1. Introduction

There has been an intensive search for ways to increase the activity of catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) in order to decrease the catalyst cost in H

2-O

2 fuel cells, which are an integral component of the much-anticipated hydrogen energy economy. Much research has been devoted to fine-tuning the adsorption of reactants and intermediates in order to reach the summit of the famed volcano plot, in which reaction rate is plotted versus the adsorption strength of oxygenated species, OH for example. The adsorption strength of most oxygenated species, including O

2, O, OH, HO

2 all appear to be proportional to each other, the so-called scaling relationship [

1]. Thus, if it is assumed that OH adsorption should be weakened, O

2 adsorption would also be weakened. This is a dilemma that has been largely ignored thus far. Nevertheless, it has been found experimentally that the use of Pt alloys such as Pt-Co with decreased OH adsorption strength has resulted in increased ORR rates. Interestingly, no Pt alloys have been reported for which O

2 adsorption is too weak, even though theoretical results show that adsorption on Pt-covered Pt-Fe should be very weak indeed, on the order of -0.15 to -0.20 eV, which should in principle have a detrimental impact upon O2 capture [

2,

3,

4]. At this point, O

2 must compete with water for adsorption sites, as shown later. Clearly, this approach has its limits, since eventually

O2 adsorption would be impaired.

One key to this puzzle has been the recognition that platinum surfaces based on Pt(111) that include steps, either (110) or (100), can have increased ORR activity based on area, usually with a maximum activity being observed at intermediate terrace widths [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Early theoretical work predicted that stepped surfaces would be less active than Pt(111), based on the strong adsorption of OH at steps [

9]. Bandarenka et al. proposed that the maximum in ORR activity at intermediate step density is due to a trade-off between OH removal and OH formation rates, based on H-bonded water network stabilization of OH [

10]. Subsequently, Jinnouchi et al. have similarly explained the presence of a maximum in the ORR activity at intermediate step widths based on the trade-off between destabilization of OH and stabilization of HO

2 adsorbed on (111) terraces by water molecules [

11]. In contrast, Hoshi and coworkers have argued that, since the step structures differ between (110) and (100) steps, with the activities being similar, the steps themselves cannot be the active sites, which are proposed to be the (111) terraces immediately adjacent to the steps [

8]. Subsequently, Kodama et al. reported that a variety of Pt stepped surfaces in which the steps are capped with gold are still active for the ORR [

12]. This result seems to strongly suggest that the steps themselves are not the active sites, based on the assumption that gold is inactive for the ORR, at least in acid electrolytes, although high activity can be observed in alkaline electrolytes [

13,

14].

The present work aims to take into account the clearly observed experimental results that the ORR activity in acid electrolyte mainly increases with step density, both (110) and (100) steps on Pt(111) surfaces except for very narrow (111) terraces. The simplest assumption is that the steps have an increased adsorption strength for O

2 so that the ORR current is proportional to the O

2 coverage at the step. Using DFT calculations, we have found that indeed the O

2 adsorption strength is significantly higher at steps compared with the terraces. In addition, we have found that water molecules adsorbed on either side of the bridging O2 can assist in its dissociation, creating 4 OH, and the activation energies are much smaller at both types of steps than on the (111) terrace. Thus, water is being used as a proton donor, which has been shown to be important for alkaline electrolytes but not thus far for acid [

13].

In principle, these results can help to escape the scaling relation dilemma by the use of Pt alloys on which OH adsorption on (111) terraces is weak, but the

O2 adsorption at steps is still strong enough so that the overall reaction rate is enhanced. Rurigaki et al. have studied PtNi alloy stepped surfaces experimentally and have found some deviations from the trends observed for pure Pt surfaces, however [

15]. Nevertheless, we believe that the present model may be useful in the search for more active ORR catalysts.

2. Results

O

2 has been found to be relatively stable on Pt(111) and has been observed directly with STM [

16] [

17]. Its adsorption energy is compared on these surfaces in

Table 1. The adsorption energies for O2 adsorption on the (100) edge of Pt(533) and the (110) edge are quite similar, -1.96 and -1.86 eV, respectively, far larger than that on Pt(111), -0.89 eV. The presence of water stabilizes O2 on both steps slightly but destabilizes that on Pt(111). The adsorption energies of O2 on the (111) terraces of Pt(533) and Pt(553) are also similar to those on Pt(111) itself. Thus, O

2 is expected to adsorb at the steps rather than on the terraces, as long as the latter are not covered with OH, which adsorbs strongly. However, it must be kept in mind that the adsorption energy for OH is referred to gas-phase OH and thus is misleadingly large.

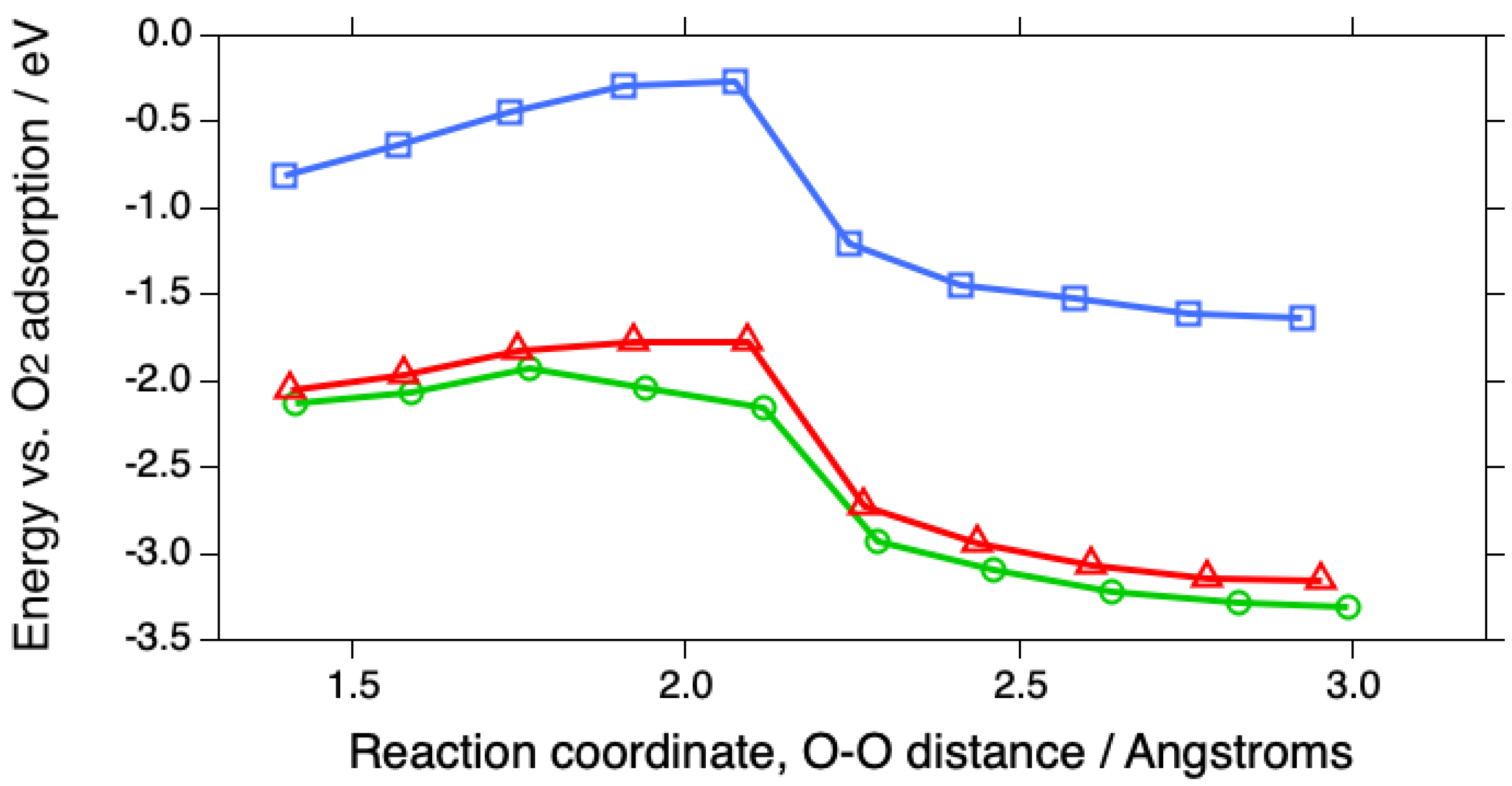

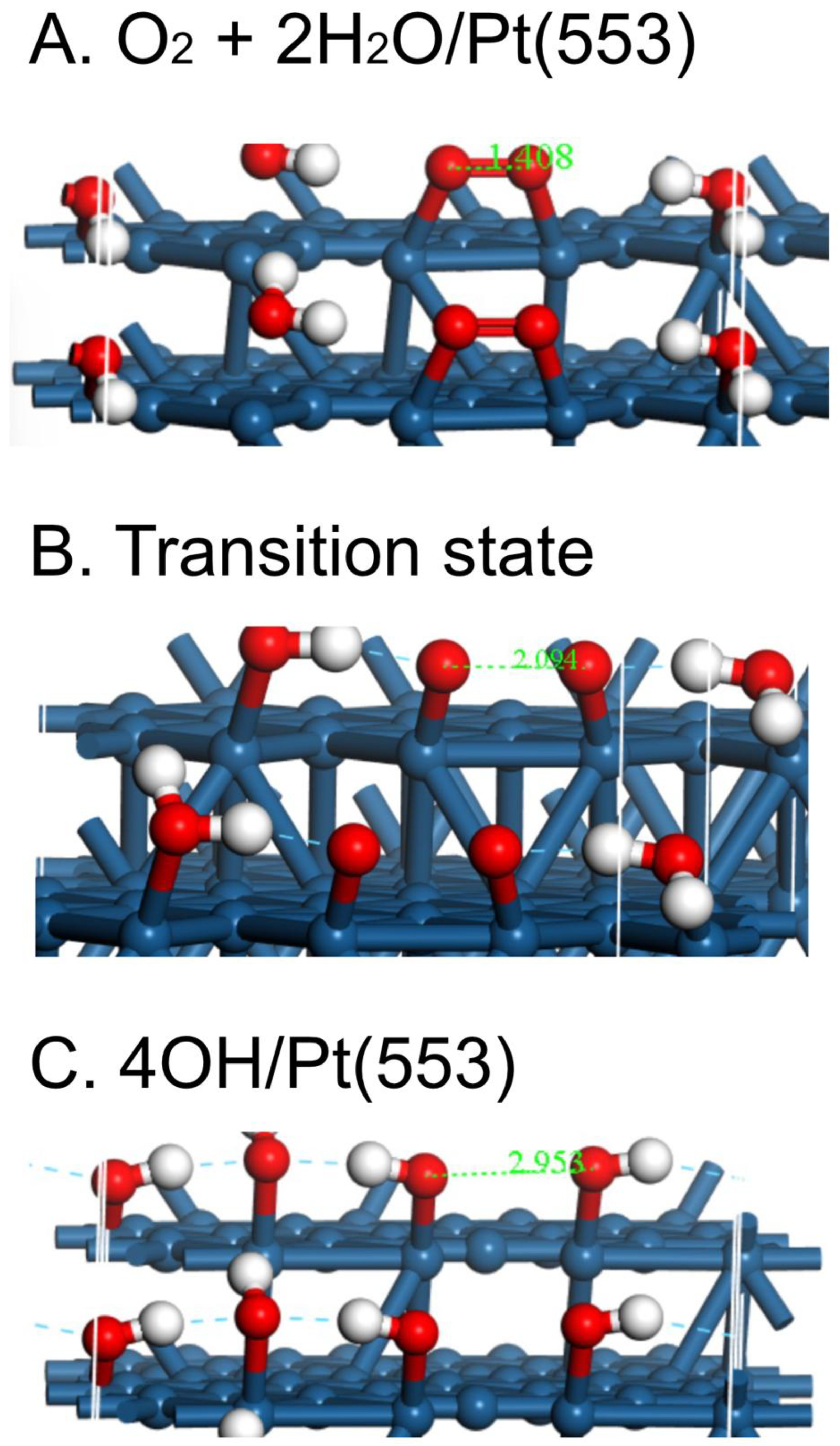

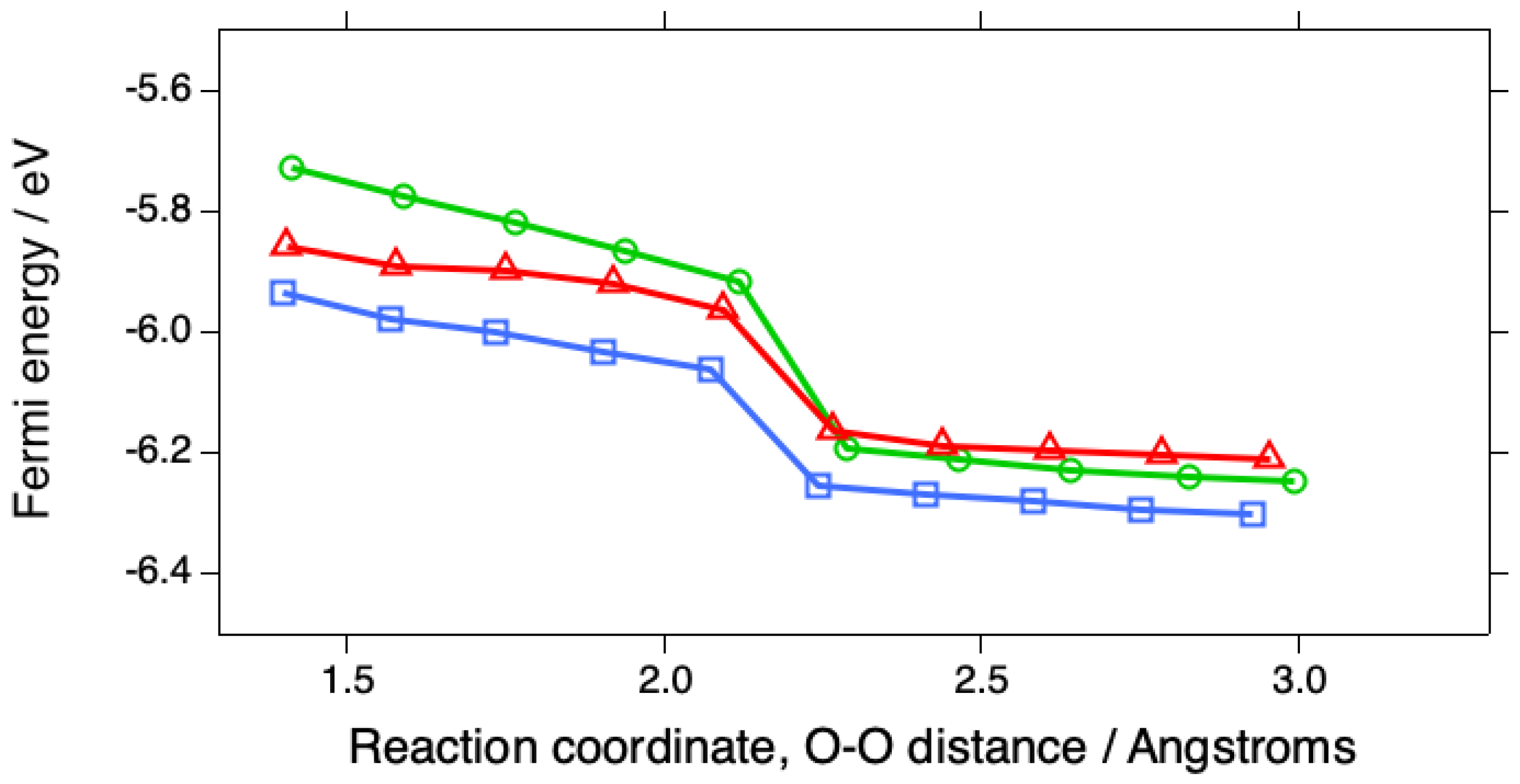

To get a more realistic idea of the first steps in the ORR, the energies of the O

2-2H

2O system have been plotted as the O-O bond is stretched in ca. 0.2 Å increments on Pt(533), Pt(553) and Pt(111) (

Fig. 1), in much the same way as was done for O2 dissociation on Pt(111), Pt(211) and Pt(221) in a UHV study by Gambardella et al. [

17]. As with the latter study, the behavior on the two stepped surfaces is somewhat similar, but the activation energy E act is somewhat smaller on Pt(533), 0.21 vs. 0.28 eV (

Table 2). Both energies are far smaller than that on Pt(111), 0.55 eV. In contrast, Gambardella calculated values of 0.9 eV for O

2 dissociation energies on three surfaces, Pt(111), Pt(211) and Pt(221) using DFT. However, Gee and Hayden found O

2 to be dissociated more readily on Pt(533) than Pt(111) in UHV [

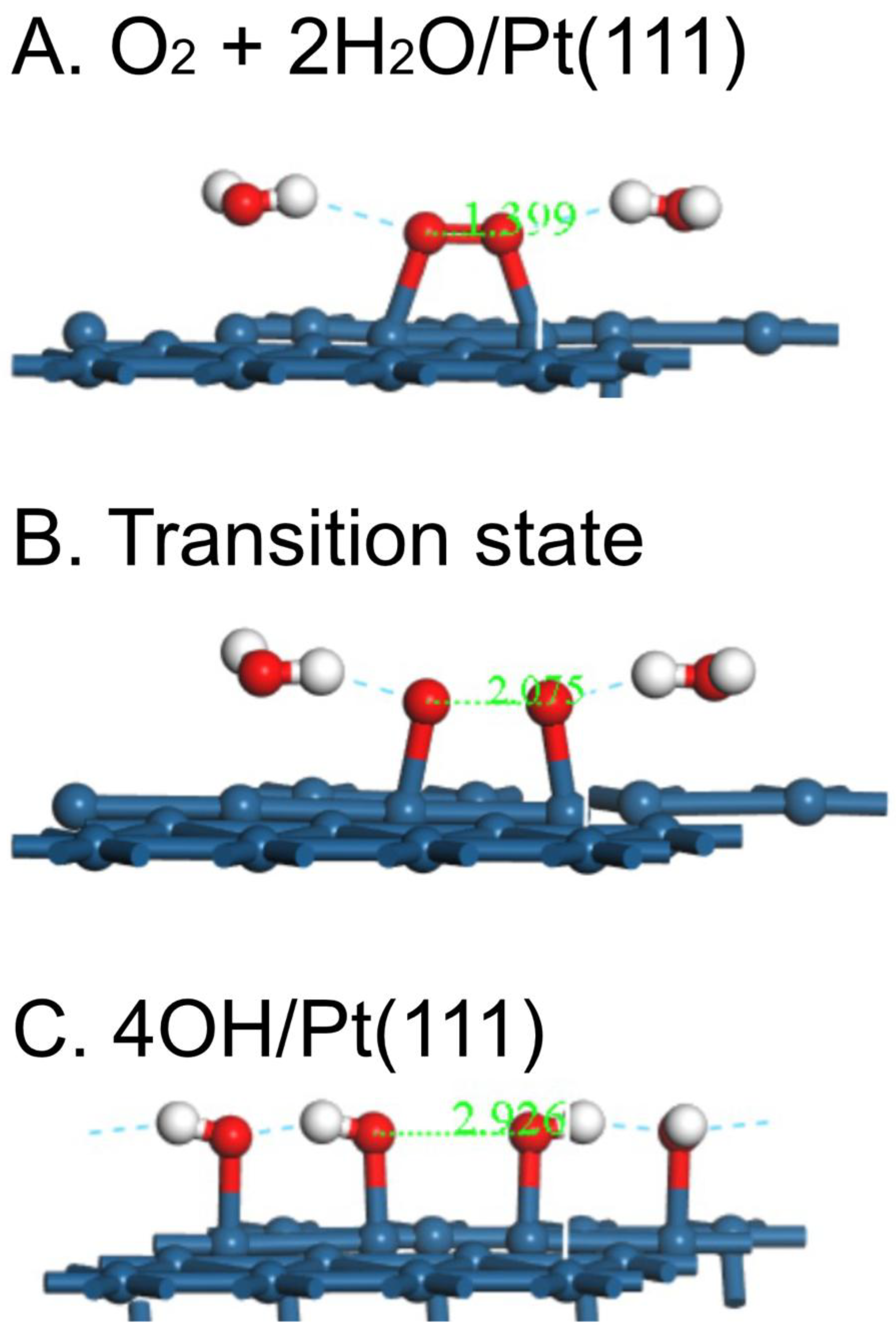

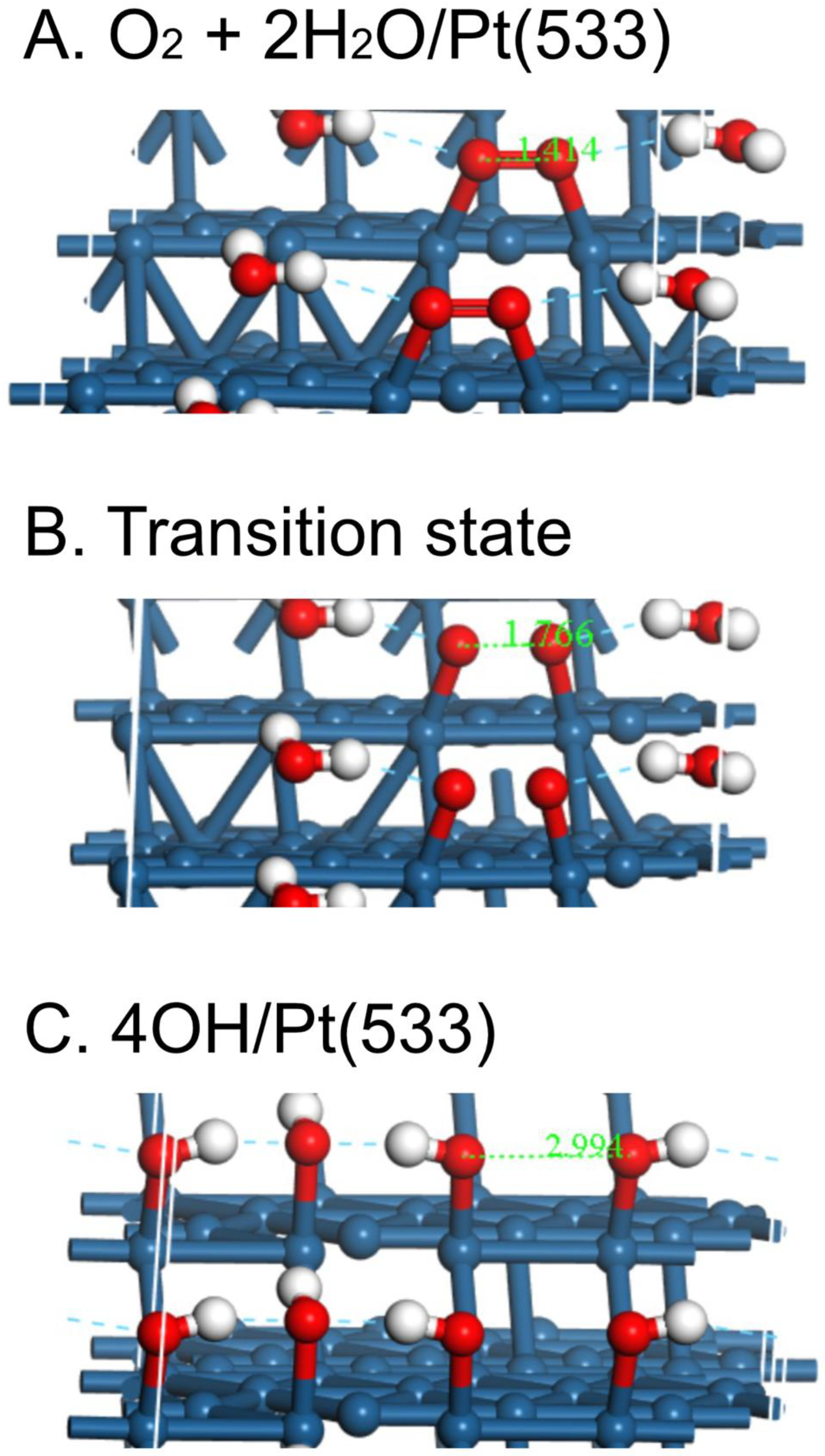

18]. The corresponding atomic models for the overall process are shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 for Pt(111), Pt(533) and Pt(553), respectively.

The reasons for the great differences in E act are proposed to involve both the stronger adsorption of O2 but also that of H2O, which is ca. 0.75 eV stronger at the steps than on the (111) terrace. Thus, the reactants are held in place firmly during the overall reaction. Even more importantly, O2 adsorbs more strongly at the steps than does water, in contrast to the situation on Pt(111), on which water is calculated to adsorb more strongly than O2, which would lead to an impairment of the ORR activity. This is a result that has not been reported thus far to our knowledge. It should also be noted that water adsorption does not follow the usual scaling relations, so that it is possible for water to adsorb more strongly than O2.

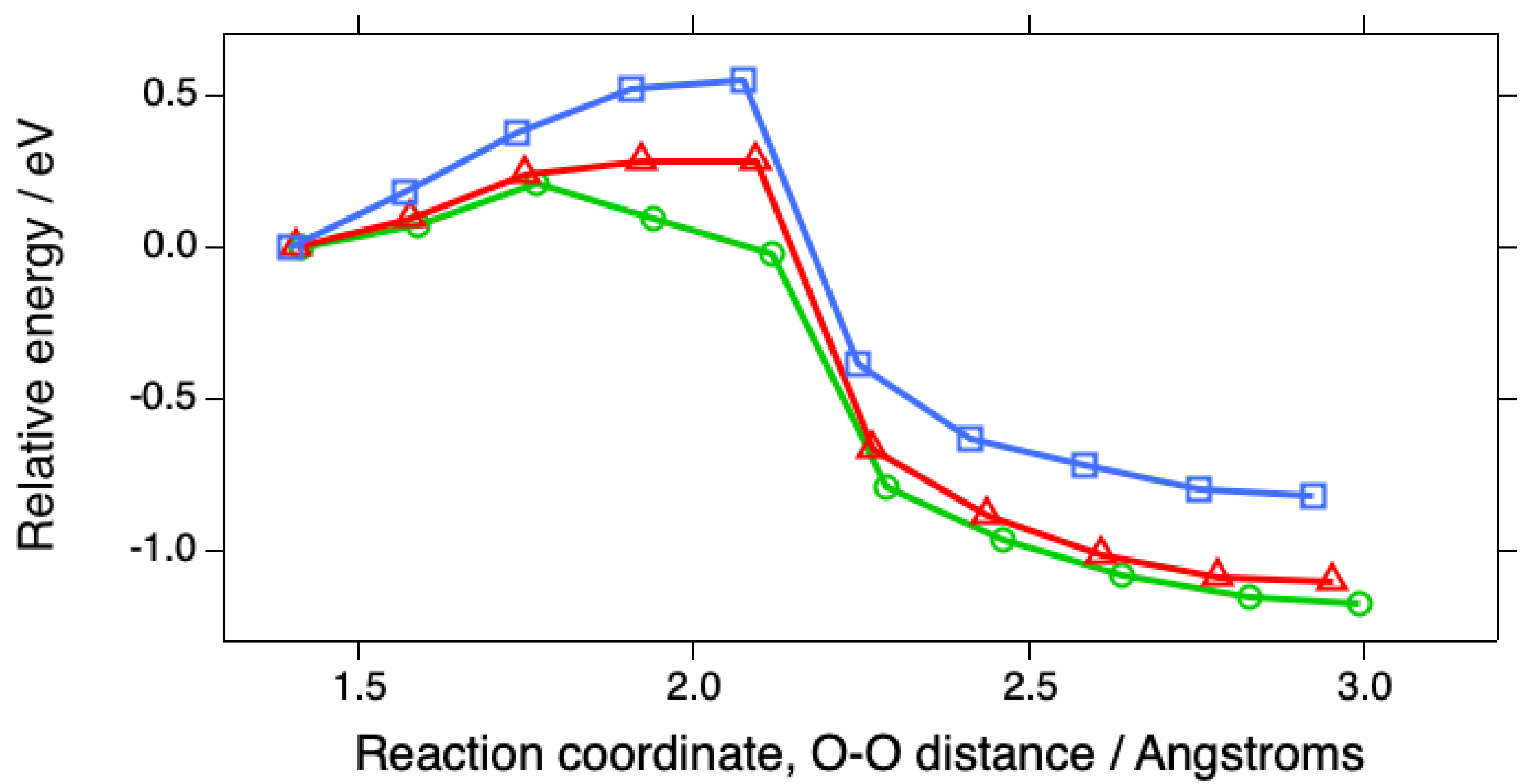

The overall reaction can also be plotted to show the differences in the initial O

2 adsorption energies (Fig. 2). This representation emphasizes the great advantage of the stepped surfaces in terms of capturing O

2 from solution. These reaction profiles follow the well-known BEP relation, which predicts that, for dissociation reactions, the activation energy should decrease as the energy of the products is decreased, as long as the activated state is similar to the product state [

25].

Figure 5.

Reaction profiles for the first steps in the ORR involving O2 adsorbed in the bridging configuration at (100) steps on Pt(533) (green circles), at (110) steps on Pt(553) (red triangles), and on Pt(111) (blue squares), as in Fig. 1 but with the energies referred to the adsorption energy of O2 on the surface with two water molecules present.

Figure 5.

Reaction profiles for the first steps in the ORR involving O2 adsorbed in the bridging configuration at (100) steps on Pt(533) (green circles), at (110) steps on Pt(553) (red triangles), and on Pt(111) (blue squares), as in Fig. 1 but with the energies referred to the adsorption energy of O2 on the surface with two water molecules present.

In contrast to most recent DFT studies, we have elected to plot the results in terms of the directly calculated DFT energies of the systems as the O-O bond is stretched, with the numbers of atoms necessarily remaining constant. The approach is essentially that which would be used in a purely chemical reaction in a closed system, so that, as the reaction proceeds, a reverse driving force builds up. The way this occurs in the present approach is that the effective electrochemical potential U becomes more positive during the reaction, which would cause the rate of a reduction reaction such as the ORR to slow down.

U can be thought of as a linear function of the Fermi energy

EF, which can be plotted versus the reaction coordinate (

Figure 6). In order to produce a reaction profile in which

U is constant, it will be necessary to perform calculations on a series of similar systems in which the initial

EF is varied and then curve-fit the energy surface, i.e., the energy vs.

EF vs. reaction coordinate.

3. Discussion

The present work attempts to shed light on the reasons for the increased ORR rate in acid electrolytes on stepped Pt surfaces with increasing step density, based on the simplest possible assumption, which is that the O2 adsorbs more strongly at the steps than on the terraces. This point is crucial, because, on Pt(111), water adsorption is similar in strength to that of O2, and, on certain alloys, O2 adsorption can be significantly weaker than that of water. Therefore, steps are necessary in order to ensure that O2 can be captured effectively from the electrolyte. It has been proposed by various groups that the effect of the step is to modulate the water structure close to the catalyst surface and thus stabilize or destabilize intermediates in the ORR. However, this model does not take into account the competition between O2 and water for adsorption sites on the (111) terrace.

4. Materials and Methods

DFT calculations were carried out with the use of the DMol3 program (BIOVIA, Dassault Systemes, v. 2023) with periodic boundary conditions for Pt(533), Pt(553) and Pt(111). The first steps in the ORR have been modeled starting with one O2 molecule and two H2O molecules.

Funding

The author gratefully acknowledges support from The New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will supply necessary data upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Calle-Vallejo, F.; Loffreda, D.; KoperMarc, T.M.; Sautet, P. Introducing structural sensitivity into adsorption–energy scaling relations by means of coordination numbers. Nat Chem 2015, 7, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, J.; Mavrikakis, M. Surface and Subsurface Hydrogen: Adsorption Properties on Transition Metals and Near-Surface Alloys. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 3460–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Yano, H.; Tryk, D.A.; Nohara, S.; Uchida, H. High hydrogen evolution activity and suppressed H2O2 production on Pt-skin/PtFe alloy nanocatalysts for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 2861–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryk, D.A.; Shi, G.; Kakinuma, K.; Uchida, M.; Iiyama, A. Mechanisms for the Production and Suppression of Hydrogen Peroxide at the Hydrogen Electrode in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells and Water Electrolyzers: Theoretical Considerations. Catalysts 2024, 14, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciá, M.D.; Campiña, J.M.; Herrero, E.; Feliu, J.M. On the kinetics of oxygen reduction on platinum stepped surfaces in acidic media. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2004, 564, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzume, A; Herrero, E; Feliu, J. M: Oxygen reduction on stepped platinum surfaces in acidic media. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2007, 599, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitotsuyanagi, A.; Nakamura, M.; Hoshi, N. Structural effects on the activity for the oxygen reduction reaction on n(111)-(100) series of Pt: correlation with the oxide film formation. Electrochimica Acta 2012, 82, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, N.; Nakamura, M.; Hitotsuyanagi, A. Active sites for the oxygen reduction reaction on the high index planes of Pt. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 112, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, J.; Rossmeisl, J.; Hellmann, A.; Norskov, J.K. Theoretical Trends in Particle Size Effects for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. 2007, 221, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarenka, A.S.; Hansen, H.A.; Rossmeisl, J.; Stephens, I.E.L. Elucidating the activity of stepped Pt single crystals for oxygen reduction. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2014, 16, 13625–13629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinnouchi, R.; Kodama, K.; Nagoya, A.; Morimoto, Y. Simulated Volcano Plot of Oxygen Reduction Reaction on Stepped Pt Surfaces. Electrochimica Acta 2017, 230, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, K.; Jinnouchi, R.; Takahashi, N.; Murata, H.; Morimoto, Y. Activities and Stabilities of Au-Modified Stepped-Pt Single-Crystal Electrodes as Model Cathode Catalysts in Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 4194–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszak-Jirkovský, J.; Subbaraman, R.; Strmcnik, D.; Harrison, K.L.; Diesendruck, C.E.; Assary, R.; Frank, O.; Kobr, L.; Wiberg, G.K.H.; Genorio, B.; et al. Water as a Promoter and Catalyst for Dioxygen Electrochemistry in Aqueous and Organic Media. ACS Catalysis 2015, 6600–6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lu, D.; Su, D.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, J.X.; Adzic, R.R.; et al. Surface Proton Transfer Promotes Four-Electron Oxygen Reduction on Gold Nanocrystal Surfaces in Alkaline Solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139, 7310–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurigaki, T.; Hitotsuyanagi, A.; Nakamura, M.; Sakai, N.; Hoshi, N. Structural effects on the oxygen reduction reaction on the high index planes of Pt3Ni: n(111)-(111) and n(111)-(100) surfaces. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2014, 716, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipe, B.C.; Rezaei, M.A.; Ho, W.; Gao, S.; Persson, M.; Lundqvist, B.I. Single-Molecule Dissociation by Tunneling Electrons. Physical Review Letters 1997, 78, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, P.; Sljivancanin, Z.; Hammer, B.; Blanc, M.; Kuhnke, K.; Kern, K. Oxygen dissociation at Pt steps. Physical Review Letters 2001, 87, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, A.T.; Hayden, B.E. The dynamics of O[sub 2] adsorption on Pt(533): Step mediated molecular chemisorption and dissociation. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 10333–10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gland, J.L.; Sexton, B.A.; Fisher, G.B. Oxygen interactions with the Pt(111) surface. Surface Science 1980, 95, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gland, J.L. Molecular and atomic adsorption of oxygen on the Pt(111) and Pt(S)-12(111) ラ (111) surfaces. Surface Science 1980, 93, 487–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, A.; Hafner, J. Molecular Precursors in the Dissociative Adsorption of O2 on Pt(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 4481–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S. First-Principle Study of the Adsorption and Dissociation of O2 on Pt(111) in Acidic Media. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 20657–20665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, H.; Liu, J. First principles study of O2 dissociation on Pt(111) surface: Stepwise mechanism. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2016, 116, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerer, M.J.; Santos-Carballal, D.; Cadi-Essadek, A.; van Sittert, C.G.C.E.; de Leeuw, N.H. Interaction of H2O with the Platinum Pt (001), (011), and (111) Surfaces: A Density Functional Theory Study with Long-Range Dispersion Corrections. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2019, 123, 27465–27476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, B. Special sites at noble and late transition metal catalysts. Topics in Catalysis 2006, 37, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).