Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

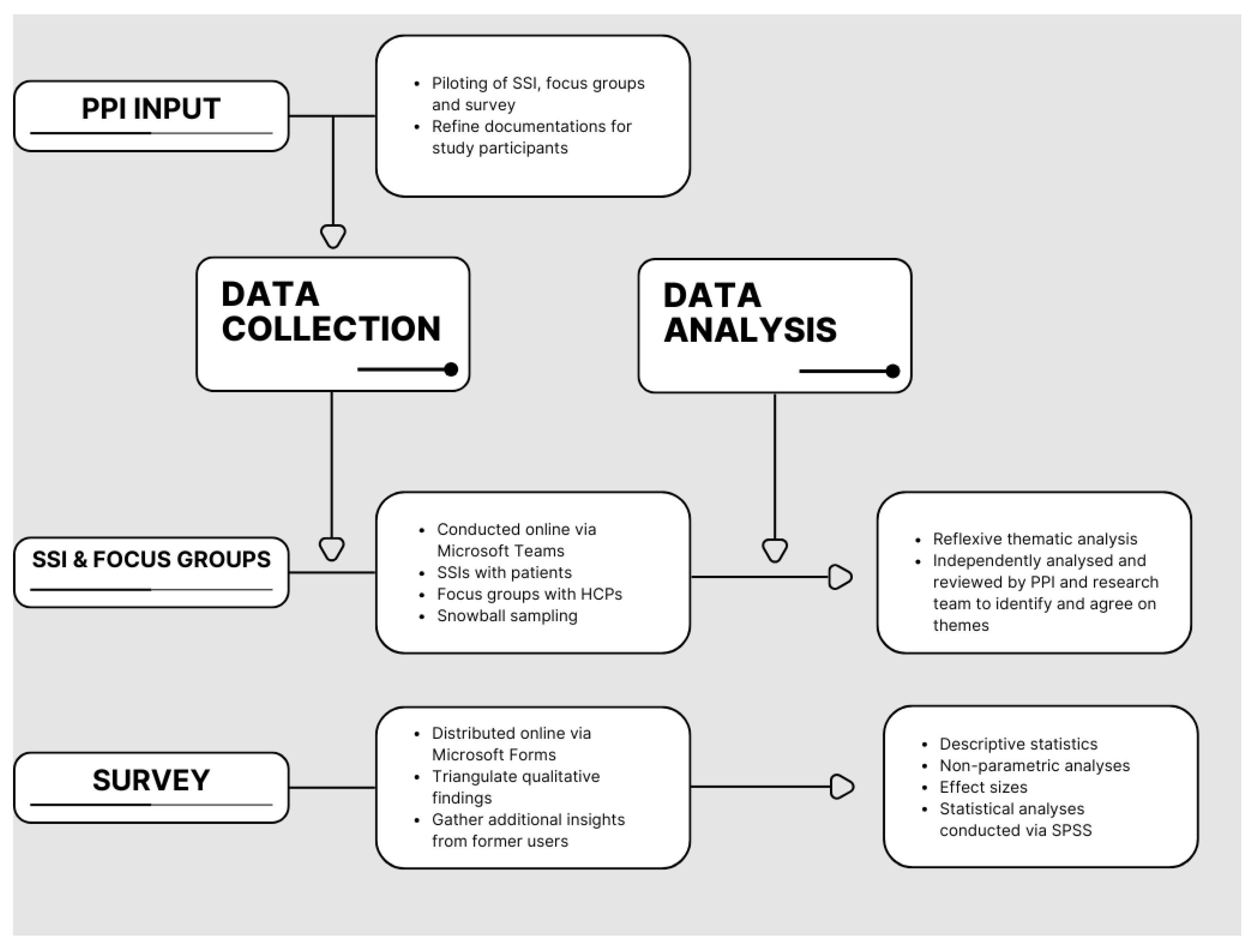

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Qualitative Data Collection and Data Analysis

2.3. Survey Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Research Group Characteristics and Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Results

3.1.1. Participant Characteristics

3.1.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.2.1. Participant Characteristics

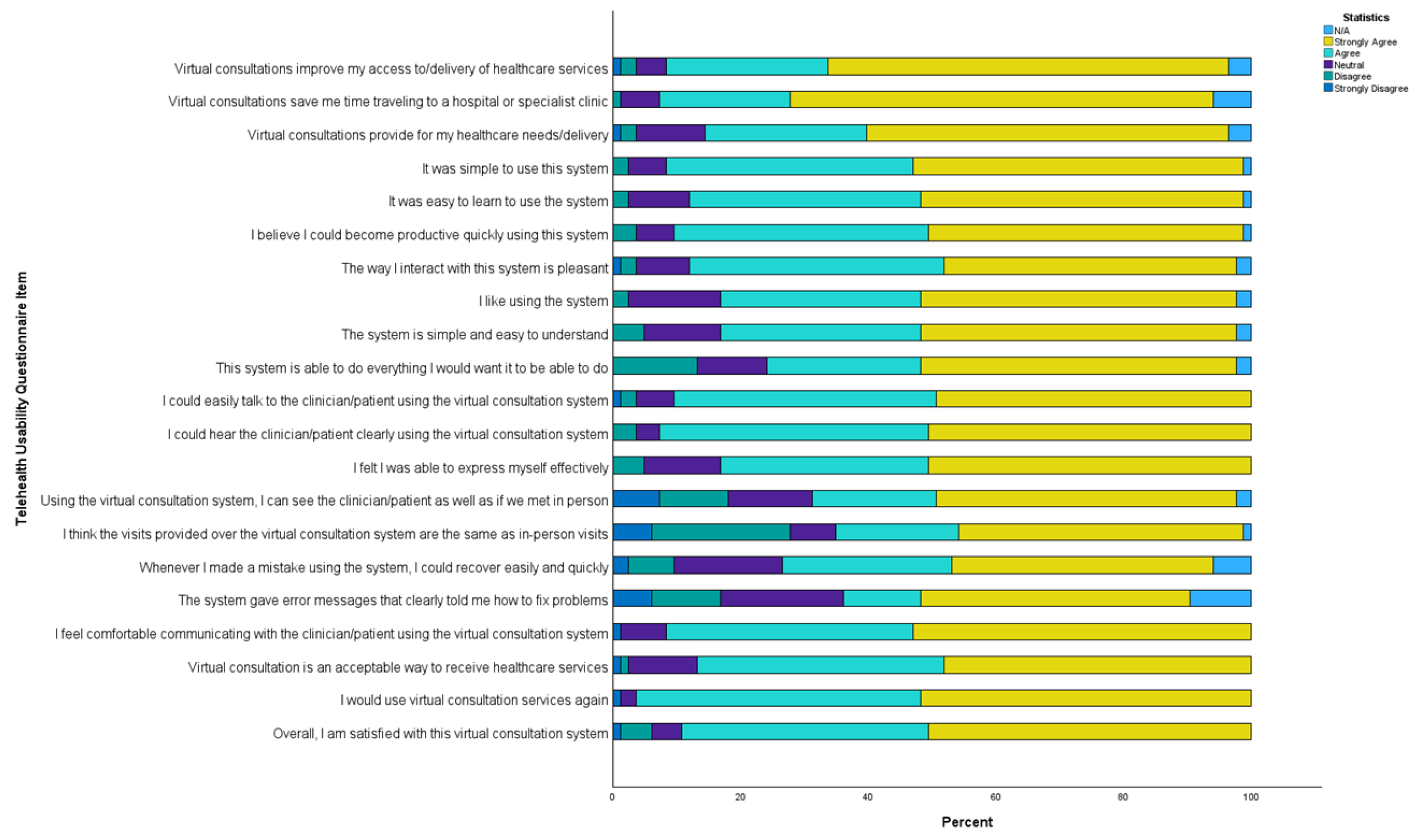

3.2.2. TUQ analyses

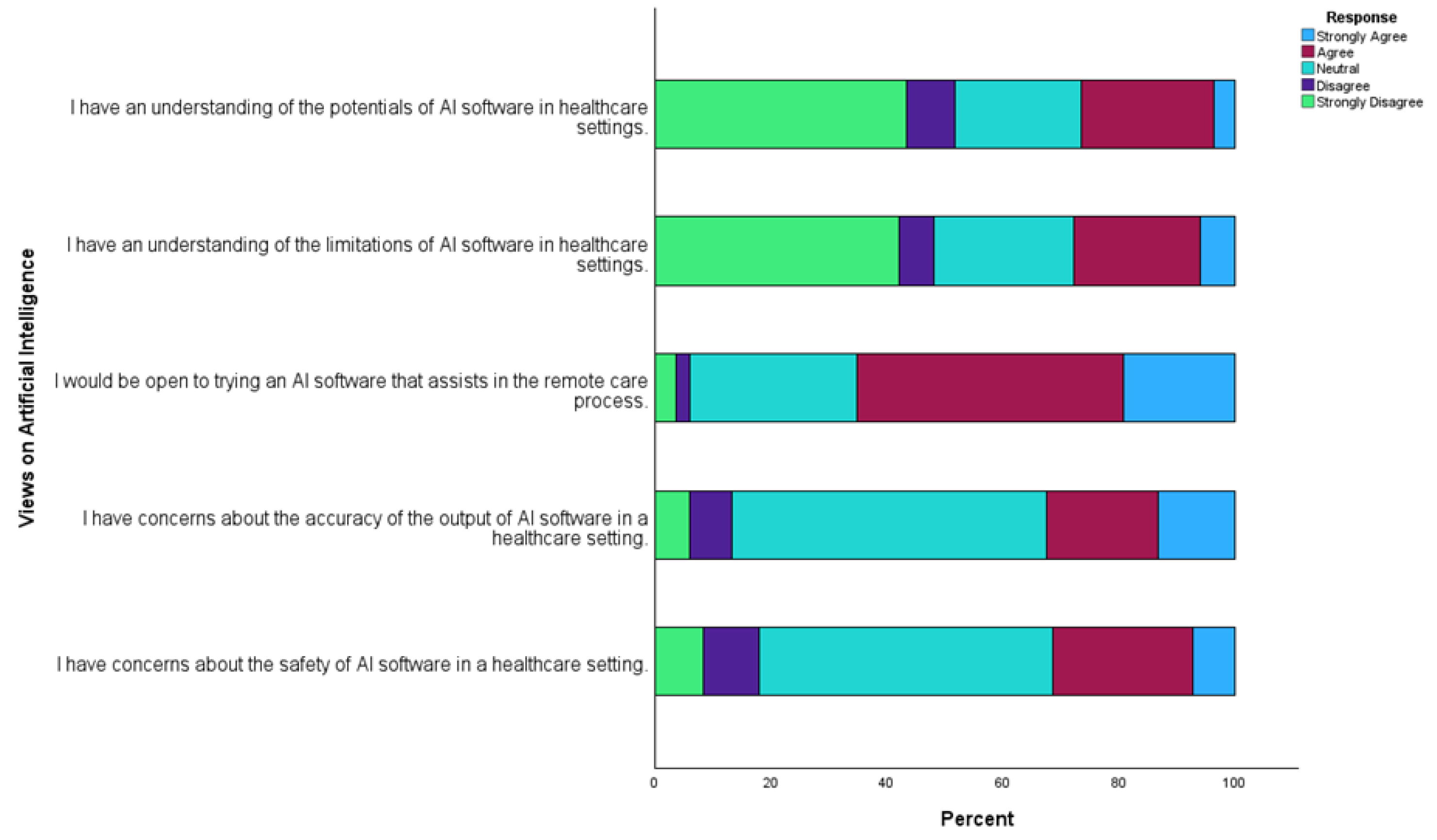

3.2.3. Views on AI assistance

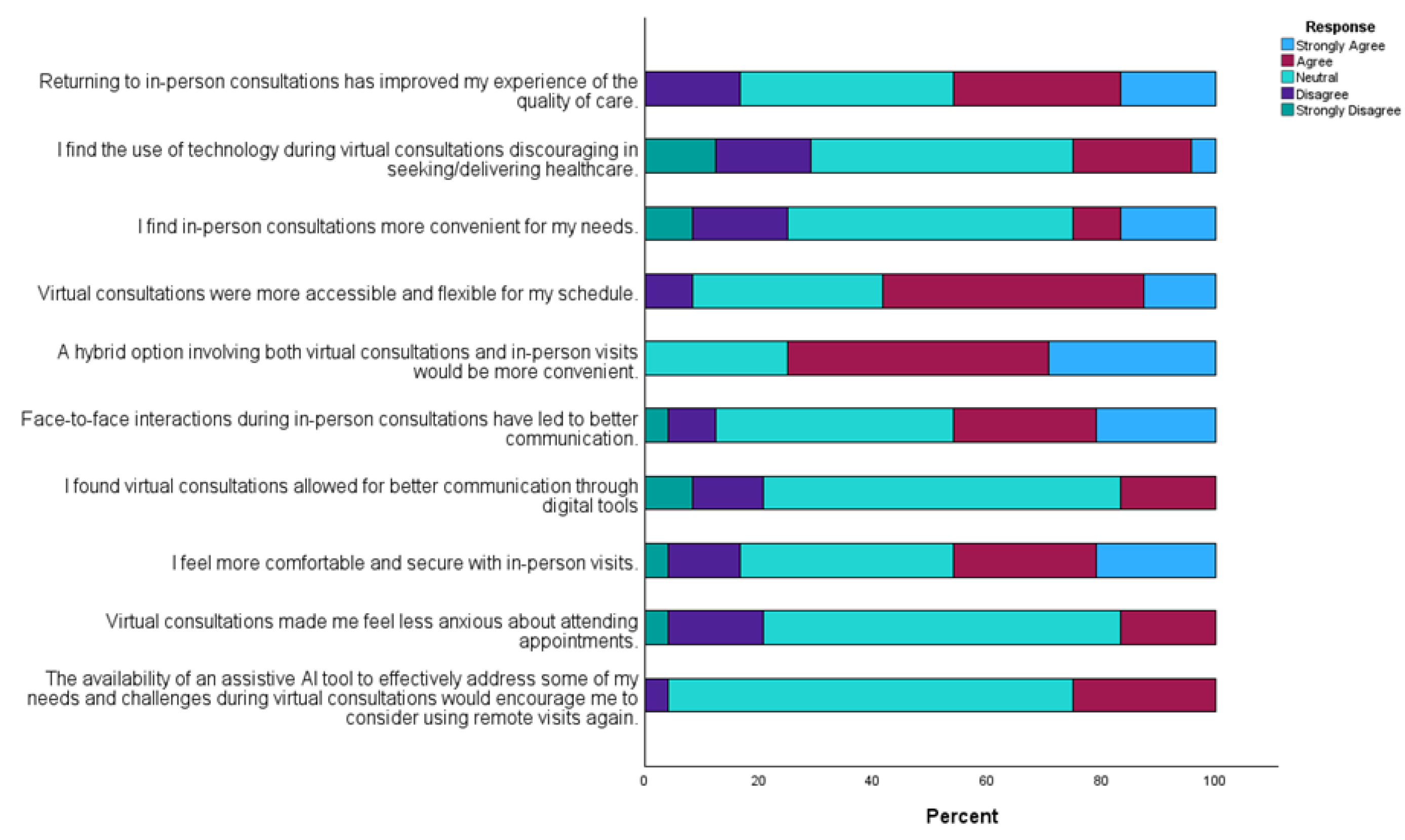

3.2.4. Perspectives of former virtual consultation users

4. Discussion

4.1. User experience of virtual consultations

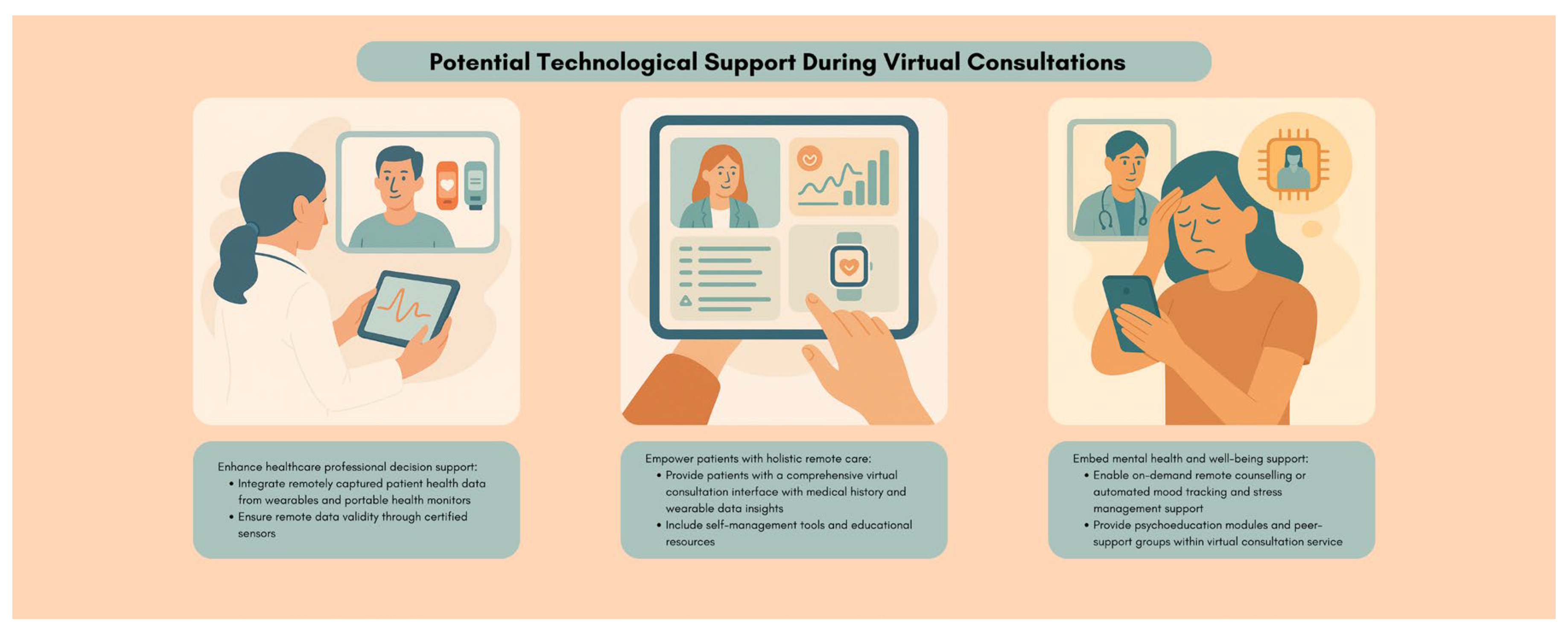

4.2. User needs and suggested improvements to enhance virtual interactions

4.3. Views on Artificial Intelligence Supplements in Virtual Consultations

4.4. Future Research and Recommendations

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| HCI | Human-computer interaction |

| HCP | Healthcare professional |

| PPI | Public and Patient Involvement |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SSI | Semi-structured interview |

| TUQ | Telehealth Usability Questionnaire |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

References

- Campbell, K.; Greenfield, G.; Li, E.; O'BRien, N.; Hayhoe, B.; Beaney, T.; Majeed, A.; Neves, A.L. The Impact of Virtual Consultations on the Quality of Primary Care: Systematic Review. J. Med Internet Res. 2023, 25, e48920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.C.; Thomas, E.; Snoswell, C.L.; Haydon, H.; Mehrotra, A.; Clemensen, J.; Caffery, L.J. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Telemed. Telecare 2020, 26, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosik, J.; Fudim, M.; Cameron, B.; Gellad, Z.F.; Cho, A.; Phinney, D.; Curtis, S.; Roman, M.; Poon, E.G.; Ferranti, J.; et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J. Am. Med. Informatics Assoc. 2020, 27, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Sanjula; Macon, Colin; Patton, Katie. Telehealth demand: An update after the COVID-19 pandemic. Trilliant Health. 09 June 2024. Available online: https://www.trillianthealth.com/market-research/studies/telehealth-demand-an-update-four-years-after-the-onset-of-the-covid-19-pandemic (Accessed: 30 December 2025).

- Armitage, Richard. “Are video/online appointments becoming more popular among patients?” BJGP Life. 26 December 2023. Available online: https://bjgplife.com/are-video-online-appointments-becoming-more-popular-among-patients/ (Accessed: 30 December 2025).

- Hvidt, E.A.; Atherton, H.; Keuper, J.; Kristiansen, E.; Lüchau, E.C.; Norberg, B.L.; Steinhäuser, J.; Heuvel, J.v.D.; van Tuyl, L. Low Adoption of Video Consultations in Post–COVID-19 General Practice in Northern Europe: Barriers to Use and Potential Action Points. J. Med Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, G.W.; Wood, J.C. Virtual health and artificial intelligence: using technology to improve healthcare delivery. In Human-Machine Shared Contexts; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kuziemsky, C.; Maeder, A.J.; John, O.; Gogia, S.B.; Basu, A.; Meher, S.; Ito, M. Role of Artificial Intelligence within the Telehealth Domain. Yearb. Med Informatics 2019, 28, 035–040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamens, S.; Dhunnoo, P.; Meskó, B. The state of artificial intelligence-based FDA-approved medical devices and algorithms: an online database. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, D.; Kakinuma, T.; Fujita, S.; Kamagata, K.; Fushimi, Y.; Ito, R.; Matsui, Y.; Nozaki, T.; Nakaura, T.; Fujima, N.; et al. Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: review and recommendations. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabitza, F.; Rasoini, R.; Gensini, G.F. Unintended Consequences of Machine Learning in Medicine. JAMA 2017, 318, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, W.N.; Cohen, I.G. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennelly, Orna. “HSE Telehealth Roadmap 2024 - 2027: Building Blocks for the Embedding & Expansion of Telehealth”. Health Service Executive. 01 December 2023. Available online: https://healthservice.hse.ie/staff/procedures-guidelines/digital-health/hse-telehealth-roadmap-2024-2027/ (Accessed: 30 December 2025).

- Kolluri, S.; Stead, T.S.; Mangal, R.K.; Coffee, R.L.; Littell, J.; Ganti, L. Telehealth in Response to the Rural Health Disparity. Heal. Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 37445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistics Office. “Census of Population 2022 Profile 1 - Population Distribution and Movements”. CSO statistical publication. 29 June 2023. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpp1/censusofpopulation2022profile1-populationdistributionandmovements/populationdistribution/ (Accessed: 30 December 2025).

- Doherty, A.; Keatings, V.; Valentelyte, G.; Murray, M.; O’toole, D. Community Virtual Ward (CVW+cRR) Proofof-Concept Examining the Feasibility and Functionality of Partnership-Based Alternate Care Pathway for COPD Patients- Empowering Patients to Become Partners in their Disease Management. Int. J. Nurs. Heal. Care Res. 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhunnoo, P.; Kemp, B.; McGuigan, K.; Meskó, B.; O’rOurke, V.; McCann, M. Evaluation of Telemedicine Consultations Using Health Outcomes and User Attitudes and Experiences: Scoping Review. J. Med Internet Res. 2024, 26, e53266–e53266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodrahalli, K.; Ko, J.; Chiou, A.S.; Novoa, R.; Abid, A.; Phung, M.; Yekrang, K.; Petrone, P.; Zou, J.; Daneshjou, R. Development and Clinical Evaluation of an Artificial Intelligence Support Tool for Improving Telemedicine Photo Quality. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Yu, X.; Shao, J.; Li, R.; Li, W. Telemedicine-Enhanced Lung Cancer Screening Using Mobile Computed Tomography Unit with Remote Artificial Intelligence Assistance in Underserved Communities: Initial Results of a Population Cohort Study in Western China. Telemed. e-Health 2024, 30, e1695–e1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Rawal, R.; Shah, D. Addressing the challenges of AI-based telemedicine: Best practices and lessons learned. J. Educ. Heal. Promot. 2023, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, M.A.P.; Arrigo, A.; Parodi, M.B.; Mengue, C.d.S. Smartphone Eye Examination: Artificial Intelligence and Telemedicine. Telemed. e-Health 2024, 30, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhunnoo, Pranavsingh, Bertalan Meskó, Vicky O’Rourke, Dr, Karen McGuigan, and Michael McCann. 2024. Protocol for a Mixed-methods Investigation of Patient and Healthcare Professional’s Perceptions of Virtual Consultations and Artificial Intelligence Assistance; OSF, 21 October 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan. Social research methods; Oxford university press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coupe, N.; Mathieson, A. Patient and public involvement in doctoral research: Impact, resources and recommendations. Heal. Expect. 2019, 23, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhunnoo, P.; Wetzlmair, L.-C.; O’carroll, V. Extended Reality Therapies for Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Sci 2024, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhunnoo, P.; Meskó, B.; O’rOurke, V.; McGuigan, K.; McCann, M. Towards Enhanced Virtual Chronic Care: Artificial Intelligence-Human Computer Interaction Integration in Synchronous Virtual Consultations. Intelligent Systems Conference, 2024; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.C.; Tong, A.; Howard, K.; Palmer, S.C. Clinicians’ experiences with remote patient monitoring in peritoneal dialysis: A semi-structured interview study. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2020, 40, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.; Leonard, C.; Muzaffar, J.; Coulson, C. Patient perceptions of a remote assessment pathway in otology: a qualitative descriptive analysis. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2022, 280, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macefield, Ritch. How to specify the participant group size for usability studies: a practitioner’s guide. Journal of usability studies 2009, 5(no. 1), 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ufholz, K.; Sheon, A.; Bhargava, D.; Rao, G. Telemedicine Preparedness Among Older Adults With Chronic Illness: Survey of Primary Care Patients. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e35028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyer, A.; Granberg, R.E.; Rising, K.L.; Binder, A.F.; Gentsch, A.T.; Handley, N.R. Medical Oncology Professionals’ Perceptions of Telehealth Video Visits. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2033967–e2033967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarzynski, T.; Miles, O.; Cowie, A.; Ridge, D. Acceptability of artificial intelligence (AI)-led chatbot services in healthcare: A mixed-methods study. Digit. Heal. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, Ph D; Patricia, I.; Ness, Lawrence R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Community Heal. 2019, 7, e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Taylor, J.; Eley, N.; McKenna, K. Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: findings from a randomized study. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3(no. 2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, Nikki Hayfield, Louise Davey, and Elizabeth Jenkinson. Doing reflexive thematic analysis. In Supporting research in counselling and psychotherapy: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 19–38.

- O’Brien, Bridget C., Ilene B. Harris, Thomas J. Beckman, Darcy A. Reed, and David A. Cook. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic medicine 2014, 89(no. 9), 1245–1251. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, United States; ISBN, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, B.L.; Getz, L.O.; Johnsen, T.M.; Austad, B.; Zanaboni, P. General Practitioners’ Experiences With Potentials and Pitfalls of Video Consultations in Norway During the COVID-19 Lockdown: Qualitative Analysis of Free-Text Survey Answers. J. Med Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuen, V.L.; Dholakia, S.; Kalra, S.; Watt, J.; Wong, C.; Ho, J.M.-W. Geriatric care physicians’ perspectives on providing virtual care: a reflexive thematic synthesis of their online survey responses from Ontario, Canada. Age and Ageing 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavngaard, M.V.; Lüchau, E.C.; Hvidt, E.A.; Grønning, A. Exploring patient participation during video consultations: A qualitative study. Digit. Heal. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.P.; Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E.; Sathian, B.; Banerjee, I. The Growing Importance of Mixed-Methods Research in Health. Nepal J. Epidemiology 2022, 12, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripepi, G.; Jager, K.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C. Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2010, 115, c94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmanto, B.; Lewis, A.N., Jr.; Graham, K.M.; Bertolet, M.H. Development of the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (TUQ). Int. J. Telerehabil. 2016, 8, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajesmaeel-Gohari, S.; Bahaadinbeigy, K. The most used questionnaires for evaluating telemedicine services. BMC Med Informatics Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, C.; Lakens, D. When power analyses based on pilot data are biased: Inaccurate effect size estimators and follow-up bias. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 74, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, H.F.; Salih, A.I.; Attash, F.M. Usability of telehealth among healthcare providers during COVID-19 pandemic in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq. Public Heal. Pr. 2023, 5, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, S.H.; Aldailami, D.A.; El Aziz, M.M.A.; Elsayed, E.A. Perceived Telehealth Usability for Personalized Healthcare Among the Adult Population in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2025, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noceda, A.V.G.; Acierto, L.M.M.; Bertiz, M.C.C.; Dionisio, D.E.H.; Laurito, C.B.L.; Sanchez, G.A.T.; Loreche, A.M. Patient satisfaction with telemedicine in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lersten, I.; Fought, A.; Yannetsos, C.; Sheeder, J.; Roeca, C. Patient perspectives of telehealth for fertility care: a national survey. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, E.; Gupta, S.; Yadav, V.; Kachnowski, S. Assessing the Usability and Effectiveness of an AI-Powered Telehealth Platform: Mixed Methods Study on the Perspectives of Patients and Providers. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e62742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, A.; Elsori, D. Navigating digital frontiers in UAE healthcare: A qualitative exploration of healthcare professionals’ and patients’ experiences with AI and telemedicine. PLOS Digit. Heal. 2025, 4, e0000586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, Louis M.; Richard, A. Parker. Designing and conducting survey research: A comprehensive guide; John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aldakhil, R.; Greenfield, G.; Lammila-Escalera, E.; Laranjo, L.; Hayhoe, B.W.J.; Majeed, A.; Neves, A.L. The Impact of Virtual Consultations on Quality of Care for Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, L.M.; Davies, M.J.; Hadjiconstantinou, M. Virtual Consultations and the Role of Technology During the COVID-19 Pandemic for People With Type 2 Diabetes: The UK Perspective. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, S.E.; Barnett, A.; Croci, I.; Hannigan, A.; Elvin-Walsh, L.; Coombes, J.S.; Campbell, K.L.; Macdonald, G.A.; Hickman, I.J. Agreement and Reliability of Clinician-in-Clinic Versus Patient-at-Home Clinical and Functional Assessments: Implications for Telehealth Services. Arch. Rehabilitation Res. Clin. Transl. 2020, 2, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, M.A.; O'LEary, S.P.; Swete-Kelly, P.; Elwell, B.; Hess, S.; Litchfield, M.-A.; McLoughlin, I.; Tweedy, R.; Raymer, M.; Hill, A.J.; et al. Agreement between telehealth and in-person assessment of patients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions presenting to an advanced-practice physiotherapy screening clinic. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pr. 2018, 38, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Moscrop, A.; Mebius, A.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lewith, G.; Bishop, F.L.; Mistiaen, P.; Roberts, N.W.; Dieninytė, E.; Hu, X.-Y.; et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 111, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, G.; Griffiths, D.; Howick, J.; Vennik, J.; Bishop, F.L.; Durieux, N.; Everitt, H.A. Empathy in patient-clinician interactions when using telecommunication: A rapid review of the evidence. PEC Innov. 2022, 1, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botrugno, C. Information technologies in healthcare: Enhancing or dehumanising doctor–patient interaction? Heal. Interdiscip. J. Soc. Study Heal. Illn. Med. 2019, 25, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, L.V.; Evans, R.; Bennett, V.; Hady, J.M.; Palaniappan, P. Therapeutic Relational Connection in Telehealth: Concept Analysis. J. Med Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, A.; Abdelaliem, S.M.F.; Zaher, A.; Sadek, B.N.; Nashwan, A.J.; Al-Jabri, M.M.A.; Ahmeda, A.; Hendy, A.; Alabdullah, A.A.S.; Sinnokrot, S.M. Telehealth satisfaction among patients with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional analysis. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruf, R.I.; Tou, S.; Izukura, R.; Sato, Y.; Nishikitani, M.; Kikuchi, K.; Yokota, F.; Ikeda, S.; Islam, R.; Ahmed, A.; et al. An evaluation of the commonly used portable medical sensors performance in comparison to clinical test results for telehealth systems. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Updat. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Loux, T.; Huang, X.; Feng, X. The relationship between chronic diseases and mental health: A cross-sectional study. Ment. Heal. Prev. 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perle, J.G.; Nierenberg, B. How Psychological Telehealth Can Alleviate Society's Mental Health Burden: A Literature Review. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2013, 31, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.I.; Madi, M.; Sopka, S.; Lenes, A.; Stange, H.; Buszello, C.-P.; Stephan, A. An integrative review on the acceptance of artificial intelligence among healthcare professionals in hospitals. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Smith, C.; Curtis, S.; Watson, S.; Zhu, X.; Barry, B.; Sharp, R.R. Patient apprehensions about the use of artificial intelligence in healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Telemedicine; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 9789264420038.

- OECD. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Telemedicine.” OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/ac8b0a27-en (Accessed 30 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, J.; Ordóñez, P.; Cao, J.; Moukheiber, M.; Moukheiber, L.; Caspi, A.; Swenor, B.K.; Naawu, D.K.N.; Mankoff, J. Telehealth and digital health innovations: A mixed landscape of access. PLOS Digit. Heal. 2023, 2, e0000401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anawati, A.; Fleming, H.; Mertz, M.; Bertrand, J.; Dumond, J.; Myles, S.; Leblanc, J.; Ross, B.; Lamoureux, D.; Patel, D.; et al. Artificial intelligence and social accountability in the Canadian health care landscape: A rapid literature review. PLOS Digit. Heal. 2024, 3, e0000597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients | Healthcare professionals |

|---|---|

| Aged 18 and above. | Qualified HCP aged 18 and above. |

| Diagnosed with at least one noncommunicable, non-malignant chronic condition. | Currently employing real-time virtual consultation (audio and/or video) for patients with communicable conditions in a secondary care setting. |

| Currently employing real-time virtual consultation (audio and/or video) for secondary care with HCPs. | Able to engage in online focus groups. |

| Not in need of urgent medical care. | Able to provide their fully informed consent. |

| Able to engage in online SSI. | |

| Able to provide their fully-informed consent. |

| TUQ measure | Currently using (n=66) | Stopped use (n=17) |

Kruskal-Wallis H (df=3) |

p-value | ε2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usefulness score (mean [standard deviation]) | 13.9 [1.9] | 13.4 [2.8] | 2.6 | 0.4 | 0.032 |

| Ease of use and Learnability score (mean [standard deviation]) | 13.2 [2.1] | 13.2 [2.1] | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.012 |

| Interface quality score (mean [standard deviation]) | 17.1 [3.3] | 17.4 [3.8] | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.013 |

| Interaction quality score (mean [standard deviation]) | 17.0 [3.1] | 17.1 [4.3] | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.022 |

| Reliability score (mean [standard deviation]) | 12.0 [3.4] | 11.8 [4.1] | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.003 |

| Satisfaction and Future Use score (mean [standard deviation]) | 17.6 [2.5] | 17.1 [4.1] | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.002 |

| Views on AI assistance measure | Currently using (n=66) | Stopped use (n=17) | Kruskal-Wallis H (df=3) | p-value | ε2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I have an understanding of the potentials of AI software in healthcare settings.” score (mean [standard deviation]) | 2.4 [1.3] | 2.0 [1.5] | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.041 |

| “I have an understanding of the limitations of AI software in healthcare settings.” score (mean [standard deviation]) | 2.5 [1.3] | 2.0 [1.5] |

5.3 | 0.1 | 0.065 |

| “I would be open to trying an AI software that assists in the remote care process.” score (mean [standard deviation]) | 3.8 [0.9] | 3.5 [1.0] | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.020 |

| “I have concerns about the accuracy of the output of AI software in a healthcare setting.” score (mean [standard deviation]) | 3.3 [1.0] | 3.3 [0.9] | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.005 |

| “I have concerns about the safety of AI software in a healthcare setting.” score (mean [standard deviation]) | 3.1 [1.0] | 3.2 [0.8] | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.012 |

| Potential AI assistance feature | Description of AI feature | Target user | Supporting theme & quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical assessment suggestions | Based on individual consultations, real-time prompts suggest assessments/queries to improve comprehensiveness of consultations. | HCPs | Quality of virtual interactions and assessments are not satisfactory. “face to face definitely gets a more accurate, from a clinical assessment, you get a better, a better picture of what’s going on.” “And I suppose the other thing with the the kind of frustrations of the virtual is when you don’t see them walking on the door, like you can tell an awful lot about a patient even watching them as they walk from the chair and to your consultation room.” |

| Conversational prompts | HCPs unfamiliar with a patient receive personalised conversational prompts based on an individual patient profile to improve virtual interaction quality and build rapport/empathy. | HCPs | Optional, hybrid models with familiar, empathetic HCPs “Uh, the ideal experience then is, uh, speaking with someone who I have met before and who I’m familiar with and who… Who I know cares about me and my care, has empathy.” “That they would show concern and that they would ask me, you know, relevant questions that will draw me out and, you know, highlight my problems and my conditions as well and what they can do to help.” “You can establish more of a relationship when you see somebody, uh, in person.” “As clinicians, we are people to, you know, person to person.” |

| Condition-specific resources and recommendations | Based on the context of a virtual consultation and individual medical history, personalised condition updates (medication/side effects, research), lifestyle advice, and educational materials are provided to patients. | Patients | Potential AI roles in virtual consultations. “I would be definitely interested in in what would be happening, uh, regarding research and medications and devices that you could wear” “sometimes when you’re put on a new drug, maybe if an AI education on that drug rather than the, you know, the doctor giving you the lowdown on it, or whatever it might be, you know, good to be able to ask questions and relate like that from, you know, just just find out the background of the drugs and the, you know, what they hope to achieve, and the side, well and the side effects too.” “Uh, I say, advice on on lifestyle, lifestyle balance and prompts for, you know, maybe, you know, exercise, go for you know and I would just say” |

| Mental wellbeing support | Mental wellbeing and emotional support and resources are shared with patients after each consultation based on individual psychological needs. | Patients | Potential AI roles in virtual consultations. “Some sort of software that if you were having a flare up in the middle of the night that would help you calm down.” “Why not, why not take part in something that’s, you know, going to give you a bit of maybe peace of mind. As for want of a better word.” |

| Additional health status insights | Analysis from wearables and past medical records can provide HCPs with more insights and patients can better understand their status for self-management. | HCPs and patients | Technological ease and optimisation for holistic virtual care “to me all them kind of gadgets, to me, should be linked to the virtual” “And maybe if you could monitor it then that that would be helpful to the person that was seeing you virtually. If you notice something yourself, you could just say say it to them maybe.” “I suppose my ideal, like if you’re doing something virtually, is that you know you have a good background. [...] So you’re not going in kind of blind.” |

| Automated consultation summaries | Based on transcripts, summaries of consultations are provided, highlighting key discussions and clarifying terms. | HCPs and patients | Potential AI roles in virtual consultations. “some sort of dictation, you know, where our consultation could be, maybe all presented back to us so that we could sign off on it.” “if they were mentioning like a condition to you that you didn’t know or haven’t heard about before, that it would be, uh, helpful that it would be able to generate information on that condition for you instantaneously, I suppose.” “sometimes there’s words used that, and sometimes if you’re having a flare up, you can’t remember half the things that’s told to you.” “And sometimes too, if you go into, see a consultant, or that you, you might come out and not remember rightly what was said. Whereas, if you had a virtual meeting, I don’t know if you could play back a virtual meeting” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.