1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have become routine writing tools in education, research, journalism, and commercial content production [

1,

2,

3,

4], intensifying practical concerns about when text should be treated as human-authored, artificial intelligence (AI)-generated, or collaboratively produced. This matters because authorship is now tied to assessment, accountability, and trust, yet the empirical evidence suggests that neither humans nor automated systems can rely on a single, invariant AI signature across contexts. A study by Tengler & Brandhofer [

5] found that pre-service teachers rated AI-generated essays higher on key quality dimensions, while the same texts still showed systematic, rubric-identifiable linguistic differences (e.g., in sentence-structure complexity, vocabulary, and text linking, and overall language construction), demonstrating how fluent AI writing can coexist with measurable cue differences.

At the same time, the detection problem is not only about accuracy but also about

validity and fairness. An evaluation of common GPT detectors reported substantial bias against nonnative English writing, with detectors disproportionately misclassifying these texts as AI-generated, raising concerns about unequal harms if detector outputs are used in educational or publishing decisions [

6]. This evidence aligns with broader field syntheses that frame LLM-generated text detection as highly contingent on domain, language variety, and evaluation design, and caution against treating detector scores as definitive proof of misconduct [

7]. Consistent with these concerns, OpenAI discontinued its own AI text classifier in 2023, explicitly citing low accuracy and shifting emphasis toward provenance-oriented approaches [

8].

Within this fast-moving landscape, empirical studies describe a range of cue families that can differentiate AI from human-authored text, but the field lacks a consolidated, condition-aware map of what those cues are and how robust they remain. Findings from stylometry illustrate the promise and limits of surface-level distributions. For instance, Ippolito et al. [

9] found that humans often performed near chance at identifying machine-generated passages, while an automated discriminator (fine-tuned BERT) achieved markedly higher accuracy, reinforcing that computationally extracted cues can outperform intuitive human-heuristic strategies. However, results like these also highlight the need to treat cues as

probabilistic indicators rather than deterministic markers, since cue strength may vary with genre conventions, sampling length, and writer/model characteristics [

7].

A second major challenge is maintaining cue stability under transformation, since suspicious text is often post-edited, paraphrased, translated, or blended with human writing rather than being a pristine end-to-end LLM output. Robustness studies show that paraphrasing can meaningfully degrade detector performance and undermine detection signals that look strong in static benchmark evaluations. Krishna et al. [

10] demonstrated that paraphrasing attacks can evade several detector families and proposed retrieval-based defenses, directly motivating the need to assess cues under paraphrase and revision conditions rather than only on original generations. Complementary community evaluations further reinforce that distribution shift is central rather than peripheral; for example, contemporary evaluation frameworks in AI-text detection increasingly treat the problem as inherently multidomain, multigenerator, and multilingual, reflecting a field-wide consensus that stability claims are only meaningful when tested across heterogeneous tasks, domains, and linguistic contexts. [

11].

Alongside inference-from-text approaches, provenance methods aim to encode origin signals at generation time. Production-oriented watermarking has advanced rapidly, with a recent paper describing a scalable text watermarking scheme designed to preserve text quality while enabling efficient detection [

12]. Yet provenance is not a complete solution because even when watermarks perform well in controlled settings, real-world pipelines (editing, partial copying, translation, and hybrid authorship) can reduce signal density and complicate detection—again returning attention to stability under realistic transformations and mixed-authorship scenarios [

7].

Given these pressures, a timely synthesis is needed that does two things: (1) identifies which cue families the empirical literature actually reports as distinguishing AI vs human text, and (2) evaluates how stable those cues appear across tasks, genres/registers, lengths, and revision conditions. Accordingly, this rapid review addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What cue families are described in the empirical literature as distinguishing AI vs human text?

RQ2: How stable are these cues across tasks, genres, lengths, and revision conditions?

By organizing findings around cue families and explicitly foregrounding stability conditions, the review aims to support decision-relevant interpretation of both human-facing markers and computational detection signals, while clarifying where current evidence is strong, where it is conditional, and where it remains insufficient for high-stakes use [

13].

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

We reported this rapid review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020, where applicable, and the interim guidance for reporting rapid reviews. At the time of writing, PRISMA-RR (a PRISMA extension for rapid reviews) is under development, so we used interim rapid review reporting recommendations to support transparent reporting [

14]. We adopted a rapid review approach because our aim was to provide a timely, decision-relevant synthesis of empirical evidence on cues used to distinguish AI-generated vs human-written text, and to map how stable these cues appear across contexts (tasks, genres, length, and revision/paraphrasing). Rapid reviews are a form of knowledge synthesis that accelerates the conduct of a traditional systematic review by using abbreviated or streamlined methods, while retaining a structured and transparent approach to identifying and synthesizing evidence [

15,

16]. This approach is particularly suitable for the present topic because the empirical literature on LLM-generated text is fast-moving, methodologically diverse, and directly tied to operational needs in education, publishing, and research integrity; therefore, an expedited synthesis is needed to support near-term decisions and to identify the most urgent evidence gaps.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We included original empirical manuscripts published in peer-reviewed journals between 1 January 2022 and 1 January 2026. Eligible studies examined differences between AI-generated and human-written text and reported extractable evidence about cues that distinguish AI from human writing, including surface, discourse/pragmatic, epistemic/content, predictability/probabilistic, or provenance cues. Studies were included if they used computational analyses (e.g., feature-based classifiers, detector evaluations, stylometric/corpus analyses) and/or human judgment designs (e.g., reader identification of AI vs human text) as long as they involved a direct AI–human text comparison. We excluded publications that were non-empirical, did not focus on text, or did not provide data relevant to distinguishing AI vs human writing. Only manuscripts written in English were considered.

2.3. Information Sources

Relevant papers were identified from the following databases: Scopus, ERIC, IEEE, and Academic Search Ultimate.

2.4. Search

The initial search was done by the author on November 5, 2025, while the final search was done on January 3, 2026. An experienced librarian guided the author regarding the search strategy. We used key terms that were relevant to the scope of this review to find the appropriate studies. These key terms covered the following concepts: AI, human, detection, and indicators. The terms associated with all concept areas were searched against each other. We used the Boolean operators AND and OR for the combination of different terms. We exported all references to RefWorks (ProQuest) to remove duplicates and to perform the final screening. The search protocol can be found in Supplementary File 1.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

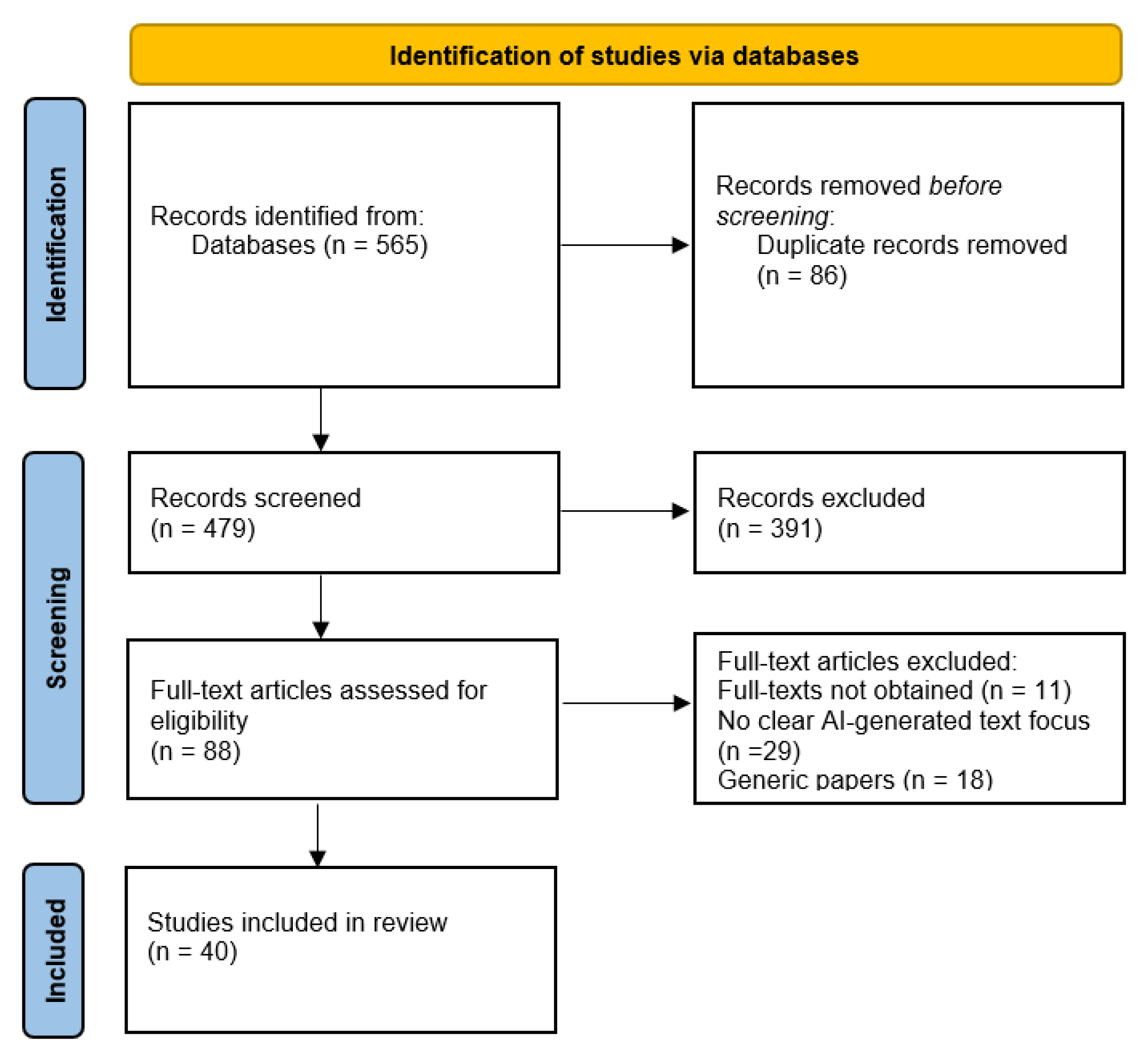

After applying all the above criteria, 565 papers were pulled from the database search. Eighty-six studies were removed as they were duplicates. The number of studies that were screened was 479. Of these, 391 studies were excluded after a comprehensive review of their titles and abstracts because (a) they did not report empirical evidence relevant to distinguishing AI-generated vs human-written text, (b) the papers were not in the English language, and (c) the papers were not published in peer-reviewed journals. The full texts of 88 studies were assessed for eligibility, and only 40 studies were included for qualitative analysis. Forty-eight studies were excluded for several reasons; e.g., because their full-texts could not be obtained, there was no clear AI-generated text focus, they were generic papers on detectors, etc. The following studies were included [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. The full list of the studies can be found in Supplementary File 2.

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of article selection.

3.2. RQ1: Cue Families Distinguishing AI- vs Human-Authored Text

3.2.1. Overview of cue Families in the Qualified Literature

Across the qualified papers, empirical work consistently describes five cue families used to distinguish AI-generated from human-authored text: surface cues (lexical, morphosyntactic, stylometric, readability), discourse/pragmatic cues (metadiscourse, stance, rhetorical organization, register alignment), epistemic/content cues (grounding, evidentiality, plausibility, hallucination/deception markers), predictability/probabilistic cues (likelihood/perplexity/entropy-style signals and detector scores), and provenance cues (watermarking and related statistical tests). Studies vary in whether they treat these cues as (i) directly interpretable linguistic properties, (ii) features inside supervised/unsupervised classifiers, or (iii) signals exploited by deployed detectors. Within the qualified set, surface and discourse/pragmatic cues dominate linguistically oriented comparisons, while predictability/probabilistic cues are most visible in detector benchmarking and adversarial stress-testing; provenance cues are concentrated in watermarking research. Evidence also shows that cue descriptions often overlap; e.g., stylometry is operationalized as surface cues but is sometimes interpreted through discourse-level regularities or genre/register alignment. This is clearest in genre-anchored academic discourse studies and stylometric delta approaches that explicitly frame style distance as more than token-level counts [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

3.2.2. Surface Cues

Surface cues appear throughout the qualified literature as measurable differences in lexical distribution, morphosyntax, and stylistic form. Multiple studies compare AI-generated and human-written texts in educational and academic contexts using lexical/syntactic profiles, commonly operationalizing differences through lexical diversity/complexity, part-of-speech (POS) or syntactic-pattern distributions, and readability/structure indices [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. In EFL and applied linguistics contexts, surface measurements are frequently paired with genre framing, positioning surface cues as signals of how successfully outputs pass as disciplinary or learner writing [

17,

23,

24].

A substantial subset of the qualified work is explicitly stylometric: AI/human separation is modeled via function-word usage, punctuation patterns, n-grams (character/word/POS), and distance-based authorship methods. Burrows-style delta operationalizes authorship as a distance over frequent word distributions and related stylistic fingerprints, treating AI-vs-human distinction as fundamentally authorial style at scale [

28]. Related stylometric evidence in Japanese shows strong separability using stylistic fingerprints, while emphasizing that humans may struggle to identify AI authorship compared to stylometric systems [

29,

30]. Complementary stylometry-oriented detection work emphasizes the utility of short-sample style signals, suggesting that discriminative cues can persist even when texts are short (and therefore harder for content-based methods) [

31]. An unsupervised and interpretable stylometric delta (trigram–cosine delta) further reinforces the surface-family emphasis by modeling AI/human differences as systematic distance in stylometric space rather than as topic- or task-specific content patterns [

19]. Additional feature-centric approaches explicitly extract linguistic features automatically and use them for classification, reflecting a broad empirical assumption that AI outputs exhibit detectable regularities in surface form that remain informative even when the downstream classifier is not itself interpretable [

25,

32].

Finally, several qualified papers embed surface cues in more applied detection evaluations. A deep learning classifier study treats AI-vs-human distinction as a learnable mapping from text to label, typically absorbing surface cues (and potentially some discourse/content cues) as part of the learned representation rather than explicitly enumerating them [

32]. Explainability-oriented attribution work (when applied to AI/human or multi-LLM differentiation) similarly relies on feature importance or explanatory mechanisms to surface which parts of a learned representation align with stylometric or structural differences [

33,

34].

3.2.3. Discourse/Pragmatic Cues

Discourse/pragmatic cues are particularly salient in the academic-writing and applied-linguistics subset of the qualified studies. A genre-based comparison of AI-generated versus human-authored applied linguistics abstracts frames differences partly in how rhetorical moves and metadiscourse resources are deployed to organize claims, guide readers, and position the author, treating these as systematic discriminators beyond surface form [

17]. Related work on academic discourse in the social sciences similarly conceptualizes AI-vs-human distinction through how academic discourse conventions are realized, supporting the view that pragmatic packaging and rhetorical organization are central cue sources in scholarly genres [

35]. Disciplinary-variation research reinforces this by showing that discourse-level resources can vary by field and that AI outputs may partially approximate disciplinary patterns while still differing in finer-grained metadiscourse distribution, an observation that effectively treats disciplinary fit as a pragmatic cue layer [

36].

Stance is repeatedly treated as a pragmatic discriminator, especially in academic abstracts and evaluative genres. A stance-focused abstract study emphasizes differences in stance orientation and rhetorical positioning, placing stance among the core cue families distinguishing AI-generated and human-authored academic texts [

22]. Extending beyond abstracts, a metadiscourse-based comparison of academic book reviews explicitly frames the question of whether AI can emulate human stance; in doing so, it identifies metadiscourse/stance as key discriminators even when surface cues are held constant or when texts are produced to imitate genre norms [

37]. At a more integrative level, a comparative linguistic analysis framework explicitly organizes the AI-vs-human distinction as multi-level, namely surface form plus discourse organization plus pragmatic function, providing a scaffold that aligns closely with your cue-family taxonomy and supports treating pragmatic organization as a parallel cue family rather than a derivative of surface style [

18]. Results from EFL academic-writing comparisons also tend to conjoin surface indicators with discourse organization, indicating that in learner-adjacent settings, authenticity judgments are rarely reducible to surface cues alone [

17,

23,

24].

3.2.4. Epistemic/Content Cues

A third cue family in the qualified set concerns epistemic and content properties; how claims are grounded, how information quality is conveyed, and how plausibility or evidentiality is signaled. Studies of AI-authored narratives and reviews foreground the role of hallucination-like or experience-without-experience content. Marketing narrative comparisons explicitly include evaluations of content authenticity and plausibility, highlighting epistemic reliability as a differentiator in experiential genres [

38]. A hotel-review study contrasts inherently false AI communication with intentionally false human communication and treats the epistemic status of claims (and their linguistic correlates) as part of what distinguishes sources, positioning deception-related content markers as relevant epistemic cues [

39]. Work on fake reviews at scale similarly situates the distinction among AI-generated, human-generated fake, and authentic reviews as partly a content/intent problem (not only a stylistic one), supporting a view where epistemic and communicative intent can leave measurable traces [

40].

Epistemic/content cues are also visible in scholarly writing and scientific-communication contexts. A benchmark dataset of machine-generated scientific papers is motivated by the need to distinguish machine-generated from human-written scientific writing, implicitly centering concerns about content reliability, scientific plausibility, and signal quality (even when the operationalization may rely on surface/probabilistic features) [

41]. Related educational work on fact-check pedagogy uses the limitations of generative AI as an instructional object, aligning with the broader epistemic framing, namely, the fact that AI systems can produce fluent outputs that require verification, and that verification gap itself becomes part of how AI-authoredness is conceptualized [

42]. In adjacent evaluation studies comparing LLMs with human researchers on complex medical queries—and comparing summarization performance between LLMs and medical students—the primary outcome is not detection, but the findings nevertheless reinforce that epistemic/content properties are central to how human vs AI writing is assessed in high-stakes informational settings [

43,

44].

3.2.5. Predictability/Probabilistic Cues

Predictability/probabilistic cues appear most clearly in the qualified papers that evaluate detectors or study evasion. Stress-testing work explicitly targets AI text detectors under multiple attacks, placing predictability-based signals (and detector score stability) at the center of empirical detectability claims; this line of evidence treats AI-vs-human discrimination as contingent on statistical regularities that can be intentionally perturbed [

45]. Evasion research complements this by showing that LLMs can be guided to produce outputs that defeat detector heuristics, reinforcing the idea that probabilistic cues are not only widely used but also sensitive to adaptive generation strategies [

46]. In applied settings, detector benchmarking across tools and generators (e.g., Turnitin/GPTZero-style tools across multiple LLMs) positions detectability as a function of detector assumptions and generator variety, again implying that probabilistic cue families can shift across models and conditions even when surface and discourse properties appear human-like [

47]. A fairness-focused evaluation adds that detector accuracy can trade off with bias, underscoring that probabilistic cues exploited by detectors may interact with writer characteristics or distributional differences in non-trivial ways [

48].

Several qualified studies contribute to this family indirectly by using machine-learning classifiers (including deep learning) and explainable AI pipelines for attribution. These methods often blend surface, discourse, and probabilistic signals; explainability work is relevant here because it aims to reveal which features (or which textual regions) contribute most to probabilistic decisions, thereby providing empirical bridges between probability-based detectability and human-interpretable cue families [

32,

33,

34].

3.2.6. Provenance Cues

Provenance cues, and especially watermarking, constitute a distinct line of work because they aim to provide an explicit origin signal rather than inferring authorship from linguistic correlates. The statistical framework for watermark detection formalizes distinguishability in terms of detection efficiency and decision rules, treating provenance as a statistically testable property [

49]. Complementing this, adaptive testing for segmenting watermarked text addresses the practical scenario of mixed or partially edited text by seeking to localize watermarked spans, thereby positioning segmentation/localization as part of the provenance cue family [

50]. Importantly, provenance cues are also implicated in detector stress-testing because adversarial perturbations and revision conditions can threaten watermark detectability; thus, the watermarking line sits at the intersection of provenance and robustness concerns, even when the cue is not linguistic style per se [

45,

49,

50].

Finally, several qualified papers do not primarily aim to enumerate detection cues but still shape how cue families are interpreted in applied settings. Work on preserving authorial voice situates AI-assisted revision within authenticity concerns and implicitly motivates why discourse-level cues (voice, stance, rhetorical habits) matter for distinguishing AI contribution from human authorship, particularly in academic contexts [

51]. Infrastructure-focused work on AI-assisted academic authoring further reinforces that authorship may be hybrid (human + AI touch-up), which complicates cue interpretation and pushes the field toward cues that can handle partial or edited AI contributions [

52,

53]. Studies of human evaluation, such as preliminary explorations of human techniques to separate student-authored from ChatGPT-generated text, underscore that cue families described in empirical work are not always those used successfully by humans, motivating triangulation between human judgments and computational cue families [

29,

54]. More interpretive work on machine creativity and literary creation is not detection-centric, but it contextualizes why discourse and epistemic cues (voice, originality, intentionality) become salient when authenticity is evaluated beyond mere classification accuracy [

38,

55].

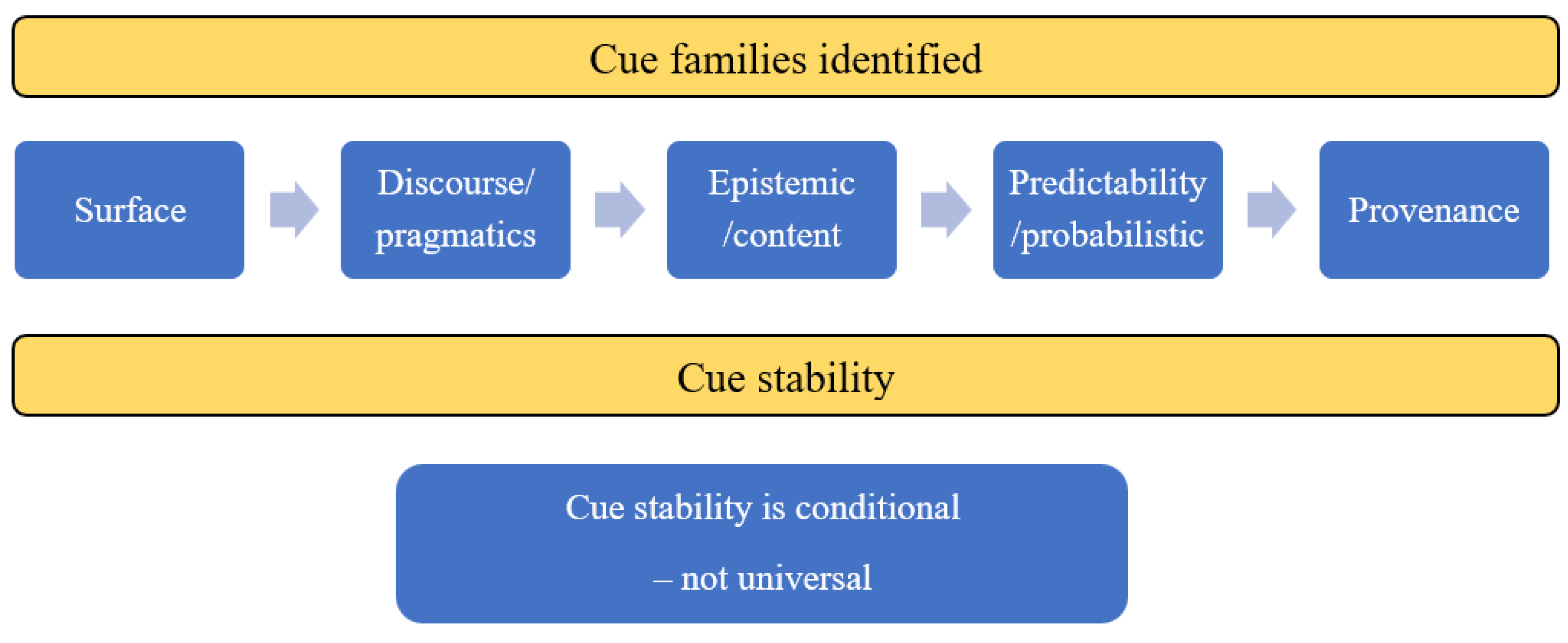

Taken together, the qualified evidence supports a multi-family account of AI-vs-human distinction: surface cues provide strong discriminative signals in stylometry and feature-based classification; discourse/pragmatic cues differentiate rhetorical packaging and stance in genre-bound texts; epistemic/content cues capture grounding, plausibility, and simulated experience; predictability/probabilistic cues underpin many deployed detectors but are sensitive to attack and distribution shift; and provenance cues provide an explicit origin signal via watermarking but require robustness to editing and mixing. The main findings are concentrated in

Table 1.

3.3. RQ2: Cue Stability Across Tasks, Genres, Lengths, and Revision Conditions

3.3.1. Overview of the Qualified Studies Regarding Cue Stability

Across the included studies, stability is not reported as a single, invariant property of AI text, but as a conditional outcome that depends on (i) task and genre/register constraints, (ii) revision operations (especially paraphrasing and mixed authorship/AI touch-up), and (iii) the detector threat model (attacks and deliberate evasion). Genre-based linguistic comparisons indicate that cues can remain discriminative within constrained academic forms yet shift in distribution as writers (or models) align with disciplinary conventions and rhetorical templates [

17,

18,

35]. Detector-focused work shows that predictability-based signals exploited by common detectors can deteriorate under targeted perturbations and adversarial generation strategies [

45,

46]. Direct paraphrasing evidence demonstrates that post-processing can meaningfully disrupt detectable signals, emphasizing that stability must be evaluated under realistic revision workflows [

56]. Provenance research further reframes stability as robustness of an explicit origin signal under editing and mixing, with adaptive segmentation proposed for realistic partial provenance settings [

50].

3.3.2. Stability Across Tasks, Genres, and Registers

The strongest genre/task support comes from studies that explicitly situate AI–human differences within genre conventions. A genre-based comparison of applied linguistics abstracts shows that AI-generated and human-authored abstracts share the same macro-structural constraints of the abstract genre, while still differing systematically in linguistic and rhetorical realizations, implying that cue stability is partly genre-bounded and best interpreted relative to genre norms rather than as a genre-invariant signature [

17]. A corpus-driven comparison of academic discourse in the social sciences similarly frames AI–human differences within disciplinary discourse practices, suggesting that stability depends on whether cues are tied to general style versus discipline-specific rhetorical packaging [

35]. A comparative linguistic framework reinforces this multi-level view by treating stability as potentially different for surface, discourse/pragmatic, and epistemic cue families, which provides an explanatory account for why certain cues appear stable in one genre but weaken or change in another [

18]. Evidence from educational writing converges on the same conclusion. Comparisons in EFL academic writing highlight variation arising from controlled task ecologies (prompted writing, classroom norms, learner profiles), suggesting that stability is best interpreted at the level of cue families (surface, discourse, epistemic) rather than as fixed AI signatures across writing contexts. [

23]. In narrative-style tasks, stylometric comparisons of short story adaptations also imply that what remains stable depends on the stylistic latitude and conventions of the genre itself, making cross-genre generalization non-trivial [

24]. Collectively, these studies support the inference that register- and genre-aware modeling is central to stability, and that stability claims should be anchored to explicitly comparable writing situations [

17,

18,

23,

24,

35].

3.3.3. Stability Under Length Constraints and Short Samples

Length interacts with stability because many cues become noisier as text shortens. Empirical stylometry work indicates that discrimination can remain effective in short samples, suggesting that at least some surface-style signals persist under length reduction [

31]. An unsupervised, interpretable stylometric delta approach similarly models detection as distance in stylometric space, which is intended to remain usable without long documents or extensive training regimes [

19]. In contrast, provenance-based approaches show the opposite pressure point because when the relevant signal-bearing span is small or interleaved with non-signal text, identification becomes a segmentation/localization problem. Adaptive testing for segmenting watermarked text explicitly addresses this scenario, indicating that provenance stability is threatened by partial inclusion and mixing, and must be recovered through statistical localization procedures [

50]. Thus, the evidence suggests relatively stronger short-text resilience for stylometric surface cues than for provenance cues, which require explicit procedures when signal density is reduced [

19,

31,

50].

3.3.4. Stability Under Revision, Paraphrasing, and Mixed Authorship

Revision conditions emerge as a major destabilizer of cues. The paraphrasing-focused study provides direct proof that human-written paraphrases of LLM-generated text affect detectability, demonstrating that revision can attenuate or redistribute the signals detectors rely on [

56]. This aligns with detector robustness work showing that transformations and perturbations—many of which mimic plausible editing processes—can change detection outcomes [

45]. Mixed authorship is addressed explicitly in work that distinguishes fully AI-generated text from AI touch-up, implying that stability cannot be evaluated only at the endpoints (pure AI vs pure human); instead, cues may weaken gradually as humans edit AI drafts, complicating attribution in realistic workflows [

53]. Complementing this, infrastructure-focused work on AI-assisted academic authoring normalizes hybrid production pipelines and thereby strengthens the inference that revision and co-authoring are not edge cases but likely dominant contexts in which stability should be tested [

52].

Overall, the included studies support the convergent conclusion that cue stability is best described as family-level stability with pattern-level variability, and the most reliable stability claims are those bound to explicit conditions. Surface stylometric cues can remain informative under short-text constraints and across some task settings, but their realized patterns vary by genre and register Discourse/pragmatic cues show partial stability within academic genres yet are strongly conditioned by disciplinary conventions and rhetorical templates, limiting cross-genre transfer Epistemic/content cues depend on task demands for grounding and plausibility and are especially sensitive to revision workflows and hybrid authorship. Predictability/probabilistic cues underpin many deployed detectors but are among the least stable under paraphrasing, attacks, and evasion; they also exhibit distributional fragility and fairness-related trade-offs. Provenance cues shift the stability problem toward robust statistical detection under mixing and partial-span conditions, motivating segmentation/localization approaches. Finally, cross-lingual/domain work and the broader review literature underscore that the distribution shift remains a central challenge for stability, supporting the need for explicit condition-centered evaluation rather than universal claims. The main findings are presented in

Table 2.

Figure 2 illustrates a summary of the findings for both research questions.

4. Discussion

This rapid review set out to identify which cue families are used to distinguish AI-generated from human-authored text and assess how stable those cues appear across genres/tasks, text length, and revision/paraphrasing. The findings indicate convergent use of five cue families (surface; discourse/pragmatic; epistemic/content; predictability/probabilistic; provenance) and, crucially, that stability is conditional rather than universal. Below, we interpret these findings in relation to the broader detection literature and show how external evidence helps explain the patterns observed in our included studies.

4.1. Cue Families Distinguishing AI- vs Human-Authored Text

Our results show surface cues to be the most pervasive family across the qualified literature, spanning direct linguistic comparisons and feature-based classification. This prominence is consistent with foundational stylometry and authorship-attribution research, as frequent-word distributions, function words, and character/word n-grams capture relatively topic-robust regularities that support discrimination in controlled settings. Foundational stylometry work emphasizes that such representations often generalize well when sampling and genre are controlled [

57,

58]. Interpreting our findings through this lens clarifies why many studies in our sample treat AI–human separation as a stylometric problem, since even when modern classifiers are used, they often exploit the same distributional regularities that stylometry has long documented.

We found that discourse/pragmatic cues are especially salient in academic and applied-linguistics contexts, where texts are shaped by strong genre norms and disciplinary expectations. Discourse scholarship predicts that academic writing is not only fluent propositional content, but also interpersonal and rhetorical positioning (stance, engagement, and reader guidance) that encodes community membership and epistemic caution. Hyland’s stance-and-engagement model provides a well-established account of these interactional resources in academic argumentation, while register research (e.g., university registers) shows systematic variation in stance marking across spoken/written academic contexts [

59,

60]. These frameworks help explain why our included academic-genre studies repeatedly identify stance and metadiscourse differences even when surface fluency is high: pragmatic packaging is a plausible second layer of discriminability beyond lexical/syntactic form. Furthermore, epistemic/content cues are positioned as a distinct family that becomes salient where truthfulness, grounding, and experience matter. This aligns with a large body of work on hallucination in neural generation, which documents systematic tendencies for fluent but ungrounded or fabricated content across natural language generation tasks [

61]. At the same time, further evidence also supports the caution implied by our synthesis, since epistemic unreliability is not a unique marker of AI authorship (humans can err or deceive), but it becomes practically important as a cue family because it links attribution concerns to verification and risk (e.g., academic integrity, health/science communication) [

62].

Moreover, predictability/probabilistic cues are concentrated in detector benchmarking and robustness studies. The broader technical literature makes clear why. Some approaches operationalize AI-ness via statistical regularities in token-choice patterns. GLTR provides an interpretable, human-facing instantiation (token probability ranks) and DetectGPT proposes a zero-shot criterion based on probability curvature under perturbations [

63,

64]. These lines of work illuminate that probabilistic cues can be powerful, but they often sit at a distance from human-interpretable linguistics, which partly explains why our included studies treat them as detector

signals rather than as stable descriptive properties of text. Finally, our results identify provenance cues as a distinct cluster, largely watermarking-focused. External provenance research frames this as an alternative paradigm; rather than inferring authorship from correlates (style/probability), watermarking encodes an origin signal at generation time and detects it statistically. The green-list watermark proposal and subsequent production-oriented watermarking schemes (e.g., SynthID-Text) formalize provenance as a detectable statistical pattern with an explicit detection procedure. [

12,

65]. This helps interpret why provenance studies in our corpus emphasize localization/segmentation and robustness: the key question is not

what does AI text look like?, but

does the origin signal survive realistic reuse and editing?.

4.2. Stability of Cues Across Contexts, Length, and Revision/Paraphrasing

Across our included studies, stability was not treated as an invariant AI signature, but as conditional on genre/task constraints, revision operations, and the detector threat model. The results highlight paraphrasing and post-editing as major sources of cue instability. Previous findings corroborate this directly, as paraphrasing has been shown to evade a range of AI-text detectors, with retrieval-based approaches proposed as a partial defense [

10]. Stress-testing work further demonstrates that recursive paraphrasing can degrade detection performance across detector families, emphasizing that detector success in static test sets can fail under realistic editing workflows [

66]. These findings align closely with our reviewed work that stability claims must be tethered to explicit assumptions about revision depth and adversarial intent.

Furthermore, the results suggest that cue patterns may remain discriminative within constrained academic genres, yet vary with discipline/register. External benchmarks reinforce the broader point since generalization across domains and languages remains a central challenge. MULTITuDE provides large-scale multilingual evaluation and demonstrates performance variability across languages and model conditions, supporting our conclusion that stability is best asserted under explicitly delimited contexts [

67]. Shared-task evidence similarly underscores multidomain/multimodel variability. For example, SemEval-2024 Task 8 was explicitly designed around multigenerator, multidomain, and multilingual detection, reflecting field consensus that distribution shift is a core, not peripheral, evaluation condition [

11]. Surface stylometric cues can remain informative under short-text constraints, whereas provenance detection becomes more difficult under partial-span/mixing conditions. Stylometry leverages high-frequency distributional signals that can sometimes persist in shorter samples (though reliability typically improves with longer text), while watermarking and likelihood-based signals often require sufficient token mass for stable statistical testing [

64]. We can therefore infer that stability is not uniform even within a cue family since it depends on signal density and the statistical regime required by the method.

In addition, our findings note fairness trade-offs in detector work, indicating the seriousness of this stability constraint. A study shows that GPT detectors can misclassify nonnative English writing as AI-generated at substantially higher rates than native writing, implying that detector cues are entangled with population-level variation in language use [

6]. This is a decisive form of instability; a cue that behaves differently across writer groups is not stable in deployment, even if aggregate accuracy appears acceptable. Finally, our conditional-stability synthesis is consistent with prominent reports that general-purpose detection remains difficult in practice. OpenAI discontinued its AI text classifier, citing low accuracy, and recent surveys consolidate a similar conclusion that detector performance is highly contingent on model, domain, language, and post-processing, with out-of-distribution and attack robustness as persistent gaps [

7].

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its conclusions. First, as a rapid review, we used streamlined procedures that may increase the likelihood of missing relevant studies compared with a full systematic review, even though an experienced librarian supported the strategy. Second, eligibility was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 1 January 2022 and 1 January 2026; this decision likely excluded relevant evidence from non-English contexts and from fast-moving publication channels (e.g., conference proceedings and preprints), which are influential in AI-text detection research. Third, the included studies were methodologically heterogeneous (corpus-linguistic comparisons, feature-based models, detector benchmarks, stress tests, watermarking), which supports mapping cue families but limits comparability across studies and precludes quantitative synthesis or pooled effect estimates. Fourth, cue stability was not operationalized consistently, as studies differed in genres, tasks, generators/models, prompting/decoding settings, text lengths, and the nature and intensity of revision/paraphrasing, constraining the strength of cross-study generalizations. Finally, because many included papers reported detector performance or composite feature models without fully specifying feature sets, preprocessing, or model settings, the review’s ability to attribute findings to particular cue mechanisms (rather than to dataset or pipeline choices) was sometimes limited.

Future research should prioritize standardized, condition-explicit evaluation of cue families. This includes (a) reporting cue definitions and extraction pipelines in sufficient detail to support replication and cross-study comparison; (b) systematically testing cue behavior under realistic workflows, including graded post-editing and paraphrasing, mixed-authorship (AI touch-up), and length-controlled conditions; and (c) documenting generation settings (model/version, prompting strategy, decoding parameters) alongside any downstream editing. Progress would also benefit from shared benchmarks and protocols that evaluate linguistic cue families, detector outputs, and provenance methods on the same datasets, enabling direct comparison of interpretability, robustness, and failure modes under distribution shift. Finally, because stability and error patterns can vary across contexts and writer populations, future studies should routinely include subgroup analyses and context-sensitive validation so that claims about cue robustness translate more safely to educational, publishing, and research-integrity settings.

5. Conclusions

In sum, the included studies and the broader literature converge on a pragmatic takeaway: there is no single, stable AI signature. Detectability arises from layered cue families whose usefulness depends on genre constraints, revision workflows, and adversarial conditions. Surface and discourse/pragmatic cues often discriminate well within controlled genre contexts; probabilistic cues underpin many detectors but are fragile under paraphrase and evasion; provenance cues are conceptually attractive but must be engineered for robustness under real-world editing and mixing. At the policy level, fairness findings and stakeholder guidance collectively argue for detection as decision support within transparent, human-accountable integrity systems, not as an automated substitute for them.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Phonetic Lab of the University of Nicosia.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no competing interests to disclose.

References

- Neumann, A. T., Yin, Y., Sowe, S., Decker, S., & Jarke, M. (2025). An LLM-driven chatbot in higher education for databases and information systems. IEEE Transactions on Education, 68(1), 103–116.

- Rane, N. L., Tawde, A., Choudhary, S. P., & Rane, J. (2023). Contribution and performance of ChatGPT and other Large Language Models (LLM) for scientific and research advancements: a double-edged sword. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, 5(10), 875-899.

- Cheng, S. (2025). When Journalism meets AI: Risk or opportunity?. Digital Government: Research and Practice, 6(1), 1-12.

- Chkirbene, Z., Hamila, R., Gouissem, A., & Devrim, U. (2024, December). Large language models (llm) in industry: A survey of applications, challenges, and trends. In 2024 IEEE 21st International Conference on Smart Communities: Improving Quality of Life using AI, Robotics and IoT (HONET) (pp. 229-234). IEEE.

- Tengler, K., & Brandhofer, G. (2025). Exploring the difference and quality of AI-generated versus human-written texts. Discover Education, 4(1), 113.

- Liang, W., Yuksekgonul, M., Mao, Y., Wu, E., & Zou, J. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns, 4(7).

- Wu, J., Yang, S., Zhan, R., Yuan, Y., Chao, L. S., & Wong, D. F. (2025). A survey on llm-generated text detection: Necessity, methods, and future directions. Computational Linguistics, 51(1), 275-338.

- Kirchner, J. H., Ahmad, L., Aaronson, S., & Leike, J. (2023, January 31). New AI classifier for indicating AI-written text. OpenAI. https://openai.com/index/new-ai-classifier-for-indicating-ai-written-text/.

- Ippolito, D., Duckworth, D., Callison-Burch, C., & Eck, D. (2020). Automatic detection of generated text is easiest when humans are fooled. In Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (pp. 1808-1822).

- Krishna, K., Song, Y., Karpinska, M., Wieting, J., & Iyyer, M. (2023). Paraphrasing evades detectors of ai-generated text, but retrieval is an effective defense. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 27469-27500.

- Wang, Y., Mansurov, J., Ivanov, P., Su, J., Shelmanov, A., Tsvigun, A., ... & Nakov, P. (2024). Semeval-2024 task 8: Multidomain, multimodel and multilingual machine-generated text detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.14183.

- Dathathri, S., See, A., Ghaisas, S., Huang, P. S., McAdam, R., Welbl, J., ... & Kohli, P. (2024). Scalable watermarking for identifying large language model outputs. Nature, 634(8035), 818-823.

- Fiedler, A., & Döpke, J. (2025). Do humans identify AI-generated text better than machines? Evidence based on excerpts from German theses. International Review of Economics Education, 49, 100321.

- Stevens, A., Hersi, M., Garritty, C., Hartling, L., Shea, B. J., Stewart, L. A., ... & Tricco, A. C. (2025). Rapid review method series: interim guidance for the reporting of rapid reviews. BMJ evidence-based medicine, 30(2), 118-123.

- Hamel, C., Michaud, A., Thuku, M., Skidmore, B., Stevens, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., & Garritty, C. (2021). Defining rapid reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 129, 74-85.

- Tricco, A. C., Straus, S. E., Ghaffar, A., & Langlois, E. V. Rapid reviews for health policy and systems decision-making: more important than ever before. Syst Rev. 2022; 11 (1): 153.

- El-Dakhs, D. A. S., Afzaal, M., & Siyanova-Chanturia, A. (2026). A Genre-Based Comparison of Chat-GPT-Generated Abstracts Versus Human-Authored Abstracts: Focus on Applied Linguistics Research Articles. Corpus Pragmatics, 10(1), 1.

- Culda, L. C., Nerişanu, R. A., Cristescu, M. P., Mara, D. A., Bâra, A., & Oprea, S. V. (2025). Comparative linguistic analysis framework of human-written vs. machine-generated text. Connection Science, 37(1), 2507183.

- Salnikov, E., & Bonch-Osmolovskaya, A. (2025). Detecting LLM-Generated Text with Trigram–Cosine Stylometric Delta: An Unsupervised and Interpretable Approach. Journal of Language and Education, 11(3), 138-151.

- Berriche, L., & Larabi-Marie-Sainte, S. (2024). Unveiling ChatGPT text using writing style. Heliyon, 10(12).

- Schaaff, K., Schlippe, T., & Mindner, L. (2024). Classification of human-and AI-generated texts for different languages and domains. International Journal of Speech Technology, 27(4), 935-956.

- Zhang, M., & Zhang, J. (2025). Human-written vs. ChatGPT-generated texts: Stance in English research article abstracts. System, 134, 103842.

- AbdAlgane, M., Ali, R., Othman, K., Ibrahim, I. Z. A., Alhaj, M. K. M., MT, E., & Ali, F. S. A. (2026). Exploring AI-generated texts vs. human-written texts in EFL academic writing: A case study of Qassim University in Saudi Arabia. World, 16(2), 114-131.

- Emara, I. F. (2025). A linguistic comparison between ChatGPT-generated and nonnative student-generated short story adaptations: a stylometric approach. Smart Learning Environments, 12(1), 36.

- Georgiou, G. P. (2025). Differentiating Between Human-Written and AI-Generated Texts Using Automatically Extracted Linguistic Features. Information, 16(11), 979.

- Herbold, S., Hautli-Janisz, A., Heuer, U., Kikteva, Z., & Trautsch, A. (2023). A large-scale comparison of human-written versus ChatGPT-generated essays. Scientific reports, 13(1), 18617.

- Amirjalili, F., Neysani, M., & Nikbakht, A. (2024, March). Exploring the boundaries of authorship: A comparative analysis of AI-generated text and human academic writing in English literature. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 9, p. 1347421). Frontiers Media SA.

- Zhu, H., & Lei, L. (2025). Detecting authorship between generative AI models and humans: a Burrows’s Delta approach. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, fqaf048.

- Zaitsu, W., Jin, M., Ishihara, S., Tsuge, S., & Inaba, M. (2025). Stylometry can reveal artificial intelligence authorship, but humans struggle: A comparison of human and seven large language models in Japanese. PLoS One, 20(10), e0335369.

- Zaitsu, W., & Jin, M. (2023). Distinguishing ChatGPT (-3.5,-4)-generated and human-written papers through Japanese stylometric analysis. PLoS One, 18(8), e0288453.

- Przystalski, K., Argasiński, J. K., Grabska-Gradzińska, I., & Ochab, J. K. (2026). Stylometry recognizes human and LLM-generated texts in short samples. Expert Systems with Applications, 296.

- Kayabas, A., Topcu, A. E., Alzoubi, Y. I., & Yıldız, M. (2025). A deep learning approach to classify AI-generated and human-written texts. Applied Sciences, 15(10), 5541.

- Yan, S., Wang, Z., & Dobolyi, D. (2025). An explainable framework for assisting the detection of AI-generated textual content. Decision Support Systems, 114498.

- Najjar, A. A., Ashqar, H. I., Darwish, O., & Hammad, E. (2025). Leveraging explainable ai for llm text attribution: Differentiating human-written and multiple llm-generated text. Information, 16(9), 767.

- Tudino, G., & Qin, Y. (2024). A corpus-driven comparative analysis of AI in academic discourse: Investigating ChatGPT-generated academic texts in social sciences. Lingua, 312, 103838.

- Zhang, M., & Zhang, J. (2025). Disciplinary variation of metadiscourse: A comparison of human-written and ChatGPT-generated English research article abstracts. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 76, 101540.

- Yao, G., & Liu, Z. (2025). Can AI simulate or emulate human stance? Using metadiscourse to compare GPT-generated and human-authored academic book reviews. Journal of Pragmatics, 247, 103-115.

- Wen, Y., & Laporte, S. (2025). Experiential narratives in marketing: A comparison of generative AI and human content. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 44(3), 392-410.

- Markowitz, D. M., Hancock, J. T., & Bailenson, J. N. (2024). Linguistic markers of inherently false AI communication and intentionally false human communication: Evidence from hotel reviews. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 43(1), 63-82.

- Zhao, Y., Tang, S., Zhang, H., & Lyu, L. (2025). AI vs. human: A large-scale analysis of AI-generated fake reviews, human-generated fake reviews and authentic reviews. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 87, 104400.

- Abdalla, M. H. I., Malberg, S., Dementieva, D., Mosca, E., & Groh, G. (2023). A benchmark dataset to distinguish human-written and machine-generated scientific papers. Information, 14(10), 522.

- Holzmann, U., Anand, S., & Payumo, A. Y. (2025). The ChatGPT Fact-Check: exploiting the limitations of generative AI to develop evidence-based reasoning skills in college science courses. Advances in Physiology Education, 49(1), 191-196.

- Idan, D., Ben-Shitrit, I., Volevich, M., Binyamin, Y., Nassar, R., Nassar, M., ... & Einav, S. (2025). Evaluating the performance of large language models versus human researchers on real world complex medical queries. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 37824.

- Matalon, J., Spurzem, A., Ahsan, S., White, E., Kothari, R., & Varma, M. (2024). Reader’s digest version of scientific writing: comparative evaluation of summarization capacity between large language models and medical students in analyzing scientific writing in sleep medicine. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7, 1477535.

- Sadasivan, V. S., Kumar, A., Balasubramanian, S., Wang, W., & Feizi, S. (2025). Can AI-generated text be reliably detected? stress testing AI text detectors under various attacks. Transactions on Machine Learning Research.

- Lu, N., Liu, S., He, R., & Tang, K. (2024). Large language models can be guided to evade AI-generated text detection. Transactions on Machine Learning Research.

- Malik, M. A., & Amjad, A. I. (2025). AI vs AI: How effective are Turnitin, ZeroGPT, GPTZero, and Writer AI in detecting text generated by ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Gemini?. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 8(1), 91-101.

- Pratama, A. R. (2025). The accuracy-bias trade-offs in AI text detection tools and their impact on fairness in scholarly publication. PeerJ Computer Science, 11, e2953.

- Li, X., Ruan, F., Wang, H., Long, Q., & Su, W. J. (2025). A statistical framework of watermarks for large language models: Pivot, detection efficiency and optimal rules. The Annals of Statistics, 53(1), 322-351.

- Li, X., Liu, X., & Li, G. (2025). Adaptive Testing for Segmenting Watermarked Texts From Language Models. Stat, 14(4), e70118.

- Al Hosni, J. K. (2025). Preserving Authorial Voice in Academic Texts in the Age of Generative AI: A Thematic Literature Review. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume, 16.

- Pividori, M., & Greene, C. S. (2024). A publishing infrastructure for Artificial Intelligence (AI)-assisted academic authoring. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 31(9), 2103-2113.

- Hashemi, A., Shi, W., & Corriveau, J. P. (2024). AI-generated or AI touch-up? Identifying AI contribution in text data. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 1-12.

- Alam, M. S., Asmawi, A., Haque, M. H., Patwary, M. N., Ullah, M. M., & Fatema, S. (2024). Distinguishing between Student-Authored and ChatGPT-Generated Texts: A Preliminary Exploration of Human Evaluation Techniques. Iraqi Journal for Computer Science and Mathematics, 5(3), 40.

- Ali, E. H. F., Kottaparamban, M., Ahmed, F. E. Y., Usmani, S., Hamd, M. A. A., Ibrahim, M. A. E. S., & Hamed, S. O. E. (2025). Beyond the human pen: The role of artificial intelligence in literary creation. Humanities, 6(4).

- Lau, H. T., & Zubiaga, A. (2025). Understanding the effects of human-written paraphrases in LLM-generated text detection. Natural Language Processing Journal, 100151.

- Burrows, J. (2002). ‘Delta’: a measure of stylistic difference and a guide to likely authorship. Literary and linguistic computing, 17(3), 267-287.

- Stamatatos, E. (2009). A survey of modern authorship attribution methods. Journal of the American Society for information Science and Technology, 60(3), 538-556.

- Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse studies, 7(2), 173-192.

- Biber, D. (2006). Stance in spoken and written university registers. Journal of English for academic purposes, 5(2), 97-116.

- Ji, Z., Lee, N., Frieske, R., Yu, T., Su, D., Xu, Y., ... & Fung, P. (2023). Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM computing surveys, 55(12), 1-38.

- Asgari, E., Montaña-Brown, N., Dubois, M., Khalil, S., Balloch, J., Yeung, J. A., & Pimenta, D. (2025). A framework to assess clinical safety and hallucination rates of LLMs for medical text summarisation. npj Digital Medicine, 8(1), 274.

- Gehrmann, S., Strobelt, H., & Rush, A. M. (2019). Gltr: Statistical detection and visualization of generated text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.04043.

- Mitchell, E., Lee, Y., Khazatsky, A., Manning, C. D., & Finn, C. (2023). Detectgpt: Zero-shot machine-generated text detection using probability curvature. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 24950-24962). PMLR.

- Kirchenbauer, J., Geiping, J., Wen, Y., Katz, J., Miers, I., & Goldstein, T. (2023). A watermark for large language models. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 17061-17084). PMLR.

- Shportko, A., & Verbitsky, I. (2025). Paraphrasing Attack Resilience of Various Machine-Generated Text Detection Methods. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 4: Student Research Workshop) (pp. 474-484).

- Macko, D., Moro, R., Uchendu, A., Lucas, J., Yamashita, M., Pikuliak, M., ... & Bielikova, M. (2023, December). MULTITuDE: Large-scale multilingual machine-generated text detection benchmark. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 9960-9987).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).