Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.1.1. Study Design

2.1.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Echocardiography

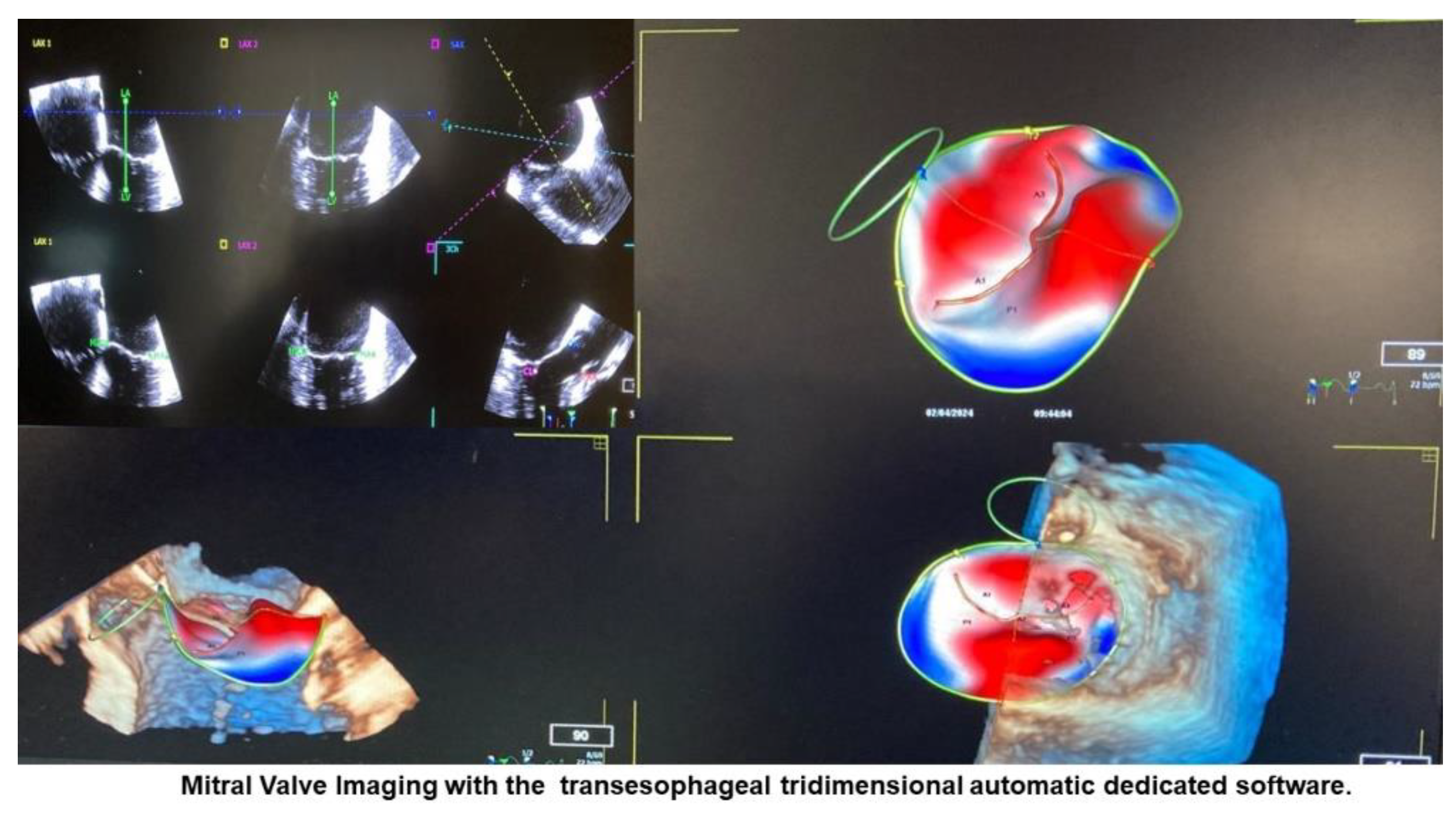

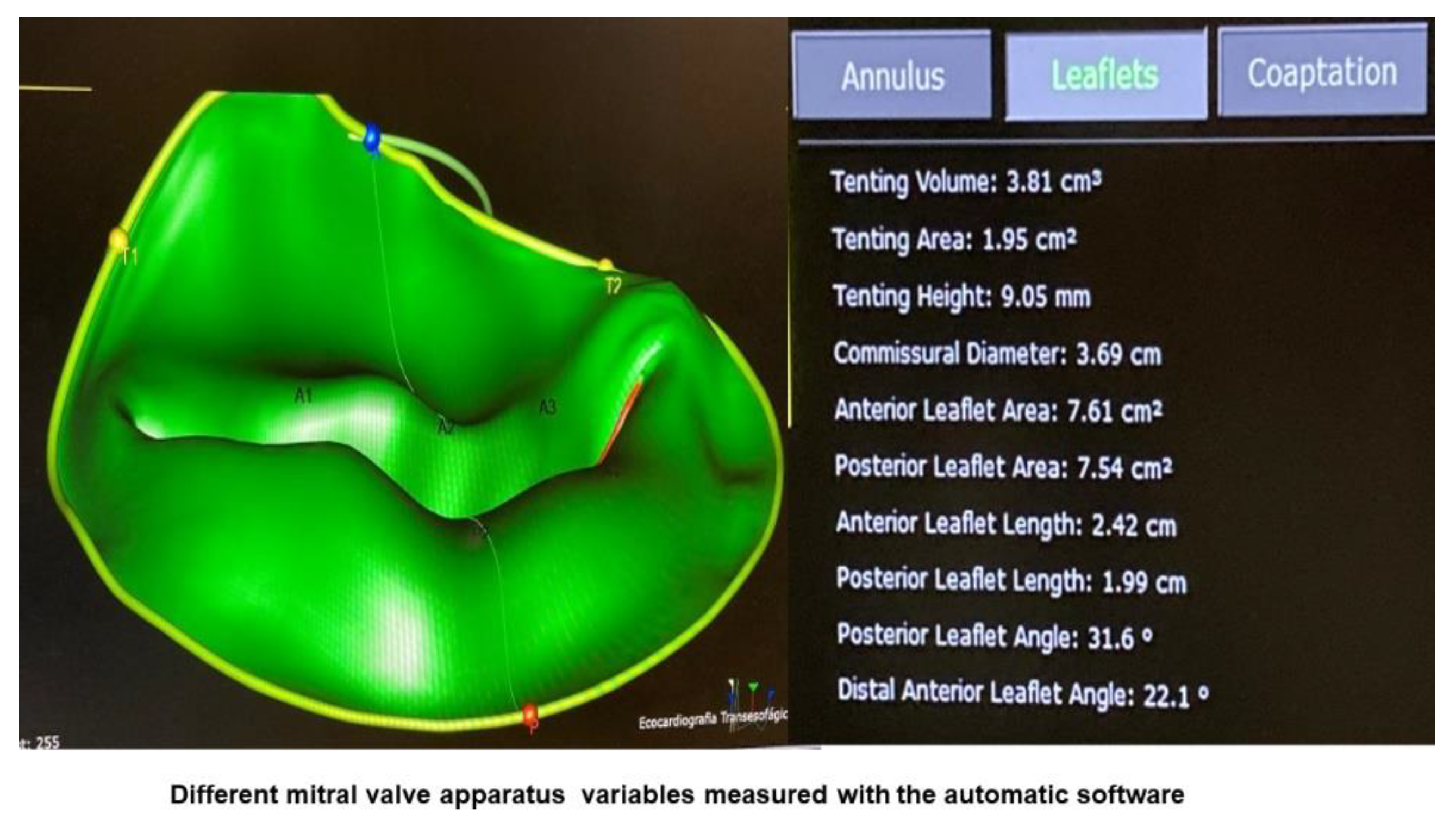

Imaging Acquisition

2.3. Imaging Analysis

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agricola E . Francesco A. Bartel T. Brochet E. Marc D. Faletra F. et al Multimodality imaging for patient selection. procedural guidance. and follow-up of transcatheter interventions for structural heart disease: a consensus document of the EACVI Task Force on Interventional Cardiovascular Imaging: part 1: access routes. transcatheter aortic valve implantation. and transcatheter mitral valve interventions. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023;24 (9): e209–e268.

- Faletra F. et al. The structural heart disease interventional imager rationale. skills and training: a position paper of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(5):471-479. [CrossRef]

- Vahanian A. Beyersdorf F. Praz F. Milojevic M. Baldus S. Bauersachs J. et al. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2022;43(7):561-632.

- Nishimura RA. Vahanian A. Eleid MF. Mack MJ. Mitral valve disease— current management and future challenges. Lancet. 2016;387:1324–1334.

- Gammie JS. O’Brien SM. Griffith BP. Ferguson TB. Peterson ED. Influence of hospital procedural volume on care process and mortality for patients undergoing elective surgery for mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2007;115:881–887.

- Calleja A, Poulin F, Woo A, et al. Quantitative modeling of the mitral valve by three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing mitral valve repair: correlation with intraoperative surgical technique. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1083–92. [CrossRef]

- Melamed T Badiani . Harlow S. Laskar N. Treibel T. Aung N. et al. Prevalence. progression. and clinical outcomes of mitral valve prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2025 ;11(5):631-641.

- Berthelot-Richer M, Vakulenko H V, Calleja A, Woo A, Paaladinesh Thavendiranathan P, Poulin F. Two-dimensional transthoracic measure of mitral annulus in mitral valve prolapse and moderate to severe regurgitation: a method comparison analysis with three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography. J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Jun 12;32(1):2.

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:e57-185.

- Clavel MA, Mantovani F, Malouf J, et al. Dynamic phenotypes of degenerative myxomatous mitral valve disease: quantitative 3-dimensional echocardiographic study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e002989.

- Pardi MM, Pomerantzef PMA, Sampaio RO, Abduch MA, Brandão CMA, Mathias Jr W, et al. Relation of mitral valve morphology to surgical repair results in patients with mitral valve prolapse: A three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography study. Echocardiography . 2018;35(9):1342-1350.

- Guedes MA, Pomerantzeff PM, Brandão CM, Vieira ML, Tarasoutchi F, et al. Mitral annulus morphologic and functional analysis using real time tridimensional echocardiography in patients submitted to unsupported mitral valve repair. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2015 ;30(3):325-34. [CrossRef]

- Poffo R, Toschi AP, Pope RB, Montanhesi PK, Santos RS, Teruya A, et al. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017 Jan;6(1):17-26.

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1-39.e14. [CrossRef]

- Carpentier A. Reconstructive valvuloplasty: A new technique of mitral valvuloplasty. Presse Med. 1969;77(27):251–3.

- Wifstad SV, Kildahl HA, Grenne B, Estensen ME ∙ Dalen H ∙ Lovstakken L. Mitral Valve Segmentation and Tracking from Transthoracic Echocardiography Using Deep Learning. Ultrasound Med Biol . 2024;50(5):661-670.

- Messika-Zeitoun D, Theriault-Lauzier, Burwash IG. Diagnosis of Mitral Valve Prolapse Using Artificial Intelligence: Is it Ready for Primetime? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging . 2025 29:S1936-878X(25)00514-5.

- Wu Z, Ge Z, Ge Z, Xing Y, Zhao W, Dong L, et al. Feasibility validation of automatic diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse from multi-view echocardiographic sequences based on deep neural network. Eur Heart J Imaging Methods Pract . 2024;2(4):qyae086. [CrossRef]

- Al-Alusi MA, Lau ES, Small AM, Reeder C, Shnitzer T, Andrews CT, et al. A Deep Learning Model to Identify Mitral Valve Prolapse From the Echocardiogram. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2025:S1936-878X(25)00474-7. [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh M1, Behnam H, Hosseinsabet A, Gifani P. Automatic morphological classification of mitral valve diseases in echocardiographic images based on explainable deep learning methods. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg . 2022;17(2):413-425. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n=102) |

Etiology | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVP (n=59) |

PFO (n=43) |

|||

| Sex | 0.001 | |||

| Female | 43 (42.2) | 17 (28.8) | 26 (60.5) | |

| Male | 59 (57.8) | 42 (71.2) | 17 (39.5) | |

| Age, years | 0.006 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 57,2 ± 18.1 | 61.4 ± 17.2 | 51.5 ± 18 | |

| Weight, Kg | 0,123 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 74.4 ± 15.1 | 76.4 ± 16.1 | 71.7 ± 13.4 | |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 0,232 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 25.4 ± 3,8 | 25.8 ± 4.2 | 24.9 ± 3.2 | |

| Body surface, m2 | 0.134 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.86 ± 0.23 | 1.89 ± 0.25 | 1.82 ± 0.20 | |

| Variable | Total (n=102) |

Etiology | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVP (n=59) |

PFO (n=43) |

|||

| LV diastolic diameter, mm | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 50.4 ± 7.4 | 53.8 ± 7.1 | 45.6 ± 4.7 | |

| Septum diastolic diameter, mm | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 9.6 ± 1.,7 | 10.2 ± 1.6 | 8.8 ± 1.7 | |

| Posterior wall diastolic diameter, mm | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 9.3 ± 1.5 | 9.8 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 1.4 | |

| RV diastolic diameter, mm | 0.808 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 25.2 ± 3.4 | 25.5 ± 3.4 | 25.1 ± 3.3 | |

| LVEF, % | 0.030 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 61.8 ± 8 | 60.4 ± 9.9 | 63.6 ± 3.8 | |

| LA anteroposterio diameter, mm | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 40.7 ± 8.3 | 45.4 ± 7.2 | 34.3 ± 4.8 | |

| LA Volume, ml | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 42.9 ± 16.8 | 51,5 ± 16,8 | 31 ± 6 | |

| PSAP, mm Hg | <0.001 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 31.9 ± 12.9 | 34.9 ± 13.8 | 24.1 ± 4.7 | |

| Variable | Etiology | Difference (IC95%) |

Hedges’ g (IC95%) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVP (n=59) |

PFO (n=43) |

||||

| AP Diameter | 4.15 ± 0.47 | 3.48 ± 0.31 | 0.67 (0.52 a 0.83) |

1.62 (1.17 a 2.08) |

<0.001 |

| AL-PM_Diameter | 4.43 ± 0.61 | 3.57 ± 0.29 | 0.86 (0.68 a 1.04) |

1.72 (1.26 a 2.17) |

<0.001 |

| Sphericity_Index (AP / AL-PM) | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | -0.04 (-0.07 a -0.02) |

-0.69 (-1.08 a -0.31) |

<0.001 |

| Commissural_Diameter | 4.33 ± 0.58 | 3.36 ± 0.28 | 0.97 (0.80 a 1.14) |

2.01 (1.53 a 2.50) |

<0.001 |

| Saddle_Shaped_Annulus_Area (3D) | 15.0 ± 3.5 (n=56) |

10.4 ± 1.6 (n=42) |

4.6 (3.5 a 5.6) |

1.56 (1.10 a 2.02) |

<0.001 |

| Saddle_Shaped_Annulus_Perimeter (3D) | 14.2 ± 1.7 (n=55) |

11.9 ± 0.9 (n=42) |

2.3 (1.8 a 2.9) |

1.68 (1.21 a 2.15) |

<0.001 |

| D-Shaped_Annulus_Area (2D) | 13.3 ± 3.3 (n=54) |

8.8 ± 1.5 (n=42) |

4.5 (3.5 a 5.5) |

1.70 (1.23 a 2.17) |

<0.001 |

| D-Shaped_Annulus_Perimeter | 13.2 ± 2.1 (n=54) |

11.0 ± 0.9 (n=42) |

2.2 (1.6 a 2.9) |

1.34 (0.89 a 1.78) |

<0.001 |

| Annulus_Height | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 0.91 ± 0.20 | 0.09 (0.01 a 0.18) |

0.41 (0.01 a 0.80) |

0.044 |

| Non-planar_Angle | 143.9 ± 11.5 | 135.7 ± 9.7 | 8.2 (4.0 a 12.3) |

0.75 (0.34 a 1.16) |

<0.001 |

|

Tenting_Volume Mediana (P25 – P75) |

2.45 (1.59 – 3.83) (n=36) |

3.37 (2.85 – 3.37) (n=42) |

-0.85 (-1.59 a -0.11) |

-0.76 (-1.41 a 0.05) |

0.039 |

| Coaptation_Depht | 9.3 ± 5.2 (n=56) |

11.1 ± 2.4 (n=42) |

-1.8 (-3.4 a -0.3) |

-0.44 (-0.83 a -0.04) |

0.020 |

| Tenting_Area | 1.66 ± 0.94 (n=51) |

1.99 ± 0.62 (n=43) |

-0.33 (-0.66 a 0.00) |

-0.40 (-0.81 a 0.00) |

0.052 |

| Angle_Aao-AP | 112.5 ± 10.2 | 115.6 ± 8.4 | -3.1 (-6.8 a 0.5) |

-0.33 (-0.72 a 0.06) |

0.104 |

|

Maximum_Prolapse_Height Mediana (P25 – P75) |

7.19 (3.61 – 8.86) (n=54) |

1.04 (1.04 – 2.26) (n=41) |

5.91 (4.29 a 7.53) |

4.22 (2.69 a 6.40) |

<0.001 |

|

Maximal_Open_Coaptaiton_Gap Mediana (P25 – P75) |

2.11 (0 – 3.91) (n=17) |

0.00 (0 – 1.88) (n=10) |

2.11 (-0.54 a 4.76) |

0.53 (0.00 a 2.62) |

0.184 |

| Maximal_Open_Coaptation_Width | 42.4 ± 7.8 (n=54) |

32.1 ± 2.9 (n=40) |

10.3 (8.0 a 12.6) |

1.63 (1.16 a 2.11) |

<0.001 |

|

Total_Open_Coaptation_Area (3D) Mediana (P25 – P75) |

0.19 (0 – 0.54) (n=17) |

0.00 (0 – 0.24) (n=10) |

0.19 (-0.25 a 0.63) |

0.08 (0.00 a 0.45) |

0.225 |

| Anterior_Leaflet_Area | 8.92 ± 2.32 (n=59) |

6.10 ± 1.90 (n=42) |

2.82 (1.99 a 3.66) |

1.30 (0.86 a 1.73) |

<0.001 |

| Posterior_Leaflet_Area | 10.64 ± 3.26 (n=59) |

7.38 ± 4.20 (n=42) |

3.26 (1.71 a 4.80) |

0.88 (0.46 a 1.29) |

<0.001 |

| Distal_Anterior_Leaflet_Angle | 19.8 ± 10.8 (n=59) |

28.1 ± 6.4 (n=41) |

-8.3 (-11.7 a -4.8) |

-0.89 (-1.26 a -0.51) |

<0.001 |

| Posterior_Leaflet _Angle | 29.0 ± 18.4 (n=59) |

38.4 ± 11.9 (n=41) |

-9.4 (-15.4 a -3.4) |

-0.58 (-0.97 a -0.19) |

0.005 |

| Anterior_Leaflet_Lenght | 2.93 ± 0.48 (n=58) |

2.54 ± 0.56 (n=42) |

0.39 (0.17 a 0.60) |

0.74 (0.33 a 1.15) |

<0.001 |

| Posterio_Leaflte_Lenght | 2.52 ± 0.55 (n=59) |

1.96 ± 0.45 (n=42) |

0.56 (0.37 a 0.76) |

1.09 (0.67 a 1.52) |

<0.001 |

| Annulus_Area (2D) | 14.5 ± 3.6 (n=58) |

9.9 ± 1.6 (n=42) |

4.6 (3.5 a 5.6) |

1.54 (1.09 a 1.99) |

<0.001 |

| Anterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (2D) | 4.08 ± 0.70 (n=57) |

3.08 ± 0.26 (n=41) |

1.00 (0.80 a 1.21) |

1.77 (1.29 a 2.24) |

<0.001 |

| Anterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (3D) | 4.26 ± 0.75 (n=57) |

3.17 ± 0.29 (n=41) |

1.09 (0.86 a 1.30) |

1.77 (1.30 a 2.25) |

<0.001 |

| Posterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (2D) | 4.08 ± 0.70 (n=57) |

3.08 ± 0.26 (n=41) |

1.00 (0.80 a 1.20) |

1.78 (1.30 a 2.25) |

<0.001 |

| Posterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (3D) | 4.25 ± 0.74 (n=57) |

3.30 ± 0.84 (n=41) |

0.95 (0.62 a 1.27) |

1.21 (0.77 a 1.64) |

<0.001 |

| C-Shaped_Annulus | 10.37 ± 1.34 (n=57) |

8.34 ± 0.89 (n=42) |

2.03 (1.58 a 2.47) |

1.72 (1.25 a 2.18) |

<0.001 |

| Annular_Displacement (max) | 9.8 ± 2.6 (n=57) |

10.2 ± 1.8 (n=41) |

-0.4 (-1.3 a 0.5) |

-0.18 (-0.58 a 0.22) |

0.384 |

| Annular_Displacement_Velocity (max) | 35.3 ± 9.0 (n=9) |

57.0 ± 20.9 (n=6) |

-21.7 (-43.7 a 0.3) |

-1.38 (-2.27 a -0.50) |

0.052 |

| Tenting_Volume_Fraction | 55.6 ± 24.2 (n=24) |

65.3 ± 23.7 (n=40) |

-9.7 (-22.2 a 2.8) |

-0.40 (-0.90 a 0.10) |

0.121 |

|

Annulus_Area_Fraction (2D) Median (P25 – P75) |

7.7 (4.0 – 17.2) (n=53) |

14.3 (9.1 – 27.7) (n=42) |

-6.9 (-14.1 a 0.25) |

-7.10 (-10.80 a -1.50) |

0.006 |

| ERO (cm²) | Regurgitant Volume (ml/beat) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.43 | 62.9 |

| SD | 0.11 | 14.2 |

| Median | 0.42 | 64 |

| P25 | 0.35 | 54 |

| P75 | 0.48 | 70 |

| Minimum | 0.20 | 30 |

| Maximum | 0.77 | 115 |

| Variable | Total (n=51) |

ERO | p-Value | Effect Size # | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0.48cm² (n=12) |

<0.48cm² (n=39) |

|||||

| AP Diameter | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.21 ± 0.46 | 4.35 ± 0.46 | 4.17 ± 0.46 | 0.223 | 0.41 | |

| AL-PM_Diameter | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.49 ± 0.58 | 4.70 ± 0.64 | 4.42 ± 0.56 | 0.147 | 0.49 | |

| Sphericity_Index (AP / AL-PM) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 0.461 | 0.47 | |

| Commissural_Diameter | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.37 ± 0.60 | 4.58 ± 0.68 | 4.30 ± 0.56 | 0.160 | 0.47 | |

| Saddle_Shaped_Annulus_Area (3D) | (n=48) | (n=10) | (n=38) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 15.3 ± 3.6 | 15.9 ± 4.0 | 15.1 ± 3.5 | 0.530 | 0.22 | |

| Saddle_Shaped_Annulus_Perimeter (3D) | (n=48) | (n=10) | (n=38) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 14.3 ± 1.7 | 14.6 ± 1.9 | 14.2 ± 1.7 | 0.545 | 0.22 | |

| D-Shaped_Annulus_Area (2D) | (n=47) | (n=10) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 13.5 ± 3.3 | 14.1 ± 3.8 | 13.4 ± 3.3 | 0.580 | 0.20 | |

| D-Shaped_Annulus_Perimeter | (n=47) | (n=10) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 13.3 ± 2.2 | 13.7 ± 1.8 | 13.1 ± 2.3 | 0.490 | 0.25 | |

| Annulus_Height | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 0.97 ± 0.24 | 1.01 ± 0.25 | 0.588 | -0.18 | |

| Non-planar_Angle | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 144.0 ± 11.5 | 145.3 ± 10.6 | 143.6 ± 11.9 | 0.652 | 0.15 | |

| Tenting_Volume | (n=31) | (n=5) | (n=26) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

2.10 (1.58 – 3.60) |

1.86 (1.14 – 3.42) |

2.18 (1.59 – 3.60) |

0.809 | -0.08 | |

| Minimum – maximum | 0.17 – 8.53 | 1.04 – 8.53 | 0.17 – 7.34 | |||

| Coaptation_Depht | (n=48) | (n=10) | (n=38) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) Minimum – maximum |

9.2 (4.7 – 12.8) |

7.1 (4.7 – 14.6) |

10.6 (4.7 – 12.5) |

0.676 | -0.09 | |

| 0.5 – 19.5 | 1.7 – 19.5 | 0.5 – 16.3 | ||||

| Tenting_Area | (n=44) | (n=10) | (n=34) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

1.37 (1.02 – 1.98) |

1.02 (0.67 – 1.31) |

1.53 (1.17 – 2.13) |

0.048 | -0.41 | |

| Minimum – maximum | 0.20 – 4.53 | 0.38 – 4.53 | 0.20 – 3.50 | |||

| Angle_Aao-AP | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 112.7 ± 10.9 | 112.5 ± 9.7 | 112.8 ± 11.3 | 0.933 | -0.03 | |

| Maximum_Prolapse_Height | (n=46) | (n=10) | (n=36) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

7.20 (3.68 – 8.86) |

7.87 (6.95 – 8.86) |

6.65 (3.65 – 8.82) |

0.228 | 0.39 | |

| Minimum – maximum | 0.39 – 14.63 | 1.57 – 11.64 | 0.88 – 14.63 | |||

| Maximal_Open_Coaptaiton_Gap | (n=16) | (n=3) | (n=13) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

1.76 (0 – 3.58) |

0 (0 – 11.74) |

2.11 (0.3 – 3.24) |

0.721 | 0.18 | |

| Minimum – maximum | 0 – 11.74 | 0 – 11.74 | 0 – 5.63 | |||

| Maximal_Open_Coaptation_Width | (n=46) | (n=10) | (n=36) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 42.4 ± 7.9 | 42.8 ± 7.9 | 42.3 ± 8.3 | 0.842 | 0.07 | |

| Total_Open_Coaptation_Area (3D) | (n=16) | (n=3) | (n=13) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

0.17 (0 – 0.53) |

0 (0 – 2.79) |

0.19 (0.02 – 0.52) |

0.721 | 0.18 | |

| Minimum – maximum | 0 – 2.79 | 0 – 2.79 | 0 – 0.97 | |||

| Anterior_Leaflet_Area | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.9 ± 2.4 | 9.5 ± 2.5 | 8.8 ± 2.3 | 0.346 | 0.31 | |

| Posterior_Leaflet_Area | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.9 ± 3.4 | 12.7 ± 4.3 | 10.4 ± 2.9 | 0.031 | 0.74 | |

| Distal_Anterior_Leaflet_Angle | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 19.7 ± 10.9 | 17.7 ± 11.1 | 20.3 ± 10.9 | 0.467 | -0.24 | |

| Posterior_Leaflet _Angle | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 15.4 | 23.7 ± 17.1 | 28.0 ± 14.9 | 0.395 | 0.28 | |

| Anterior_Leaflet_Lenght | (n=50) | (n=12) | (n=38) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.89 ± 0.45 | 2.91 ± 0.55 | 2.89 ± 0.42 | 0.899 | 0.04 | |

| Posterio_Leaflte_Lenght | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.58 ± 0.56 | 2.88 ± 0.67 | 2.48 ± 0.50 | 0.032 | 0.73 | |

| Annulus_Area (2D) | (n=50) | (n=12) | (n=38) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 14.8 ± 3.7 | 16.2 ± 4.2 | 14.3 ± 3.5 | 0.115 | 0.53 | |

| Anterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (2D) | (n=49) | (n=12) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.10 ± 0.71 | 4.21 ± 0.72 | 4.07 ± 0.71 | 0.548 | 0.20 | |

| Anterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (3D) | (n=49) | (n=12) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.26 ± 0.76 | 4.39 ± 0.77 | 4.22 ± 0.76 | 0.527 | 0.21 | |

| Posterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (2D) | (n=49) | (n=12) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.10 ± 0.70 | 4.21 ± 0.72 | 4.06 ± 0.71 | 0.521 | 0.21 | |

| Posterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (3D) | (n=49) | (n=12) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.26 ± 0.74 | 4.36 ± 0.72 | 4.22 ± 0.75 | 0.577 | 0.19 | |

| C-Shaped_Annulus | (n=49) | (n=12) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 10.48 ± 1.37 | 10.90 ± 1.55 | 10.35 ± 1.30 | 0.226 | 0.41 | |

| Annular_Displacement (max) | (n=49) | (n=12) | (n=37) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 9.96 ± 2.62 | 10.46 ± 2.81 | 9.80 ± 2.57 | 0.452 | 0.25 | |

| Annular_Displecement_Velocity (máx) | (n=9) | (n=1) | (n=8) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 35.3 ± 9.0 | 51.3 | 33.3 ± 7.2 | - | - | |

| Tenting_Volume_Fraction | (n=19) | (n=5) | (n=14) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 56.7 ± 24.2 | 50.4 ± 29.0 | 58.9 ± 23.0 | 0.515 | 0.35 | |

| Annulus_Area_Fraction (2D) | (n=45) | (n=11) | (n=34) | |||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

7.6 (3.7 – 17.2) |

6.7 (2.1 – 17.2) |

7.6 (4.0 – 14.1) |

0.700 | 0.08 | |

| Mínimo – máximo | 0.7 – 31.8 | 1.0 – 31.8 | 0.7 – 31.8 | |||

| Variable | Total (n=50) |

Regurgitant volume | p-Value | Effect Size # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 70 ml/beat (n=13) |

< 70 ml/beat (n=37) |

||||||

| AP Diameter | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.21 ± 0.47 | 4.30 ± 0.50 | 4.17 ± 0.46 | 0.410 | 0.27 | ||

| AL-PM_Diameter | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.49 ± 0.58 | 4.62 ± 0.65 | 4.44 ± 0.57 | 0.361 | 0.30 | ||

| Sphericity_Index (AP / AL-PM) | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.654 | -0.15 | ||

| Commissural_Diameter | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.37 ± 0.60 | 4.50 ± 0.69 | 4.32 ± 0.57 | 0.381 | 0.29 | ||

| Saddle_Shaped_Annulus_Area (3D) | (n=47) | (n=12) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 15.2 ± 3.6 | 15.7 ± 3.9 | 15.1 ± 3.6 | 0.632 | 0.16 | ||

| Saddle_Shaped_Annulus_Perimeter (3D) | (n=47) | (n=12) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 14.3 ± 1.7 | 14.5 ± 1.9 | 14.2 ± 1.7 | 0.626 | 0.16 | ||

| D-Shaped_Annulus_Area (2D) | (n=46) | (n=12) | (n=34) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 13.5 ± 3.4 | 13.8 ± 3.7 | 13.4 ± 3.3 | 0.727 | 0.12 | ||

| D-Shaped_Annulus_Perimeter | (n=46) | (n=12) | (n=34) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 13.3 ± 2.2 | 13.6 ± 1.8 | 13.1 ± 2.3 | 0.555 | 0.20 | ||

| Annulus_Height | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 0.99 ± 0.28 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | 0.882 | -0.05 | ||

| Non-planar_Angle | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 144.0 ± 11.6 | 144.7 ± 11.0 | 143.7 ± 12.0 | 0.796 | 0.08 | ||

| Tenting_Volume | (n=30) | (n=6) | (n=24) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

2.00 (1.58 – 3.42) |

2.64 (1.16 – 4.06) |

2.00 (1.59 – 3.08) |

0.699 | 0.11 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0.17 – 8.53 | 1.14 – 8.53 | 0.17 – 7.34 | ||||

| Coaptation_Depht | (n=47) | (n=12) | (n=35) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

9.1 (4.7 – 12.5) |

7.1 (3.2 – 12.4) |

10.6 (4.7 – 12.5) |

0.458 | -0.15 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0.5 – 19.5 | 1.7 – 19.5 | 0.5 – 15.5 | ||||

| Tenting_Area | (n=43) | (n=10) | (n=33) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

1.36 (1.02 – 1.96) |

1.02 (0.66 – 1.81) |

1.40 (1.17 – 1.96) |

0.206 | -0.27 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0.20 – 4.53 | 0.38 – 4.53 | 0.20 – 3.50 | ||||

| Angle_Aao-AP | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 112.6 ± 10.9 | 112.4 ± 9.3 | 112.6 ± 11.5 | 0.954 | -0.02 | ||

| Maximum_Prolapse_Height | (n=45) | (n=12) | (n=33) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

7.44 (3.85 – 8.86) |

7.87 (4.02 – 8.86) |

6.85 (3.65 – 8.77) |

0.408 | 0.17 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0.88 – 14.63 | 1.57 – 11.64 | 0.88 – 14.63 | ||||

| Maximal_Open_Coaptaiton_Gap | (n=16) | (n=3) | (n=13) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

1.76 (0 – 3.58) |

0 (0 – 11.74) |

2.11 (0.3 – 3.24) |

0.721 | -0.18 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0 – 11.74 | 0 – 11.74 | 0 – 5.63 | ||||

| Maximal_Open_Coaptation_Width | (n=45) | (n=12) | (n=33) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 42.4 ± 8.0 | 42.6 ± 6.3 | 42.4 ± 8.6 | 0.923 | 0.03 | ||

| Total_Open_Coaptation_Area (3D) | (n=16) | (n=3) | (n=13) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

0.17 (0 – 0.53) |

0 (0 – 2.79) |

0.19 (0.02 – 0.52) |

0.721 | -0.18 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0 – 2.79 | 0 – 2.79 | 0 – 0.97 | ||||

| Anterior_Leaflet_Area | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.9 ± 2.4 | 9.3 ± 2.2 | 8.8 ± 2.4 | 0.520 | 0.21 | ||

| Posterior_Leaflet_Area | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.9 ± 3.4 | 12.0 ± 4.3 | 10.5 ± 3.0 | 0.186 | 0.43 | ||

| Distal_Anterior_Leaflet_Angle | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 19.5 ± 10.9 | 16.3 ± 10.1 | 20.6 ± 11.0 | 0.221 | 0.40 | ||

| Posterior_Leaflet _Angle | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 26.7 ± 15.3 | 23.9 ± 18.0 | 27.6 ± 14.4 | 0.458 | -0.24 | ||

| Anterior_Leaflet_Lenght | (n=49) | (n=13) | (n=36) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.88 ± 0.45 | 2.94 ± 0.50 | 2.86 ± 0.43 | 0.630 | 0.16 | ||

| Posterio_Leaflte_Lenght | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.58 ± 0.57 | 2.77 ± 0.64 | 2.51 ± 0.53 | 0.159 | 0.46 | ||

| Annulus_Area (2D) | (n=49) | (n=13) | (n=36) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 14.8 ± 3.7 | 15.7 ± 4.2 | 14.4 ± 3.6 | 0.299 | 0.34 | ||

| Anterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (2D) | (n=48) | (n=13) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.11 ± 0.71 | 4.20 ± 0.69 | 4.07 ± 0.73 | 0.598 | 0.17 | ||

| Anterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (3D) | (n=48) | (n=13) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.27 ± 0.77 | 4.34 ± 0.74 | 4.24 ± 0.79 | 0.705 | 0.12 | ||

| Posterio_Closure_Line_Lenght (2D) | (n=48) | (n=13) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.10 ± 0.71 | 4.20 ± 0.69 | 4.07 ± 0.73 | 0.579 | 0.18 | ||

| Posterior_Closure_Line_Lenght (3D) | (n=48) | (n=13) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.26 ± 0.75 | 4.31 ± 0.69 | 4.24 ± 0.78 | 0.775 | 0.09 | ||

| C-Shaped_Annulus | (n=48) | (n=13) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.48 ± 1.38 | 10.64 ± 1.54 | 10.42 ± 1.34 | 0.625 | 0.16 | ||

| Annular_Displacement (max) | (n=48) | (n=13) | (n=35) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.02 ± 2.61 | 10.01 ± 3.37 | 10.02 ± 2.33 | 0.982 | -0.01 | ||

| Annular_Displecement_Velocity (máx) | (n=9) | (n=3) | (n=6) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

31.6 (28.5 – 39.6) |

38.9 (25.5 – 51.3) |

30.4 (28.5 – 39.6) |

0.905 | 0.11 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 25.5 – 51.3 | 25.5 – 51.3 | 27.3 – 45.8 | ||||

| Tenting_Volume_Fraction | (n=18) | (n=5) | (n=13) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 56.4 ± 29.8 | 51.4 ± 29.8 | 58.3 ± 23.8 | 0.616 | -0.27 | ||

| Annulus_Area_Fraction (2D) | (n=44) | (n=13) | (n=31) | ||||

| Median (P25 – P75) |

7.5 (3.6 – 17.2) |

6.7 (2.3 – 17.2) |

7.6 (3.8 – 14.1) |

0.934 | -0.02 | ||

| Minimum – maximum | 0.7 – 31.8 | 0.9 – 31.8 | 0.7 – 31.8 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).