1. Introduction

1.1. The Scaling Problem in AI Runtimes

The scaling of contemporary AI systems has historically been framed in terms of hardware availability, compute throughput, and interconnect capacity. Early performance limitations were predominantly attributed to insufficient accelerator density, memory bandwidth, or network fabric capabilities. Substantial advances in accelerator architectures and high-performance interconnects have mitigated many of these constraints, yet large-scale AI deployments continue to exhibit cost escalation, unstable throughput, and non-deterministic runtime behavior [

7,

29]. These phenomena persist even in environments where classical resource bottlenecks are demonstrably absent.

This section analyzes the shift from hardware-centric explanations toward coordination and control as dominant sources of inefficiency. As AI systems scale, execution increasingly depends on the interaction of schedulers, orchestrators, runtime engines, and policy layers operating concurrently across heterogeneous infrastructures. Performance degradation and rising cost per output are therefore not adequately explained by isolated resource shortages but emerge from conflicts and misalignments between distributed control mechanisms. This observation motivates a structural perspective in which control interactions, rather than individual components, constitute the primary locus of instability.

1.2. Scope and Limitations

The scope of this work is deliberately limited to a structural analysis of control-related instability in large-scale AI systems. The article does not propose new scheduling algorithms, runtime architectures, or control mechanisms, nor does it present implementation guidance or vendor-specific recommendations. Instead, the focus is on diagnostic formalization and risk-oriented reasoning, with the goal of establishing a coherent analytical vocabulary for discussing runtime control coherence as a system-level property.

By constraining the analysis to conceptual and structural dimensions, the work aims to complement existing performance and systems research without competing with solution-oriented approaches. The intent is to clarify why certain classes of inefficiencies and instabilities persist despite correct local behavior and sufficient resources, thereby providing a foundation for subsequent empirical or design-focused investigations.

1.3. System Class and Failure Envelope

The analysis applies to a broad class of large-scale AI systems, including distributed training workloads for foundation models [

9,

17], latency-sensitive inference pipelines deployed at scale [

18], agentic orchestration frameworks coordinating multiple model invocations, and multi-tenant AI platforms operating shared infrastructure [

5]. These systems differ in workload characteristics and operational constraints but share a reliance on layered control structures spanning infrastructure, runtime, and policy domains.

The failure envelope considered in this work is defined by three recurring phenomena: cost escalation without proportional increases in effective output, runtime instability in the absence of explicit component failures, and non-deterministic behavior arising from interactions between control layers. Rather than manifesting as discrete faults, these failures present as soft degradation, unpredictable performance variation, and diminished reproducibility. Such effects delineate the boundary conditions under which control coherence becomes a critical determinant of economic and operational outcomes.

2. The Shift from Interconnect-Dominated Failures to Control-Dominated Failures

2.1. Traditional Optimization Assumptions

Traditional approaches to system optimization are grounded in assumptions that treat performance and efficiency as decomposable into largely independent component contributions. Resource bottlenecks are commonly addressed through localized tuning, guided by isolated key performance indicators and component-level attribution [

27]. Within this paradigm, coordination overhead is implicitly assumed to be either negligible, amortizable, or reducible through incremental scaling of resources [

10,

11].

At contemporary scales, these assumptions increasingly fail to hold. As system complexity and heterogeneity grow, optimization decisions taken in isolation interact in non-linear ways, producing effects that cannot be inferred from local metrics alone. The resulting inefficiencies do not arise from misconfigured components but from structural interactions that invalidate the premise of independent optimization. This limitation motivates a shift away from component-centric reasoning toward an analysis of coordination and control as first-order system concerns.

2.2. Runtime Control as an Active System Component

Runtime control is not a passive substrate on which computation executes but an active component of the system that continuously shapes execution behavior. Control decisions influence task placement, resource allocation, retry behavior, and policy enforcement, thereby directly affecting performance and cost characteristics [

13]. These decisions are implemented through multiple interacting control loops operating across distinct temporal and organizational scales.

Extending prior structural analyses of interconnect-induced instability [

4], this subsection characterizes control-dominated failures as the outcome of interactions between control loops with limited visibility and divergent objectives [

14]. Each loop may be locally correct and well-tuned, yet their combined behavior can generate global effects that manifest as instability or inefficiency. In this view, loss of control coherence emerges not from faulty logic but from the structural composition of independently operating control mechanisms.

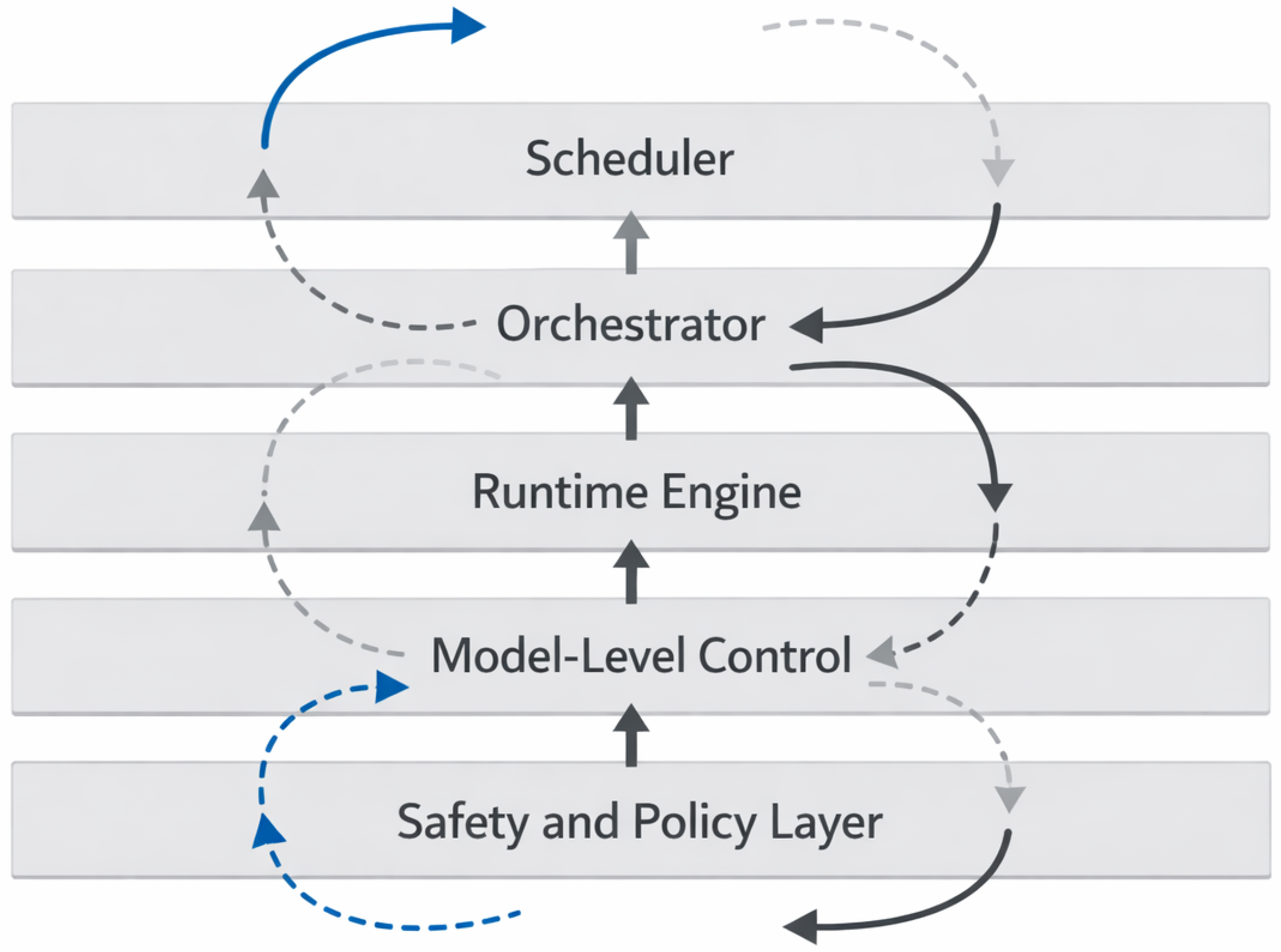

2.3. The Control Plane Stack in Practice

In production AI systems, control is realized through a layered control plane stack encompassing cluster schedulers [

5], orchestration frameworks, runtime execution engines, model-level control mechanisms, and safety or policy enforcement gates. Additional layers such as retry logic, fallback paths, and adaptive scaling policies further contribute to the effective control surface of the system.

This subsection outlines how these layers interact in practice and identifies typical surfaces of conflict and amplification [

6]. Decisions made at one layer may trigger compensatory responses at another, leading to feedback cycles that are difficult to observe or attribute. The cumulative effect of such interactions establishes the conditions under which control-dominated failures arise, even when individual layers operate within their intended specifications.

Figure 1.

Control plane stack and interacting control loops in large-scale AI systems.

Figure 1.

Control plane stack and interacting control loops in large-scale AI systems.

3. Why Classical Metrics Fail

3.1. The Measurement Gap

Conventional observability frameworks are designed to detect localized faults, performance regressions, and resource saturation through logs, traces, and key performance indicators [

27]. These instruments implicitly assume that relevant causes of degradation manifest as temporally bounded events or anomalies attributable to identifiable system components. Such assumptions align with failure modes dominated by hardware faults, software defects, or isolated overload conditions.

Control coherence violations do not conform to this model. The interactions that give rise to incoherence are distributed across layers and time scales, with no single decision or event that can be isolated as the cause. As a result, the signals emitted by standard observability pipelines remain internally consistent while the system as a whole degrades. The measurement gap therefore arises not from insufficient instrumentation but from a mismatch between what is measured locally and the structural properties that govern global system behavior.

3.2. The Invisibility of Coherence Loss

Loss of control coherence generates economic and operational cost without producing explicit error states or fault conditions [

25]. Systems may continue to meet availability targets and component-level service objectives while exhibiting rising cost per output, increased variance in latency, or diminished reproducibility. These effects are emergent rather than component-specific, arising from the collective behavior of interacting control mechanisms [

19,

20].

Because coherence loss does not correspond to discrete failures, it remains largely invisible to monitoring approaches that rely on threshold violations or anomaly detection at the component level. The absence of clear fault indicators complicates attribution and remediation, allowing incoherent control interactions to persist unaddressed. This structural invisibility explains why extensive observability investments often fail to resolve cost and stability issues rooted in control-layer interactions. Notably, classical consistency and consensus mechanisms from distributed systems theory do not address this problem, as they concern agreement on shared state rather than alignment of control intent across autonomously operating layers.

4. Incoherence as a Structural Phenomenon

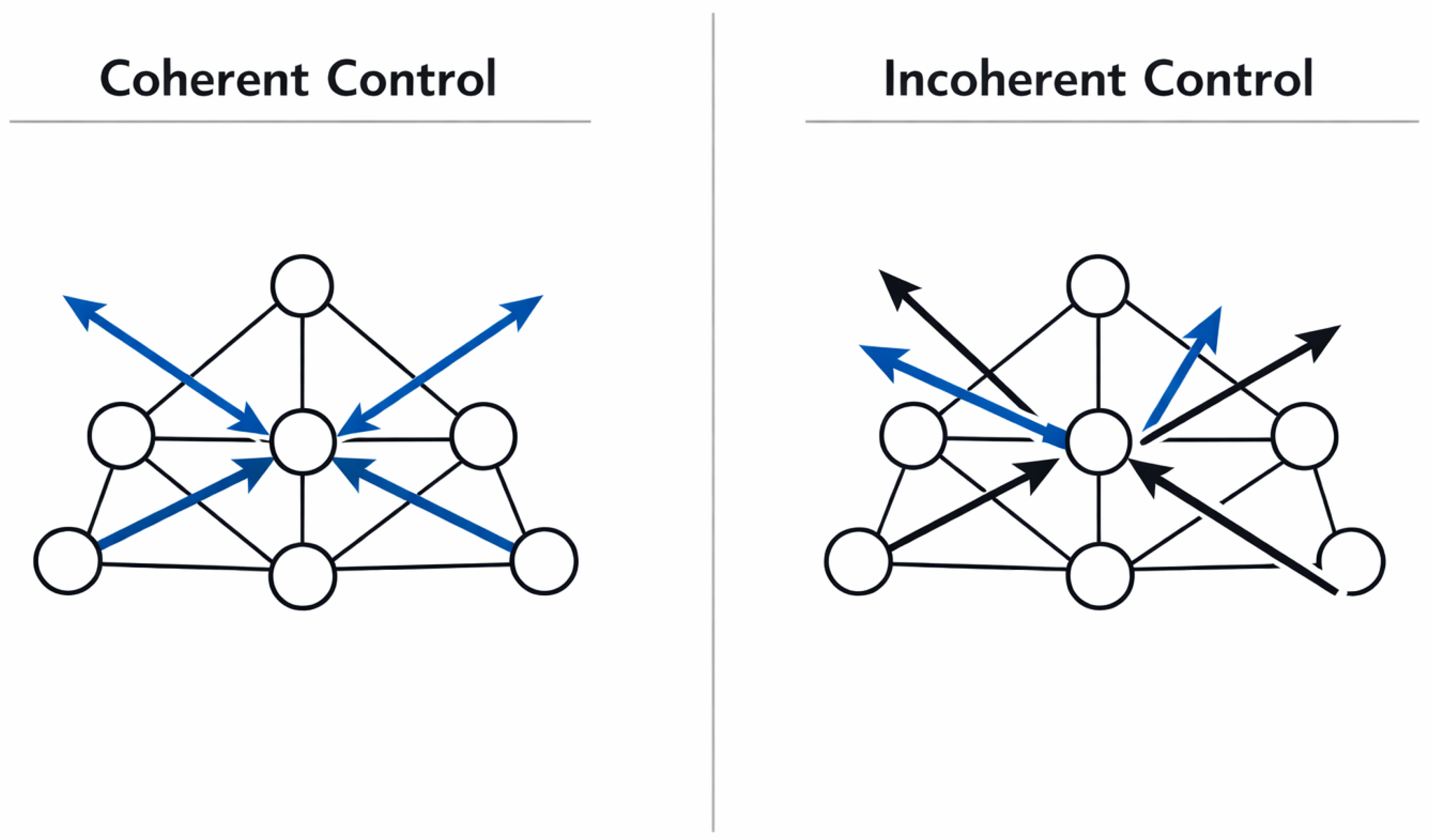

4.1. Coherence Versus Incoherence

Control coherence is defined here as the degree to which distributed control decisions operating on a shared underlying operator graph remain mutually consistent over time. Consistency in this context does not imply identical objectives or synchronized execution, but rather the absence of systematic conflicts that negate or destabilize the effects of individual control actions [

1,

2]. Coherent control behavior allows local decisions to compose into a stable global execution pattern.

Incoherence arises when control actions interact in ways that conflict, counteract, or unintentionally amplify one another. Such interactions are not the result of faulty control logic but of structural misalignment between independently designed control layers. In this sense, incoherence constitutes a system-level property that emerges from the composition of control mechanisms rather than from errors within any single component.

Figure 2.

Conceptual contrast between coherent and incoherent control decisions acting on the same operator graph.

Figure 2.

Conceptual contrast between coherent and incoherent control decisions acting on the same operator graph.

4.2. Soft Degradation Versus Hard Failure

Hard failures are characterized by explicit error conditions, component crashes, or violations of safety constraints that trigger immediate remediation [

25]. These failures are typically discrete, detectable, and attributable to identifiable causes. In contrast, control incoherence gives rise to soft degradation modes that evolve gradually and do not manifest as explicit faults.

Such degradation includes slow convergence loss in iterative workloads, retry amplification that increases effective workload without increasing output, tail latency inflation under otherwise healthy load conditions [

7], and progressive service-level objective drift. These phenomena degrade efficiency and predictability while remaining below conventional failure thresholds, making them difficult to detect and address through standard fault-handling mechanisms.

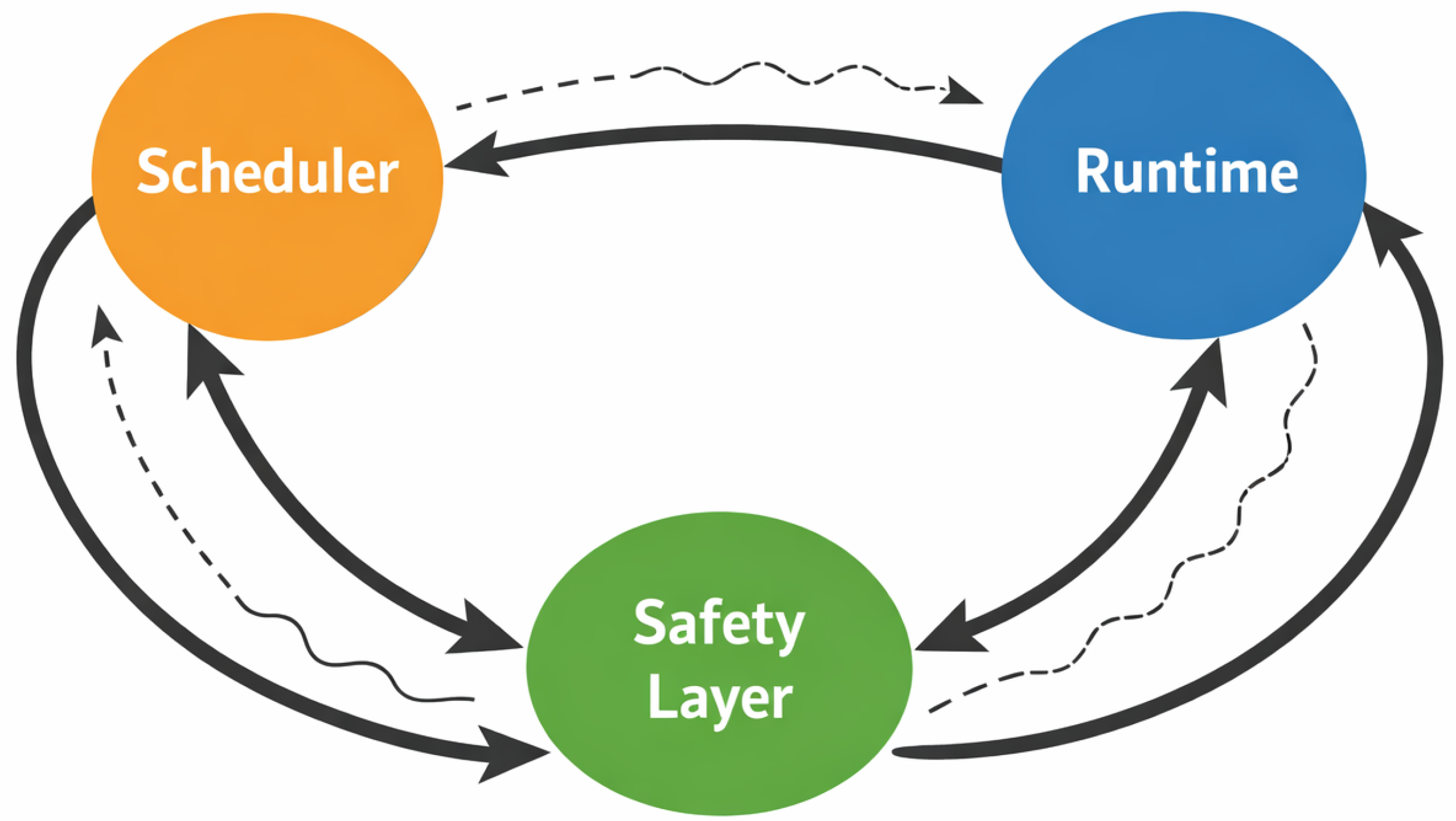

4.3. Non-Local Coupling and Emergent Effects

Incoherence is reinforced by non-local coupling effects, whereby control actions at one layer propagate through the system and interact with responses at other layers [

21,

24]. Because control loops operate on different abstractions and timescales, their interactions can produce feedback patterns that are neither anticipated nor observable from a single control perspective.

Examples include scheduler reactions that amplify runtime-level adjustments, safety timeouts that trigger retry cascades across distributed tasks [

8], and emergent control storms arising from the interaction of nominally independent control loops [

13]. These effects illustrate how incoherence manifests as a structural phenomenon, shaped by the topology and coupling of control mechanisms rather than by localized faults or misconfigurations.

Figure 3.

Non-local coupling and feedback amplification across control layers leading to soft degradation.

Figure 3.

Non-local coupling and feedback amplification across control layers leading to soft degradation.

5. The Economic Dimension: Where Real Costs Arise

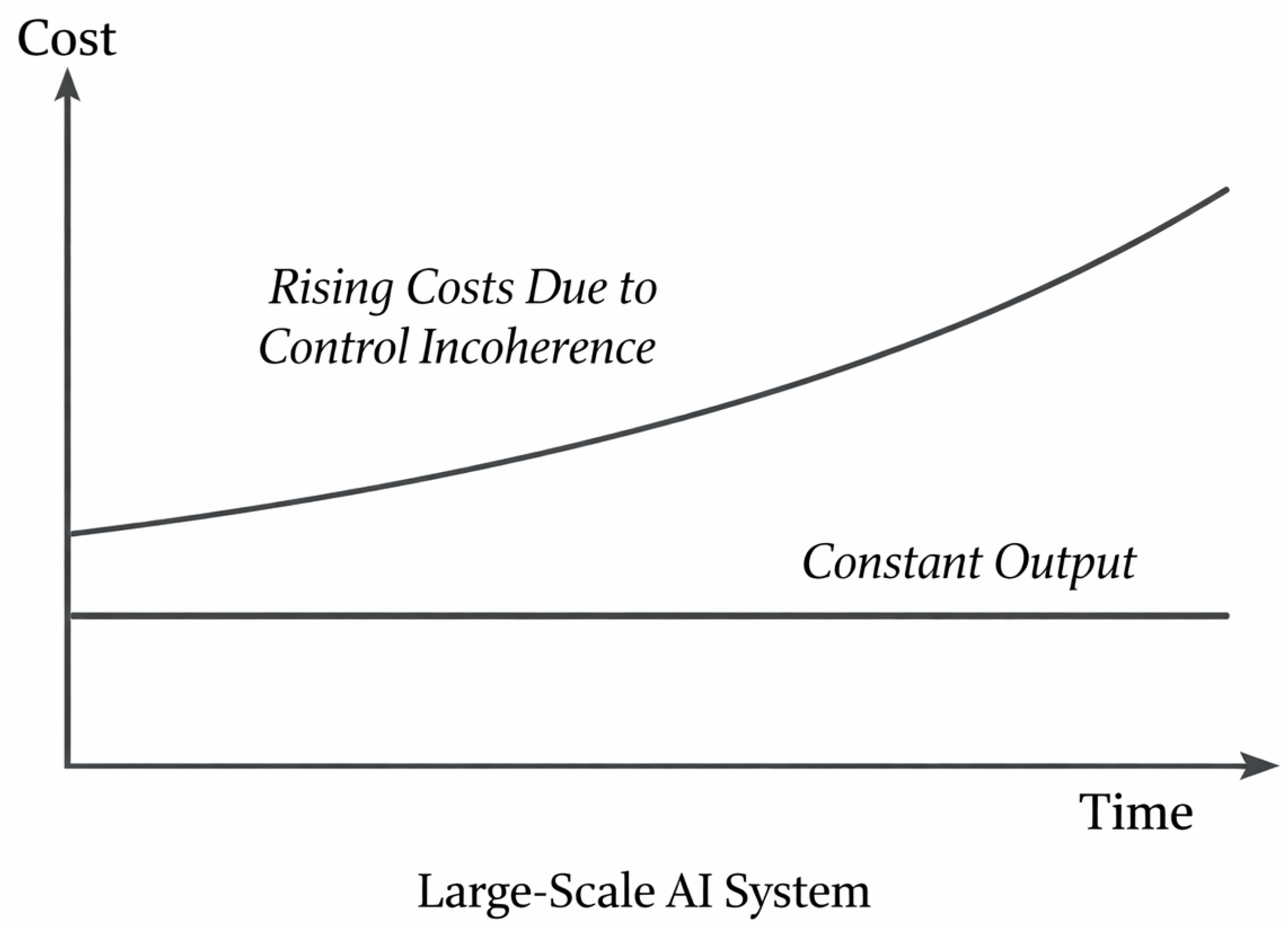

5.1. Direct Cost Effects

Control incoherence produces direct economic costs that are immediately reflected in infrastructure utilization metrics, yet are poorly attributable to specific faults or misconfigurations. A primary effect is accelerator time consumed without proportional progress or output, as conflicting control decisions lead to redundant execution, stalled pipelines, or ineffective parallelism [

28]. In token-based or iterative workloads, such inefficiencies manifest as wasted computational tokens and duplicated work resulting from uncoordinated retry behavior and partial recomputation [

26].

Additional direct costs arise from excess energy consumption and inflated queueing delays [

30]. Control interactions that oscillate between overcommitment and throttling increase idle periods, prolong execution timelines, and amplify tail latency. These effects accumulate at scale, translating control incoherence into measurable increases in operational expenditure even when nominal utilization targets appear to be met.

Figure 4.

Economic impact of control incoherence: cost escalation without proportional output increase.

Figure 4.

Economic impact of control incoherence: cost escalation without proportional output increase.

5.2. Hidden and Systemic Costs

Beyond immediately observable resource consumption, control incoherence generates a class of hidden and systemic costs that are more difficult to quantify but no less consequential [

29]. One such effect is irreproducibility, where repeated executions under ostensibly identical conditions yield divergent performance characteristics or outcomes due to shifting control interactions. This undermines confidence in benchmarking, capacity planning, and empirical evaluation.

Control incoherence also introduces audit and compliance gaps, as system behavior cannot be reliably reconstructed from logs and metrics that capture only local events. Engineering effort is diverted toward diagnosing phantom issues that arise from emergent interactions rather than identifiable defects, creating sustained engineering drag. Finally, distorted performance signals lead to procurement and investment decisions based on unreliable data, reinforcing cycles of overprovisioning or misallocation. Together, these hidden costs position control incoherence as a systemic economic risk rather than a localized operational concern.

6. Why Over-Provisioning Is Not a Solution

A common response to performance degradation and instability in large-scale systems is the addition of hardware capacity in the form of more accelerators, increased memory, or expanded network resources. As argued in prior analyses of interconnect-induced instability, such over-provisioning strategies may temporarily mask symptoms but do not address the underlying structural causes of inefficiency. In the context of control coherence, additional resources fail to resolve conflicts between control layers and may instead exacerbate their effects.

Increasing capacity expands the coordination surface of the system, introducing new degrees of freedom for schedulers, runtimes, and policy mechanisms to act upon [

12]. These expanded decision spaces intensify interactions between control loops and can amplify feedback effects, leading to oscillatory behavior or unstable equilibria [

15,

16]. Rather than dampening incoherence, surplus resources often provide greater scope for conflicting control actions to propagate.

Because control incoherence is structural rather than resource-bound, capacity buffers address observable consequences without eliminating their source [

29]. Over-provisioning therefore risks entrenching inefficient control dynamics while increasing cost, reinforcing the need for analytical approaches that focus on coordination and control interactions rather than on resource abundance alone.

7. Toward a Structural Perspective

7.1. The Need for System-Level Analysis

Control incoherence cannot be adequately understood through isolated event analysis or component-level attribution. This section motivates the necessity of a system-level perspective in which control decisions are treated as structural relations embedded within a shared operational context. Rather than manifesting as discrete faults, coherence loss emerges from patterns of interaction among multiple decision-making entities whose effects accumulate over time [

22,

23].

From this perspective, local optimization efforts are insufficient, as they fail to account for the global dependencies and feedback structures that shape system behavior. Addressing coherence therefore requires analytical frameworks capable of representing how control actions relate to one another across layers, timescales, and abstraction boundaries.

7.2. Operator-Based Approaches

Operator-based approaches provide a conceptual framework for reasoning about control coherence at the appropriate structural level [

1,

2]. By representing infrastructure-level coupling among compute operations, communication events, and coordination dependencies, the operator graph offers a common reference model onto which diverse control actions can be projected.

Within this framework, state projections from different control layers can be examined for consistency, conflict zones between decision domains can be identified, and feedback loops responsible for emergent incoherence can be traced. The operator graph, as used here, is explicitly distinct from framework-level computation graphs and instead captures the operational structure that underlies runtime behavior across the system.

7.2.1. Auditability and Traceability of Operator Graphs

Beyond diagnostic value, operator-graph representations have direct implications for auditability and governance [

3]. This subsection establishes their relevance for architecture review boards, risk management functions, and compliance requirements in large-scale AI deployments.

By enabling reconstruction of how interacting control decisions produced specific operational outcomes, operator graphs support traceability and accountability in environments where responsibility is otherwise diffuse. Such structural traceability forms a prerequisite for meaningful oversight of complex AI systems, particularly where economic impact, reliability guarantees, or regulatory obligations are at stake. The capacity to identify, reconstruct, and attribute the interactions of autonomous control loops constitutes a foundational requirement for governance, risk assessment, and organizational accountability in infrastructures where no single layer exercises global authority.

8. Discussion

8.1. Implications for Architecture and Procurement Decisions

The perspective developed in this work has direct implications for how architectural and procurement decisions are framed and evaluated. Control coherence introduces a class of structural risk that is not captured by traditional performance benchmarks or capacity planning exercises. Architectural choices that appear neutral or even beneficial when evaluated in isolation may introduce hidden coordination dependencies once deployed within multi-layered control environments.

From a procurement standpoint, this implies that decisions based solely on peak performance metrics, unit cost, or isolated efficiency gains are insufficient. Teams must instead ask how newly introduced components interact with existing control loops, which coordination surfaces they expand, and whether they amplify or mitigate feedback effects across layers. Governance processes can intervene by requiring coherence-oriented reviews that explicitly assess cross-layer interactions before large-scale adoption or capacity expansion.

8.2. Open Research Questions

The analysis presented here raises several open research questions that warrant further investigation. A central challenge concerns the measurability of control coherence as a system-level property. Unlike latency or throughput, coherence does not admit a straightforward scalar metric and may require relational or structural representations to be meaningfully assessed [

27].

Additional questions include identifying the minimal instrumentation required to detect coherence loss, determining how coherence can be evaluated when access to internal operational data is restricted, and understanding how coherence dynamics differ across system classes such as training, inference, and agentic orchestration. Addressing these questions is essential for translating structural insights into empirically grounded diagnostics.

8.3. Outlook on Empirical Validation

While this article deliberately avoids implementation guidance, it is nonetheless important to outline plausible pathways for empirical validation. Such pathways should emphasize reproducibility and structural attribution rather than optimization or intervention. Diagnostic studies may, for example, compare system behavior under controlled variations of control-layer interaction patterns, or analyze historical operational data for signatures of non-local feedback and coordination failure.

Crucially, empirical validation in this context does not require intrusive instrumentation or access to proprietary internals. Instead, it relies on carefully designed observational frameworks that align with the structural perspective developed in this series. This positioning preserves the analytical focus of the work while enabling independent verification and comparative analysis across deployments.

9. Conclusions

This article has argued that a growing class of cost and stability problems in large-scale AI systems cannot be explained by performance limitations or interconnect constraints alone. Even in infrastructures where compute capacity and network resources are adequate, economically significant inefficiencies persist due to loss of coherence between distributed control layers. Schedulers, orchestrators, runtime engines, model-level mechanisms, and policy controls may each operate correctly in isolation, yet collectively give rise to non-determinism, soft degradation, and escalating costs when their decisions are not mutually consistent.

By framing runtime control coherence as a structural system property, this work extends prior analyses of interconnect-induced instability into the control domain. The resulting perspective shifts attention away from localized faults and component-level optimization toward coordination, feedback, and interaction effects across control planes. In doing so, it provides a conceptual foundation for understanding why traditional metrics and remedial strategies often fail, and why additional capacity alone does not resolve observed inefficiencies. This structural viewpoint establishes control coherence as a first-order consideration for the analysis, governance, and economic assessment of contemporary AI infrastructures.

Data Availability Statement

The complete SORT v6 framework, including operator definitions, validation protocols, and reproducibility manifests, is archived on Zenodo under DOI

10.5281/zenodo.18094128. The MOCK v4 validation environment is archived at

10.5281/zenodo.18050207. Source code and supplementary materials are maintained at

GitHub. Domain-specific preprints are available via the MDPI Preprints server.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the foundational architectural work developed in earlier SORT framework versions, which enabled the completion of the present architecture.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

The author confirms that no artificial intelligence tools were used in the generation of scientific content, theoretical concepts, mathematical formulations, or results. Automated tools were used exclusively for editorial language refinement and formatting assistance.

References

- Wegener, G. H. SORT-AI: A Projection-Based Structural Framework for AI Safety—Alignment Stability, Drift Detection, and Scalable Oversight. 2025, 2024121334

. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, G. H. SORT-CX: A Projection-Based Structural Framework for Complex Systems—Operator Geometry, Non-Local Kernels, Drift Diagnostics, and Emergent Stability. Preprints 2025, 2024121431

. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, G. H. SORT-AI: A Structural Safety and Reliability Framework for Advanced AI Systems with Retrieval-Augmented Generation as a Diagnostic Testbed. Preprints 2025, 2024121345

. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, G. H. SORT-AI: Interconnect Stability and Cost per Performance in Large-Scale AI Infrastructure—A Structural Analysis of Runtime Instability in Distributed Systems. Preprint 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; et al. Large-Scale Cluster Management at Google with Borg. Proceedings of EuroSys’15 2015, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzkopf, M.; et al. Omega: Flexible, Scalable Schedulers for Large Compute Clusters. Proceedings of EuroSys’ 13 2013, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Barroso, L. A. The Tail at Scale. Communications of the ACM 2013, 56(2), 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthanarayanan, G.; et al. Effective Straggler Mitigation: Attack of the Clones. Proceedings of NSDI’13, 2013; pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, D.; et al. Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM. Proceedings of SC21, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbhandari, S.; et al. ZeRO: Memory Optimizations Toward Training Trillion Parameter Models. Proceedings of SC20, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; et al. GPipe: Efficient Training of Giant Neural Networks using Pipeline Parallelism. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefler, T.; et al. Scalable Communication Protocols for Dynamic Sparse Data Exchange. Proceedings of PPoPP’10 2010, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellerstein, J. L.; Diao, Y.; Parekh, S.; Tilbury, D. M. Feedback Control of Computing Systems; John Wiley & Sons, 2004; ISBN 978-0-471-26637-2. [Google Scholar]

- Åström, K. J.; Murray, R. M. Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers; Princeton University Press, 2008; ISBN 978-0-691-13576-2. [Google Scholar]

- Patarasuk, P.; Yuan, X. Bandwidth Optimal All-Reduce Algorithms for Clusters of Workstations. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2009, 69(2), 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; et al. Collective Communication: Theory, Practice, and Experience. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2007, 19(13), 1749–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. B.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Jouppi, N. P.; et al. In-Datacenter Performance Analysis of a Tensor Processing Unit. Proceedings of ISCA’17 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yam, Y. Dynamics of Complex Systems; Addison-Wesley, 1997; ISBN 978-0-201-55748-1. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M. Networks: An Introduction; Oxford University Press, 2010; ISBN 978-0-19-920665-0. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, R.; Barabási, A.-L. Statistical Mechanics of Complex Networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 47–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; et al. Early-Warning Signals for Critical Transitions. Nature 2009, 461, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M. Complexity: A Guided Tour; Oxford University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-0-19-512441-5. [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz, S. H. Exploring Complex Networks. Nature 2001, 410, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avizienis, A.; et al. Basic Concepts and Taxonomy of Dependable and Secure Computing. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2004, 1(1), 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, J.; et al. CheckFreq: Frequent, Fine-Grained DNN Checkpointing. Proceedings of FAST’21, 2021; pp. 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R. The Art of Computer Systems Performance Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, 1991; ISBN 978-0-471-50336-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, L. A.; Hölzle, U. The Case for Energy-Proportional Computing. IEEE Computer 2007, 40(12), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, L. A.; Clidaras, J.; Hölzle, U. The Datacenter as a Computer: An Introduction to the Design of Warehouse-Scale Machines. In Synthesis Lectures on Computer Architecture, 2nd ed.; 2013; Volume 8, 3, pp. 1–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M. K. The Effect of Data Center Temperature on Energy Efficiency. Proceedings of ITHERM’08 2008, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).