1. Introduction

Underground mining operations are complex processes and are among the most hazardous industrial environments where miners constantly face risks of emergencies such as fires, explosions, collapses, and other occupational hazards which can unfold and escalate rapidly [

1]. The last century witnessed more than 726 mining disasters, ≥5 fatalities [

2], in the US mining industry [

3]. Although, significant progress has been made in reducing the frequency of mine fatalities, as the fatality rate decreased by about 50% from 1984 to 2010, due to continuous improvements in technology, training, and regulatory frameworks, nevertheless, fatality rate in 2021 was still four times the industry average in the United States [

4]. Within the first five months of 2006, three incidents in the US mining industry (Sago Mine disaster, West Virginia; Alma No. 1 Mine accident, West Virginia; and Darby No. 1 Mine explosion, Kentucky) resulted in the death of 19 underground coal miners [

5]. These fatal incidents shook the industry and called for thorough analysis and corrective measures. Investigative analyses of these incidents found that in these three incidents, 80% of the miners survived the initial impact but perished during self-escape effort [

6]. The analysis further revealed the lack of training on some critical parameters on self-escape training such as proper usage of self-contained self-rescuers (SCSRs) and escapeway routes [

7,

8] and further highlighted critical gaps in training of miners on decision-making, and situational awareness (SA) during emergency response (NIOSH, 2018; MSHA, 2020). These gaps are critical as these determine the ability of workers to respond effectively, with proper SA and decision-making under stress, to emergencies which can be the difference between survival and disaster. These accidents further stimulated the introduction of Mine Improvement and Emergency Response Act (MINER Act) in 2006 [

9], that requires the mines to have improved training, effectiveness and response time of mine rescue teams. The year 2010 also saw a significantly high count of underground mining fatalities resulting in 48 deaths [

10].

Following these incidents of 2006 and 2010, the Office of Mine Safety and Health Research at National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH) asked for a report examining the essential components of self-escape [

11]. The report formally defined self-escape “the ability of an individual or group of miners to remove themselves from the mine using available resources in the event of a mine escape” and recommended (Recommendation 7) a detailed systematic task analysis to identify the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other personal characteristics (KSAOs), research on modalities, techniques, and protocols for the training miners on these KSAOs, and evaluation of simulation-, and scenario-based trainings for effective miner self-escape training. The need for systematic task analysis and the simulation-based scenario training for KSAOs is the primary motive behind this research.

Mine emergency preparedness and response demand the training on KSAOs encompassing both technical competencies such as hazard recognition, mine layout understanding, ventilation map reading, and SCSR use, and non-technical competencies such as communication, leadership, teamwork, and decision-making under pressure. Safety and self-escape training in the mining industry continues to rely largely on traditional approaches such as classroom instruction, physical drills, and limited field-based scenario exercises. Over the years, these training approaches have provided valuable procedural knowledge but lack assessment of the critical human related factors, situational awareness (SA), and decision making under stress and fall short in replicating the cognitive and psychological pressures of real emergencies. Further, these traditional approaches are increasingly becoming impractical due to high costs, operational constraints, and limited effectiveness (Gao et al., 2019). There is a need to upgrade and modernize the mining safety and self-escape training infrastructure and approach. Immersive techniques have become standard in many high-risk industries and offer a solution to mine emergency training.

The potential of immersive training approaches in mining have been discussed for more than two decades, ranging from early exploratory work [

12,

13,

14] to more recent efforts focused on practical implementation of immersive environments for training [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In mining, however, most immersive applications have focused more on equipment operations and operator’s efficiency, with comparatively little attention given to mine emergency preparedness and self-escape training. Advancements in simulation-based immersive technologies have renewed interest in overcoming the limitations of traditional training approaches. Effective emergency response depends not only on procedural accuracy but also on SA, rapid decision-making, stress management, and coordinated teamwork. Emergency preparedness training in mining therefore requires systems capable of recreating hazardous conditions such as explosions, fires, roof falls, and smoke propagation, in safe and controlled environments, allowing trainees to repeatedly practice high-risk tasks, evaluate their performance, and build confidence without physical danger. Furthermore, such systems should be able to capture expert decision strategies and underlying cognitive processes, measure specific components of SA and KSAOs, and generate detailed performance data to support structured post-training debriefs and personalized feedback. Immersive technologies, including Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR), now enable increasingly realistic modeling of complex mine systems and the replication of sensory and psychological stressors. A training framework that integrates these technologies with performance assessment and adaptive scenario design offers a comprehensive pathway toward improving mine emergency preparedness and self-escape readiness. The VR Mine developed by NIOSH is perhaps the only VR platform specifically designed for underground mining emergencies that has shown potential for self-escape and mine rescue training [

15]. Other related efforts have addressed limited-scope tools such as roof fall hazard assessment [

18] and smoke scenario for emergency training (Xu et al., 2014), but comprehensive immersive framework for emergency training remained limited.

This paper proposes a KSA-aligned Adaptive Immersive Training Framework (AITF) for mine rescue and self-escape readiness that synthesizes principles from VR-based learning, SA theory, KSAO modeling, and cognitive task analysis (CTA) methodology. The proposed framework is designed to provide structured process for analyzing self-escape tasks, identifying cognitive and behavioral training objectives, and translating them into measurable simulation-based learning experiences. By linking human factors research with advanced training technologies, this framework aims to lay a foundation for next-generation miner training for emergency preparedness through enhancing individual self-escape and rescue capabilities.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the conceptual framework that underpins AITF.

Section 3 establishes the theoretical and analytical foundations of the framework by introducing CTA as a foundational method for extracting decision-making demands and failure modes from historical mine emergencies, describing the integration of KSAOs into simulation-based training design, and examining SA and performance assessment as critical mechanisms for evaluating training effectiveness.

Section 4 presents the AITF, synthesizing immersive technologies, adaptive training logic, and human performance metrics.

Section 5 demonstrates the practical implementation of the framework through CTA-driven scenario design using Darby Mine No. 1 incident as a proof-of-concept case study and discusses self-escape competency development and anticipated training outcomes.

Section 6 examines broader implications for mine safety training and policy development. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper with future research directions and opportunities for integrating emerging digital technologies into next-generation miner training systems.

2. Conceptual Framework

The proposed simulation-based training framework, AITF, for mine rescue and self-escape readiness is grounded in the integration of four complementary constructs (i) VR, (ii) SA, (iii) KSAOs, and (iv) CTA. Together, these elements form an evidence-based conceptual foundation for designing, implementing, and evaluating immersive training that strengthens miners’ cognitive and behavioral readiness for emergency conditions.

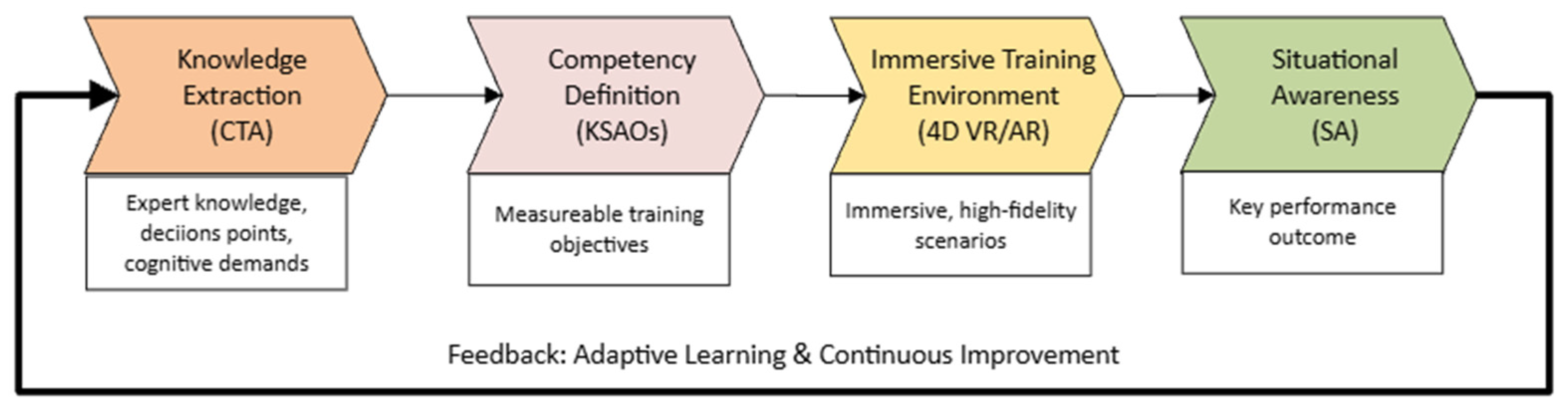

Figure 1 illustrates the interrelationship between these four pillars, showing how CTA informs the definition of KSAOs, which are then operationalized through VR environments designed to foster and measure SA during task performance.

In this framework, CTA serves as the input process that captures domain-specific cognitive demands, KSAOs define the learning objectives, VR provides the training environment, and SA represents the performance outcome to be measured and improved. Data from simulation runs such as behavioral logs, physiological measures, and eye-tracking and process tracing records feeds back into the system to personalize learning trajectories, forming the basis for an adaptive immersive training model. This closed-loop design supports continuous improvement in both the trainee’s competence and the instructional system itself.

Within the AITF, CTA provides the methodological foundation for extracting the expert knowledge, mental models, and decision heuristics that underpin effective emergency performance. CTA can be an involved task utilizing structured interviews, think-aloud protocols, and incident reconstructions, etc. [

21]. Through these, CTA identifies the critical cognitive actions and decision points within self-escape tasks. This information helps define and guide the development of VR training scenarios and the feedback mechanisms. CTA further helps bridging the gap between qualitative expertise and quantitative performance metrics, enabling iterative refinement of both simulation fidelity and instructional design.

Self-escape from an underground mine emergency goes beyond basic survival skills, mental abilities, and physical capacities and requires a particular set of competencies, collectively called the KSAOs, and have been emphasized in literature [

11,

22,

23]. The AITF is designed to target the KSAOs essential for competent and resilient performance in the context of mine rescue and self-escape readiness. KSAOs provide the foundation for defining measurable learning outcomes that bridge the gap between cognitive task demands and training system design as implemented within the AITF.

VR provides the working and unifying platform for this training framework. VR offers a controlled yet realistic environment for replicating complex, hazardous, or rare events that cannot be safely recreated in the field. In the context of underground mining, VR enables trainees to experience the visual, auditory, and spatial cues associated with emergency scenarios such as low visibility, disorientation, and constrained movement without physical risk. Previous research in aviation, medicine, and process industries demonstrates that immersive simulations enhance decision-making accuracy, reduce training time, and improve long-term skill retention [

24,

25]. When appropriately designed, VR scenarios facilitate experiential learning cycles that integrate perception, reflection, and adaptation, allowing miners to engage in repetitive, feedback-driven practice of emergency response actions.

Endsley’s (1988a) three-level model of SA encompassing perception, comprehension, and projection serves as the cognitive foundation of the proposed framework. Effective self-escape and rescue operations depend on miners’ ability to (1) perceive environmental cues such as presence of smoke, gas monitor readings, or airflow direction, (2) comprehend their implications for hazard evolution, and (3) project the likely outcomes of different escape decisions such as best escape route. In immersive simulations, SA can be objectively assessed through performance indicators such as gaze behavior, attention allocation, and decision timing. VR environments also allow controlled manipulation of scenario variables (e.g., visibility, noise, or communication failures), enabling the measurement and enhancement of SA across a range of difficulty levels.

3. Theoretical and Analytical Foundation

This section establishes the theoretical and analytical foundations that inform the design of the AITF. It introduces CTA as a systematic method for extracting cognitive demands, decision points, and failure modes from mine emergency scenarios, and discusses how KSAOs can be integrated into simulation-based training through scenario designs. The section further examines SA and performance assessment as essential components for training effectiveness and adaptive learning in immersive environments. Together, these foundations provide the theoretical basis for translating historical accident data and human performance requirements into structured, measurable training interventions.

3.1. Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA) as a Design Lens

One critical aspect of any safety related training program is to ensure that the recipients are trained to recognize the safety hazards and can self-escape. This can be achieved effectively by exposing the recipients to the safety lapses in the past incidents to evaluate their SA and ability to self-escape in similar situations. This can be achieved through a task analysis of past mining emergencies. Task analysis refers to a systematic inquiry into an activity to understand how it is performed. It involves breaking down a task into smaller and more manageable steps or subtasks to understand it completely. There are multiple techniques used for tasks analysis, such as hierarchical task analysis (HTA) and cognitive task analysis (CTA). HTA refers to a systematic procedure to identify the steps or tasks and subtasks associated with a process. It includes subtasks, task hierarchy, and task sequence required to complete a common goal. NIOSH [

26] researchers utilized an HTA for the core competency analysis and identified 21 critical task clusters (activities), along with 37 general tasks (competency areas) and 75 subtasks (KSAs) critical to self-escape roles. For example, in a major activity of “Communicating Nonverbally” the HTA found one competency area (nonverbal communication techniques and technologies), and the three KSAs (know tapping codes, use text-based messaging, and know hand and cap lamp signals).

CTA, though very similar to HTA, focuses more on the cognitive factors such as decision-making and judgment, memory, attention and attention span, etc. and refers to a set of methods that can be used to identify and understand the mental processes during task operations [

28,

29]. Though both the HTA and CTA work similarly in breaking down a task into steps, however, the CTA provides advantages in terms of training and expertise development on a task. It is especially useful when comparing the expert performance to the novices and can be used for designing training programs. For these reasons, our model prefers CTA over HTA.

When applied to underground mining, a high-risk complex environment, CTA can systematically uncover the decision-making processes, perceptual cues, and mental models that underlie human performance. When applied to historical mine accident investigations, CTA serves as a bridge between descriptive accident narratives and prescriptive training design. By identifying the cognitive demands and breakdowns that contributed to failures in emergency response or self-escape, CTA reveals the latent training needs that conventional task analyses often overlook.

In this framework, CTA focuses on reconstructing situational contexts, decision sequences, and information flow during critical moments of past mine emergencies. The process begins with a detailed review of investigation reports such as conducted by Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), and other relevant information such as rescue operation logs, ventilation plans, and eyewitness testimonies. These information sources are used to map the chain of events and highlight key decision junctures such as when miners recognized hazards, interpreted environmental cues (e.g., smoke, airflow, communication loss), or selected escape routes under uncertainty. Through this reconstruction, it becomes possible to infer the knowledge and perceptual cues that experienced miners relied upon and maybe the misconceptions or attentional lapses that led to errors.

The CTA outputs are organized into three analytical layers:

Task Decomposition: Breaking down the self-escape or rescue process into discrete cognitive and physical tasks, such as hazard recognition, gas readings interpretation, and use of SCSR.

Decision Requirements: Identifying critical decision points and the information needed to make them effectively under time pressure.

Error and Resilience Patterns: Classifying where and how decisions failed, and how adaptive responses or improvisations contributed to survival in some cases.

Keeney et al., [

30] applied CTA to self-escape procedure for mining. Their application of CTA is detailed but generic and focuses on general self-escape tasks. The researchers went through a detailed CTA process and investigated four critical roles such as a mining crew member, escape group leader, responsible person, outby worker during emergencies.

Applying CTA to past accidents such as the 2006 Darby Mine explosion and the Sago Mine disaster provides empirically grounded insights into the mental demands of emergency self-escape. For instance, in both events, survivors’ accounts reveal challenges in orientation loss, ventilation change detection, and team coordination under degraded communication. We think that applying CTA to previous mine incidents will help with high-fidelity scenarios for the training purposes as these findings will directly inform the scenario logic and training objectives in the AITF, ensuring that virtual simulations replicate authentic cognitive challenges rather than idealized procedures. By embedding CTA-derived insights into VR modules, the framework promotes the development of situation assessment skills, adaptive decision-making, and resilience under uncertainty, all of which are essential for effective self-escape and mine rescue readiness.

3.2. Integration of KSAOs in Simulation-Based Training

Based on the National Research Council’s report [

11], NIOSH initiated studies to get an insight into self-escape competency teaching [

31] and assessment at the mines [

23] and training. Based on these documents, the findings are categorized into four broad, interdependent domains, as KSAOs, given in

Table 1. The KSAO construct provides a structured taxonomy for identifying the human capabilities essential to mine emergency response. Building on frameworks developed by NIOSH [

22,

23] and prior mine rescue studies [

32] the relevant KSAOs for self-escape are detailed in

Table 1.

Further, [

27] identified the nine core self-escape competencies (SECs) for the rank-and-file coal mine workers and discussed. The researchers further elaborated the competency tasks into more detailed sub tasks and made suggestions for training. The present research is focused on designing a training framework to achieve these and other self-escape competencies through an adaptive immersive training system. By aligning training objectives with these KSAOs, the framework ensures that simulation design is outcome-driven and directly linked to measurable competencies. The SECs in the context of AITF are given in

Table 2. Though the AITF is designed to include measurements of some of the other traits (Os), but the training does not intend to develop any Os. Therefore, the AITF focuses only on KSAs, that can be developed through immersive approaches in a simulated environment. As can be argued, the ability to quickly done an SCSR is best learned and trained in a realistic environment with real equipment, so we will leave out the training and recommend using the traditional approaches to training such skills and abilities.

To note, NIOSH researchers omitted other abilities “Os” in their report, but those are included here for the completion purposes.

The CTA findings guide the alignment of these KSAOs with specific cognitive and behavioral requirements observed in historical accident scenarios. For instance, CTA of the Darby Mine and Sago Mine events highlighted failures in ventilation map interpretation and misjudgment of airflow cues, indicating deficiencies in both knowledge of ventilation principles and situational awareness abilities. A simple CTA of the Darby Mine No.1 incident is presented in

Section 5 of this paper. Similarly, disorientation during smoke-filled evacuations underscores the need for skills in spatial navigation and psychomotor proficiency in deploying rescue devices.

This mapping ensures that every simulated scenario within the AITF targets explicit KSAs, focusing the competency-based learning. Each module can then be designed to emphasize different combinations of KSAs and relevant assessment protocols. KSAs integration also provides a framework for performance assessment and adaptive feedback within immersive environments. Trainee performance data, such as navigation efficiency, response time, and cue recognition accuracy, are continuously captured to evaluate the attainment of targeted KSAOs. The feedback from the post-training analysis then adjust task complexity or scenario intensity, in the future scenarios, to maintain optimal learning conditions. Such adaptive assessment not only reinforces learning outcomes but also enables the development of individualized training profiles, helping instructors identify specific cognitive or behavioral gaps. Over time, these data support the creation of KSAO competency maps across the workforce, informing curriculum updates, refresher courses, and readiness evaluations.

3.3. Situational Awareness (SA) and Performance Evaluation

SA represents one of the most critical cognitive and non-technical factors contributing towards process safety, decision-making, and performance in high-risk environments such as underground mines. It is one of the major factors in human related errors in major disasters in coal mining and many industries. Human factors, for example, were accounted for about 98% of coal mining accidents between 1980 to 2000 in Chinese coal mines [

33]. Loss of SA is identified as a contributing factor in mine emergencies and fatalities as hinted in the past mine incident analyses such as the Darby, Sago, and Upper Big Branch disasters as well. The same is generally true for other high-risk industries such as aviation, oil and gas, medicine, etc. Hence, developing and maintaining SA must be a central objective of self-escape and rescue training programs.

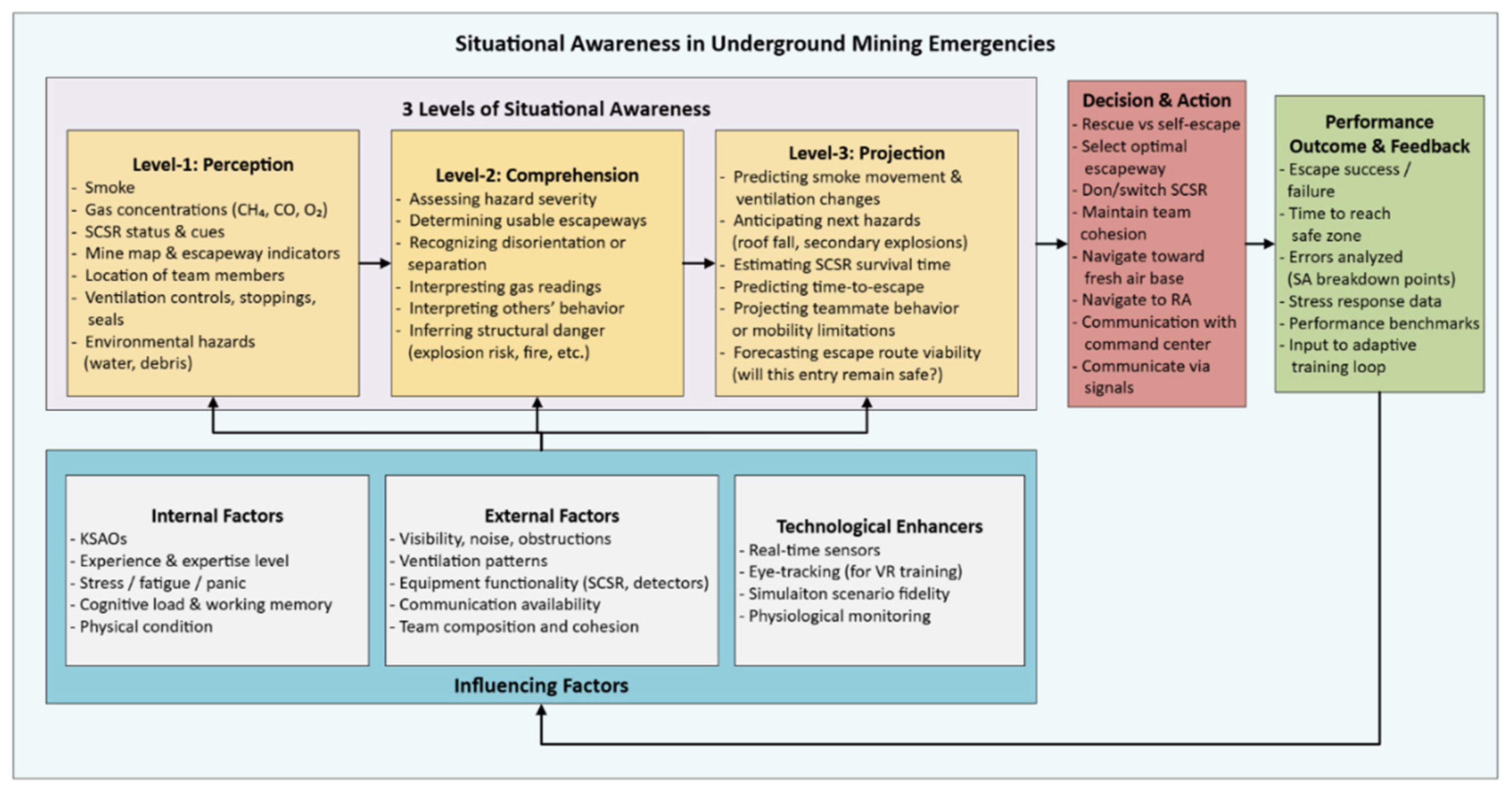

Simulation-based environments provide an effective medium for developing SA by replicating the cognitive demands of underground emergencies without associated risk. As previously noted by Endsley [

25], SA involves three progressive levels: (1) perception of environmental elements, (2) comprehension of their meaning, and (3) projection of their future status. In the context of miner self-escape, these levels correspond to a miner’s ability to detect environmental cues (e.g., smoke, air velocity, temperature changes), interpret their implications for safety, and anticipate evolving hazards to Understanding spread of smoke/contaminants. For the AITF, the SA model adapted for miner self-escape training is presented in

Figure 2.

Within the proposed AITF, SA is measured through a multimodal approach combining:

▪ Behavioral metrics: Response times, navigation efficiency, and sequence adherence in evacuation tasks.

▪ Eye-tracking and gaze analysis: Identification of visual scanning patterns, fixation duration on critical cues (e.g., directional markings, hazard indicators), and shifts in attention during dynamic scenarios.

▪ Physiological measures: Heart rate variability and stress indicators that may influence perceptual and cognitive performance.

▪ Post-scenario assessments: Structured debriefs and SAGAT (Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique) [

34,

35] queries to assess recall and comprehension of environmental elements.

This triangulated measurement approach provides a comprehensive profile of how well trainees perceive and interpret their surroundings, make decisions under uncertainty, and sustain attention through the progression of emergency tasks. The AITF is perceived as an adaptive system where future scenarios are adjusted based on the performance assessment. For instance, when eye-tracking data reveals inattentiveness to key environmental cues, the system can provide feedback through visual or auditory prompts, encouraging trainees to redirect attention. This adaptive approach supports incremental development of SA, enabling trainees to progress from basic perception (e.g., recognizing smoke patterns or directional lights) to higher-order comprehension and projection skills (e.g., anticipating how ventilation changes affect escape routes). Over time, repeated exposure to these adaptive scenarios enhances cognitive resilience and situational fluency.

Within the proposed framework, situational awareness serves as both a performance indicator and a training outcome. Performance evaluation is not limited to procedural correctness but extends to how effectively miners maintain SA across complex and evolving scenarios. This dual role of SA provides a robust foundation for evaluating overall readiness and for tailoring individualized training paths. By integrating SA assessment into the performance evaluation process, trainers can identify specific cognitive weaknesses such as tunnel vision, poor cue prioritization, or over-reliance on routine behavior and design targeted interventions. Furthermore, longitudinal tracking of SA metrics allows organizations to monitor improvements over time and quantify the impact of immersive training interventions on operational safety performance.

4. Adaptive Immersive Training Framework (AITF)

The proposed AITF represents the core contribution of this research. AITF offers a structured, data-driven system for improving miners’ self-escape performance through adaptive, simulation-based learning. Grounded in Kelley [

35] definition of adaptive training, the AITF modifies the training environment based on learner performance, enabling personalized progression and targeted skill refinement. Adaptive training refers to a learning technique where task difficulty is gradually and continuously adjusted based on trainee’s performance. This approach is better compared with the existing fixed training systems where all the miners receive the same training without regard to their previous level, or mastery of one skill. The framework integrates immersive technologies, such as VR/AR, with real-time performance analytics to build cognitive, procedural, and affective competencies essential for underground emergency response.

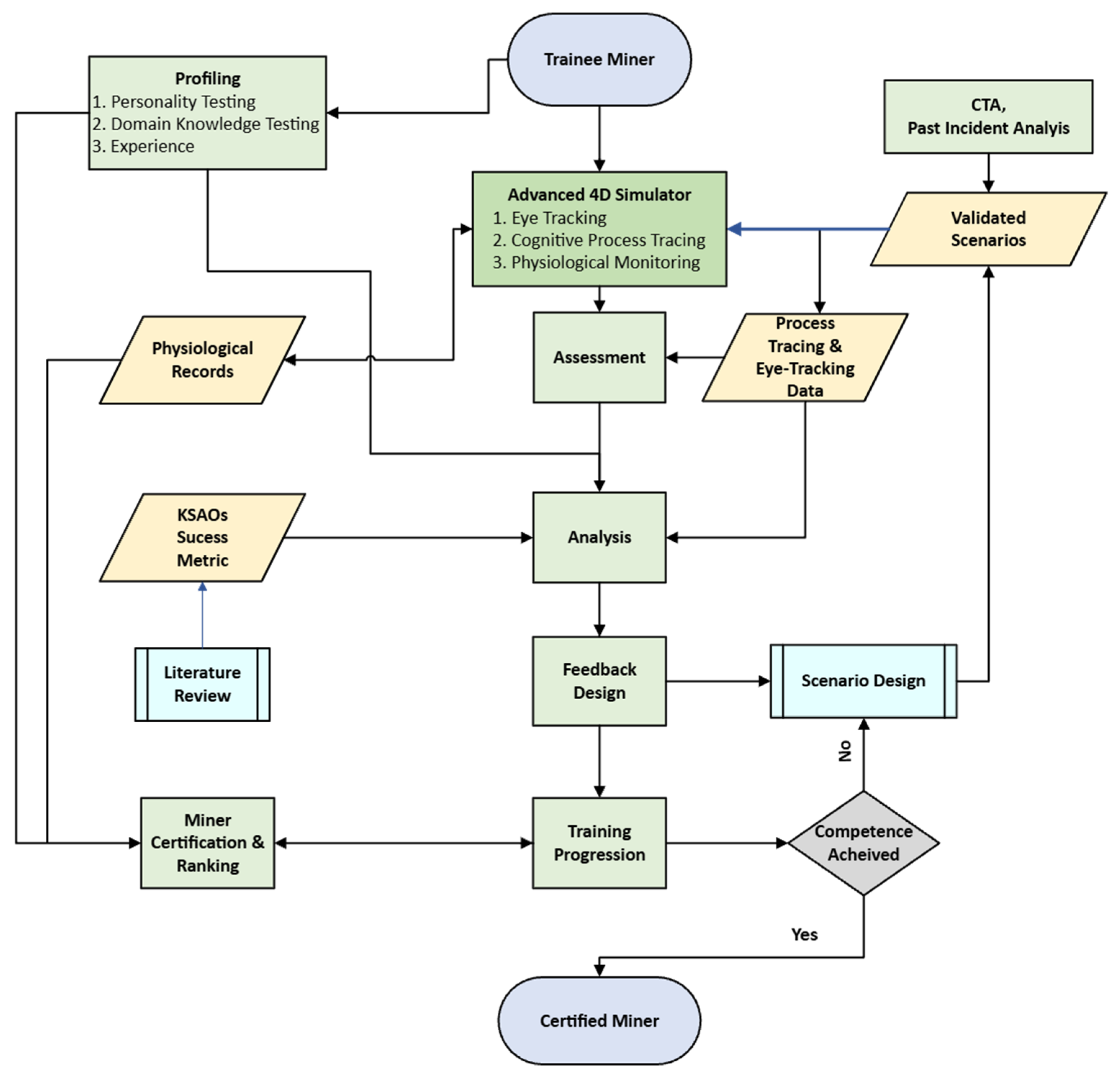

Figure 3 schematically illustrates the AITF architecture and training flow.

The AITF leverages immersive VR environments to replicate, as scenarios, realistic mining emergencies such as methane explosions, structural collapses, electrical hazards, or toxic gas releases, without exposing participants to actual risk. These environments can further simulate the physical, perceptual, and psychological stressors characteristic of underground mining, such as low visibility, smoke, auditory distractions, and communication breakdowns. Each scenario-based simulation focuses on competency development, SECs, allowing miners to practice critical self-escape tasks such as identifying safe escapeways, navigating through low-visibility and smoke-filled passages, and coordinating with teammates (

Table 2). Scenarios are customized to the trainee’s expertise level, advancing from basic procedural drills to complex decision-making under uncertainty.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the training sequence begins with baseline profiling of the trainees using psychological, knowledge, and technical assessments. Personality traits (e.g., stress tolerance, risk perception), domain knowledge, and psychomotor capabilities in using the equipment or prior experience in handling the similar scenarios are assessed to establish individualized training profiles. This builds a personal profile database of the trainees.

Afterwards, the trainee engages in an immersive scenario, in an advanced 4D simulator integrated with eye-tracking and physiological monitors for detailed process tracing. A distinguishing feature of AITF is the integration of eye-tracking and process tracing tools for cognitive performance assessment. Eye-tracking enables quantification of visual attention, scanning strategies, and cognitive load, revealing patterns that differentiate novice and expert miners [

37,

38,

39]. Coupled with verbal protocols, post-simulation debriefs, and physiological monitoring (e.g., heart rate), this multimodal data provides a comprehensive understanding of the trainee’s SA [

39], communication process [

40], and stress response. In the simulator, adaptive logic continuously evaluates real-time performance metrics through process tracing such as reaction times, decision accuracy, communication patterns, and compliance with safety procedures. Based on this assessment, feedback is designed that adjusts scenario parameters such as task complexity, time constraints, and feedback frequency. Training progresses gradually to more involved tasks enabling mastery of operations. These cognitive markers are used to identify performance gaps and tailor corrective feedback for progressive training. For instance, a miner exhibiting tunnel vision during hazard detection scenarios might receive specific visual search exercises, while one displaying delayed decision-making could be assigned scenarios emphasizing time-critical actions. This data-informed adaptivity ensures that each trainee develops both technical proficiency and cognitive resilience under stress.

Performance evaluation within the AITF is grounded in SA and competency-based learning. The framework measures the three hierarchical SA levels defined by Endsley [

25] as (i) perception of environmental cues, (ii) comprehension of their meaning, and (iii) projection of their future status. The SA is measured using performance metrics such as hazard detection accuracy, response time, communication clarity, and following the escape protocols, etc. An adaptive feedback mechanism is designed to transform the assessments into interventions focused on competency development. The framework is designed as a graduated outcome-based system benchmarked against required or defined competency milestones. The iterative feedback loop consisting of assessment, adaptation, and retraining ensure progressive skill acquisition and readiness for real-world emergency conditions.

5. Operationalizing the AITF

This Sections integrates the practical implementation of the proposed framework by outlining the methodological approach used to operationalize the AITF and demonstrating the application of CTA-driven scenario design through a case study of the Darby Mine No. 1 incident. This case study is presented as a proof of concept, illustrating how historical accident analyses can be systematically translated into immersive training scenarios for mine self-escape and emergency preparedness.

5.1. Methodological Approach for AITF Implementation

The proposed AITF follows a structured design approach that iteratively integrates theoretical constructs with empirical validation. As explained in

Section 2, it includes task analysis, competency mapping, immersive scenario design, and testing and performance evaluation. The process is structured around four interlinked phases: (1) knowledge elicitation through CTA of historical incidents, (2) competency mapping into KSAOs, (3) immersive scenario design using VR environments, and (4) iterative validation through behavioral performance assessment.

Phase-I employs CTA to extract expert cognitive processes and decision strategies from historical mining accidents and field operations. Accident investigation reports from MSHA and NIOSH are analyzed to identify key cognitive demands, perceptual cues, and decision breakdowns during emergency self-escape. These insights are coded into a structured task hierarchy that highlights both procedural and cognitive bottlenecks, forming the foundational data for simulation scenario design. A general process for the CTA involves extracting factual events and decision points from the available investigation material such as investigation reports, voice and communication logs, data sheets, and post-incident interviews. Then every involved task is systematically broken down into smaller steps to further describe factual events, perceptual cues and decision points in each step. This is the primary step in CTA and requires careful deliberation, thoroughness, and judgment. Inclusion of the subject matter experts (SMEs) can help this process further. There are multiple resources available that discuss the CTA procedure in more detailed such as [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45] and the interested reader is encouraged to these resources for further details.

In Phase-II, the outputs from CTA are mapped onto the KSAOs framework. This step converts qualitative cognitive insights into measurable learning objectives. For instance, knowledge domains include mine layout, emergency communication, and use of SCSRs. Skills are defined in terms of decision-making under uncertainty and navigation in low visibility, while abilities emphasize perceptual accuracy, spatial reasoning, and stress management. The inclusion of Other Attributes (Os) e.g., motivation, personality traits, and teamwork orientation, etc. allows the framework to capture non-technical competencies crucial for real-world performance, although the AITF is not intended to develop these attributes. This structured KSAO mapping ensures that the subsequent simulation design directly aligns with measurable training outcomes.

In Phase-III, KSAO-based learning architecture, immersive simulation environments are developed within VR/AR platforms. Scenarios replicate emergency conditions such as methane explosions, ventilation failures, or blocked escapeways, allowing trainees to engage in high-stress, decision-rich situations. Each scenario is configured with embedded data collection systems to capture behavioral and cognitive performance, including eye-tracking patterns, decision logs, and physiological indicators such as heart rate and stress response.

Phase-IV involves performance evaluation assessing SA as indicators of cognitive readiness. Data from eye-tracking, physiological sensors, and performance metrics are triangulated to assess the trainee’s decision-making efficiency and adaptability. Post-simulation debriefs and self-assessment pre-, post surveys complement quantitative data, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the learning process. These evaluations are iteratively fed back into the framework, refining both the scenario content and the pedagogical design in a continuous improvement cycle.

5.2. CTA-Driven Scenario Design: Darby Mine No. 1 Case Study

We applied CTA to the Darby Mine No. 1 explosion that happened on May 20, 2006. This CTA is based on retrospective analysis using the MSHA report of investigation [

8] and internal review of MSHA’s action [

7]. The objective is demonstrative only to show how CTA translates factual accident data into specific training requirements and simulation scenarios within the AITF. Using available investigation materials we reconstructed the event timeline, identified key decision points and perceptual cues, and mapped observed error modes to KSAOs gaps. The resulting CTA tables (

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5) present (a) a condensed event timeline, (b) a structured analysis of cognitive failures and KSAOs implications, and (c) a direct mapping from CTA findings to AITF-ready simulation scenarios respectively. The intent is not forensic re-examination but to illustrate a precise, evidence-based workflow for scenario creation and measurable training objectives within the AITF. Further, it does not add new factual details beyond those source materials. A general process is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Table 3 presents a condensed version of the timeline for this incident.

The detailed breakdown of cognitive elements, error modes and the KSAOs mapping is given in

Table 4.

CTA of this incident identified recurrent cognitive failures, hazard recognition lapses, ventilation/vent map miscomprehension, degraded SA under smoke, and team coordination breakdowns. Each of these indicates concrete training targets for AITF scenario design.

These scenarios are built directly from the CTA findings.

Table 5 gives three of the possible scenarios to be implemented in the AITF. Each scenario has key learning objectives and the required VR features along with the adaptive variables and performance metrics for logging, assessment, and debriefing. These scenarios are intentionally kept simple and are produced as samples for demonstration purposes only. These can be adjusted with more objectives, VR features, and adaptive variables.

The metrics listed in

Table 5 are measurable with current VR, eye-tracking, and physiological logging systems and align with the AITF performance-assessment module (SA measures, donning time, decision accuracy). Post-scenario debriefs would then use probes (e.g., ask trainees what cues they noticed, why they chose a route) to expose cognitive processes and reinforce corrective strategies. These debriefs complete the AITF adaptive loop by using behavioral data to tailor follow-on training.

5.3. Self-Escape Competency Development

The ultimate objective of AITF is to develop self-escape competencies. To develop competencies in self-escape, training must be both comprehensive and realistic. AITF provides a valuable tool for developing and assessing these competencies. AITF offers simulated scenarios that mimic real-world mine emergencies, with trainees required to navigate dynamic, unpredictable conditions. Further, it offers performance metrics derived from simulation data (e.g., time to escape, adherence to escape routes, use of personal rescue devices) that allow for objective evaluation of competency. Data such as time, distance, and errors can be visualized and aggregated for debriefing, providing trainers with valuable insights into areas that require improvement (Bauerle et al., 2016). Furthermore, competency development requires repeated exposure to different emergency scenarios. Trainees should be provided with opportunities to perform multiple self-escape exercises, receiving feedback after each session to enhance learning. The use of simulation log data, as noted by Bauerle et al. [

45] enables targeted, flexible feedback, which is crucial for reinforcing correct behaviors and addressing errors. Self-escape scenarios should include decision points where miners must choose between different escape routes or safety measures, allowing them to practice decision-making under pressure. These scenarios can be further enhanced with time constraints or the introduction of unexpected variables (e.g., sudden environmental changes, blocked paths) to simulate the uncertainty of real emergencies [

46]. AITF offers repeatable simulations with adjusted decision points for competency development. Furthermore, since many self-escape scenarios involve group coordination, training should include team-based exercises. Simulation systems should allow for collaboration among trainees, where they can practice communication, coordination, and support for one another during the escape process [

47]. Scenarios within AITF can be developed to promote team-based escape and emergency response. Through these strategies, AITF offers miners with the necessary skills, decision-making abilities, and confidence to effectively execute self-escape procedures in real-world emergencies, ultimately improving their safety and survival rates.

6. Discussion and Implications

This study introduced a simulation-based training framework for mine rescue and self-escape readiness by integrating principles and technology of VR, SA, KSAOs, and CTA. The proposed AITF offers a systematic, CTA-based, and data-informed approach to assess and enhance miners’ decision-making and emergency response capabilities during underground mining emergencies. AITF represents a transformative step towards the next generation of miner training for self-escape integrating simulation science, human factors engineering, and mining safety research.

Traditional mine-safety training has relied heavily on regulatory compliance and procedural repetition. While these methods establish foundational awareness and have been useful in routine procedures, they often fail to develop the cognitive adaptability required in dynamic, high-stress scenarios. The AITF framework addresses this gap through immersive scenario-based simulations that mirror the complexity of real emergencies. Through continuous assessment of performance indicators through process tracing such as eye-tracking, stress response, and decision accuracy, the framework enables iterative learning and measurable competency growth. This transition from prescriptive to performance-based learning marks a pivotal shift in training philosophy for the mining sector.

Training applications in the AITF are based on immersive training scenarios that closely represent emergency conditions in underground mines. These scenarios are designed using insights from a task analysis process of historical accident data and will replicate key tasks such as decision-making challenges associated with events such as gas explosions, smoke propagation, gas leakages, and/or blocked escapeways. Each simulation will consist of multi-stage tasks requiring perception, decision, and action cycles under dynamic conditions. For example, a miner may be required to:

Detect an early warning signal (e.g., gas alarm),

Interpret mine environment data (e.g., gas readings),

Select an appropriate escape route based on mine map, and

Execute evacuation protocols while maintaining communication with team members.

A distinguishing feature of this AITF is feedback-based scenario fidelity which will vary depending on the trainee’s proficiency level, enabling the AITF to progress from procedural drills to complex, time-critical, and team-based challenges. Integration of eye-tracking and physiological sensors, along with other process tracking methods [

34,

35,

48] during these simulations will generate data to assess attention distribution, cognitive load, and emotional regulation. During training sessions, process tracing data including eye-movement patterns, decision timelines, physiological stress markers, and communication metrics will be collected and analyzed. These analyses will interpret this data to adjust subsequent training content for a progressive self-escape competency development.

The effectiveness of the AITF will be evaluated through a combination of quantitative performance metrics and qualitative assessments, benchmarked against pre-training and post-training evaluations. Key performance indicators (KPIs) will include SA scores, decision-making accuracy, response efficiency, and stress cognitive load indicators. Collectively, these metrics will quantify learning gains across cognitive, behavioral, and psychomotor domains, offering a holistic assessment of self-escape competency.

It is anticipated that implementation of the AITF will yield significant improvements in both individual readiness and organizational safety performance. At the individual level, miners trained under the framework are expected to demonstrate higher levels of SA and decision accuracy, improved stress tolerance and confidence during emergencies. Similarly, at the organizational level, adoption of the AITF can support reduced incident rates through enhanced emergency competence and improved safety culture by emphasizing proactive preparedness.

By linking immersive technologies with adaptive learning principles and cognitive assessment, the framework establishes a reproducible model that can be adopted by mine operators, training academies, and regulatory bodies.

The findings and framework presented here carry several policy and implementation implications such as regulatory training programs, miner certification pathways, and workforce development. Regulatory agencies such as MSHA and NIOSH could incorporate adaptive simulation-based modules within Part 48 and mine rescue training curricula to complement classroom and field-based exercises. The SA and KSAO-based evaluation protocols can be standardized for benchmarking of cognitive readiness across operations and evidence-based miner certifications. Finally, the integration of immersive training technologies with equipment simulators and other training programs can lead to workforce development in the mining sector.

The mining industry stands at a crucial intersection of technological innovation and workforce evolution. As automation, electrification, and digitalization reshape the mines of the future, traditional safety paradigms must evolve accordingly. The AITF framework promotes a data-driven culture of preparedness, where training outcomes are continuously monitored, refined, and aligned with both operational needs and human performance insights. This approach not only strengthens self-escape and rescue readiness but also supports the broader vision of intelligent mining systems operations that are safe, adaptive, and resilient.

7. Conclusion and Future Outlook

The AITF offers a solution to fill the critical training gaps in the existing traditional approaches to prepare miners for underground emergencies. Integrating KSAOs into simulation-based training transforms the conventional training paradigm from rule-based instruction to capability-based development. It ensures that miners are not merely compliant with regulatory standards but are equipped with the cognitive adaptability, teamwork competence, and situational awareness necessary to respond to mining emergencies and self-escape.

Looking forward, the continued integration of AI, machine learning, and digital twin technologies into simulation-based training holds immense promise. These tools can enable predictive modeling of trainee performance, real-time scenario adaptation, and enhanced visualization of underground emergencies. Future extensions could include integration with AI-driven adaptive engines, digital twins of mine operations, and remote multi-user VR systems for collaborative training. Such developments would allow scalable implementation across diverse mining operations and regulatory environments, strengthening preparedness industry-wide.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| AITF |

Adaptive immersive training framework |

| CTA |

Cognitive task analysis |

| HTA |

Hierarchical task analysis |

| KSAOs |

Knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics/attributes |

| MSHA |

Mine safety and health administration |

| NIOSH |

National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health |

| RA |

Refuge alternative |

| SA |

Situational awareness |

| SAGAT |

Situational awareness global assessment technique |

| SCSR |

Self-contained self-rescuer |

| SECs |

Self-escape competencies |

| SME |

Subject matter expert |

| VR/AR |

Virtual reality/augmented reality |

References

- Donoghue, A. M. Occupational health hazards in mining: an overview. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2004, vol. 54(no. 5), 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC-NIOSH Mining, Mining Disasters: 1839 to Present. 14 Apr 2025. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NIOSH-Mining/MMWC/MineDisasters/Table#:~:text=Mining%20Disasters:%201839%20to%20Present%20Note:%20A,fatalities%20that%20are%20part%20of%20OSHA%20records.

- Stafford, A.; Brown Requist, K. W.; Lotero Lopez, S.; Gordon, J.; Momayez, M.; Lutz, E. Underground Mining Self-Escape and Mine Rescue Practices: an Overview of Current and Historical Trends. Min Metall Explor 2023, vol. 40(no. 6), 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH Mining, Number and rate of occupational mining fatalities at underground mining locations by year, 2020 - 2022. 20 Dec 2024. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NIOSH-Mining/MMWC/Fatality/NumberAndRate?StartYear=2020&EndYear=2022&SelectedOperatorType=&SelectedMineType=1#.

- MMWR, “Underground Coal Mining Disasters and Fatalities --- United States, 1900--2006,” Jan. 2009. Accessed: Apr. 14, 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5751a3.htm.

- Kowalski-Trakofler, K. M.; Vaught, C.; Brnich, M. J.; Jansky, J. H. A Study of First Moments in Underground Mine Emergency Response. 2010, vol. 7(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, Sickler. Internal Review of MSHA’s Actions at the Darby Mine No. 1; Kentucky Darby LLC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Light, T. E. “REPORT OF INVESTIGATION: Fatal Underground Coal Mine Explosion, May 20, 2006 Darby Mine No. 1 Kentucky Darby LLC Holmes Mill, Harlan County, Kentucky ID No. 15-18185,” 2007. 10 Dec 2025. Available online: https://www.msha.gov/sites/default/files/Data_Reports/FTL06c2731_0.pdf.

- Mine Safety and Health Adminstration, MINER ACT. 2006. Available online: https://arlweb.msha.gov/MinerAct/2006mineract.pdf.

- US DOL; US Department of Labor. Mining Deaths Rise in 2010.

- National Research Council. NRC, Improving Self-Escape from Underground Coal Mines; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafrik, S. J.; Karmis, M.; Agioutantis, Z. Methodology Of Incident Recreation Using Virtual Reality. In Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kizil, M. S.; Joy, J. What can virtual reality do for safety; University of Queensland: St. Lucia QLD, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McMlarnon, D. J.; Denby, B. VR-Mine - A Virtual Reality Underground Simulation System (Application to Mine Safety and Training); Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bellanca, Jennica L. Usability of Collaborative VR Mine Rescue Training Platform. In Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, R. A.; Conrad, P. W.; Hart, J.; Rosenthal, S. IMPROVING MINE HEALTH AND SAFETY TRAINING THROUGH THE DEVELOPMENT OF MONTANA TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY’S MINE HEALTH AND SAFETY TRAINING PROGRAM - SME Annual Conference 2023; Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stothard, P.; Squelch, A.; Stone, R.; Van Wyk, E. Towards sustainable mixed reality simulation for the mining industry; Transactions of the Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Mining Technology, Oct 2019; vol. 128, no. 4, pp. 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isleyen, E.; Duzgun, H. S. Use of virtual reality in underground roof fall hazard assessment and risk mitigation. Int J Min Sci Technol 2019, vol. 29(no. 4), 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A.; Frimpong, S. “A Simulation-Based Training Framework for Mine Rescue and Self-Escape Readiness,” in SME Annual Meeting 2025, Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration, 2025. Accessed: Nov. 29, 2025. Available online: https://onemine.org/documents/a-simulation-based-training-framework-for-mine-rescue-and-self-escape-readiness-sme-annual-meeting-2025.

- Xu, Z.; Lu, X. Z.; Guan, H.; Chen, C.; Ren, A. Z. A virtual reality based fire training simulator with smoke hazard assessment capacity. Advances in Engineering Software 2014, vol. 68, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, M. J.; Wiggins, S.; Reynolds, K. D.; Berger, J. L.; Hoebbel, C. L. Cognitive Task Analysis of Miner Preparedness to Self-Escape from Mine Emergencies. J Organ Psychol. 2018, vol. 18, pp. 57–78. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6390287/.

- Hoebbel, CL; Bellanca, JL; Ryan, ME; Brnich, MJ; Advancing self-escape training: a needs analysis based on the National Academy of Sciences report ‘improving self-escape from underground coal mines; NIOSH. Pittsburgh PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2023-134”. Jun 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, EJ; Peters, RH; Kosmoski, CL; Enhancing Mine Workers’ Self-escape by Integrating Competency Assessment into Training; NIOSH. Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication 2015–188, RI 9699., 2014. 20 Apr 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/mining/UserFiles/works/pdfs/2015-188.pdf.

- Hoffman, H. G. Immersive Virtual Reality as an Adjunctive Non-opioid Analgesic for Pre-dominantly Latin American Children With Large Severe Burn Wounds During Burn Wound Cleaning in the Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Study. Front Hum Neurosci 2019, vol. 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Skip, K. S. Thomas, and T. T. Brett, Clinical Virtual Reality: Emerging Opportunities for Psychiatry. Focus (Madison) 2018, vol. 16, 266–278. [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M. R. Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. In Proceedings of the Human Factors Society annual meeting, 1988; Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, ME; Brnich, MJ; Hoebbel, CL; Self-escape core competency profile: guidance for improving underground coal miners’ self-escape competency; NIOSH. Pittsburgh PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2023-133 (revised 06/2023), IC 9534. https://doi.org/10.26616/NIOSHPUB2023133revised062023. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. O’HARE, W. MARK, W. ANTHONY, and W. and WONG, Cognitive task analyses for decision centred design and training. Ergonomics 1998, vol. 41(no. 11), 1698–1718. [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Militello, L. 4. Some guidelines for conducting a cognitive task analysis. In Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2001; vol. 1 vol. 1. pp. 163–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, M. J.; Wiggins, S.; Reynolds, K. D.; Berger, J. L.; Hoebbel, C. L. Cognitive Task Analysis of Miner Preparedness to Self-Escape from Mine Emergencies. J Organ Psychol 2018, vol. 18(no. 4), 57–78. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30820492.

- Peters, R. H.; Kosmoski, C. Are Your Coal Miners Prepared to Self-escape? Coal Age. 11 Feb 2013. Available online: https://www.coalage.com/features/are-your-coal-miners-prepared-to-self-escape/.

- Kowalski-Trakofler, K. M.; Vaught, C.; Brnich, M. J.; Jansky, J. H. A Study of First Moments in Underground Mine Emergency Response. J Homel Secur Emerg Manag 2010, vol. 7(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, H.; Long, R.; Zhang, M. Research on 10-year tendency of China coal mine accidents and the characteristics of human factors. Saf Sci 2012, vol. 50(no. 4), 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M. R. SAGAT: A methodology for the measurement of situation awareness; Northrop Corp: Hawthorne, CA; NOR DOC, 1987; pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Endsley, M. R. “Situation awareness global assessment technique (SAGAT),” in Aerospace and Electronics Conference, 1988. NAECON 1988. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1988 National, 1988; IEEE; pp. 789–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Charles R. What is Adaptive Training?1. Hum Factors 1969, vol. 11(no. 6), 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S. A. M.; Raza, M.; Ghazal, S.; Salehi, S.; Kang, Z.; Teodoriu, C. Simulation-based training to enhance process safety in offshore energy operations: Process tracing through eye-tracking. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2020, vol. 138, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A. An Eye Tracking Based Framework for Safety Improvement of Offshore Operations. J Eye Mov Res 2023, vol. 16(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A. Situational awareness measurement in a simulation-based training framework for offshore well control operations. J Loss Prev Process Ind 2019, vol. 62, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S. A. M.; Raza, M.; Ybarra, V. T.; Salehi, S.; Teodoriu, C. Using content analysis through simulation-based training for offshore drilling operations: Implications for process safety. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2019, vol. 121, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militello, L. G.; Hutton, R. J. Applied cognitive task analysis (ACTA): a practitioner’s toolkit for understanding cognitive task demands. Ergonomics 1998, vol. 41(no. 11), 1618–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraagen, J. M.; Chipman, S. F.; Shalin, V. L. Cognitive task analysis; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, US, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall, B.; Klein, G.; Hoffman, R. R. Working minds: A practitioner’s guide to cognitive task analysis; Boston Review: Cambridge, MA, US, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MILITELLO, L. G.; HUTTON, R. J. B. Applied cognitive task analysis (ACTA): a practitioner’s toolkit for understanding cognitive task demands. Ergonomics 1998, vol. 41(no. 11), 1618–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. E.; Estes, F. Cognitive task analysis for training. Int J Educ Res 1996, vol. 25(no. 5), 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauerle, T.; Bellanca, J. L.; Brnich, M.; Helfrich, W. J.; Orr, T. “Improving Simulation Training Debriefs: Mine Emergency Escape Training Case Study,” in Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation, and Education Conference (I/ITSEC), in Mining Publications; National Training and Simulation Association (NTSA), Nov 2016; pp. 16319–16332. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/228414.

- Stafford, A.; Brown Requist, K. W.; Lotero Lopez, S.; Gordon, J.; Momayez, M.; Lutz, E. Underground Mining Self-Escape and Mine Rescue Practices: an Overview of Current and Historical Trends. Min Metall Explor 2023, vol. 40(no. 6), 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A. Situational awareness measurement in a simulation-based training framework for offshore well control operations. J Loss Prev Process Ind 2019, vol. 62, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).