1. Introduction

Wheat blast, caused by

Magnaporthe oryzae pathotype

Triticum (MoT), has emerged as one of the most destructive diseases threatening global wheat production and food security [

1,

2]. Since its first appearance in Brazil in 1985, the pathogen has spread across South America and was reported in Bangladesh in 2016, marking its first outbreak in Asia [

3,

4]. More recently, wheat blast occurrence in Zambia [

2] raised serious concerns about the transcontinental spread of this pathogen through seed and wind dispersal [

5]. Considering that China and India, the world’s leading wheat producers share borders with Bangladesh, the risk of disease incursion poses a significant food security threat ([

1].

The fungus predominantly attacks wheat spikes, leading to shriveled or deformed grains within days of infection and causing yield losses of up to 100% under favorable conditions [

6]. The visual symptoms of wheat blast closely resemble those of Fusarium head blight, complicating accurate field diagnosis and management [

7]. Despite decades of research, no fully resistant wheat cultivars are available, and current control relies largely on fungicide use and cultural practices, which provide limited and inconsistent protection. Because MoT can spread through infected seeds and crop residues, early and accurate detection of the pathogen is essential for effective quarantine enforcement, seed certification, genomic surveillance, and timely disease management [

5,

8]. Another complication is that MoT is predominantly a head disease and remain almost aymptomatic at the vegetative stage of wheat. As a result, once bleached head symptoms are seen in the field, fungicide application is ineffective in protecting yield loss. Conventional diagnostic tools such as PCR and qPCR, though reliable, require well-equipped laboratories, a stable power supply, and trained personnel that limit their use in field settings [

9,

10]. In contrast, recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) is an innovative isothermal nucleic acid amplification method that enables rapid, sensitive, and instrument-free detection under constant low temperatures [

11,

12,

13]. RPA reactions require only a pair of 30–35 bp primers and can be completed within 30 minutes at 37–42 °C [

14,

15]. The resulting amplicons can be analyzed using various methods, including gel electrophoresis, fluorescent probes, or lateral flow strips [

16,

17]. Among these, lateral flow strips provide a simple, rapid, and visual means of detecting amplification results with the naked eye [

18,

19]. Therefore, coupling RPA with lateral flow detection technology offers a powerful approach for visual, on-site identification of target pathogens within a short time.

Robust, concept-proven diagnostic technologies are crucial for mitigating plant diseases and minimizing yield losses through timely and accurate detection [

19,

20]. The recent development of CRISPR-Cas-based diagnostic assays for wheat blast represents a major breakthrough, as these tools have demonstrated high specificity and strong potential for precise pathogen identification [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. This proof of concept underscores the potential of CRISPR-based technology to enhance genomic surveillance and containment of the wheat blast pathogen [

24]. However, current CRISPR diagnostic methods often depend on temperature-sensitive reagents and multistep laboratory procedures, which limit their portability and field application [

19,

22]. Furthermore, there is an ongoing need to simplify DNA extraction and sample preparation to facilitate the on-site application of Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) in remote field settings [

19].

Despite the urgent need for early and accurate detection, no large-scale, rapid, and field-deployable diagnostic kits are currently available for effective quarantine and genomic surveillance of wheat blast [

24]. To address this gap, we developed and optimized an RPA-based molecular detection system coupled with lateral flow strip (PCRD) visualization. The assay was validated using infected leaves, spikes, and seeds, and was further streamlined with a crude sap DNA extraction method based on alkaline polyethylene glycol (PEG-NaOH) to enable reliable on-site detection. This study aimed to: (i) improve a rapid, and convenient diagnostic kit for wheat blast by excluding the patented Cas12a enzyme and optimizing the DNA extraction process; (ii) evaluate and validate the efficacy of the kit using field samples, including wheat plants, spikes, seeds, and alternate grass hosts; (iii) validate diagnostic specificity against major fungal phytopathogens, including the rice blast fungus (

M. oryzae Oryzae) and species from the genera

Fusarium,

Bipolaris,

Colletotrichum, and

Botryodiplodia; and (iv) train relevant stakeholders (researchers, extension workers, pathologists, and industry personnel) to assess the robustness, usability, and practical applicability of the developed kit.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Isolates Retrieval and Sub-Culture

Fungal isolates were retrieved from the culture repository of the Institute of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering (IBGE), Gazipur Agricultural University (GAU), Bangladesh. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Botryodiplodia theobromae isolates were kindly provided by Dr Mynul Haque of Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, Bangladesh. Isolates of Fusarium oxysporum, Magnaporthe oryzae Oryzae, Bipolaris sokiniana and other fungal isolates used were collected from the stored fungi of the Institute of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering (IBGE) of Gazipur Agricultural University, Bangladesh. The isolates were sub-cultured onto 2% potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium in Petri dishes and incubated at 26 °C for 10 days. After incubation, the white mycelial mats were carefully scraped from the surface of the agar using a sterile spatula and collected for genomic DNA extraction.

2.2. Primers and Probe Used in RPA-PCRD Strip

The MoT-specific gene sequence MoT-6098 was selected as the target gene for designing the primers and probe for the RPA assay previously identified by [

21]. Details of primers and probes used in the development of RPA-PCRD kit are provided in

Table 1. Forward primers were labeled with fluorescent 6-FAM (6-Carboxyfluorescein) while reverse were labeled with biotin. The probe has the following characteristics: 45 bp long, where 28 bases are on the 5′follow by a tetrahydrofuran abasic site (THF) replacing a base in between fluorophore and quencher; and finally, a C3 spacer block that prevents amplification. These primers for RPA used in the rapid diagnostic kit were designed by Peng Ye at al. (unpublished) of the Institute of Plant Protection of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, and we received the kits from them.

2.3. DNA Extraction from Plant Sample and Fungal Isolates

Following a 5-10-day incubation period depending on the growth of fungi on PDA plates at 26 °C, the fungal mycelia were harvested by gently scraping them from the agar surface. Infected and healthy plant samples were collected for artificially inoculated plants or naturally infected field. The collected mycelia and/ plant samples were ground thoroughly in a pre-chilled mortar and pestle to disrupt the cell walls. Genomic DNA was then extracted using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were quantified using a fluorometer, and the DNA samples were diluted with sterile distilled water to the desired working concentrations for downstream applications.

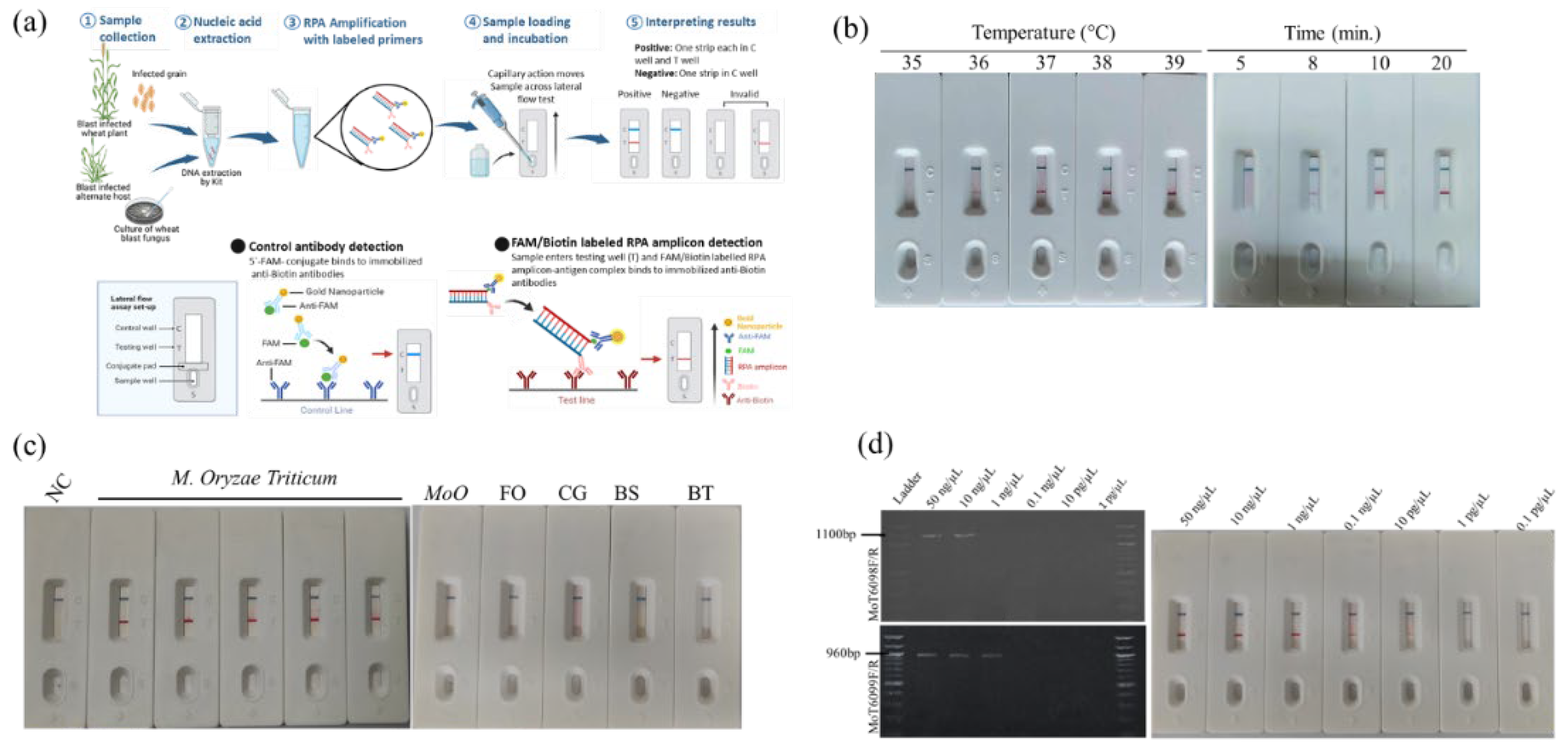

2.4. Optimization of Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Reaction

The commercial lateral flow (LF) strip, HybriDetect MGHD1, supplied by AMPfuture Biotech Ltd. Beijing, China; was applied to detect RPA amplicons visually. The LF strips were designed to detect amplicons labeled with biotin and 6-carboxy-fluorescein (FAM), which were obtained by using a AMP-Future RPA kit (Biotech Co. Ltd.; China). The RPA was conducted following the method of Lu, Zheng [

25] Each 50 µL reaction mixture was prepared in a microcentrifuge tube containing 29.4 µL of A buffer, 2 µL each of forward and reverse primers, 0.6 µL of nfo probe, 11.5 µL of ddH

2O, and 2 µL of template genomic DNA (gDNA). The reaction was initiated by adding 2.5 µL of B buffer, and the mixture was immediately incubated at 39 °C for 10 minutes. To optimize reaction conditions, the reaction time (5, 8, 10, 20 min) and temperature (35-39 °C) were varied independently, while keeping other parameters constant. PCRD strips were used to analyze the amplified products. A total of 10 μL of the amplicon was mixed with 80 μL of distilled water, and 70-75 μL of this mixture was applied onto the sample pad. Band development was monitored for up to 10 minutes, although results typically appeared within 2–3 minutes. The presence of control and test lines on the strip was visually inspected for qualitative assessment. The optimal conditions were determined based on the intensity of the amplified bands visualized on PCRD strip.

2.5. Efficacy and Specificity Tests of RPA Assay

To determine the specificity of RPA-PCRD strip assay, gDNA of five MoT isolates, other 5 pathogenic fungi strains were subjected to RPA-PCRD strip assays (

Table 1). To test the efficacy and specificity tests of RPA assay, a 10-fold serial dilution of gDNA of MoT was subjected to RPA assay. The same amount of MoT gDNA was also subjected to conventional PCR assay. The PCR reactions were prepared for a 10 μl volume containing 5 μL of DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific™), 3 μL of nuclease free water, 1 μL of 10 pmol/μL of each primer, and 1 μL of the template (initial concentration of DNA was 50 ng/μL). PCR cycling conditions were 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 40 s, and a final incubation at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified products were visualized using the Molecular Imager R (GelDocTM XR, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., USA). Both sensitivity and specificity tests were performed in twice.

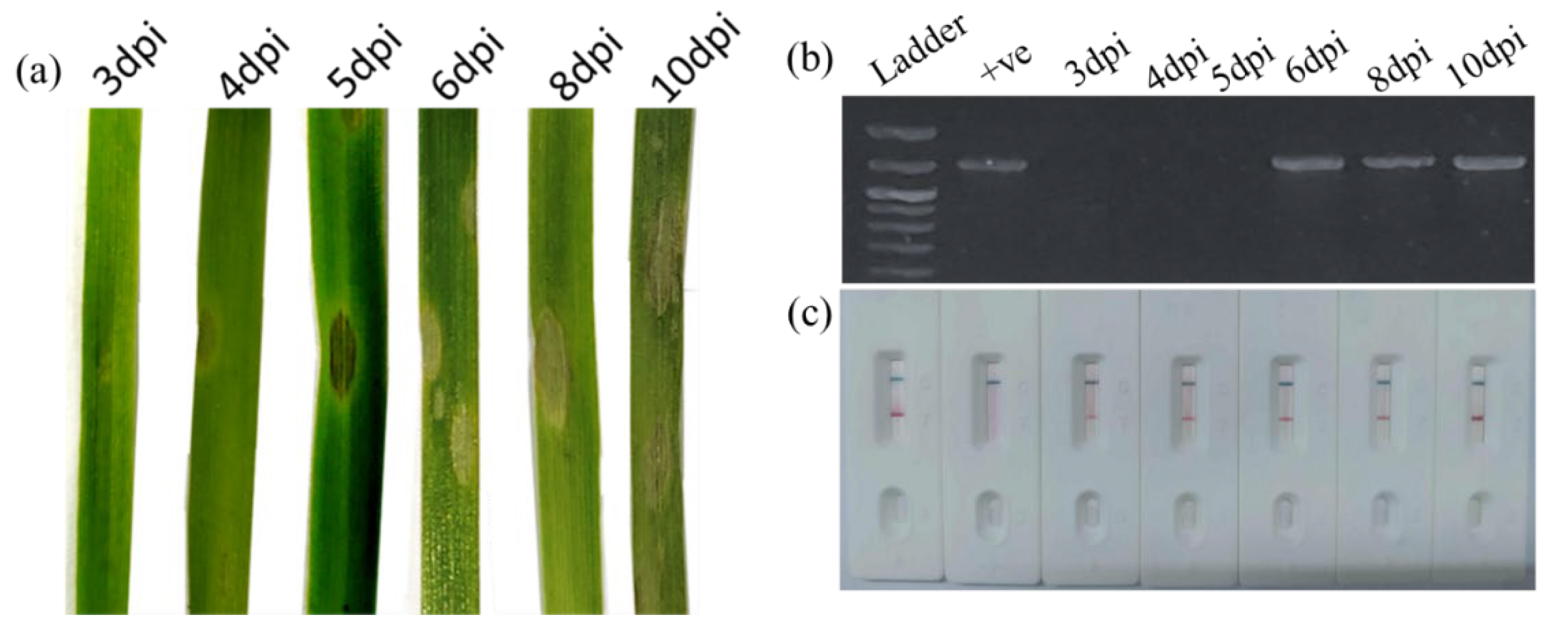

2.6. Preparation of Conidial Suspension and Artificial Inoculation of Wheat and Alternate Hosts

Conidia were induced and harvested from 10-day-old cultures of MoT grown on PDA plates, following the method described by Gupta, Surovy [

26]. To collect the conidia, the culture plates were flooded with sterile distilled water, and the surface was gently brushed with a sterile paintbrush to dislodge the conidia. The resulting suspension was filtered through sterile cheesecloth to remove mycelial debris, and the conidial concentration was adjusted to 5 × 10

4 conidia/mL using a hemocytometer.

Seeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. BARI Gom 26), maize (Zea mays), barley (Hordeum vulgare), and oat (Avena sativa) were sown in plastic pots (12 cm × 7.5 cm) containing sterilized field soil, with 10–15 seeds per pot. Ten-day-old seedlings of wheat, barley, and oat, and 15-day-old maize seedlings, were sprayed with the conidial suspension of a virulent MoT isolate (BTJP 4-5) until run-off. Inoculated plants were maintained under 16 h light per day, with 80–90% relative humidity at 26 °C and grown under natural sunlight conditions.

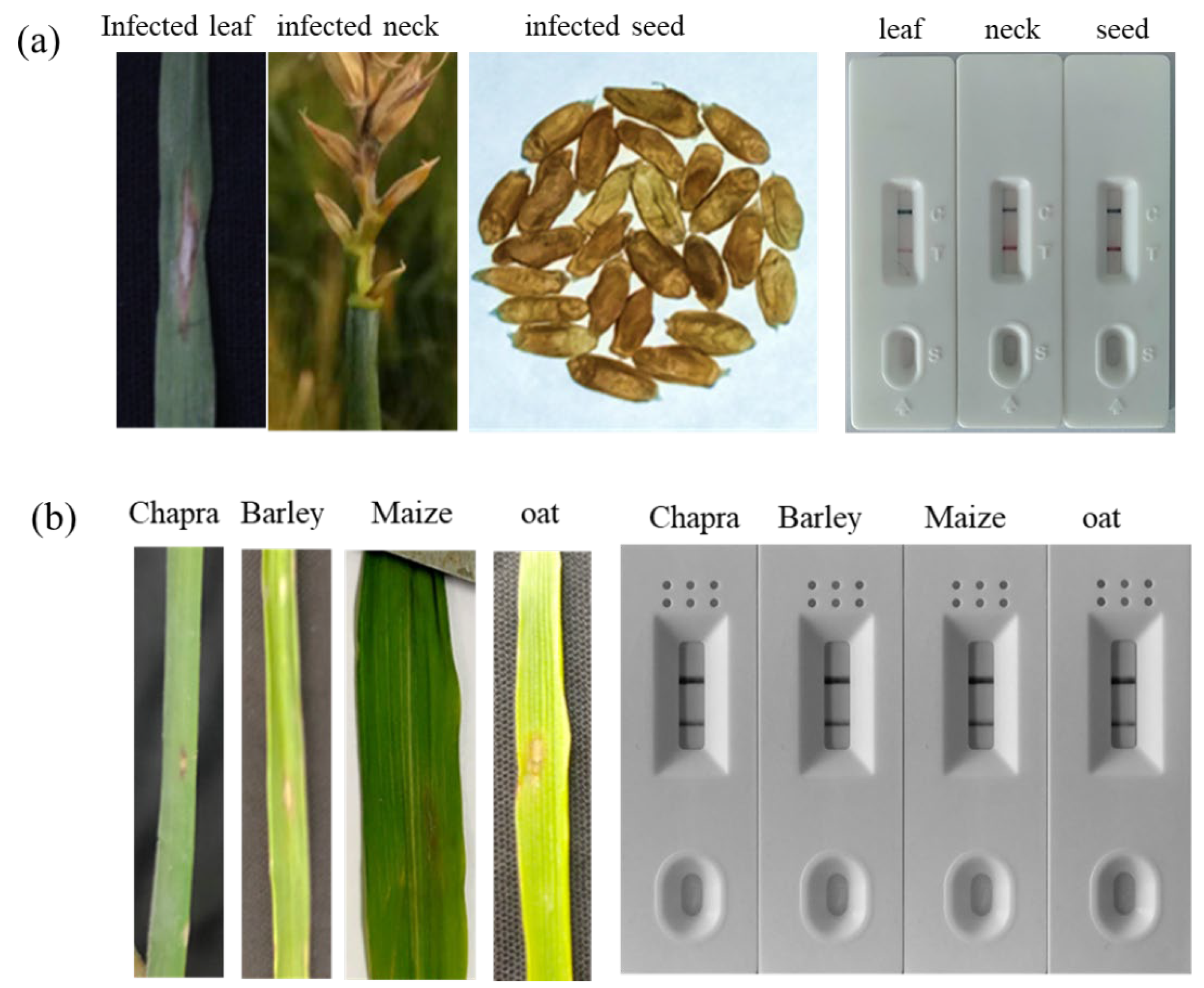

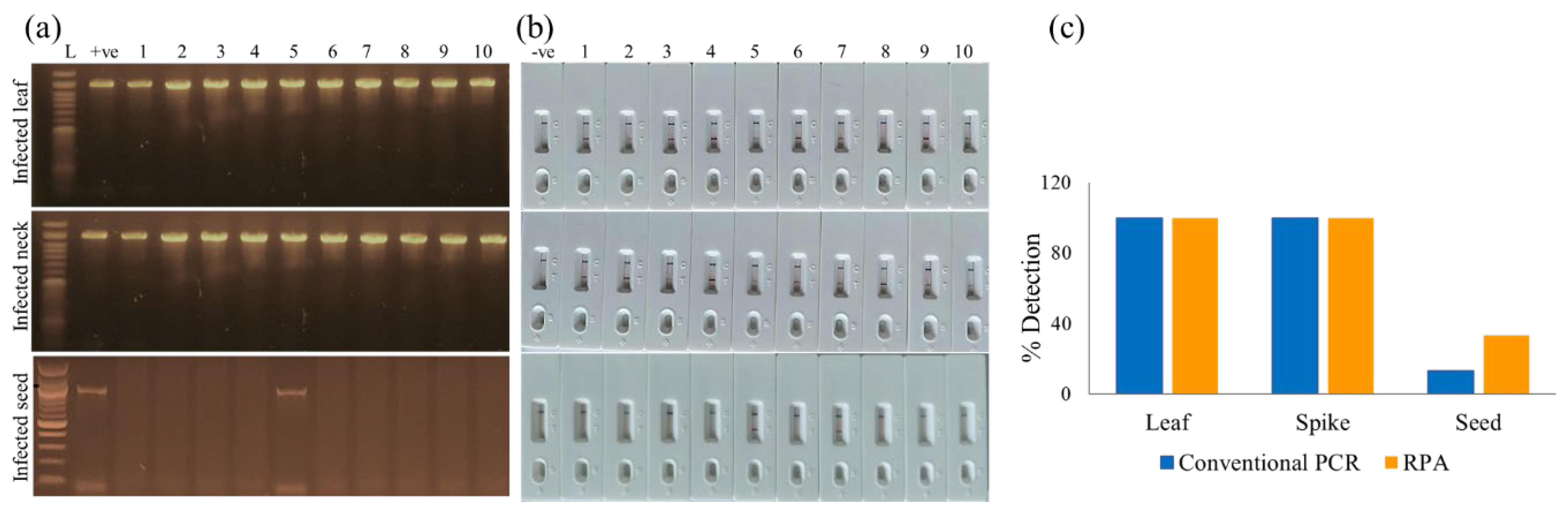

2.7. RPA-PCRD Strip Assay Using Wheat Blast-Infected Field Samples

Field samples of wheat blast were collected during the 2023–2024 growing season from multiple sites in the wheat blast hotspot district, Meherpur in Bangladesh [

4]. Samples were taken from different plant parts such as leaves, spikes, and seeds to ensure diverse representation of infection stages and symptom types. Additionally, seeds were collected from a controlled, artificially inoculated wheat plot that exhibited 20.22% disease incidence and 4.09% disease severity, providing well-characterized samples for comparison and validation of the PCR and RPA-PCRD strip assays. All collected samples were stored at –80 °C until further processing.

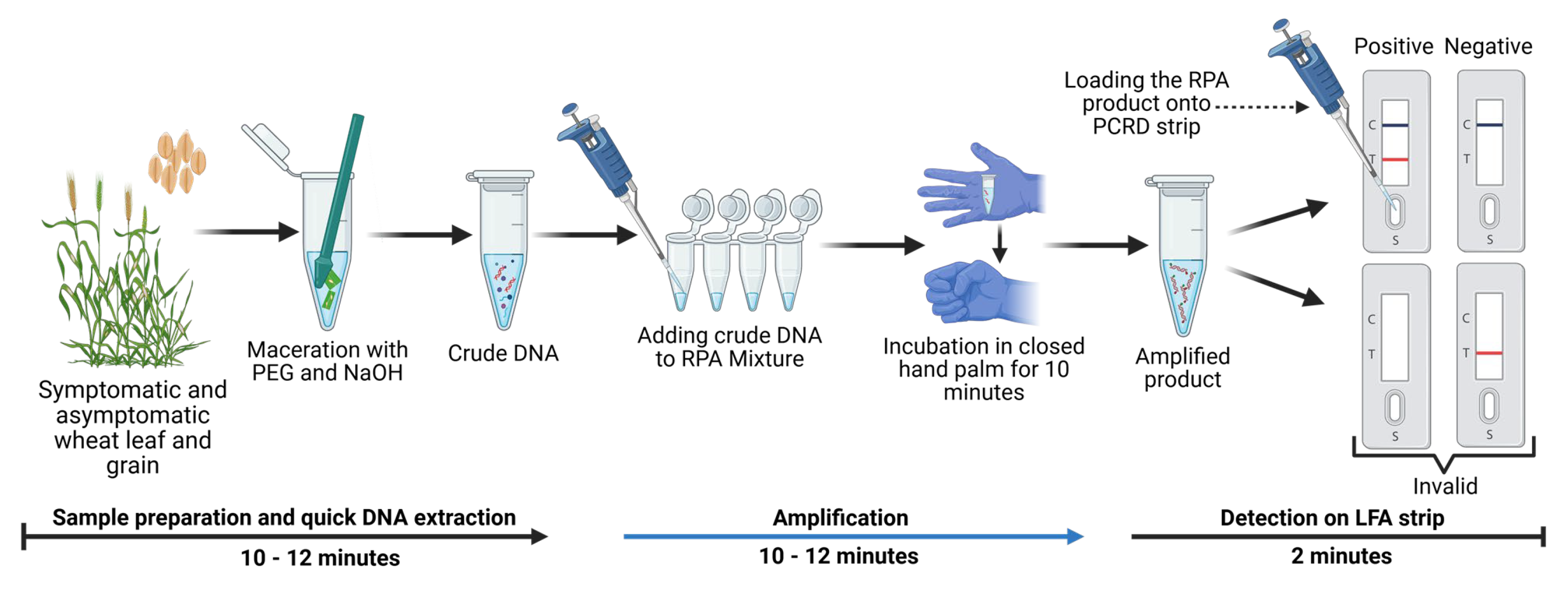

For field validation RPA-PCRD strip assay, a modified polyethylene glycol (PEG)–NaOH method was used to extract crude DNA from infected plant samples (detail procedures are described in result section). A pre-mixed cocktail containing all reagents, primers, and probe was used to minimize the risk of contamination, as developed by the Institute of Plant Protection of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China. The freeze-dried enzyme pellet was reconstituted in 49 µL of nuclease-free water, and 2 µL of crude DNA extract was added. The reaction mixture was incubated using body heat at ambient temperature (37–39 °C) for 10 minutes. The resulting product was then diluted as described earlier and applied to PCRD lateral flow strips for visualization of results.

4. Discussion

The escalating globalization of agricultural trade significantly heightens the risk of inadvertently spreading invasive phytopathogens, such as

Magnaporthe oryzae Triticum (MoT), across international borders [

1,

28]. The 2016 introduction of MoT to Bangladesh, which devastated 1,500 hectares of wheat within its first year, serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of regional food systems to seed-borne fungal pathogens [

4]. While previous efforts utilized CRISPR-Cas12-based platforms for MoT detection, their reliance on temperature-sensitive enzymes and complex multistep protocols limits their utility in resource-constrained field settings [

19]. In the study, we developed a streamlined and highly sensitive RPA–PCRD-based method for the rapid diagnosis of wheat blast fungus, MoT in seeds, infected plants and alternative hosts. While our approach builds upon previously reported CRISPR-Cas12-based platforms, it overcomes significant barriers to practical field deployment. Although CRISPR-Cas12 systems demonstrate high sensitivity, their utility in remote settings is often constrained by the temperature sensitivity of Cas enzymes and the operational complexity of multistep protocols [

19].

The hallmark of our refined method is its superior efficiency and operational simplicity; while the system reported by Kang, Peng [

21] requires two rounds of RPA amplification followed by a 25–30 minute CRISPR-Cas12 digestion step, our assay utilizes a single RPA reaction completed within just 10 minutes. This optimization significantly reduces the total diagnostic turnaround time and eliminates the need for specialized CRISPR-associated reagents and complex biochemical handling. Furthermore, unlike many molecular diagnostics that rely on sophisticated laboratory infrastructure and highly trained personnel, our RPA-based technique is robust and user-friendly. Operating efficiently at a constant temperature of 37–39 °C, the assay possesses the thermal flexibility to be powered by basic heat sources—such as portable incubators, water baths, or even ambient human body heat. These features make the method exceptionally well-suited for on-site surveillance and quarantine screening in resource-limited environments.

In this study, we targeted the MoT-6098 gene, which encodes a unique acid trehalase protein to ensure absolute diagnostic specificity for the wheat blast fungus (

Magnaporthe oryzae Triticum, or MoT) [

21]. The specificity of our RPA-PCRD system was confirmed by the absence of detection signals when tested against the rice blast fungus (MoO), other wheat pathogens such as

Fusarium and

Bipolaris, and several major phytopathogenic fungi. Furthermore, the system showed no cross-reactivity with healthy wheat tissue or background microbial DNA, reinforcing its reliability. By integrating a PEG-NaOH-based extraction method, we achieved rapid, high-quality DNA recovery suitable for field conditions, marking a significant advancement in the point-of-care detection of wheat blast.

To maximize diagnostic performance, we optimized the RPA reaction kinetics, specifically evaluating the impact of incubation time and temperature on signal intensity. While the PCRD strip produced a detectable signal in as little as 8 minutes, the band intensity, which correlates directly with the concentration of the amplified target was significantly more robust at 10 minutes. Consequently, a 10-minute incubation was selected to ensure an optimal balance between rapid turnaround and high sensitivity (

Figure 1b).

Our RPA-PCRD assay achieved a Limit of Detection (LOD) of 10 pg/µL, completed within a total timeframe of 30 minutes. This level of sensitivity is consistent with previous findings where RPA-based detection surpassed conventional PCR by 100-fold [

29] and exceeded LAMP-based methods by 10-fold [

30]. Crucially, in field-collected samples, the RPA-PCRD strip outperformed conventional PCR in MoT detection rates. While detection was more consistent in leaf and neck tissues than in seeds, this discrepancy is rooted in the pathology of MoT. MoT primarily colonizes the wheat neck, which disrupts nutrient translocation; this often results in shriveled, symptomatic seeds that may not harbor high titers of the pathogen itself [

31]. The practical utility of this method is further enhanced by its compatibility with crude plant sap. By bypassing labor-intensive DNA extraction, the total diagnostic window is reduced to approximately 20 minutes. This combination of high analytical sensitivity, biological reliability across different tissue types, and field-ready simplicity makes the RPA-PCRD system an ideal tool for real-time disease surveillance and high-stakes quarantine screening at ports and borders.

The primary advantage of the validated RPA-PCRD method lies in its operational simplicity and superior sensitivity compared to conventional PCR and CRISPR-Cas-based systems. Our assay operates under mild isothermal conditions (37–39 °C) and requires minimal equipment, contrasting sharply with the thermal cycling and specialized laboratory infrastructure necessitated by traditional methods. While the detection limit for conventional PCR in MoT diagnosis is approximately 0.1 ng/μL [

21], our RPA-PCRD assay achieved a significantly lower detection limit of 10 pg/μL. Although quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) can reach comparable sensitivity (10 pg/μL), it remains constrained by the requirement for sophisticated instrumentation and precise thermal protocols. In contrast, the RPA-PCRD strip format delivers high-sensitivity results within 30 minutes using only basic heating equipment (

Figure 6). Furthermore, the robustness of our assay eliminates the need for high-purity DNA templates, which are mandatory for both conventional PCR and other previously described molecular methods. By utilizing crude templates, we significantly reduce both the total turnaround time and the per-sample cost. These attributes—high analytical sensitivity, tolerance to inhibitors, and rapid visual interpretation make the RPA-PCRD system exceptionally well-suited for on-site agricultural inspections, port-of-entry quarantine screening, and field-based monitoring programs.

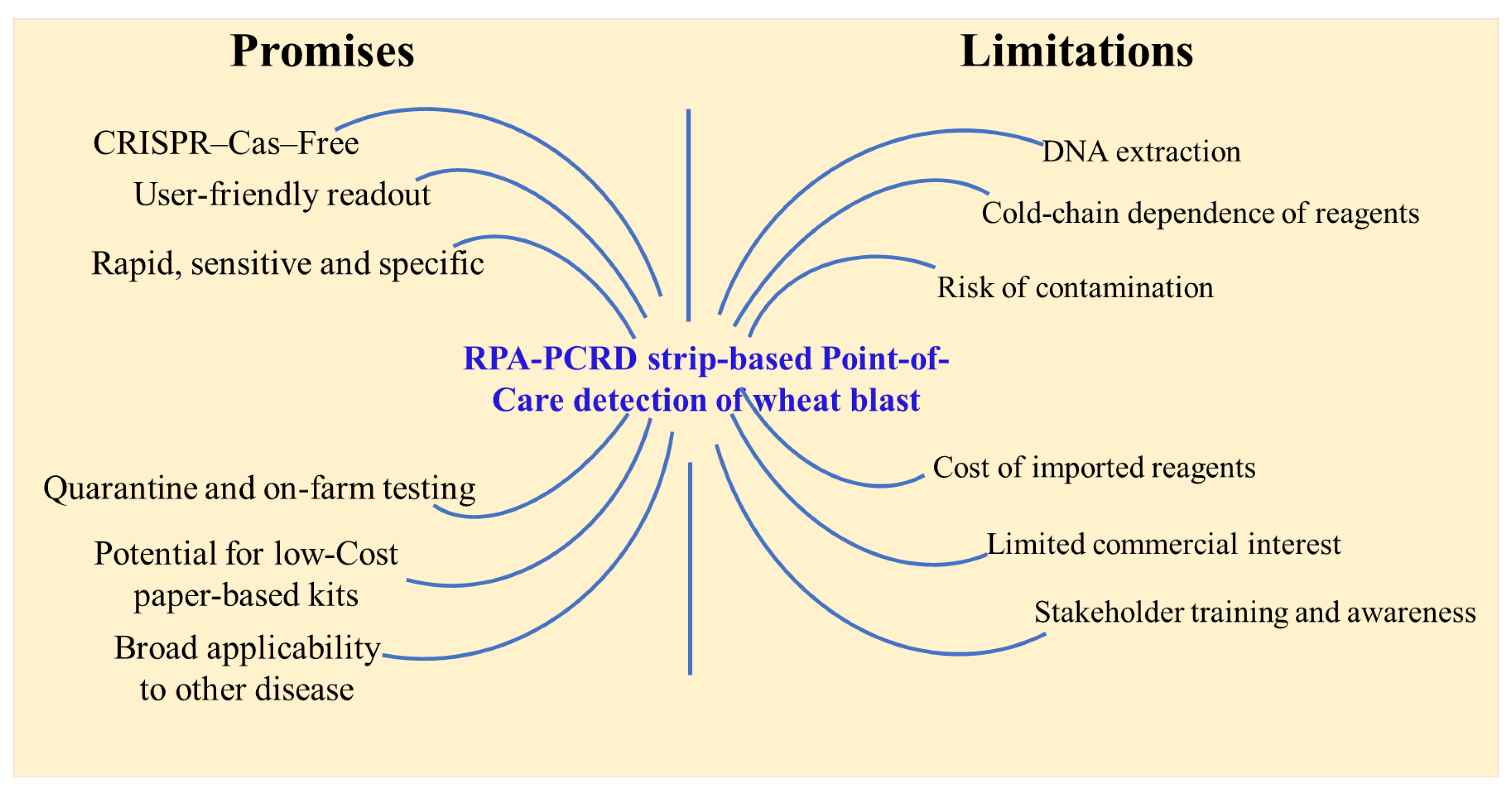

A defining advantage of the developed RPA-PCRD assay is its independence from CRISPR–Cas-based systems, providing a more streamlined and cost-effective diagnostic architecture for low-resource environments. By delivering visually interpretable results within 30 minutes, the platform facilitates immediate, point-of-need decision-making, which is critical for the early containment of wheat blast. The high analytical sensitivity of the assay ensures the detection of low-titer pathogen loads, potentially identifying infections during the asymptomatic or early colonization phases. Because the method bypasses the requirement for thermal cyclers or specialized laboratory infrastructure, it is uniquely suited for decentralized applications, including on-farm surveillance and remote field monitoring. Given that wheat is a cornerstone of global food security, this assay has immediate utility at strategic biosecurity nodes, such as quarantine checkpoints, seed inspection units, and international border facilities. Furthermore, the transition toward a fully paper-based diagnostic format offers a pathway to minimize production costs and enhance large-scale accessibility in developing regions. Beyond its current application, the inherent flexibility of this RPA-based platform allows it to be rapidly adapted for other emerging phytopathogens by simply substituting target-specific primers and probes.

Despite its significant advantages, the commercialization of this assay faces challenges (

Figure 6). Currently, the localized nature of wheat blast outbreaks may limit immediate commercial interest in specific regions. Furthermore, while the platform is field-ready, its large-scale deployment requires further simplification of the DNA extraction protocol and rigorous validation under diverse “real-world” field conditions. As most of the trainees (88%) opined that the kit is user-friendly, to ensure successful adoption, comprehensive training programs are essential to build technical confidence among end-users, including farmers, quarantine officers, and biosecurity policymakers. Logistically, the requirement for cold-chain storage and the importation of specialized RPA reagents may increase operational costs and cause supply chain delays in remote areas. Additionally, the high analytical sensitivity of the RPA-PCRD system necessitates strict adherence to standardized handling procedures to mitigate the risk of aerosol contamination and false-positive results. Nevertheless, this validated diagnostic kit represents a critical advancement in wheat blast management. By enabling real-time genomic surveillance and rapid on-site detection, the assay provides a robust tool to enhance field management and prevent the transboundary spread of the pathogen through international grain trade. Furthermore, the RPA-PCRD platform serves as a modular diagnostic template that can be readily adapted to detect a wide array of phytopathogens by integrating target-specific genomic primers.