1. Introduction

The impact wrench (driver) is used in construction, automotive, and many other industries to tighten bolts. These devices are required to achieve higher torque and speed than with hand tightening. The functioning of an impact hammer is described by Matthiesen et al. [

1]. The impacts that this tool generates repeat at approximately 42 Hz. These vibrations pose serious health risks to operators of such power tools. A public health practice paper [

2] outlines the clinical signs of hand-arm vibrations (HAV) syndrome: blanched fingers, tenderness or pain and swelling of the fingers and forearm tissue, paresthesia or tingling in fingers, cold intolerance, weakness of the finger flexors or intrinsic muscles, loss of muscle control, reduced sensitivity to heat and cold, discoloration and trophic skin lesions of the fingers, and loss of manipulative dexterity and finger coordination. A study by Per Vihlborg et al. [

3] found an association between vibration exposure and HAV symptoms (HAVs) in the Swedish mechanical industry. Workers exposed to HAV have a 4–5 fold increased risk of vascular and neurological diseases [

4]. Animal models have been used to replicate the damage caused by HAVs [

5]: in a field survey it was found that 15% of power tools exceeded the action limits according to applicable standards [

6]. Mazaheri et al. [

7] show that the industry still needs to develop stricter standards for vibration limits. There is significant evidence that the manufacturers’ declared vibration values are underestimated [

8]. Recent exposure and dose–response studies further motivate reducing HAV in practice [

9,

10]. Most papers provide methods for assessing the exposure of vibrations produced by power tools or modeling of the hand–arm vibrations. This paper develops and validates a low-order model for illustrating the major contributing components of vibrations of impact hammers. Prior work has used finite element models to estimate impact coefficients [

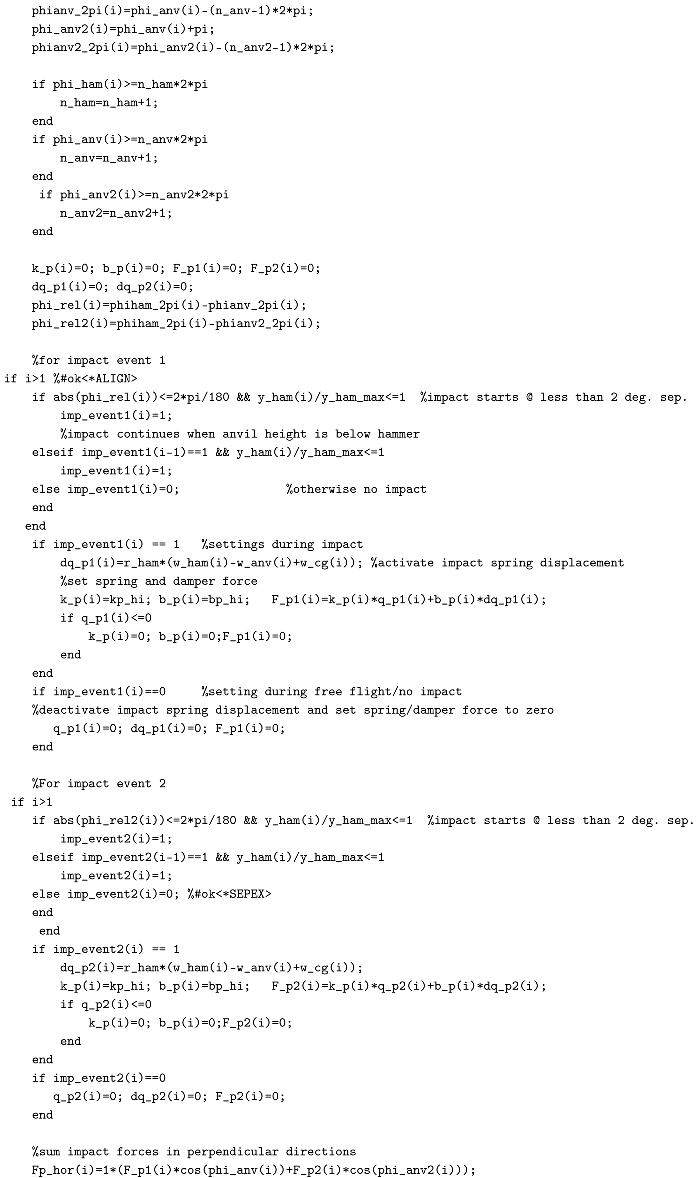

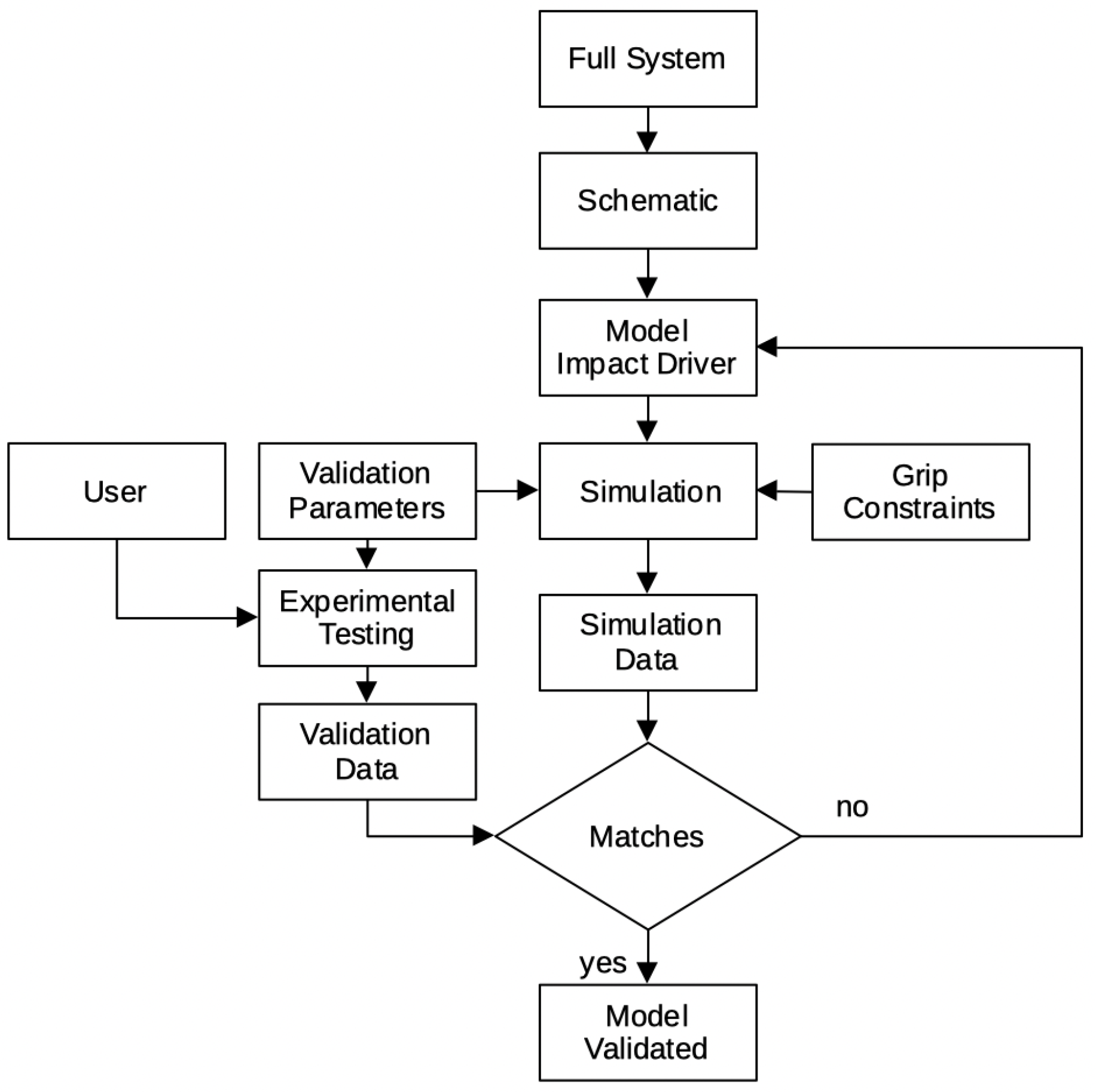

11]. Here, comparable results are obtained using bond graphs. This work differs from other studies and solutions in that it provides a low-order model for assessing the origins of hand–arm vibrations. This model can be used to test the relative efficacy of vibration control concepts. The bond graphs provide a level of abstraction that yields an understanding of the fundamental architecture of the system. This abstraction helps find and test possible solutions. The model was validated using the procedure shown in

Figure 1.

Related Work and Contribution. Beyond finite-element approaches for impact modeling [

11], a large body of work on biodynamic models of the human hand–arm system exists [

12]. System-level identification of electric impact wrenches has also been explored [

13]. In contrast to high-order FE, physiological, or ID-only models, the proposed physics-based low-order model targets rapid, system-level design exploration of the impact wrench as an electromechanical system, reproducing axis-wise RMS and spectral characteristics relevant to ISO 28927-13 while remaining simple enough to guide mechanism-level changes.

2. Model Development

Bond graphs were used to develop component models and then assemble the component models into an overall system model. Bond graphs are a pictorial representation of all types of dynamic systems interacting in multiple energy domains. Ref. [

14] describes bond graph modeling and development. All the bodies are assumed rigid and contacts are represented by a linear stiff spring and damper. The model is limited to systems with similar dimensions and power.

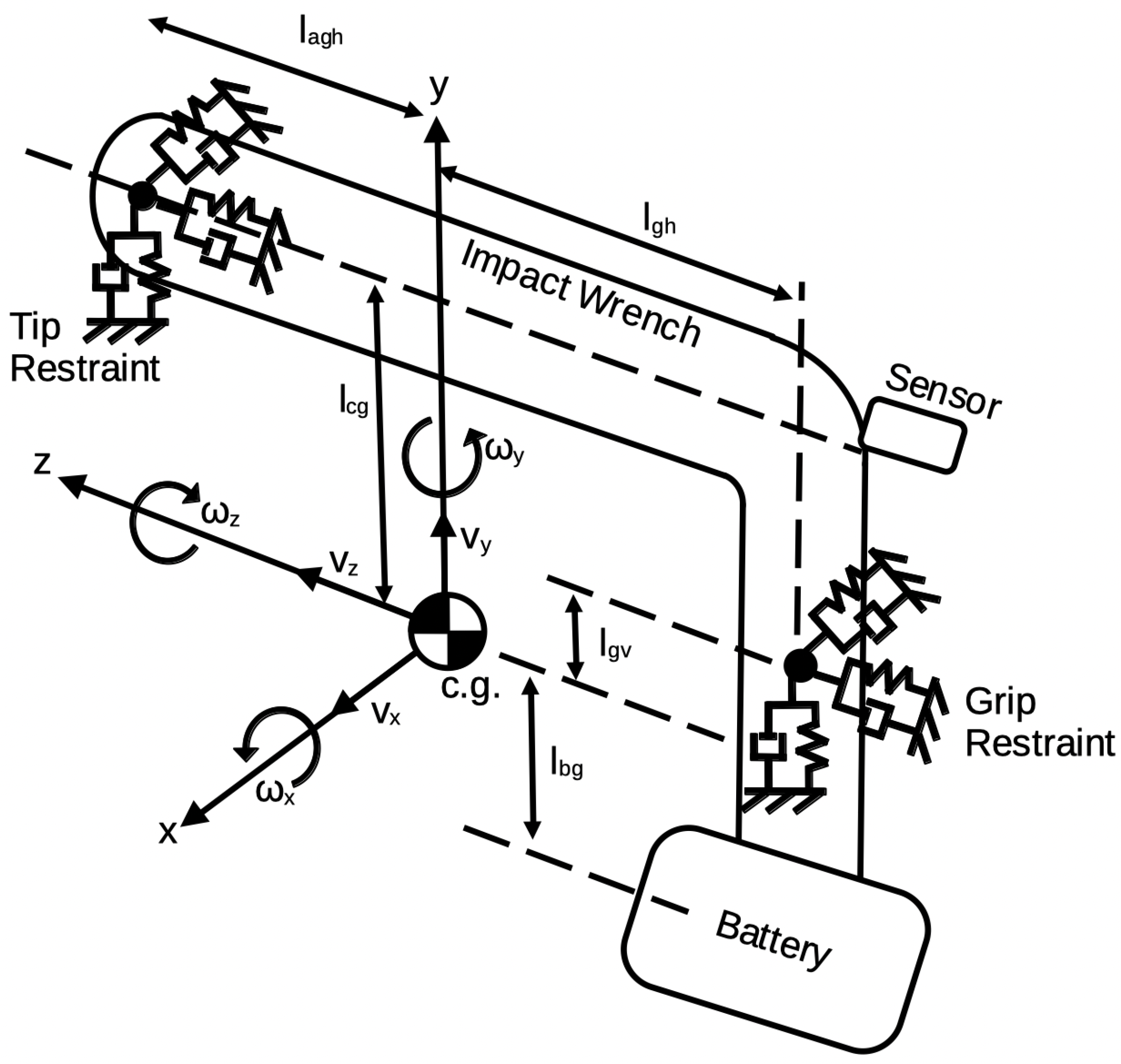

Figure 2 shows the tool mass,

, the battery mass,

, the total mass,

, vertical distance from tool centerline to center of gravity (CG),

, vertical distance from CG to battery,

, vertical distance from CG to grip location,

, horizontal distance from CG to grip location,

, horizontal distance from tool tip to CG,

. The sensor is located by vertical and horizontal distances from the CG. These can vary based on the location of the sensor.

Assumptions and Limitations. The tool is modeled as an assembly of rigid bodies with impacts represented by linear spring–damper contact elements. Small angular motions are assumed for the rigid-body coupling in

Figure 4. Hand/arm interaction is represented using lumped linear translational and torsional constraints tuned to the literature, rather than a detailed physiological (distributed) model. As such, the model is intended for rapid, system-level design exploration and does not capture detailed structural flexibility, high-frequency modes beyond the validated range, or tooth-level contact mechanics.

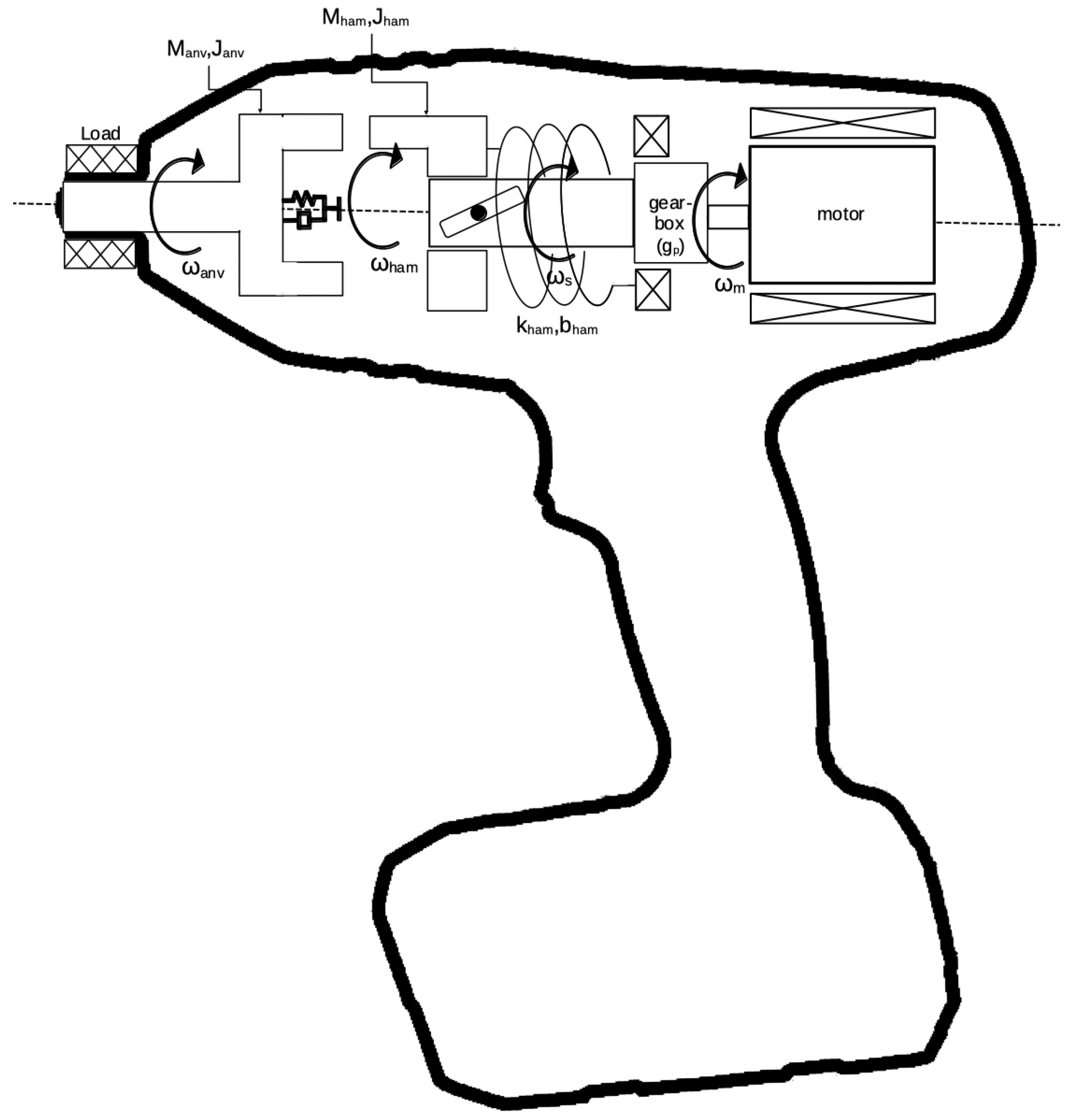

Figure 3 shows the dynamic components of the impact hammer. The battery-powered electric motor of mass,

, and moment of inertia,

, drives the rotating shaft at angular velocity

through a reduction gearbox of ratio,

. The shaft has a slot at its end with a trapped ball that rotates the hammer of mass,

, and rotational inertia,

. The hammer then strikes the anvil of mass,

, and rotational inertia,

, such that the rotation of the hammer is virtually stopped. When this happens, the shaft continues to rotate and the ball-and-slot mechanism lifts the hammer until the hammer clears the anvil and rotates again. The ball/slot has a prescribed angle relative to the shaft and is represented here as a modulus,

, specifying the rise of the hammer per rotation angle of the shaft. As the hammer is lifted, it compresses the spring of stiffness,

and damping,

, and then when the hammer clears the anvil the spring pushes the hammer back towards the anvil. The hammer continues to rotate and move downward until it strikes the anvil at a location 180 from the initial strike. As a result of the strike from the hammer onto the anvil, the anvil advances in the direction of the strike by some number of degrees depending on the load on the anvil. This is the basic operation of the impact hammer.

The impact between the hammer and anvil is a major source of vibration felt by an operator of the tool. Additionally, the compression and extension of the hammer spring also provides significant forcing on the tool. Ideally, the downward motion of the hammer after it clears the anvil would have the hammer reach the ’floor’ of the hammer just as it strikes the anvil the next time. In reality this rarely happens and the hammer can either impact the hammer floor prior to striking the anvil thus producing more unwanted vibration or it can miss the next strike completely by not being lowered sufficiently quickly during some part of the operating cycle. All of these potential scenarios are part of the dynamic model being developed here.

Impact between moving dynamic elements has been a research topic for many years. The work in [

11] is indicative of the history of impact models. For the model here, impact is represented by a very stiff spring and damper,

and

, that are activated when the relative displacement between the impacting bodies is less than a specified amount. Related torsional-impact modeling and stiffness estimation for impact wrenches further supports this formulation [

15], as do studies of energy/torque exchange during tightening [

16]. The stiffness is determined through numerical experimentation and considered stiff enough when the displacement across the impact spring is less than a fraction of a millimeter. In this development, impact between the hammer and anvil, and between the hammer and ”floor” are both included.

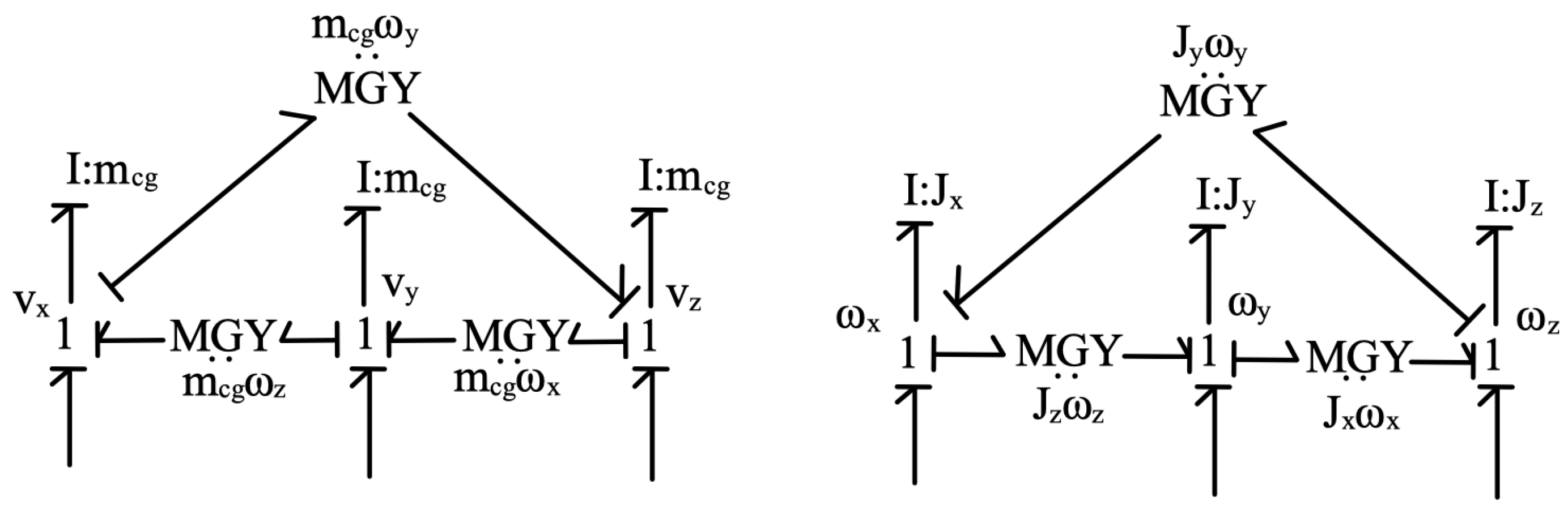

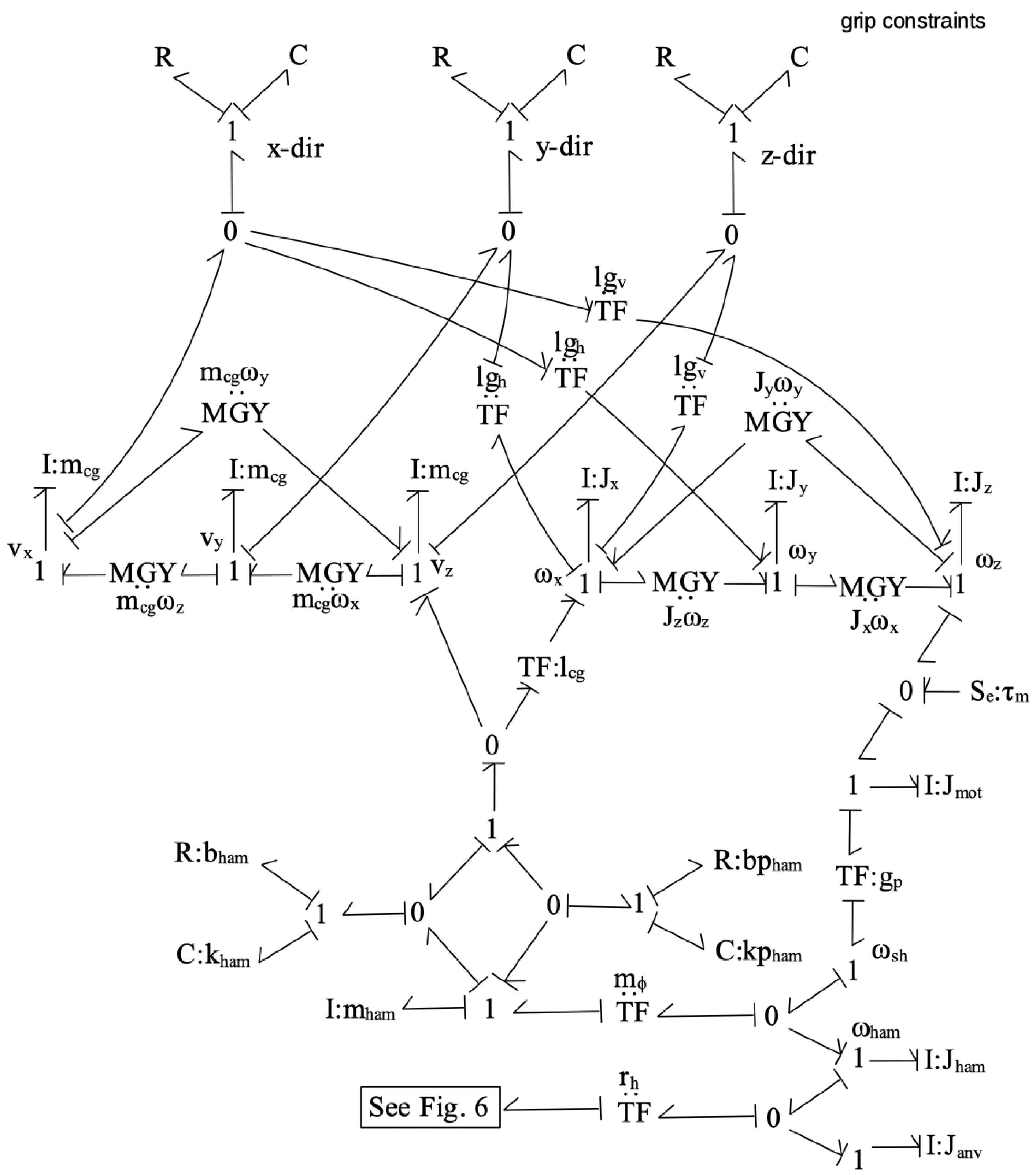

Figure 4 is a bond graph fragment for the rigid body dynamics of the tool as a whole. Body-fixed coordinates are used as indicated in

Figure 2. Gyroscopic coupling of the coordinates is considered, and small angular motions are assumed.

Figure 4.

Bond graph fragment of the rigid body dynamics using body fixed coordinates.

Figure 4.

Bond graph fragment of the rigid body dynamics using body fixed coordinates.

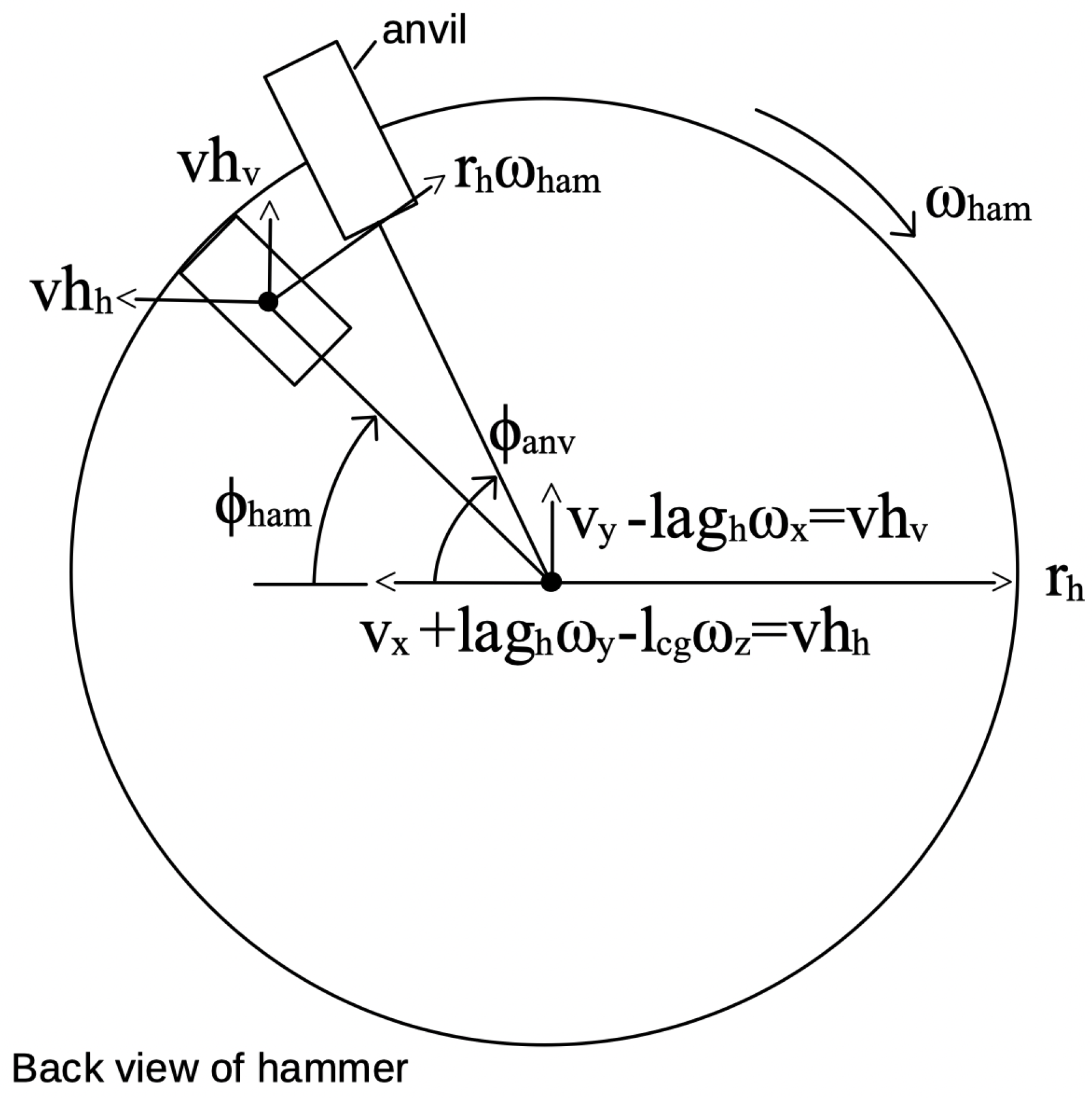

Figure 5 shows a back view of the hammer as it rotates towards the anvil. The velocity at the center of the hammer has been transferred from the center of gravity (CG) of the tool as indicated in

Figure 2. The horizontal and vertical center velocity components,

,

, are then transferred to the hammer tine and then aligned in the tangent direction. The difference in the tangent direction velocity of the hammer and tangent direction velocity of the anvil is the relative velocity across the impact spring and damper. This construction is shown in the bond graph fragment of

Figure 6.

In simulation, the hammer angle, , is tracked and when it is within 1of , impact is initiated. The impact advances the anvil depending on the retarding load specified on the anvil. Note that when testing the impact hammer, the anvil is often constrained to not move, i.e., the load on the anvil is infinite. This test condition is one of the simulations documented here.

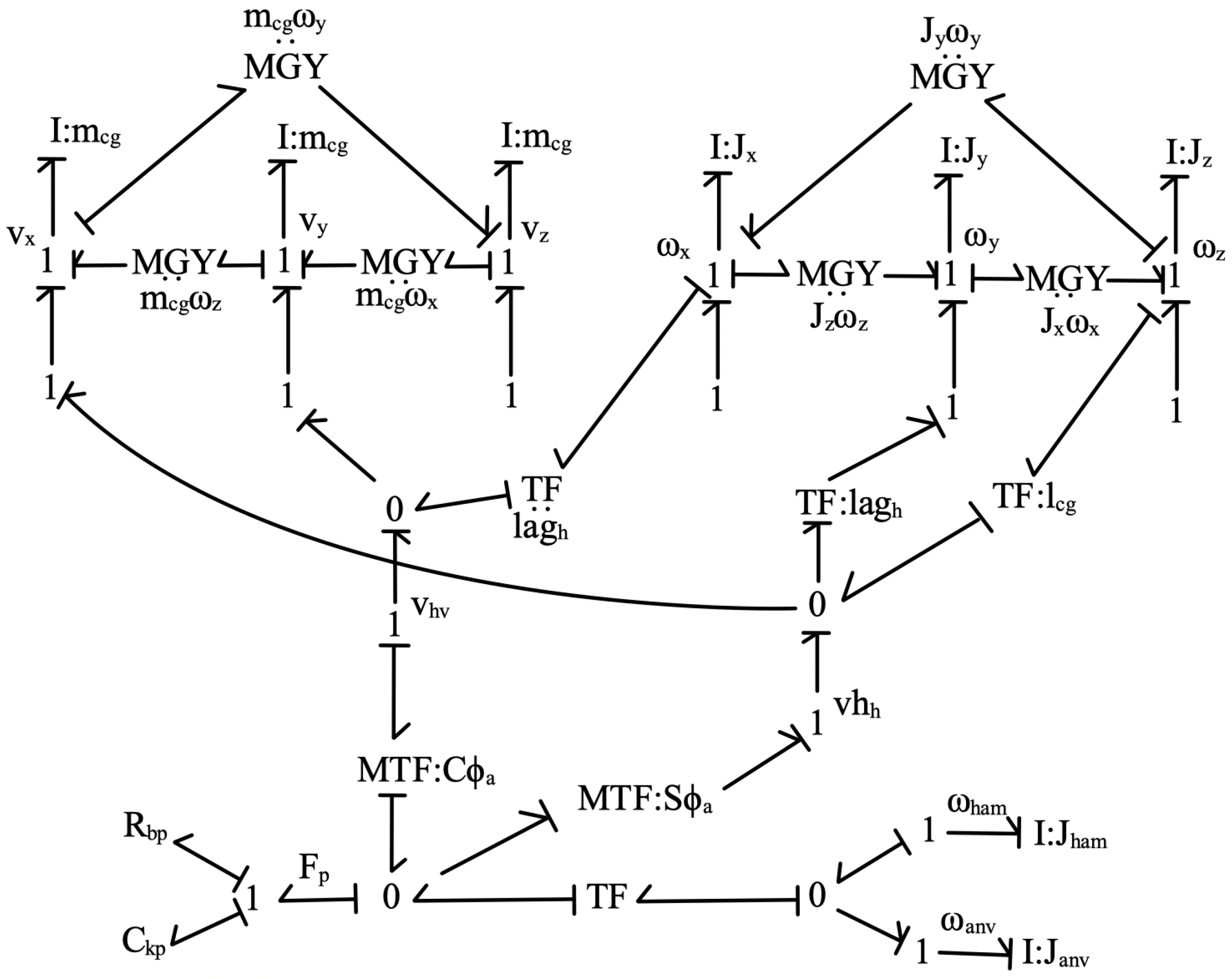

The bond graph fragment in

Figure 7 shows the motor/hammer interaction and uses a motor torque as the input to the motor inertia,

. In the simulation, a simple controller keeps the motor angular velocity,

, nearly constant unless motor control for vibration reduction was required. The motor angular velocity is reduced through the gearbox,

, and the difference between the shaft angular rate,

, and the hammer angular rate,

, determines the vertical velocity of the hammer and is an input to the hammer spring. This is represented by the transformer,

. At the bottom of

Figure 7 is the anvil inertia and this is where the bond graph fragment from

Figure 6 is attached.

Figure 7 also shows the interaction with the grip restraints indicated in

Figure 2. Not shown in

Figure 7 is the interaction with torsional constraints at the grip location and the restraints at the tip of the tool. The bond graph representation for these additional restraint elements is very similar to that for the grip constraints shown in

Figure 7.

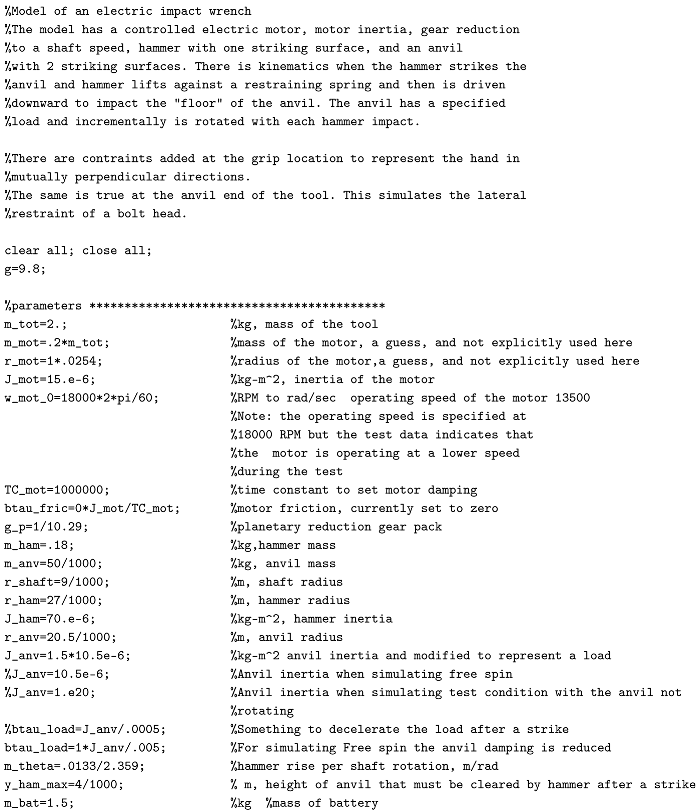

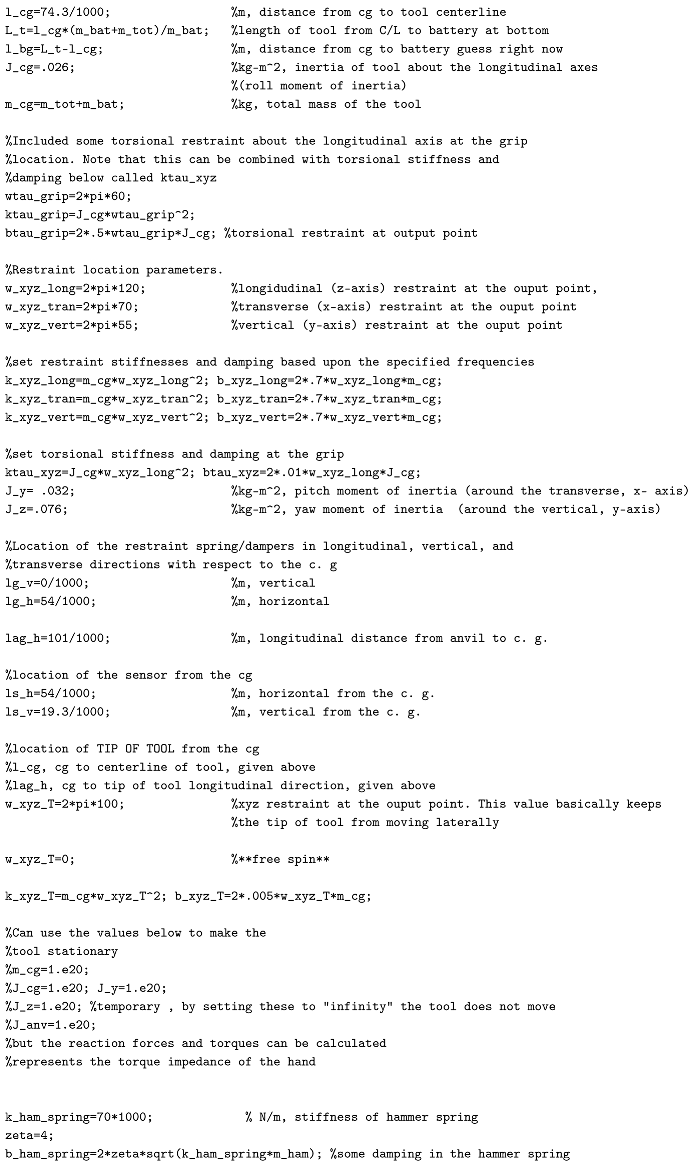

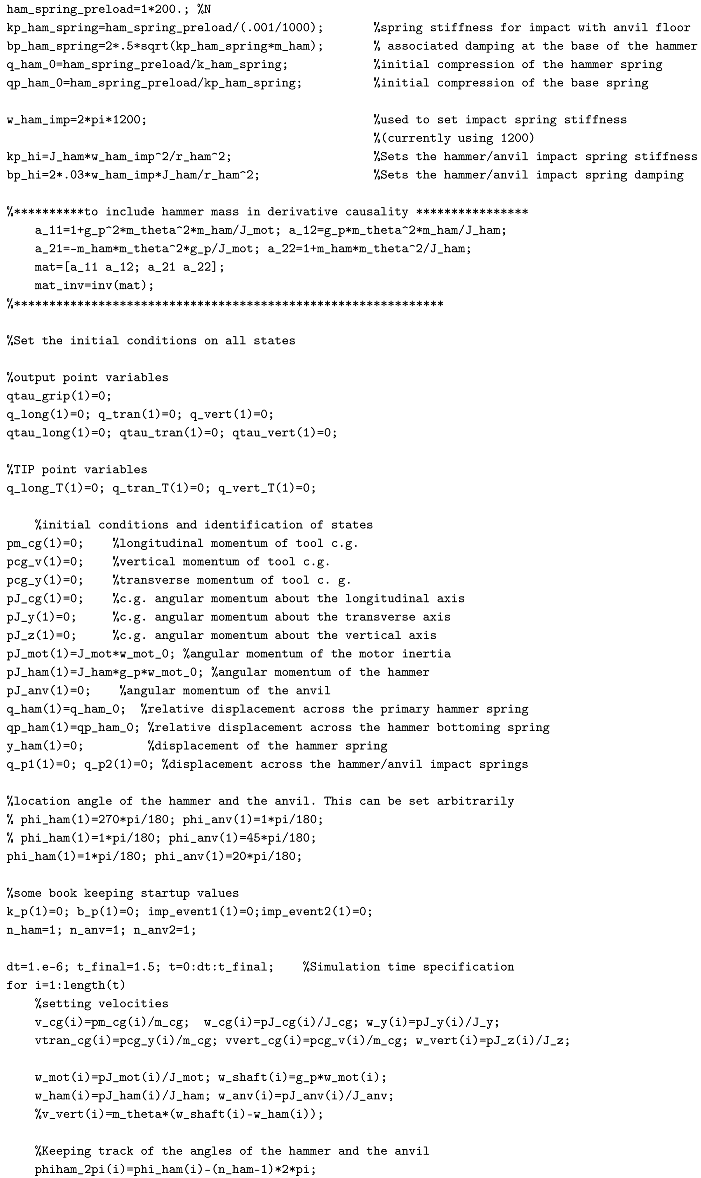

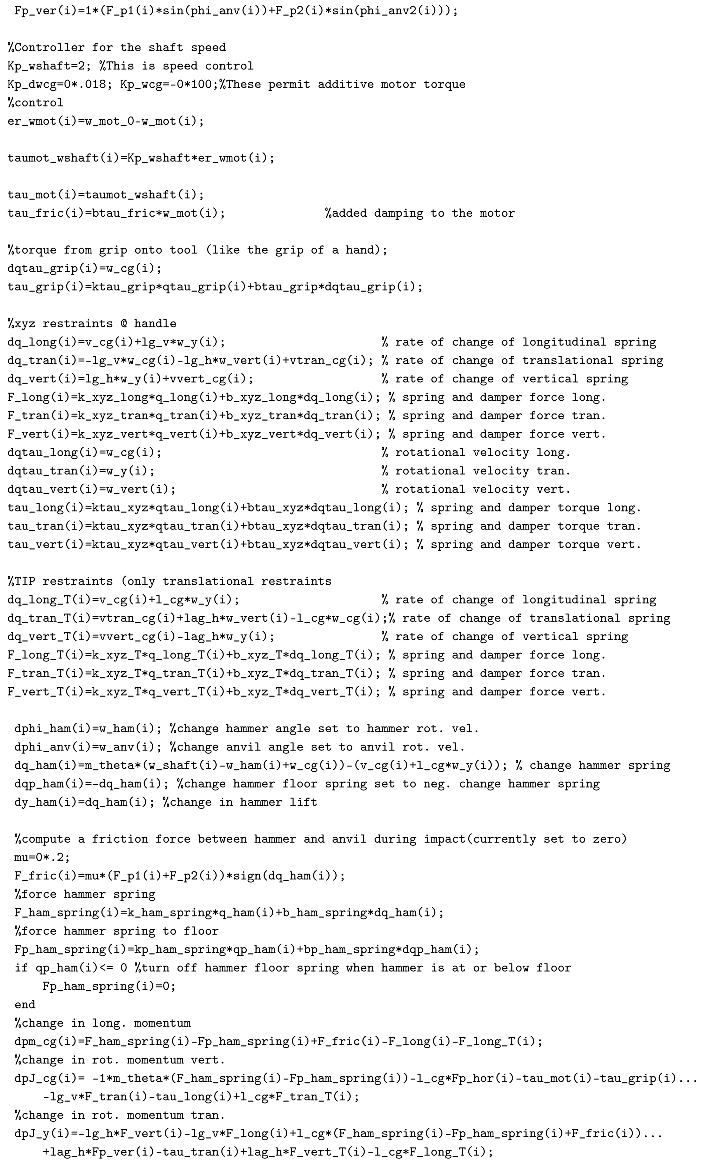

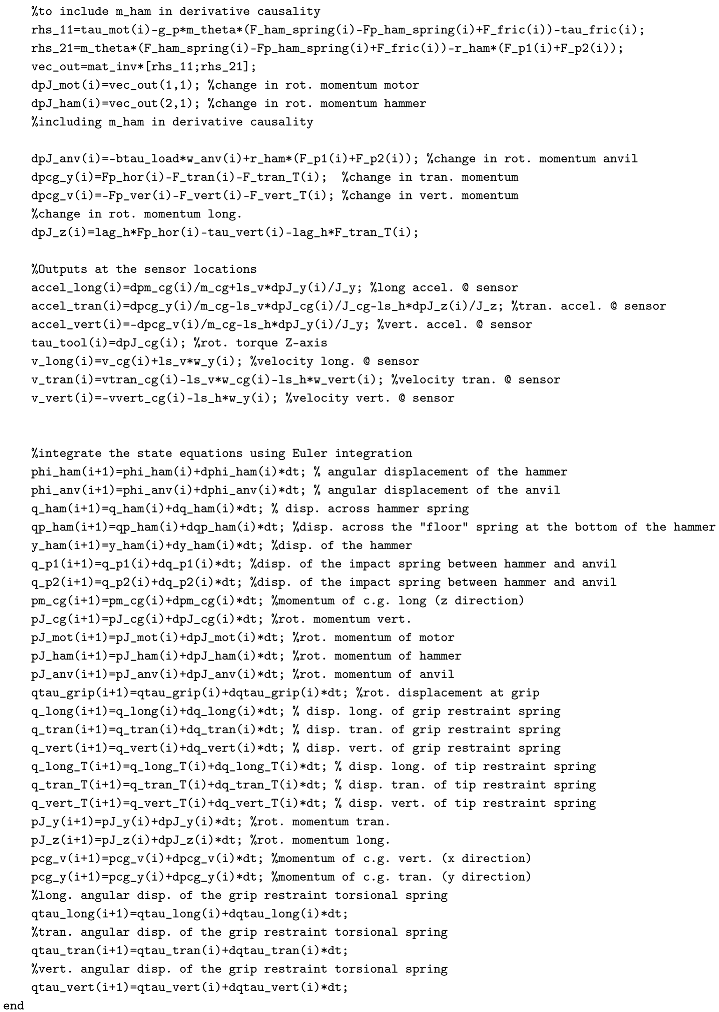

Causality has been assigned to the bond graph fragments of

Figure 4,

Figure 6, and

Figure 7 and the state variables are dictated by the energy storage elements (I’s and C’s) in integral form. The state variables are identified here as:

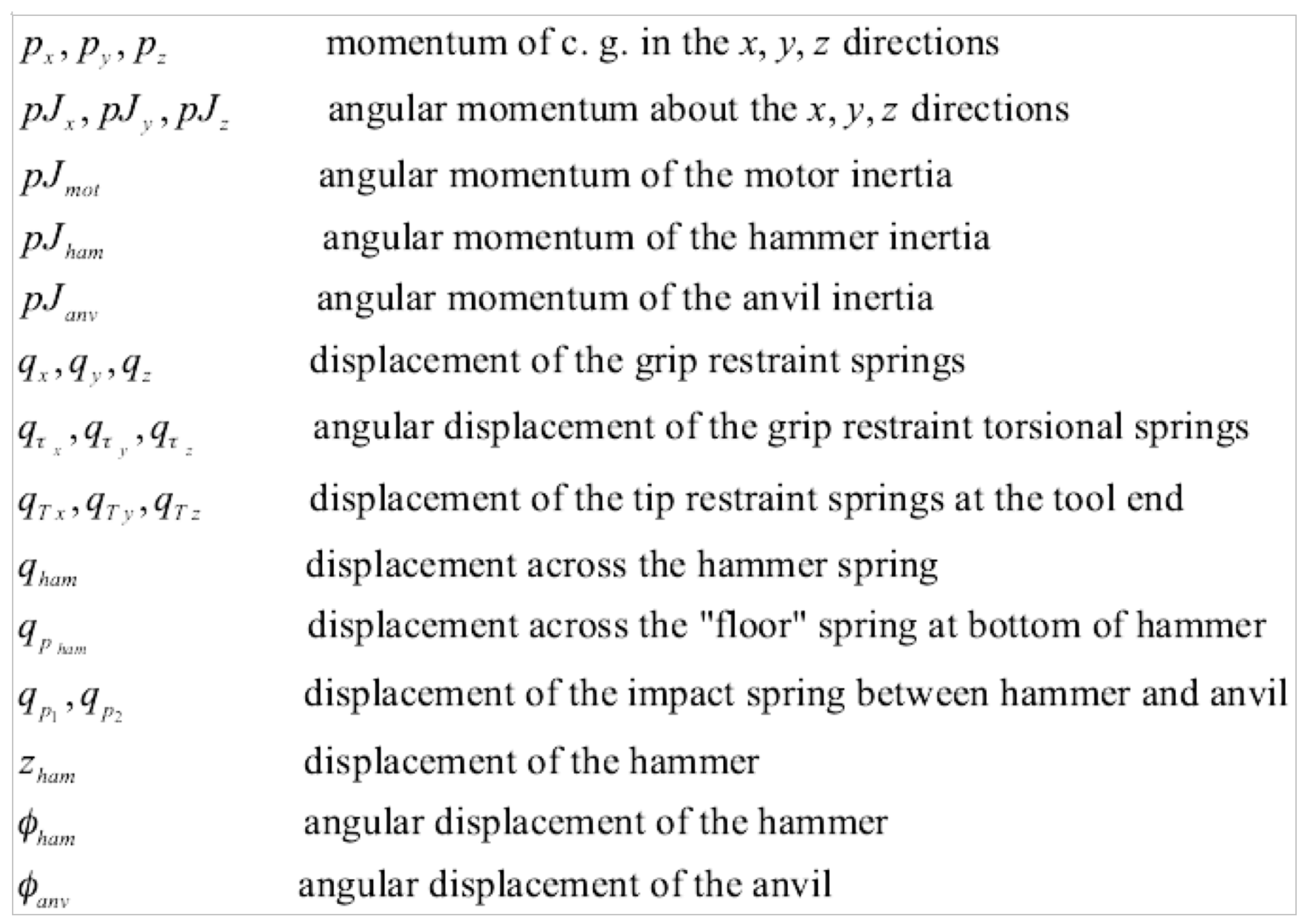

The first-order form of the state equations for these state variables is derived directly from the bond graph,

Figure 8. Collecting the states into a vector

and inputs (e.g., motor torque) into

, the model can be expressed in the standard first-order form

where

denotes the parameter set in

Table 1. Sample code of the model is given in Appendix A.

4. Results

The first-order state equations were simulated using MATLAB. Parameters were representative of an impact hammer such as a Milwaukee M18FHIWF12-502X or Hilti SIW 6AT-A22. A simple motor controller was implemented to maintain a prescribed rotational speed of 13,500 RPM. The parameters for the grip constraints were tuned as best as possible to be representative of the hand/arm stiffness and damping. The tuned parameters were in the range of common values found in the literature [

12].

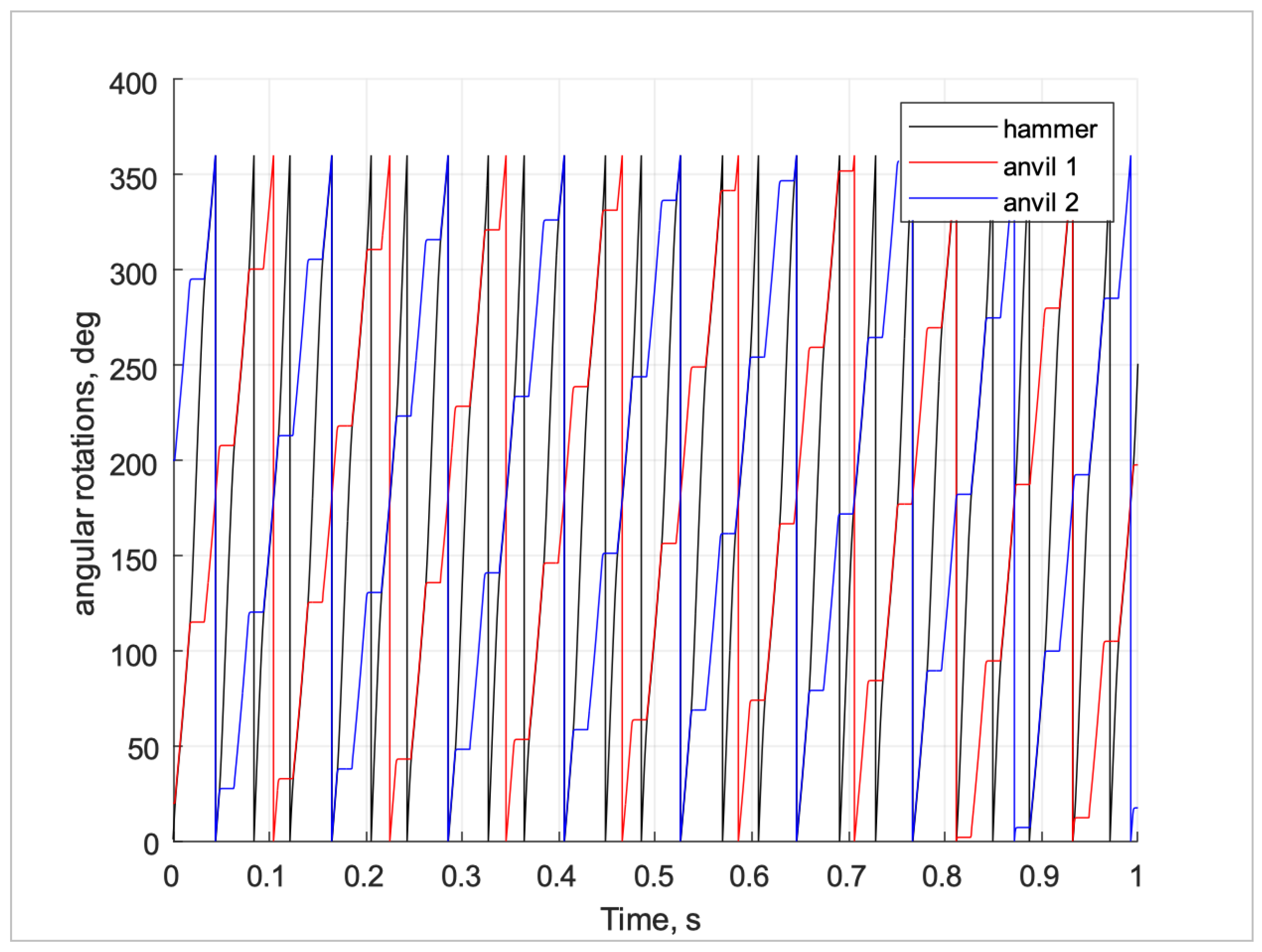

In the first simulation a load was prescribed that allowed the anvil to rotate and come to rest with each impact event.

Figure 9 shows the rotational angle of the hammer and the rotation of the anvil for the 2 impact events per full rotation of the hammer. This matches the expected interaction of the hammer and anvil teeth. The anvil teeth move in unison and they advance with the slope of the hammer movement.

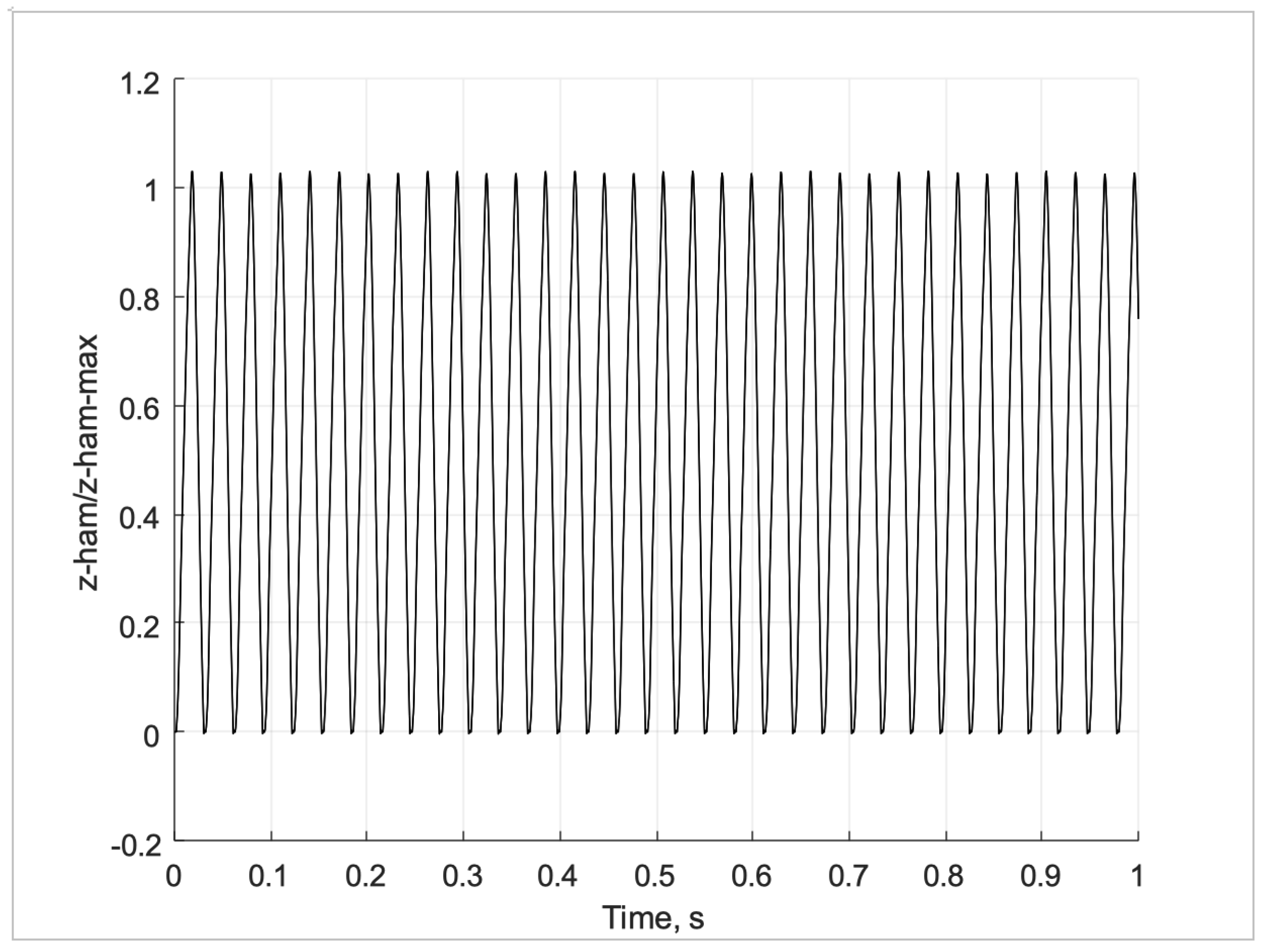

Figure 10 shows the longitudinal motion of the hammer that results from the impact events. At t = 0, the hammer strikes the anvil floor at height zero. Then the hammer rebounds just over 1 mm. This process repeats continuously at approximately 32 Hz. The tool was observed to run at 42Hz under zero load. After testing under load the tool was observed to run at 32Hz.

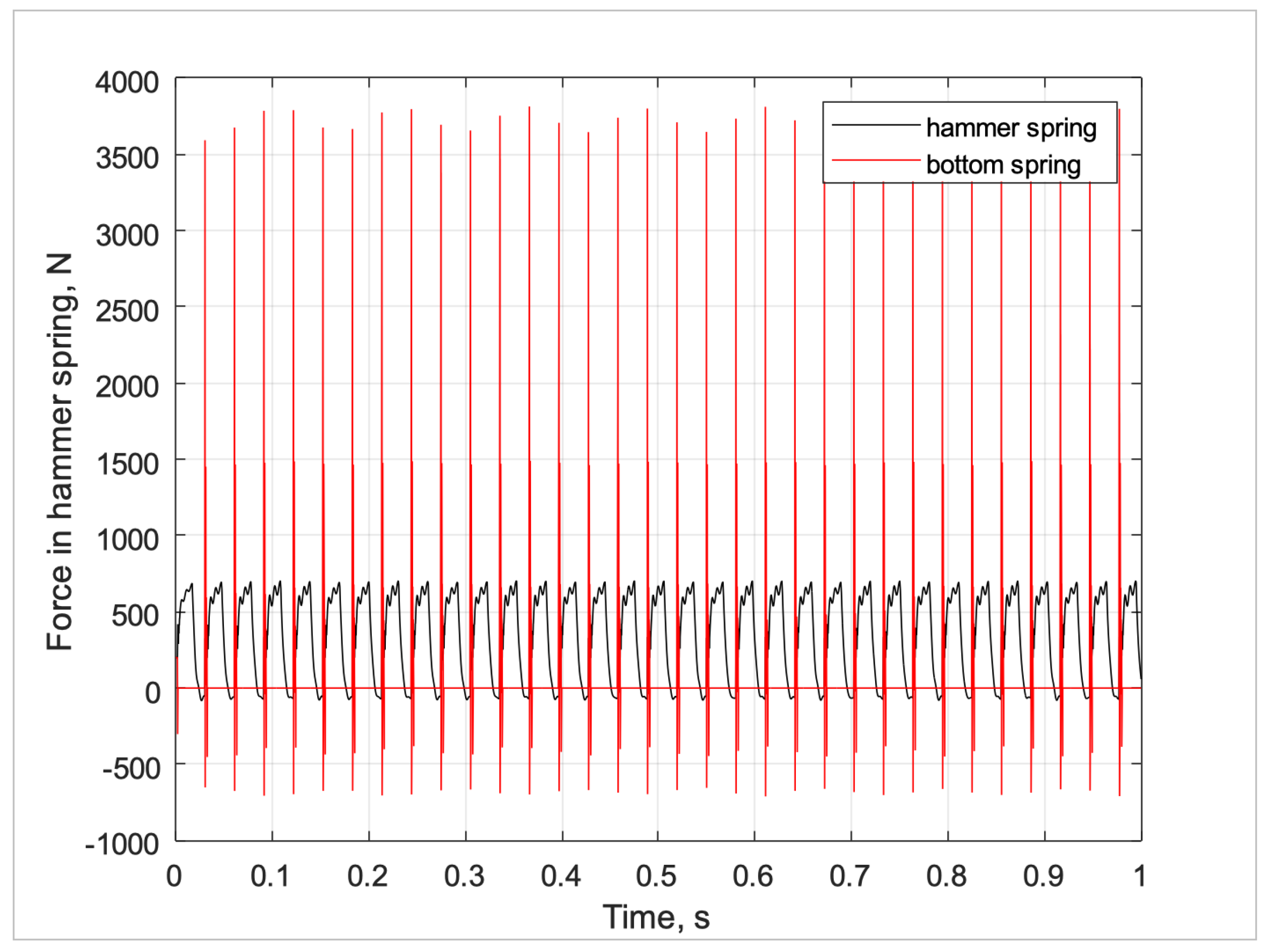

Figure 11 shows the impact forces in the hammer return spring and in the impact spring at the hammer floor. In this simulation, the impact with the floor produces much larger forces than the force due to raising and lowering of the hammer spring. For this simulation, the vibration felt by the operator is primarily due to the hammer ’bottoming’ rather than the compression of the hammer spring.

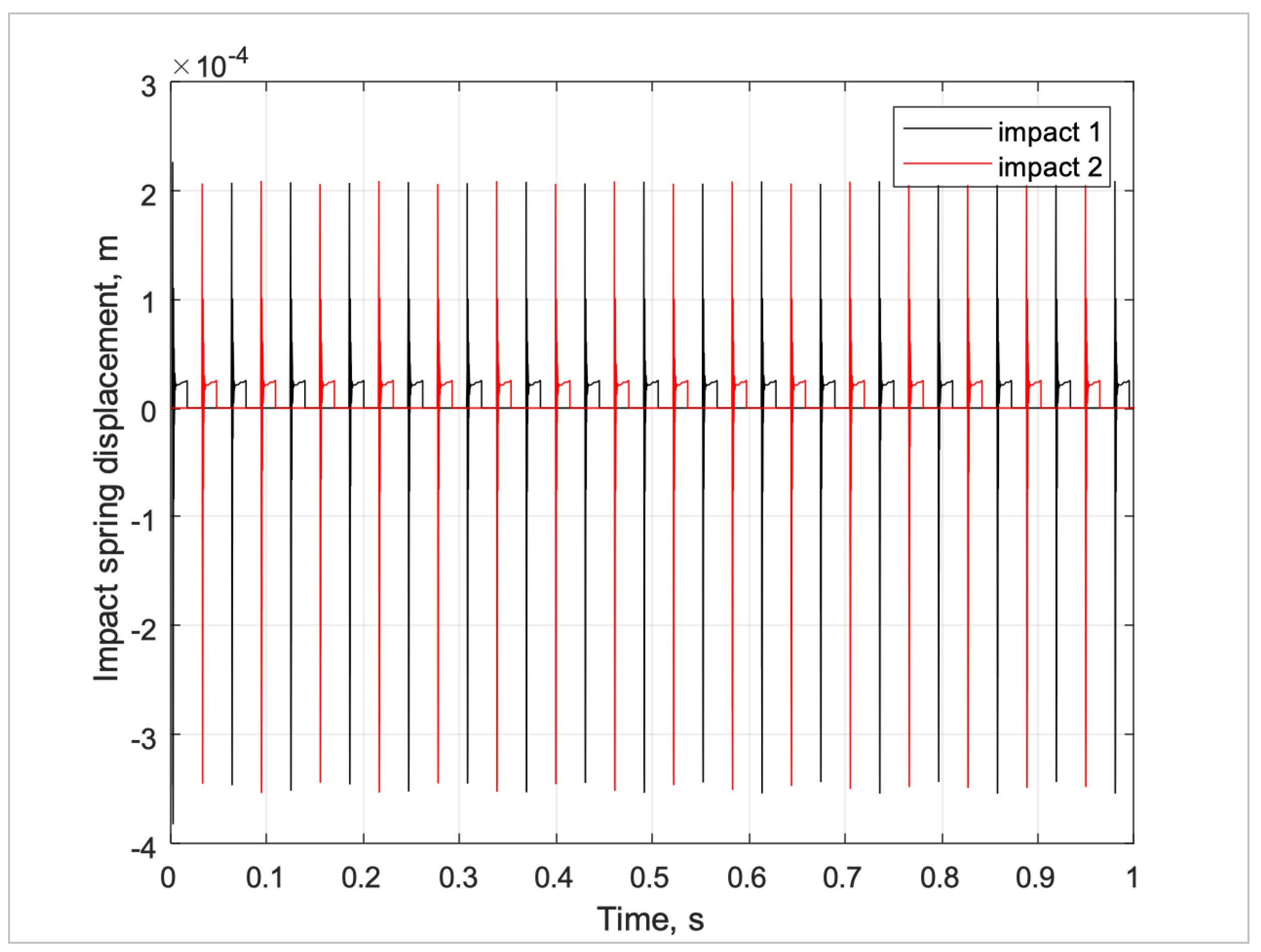

Figure 12 shows the impact spring displacement between the hammer and anvil. The displacement is a fraction of a millimeter. For the negative displacement the impact spring stiffness and damping are set to zero as can be seen in

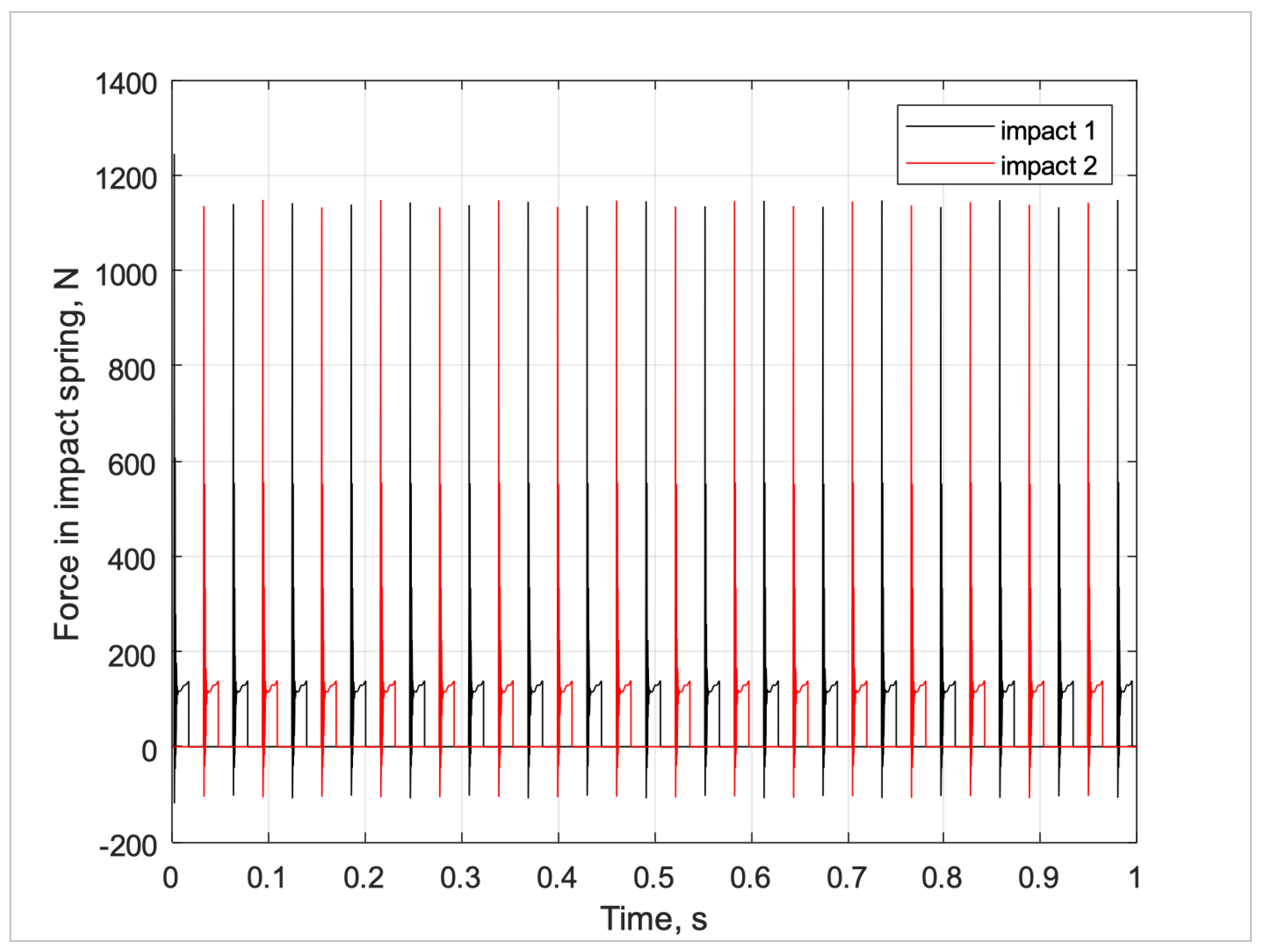

Figure 13 for the force in the impact spring.

In the next simulation, the anvil is held fixed and does not advance upon impact. This is considered to be the test configuration and is used here for model verification.

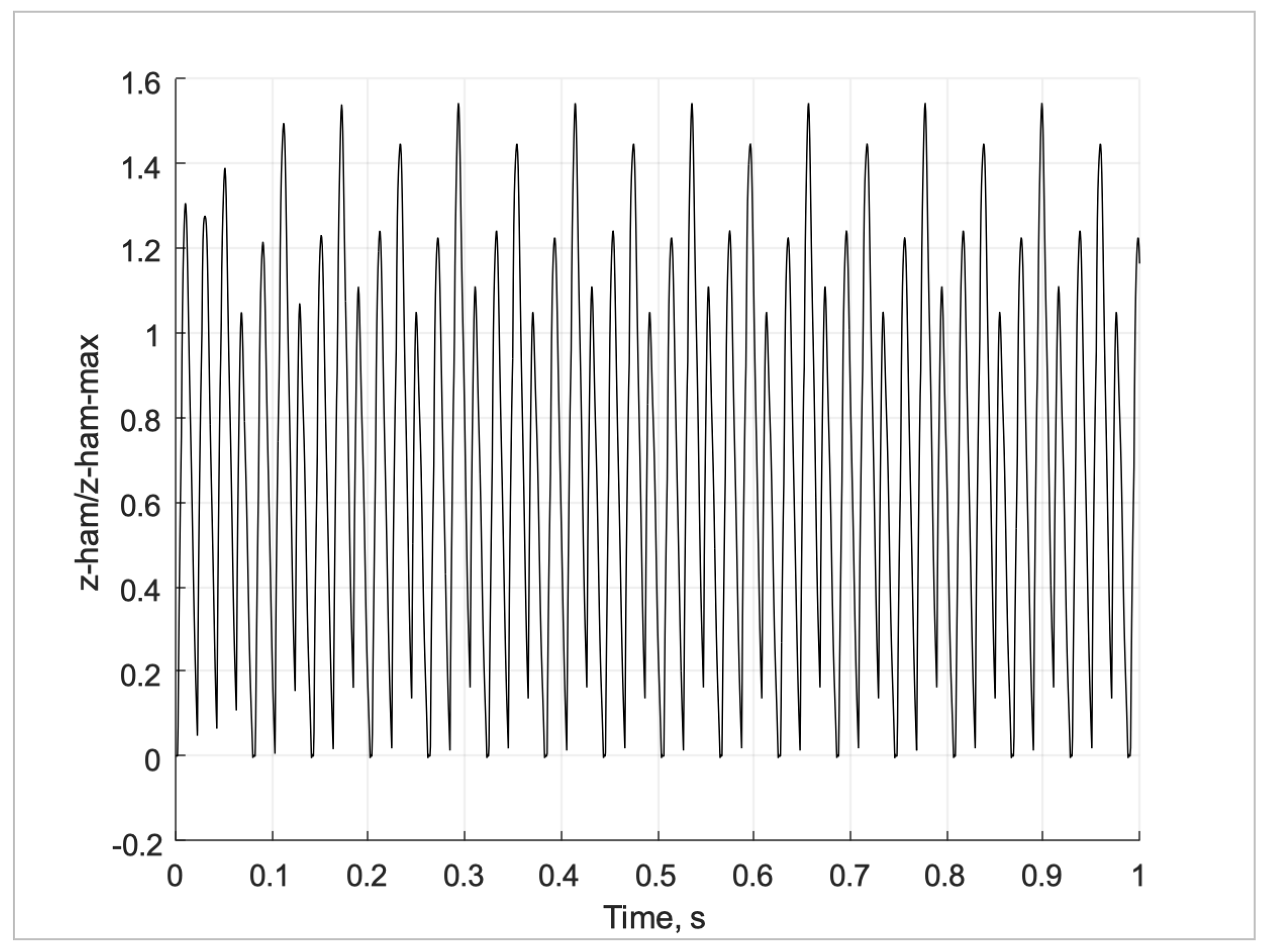

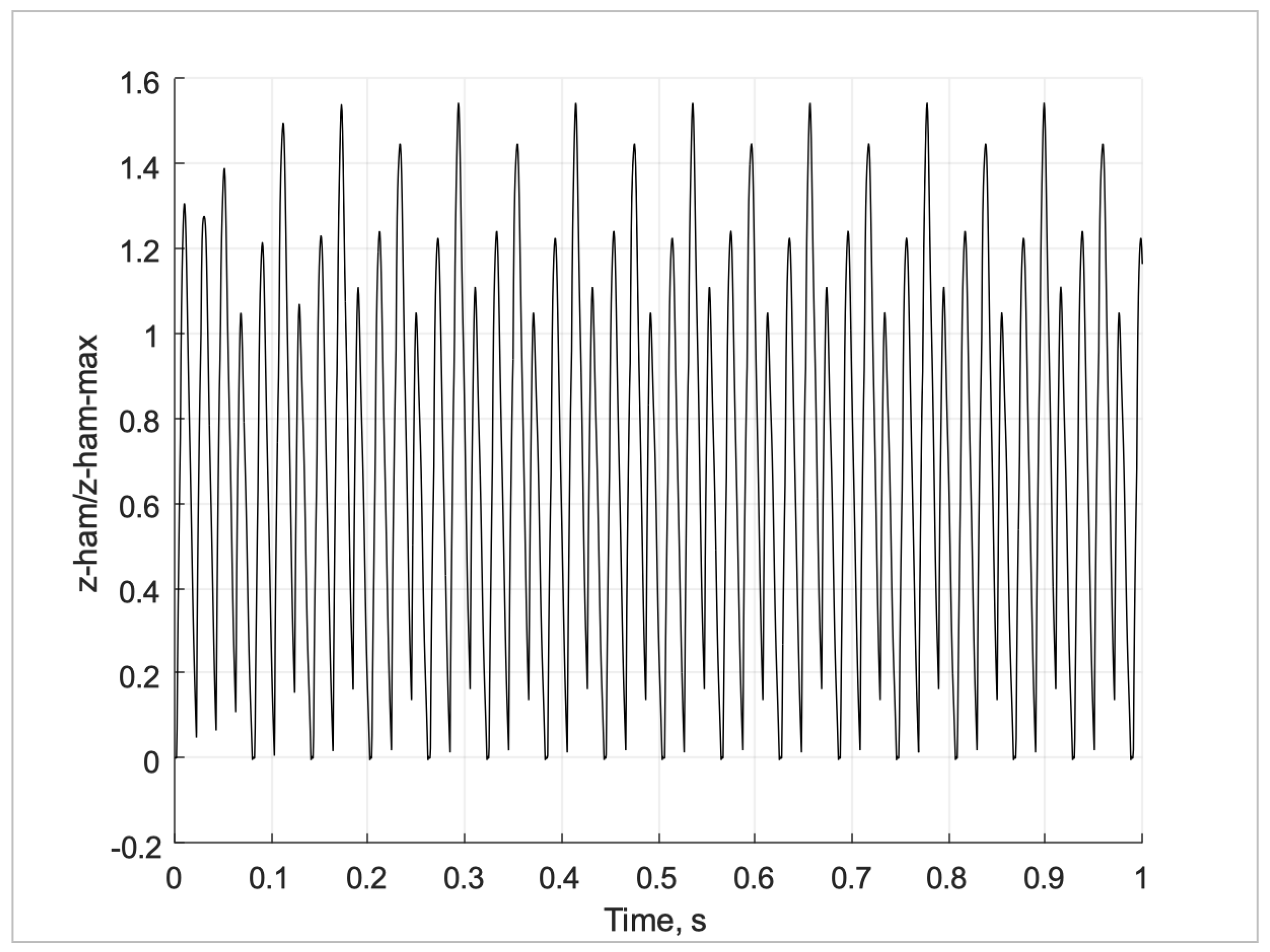

Figure 14 shows the z-direction, longitudinal motion of the hammer. In this simulation the hammer overshoots the anvil considerably and shows cycle to cycle variation.

Figure 15 shows the impact force between hammer and anvil for this test configuration. Comparing

Figure 15 to

Figure 13, the impact forces are much larger for the test configuration and much more erratic.

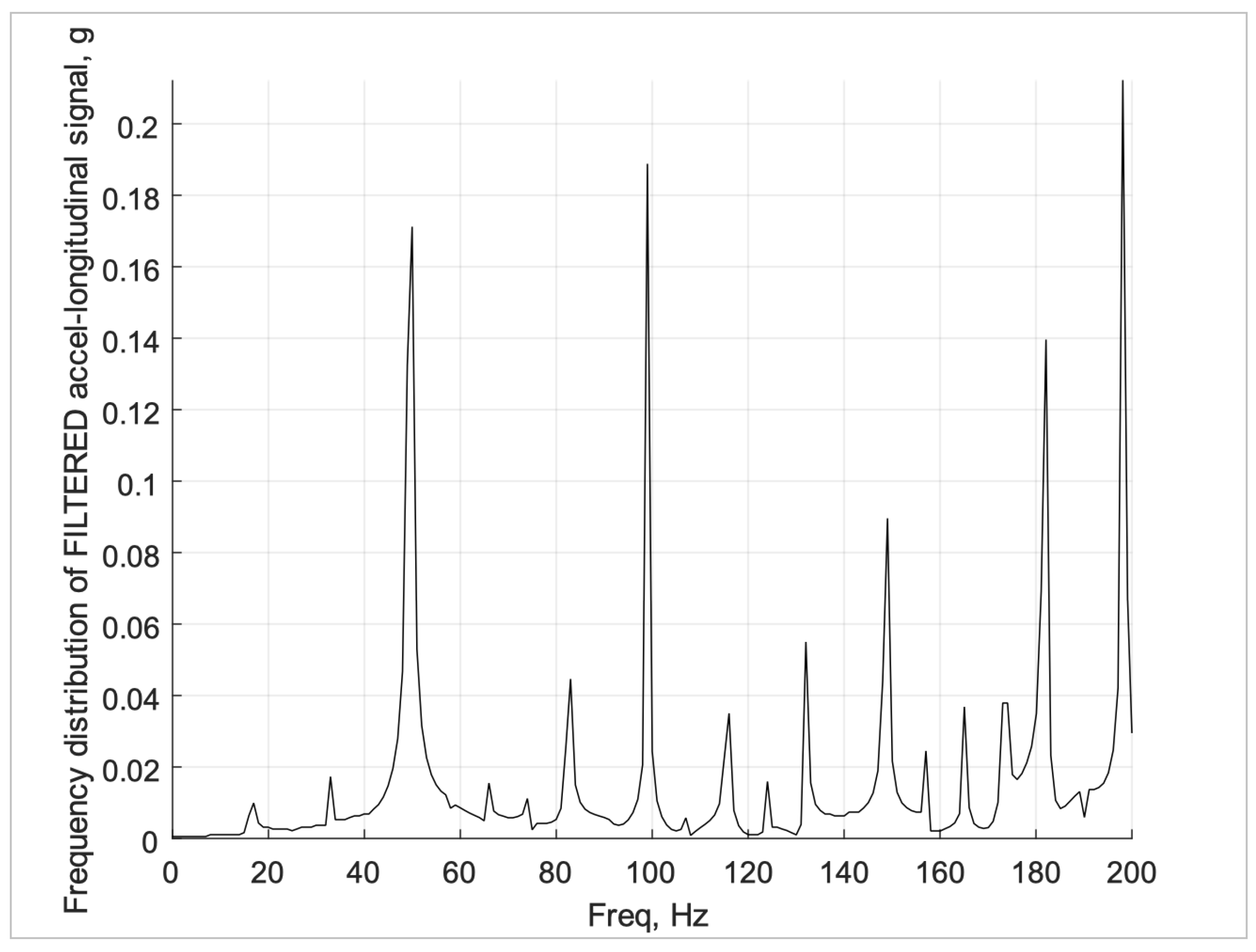

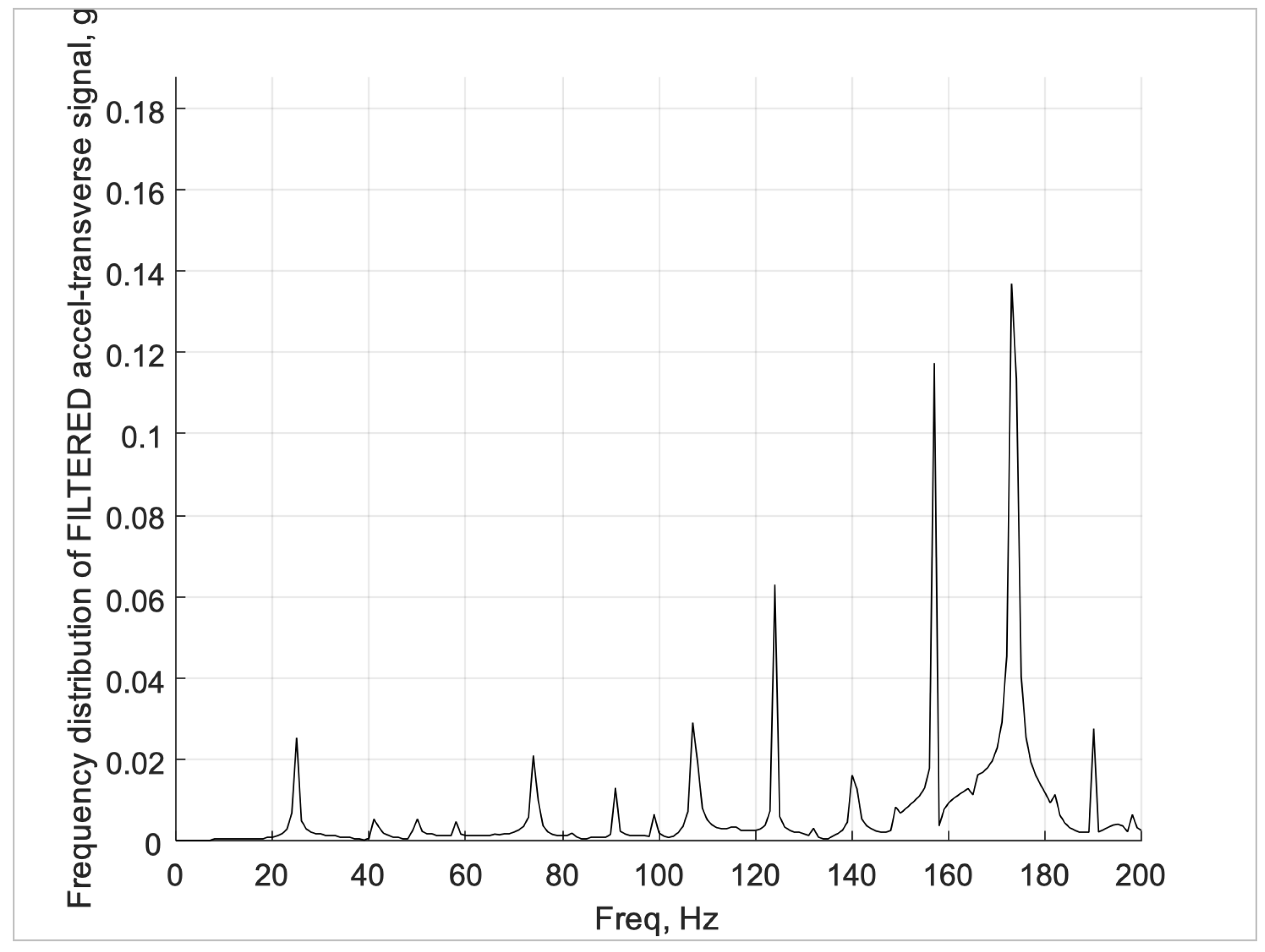

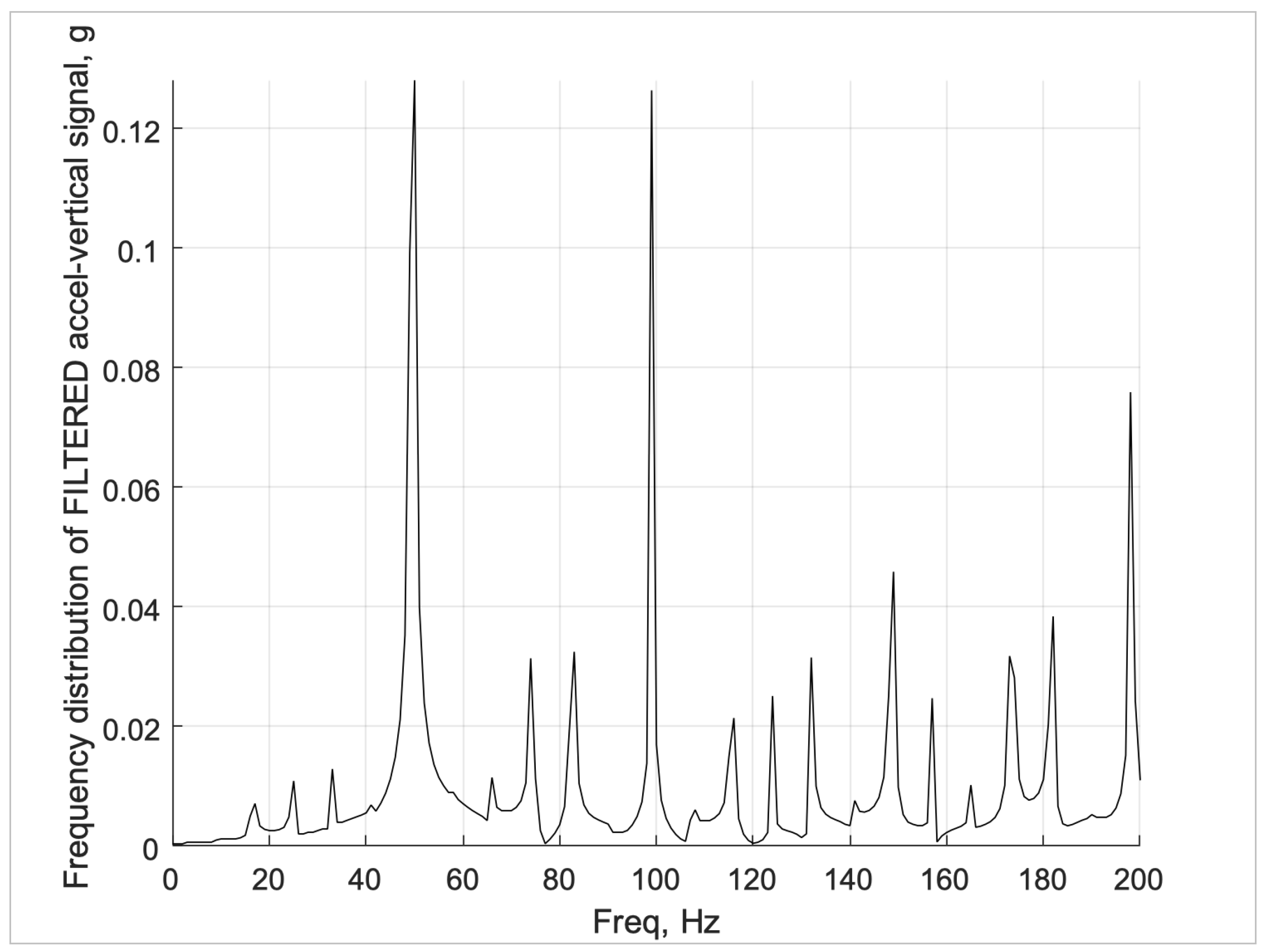

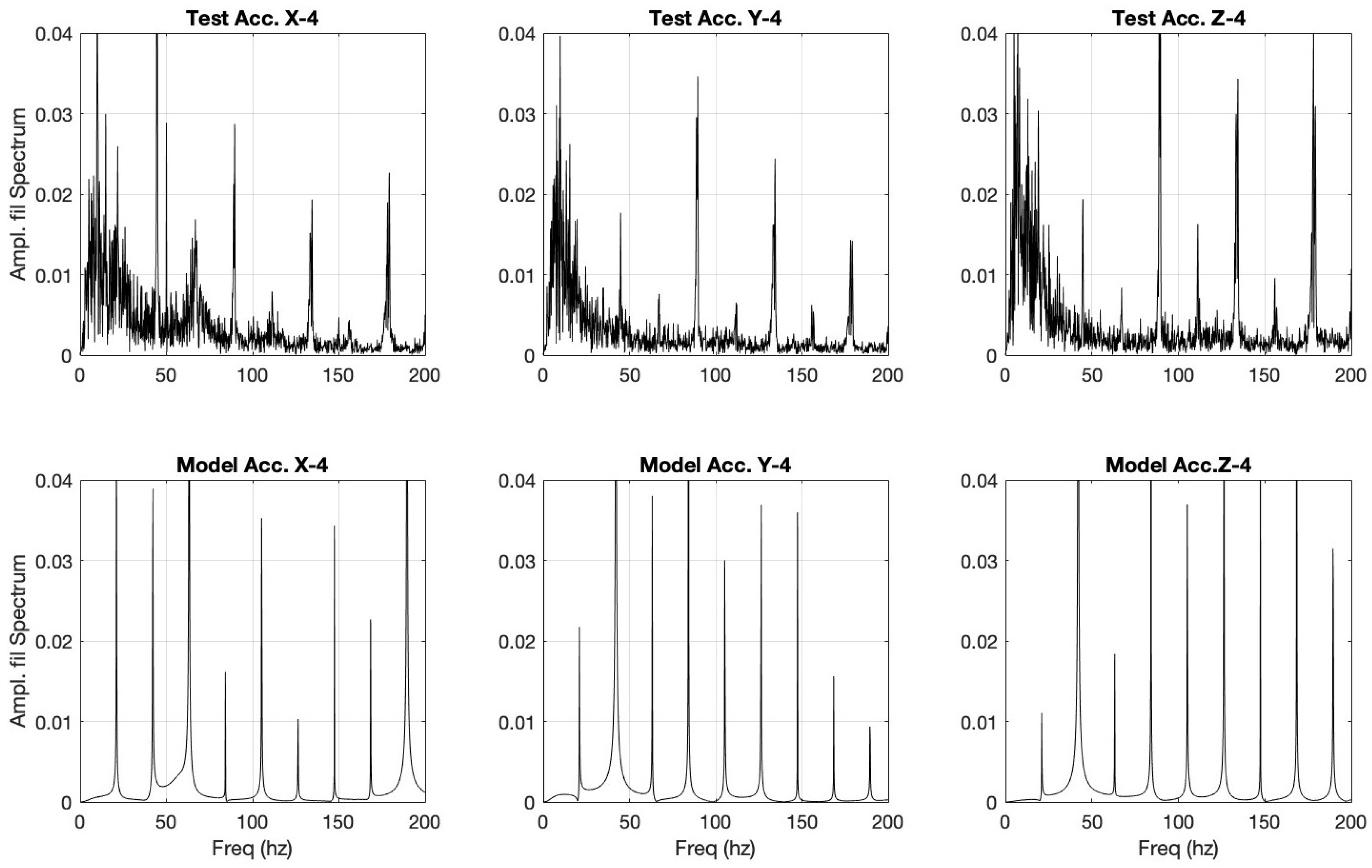

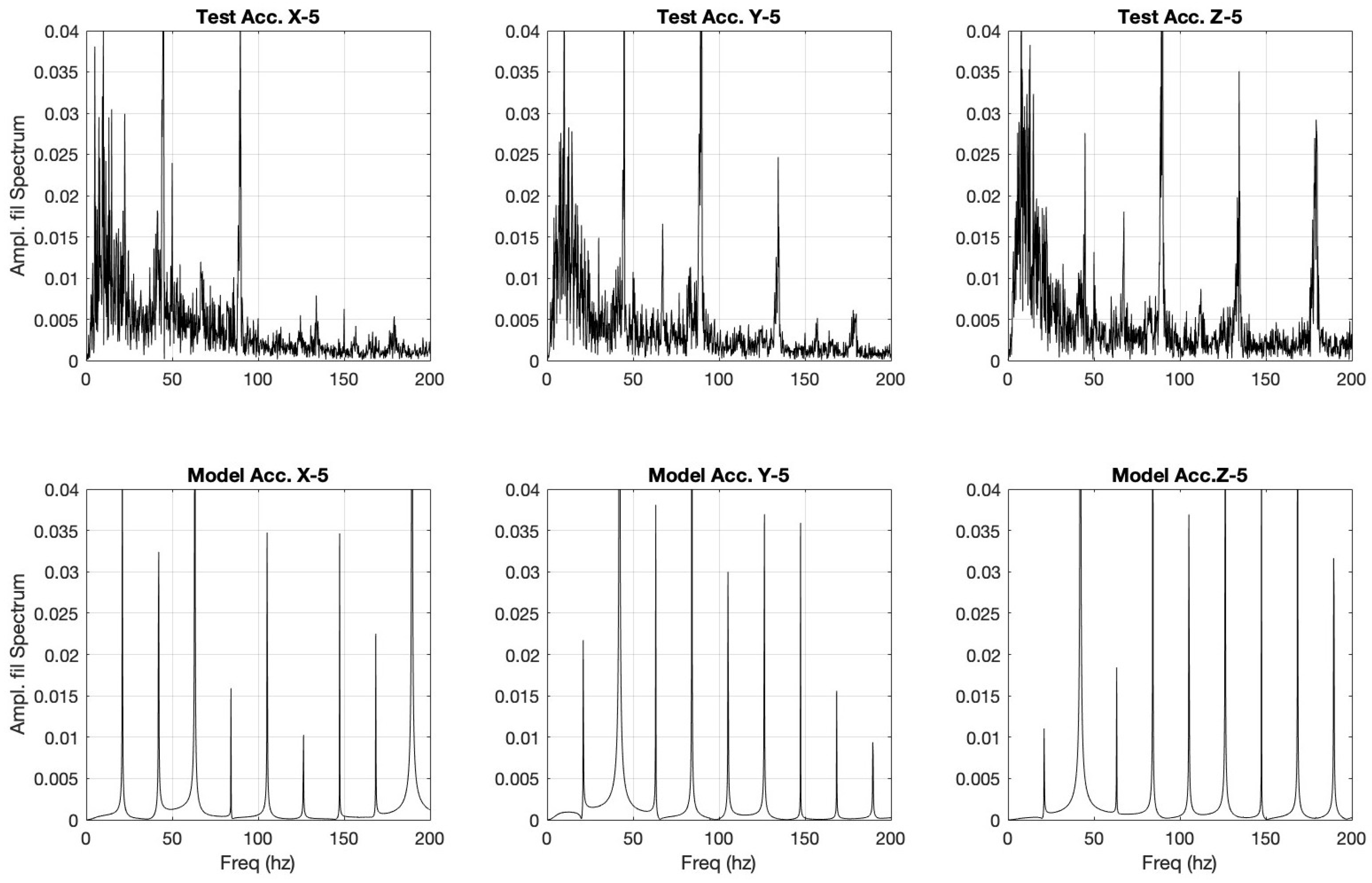

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

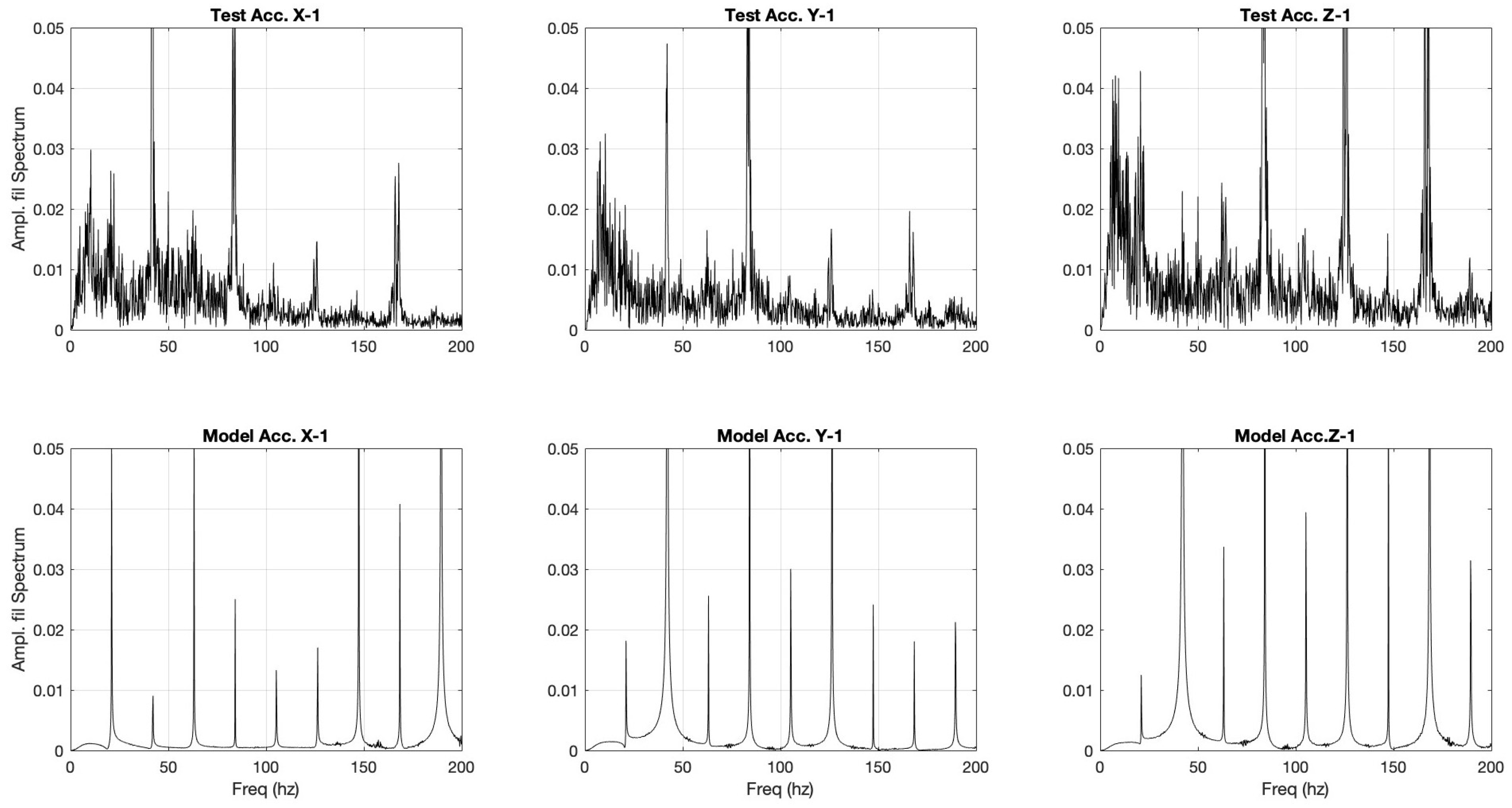

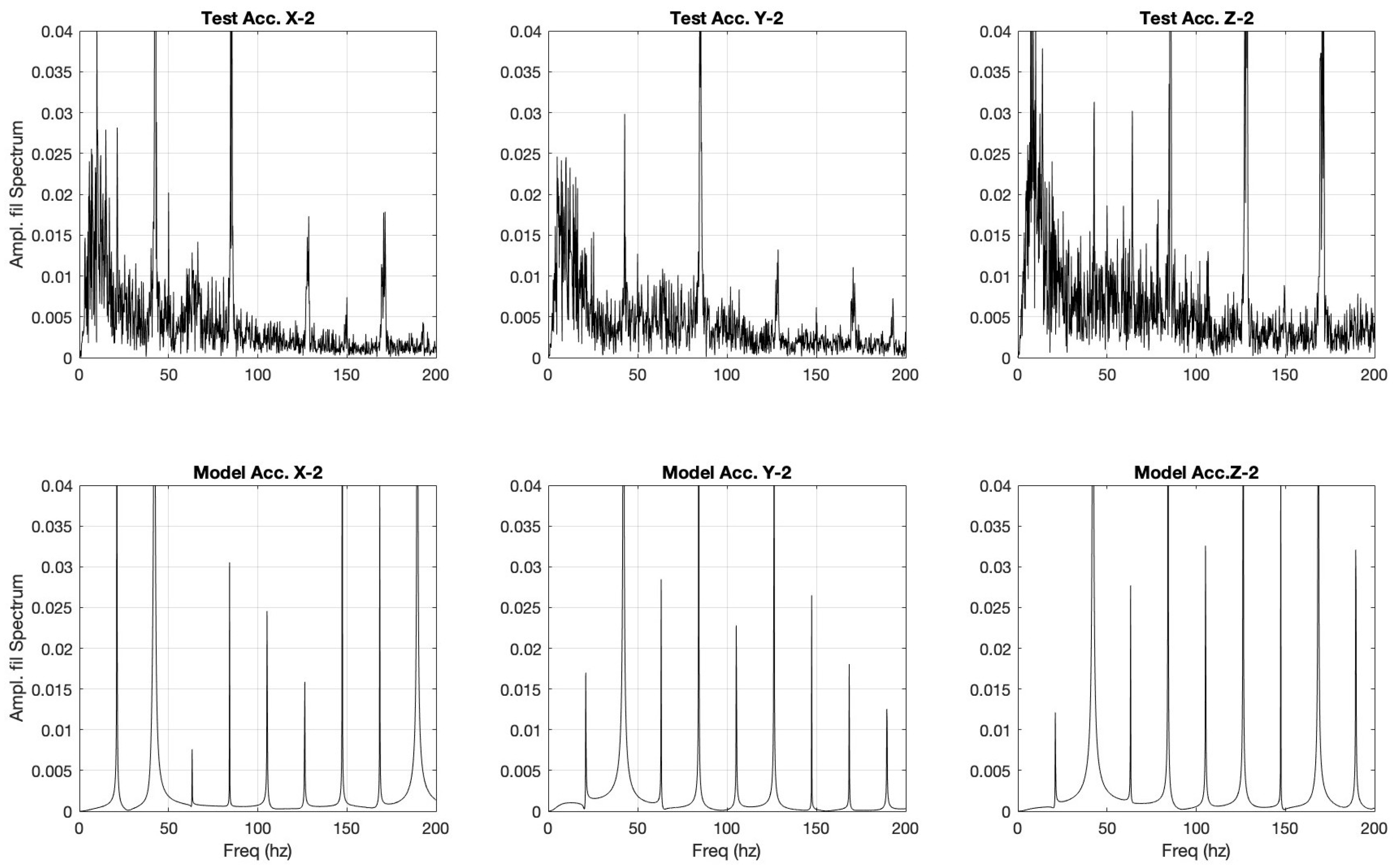

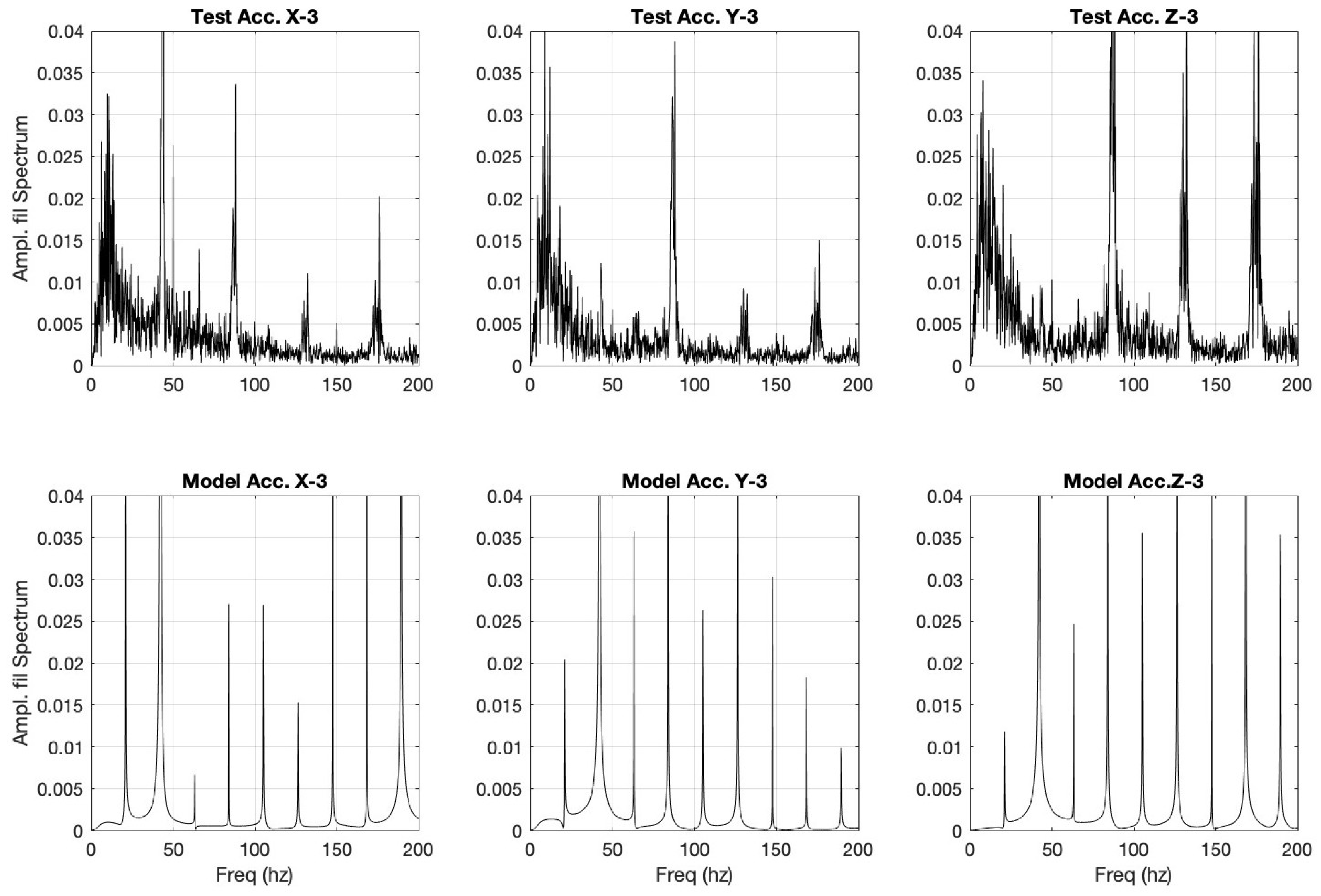

Figure 18 show the frequency decomposition of the acceleration predicted at the sensor location in the three orthogonal directions. The acceleration signal was low-pass filtered prior to computing the frequency distribution. This is typical of the signal processing done when testing impact tools.

Test data were available for an impact hammer. The comparisons to predictions are shown next.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of procedure.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of procedure.

Figure 2.

Schematic of impact hammer with coordinates and lengths identified.

Figure 2.

Schematic of impact hammer with coordinates and lengths identified.

Figure 3.

Schematic showing the internal dynamic elements of the impact hammer.

Figure 3.

Schematic showing the internal dynamic elements of the impact hammer.

Figure 5.

Back view of the hammer as it approaches the anvil for impact.

Figure 5.

Back view of the hammer as it approaches the anvil for impact.

Figure 6.

Bond graph fragment coupling the rigid body kinematics with the hammer/anvil interaction.

Figure 6.

Bond graph fragment coupling the rigid body kinematics with the hammer/anvil interaction.

Figure 7.

Bond graph fragment showing the dynamics of the hammer spring and the interaction with the hand/arm constraints.

Figure 7.

Bond graph fragment showing the dynamics of the hammer spring and the interaction with the hand/arm constraints.

Figure 8.

First order states.

Figure 8.

First order states.

Figure 9.

Angular rotation of the hammer and anvil due to repeated impact events.

Figure 9.

Angular rotation of the hammer and anvil due to repeated impact events.

Figure 10.

z-direction, longitudinal hammer motion resulting from the impact events.

Figure 10.

z-direction, longitudinal hammer motion resulting from the impact events.

Figure 11.

Force in the hammer spring and the ”floor” impact spring.

Figure 11.

Force in the hammer spring and the ”floor” impact spring.

Figure 12.

Displacement of the impact spring between hammer and anvil.

Figure 12.

Displacement of the impact spring between hammer and anvil.

Figure 13.

Force in the impact spring/damper between hammer and anvil.

Figure 13.

Force in the impact spring/damper between hammer and anvil.

Figure 14.

z-direction, longitudinal hammer motion resulting from the impact events for test configuration.

Figure 14.

z-direction, longitudinal hammer motion resulting from the impact events for test configuration.

Figure 15.

Impact force between hammer and anvil for the test configuration with anvil stationary.

Figure 15.

Impact force between hammer and anvil for the test configuration with anvil stationary.

Figure 16.

Frequency distribution of the longitudinal z-direction acceleration at the sensor location.

Figure 16.

Frequency distribution of the longitudinal z-direction acceleration at the sensor location.

Figure 17.

Frequency distribution of the transverse x-direction acceleration at the sensor location.

Figure 17.

Frequency distribution of the transverse x-direction acceleration at the sensor location.

Figure 18.

Frequency distribution of the vertical y-direction acceleration at the sensor location.

Figure 18.

Frequency distribution of the vertical y-direction acceleration at the sensor location.

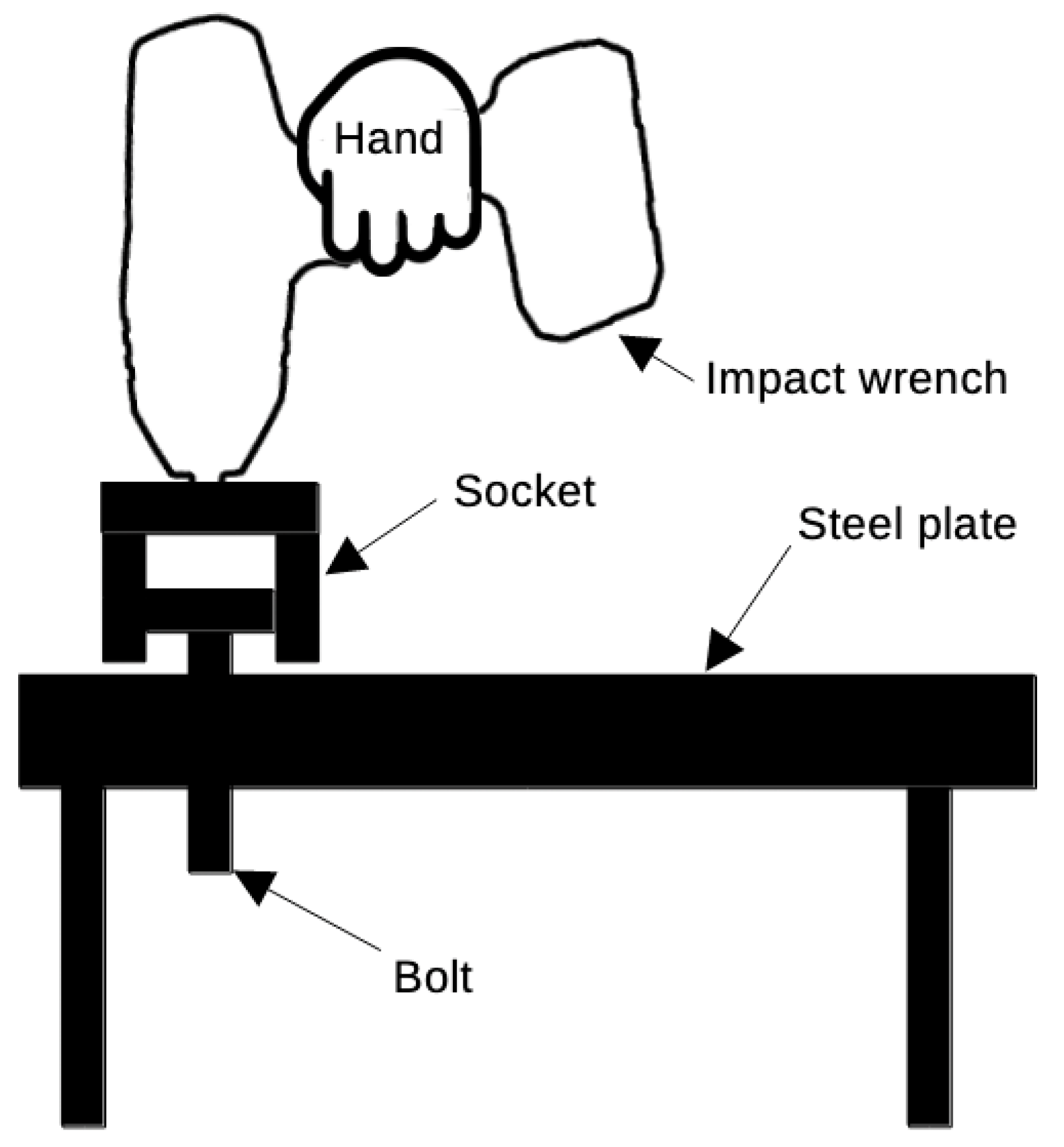

Figure 19.

Test setup layout.

Figure 19.

Test setup layout.

Figure 20.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 1.

Figure 20.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 1.

Figure 21.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 2.

Figure 21.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 2.

Figure 22.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 3.

Figure 22.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 3.

Figure 23.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 4.

Figure 23.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 4.

Figure 24.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 5.

Figure 24.

User test vs model tuned to user sample 5.

Table 1.

Key model parameters used in simulations.

Table 1.

Key model parameters used in simulations.

| Quantity |

Value |

| Motor nominal speed,

|

13 500 RPM (validated) |

| Gear ratio,

|

1/10.29 |

| Hammer mass,

|

0.18 kg |

| Hammer spring stiffness,

|

70 kN/m |

| Hammer spring damping ratio,

|

4 |

| Impact stiffness (hammer/anvil),

|

set via rad/s |

| Anvil inertia,

|

kg m2 (load-modified) |

| Grip translational frequencies (x,y,z) |

(70, 55, 120) Hz |

| Tip translational frequency |

0 Hz (free spin) |

Table 2.

RMS Accelerations User Tests (Fixed anvil during 5 second samples measured in g’s).

Table 2.

RMS Accelerations User Tests (Fixed anvil during 5 second samples measured in g’s).

| Sample # |

x-axis |

y-axis |

z-axis |

| 1 |

0.58 |

0.51 |

0.88 |

| 2 |

0.59 |

0.40 |

0.65 |

| 3 |

0.65 |

0.46 |

0.61 |

| 4 |

0.53 |

0.40 |

0.49 |

| 5 |

0.47 |

0.43 |

0.51 |

Table 3.

Model User Parameters (Hz): Frequency tuning values for each model for each test sample.

Table 3.

Model User Parameters (Hz): Frequency tuning values for each model for each test sample.

| Sample # |

x-axis |

y-axis |

z-axis |

| 1 |

17 |

30 |

60 |

| 2 |

2 |

42 |

90 |

| 3 |

2 |

34 |

95 |

| 4 |

9 |

38 |

132 |

| 5 |

17 |

38 |

132 |

Table 4.

RMS Accelerations Model Simulations (Fixed anvil during 5 second samples measured in g’s).

Table 4.

RMS Accelerations Model Simulations (Fixed anvil during 5 second samples measured in g’s).

| Sample # |

x-axis |

y-axis |

z-axis |

| 1 |

0.57 |

0.51 |

0.93 |

| 2 |

0.59 |

0.41 |

0.72 |

| 3 |

0.62 |

0.48 |

0.68 |

| 4 |

0.52 |

0.40 |

0.52 |

| 5 |

0.47 |

0.40 |

0.52 |

Table 5.

Errors between User tests and model simulations (Fixed anvil during 5 seconds measured in g’s).

Table 5.

Errors between User tests and model simulations (Fixed anvil during 5 seconds measured in g’s).

| Sample # |

x-axis |

y-axis |

z-axis |

| 1 |

-0.02 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

| 2 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

0.11 |

| 3 |

-0.05 |

-0.02 |

0.00 |

| 4 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

| 5 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.02 |