1. Introduction

Current “agentic AI” frameworks like LangGraph, AutoGen, and OpenAI’s multi-agent examples promise autonomous agents capable of planning, reasoning, and coordinating. However, these systems achieve coordination through sequential prompt chaining and centralized LLM orchestration—approaches that fundamentally limit scalability and autonomy. They lack persistent memory, goal continuity, and principled inter-agent communication, instead relying on brittle prompt engineering and implicit state management.

The core limitation is architectural: these frameworks conflate semantic understanding with process orchestration. Every coordination decision requires LLM inference, creating bottlenecks where formal methods would be more appropriate. This “LLM-mediated coordination” approach forces expensive language model calls for routine process management tasks, limiting both performance and predictability.

Recent industry efforts recognize these limitations. Google’s Agent-to-Agent (A2A) Protocol

https://developers.googleblog.com/en/a2a-a-new-era-of-agent-interoperability/ (accessed on June 27, 2025). enables structured interaction between AI agents through standardized communication layers, while the Model Context Protocol (MCP)

https://modelcontextprotocol.io/introduction (accessed on July 1, 2025). addresses vertical integration with tools and resources. However, Li and Xie [

1] demonstrate that combining these protocols introduces critical challenges, including semantic mismatches, security risks, and orchestration complexity that exceed current capabilities.

We present TB-CSPN, a formal architecture that addresses these limitations through architectural separation: semantic processing occurs through strategic LLM usage while coordination employs rule-based business logic. This separation enables TB-CSPN to achieve 62.5% faster processing and 66.7% fewer LLM calls than LangGraph-style orchestration while maintaining semantic fidelity.

TB-CSPN’s key innovation is a dedicated multi-agent coordination substrate built on Colored Petri Net semantics. Instead of LLM-mediated process management, agents communicate through structured topic-annotated tokens that enable formal verification of coordination properties. The framework supports three distinct agent roles: LLM-powered consultants for semantic understanding, human supervisors for strategic oversight, and specialized AI workers for operational execution.

Our empirical evaluation demonstrates that efficient agentic AI emerges not from avoiding modern AI components, but from using them strategically within architectures designed for multi-agent coordination. TB-CSPN shows how formal methods can complement rather than compete with LLM capabilities, providing a foundation for scalable, verifiable, and human-controllable agent systems.

Paper Organization.Section 2 reviews traditional multi-agent systems and recent LLM-native frameworks.

Section 3 establishes minimal criteria for agency and explains why current LLM pipelines fail to meet them.

Section 4 presents the TB-CSPN architecture and its formal foundations.

Section 5 details our implementation including the multi-engine system supporting rule-based coordination, Petri net semantics, and LLM integration.

Section 6 provides a comprehensive case study with quantitative evaluation showing TB-CSPN’s advantages over LangGraph-style coordination.

Section 7 presents systematic comparisons with leading frameworks.

Section 8 concludes with implications for next-generation agentic AI architectures.

2. Related Work

The concept of intelligent software agents [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] and their associated programming paradigms have evolved through two distinct eras: traditional multi-agent systems and modern LLM-native frameworks [

7]. While traditional approaches provided formal foundations for coordination, current LLM-native frameworks achieve popularity at the cost of architectural rigor, creating fundamental limitations that our TB-CSPN approach directly addresses.

2.1. Traditional Multi-Agent Systems: Formal Foundations

Classical multi-agent systems [

8] established principled approaches to agent coordination through architectures like Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI) [

9] and Contract Net Protocol (CNP) [

10]. The BDI architecture models agents using beliefs (informational state), desires (motivational goals), and intentions (deliberative commitments), supporting both reactive and proactive behavior with interpretable rational decision-making. CNP provides decentralized coordination in which agents act as managers or contractors, establishing formal foundations for negotiation and resource allocation.

These traditional approaches emphasized “architectural separation of concerns”: cognitive processes, coordination mechanisms, and communication protocols operated through distinct, formally specified interfaces. Early work on constraint-based distributed problem solving [

11] demonstrated how formal protocols could coordinate autonomous agents through structured information exchange while maintaining modular design principles. However, these approaches predated modern machine learning capabilities and struggled with dynamic environments requiring adaptive learning.

2.2. LLM-Native Frameworks: Popular but Architecturally Flawed

The emergence of Large Language Models has spawned a new generation of frameworks that position themselves as “agentic AI” solutions, succh as LangGraph [

12], AutoGen [

13], and Agentic RAG [

14], with OpenAI already providing a number of multi-agent examples [

15]. While these frameworks demonstrate impressive capabilities, they exhibit relevant architectural flaws that limit their scalability and true autonomy.

2.2.1. LangGraph: Workflow Orchestration Masquerading as Agency

LangGraph, built on LangChain, represents the current state-of-the-art in LLM-powered agent frameworks. It introduces persistent memory, state transitions, and modular task nodes, executing workflows as finite-state machines or graphs. However, LangGraph exhibits three critical limitations that TB-CSPN directly addresses:

Conflation of Semantic and Coordination Logic: LangGraph requires LLM involvement at every coordination decision, forcing expensive language model inference for routine process management tasks that could be handled deterministically.

Lack of Formal Verification: Unlike traditional agent architectures with mathematical foundations, LangGraph workflows cannot be formally verified for correctness, leading to unpredictable behavior in complex scenarios.

Centralized Orchestration Bottlenecks: All coordination flows through centralized LLM-mediated decision points, creating scalability limitations as agent populations grow.

2.2.2. AutoGen: Multi-Agent Conversations Without True Coordination

AutoGen facilitates multi-agent applications through conversational interactions between LLM-powered agents. While it supports customizable agent behaviors and conversation patterns, it fundamentally relies on “prompt-based coordination” rather than principled multi-agent protocols. This approach leads to:

Brittle communication patterns, dependent on prompt engineering rather than formal protocols

Lack of persistent agent state beyond conversation history

No mechanisms for goal revision or long-term planning beyond what emerges from conversational dynamics

2.2.3. Agentic RAG: Reactive Information Retrieval, Not Proactive Agency

Agentic RAG [

14] extends traditional Retrieval-Augmented Generation by incorporating reasoning and planning agents into the retrieval pipeline. While this enables more dynamical information gathering, it remains fundamentally “reactive” rather than “proactive”, lacking the autonomous goal-setting and persistent intentionality characteristics of true agents.

2.2.4. OpenAI Multi-Agent Examples: Hard-Coded Scripts, Not Autonomous Agents

OpenAI’s Cookbook [

15] examples demonstrate tool-using systems orchestrated through LLMs, following hard-coded task decomposition and sequential reasoning patterns. These systems lack the fundamental characteristics of autonomous agents, such as long-term goals, self-awareness, adaptive learning, and genuine inter-agent coordination. Their simplicity has popularized the term “agent” in contexts which would actually be better described as reactive scripts.

2.3. The Core Problem: Architectural Limitations of Current Approaches

Current LLM-native frameworks share a fundamental architectural flaw: they conflate semantic understanding with process orchestration. This conflation creates several critical limitations:

Scalability Bottlenecks: Every coordination decision requires expensive LLM inference, creating computational and latency bottlenecks as system complexity grows.

Lack of Formal Properties: Without mathematical foundations, these systems cannot guarantee coordination properties like deadlock freedom, liveness, or bounded response times.

Brittle Prompt Dependencies: Coordination logic embedded in prompts creates fragile systems sensitive to language model variations and prompt engineering artifacts.

Limited Human Integration: Current frameworks treat humans as external users rather than integrated participants in hybrid human-AI workflows.

2.4. Emerging Recognition of Architectural Deficits

Recent literature increasingly recognizes these limitations. Sapkota

et al. [

16] distinguish between AI agents (modular, tool-using systems) and agentic AI (coordinated, multi-agent architectures), highlighting the gap between current implementations and true agency. Su

et al. [

17] propose the R2A2 architecture based on Constrained Markov Decision Processes, emphasizing the need for “strict regulation of cognitive structure and memory persistence”—principles that complement our TB-CSPN approach.

Acharya

et al. [

18] emphasize agentic AI’s “goal-oriented autonomy and adaptability”, while Xi et al. [

19] present a unified brain-perception-action framework highlighting the need for “systematic architectural approaches” rather than ad-hoc prompt chaining.

2.5. TB-CSPN: Addressing Architectural Deficits Through Formal Foundations

Our TB-CSPN framework directly addresses these architectural limitations by:

Separating Semantic and Coordination Logic: LLMs handle semantic processing (topic extraction) while Petri Net semantics manage coordination deterministically.

Enabling Formal Verification: Built on Colored Petri Net foundations, TB-CSPN enables mathematical verification of coordination properties.

Supporting Distributed Coordination: Topic-based communication eliminates centralized orchestration bottlenecks while maintaining semantic coherence.

Integrating Human Agents: Explicit support for human participants as first-class agents in hybrid workflows.

This positions TB-CSPN not as another framework variation, but as a fundamental architecture advance that reclaims the formal foundations of traditional multi-agent systems while leveraging modern AI capabilities strategically rather than ubiquitously.

3. What Is (and Isn’t) an Agent

The term

agent carries substantial philosophical weight [

20,

21], originating in theories of human action, ethics, and responsibility where “agency” distinguished intentional, meaningful behavior from mere reaction or motion. In artificial intelligence, this concept has been central since early work on autonomous systems [

2,

22], yet today it has been diluted to describe nearly any callable function wrapped in a prompt template.

This linguistic inflation reflects deeper conceptual confusion about what constitutes genuine agency in artificial systems. As we demonstrated in

Section 2, current LLM-native frameworks like LangGraph and AutoGen apply the term “agent” to components that lack the fundamental characteristics of autonomous entities. This terminological drift obscures both the limitations of current approaches and the requirements for engineering true multi-agent intelligence.

Our purpose here is not to adjudicate millennia of philosophical debate about intention, belief, or desire, but to establish clear criteria for agency that can guide the design of genuinely autonomous systems. We acknowledge deep disagreements across philosophical traditions—between eliminative materialists like Churchland [

23] who reject propositional attitudes entirely, representationalists who reify mental states, and pragmatists like Dennett [

24,

25] who adopt the

intentional stance as a useful heuristic for prediction and explanation.

Rather than resolve these metaphysical disputes, we propose grounding agency in a minimal set of

observable capacities that remain agnostic to claims about internal mental states. This approach aligns with the broader AI tradition of focusing on functional rather than phenomenological criteria [

22], while avoiding the category errors that plague current “agentic” systems.

3.1. Minimal Criteria for Agency

To rescue the notion of agent from conceptual drift, we define agents as

persistent,

autonomous,

context-sensitive entities that contribute to structured interaction systems. The properties exhibited by agents are shown in

Table 1.

Importantly, this definition eliminates dependence on intentionality in the classical sense. Following Quine’s insight about the indeterminacy of translation [

26], we make no assumptions about beliefs, desires, or internal representations—only that the agent exhibits observable coherence over time and context. This approach is compatible with reactive architectures [

27,

28], distributed coordination systems, and human-AI hybrids while avoiding the “frame problem” that has historically plagued representational approaches to AI.

This functional approach directly addresses the architectural limitations identified in

Section 2: where LangGraph conflates semantic understanding with process orchestration, our criteria separate these concerns; where AutoGen lacks persistent state, our definition requires temporal continuity; where current frameworks provide only scripted interactions, we demand genuine adaptivity.

3.2. The Problem with Current “Agents” in LLM Pipelines

Current LLM orchestration frameworks demonstrate precisely the category error we seek to avoid. In systems like LangChain, AutoGen, and OpenAI’s multi-agent examples, the term “agent” is applied to components that:

exist only for a single prompt-execution cycle, violating the persistence criterion;

lack memory or state continuity, preventing genuine adaptivity;

operate via fixed execution logic or prompt chains, compromising autonomy;

are hard-coded to route input to tools without adaptive negotiation, failing the interaction requirement.

Such entities are better understood as

orchestrated functions rather than agents in any substantive sense. This misapplication of terminology contributes to the architectural confusion documented in

Section 2, where the absence of genuine agency masks fundamental scalability and coordination limitations.

The philosophical roots of this confusion trace to what Dennett [

25] calls the “homunculus fallacy”—the tendency to project human-like intentional states onto systems that merely simulate intentional behavior. Current LLM frameworks achieve impressive performance through sophisticated pattern matching and statistical inference, but lack the architectural foundations necessary for genuine agency.

3.3. Modular and Centaurian Agency: Two Legitimate Architectures

Having established minimal criteria for agency, we can distinguish two viable architectural approaches for implementing genuine agents in artificial systems:

Modular Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) consist of structurally independent agents— whether human or artificial—that coordinate through well-defined protocols rather than centralized orchestration. Each agent maintains persistent state, autonomous decision-making capabilities, and specialized roles such as Supervisor, Consultant, or Worker. The TB-CSPN architecture presented in subsequent sections exemplifies this approach, using topic-based coordination to enable distributed intelligence without sacrificing formal verifiability.

Centaurian Systems [

29,

30] implement hybrid agents that integrate human strategic cognition with machine-level automation through layered architectures reflecting cognitive division of labor. Humans provide high-level problem framing and oversight while machines handle execution, with shared state representations enabling seamless coordination. This approach acknowledges that the most capable “agents” may be human-machine collaboratives rather than purely artificial entities.

Both architectures satisfy our minimal definition of agency while avoiding the representational commitments that generate philosophical controversy. They demonstrate how agentic behavior can be engineered and analyzed without reifying beliefs or desires, focusing instead on observable patterns of autonomous, persistent, and adaptive interaction.

This foundation prepares us to examine how TB-CSPN implements these principles through a formal architecture that separates semantic processing from coordination logic, enabling the construction of genuinely agentic systems that transcend the limitations of current LLM-native approaches.

4. TB-CSPN: Architecture Overview

In [

31], Borghoff

et al. introduce TB-CSPN as a formal framework for coordinating MAS composed of human supervisors, LLM-based consultants, and specialized AI workers. TB-CSPN differs from traditional MAS and current LLM-agent frameworks in that it combines colored Petri nets, topic modeling, and threshold-based group formation to deliver a semantically grounded, dynamically adaptive architecture.

The framework’s core innovation lies in topic-tagged tokens that traverse three communication layers—Surface, Observation, and Computation—corresponding to strategic, semantic, and operational responsibilities, respectively. Supervisor agents initiate high-level directives, consultant agents (typically LLMs) transform and refine semantic content, and worker agents execute deterministic tasks. Agent activation and group formation are governed by topic relevance thresholds, enabling emergent, context-sensitive collaboration.

4.1. Conceptual Foundation and Formal Models

The TB-CSPN architecture is built upon a formal organizational model that distinguishes abstract specifications from their concrete realizations.

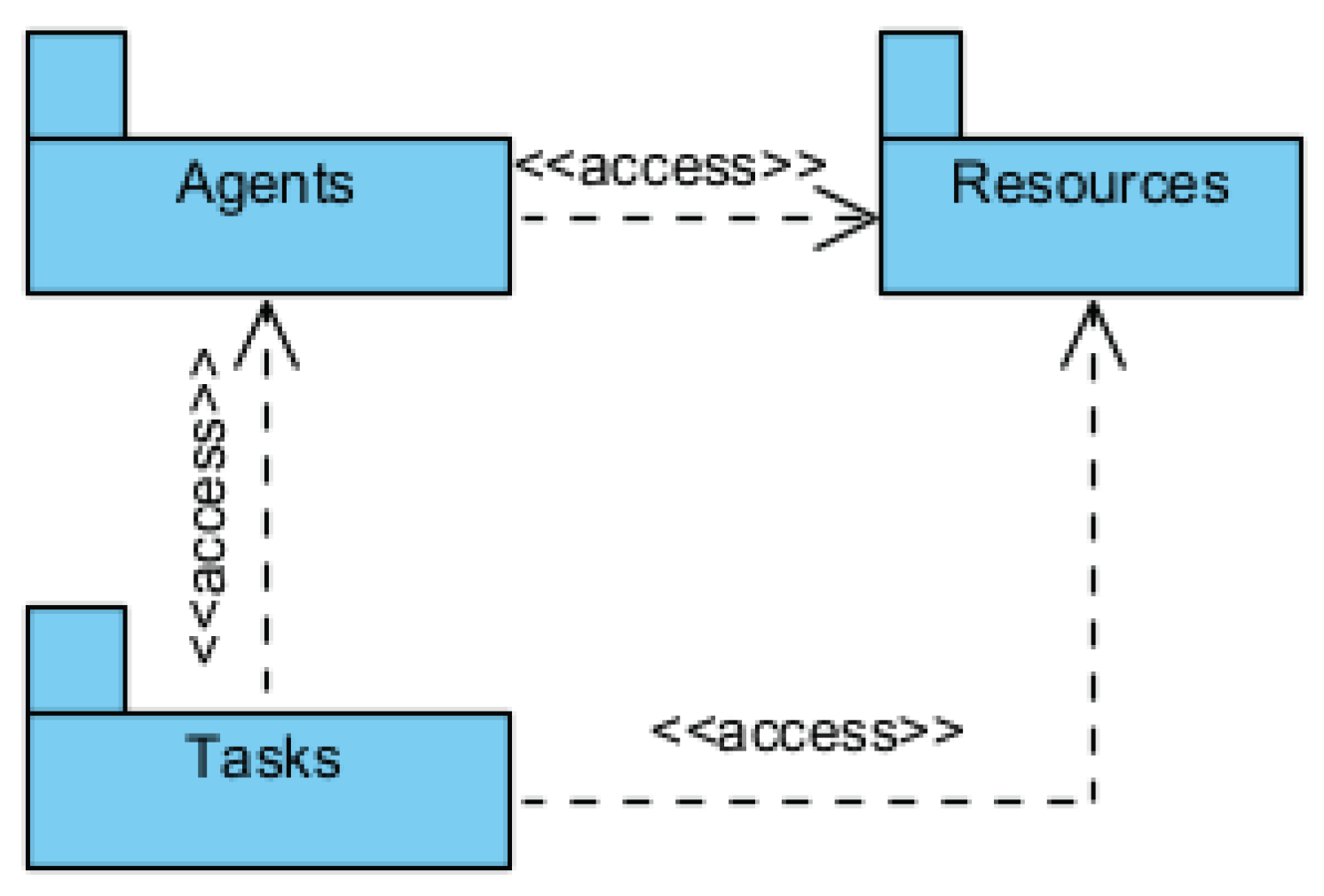

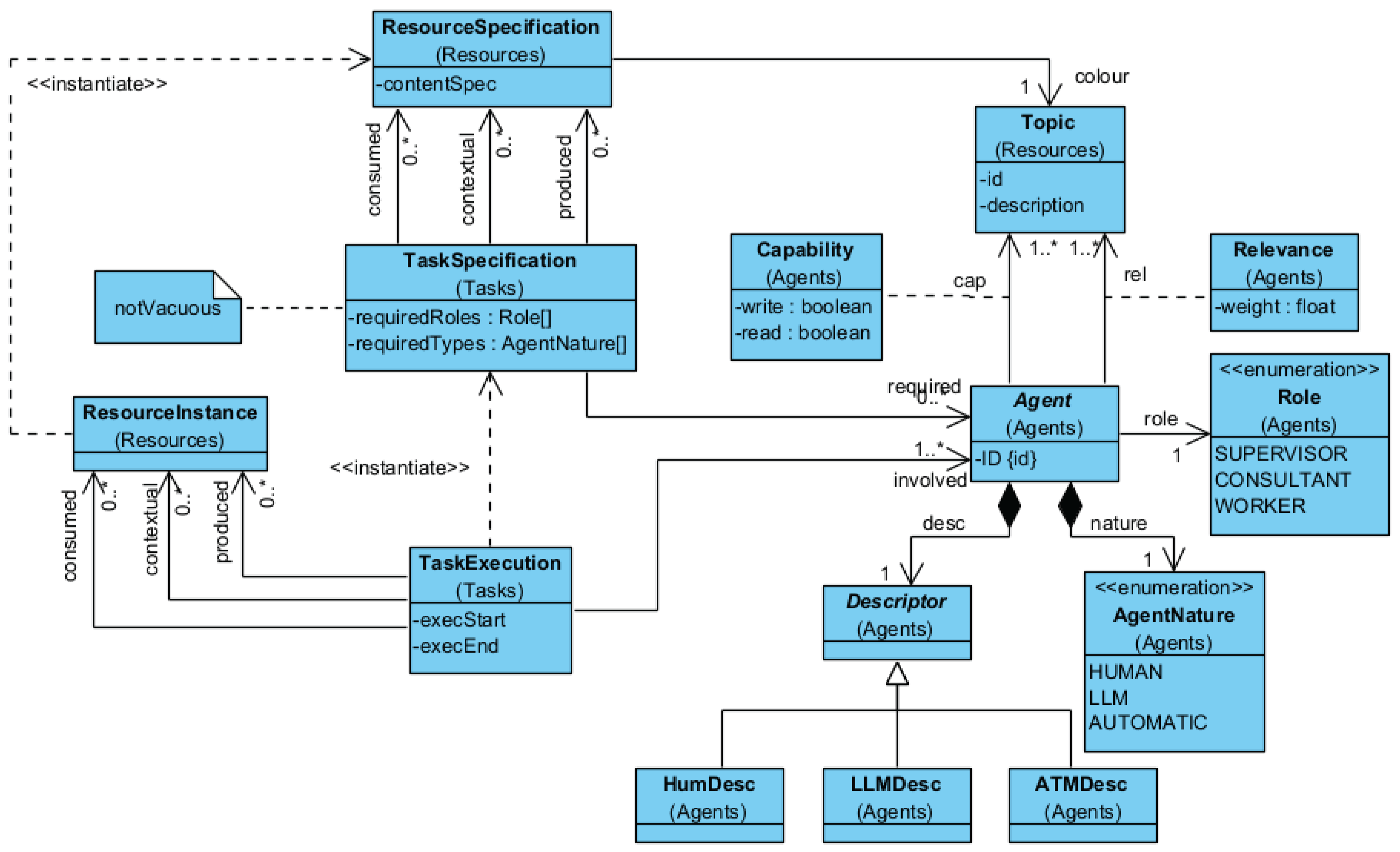

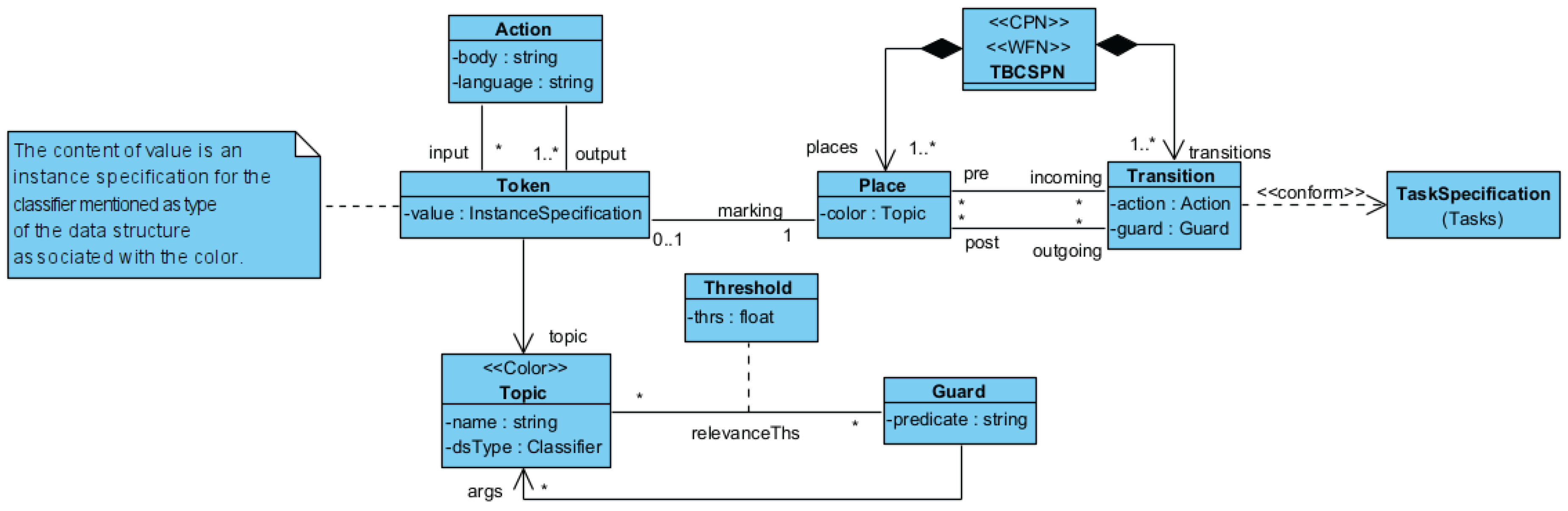

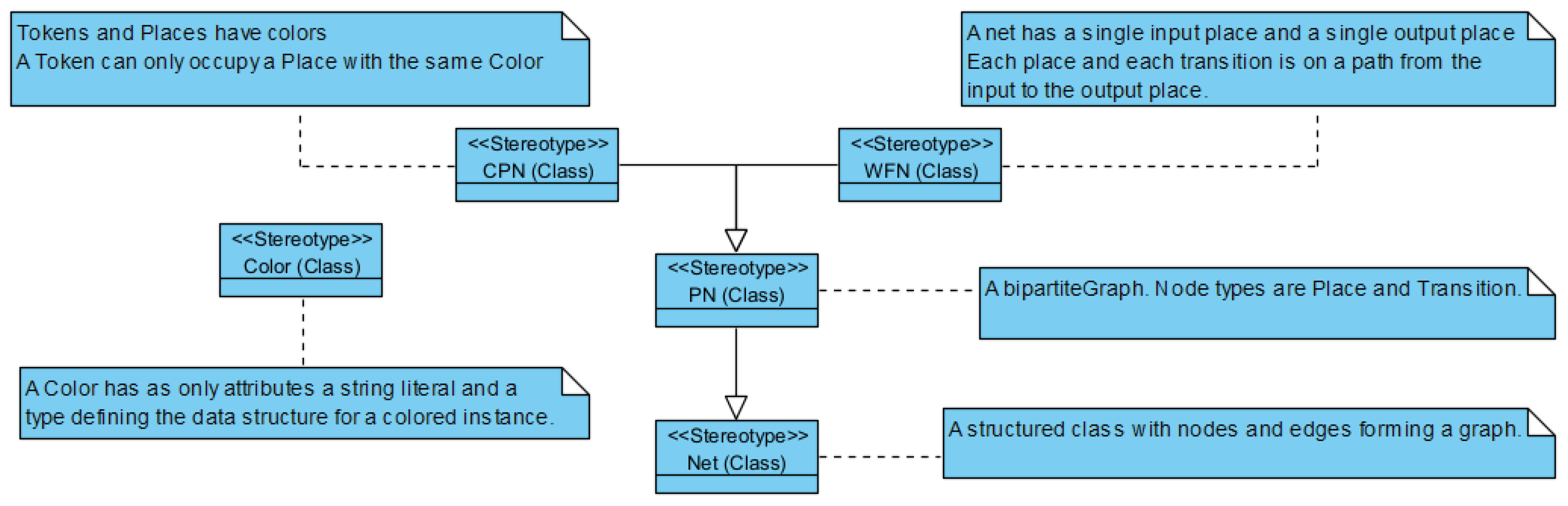

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present the conceptual architecture through a series of UML models, showing how organizational concepts map to Petri net implementations.

Figure 1 presents the three packages that compose the organizational view. In the

Task package, we collect the classes representing the tasks the execution of which the organization must be capable of. The

Agent package collects the classes modeling the various types of agent, while the

Resources package provides the classes for the representation of

Topics instantiated by

Resources.

Figure 2 presents a global view of the resulting organizational architecture, where for each class the package in which it is fully defined is indicated. An organization is conceptualized as a collection of

Tasks performed by

Agents producing and consuming

Resources. While

TaskSpecification and

ResourceSpecification allow reasoning in abstract on requirements, their

Execution counterparts record the effective unfolding of activities in the organization.

4.2. Petri Net Realization

For the realization of the organizational model via TB-CSPN, we employ Colored Petri Nets as the formal coordination substrate. This approach enables mathematical verification of coordination properties while supporting the complex token-based communication required for topic-driven agent interaction.

Figure 3 defines our modeling of Petri Nets, based on the

PetriNet profile of

Figure 4. Each organizational

TaskSpecification corresponds to some

Transaction in a PetriNet, with

Resources represented by

Tokens associated with a

Color. As we focus on Colored Petri Nets (stereotype

CPN), each

Place can contain only

Tokens of a specific

Color, ensuring type safety and semantic coherence.

The

PetriNet profile (

Figure 4) introduces stereotypes for characterizing different flavors of Petri Nets. Tokens can be associated with

Actions for computational purposes, enabling the integration of semantic processing with formal coordination mechanisms.

4.3. Layered Communication Architecture

In this layered model, topics act as semantic glue that enables coordination between agents with different capabilities and modalities. Surface agents interpret raw or ambiguous inputs, observation agents refine them into structured topic representations, and computation agents act upon these representations. This process renders topic propagation interpretable, traceable, and context-aware, thereby supporting both autonomy (as in multi-agent systems) and tight coupling (as in Centaurian systems).

The whole organization can be represented as the composition of all nets formed with

Transactions realizing

TaskSpecifications. However, we focus on modeling specific processes expressed as sequences of tasks defining flows across the

Surface,

Observation, and

Computation layers. Each process is modeled as a

Workflow Net (stereotype

WFN) [

32], characterized by having one

input and one

output place, with any place and transition in the net lying on a path from the input to the output place.

4.4. Integration with Modern AI Components

A companion study [

33] situates TB-CSPN within a broader theoretical context by contrasting modular multi-agent architectures with Centaurian systems. The latter fuse human and machine capabilities into functionally interdependent hybrids. This duality is operationalized through communication spaces, which serve as architectural zones for adaptive feedback, semantic mediation, and cognitive fusion.

Unlike existing systems such as LangChain, AutoGen, and Agentic RAG, TB-CSPN provides a principled alternative by combining formal semantics, layered decision-making, and dynamic group coordination. The framework formalizes the role of centauric agents—human-AI hybrids that maintain human intent and oversight while leveraging machine intelligence for scale and precision.

The framework supports semantic evolution, traceability, and human-AI collaboration, maintaining interpretability while enabling real-time reconfiguration. This architectural foundation has been validated through applications to emergency response, healthcare research, and financial strategy, as detailed in the subsequent implementation and case study sections.

5. Implementation Walkthrough

The TB-CSPN framework has been implemented as a modular, multi-engine architecture that validates the theoretical principles through practical computational models. This section outlines the key architectural decisions and implementation strategies that realize topic-based coordination, threshold-driven activation, and layered agent communication. The complete implementation, including source code, documentation, and evaluation benchmarks, is publicly available at

https://github.com/Aribertus/tb-cspn-poc.

5.1. Multi-Engine Architecture

The implementation validates TB-CSPN’s theoretical foundations through three complementary engines that demonstrate the equivalence between rule-based and Petri net coordination models:

Rule Engine: Implements declarative rule-based coordination, emphasizing modular rule composition and local reasoning

CPN Engine: Provides formal Colored Petri Net semantics with typed places, guarded transitions, and verifiable execution properties

SNAKES Engine: Leverages established Petri net libraries for classical analysis, visualization, and formal verification

This multi-paradigm approach provides computational abstractions suited to different deployment contexts—from rapid prototyping to formal verification—while maintaining the semantic consistency established by the organizational models presented in

Section 4.

5.2. Core Architectural Principles

5.2.1. Semantic Token Model

The implementation centers on a unified token abstraction that explicitly encapsulates semantic information with weighted topics. Unlike prompt-based coordination systems where inter-agent communication relies on unstructured text passing, TB-CSPN tokens carry their semantic context as structured metadata with topic distributions, enabling formal reasoning about relevance and coordination decisions.

This token model directly implements the

Token and

Color abstractions defined in the organizational model (

Figure 3,

Figure 4), ensuring consistency between theoretical specification and practical implementation.

5.2.2. Topic-Driven Coordination

Topics function as a semantic interlingua that enables coordination between heterogeneous agents without requiring shared internal representations. The implementation supports multiple topic extraction methods—including sophisticated LLM-based semantic analysis for complex financial content—while maintaining a unified token-based substrate for threshold-driven decision making.

5.3. Agent Hierarchy Implementation

The framework implements the three-tier agent architecture through role-specific interfaces and coordination protocols. Our financial news processing system demonstrates these patterns in a production context, following the agent types and capability models established in the formal architecture.

5.3.1. Consultant Agent Architecture

Consultant agents transform unstructured input into semantically annotated tokens through a multi-stage process, as implemented in our financial news processing system available in the repository:

Input Processing: CSV-based news ingestion with company-specific grouping for contextual analysis

LLM-based Topic Extraction: Structured prompting of large language models (GPT-4) to identify financial topics and assign relevance scores based on potential market impact

Topic Aggregation: Optional LLM-driven consolidation of semantically similar topics to reduce dimensionality while preserving semantic richness

Token Generation: Creation of structured tokens containing topic distributions, metadata, and traceability information

The consultant implementation demonstrates TB-CSPN’s ability to leverage modern LLM capabilities while maintaining structured coordination through explicit topic representation rather than implicit prompt chaining.

5.3.2. Supervisor Agent Logic

Supervisor agents implement strategic decision-making through a hybrid architecture that accommodates both rule-based abstractions of human expertise and direct human intervention. The framework supports three operational modes that realize the human-AI collaboration models defined in the architectural specification:

Rule-Based Mode: Declarative rules serve as abstractions of human-approved decision patterns, operating over consultant-generated tokens to pattern-match against topic distributions and generate directives when activation thresholds are exceeded. These rules encode institutional knowledge and established protocols, enabling consistent application of human strategic judgment.

Human-in-the-Loop Mode: Direct human supervision allows strategic decision-makers to review topic-annotated tokens and issue directives manually, particularly for novel situations or high-stakes decisions that require contextual judgment beyond codified rules.

Centaurian Mode: AI-augmented human decision-making where supervisory agents provide machine-generated recommendations, risk assessments, or scenario analyses to support human strategic reasoning, combining human intuition with computational analysis capabilities.

This approach ensures modularity—new coordination logic can be added as rules, human oversight can be selectively applied, and AI assistance can be configured per decision context—while maintaining formal semantics through the underlying Petri net substrate.

5.3.3. Worker Agent Execution

Worker agents execute domain-specific actions based on supervisor directives, with support for both deterministic rule-based actions and adaptive learning mechanisms. The implementation provides configurable action handlers that can interface with external systems, databases, or human operators while maintaining full traceability of execution decisions.

5.4. Formal Coordination Mechanisms

Two constituents of the approach are relevant to formally defining coordination.

5.4.1. Hybrid LLM-Rule Processing

The implementation demonstrates TB-CSPN’s architectural advantage over pure LLM-chaining approaches: while topic extraction leverages LLM semantic understanding, coordination occurs through deterministic rule processing. This hybrid approach reduces LLM API calls by approximately 67% compared to fully prompt-driven architectures while maintaining semantic fidelity and enabling formal verification of coordination logic, as detailed in our empirical evaluation (

Section 6).

5.4.2. Petri Net Semantics

The Colored Petri Net engine enforces formal semantics through typed places and guarded transitions, implementing the formal models defined in

Section 4. Places accept only tokens of compatible semantic types, ensuring coherence. Transitions implement threshold-based firing conditions with relevance aggregation, providing formal guarantees about network behavior, including deadlock freedom and bounded execution.

5.5. Integration and Extensibility

The framework seamlessly incorporates modern AI components while preserving semantic transparency and formal coordination guarantees through a stratified agent architecture that optimally distributes cognitive responsibilities across the three hierarchical tiers.

Consultant Layer Integration. LLM integration occurs exclusively at the consultant layer through structured prompting that produces explicit topic annotations, avoiding the brittleness of end-to-end prompt engineering found in prompt-chained architectures. This layer leverages the semantic understanding capabilities of large language models while constraining their usage to well-defined topic extraction tasks, ensuring both efficiency and interpretability.

Supervisor Layer: Human-Centaurian Coordination. The supervisor layer is designed specifically for human strategic decision-making, optionally augmented through centaurian architectures that combine human judgment with AI-assisted analysis. This design recognizes that strategic coordination requires contextual understanding, ethical reasoning, and accountability that remain fundamentally human capabilities.

Worker Layer: Specialized AI Execution. Worker agents implement narrow AI systems optimized for specific operational tasks—portfolio optimization, risk assessment, data analysis, or external system integration. These agents operate deterministically based on supervisor directives, ensuring predictable and auditable execution.

Learning and Adaptation. Learning-enabled components can be integrated at both consultant and worker layers while maintaining formal coordination guarantees through the supervisor layer’s oversight mechanisms.

5.6. Observability and Verification

The implementation provides comprehensive traceability through token lifecycle logging, decision audit trails, and performance metrics collection. Each processing step—from initial topic extraction through final action execution—is logged with metadata, enabling complete reconstruction of decision rationale. The formal Petri net foundation enables static analysis for verification of properties such as reachability, liveness, and fairness.

The financial news processing implementation, available in the public repository, generates detailed execution reports capturing LLM interactions, topic distributions, rule firings, and token generation, providing both operational insights and compliance documentation for production deployment scenarios. Complete documentation, usage examples, and benchmarking code are provided to enable community validation and extension of the architectural principles.

6. Case Study: Topic-Grounded Consultant Agents vs. LLM Chaining Pipelines

This case study presents a concrete implementation of the TB-CSPN architecture within a financial news scenario and contrasts it with current LLM chaining paradigms such as LangGraph and AutoGen. The objective is to show how agentic coordination can be made robust, interpretable, and modular when grounded in a structured topic-based interlingua, as opposed to prompt-centric, black-box chaining.

6.1. Motivation: Why Not LangGraph?

Recent frameworks for LLM orchestration, such as LangGraph, propose “agentic” systems by chaining calls to language models via graph-based flow control. Each node nominally represents an “agent,” but in practice, these systems lack shared semantics or modular state representations. Instead, they rely on brittle prompt engineering and ad hoc memory passing to simulate agent behavior.

In contrast, the TB-CSPN framework uses a structured communication model where agents interact through tokens embedded in a shared topic space. This shared interlingua allows explicit control, coordination, and reasoning, avoiding the opaque and fragile dynamics of purely prompt-based systems.

6.2. Financial News Processing Implementation

The implemented system instantiates the three-tier TB-CSPN architecture for financial news analysis:

Consultant: receives unstructured textual input and annotates it with weighted topics;

Supervisor: interprets the topics using rule-based logic and emits a directive;

Worker: executes or simulates an action based on the directive.

Each agent is modular and traceable, operating over a well-defined data structure called a

Token. This token encodes a message with semantic topics and scores, enabling downstream agents to reason on explicit features rather than inferred intent. The implementation follows the formal models and organizational patterns established in

Section 4.

6.3. Consultant Agent Design

The Consultant agent was enhanced to leverage an LLM (e.g., GPT-4.1) to extract semantically grounded topics from financial news items. Two modes of operation are supported:

Direct Topic Extraction: the model is prompted to return a set of key topics with confidence scores.

Aggregated Topic Extraction: individual topics are grouped by semantic similarity, and their scores aggregated to produce a more abstract representation.

The agent logs both raw and aggregated topics to CSV, along with the original news text, enabling traceable analysis and evaluation.

6.4. Example Pipeline Execution

News items such as:

“Federal Reserve signals possible rate hike in July.”

“Retail stocks underperform despite holiday sales.”

“Tech sector surges on new AI chip breakthrough.”

are fed to the Consultant, producing topic-weighted tokens such as:

{market_volatility: 0.9, fed_policy: 0.8}

{retail_sector: 0.7, consumer_spending: 0.5}

{AI_sector: 0.9, tech_momentum: 0.6}

The Supervisor applies simple rules (e.g., act if any topic exceeds threshold 0.85), producing directives like:

"Monitor AI sector for strategic repositioning."

The Worker agent logs or simulates the appropriate action.

6.5. Step-by-Step Comparison: TB-CSPN vs. Prompt-Chained Agentic Pipelines

To highlight the architectural advantages of TB-CSPN, we walk through the implementation of a financial news use case in both TB-CSPN and a LangGraph-style pipeline. The example considers the processing of the input:

“Tech sector surges on new AI chip breakthrough.”

Table 2 illustrates how TB-CSPN achieves transparency, modularity, and reuse through explicit token structures and agent roles. In contrast, prompt-chained pipelines tend to entangle reasoning, memory, and control logic within sequences of prompts. This limits their scalability and formal analyzability.

6.6. From Use Case to Evaluation

This case study demonstrates how TB-CSPN supports modular, topic-grounded agents capable of semantically rich interpretation and coordination—attributes that are difficult to replicate in LLM chaining frameworks where inter-agent communication and memory structures are ad hoc. The Consultant module, in particular, shows how LLM capabilities can be integrated without sacrificing transparency or modularity.

The example also highlights the framework’s ability to manage threshold-based delegation, log decisions, and support multiple interacting agents over structured tokens. These properties contrast with prompt-driven pipelines that often obscure the coordination logic.

6.7. Quantitative Performance Evaluation

To validate the architectural advantages of TB-CSPN beyond conceptual analysis, we conducted a systematic empirical comparison with LangGraph-style prompt chaining across multiple dimensions of agentic system performance. This evaluation ensures a fair comparison by incorporating LLM usage in both architectures where appropriate.

6.7.1. Fair Comparison Methodology

We implemented equivalent financial news processing pipelines using both TB-CSPN and LangGraph frameworks, processing a dataset of 30 financial news items covering diverse market scenarios. Critically, both systems utilize LLMs for semantic understanding:

TB-CSPN Pipeline: Single LLM call for topic extraction followed by deterministic rule-based coordination

LangGraph Pipeline: Multiple LLM calls throughout the workflow (consultant → supervisor → worker nodes)

This design isolates architectural differences while ensuring both systems leverage modern language models for semantic processing, avoiding the unfair comparison of LLM-based versus non-LLM systems.

6.7.2. Performance Results

Table 3 summarizes the performance characteristics under controlled conditions. TB-CSPN demonstrated superior efficiency across all measured dimensions while maintaining equivalent semantic understanding capabilities.

The 62.5% performance improvement stems directly from TB-CSPN’s architectural efficiency: semantic coordination occurs through formal rule processing rather than additional LLM inference, reducing computational overhead while preserving semantic fidelity.

6.7.3. Architectural Efficiency Analysis

The empirical results reveal a fundamental architectural distinction that explains TB-CSPN’s efficiency gains. The performance differential stems not from different semantic capabilities, but from how each framework manages multi-agent coordination and process orchestration.

Dedicated Multi-Agent Environment vs. LLM-Mediated Coordination. TB-CSPN provides a dedicated multi-agent coordination substrate through its formal Petri net foundation and token-based communication model. This enables agents to interact through structured semantic channels while restricting LLM usage to information acquisition tasks where semantic understanding is essential.

LangGraph, in contrast, lacks a dedicated multi-agent environment and relies on LLMs to perform dual functions: both information acquisition (semantic understanding) and process management (agentic interaction coordination). This architectural choice forces LLM involvement in every coordination step, creating inefficiencies where formal methods would suffice.

Separation of Concerns: Information vs. Coordination. The 66.7% reduction in LLM calls achieved by TB-CSPN reflects this architectural principle. Both frameworks require LLM capabilities for semantic information acquisition—topic extraction from unstructured text. However, TB-CSPN delegates coordination responsibilities to its formal substrate, while LangGraph continues to rely on LLM inference for inter-agent communication, decision routing, and process orchestration.

This separation enables TB-CSPN to leverage LLMs where they excel (semantic understanding) while avoiding their use where formal methods are more appropriate (deterministic coordination logic). The result is a system that maintains semantic richness while achieving coordination efficiency through architectural specialization.

Process Orchestration Overhead. LangGraph’s reliance on LLM-mediated process management introduces latency and variability at each coordination point. Token-based communication in TB-CSPN eliminates this overhead by providing explicit semantic channels that enable direct agent-to-agent interaction without requiring LLM interpretation of coordination intent.

The performance improvements thus demonstrate the advantages of purpose-built multi-agent architectures over LLM-centric orchestration approaches that conflate information processing with process management responsibilities.

Scalability Implications. At enterprise scale, TB-CSPN’s throughput advantage (199.5 vs. 74.8 items/minute) enables processing of approximately 287,000 vs. 108,000 news items daily, representing a qualitative difference in operational capacity.

6.7.4. Cost-Benefit Analysis

The efficiency improvements translate into measurable economic advantages for production deployment. With current LLM API pricing (approximately $0.03 per 1K tokens), TB-CSPN’s 66.7% reduction in calls per item yields proportional cost savings:

Operational Costs: TB-CSPN processes 1000 news items for approximately $30 versus $90 for equivalent LangGraph deployment

Infrastructure Requirements: Lower latency enables higher concurrency with reduced compute resources

Reliability: Deterministic coordination reduces debugging complexity and operational overhead

These findings demonstrate that TB-CSPN’s architectural principles deliver not just theoretical elegance but measurable operational advantages in production scenarios requiring high-volume, low-latency semantic processing.

6.7.5. Implications for Agentic AI Architecture

The quantitative evaluation reveals a fundamental insight: the efficiency gains from TB-CSPN arise not from avoiding modern AI components, but from using them more strategically. By restricting LLM usage to tasks requiring semantic understanding while employing formal methods for coordination, TB-CSPN achieves the benefits of both paradigms without their individual limitations.

This hybrid approach suggests a design principle for next-generation agentic AI: leverage LLMs for semantic richness while maintaining formal coordination through structured rule systems and explicit token-based communication. The result is systems that are simultaneously more efficient, more predictable, and more amenable to verification than purely prompt-driven alternatives.

These empirical findings provide quantitative validation for the architectural advantages demonstrated throughout this case study and establish TB-CSPN as a viable framework for production agentic AI deployment.

7. Comparative Analysis

Building on the implementation described above and the empirical evaluation presented in

Section 6, we now formalize the architectural contrasts between TB-CSPN and leading orchestration toolkits introduced in

Section 2, focusing particularly on LangGraph and LangSmith.

Where the case study demonstrated specific performance advantages (62.5% faster processing, 66.7% fewer LLM calls), this section examines the underlying architectural differences that enable these improvements. We analyze the frameworks across twelve critical dimensions to understand how design philosophy translates into operational capabilities.

Table 4 contrasts the TB-CSPN architecture with LangGraph and LangSmith across twelve critical dimensions. Grounded in Colored Petri Nets and rule-based coordination, TB-CSPN offers formal semantics, token-based transitions, and a declarative coordination model. Its modular structure allows for the composition of agent behaviors through places, transitions, and tokens, and it supports concurrency and verifiable guard conditions. TB-CSPN accommodates three differentiated agent roles (supervisor, consultant, and worker) each of which is governed by interpretable rules and topic-based activation thresholds. The framework’s learning capabilities (e.g., G-Learning [

34]), formal verification methods, and traceable semantic flows further reinforce its suitability for high-assurance, adaptive, multiagent systems.

In contrast, LangGraph and LangSmith offer a practical toolkit for developing and monitoring LLM-driven workflows. Their design emphasizes procedural chaining via directed acyclic graphs and state-passing nodes. Although these systems are modular at the node level and enhanced by the LangSmith observability layer, they lack formal guarantees of concurrency and verification. Agents are usually monolithic LLM orchestrators, and adaptivity is limited to manual intervention.

Overall, TB-CSPN prioritizes explainability, compositionality, and agentic rigor, while LangGraph and LangSmith excel in tool maturity and developer accessibility. This juxtaposition highlights the broader tension between formalism and usability in the evolution of agentic AI architectures.

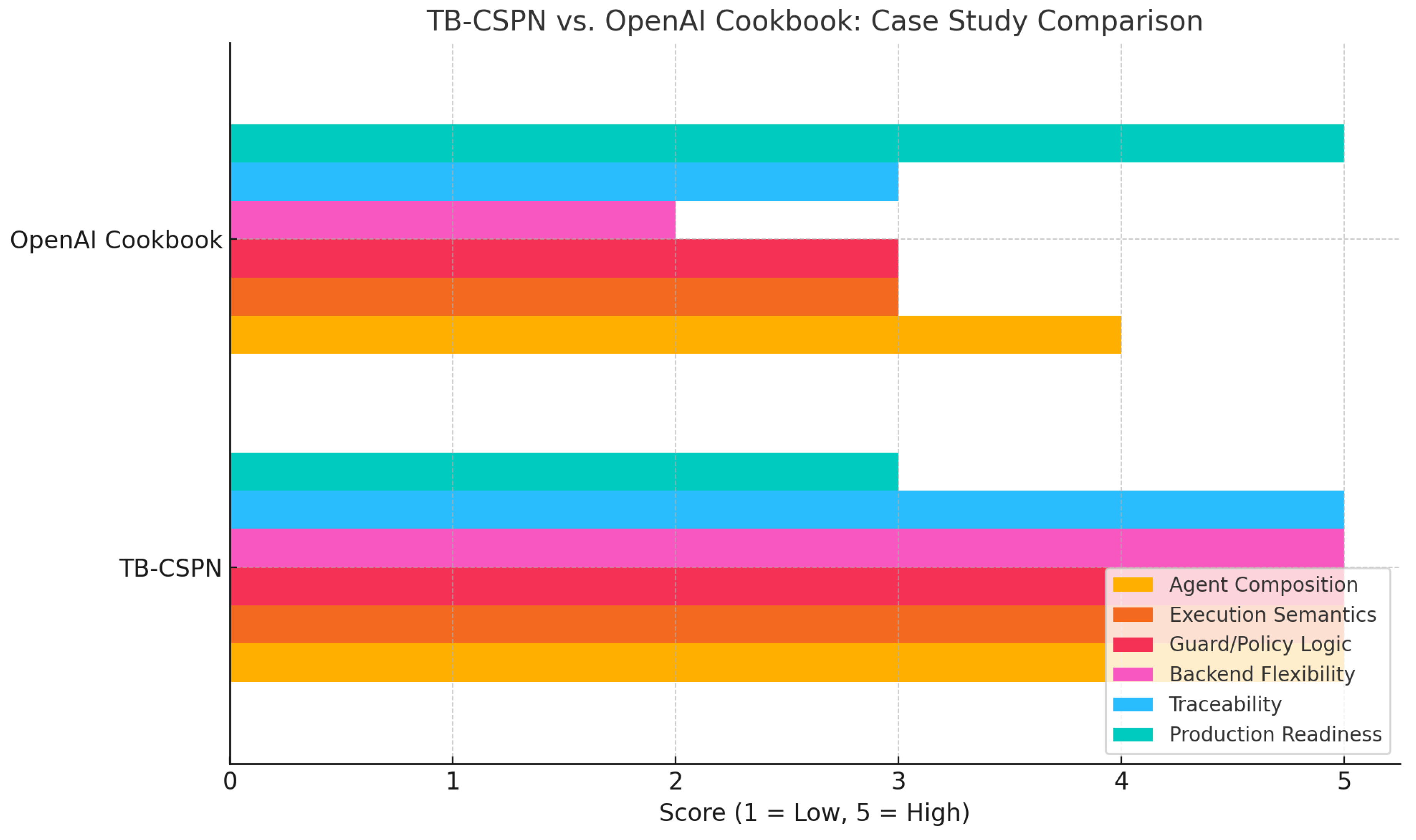

Figure 5 shows a qualitative comparison of the features of the TB-CSPN and OpenAI Cookbook agent frameworks across six dimensions: agent composition, execution semantics, guard logic, backend flexibility, traceability, and production readiness. TB-CSPN demonstrates strong formalism and modularity, particularly through its use of Petri net–based agent coordination, verifiable thresholds, and openness to heterogeneous AI backends. TB-CSPN excels in interpretability and supports traceable, role-specific workflows involving supervisors, consultants, and worker agents. In contrast, the OpenAI Cookbook prioritizes rapid deployment and LLM-centric collaboration, offering high usability and production maturity. However, it relies heavily on prompt engineering and lacks formal verification capabilities. Its agent composition is modular, yet it is constrained by message-passing patterns and tight coupling with the OpenAI stack. Overall, TB-CSPN prioritizes explainability, compositionality, and agentic rigor, while LangGraph and LangSmith excel in tool maturity and developer accessibility. This juxtaposition highlights the broader tension between formalism and usability in the evolution of agentic AI architectures. The comparative implementations and benchmarking methodologies used in this analysis are available in the public repository, enabling independent validation of these architectural trade-offs in production scenarios.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper demonstrates the need to shift beyond prompt chaining toward principled architectures for agentic AI. While popular frameworks such as LangGraph and AutoGen simulate agency through LLM orchestration, they fundamentally lack the autonomy, persistence, and formal coordination capabilities required for genuine multi-agent systems.

We introduce the TB-CSPN framework as a formal, token-driven alternative that enables modular, semantically grounded, multi-agent collaboration. TB-CSPN integrates LLM-based topic extraction with Colored Petri Nets to support hierarchical agents (supervisors, consultants, and workers) that interact through traceable, interpretable tokens rather than brittle prompt chains.

Our empirical evaluation demonstrates TB-CSPN’s architectural advantages over LLM-centric pipelines: 62.5% faster processing, 66.7% reduction in API calls, and 166.8% higher throughput while maintaining semantic fidelity. These improvements stem from TB-CSPN’s separation of semantic understanding (where LLMs excel) from coordination logic (where formal methods are superior), proving that efficiency gains arise not from avoiding modern AI components, but from using them strategically.

The framework’s formal foundation enables mathematical verification of coordination properties, comprehensive traceability of decision processes, and seamless integration of human expertise through centaurian architectures. Unlike prompt-dependent systems that conflate semantic processing with orchestration logic, TB-CSPN provides dedicated multi-agent coordination substrate that scales efficiently while preserving interpretability.

Implications for Agentic AI. Our results demonstrate that genuine agentic behavior necessitates structured communication and compositional design rather than sophisticated tool chaining. The architectural principles validated through TB-CSPN—topic-based semantic interlingua, threshold-driven coordination, and formal verification capabilities—establish a foundation for next-generation agentic systems that combine semantic richness with coordination efficiency.

Future Directions. Several research directions emerge from this work:

Scalability Analysis: Investigating TB-CSPN performance across larger agent populations and more complex coordination scenarios

Learning Integration: Developing adaptive topic extraction and threshold optimization mechanisms that maintain formal verification properties

Domain Expansion: Applying TB-CSPN principles to domains beyond financial analysis, including healthcare workflows, emergency response, and scientific collaboration

Human-AI Coevolution: Exploring dynamic role allocation between human and artificial agents based on expertise, context, and trust metrics

Standardization: Developing interoperability protocols for TB-CSPN systems to enable ecosystem-wide adoption

As agentic AI evolves from experimental prototypes to production systems, we advocate for architectures that prioritize formal coordination, semantic transparency, and hybrid human-AI collaboration over prompt engineering complexity. TB-CSPN offers a solid foundation for developing transparent, adaptive, and accountable systems capable of addressing real-world challenges requiring both semantic understanding and reliable coordination.

The complete implementation, evaluation benchmarks, and documentation are publicly available to enable community validation and extension of these architectural principles, supporting the broader goal of principled agentic AI development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; methodology, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; software, P.B. and R.P.; validation, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; formal analysis, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; investigation, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; resources, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; data curation, R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; writing—review and editing, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; visualization, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; supervision, U.M.B, P.B. and R.P.; project administration, U.M.B. and R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Remo Pareschi has been funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU under the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) National Innovation Ecosystem grant ECS00000041-VITALITY—CUP E13C22001060006.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the article. The complete implementation details, including the source code, API documentation, and usage examples, as discussed in

Section 5, are available in the public repository at

https://github.com/Aribertus/tb-cspn-poc.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used

DeepL Translator and

DeepL Write. These tools assisted in enhancing the language quality and translating certain sections originally written in German or Italian.

Figure 5 was generated by

ChatGPT 4.0 based on input from the authors. They have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A2A |

Agent-to-Agent |

| ACP |

Agent Communication Protocol |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ANP |

Agent Network Protocol |

| BDI |

Belief-Desire-Intention |

| CNP |

Contract Net Protocol |

| CPN |

Colored Petri Nets |

| LLM |

Large Language Models |

| MAS |

Multi-Agent Systems |

| MCP |

Model Context Protocol |

| R2A2 |

Reflective Risk-Aware Agent Architecture |

| RAG |

Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| TB-CSPN |

Topic-Based Communication Space Petri Net |

References

- Li, Q.; Xie, Y. From Glue-Code to Protocols: A Critical Analysis of A2A and MCP Integration for Scalable Agent Systems. arXiv preprint 2025, abs/2505.03864. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, M.; Jennings, N.R. Intelligent Agents: Theory and Practice. The Knowledge Engineering Review 1995, 10, 115–152.

- Nwana, H.S. Software agents: an overview. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 1996, 11, 205–244. [CrossRef]

- Sycara, K.P.; Zeng, D.D. Coordination of Multiple Intelligent Software Agents. Int. J. Cooperative Inf. Syst. 1996, 5, 181–212. [CrossRef]

- Nardi, B.A.; Miller, J.R.; Wright, D.J. Collaborative, Programmable Intelligent Agents. Commun. ACM 1998, 41, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Padgham, L.; Winikoff, M. Developing Intelligent Agent Systems – A Practical Guide; Wiley series in agent technology, Wiley, 2004.

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Yuan, X.; Dong, G.; Di, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, D. Prompting Frameworks for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv preprint 2023, abs/2311.12785. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, M.J. Introduction to Multiagent Systems; Wiley, 2002.

- Rao, A.S.; Georgeff, M.P. BDI Agents: From Theory to Practice. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the First International Conference on Multiagent Systems, June 12-14, 1995, San Francisco, California, USA; Lesser, V.R.; Gasser, L., Eds. The MIT Press, 1995, pp. 312–319.

- Smith, R.G. The Contract Net Protocol: High-Level Communication and Control in a Distributed Problem Solver. IEEE Trans. Computers 1980, 29, 1104–1113. [CrossRef]

- Borghoff, U.M.; Pareschi, R.; Fontana, F.A.; Formato, F. Constraint-Based Protocols for Distributed Problem Solving. Sci. Comput. Program. 1998, 30, 201–225. [CrossRef]

- LangChain. LangGraph. https://langchain-ai.github.io/langgraph/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-03-15.

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, E.; Li, B.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. AutoGen: Enabling Next-Gen LLM Applications via Multi-Agent Conversation Framework. arXiv preprint 2023, abs/2308.08155. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Ahmadi, N.B.; Ahmadi, N.B.; Vogel, I.; Semmann, M.; Biemann, C. CollEX - A Multimodal Agentic RAG System Enabling Interactive Exploration of Scientific Collections. arXiv preprint 2025, abs/2504.07643. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. OpenAI Cookbook. https://github.com/openai/openai-cookbook, 2025. Accessed on June 25, 2025.

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: A Conceptual Taxonomy, Applications and Challenges. arXiv preprint 2025, abs/2505.10468. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Luo, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, J. A Survey on Autonomy-Induced Security Risks in Large Model-Based Agents. arXiv preprint 2025, abs/2506.23844. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.B.; Kuppan, K.; Bhaskaracharya, D. Agentic AI: Autonomous Intelligence for Complex Goals - A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 18912–18936. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Chen, W.; Guo, X.; He, W.; Ding, Y.; Hong, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Jin, S.; Zhou, E.; et al. The Rise and Potential of Large Language Model Based Agents: A Survey. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68. [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, M.E. Embodied Cognition and Temporally Extended Agency. Synth. 2018, 195, 2089–2112. [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, M. Agency; The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter Edition), 2019.

- Russell, S.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach; Prentice Hall, 2010.

- Churchland, P.M. Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes. The Journal of Philosophy 1981, 78, 67–90.

- Dennett, D.C. True Believers: The Intentional Strategy and Why It Works. Scientific Explanation: Papers based on Herbert Spencer Lectures 1981, pp. 17–36.

- Dennett, D.C. The Intentional Stance; MIT Press, 1987.

- Quine, W.V.O. Word and Object; MIT Press, 1960.

- Brooks, R.A. Intelligence without Representation. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence: Theoretical Foundations, 1991, pp. 139–159.

- Brooks, R. A Robust Layered Control System for a Mobile Robot. IEEE Journal on Robotics and Automation 1986, 2, 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Pareschi, R. Beyond Human and Machine: An Architecture and Methodology Guideline for Centaurian Design. Sci 2024, 6. [CrossRef]

- Saghafian, S.; Idan, L. Effective Generative AI: The Human-Algorithm Centaur. arXiv preprint 2024, abs/2406.10942. [CrossRef]

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. An Organizational Theory for Multi-Agent Interactions Integrating Human Agents, LLMs, and Specialized AI. Discover Computing 2025, 28. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Aalst, W.M.P. The application of Petri Nets to Workflow Management. Journal of Circuits, Systems and Computers 1998, 08, 21–66.

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. Human-Artificial Interaction in the Age of Agentic AI: A System-Theoretical Approach. Frontiers in Human Dynamics 2025, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.; Pakman, A.; Tishby, N. Taming the Noise in Reinforcement Learning via Soft Updates. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, UAI 2016, June 25-29, 2016, New York City, NY, USA; Ihler, A.; Janzing, D., Eds. AUAI Press, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).