1. Introduction

Physical activity and exercise testing are fundamental components of exercise science and clinical exercise practice. Regular physical activity has been shown to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, pulmonary function, and metabolic health, while reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related morbidity [

1,

2]. However, individuals with cardiovascular risk factors often exhibit reduced exercise tolerance, early fatigue, and impaired pulmonary function, which limit participation in conventional exercise programs. Accordingly, there is increasing interest in simple, time-efficient, and field-based exercise assessments that can characterize functional capacity and elicit measurable physiological responses in populations with reduced functional reserve.

Impaired pulmonary function has been increasingly recognized as an important determinant of exercise performance and health outcomes. Reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) have been associated with higher cardiovascular risk and all-cause mortality in large epidemiological studies [

3]. For example, a cohort study among Chinese adults demonstrated that for every 5% decrease in the FEV₁/FVC ratio, the 10-year risk of CVD increased significantly, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.12 for high-risk status [

3]. Mendelian randomization analyses further suggest a bidirectional relationship between pulmonary function and cardiovascular disease [

4]. In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) frequently coexists with CVD, sharing common mechanisms such as systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, and contributing to reduced exercise capacity and poorer outcomes [

5]. Impaired oxygenation and reduced oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO₂) further exacerbate exercise intolerance in these populations.

The two-minute step test (2MST) is a simple, field-based assessment of functional fitness that requires minimal space and equipment. Originally introduced by Rikli and Jones as part of the Senior Fitness Test battery [

6], the 2MST provides a rapid estimate of aerobic endurance and lower-extremity function. It has since been validated across a wide range of populations, including older adults and individuals with chronic conditions such as hypertension, obesity, COPD, and Parkinson’s disease [

7,

8]. Compared with longer exercise assessments such as the six-minute walk test, the 2MST is shorter, safer, and more feasible for individuals with limited mobility or reduced exercise tolerance.

Beyond its practicality, performance on the 2MST has been shown to correlate strongly with established indicators of functional capacity, including peak oxygen uptake (VO₂peak), cardiorespiratory endurance, and lower-extremity strength, supporting its validity as a proxy for aerobic fitness [

7,

8]. Lower step counts are associated with functional decline and increased cardiopulmonary risk, whereas improvements in performance may reflect gains following exercise training or rehabilitation. Importantly, the cardiovascular demand induced by the 2MST is typically moderate, corresponding to an increase in heart rate of approximately 20–30 beats per minute, underscoring its tolerability and safety even in individuals with elevated cardiovascular risk [

7]. Owing to its simplicity, reproducibility, and rapid administration, the 2MST has been widely applied in large-scale epidemiological studies, community health screenings, and clinical exercise evaluations [

2,

7,

8,

9].

Emerging evidence suggests that even brief bouts of moderate-intensity physical activity may acutely influence ventilatory mechanics and gas exchange [

9]. Such short-duration exercise stimuli may be particularly relevant for individuals with cardiovascular risk factors, who often demonstrate reduced baseline functional capacity. However, while the 2MST is commonly used as a functional assessment tool, its acute effects on pulmonary function and oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO₂) have not been well characterized. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether these acute physiological responses vary according to sex, age, or baseline exercise performance.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the acute effects of a two-minute stepping exercise on pulmonary function and oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO₂) in adults with cardiovascular risk factors. We further examined whether these responses differed by sex, age, and levels of stepping performance. We hypothesized that: (1) a single bout of the two-minute step test would be associated with small but measurable increases in FVC, FEV₁, and peak expiratory flow (PEF); (2) SpO₂ would increase following exercise, particularly among individuals with lower baseline exercise tolerance; and (3) the magnitude of these responses would be more pronounced in subgroups with reduced baseline functional capacity, such as older adults, women, or those in lower performance tertiles.

By addressing these questions, this study provides new insight into the utility of the two-minute step test not only as a functional fitness assessment, but also as a brief physiological stimulus capable of eliciting measurable cardiopulmonary responses in a clinical exercise population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study recruited 239 participants (155 females and 84 males) with cardiovascular risk factors from Lipid Clinic of National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH), Taipei, Taiwan between May 2015 and August 2015. This 2-min stepping test was one part of physical fitness evaluation before Tongtzu Gymnastics training study. Cardiovascular risk factors were defined as physician-diagnosed hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or obesity (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m²). Eligible participants were aged ≥50 years and clinically stable, without acute cardiovascular or respiratory events in the preceding 3 months. Exclusion criteria included: 1. unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or heart failure exacerbation within 3 months; 2. severe musculoskeletal limitations impairing mobility; 3. chronic respiratory diseases other than COPD or asthma under control; and 4. inability to provide informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of NTUH, and all participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Anthropometric and Body Composition Measurements

Height and weight were measured using a stadiometer and digital scale, respectively, with participants barefoot and wearing light clothing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height² (m²). Waist and hip circumferences were measured using a flexible tape, and waist-to-hip ratio was calculated. Handgrip strength was assessed with a dynamometer TKK-5401(Takei, Niigata, Japan) using the dominant hand, and the best of three trials was recorded.Body composition, including fat-free mass (FFM), fat mass, body fat percentage, visceral fat rating, and segmental lean mass, was measured using a bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Tanita, Model MC-780MA, Tokyo, Japan). Basal metabolic rate (BMR), predicted muscle mass (PMS), and total body water (TBW) were derived according to manufacturer algorithms.

2.3. Two-Minute Step Test (2MST)

Functional exercise capacity was assessed using the filed-based two-minute step test (2MST), following a standardized protocol, which assesses aerobic fitness and has been widely used in geriatrics, cardiac rehab, and chronic conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or stroke, showing functional capacity and cardiovascular response. Participants were instructed to march in place for two minutes, flexing the knee to 90 degrees. A ruler was positioned at a fixed height, and participants were required to touch the ruler with the knee at each step. The total number of right knee raises completed within two minutes was recorded. The test was conducted in a well-ventilated room under continuous supervision by trained staff. Participants were instructed to stop if they experienced chest pain, severe dyspnea, or dizziness. Performance was stratified into tertiles according to step counts (≤60, 61–74, ≥75).

2.4. Pulmonary Function Testing

Spirometry was performed pre- and post-2MST using a portable spirometer Spirolab III® (Medical International Research; MIR, Roma, Italy) in accordance with ATS/ERS guidelines. Parameters recorded included forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV₁), FEV₁/FVC ratio, and peak expiratory flow (PEF). The best of three reproducible maneuvers was analyzed. Post-exercise spirometry was conducted within 2 minutes of test completion.

2.5. Oxyhemoglobin Saturation and Heart Rate Monitoring

Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) and heart rate (HR) were continuously monitored using a finger pulse oximeter, SA310 Oximeter (Rossmax SA310 Pulpas, Taipei, Taiwan). Measurements were recorded at baseline (seated, after 5 min of rest), every 10 seconds starting from 1 minute before test, throughout the 2-minute stepping exercise, and continued for 3 minutes post-exercise. For subgroup analysis, participants were stratified by tertiles of stepping performance and by sex.

2.6. Covariates and Clinical History

Baseline demographics, medical history (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia), lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, exercise habits), and medication use were collected through standardized questionnaires and medical records. Exercise habit was defined as ≥30 min of moderate-intensity physical activity at least 3 times per week.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or mean with 95% confidence intervals (CI), as appropriate, and categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Baseline differences between sexes were assessed using independent-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Changes in pulmonary function parameters and oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO₂) before and after the two-minute step test were evaluated using paired t-tests. Between-group comparisons according to sex, age groups, and tertiles of step counts were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with Bonferroni post-hoc adjustments where appropriate. Interaction effects between age and sex were explored. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A post-hoc power analysis for the primary outcome (ΔFVC ≈ 0.06 L, SD ≈ 0.20) indicated greater than 90% statistical power at an alpha level of 0.05 for the full study population (n = 239).

3. Results

In this study, body composition analysis (Supplemental

Table S1) revealed that men had significantly higher fat-free mass (55.7 ± 6.5 vs. 38.0 ± 3.7 kg, p<0.001), skeletal muscle mass (52.8 ± 6.2 vs. 35.9 ± 3.3 kg, p<0.001), and basal metabolic rate (1533.9 ± 202.3 vs. 1117.1 ± 125.3 kcal, p<0.001), whereas women exhibited higher body fat percentage (34.2 ± 7.0% vs. 23.6 ± 4.0%, p<0.001) and visceral fat rating (8.0 ± 3.1 vs. 14.1 ± 2.9, p<0.001). When stratified by tertiles of stepping performance (Supplemental

Table S2), individuals in the lowest tertile had significantly lower baseline FVC (female: 2.06 ± 0.44 L vs. 2.38 ± 0.36 L in the highest tertile, p<0.01), FEV₁ (1.70 ± 0.37 vs. 2.04 ± 0.34 L, p<0.01), and PEF (5.11 ± 0.92 vs. 5.81 ± 0.91 L/s, p<0.01). Further stratified analyses (Supplemental

Tables S3 and S4) demonstrated that heart rate responses were generally consistent across tertiles and between sexes. For example, mean post-exercise HR was 83.6 ± 14.8 bpm in the lowest tertile and 93.3 ± 15.7 bpm in the highest tertile (p<0.01), but after adjusting for age and sex, the differences were no longer significant.

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 239 participants (155 females and 84 males) were included. Female participants were older (63.5 ± 7.1 vs. 60.8 ± 9.4 years,

p = 0.016), had lower BMI (24.2 ± 3.9 vs. 25.6 ± 3.1 kg/m²,

p = 0.004), weaker hand grip strength (20.6 ± 3.9 vs. 36.9 ± 6.8 kg,

p < 0.001), and performed fewer stepping counts (64.9 ± 15.4 vs. 70.4 ± 21.2,

p = 0.042) compared with males. In contrast, males had significantly higher prevalence of smoking (34% vs. 2%) and alcohol consumption (30% vs. 3%) (

Table 1). Baseline characteristics stratified by tertiles of stepping performance (Supplemental

Table S5) further demonstrated that individuals in the lowest tertile were significantly older (66.9 ± 8.5 vs. 58.8 ± 6.8 years, p<0.01), had lower fat-free mass (42.6 ± 8.6 vs. 48.1 ± 11.5 kg, p=0.01), and higher body fat percentage (32.7 ± 8.1% vs. 28.6 ± 6.8%, p=0.01) compared with the highest tertile.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants stratified by sex.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants stratified by sex.

| Variable |

Female

(n = 155) |

Male

(n = 84) |

p-value |

| Age (years) |

63.5 ± 7.1 |

60.8 ± 9.4 |

0.016 |

| Height (cm) |

155.8 ± 4.8 |

169.0 ± 6.8 |

<0.001 |

| Weight (kg) |

58.7 ± 10.0 |

73.3 ± 10.7 |

<0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m²) |

24.2 ± 3.9 |

25.6 ± 3.1 |

0.004 |

| Waist circumference (cm) |

78.7 ± 9.3 |

88.5 ± 7.8 |

<0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) |

95.0 ± 7.9 |

96.3 ± 5.5 |

0.136 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio |

0.83 ± 0.07 |

0.92 ± 0.05 |

<0.001 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) |

20.6 ± 3.9 |

36.9 ± 6.8 |

<0.001 |

| Two-minute stepping counts (n) |

64.9 ± 15.4 |

70.4 ± 21.2 |

0.042 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) |

19 (12%) |

14 (17%) |

0.348 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) |

112 (72%) |

60 (71%) |

0.892 |

| Hypertension, n (%) |

59 (38%) |

40 (48%) |

0.153 |

| Regular exercise, n (%) |

97 (63%) |

56 (67%) |

0.532 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) |

5 (3%) |

26 (30%) |

<0.001 |

| Current smoking, n (%) |

3 (2%) |

29 (34%) |

<0.001 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg at rest.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL.

Regular exercise was defined as ≥30 min per day and ≥3 times per week.

3.2. Pulmonary Function Response

After the two-minute stepping exercise, both FVC and FEV₁ improved significantly in males and females (

Table 2). In females, FVC increased from 2.27 ± 0.43 L to 2.32 ± 0.44 L (

p < 0.05), and FEV₁ increased from 1.91 ± 0.38 L to 1.95 ± 0.37 L (

p < 0.05). In males, FVC increased from 3.31 ± 0.70 L to 3.39 ± 0.70 L (

p < 0.05), and FEV₁ increased from 2.73 ± 0.60 L to 2.81 ± 0.60 L (

p < 0.05). The FEV₁/FVC ratio remained unchanged (female: 84.2% vs. 84.1%; male: 82.4% vs. 82.9%), indicating proportional improvements in both inspiratory and expiratory volumes. PEF improved most prominently in younger males (<64 years), rising from 8.31 ± 1.37 L/s to 8.65 ± 1.51 L/s (

p < 0.05) (

Table 3).

Table 2.

Pulmonary function parameters before and after the two-minute stepping exercise, stratified by sex.

Table 2.

Pulmonary function parameters before and after the two-minute stepping exercise, stratified by sex.

| Variable |

Female (n = 155) |

Male (n = 84) |

| |

Pretest |

Posttest |

Pretest |

Posttest |

| FVC (L) |

2.27 ± 0.43a

|

2.32 ± 0.44 c

|

3.31 ± 0.7 |

3.39 ± 0.7 c

|

| FEV₁ (L) |

1.91 ± 0.38 a

|

1.95 ± 0.37 c

|

2.73± 0.6 |

2.81 ± 0.6 c

|

| FEV₁/FVC (%) |

84.2 ± 5.1 |

84.1 ± 5.2 |

82.4 ± 5.1 |

82.9 ± 5.5 |

| PEF (L/s) |

5.5 ± 1.0 a

|

5.5 ± 1.0 |

7.9 ± 1.7 b

|

8.2 ± 1.8 c

|

Table 3.

Pre- and post-exercise pulmonary function performance stratified by different age and gender groups after 2-min exercise.

Table 3.

Pre- and post-exercise pulmonary function performance stratified by different age and gender groups after 2-min exercise.

| Sex |

Age group |

FVC (L) Pre |

FVC (L) Post |

FEV₁ (L)

Pre |

FEV₁ (L) Post |

FEV₁/FVC (%) Pre |

FEV₁/FVC (%) Post |

PEF (L/s) Pre |

PEF (L/s) Post |

| Female |

≤64 years |

2.42 ± 0.41ᵃᵇ |

2.47 ± 0.41ᶜ |

2.06 ± 0.35ᵃᵇ |

2.10 ± 0.34ᶜ |

85.2 ± 5.0ᵃᵇ |

85.1 ± 4.7 |

5.81 ±0.93ᵃᵇ |

5.84 ± 0.97 |

| Female |

≥65 years |

2.07 ± 0.38 |

2.12 ± 0.38ᶜ |

1.71 ± 0.32 |

1.75 ± 0.32ᶜ |

83.0 ± 5.1 |

82.7 ± 5.6 |

4.99 ± 0.80 |

5.08 ± 0.87 |

| Male |

≤64 years |

3.49 ± 0.63 |

3.55 ± 0.65ᶜ |

2.92 ± 0.50 |

2.98 ± 0.52ᶜ |

83.8 ± 4.4 |

84.3 ± 4.9 |

8.31 ± 1.37 |

8.65 ± 1.51ᶜ |

| Male |

≥65 years |

2.93 ± 0.69 |

3.03 ± 0.69ᶜ |

2.33 ± 0.59 |

2.43 ± 0.60ᶜ |

79.4 ± 5.2 |

79.9 ± 5.6 |

7.03 ± 2.01 |

7.26 ± 2.12 |

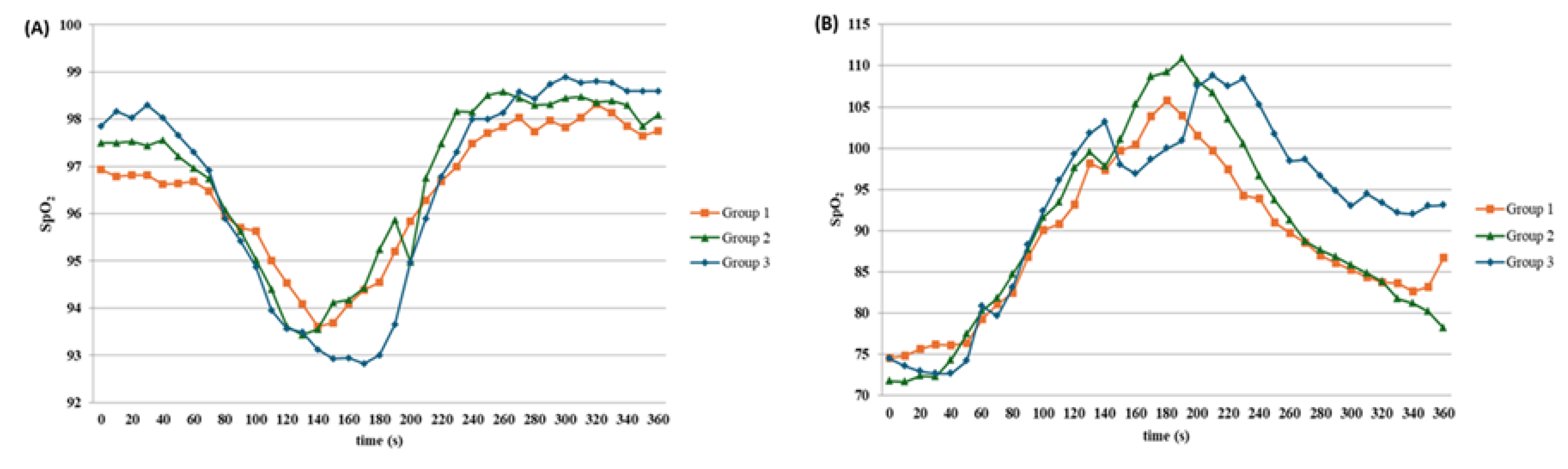

3.3. Oxyhemoglobin Saturation (SpO₂)

At baseline, patients in the lowest performance tertile (≤60 steps) had significantly lower SpO₂ (96.4% ± 2.2%) compared with those in the highest tertile (≥75 steps: 98.1% ± 1.3%;

p < 0.01) (

Table 4). After the two-minute stepping exercise, SpO₂ increased to 97.9% ± 1.4% in the lowest tertile, 98.4% ± 1.2% in the middle tertile, and 98.8% ± 1.0% in the highest tertile. The improvement was particularly notable among female participants, where those in the lowest tertile improved from 96.1% ± 2.4% to 97.8% ± 1.4% (

p < 0.01), effectively narrowing the gap with higher tertile groups (

Table 5;

Figure 1A).

Table 4.

Oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) before, during, and after the two-minute step test, stratified by tertiles of stepping counts.

Table 4.

Oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) before, during, and after the two-minute step test, stratified by tertiles of stepping counts.

| Variable |

Group 1

(≤60 steps, n=42) |

Group 2

(61–74 steps, n=40) |

Group 3

(≥75 steps, n=45) |

p-value |

| Range (median) |

19–60 (53.5) |

61–74 (67.5) |

75–133 (83.0) |

— |

| Crude |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-exercise (%) |

96.4 ± 2.2ᵇ |

97.3 ± 1.5 |

98.1 ± 1.3 |

<0.01 |

| During exercise (%) |

94.0 ± 3.3 |

94.1 ± 3.8 |

94.1 ± 3.5 |

0.93 |

| Post-exercise (%) |

97.9 ± 1.4ᵇ |

98.4 ± 1.2 |

98.8 ± 1.0 |

<0.01 |

| Age- and sex-adjusted |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-exercise (%) |

96.5 ± 0.3 |

97.4 ± 0.3 |

97.9 ± 0.4 |

0.02 |

| During exercise (%) |

94.5 ± 0.6 |

94.3 ± 0.6 |

93.4 ± 0.6 |

0.11 |

| Post-exercise (%) |

98.0 ± 0.2 |

98.4 ± 0.2 |

98.7 ± 0.3 |

0.06 |

Table 5.

Oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) before, during, and after the two-minute step test, stratified by sex and tertiles of stepping counts.

Table 5.

Oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) before, during, and after the two-minute step test, stratified by sex and tertiles of stepping counts.

| (A) Female |

|---|

| Variable |

Group 1

(≤58 steps, n=28) |

Group 2

(59–71 steps, n=27) |

Group 3

(≥72 steps, n=29) |

p for trend |

| Range (median) |

42–58 (51) |

59–71 (65) |

72–95 (77) |

— |

| Crude |

|

|

|

|

| Age (years) |

65.8 ± 8.3 |

64.2 ± 7.0 |

60.8 ± 4.6 |

<0.01 |

| Pre-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

96.1 ± 2.4ᵇ |

97.0 ± 1.7 |

98.3 ± 1.2 |

<0.01 |

| During exercise SpO₂ (%) |

93.6 ± 3.4 |

92.4 ± 3.6 |

93.9 ± 4.3 |

0.84 |

| Post-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

97.8 ± 1.4ᵇ |

98.3 ± 1.1 |

98.8 ± 1.0 |

0.01 |

| Age-adjusted |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

96.3 ± 0.4 |

96.9 ± 0.4 |

98.2 ± 0.5 |

0.01 |

| During exercise SpO₂ (%) |

93.9 ± 0.7 |

92.5 ± 0.8 |

93.5 ± 0.8 |

0.57 |

| Post-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

97.8 ± 0.3 |

98.4 ± 0.3 |

98.8 ± 0.3 |

0.01 |

| (B) Male |

| Variable |

Group 1

(≤68 steps, n=14)

|

Group 2

(69–80 steps, n=13)

|

Group 3

(≥81 steps, n=15)

|

p for trend |

| Range (median) |

19–68 (58) |

69–80 (75) |

81–133 (93) |

— |

| Crude |

|

|

|

|

| Age (years) |

68.5 ± 9.0 |

61.3 ± 6.1 |

55.1 ± 8.8 |

<0.01 |

| Pre-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

97.0 ± 1.2 |

97.7 ± 1.3 |

98.1 ± 1.2 |

0.06 |

| During exercise SpO₂ (%) |

95.8 ± 2.2 |

96.1 ± 1.7 |

94.3 ± 2.9 |

0.09 |

| Post-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

98.0 ± 1.5 |

99.0 ± 0.9 |

98.7 ± 1.0 |

0.15 |

| Age-adjusted |

|

|

|

|

| Pre-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

97.0 ± 0.4 |

97.7 ± 0.4 |

98.0 ± 0.5 |

0.10 |

| During exercise SpO₂ (%) |

95.6 ± 0.8 |

96.1 ± 0.7 |

94.5 ± 0.7 |

0.25 |

| Post-exercise SpO₂ (%) |

98.3 ± 0.4 |

99.0 ± 0.3 |

98.4 ± 0.4 |

0.73 |

3.4. Heart Rate Response

Heart rate increased significantly during exercise across all tertile groups (

Table 4;

Figure 1B). Mean heart rate rose from approximately 75 bpm at baseline to ~100 bpm during exercise, an average increase of 25 bpm (

p < 0.001). Post-exercise heart rate remained elevated (~85–93 bpm) compared with baseline. No significant differences in heart rate response were found between low-, medium-, and high-performance tertiles after adjusting for age and sex (

Table 5).

3.5. Exploratory Correlation Analyses

To describe inter-individual variability in acute physiological responses to the two-minute stepping exercise, exploratory correlation analyses were performed, building on the stratified results presented above (

Table 4 and

Table 5 and

Figure 1). Associations between changes in pulmonary function (ΔFVC, ΔFEV₁) and oxyhemoglobin saturation (ΔSpO₂) with baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were examined. Consistent with the tertile-based analyses of SpO₂ responses (

Table 5;

Figure 1A), lower baseline stepping performance and older age showed modest correlations with greater improvements in SpO₂ following exercise (r = 0.22–0.28, p < 0.05). In contrast, changes in pulmonary function (ΔFVC and ΔFEV₁), as summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, were not significantly correlated with the number of cardiovascular risk factors, smoking status, or indices of muscle mass and visceral fat (all p > 0.10).

4. Discussion

In this study, we observed that a simple two-minute stepping exercise was associated with immediate improvements in pulmonary function and oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO₂) in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors. Specifically, small but statistically significant increases in FVC and FEV₁ were observed across sex and age groups, whereas improvements in peak expiratory flow (PEF) were prominently noted among younger males participants. Notably, individuals with poorer baseline exercise tolerance, particularly females, exhibited relatively greatest improvement in SpO2, suggesting that those with low function capacity may demonstrate more pronounced oxygenation responses following short bouts of stepping exercise.

Overall, a consistent association was observed between the two-minute stepping exercise elicited acute changes in pulmonary function and oxygenation. Although the absolute increases in FVC and FEV₁ were modest (approximately 0.05–0.08L), such gains may translate into improved ventilatory efficiency and functional reserve, particularly in deconditioned individuals. The most pronounced improvement was observed in oxyhemoglobin saturation, with participants of lower baseline tolerance—especially women—showing increases of up to 1.7 percentage points, thereby narrowing disparities across performance levels. Importantly, the cardiovascular response to the exercise was well within the range of moderate intensity, with heart rate rising by approximately 25 beats per minute, underscoring the safety and feasibility of the test across diverse subgroups. Collectively, these findings highlight the dual role of the two-minute step test: not only as a practical and reliable assessment of functional capacity, but also as a brief physiological intervention capable of enhancing cardiopulmonary function in populations at elevated cardiovascular risk.

Our supplemental analyses provided additional context for these findings. Body composition data (Supplemental

Table S1) highlighted marked sex-related differences in muscle and fat distribution, which may contribute to the observed pulmonary and oxygenation disparities. Importantly, stratified analyses by performance tertiles (Supplemental

Table S3) confirmed that participants with lower exercise capacity also had lower pulmonary function, although this was largely attributable to age. Moreover, heart rate responses remained consistent across sex and performance groups (Supplemental

Tables S4 and S5), underscoring the broad applicability and safety of the test. These supplemental results strengthen the generalizability of our main findings.

Our findings support the hypothesis that short-duration stepping exercise can acutely enhance ventilatory capacity. The observed increases in FVC (+0.05–0.08L) and FEV₁ (+0.04–0.08L) are consistent with previous reports showing that brief physical activity can improve lung expansion and expiratory effort through enhanced respiratory muscle engagement and increased thoracic compliance [

9,

10]. The unchanged FEV₁/FVC ratio suggests that improvements were proportional, reflecting improved global ventilatory efficiency rather than changes in airflow obstruction. The greater gains in PEF among younger males may reflect superior respiratory muscle strength and reserve, in line with prior studies demonstrating sex- and age-related differences in ventilatory mechanics [

11,

12].

Consistent with prior research, individuals with lower baseline performance or older age demonstrated greater improvements in oxygenation following the 2MST. These exploratory findings suggest that deconditioned patients may derive proportionally larger acute benefits. However, the positive change of pulmonary function showed no meaningful association with the number of cardiovascular risk factors, highlighting that cardiopulmonary response may be more strongly influenced by functional status than by risk factor burden. Future studies incorporating standardized cardiovascular risk scores (e.g., Framingham, ASCVD) are needed.

The improvement in SpO₂, particularly among participants with lower baseline exercise tolerance, is of clinical significance. Patients in the lowest tertile of stepping performance started with lower baseline SpO₂ (96.4%) but experienced the greatest improvement (+1.5–1.7 percentage points), effectively narrowing the oxygenation gap with higher-performing individuals. This suggests that even brief stepping exercise can counteract exercise-induced desaturation and enhance oxygen delivery in deconditioned patients. These findings resonate with prior observations that submaximal exercise interventions can improve gas exchange efficiency and oxygen transport in populations with compromised cardiopulmonary reserve [

13]. Notably, the stronger response observed in women may be attributed to lower baseline muscle mass and ventilatory reserve, which allows for greater relative improvement when exercise is introduced [

14]. This study also can gain support from our previous study in Tai Chi Chuan practice which found a 12-month training program significantly improves aerobic capacity and CHD risk factors in patients with dyslipidemia [

15].

Exercise-induced hypoxemia has been implicated in adverse vascular and autonomic responses, including activation of hypoxia-inducible pathways, sympathetic stimulation, and endothelial dysfunction, which may influence coagulation and cardiac electrophysiology in susceptible individuals [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Transient desaturation during exercise has also been associated with heightened sympathetic activity and electrical instability, potentially increasing arrhythmogenic susceptibility, particularly in individuals with underlying cardiovascular risk factors [

20,

21]. Although the present study was not designed to evaluate thrombotic or arrhythmic outcomes, the observed improvement in oxyhemoglobin saturation following the two-minute stepping exercise suggests a potential attenuation of transient hypoxemic exposure during low-intensity functional activity. These observations should be interpreted cautiously and do not imply direct risk modification; rather, they highlight the importance of adequate monitoring and individualized exercise prescription when applying functional exercise tests in populations with elevated cardiovascular risk.

Heart rate increased by approximately 25 bpm across all groups, representing a moderate-intensity cardiovascular load. The uniformity of this response across tertiles suggests that the two-minute stepping test is a safe exercise modality, even for individuals with limited baseline performance. This is consistent with prior studies reporting that the test provides a submaximal yet clinically meaningful cardiovascular challenge without inducing undue stress or adverse events [

15].

The present findings suggest that the two-minute step test may serve not only as a practical tool for assessing functional fitness, but also as a brief, low-intensity exercise stimulus capable of eliciting acute pulmonary and oxygenation responses. Owing to its simplicity, low cost, and minimal space requirements, the test can be readily implemented in outpatient clinics, community-based programs, and rehabilitation settings, particularly for individuals with limited access to structured exercise facilities.

From an exercise science perspective, the movement pattern and physiological demand of the two-minute step test share conceptual similarities with other low-intensity, rhythmical activities such as slow jogging, which has been proposed as a feasible exercise modality for older adults and individuals with chronic disease [

22,

23]. Although slow jogging has been scientifically investigated internationally, there is limited peer-reviewed literature on its application in many counties. Thus, this study may provide scientific evidence supporting the application of slow jogging exercise in exercise training programs for elderly people in Japan and other countries. Rather than suggesting equivalence, these similarities highlight the potential role of stepping-based activities as accessible forms of functional exercise that can be safely performed while eliciting moderate cardiovascular and ventilatory responses [

24,

25].

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study evaluated acute physiological responses to a single bout of the two-minute step test, and therefore the findings should not be extrapolated to long-term adaptations or training effects. Second, the absence of a non-exercise control group limits causal interpretation of the observed changes. Third, the study population consisted of adults with cardiovascular risk factors recruited from a single center, which may limit generalizability to other populations. Finally, although changes in pulmonary function and oxygenation were statistically significant, the effect sizes were modest and should be interpreted within the context of short-duration exercise testing.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that a two-minute step test is associated with acute improvements in pulmonary function and oxyhemoglobin saturation in adults with cardiovascular risk factors. Although the absolute increases in FVC and FEV₁ were modest, these changes were consistently observed across sex and age groups, with greater oxygenation responses among individuals with lower baseline exercise tolerance, particularly women. The test elicited a uniform and moderate cardiovascular response, supporting its safety and feasibility as a low-intensity functional exercise.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Ta-Chen Su, design study, recruit participants, data collection and analyses interpretation, and draft review and critical revision; Chi-Hua Cheng, data interpretation and draft writing, Po-Chun Wang, data interpretation and discussion.

Funding

This study was supported by National Science and Technology Council (NSTC-101-2314-B-002-184-MY3; NSTC-114-2314-B-860-002) Taiwan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital (Approval No. 201501006RIND, approved on April 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and privacy considerations related to human participants.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for all participants for their commitment in completing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Virani, SS; Alonso, A; Aparicio, HJ; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143(8), e254–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, R; Blair, SN; Arena, R; et al. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: A case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134(24), e653–e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B; Zhou, Y; Xiao, L; et al. Association of lung function with cardiovascular risk: a cohort study. Respir Res. 2018, 19(1), 214, Published 2018 Nov 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au Yeung, SL; Borges, MC; Lawlor, DA; Schooling, CM. Impact of lung function on cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular risk factors: a two sample bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Thorax 2022, 77(2), 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatila, WM; Thomashow, BM; Minai, OA; Criner, GJ; Make, BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008, 5(4), 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikli, RE; Jones, CJ. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist 2013, 53(2), 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, RW; Crouch, RH. Two-minute step test of exercise capacity: systematic review of procedures, performance, and clinimetric properties. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2019, 42(2), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghieri, HA; Kanegusuku, H; Corso, SD; et al. Validity and reliability of 2-min step test in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Nurs. 2021, 39(2), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X; Huang, L; Fang, Y; Cai, S; Zhang, M. Physical activity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a scoping review. BMC Pulm Med. Published. 2022, 22(1), 301, Published 2022 Aug 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T; Bai, X; Wei, X; et al. Exercise Rehabilitation and Chronic Respiratory Diseases: Effects, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Benefits. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. Published. 2023, 18, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lázaro, D; Santamaría, G; Sánchez-Serrano, N; Lantarón Caeiro, E; Seco-Calvo, J. Efficacy of therapeutic exercise in reversing decreased strength, impaired respiratory function, decreased physical fitness, and decreased quality of life caused by the post-COVID-19 syndrome. Viruses 2022, 14(12), 2797, Published 2022 Dec 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scano, G; Grazzini, M; Stendardi, L; Gigliotti, F. Respiratory muscle energetics during exercise in healthy subjects and patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2006, 100(11), 1896–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoMauro, A; Aliverti, A. Sex and gender in respiratory physiology. Eur Respir Rev. 2021, 30(162), 210038, Published 2021 Nov 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Thoracic Society; American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167(2), 211–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, C; Su, TC; Chen, SY; Lai, JS. Effect of T’ai chi chuan training on cardiovascular risk factors in dyslipidemic patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2008, 14(7), 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, GL. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factors, and disease pathophysiology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014, 9, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, DP; Joyner, MJ. Compensatory vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise: mechanisms responsible for matching oxygen supply to demand. J Physiol. 2012, 590(24), 6321–6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltzschig, HK; Carmeliet, P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011, 364(7), 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N; Zhao, YY; Evans, CE. The stimulation of thrombosis by hypoxia. Thromb Res. 2019, 181, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, VK; Dyken, ME; Clary, MP; Abboud, FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 1995, 96(4), 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, NR; Peng, YJ. Peripheral chemoreceptors in health and disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004, 96(1), 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenaga, M; Yamada, Y; Kose, Y; et al. Effects of a 12-week, short-interval, intermittent, low-intensity, slow-jogging program on skeletal muscle, fat infiltration, and fitness in older adults: randomized controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017, 117(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H; Jackowska, M. Slow jogging - a multi-dimensional approach to physical activity in the health convention. J Kinesiol Exer Sci 2019, 86, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, DC; Pate, RR; Lavie, CJ; Sui, X; Church, TS; Blair, SN. Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014, 64(5), 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, JJL; Fitzgerald, C; Rand, S. The 2 min step test: A reliable and valid measure of functional capacity in older adults post coronary revascularisation. Physiother Res Int. 2023, 28(2), e1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).