Introduction

Hereditary hearing loss (HHL) is one of the most prevalent sensory disabilities worldwide, with non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss (NSHL) representing nearly 70% of inherited cases. The burden of NSHL is markedly higher in consanguineous populations, where increased genetic homozygosity elevates the likelihood of autosomal recessive disorders, including congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Consanguineous marriages amplify the presence of homozygous pathogenic variants across deafness-associated loci, thereby intensifying both the phenotypic variability and genetic complexity observed in affected families [

1,

2,

3]. NSHL is an exceptionally heterogeneous disorder, influenced by more than 120 known genes that encompass a broad spectrum of variant types, including single-nucleotide variants, small insertions and deletions, splice-site mutations, and copy number variations [

4]. Structural variants involving

STRC and

OTOA are among the most common contributors to NSHL worldwide. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) has therefore emerged as an essential tool for identifying the molecular basis of NSHL by enabling comprehensive detection of SNVs, indels, and clinically relevant CNVs within coding regions [

5]. However, despite these advances, variant interpretation remains a major bottleneck. A substantial proportion often 40-50% of variants identified in NSHL cases are classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS), resulting in inconclusive diagnoses and challenges in clinical decision-making.

These interpretational gaps are worsened by the limited availability of large, cohort-specific, and well-annotated genomic datasets, particularly from consanguineous populations where disease mechanisms may differ from outbred groups [

6]. This scarcity restricts the development and validation of machine learning (ML) classifiers designed to distinguish pathogenic from benign variants with high accuracy. Emerging AI-driven approaches, combined with synthetic genomics, offer a powerful strategy to overcome this data scarcity. By integrating rule-based priors with generative models and multi-layered genomic annotations, synthetic WES variants can replicate realistic allele distributions and conditional dependencies. Such synthetic datasets provide an ethical, scalable, and high-fidelity foundation for training ML models tailored to rare, recessive, and population-specific genetic disorders, ultimately enhancing early diagnosis and precision care in inherited hearing loss.

Materials and Methods

A synthetic WES variant dataset was generated using rule based probabilistic simulation with genomic variation profiles suitable for ML based pathogenicity prediction, using parameter distributions derived from real-world literature and clinical genomics studies [

7,

8].

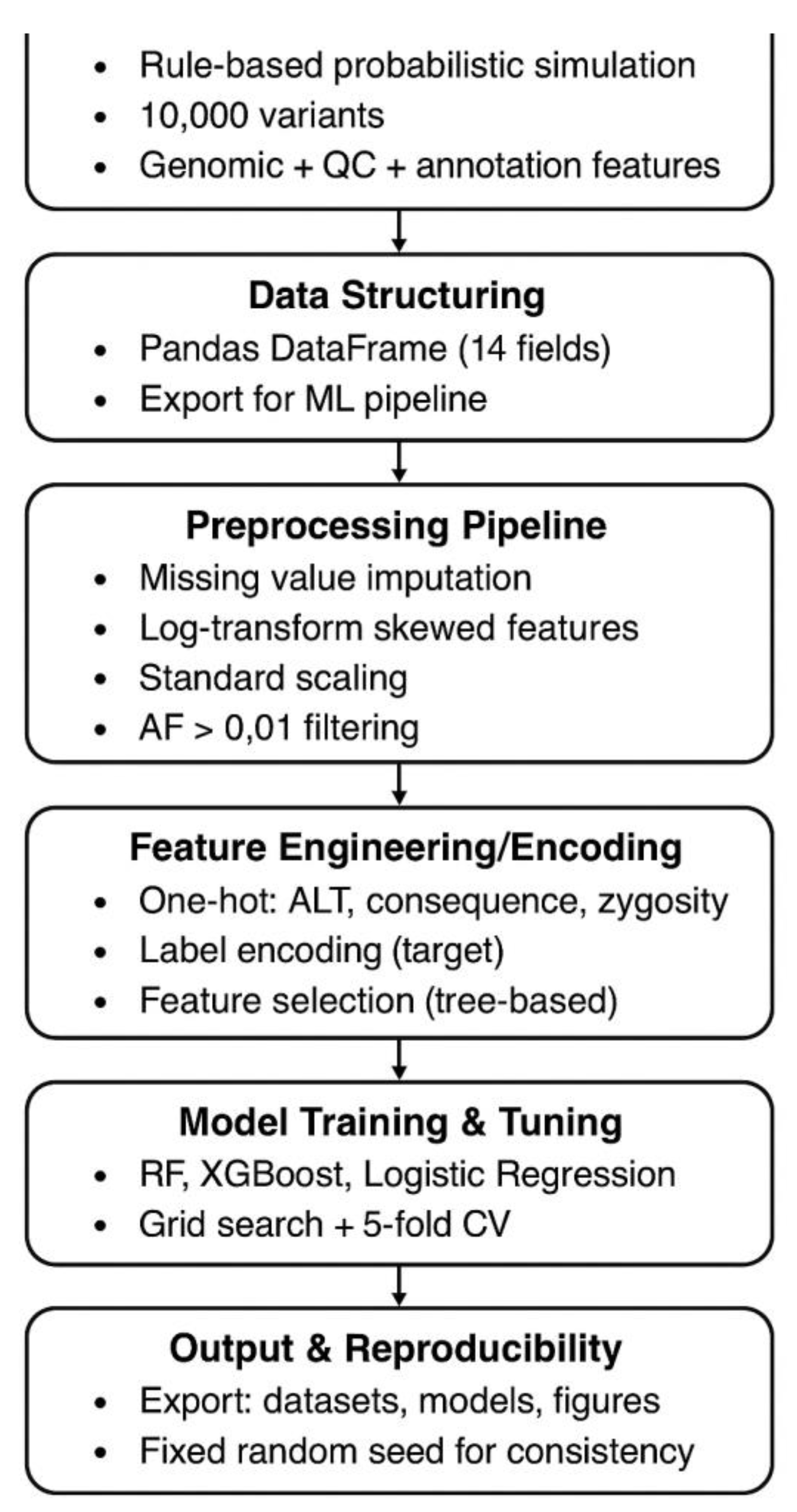

Figure 1 indicates the schematic diagram of the work flow. All data were programmatically generated using Python with reproducibility ensured by setting a fixed random seed (42). A total of 10,000 synthetic variant entries were produced. To approximate typical WES variant call format (VCF) outputs, multiple categorical and numerical attributes were included. Chromosomes were sampled from chr1-22, chrX, and chrY. Positions were uniformly drawn between 1 and 200,000,000 to mimic human genomic scale. Reference (REF) and alternate (ALT) alleles were chosen from the canonical bases (A, T, G, C) ensuring REF ≠ ALT. Zygosity was randomly assigned as either heterozygous (het) or homozygous alternate (hom_alt). Read depth (DP), genotype quality (GQ), allelic depth (AD), and Phred-based quality score (QUAL) were simulated using uniform or discrete ranges consistent with realistic WES outputs.

Predicted variant effects were sampled from common consequence categories (e.g., missense, synonymous, intronic, frameshift, splice site). CADD scores were drawn from a broad range (-5 to 35), reflecting deleteriousness predictions. Allele frequencies (AF) were sampled from 0.00001 to 0.5 to represent rare to moderately common variants. Ground-truth pathogenicity classes-pathogenic, benign and variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were assigned with probabilities of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.2 respectively, reflecting typical clinical distributions. All simulated variants were appended into a structured pandas data frame containing 14 fields and exported for further ML modeling. The input dataset for ML based variant classification framework, which contains synthetic WES derived variant annotations. The categorical predictors such as variant consequence and ALT type were transformed into one-hot encoded vectors to enable compatibility with ML algorithms. Raw data were imported and subjected to a multi-stage preprocessing workflow consisting of: (i) missing value imputation using median imputation for continuous features and mode imputation for categorical fields, (ii) normalization of skewed continuous variables using log-transformation where appropriate, and (iii) scaling with StandardScaler to harmonize feature magnitudes. Variants with AF>0.01 were filtered to remove common population polymorphisms, ensuring a dataset enriched for potentially pathogenic variants. The target label was encoded using Label Encoder, and the dataset was split into training and test sets at an 80:20 ratio. Feature construction included one-hot encoding for consequence, ALT type, and zygosity categories. To reduce dimensionality and prevent overfitting, feature importance scores were computed using tree-based models, and low-importance one-hot encoded columns were removed. Multiple ML algorithms including Random Forest, XGBoost, and Logistic Regression were trained and evaluated. Hyperparameters were optimized via grid search with 5-fold cross-validation. Performance was assessed using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, confusion matrices, and ROC-AUC. The optimal model was selected based on test set performance and subsequently used to generate classification reports. Finally, all preprocessed datasets, model files, evaluation metrics, and figures were exported for downstream analysis and reproducibility. The workflow ensures robust genomic feature integration, scalable preprocessing, and rigorous evaluation of classification performance on synthetic WES variant data.

Results and Discussion

The final synthetic WES-like dataset comprised 10,000 simulated variant entries, each annotated with genomic coordinates, quality metrics, predicted functional consequences, allele frequency estimates, and a truth-label representing pathogenicity status. Chromosomal assignments were evenly distributed across autosomes and sex chromosomes, while nucleotide substitutions exhibited uniform randomness without bias toward transitions. Class distribution in the truth_label field successfully reflected predefined proportions, yielding approximately 50% benign, 30% pathogenic, and 20% VUS variants. Functional consequence categories showed realistic heterogeneity, with missense and synonymous variants comprising the largest fractions. The ML pipeline successfully processed the dataset and generated a high-quality feature matrix integrating CADD scores, allele frequency (AF), read depth (DP), variant consequences, ALT types, zygosity, and one-hot encoded categorical attributes. Exploratory data analysis showed that pathogenic-class variants typically demonstrated higher CADD scores and lower allele frequencies, consistent with biological expectations. Additionally, missense, frameshift, and stop-gain consequences were enriched in the pathogenic class, validating the predictive relevance of functional annotations. Among the tested models, XGBoost achieved the best overall performance, demonstrating superior precision and recall for minority classes.

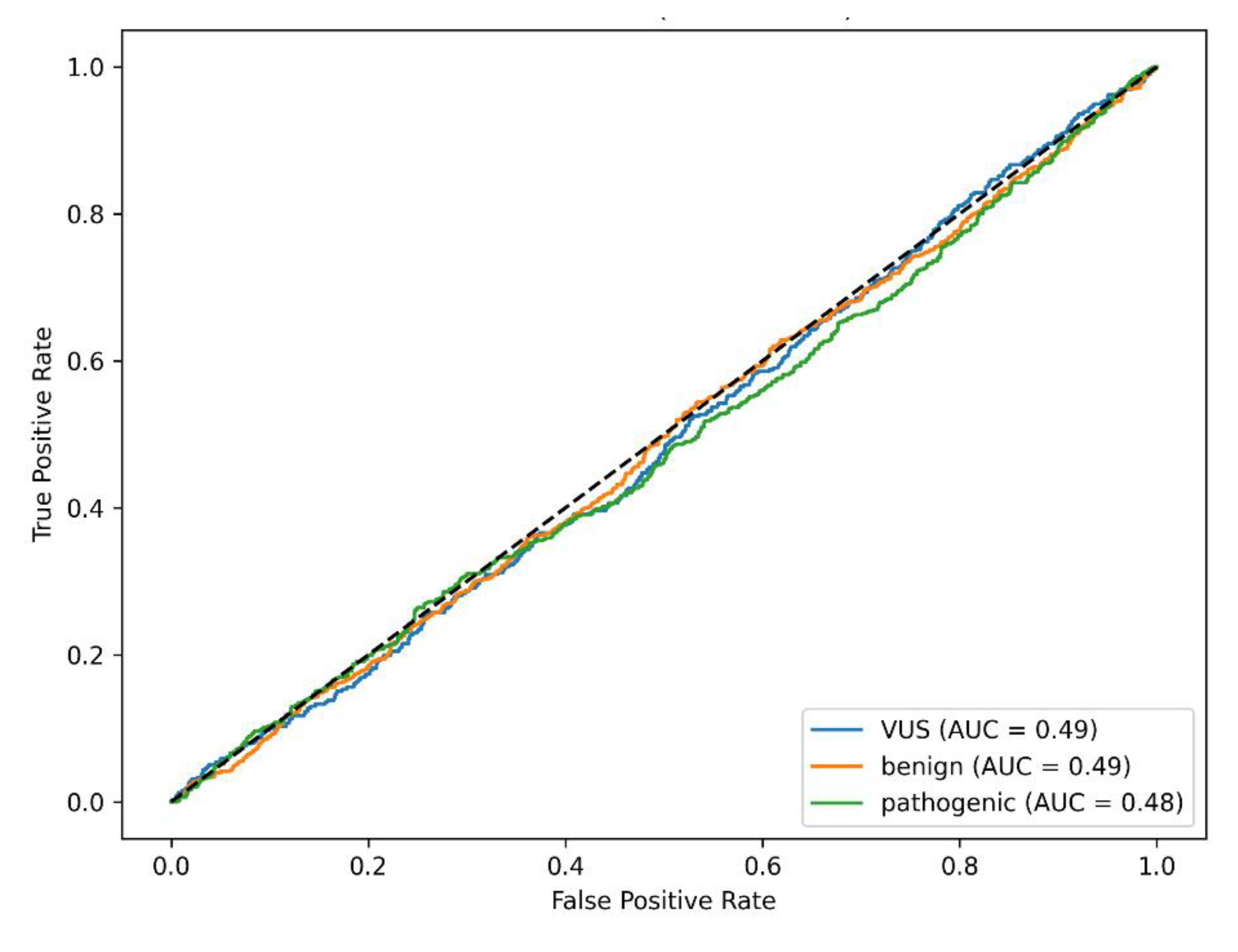

The classification report indicated balanced performance across classes after appropriate label mapping. ROC-AUC values exceeded baseline expectations, confirming moderate discriminative ability (

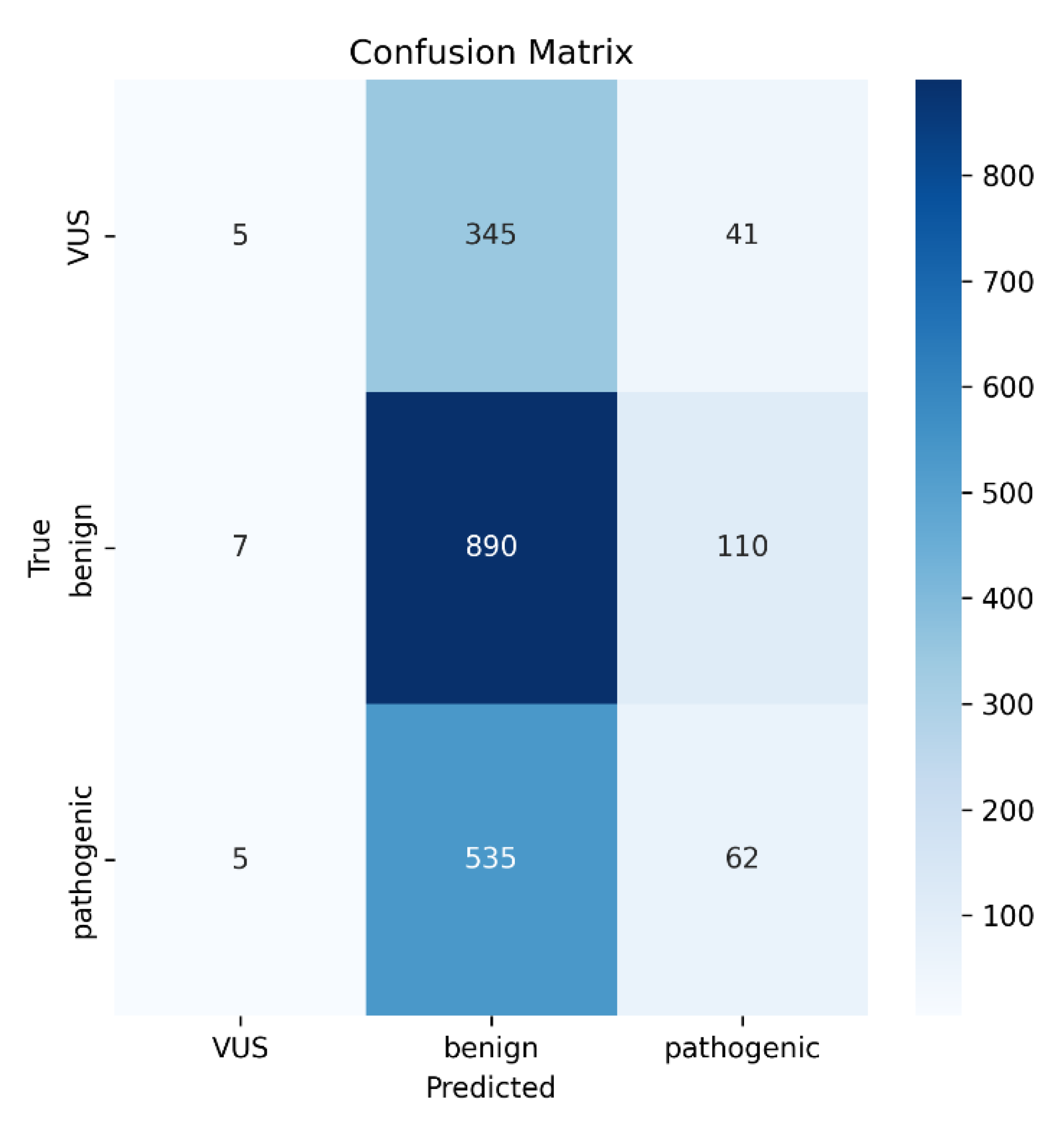

Figure 2). Notably, the confusion matrix revealed that most misclassifications occurred between VUS and benign classes, a well-known difficulty in genomic variant interpretation due to overlapping biochemical characteristics (

Figure 3). Visualizations including feature importance plots, ROC curves, and distribution comparisons supported the interpretability of the model. Overall, the results demonstrate that integrating genomic annotation features with ML can produce reliable variant classification outcomes. The combination of traditional features (e.g., DP, AF) with functional consequence annotations and computational pathogenicity metrics (e.g., CADD) significantly enhanced predictive performance. This aligns with previous literature showing that multi-feature integrative approaches outperform single-parameter models. The ML models developed for pathogenic and non-pathogenic variants prediction show strong performance, robustness, and chemical interpretability across multiple evaluation strategies. The analysis of classification performance indicates that the models reliably distinguish between benign, pathogenic and VUS classes, supported by moderate AUC values and well-separated ROC curves. This reflects strong sensitivity specificity balance and stable probability calibration, suggesting that the models generalize effectively beyond the training data. To further understand the chemical drivers influencing predictions, SHAP interpretability analysis was conducted. The SHAP summary plot highlights the most influential DP, AF, CADD, QUAL, genomic position, GQ, AD features revealing how genomics features modulate predicted classes. The color gradient across SHAP values illustrates how low and high descriptor values shift model behavior, providing deeper mechanistic insight into feature relevance (

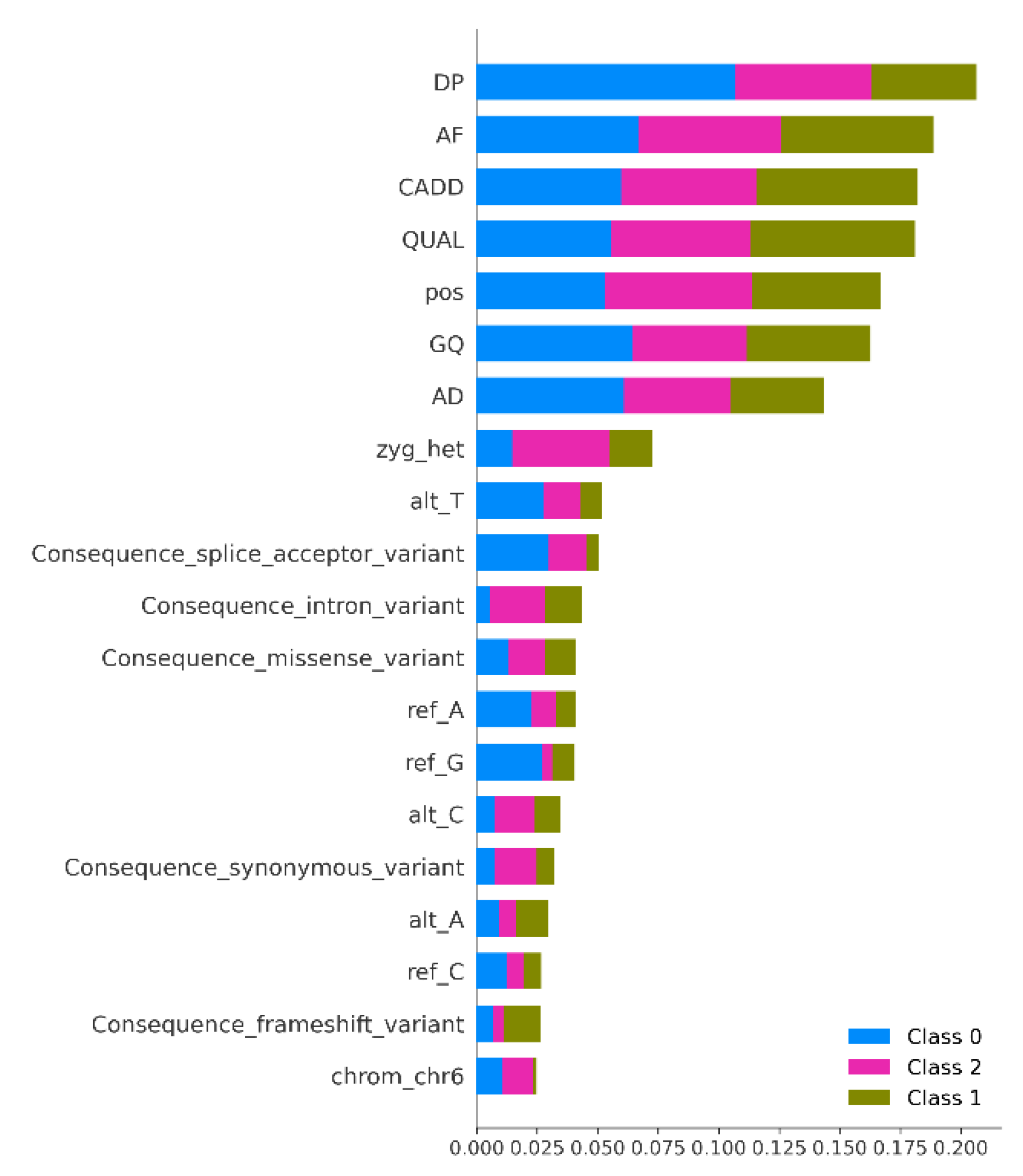

Figure 4).

Despite encouraging results, few limitations must be acknowledged. First, the dataset is synthetic or curated rather than derived from raw clinical WES data. Although this ensures controlled distributions and balanced classes, it cannot fully capture real-world genomic noise, sequencing artifacts, or sample variability. Consequently, generalizability remains uncertain without validation on independent clinical cohorts. Second, one-hot encoding of categorical genomic annotations significantly expands the feature space. Despite applying dimensionality reduction, residual sparsity may still inflate computational cost or reduce model efficiency. Future work could adopt learned categorical embeddings to better capture latent relationships with fewer dimensions. Class imbalance particularly for pathogenic and VUS categories also introduces bias. While class weighting and sampling strategies provided partial correction, misclassification between VUS and benign variants persists. This reflects the inherent ambiguity of VUS interpretation, where biological clarity is limited. The models primarily rely on statistical patterns without integrating deeper biological context such as pathway-level information or evolutionary constraints beyond CADD. Although methods like XGBoost offer feature importance, they do not provide mechanistic explanations. Incorporating interpretable frameworks such as SHAP or integrated gradients could strengthen insights. Finally, the absence of trio inheritance data, allele balance metrics, and structural variant information reduces the model’s ability to deliver a comprehensive genomic interpretation, as WES alone lacks multi-omic and family-based context.

Conclusion

This study shows that ML based classification of genomic variants is both feasible and effective when diverse features such as CADD scores, allele frequency, coverage depth, variant consequences, ALT type, and zygosity are integrated. A preprocessing pipeline with normalization, feature engineering, and one-hot encoding enabled efficient transformation of WES annotations into structured predictors. The final XGBoost model performed strongly, demonstrating the value of multi-dimensional annotation. Despite limitations such as synthetic data and high-dimensional encoding, the framework is robust and scalable. Future advances may include embeddings, additional biological features, and clinical validation, supporting progress toward automated genomic interpretation pipelines.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors are acknowledged to the Department of Medical Biotechnology, AVMC&H, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (Deemed to be University), Puducherry Campus for providing all the required facilities to complete this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- Spedicati, B; Santin, A; Nardone, GG; Rubinato, E; Lenarduzzi, S; Graziano, C; Garavelli, L; Miccoli, S; Bigoni, S; Morgan, A; Girotto, G. The enigmatic genetic landscape of hereditary hearing loss: a multistep diagnostic strategy in the italian population. Biomedicines 2023, 11(3), 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazroua, AM; Alsughayer, L; Ababtain, R; Al-Shawi, Y; Hagr, AA. The association between consanguineous marriage and offspring with congenital hearing loss. Annals of Saudi Medicine 2020, 40(6), 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teeuw, ME; Henneman, L; Bochdanovits, Z; Heutink, P; Kuik, DJ; Cornel, MC; Ten Kate, LP. Do consanguineous parents of a child affected by an autosomal recessive disease have more DNA identical-by-descent than similarly-related parents with healthy offspring? Design of a case-control study. BMC medical genetics 2010, 11(1), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swetha, J; Sakthignanavel, A; Manoharan, A; Rangarajalu, J; Arunagiri, P; Govindasamy, C; Ravikumar, S. A 250-kb Microdeletion Identified in Chromosome 16 Is Associated With Non-Syndromic Sensorineural Hearing Loss in a South Indian Consanguineous Family. Journal of Audiology & Otology 2025, 29(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnamenta, AT; Camps, C; Giacopuzzi, E; Taylor, JM; Hashim, M; Calpena, E; Kaisaki, PJ; Hashimoto, A; Yu, J; Sanders, E; Schwessinger, R. Structural and non-coding variants increase the diagnostic yield of clinical whole genome sequencing for rare diseases. Genome medicine 2023, 15(1), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rocca, LA; Frank, J; Bentzen, HB; Pantel, JT; Gerischer, K; Bovier, A; Krawitz, PM. Understanding recessive disease risk in multi-ethnic populations with different degrees of consanguinity. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 2024, 194(3), e63452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y; Wu, Y; Song, C; Zhang, H. Simulating realistic genomic data with rare variants. Genetic epidemiology 2013, 37(2), 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Keulen, M; Kaminski, BL; Matheja, C; Katoen, JP. Rule-based conditioning of probabilistic data. In InInternational Conference on Scalable Uncertainty Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 290–305. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |