1. Introduction

Machine translation (MT) is a fundamental task in natural language processing that aims to automatically convert text from one language to another while preserving meaning, fluency, and style. The development of neural machine translation (NMT) has revolutionized the field, enabling significant improvements in translation quality compared to traditional statistical approaches [

1,

2]. Recent advancements have further expanded into large language model (LLM) based translation, setting new benchmarks for evaluation and fluency [

6,

7].

English-Spanish translation is particularly important given that Spanish is the second most spoken native language globally, with substantial commercial and cultural significance. However, it presents specific linguistic challenges for NMT systems. Spanish possesses a rich morphology with gendered nouns and complex verb conjugations that do not exist in English. These features often lead to "agreement errors" in automated translation, where the model fails to align the gender or number of adjectives with their modified nouns. Furthermore, the flexible word order in Spanish requires models to maintain long-range dependencies effectively, challenging older sequential architectures [

11].

Neural machine translation typically employs an encoder-decoder architecture where the encoder processes the source sentence into a continuous representation, and the decoder generates the target sentence token by token. Early NMT systems used recurrent neural networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [

3]. While effective for short sequences, these models struggled with long-term dependencies. The introduction of attention mechanisms allowed models to focus on relevant parts of the source sentence during decoding [

2].

More recently, the Transformer architecture [

1] replaced recurrence with self-attention, enabling parallel processing. This shift has led to the current state-of-the-art in NMT. We aim to empirically quantify the performance gains offered by these innovations, addressing three research questions: (1) How data-efficient are Transformers compared to LSTMs? (2) Can pre-trained embeddings improve recurrent architectures? (3) What are the specific linguistic failure modes associated with each architecture?

2. Related Work

2.1. Attention Mechanisms in NMT

Bahdanau et al. [

2] introduced the attention mechanism for neural machine translation. Their additive attention computes alignment scores between decoder states and encoder outputs, allowing the model to focus on relevant source positions during each decoding step. This innovation significantly improved translation quality, especially for longer sentences, and became a standard component in NMT systems before the Transformer era.

2.2. The Transformer Architecture

Vaswani et al. [

1] proposed the Transformer architecture, which replaces recurrence entirely with self-attention mechanisms. The model uses multi-head attention to capture different types of dependencies, positional encodings to represent sequence order, and feed-forward networks for non-linear transformations. The Transformer’s parallel processing capability enables faster training and better scalability compared to RNN-based models.

2.3. Subword Tokenization

A critical component of modern NMT is the handling of open vocabularies. Sennrich et al. [

4] introduced Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) for NMT, which segments rare words into subword units. This approach allows models to translate unseen words by composing them from known subwords, significantly improving performance for morphologically rich languages like Spanish.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

We use two complementary datasets for training and evaluation:

OPUS-100 [

13]: A massively multilingual corpus derived from the OPUS collection. For our English-Spanish experiments, we use 1 million parallel sentence pairs for training and combine the original development and test splits into a 4,000-pair development set.

FLORES+ [

8]: A high-quality benchmark dataset specifically designed for evaluating machine translation systems. We use 2,009 sentences for our blind test set. Unlike OPUS-100, FLORES+ contains professionally translated Wikipedia content, providing a challenging out-of-domain test of generalization.

3.2. Preprocessing

We utilized standard tokenization pipelines provided by the Hugging Face `tokenizers` library. To handle the open vocabulary problem, we trained a Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer on the concatenated source and target corpora with a vocabulary size of 32,000. This ensures that the model can handle rare words and cognates effectively, which is crucial for English-Spanish translation.

3.3. Model Architectures

3.3.1. Baseline: Vanilla LSTM

Our neural baseline is a unidirectional LSTM encoder-decoder without attention. The encoder processes the source sentence left-to-right, and its final hidden state initializes the decoder. This simple architecture tests the ability of the model to compress variable-length inputs into a single fixed-size vector.

3.3.2. BiLSTM + Bahdanau Attention

We enhanced the baseline with a bidirectional encoder and additive attention mechanism. The bidirectional encoder captures both forward and backward context. The attention mechanism calculates a context vector at each decoding step i as a weighted sum of encoder hidden states.

3.3.3. Transformer

Our primary model is the Transformer [

1]. It utilizes multi-head self-attention. We implemented a standard configuration with 6 encoder layers and 6 decoder layers. We employ weight tying between encoder embeddings, decoder embeddings, and the output projection layer to reduce the total parameter count and prevent overfitting.

3.4. Hyperparameters

Table 1 details the specific hyperparameters used for our experiments. We aimed to keep the model size comparable between the BiLSTM and Transformer to ensure a fair comparison of architectural efficiency.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate translation quality using three complementary metrics:

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Quantitative Analysis

Table 2 presents our main results on the FLORES+ test set.

The Vanilla LSTM failed to learn meaningful translation patterns (BLEU 0.92). Without an attention mechanism, the fixed-size vector bottleneck is too restrictive for the complexity of translation.

The addition of

Attention (BiLSTM) drastically improved performance to BLEU 10.66.

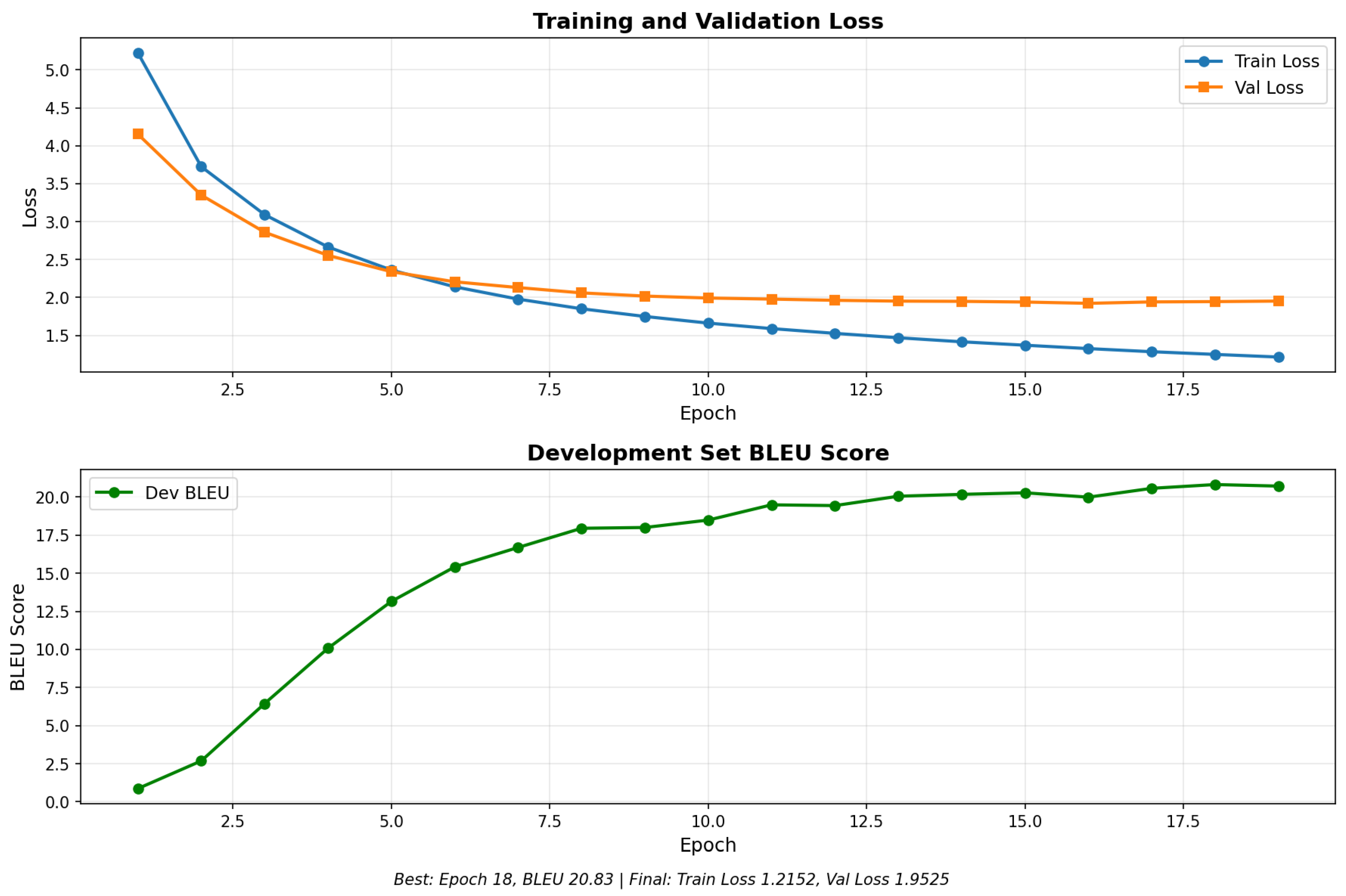

Figure 1 illustrates the training dynamics of this model; while it learns successfully, the validation loss plateaus at a much higher level than the Transformer models.

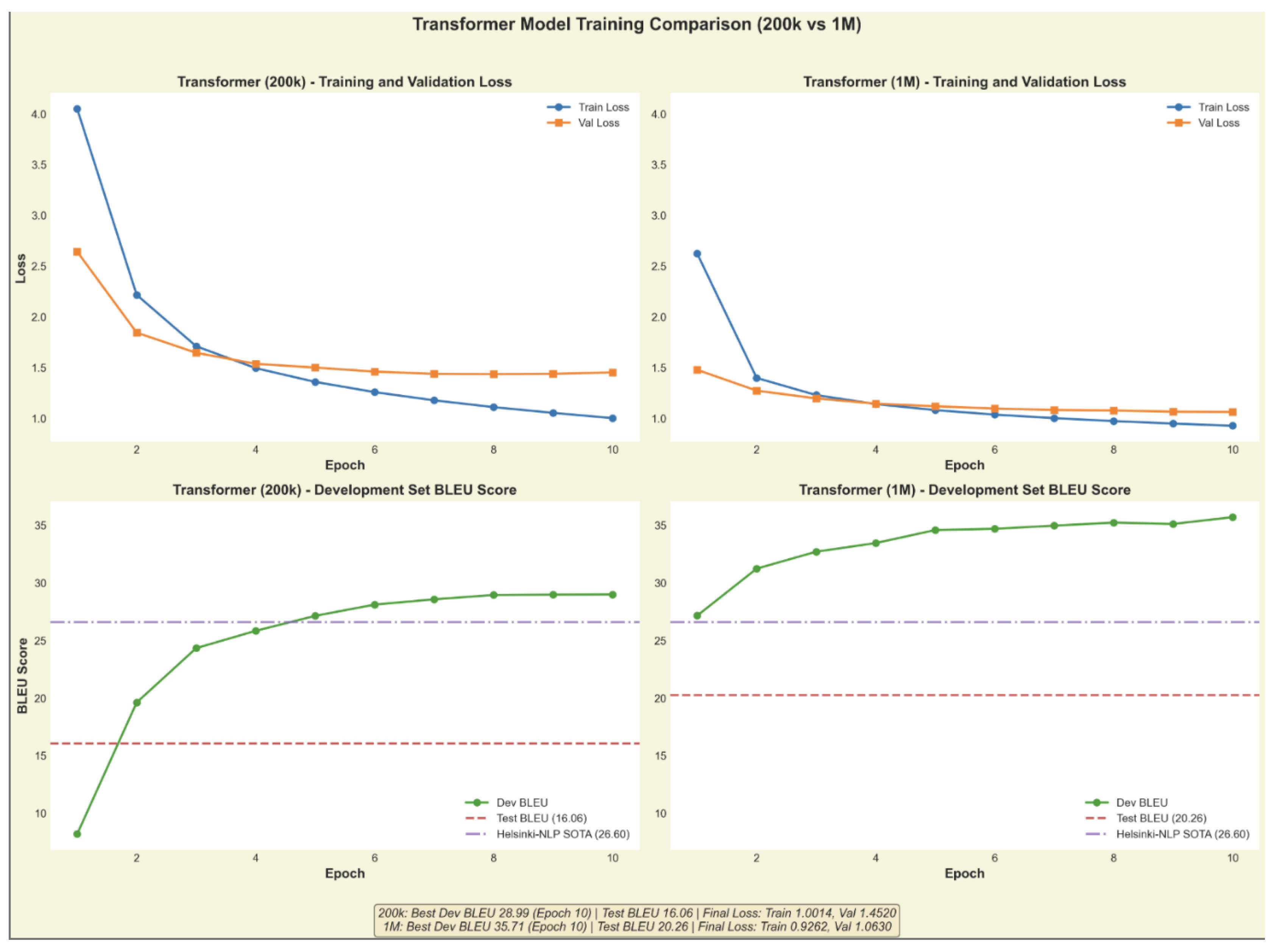

The Transformer architectures demonstrated superior data efficiency. Even with only 200K training samples, the Transformer (BLEU 16.06) outperformed the BiLSTM trained on the full 1M dataset. Scaling the Transformer to the full 1M dataset achieved our best result of BLEU 20.26.

4.2. Embedding Compatibility

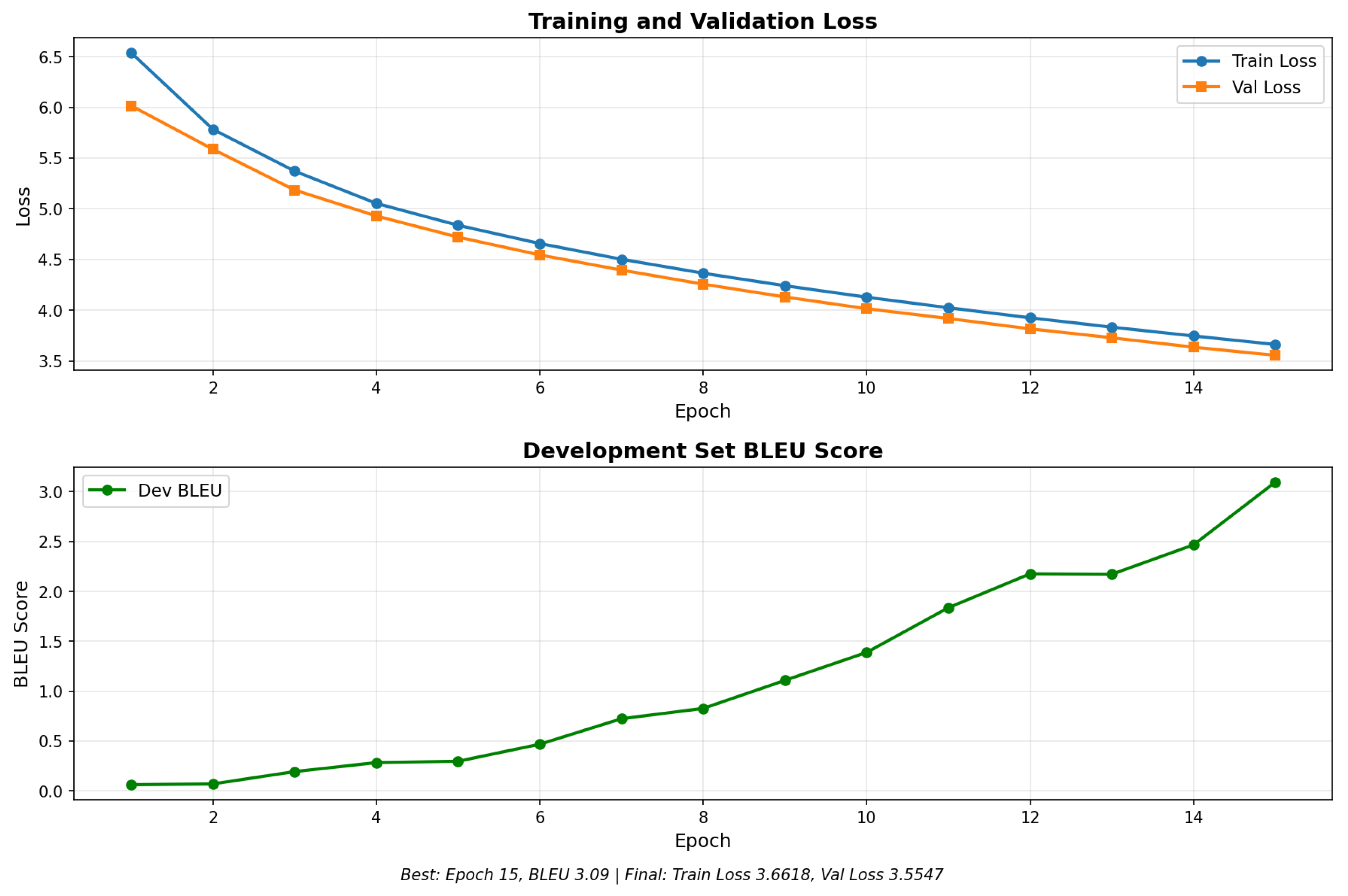

We hypothesized that initializing an LSTM with pre-trained embeddings from a Transformer model would improve performance (Exp 3). However, this resulted in a BLEU of 1.04, performing worse than the attention model.

Figure 2 shows the catastrophic failure of this experiment. The loss curve remains flat, suggesting that embeddings optimized for Transformer attention patterns are not compatible with the sequential inductive bias of LSTMs.

4.3. Training Dynamics

Figure 3 illustrates the training progression of our Transformer models. The 1M-sample model converges to a significantly lower validation loss.

5. Discussion and Error Analysis

To better understand the performance gap, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the translations.

5.1. LSTM Failure Modes

Table 3 presents representative errors from the LSTM baselines. The

Vanilla LSTM exhibits the "vanishing gradient" problem visually: it gets stuck in repetition loops. The

BiLSTM + Attention model fixes the coverage issue but lacks fluency, often producing "word salad" or hallucinating non-existent words.

5.2. Transformer vs. State-of-the-Art

Our Transformer (1M) produces grammatically fluent Spanish, correcting the syntactic disasters of the LSTMs. However, a gap of roughly 6 BLEU points remains between our model and the Helsinki-NLP SOTA model. This gap is driven by subtle semantic and morphological errors, consistent with findings in other domain adaptation studies [

12].

Table 4.

Transformer Errors vs. SOTA.

Table 4.

Transformer Errors vs. SOTA.

| Source (English) |

Our Transformer (1M) |

SOTA (Helsinki-NLP) |

| The judge decided to reduce the sentence. |

El juez decidió reducir la frase. |

El juez decidió reducir la sentencia. |

| It is crucial that she arrive on time. |

Es crucial que ella llega a tiempo. |

Es crucial que ella llegue a tiempo. |

| The orthodontist checked her teeth. |

El ortodoxo revisó sus dientes. |

El ortodoncista revisó sus dientes. |

6. Conclusion

We presented a systematic comparison of NMT architectures for English-Spanish translation. Our results confirm the superiority of the Transformer architecture, which achieves a BLEU score of 20.26, nearly double that of the best LSTM baseline.

Our analysis reveals that while Transformers are highly data-efficient, bridging the final gap to state-of-the-art performance requires massive datasets to handle rare vocabulary and complex grammatical moods effectively. Furthermore, we demonstrated that simple transfer learning via embedding initialization is ineffective for LSTMs, highlighting the importance of architectural compatibility.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the use of NVIDIA L40S GPUs provided by the University of Pennsylvania’s computing cluster. This work utilized the OPUS-100 dataset and FLORES+ benchmark. We thank the OPUS project for providing the parallel corpora.

References

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A. N.; Kaiser; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Proc. NeurIPS, 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. Proc. ICLR, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q. V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. Proc. NeurIPS, 2014; pp. 3104–3112. [Google Scholar]

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. Proc. ACL, 2016; pp. 1715–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.-J. BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. Proc. ACL, 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, W.; Wang, W.; Huang, J.-T.; Wang, X.; Tu, Z. Is ChatGPT a good translator? A preliminary study. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.08745. [Google Scholar]

- Hendy, A.; Abdelrehim, M.; Sharaf, A.; Raunak, V.; Gabr, M.; Matsue, H.; Lobban, S. Y.; Awadalla, H. H. How good are GPT models at machine translation? A comprehensive evaluation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.09210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-jussà, M. R.; Cross, J.; NLLB Team. No language left behind: Scaling human-centered machine translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, R.; de Souza, J. G. C.; Alves, D.; Zerva, P.; Farinha, A. C.; Glushkova, T.; Lavie, A.; Coheur, L.; Martins, A. F. COMET-22: Unifying translation evaluation. Proc. WMT, 2022; pp. 585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Kocmi, T.; Bawden, R.; Bojar, O.; Dvorkovich, A.; Federmann, C.; Fishel, M.; Gowda, T.; Graham, Y.; Grundkiewicz, R.; Haddow, B. Findings of the 2022 conference on machine translation (WMT22). Proc. WMT, 2022; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stahlberg, F. Neural machine translation: A review. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2021, vol. 69, 343–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslem, Y.; Haque, R.; Kelleher, J. D. Domain-specific text generation for machine translation. Proc. AACL-IJCNLP, 2022; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Williams, P.; Titov, I.; Sennrich, R. Improving massively multilingual neural machine translation and zero-shot translation. Proc. ACL, 2020; pp. 1628–1639. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).