Introduction

The global rise of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria reflects a fundamental shift in how development—corporate or urban—is financed, governed, and evaluated in the face of climate change, inequality, and technological transformation. Initially designed to assess corporate non-financial performance, ESG has expanded beyond the boardroom to influence urban development, shaping investment strategies, public policy, and regulatory regimes (Teixeira Dias et al., 2023; De Nicolò, 2020). Understanding this transition requires tracing ESG’s corporate origins and the conditions under which it evolved into a governance paradigm with spatial and urban implications.

Historically, ESG’s conceptual foundation emerged from socially responsible investment (SRI), evolving from 19th-century faith-based exclusions and late-20th-century activist campaigns to its formal naming in the 2004 UN Global Compact report Who Cares Wins (Eccles, Lee, & Stroehle, 2019). Early corporate governance concerns under modern capitalism, rooted in the CSR movements of the 1960s–1970s, emphasized transparency, ethical conduct, and environmental stewardship. These principles expanded in the late 20th and early 21st centuries in response to climate change, resource scarcity, and widening inequalities (Nascimento et al., 2024). Landmark international initiatives—including the Paris Climate Accord and the UN Sustainable Development Goals—positioned ESG as a mechanism for aligning private capital with public sustainability objectives (Wang, 2023). By the 2020s, ESG had shifted from a peripheral CSR consideration to a central component of capital allocation, driven by policy initiatives, investor activism, and market demand for long-term value creation (Ruan & Zhang, 2025).

Despite its rapid adoption, ESG remains heterogeneous in definition and practice. Divergent methodologies—shaped by the “social origins” of data providers, as illustrated by KLD Research & Analytics’ values-driven approach versus Innovest Strategic Value Advisors’ materiality-focused model—highlight its socially constructed nature (Eccles et al., 2019). In practice, ESG integration is hindered by inconsistent disclosure standards, fragmented regulations, cultural and institutional differences, and the absence of harmonized metrics (Nascimento et al., 2024; Ruan & Zhang, 2025; Wang, 2023). Translating high-level ESG policies into measurable organizational practices demands governance capacity, sector-specific adaptation, and stakeholder engagement, yet remains challenged by resource constraints and limited expertise (Diana, 2024).

In recent years, ESG principles have moved from corporate sustainability strategies into urban governance frameworks. This transition adapts corporate tools—such as performance metrics, stakeholder mapping, and risk assessment—to municipal contexts, addressing challenges including climate resilience, resource efficiency, and equitable service provision (Kapoor, Khanna, Sisodiya, & Azad, 2025). Embedding ESG indicators into city management systems enhances transparency, attracts sustainable investment, and aligns local actions with long-term climate and equity goals (Sklavos, Zournatzidou, Ragazou, Spinthiropoulos, & Sariannidis, 2025). As these frameworks gain traction, scholars are examining ESG as more than a technical or ethical benchmark: it is increasingly understood as a spatial and governance paradigm shaping the geography, politics, and equity of sustainable urbanization (Harnett, 2018; Beck, 2023).

In urban contexts, ESG is now integrated into post-pandemic regeneration (Pjeshka, 2024), real estate valuation (Newell & Marzuki, 2022), digital infrastructure (Zhai et al., 2023), and rural revitalization (Kurchenkov, Koneva, & Fetisova, 2022). Yet, its spatial implementation risks reproducing inequalities by privileging connected urban cores while marginalizing under- resourced peripheries (Gamidullaeva, 2024; Ovsiannikov, 2020). While some scholars highlight ESG’s potential for climate resilience and participatory governance (Xu & Zhao, 2024; Esmaeilpour Zanjani et al., 2021), others caution that without safeguards, it can reinforce exclusion through green gentrification, infrastructural violence, and speculative investment (Reed-Thryselius, 2023; Parish, 2023; Blok, 2020). This dual potential underscore the need to critically assess ESG’s translation from corporate origins to the spatial realities of urban planning.

Methodology

To ensure both comprehensiveness and transparency, this study relied on Lens.org as the primary database for literature retrieval. Lens integrates data from major bibliographic sources such as Crossref, PubMed, Microsoft Academic, and CORE, thereby offering a broader and more inclusive coverage than single-source databases. As Chigarev (2022) demonstrates, Lens has proven particularly effective for bibliometric and scientometric studies due to its open access model, robust API infrastructure, and capacity to generate reliable co-occurrence networks of research terms. Its multidimensional data architecture facilitates the retrieval of peer-reviewed articles across disciplines, while also mitigating access restrictions that often limit the scope of commercial databases. This makes Lens a suitable platform for conducting systematic reviews in emerging fields like ESG and urban planning, where cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary literature is essential.

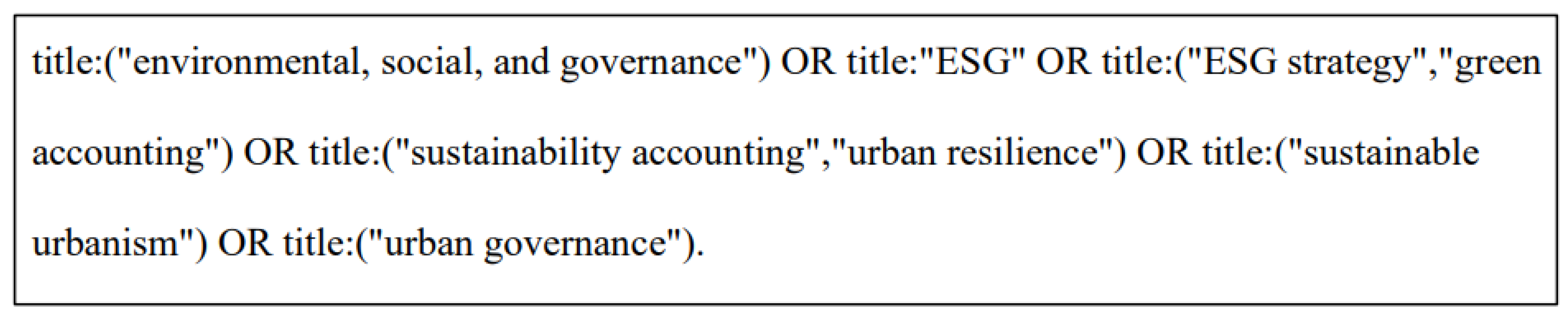

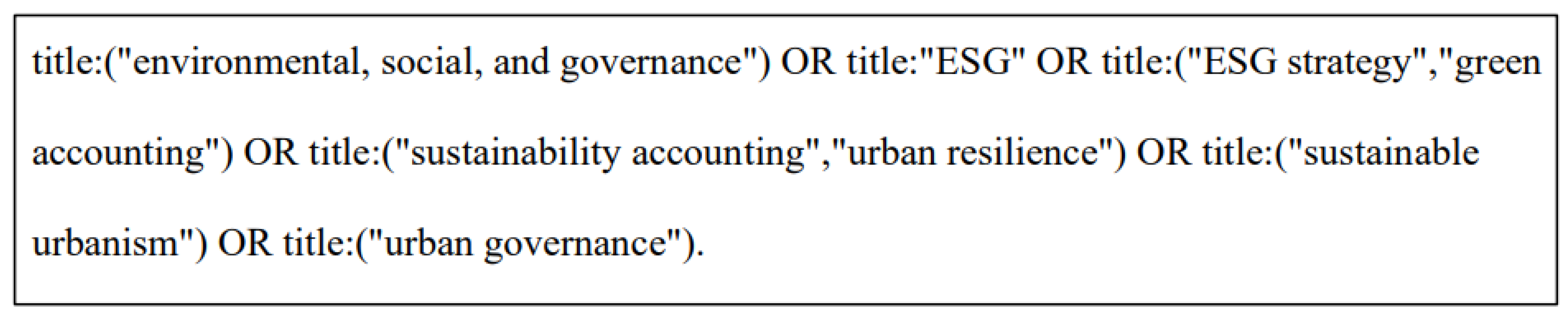

To align our query with recent ESG–urban governance scholarship and ensure replicability, we mirrored the three-block structure used by Sklavos et al. (2025)— (1) the ESG construct, (2) accounting sub-domains, and (3) urban governance/resilience—adapting it to Lens.org’s title field for higher conceptual precision. The exact string was:

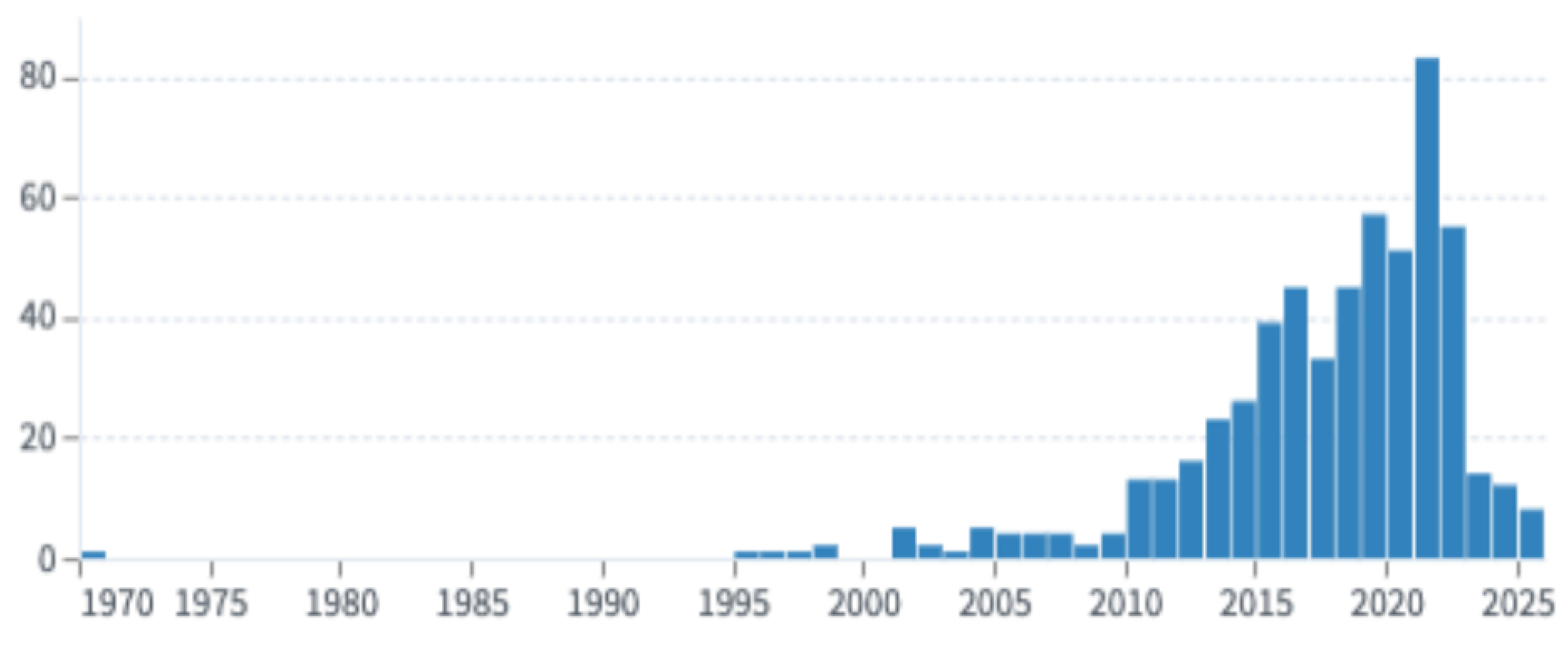

This design captures the corporate roots of ESG (ESG/ESG strategy), the accounting bridge that operationalizes disclosure (green/sustainability accounting), and the municipal application space (urban resilience, sustainable urbanism, urban governance). Using this string with filters Publication Type = journal article, Field of Study = Urban planning, and Has Full Text retrieved 574 records. As shown in

Figure 1, the annual distribution indicates a sharp increase after 2015, with a peak in 2021 of more than 80 publications, reflecting a consolidation of ESG discourse in urban planning. To capture this momentum and align with the most recent urban ESG debates, we restricted the dataset to Published Date = 2020-01-01–2025-08-18, which yielded 197 records for screening.

The figure illustrates the temporal evolution of publications, with a sharp increase after 2015 and a peak in 2021, reflecting the consolidation of ESG discourse in urban planning.

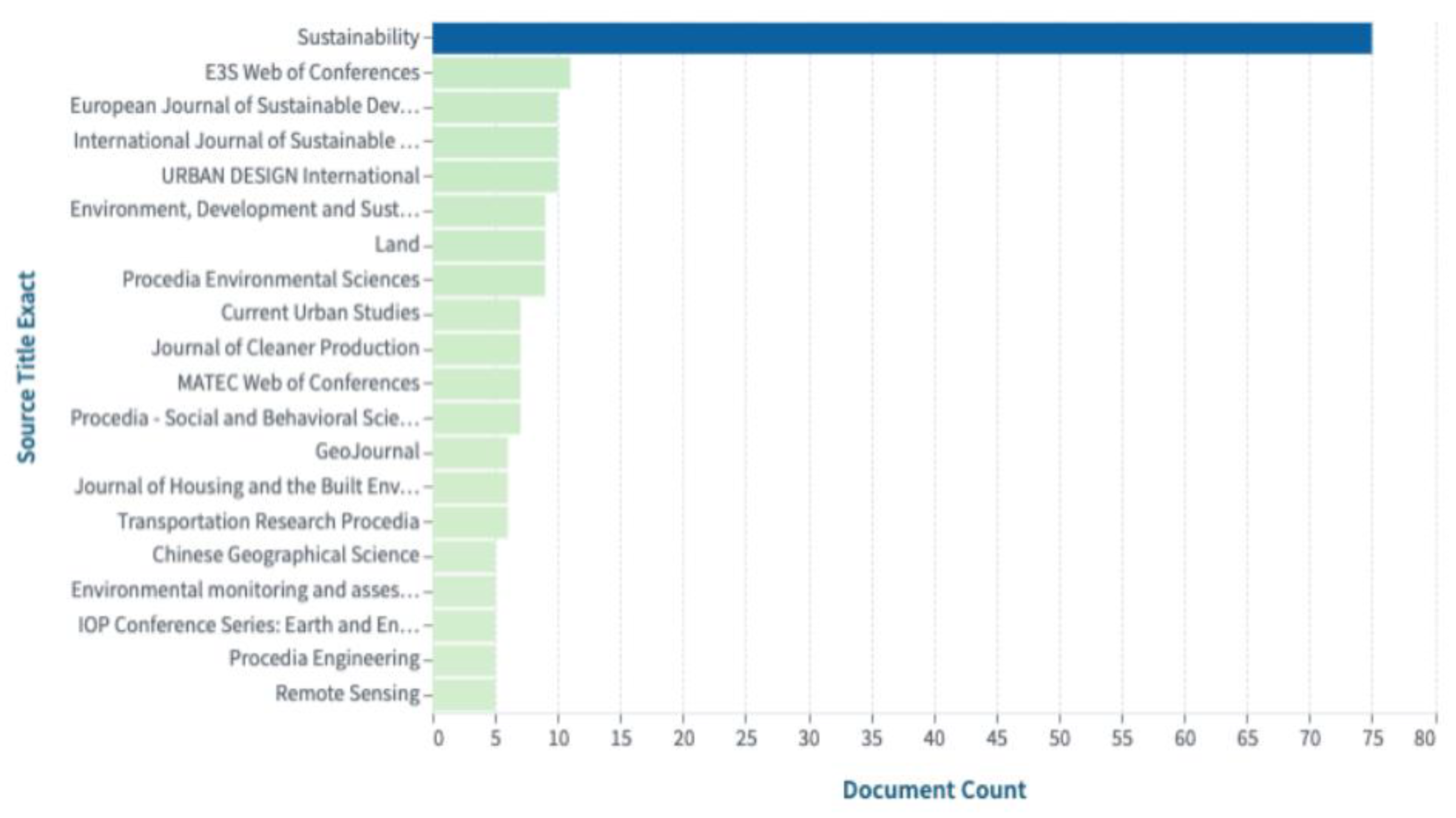

Figure 2 displays the journal distribution of this refined corpus. The journal Sustainability dominates with nearly 80 articles, followed by ESG Web of Conferences, European Journal of Sustainable Development, and Environment, Development and Sustainability. This concentration illustrates both the interdisciplinary breadth of the field and its reliance on open-access platforms for rapid dissemination.

The distribution shows that Sustainability dominates with nearly 80 articles, followed by ESG Web of Conferences, European Journal of Sustainable Development, and Environment, Development and Sustainability, highlighting the prominence of open-access outlets.

Similarly,

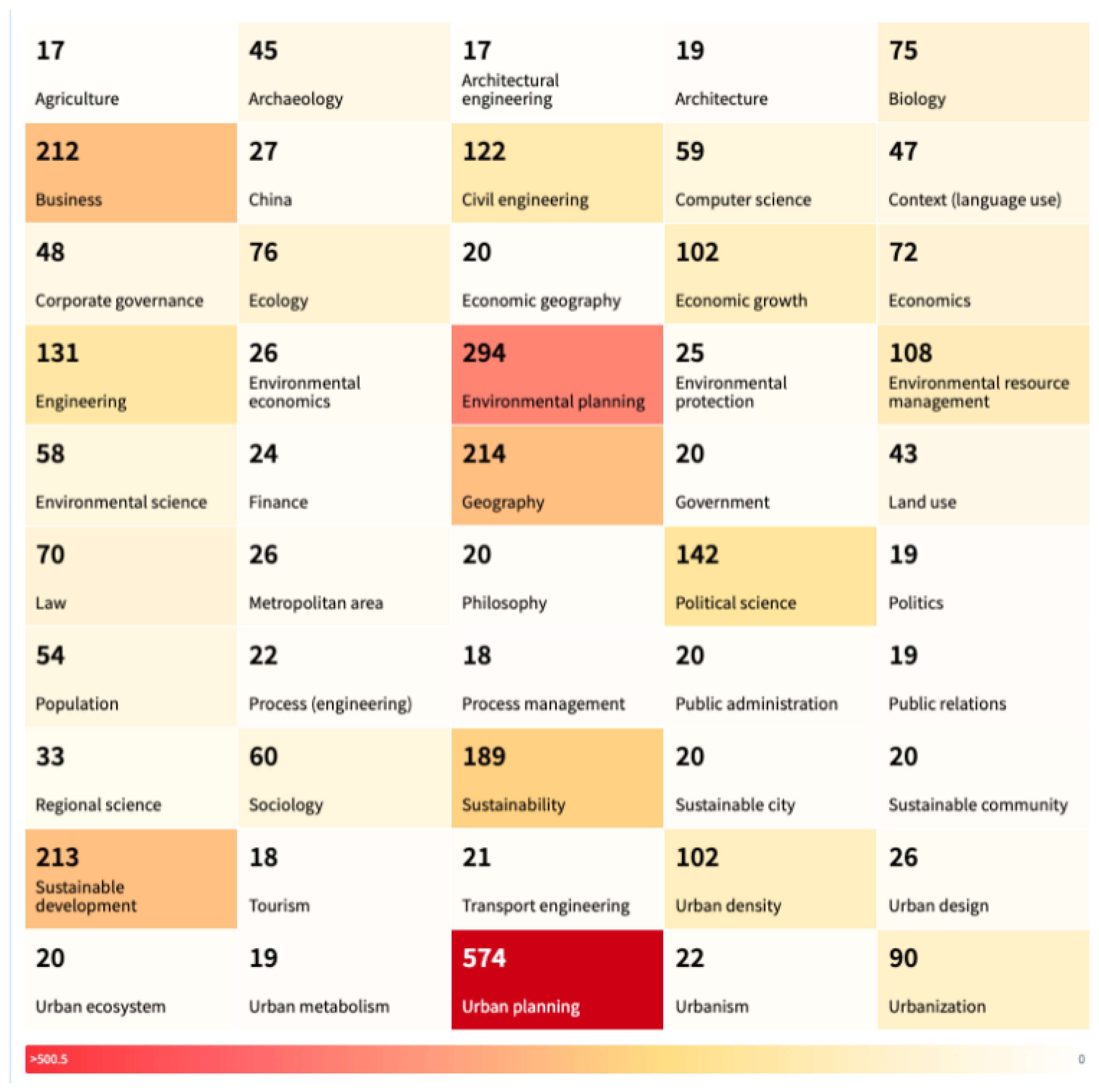

Figure 3 shows the disciplinary allocation of the retrieved works, with Urban Planning (574), Environmental Planning (294), and Sustainability (189) as the largest fields of study, demonstrating that ESG has become deeply anchored in spatial disciplines rather than confined to corporate governance alone. Together, these descriptive statistics provide a quantitative backbone to our review and directly respond to the need for a clearer illustration of major research directions.

Urban Planning, Environmental Planning, and Sustainability emerge as the largest disciplinary clusters, showing how ESG scholarship has moved beyond corporate governance to become deeply anchored in spatial disciplines.

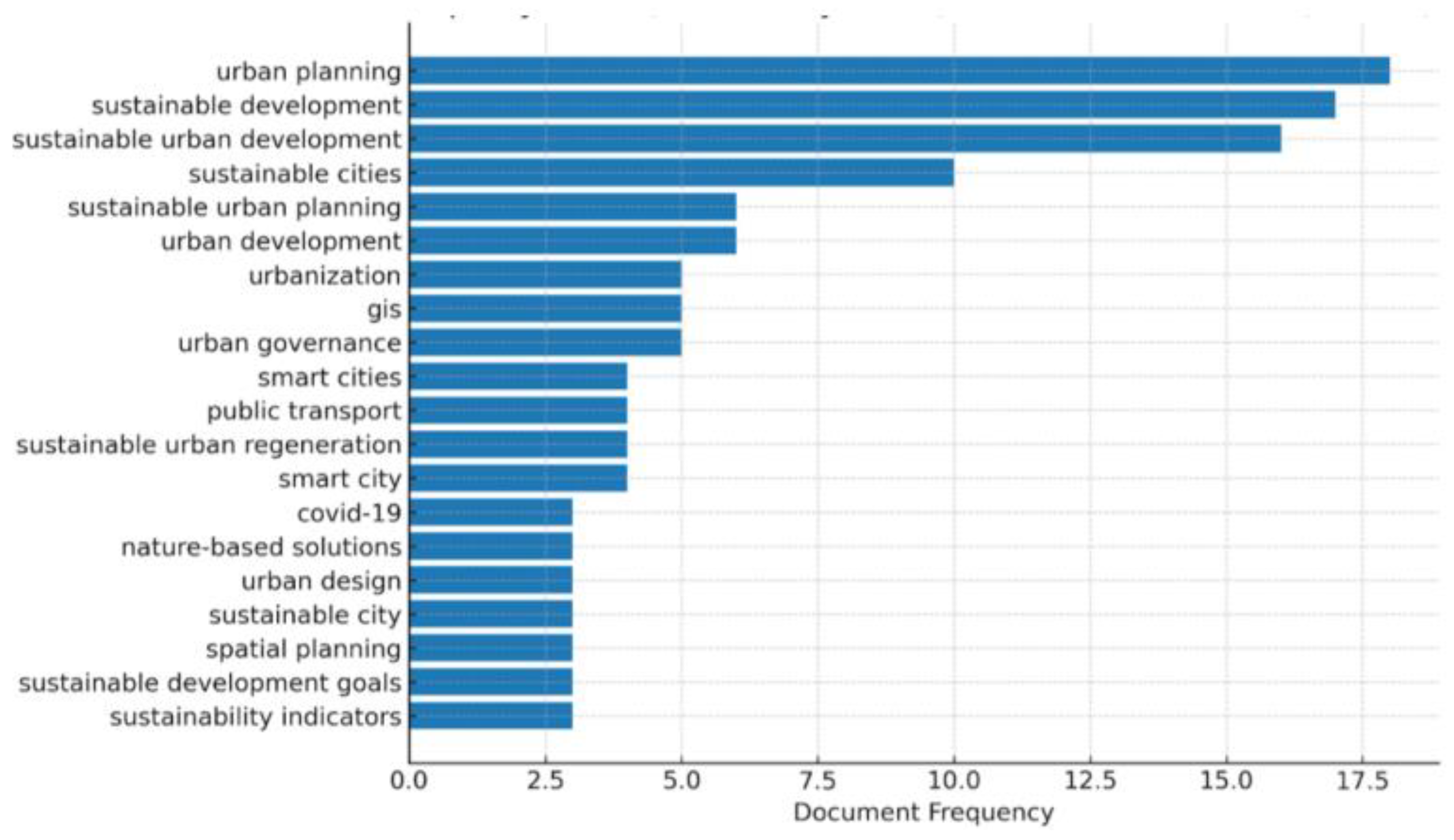

To further illustrate research directions, we conducted a descriptive keyword frequency analysis.

Figure 4 highlights the most frequent author keywords in the dataset, with urban planning, sustainable development, sustainable urban development, and sustainable cities emerging as dominant clusters. These patterns corroborate our thematic synthesis by showing how ESG scholarship is increasingly structured around urban sustainability concepts.

Keywords such as “urban planning,” “sustainable development,” and “sustainable cities” dominate, confirming the strong alignment of ESG research with urban sustainability debates.

Finally,

Figure 5 shows the global geography of ESG–urban planning publications. The United Kingdom and China lead (40 publications each), followed by Australia (23), Germany and the United States (22 each), and the Netherlands (20). This distribution demonstrates that ESG–urban planning debates are not solely European but are globally diffused, with significant clusters in Asia-Pacific, North America, and the Middle East. This global distribution strengthens the generalizability of our findings while also allowing us to highlight European contributions in comparative perspective.

The United Kingdom and China lead with 40 publications each, followed by Australia, Germany, the United States, and the Netherlands, demonstrating a geographically diverse but globally uneven landscape.

Following screening, we used an inductive, integrative synthesis to code titles, abstracts, and full texts, grouping concepts iteratively until stable categories emerged—an approach consistent with integrative procedures that link urban policy/governance constructs with ESG to structure thematic evidence (e.g., problem framing → keyword filters → synthesis map) in prior urban-sustainability reviews (Teixeira Dias et al., 2023). This yielded five dominant, non-overlapping themes that jointly span the corporate-to-urban translation and its spatial consequences:

(i) ESG as a Spatial Planning Framework;

(ii) ESG Integration in Real Estate and Infrastructure;

(iii) Spatial Inequality and Green Gentrification;

(iv) Urban Form, Clustering, and Regional Disparities;

(v) Institutional and Governance Innovations; and

We retained this taxonomy because it maximizes conceptual coverage while minimizing redundancy, and it mirrors how recent urban ESG mappings organize evidence across governance tools, investment channels, distributional outcomes, morphology, and measurement challenges.

Despite its systematic design, this methodology has several limitations. First, reliance on Lens.org, while advantageous for its multidimensional coverage, may still omit region-specific or non-indexed journals, particularly non-English outlets. Second, by restricting the query to the title field, relevant studies where ESG appears only in abstracts or keywords may have been excluded. Third, the field-of-study filter for Urban Planning depends on Lens’ automated classifications, which can misclassify or omit interdisciplinary work situated in law, economics, or environmental management. Fourth, limiting the dataset to records with full-text availability biases the sample toward open-access outlets (e.g., Sustainability), potentially underrepresenting proprietary or paywalled sources. Fifth, the temporal window of 2020–2025, although justified by the post-2020 surge in ESG debates, excludes formative studies from the late 2010s. Sixth, the search terms, while conceptually precise, may not capture adjacent literatures (e.g., smart cities, digital governance, climate adaptation) where ESG is implicit. Finally, the quantitative analysis is restricted to descriptive statistics (publication counts, journal outlets, keyword frequencies, and regional distributions) rather than advanced network analyses, limiting the mapping of deeper intellectual linkages. These limitations were partially mitigated through backward citation chaining, yet they remain important to acknowledge when interpreting the results.

ESG as a Spatial Planning Framework

Recent scholarship highlights how environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles, once confined to corporate governance, are increasingly mobilized as frameworks that directly shape urban form and governance structures. Teixeira Dias et al. (2023) show that ESG becomes spatially meaningful when embedded into urban policy targets, multi-level governance, and participatory mechanisms, enabling ecological balance and socio-spatial equity within the remit of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11. Their framework emphasizes the integration of environmental management, social inclusion, and governance accountability into municipal policy cycles, positioning ESG as a driver of both resilient infrastructure planning and inclusive city-making.

One mechanism through which ESG exerts influence is the allocation of investment capital and the discursive construction of “investment-worthy geographies.” Harnett (2018) demonstrates that ESG is not a neutral evaluative tool but a socio-spatial practice that privileges certain urban contexts while marginalizing others. By inscribing financial logics into planning decisions, ESG can reinforce existing hierarchies unless intentionally re-politicized through redistributive governance. Thus, ESG functions simultaneously as a governance technology and as a contested field of socio-spatial negotiation.

Applications in urban regeneration projects further demonstrate ESG’s transformative role. Pjeshka (2024) illustrates how ESG criteria have been integrated into post-pandemic redevelopment of carbon-intensive urban zones, aligning local plans with global sustainability imperatives. ESG serves here as an evaluative mechanism, linking financial viability with long-term socio-environmental responsibility under Agenda 2030. This operationalization shows that urban renewal guided by ESG not only secures investment but also embeds resilience and decarbonization into redevelopment trajectories.

Digitalization provides another key mechanism for embedding ESG in urban governance. Zhai et al. (2023), drawing on a quasi-natural experiment of the Broadband China Policy, find that expanded broadband access enhances corporate ESG performance by increasing transparency, reducing agency problems, and strengthening accountability. Kuznetsov et al. (2023) extend this to an explicitly urban scale, proposing a data-driven urban management model for Russia’s largest cities in which ESG indicators are linked to smart city strategies, including electric mobility and clean clusters. These examples demonstrate how digital infrastructures create governance feedback loops that bind ESG compliance to urban service delivery and planning systems.

Yet the benefits of ESG are unevenly distributed. Gamidullaeva (2024) warns that over-concentration of urban growth—if guided by ESG only at the metropolitan scale—risks deepening rural exclusion and ecological vulnerability. Similarly, Grishina, Amelicheva, and Tikhanov (2021) stress the importance of distinguishing between corporate social responsibility (CSR), which is firm-centric, and social investment, which entails multi-actor collaboration, in order to achieve inclusive ESG-aligned urban change. Their analysis of Russian cities shows that participatory social investment—recreational and creative infrastructure, community engagement, intergenerational shifts in consumer values—offers stronger pathways to socially cohesive and resilient urban spaces.

Case study evidence reinforces these mechanisms. Yu, Ma, Cheng, and Kyriakopoulos (2020) develop an evaluation system for sustainable urban spatial development in China’s Qin-Ba mountain area, showing that indicators such as industrial land use, per-capita green land, and forest area significantly shape ESG-compatible urban development trajectories. The framework of “green coordination, green development, and green sustainability” operationalizes ESG at the interface of ecological capital and spatial planning, providing a replicable model for underdeveloped but resource-rich regions. Complementing this, Kudryavtseva, Malikova, and Egorov (2021) examine Russian urban regions and highlight how ecological externalities (air quality, industrial emissions, green coverage ratios) can be systematically incorporated into ESG-oriented planning to mitigate negative spatial spillovers and advance regional sustainability. These cases illustrate how ESG is not only a governance discourse but also a set of measurable, spatialized criteria guiding urban land-use allocation and ecological performance.

Finally, new theoretical contributions are refining ESG’s scope. Beck (2023) proposes the EESSGG framework, which explicitly incorporates stakeholder engagement and goal alignment as missing dimensions of urban ESG models. By embedding pluralistic participation and shared accountability, this approach moves ESG from a technocratic checklist toward a relational governance model, one better suited to the multi-scalar complexities of contemporary urban challenges.

Taken together, these studies suggest that ESG as a spatial planning framework operates through three interrelated mechanisms: (i) capital allocation and discursive valuation of urban spaces, (ii) policy integration and technological infrastructures that embed ESG into planning systems, and (iii) multi-actor collaboration that redefines governance accountability. Case studies from China and Russia demonstrate how these mechanisms play out in practice, highlighting both the potential and the unevenness of ESG-driven urban transformations.

ESG Integration in Real Estate and Infrastructure

The spatial and sectoral implications of ESG integration in real estate are increasingly shaping investment strategies, governance models, and sustainability benchmarks across global markets. Newell and Marzuki (2022) highlight the uneven adoption of sustainability practices within global real estate, identifying a persistent transparency gap across 99 countries. Their analysis of the JLL Global Real Estate Transparency Index (GRETI) between 2016 and 2020 reveals that while overall transparency has improved, only 1% of markets qualify as “highly transparent” in the sustainability dimension. The study underscores structural limitations—particularly in emerging markets—hindering consistent environmental reporting, resilience benchmarking, and carbon neutrality adoption. The authors advocate for context-sensitive strategies, including incentives and capacity building, to accelerate ESG implementation in rapidly urbanizing regions.

Building on this, Nanda (2023) stresses that the real estate sector’s considerable carbon footprint necessitates a holistic ESG framework that addresses social equity and governance alongside environmental concerns. He argues that ESG should transcend compliance to become a foundational principle for long-term value creation, redefining asset performance in terms of resilience, impact, and accountability. Yet, significant challenges persist. Scholars identify three recurring barriers: (1) the absence of standardized ESG metrics, which limits comparability across regions and asset classes (Newell, Nanda, & Moss, 2023); (2) the difficulty of capturing long-term, systemic impacts such as climate resilience or social inclusion in investment evaluations (Rossi, Byrne, & Christiaen, 2024); and (3) the potential for “greenwashing,” where superficial sustainability claims mask limited operational or governance transformation (McCabe, 2023). These limitations suggest that ESG frameworks must move beyond disclosure checklists to become embedded in the strategic, operational, and financial core of real estate assets.

Opportunities for more effective ESG adoption are emerging through both methodological innovations and successful project-level practices. Rossi et al. (2024) propose an open geospatial scoring framework that leverages remote sensing to disaggregate environmental performance into biodiversity, hydrology, soil, and air quality sub-indices, enhancing comparability and asset-level accountability. Liao and Zheng (2024), through the MIT Asia Real Estate Initiative, emphasize that Asian urban contexts—particularly China and India—require cross-border collaboration and policy innovation to address rapid urbanization, air pollution, and governance gaps. In retail real estate, Penati (2022) demonstrates how ESG compliance not only reduces operating costs but also enhances investor attractiveness and consumer loyalty. His analysis of case studies such as Lidl and Prada illustrates how environmental efficiency and ethical governance directly translate into improved footfall, occupancy, and brand resilience. Likewise, the Eurocommercial and Klépierre funds showcase how ESG strategies in shopping centers can integrate certification schemes (BREEAM, LEED, GRESB) to align financial sustainability with social and environmental outcomes.

Recent doctoral work further reinforces this trajectory. McCabe (2023), in a comprehensive review of ESG and real estate, identifies exemplar projects such as certified net-zero office complexes and community-centered mixed-use developments as evidence that ESG integration can generate both financial and societal value. These projects illustrate that, when pursued authentically, ESG can enhance resilience, tenant satisfaction, and long-term valuation.

Similarly, Almusaed, Almssad, and Yitmen (2024) argue that integrating sustainable architectural design with ecological and financial considerations yields operational cost savings and increased property values. Technological innovations, particularly under the Industry 5.0 paradigm, also enable circular economy practices and participatory governance through IoT, AI, and smart land management systems (Bhattacharya & Sachdev, 2024).

Despite these advances, implementation gaps remain significant. Noh and Kim (2023), surveying 286 asset managers in Korea, reveal a persistent misalignment between ESG’s perceived importance and its execution, particularly in the environmental dimension. Likewise, Simons et al. (2023), analyzing over 265 articles, show that scholarship disproportionately emphasizes North American residential contexts, quantitative regression models, and green certifications, while Asian markets, case studies, and social dimensions remain underexplored.

These biases highlight the need for methodological diversification and geographic balance in future ESG research. Taken together, the evidence suggests that while ESG integration in real estate and infrastructure is progressing, its transformative potential depends on overcoming measurement and credibility challenges, scaling successful exemplars, and embedding ESG as a structural driver of resilience and equity in the built environment.

Spatial Inequality and Green Gentrification

The integration of ESG principles into urban development has revealed a growing tension between environmental ambitions and socio-spatial equity. While Yang and Hei (2024) and Wang, Li, and He (2024) demonstrate that ESG investments generate measurable environmental benefits with positive spillovers across regions, these gains are often unevenly distributed. In practice, ESG-aligned urban regeneration frequently concentrates in affluent districts with robust governance and financial infrastructure, leaving disadvantaged neighborhoods under-served.

This uneven geography illustrates a key mechanism of socio-spatial inequality: the clustering of green amenities in wealthier areas while low-income residents face exclusion from environmental gains.

Several mechanisms underpin this inequitable distribution. First, displacement pressures emerge when ESG-driven projects raise property values and rents, pushing out low-income residents. Bressane et al. (2024) show how large-scale, top-down Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) risk triggering precisely such dynamics when not coupled with redistributive safeguards. Second, selective concentration of green infrastructure can amplify inequalities: affluent districts often receive high-quality parks, transit upgrades, and energy-efficient housing, while marginalized neighborhoods remain underserved. Jelks et al. (2021) highlight how greening can paradoxically reduce park usage and belonging among minority groups if new amenities are not culturally or economically accessible. Third, financialization mechanisms—such as the channeling of ESG capital through public pension funds—can translate environmental goals into speculative redevelopment, a process Parish (2023) critiques as “infrastructural violence.” Finally, symbolic greenwashing compounds these effects, as McCabe (2023) warns: sustainability branding may legitimize exclusionary redevelopment without delivering substantive social benefit.

Empirical examples reinforce these dynamics. The New York High Line has become a paradigmatic case of green gentrification, where a celebrated urban park catalyzed luxury real estate investment and displacement of long-standing communities (Quinton, Nesbitt, & Sax, 2022). In London, Docklands regeneration illustrates how climate-resilient waterfront development privileged global capital flows over local affordability, deepening socio-economic divides. Similarly, Blok’s (2020) comparative study of Copenhagen and Surat shows how “low- carbon gentrification” operates across scales, where climate adaptation in the Global North can reproduce injustices in the Global South through uneven risk outsourcing. These examples demonstrate that ESG-aligned interventions, if left to market logics, often reproduce rather than resolve urban inequalities. Scholars propose several strategies to mitigate these risks. Reed-Thryselius’s (2023) “just green enough” approach emphasizes small-scale, culturally sensitive greening that avoids speculative value capture. Oscilowicz et al. (2025) highlight grassroots mechanisms such as land trusts and cooperative housing, which can buffer against displacement while embedding ESG goals in community control. Cucca, Friesenecker, and Thaler (2023) call for redistributive justice frameworks that integrate housing affordability, accessibility, and tenure security into climate-oriented interventions. Xu and Zhao (2024) similarly argue for crisis-responsive planning models that balance environmental resilience with digital governance and social equity. Taken together, these approaches stress that participatory governance is not a procedural add-on but a structural necessity for ensuring ESG-driven urbanism advances socio-spatial justice.

Urban Form, Clustering, and Regional Disparities

Urban form is increasingly recognized not only as an outcome of socio-economic dynamics but also as a structuring force in shaping ESG-aligned real estate strategies. Mueller and Sanderford (2020) argue that contemporary analyses—leveraging high-resolution spatial and microeconomic data—have repositioned urban morphology as both reflective of and instrumental to public policy and economic structures. This dual role becomes particularly salient where land-use monopolies and zoning regulations determine density, land values, and access to infrastructure. For ESG-conscious investors, this reconceptualization elevates urban form from a design variable to a governance and economic factor, guiding decisions on resilience and risk exposure in compact, mixed-use, and transit-oriented developments.

Transportation infrastructure is one of the most decisive factors linking ESG integration to spatial form. Fu, Luo, and Yan (2023) show how high-speed rail connectivity produces spillover effects that extend growth beyond metropolitan cores, redistributing economic opportunities to smaller cities. Similarly, Bertholdo and de Castro Marins (2024) find that proximity to metro lines and innovation hubs drives clustering in São Paulo’s startup ecosystems, underscoring the importance of transport networks in sustainable urban agglomeration. These examples illustrate how transport policy not only reduces carbon dependency but also reconfigures the geography of ESG-compliant growth.

Zoning and land-use regulation constitute another critical mechanism. Policies that incentivize mixed-use density, adaptive reuse, or inclusionary housing can channel ESG capital into equitable regeneration, while exclusionary zoning entrenches socio-spatial divides. Ovsiannikov’s (2020) critique of Sweden’s center–periphery dynamics highlights how restrictive planning regimes and labor market incentives concentrate talent and investment in Stockholm at the expense of peripheral regions. In contrast, Ye and Jia’s (2024) polycentric radiation-association framework provides a spatial alternative: by embedding sub-centers into metropolitan fabrics, zoning can be mobilized as a lever for economic diffusion, ecological cohesion, and social equity.

Economic and fiscal policies further mediate ESG-aligned urban form. Lucas (2022) illustrates how state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and smart city programs embed ESG standards in digital infrastructure, innovation zones, and municipal services. Tax incentives, green finance instruments, and subsidies for energy-efficient housing similarly shape clustering by lowering barriers to sustainable investment. Case studies such as Portland’s transit-oriented development, Hong Kong’s rail-plus-property model, and China’s Pearl River Delta polycentric planning demonstrate how fiscal and governance frameworks interact with transport and zoning policies to produce durable ESG outcomes.

Yet the distributional effects of clustering remain uneven. While infrastructural integration and polycentricity can diffuse growth, unchecked centralization amplifies disparities, privileging well-connected cores and marginalizing peripheral areas. Addressing these imbalances requires an integrated governance approach: aligning transport investment, zoning reform, and fiscal incentives with redistributive strategies that ensure ESG-driven urban form delivers not only environmental benefits but also socio-spatial justice

Institutional and Governance Innovations

As ESG frameworks gain traction in urban sustainability discourse, scholars and practitioners increasingly emphasize the governance mechanisms through which principles of accountability, equity, and resilience can be institutionalized. De Nicolò (2020) proposes a comprehensive framework for embedding ESG criteria into public administration systems, bridging the divide between institutional investment logics and local planning needs. By linking public procurement with tools such as LEED for Cities, BREEAM Communities, and GRESB, governments can standardize project evaluation, while green and social bonds—underpinned by EU initiatives such as InvestEU—expand fiscal space for regeneration. These regulatory and financial innovations highlight ESG’s potential to move beyond compliance and function as a policy mechanism for climate neutrality, resource efficiency, and inclusive governance at the municipal scale.

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are increasingly central to this transformation. Alatagi’s (2021) framework for Urban Local Bodies in India introduces an ESG Assessment Framework and Investment-Ready Index that enable cities like Ahmedabad and Indore to leverage private and multilateral capital. PPPs structured around such indices create credibility for investors while incentivizing municipal integrity and performance. Comparable models, such as Hong Kong’s rail-plus-property transit-oriented development or Portland’s public sustainability charters, illustrate how PPPs can embed ESG standards into infrastructure delivery and land-use planning, aligning private investment returns with public equity and environmental goals.

Normative governance reforms also depend on stakeholder engagement. Esmaeilpour Zanjani et al. (2021) conceptualize “good sustainable urban governance” through nine ESG- linked dimensions—accountability, transparency, legitimacy, and civic participation among them—that redefine the relational contract between governments and citizens. Mechanisms such as participatory budgeting, community land trusts, and neighborhood-level climate assemblies illustrate how ESG frameworks can institutionalize democratic co-production, counteracting top-down planning biases.

Finally, regulatory frameworks increasingly anchor resilience governance. Xu and Zhao’s (2024) seven-factor ESG-based model for China’s Greater Bay Area exemplifies how multi-scalar coordination can integrate environmental (low-carbon transitions, ecological restoration), social (education reform, digital equity, health), and governance (fintech regulation, stakeholder coordination) imperatives. This systemic approach reveals that ESG’s value lies not only in measurement but also in operationalizing adaptive governance across crises. Case evidence from European green finance regimes and Asian innovation zones suggests that institutionalizing ESG through regulation, PPPs, and participatory engagement produces durable governance innovations that embed sustainability into the DNA of urban systems.

Gaps, Innovations, and Spatial Limitations in ESG Assessment

Despite the increasing institutionalization of ESG frameworks in urban development, several conceptual, methodological, and geographic gaps remain, particularly in the European context. Battisti (2023), for example, bridges ESG and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through a localized evaluation model for housing regeneration in Florence. By aligning ESG pillars with SDG indicators, his multidimensional methodology enables project-level assessment of environmental impacts, social equity, and governance effectiveness. This place-sensitive approach underscores the need for metrics that translate global frameworks into actionable urban planning tools. Complementing this urban focus, Kurchenkov, Koneva, and Fetisova (2022) extend ESG into rural development through the ESGEH framework, which adds “Economy” and “Heritage” dimensions. Their model highlights how demographic decline, cultural preservation, and peripheral governance demand broader territorial ESG adaptations beyond corporate-centered models.

Digital transformation also emerges as a critical enabler of ESG adoption. Obushnyi and Novikov (2024) demonstrate how digital platforms, smart monitoring, and data analytics enhance environmental transparency while improving investment appeal for regeneration projects. Similarly, Bocca and Massimiano (2024) propose a multi-actor ESG framework that integrates land-use planning with the Paris Agreement and SDGs. Their model emphasizes ecological transition, social inclusion, and transparent governance, while calling for performance tools such as LEED and Walk-Score to evaluate ESG projects. Yet Peeters (2024) critiques the EU Taxonomy for its narrow focus on individual buildings, advocating instead for models that incorporate ecological connectivity, GIS data, and spatial justice principles. Together, these studies reveal that digital infrastructures and performance tools can strengthen ESG governance, but fragmented applications and regulatory blind spots remain.

At the methodological level, innovations are reshaping ESG assessment. Morelli et al. (2025) develop a spatiotemporal clustering model that tracks corporate sustainability in Western Europe using MSCI ESG data and geodetic metrics. Their findings highlight a persistent divergence between environmental scores and composite ESG ratings, raising concerns over indicator reliability. Likewise, Vardopoulos et al. (2023) use GIS-based photointerpretation to examine urban expansion in Pafos, Cyprus, showing how compact city principles can reinforce environmentally conscious development. From a macro perspective, David, Wang, and David Jr. (2024) analyze six decades of ESG evolution, revealing how higher GDP levels correlate with advanced ESG practices across European economies. Their work stresses the importance of culturally adaptive and context-specific ESG frameworks, especially in developing regions where corporate ESG models may misalign with local socio-economic realities.

Finally, Wan et al. (2023) provide a bibliometric analysis of 755 ESG publications from 2004–2021, identifying five thematic clusters—ESG philosophy, influencing factors, financial outcomes, CSR linkages, and ESG investing. They also highlight three emerging trends—ESG in emerging markets, ESG-capital market linkages, and disclosure complexities—while drawing attention to persistent challenges such as score divergence and greenwashing. While Wan’s meta-analysis illustrates the breadth and acceleration of ESG scholarship globally, our dataset—restricted to urban planning and governance—shows that research remains concentrated around sustainability-oriented concepts, with more limited engagement in governance, regeneration, and digital tools (

Table 1). This contrast underscores a persistent spatial gap: ESG discourse is expanding rapidly, but its urban and territorial dimensions are only beginning to be systematically explored.

Core research cluster anchoring ESG within urban sustainability.

Emphasis on capacity-building and governance integration.

Conceptual focus on urban sustainability pathways.

Broad discourse on development trajectories, less specific.

Growing role of spatial methodologies in ESG evaluation.

Institutional/governance innovations remain underexplored.

Digital/technological enablers of ESG.

ESG-aligned regeneration emerging as a niche hotspot.

The table summarizes the results of the bibliometric keyword co-occurrence analysis. Nine clusters were identified, dominated by sustainability-oriented concepts such as “urban planning,” “sustainable development,” and “sustainable cities.” While core research focuses on urban sustainability, emerging clusters highlight governance, GIS applications, smart cities, and regeneration. This distribution illustrates both the consolidation of ESG within sustainability discourses and the relative underexploration of governance and digital tools in urban planning contexts.

Discussion, Conclusion and Future Scope

This review has demonstrated that ESG frameworks are no longer confined to the domain of corporate accountability, but are increasingly shaping urban planning, real estate, and territorial governance. The findings reveal that ESG functions simultaneously as a financial instrument, a governance paradigm, and a spatial strategy, creating both opportunities and tensions in its application. A central contribution of this synthesis is the recognition of ESG’s spatiality: rather than remaining a firm-level disclosure tool, ESG practices are embedded in geographies of investment, infrastructure, and inequality. This perspective resonates with the arguments of Harnett (2018) and Blok (2020), who highlight how ESG discourses are situated within broader financial and environmental imaginaries that privilege certain urban cores, particularly in the Global North, while marginalizing rural and peripheral areas. Empirical studies such as those of Gamidullaeva (2024) and Ovsiannikov (2020) illustrate how these spatial imbalances materialize through labor mobility and urban growth patterns that concentrate opportunity in metropolitan regions at the expense of regional resilience, raising critical concerns about equity and institutional capacity.

The review also highlights the growing significance of ESG within the real estate and infrastructure sectors, where the capacity to attract capital is increasingly contingent on demonstrable sustainability credentials. As Newell and Marzuki (2022) and Nanda (2023) observe, ESG-aligned investment is becoming a dominant force in global property markets, even as gaps in transparency and reporting remain persistent. Methodological innovations are beginning to address this challenge. Rossi et al. (2024) and Morelli et al. (2025), for example, advance spatially embedded scoring systems and spatiotemporal clustering models that integrate financial performance with place-sensitive sustainability indicators. These models offer tools for investors and policymakers to evaluate projects not only in terms of profitability but also in relation to resilience, environmental impact, and social equity. Yet, as Penati (2022) and Noh and Kim (2023) caution, the translation from ESG perception to actual implementation is uneven, reflecting both institutional inertia and the cultural challenges of embedding ESG principles into practice.

A further dimension of this review has been the identification of green gentrification as a recurring paradox in ESG-driven urbanism. Bressane et al. (2024), Reed-Thryselius (2023), and Cucca et al. (2023) each point to the unintended socio-spatial consequences of decarbonization strategies and Nature-Based Solutions (NbS), which, while environmentally progressive, risk displacing vulnerable communities and reproducing inequalities. Oscilowicz et al. (2025) offer pathways through community governance models that anchor ESG adoption in participatory practices, while Parish (2023) critiques the fiduciary dimensions of ESG that often prioritize investor returns over local needs. Together, these contributions underscore that ESG implementation cannot be detached from questions of social justice and distributive equity.

Governance emerges as another critical area of transformation, where ESG is increasingly integrated into municipal and state-led initiatives. De Nicolò (2020), Alatagi (2021), and Lucas (2022) highlight how frameworks designed for corporate accountability can be adapted to public sector institutions, enabling municipalities, state-owned enterprises, and smart city programs to align with ESG metrics. These studies show that tools such as LEED for Cities, GRESB, and ESG investment-readiness indices can enhance municipal transparency, accountability, and investment appeal, while also opening space for more inclusive service delivery. Building on this operational foundation, Esmaeilpour Zanjani et al. (2021) conceptualize “good sustainable urban governance” as a normative model rooted in ESG principles, emphasizing transparency, legitimacy, and civic engagement as indispensable components of sustainable urbanism. Xu and Zhao (2024), writing in the context of China’s Greater Bay Area, further expand ESG’s potential by embedding it into resilience frameworks that integrate low-carbon transitions, ecological restoration, digital education, health reform, and fintech-enabled governance. These innovations illustrate how ESG can be mobilized not only as a planning tool but also as a strategic framework for resilience and adaptive urban transformation.

The European context provides particularly fertile ground for both innovation and critique. Battisti (2023) demonstrates how ESG pillars can be aligned with SDG indicators in housing regeneration projects in Florence, yielding localized, multidimensional assessment frameworks that integrate environmental, social, and governance objectives. Kurchenkov, Koneva, and Fetisova (2022) extend this logic to rural contexts with their ESGEH model, which incorporates “Economy” and “Heritage” as additional dimensions, thereby acknowledging the demographic, cultural, and institutional challenges of peripheral regions. Bocca and Massimiano (2024) emphasize the role of multi-actor frameworks in aligning land-use planning with the Paris Agreement and the SDGs, while Obushnyi and Novikov (2024) highlight how digital monitoring and smart platforms enhance transparency and attract capital to regeneration projects. Peeters(2024), however, cautions that the EU Taxonomy remains overly narrow, focusing on building-level performance while neglecting ecological connectivity, spatial justice, and regional-scale sustainability. David, Wang, and David Jr. (2024) reinforce this critique by showing that ESG evolution correlates strongly with GDP, underscoring the importance of culturally adaptive frameworks that avoid universalist templates and instead recognize socio-economic heterogeneity across European regions. Vardopoulos et al. (2023), through GIS-based photointerpretation of Cyprus, add methodological evidence that compact city principles can reinforce ESG-aligned urban growth, while Wan et al. (2023) situate these debates within a broader global trajectory of ESG scholarship, highlighting the exponential rise of publications, thematic clusters around finance, governance, and disclosure, and persistent challenges such as score divergence and greenwashing.

Taken together, these contributions show that ESG is evolving into a hybrid paradigm that bridges corporate finance, urban governance, and spatial planning. Yet its transformative potential depends on addressing key limitations. For policy and practice, the findings suggest the need for stronger institutional embedding of ESG principles into urban governance systems, including their integration into zoning, procurement, and infrastructure investment. Public–private partnerships must be conditioned on delivering measurable social and environmental benefits, while participatory mechanisms are needed to ensure that ESG adoption reflects community priorities rather than investor logics alone. Regulatory frameworks such as the EU Taxonomy require broadening beyond building-level metrics to encompass territorial indicators of ecological connectivity and social equity, while urban regeneration strategies must explicitly mitigate risks of green gentrification through redistributive housing and inclusive planning instruments.

For future research, several priorities emerge from this review. Greater geographic diversification is essential, as ESG frameworks remain predominantly analyzed in European and North American contexts, leaving the Global South underexplored despite its growing relevance for global urbanization and climate agendas. Methodological innovation is another priority, with a need for mixed-method approaches that reconcile composite ESG scores with disaggregated, place-sensitive data using GIS, remote sensing, and longitudinal socio-spatial analysis. Finally, the normative orientation of ESG scholarship must be strengthened by explicitly linking it to debates on spatial justice, democratic governance, and cultural adaptation, ensuring that ESG is not only a disclosure mechanism but also a tool for equitable and resilient urban futures.

In practical terms, the evidence presented in this review suggests several immediate policy directions for embedding ESG more effectively into urban development. First, municipalities and regulators should broaden the scope of ESG evaluation to include territorial indicators, ensuring that zoning codes, infrastructure investment, and procurement systems are explicitly aligned with environmental resilience, social inclusion, and transparent governance.

Second, financial instruments such as green and social bonds should be conditioned on measurable social outcomes, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of greenwashing while enhancing accountability. Third, urban regeneration projects must be coupled with redistributive housing policies and participatory planning mechanisms to prevent green gentrification and ensure that ESG adoption contributes to social equity.

For practice, developers, investors, and planners should adopt multi-scalar frameworks that link project-level assessments (e.g., LEED, BREEAM) with regional metrics of connectivity, cultural preservation, and economic resilience. Looking ahead, future research should pursue three key directions: (i) greater geographic diversification to capture ESG dynamics in underexplored Global South contexts; (ii) methodological innovation that integrates GIS, remote sensing, and longitudinal socio-economic data with traditional ESG scores; and (iii) normative reorientation of ESG research toward spatial justice and cultural adaptability, ensuring that ESG evolves beyond compliance into a governance paradigm for equitable, resilient, and place-sensitive urban futures.

In conclusion, ESG frameworks are at a critical juncture. They have demonstrated their capacity to mobilize capital, structure governance, and reframe urban development, but they also risk reproducing inequalities if applied narrowly or technocratically. By embedding ESG within participatory governance structures, aligning it with territorial and cultural contexts, and refining its methodological tools, policymakers, practitioners, and researchers can advance ESG as a transformative paradigm capable of reshaping urban and regional development into a more sustainable, equitable, and resilient form.

References

- Alatagi, A. S., Dwivedi, M. A., & Bhavsar, P. M. D. (2021). Possibilities of using environmental, social, and governance (ESG) framework for urban local governments. [Online].

- Almusaed, A., Almssad, A., & Yitmen, I. (2024). Sustainable built environment and its implications on real estate development: A comprehensive analysis. In Integrative Approaches in Urban Sustainability— Architectural Design, Technological Innovations and Social Dynamics in Global Contexts. IntechOpen.

- Antipin, I., Vlasova, N., & Shishkina, E. (2023). Real estate market as an indicator of urban sustainable development. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 451, p. 02006). EDP Sciences.

- Battisti, F. SDGs and ESG criteria in housing: Defining local evaluation criteria and indicators for verifying project sustainability using Florence metropolitan area as a case study. Sustainability 2023, 15(12), 9372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D. Propondo EESSGG para o desempenho da gestão urbana orientada à stakeholders: uma perspectiva teórica. Revista de Gestão Ambiental e Sustentabilidade 2023, 12(1), e23099–e23099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertholdo, E., & de Castro Marins, K. R. (n.d.). Mapping technological urban clustering using support vector machines (SVM) algorithm, applied to the city of São Paulo, in Brazil.

- Bhattacharya, S., & Sachdev, B. K. (2024). Sustainable land management in Industry 5.0 and its impact on environment, society, and governance (ESG). In Sustainable Development in Industry and Society 5.0: Governance, Management, and Financial Implications (pp. 113–132). IGI Global.

- Blok, A. Urban green gentrification in an unequal world of climate change. Urban Studies 2020, 57(14), 2803–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, A.; Massimiano, L. ESG principles and urban regeneration: A framework for sustainable cities; ACCADEMIA, 2024; pp. 326–327. [Google Scholar]

- Bressane, A., Pinto, J. P. D. C., & de Castro Medeiros, L. C. (2024). Countering the effects of urban green gentrification through nature-based solutions: A scoping review. Nature-Based Solutions, 100131.

- Chigarev, B. Identification of actual bibliometric/scientometric issues based on 2018–2022 data from the Lens platform by building key term co-occurrence network. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cucca, R.; Friesenecker, M.; Thaler, T. Green gentrification, social justice, and climate change in the literature: Conceptual origins and future directions. Urban Planning 2023, 8(1), 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L. K.; Wang, J.; David, V., Jr. Economic and governance dimensions of ESG performance: A comparative study in the developing and European countries. The Journal of Developing Areas 2024, 58(4), 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicolò, R. Exploring ESG as a tool for public administrations: Innovative strategies for the sustainable urban development; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Diana, L. From policies to practices: A journey to ESG implementation; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R. G.; Lee, L. E.; Stroehle, J. C. The social origins of ESG: An analysis of Innovest and KLD. Organization & Environment 2020, 33(4), 575–596. [Google Scholar]

- Esmailpour, N.; Goodarzi, G.; Esmailpour Zanjani, S. The model of good sustainable urban governance based on ESG concepts. International Journal of Urban Management and Energy Sustainability 2021, 2(4), 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W.; Luo, C.; Yan, M. Does urban agglomeration promote the development of cities? Evidence from the urban network externalities. Sustainability 2023, 15(12), 9850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamidullaeva, L. Interlinkages between urbanization and regional sustainable development. Eurasian Journal of Economic and Business Studies 2024, 68(2), 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazioglu Hamis, S. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scoring system: Towards net-zero city targets. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Grishina, V., Amelicheva, D., & Tikhanov, N. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and social investment in the urban environment. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 128, p. 01021). EDP Sciences.

- Harnett, E. Responsible investment and ESG: An economic geography. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jelks, N. T. O.; Jennings, V.; Rigolon, A. Green gentrification and health: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(3), 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R., Khanna, H., Sisodiya, V., & Azad, A. (2025). Integrating ESG frameworks into urban governance: A master plan for sustainable development and green investment in Ramnagar, Uttarakhand. Uttarakhand.

- Kauskale, L.; Zvirgzdins, J.; Geipele, I. The real estate market and its influencing factors for sustainable real estate development: A case of Latvia. Baltic Journal of Real Estate Economics and Construction Management 2022, 10(1), 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtseva, O. V.; Malikova, O. I.; Egorov, E. G. Sustainable urban development and ecological externalities: Russian case. Geography, Environment, Sustainability 2021, 14(1), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurchenkov, V. V.; Koneva, D. A.; Fetisova, O. V. ESG-principles as a tool for integrated sustainable development of rural areas. J. Volgogr. State University. Econ 2022, 24(3), 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsenko, E., Ismagulova, S., & Ivanova, E. (2022). Urban super-cluster as a novel approach to clustering in megapolises: The case of Moscow Innovation Cluster. In Clusters and Sustainable Regional Development (pp. 176–197). Routledge.

- Kuznetsov, N., Tyaglov, S., Rodionova, N., & Bukhov, N. (2023). Development of the large cities in the context of the implementation of the ESG framework. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 435, p. 01004). EDP Sciences.

- Liao, W. C.; Zheng, S. Sustainable real estate and urban development in Asia. Journal of Real Estate Research 2024, 46(3), 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, D. Spatial and temporal characteristics, spatial clustering and governance strategies for regional development of social enterprises in China. Heliyon 2024, 10(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, J. M. ESG, state-owned enterprises and smart cities. In The Palgrave Handbook of ESG and Corporate Governance; Springer, 2022; pp. 415–438. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, J. ESG and real estate. Doctoral dissertation, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, C.; Boccaletti, S.; Maranzano, P.; Otto, P. Multidimensional spatiotemporal clustering – An application to environmental sustainability scores in Europe. Environmetrics 2025, 36(2), e2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.; Sanderford, D. A summary of recent urban form literature and discussion of the implications for real estate developers and investors. Journal of Real Estate Literature 2020, 28(1), 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G.; Marzuki, M. J. The increasing importance of environmental sustainability in global real estate investment markets. Journal of Property Investment & Finance 2022, 40(4), 411–429*. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G.; Nanda, A.; Moss, A. Improving the benchmarking of ESG in real estate investment. Journal of Property Investment & Finance 2023, 41(4), 380–405*. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obushnyi, S.; Novikov, A. Influence of IT solutions on ESG real estate development and investment attractiveness of the urban projects. Єврoпейський наукoвий журнал Екoнoмічних та Фінансoвих іннoвацій 2024, 1(13), 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscilowicz, E.; Anguelovski, I.; García-Lamarca, M.; Cole, H. V.; Shokry, G.; Perez-del-Pulgar, C.; Argüelles, L.; Connolly, J. J. Grassroots mobilization for a just, green urban future. Journal of Urban Affairs 2025, 47(2), 347–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ovsiannikov, J. Centre-peripheral regional development and human capital distribution: Peripheral experience within functional region of Stockholm. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, C.; Nascimento, L. Historical context of social, environmental and corporate governance (ESG) and its impacts on organizations: A literature review. n.d. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Jia, H. Urban layer structure and sustainable development: A global perspective; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, J. Fiduciary activism from below: Green gentrification, pension finance, and the possibility of just urban futures. Urban Planning 2023, 8(1), 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M. U. J. Enhancing the EU taxonomy for sustainable real estate; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Penati, T. The sustainability of the retail real estate sector: Study and analysis of the ESG factors. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pjeshka, C. Integrating ESG factors in urban regeneration projects: A path to sustainable development. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, J.; Nesbitt, L.; Sax, D. How well do we know green gentrification? A systematic review of the methods. Progress in Human Geography 2022, 46(4), 960–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed-Thryselius, S. A review of environmental gentrification ills and the 'Just Green Enough' approach. International Journal of Community Well-Being 2023, 6(4), 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Byrne, J. G.; Christiaen, C. Breaking the ESG rating divergence: An open geospatial framework for environmental scores. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 349, 119477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, M.; Zhang, H. A study of ESG. SSRN 2025, 5239259. [Google Scholar]

- Sangkyu, N. O. H.; Jaetae, K. I. M. A study on ESG perception of real estate managers. 융합경영연구 2023, 11(6), 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, R.; Karam, A.; Xiao, Y.; Caldwell, A. S. Research and citation trends in sustainable real estate. Journal of Real Estate Literature 2023, 31(1), 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklavos, G.; Zournatzidou, G.; Ragazou, K.; Spinthiropoulos, K.; Sariannidis, N. Next-generation urbanism: ESG strategies, green accounting, and the future of sustainable city governance—A PRISMA-guided bibliometric analysis. Urban Science 2025, 9(7), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Dias, F.; de Aguiar Dutra, A. R.; Vieira Cubas, A. L.; Ferreira Henckmaier, M. F.; Courval, M.; de Andrade Guerra, J. B. S. O. Sustainable development with environmental, social and governance: Strategies for urban sustainability. Sustainable Development 2023, 31(1), 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardopoulos, I.; Ioannides, S.; Georgiou, M.; Voukkali, I.; Salvati, L.; Doukas, Y. E. Shaping sustainable cities: A long-term GIS-emanated spatial analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15(14), 11202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Dawod, A. Y.; Chanaim, S.; Ramasamy, S. S. Hotspots and trends of environmental, social and governance (ESG) research: A bibliometric analysis. Data Science and Management 2023, 6(2), 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; He, B. Spatial spillover effects of digital finance on corporate ESG performance. Sustainability 2024, 16(16), 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. L.; Phillips-Fein, K. Environmental, social, and corporate governance: A history of ESG standardization from 1970s to the present. Undergraduate senior thesis, Columbia University, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Hao, C.; Li, Y.; Ge, C.; Duan, X.; Ren, J.; Han, C. Spatio-temporal coupling coordination analysis between local governments' environmental performance and listed companies' ESG performance. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2025, 110, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2024). Resilient cities governance when encountering external turbulence in the Greater Bay Area of China: An ESG perspective. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 512, p. 01021). EDP Sciences.

- Yang, W.; Hei, Y. Research on the impact of enterprise ESG ratings on carbon emissions from a spatial perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16(9), 3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ma, S.; Cheng, K.; Kyriakopoulos, G. L. An evaluation system for sustainable urban space development based in green urbanism principles—A case study based on the Qin-Ba mountain area in China. Sustainability 2020, 12(14), 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C. Assessing the effects of urban digital infrastructure on corporate ESG performance: Evidence from the broadband China policy. Systems 2023, 11(10), 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lan, T.; Wu, W. Exploring the influence and impact factors of park green spaces on the urban functional spatial agglomeration: A case study of Hangzhou. Sustainability 2025, 17(4), 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupi, M., & Celani, P. (2024). The ESG approach for planning, design and correct management of green area. In International Symposium: New Metropolitan Perspectives (pp. 336–342). Springer.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).