regression with Deep Neural Networks to improve thermal comfort prediction by 20.5% compared to standalone DNN models, while also achieving a 3.52% reduction in energy consumption and a 64.37% reduction in comfort violations compared to DQN [

44]. Additionally, Hierarchical DRL Architectures leverage multi-level neural network structures to address complex control challenges. Implementations using algorithms such as TD3 and PPO have achieved a 3.95% reduction in energy consumption and an 8.37% improvement in temperature compliance [

41].

4.3.3. Optimization and Enhancement Techniques

Metaheuristic Optimization techniques are increasingly applied to enhance neural network parameter selection for HVAC applications.

The Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) has been used for CNN-BiLSTM hyperparameter optimization, delivering improved prediction accuracy and superior feature extraction capabilities [

54]. Similarly, the

Cheetah Algorithm focuses on metaheuristic optimization for DNN architecture design, aiming to determine the optimal layer and neuron configuration for power and occupancy estimation. Its primary objective is to minimize RMSE in building-to-grid integration applications [

32].

Federated Learning Approaches address privacy concerns while maintaining strong predictive performance through decentralized learning architectures.

Privacy-Preserving Neural Networks employ gradient-boosted regressors with client-level personalization, achieving significant improvements in R² scores—from initial ranges of -0.007 to 0.076, up to 0.505 after personalization [

52]. These architectures enable real-time model adaptation without compromising data privacy, making them highly suitable for scalable and secure HVAC control systems.

4.3.4. Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Accuracy Metrics Across Architectures highlight significant differences in predictive performance for temperature and load forecasting tasks. For temperature prediction, the CNN-BiLSTM fusion model achieved exceptional accuracy with MAE of 0.0334, MAPE of 0.0015, RMSE of 0.0428, and an R² of 0.9994 [

54]. In comparison, standalone LSTM models recorded MAE of 0.1276, MAPE of 0.0062, RMSE of 0.1654, and R² of 0.9912, while BiLSTM models achieved MAE of 0.1115, MAPE of 0.0048, RMSE of 0.1412, and R² of 0.9936. For load prediction, the I-ACO-WNN (Improved Ant Colony Optimization - Wavelet Neural Network.) architecture delivered R² values of 0.9714 for heating and 0.9783 for cooling, with error reductions of 66.01% in RMSE, 82.44% in MAE, and 81.21% in MAPE for heating loads.

Computational Efficiency Considerations reveal trade-offs between training and inference times across different architectures. SVM (Support Vector Machine) models require 26 minutes for training and 0.1 seconds for prediction, while CNN models take 53 minutes for training and 0.3 seconds for prediction. LSTM models need 69 minutes for training and 1 second for inference, BiLSTM models require 87 minutes for training and 1 second for inference, and CNN-BiLSTM models have the longest training time at 98 minutes, with prediction times remaining at 1 second [

54]. Advanced Edge Computing Deployment using the HLS4ML framework enables FPGA-based acceleration, achieving inference speeds of 0.002574 seconds compared to 0.289659 seconds on CPU and 0.127011 seconds on GPU. Additionally, model compression reduces inference size from 70.55 KB to 27.69 KB and weight size from 13.50 KB to 1.19 KB [

53].

4.3.5. Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Data Requirements and Quality play a critical role in the performance of HVAC prediction and control models. Minimum dataset size varies depending on architecture complexity, but high-quality real-world data is essential for achieving accurate results [

58]. Optimal temporal resolution for predictive accuracy has been identified within 4-hour prediction windows [

54]. Effective feature engineering further enhances model performance through input normalization using min-max scaling [

32], feature selection techniques such as correlation analysis and Granger causality testing [

54], and multi-modal integration of temperature, humidity, occupancy, and weather data.

Scalability and Deployment Considerations introduce additional challenges for real-world implementation. While single-zone applications maintain manageable computational requirements, multi-zone systems exhibit exponential complexity growth, necessitating distributed approaches [

44]. Deployment strategies must balance trade-offs between cloud-based solutions and edge computing, considering latency and resource constraints. Integration with legacy systems requires adherence to standard communication protocols such as BACnet and MQTT, while real-time constraints demand inference times that meet control system requirements. Furthermore, periodic model retraining is necessary to adapt to changing environmental conditions and user preferences.

4.3.6. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

Advanced Architectures are emerging as promising directions for intelligent HVAC systems. Transformer networks, although not extensively explored in the current review, show potential for HVAC applications due to their attention-based mechanisms. Generative AI Integration is another innovative approach, with recent implementations demonstrating up to 47.92% energy savings and 26.36% improvements in thermal comfort through GPT-4-based control systems that incorporate real-time feedback [

59]. Additionally, Physics-Informed Neural Networks combine physical constraints with neural learning, offering improved interpretability and enhanced performance for complex building environments.

In conclusion, neural network architectures in intelligent HVAC systems deliver substantial performance improvements over traditional control methods, with fusion models achieving the highest accuracy at the cost of increased computational complexity. The integration of attention mechanisms, metaheuristic optimization, and federated learning approaches addresses critical challenges related to accuracy, efficiency, and privacy. Future research should prioritize transformer architectures, generative AI integration, and physics-informed approaches to further enhance predictive performance while ensuring practical deployability.

4.4. Hybrid and Metaheuristic Approaches

Hybrid control strategies combine multiple techniques to leverage complementary strengths. These approaches represent a sophisticated evolution in intelligent HVAC control, combining multiple techniques to leverage complementary strengths and overcome individual limitations. This analysis examines the current state of these approaches based on systematic review findings from 80 sources examining intelligent HVAC systems for residential buildings.

4.4.1. Overview of Hybrid Control Strategies

Hybrid control strategies combine multiple techniques to leverage complementary strengths, addressing the limitations of individual control methods. The report identifies several key hybrid approaches that demonstrate superior performance compared to single-method implementations.

Table 5 includes an overview about the Key Hybrid and Metaheuristic Approaches.

4.4.2. Neural Network-Enhanced MPC Systems

The integration of artificial neural networks with MPC represents one of the most successful hybrid approaches. Reference [

18] demonstrated an ANN-MPC system that achieved 7% reduction in total operational electricity costs while maintaining good temperature control accuracy with RMSE of 0.24-0.27. The system successfully integrated weather forecasting and building dynamics prediction, with computational times under 30 minutes making it practical for real-time applications.

Reference [

28] further advanced this approach by combining LSTM neural networks with mixed-integer MPC for variable-speed heat pump control. Their system achieved 9-22% reduction in electricity costs and up to 22% reduction in carbon emissions compared to existing control policies. The LSTM network provided accurate heat load predictions while the MPC framework optimized compressor speed and thermal energy storage operation.

4.4.3. Advanced Deep Learning Hybrid Systems

Reference [

44] developed a sophisticated hybrid system combining SVR, DNN, and DDPG algorithms. This approach improved thermal comfort prediction performance by 20.5% compared to standalone DNN approaches while reducing energy consumption by 3.52% and comfort violations by 64.37% compared to DQN methods.

On the other hand, [

26] introduced the ALSTM-Fast MPC system, which combines attention mechanisms with LSTM networks and fast MPC optimization. This system demonstrated exceptional adaptability to changing thermal dynamics and occupancy patterns, consistently outperforming traditional MPC and LSTM controllers in thermal regulation performance.

Recent research has explored hybrid approaches that combine machine learning algorithms with intelligent control methods to enhance energy efficiency in HVAC systems. A notable example is the integration of XGBoost with Deep Q-Network (XGB-DQN), applied to modeling occupant behavior. This approach enables accurate prediction of usage patterns and dynamic adjustment of air conditioning operation, achieving a 24.7% reduction in AC-related energy consumption [

61]. The combination of robust predictive models with deep reinforcement learning provides an adaptive solution to the variability of human behavior.

Similarly, ISPC, based on ANN and PSO, has been implemented in supervisory control strategies for HVAC. This system not only improves real-time decision-making but also optimizes overall building performance, resulting in estimated annual savings of €100 [

62]. The integration of ANN and PSO allows for precise thermal demand prediction and efficient resource optimization.

4.4.4. Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms

Metaheuristic algorithms demonstrate significant effectiveness in parameter tuning and global optimization for HVAC systems, addressing the challenge of finding optimal solutions in complex, multi-dimensional search spaces.

Reference [

32] employed the Cheetah Optimization Algorithm (COA) to optimize deep neural network architecture for Building-to-Grid (B2G) integration. The system achieved 4% reduction in HVAC energy consumption, 12% decrease in peak generator demand, and 26% improvement in overall grid efficiency. The Cheetah algorithm specifically optimized the number of layers and neurons to minimize RMSE in power and occupancy estimation.

Reference [

63] conducted a comprehensive evaluation of 46 swarm intelligence algorithms for residential building optimization. The Bald Eagle Search (BES) algorithm achieved the best performance with mean energy costs of Rs. 8.85 compared to Rs. 12.98 for the worst-performing algorithm. The study demonstrated cost savings of approximately 34% compared to existing models and 57% compared to conventional models across five Indian metropolitan cities.

Reference [

64] included a simulation development about rule-based predictive control for Single-family houses in Ontario, Canada.

Finally, reference [

57] developed an I-ACO-WNN model for building energy load prediction, achieving significant performance enhancements: for Heating Load (HL), the model reached an R² of 0.9714 with RMSE reduced by 66.01% and MAE reduced by 82.44%; for Cooling Load (CL), it achieved an R² of 0.9783 with RMSE reduced by 73.28% and MAE reduced by 84.82%.

4.4.5. Fuzzy Logic Integration

Reference [

68] includes a systematic review about Modelling Techniques Used in Building HVAC Control Systems including fuzzy logic approaches.

Reference [

69] included a case study about fuzzy logic adaptive control for commercial buildings.

Reference [

65] demonstrated the effectiveness of Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) for HVAC performance prediction. The system achieved significant efficiency improvements, with ventilation efficiency increasing from 75% to 93% and heat load efficiency from 79% to 97%. The RMSE error of 0.65 indicated minimal deviation from actual values, highlighting the precision of the hybrid model.

References [

66] and [

67] introduced the Human Building Interaction for Thermal Comfort (HBI-TC) framework, which integrates fuzzy logic with participatory sensing. This system delivered notable results, including a 39% reduction in daily average airflow, an improvement in user satisfaction from 4.7 to 8.4 on a 10-point scale, and a 12.08% reduction in average daily airflows compared to legacy systems.

4.4.6. Multi-Agent and Hierarchical Approaches

Reference [

41] proposed a HDRL framework that integrates TD3 and PPO algorithms, achieving a 3.95% reduction in energy consumption, an 8.37% improvement in temperature compliance rates, and enhanced adaptability to dynamic indoor occupancy and outdoor weather conditions. Similarly, [

47] implemented a hierarchical multi-agent DRL approach leveraging SAC algorithms combined with ensemble learning, which resulted in average reductions of 2.79% in peak power demand and 3.92% in overall energy consumption while maintaining occupant comfort.

4.4.7. Federated Learning and Privacy-Preserving Approaches

Reference [

52] introduced a personalized federated learning framework combining gradient-boosted regressors with real-time occupant feedback. The system achieved substantial improvements in predictive accuracy while maintaining privacy through decentralized processing. R² scores improved from -0.007-0.076 to up to 0.505 after client-side fine-tuning.

4.4.8. Implementation Considerations and Challenges

Hybrid approaches often face

computational complexity challenges, as they involve a larger number of decision variables compared to single-method implementations. Sebastian [

19] reported that this complexity results in prolonged computational times for online optimization, making real-time control difficult. To mitigate these issues, distributed MPC strategies have been proposed, enabling parallel computation and reducing latency in dynamic environments.

Another critical aspect is

integration challenges, particularly when embedding advanced control algorithms into local HVAC controllers. Reference [

70] highlighted that legacy systems often lack the processing capacity required for sophisticated optimization techniques. A promising solution lies in modular architectures based on the MQTT protocol, which provide scalability and interoperability across diverse central heating systems, facilitating communication between distributed components.

Finally,

data requirements represent a significant barrier to the effective deployment of hybrid systems. These approaches demand extensive, high-quality data streams to ensure accurate predictions and optimal performance. Reference [

58] emphasized that AI-driven control strategies rely on massive quantities of real-world data, which remains scarce in the building energy sector. Addressing this limitation requires investment in robust sensor networks, advanced data preprocessing, and standardized data collection protocols to guarantee reliability and consistency.

4.4.9. Future Directions and Recommendations

Recent advances in intelligent HVAC control reveal several

emerging trends that are shaping the future of the field. One of the most promising directions is the integration of generative AI, as demonstrated by [

59], who achieved 47.92% energy savings and a 26.36% improvement in thermal comfort in real-world deployments. Another significant advancement is edge computing, highlighted by [

53], who showcased the HLS4ML (High-Level Synthesis for Machine Learning) framework for deploying optimized neural networks on FPGAs (Field-Programmable Gate Array), achieving inference times as low as 0.002574 seconds. Additionally, human-in-the-loop systems have gained traction, with [

48] developing frameworks that balance automated optimization with real-time occupant preferences, reinforcing the importance of user-centric design in intelligent control strategies.

To ensure successful deployment of hybrid and metaheuristic approaches, several implementation recommendations have emerged from recent studies. It is advisable to start with proven combinations such as ANN-MPC and fuzzy-genetic algorithms, which have consistently demonstrated robust performance across diverse applications. Practitioners should also consider building characteristics, as metaheuristic optimization techniques show particular promise for complex, multi-zone buildings with variable occupancy patterns. Furthermore, prioritizing modularity is essential, since modular architectures enable incremental deployment and simplify maintenance of hybrid systems. Finally, attention must be given to data quality, requiring investment in reliable sensor networks and advanced data preprocessing to meet the increased data demands of hybrid approaches.

In conclusion, hybrid and metaheuristic approaches represent the current frontier in intelligent HVAC control, offering superior performance through the strategic combination of complementary techniques. Evidence strongly supports their adoption for residential and commercial applications, particularly in complex buildings where single-method solutions prove insufficient. While successful implementation demands careful attention to computational complexity, data quality, and system integration challenges, the potential benefits in energy savings, comfort enhancement, and operational efficiency justify the added complexity. The field is rapidly evolving toward more sophisticated combinations involving generative AI, federated learning, and edge computing, suggesting that hybrid approaches will continue to dominate high-performance HVAC control applications. Future research should focus on standardizing integration frameworks and developing automated methods for selecting optimal technique combinations based on building characteristics and performance requirements.

4.5. Fuzzy Logic and Rule-Based Systems

Fuzzy logic control provides interpretable decision-making for thermal comfort optimization, particularly valuable when explicit mathematical models are unavailable. The report identifies fuzzy logic as a key approach for handling uncertainties in HVAC control systems while maintaining transparency in decision-making processes.

4.6. Key Methodologies and Frameworks

One of the most extensively documented fuzzy logic approaches is the Human Building Interaction for Thermal Comfort (HBI-TC) framework, developed by [

66]. This system employs fuzzy predictive models to learn occupant comfort profiles online and integrate them into zone-level control. The framework enables occupants to communicate their preferences for indoor thermal conditions through a user interface, leveraging a participatory sensing approach. The HBI-TC controller operates as a complementary control strategy that relies on an additional temperature sensor network to receive environmental feedback. Its control algorithm follows a proportional approach designed to minimize the sum of deviations from preferred temperatures across all rooms within a zone.

Another significant contribution is the ANFIS, applied by [

65] for HVAC performance prediction. This hybrid ANFIS model achieved remarkable efficiency improvements, with ventilation efficiency reaching 93% compared to 75% in pre-COVID-19 conditions, and heat load efficiency increasing to 97% from a previous 79%. Furthermore, the system demonstrated high predictive accuracy, achieving an RMSE of 0.65, which indicates minimal deviation from actual values and underscores the precision of the model.

Finally, fuzzy pattern recognition for personalized control was introduced by [

67] to extend the capabilities of fuzzy logic in HVAC systems. Their approach models personalized thermal preferences by continuously maintaining average zone temperatures close to user-defined comfort levels. This is accomplished through real-time determination of set points using an optimization problem that transforms traditional multi-objective optimization into a scalar optimization framework, thereby simplifying computation while ensuring occupant comfort.

4.6.1. Performance Outcomes

In terms of energy efficiency results, fuzzy logic implementations have demonstrated substantial improvements in HVAC performance. The HBI-TC framework, developed by [

66], achieved a 39% reduction in daily average airflow when conditioning rooms at occupants’ desired temperatures. Since airflow is directly proportional to the energy consumption of HVAC system components, this reduction translates into significant energy savings. Similarly, the ANFIS implementation by [

65] showed remarkable gains, with ventilation efficiency improving from 75% to 93% and heat load efficiency increasing from 79% to 97%. Furthermore, a comprehensive review by [

58] indicates that fuzzy logic-based systems typically achieve energy savings ranging between 21.81% and 44.36%, reinforcing the effectiveness of these approaches.

Regarding comfort improvements, user satisfaction metrics reveal notable enhancements under fuzzy logic control strategies. The HBI-TC framework improved average user comfort ratings from 4.7 to 8.4 out of 10 possible points during the post-training period, as reported by [

66]. Additionally, airflow optimization within the HBI-desired mode resulted in a 26% decrease compared to predefined temperature control modes, further contributing to improved thermal comfort and system efficiency.

Finally, membership function optimization emerged as a critical design consideration in fuzzy logic controllers. The ANFIS study conducted by [

65] revealed that trapezoidal membership functions exhibited the lowest error rate among evaluated types, providing valuable guidance for future controller development and optimization strategies.

4.6.2. Technical Implementation Details

The system architecture of the HBI-TC framework is designed to integrate seamlessly into existing centrally controlled HVAC systems with minimal intrusion. Its implementation includes a sensor network composed of 55 HBI-TC sensor boxes equipped with Arduino Black Widow microcontrollers featuring integrated 802.11 WiFi communication capabilities, as reported by [

66]. Communication between the server and the Building Management System (BMS) occurs through a BACnet workstation, enabling dynamic real-time adjustment of system set points. The control logic relies on a proportional algorithm executed at 30-minute intervals, a timing strategy derived from observations of HVAC system reaction times.

In addition to architectural considerations, data requirements and processing play a critical role in the performance of fuzzy logic systems. These systems depend on diverse and high-quality data inputs, including environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, and air quality measurements, which are essential for ANFIS applications, as noted by [

65]. Occupant feedback, collected through real-time thermal sensation votes and preference data, is fundamental for personalized control strategies, as demonstrated by [

66]. Furthermore, system response data, encompassing HVAC operational parameters and energy consumption metrics, is required to optimize performance and ensure accurate predictive modeling.

4.6.3. Implementation Challenges and Limitations

Several technical barriers have been identified that limit the practical implementation of fuzzy logic-based HVAC control systems. One major challenge is retrofitting complexity, as many advanced control algorithms require modifications to existing HVAC components, making deployment difficult in real-world scenarios [

66]. Another critical issue is user interface design; poorly designed interfaces can lead to user fatigue and degrade data quality, emphasizing the need for careful attention to usability and user experience. Scalability also presents limitations, as the HBI-TC framework is better suited for permanently occupied offices where thermal comfort profiles can be established, posing challenges for open-plan office environments [

66].

In addition to these technical constraints, several operational considerations must be addressed to ensure system effectiveness. Proper tuning of proportional coefficients is essential to avoid excessive oscillations that could result in unnecessary energy consumption [

66]. Furthermore, the development of policies to prevent users from gaming the control strategies remain an ongoing research challenge. Finally, sensor optimization is crucial, as the placement of sensors within zones requires careful planning to guarantee accurate data collection and effective system performance [

66].

4.6.4. Comparative Performance Analysis

Fuzzy logic systems offer several advantages over conventional HVAC control strategies, making them an attractive alternative in intelligent building management. One key benefit is

interpretability, as fuzzy logic provides transparent decision-making processes that building operators can easily understand and modify, unlike black-box machine learning approaches [

71]. Another important advantage is

uncertainty handling, since fuzzy controllers employ linguistic rules and fuzzy sets to manage uncertainties without requiring explicit mathematical models, as highlighted by [

72]. Finally, fuzzy logic enables

real-time adaptation, allowing systems to respond dynamically to changing occupant preferences and environmental conditions without the need for extensive retraining, which is often required in traditional AI-based approaches.

4.6.5. Future Research Directions

Several recommended developments have been identified as priorities for advancing fuzzy logic-based HVAC control systems. One critical area is the application of these strategies in open-plan office environments, which requires a comprehensive study of microclimates and the development of novel approaches for personalized thermal-driven control [

66]. Another important research direction involves occupancy integration, focusing on detecting occupancy patterns and incorporating this information into operational loops to enhance system responsiveness. Additionally, further investigation into advanced membership functions is necessary to determine optimal types and their applicability across different building contexts.

In terms of emerging applications, the report suggests expanding fuzzy logic systems to address new operational challenges. For instance, integrating health compliance measures into HVAC control has become increasingly relevant, as demonstrated by the ANFIS implementation that achieved improved ventilation rates in response to COVID-19 guidelines [

65]. Another promising area is multi-zone coordination, which involves developing fuzzy logic approaches capable of managing thermal comfort and energy efficiency across multiple building zones simultaneously.

Conclusions and recommendations emphasize that fuzzy logic and rule-based systems represent a mature and effective approach for intelligent HVAC control, particularly in scenarios where interpretability and user acceptance are critical. Evidence consistently demonstrates energy savings in the range of 20–40%, alongside significant improvements in occupant comfort. However, successful implementation requires careful attention to user interface design, system integration challenges, and ongoing maintenance requirements. This technology is particularly well-suited for retrofit applications, where existing building management systems need enhancement without complete replacement. Future developments should focus on addressing scalability challenges and expanding applications to more diverse building types and operational scenarios.

5. Comparative Analysis

This section provides a comparative evaluation of the intelligent HVAC control strategies discussed in previous sections, focusing on their performance in terms of energy efficiency, thermal comfort, computational complexity, and implementation feasibility in residential buildings.

5.1. HVAC Applications and System Integration

5.1.1. Functions Optimized

The reviewed studies address multiple HVAC functions with varying emphasis across different control objectives.

Table 6 summarizes the main functions optimized, the number of studies focusing on each, primary performance metrics, and typical savings ranges reported in the literature.

Multi-zone control presents particular challenges due to the complexity of thermal dynamics and interaction between zones. Multi-zone residential HVAC systems require consideration of natural air flow between floors and varying occupancy patterns across zones [

57]. DDPG-based control achieves 98% reduction in comfort violations compared to rule-based strategies in multi-zone applications [

43].

5.1.2. System Types and Components

Intelligent control has been applied across diverse HVAC system configurations.

Table 7 summarizes the main system types, control components, integration levels, and representative studies.

Variable-speed heat pumps demonstrate particular promise for intelligent control, with MPC achieving 9-22% energy cost reduction and up to 22% carbon emission reduction compared to conventional control policies [

28]. The ability to modulate compressor speed enables finer control granularity than traditional on-off systems.

5.1.3. Integration with Building Systems

Advanced control strategies increasingly integrate HVAC with other building systems for holistic optimization.

Table 8 summarizes the main integration types, combined systems, benefits, and representative implementation examples.

Building thermal mass serves as a form of thermal energy storage, enabling load shifting and increased renewable self-consumption. By strategically overheating buildings during periods of renewable availability, solar fractions can increase from 11% to 61% in single-family houses with heat pump systems [

74].

5.2. Performance Outcomes

5.2.1. Energy Savings

Energy savings vary substantially across studies, influenced by baseline conditions, control method sophistication, and building characteristics.

Table 9 summarizes typical energy savings, peak reduction, and cost savings reported for different control categories.

Field trial results demonstrate MPC achieving 20% energy savings during transition seasons and up to 70% during heating seasons compared to rule-based schedules, with peak power reduction exceeding 10% [

14]. These results were obtained in a mid-size commercial building with direct digital control system integration.

The comprehensive review by [

58] reports average energy savings between 21.81% and 44.36% across AI-based building control systems from 1993 to 2020. However, performance varies significantly based on building characteristics, with the highest savings observed in older buildings and households with high vacancy times [

78].

5.2.2. Thermal Comfort Performance

Comfort improvements represent a critical outcome metric, often in tension with energy reduction objectives.

Table 10 summarizes thermal comfort performance indicators and associated control methods.

The trade-off between energy efficiency and comfort is explicitly managed through penalty factors and multi-objective optimization. MPC frameworks incorporating comfort constraints achieve temperature tracking errors less than 1°F (0.56°C) while maintaining energy savings [

14]. The SVR-DNN model achieves 20.5% improvement in thermal comfort prediction compared to standalone DNN, enabling more precise control targeting [

44].

5.2.3. Operational and Environmental Benefits

Beyond energy and comfort, intelligent HVAC systems provide operational advantages and environmental benefits.

Table 11 summarizes key outcomes.

Generative AI-based control demonstrates exceptional real-world performance, achieving up to 47.92% energy reduction and 26.36% comfort improvement in an operational office setting compared to baseline operation [

59]. Regression analysis confirmed robustness against confounding variables including outdoor conditions and occupancy levels.

5.3. Input Data Requirements

Effective intelligent HVAC control depends on diverse data streams spanning environmental conditions, occupancy patterns, and system performance. Accurate and timely data acquisition is critical for predictive algorithms, optimization routines, and adaptive control strategies.

5.3.1. Environmental and Building Data

Weather forecasting integration enables proactive control strategies by anticipating outdoor conditions and adjusting HVAC operation accordingly. Ten-year datasets support solar radiation forecasting for MPC applications [

18], while real-time weather API integration provides current condition updates [

51]. Prediction accuracy typically degrades with forecast horizon, with optimal performance achieved within 4-hour prediction windows [

54].

Table 12 summarizes key environmental and building data requirements.

5.3.2. Occupancy Information

Occupancy data significantly enhances control effectiveness, with occupancy-aware approaches achieving 19–45% energy savings compared to conventional control.

Table 13 compares occupancy detection methods in terms of accuracy, privacy, and implementation complexity.

Change-point analysis of CO₂ concentration fluctuations provides a privacy-preserving approach to occupancy estimation, achieving precision and recall rates around 0.7 and 0.6 respectively [

45]. While these accuracy levels introduce some uncertainty, the method ensures prompt ventilation during high-concentration periods while minimizing unnecessary HVAC operation during vacant periods.

5.3.3. Energy and Pricing Data

Dynamic electricity pricing enables economic optimization beyond simple energy minimization.

Table 14 summarizes common pricing schemes, data requirements, optimization horizons, and typical savings.

Integration of energy storage systems (battery, thermal mass) requires coordination between HVAC control and energy management. MPC-based home energy management systems simultaneously optimize zone-based heating and energy flow among PV systems, batteries, and grid connections [

17].

5.4. System Architecture and Implementation

5.4.1. Hardware Infrastructure

Implementation requirements vary significantly across control methodologies. Self-powered wireless sensors address deployment challenges in existing buildings, using energy harvesting from photovoltaic cells or thermoelectric generators to eliminate battery replacement requirements [

29]. IEEE 802.15.4 transceivers enable low-power communication for distributed sensor networks.

Table 15 summarizes hardware, computing, and communication requirements.

5.4.2. Software Platforms and Frameworks

Real-time implementation requirements vary by control method. MPC optimization typically requires computational times under

30 minutes for practical building applications [

18], while DRL inference can execute in milliseconds after offline training. The

HLS4ML framework enables deployment of optimized neural network models on FPGAs, achieving substantial gains in hardware efficiency and inference speed for resource-constrained environments [

53].

Table 16 summarizes software platforms.

5.4.3. Communication and Integration

Integration with existing building management systems represents a significant implementation consideration. BACnet protocol enables communication with standard building automation systems [

31], while MQTT provides lightweight messaging for IoT sensor networks [

70]. Cloud-based architectures enable remote monitoring and control but introduce latency and reliability considerations.

Table 17 summarizes communication protocols.

6. Synthesis of Findings

6.1. Explaining Variation in Energy Savings

The wide range of reported energy savings (5% to 70%) reflects systematic differences in study conditions rather than methodological inconsistency.

Studies in heating-dominated climates with older, poorly insulated buildings consistently report higher savings. Field trials during heating seasons demonstrate 70% savings [

14], while transition season savings average 20%. Old buildings with high vacancy times show the greatest improvement potential, with median savings of 21-26% compared to simple on-off control [

78]. Poorly-insulated buildings achieve 13% profit from intelligent control versus 26% for well-insulated buildings [

86], suggesting that building envelope quality moderates but does not eliminate benefits.

Studies comparing against rule-based control consistently report higher savings than those comparing against conventional MPC. DDPG achieves 98% comfort violation reduction versus rule-based control but only 79% versus DQN [

43]. Similarly, AI-assisted approaches show 51.09% cost reduction versus rule-based methods but only 4.34% versus single-agent DRL [

46].

Longer prediction horizons enable greater savings but face diminishing returns beyond certain thresholds. The optimal horizon depends on building thermal mass and occupancy patterns [

87]. Temperature prediction accuracy degrades with prediction horizon, with optimal performance within 4-hour windows [

54], while medium-term predictions benefit from cumulative training strategies achieving lowest RMSE of 34.9 kW [

33].

6.2. MPC versus Deep Reinforcement Learning

Both MPC and DRL demonstrate effectiveness, but their relative advantages depend on application context.

MPC excels when accurate building models are available and interpretability is important. MPC explicitly handles constraints [

88] and provides predictable behaviour through optimization-based decision making. Commercial implementation has been demonstrated with proven energy savings [

14].

DRL eliminates the need for explicit building models, learning directly from interaction with the environment [

43]. This model-free characteristic proves valuable when building physics are complex or poorly characterized. DRL demonstrates high generalization and adaptability to unseen environments, suggesting practical advantages for diverse building stocks.

Recent studies increasingly combine MPC with machine learning, using neural networks for prediction within MPC frameworks or employing DRL to optimize MPC parameters [

36]. The ALSTM-Fast MPC system demonstrates adaptability to changing thermal dynamics while maintaining the constraint-handling capabilities of MPC [

26].

6.3. Field Trial versus Simulation Findings

Field trial results typically show lower but more reliable savings than simulation studies.

Pre-trained DRL models achieve approximately 30% cost reduction in simulation but up to 21% in real deployment [

42]. This gap reflects unmodeled disturbances, sensor noise, and actuator limitations present in real buildings. Field trials also reveal practical challenges including control delays, software malfunctions [

42], and user override behaviors [

25] that simulations typically neglect.

However, field trials demonstrate that intelligent control can succeed in operational settings. The "Office-in-the-Loop" system achieved 47.92% energy savings in a real office environment [

59], while MPC implementation in a commercial building maintained temperature tracking errors below 1°F throughout occupied periods [

14].

6.4. Addressing Occupancy Uncertainty

Studies handling occupancy uncertainty demonstrate more robust performance across varied conditions.

Monte Carlo-based uncertainty analysis provides robust estimates of MPC performance against randomness in EV arrival and departure schedules [

17]. Probabilistic occupancy prediction enables aggressive demand response strategies by reducing overestimation of productivity deterioration [

89]. Change-point analysis for occupancy estimation achieves sufficient accuracy (70% precision, 60% recall) to enable meaningful energy savings while preserving privacy [

45].

The federated learning approach addresses privacy concerns while enabling personalized comfort models, with real-time model adaptation at the client level [

52]. This decentralized architecture reduces data transmission dependency while improving predictive accuracy through incremental client-side updates.

6.5. Implementation Challenges and Practical Considerations

6.5.1. Technical Barriers