Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vineyard, Experimental Design and Sampling

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis of Grapes

2.3. The Extraction and Analysis of Flavonoids in Grapes

2.4. The Extraction and Analysis of Volatiles in Grapes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Data

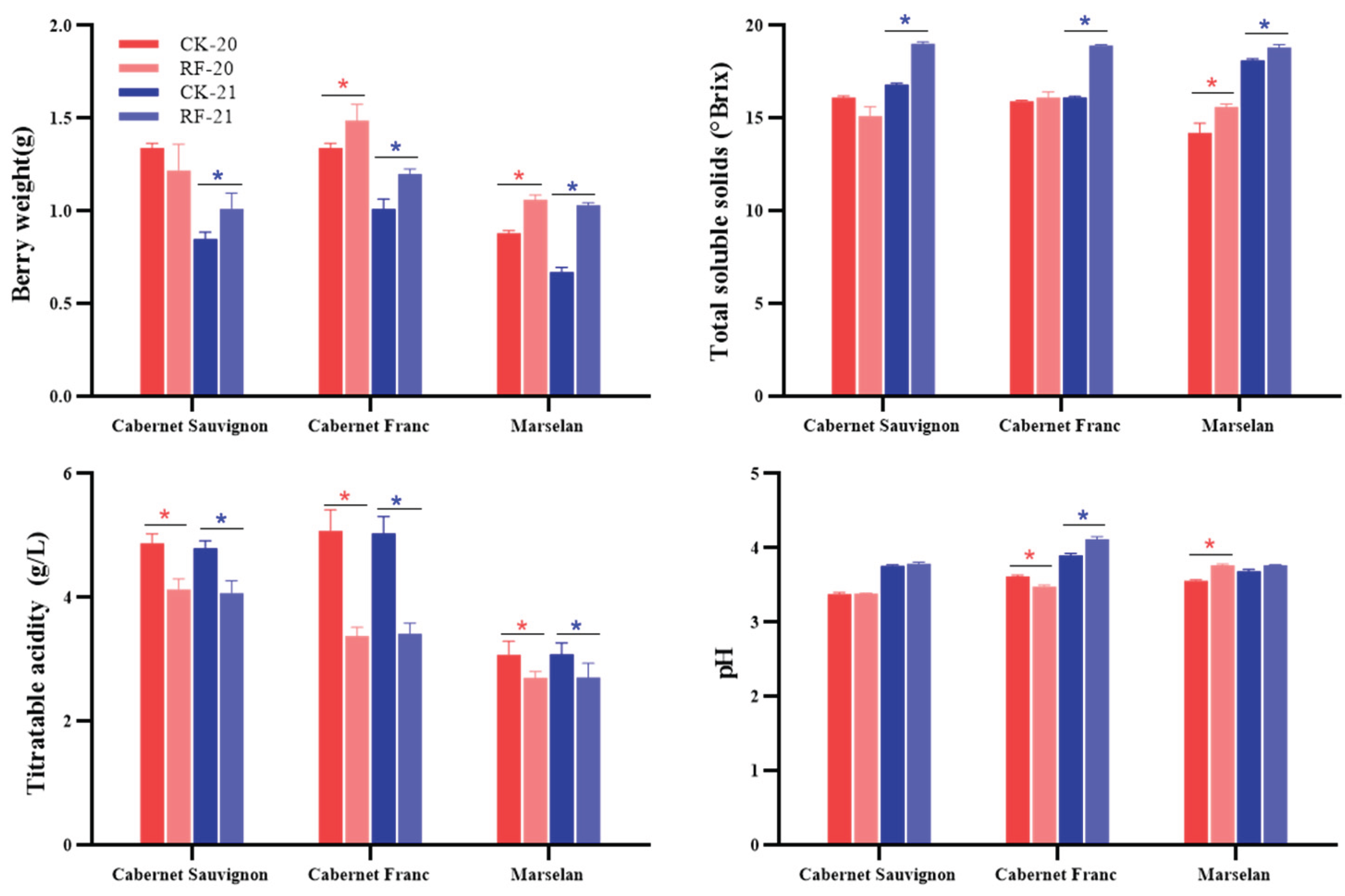

3.2. Physicochemical Indicators of Grape Berries

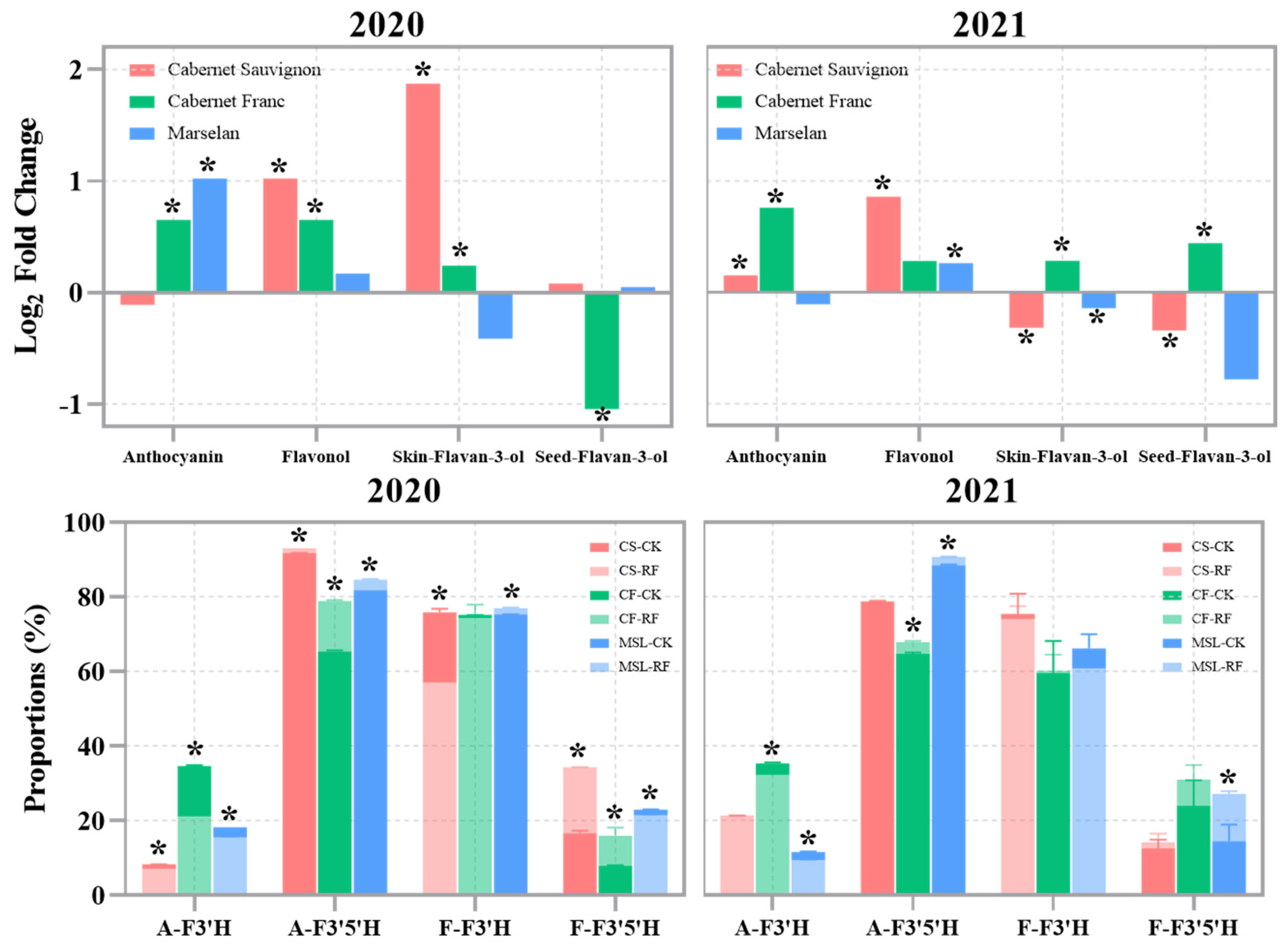

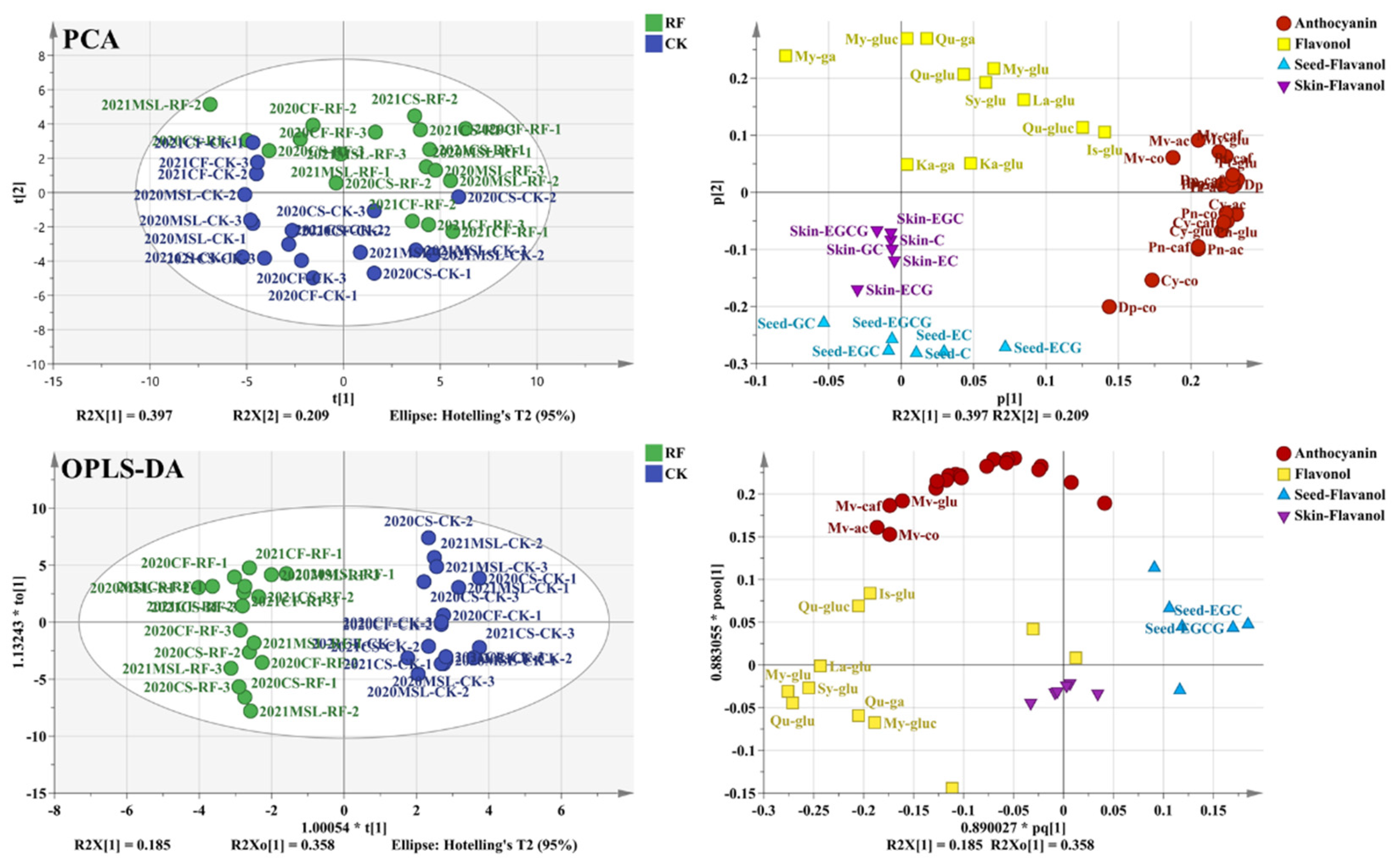

3.3. The Flavonoids of Grape Berries

3.4. Photosensitive Flavonoids of Grape Berries

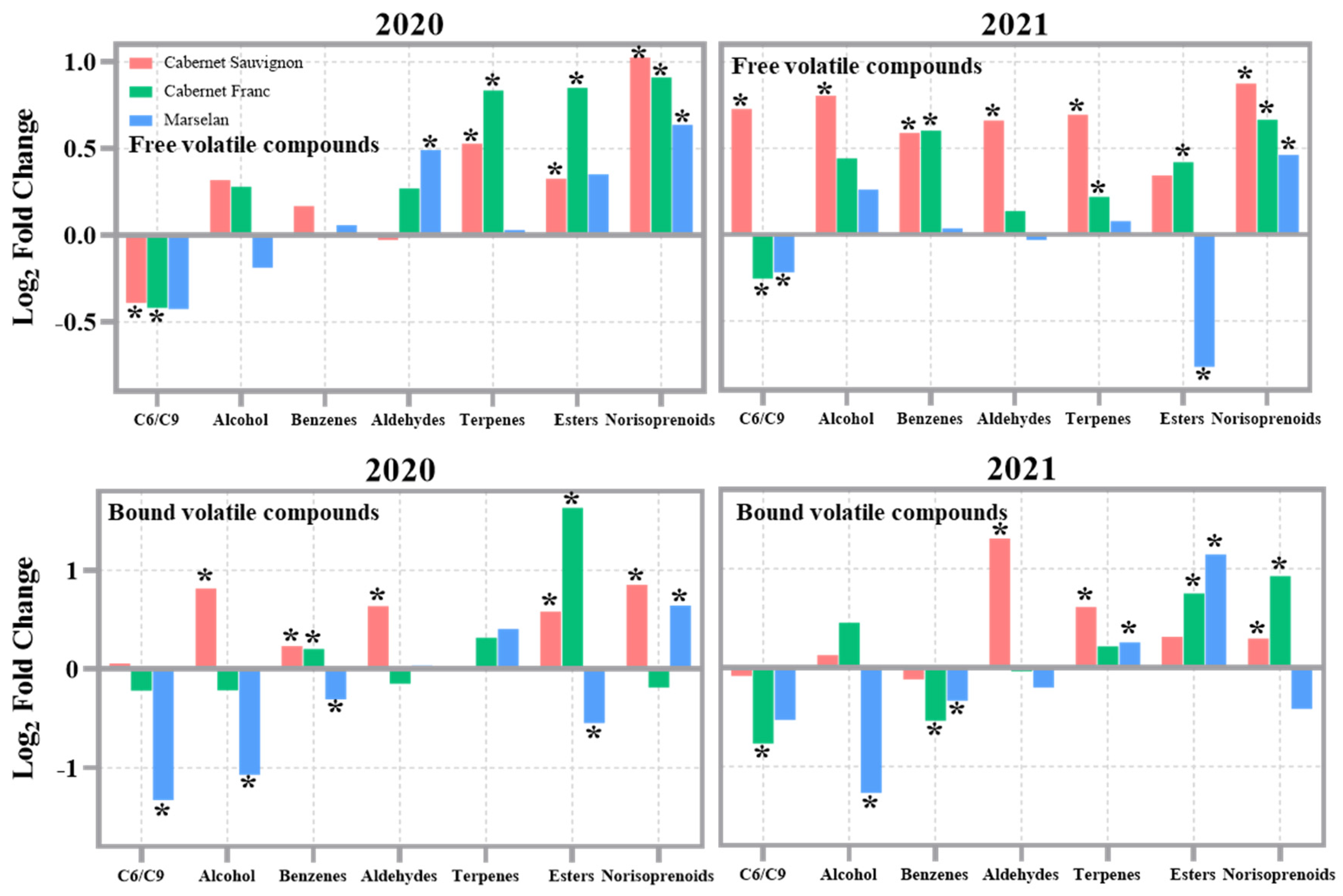

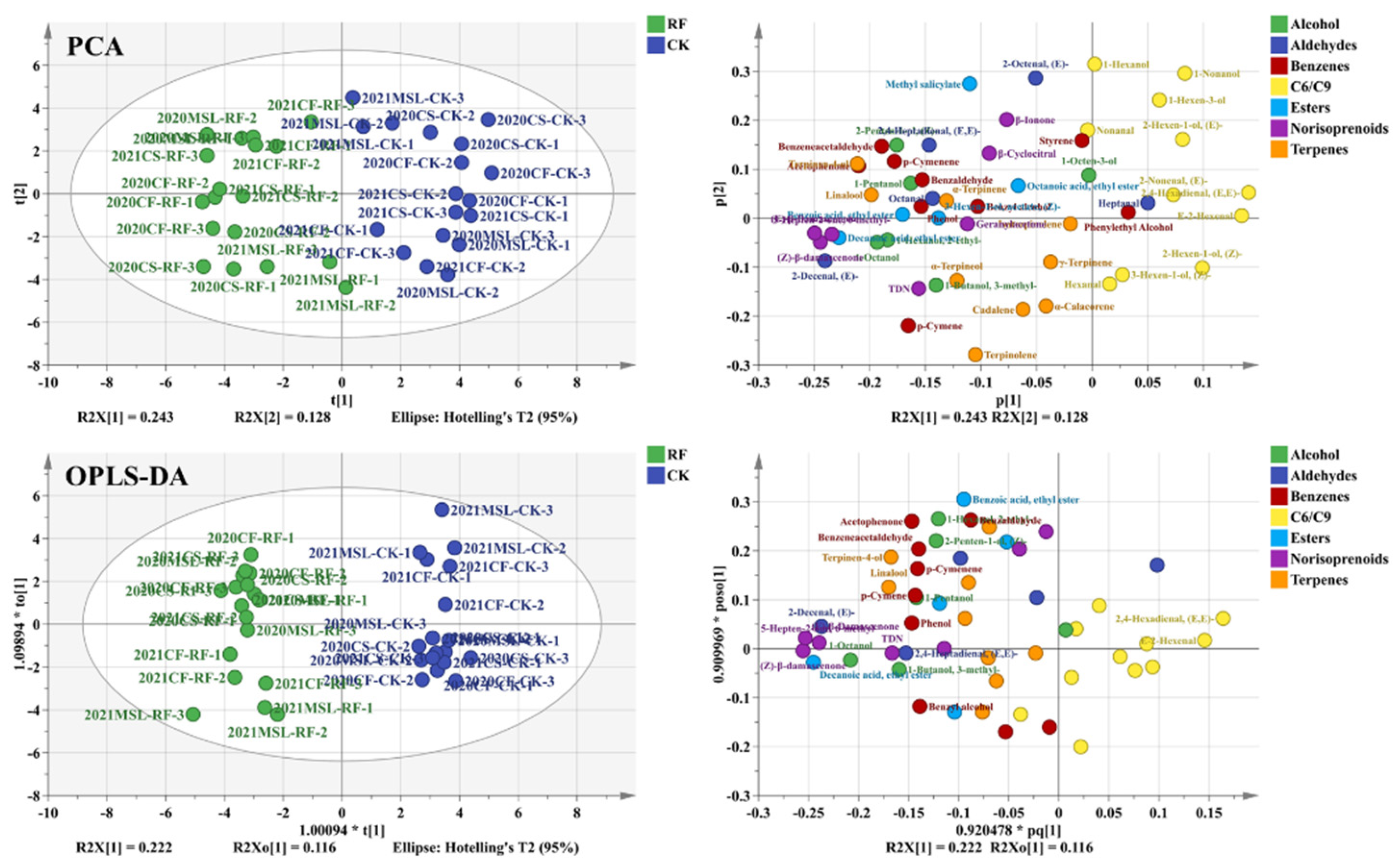

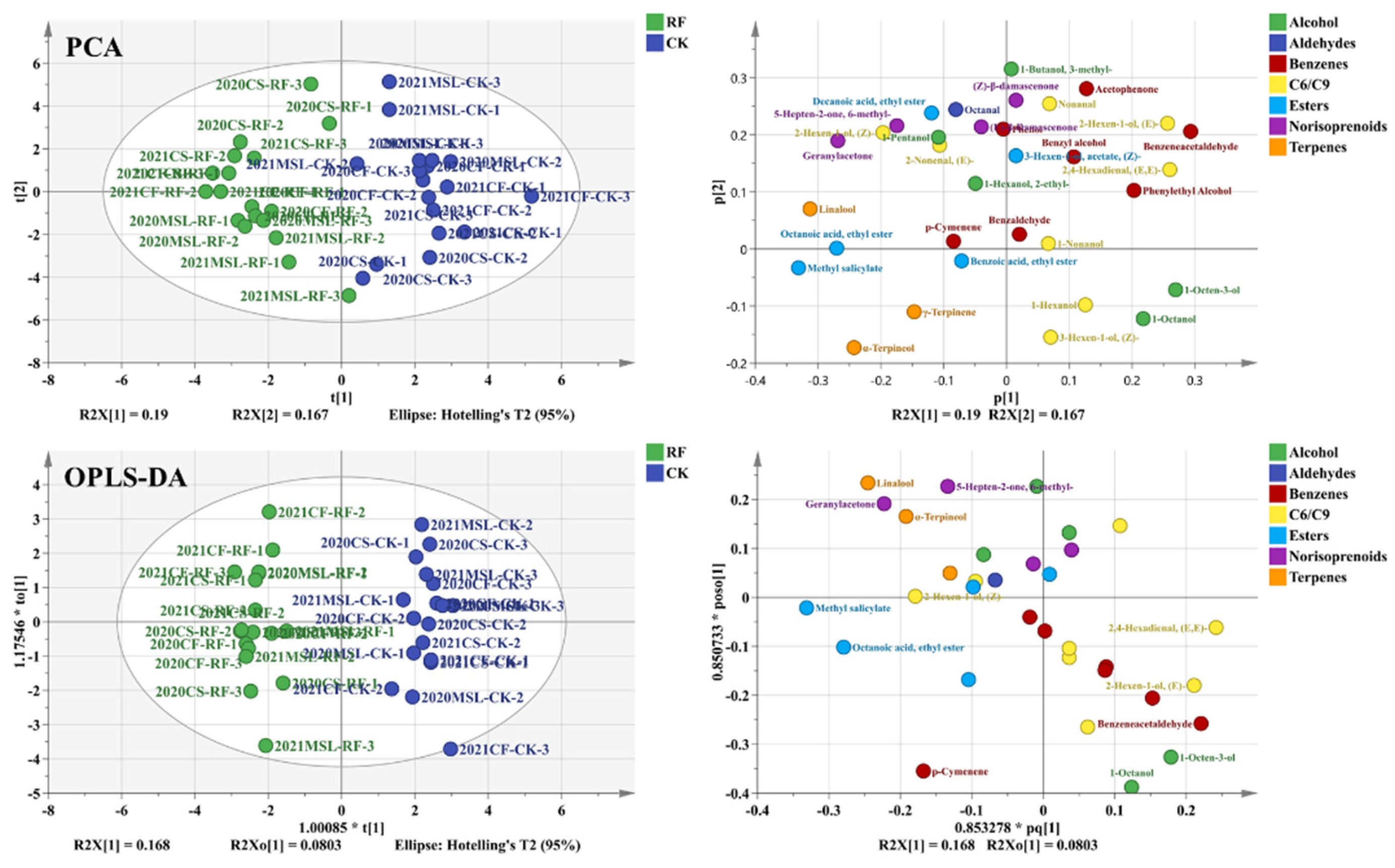

3.5. The Volatiles of Grape Berries

3.6. Photosensitive Volatiles of Grape Berries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, M.B.; Yuan, L.; Zheng, M.Y.; Xi, Z.M. Differences in anthocyanin accumulation profiles between teinturier and non-teinturier cultivars during ripening. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine polyphenol content and its influence on wine quality and properties: A review. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-C.; Tian, M.-B.; Shi, N.; Han, X.; Li, H.-Q.; Cheng, C.-F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.-D.; He, F.; Duan, C.-Q.; et al. Severe shoot topping slows down berry sugar accumulation rate, alters the vine growth and photosynthetic capacity, and influences the flavoromics of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes in a semi-arid region. European Journal of Agronomy 2023, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Wine aroma compounds in grapes: A critical review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2015, 55, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.B.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.C.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, C.F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.D.; He, F.; Duan, C.Q.; et al. Volatomics of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grapes and wines under the fan training system revealed the nexus of microclimate and volatile compounds. Food Chem 2023, 403, 134421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jin, G.J.; Wang, X.J.; Kong, C.L.; Liu, J.B.; Tao, Y.S. Chemical profiles and aroma contribution of terpene compounds in Meili (Vitis vinifera L.) grape and wine. Food Chemistry 2019, 284, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.X.; Zhang, M.M.; Xiang, X.F.; Lan, Y.B.; Shi, Y.; Duan, C.Q.; Zhang, R.L. Aromatic characterization of traditional Chinese wine Msalais by partial least-square regression analysis based on sensory quantitative descriptive and odor active values, aroma extract dilution analysis, and aroma recombination and omission tests. Food Chemistry 2021, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ul Hassan, M.N.; Zainal, Z.; Ismail, I. Green leaf volatiles: biosynthesis, biological functions and their applications in biotechnology. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2015, 13, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Xue, T.T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yao, F.; Wang, H.; Li, H. A sustainable viticulture method adapted to the cold climate zone in China. Horticulturae 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.Q.; Gao, X.T.; Lu, H.C.; Peng, W.T.; Chen, W.; Li, S.D.; Li, S.P.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J. Influence of attenuated reflected solar radiation from the vineyard floor on volatile compounds in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and wines of the north foot of Mt. Tianshan. Food Research International 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, H.A.; Brock, P.E.; Heuvel, J.E.V. Effects of three reflective mulches on yield and fruit composition of coastal new England winegrapes. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2009, 60, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, P.M. Effect of crushed glass, used as a reflective mulch, on Pinot noir performance. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.B.; Ma, W.H.; Xia, N.Y.; Peng, J.; Hu, R.Q.; Duan, C.Q.; He, F. Soil variables and reflected light revealed the plasticity of grape and wine composition: Regulation of the flavoromics under inner row gravel covering. Food Chem 2023, 414, 135659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xie, Y.M.; Li, B.; Wei, X.Y.; Huang, R.T.; Liu, S.Q.; Ma, L.L. To improve grape photosynthesis, yield and fruit quality by covering reflective film on the ground of a protected facility. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejar, K.J.; Vasconcelos, M.C.; King, P.D.; Smart, R.E.; Ball, K.; Field, S.K. Herbicide reduction through the use of weedmat undervine treatment and the lack of impact on the aromatic profile and volatile composition of Malbec wines. Food Chemistry 2021, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osrecak, M.; Karoglan, M.; Kozina, B. Influence of leaf removal and reflective mulch on phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of Merlot, Teran and Plavac mali wines (Vitis vinifera L.). Scientia Horticulturae 2016, 209, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Pearson, E.G.; Savigny, C.d.; Coventry, J.; Strommer, J. Interactions of vine age and reflective mulch upon berry, must, and wine composition of five Vitis vinifera cultivars. International Journal of Fruit Science 2008, 7, 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Lu, H.C.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.T.; Li, H.Q.; Tian, M.B.; Shi, N.; Li, M.Y.; Yang, X.L.; He, F.; et al. Region, vintage, and grape maturity co-shaped the ionomic signatures of the Cabernet Sauvignon wines. Food Research International 2023, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Pei, X.-X.; Li, M.-Y.; Chen, W.-T.; Li, H.-Q.; Yang, G.-S.; Duan, C.-Q.; Wang, J. Metabolomics of Vitis davidii Foëx. grapes from southern China: Flavonoids and volatiles reveal the flavor profiles of five spine grape varieties. Food Chemistry 2024, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.C.; Tian, M.B.; Han, X.; Shi, N.; Li, H.Q.; Cheng, C.F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.D.; He, F.; Duan, C.Q.; et al. Vineyard soil heterogeneity and harvest date affect volatolomics and sensory attributes of Cabernet Sauvignon wines on a meso-terroir scale. Food Res Int 2023, 174, 113508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.B.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.C.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, C.F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.D.; He, F.; Duan, C.Q.; et al. Cluster spatial positions varied the phenolics profiles of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grapes and wines under a fan training system with multiple trunks. Food Chem 2022, 387, 132930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.G.; Shin, M.H.; Cha, G.H.; Kim, H.L.; Ban, T.; Kumarihami, H.; Kim, S.H.; Jeong, G.; et al. Reflective plastic film mulches enhance light intensity, floral induction, and bioactive compounds in ‘O’Neal’ southern highbush blueberry. Scientia Horticulturae 2019, 246, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Fang, L. Effects of different mulching practices on the photosynthetic characteristics of hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) in a greenhouse in Northwest China. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B-Soil and Plant Science 2015, 65, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Jiménez, L.; Zermeño-González, A.; Munguía-López, J.; Quezada-Martín, M.A.R.; De La Rosa-Ibarra, M. Photosynthesis, soil temperature and yield of cucumber as affected by colored plastic mulch. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B-Soil and Plant Science 2008, 58, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Mills, L.J.; Wample, R.L.; Spayd, S.E. Cluster thinning effects on three deficit-irrigated Vitis vinifera cultivars. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2005, 56, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.W.; Ollat, N.; Gomès, E.; Decroocq, S.; Tandonnet, J.P.; Bordenave, L.; Pieri, P.; Hilbert, G.; Kappel, C.; van Leeuwen, C.; et al. Ecophysiological, genetic, and molecular causes of variation in grape berry weight and composition: A review. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2011, 62, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBolt, S.; Ristic, R.; Iland, P.G.; Ford, C.M. Altered light interception reduces grape berry weight and modulates organic acid biosynthesis during development. Hortscience 2008, 43, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Li, H.-Q.; Lu, H.-C.; Tian, M.-B.; Han, X.; He, F.; Wang, J. Adjusting the pomace ratio during red wine fermentation: Effects of adding white grape pomace and juice runoff on wine flavoromics and sensory qualities. Food Chemistry: X 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; Nelson, C.J.; Gambetta, G.; Kennedy, J.A.; Kurtural, S.K. Anthocyanin composition of merlot is ameliorated by light microclimate and irrigation in Central California. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2015, 66, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Yakushiji, H.; Koshita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes in grape skin are differentially regulated by temperature and light conditions. Planta 2012, 236, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Lüscher, J.; Brillante, L.; Kurtural, S.K. Flavonol profile is a reliable indicator to assess canopy architecture and the exposure of red wine grapes to solar radiation. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, M.O.; Harvey, J.S.; Robinson, S.P. The effect of bunch shading on berry development and flavonoid accumulation in Shiraz grapes. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2004, 10, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Lu, H.; Tian, M.; He, F.; Wang, J. Modifications of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Petit Verdot grape flavonoids as affected by the different rootstocks in eastern China. Technology in Horticulture 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Wei, K.; Jiang, Y.W.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, J.; He, W.; Zhang, C.C. Seasonal climate effects on flavanols and purine alkaloids of tea (Camellia sinensis L.). European Food Research and Technology 2011, 233, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, C.; Ravaglia, D.; Costa, G. Effects of fruit load and reflective mulch on phenolic compounds accumulation in nectarine fruit. European Journal of Horticultural Science 2010, 75, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, G.L.; Merwin, I.A.; Brown, M.G.; Padilla-Zakour, O. Influence of geotextile mulches on canopy microclimate, yield, and fruit composition of Cabernet Franc. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2007, 58, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Matthews, M.A.; Di Gaspero, G.; Gambetta, G.A. Water deficits accelerate ripening and induce changes in gene expression regulating flavonoid biosynthesis in grape berries. Planta 2007, 227, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.T.; Li, H.Q.; Wang, Y.; Peng, W.T.; Chen, W.; Cai, X.D.; Li, S.D.; He, F.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J. Influence of the harvest date on berry compositions and wine profiles of Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ under a semiarid continental climate over two consecutive years. Food Chemistry 2019, 292, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.N.; He, L.; He, F.; Chen, W.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J. Changes in global aroma profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon in response to cluster thinning. Food Res Int 2019, 122, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedel, M.; Frotscher, J.; Nitsch, M.; Hofmann, M.; Bogs, J.; Stoll, M.; Dietrich, H. Light promotes expression of monoterpene and flavonol metabolic genes and enhances flavour of winegrape berries (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Riesling). Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2016, 22, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Q.; Smart, R.; Wang, H.; Dambergs, B.; Sparrow, A.; Qian, M.C. Effect of grape bunch sunlight exposure and UV radiation on phenolics and volatile composition of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot noir wine. Food Chemistry 2015, 173, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Takase, H.; Matsuyama, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Matsuo, H.; Ikoma, G.; Takata, R. Effect of light exposure on linalool biosynthesis and accumulation in grape berries. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry 2016, 80, 2376–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Pinto, M.M. Carotenoid breakdown products the-norisoprenoids-in wine aroma. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2009, 483, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Seo, M.J.; Riu, M.; Cotta, J.P.; Block, D.E.; Dokoozlian, N.K.; Ebeler, S.E. Vine microclimate and norisoprenoid concentration in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2007, 58, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.R.; Eyeghe-Bickong, H.A.; du Plessis, K.; Alexandersson, E.; Jacobson, D.A.; Coetzee, Z.; Deloire, A.; Vivier, M.A. Grapevine plasticity in response to an altered microclimate: Sauvignon Blanc modulates specific metabolites in response to increased berry exposure. Plant Physiology 2016, 170, 1235–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, C.; Young, P.R.; Eyéghé-Bickong, H.A.; Vivier, M.A. Field-grown grapevine berries use carotenoids and the associated xanthophyll cycles to acclimate to uv exposure differentially in high and low light (shade) conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year/Month | T-Mean (°C) | T-Max (°C) | T-Min (°C) | RH (%) | PRCP (mm) |

| 2020 | |||||

| May | 21.1 | 27.0 | 15.5 | 53.1 | 49.3 |

| June | 26.9 | 32.7 | 21.2 | 49.8 | 33.7 |

| July | 26.7 | 31.5 | 22.2 | 66.5 | 108.5 |

| August | 26.7 | 31.2 | 22.5 | 72.0 | 167.4 |

| September | 21.8 | 27.2 | 17.0 | 62.5 | 71.1 |

| 2021 | |||||

| May | 20.6 | 26.6 | 14.0 | 43.0 | 16.3 |

| June | 25.7 | 31.4 | 19.7 | 54.0 | 36.5 |

| July | 26.7 | 31.0 | 23.3 | 78.2 | 238.9 |

| August | 25.7 | 30.3 | 21.5 | 70.4 | 141.5 |

| September | 21.9 | 26.4 | 18.4 | 78.1 | 139.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).