Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

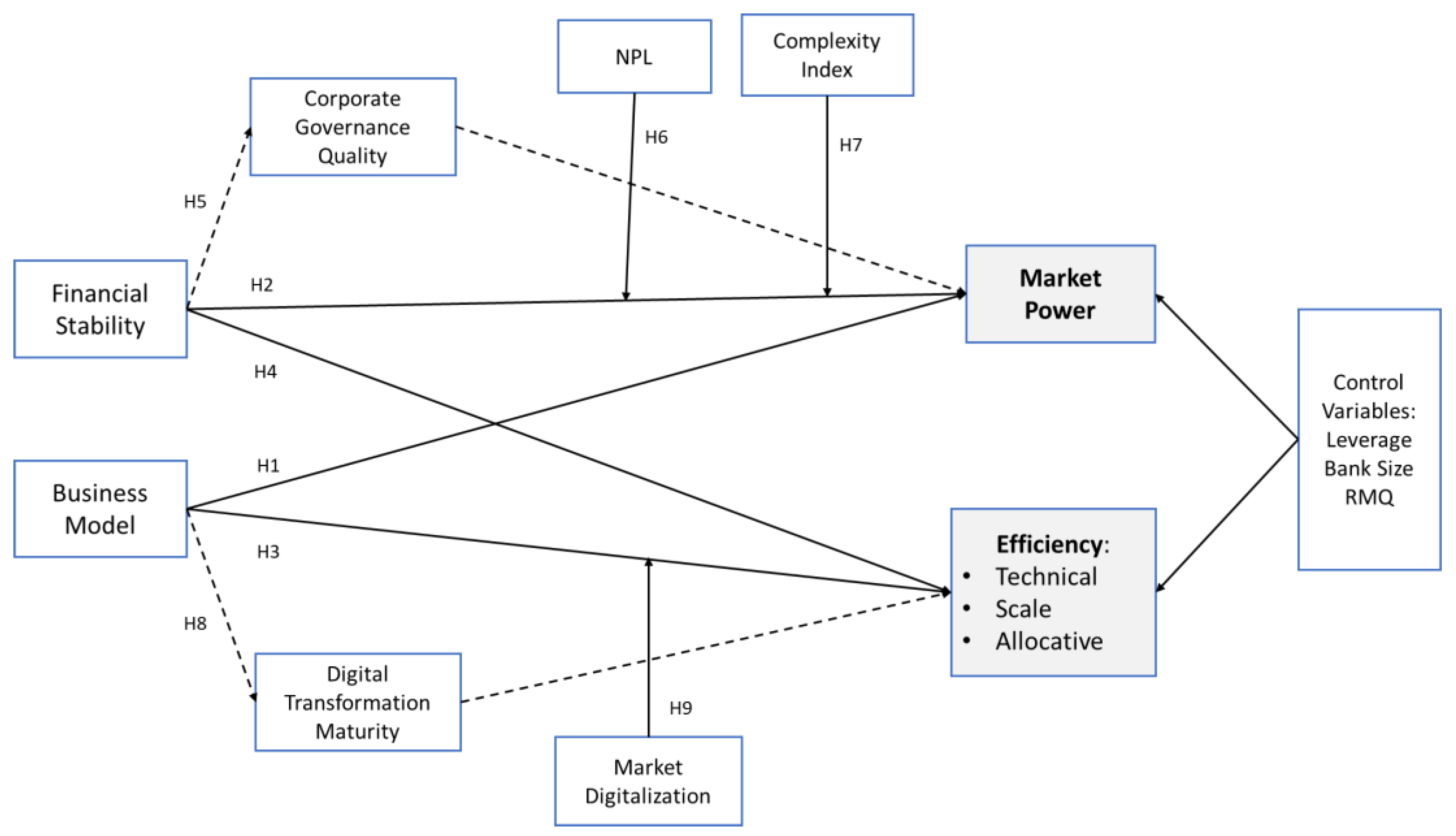

2. Literature Review, Theoretical Framework, and Hypothesis

2.1. Business Model Diversification, Financial Stability, and Bank Market Power

2.2. Diversification, Stability, and Multidimensional Bank Efficiency

2.3. Governance as a Strategic Transmission Mechanism

2.4. The Boundaries of Market Power: Credit Risk and Institutional Complexity

2.5. Digital Transformation Maturity as an Internal Strategic Bridge

2.6. Market Digitalization as an External Contingency Factor

2.7. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

| Variable | Symbol | Proxy / Measurement Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Business model | NNIN | Non-Interest Income / Operating Income. |

| Bank stability | Z-Score | |

| Market power | LI | |

| Technical efficiency | TE | DEA Score (VRS Model). Input-oriented. |

| Allocative efficiency | AE | DEA Score reflecting optimal input mix at given prices. |

| Scale efficiency | SE | Ratio of DEA CRS to DEA VRS |

| Digital transformation | DTM | Composite index of infrastructure, operations, payments, IT intensity |

| Corporate governance quality | CGQ | Composite index of board, ownership, disclosure, incentives |

| Market digitalization | MDL | Composite index of national digital infrastructure, financial inclusion, regulatory readiness, and policy support |

| Complexity index | CI | Composite index of asset complexity, geographic complexity, and organizational complexity |

| Non-performing loan | NPL | Non-Performing Loans / Total Gross Loans |

| Bank size | Size | Natural Logarithm of Total Assets |

| Leverage | Leverage | Total Debt / Total Equity |

| Risk management quality | RMQ | Weighted Score (0-100): Monitoring, Assessment, Compliance, Controls, Audit |

3. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | All countries | ASEAN | MENA | ||||||

| Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| NNIN | 8,821.20 | 3,927.56 | 10,244.92 | 12,483.42 | 8,801.49 | 11,260.67 | 4,450.16 | 1,608.70 | 6,632.12 |

| Z-Score | 54.91 | 43.43 | 37.35 | 67.93 | 63.04 | 39.70 | 39.38 | 29.46 | 27.18 |

| LI | 0.9736 | 0.9745 | 0.0121 | 0.9751 | 0.9772 | 0.0133 | 0.9718 | 0.9729 | 0.0102 |

| TE | 0.7841 | 0.8265 | 0.1901 | 0.7327 | 0.7465 | 0.2086 | 0.8454 | 0.8735 | 0.1432 |

| SE | 0.9031 | 0.9740 | 0.1409 | 0.8608 | 0.9530 | 0.1661 | 0.9536 | 0.9805 | 0.0775 |

| AE | 0.7245 | 0.7290 | 0.1801 | 0.6963 | 0.7110 | 0.1916 | 0.7580 | 0.7515 | 0.1592 |

| NPL | 3.6250 | 3.5017 | 1.9435 | 3.0930 | 3.0897 | 1.7381 | 4.2598 | 3.9755 | 1.9872 |

| CI | 0.5160 | 0.5689 | 0.4483 | 0.4127 | 0.1664 | 0.4423 | 0.6393 | 0.9020 | 0.4241 |

| Leverage | 1.3543 | 1.3475 | 0.3193 | 1.3071 | 1.3136 | 0.2856 | 1.4106 | 1.4340 | 0.3475 |

| RMQ | 0.7790 | 0.7796 | 0.1035 | 0.8042 | 0.7931 | 0.0770 | 0.7489 | 0.7395 | 0.1217 |

| Bank Size | 12.3789 | 12.4933 | 1.5401 | 12.6834 | 12.9059 | 1.5658 | 12.0154 | 12.0383 | 1.4286 |

| DTM | 0.5484 | 0.5432 | 0.0948 | 0.5360 | 0.5282 | 0.1008 | 0.5632 | 0.5599 | 0.0849 |

| CGQ | 0.5761 | 0.5658 | 0.1062 | 0.5964 | 0.5819 | 0.1222 | 0.5518 | 0.5554 | 0.0767 |

| MDL | 0.4212 | 0.4144 | 0.1031 | 0.3897 | 0.3804 | 0.0930 | 0.4588 | 0.4510 | 0.1021 |

4.2. Correlation Analysis of Latent Variables

4.3. Measurement Model Assessment

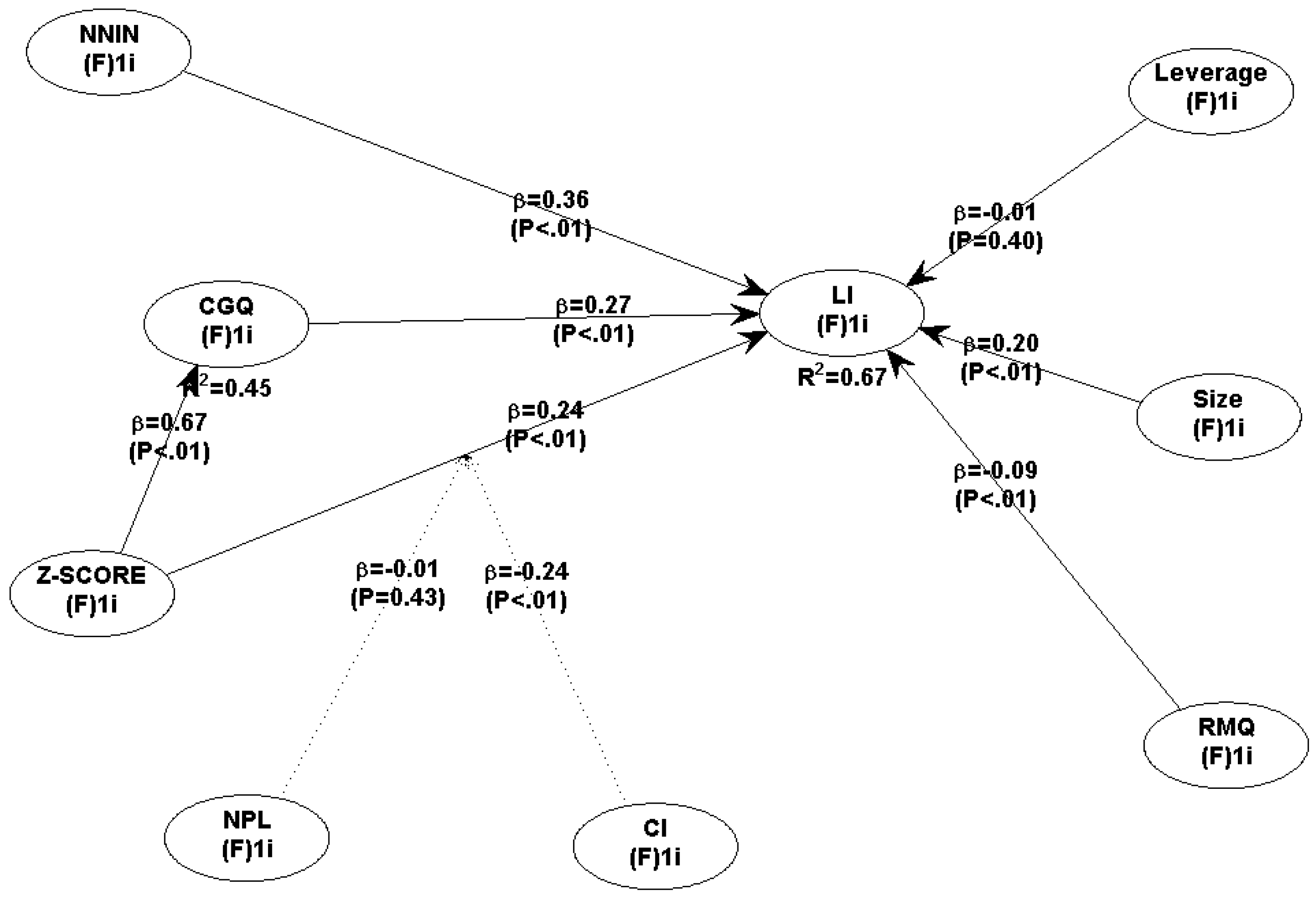

4.4. Structural Model Results: Determinants of Market Power

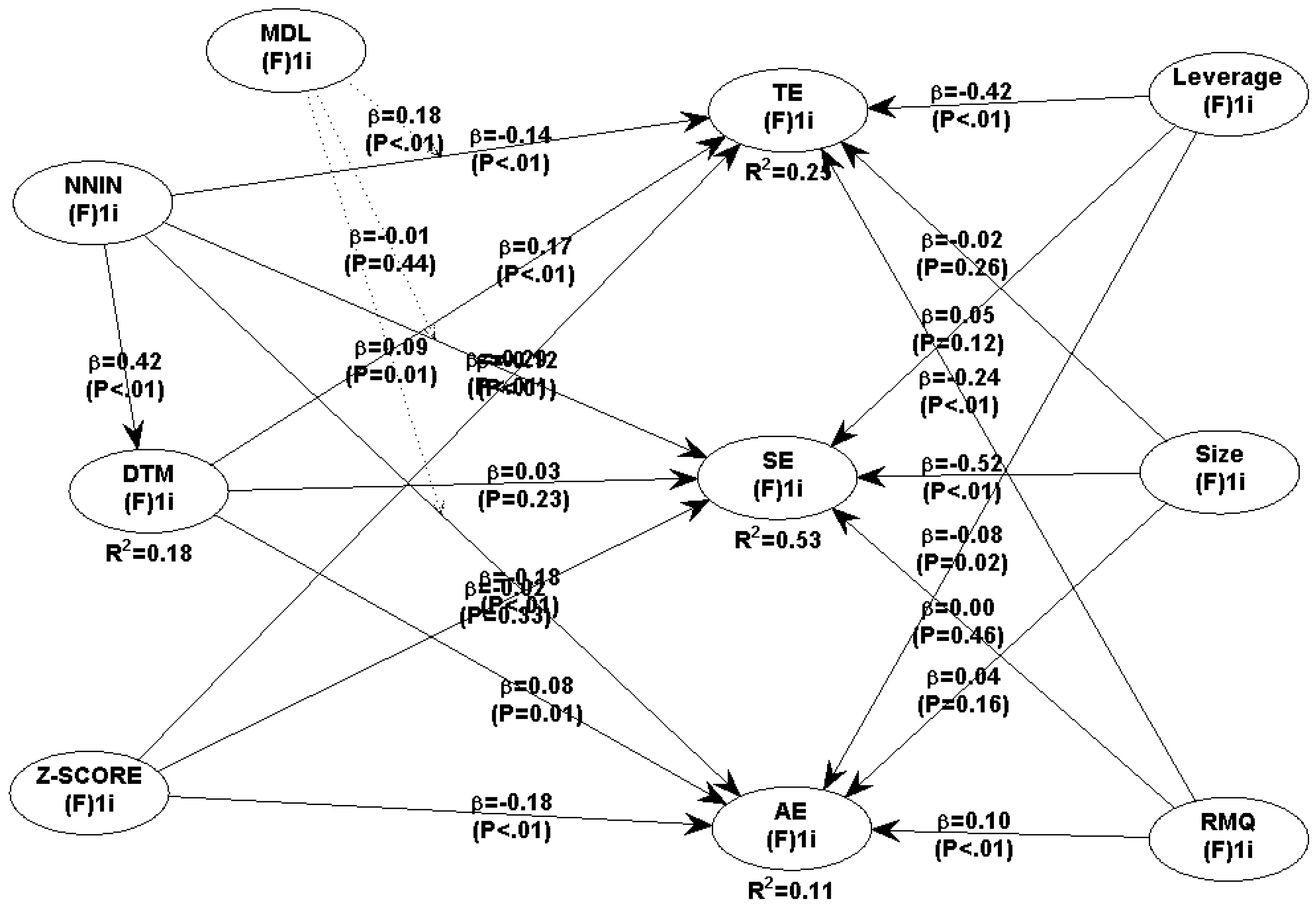

4.5. Structural Model Results: Determinants of Bank Efficiency

4.6. Multi-Group Analysis Results (ASEAN vs. MENA)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu Khalaf, B.; Awad, A. B.; Ellis, S. The Impact of Non-Interest Income on Commercial Bank Profitability in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2024, Vol. 17(Issue 3), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderogba, T.; Adekunle, I. A.; Atoyebi, O. E. Post-Crisis Bank Profitability in BRICS: A CAMEL Approach. Journal of Emerging Market Finance 2025, 24(3), 360–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akins, B.; Li, L.; Ng, J.; Rusticus, T. Bank Competition and Financial Stability: Evidence from the Financial Crisis. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2016, 51, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A. L. Income diversification and bank efficiency in an emerging market. Managerial Finance 2015, 41(12), 1318–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A. L.; Tetteh, M. L. Non-Interest Income and Bank Efficiency in Ghana: A Two-Stage DEA Bootstrapping Approach. Journal of African Business 2017, 18(1), 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, S.; Mohammad, A. R.; Abd. Wahab, N. Bank diversification, stability and oil price in MENA region. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 2023, 16(6), 1074–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, M. Noninterest income and bank performance in Europe and Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Cogent Business & Management 2025, 12(1), 2500678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anani, M. Geographic complexity and bank risk: Evidence from cross-border banks in Africa. Economic Systems 2024, 48(3), 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argimón, I.; Rodríguez-Moreno, M. Risk and control in complex banking groups. Journal of Banking & Finance 2022, 134, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, R.; Challita, S.; Cucinelli, D. Cooperative banks, business models and efficiency: a stochastic frontier approach analysis. Annals of Operations Research 2023, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, J. S. Relation of Profit Rate to Industry Concentration: American Manufacturing, 1936-1940. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1951, 65(3), 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banna, H.; Alam, M. R. Impact of digital financial inclusion on ASEAN banking stability: implications for the post-Covid-19 era. Studies in Economics and Finance 2021, 38(2), 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, C.; Zotti, R. Bank Performance, Financial Stability and Market Concentration: Evidence From Cooperative and Non-Cooperative Banks. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 2019, 90(1), 103–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccalli, E. Does IT investment improve bank performance? Evidence from Europe. Journal of Banking & Finance 2007, 31(7), 2205–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Hasan, I.; Zhou, M. The Effects of Focus versus Diversification on Bank Performance: Evidence from Chinese Banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 2010, 34, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N. The Profit-Structure Relationship in Banking--Tests of Market-Power and Efficient-Structure Hypotheses. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 1995, 27(2), 404–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N.; DeYoung, R. Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. Journal of Banking & Finance 1997, 21(6), 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N.; Hannan, T. H. The Efficiency Cost of Market Power in the Banking Industry: A Test of the “Quiet Life” and Related Hypotheses. The Review of Economics and Statistics 1998, 80(3), 454–465. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2646754. [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N.; Imbierowicz, B.; Rauch, C. The Roles of Corporate Governance in Bank Failures during the Recent Financial Crisis. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 2016, 48(4), 729–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N.; Klapper, L. F.; Turk-Ariss, R. Chapter 10: Bank competition and financial stability. In Handbook of Competition in Banking and Finance; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M. Corporate Governance, Market Competition and Performance of Indian Banks. Global Business Review 2024, 09721509241269416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, B. P. Effects of non-performing loan on profitability of commercial banks in Nepal. The Journal Of Indian Management 2020, 10(4), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, C. M.; Goldberg, L. S. Complexity and riskiness of banking organizations: Evidence from the International Banking Research Network. Journal of Banking & Finance 2022, 134, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, L. A.; Sigahi, T. F. A. C.; Rampasso, I. S.; Leal Filho, W.; Anholon, R. Impacts of digitization on operational efficiency in the banking sector: Thematic analysis and research agenda proposal. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2024, 4(1), 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, J.; Herring, R. The Corporate Complexity of Global Systemically Important Banks. Journal of Financial Services Research 2016, 49(2), 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetorelli, N.; Goldberg, L. S. Measures of global bank complexity. FRBNY Economic Policy Review 2014, 20(2), 107–126. Available online: https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/2014/1412ceto.html.

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W. W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research 1978, 2(6), 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Chien, M.-S.; Lee, C.-C. ICT diffusion, financial development, and economic growth: An international cross-country analysis. Economic Modelling 2021, 94, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortareas, G. E.; Garza-Garcia, J. G.; Girardone, C. Banking Sector Performance in Latin America: Market Power versus Efficiency. Review of Development Economics 2011, 15(2), 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronopoulos, D. K.; Girardone, C.; Nankervis, J. C. Are there any cost and profit efficiency gains in financial conglomeration? Evidence from the accession countries. The European Journal of Finance 2011, 17(8), 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citterio, A.; King, T.; Locatelli, R. Is digital transformation profitable for banks? Evidence from Europe. Finance Research Letters 2024, 70, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S.; Coleman, N.; Donnelly, M. “Low-For-Long” interest rates and banks’ interest margins and profitability: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2018, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinelli, D. The Impact of Non-performing Loans on Bank Lending Behavior: Evidence from the Italian Banking Sector. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics 2015, 8(16 SE-), 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curi, C.; Lozano-Vivas, A.; Zelenyuk, V. Foreign bank diversification and efficiency prior to and during the financial crisis: Does one business model fit all? Journal of Banking & Finance 2015, 61, S22–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pati, A. P. Bank market power drivers: comparative insights from India and Bangladesh. South Asian Journal of Business Studies 2025, 14(2), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedu, V.; Chitan, G. The Influence of Internal Corporate Governance on Bank Performance - An Empirical Analysis for Romania. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2013, 99, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, R.; Roland, K. P. Product Mix and Earnings Volatility at Commercial Banks: Evidence from a Degree of Total Leverage Model. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2001, 10(1), 54–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, A.-T.; Lin, K.-L.; Doong, S.-C. What drives bank efficiency? The interaction of bank income diversification and ownership. International Review of Economics & Finance 2018, 55, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasiani, E.; Wang, Y. Bank holding company diversification and production efficiency. Applied Financial Economics 2012, 22(17), 1409–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelisi, F.; Marques-Ibanez, D.; Molyneux, P. Efficiency and Risk in European Banking. Journal of Banking & Finance 2011, 35, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, H.; Tan, Y. A new way to estimate market power in banking. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2022, 73(2), 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuseini, E. I. Institutional quality-banking efficiency nexuses in Africa. How does ICT moderate? Information Technology for Development 2025, 31(4), 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuseini, E. I.; Ibrahim, M.; Adam, I. O.; Vinh Vo, X. Re-examining the moderating role of ICT in the nexus between financial development and banking efficiency: evidence from Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance 2024, 12(1), 2325833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, T. P. Changing Business Models in Banking and Systemic Risk. In Management of Permanent Change; Albach, H., Meffert, H., Pinkwart, A., Reichwald, R., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 2015; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi Asl, M.; Rashidi, M. M.; Ghorbani, A. Empirical evaluation of structure-conduct-performance paradigm as applied to the Iranian Islamic banking system. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 2021, 15(4), 759–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Kashiramka, S. FinTech Advancement in the Banking Industry: Is It Driving Efficiency? International Journal of Finance & Economics 2025, n/a(n/a). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerry, N.; Wallmeier, M. Valuation of diversified banks: New evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance 2017, 80, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, H. M. M. Does the efficiency of banks adversely affect financial stability? A Comparative study between traditional and Islamic banks: Evidence from Egypt. Banks and Bank Systems 2022, 17(2), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herwald, S.; Voigt, S.; Uhde, A. The impact of market concentration and market power on banking stability – evidence from Europe. Journal of Risk Finance 2024, 25(3), 510–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, N.; Inoue, K.; Watanabe, S. Enjoying the quiet life: Corporate decision-making by entrenched managers. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 2018, 47, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C.; Meckling, W. F. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadima, M.; Louri, H. Non-performing loans in the euro area: Does bank market power matter? International Review of Financial Analysis 2020, 72, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkowska, R.; Acedański, J. The effect of corporate board attributes on bank stability. Portuguese Economic Journal 2020, 19(2), 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, A.; Carvallo, O. Financial Stability, Competition and Efficiency in Latin American and Caribbean Banking. Journal of Applied Economics 2014, 17(2), 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. B.; Fareed, M.; Salameh, A. A.; Hussain, H. Financial Innovation, Sustainable Economic Growth, and Credit Risk: A Case of the ASEAN Banking Sector. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2021, 9, 729922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, P.; Ng, S.; Ogawa, S.; Sahay, R. Measuring Digital Financial Inclusion in Emerging Market and Developing Economies: A New Index. Asian Economic Policy Review 2022, 17(2), 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Jung, J.; Cho, S. Can ESG mitigate the diversification discount in cross-border M&A? Borsa Istanbul Review 2022, 22(3), 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2012, 13(7), 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Sondershaus, T.; Tonzer, L. Complexity and bank risk during the financial crisis. Economics Letters 2017, 150, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriebel, J.; Debener, J. The effect of digital transformation on bank performance. SSRN. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3461594.

- Kulu, E.; Osei, B. Drivers of financial stability gap: evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 2023, 16(1), 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, L.; Levine, R. Is there a diversification discount in financial conglomerates? Journal of Financial Economics 2007, 85(2), 331–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, L.; Ratnovski, L.; Tong, H. Bank size, capital, and systemic risk: Some international evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance 2016, 69, S25–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, A.; Venturelli, V. The Diversification Strategy of European Banks: Determinants and Effects on Efficiency and Profitability. SSRN Electronic Journal 2005, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laryea, E.; Ntow-Gyamfi, M.; Alu, A. A. Nonperforming loans and bank profitability: evidence from an emerging market. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 2016, 7(4), 462–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. D. Q.; Nguyen, D. T.; Ngo, T. Revisiting the Quiet-Life Hypothesis in the Banking Sector: Do CEOs’ Personalities Matter? International Journal of Financial Studies 2024, Vol. 12(Issue 1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Yang, S.-J.; Chang, C.-H. Non-interest income, profitability, and risk in banking industry: A cross-country analysis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 2014, 27, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, D.; Ma, S.; Jun, A. Enhancing bank stability from diversification and digitalization perspective in ASEAN. Studies in Economics and Finance 2023, 40(4), 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Kong, Y.; Sampson; Bentum-Micah, G.; Michael. Corporate Governance and Banking Stability: The Case of Universal Banks in Ghana. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration 2020, 8(1), 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Stasinakis, C.; Yeo, W. M.; Fernandes, F. D. S. Fintech, financial development and banking efficiency: evidence from Chinese commercial banks. The European Journal of Finance 2025, 31(10), 1245–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kim, S. Diversification Strategies and Digital Transformation: Evidence from Chinese-Listed Enterprises. Cuadernos de Economía 2024, 47(134), 169–179. Available online: https://cude.es/submit-a-manuscript/index.php/CUDE/article/view/595.

- Lin, Y.; Shi, X.; Zheng, Z. Diversification strategy and bank market power: does foreign ownership matter? Applied Economics Letters 2021, 28(4), 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. L.; Naveed, M. M.; Mustafa, S.; Naveed, M. T. Analysing the impact of digital technology diffusion on the efficiency and convergence process of the commercial banking industry of Pakistan. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11(1), 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J. A.; Rose, A. K.; Spiegel, M. M. Why have negative nominal interest rates had such a small effect on bank performance? Cross country evidence. European Economic Review 2020, 124, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhichi, A.; Louati, S.; Boujelbene, Y. Market-power, stability and risk-taking: an analysis surrounding the riba-free banking. Review of Accounting and Finance 2019, 18(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lown, C.; Osler, C.; Strahan, P.; Sufi, A. The Changing Landscape of the Financial Services Industry: What Lies Ahead? Economic Policy Review 2000, 6, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S. B.; Podsakoff, P. M.; Jarvis, C. B. The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions. The Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90(4), 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghyereh, A. I.; Awartani, B. The effect of market structure, regulation, and risk on banks efficiency: Evidence from the Gulf cooperation council countries. Journal of Economic Studies 2014, 41(3), 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamatzakis, E.; Alexakis, C.; Yahyaee; Al, K.; Pappas, V.; Mobarek, A.; Mollah, S. Does corporate governance affect the performance and stability of Islamic banks? Corporate Governance 2023, 23(4), 888–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, A. G.; Bădîrcea, R. M.; Gherțescu, C.; Manta, L. F. How Does the Nexus Between Digitalization and Banking Performance Drive Digital Transformation in Central and Eastern European Countries? Electronics 2024, Vol. 13(Issue 22), 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateev, M.; Sahyouni, A.; Tariq, M. U. Bank regulation, ownership and risk taking behavior in the MENA region: policy implications for banks in emerging economies. Review of Managerial Science 2023, 17(1), 287–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I.; Spilbergs, A.; Verdenhofs, A.; Natrins, A.; Arefjevs, I.; Volkova, T. Digital Transformation as a Driver of the Financial Sector Sustainable Development: An Impact on Financial Inclusion and Operational Efficiency. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, D. G.; Halme, L.; Liuksila, A. Corporate Governance and Financial Stability. In Improving Banking Supervision; Mayes, D. G., Halme, L., Liuksila, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2001; pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M. D.; Uddin, H. Efficiency and stability: A comparative study between islamic and conventional banks in GCC countries. Future Business Journal 2017, 3(2), 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, S. N.; Hong, V. N. T.; Le Hoang, L.; Thuy, T. N. T. Does banking market power matter on financial stability? Management Science Letters 2020, 10(2), 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranda, Z. Financial distress and corporate governance in Zimbabwean banks. Corporate Governance 2006, 6(5), 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc Nguyen, K. Revenue Diversification, Risk and Bank Performance of Vietnamese Commercial Banks. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2019, Vol. 12(Issue 3), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. T.; Le, T. D. Q.; Tran, S. Competition and bank financial stability: evidence from an emerging economy. Cogent Business and Management 2024, 11(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. T. N. Impact of e-government development, economic growth and government management efficiency on financial performance of commercial banks in ASEAN countries. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking 2025, 9(3), 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J. The relationship between net interest margin and noninterest income using a system estimation approach. Journal of Banking & Finance 2012, 36(9), 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Perera, S.; Skully, M. Bank market power, ownership, regional presence and revenue diversification: Evidence from Africa. Emerging Markets Review 2016, 27, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. H.; Pham, D. T. B. Income diversification and cost-efficiency of Vietnamese banks. International Journal of Managerial Finance 2020, 16(5), 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. L. A. Diversification and bank efficiency in six ASEAN countries. Global Finance Journal 2018, 37, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. H.; Phan, G. Q.; Wong, W.-K.; Moslehpour, M. The influence of market power on liquidity creation of commercial banks in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 2022, 30(3), 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Peng, K.; Wang, S.; Ashraf, B. N. The Impact of Revenue Diversification on Bank Profitability and Stability: Empirical Evidence from South Asian Countries. International Journal of Financial Studies 2018, Vol. 6(Issue 2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oanh, D. L. K.; Loc, N. H. V.; Nga, D. Q. The Impact of Non-interest Income on Vietnamese Bank Performance BT. In Partial Identification in Econometrics and Related Topics; Ngoc Thach, N., Trung, N. D., Ha, D. T., Kreinovich, V., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024; pp. 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarewaju, O. M. Income Diversification in Low Income Sub-Saharan African Countries’ Commercial Banks: A “Blessing” or “Curse”? Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia 2018, 18(2), 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, O.; Nurmakhanova, M. The Effect of Market Power on Bank Credit Risk-Taking and Bank Stability in Kazakhstan. Transition Studies Review 2013, 20(3), 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.; Power, M.; Ashby, S. Navigating Institutional Complexity: The Production of Risk Culture in the Financial Sector. Journal of Management Studies 2017, 54(2), 154–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. H. A.; Doan, N. T. Global bank complexity and financial fragility around the world. Economic Systems 2023, 47(1), 101057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qori’ah, C. G.; Wardhono, A.; Yaqin, M.; Nasir, M. A. Market Power and Financial Stability : An Empirical Study of the Banking Industry in Selected ASEAN Countries. IRJEMS International Research Journal of Economics and Management Studies 2025, 4(11), 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, S. A.; Aisyah, E. N. Corporate Social Responsibility, Good Corporate Governance and Financial Sustainability: A Financial Stability Role. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting 2025, 25(2), 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifu, I. A.; Okunoye, I. A.; Aminu, A. The effect of ICT on financial sector development in Africa: does regulatory quality matter? Information Technology for Development 2024, 30(3), 424–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repullo, R. Capital requirements, market power, and risk-taking in banking. Journal of Financial Intermediation 2004, 13(2), 156–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Y. Examining the relationship between bank stability and earnings quality in Islamic and conventional banks. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 2020, 13(5), 803–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Pedersen, C. L. Digitization capability and the digitalization of business models in business-to-business firms: Past, present, and future. Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 86, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, A.; Kashiramka, S. Profitability–Stability Nexus in Commercial Banks: Evidence from BRICS. Global Business Review 2023, 09721509231184765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakouvogui, K.; Shaik, S. Impact of financial liquidity and solvency on cost efficiency: evidence from US banking system. Studies in Economics and Finance 2020, 37(2), 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setianto, R. H.; Azman-Saini, W. N. W.; Law, S. H.; Ahmad, A. H.; Mohd Daud, S. N. Does financial inclusion affect bank market power? International evidence. Finance Research Letters 2025, 85, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanti, R.; Siregar, H.; Zulbainarni, N.; Tony. Revolutionizing Banking: Neobanks’ Digital Transformation for Enhanced Efficiency. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2024, Vol. 17(Issue 5), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soedarmono, W.; Machrouh, F.; Tarazi, A. Bank market power, economic growth and financial stability: Evidence from Asian banks. Journal of Asian Economics 2011, 22(6), 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiroh, K. J. Diversification in Banking: Is Noninterest Income the Answer. Journal of Money Credit and Banking 2004, 36, 853–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiroh, K.; Rumble, A. The Dark Side of Diversification: The Case of US Financial Holding Companies. Journal of Banking & Finance 2006, 30, 2131–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1974, 36(2), 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, R. M. FinTech, BigTech, and the Future of Banks. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 2019, 31(4), 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, J.; Walyoto, S. The Effect of Corporate Governance on Financial Performance. Journal of Management and Islamic Finance 2022, 2(1), 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, B. M.; Fazio, D. M.; Cajueiro, D. O. The effects of loan portfolio concentration on Brazilian banks’ return and risk. Journal of Banking and Finance 2011, 35(11), 3065–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Anchor, J. Does competition only impact on insolvency risk? New evidence from the Chinese banking industry. International Journal of Managerial Finance 2017, 13(3), 332–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Ahmmed, M. Islamic Banking and Green Banking for Sustainable Development: Evidence from Bangladesh. In Al-Iqtishad: Jurnal Ilmu Ekonomi Syariah; 2018; Volume 10, pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyarthi, H. Dynamics of income diversification and bank performance in India. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 2019, 12(3), 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, N. L.; Pham, H. M.; Le, T. T.; Nguyen, V. C.; Nguyen, T. H. T. Information and communication technology as a catalyst for bank efficiency: Empirical evidence from Vietnam. Asia and the Global Economy 2025, 5(2), 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudin, A.; Solikhah, B. Corporate governance implementation rating in Indonesia and its effects on financial performance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 2017, 17, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 1984, 5(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, M.; Chen, M.; Jeon, B. N. Market power and risk-taking of banks: Some semiparametric evidence from emerging economies. Emerging Markets Review 2019, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeddou, N. Ownership structure and bank performance: the impact of market competition. Applied Economics 2024, 56(49), 5987–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Strauss, J.; Zuo, L. The Digitalization Transformation of Commercial Banks and Its Impact on Sustainable Efficiency Improvements through Investment in Science and Technology. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13(Issue 19), 11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NNIN | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 2. Z-Score | 0.471*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 3. LI | 0.529*** | 0.603*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 4. CGQ | 0.429*** | 0.663*** | 0.578*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 5. NPL | −0.077** | −0.205*** | −0.040 | −0.450*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 6. CI | −0.154*** | −0.633*** | 0.011 | −0.311*** | 0.113*** | 1.000 | |||

| 7. Leverage | −0.162*** | −0.196*** | −0.181*** | −0.456*** | 0.607*** | 0.049*** | 1.000 | ||

| 8. Size | 0.219*** | 0.146*** | 0.114*** | 0.378*** | −0.479*** | 0.051*** | −0.400*** | 1.000 | |

| 9. RMQ | 0.126*** | 0.287*** | 0.166*** | 0.446*** | −0.397*** | −0.164*** | −0.347*** | 0.245*** | 1.000 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NNIN | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 2. Z-Score | 0.471*** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 3. Leverage | −0.162*** | −0.196*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 4. Size | 0.219*** | 0.146*** | −0.400*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 5. RMQ | 0.126*** | 0.287*** | −0.347*** | 0.245*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 6. TE | −0.086** | −0.092** | −0.271*** | −0.057 | −0.098** | 1.000 | ||||

| 7. SE | −0.588*** | −0.325*** | 0.181*** | −0.295*** | −0.128*** | 0.095** | 1.000 | |||

| 8. AE | −0.117*** | −0.153*** | −0.115*** | −0.025 | 0.046 | 0.303*** | 0.001 | 1.000 | ||

| 9. DTM | 0.385*** | 0.320*** | −0.760*** | 0.545*** | 0.462*** | 0.027 | −0.335*** | 0.069* | 1.000 | |

| 10. MDL | 0.130*** | 0.131*** | −0.210*** | 0.190*** | 0.329*** | 0.237*** | −0.155*** | 0.245*** | 0.296*** | 1.000 |

| Criterion | Model 1: Market Power |

Model 2: Efficiency | Threshold / Cut-off | Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit Indices | ||||

| APC | 0.232 (P<0.001) | 0.153 (P<0.001) | P < 0.05 | Significant |

| ARS | 0.561 (P<0.001) | 0.265 (P<0.001) | P < 0.05 | Significant |

| AARS | 0.558 (P<0.001) | 0.259 (P<0.001) | P < 0.05 | Significant |

| AVIF | 1.734 | 1.581 | ≤3.3 (Ideal) | Ideal |

| AFVIF | 2.855 | 1.846 | ≤3.3 (Ideal) | Robust |

| Tenenhaus GoF | 0.749 | 0.515 | ≥0.36 (Large) | Large Fit |

| SPR | 0.889 | 0.864 | ≥0.700, Ideal = 1.000 | Acceptable |

| RSCR | 0.980 | 0.985 | ≥0.900, Ideal = 1.000 | Ideal |

| SSR | 1.000 | 0.864 | ≥0.700 | Acceptable |

| R-Squared (R2) | Kock and Lynn (2012) | |||

| LI | 0.668 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Moderate | |

| TE | 0.248 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Weak | |

| SE | 0.526 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Moderate | |

| AE | 0.109 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Weak | |

| Adj. R-Squared | Kock and Lynn (2012) | |||

| LI | 0.664 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Moderate | |

| TE | 0.240 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Weak | |

| SE | 0.521 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Moderate | |

| AE | 0.100 | 0.25≤Rs≤0.70 | Weak | |

| Stone-Geisser Q2 | Stone (1974) | |||

| LI | 0.561 | >0 (Relevant) | Predictive Value | |

| TE | 0.224 | >0 (Relevant) | Predictive Value | |

| SE | 0.511 | >0 (Relevant) | Predictive Value | |

| AE | 0.118 | >0 (Relevant) | Predictive Value |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | Coeff (β) | P-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | ||||

| H1 | Business Model (NNIN) → Market Power (LI) |

0.356 | < 0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | Stability (Z-Score) → Market Power (LI) |

0.243 | < 0.001 | Supported |

| Mediation Effect | ||||

| H5 | Z-Score → Governance (CGQ) → Market Power (LI) | 0.179 | < 0.001 | Supported (Partial) |

| Moderation Effects | ||||

| H6 | NPL × Z-Score → Market Power | −0.007 | 0.425 | Not Supported |

| H7 | Complexity Index (CI) × Z-Score → Market Power (LI) | −0.243 | < 0.001 | Supported |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Bank Size → LI | 0.195 | < 0.001 | Significant (+) | |

| Financial Leverage → LI | −0.010 | 0.399 | Insignificant | |

| RMQ → LI | −0.091 | 0.008 | Significant (−) |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | Coeff (β) | P-Value | Result |

| Direct Effects | ||||

| H3a | Business Model (NNIN) → TE | −0.142 | < 0.001 | Not Supported |

| H3b | Business Model (NNIN) → SE | −0.285 | < 0.001 | Not Supported |

| H3c | Business Model (NNIN) → AE | −0.181 | < 0.001 | Not Supported |

| H4a | Stability (Z-Score) → TE | −0.123 | < 0.001 | Not Supported |

| H4b | Stability (Z-Score) → SE | −0.016 | 0.333 | Not Supported |

| H4c | Stability (Z-Score) → AE | −0.176 | < 0.001 | Not Supported |

| Mediation Effect | ||||

| H8a | NNIN → DTM → TE | 0.072 | 0.004 | Supported (Partial) |

| H8b | NNIN → DTM → SE | 0.012 | 0.330 | Not Supported |

| H8c | NNIN → DTM → AE | 0.036 | 0.093 | Not Supported |

| Moderation Effects | ||||

| H9a | MDL × NNIN → TE | 0.176 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H9b | MDL × NNIN → SE | −0.006 | 0.440 | Not Supported |

| H9c | MDL × NNIN → AE | 0.088 | 0.011 | Supported |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Bank Size (Log Asset) → TE | −0.024 | 0.265 | Insignificant | |

| Bank Size (Log Asset) → SE | −0.524 | <0.001 | Significant (−) | |

| Bank Size (Log Asset) → AE | 0.039 | 0.157 | Insignificant | |

| Financial Leverage → TE | −0.422 | <0.001 | Significant (−) | |

| Financial Leverage → SE | 0.045 | 0.118 | Insignificant | |

| Financial Leverage → AE | −0.078 | 0.020 | Significant (−) | |

| Risk Mgmt (RMQ) → TE | −0.237 | <0.001 | Significant (−) | |

| Risk Mgmt (RMQ) → SE | 0.004 | 0.462 | Insignificant | |

| Risk Mgmt (RMQ) → AE | 0.101 | 0.004 | Significant (−) |

| Hypothesis. | Path Relationship | ASEAN (β) | MENA (β) | Abs. Different (β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | ||||

| H1 | Business Model (NNIN) → LI | 0.227 | 0.304 | 0.076 |

| H2 | Stability (Z-Score) → LI | −0.119 | 0.442 | 0.561** |

| H3a | Business Model (NNIN) → TE | 0.023 | −0.075 | 0.098 |

| H3b | Business Model (NNIN) → SE | −0.243 | 0.174 | 0.417** |

| H3c | Business Model (NNIN) → AE | 0.037 | −0.155 | 0.192** |

| H4a | Stability (Z-Score) → TE | −0.114 | 0.035 | 0.149* |

| H4b | Stability (Z-Score) → SE | −0.064 | 0.087 | 0.152* |

| H4c | Stability (Z-Score) → AE | −0.212 | −0.107 | 0.105 |

| Moderation Effects | ||||

| H6 | NPL × Z-Score → LI | −0.115 | 0.147 | 0.263** |

| H7 | CI × Z-Score → LI | −0.216 | −0.129 | 0.087 |

| H9a | MDL × NNIN → TE | 0.118 | −0.199 | 0.317** |

| H9b | MDL × NNIN → SE | −0.086 | −0.321 | 0.234** |

| H9c | MDL × NNIN → AE | 0.398 | −0.089 | 0.487** |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Bank Size → LI | 0.154 | −0.057 | 0.211** | |

| Financial Leverage → LI | −0.064 | −0.042 | 0.022 | |

| RMQ → LI | 0.098 | 0.105 | 0.007 | |

| Bank Size → TE | 0.151 | −0.130 | 0.281** | |

| Bank Size → SE | −0.748 | −0.495 | 0.253** | |

| Bank Size → AE | 0.224 | −0.015 | 0.239** | |

| Financial Leverage → TE | −0.524 | −0.265 | 0.259** | |

| Financial Leverage → SE | 0.025 | 0.013 | 0.012 | |

| Financial Leverage → AE | −0.057 | −0.027 | 0.030 | |

| RMQ → TE | −0.200 | −0.122 | 0.078 | |

| RMQ → SE | −0.015 | 0.118 | 0.133* | |

| RMQ → AE | 0.123 | 0.097 | 0.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).