Introduction

Laryngomalacia is the most frequent cause of inspiratory stridor during infancy. Due to the fragility of the supraglottic structures, inspiratory collapse or narrowing of the larynx may occur, leading to cyanosis, feeding difficulty, poor weight gain, respiratory distress, and obstructive sleep apnea [

1,

2].

In mild cases, spontaneous improvement is expected, and careful observation is usually sufficient. However, in severe cases, surgical intervention may be required [

3,

4,

5]. Conventional surgical treatments include supraglottoplasty using laser or microdebrider techniques, epiglottopexy, and tracheostomy. Although these procedures can be effective, each is associated with specific disadvantages, and a safer, less invasive, and more definitive treatment approach is desirable.

Supraglottoplasty involves resection or contraction of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, or arytenoid mucosa using a CO₂ laser or microdebrider to enlarge the airway. While this approach is minimally invasive and can be performed endoscopically, postoperative restenosis, aspiration due to excessive resection, and supraglottic stenosis remain concerns [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Epiglottopexy stabilizes the epiglottis by anterior or superior fixation to prevent airway collapse and can provide immediate airway improvement. However, the risk of swallowing dysfunction and the potential need for reoperation with growth are recognized limitations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. A serious complication common to these procedures is supraglottic stenosis or edema, which may ultimately necessitate tracheostomy in severe cases. Although tracheostomy provides reliable airway control, it significantly impairs long-term quality of life and is therefore reserved for the most severe, treatment-refractory cases [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Mukai et al. reported that surgical treatment for ankyloglossia with deviation of the epiglottis and larynx (ADEL) using correction of glosso-larynx (CGL) improves respiratory function by anterior traction of the larynx, preventing supraglottic collapse, with favorable outcomes and minimal complications [

15,

16]. This procedure involves incision of the genioglossus muscle bundle, altering the position of the hyoid bone and tongue, thereby stabilizing the airway. It is a simple, minimally invasive technique that does not require an external cervical incision.

However, clinical experience with this procedure remains limited, and further accumulation of cases is needed to establish its efficacy and safety. Here, we report a case of severe laryngomalacia successfully treated with CGL.

Case Presentation

A 2-month-old female infant was referred with snoring, obstructive sleep apnea, difficulty initiating sleep, shallow sleep, feeding difficulties, poor weight gain, coughing, and cyanosis during crying.

Perinatal History

The patient was born at 38 weeks and 2 days of gestation by normal vaginal delivery in the cephalic position. The duration of labor was 2 hours and 22 minutes, and birth weight was 2,878 g. There were no remarkable prenatal or perinatal complications. She was the second child; the first child was healthy.

From the first day of life, frequent regurgitation and poor facial coloration were noted, but no abnormalities were identified, and she was discharged on day 5 with a body weight of 2,772 g (breastfed). After discharge, frequent regurgitation, abdominal distension, and sleep apnea were observed.

At 25 days of age, she presented to an emergency department due to poor feeding and marked abdominal distension. Constipation was diagnosed, and symptoms temporarily improved after enema. At one month of age, respiratory distress during sleep, feeding difficulty, choking, mottled skin appearance, and poor weight gain were noted. Weight gain was approximately half of the expected rate.Despite ongoing symptoms, she was referred to our clinic at 59 days of age.

Initial Examination

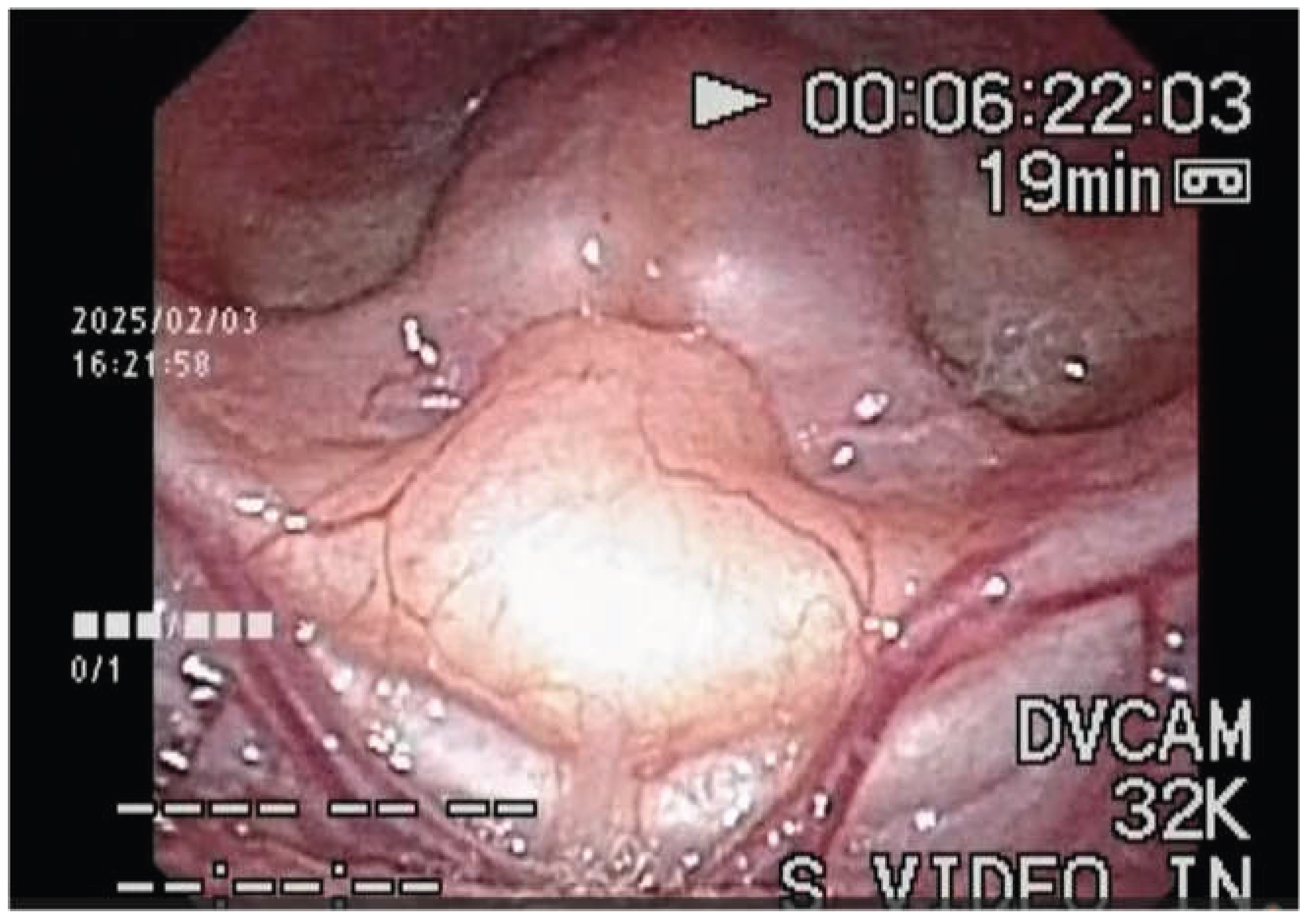

At presentation, poor facial coloration and inspiratory stridor during crying were observed. Oxygen saturation during feeding ranged from 93% to 98%, decreasing to 91% during crying. Flexible laryngoscopy revealed inspiratory collapse of the epiglottis into the glottis, causing airway obstruction, consistent with Olney classification type 3 laryngomalacia [

17] (

Figure 1). (

Supplementary Video 1.)

Although epiglottopexy was considered, the parents expressed concern regarding potential severe complications. After discussion, CGL as described by Mukai et al. was proposed as an alternative. Written informed consent was obtained.

Surgical Procedure

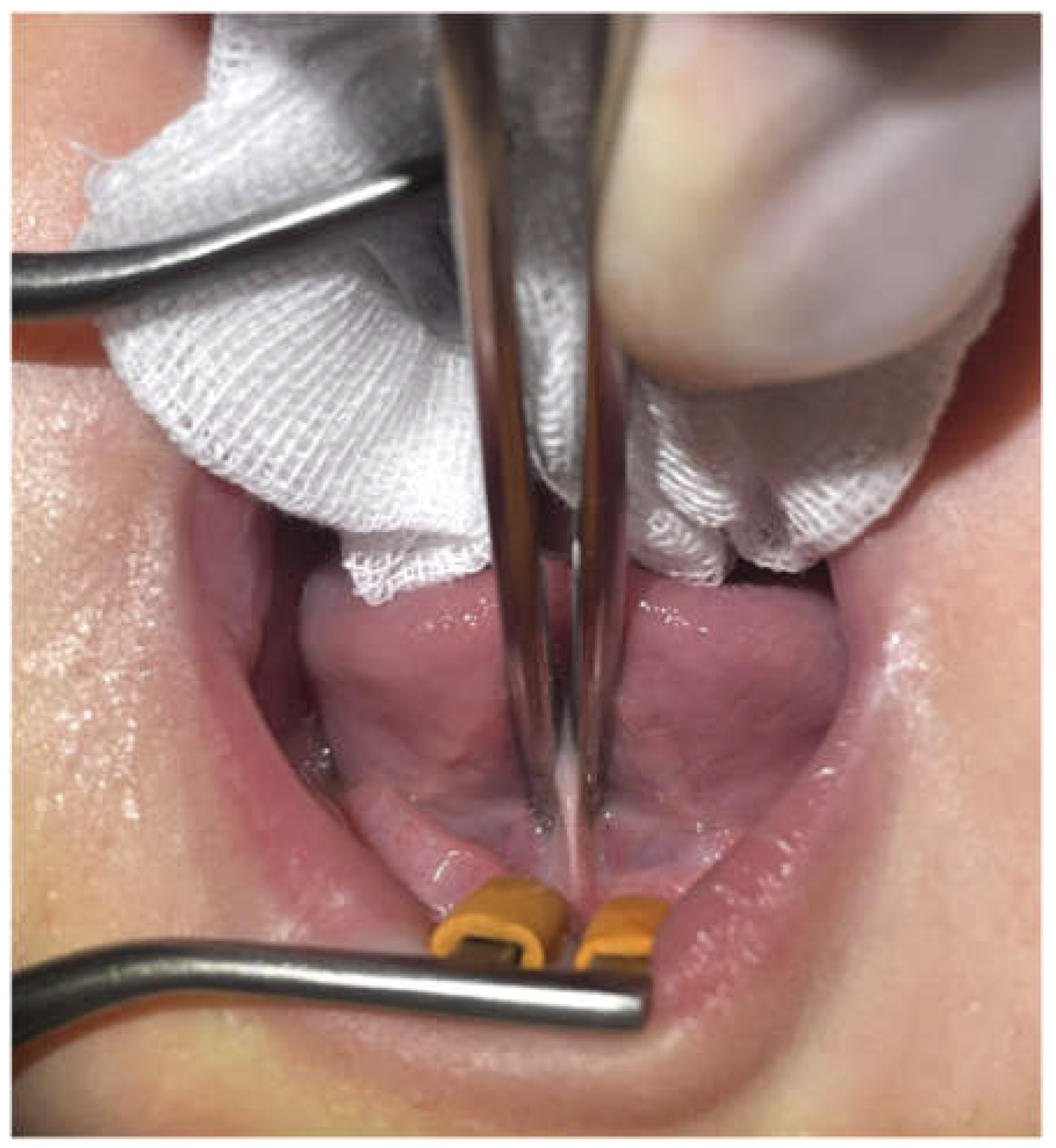

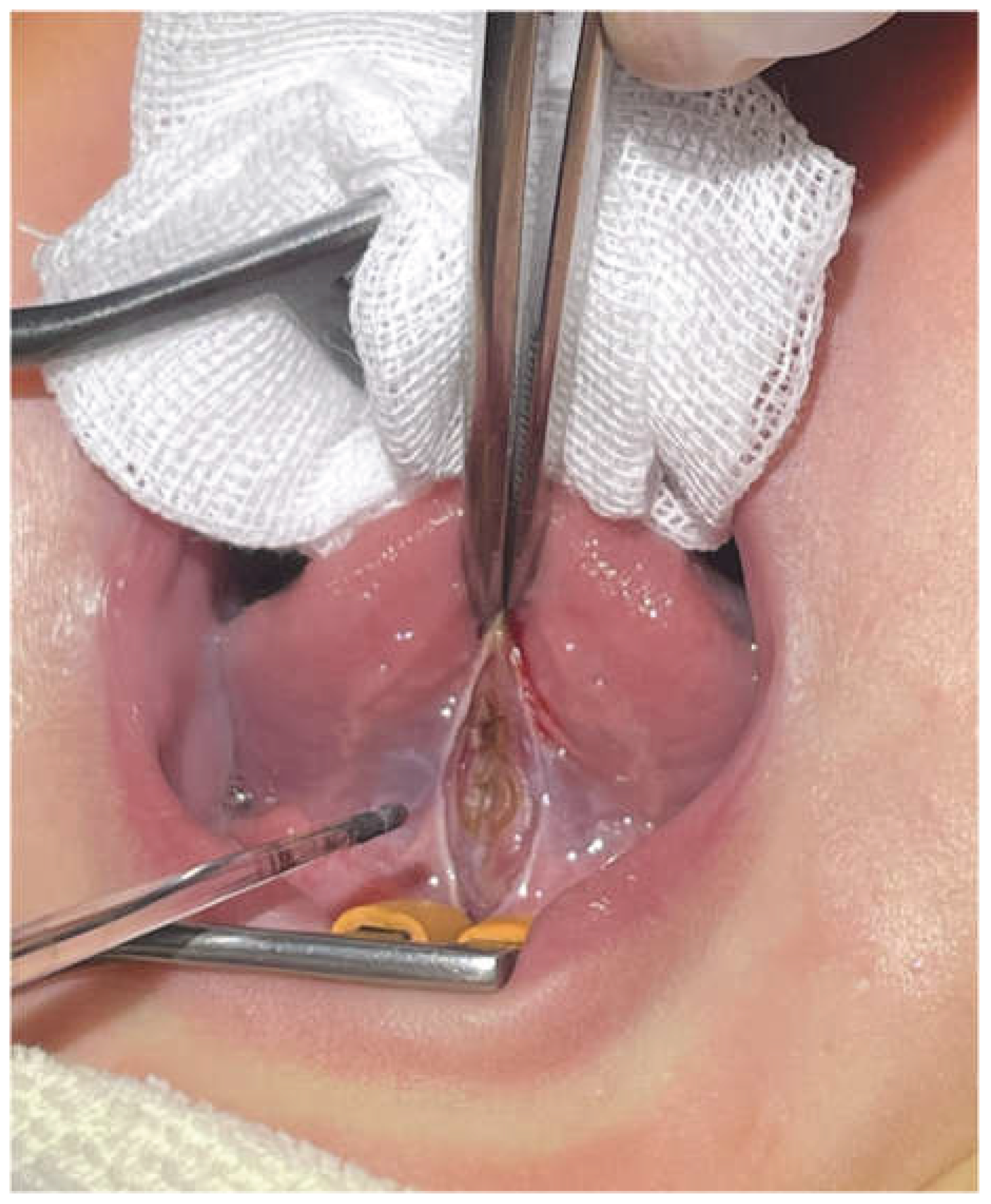

CGL was performed on postnatal day 60 (the day after the initial consultation). The patient was placed in the supine position, and Xylocaine jelly (1 mg) was applied to the floor of the mouth for infiltration anesthesia. The lingual frenulum was incised using a diode laser, followed by exposure of the genioglossus muscle. A single layer of the genioglossus muscle bundle was incised (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

No bleeding was observed, and the procedure was completed uneventfully. The operative time was approximately 5 minutes.

Postoperative Course

Immediately after the surgery, inspiratory stridor was relieved; however, due to transient agitation caused by the procedure, intense crying and transient hypopnea were observed. The patient was placed in a sitting position with continuous SpO₂ monitoring, which fluctuated between 91% and 100%. Oxygen was administered via mask at 3 L/min and discontinued after 3 minutes once SpO₂ stabilized at 100%.

Although inspiratory stridor was absent, SpO₂ variability persisted, and parental concern led to referral and admission to another pediatric hospital for observation. During hospitalization, conservative management for gastroesophageal reflux was provided, including feeding posture guidance, administration of mosapride and rikkunshito, right lateral positioning after feeding, and enemas. Upper airway obstruction symptoms were not prominent. The patient was discharged after a 4-day hospitalization for postoperative observation.

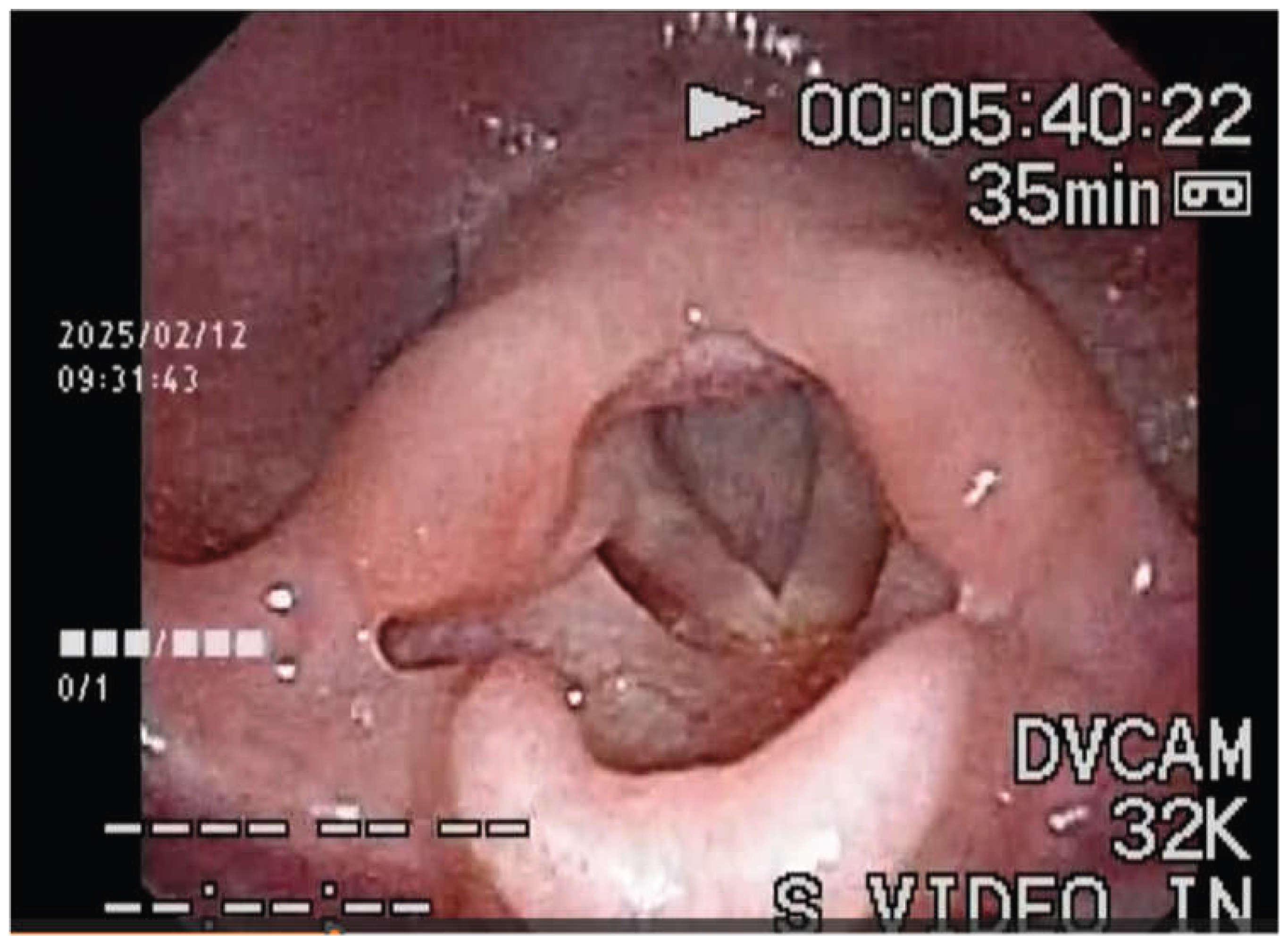

At postoperative day 8, follow-up examination showed marked improvement. Facial coloration was normal, feeding difficulties resolved, cyanosis during crying disappeared, and SpO₂ remained stable at 97–100%. Flexible laryngoscopy demonstrated dramatic improvement, with complete resolution of epiglottic prolapse during inspiration (

Figure 4;

Supplementary Video 2). Findings remained stable at one-month follow-up.

Discussion

Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of inspiratory stridor in infancy. Approximately 90% of mild cases resolve spontaneously by one year of age [

18,

19,

20]. However, severe cases may present with feeding difficulty, failure to thrive, respiratory distress, and obstructive sleep apnea, necessitating active intervention [

3].

Since the 1980s, aggressive surgical management has been adopted in Western countries for severe laryngomalacia [

21,

22,

23]. Supraglottoplasty is commonly used for Olney type 1 and 2, while epiglottopexy is typically reserved for type 3 cases. Although favorable outcomes have been reported, complications such as aspiration, bleeding, granulation, and supraglottic stenosis occur in approximately 4% of cases and may require tracheostomy [

7,

24,

25,

3].

The present case corresponded to Olney type 3 severe laryngomalacia. CGL involves incision of the genioglossus muscle, resulting in anterior displacement of the tongue, anterior-inferior repositioning of the hyoid bone, and expansion of the pharyngolaryngeal airway, thereby improving respiratory function. This anatomical change likely prevented inspiratory epiglottic collapse. The procedure is simple and anatomically rational, suggesting a low risk of serious complications. The transient postoperative hypopnea observed in this case was likely due to vigorous crying immediately after surgery.

A distinctive feature of CGL is its focus on the relationship between the genioglossus muscle and the hyoid bone. While conventional surgery for ankyloglossia usually does not involve muscle incision, CGL extends beyond frenotomy to include incision of the deeper genioglossus muscle bundle, thereby altering tongue and hyoid positioning and improving airway patency. This approach may offer sustained therapeutic effects. Therefore, the term “lingual frenulum and genioglossus release” may more accurately describe this procedure.

Potential long-term complications of genioglossus muscle incision include tongue movement disorders, articulation difficulties, scar contracture, and re-adhesion; however, such complications are rare with this technique [27].

This report has limitations, including the single-case design and limited follow-up duration. Optimal timing of intervention and long-term outcomes require further investigation. Although some cases of laryngomalacia may improve spontaneously, the early months of life are critical for auditory, speech, and neurodevelopmental milestones. Hypoxia during this period confers no developmental benefit. Procedures such as CGL, which can safely alleviate airway obstruction in severe cases, may therefore be considered as an early intervention option.

Conclusions

Correction of glosso-larynx (CGL) was effective in treating severe laryngomalacia in this infant, with rapid improvement and no major complications. Accumulation of further cases is necessary to establish the safety and efficacy of this minimally invasive procedure.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Meirikai Tokyo Yamato Hospital. Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video 1: Flexible endoscopic laryngeal findings at the initial presentation. Supplementary Video 2: Flexible endoscopic laryngeal findings after surgery.

References

- Dobbie AM, White DR. Laryngomalacia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(4):893–902.

- Bedwell J, Zalzal GH. Laryngomalacia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2016;25(3):119–122.

- Ayari, S.; Aubertin, G.; Girschig, H.; Abbeele, T.V.D.; Denoyelle, F.; Couloignier, V.; Mondain, M. Management of laryngomalacia. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2013, 130, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Landry, A.M.; Thompson, D.M. Laryngomalacia: Disease Presentation, Spectrum, and Management. Int. J. Pediatr. 2012, 2012, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Jain, S. Management of Stridor in Severe Laryngomalacia: A Review Article. Cureus 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Senders CW, Navarrete ML. Laser supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia: A retrospective review of 62 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;58(3):211–218.

- Richter GT, Thompson DM. The surgical management of laryngomalacia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(5):837–864.

- Zalzal, G.H.; Anon, J.B.; Cotton, R.T. Epiglottoplasty for the Treatment of Laryngomalacia. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1987, 96, 72–76. [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Lippert, B.; Dünne, A.; Ankermann, T.; Folz, B.; Seyberth, H. Epiglottopexy for the treatment of severe laryngomalacia. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2002, 259, 459–464. [CrossRef]

- Seid, A.B.; Park, S.M.; Kearns, M.J.; Gugenheim, S. Laser division of the aryepiglottic folds for severe laryngomalacia. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 1985, 10, 153–158. [CrossRef]

- Denoyelle F, et al. Surgical management of severe laryngomalacia: Indications, techniques and results. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(9):1369–1373.

- Valera et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of supraglottoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(5):489–493.

- Olney DR, et al. Supraglottoplasty outcomes in children with severe laryngomalacia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;56(4):395–402.

- Veroul, E.; Amaddeo, A.; Leboulanger, N.; Gelin, M.; Denoyelle, F.; Thierry, B.; Fauroux, B.; Luscan, R. Noninvasive Respiratory Support as an Alternative to Tracheostomy in Severe Laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope 2021, 132, 1861–1868. [CrossRef]

- Mukai S, Mukai C, Asaoka K. Ankyloglossia with deviation of the epiglottis and larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1991;153:1–20. PMID: 2024905.

- Mukai, S.; Nitta, M. Correction of the Glosso-Larynx and Resultant Positional Changes of the Hyoid Bone and Cranium. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2002, 122, 644–650. [CrossRef]

- Olney DR,Greinwald JH, Jr, Smith RJ et al Laryngomalacia and its treatment.Laryngoscope.1999;109.1770-1775.

- MacLean, J.E. Laryngomalacia in infancy improves with increasing age irrespective of treatment. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 619–620. [CrossRef]

- Holinger LD, Konior RJ. Laryngomalacia: A cause of stridor in infants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98(12):935–940.

- Thompson, D.M. Laryngomalacia: factors that influence disease severity and outcomes of management. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 18, 564–570. [CrossRef]

- Holinger, L.D.; Konior, R.J. Surgical management of severe laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope 1989, 99, 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Mancuso RF, Choi SS, Zalzal GH. Supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia: Indications and outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122(7):715–718.

- Kay, D.J.; Goldsmith, A.J. Laryngomalacia: A Classification System and Surgical Treatment Strategy. Ear, Nose Throat J. 2006, 85, 328–336. [CrossRef]

- Denoyelle F, et al. Supraglottoplasty in children: Indications, technique, and results. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(10):1632–1636.

- Mukai, S. Positional changes in the hyoid bone, hypopharynx, cervical vertebrae, and Cranium before and after correction of glosso-larynx (CGL). Arch. Otolaryngol. Rhinol. 2018, 037–043. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |