1. Introduction

Pain remains a major global health concern requiring continuous attention from healthcare professionals. Effective pain management significantly impacts patients' quality of life, functional capacity, and psychological well-being [

1,

2]. Nurses play a vital role in pain assessment and management, serving as primary caregivers who coordinate both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions [

3].

Contemporary evidence supports multimodal pain management, which integrates pharmacological approaches (analgesics, opioids, adjuvant medications) with non-pharmacological strategies (physical comfort measures, cognitive-behavioral techniques, relaxation, and spiritual support). This comprehensive approach is essential because reliance on any single modality often proves insufficient [

4,

5]. However, studies have reported persistent gaps in nurses' pain management practices [

6,

7]. While 83.3% of nurses reported regular pain assessment in one study, only 32.2% used standardized tools such as the numeric rating scale [

8], and 77.8% lacked positive attitudes toward pain management [

9]. Non-pharmacological interventions, despite their evidence base and safety profile, remain underutilized globally [

5,

10].

The Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) framework provides a theoretical foundation for understanding factors influencing healthcare behaviors [

11]. According to this framework, knowledge acquisition leads to attitude formation, which subsequently influences practice. While previous studies in Vietnam have examined nurses' knowledge and attitudes toward pain management separately [

8,

9], there is a paucity of research examining: (1) the actual practice of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, (2) the interrelationships among KAP domains, and (3) predictors of competent practice. Furthermore, no study has quantified the magnitude of training effects using standardized effect sizes, limiting the ability to assess practical significance beyond statistical significance.

This study addresses these gaps by comprehensively examining pain management practices among nurses caring for post-surgical patients in Vietnam. The specific objectives were to: (1) assess nurses' current implementation of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain management interventions, (2) examine the relationships among knowledge, attitude, and practice domains, (3) compare practice competency between trained and untrained nurses with effect size quantification, and (4) identify predictors of competent practice. The findings contribute novel evidence to inform nursing education policy and clinical practice guidelines in Vietnam and similar low- and middle-income country settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at two tertiary public hospitals in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: Cho Ray Hospital (a 1,800-bed national referral center) and a second major public hospital. Both institutions serve as regional referral centers with high surgical volumes and standardized nursing protocols. The study setting was selected to capture pain management practices in high-acuity environments representative of tertiary care in Vietnam.

2.2. Participants

Eligible participants were registered nurses working in the Urology Departments of the study hospitals who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) current employment as a registered nurse, (2) minimum one year of experience providing direct care to post-surgical patients, and (3) willingness to participate. Nurses on leave during the data collection period or those with administrative-only roles were excluded.

Sample size was calculated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2). With an expected effect size of 0.20, power of 90%, and 5% margin of error for multiple regression with six predictors, the required sample was 209 participants. To account for potential 10% rate of invalid or incomplete responses, 230 nurses were recruited using simple random sampling from staff rosters. All 230 recruited nurses completed the survey (response rate: 100%).

2.3. Study Instruments

The study utilized a self-administered questionnaire consisting of four parts:

Part I: Demographic characteristics included age, sex, highest educational attainment (diploma, bachelor's, master's degree), years of clinical experience, and prior pain management education.

Part II: Knowledge assessment consisted of 29 items covering pain physiology, assessment, and management principles. Each correct response scored 1 point (range: 0–29).

Part III: Attitude assessment included 14 items measuring personal beliefs about pain, patient assessment attitudes, and management philosophies, rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

Part IV: Practice assessment was adapted from Menlah et al. (2018) [

12], consisting of 15 items: non-pharmacological interventions (10 items) covering environmental comfort, physical modalities, cognitive-behavioral techniques, and spiritual support; and pharmacological interventions (5 items) covering medication administration practices. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always).

The adapted Vietnamese version underwent forward-backward translation and was reviewed by a panel of five nursing experts for content validity. The instrument demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.821 for practice, 0.869 for knowledge) and acceptable content validity (S-CVI/Ave = 0.88).

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected between April and June 2024. After obtaining hospital approval, eligible nurses were identified from departmental staff rosters and randomly selected. Selected nurses were individually approached during shift changes, provided with study information sheets, and given time to consider participation. Those who agreed signed informed consent forms before completing the questionnaire. Questionnaire completion took approximately 15–20 minutes.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Cho Ray Hospital (approval no. 1747/CN-HDDD). Participants were fully informed about the study's purpose, voluntary nature, and their right to withdraw. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Anonymity was maintained throughout data collection and analysis.

2.6. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi software (version 2.3) and Python (version 3.10). Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Group comparisons: Independent samples t-tests compared practice scores between trained and untrained nurses. Cohen's d effect sizes were calculated to quantify the magnitude of differences, interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8) effects [

13]. One-way ANOVA compared practice scores across education levels with post-hoc Tukey tests.

Correlation analysis: Pearson correlation coefficients examined relationships among knowledge, attitude, and practice domains.

Regression analysis: Two multiple linear regression models were conducted—one for pharmacological practice and one for non-pharmacological practice—with demographic variables and prior training as predictors. Assumptions were verified including linearity, independence (Durbin-Watson), homoscedasticity, multicollinearity (VIF < 10), and normality of residuals.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed)

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 230 participating nurses. The mean age was 37.3 years (SD = 6.67, range: 22–53), and the majority were female (81.3%). Participants had substantial clinical experience (mean = 13.7 years, SD = 5.84). Most held bachelor's degrees (84.8%), with 11.7% holding diplomas and 3.5% holding master's degrees. Notably, only 42.6% (n = 98) had previously attended formal pain management education, while 57.4% (n = 132) reported no formal training despite their considerable clinical experience.

3.2. Pain Management Practices: Overall Findings

Overall, nurses demonstrated moderate-to-good pain management competency. Pharmacological interventions (M = 3.74, SD = 0.49) were implemented more consistently than non-pharmacological interventions (M = 3.48, SD = 0.50). This difference was statistically significant (paired t = 8.86, p < 0.001), indicating systematic prioritization of medication-based approaches.

3.3. Impact of Prior Training on Practice

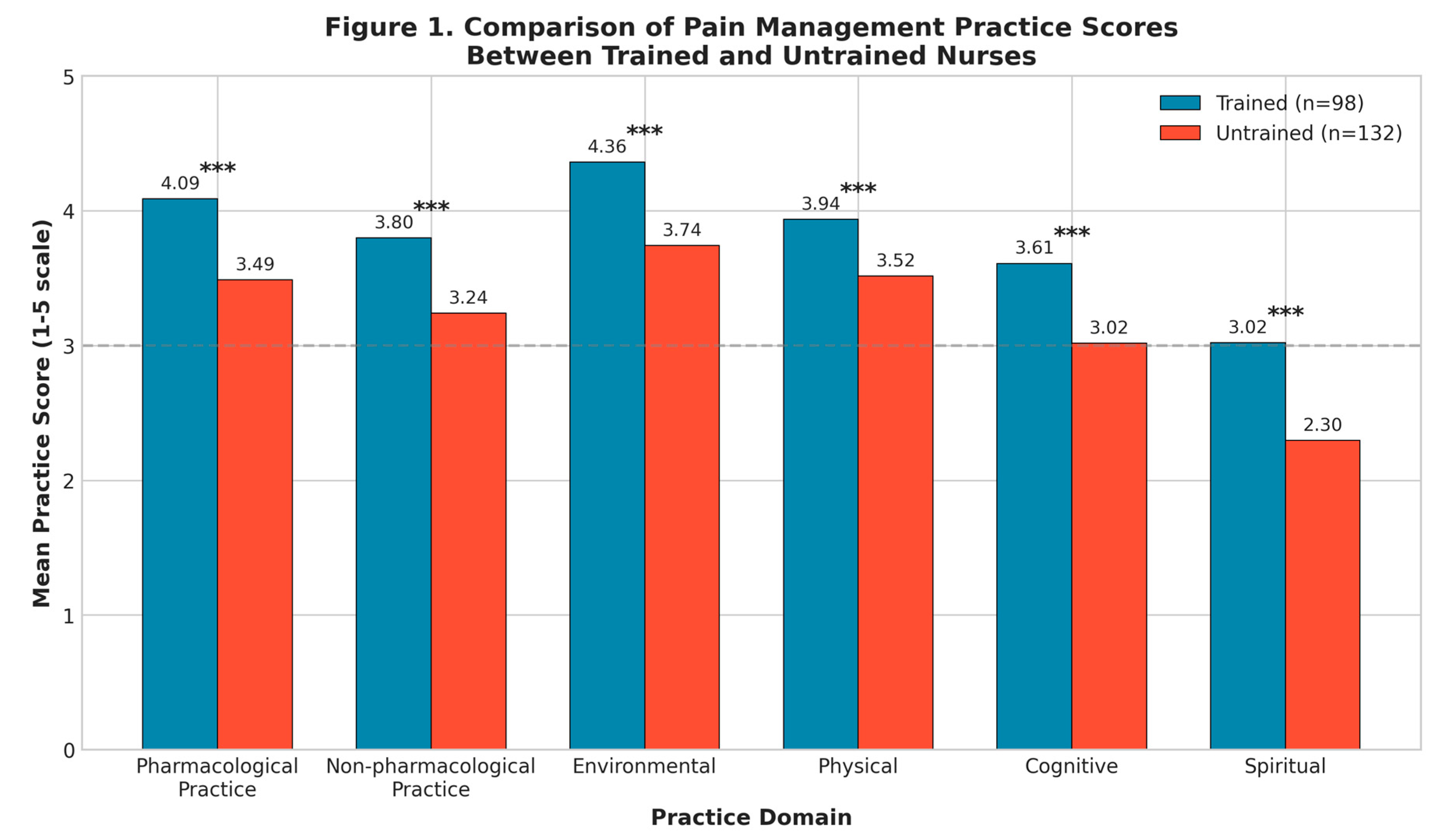

To examine the effect of formal training, we compared mean scores between trained (n = 98) and untrained (n = 132) nurses (

Table 2,

Figure 1). Trained nurses demonstrated significantly higher scores across all practice domains with large effect sizes. For pharmacological practice, trained nurses scored substantially higher (M = 4.09, SD = 0.37) than untrained nurses (M = 3.49, SD = 0.42), with this difference being statistically significant (t = 11.55, p < 0.001) and representing a large effect size (Cohen's d = 1.54). Similarly, non-pharmacological practice scores were significantly higher among trained nurses (M = 3.80, SD = 0.41) compared to untrained nurses (M = 3.24, SD = 0.43; t = 10.01, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 1.34). The training effect extended beyond practice behaviors to underlying competencies: knowledge scores differed markedly between trained (M = 22.11, SD = 2.89) and untrained nurses (M = 17.11, SD = 2.91; t = 12.95, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 1.73), as did attitude scores (trained: M = 3.85, SD = 0.35; untrained: M = 3.33, SD = 0.38; t = 10.66, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 1.42). All effect sizes exceeded Cohen's threshold for large effects (d > 0.80), indicating that formal training has substantial practical significance. Trained nurses scored approximately 1.0–1.7 standard deviations higher than untrained colleagues.

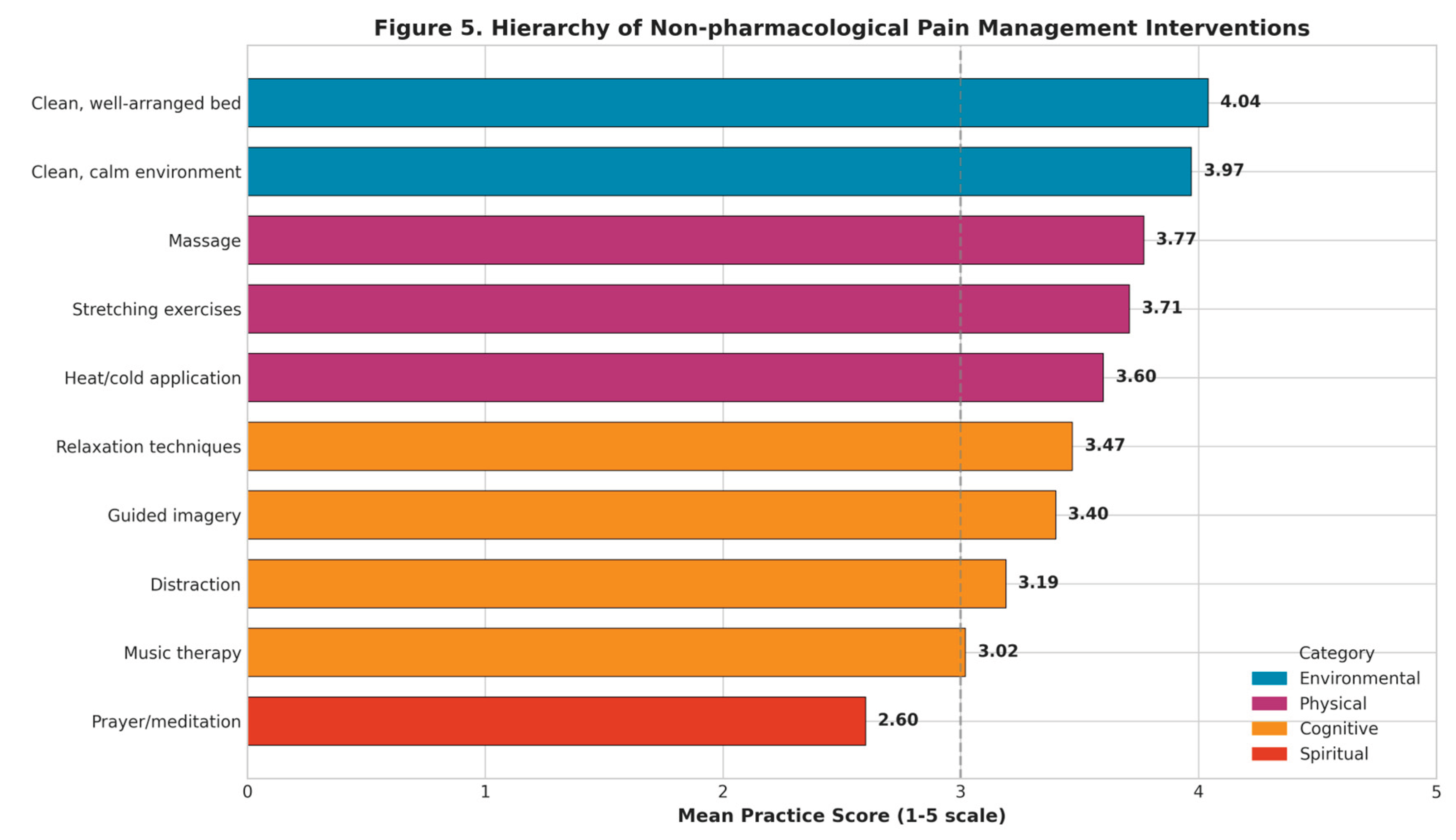

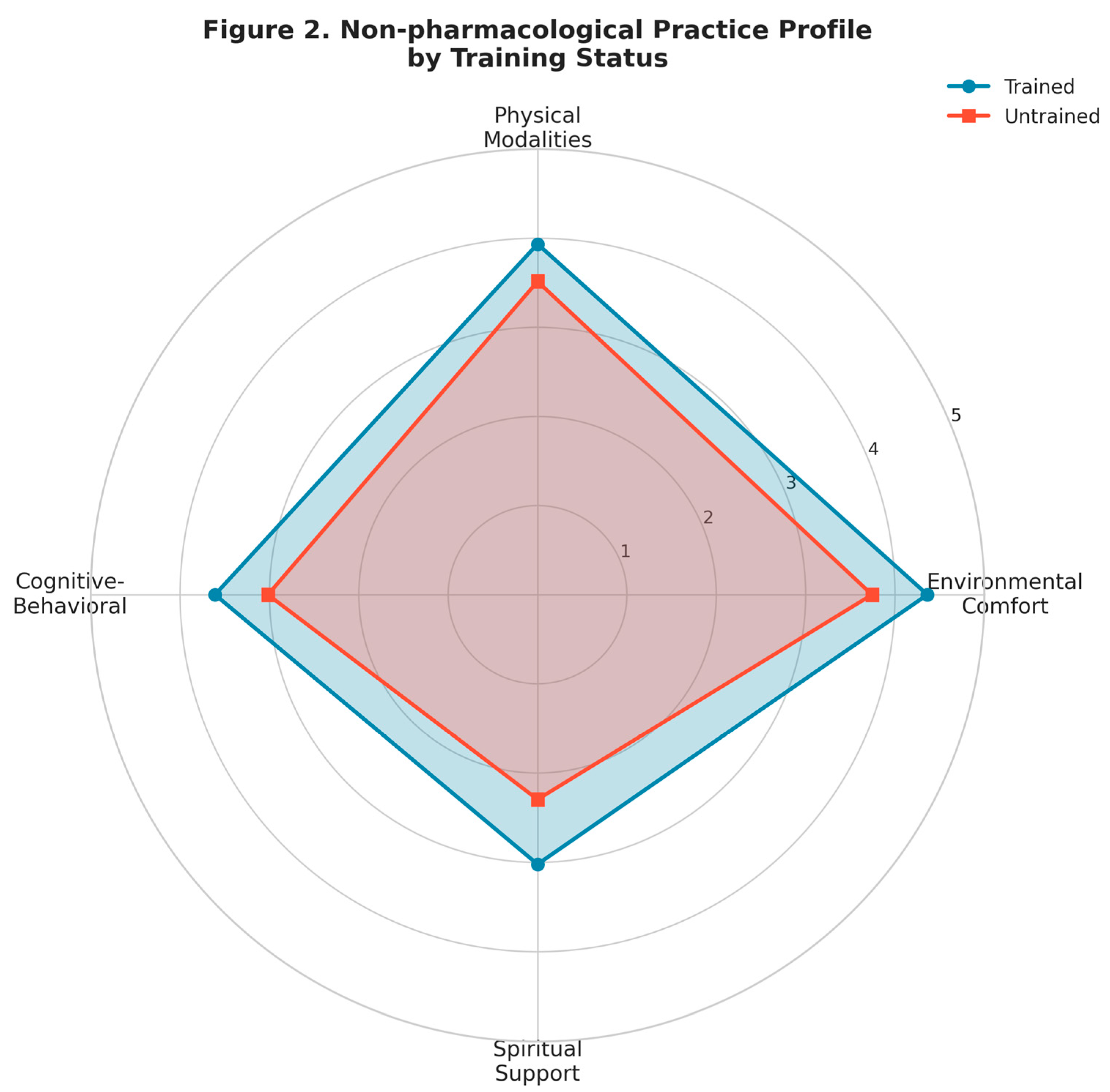

3.4. Hierarchy of Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Analysis of non-pharmacological practice revealed a clear four-tier hierarchy (

Figure 2,

Figure 5). Environmental comfort interventions ranked highest, including clean bed arrangement (M = 4.04, SD = 0.87) and ventilated environment (M = 3.97, SD = 0.78), followed by physical modalities such as massage (M = 3.77, SD = 0.82), stretching (M = 3.71, SD = 0.87), and heat/cold application (M = 3.60, SD = 0.97). Cognitive-behavioral techniques showed moderate-to-low implementation: relaxation (M = 3.47, SD = 0.91), guided imagery (M = 3.40, SD = 1.01), distraction (M = 3.19, SD = 1.02), and music therapy (M = 3.02, SD = 1.00). Spiritual support through prayer/meditation encouragement was least implemented (M = 2.60, SD = 1.29). Trained nurses outperformed untrained nurses across all categories, with the largest effects for cognitive-behavioral techniques (d = 1.08) and environmental comfort (d = 0.97).

3.5. Pharmacological Pain Management Practices

Table 3 presents pharmacological practices. Scheduled opioid administration (M = 3.90, SD = 0.75), dose titration (M = 3.85, SD = 0.74), and PRN medication (M = 3.84, SD = 0.78) were consistently implemented. An ethically concerning finding emerged: placebo injection use to verify pain authenticity (M = 3.34, SD = 1.07) showed high variability, indicating substantial disagreement among nurses.

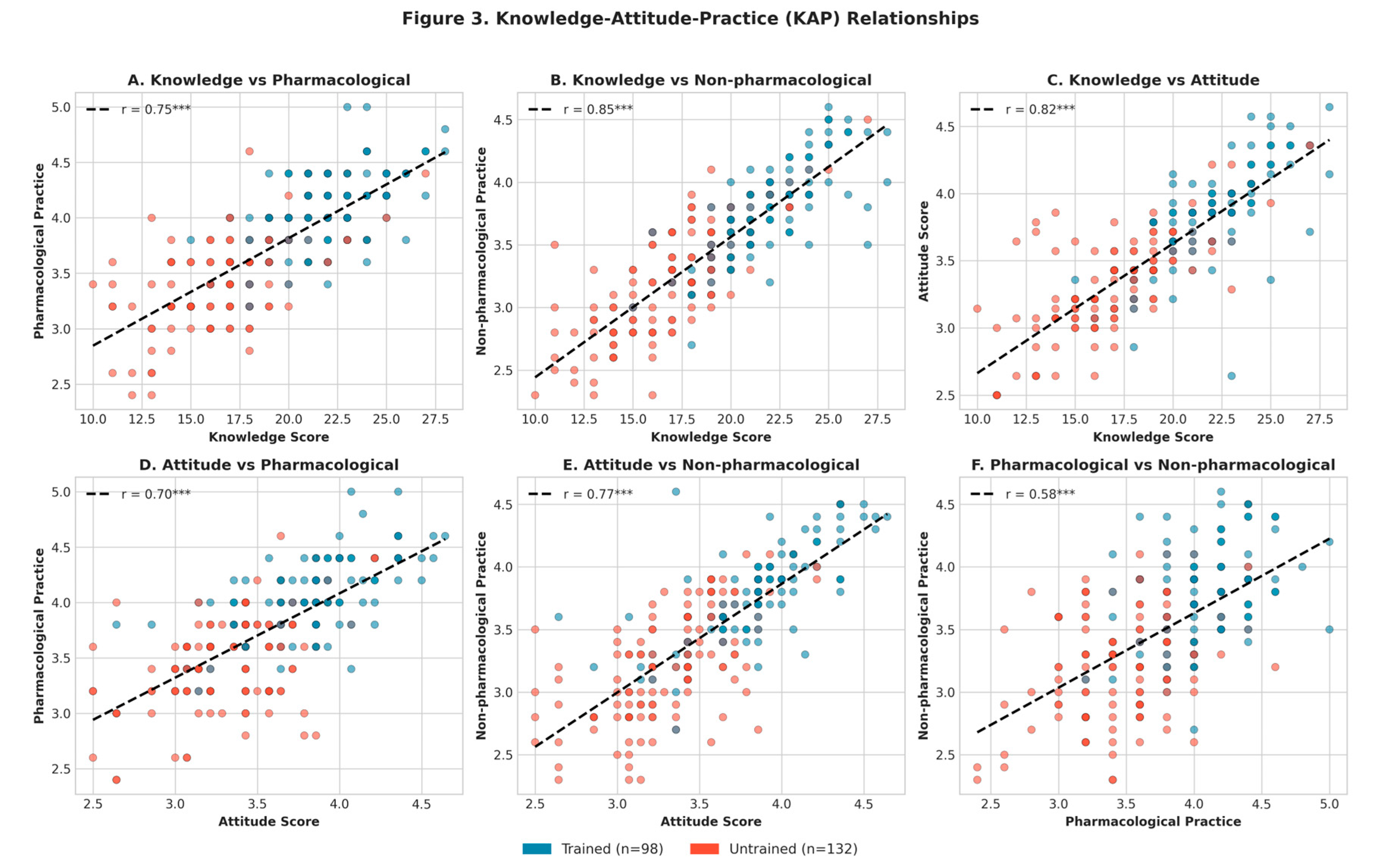

3.6. Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) Relationships

Pearson correlation analysis revealed strong positive associations among KAP domains (

Figure 3). Knowledge was strongly correlated with both pharmacological (r = 0.76, p < 0.001) and non-pharmacological practice (r = 0.85, p < 0.001), while attitude showed similar patterns with pharmacological (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) and non-pharmacological practice (r = 0.77, p < 0.001). Knowledge and attitude were also highly correlated (r = 0.82, p < 0.001). These strong correlations support the KAP theoretical framework. Notably, knowledge was more strongly associated with non-pharmacological practice than pharmacological practice, suggesting non-pharmacological interventions are more knowledge-dependent.

3.7. Predictors of Pain Management Practice

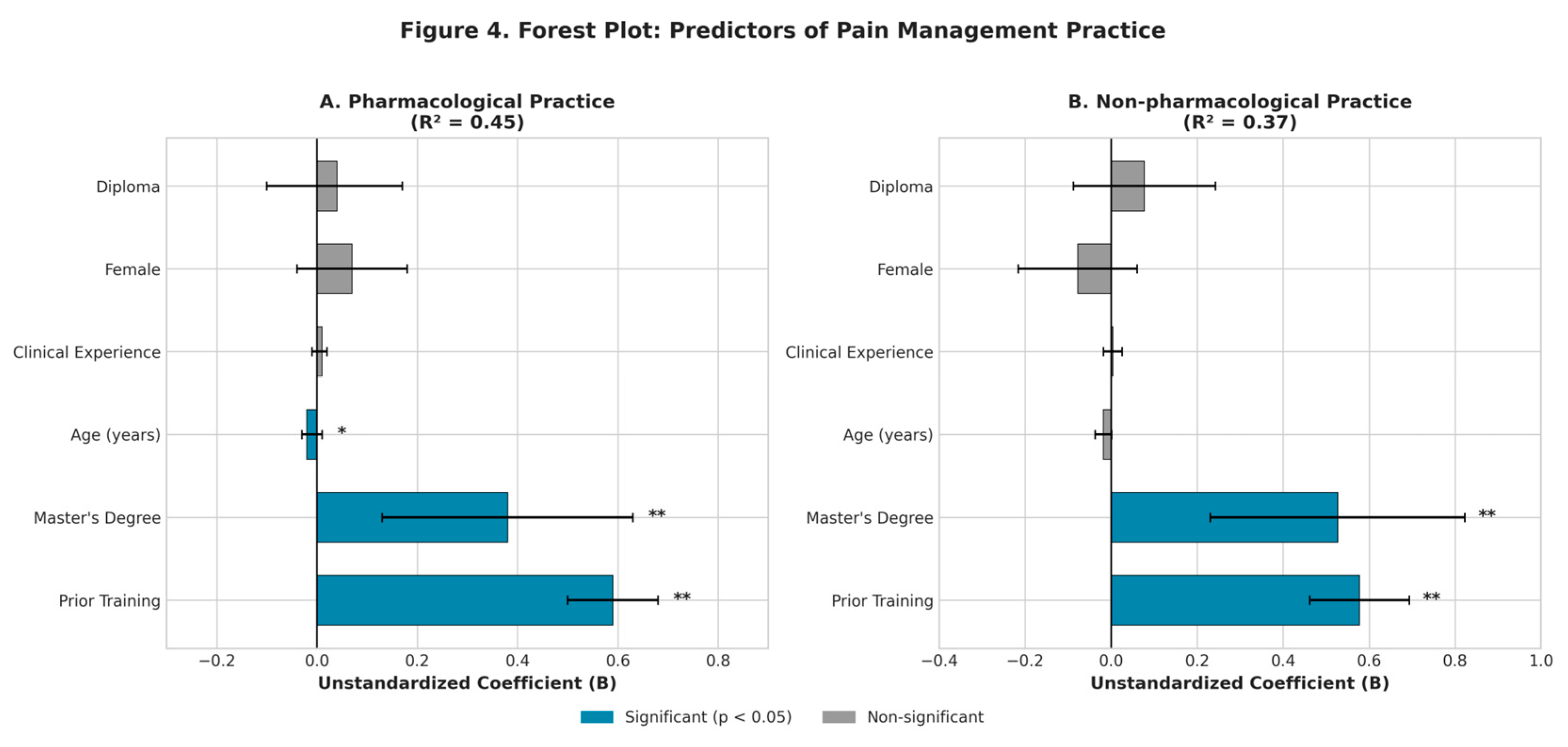

Multiple linear regression identified predictors of both practice domains (

Table 4,

Figure 4). For pharmacological practice (R² = 0.45, F = 30.12, p < 0.001), prior training was the strongest predictor (B = 0.59, β = 1.31, p < 0.001), followed by master's education (B = 0.38, p = 0.003), while age showed a small negative association (B = −0.02, p = 0.033) and clinical experience was not significant (p = 0.442). Non-pharmacological practice (R² = 0.37, F = 22.08, p < 0.001) showed similar patterns: prior training (B = 0.58, p < 0.001) and master's education (B = 0.53, p = 0.001) were significant predictors, while clinical experience again showed no effect (p = 0.718). Across both domains, formal training and advanced education—not clinical experience—predicted competent practice.

Figure 5.

Hierarchy of non-pharmacological pain management interventions ranked by mean implementation score. Dashed line indicates moderate level (score = 3). Color coding: blue = environmental, purple = physical, orange = cognitive-behavioral, red = spiritual.

Figure 5.

Hierarchy of non-pharmacological pain management interventions ranked by mean implementation score. Dashed line indicates moderate level (score = 3). Color coding: blue = environmental, purple = physical, orange = cognitive-behavioral, red = spiritual.

4. Discussion

4.1. Novel Contributions

This study provides several novel contributions. First, it offers the first comprehensive assessment of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain management practices among Vietnamese nurses with effect size quantification, extending beyond previous studies focusing on knowledge or attitudes alone [

8,

9]. Second, it demonstrates that formal training—not clinical experience—predicts competent practice, with large effect sizes (d = 1.34–1.54) indicating substantial practical significance. Third, it documents a clear hierarchy of non-pharmacological interventions that can guide targeted training. Fourth, it validates the KAP framework with strong correlations (r = 0.70–0.85), providing theoretical support for knowledge-focused educational interventions.

4.2. The Critical Role of Formal Training

The most significant finding is that prior formal training strongly predicted both pharmacological and non-pharmacological practice, while clinical experience showed no effect in either model. The large effect sizes—trained nurses scoring 1.0–1.7 standard deviations higher than untrained colleagues—demonstrate that this difference has substantial practical significance beyond statistical significance.

This finding challenges the assumption that nursing competencies naturally develop through on-the-job experience. Instead, it suggests that experiential learning alone is insufficient for developing evidence-based pain management skills. Structured educational interventions are essential. Healthcare institutions should prioritize formal training programs over reliance on accumulated experience for competency development.

4.3. KAP Relationships and Educational Implications

The strong KAP correlations support the theoretical framework that knowledge and attitude are prerequisites for practice. Notably, knowledge was more strongly correlated with non-pharmacological practice (r = 0.85) than pharmacological practice (r = 0.76). This suggests that non-pharmacological interventions—which require understanding of psychological principles and therapeutic techniques—are more knowledge-dependent than medication administration.

These findings have direct implications for curriculum design: educational programs should emphasize cognitive-behavioral techniques and spiritual care approaches, which showed the largest implementation gaps despite being evidence-based interventions [

5,

10].

4.4. Hierarchy of Non-Pharmacological Interventions

The documented hierarchy (environmental > physical > cognitive > spiritual) aligns with international findings [

10,

14] and reflects practical constraints. Environmental and physical comfort measures require minimal training and resources. In contrast, cognitive-behavioral techniques require specialized knowledge and time, while spiritual care may involve cultural sensitivity and personal discomfort.

The finding that training most strongly improved cognitive-behavioral practice (d = 1.08) suggests that educational interventions specifically targeting these underutilized evidence-based techniques could substantially improve pain care quality.

4.5. Ethical Concerns

The moderate use of placebo injections to verify pain authenticity (M = 3.34) raises significant ethical concerns. This practice undermines therapeutic relationships and contradicts the principle that pain is subjective [

7]. Educational programs should explicitly address the ethical dimensions of pain assessment.

4.6. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Second, self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias. Third, the two-hospital sample limits generalizability. Fourth, patient outcomes were not assessed. Fifth, the study focused on postoperative pain; findings may not fully generalize to chronic pain contexts. Future research should examine training intervention effectiveness and patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

These findings support several recommendations for nursing education policy. Mandatory pain management education programs should be implemented for nurses at all experience levels, with particular curriculum emphasis on underutilized cognitive-behavioral techniques. Healthcare institutions should establish clear ethical guidelines regarding pain assessment practices and recognize that clinical experience alone does not ensure competency development. Investment in structured training programs should take priority over assumptions that competency develops naturally through clinical experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.H.L. and H.T.V.; methodology, T.B.T.T.; formal analysis, V.H.L.; data curation, H.T.V.; writing—original draft, M.H.D. and C.T.T.N.; writing—review and editing, T.A.N. All authors read and agreed to the published manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approved by Human Research Ethics Committee, Cho Ray Hospital (no. 1747/CN-HDDD, April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Reporting Guidelines: Conducted per STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

References

- Tiruneh, A.; Tamire, T.; Kibret, S. The magnitude and associated factors of post-operative pain at Debre Tabor comprehensive specialized hospital, Debre Tabor Ethiopia, 2018. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211014730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, M.Z.; Yirdaw, L.T. Management of postoperative pain among health professionals working in governmental hospitals in South Wollo Zone, Northeast Ethiopia. Prospective cross sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 80, 104148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, A.-M.; Jones, R. Role of the nurse in the assessment and management of post-operative pain. Nurs. Stand. 2020, 35, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchesi, N.; Govoni, S.; Allegri, M. Non-drug pain relievers active on non-opioid pain mechanisms. Pain Pract. 2022, 22, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeleke, S.; Kassaw, A.; Eshetie, Y. Non-pharmacological pain management practice and barriers among nurses working in Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negash, T.T.; Belete, K.G.; Tlilaye, W.; Ayele, T.T.; Oumer, K.E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of health professionals towards postoperative pain management at a referral hospital in Ethiopia. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 73, 103167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, S.-D.M.; Varaei, S.; Jalalinia, F. Nurses' knowledge and attitude towards postoperative pain management in Ghana. Pain Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 4893707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, P.H.; Tran, D.V.; Le, Y.T.; Thu Do, H.T.; Vu, S.T.; Dinh, H.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Postoperative pain management among registered nurses in a Vietnamese hospital. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 6829153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.Q. Knowledge and attitudes related to pain management for post-operative patients at the orthopedic unit Viet Duc university hospital. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 3, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Bayoumi, M.M.; Khonji, L.M.A.; Gabr, W.F.M. Are nurses utilizing the non-pharmacological pain management techniques in surgical wards? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launiala, A. How much can a KAP survey tell us about people's knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on malaria in pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropol. Matters 2009, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menlah, A.; Garti, I.; Amoo, S.A.; Ameho, J.K. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of nurses regarding postoperative pain management in Cape Coast Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 11, 965–976. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ehwarieme, T.A.; Josiah, U.; Abiodun, O.O. Postoperative pain assessment and management among nurses in selected hospitals in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. J. Integr. Nurs. 2023, 5, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |