Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The G14R mutation in α-synuclein is associated with aggressive, early-onset Parkinson’s disease, yet its impact on the protein’s N-terminal regulatory domain remains poorly understood. As an intrinsically disordered protein, α-synuclein’s conformational landscape is highly sensitive to sequence perturbations and ligand interactions. This study investigates a hypothesized "allosteric tug-of-war" between pro-aggregatory zinc ions and inhibitory dopamine at the N-terminus. Using a Python-based physicochemical structural proxy model, we assessed residue-level charge, volume, and interaction heuristics for the first 20 residues of the G14R variant. Our results demonstrate that the substitution of glycine with arginine at residue 14 creates a localized "rigidity hotspot" characterized by enhanced electrostatic coordination with Zn2+ ions. Crucially, we found that dopamine competitively attenuates this stabilization at overlapping residues, suggesting a displacement-based mechanism. This modeling framework provides a mechanistic basis for the G14R phenotype, suggesting that dopamine depletion may permit persistent zinc-mediated structural stabilization, thereby promoting aggregation. These findings highlight the N-terminus as a critical switch for modulating α-synuclein pathology through small-molecule competition.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Sequence Selection and N-Terminal Focus

2.2. Physicochemical Structural Confidence Proxy

2.3. Physicochemical Zinc Binding Model

2.4. Competitive Binding Simulation

2.5. Data Normalization and Statistical Handling

2.6. Visualization and Computational Analysis

3. Results

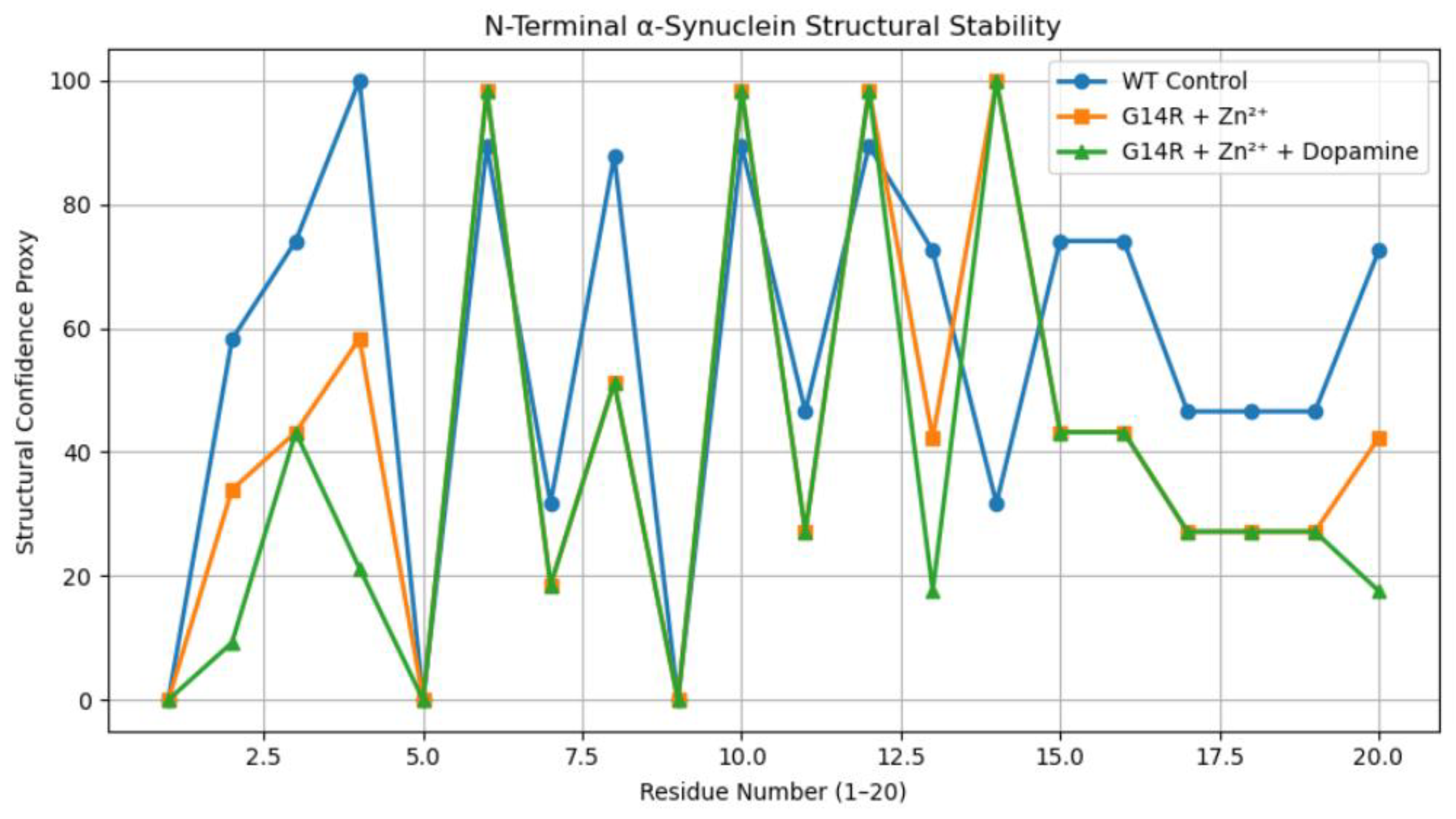

3.1. N-Terminal Structural Confidence Profiles

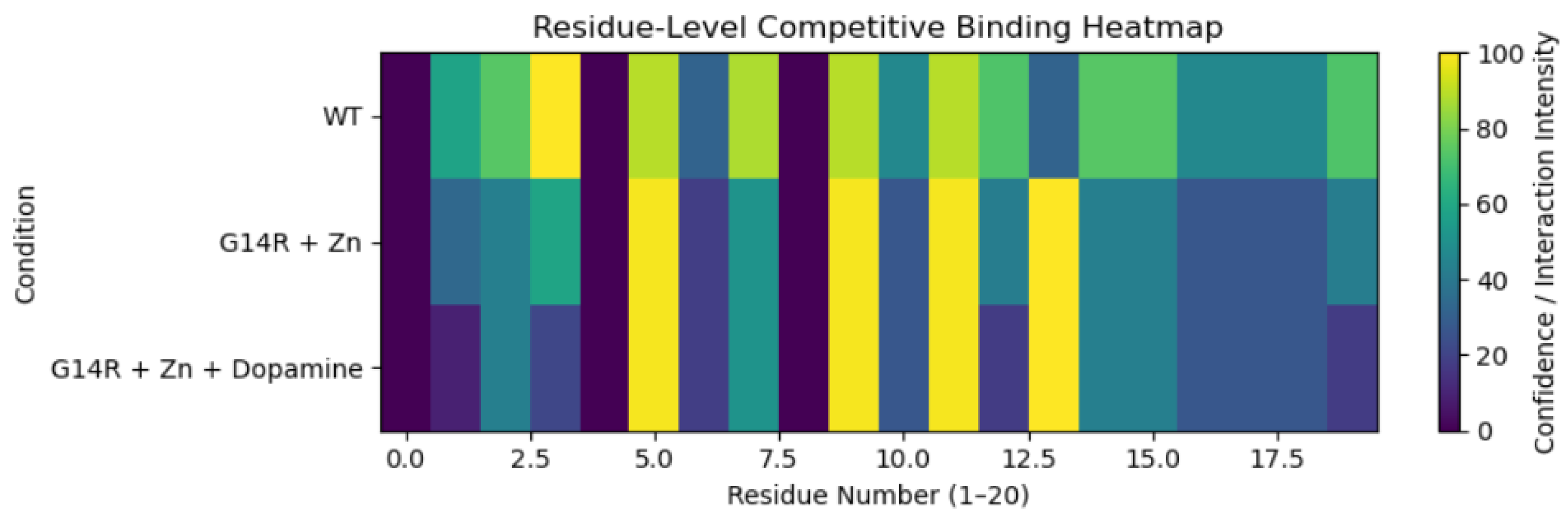

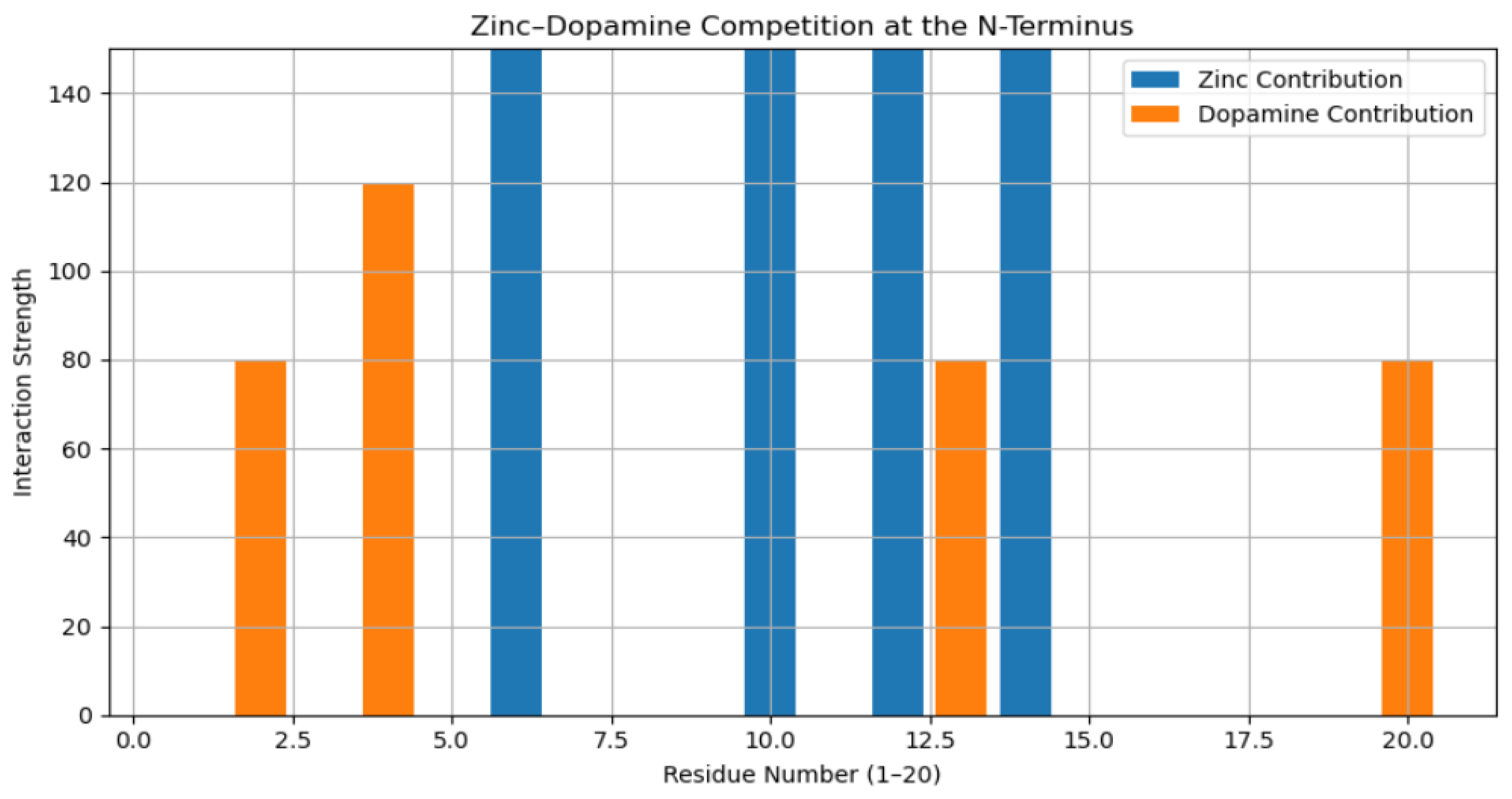

3.2. Residue-Level Competitive Binding Patterns

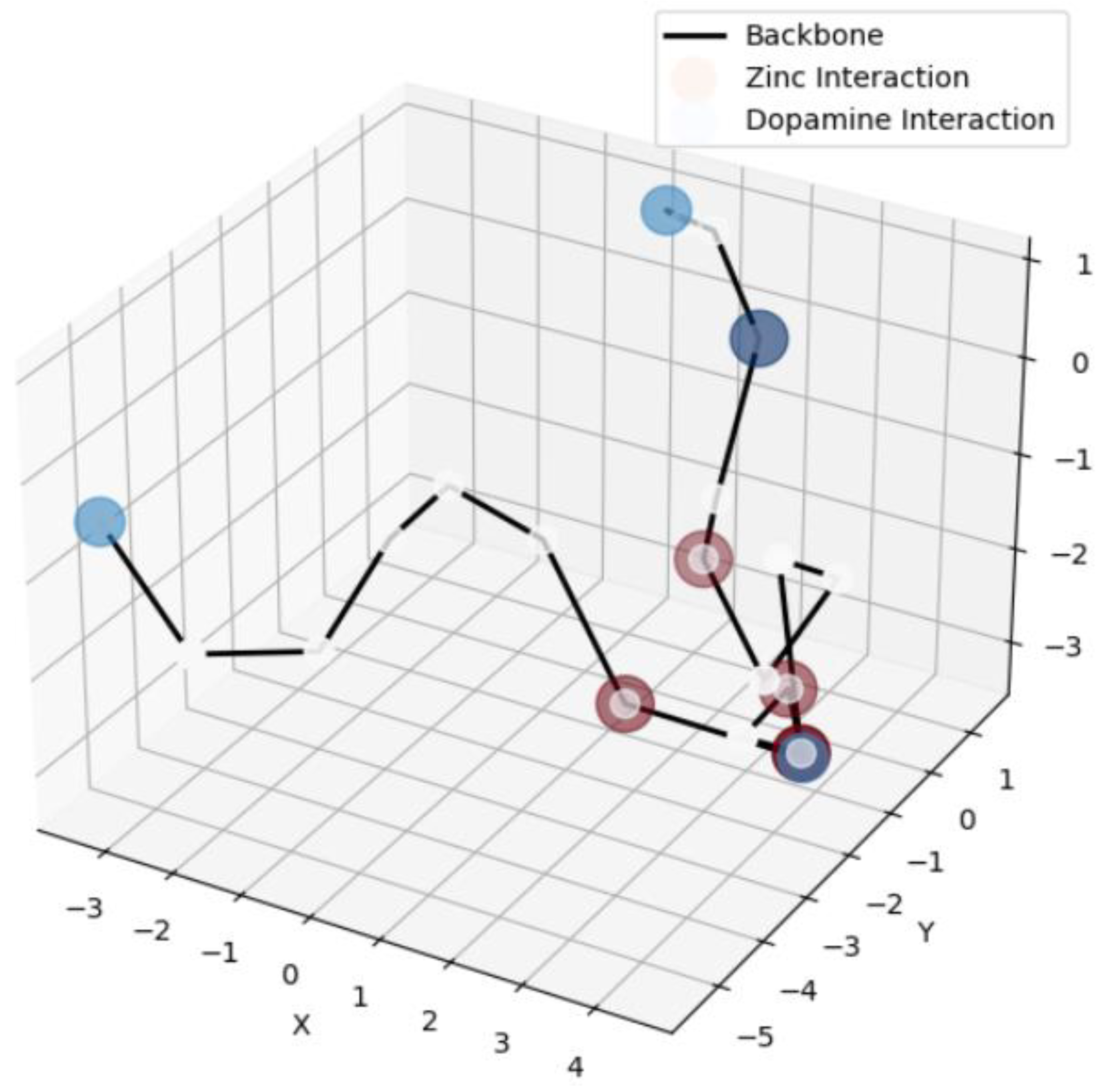

3.3. Coarse-Grained Structural Visualization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Becker, C.; Berg, D.; Doppler, E. Transcranial sonography reveals increased echogenicity of substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1995. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8584273/.

- Bisaglia, M.; Bubacco, L. α-Synuclein and metal ions: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic opportunities. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2020. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.00436/full.

- Chen, S.; et al. Alpha-synuclein oligomers interact with metal ions to induce oxidative stress and neuronal death in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2016. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26651444/.

- Davanzo, D.; et al. Dopamine alters the stability and amyloidogenic properties of α-synuclein. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2012. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022283612006081.

- Dehay, B.; et al. Targeting α-synuclein for treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Mechanistic and therapeutic considerations. The Lancet Neurology 2015, 14(8), 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duce, J. A.; Bush, A. I. Biological metals and Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for therapeutics and diagnostics. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giasson, B. I.; et al. Mutations in α-synuclein link Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Nature Genetics 2000, 25(2), 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. M.; Khan, A. Alpha-synuclein aggregation in Parkinson’s disease. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. 2024. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876162324001251.

- Krüger, R.; et al. Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Nature Genetics 1998, 18(2), 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashuel, H. A.; et al. The many faces of α-synuclein: From structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2013, 14(1), 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotharius, J.; Brundin, P. Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease: Dopamine, vesicles and α-synuclein. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2002, 3(12), 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroteaux, L.; Campanelli, J. T.; Scheller, R. H. Synuclein: A neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. Journal of Neuroscience 1988, 8(8), 2804–2815. Available online: https://www.jneurosci.org/content/8/8/2804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post translational changes to α-synuclein control iron and dopamine trafficking; a concept for neuron vulnerability in Parkinson’s disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 2017. Available online: https://molecularneurodegeneration.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13024-017-0186-8.

- Rasia, R. M.; et al. Structural characterization of Copper(II) binding to α-synuclein: Insights into the bioinorganic chemistry of Parkinson’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102(12), 4294–4299. Available online: https://www.pnas.org/content/102/12/4294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, D. J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2016, 8(6), 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, Z.; et al. Metal ions shape α-synuclein conformational ensembles. Scientific Reports. 2020. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-73207-9.

- Uversky, V. N. A protein chasing its tails: Structural disorder in monomeric α-synuclein. FEBS Letters 2003, 512(1–3), 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V. N. The multifaceted roles of intrinsic disorder in protein function. In Biophysical Reviews; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. Dopamine inhibits α-synuclein fibrillization by binding and stabilizing soluble oligomers. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287(34), 28928–28940. Available online: https://www.jbc.org/content/287/34/28928.

- Alpha-synuclein structure and Parkinson’s disease – Lessons and emerging principles. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13024-019-0329-1.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).