1. Introduction

Network telemetry has evolved from simple counters to rich flow records and programmable data plane exports, enabling scalable monitoring of high-speed networks [

1]. This abstraction is driven by practical constraints: storage costs, processing overhead, and privacy regulations make continuous packet-level monitoring infeasible for most organizations [

2]. Consequently, modern network security operations rely heavily on aggregated telemetry—flow records, time-binned statistics, and log summaries—rather than full packet capture.

However, this evolution introduces a fundamental trade-off: telemetry abstraction, while necessary for scalability, silently removes forensic evidence required for threat inference [

3]. The transition from packet-level to flow-level and time-aggregated representations fundamentally alters the observable evidence available for forensic analysis and threat reasoning. This challenge is compounded by the widespread adoption of encryption: Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.3 encrypts larger fractions of the handshake, further reducing semantic visibility and shifting feasible reasoning toward metadata and behavioral artifacts [

4]. The ENISA Threat Landscape 2025 reports that a substantial fraction of observed incidents are categorised as “unknown,” reflecting limitations in incident reporting, sector attribution, and outcome visibility in open-source and shared data [

5]. These documented gaps motivate a closer examination of how evidence abstraction and monitoring practices constrain defensible forensic inference in network telemetry architectures. While prior work has extensively studied detection accuracy under different data representations [

6,

7], a critical gap remains:

how does evidence abstraction constrain the defensibility of forensic threat inference, independent of detection or classification accuracy?

This paper introduces a design-time audit framework that, given a telemetry schema (e.g., NetFlow, time-aggregated flows), outputs which MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK) tactic-level hypotheses can no longer be supported due to lost evidence. Our backbone network monitoring context assumes a passive observer with access to packet headers captured at a transit network, without payload visibility, endpoint context, or ground-truth labels. This setting reflects ISP/carrier monitoring realities and constrains the analysis to network-level behavioral patterns observable without endpoint logs or payload data. We restrict analysis to network-observable tactics (e.g., Command and Control, Exfiltration), excluding endpoint-dependent tactics (e.g., Credential Access) per our backbone threat model. This ensures our audit reflects realistic capabilities of network-layer telemetry.

For incident responders, this gap manifests as a critical dilemma: analysts must reason about adversary behavior from partial, archived network evidence, but the challenge is not merely detecting known attack patterns. Instead, they must determine which threat hypotheses can be logically supported given the available evidence representation. For example, does the available evidence representation permit supporting a claim that observed traffic patterns indicate Lateral Movement when only time-aggregated flow statistics are available? Unlike detection-focused studies that measure false-positive rates, our framework evaluates whether a given telemetry layer logically supports or refutes a threat hypothesis (e.g., “This traffic pattern is consistent with Lateral Movement”) based on available evidence artifacts—regardless of the detection algorithm used.

This gap has practical consequences. Security teams may invest in monitoring infrastructure without understanding which classes of forensic inference become non-supportable under their chosen abstraction level. Incident response playbooks may include procedures that require evidence types no longer available in archived telemetry. Without a systematic audit, organizations cannot align their defensive strategies with their actual forensic capabilities.

We present a methodological framework for design-time audit that evaluates which forensic claims remain supportable under a given telemetry architecture. The contribution is methodological: the audit procedure evaluates representational limits of inference rather than proposing a new detection or classification algorithm. We develop a reproducible audit methodology that examines the limits of inference that arise when network evidence is reduced through aggregation and abstraction. Our framework uses MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK) and Detection, Denial, and Disruption Framework Emulating Network Defense (D3FEND)—the de facto industry standards for structured threat and defense modeling—as vocabularies for organizing defensive reasoning, treating them as hypothesis spaces rather than classification taxonomies. While ATT&CK tactics map to adversary behaviors observable at specific evidence layers (e.g., L0 packet timing for “Execution”), D3FEND countermeasures map to defensive actions enabled by those layers (e.g., L1 flow records enable “Network Traffic Throttling” against DDoS). Our audit quantifies how abstraction shifts the actionable defense portfolio. This makes the framework’s outputs directly relevant for security engineers designing telemetry systems. From a networking perspective, the proposed audit framework is intended to support the design and evaluation of network monitoring architectures, rather than post-hoc forensic reconstruction. It provides a systematic method for reasoning about what classes of network-level inference remain feasible under specific telemetry export and aggregation choices.

Using backbone traffic from the MAWI DITL archive [

8] and a literature-grounded inference framework, our audit identifies inference loss that is (a) selective (affecting specific tactics) and (b) structural (erasing relational evidence like host fan-out). Our audit identifies evidence abstraction as a source of unfalsifiable hypotheses—where critical artifacts (e.g., packet timing) are removed, rendering certain threat claims neither provable nor disprovable. The audit reveals that (i) packet-level timing artifacts required to support

Execution hypotheses disappear once monitoring collapses to flows, (ii) entity-linked structural artifacts such as destination fan-out and host-specific periodicity are lost under time-aggregated telemetry, eliminating supportable claims for

Lateral Movement and

Persistence, and (iii) defensive reasoning does not degrade monotonically with abstraction, but instead

transforms the supportable defensive toolkit from behavioral monitoring to rate- and flow-based controls.

Our contributions include: (1) a design-time audit tool for network architects to evaluate and configure telemetry systems (e.g., IPFIX exporters, P4 pipelines) to reason about and provision minimum forensic coverage. We define evidence loss as a reduction in actionable forensic options: when telemetry abstraction removes critical artifacts, certain threat hypotheses become unfalsifiable—neither provable nor disprovable from the available data; (2) restriction to tactic-level inference using ATT&CK as a hypothesis space and D3FEND as defensive applicability, providing a structured vocabulary for reasoning about defensive capabilities under partial observability; (3) demonstration that inference collapse is selective and structural rather than uniform, with defensive reasoning transforming rather than uniformly degrading across abstraction levels, informing the design of hybrid monitoring systems; and (4) positioning the analysis in backbone/ISP monitoring contexts, making the work directly applicable to network-wide security service management and programmable data plane telemetry design.

We review related work on network forensics and evidence abstraction (

Section 2), present our audit methodology (

Section 3), report results from backbone traffic analysis (

Section 4), discuss implications for network monitoring architecture design (

Section 6), and synthesize implications for practice (

Section 5).

2. Related Work

2.1. Backbone and ISP-Level Network Visibility

A key determinant of what can be inferred from network observations is the vantage point and the data product available to the analyst. Longitudinal and large-scale Internet Service Provider (ISP) studies illustrate that backbone monitoring is typically conducted using flow records rather than full packet capture, due to throughput, storage, and privacy constraints. Trevisan et al. analyze multi-year evolution of Internet usage from a national ISP using rich flow-level measurements, showing both the feasibility and the inherent abstraction of ISP-scale observation (e.g., service trends and protocol evolution rather than payload semantics) [

1]. Benes et al. similarly emphasize that high-speed ISP backbones are commonly monitored via IP flows; even then, long-term datasets are difficult to retain and “brief” summary statistics can be insufficient for deeper analyses without further processing [

9].

Other backbone/Internet Exchange Point (IXP) studies demonstrate that even when packet-level traces are available, interpretability remains bounded by what can be reliably observed without endpoint context. Maghsoudlou et al. dissect Internet traffic using port 0 across complementary packet- and flow-level datasets and show that substantial apparent “anomalies” can stem from artifacts such as fragmentation, while only limited subsets provide payload-bearing evidence [

10]. Collectively, these works motivate a backbone-forensics framing in which the analyst must reason from incomplete, sometimes artifact-prone observations, and where evidence is frequently available only in aggregated forms.

A complementary line of work highlights that, at ISP scale, even distinguishing benign background noise from operationally meaningful signals can require carefully designed tests under constrained observability. Gigis et al. propose

Penny, an ISP-deployable test to differentiate spoofed aggregates from non-spoofed traffic that enters at unexpected locations by exploiting retransmission behavior after selectively dropping a small number of TCP packets [

11]. While motivated by operational alerting, the key methodological relevance for backbone forensics is that inference may depend on

what is observable and repeatable under transit constraints, and that seemingly anomalous aggregates can remain ambiguous without additional evidence channels or carefully bounded interventions.

Backbone datasets targeting encrypted traffic further illustrate how ISP visibility is often mediated through derived products rather than raw payloads. Hynek et al. introduce CESNET-TLS-Year22, a year-spanning dataset captured on 100 Gbps backbone links, provided as Transport Layer Security (TLS)-relevant flow representations augmented with limited early-connection packet sequences, packet histograms, and selected fields from the TLS ClientHello [

12]. Although created primarily to support traffic classification research, the dataset design is directly relevant to our framing: it exemplifies the practical evidence surface available at scale for encrypted traffic—metadata and partial handshake-derived artifacts—while underscoring the absence of payload semantics and the resulting need for conservative, uncertainty-aware forensic reasoning.

2.2. Evidence Transformation Through Flow Construction

Transforming packets into flows is not a neutral preprocessing step; it is an evidence transformation that can change what conclusions remain defensible. Flow monitoring configuration choices—especially expiration timeouts—can split, merge, or distort activity patterns that might otherwise be interpretable. Velan and Jirsik explicitly demonstrate that the configuration of flow monitoring affects the resulting flow records and can materially impact downstream analytics, using Slowloris as an example of sensitivity to timeout choices [

3].

At ISP scale, additional uncertainty arises because flow-derived inferences may rely on indirect reasoning from partial telemetry. Schou et al. consider ISP flow analytics under measurement noise and infer flow splitting ratios indirectly from observed demands and link utilization, reflecting the practical reality that operators often cannot directly observe the internal determinants of traffic distribution [

13]. In a complementary operational direction, Flowyager addresses the distributed nature and volume of flow records by constructing compact summaries (Flowtrees) to support interactive, network-wide queries [

14]. While these systems are not designed for forensic inference per se, they underline a central point for evidence-centric reasoning: the construction, configuration, and summarization of flow data defines the boundaries of what can later be reconstructed about temporal ordering, causality, and behavioral structure.

2.3. Time Aggregation, Sampling, and Telemetry Abstraction

Beyond flows, monitoring pipelines commonly introduce additional abstraction through time binning, sampling, and sketching, each of which trades semantic detail for scalability. Magnifier illustrates the operational dependence on sampling for global ISP monitoring and proposes complementing sampling with mirroring to improve coverage without prohibitive overhead [

15]. Du et al. study sampling at the per-flow level and propose self-adaptive sampling to allocate measurement effort unevenly across flows, reflecting that practical measurement policies are rarely uniform and can differentially preserve evidence across traffic classes [

16]. Operational NetFlow pipelines introduce additional temporal abstraction through exporter-driven record generation and reporting delays, which can materially affect what can be inferred

when from flow evidence. He et al. analyze these delays in the context of NetFlow-based ISP Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) monitoring and propose FlowSentry, which leverages sketch-based sliding windows and cross-router correlation to reason over partially reported flow records [

17]. While the objective in that work is accelerated detection, its methodological significance for our study is different: it makes explicit that time-windowing and incremental reporting are intrinsic properties of flow telemetry at scale, and thus that downstream reasoning must treat flow and time-aggregated flow products as

evidence transformed by the monitoring pipeline, not as faithful surrogates for packet-level behavior.

A broad telemetry literature further formalizes these abstractions through compact data structures and programmable data planes. Landau-Feibish et al. survey compact data structures and streaming methods for telemetry in programmable devices, emphasizing the tight memory/compute constraints that force approximate summaries and selective retention [

18]. Several works address the mechanics of time-windowed telemetry—an issue directly relevant to time-aggregated flow evidence. OmniWindow proposes fine-grained sub-windows that can be merged into multiple window types under switch resource constraints [

19]. Namkung et al. show that practical telemetry can suffer accuracy degradation due to delays when pulling and resetting state, emphasizing that implementation and retrieval workflows shape the fidelity of exported summaries [

20]. SketchPlan and AutoSketch raise the abstraction layer for deploying sketch-based telemetry and compiling high-level intents into sketches, again foregrounding that operators ultimately receive derived artifacts rather than raw observations [

21,

22]. SetD4 extends data-plane set representations with deletion and decay, explicitly embedding time-based forgetting into telemetry structures [

23]. F3 explores split execution between ASICs and FPGAs to enable richer monitoring patterns under throughput constraints [

24]. Liu et al. discuss ecosystem-level challenges that hinder the adoption of sketch-based telemetry despite its theoretical appeal, reflecting a persistent gap between what is desirable for visibility and what is feasible at scale [

25].

Long-horizon ISP datasets further illustrate how operational constraints steer evidence products toward time-aggregated abstractions rather than packet- or even flow-complete archives. CESNET-TimeSeries24 provides 40 weeks of time-series traffic statistics derived from an ISP network at the scale of hundreds of thousands of active IP addresses, explicitly motivated by the lack of long-term real-world datasets for forecasting and anomaly analysis and the risk of overestimating conclusions when evaluations rely on synthetic or short-window traces. While the dataset is introduced to support modeling and anomaly/forecasting research, its design choices are directly relevant to backbone forensics: the exported representation is already a temporally aggregated statistical view, which inherently limits the reconstructability of fine-grained behavioral evidence and makes inference dependent on which summary metrics survive the aggregation pipeline [

26]. These contributions collectively motivate treating packet→flow→time-aggregated (and sketch/sampling-based) transformations as a progressive reduction in evidential granularity. They provide concrete technical mechanisms—windowing, decay, sketch compilation, sampling—that explain how inferential capacity can collapse even when monitoring remains operationally effective.

2.4. Architectures Balancing Packet Fidelity and Scalability

Several monitoring architectures explicitly try to balance packet-level fidelity with scalable operation, acknowledging that the choice is not binary. FloWatcher-DPDK demonstrates high-speed software monitoring that can provide tunable statistics at packet and flow levels, illustrating a practical continuum between detailed and summarized evidence products [

27]. MONA introduces adaptive measurement that reduces task sets under bottlenecks to maintain monitoring objectives, again operationalizing a dynamic reduction of observed detail when conditions demand it [

28]. FlexMon and FPGA-based flow monitoring systems aim to provide fine-grained measurement under strict resource constraints in programmable/hardware settings [

29,

30]. Recent work on programmable data planes further emphasizes that the monitoring substrate can shape the evidentiary record by deciding which packet-level properties are preserved versus compressed into statistics. Doriguzzi-Corin et al. propose P4DDLe, using P4-programmable switches to selectively extract raw packet features (including categorical features) and to organize them so that aspects of flow semantics are preserved under resource constraints [

31]. Although positioned toward Network Intrusion Detection System (NIDS) pipelines, the relevant implication for our paper is architectural: it illustrates a principled attempt to mitigate semantic loss introduced by flow/statistical compression, reinforcing our premise that packet→flow→aggregated-flow transformations should be treated as progressive reductions in evidential granularity with direct consequences for what inferences remain defensible.

HybridMon directly targets the tension between flow efficiency and packet-level usefulness by combining condensed packet-level monitoring with selective flow aggregation in programmable switches [

32]. Hardegen’s scope-based monitoring highlights that even within “flow monitoring,” the analyst may enlarge scope (e.g., bidirectional context, subflows in time windows) to regain granularity, at the cost of overhead [

33]. Although these works are often motivated by operational monitoring or intrusion detection pipelines, their relevance here is methodological: they show that modern infrastructures deliberately shape the evidentiary record by selectively exporting different representations over time and under load—exactly the conditions under which forensic reasoning must quantify what inferences remain defensible.

2.5. Encrypted Traffic and Forensic Constraints

The growth of encryption further reduces semantic visibility and shifts feasible reasoning toward metadata, timing, and behavioral artifacts. Surveys of encrypted traffic analysis characterize the space of approaches and their dependence on what parts of the protocol remain observable. Papadogiannaki and Ioannidis survey applications, techniques, and countermeasures in encrypted traffic analysis, emphasizing both the feasibility of inference from encrypted traces and the privacy-driven limitations and evasion dynamics that constrain what can be concluded [

34]. Sharma and Lashkari provide a more recent survey focused on identification/classification techniques and challenges in encrypted traffic, reflecting the broad research emphasis on learning-based inference from metadata while also noting dataset and operational constraints [

35].

TLS 1.3 intensifies this trend by encrypting larger fractions of the handshake, motivating new methods and highlighting limitations of older approaches. Zhou et al. survey TLS 1.3 encrypted traffic analysis, reviewing the impact of TLS 1.3 features (e.g., 0-RTT, PFS, ECH) and cataloging families of analysis methods and datasets [

4]. At a more application-specific forensic level, Sarhan et al. propose a framework for digital forensics of encrypted real-time traffic in messaging and Voice over IP (VoIP) contexts, aiming to extract user behavior from encrypted traces [

36]. Notably, such work often assumes the availability of traces and features that can include application-specific patterns and, in some settings, deeper inspection capabilities than backbone monitoring typically affords.

Within backbone-forensics constraints—packet headers without payload and no endpoint ground truth—these surveys and frameworks are most relevant for establishing why the inference problem is structurally underdetermined and why conservative, uncertainty-aware reasoning is necessary when evidence is reduced from packets to flows and then time-aggregated flows.

2.6. ATT&CK and D3FEND as Reasoning Frameworks

ATT&CK and D3FEND are frequently used to organize threat knowledge and defensive measures, but their role varies substantially across studies. Al-Sada et al. provide a comprehensive survey of how ATT&CK has been leveraged across sectors and methodologies, offering a useful reference for the breadth of ATT&CK-based work and the variety of assumptions and auxiliary data employed [

37]. This diversity is central for evidence-centric analysis: many ATT&CK uses implicitly rely on rich visibility (endpoint telemetry, payload inspection, curated labels, or incident reports) that may not hold in backbone settings.

Several works combine ATT&CK with D3FEND to connect adversary behavior representations with defensive actions. Yousaf and Zhou demonstrate ATT&CK/D3FEND modeling in a maritime cyber-physical scenario and propose defensive mechanisms informed by the frameworks [

38]. Vaseghipanah et al. integrate ATT&CK and D3FEND into a game-theoretic model for digital forensic readiness, mapping Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) behaviors to defensive countermeasures and deriving strategic recommendations under uncertainty [

39]. These studies highlight the utility of ATT&CK/D3FEND as organizing structures for reasoning about threats and defenses, but they often operate at a level where attacker–defender modeling, domain context, or expert weighting supplies additional semantics beyond what passive backbone artifacts can justify.

A further methodological consideration is the common tendency in parts of the broader literature to treat ATT&CK at the technique level as a labeling scheme (e.g., as targets for detection or classification). In contrast, the present paper’s alignment is closer to survey- and modeling-oriented uses that treat ATT&CK primarily as a vocabulary for structured reasoning. By restricting ATT&CK usage to the tactic level and grounding any artifact–tactic support exclusively in published descriptions, the analysis aims to remain faithful to what can be justified under partial observability. Similarly, D3FEND is used here to reason about defensive applicability—which defensive technique categories remain logically actionable given the evidence product—rather than to evaluate mitigation success or deployment efficacy, thereby maintaining separation between evidential support and operational effectiveness.

2.7. Gap and Contribution

The reviewed literature demonstrates that (i) backbone monitoring relies on abstracted telemetry (flow records, time-aggregated statistics), (ii) evidence transformation through flow construction and temporal aggregation affects what can be inferred, and (iii) ATT&CK and D3FEND provide structured vocabularies for organizing threat reasoning and defensive actions. However, prior work has not explicitly provided a reproducible, representation-driven audit that determines which ATT&CK tactic-level hypotheses remain defensibly supportable under progressively abstracted network telemetry, nor a framework for evaluating telemetry architectures based on forensic coverage.

Prior work focuses on (i) detection accuracy under different data representations (exemplified by empirical studies comparing packet- vs. flow-based detection [

6,

7]), (ii) operational efficiency of telemetry systems [

14,

15,

32], (iii) dataset creation for traffic analysis [

12,

26], or (iv) strategic modeling using ATT&CK/D3FEND with rich visibility (endpoint logs, payload access, or domain context) [

38,

39]. We did not find prior work that addresses the

defensibility of forensic inference under partial observability or provides a systematic audit of which threat hypotheses become non-supportable as evidence is abstracted.

What we add: We provide a design-time audit framework that (i) systematically evaluates which MITRE ATT&CK tactic-level hypotheses become non-supportable as evidence is transformed from packets (L0) to flows (L1) to time-aggregated statistics (L2), (ii) maps artifact availability to tactic support using literature-grounded associations, (iii) quantifies defensive applicability using D3FEND under backbone-forensics constraints (no payload, no endpoint context, no ground truth), and (iv) demonstrates that inference collapse is selective and structural rather than uniform, with defensive reasoning transforming rather than uniformly degrading. Practically, the audit outputs a “forensic coverage report” that can be used to guide IPFIX schema choices, exporter configurations (timeouts/binning), and programmable telemetry designs. This framework enables network architects to evaluate telemetry designs and configure systems (e.g., IPFIX exporters, P4 pipelines) to reason about and provision minimum forensic coverage.

Table 1.

Comparison of related work on network forensics and telemetry abstraction. Evidence products: PCAP headers (packet-level), Flow (bidirectional flow records), Time-series (aggregated statistics), Hybrid (selective packet/flow), Sketch (approximate summaries). Primary goals: Characterization (traffic analysis), Telemetry system (monitoring architecture), Detection (threat detection/monitoring), Operational Test (ISP-deployable testing), Dataset (data collection/curation), Survey (literature review), Modeling (threat/defense modeling), Forensic audit (supportability evaluation).

Table 1.

Comparison of related work on network forensics and telemetry abstraction. Evidence products: PCAP headers (packet-level), Flow (bidirectional flow records), Time-series (aggregated statistics), Hybrid (selective packet/flow), Sketch (approximate summaries). Primary goals: Characterization (traffic analysis), Telemetry system (monitoring architecture), Detection (threat detection/monitoring), Operational Test (ISP-deployable testing), Dataset (data collection/curation), Survey (literature review), Modeling (threat/defense modeling), Forensic audit (supportability evaluation).

| Work |

Evidence Product |

Vantage |

Primary Goal |

ATT&CK/D3FEND |

Addresses Supportability? |

| Trevisan et al. (2018) |

Flow |

Backbone/ISP |

Characterization |

None |

× |

| Velan and Jirsik (2020) |

Flow |

Network monitoring |

Telemetry system |

None |

× |

| Flowyager (Saidi et al., 2020) |

Flow |

Network monitoring |

Telemetry system |

None |

× |

| Gigis et al. (2024) |

Flow/Active Test |

Backbone/ISP |

Operational Test |

None |

× |

| He et al. (2025) |

Flow |

Backbone/ISP |

Detection |

None |

× |

| P4DDLe (2024) |

Hybrid |

Programmable switches |

Telemetry system |

None |

× |

| HybridMon (Fink et al., 2025) |

Hybrid |

Programmable switches |

Telemetry system |

None |

× |

| Papadogiannaki and Ioannidis (2021) |

PCAP/Flow |

Various |

Survey |

None |

× |

| CESNET-TimeSeries24 (Koumar et al., 2025) |

Time-series |

Backbone/ISP |

Dataset |

None |

× |

| Yousaf and Zhou (2024) |

Various |

Enterprise/CPS |

Modeling |

Both (technique) |

× |

| Vaseghipanah et al. (2025) |

Various |

Enterprise |

Modeling |

Both (technique) |

× |

| This work |

L0/L1/L2 |

Backbone/ISP |

Forensic audit |

Both (tactic) |

|

3. Materials and Methods

This work provides an audit procedure for evaluating how modern network monitoring practices affect the feasibility and depth of threat inference. We develop a reproducible audit procedure that identifies the limits of inference that arise when network evidence is progressively reduced through aggregation and abstraction.

To illustrate the core mechanism, consider a concrete example: the artifact “destination fan-out” (number of unique destinations per source) is required to support the ATT&CK Lateral Movement hypothesis. This artifact is computable from flow records (L1) but lost in time-aggregated counts (L2), where only bin-level aggregate statistics remain. Consequently, Lateral Movement becomes non-supportable at L2, regardless of how suspicious the aggregate statistics appear. This example demonstrates how evidence abstraction directly constrains which threat hypotheses can be defensibly supported.

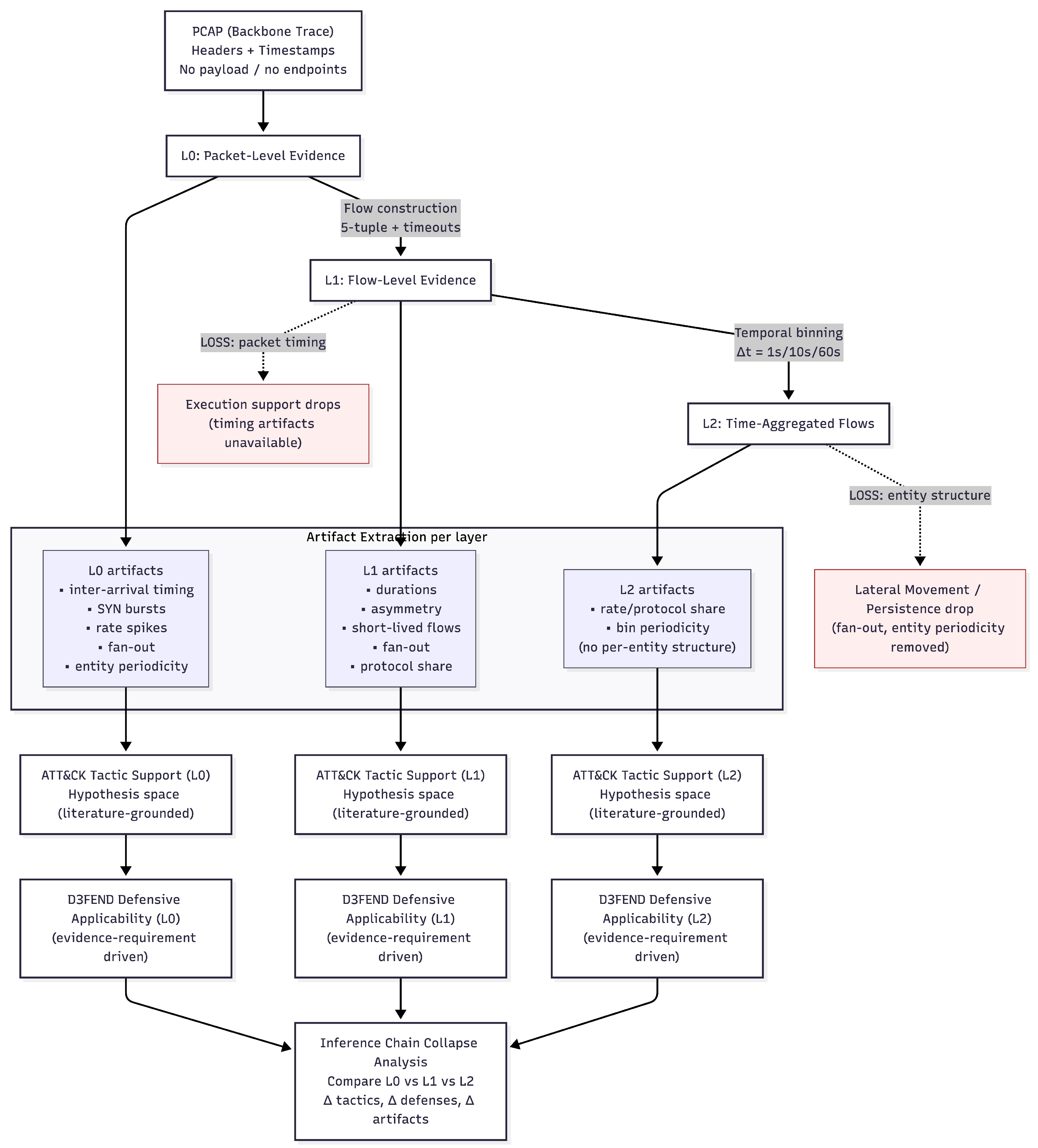

Figure 1.

Evidence abstraction and inference chain collapse across network monitoring layers. Starting from backbone packet traces, network evidence is progressively transformed from packet-level (L0) to flow-level (L1) and time-aggregated (L2) representations. At each layer, only artifacts computable from the available evidence are extracted and used to support literature-grounded ATT&CK tactic-level hypothesis spaces. Defensive reasoning is performed using MITRE D3FEND based solely on evidence requirements, not defensive effectiveness. The figure highlights where abstraction induces loss of packet-timing and entity-structure artifacts, leading to collapse of defensible tactic support and defensive applicability.

Figure 1.

Evidence abstraction and inference chain collapse across network monitoring layers. Starting from backbone packet traces, network evidence is progressively transformed from packet-level (L0) to flow-level (L1) and time-aggregated (L2) representations. At each layer, only artifacts computable from the available evidence are extracted and used to support literature-grounded ATT&CK tactic-level hypothesis spaces. Defensive reasoning is performed using MITRE D3FEND based solely on evidence requirements, not defensive effectiveness. The figure highlights where abstraction induces loss of packet-timing and entity-structure artifacts, leading to collapse of defensible tactic support and defensive applicability.

Our methodology is structured around a principled inference chain:

Observed Network Artifacts→ATT&CK Tactic-Level Support (Hypothesis Space)→D3FEND Defensive Applicability.

This chain enables structured reasoning when evidence is incomplete or ambiguous.

3.1. Threat Model and Forensic Assumptions

Our backbone network monitoring context assumes a passive forensic observer operating under realistic backbone monitoring constraints. The observer has access to packet headers captured at a transit network, without payload visibility, endpoint context, or ground-truth labels. This setting reflects ISP/carrier monitoring realities: retrospective analysis of backbone traffic, ISP-level monitoring, or post-incident investigations relying on archived network traces. This framing explicitly avoids assumptions common in prior network forensics work: we do not assume enterprise visibility, endpoint logs, or ground truth. This positioning is uncommon in forensic inference studies, which typically assume richer visibility, and makes the analysis directly relevant to Security Operations Center (SOC) / Incident Response (IR) methodology and operational security contexts.

No assumptions are made about attacker identity, malware families, or campaign attribution. Consequently, our analysis deliberately excludes ATT&CK techniques that require host-level visibility, payload inspection, or semantic knowledge of application-layer content. Threat reasoning is restricted to high-level behavioral patterns observable at the network level, and we use ATT&CK strictly at the tactic level as a vocabulary for organizing hypothesis spaces, not as a classification taxonomy. When we refer to tactics such as Execution, we mean execution-related network manifestations (e.g., timing patterns consistent with scheduled task execution or script execution) observable from packet headers and flow records, not endpoint-level execution events that require host visibility.

3.2. Evidence Representation Layers

Starting from raw packet capture (PCAP) data, we construct three increasingly abstract representations of network evidence:

Packet-Level Evidence: Individual packets with full header information and precise inter-packet timing.

Flow-Level Evidence: Bidirectional flows constructed using a standard 5-tuple with timeout-based aggregation.

Time-Aggregated Flow Evidence: Flow statistics further aggregated into fixed temporal bins (e.g., 10s or 60s intervals), emulating common monitoring and logging practices.

These representations allow us to model evidence loss as a controlled, stepwise process, enabling systematic analysis of how forensic visibility degrades as monitoring granularity decreases.

3.3. Network Artifact Extraction

From each evidence layer, we extract a set of network forensic artifacts. Artifacts are defined as observable traffic characteristics that may support forensic reasoning, independent of any specific detection algorithm. Examples include SYN-dominant connection patterns, destination fan-out, rate spikes, protocol imbalance, temporal periodicity, and directional asymmetry.

Importantly, artifacts are treated as observations, not as indicators of confirmed malicious activity. Their presence motivates further reasoning but does not, by itself, constitute evidence of compromise or attack.

3.4. ATT&CK Tactic-Level Support (Literature-Grounded)

Observed artifacts are linked to tactic-level hypotheses using MITRE ATT&CK as a structured vocabulary, restricted to the tactic level. Technique-level identification requires host context unavailable in backbone traces, so we restrict analysis to tactics as coarse-grained intent categories.

We use ATT&CK tactics as a vocabulary to organize a literature-grounded hypothesis space: an artifact provides support only for those tactics for which a published source describes a consistent network-visible behavioral relationship. We treat ATT&CK as a framework for organizing defensible reasoning, not as a taxonomy for classification. In all cases, the associations are non-exclusive and uncertainty-aware: multiple tactics may remain plausible for a given artifact, and absence of evidence is not treated as evidence of absence.

ATT&CK serves as a structured vocabulary for expressing what can reasonably be supported by available evidence, rather than as a taxonomy for detection or classification.

3.5. D3FEND-Based Defensive Reasoning

For each artifact and its associated tactic-level support relationships, we identify relevant defensive technique categories from the MITRE D3FEND framework. D3FEND is employed to reason about defensive applicability (which techniques remain actionable given available evidence) rather than defensive effectiveness or deployment status.

We map artifacts to D3FEND technique categories based on the observable evidence requirements of each technique group, identifying which defensive controls remain logically relevant given the surviving network evidence. The defensive technique categories referenced in our analysis (network traffic analysis, behavioral monitoring, rate limiting, traffic filtering, flow-based monitoring, connection throttling, and protocol analysis) represent our grouping of D3FEND techniques based on shared evidence requirements, aligned with but not necessarily identical to the official D3FEND taxonomy. These mappings are based on the evidence requirements documented in the D3FEND knowledge base [

40]. No claims are made regarding the operational presence, performance, or evaluation of these controls.

3.6. Inference Chain Collapse Analysis

The final step of our approach analyzes how the inference chain degrades as evidence is reduced. By comparing artifact visibility and support relationships across packet-level, flow-level, and time-aggregated representations, we identify where defensible reasoning collapses from artifact-supported tactic hypotheses to non-specific or non-actionable observations.

This analysis allows us to characterize evidence loss not merely as loss of data volume or resolution, but as a loss of inferential power within structured threat reasoning frameworks. The result is a qualitative but systematic assessment of which forensic conclusions remain defensible under modern network monitoring constraints.

3.7. Safeguards Against Subjective Attribution

A central methodological risk in forensic analysis of unlabeled network traffic is the introduction of subjective or non-reproducible attribution, particularly when higher-level threat frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK are involved. We avoid performing tactic inference or defining new artifact-to-tactic rules. Instead, ATT&CK is used as a reference taxonomy to organize and evaluate the stability of forensic attributions that have already been established in prior literature.

All associations between observed network artifacts and ATT&CK tactics are grounded exclusively in previously published sources, including official ATT&CK behavioral descriptions, detection guidance, and well-established network forensics literature. The analysis does not assert that a given artifact implies a specific adversarial tactic. Rather, it examines whether artifacts that have been previously cited as supporting tactic-level interpretation remain observable and defensible under different evidence representations. As such, attribution is treated as a documented association, not as a classification decision made by the authors.

To further reduce interpretive bias, the analysis is restricted to the ATT&CK tactic level. Technique-level attribution is avoided, as it would require assumptions about host context, payload visibility, or attacker intent that are not available in backbone traffic traces. Tactics are used solely as coarse-grained intent categories that allow comparison of support relationship stability across evidence representations.

This study does not assume the availability of ground truth labels, nor does it attempt to validate the correctness of any individual attribution. The objective is not to determine whether a specific tactic occurred, but to analyze how the defensibility of commonly cited forensic interpretations degrades as evidence is transformed from packet-level traces to flow-level and time-aggregated representations. Consequently, the analysis focuses on relative loss of defensible support relationships rather than absolute correctness.

Where illustrative context is required, the analysis refers to canonical network behaviors (e.g., scanning, flooding, periodic communication) that are widely recognized in the literature and frequently used as reference cases in network forensics. These scenarios are not treated as confirmed attacks but as conceptual anchors that enable structured comparison of how their observable artifacts survive or collapse under evidence degradation.

All artifact definitions, evidence transformations, and attribution references are explicitly documented to ensure reproducibility. Because the methodology relies on published descriptions and observable properties rather than expert judgment or heuristic rule construction, independent analysts can replicate the analysis using the same data sources and reference materials.

By constraining attribution to literature-backed associations, restricting analysis to coarse-grained intent categories, and reframing reasoning as a question of evidential stability rather than detection accuracy, the proposed methodology minimizes subjectivity while remaining faithful to the realities of forensic analysis under partial observability.

4. Results

We evaluate how monitoring abstraction changes the

availability of network-forensic artifacts and, consequently, the

supportability of higher-level threat reasoning under the audit framework. Using three 15-minute backbone traffic windows from MAWI DITL [

8] (April 9, 2025; 00:00, 06:00, 12:00), we compare three evidence representations: packet-level (L0), flow-level (L1), and time-aggregated flows (L2). Our evaluation assesses how evidence reduction constrains the space of supportable threat hypotheses from network observations given the available evidence representation. This is a

structural analysis of representational constraints, not a statistical measurement of traffic behavior. We evaluate representational survivability of literature-grounded support relationships, not correctness of adversary hypotheses.

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

We evaluated three 15-minute traffic windows from the MAWI DITL [

8] backbone trace captured on April 9, 2025, at 00:00, 06:00, and 12:00. These windows were selected to provide temporal separation while keeping the pipeline computationally reproducible under realistic resource constraints. While artifact computability is definitionally determined by the representation (L0/L1/L2), real backbone traffic provides essential validation: (i) it confirms that artifact definitions are computable under realistic data volumes and formats (e.g., handling IPv4/IPv6, fragmented packets, and flow timeout boundaries), (ii) it reveals distributional properties of artifacts (e.g., prevalence of SYN-dominant patterns, typical fan-out ranges) that inform practical audit interpretation, and (iii) it demonstrates that the audit procedure remains stable across diverse traffic compositions (night, morning, noon windows), indicating representation-driven rather than traffic-driven effects. This empirical validation is necessary because the audit framework must operate on real telemetry exports, not just theoretical definitions. While MAWI is not representative of all backbone environments, the audit framework is agnostic to traffic source and applies to any telemetry pipeline exporting equivalent representations (packet headers, flow records, or time-aggregated statistics).

4.1.1. Software Tools and Configuration

For reproducibility, we document the complete software toolchain and configuration parameters. L0 packet extraction uses YAF [

41] (Yet Another Flowmeter) version 2.14.0 to extract packet header fields and timestamps from PCAP files without payload access. YAF serves as both a flow meter and a packet header parser, reading packet headers directly from PCAP files. L1 flow generation uses YAF version 2.14.0 [

41], configured with default flow timeout settings (active timeout: 60 seconds, idle timeout: 15 seconds) and 5-tuple flow key (source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, protocol). YAF is invoked via command-line:

yaf –in <input.pcap> –out <output.yaf>, which generates IPFIX-compliant flow records. YAF’s binary IPFIX output is converted to tabular format using

yafscii (included with YAF distribution). L2 aggregation is performed using Python pandas (version 1.5.3) with fixed temporal bins (1s, 10s, 60s). All artifact computation scripts are implemented in Python 3.10+ using pandas (1.5.3), numpy (1.24.3), and standard libraries. The complete pipeline, including artifact computation, survivability analysis, and metric generation, is available as supplementary material. Computational environment: macOS 14.x, Python 3.10, 16GB RAM. Processing time per 15-minute window: L0 extraction 15 minutes, L1 flow generation 45 minutes, L2 aggregation 5 minutes, artifact computation 10 minutes.

For each window, we evaluated three evidence representations:

For comparability across layers, L0 and L1 artifact computation uses 1-second binning (using packet timestamps at L0 and flow start times at L1). Protocol share at L1 is computed as the fraction of flows per protocol within each 1-second bin using the protocol field from YAF’s IPFIX export schema. This temporal binning enables consistent computation of time-dependent artifacts such as protocol share and rate spikes across all three layers, though the L1 computation represents an approximation based on flow-level aggregation rather than direct packet counting.

The analysis processed gzip-compressed PCAP files of 4.6 GB, 2.7 GB, and 6.6 GB for the 00:00, 06:00, and 12:00 windows respectively, totaling 13.9 GB of compressed network traffic.

1

We compute a catalog of 13 network-forensic artifacts (

Table 3). Each artifact is defined operationally (i.e., exact computable function over L0/L1/L2).

Table 2 provides a compact excerpt of artifact-to-tactic mappings with representative citations; the complete artifact catalog with all literature-grounded tactic-support and D3FEND-applicability references is provided in

Appendix A and available in the supplementary materials, where each association is accompanied by its source citation. The defensive technique categories referenced in our analysis (network traffic analysis, behavioral monitoring, rate limiting, traffic filtering, flow-based monitoring, connection throttling, and protocol analysis) represent our grouping of D3FEND techniques based on shared evidence requirements, aligned with the D3FEND knowledge base [

40].

4.2. Artifact Survivability Across Layers

Table 3 reports whether each artifact is computable in each evidence layer. Timing-sensitive artifacts (inter-arrival burstiness, inter-packet timing) are available only in packet-level evidence (L0), while flow-specific artifacts (duration distribution, directional asymmetry) emerge at L1 and persist at L2. Protocol distribution imbalance and ICMP protocol share are defined as

protocol share per time bin (the fraction of flows or packets per protocol within each temporal bin), making them computable at all three layers. ICMP share is included because ICMP traffic patterns can indicate reconnaissance or network discovery activities, and protocol-level statistics remain observable even under aggregation.

Table 3.

Artifact computability across evidence layers. A checkmark indicates the artifact can be computed from that representation under our pipeline.

Table 3.

Artifact computability across evidence layers. A checkmark indicates the artifact can be computed from that representation under our pipeline.

| Artifact |

L0 |

L1 |

L2 |

| Inter-arrival Time Burstiness |

|

× |

× |

| Inter-packet Timing Patterns |

|

× |

× |

| SYN-Dominant Connection Bursts |

|

|

|

| Packet Rate Spikes |

|

|

|

| Byte Rate Spikes |

|

|

|

| Destination Fan-out |

|

|

× |

| Temporal Periodicity (entity-linked) |

|

|

× |

| Aggregate Temporal Periodicity (bin-level) |

|

|

|

| Flow Duration Distribution |

× |

|

|

| Directional Traffic Asymmetry |

× |

|

|

| Short-Lived Flow Patterns |

× |

|

|

| Protocol Distribution Imbalance |

|

|

|

| ICMP Protocol Share |

|

|

|

The table reveals three distinct artifact categories: (1) packet-level timing artifacts (inter-arrival burstiness, inter-packet timing) that are completely lost in flow-based representations, (2) flow-specific artifacts (duration distribution, directional asymmetry, short-lived flows) that emerge only at L1 and persist at L2, and (3) artifacts that remain stable across all layers (rate spikes, SYN patterns, protocol statistics). The loss of destination fan-out at L2 reflects a modeling decision representing common operational practice: coarse telemetry exports aggregate counts and rates per time bin but do not preserve per-entity adjacency structures (e.g., source→set(destinations)). This design choice models realistic monitoring abstractions where storage and processing constraints favor aggregate statistics over per-entity keyed structures. Protocol-level statistics remain computable at all layers due to their per-time-bin definition, computed by aggregating flows per protocol within each 1-second bin.

Clarification on periodicity and Persistence. While aggregate temporal periodicity (bin-level time-series periodicity, e.g., periodic variation in total flow counts) remains computable at L2, the entity-linked periodicity required to support a Persistence hypothesis (e.g., a specific host exhibiting recurring beacon-like communication) is not computable when L2 aggregation discards per-entity keys (source/destination identifiers). Therefore, Persistence loses defensible support at L2 despite the continued availability of aggregate periodicity.

4.3. Inference Chain Collapse

We characterize reasoning degradation using two structural metrics: inference coverage (), the number of ATT&CK tactics supported by at least one computable artifact in layer L (based on literature-grounded artifact-to-tactic associations), and defensive applicability (), the number of D3FEND technique categories whose required observable inputs are available in layer L. These metrics are structural counts that assess representational constraints, not statistical measurements of traffic behavior. We use inference chain collapse to denote the overall phenomenon, and degradation to refer to the stepwise loss of inferential power across L0→L1→L2.

Table 3 (

Section 4) establishes which artifacts are computable at each layer.

Table 4 then shows how artifact loss translates to tactic-level inference loss: the

Execution tactic loses support at L1 because its supporting artifacts (inter-arrival time burstiness, inter-packet timing) require packet-level timing information that is not computable from flow records. The

Lateral Movement and

Persistence tactics lose support at L2 because their supporting artifacts (destination fan-out, entity-linked temporal periodicity) require per-entity structural information that is removed by temporal aggregation.

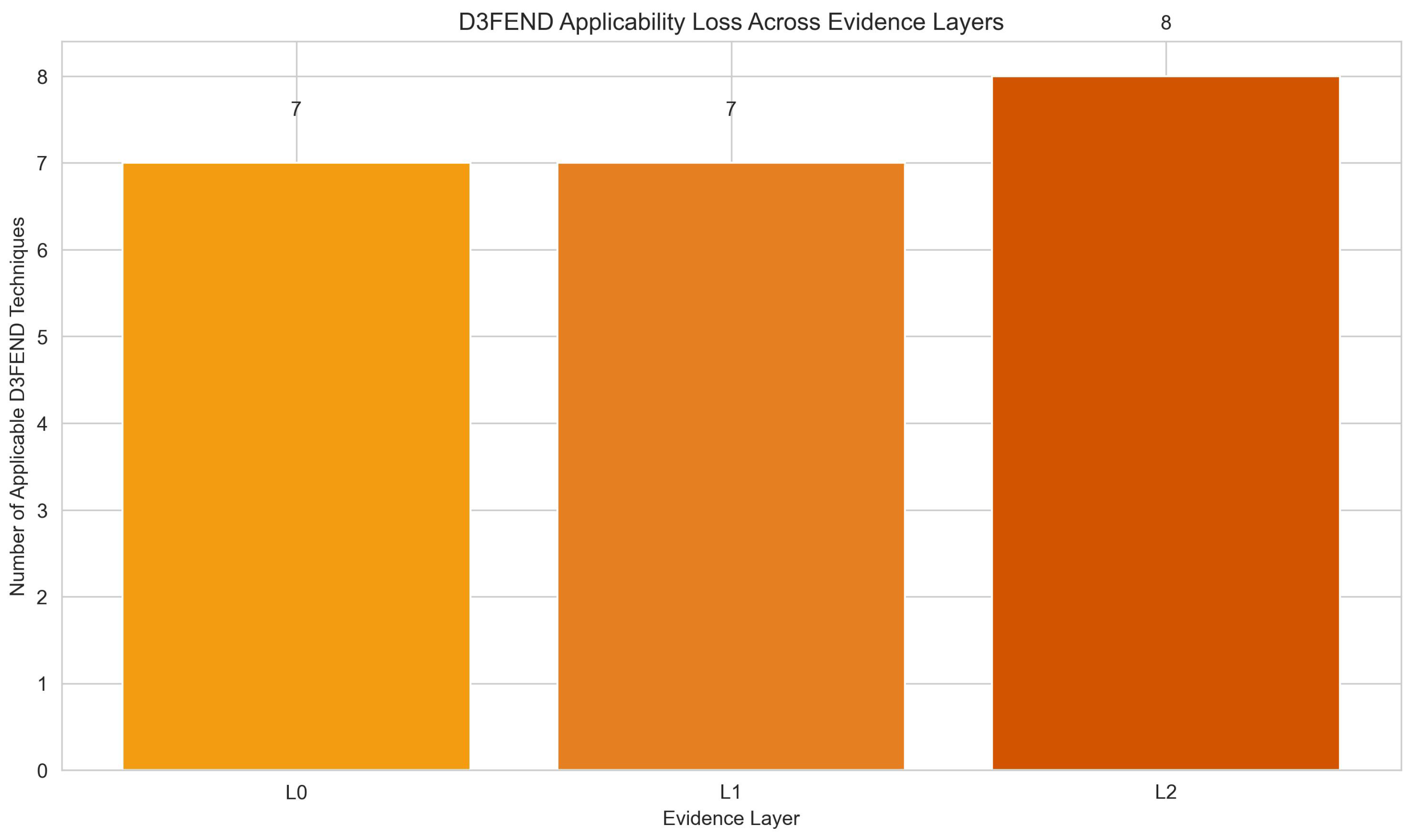

Table 5 completes the chain by showing how artifact loss affects defensive applicability:

Anomaly Detection becomes non-applicable at L2 because it requires per-entity structural information, while

Flow-based Monitoring becomes applicable at L1 once flow records are available.

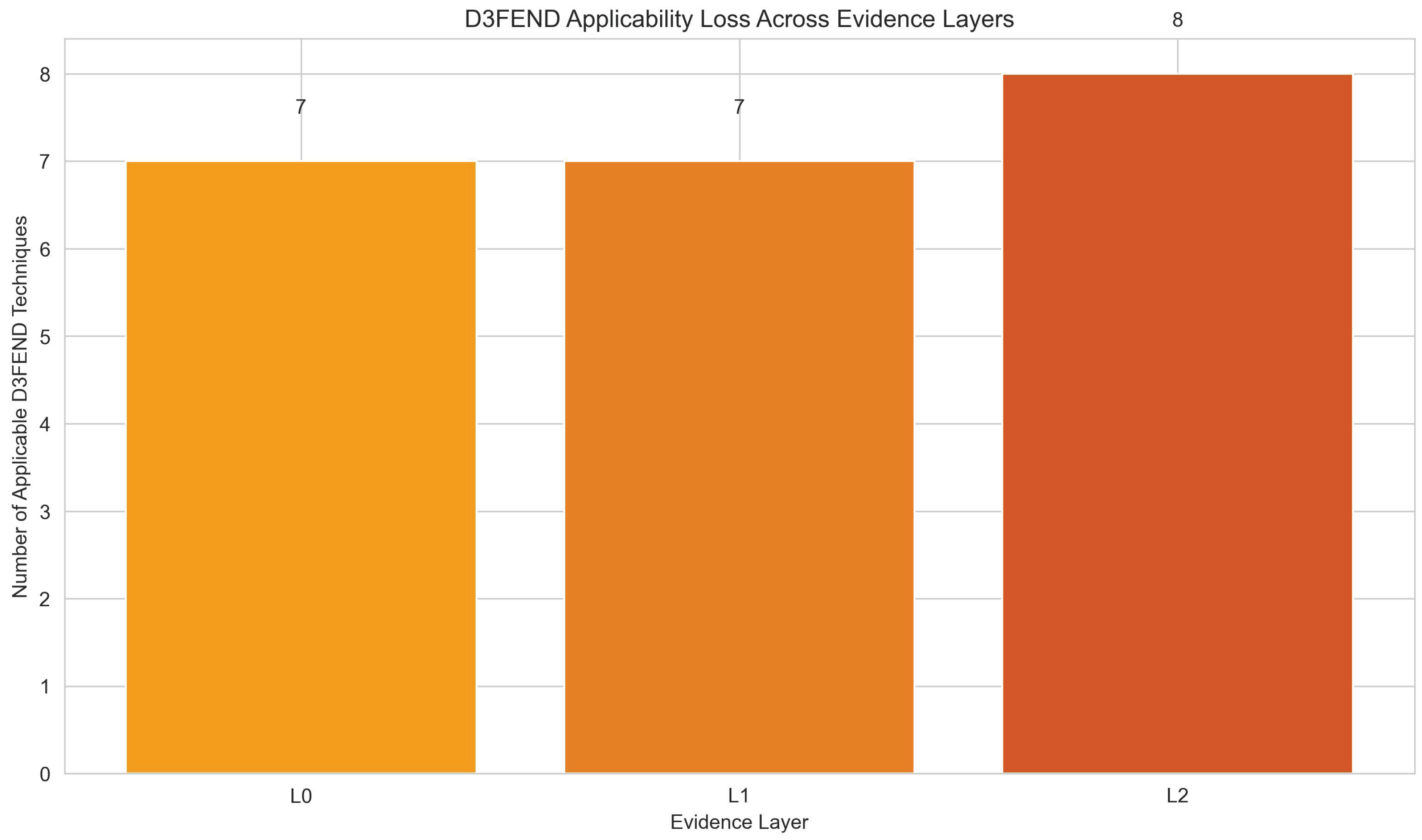

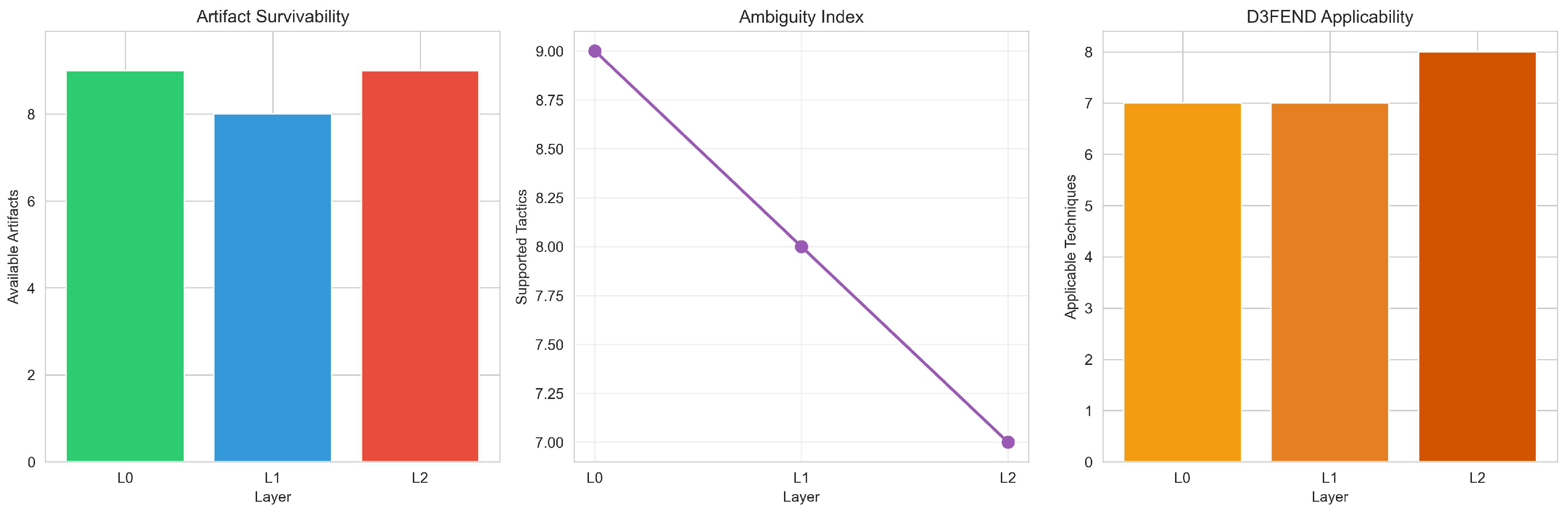

While individual losses may appear intuitive in isolation (e.g., flows remove packet timing, aggregation removes entity structure), their compound effect on tactic-level inference and defensive applicability has not been systematically evaluated. The audit reveals that evidence abstraction reduces inference coverage from 9 (L0) to 7 (L2) tactics, while D3FEND applicability increases from 7 (L0) to 8 (L1) and then decreases to 7 (L2), reflecting a shift from entity-aware anomaly reasoning to flow-based defensive techniques under aggregation.

The increase in available artifacts at L1 (10 → 11) reflects the emergence of flow-specific properties (e.g., flow duration distribution, directional asymmetry, short-lived flow patterns) that are not definable at the packet level, partially compensating for the loss of fine-grained timing information. Despite this quantitative increase, inference coverage decreases monotonically (9 → 8 → 7), demonstrating that artifact quantity does not directly translate to inferential discriminability. The increase in D3FEND applicability at L1 (7 → 8) is explained by the emergence of Flow-based Monitoring, which becomes applicable once flow records are available. The decrease at L2 (8 → 7) reflects the loss of Anomaly Detection, which requires per-entity structural information that is removed by temporal aggregation. This shift represents a transformation from packet-level behavioral monitoring (requiring fine-grained timing) to flow-based defensive techniques (requiring aggregate flow statistics).

Table 5 shows D3FEND defensive technique categories applicable at each layer. The increase in applicability at L1 (7 → 8) is explained by the emergence of

Flow-based Monitoring, which becomes enabled at L1 (requiring flow records), while

Anomaly Detection is disabled at L2 (requires per-entity structural information). This shift represents a transformation from behavioral monitoring (requiring fine-grained timing) to rate/flow-based controls (requiring aggregate statistics), reflecting the operational constraints of coarse telemetry systems.

4.4. Stability Across Time Windows

The audit procedure produces consistent collapse patterns across all three time windows (00:00, 06:00, 12:00), with identical metrics at each layer: 10/11/9 artifacts, 9/8/7 tactics, and 7/8/7 D3FEND categories. This invariance indicates that evidence-loss effects are structural properties of monitoring abstractions rather than artifacts of specific traffic characteristics. While the underlying artifact values (e.g., rates and protocol proportions) vary across windows, the computability pattern and the resulting coverage/applicability metrics remain invariant, indicating a representation-driven rather than traffic-driven effect. This consistency across diverse time periods (night, morning, noon) indicates that the audit framework produces stable results across the evaluated traffic conditions, supporting its use as an evaluation tool. Extended visualizations demonstrating this invariance across all three windows are provided in

Appendix B.

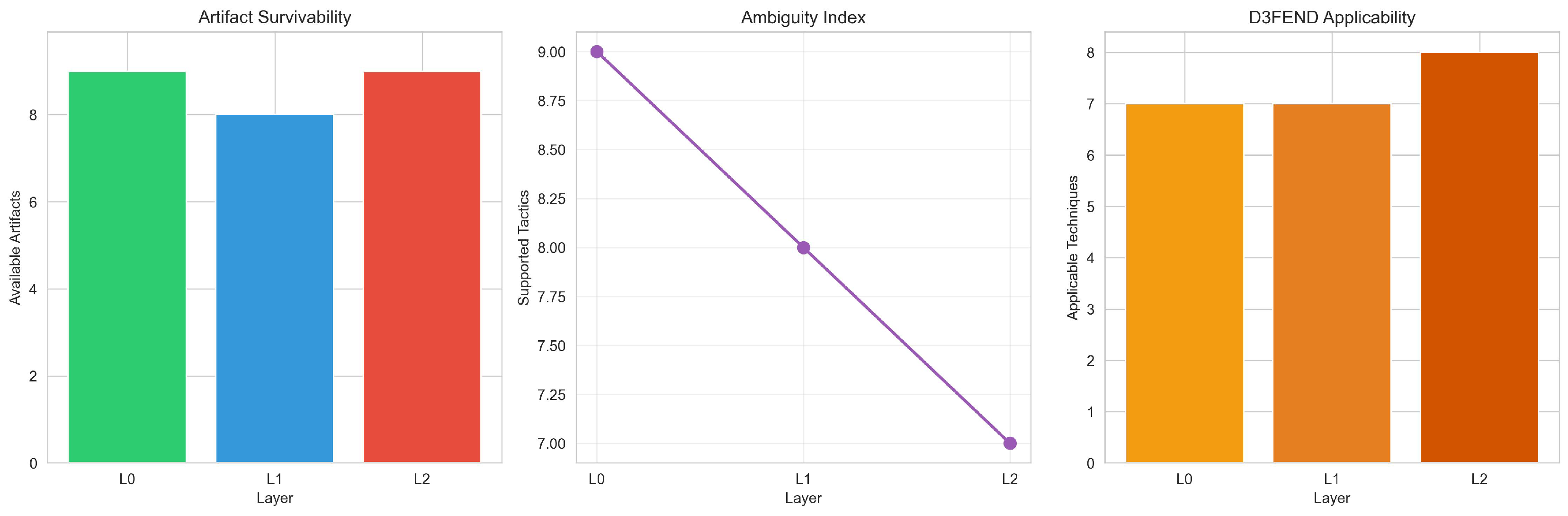

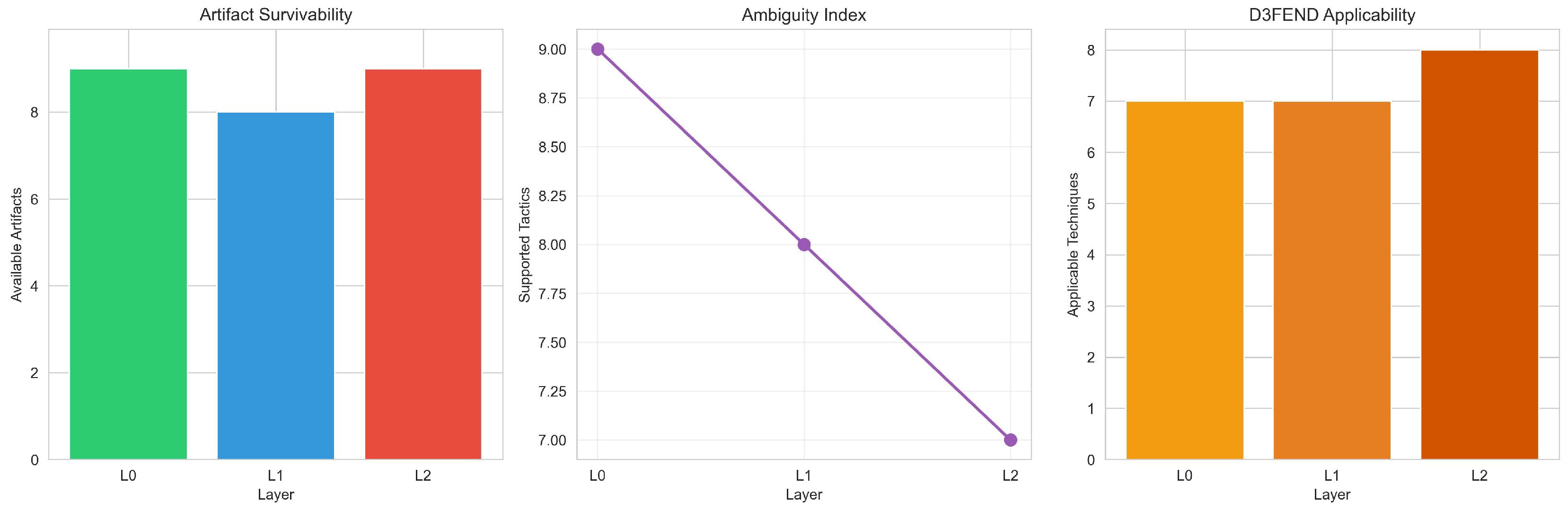

Figure 2 provides a visual synthesis of the key collapse metrics for practitioners, combining artifact survivability, inference coverage, and D3FEND applicability into a single view to emphasize their non-monotonic and divergent behavior. This synthesis highlights that evidence abstraction does not produce uniform degradation: artifact count increases at L1 while inference coverage decreases, and D3FEND applicability follows a distinct trajectory from both metrics.

4.5. Scenario-Based Demonstration

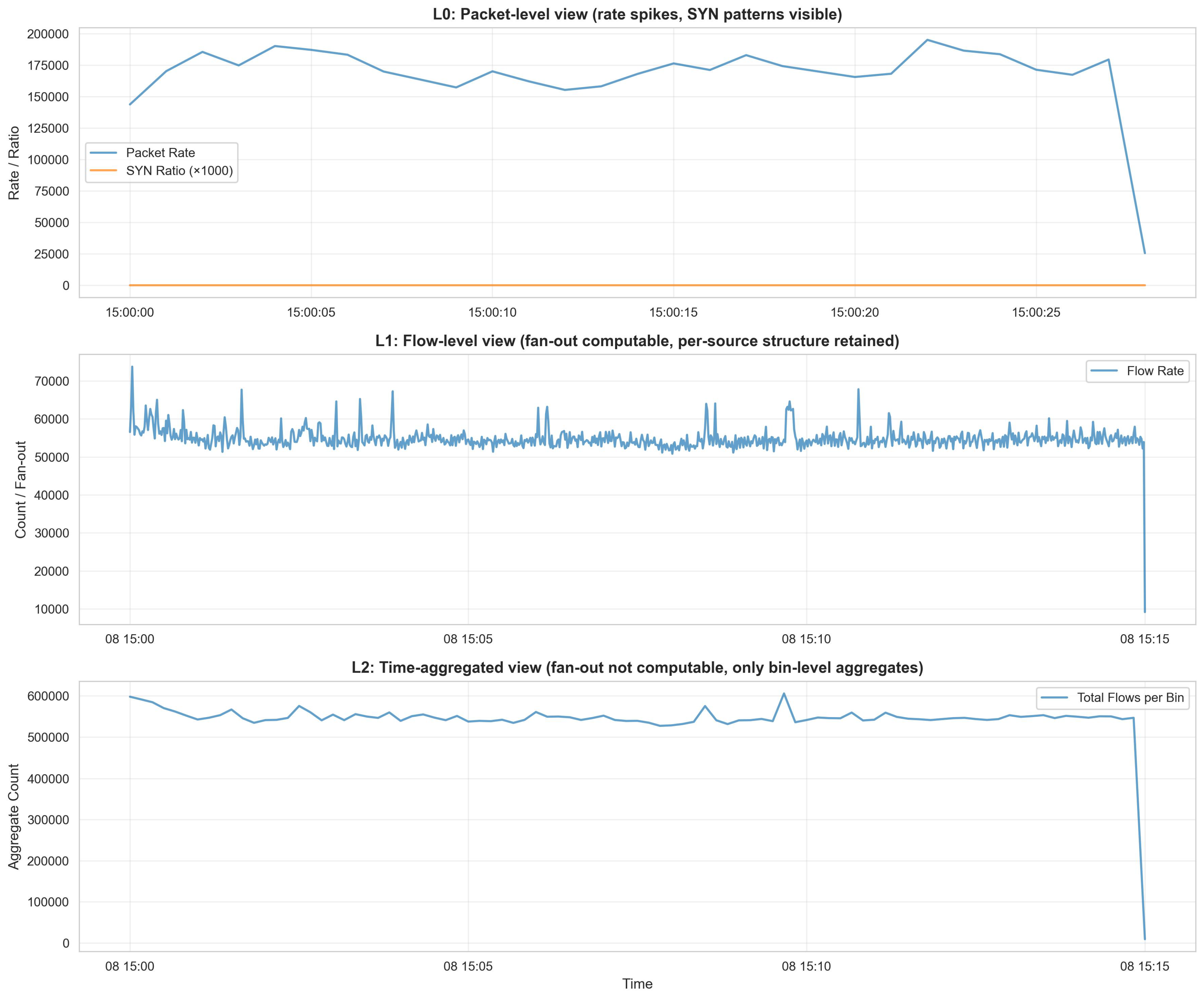

To concretely demonstrate how evidence abstraction creates ambiguity, we trace a canonical network behavior—port-scan-like patterns characterized by high destination fan-out, SYN-dominant connections, and short-lived flows—through each evidence layer. For the scenario trace, we selected a short sub-interval within the 15-minute window exhibiting an extreme tail in (i) per-source destination fan-out and (ii) SYN-dominant, short-lived connection patterns, as measured by our artifact definitions; this selection is used solely to illustrate representation-driven evidence loss and does not constitute attack attribution.

Figure 3 visualizes the 15-minute window with the selected sub-interval highlighted, showing the same time period across L0, L1, and L2 representations.

At L0 (packet-level), a responder can observe fine-grained timing patterns (inter-packet intervals, burst dynamics) and flag-level detail (SYN ratios), enabling support for Reconnaissance, Discovery, and Initial Access tactics with high evidential strength. At L1 (flow-level), destination fan-out becomes directly computable per source, preserving the ability to support Lateral Movement inference while losing packet-level timing texture. At L2 (time-aggregated), destination fan-out is no longer computable because temporal aggregation removes per-source keyed structure; only bin-level aggregate counts (total flows, rates) remain. This collapse eliminates support for Lateral Movement while preserving support for Reconnaissance and Discovery via SYN patterns and protocol statistics.

This scenario directly illustrates the logical progression from

Table 3 to

Table 4: the loss of destination fan-out at L2 (

Table 3) eliminates support for

Lateral Movement (

Table 4), demonstrating that the “9 → 7 tactics” reduction is not uniform. Some tactics (e.g.,

Lateral Movement) become completely non-supportable at L2, while others (e.g.,

Reconnaissance) remain supportable but with reduced evidential strength due to loss of structural detail.

5. Implications for Practice

The audit results indicate that evidence abstraction creates selective blind spots rather than uniform degradation. The 22% reduction in inference coverage (9 → 7 tactics) constrains the space of supportable tactic hypotheses. This section translates these findings into actionable guidance for three key audiences.

5.1. For Network Architects

When evaluating a telemetry system, architects should ask: (1) Does it preserve source-destination pairs per time bin (required for Lateral Movement analysis via destination fan-out)? (2) Can we derive inter-packet timing from the exported data (required for Execution analysis)? (3) Are per-entity temporal patterns preserved, or only aggregate statistics (required for Persistence analysis)? The audit procedure provides a systematic method to answer these questions: given a telemetry schema, it identifies which artifacts remain computable and, consequently, which threat hypotheses can be supported.

For IPFIX extensions and programmable data plane telemetry, architects should prioritize preserving artifacts that enable high-value threat hypotheses. Our results suggest that preserving source-destination pairs (enabling destination fan-out) and inter-packet timing (enabling execution inference) should be prioritized over aggregate-only statistics. For example, if a system exports only time-aggregated flow counts per protocol (L2), destination fan-out is not computable, and Lateral Movement hypotheses cannot be supported regardless of how suspicious aggregate statistics appear. Architects should document not only what data is collected, but which classes of forensic inference remain supportable under the audit framework.

5.2. For Incident Responders

If a playbook for investigating lateral movement requires analyzing destination fan-out, but archived data is time-aggregated (L2), that playbook step cannot be executed. Playbooks must be aligned with evidence availability. Specifically, if an organization relies on L2 telemetry (time-aggregated flows), claims that observed patterns support Execution (requires packet timing), Lateral Movement (requires destination fan-out), or Persistence (requires temporal periodicity with per-entity structure) hypotheses cannot be supported when only aggregated telemetry is available.

The defensive posture shifts from behavioral monitoring (requiring fine-grained timing) to rate/flow-based controls (requiring aggregate statistics). Incident response procedures must reflect these constraints: playbooks that require evidence types no longer available in archived telemetry cannot be executed given the available evidence. Organizations should align defensive strategies with monitoring capabilities rather than assuming that “more data” always improves security posture.

5.3. For Tool Developers

Tools could integrate this audit by generating a “forensic coverage report” alongside system deployment. Such a report would map the telemetry schema to supportable ATT&CK tactics and applicable D3FEND categories, enabling operators to understand the forensic capabilities of their monitoring infrastructure before incidents occur. The audit procedure can be automated: given a telemetry schema specification (e.g., IPFIX template, P4 telemetry export format), it outputs which artifacts are computable, which tactics remain supportable, and which defensive techniques are applicable. This enables proactive telemetry design: operators can evaluate multiple schema options and select configurations that preserve required forensic capabilities while meeting bandwidth and storage constraints. Integration with SDN controllers could enable dynamic telemetry adjustment: when threat intelligence indicates increased risk of lateral movement, the controller could temporarily increase export granularity to preserve destination fan-out artifacts.

In summary, network engineers can use this audit framework to make concrete design decisions: when configuring IPFIX exporters, they can determine which fields (e.g., flowStartMilliseconds, source-destination pairs) must be preserved to support specific threat hypotheses; when designing P4 telemetry pipelines, they can identify the minimal export schema that maintains required forensic coverage; and when evaluating monitoring architectures, they can assess trade-offs between scalability and inferential capability before deployment.

6. Discussion

The audit results reveal a non-monotonic transformation of defensive capabilities under evidence abstraction: D3FEND applicability increases at L1 (7→8) before decreasing at L2 (8→7), while inference coverage decreases monotonically (9→8→7). This non-monotonicity has important implications for network monitoring architecture design. Rather than viewing abstraction as uniformly degrading forensic capability, network architects should recognize that different abstraction levels enable different classes of defensive reasoning.

6.1. Design Principles for Hybrid Monitoring Systems

The increase in D3FEND applicability at L1 reflects the emergence of Flow-based Monitoring, which becomes actionable once flow records are available. This suggests that hybrid monitoring systems—combining selective packet capture with flow export—may optimize forensic coverage while maintaining scalability. For example, an SDN controller might dynamically adjust telemetry granularity: maintaining flow records for broad coverage while selectively enabling packet-level capture for specific flows exhibiting suspicious patterns (e.g., high destination fan-out). Our artifact catalog provides a principled basis for such adaptive telemetry: artifacts that require packet timing (e.g., inter-arrival burstiness) would trigger selective packet capture, while artifacts computable from flows (e.g., destination fan-out) would rely on flow export.

6.2. Implications for Programmable Data Plane Telemetry

Next-generation programmable data planes (e.g., P4 programming language, extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF)) enable fine-grained control over telemetry export. Our artifact catalog directly informs what to measure: preserving source-destination pairs per time bin enables Lateral Movement inference, while maintaining inter-packet timing enables Execution inference. Rather than exporting all possible metrics, operators can use the audit framework to identify the minimal telemetry schema that preserves support for specific threat hypotheses.

For instance, to preserve Lateral Movement inference in a P4 switch, our audit dictates exporting the sourceIP-destinationIP matrix per time bin, not just aggregate counters. Similarly, for IPFIX template design, operators must include flowStartMilliseconds and flowEndMilliseconds fields (rather than only aggregate byte/packet counts) to enable inter-packet timing reconstruction for Execution inference. This is particularly relevant for IPFIX extensions and custom telemetry formats, where operators must balance export bandwidth against forensic utility.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

This study intentionally focused on backbone-level passive observation without payload visibility, endpoint context, or ground truth. While this reflects common operational constraints, several limitations warrant future investigation. First, the artifact catalog is currently static; future work could develop adaptive artifact definitions that adjust based on traffic characteristics or threat intelligence. Second, the analysis assumes deterministic artifact computation; in practice, measurement noise, sampling, and flow timeout variations introduce uncertainty that should be quantified. Third, the framework evaluates artifact computability but not evidential strength; future work could develop probabilistic models that quantify confidence in tactic support given noisy or partial observations.

Integration with SDN controllers proposes a potential extension: the audit framework might be embedded as a telemetry policy engine, dynamically adjusting export granularity based on current threat landscape and available computational resources. Similarly, the artifact catalog might inform the design of intelligent telemetry sampling algorithms for ISP backbones, where operators must balance forensic coverage against export bandwidth constraints.

7. Conclusions

We developed a design-time audit tool that identifies how progressively abstracted network evidence alters the set of threat hypotheses and defensive actions that can be logically supported. Using backbone traffic from MAWI DITL [

8] (2025) and a literature-grounded inference framework, the audit procedure revealed that evidence abstraction produces

selective and structural inference loss. Packet-level timing artifacts required to support

Execution hypotheses disappear once monitoring collapses to flows, while entity-linked structural artifacts such as destination fan-out and host-specific periodicity are lost under time-aggregated telemetry, eliminating supportable claims for

Lateral Movement and

Persistence. In contrast, tactics such as

Reconnaissance,

Discovery, and

Command and Control remain supportable across all representations, albeit with reduced evidential strength.

The audit further revealed that defensive reasoning does not degrade monotonically with abstraction. Instead, abstraction transforms the supportable defensive toolkit. Flow export enables flow-based monitoring capabilities, while coarse aggregation disables entity-aware anomaly detection and behavioral analysis. This shift reflects a transition from fine-grained behavioral reasoning to rate- and flow-based control strategies, rather than a uniform loss of defensive capability.

A scenario-based trace of scan-like behavior concretely illustrated how this inference chain collapse manifests in practice. The same network activity supports different sets of threat hypotheses depending solely on the evidence representation, highlighting that monitoring design choices directly bound the claims that can be supported given the available evidence representation.

The audit framework provides organizations with a method to evaluate their telemetry architectures. Organizations should align their incident response playbooks, forensic reporting practices, and defensive expectations with the abstraction level of their network telemetry. Claims about adversary behavior that require packet timing or entity-linked structure are not supportable when monitoring systems export only aggregated flow statistics. Monitoring architectures should therefore document not only what data is collected, but which classes of forensic inference remain supportable under the audit framework.

This study intentionally focused on backbone-level passive observation without payload visibility, endpoint context, or ground truth. While this reflects common operational constraints, future work could extend the analysis to hybrid telemetry environments that combine flow data with selective packet capture, endpoint logs, or encrypted traffic features. Assessing evidential strength under adversarial traffic injection and evaluating inference stability under adaptive attackers also remain open research directions.

In summary, this work provides an audit methodology that reframes evidence reduction not as a loss of data volume, but as a loss of inferential options. The framework enables organizations to evaluate which forensic claims remain supportable under their chosen telemetry architecture, which is essential for designing monitoring systems, qualifying forensic conclusions, and maintaining analytical rigor in modern network security operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.; methodology, M.V. and S.J.; software, M.V.; validation, S.J. and H.N.; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, M.V.; resources, M.V.; data curation, M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.; writing—review and editing, S.J. and H.N.; visualization, M.V.; supervision, S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI-assisted tools for language proficiency and text editing purposes only. All ideas, technical content, analysis, methodology, and research contributions are the original work of the authors. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-assisted output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATT&CK |

Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge |

| D3FEND |

Detection, Denial, and Disruption Framework Emulating Network Defense |

| IPFIX |

IP Flow Information Export |

| ISP |

Internet Service Provider |

| PCAP |

Packet Capture |

| SOC |

Security Operations Center |

| IR |

Incident Response |

| SDN |

Software-Defined Networking |

| DDoS |

Distributed Denial of Service |

| NIDS |

Network Intrusion Detection System |

| TLS |

Transport Layer Security |

| DITL |

Day-In-The-Life |

| YAF |

Yet Another Flowmeter |

Appendix A. Artifact Catalog

The complete artifact catalog documents all 13 network-forensic artifacts, their computability across evidence layers (L0, L1, L2), associated ATT&CK tactic-level support relationships, and enabling D3FEND defensive technique categories. Each artifact-to-tactic association is grounded in published literature, with source citations provided. This catalog serves as the reference for all survivability and applicability analyses reported in the main text.

Table A1 provides the complete mapping. Artifacts are defined operationally (exact computable functions) to ensure reproducibility. The “Available In” column indicates which evidence layers support artifact computation, while “Supports Tactics” lists ATT&CK tactics for which published sources describe consistent network-visible behavioral relationships. “Enables D3FEND” identifies defensive technique categories that become actionable when the artifact is observable.

Table A1.

Complete artifact catalog with literature-grounded associations. Each artifact is operationally defined and mapped to ATT&CK tactics and D3FEND categories based on published sources.

Table A1.

Complete artifact catalog with literature-grounded associations. Each artifact is operationally defined and mapped to ATT&CK tactics and D3FEND categories based on published sources.

| Artifact |

Available In |

Supports Tactics |

Enables D3FEND |

| Inter-arrival Time Burstiness |

L0 |

Execution, Command and Control |

Behavioral Monitoring |

| Inter-packet Timing Patterns |

L0 |

Execution, Command and Control |

Behavioral Monitoring |

| SYN-Dominant Connection Bursts |

L0, L1, L2 |

Reconnaissance, Initial Access, Discovery |

Connection Throttling, Traffic Filtering |

| Packet Rate Spikes |

L0, L1, L2 |

Execution, Impact, Command and Control |

Rate Limiting, Traffic Filtering |

| Byte Rate Spikes |

L0, L1, L2 |

Exfiltration, Impact |

Rate Limiting, Traffic Filtering |

| Destination Fan-out |

L0, L1 |

Lateral Movement, Discovery |

Network Traffic Analysis |

| Temporal Periodicity (entity-linked) |

L0, L1 |

Persistence, Command and Control |

Anomaly Detection, Behavioral Monitoring |

| Aggregate Temporal Periodicity |

L0, L1, L2 |

Command and Control |

Behavioral Monitoring |

| Flow Duration Distribution |

L1, L2 |

Execution, Discovery |

Flow-based Monitoring |

| Directional Traffic Asymmetry |

L1, L2 |

Exfiltration, Lateral Movement |

Network Traffic Analysis |

| Short-Lived Flow Patterns |

L1, L2 |

Reconnaissance, Discovery |

Flow-based Monitoring |

| Protocol Distribution Imbalance |

L0, L1, L2 |

Execution, Discovery |

Protocol Analysis |

| ICMP Protocol Share |

L0, L1, L2 |

Discovery, Reconnaissance |

Protocol Analysis |

Appendix B. Stability Across Time Windows

Section 4 reports that the audit procedure produces consistent collapse patterns across all three time windows (00:00, 06:00, 12:00), with identical metrics at each layer. This appendix provides extended visualizations demonstrating this invariance.

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 show the collapse metrics for the 06:00 and 12:00 windows, respectively. These figures replicate the structure of

Figure 2 (main text, 00:00 window) and confirm that the non-monotonic transformation pattern—artifact count increase at L1, monotonic inference coverage decrease, and D3FEND applicability transformation—is consistent across diverse traffic conditions.

Figure A1.

Collapse metrics for the 06:00 time window, replicating the analysis shown in

Figure 2 (main text). The identical pattern (10/11/9 artifacts, 9/8/7 tactics, 7/8/7 D3FEND categories) confirms that evidence-loss effects are structural properties of monitoring abstractions rather than artifacts of specific traffic characteristics.

Figure A1.

Collapse metrics for the 06:00 time window, replicating the analysis shown in

Figure 2 (main text). The identical pattern (10/11/9 artifacts, 9/8/7 tactics, 7/8/7 D3FEND categories) confirms that evidence-loss effects are structural properties of monitoring abstractions rather than artifacts of specific traffic characteristics.

Figure A2.

Collapse metrics for the 12:00 time window, again showing identical patterns to the 00:00 and 06:00 windows. This consistency across night (00:00), morning (06:00), and noon (12:00) periods indicates that the audit framework produces stable results across the evaluated traffic conditions.

Figure A2.

Collapse metrics for the 12:00 time window, again showing identical patterns to the 00:00 and 06:00 windows. This consistency across night (00:00), morning (06:00), and noon (12:00) periods indicates that the audit framework produces stable results across the evaluated traffic conditions.

Appendix C. Extended Illustrative Outputs

This section provides additional visualizations that instantiate the artifact survivability, inference coverage (ambiguity index), and D3FEND applicability metrics across all three time windows. These figures extend the tabular results reported in the main text (

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5) by showing the layer-by-layer progression for each metric.

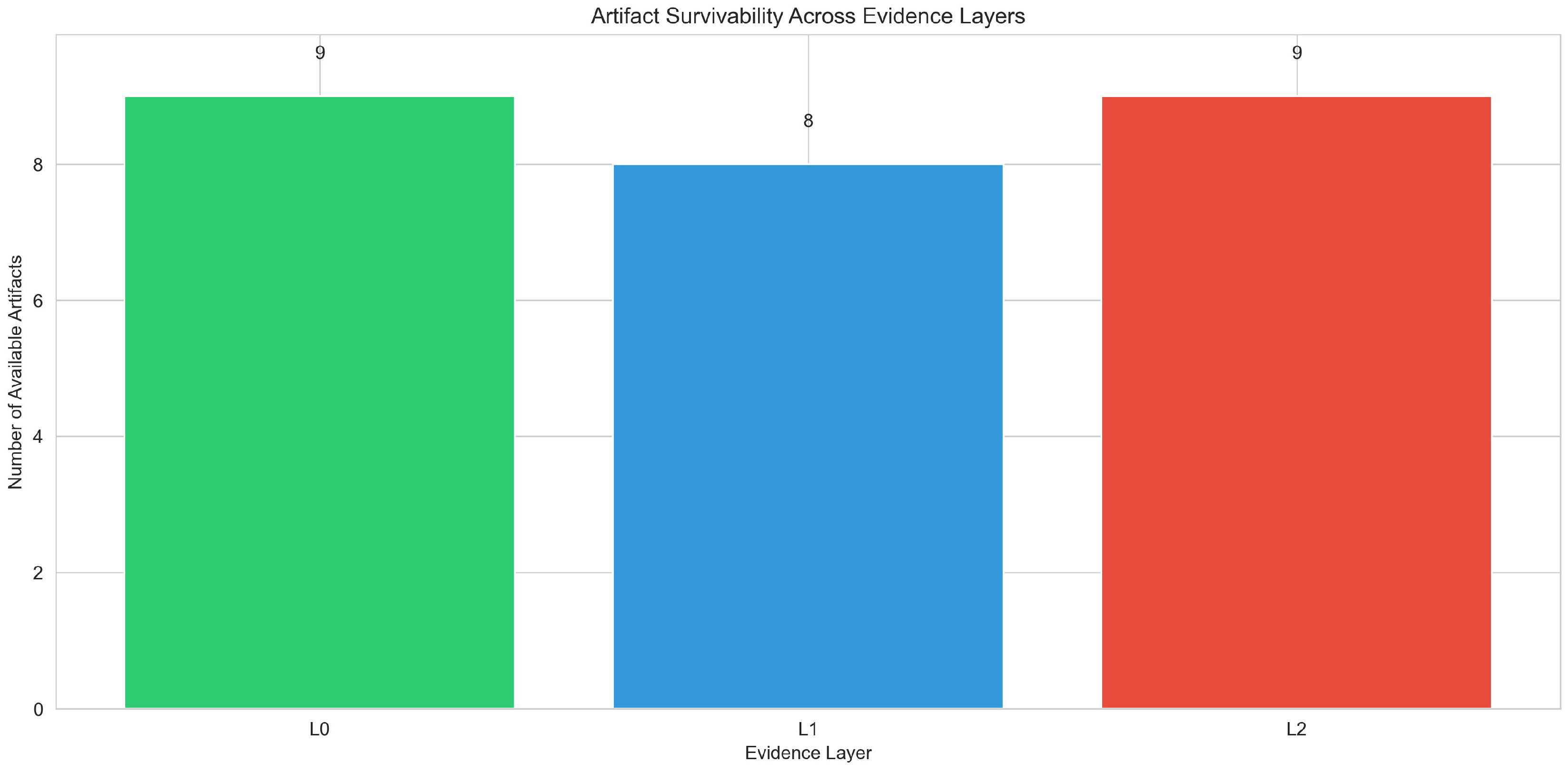

Appendix C.1. Artifact Survivability

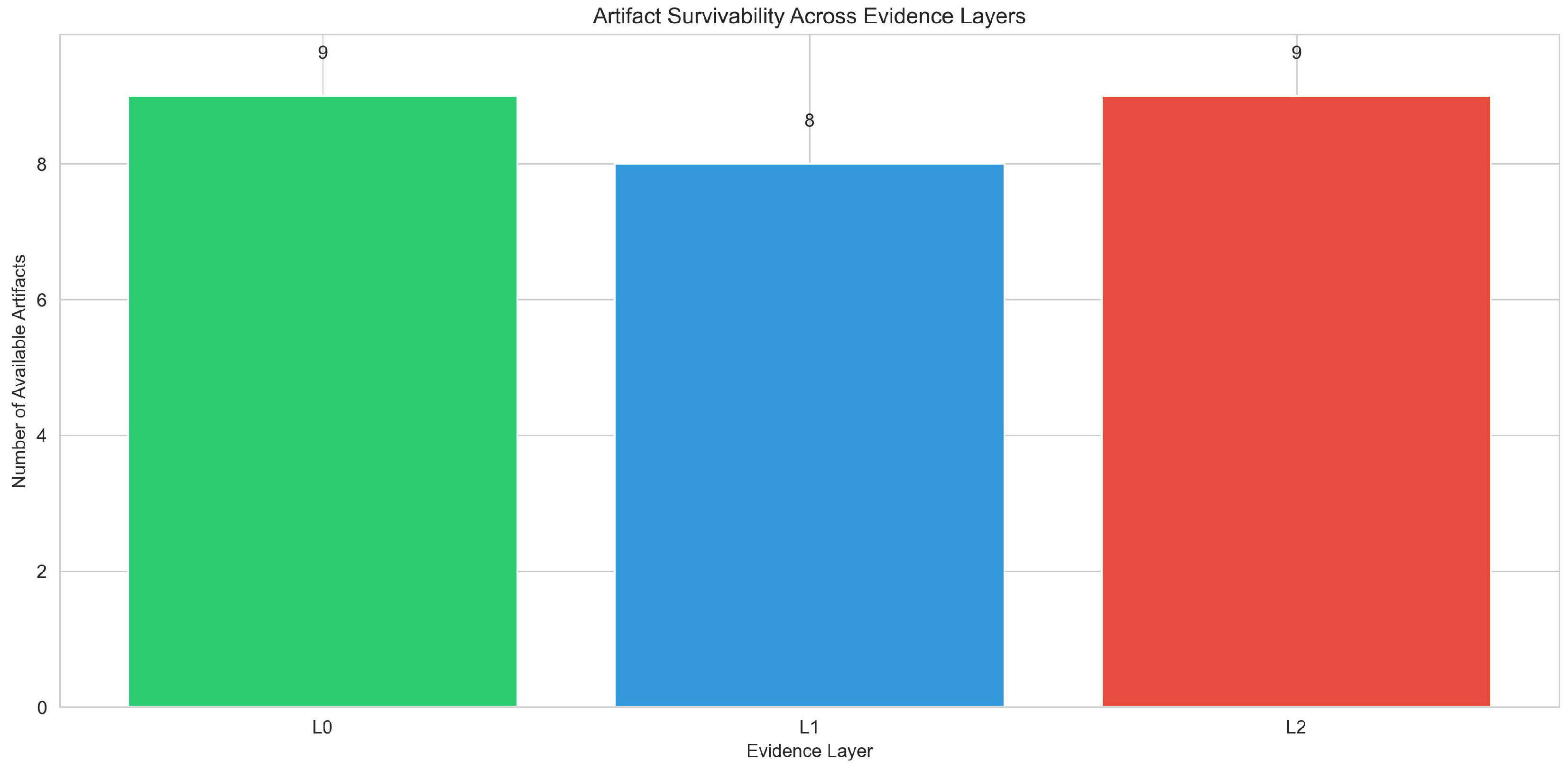

Figure A3 and

Figure A4 show artifact survivability for the 06:00 and 12:00 windows, complementing the pattern established in the main text. The consistent pattern across windows—10 artifacts at L0, 11 at L1 (reflecting emergence of flow-specific properties), and 9 at L2—validates that artifact computability is representation-driven rather than traffic-dependent.

Figure A3.

Artifact survivability across evidence layers for the 06:00 time window. The pattern matches the 00:00 window: 10 artifacts computable at L0, 11 at L1 (including flow duration, directional asymmetry, and short-lived flow patterns), and 9 at L2.

Figure A3.

Artifact survivability across evidence layers for the 06:00 time window. The pattern matches the 00:00 window: 10 artifacts computable at L0, 11 at L1 (including flow duration, directional asymmetry, and short-lived flow patterns), and 9 at L2.

Figure A4.

Artifact survivability across evidence layers for the 12:00 time window. The identical pattern (10/11/9) across all three windows demonstrates structural invariance of artifact computability under evidence abstraction.

Figure A4.

Artifact survivability across evidence layers for the 12:00 time window. The identical pattern (10/11/9) across all three windows demonstrates structural invariance of artifact computability under evidence abstraction.

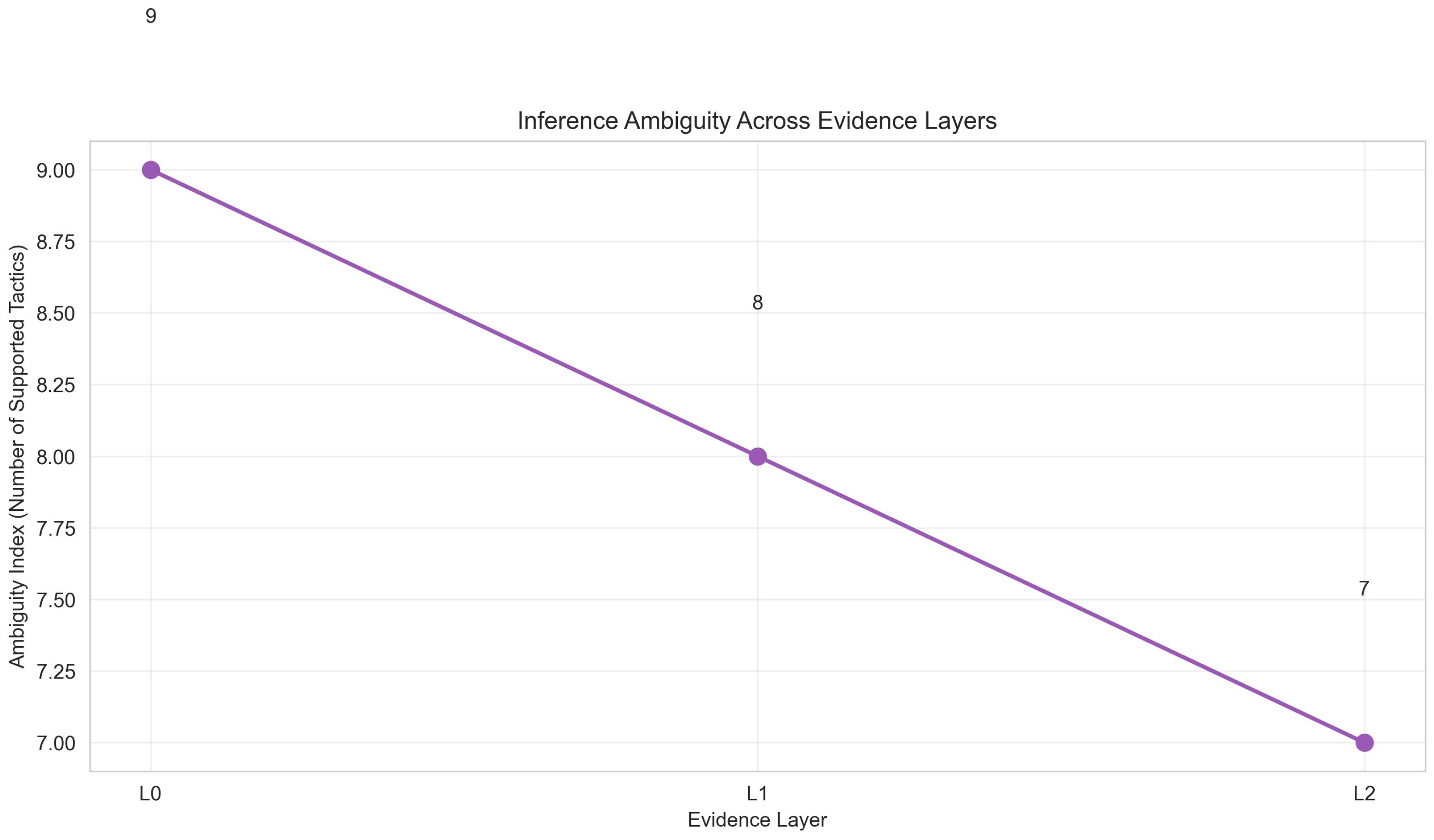

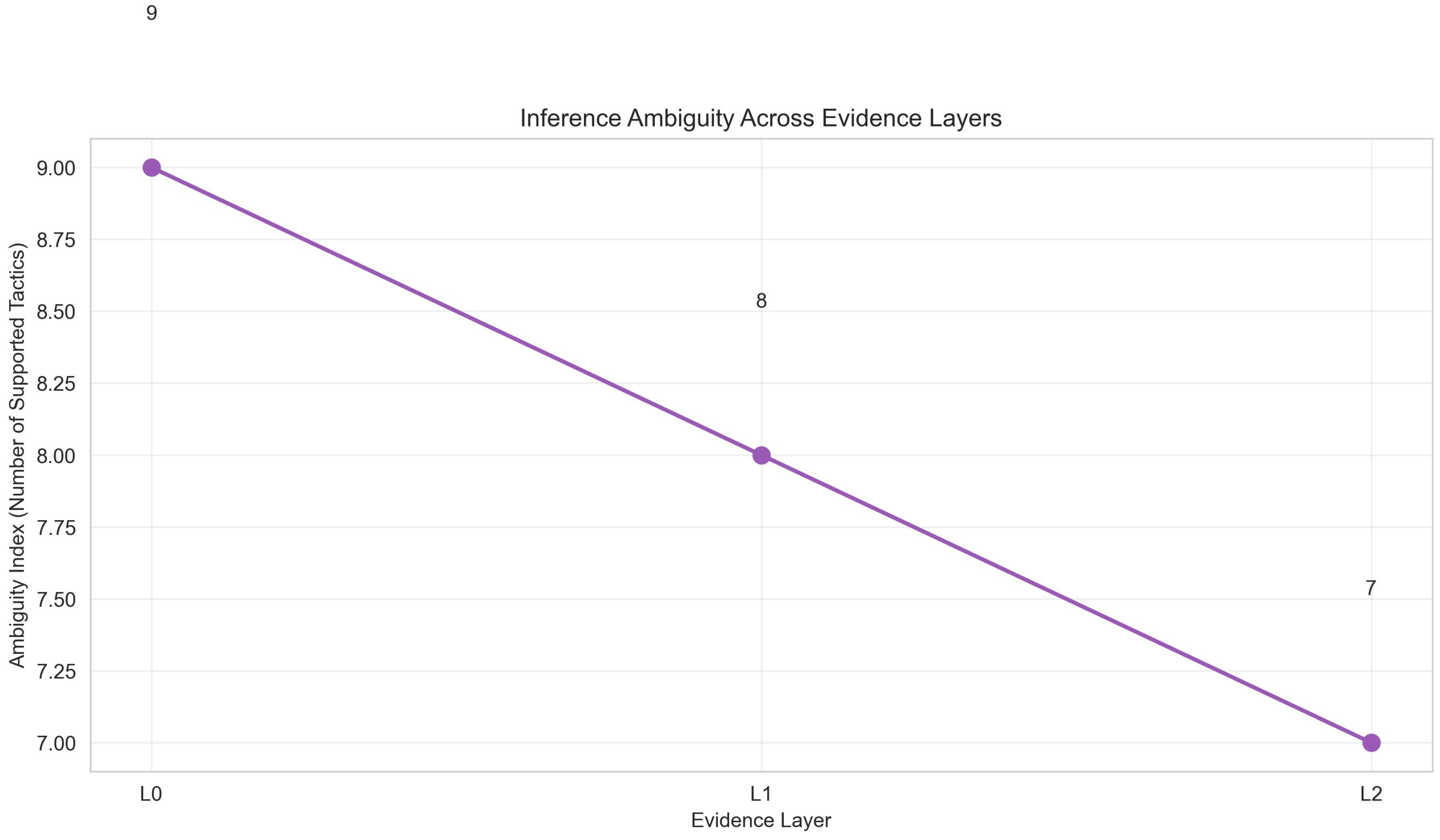

Appendix C.2. Inference Coverage (Ambiguity Index)

Figure A5 and