Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Patients and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths

- This is the first randomized clinical trial specifically designed to evaluate the optimal dwell time of antimicrobial lock solutions (ALS) in totally implantable venous access ports.

- The study directly quantified intraluminal antimicrobial concentrations in vivo, using standardized high-performance liquid chromatography with urea correction, thereby providing robust pharmacokinetic data under clinical conditions.

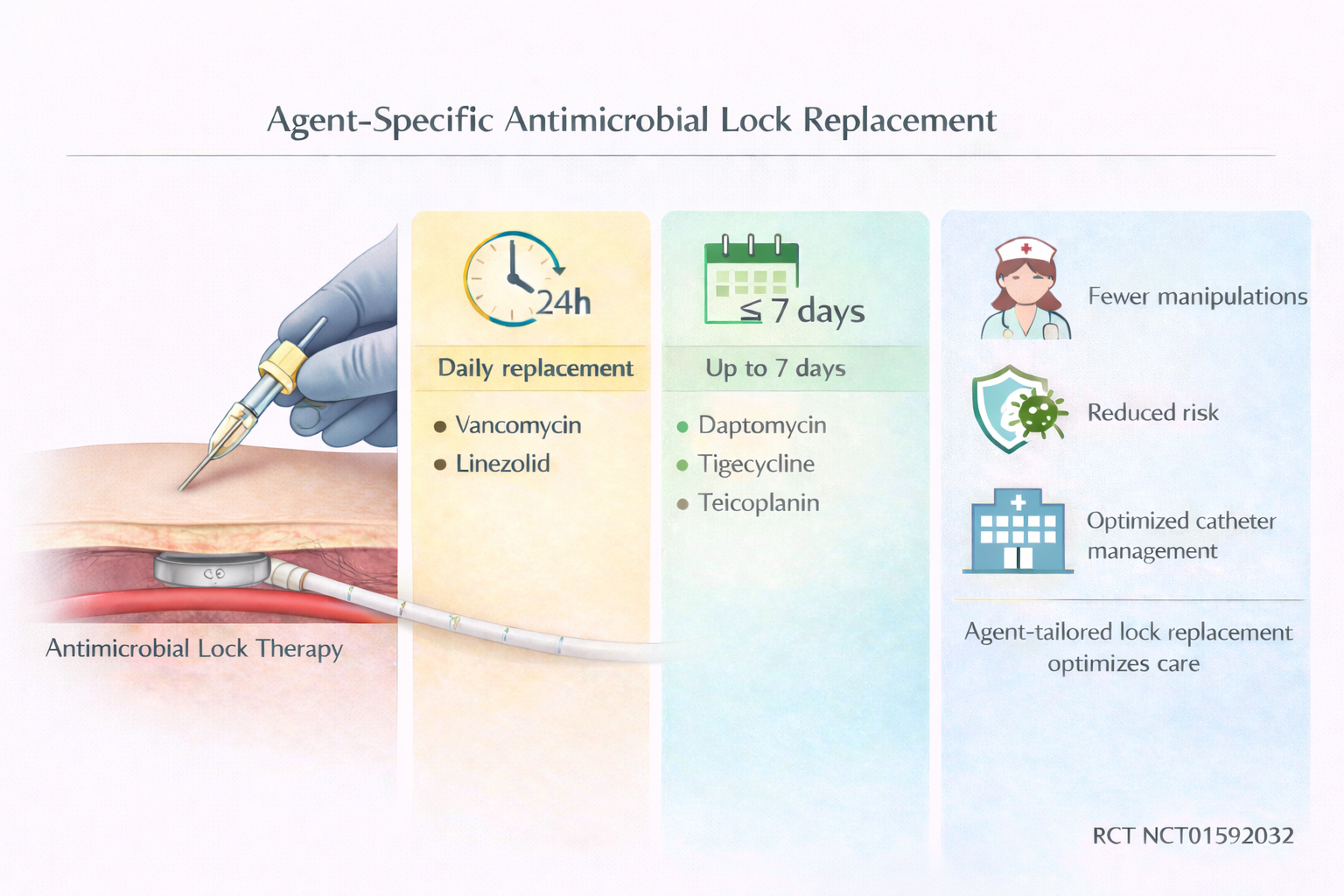

- Multiple antimicrobials commonly used in lock therapy (vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid, daptomycin, tigecycline) were compared simultaneously, allowing drug-specific recommendations for replacement intervals.

- The trial design with stepwise dwell-time escalation enabled the identification of thresholds for loss of efficacy without exposing patients to unnecessary risk.

Limitations

- The sample size within each antimicrobial–dwell time subgroup was limited (n=5 per time point), reducing statistical power and generalizability.

- Port use in the study was restricted to noninfected, newly implanted devices, which may not fully reflect clinical practice in infected or long-term ports.

- Concentration thresholds were based on pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic principles (≥1 mg/mL) rather than direct clinical outcomes, so translation to real-world effectiveness requires caution.

- The 10-day dwell time arm could not be completed due to recruitment constraints, leaving the upper limit of safe dwell times undetermined.

- Findings apply to the antimicrobial concentrations tested, which may not account for alternative formulations, catheter materials, or patient populations.

Clinical Implications

- Replacement intervals for antimicrobial lock solutions (ALS) should be individualized according to the specific agent used.

- Vancomycin and linezolid locks require daily replacement, while teicoplanin, daptomycin, and tigecycline maintain effective concentrations for up to 7 days.

- Extending ALS dwell times could reduce port manipulations, lower healthcare costs, and minimize patient discomfort without compromising efficacy.

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Lee GJ, Hong SH, Roh SY, et al. A case-control study to identify risk factors for totally implantable central venous port-related bloodstream infection. Cancer Res Treat. 2014; 46(3):250–260. [CrossRef]

- Maki, D G; Kluger, D M; Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006; 81(9):1159–1171. [CrossRef]

- Adler A, Yaniv I, Solter E, et al. Catheter-associated bloodstream infections in pediatric hematology-oncology patients: factors associated with catheter removal and recurrence. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006; 28(1):23–28.

- Barbetakis N, Asteriou C, Kleontas A, Tsilikas C. Totally implantable central venous access ports. Analysis of 700 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2011; 104(6):654–656. [CrossRef]

- Chang L, Tsai JS, Huang SJ, Shih CC. Evaluation of infectious complications of the implantable venous access system in a general oncologic population. Am J Infect Control. 2003; 31(1):34–39. [CrossRef]

- Raad I, Hachem R, Hanna H, et al. Sources and outcome of bloodstream infections in cancer patients: the role of central venous catheters. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007; 26(8):549–556. [CrossRef]

- Mermel, Leonard A.; Allon, Michael; Bouza, Emilio; Craven, Donald E.; Flynn, Patricia; O’Grady, Naomi P.; Raad, Issam I.; Rijnders, Bart J. A.; Sherertz, Robert J.; Warren DK. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 49:1–45. [CrossRef]

- Messing, Bernard; Peitra-Cohen, Sophie; Debure, Alain; Beliah, Martine; Bernier J-J. Antibiotic-lock technique: a new approach to optimal therapy for catheter-related sepsis in home-parenteral nutrition patients. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1988; 12(2):185–189. [CrossRef]

- Pozo JL Del, Garcia Cenoz M, Hernaez S, et al. Effectiveness of teicoplanin versus vancomycin lock therapy in the treatment of port-related coagulase-negative staphylococci bacteraemia: a prospective case-series analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009; 34(5):482–485. [CrossRef]

- Pozo JL Del, Rodil R, Aguinaga A, et al. Daptomycin lock therapy for grampositive long-term catheter-related bloodstream infections. Int J Clin Pract. 2012; 66(3):305–308. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Saima; Trautner, Barbara W; Ramanathan, Venkat; Darouiche RO. Pilot Trial of N -acetylcysteine and Tigecycline as a Catheter-Lock Solution for Treatment of Hemodialysis Catheter – Associated Bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008; 29(9):894–897. [CrossRef]

- Haimi-Cohen Y, Husain N, Meenan J, Karayalcin G, Lehrer M, Rubin LG. Vancomycin and ceftazidime bioactivities persist for at least 2 weeks in the lumen in ports: Simplifying treatment of port-associated bloodstream infections by using the antibiotic lock technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001; 45(5):1565–1567. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Hidalgo N, Gavalda J, Almirante B, et al. Evaluation of linezolid, vancomycin, gentamicin and ciprofloxacin in a rabbit model of antibiotic-lock technique for Staphylococcus aureus catheter-related infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010; 65(3):525–530. [CrossRef]

- Droste JC, Jeraj HA, MacDonald A, Farrington K. Stability and in vitro efficacy of antibiotic-heparin lock solutions potentially useful for treatment of central venous catheter-related sepsis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003; 51(4):849–855. [CrossRef]

- Pozo, J.L.; Alonso, M.; Serrera, A.; Hernaez, S.; Aguinaga, A.; Leiva J. Effectiveness of the antibiotic lock therapy for the treatment of port-related enterococci, Gram-negative, or Gram-positive bacilli bloodstream infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009; 63(2):208–212. [CrossRef]

- He J, Gao S, Hu M, Chow DS-L, Tam VH. A validated ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for the quantification of polymyxin B in mouse serum and epithelial lining fluid: application to pharmacokinetic studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013; 68:1104–10. [CrossRef]

- Justo JA, Bookstaver PB. Antibiotic lock therapy: Review of technique and logistical challenges. Infect. Drug Resist. 2014. p. 343–363. [CrossRef]

- Ash SR. Fluid mechanics and clinical success of central venous catheters for dialysis–answers to simple but persisting problems. Semin Dial. 2007; 20(3):237–256. [CrossRef]

- Canut Blasco A, Aguilar Alfaro L, Cobo Reinoso J, Gimenez Mestre MJ, Rodriguez-Gascon A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis in microbiology: a tool for the evaluation of the antimicrobial treatment. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015; 33(1):48–57. [CrossRef]

- Peters, G; Locci RP. Microbial colonization of prosthetic devices. II. Scanning electron microscopy of naturally infected intravenous catheters. Zbl Bakt Hyg, I Abt Orig B. 1981; 173:293–299.

- Armijo JA. Farmacocinética: absorción, distribución y eliminación de los fármacos. In: Flórez J, Armijo JA, Mediavilla A, editors. Farmacol Humana. Barcelona, España: Elsevier Masson; 2008. p. 57–85.

- Cantas L, Shah SQA, Cavaco LM, et al. A brief multi-disciplinary review on antimicrobial resistance in medicine and its linkage to the global environmental microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2013; 4(May 14):96. [CrossRef]

- Polaschegg H-D, Shah C. Overspill of catheter locking solution: safety and efficacy aspects. ASAIO J. 2003; 49:713–715. [CrossRef]

- Polaschegg H-DD. Diffusion study. Hemodial Int. 2004; 8(3):304–305. [CrossRef]

- Polaschegg H-D. Loss of catheter locking solution caused by fluid density. ASAIO J. 2005; 51:230–235. [CrossRef]

- Wagner M, Schilcher G, Ribitsch W, Horina J, Polaschegg HD. In-vivo verification of catheter lock spillage by gravity. 39th EDTNA/ERCA Int. Conf. Dublin, Ireland. Poster P 132.2010.

- Soriano A, Bregada E, Marques JM, et al. Decreasing gradient of antibiotic concentration in the lumen of catheters locked with vancomycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007; 26(9):659–661. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Muñoz A, Aguado JM, López-Martín A, et al. Usefulness of antibiotic-lock technique in management of oncology patients with uncomplicated bacteremia related to tunneled catheters. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005; 24(4):291–293. [CrossRef]

- Onder AM, Chandar J, Billings AA, et al. Comparison of early versus late use of antibiotic locks in the treatment of catheter-related bacteremia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008; 3(4):1048–1056. [CrossRef]

- Cargill JS, Upton M. Low concentrations of vancomycin stimulate biofilm formation in some clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Clin Pathol. 2009; 62(12):1112–1116. [CrossRef]

- Institute C and LS. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Fourth Informational Supplement M100-S24. CLSI. Wayne, PA, USA; 2014.

- Keren I, Shah D, Spoering A, Kaldalu N, Lewis K. Specialized persister cells and the mechanism of multidrug tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004; 186(24):8172–8180. [CrossRef]

- Moreno RB, Rives S, Justicia A, et al. Successful port-a-cath salvage using linezolid in children with acute leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013; 60(9):E103-105. [CrossRef]

- Castagnola E, Bandettini R, Lorenzi I, Caviglia I, Macrina G, Tacchella A. Catheter-related bacteremia caused by methicillin-resistant coagulase negative staphylococci with elevated minimal inhibitory concentration for vancomycin. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010; 29(11):1047–1048. [CrossRef]

- Sofroniadou S, Revela I, Smirloglou D, et al. Linezolid versus vancomycin antibiotic lock solution for the prevention of nontunneled catheter-related blood stream infections in hemodialysis patients: a prospective randomized study. Semin Dial. 2012; 25(3):344–350. [CrossRef]

- Morata L, Tornero E, Martínez-Pastor JC, García-Ramiro S, Mensa J, Soriano A. Clinical experience with linezolid for the treatment of orthopaedic implant infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014; 69(SUPPL1):i47–52. [CrossRef]

- San-Juan R, Fernández-Ruiz M, Gasch O, et al. High vancomycin MICs predict the development of infective endocarditis in patients with catheter-related bacteraemia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017; 72(7):2102–2109. [CrossRef]

- Huang YT, Hsiao CH, Liao CH, Lee CW, Hsueh PR. Bacteremia and infective endocarditis caused by a non-daptomycin-susceptible, vancomycin-intermediate, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 2008; 46(3):1132–1136. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox MH, Winstanley TG, Spencer RC, et al. Binding of teicoplanin and vancomycin to polymer surfaces. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994; 33(3):431–441. [CrossRef]

- Grau S, Gil MJ, Mateu-de Antonio J, Pera M, Marin-Casino M. Antibiotic-lock technique using daptomycin for subcutaneous injection ports in a patient on home parenteral nutrition. J Infect. 2009; 59(4):298–299. [CrossRef]

- Parra-Ruiz J, Bravo-Molina A, Peña-Monje A, Hernández-Quero J. Activity of linezolid and high-dose daptomycin, alone or in combination, in an in vitro model of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012; 67:2682–2685. [CrossRef]

- Kao TM, Wang JT, Weng CM, Chen YC, Chang SC. In vitro activity of linezolid, tigecycline, and daptomycin on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus blood isolates from adult patients, 2006-2008: stratified analysis by vancomycin MIC. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011; 44(5):346–351. [CrossRef]

- LaPlante KL, Mermel L a. In vitro activity of daptomycin and vancomycin lock solutions on staphylococcal biofilms in a central venous catheter model. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007; 22:2239–2246. [CrossRef]

- Raad I, Hanna H, Jiang Y, et al. Comparative activities of daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline against catheter-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus bacteremic isolates embedded in biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007; 51(5):1656–1660. [CrossRef]

- Meije Y, Almirante B, Pozo JL Del, et al. Daptomycin is effective as antibiotic-lock therapy in a model of Staphylococcus aureus catheter-related infection. J Infect. 2014; 68(6):548–552. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F. G.; Corcione, S.; Di Perri, G.; Scaglione F De. Re-defining tigecycline therapy. New Microbiol. 2015; 38(2):121–136.

- Campos RP, Nascimento MM do, Chula DC, Riella MC. Minocycline-EDTA lock solution prevents catheter-related bacteremia in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011; 22(10):1939–45. [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou I, Zipf TF, Hanna H, et al. Minocycline-Ethylenediaminetetraacetate Lock Solution for the Prevention of Implantable Port Infections in Children with Cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36(1):116–119. [CrossRef]

- Singh R, Ray P, Das A, Sharma M. Penetration of antibiotics through Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010; 65(9):1955–1958. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Treatment groups | ||||

| Vancomycin | Teicoplanin | Linezolid | Daptomycin | Tigecycline | |

| Sex [no. (%) of patients] | |||||

| Male | 7 (70) | 12 (60) | 6 (60) | 14 (70) | 8 (40) |

| Female | 3 (30) | 8 (40) | 4 (40) | 6 (30) | 12 (60) |

| Age | |||||

| Mean (yr) | 58 | 57.8 | 62.3 | 48 | 55.2 |

| Median (yr) | 61.8 | 62.9 | 64.2 | 52.7 | 55.1 |

| Underlying malignancy [no. (%) of patients] | |||||

| Solid neoplasia | 10 (100) | 19 (95) | 7 (70) | 15 (75) | 17 (85) |

| Hematologic | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 3 (30) | 5 (25) | 3 (15) |

| Site of port implantation [no. (%) of patients] | |||||

| Right subclavian vein | 6 (60) | 15 (75) | 4 (40) | 9 (45) | 9 (45) |

| Right jugular vein | 2 (20) | 3 (15) | 4 (40) | 4 (20) | 4 (20) |

| Other locations | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 7 (35) | 7 (35) |

| Duration of catheterization prior to randomization (days) | |||||

| Mean | 21.6 | 42.1 | 11.4 | 39.5 | 42.2 |

| Median | 12.6 | 122.5 | 21.1 | 83 | 35.7 |

| Antimicrobial concentration administered | Antimicrobial concentration recovered after dwelling time (mg/ml) | |||||||

| 1 Day | 3 Days | 5 Days | 7 Days | |||||

| media (median) | Pvaluea | media (median) | Pvaluea | media (median) | Pvaluea | Media (median) | Pvaluea | |

| Vancomycin 2 mg/ml |

1548.0 (1537.5) | 0.80 | 646.7 (461.8) | 0.04 | * | * | * | * |

| Teicoplanin 10 mg/ml |

6755.7 (7183.4) | 0.04 | 6201.9 (5684.4) | 0.04 | 7566.6 (7677.1) | 0.13 | 10541.2 (9904.6) | 0.89 |

| Linezolid 1.8 mg/ml |

886.1 (1032.5) | 0.04 | 669.1 (727) | 0.04 | * | * | * | * |

| Daptomycin 5 mg/ml |

4029.3 (4385.8) | 0.04 | 2788.7 (2860) | 0.04 | 2697.6 (2814.9) | 0.04 | 2900.8 (2729.7) | 0.04 |

| Tigecycline 4.5 mg/ml |

2405.5 (2415.9) | 0.04 | 1441.8 (1402) | 0.04 | 1092 (1180.4) | 0.04 | 1101.1 (1062.6) | 0.04 |

| a p values are from the Wilcoxon test. | ||||||||

| * The vancomycin and linezolid groups stopped after 3 days of dwelling time. | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).