1. Introduction

1.1. The Context and Relevance

At the turn of 2019 and 2020, the world faced a pandemic caused by the newly identified severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease it induces was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic and mild cases to severe respiratory failure and even death. Currently, owing to the development of effective vaccines and advances in therapeutic strategies, COVID-19 poses a much smaller threat. The disease-related mortality has significantly decreased, and the fear of the illness and its consequences within society has diminished.

Extensive studies conducted during the pandemic also demonstrated an increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders associated with infection by this virus. Notably, an elevated risk of depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, manic episodes, and broadly defined psychotic disorders was observed [

1]. However, the elevated risk of certain conditions, such as anxiety disorders, appears to be temporary and typically limited to about three months post-infection. In contrast, for others, such as psychotic disorders, the follow-up period remains insufficient, and the risk does not return to baseline levels even up to two years after COVID-19 [

2].

Dozens of reports on the association between SARS-CoV-2 and mental health emerging during the pandemic brought renewed attention to the long-known but often overlooked relationship between viral infections and psychiatric disorders.

The impact of viral infections on the development of psychiatric disorders is not a novel concept. Renowned psychiatrists, such as Emil Kraepelin and Karl Menninger, explored this issue as early as the late 19th and early 20th centuries [

3,

4,

5]. Despite the initially promising results, this topic was set aside, and psychiatric research evolved toward biological psychiatry, therapeutic methods and psychopharmacology, as well as reflections on the role of psychiatrists. In recent years, however, the focus has shifted to the development of neurobiology and to genetic, immunological, and molecular studies which led to the emergence of precision and personalized psychiatry.

The scale and nature of the COVID-19 pandemic have revived interest in how different viruses affect brain function and psychiatric outcomes. Significant advancements in knowledge and available research methods now make it possible to investigate this topic in ways that were previously unattainable, offering a new perspective and potentially establishing it as a meaningful etiopathogenic factor in mental disorders.

1.2. Mechanisms of Viral Impact on Mental Health

Studies indicate that various viruses can alter nervous system function through mechanisms such as neurotropism, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, neurotransmitter disturbances, virus–host protein–protein interactions and microbiota dysbiosis [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Viruses with different modes of action, such as SARS-CoV-2, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), may affect the central nervous system (CNS) in distinct ways. Because of that, analyzing their impact could enhance our understanding of the etiology of psychiatric disorders. Below, we present a brief characterization of the viruses analyzed in the present study:

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the

Coronaviridae family. This virus predominantly causes an acute type of infection, and transmission occurs mainly through respiratory droplets and aerosols. The infection primarily affects the respiratory system and manifests with fever, cough, loss of smell, and dyspnea. In severe cases, however, it may lead to viral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and can also directly affect other organ systems, including the circulatory, gastrointestinal, excretory, endocrine, and nervous systems [

12,

13]. SARS-CoV-2 shows tropism for pulmonary epithelial and endothelial cells. It is also believed to exhibit neuroinvasiveness and affinity for glial cells, while its neurotropism has not been conclusively confirmed in human studies [

14,

15].

HCV is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus classified within the

Flaviviridae family. It usually causes a chronic infection that follows an acute phase, which is often asymptomatic or mild. Transmission occurs via the parenteral route through infected blood. This virus infects hepatocytes and leads to chronic inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, it is not directly hepatotoxic and most of the liver damage results from a cell-mediated immune reaction against infected liver cells. HCV may also cause extrahepatic manifestations, including metabolic, cardiovascular, autoimmune, renal, thyroid, and pulmonary disorders [

16]. Neuropsychiatric symptoms may include depression and cognitive impairment. The neuroinvasiveness of HCV remains a matter of debate, although some reports suggest that it may replicate within brain microvascular endothelial cells, astrocytes, and microglia [

17,

18].

TBEV, similarly to the previous virus, is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the

Flaviviridae family. It usually causes acute infection and is transmitted through the bite of infected ticks. The clinical course often begins with flu-like symptoms lasting up to seven days, followed by a short remission period of about one week. After this interval, the second phase develops and it is characterized by meningitis, encephalitis, or meningoencephalomyelitis. Symptoms of meningitis are present in most patients and include high fever, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Encephalitic manifestations may involve impaired consciousness, personality changes, behavioral disturbances, cognitive dysfunction and tremor of the extremities. In some cases, delirium and psychosis may also occur. Meningoencephalomyelitic forms are characterized by flaccid pareses. TBEV displays marked neurotropism, infecting neurons and glial cells, which may result in lasting neurological and psychiatric sequelae [

19,

20].

Viral infections may lead to psychiatric disturbances through several key mechanisms:

Neurotropism and neuroinvasiveness: Some viruses can directly infect CNS cells or cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). TBEV has confirmed neurotropic properties [

20] and SARS-CoV-2 exhibits partial neurotropism [

14,

15] as well as neuroinvasive capabilities [

9]. Evidence of HCV neuroinvasiveness remains limited [

17,

18].

Immune activation, cytokine dysregulation and neurovirulence: Viral infections can trigger excessive immune responses with elevated cytokine levels, e.g., interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), interleukin-10 (IL-10), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferons [

6]. Such immune activation may disrupt neurotransmitter function and contribute to psychiatric symptoms [

21]. These cytokines may also compromise the BBB and promote neuroinflammation. Viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 and HCV additionally can induce immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, hypoxia, prothrombotic abilities and metabolic disturbances. Together, these mechanisms may cause CNS pathology without direct viral invasion, which is referred to as neurovirulence [

9,

17,

18,

22,

23,

24].

HPA axis disruption: Chronic viral-induced stress may dysregulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing cortisol levels and susceptibility to anxiety, depression, and psychosis [

25,

26,

27].

Neurotransmitter imbalance: Inflammatory cytokines and viral components can alter serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), and glutamate (Glu) pathways [

21,

28]. Viral infections also activate the kynurenine pathway, resulting in increased neurotoxic metabolites such as quinolinic acid, which is linked to excitotoxicity and mood disturbances [

29,

30].

Virus–host protein–protein interactions (PPIs): Viral infections can modulate host biological processes through interactions between viral and host proteins, leading to dysregulation of critical systems, including the immune response. PPIs also influence β-amyloid accumulation, reactive oxygen species production, neuronal death, gliogenesis, and autophagy. This type of dysregulation may contribute to the development of complex diseases, including neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders [

11,

31].

Microbiota dysbiosis: The bidirectional cross-talk between commensal microbiota and the CNS, known as the gut-brain axis, plays a crucial role in regulating immune, neuroendocrine and inflammatory pathways. Through the activity of the gut microbiota, neurotransmitters such as Glu, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), DA, norepinephrine (NE), and 5-HT are produced [

32]. Dysbiosis and gastrointestinal inflammation, accompanied by increased intestinal and BBB permeability, allow cytokines and neurotransmitters released in the gut to enter the CNS, leading to its dysfunction and increasing the risk of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety [

10,

33].

1.3. Aim and Hypotheses

In continuity with our previous publications, this study focuses on the impact of virus-induced inflammation and cytokine dysregulation on the development of psychiatric disorders. It aims to assess the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and disorders following infection with SARS-CoV-2, HCV, and TBEV, and to examine associated inflammatory biomarkers.

Hypotheses:

This hypothesis was formulated based on reports on 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, among whom 24% were diagnosed with a mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorder (with 8.6% being first-ever diagnoses) [

34]. By contrast, among patients after tick-borne encephalitis, only 1.5% received a psychiatric diagnosis one month after discharge [

35]. In the case of HCV, some studies indicate that more than 30% of patients exhibit mental disorders (depression and anxiety) prior to antiviral treatment [

36]. We also considered the inflammatory theory of mental disorders [

37,

38,

39] and the fact that SARS-CoV-2 elicits a cytokine storm that may substantially contribute to the development of psychiatric disorders, potentially translating into a higher risk compared with other viral infections [

40,

41].

- 2.

Each virus induces a distinct cytokine profile, potentially serving as a biomarker for psychiatric outcomes.

This hypothesis arose from our previous observations and studies, in which we noted that the cytokine dysregulation profile we established across multiple psychiatric conditions, although generally similar, often differs by changes in one or more cytokines. A comparable pattern is seen in viral diseases [

6]. Given the subtle and complex influence of the immune system on psychiatric disorders, such small differences could, in theory, determine disease development. These differences, however, required testing under conditions identical for every participant.

- 3.

The degree of CNS involvement during infection varies depending on the type of virus (neurotropism, neuroinvasiveness, neurovirulence) and may influence psychiatric outcomes, but is not their primary determinant.

The hypothesis is also grounded in our earlier observation that some viruses not generally considered neurotropic (e.g., Human Immunodeficiency Virus – HIV, or H1N1 influenza) are more frequently linked to psychiatric complications than certain viruses with strong neurotropism, such as Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) [

6]. This would suggest that affinity for neural cells may not be as important factor as it might seem.

The findings of this study may contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of mental disorders and support the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The study was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry, University Clinical Hospital in Białystok, between February and December 2023. Patients hospitalized due to SARS-CoV-2, TBEV, or HCV infections were recruited from local infectious disease wards. Controls were healthy volunteers from hospital staff and the Healthy Senior University Program. Initially, 45 patients and 32 controls were enrolled; 8 patients were lost to follow-up, yielding a final sample of 37 patients (14 women, 23 men) and 32 controls (17 women, 15 men). The study cohort comprised 17 patients with COVID-19, 7 with HCV, and 13 with TBEV. All HCV patients were hospitalized for the first time, however, the duration of infection remained unknown. All participants were of Polish nationality and Caucasian ethnicity.

Inclusion criteria: age 18–90 years, current hospitalization due to one of the infections (patients), or no infection within the past year (controls), and mental capacity to complete psychiatric assessments.

Exclusion criteria: severe systemic illness, active cancer, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, pregnancy/lactation, or lack of informed consent.

2.2. Study Design

This was a 12-month prospective cohort study with two assessment points. At Stage 1 (during hospitalization), participants underwent psychiatric evaluation, mental state examination, and blood sampling. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was administered. Control participants followed an identical protocol. ICD-10 diagnostic criteria were used throughout. At Stage 2 (after 12 months), follow-up interviews were conducted by phone, including HADS and an updated clinical interview. Psychiatric diagnoses were revised or confirmed by a senior psychiatrist

2.3. Blood Collection and Sample Handling

During Stage 1, fasting venous blood (7.5 ml) was collected using S-Monovette® Serum CAT tubes. Samples were left at room temperature for 45 minutes, centrifuged (5 °C, 2000 × g, 10 min), and serum was transferred to 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes, then stored at −80 °C for up to 12 months.

2.4. Psychiatric Assessment

Participants completed a detailed interview covering demographics, comorbidities, medications, substance use, prior infections, psychiatric history, and vaccination status. In the study group, 12 participants (32,4%) had a prior psychiatric diagnosis - 3 with anxiety disorders, 3 with mood disorders, and 4 with substance use disorders; 2 participants were unable to confirm the exact diagnosis. In the control group, 13 participants (40,6%) had a prior psychiatric diagnosis- 6 with mood disorders and 5 with anxiety disorders; 1 participant was unable to confirm the exact diagnosis. Among the 25 individuals with a prior psychiatric diagnosis, only 2 (both with substance use disorder) had received treatment for it within the past 5 years. Current psychiatric symptoms (affective, anxiety, psychotic, obsessive-compulsive, cognitive, and sleep-related) were assessed based on ICD-10. Diagnoses were confirmed by an experienced psychiatrist (N.W.) in both study stages.

2.5. Scales

HADS was used at both stages to assess anxiety and depression (most common psychiatric disorders related to viral infections). The scale includes 14 items across two subscales (max score 21 each). Scores >7 indicated clinical symptoms. At follow-up, HADS was administered via phone. The tool was selected for its brevity and diagnostic sensitivity [

42,

43].

2.6. Cytokine and Chemokine Measurement

After collection, all serum samples were thawed and analyzed simultaneously using the Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine Screening Panel, 48-Plex (#12007283). This multiplex immunoassay quantifies cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors using fluorescently labeled magnetic beads. Assays were conducted per manufacturer protocol on the Bio-Plex 200 System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA). The full list of measured cytokines and chemokines is provided in the appendix.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 30. Descriptive statistics and the Shapiro–Wilk test were used to evaluate distribution. Group comparisons were made with chi-square tests, Kruskal–Wallis tests, and Student’s t-tests, as appropriate. Hierarchical logistic regression estimated event probabilities. Significance was set at α = 0.05; effect sizes were interpreted per Cohen’s guidelines [

44].

Two approaches were applied to estimate the required sample size for this study: one for between-group comparisons and another for regression models.

For between-group comparisons, a priori power analysis conducted in G*Power indicated that, assuming a moderate effect size, a Type I error rate (α) of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.95, the required sample size would be N = 280. For a conventional power level of 0.80, the required sample size would decrease to N = 180.

For regression analyses, a widely accepted rule of thumb was applied, recommending a minimum of 50 observations plus an additional 15 observations for each included predictor. Accordingly, a model with one predictor would require at least N = 50 participants, two predictors N = 65, and three predictors N = 80. Furthermore, due to the relatively large number of predictors compared to the sample size, regression analyses were performed using the backward elimination method to obtain the best-fitting model while excluding variables with low predictive power.

As the target sample size was not reached, the analyses were considered exploratory in nature and aimed primarily at generating hypotheses for future research.

3. Results

3.1. Group Characteristics

No significant differences were found between groups in sex, vaccination status, or psychiatric history. However, participants with TBEV were significantly younger than controls and COVID-19 patients. Tobacco use was highest in the HCV group. COVID-19 patients more frequently reported heart disease and cancer, while hyperlipidemia was more common in controls [Tables A1–A4 in

Supplementary Materials].

3.2. Descriptive Statistics for Quantitative Variables

Most variables deviated from normal distribution, though skewness was minor for the majority. Parametric tests were applied, except for highly skewed biomarkers such as interferon alpha-2 (IFN-α2), interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-6, IL-8, and interleukin-12 subunit p40 (IL-12(p40)), for which non-parametric tests were used [Tables A5 and A6 in

Supplementary Materials].

3.3. Comparison of Psychiatric Symptoms

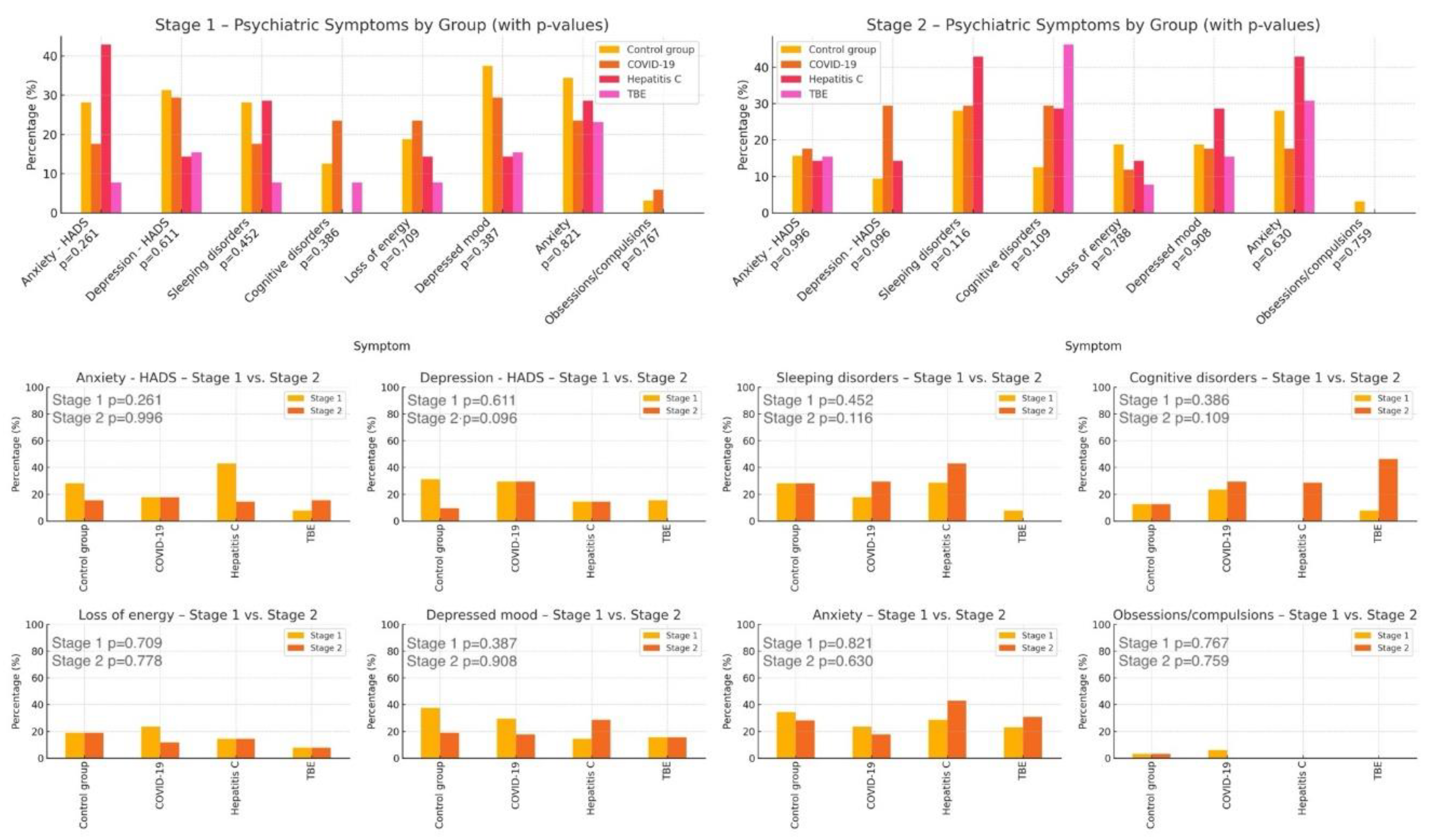

No significant differences in psychiatric symptom prevalence were found across patient groups at either time point [Tables A7 and A8 in

Supplementary Materials]. Additionally, no differences were observed between the groups in psychiatric symptom changes over the course of the study [Table A9 in

Supplementary Materials].

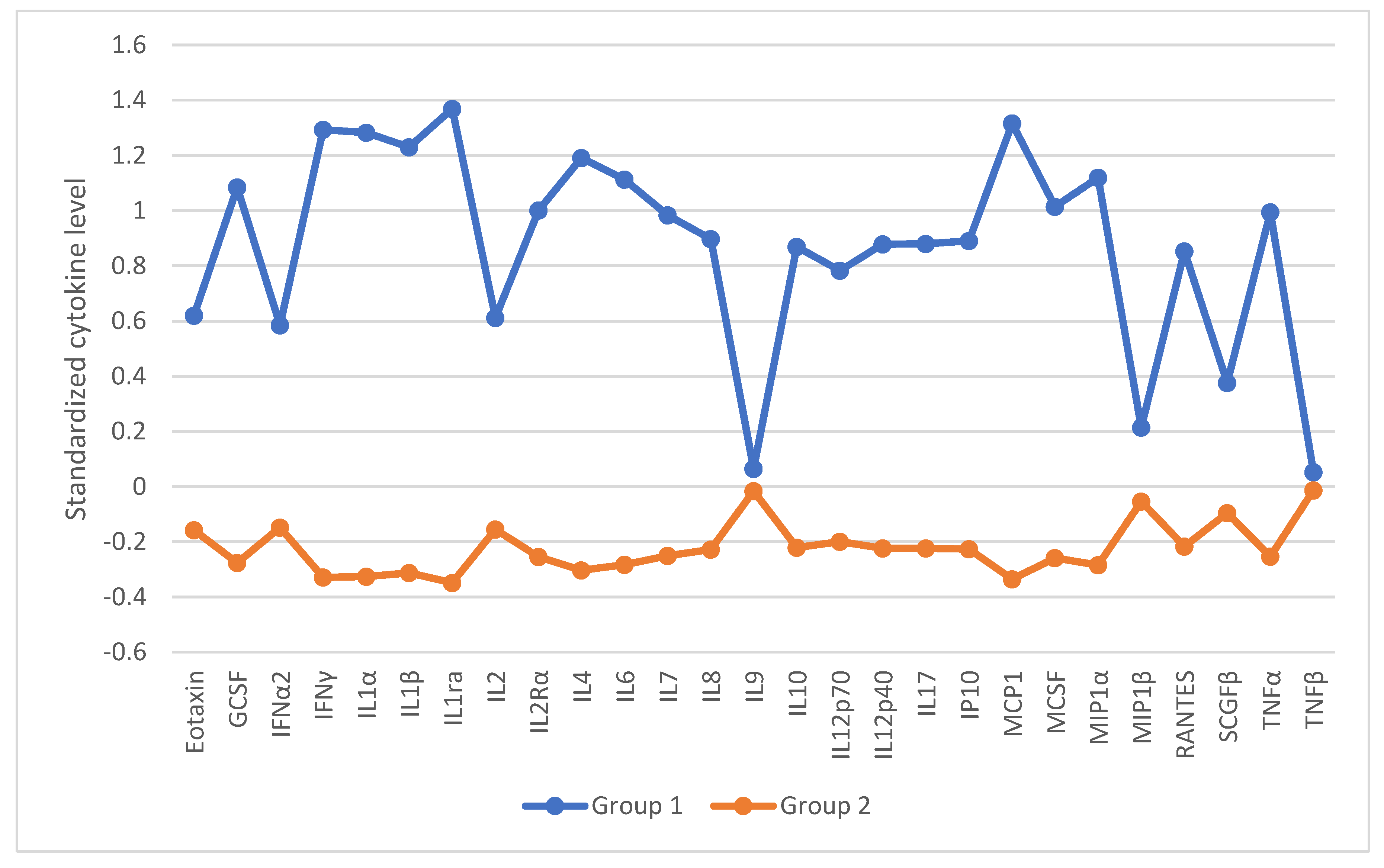

These findings suggest that one year after infection with a given virus, patients are not at greater risk of developing or changing the severity of the assessed psychiatric symptoms compared to individuals in the control group. A visual representation of these results is provided in

Figure 1.

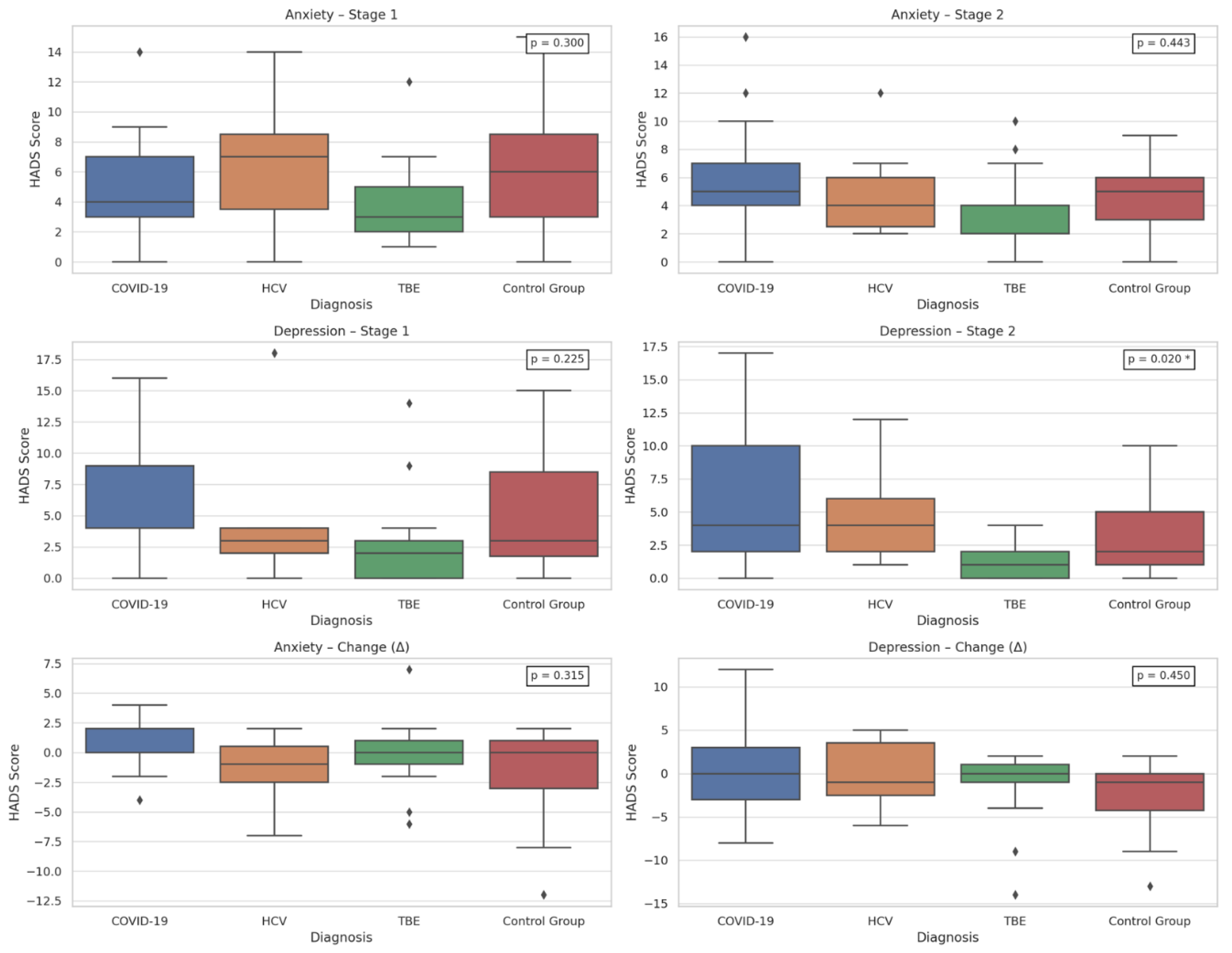

Additionally, the type of viral infection was significantly associated only with depression severity at Stage 2, as assessed by the HADS (p = 0.020). Post hoc analysis showed higher depression levels in COVID-19 patients compared to those with TBEV (p = 0.022) [Tables A10–A12 in

Supplementary Materials]. Graphical representation is provided in

Figure 2. To further clarify this result,

Table 1 presents the full post hoc Dunn test results.

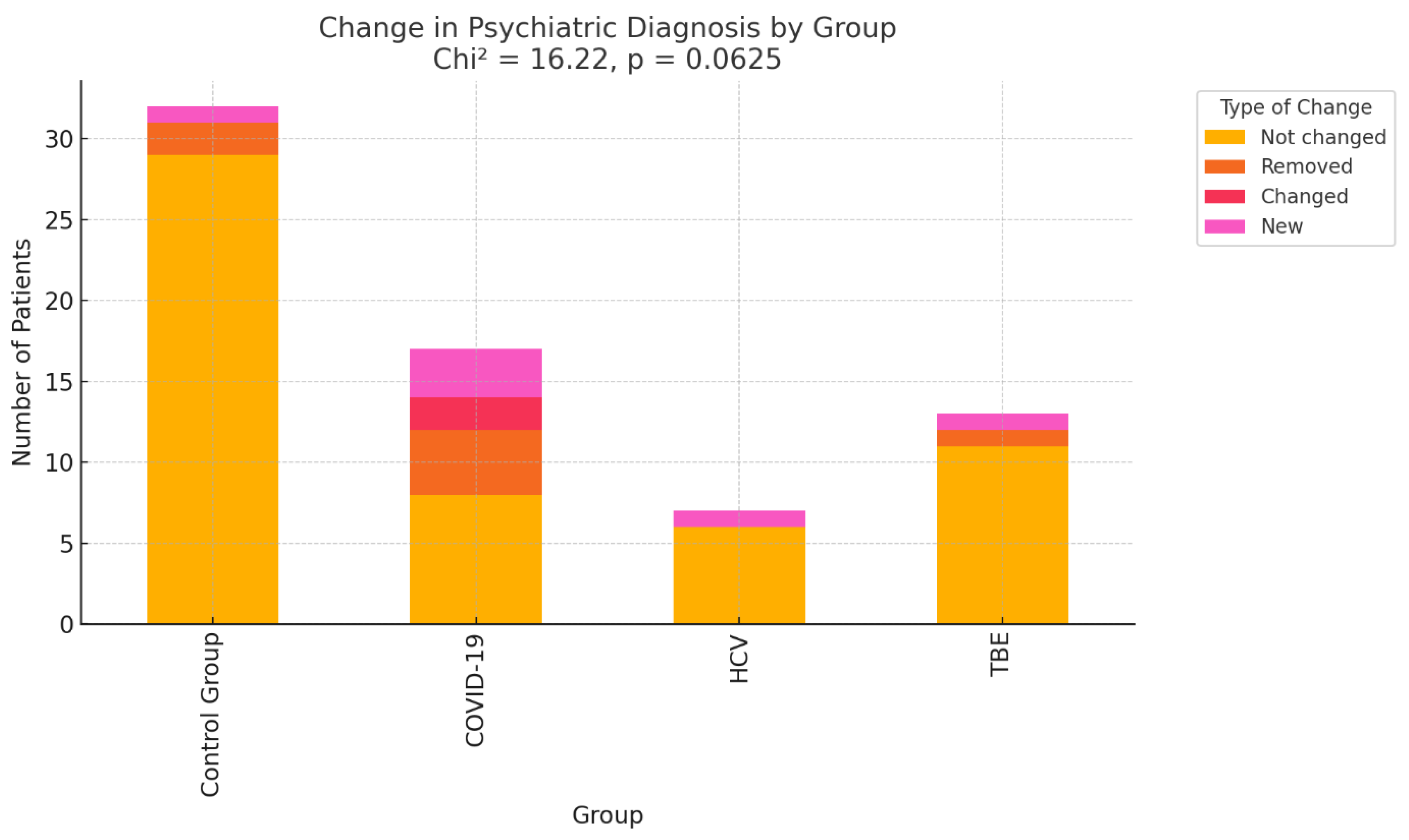

3.4. Comparison of Psychiatric Diagnoses

Adjustment disorder, depressive episodes, and mixed anxiety-depression were most common in both stages of the study [Tables A13 and A14 in Supplementary Materials]. No statistically significant differences in diagnosis progression were observed across infection groups [Table A15 in

Supplementary Materials]. The results are illustrated graphically in

Figure 3.

However, a non-significant trend suggested more frequent changes in psychiatric diagnoses in the COVID-19 group (p = 0.0625, Cramér’s V = 0.28). This trend may indicate that COVID-19 infection is associated with greater variability or progression in mental health status.

The type of psychoactive substances used by patients did not significantly influence the likelihood of a diagnostic change [Table A16 in

Supplementary Materials]. However, patients with comorbid cancer or asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were significantly more likely to experience diagnostic changes [Table A17 in

Supplementary Materials].

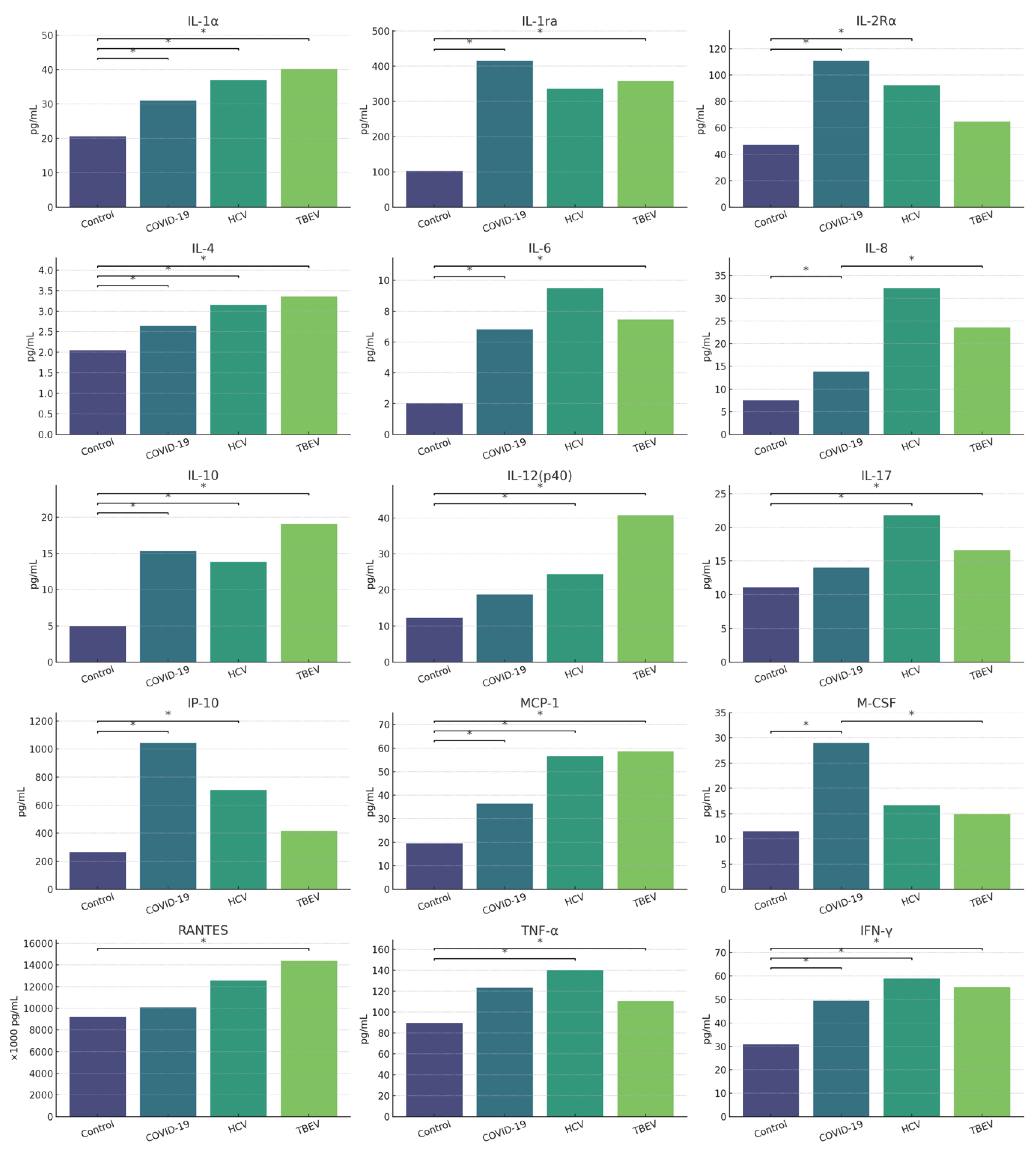

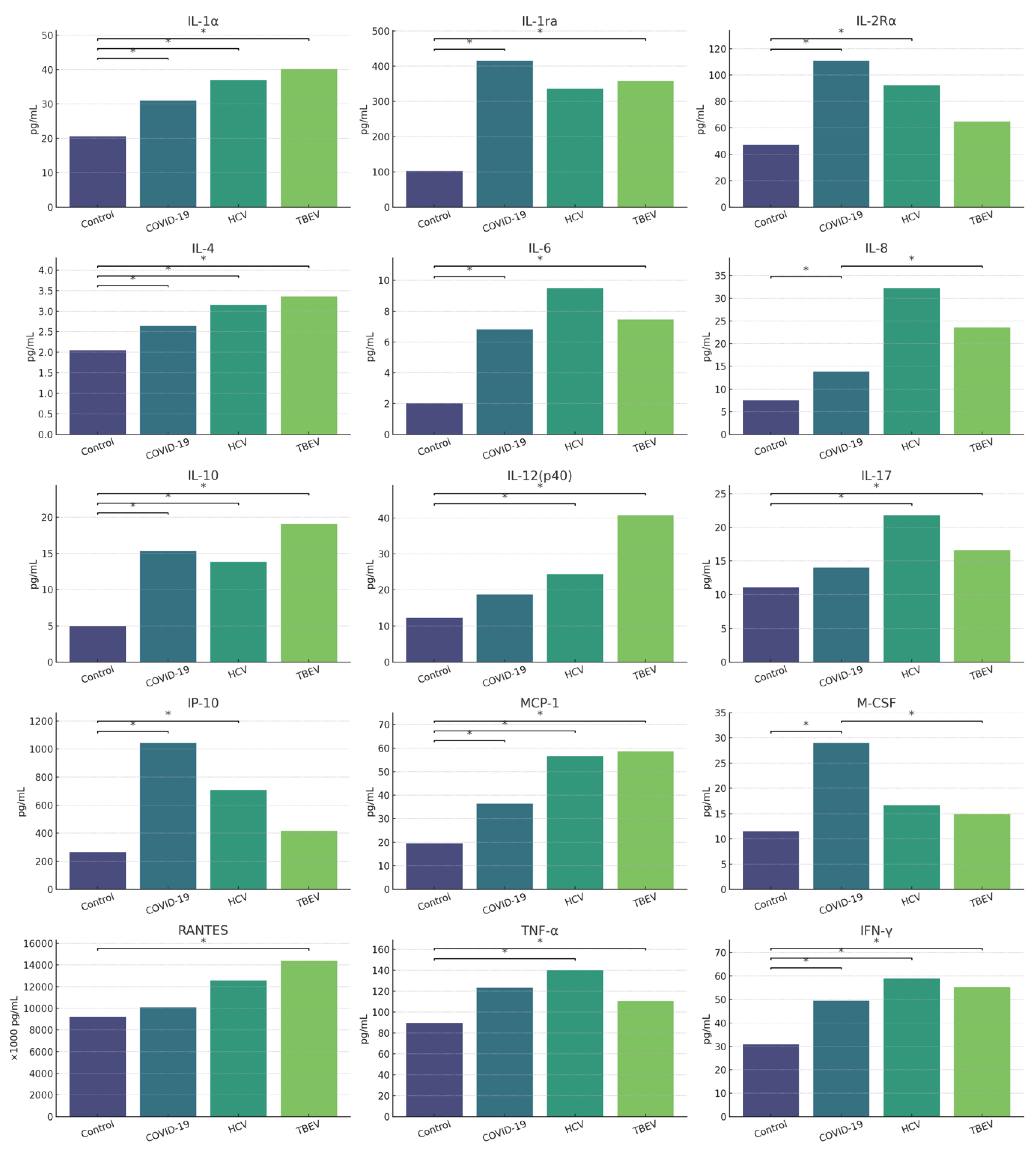

3.5. Comparison of Cytokine Dysregulation and Their Associations to Psychiatric Symptoms

After excluding a direct link between virus type and psychiatric disorders, the analysis focused on associations between viral infection and cytokine levels measured at Stage 1, as well as their relation to psychiatric outcomes. The results are presented in

Table 2.

The analysis revealed statistically significant differences between groups in the levels of IFN-α2, IFN-γ, interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α), interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), interleukin-2 receptor alpha (IL-2Rα), interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-6, interleukin-7 (IL-7), IL-8, IL-10, IL-12(p40), interleukin-17 (IL-17), Interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10), Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1), Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF), Regulated upon Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted (RANTES), and TNF-α. Controls generally showed lower levels than infected groups, particularly those with COVID-19 and TBEV. No statistically significant differences were observed for IFN-α2 and IL-7 after correction for multiple comparisons. Full results are presented in [Tables A18A–A18F in

Supplementary Materials]. Graphically they are illustrated in

Figure 4.

Based on the statistically significant differences in cytokine levels, dominant cytokine profiles associated with each viral diagnosis were constructed and are summarized in

Table 3.

Next, cytokines predicting psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms were identified. To this end, hierarchical logistic regression models were constructed. Due to multicollinearity, variables with a variance inflation factor (VIF) > 5.00 were excluded from further analyses. Furthermore, given the large number of predictors relative to the sample size, the analysis employed backward elimination to obtain a best-fitting model while excluding variables with low predictive power.

In Stage 1 of the study, the significant predictors of psychiatric diagnosis included IFN-α2, IL-2Rα, IL-17, and IP-10. In Stage 1, higher levels of IFN-α2, IL-17, and IP-10 were linked to reduced risk of diagnosis, by 70%, 21%, and less than 1% respectively, while IL-2Rα was associated with 6% increase in risk of diagnosis. In Stage 2, only RANTES predicted a slight increase in risk - by less than 1%. Cytokines significantly predicting specific symptoms across stages are summarized in [Table A19 in

Supplementary Materials].

With regard to specific symptoms,

Table 4 lists cytokines that significantly predicted symptom probability at both stages. Detailed statistics are in [Tables A20 and A21 in

Supplementary Materials].

Only a few cytokines, such as IL-12(p40), IL-2Rα, and RANTES, were significant predictors at both stages. Others, like IL-2, SCGF-β, IL-8, MIP-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α were predictive only at Stage 2. Cytokines like IL-7, IL-9, IL-17, IP-10, and IL-10 were predictive at Stage 1 but lost significance over time.

An additional analysis examined cytokine effects on anxiety and depression severity (HADS, continuous). Hierarchical logistic regression models were used again. Predictors with a VIF > 5 were excluded to mitigate multicollinearity, and backward elimination was applied to obtain the best-fitting model. After excluding highly collinear markers, IL-1β predicted anxiety at Stage 1 (weak effect). Depression severity was linked to IL-10 (positive) and RANTES (negative) at Stage 1. At Stage 2, depression severity was positively linked to increasing concentrations of IP-10 and SCGF-β. Full data are presented in [Tables A22 and A23 in

Supplementary Materials].

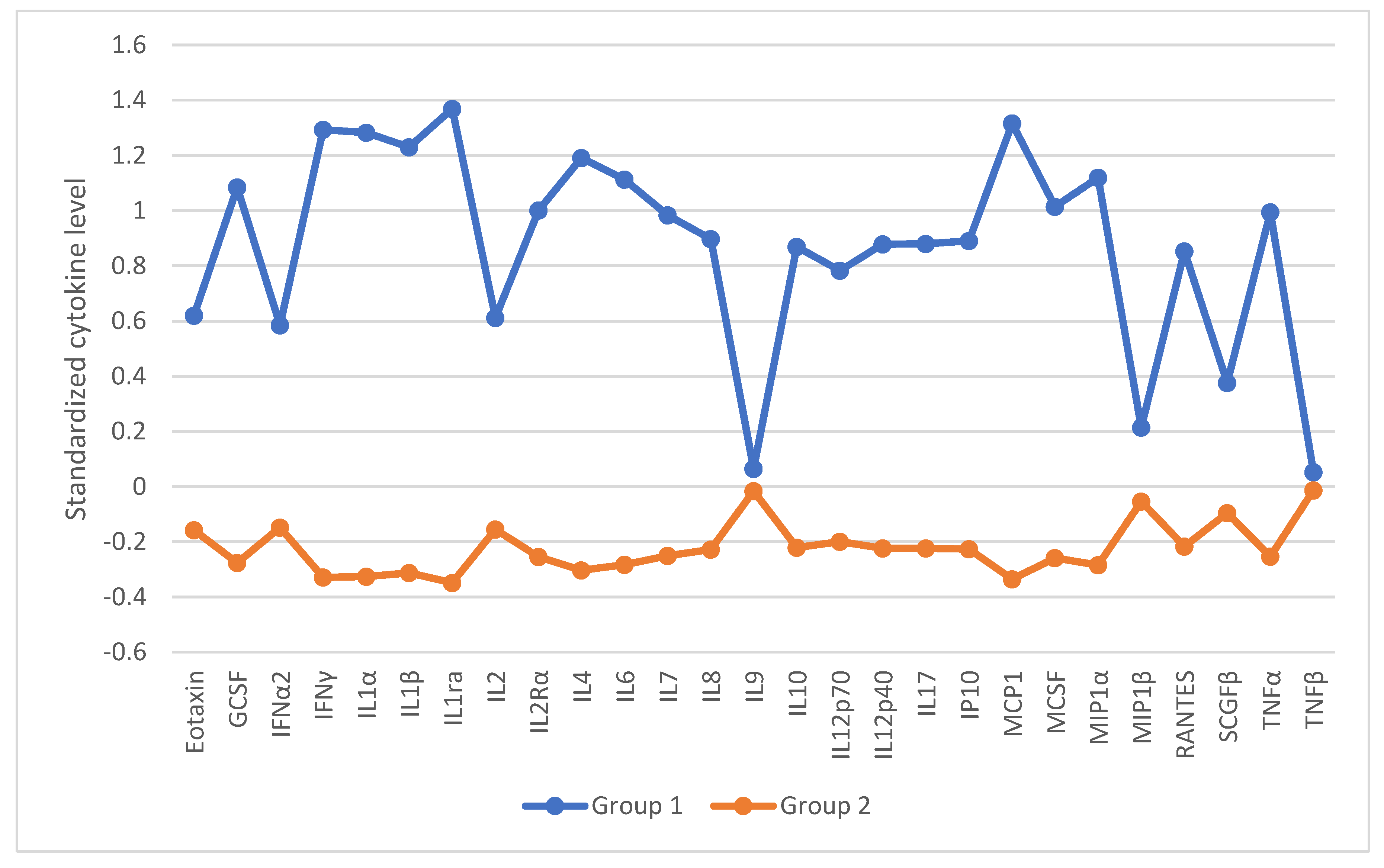

In the final analysis of cytokine dysregulations, patients were clustered by cytokine profiles using two-step cluster analysis, followed by a k-means cluster analysis to validate the results. Prior to clustering, cytokine levels were standardized. In result, two distinct clusters emerged, differing significantly in most cytokine levels. Cluster 1 (n=14) showed higher cytokine levels than Cluster 2 (n=55). The cytokine profiles of the identified clusters are illustrated in

Figure 5. Higher cytokine profiles were linked to COVID-19 or TBEV, while lower profiles were more common in controls and HCV cases.

No significant cluster differences were found in sleep, cognition, energy, anxiety, or depression symptoms at either stage of the study. Similarly, HADS-measured anxiety and depression severity did not differ between clusters. Full results are presented in [Tables A24–A26 in

Supplementary Materials].

3.6. Impact of Prior COVID-19 Infection on the Course of Psychiatric Symptoms and Diagnoses

The final analysis assessed whether prior COVID-19 infection affected psychiatric outcomes. No significant group differences were found in diagnostic changes, symptom presence, or HADS scores at either stage. However, those with a COVID-19 history showed a significantly greater reduction in depression severity over time. Results in [Tables A27–A33 in

Supplementary Materials].

4. Discussion

This study aimed to compare the prevalence of psychiatric disorders after SARS-CoV-2, HCV, and TBEV infections and identify related cytokine biomarkers. It was hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 posed the greatest psychiatric risk among analyzed viruses and that their distinct cytokine profiles might predict outcomes. Additionally, it was assumed that the neuroinfectious properties of the studied viruses differ, and that these differences influence the frequency and severity of neuropsychiatric manifestations, however, these properties are unlikely to be their primary determinant.

Demographic data showed TBEV patients were significantly younger, likely due to greater tick exposure in active individuals, while COVID-19 patients more often had cardiovascular disease and cancer - aligning with known risk patterns in older, comorbid populations [

45,

46].

Unexpectedly, no significant group differences in psychiatric symptom frequency were found at either study stage. The only exception was greater depressive symptom severity after COVID-19 compared to TBEV in Stage 2. This may reflect the more acute and self-limiting nature of TBEV - potentially promoting a faster neuroimmune return to homeostasis [

47], its lower psychosocial burden, and the younger, healthier profile of TBEV patients. In contrast, COVID-19 is associated with prolonged, systemic inflammation as well as substantial psychological stress and health-related anxiety [

29,

48].

No significant group differences were found in diagnostic changes over one year, though COVID-19 patients showed a trend toward greater mental health variability. Early post-COVID symptoms often appear within three months, after which the risk tends to return to population baseline levels. In those without improvement by six months, symptoms may recur or worsen even 2–3 years post-COVID-19, regardless of initial illness severity [

2,

49]. This pattern of early symptom development may ultimately influence the clinical presentation and contribute to diagnostic changes observed at the one-year mark. However, cancer, more common in the COVID-19 group, was linked to greater risk of diagnostic change which also may affect observed variability of mental health in COVID-19 group. These trends require confirmation in larger samples.

Analysis of all collected data indicates that the type of virus, regardless of its neuroinfectious properties, did not significantly determine the frequency of psychiatric symptoms or diagnoses. Consequently, the first research hypothesis was not supported, whereas the third research hypothesis was sustained. SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders compared to HCV or TBEV infections, suggesting that the decisive factor may lie not in the intrinsic properties of the virus itself, but rather in its impact on the host’s immune response.

This raises a legitimate question: could the intensity of the inflammatory response, regardless of the specific pathogen, be the key factor contributing to the development of psychiatric disorders? Although the control group exhibited the lowest levels of inflammatory markers, it did not show a lower frequency of psychiatric symptoms compared to the infected groups. This finding challenges the notion of a straightforward relationship between inflammation severity and psychiatric risk.

Regarding the second research hypothesis: each virus showed a distinct cytokine profile - COVID-19 with a systemic cytokine storm, HCV with chronic Th1/Th17 activation, and TBEV with neuroinflammation involving CNS chemotaxis (e.g., RANTES). However, no profile was consistently linked to specific psychiatric symptoms, contradicting the inflammatory theory of depression, which posits that activation of Th1 and Th17 axes correlates with increased affective symptom severity [

37], as well as other prior findings on cytokine elevation in psychiatric disorders [

6]

This suggests inflammation alone may not cause psychiatric disorders; additional factors, e.g., genetic vulnerability, trauma, stress, substance use or personality disorders, may be needed for symptoms to emerge. Both biological and environmental risks likely play a role in translation of inflammatory response to clinically relevant psychiatric symptoms [

50,

51].

Despite differences in the dominant cytokines i.e., ‘cytokine profiles’ observed across various viral infections, these differences did not influence the presence or absence of specific psychiatric diagnoses among infected patients. Therefore, we were unable to confirm our second research hypothesis. Nevertheless, certain cytokines, when considered independently of the type of viral infection and psychiatric diagnosis, were associated with specific psychiatric symptoms. However, as cytokines were measured only once during the study, this limits conclusions about immune dynamics and its influence on psychiatric disorders. Despite aiming to test the predictive value of a single measurement, this remains a key study limitation requiring future longitudinal research.

The following section discusses the observed associations of cytokines and psychiatric symptoms by cytokine function - from pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 mediators to immunoregulatory factors and CNS-directed chemokines.

4.1. Th1 Pro-inflammatory Cytokines

IL-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that disrupts the BBB and neurotransmission. Its excess has been linked to impaired synaptic plasticity, reduced neurogenesis, exacerbation of depressive symptoms, and activation of the HPA axis. In neurons and astrocytes, IL-1β disrupts glutamatergic homeostasis, enhances excitotoxicity, and may promote oxidative stress. Numerous studies indicate that elevated IL-1β levels correlate with reduced hippocampal volume, executive function deficits, and increased vulnerability to neurodegeneration [

52,

53,

54]. In Stage 2 of our study, IL-1β predicted nearly double the risk of cognitive impairment. Highest levels, although statistically insignificant, were seen in the HCV group, which also had more cognitive deficits. The results support previous findings, that higher IL-1β levels during acute infection may raise the risk of long-term cognitive impairment, though environmental influences can’t be excluded. The lack of strong effect between groups may stem from serum IL-1β not reflecting CNS levels or its effects being modulated by regulatory cytokines like IL-10 or IL-1ra.

TNF-α is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by immune and glial cells. It signals through two receptors: TNFR1, broadly expressed and linked to inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal damage; and TNFR2, found mainly on immune cells and neurons, promoting neuroprotection and reducing microglial toxicity. Its effects depend on receptor expression and activation [

55,

56,

57,

58]. In acute inflammation, TNF-α may be neuroprotective by stabilizing the BBB, modulating excitotoxicity, and promoting trophic factors release. Chronically elevated TNF-α, however, disrupts synaptic balance, activates microglia, and stimulates the kynurenine pathway - processes linked to depression and cognitive decline [

57,

58]. In our study, TNF-α levels were significantly higher in the TBEV and HCV groups, which also showed the largest increase in cognitive impairments. Paradoxically, higher TNF-α levels at Stage 1 were associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of cognitive impairment at Stage 2, possibly indicating early TNFR2-mediated neuroprotection. Groups with the highest TNF-α initially had the fewest deficits, suggesting a well-regulated inflammatory response. A decline in TNF-α over time may have allowed other cytokines, like IL-8 or IL-1β, to exert greater effects on cognition.

4.2. Th17/Neuroinflammatory Cytokines with an Autoimmune Component

IL-17 showed a protective effect in the first stage of the study. Its increase was linked to a 76% lower risk of cognitive impairment and 12% less anxiety. Highest IL-17 levels were found in TBEV and HCV patients, correlating with fewer cognitive deficits. While typically associated with CNS damage [

59,

60], emerging evidence suggests IL-17 may have neuroprotective effects, possibly depending on its concentration and immune context. During infection, it may limit neuronal apoptosis and exert the protective effects observed in our cohort, suggesting that the dominant function of IL-17 depends on the phase and nature of the immune response [

61].

IL-12(p40) - As part of the Th1 axis, the p40 subunit has a modulatory role in both the Th1 and Th17 axes. Homodimers of p40 - (p40)

2, competitively bind to the IL-12Rβ1 receptor, blocking IL-12 and IL-23 signaling, thereby inhibiting both Th1 and Th17 pathways. Indirectly, p40 supports the differentiation of Tregs, partly through creating an environment conducive to STAT5 activation, and limits the maturation of Th17 cells by reducing STAT3 activity [

62,

63]. In our study, its levels correlated with greater depressive and anxiety symptoms at both study stages. A 1-unit increase was linked to a 5% rise in anxiety as measured by the HADS scale and 3% in subjective anxiety at Stage 1. In relation to depression, it was associated with 12% increase in depression risk as measured by the HADS scale, and 4% in subjective depression at Stage 2. Although IL-12(p40) was linked to affective symptoms, its highest levels were found in the HCV and TBEV groups, where such symptoms were less frequent than in COVID-19. This may indicate a dominance of the (p40)

2 homodimer, which blocks Th1/Th17 signaling. In COVID-19, IL-12(p40) may have served a compensatory but insufficient role. Its dual function, as proinflammatory in the IL-12(p70) heterodimer and immunoregulatory in the (p40)

2 form, could explain observed inconsistencies. The shift from anxiety-related effects in Stage 1 to depression in Stage 2 may reflect symptom evolution from acute stress to chronic mood disturbances.

4.3. Anti-Inflammatory/Immunoregulatory Cytokines

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that modulates immune responses and limits tissue damage [

64]. Its chronic reduction may lead to microglial overactivation and HPA axis dysregulation. Though often decreased in depression and anxiety, elevated IL-10 has been noted in psychosis and may reflect a compensatory anti-inflammatory response [

6,

21,

65]. In our study, higher IL-10 levels in Stage 1 were linked to reduced energy. While low IL-10 is common in anergia, its elevation during acute inflammation and viral infections may indicate activation of the CARS (Compensatory Anti-inflammatory Response Syndrome). This is an immunologic mechanism in which anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10, are produced in response to strong immune system activation. While this response is generally protective, it can also contribute to fatigue and low mood [

66]. In Stage 2, higher IL-10 levels during acute infection predicted a lower risk of later sleep disturbances, suggesting a neuroprotective role in shielding sleep-regulating brain regions from proinflammatory cytokine damage [

64,

67].

SCGF-β is produced by bone marrow cells and supports hematopoiesis, tissue regeneration, and immune regulation. Though not significantly elevated in any group, its increase was linked to a 1% reduction in depression risk. This may reflect its ability to support immune system regeneration, suppress neuroinflammatory mechanisms within the CNS, and enhance neuroimmune balance and resilience to stressors. Lower SCGF-β levels have also been observed in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) patients with depression [

68].

4.4. Receptors and Markers of Lymphocyte Activation

sIL-2Rα is a soluble form of the alpha subunit of the interleukin-2 receptor, and marker of T-cell activation and systemic immune response. Compared to control group, sIL-2Rα was significantly elevated in the COVID-19 and HCV groups. Its increase was linked to a 5% higher risk of cognitive impairment at both study stages, which is consistent with previous reports [

69,

70,

71]. While group differences weren’t statistically significant, the COVID-19 group showed nearly double the impairment rate early on. In HCV and TBEV, rates increased over time. The lack of statistical significance may be attributed to an insufficient sample size. Alternatively, within the HCV and TBEV groups, some individuals may have had relatively lower sIL-2Rα levels, potentially reducing the overall group-level risk of cognitive impairment. Additionally, elevated levels of immunoregulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1ra, IL-10) may have mitigated the neuroinflammatory impact of sIL-2Rα. It is also important to note that patients in the TBEV and HCV groups were generally younger and had fewer comorbidities, factors that may have promoted better cognitive functioning and recovery

IL-2 supports T-cell and NK cell activity. However, at low levels, it promotes Treg development, helping suppress inflammation and maintain immune balance, potentially protecting the CNS against prolonged post-viral inflammation [

72,

73]. In our study, higher IL-2 levels predicted a lower risk of depression in Stage 2. Although not significantly elevated across groups, moderate IL-2 level increase may have immunoregulatory effects. In line with our findings, low-dose IL-2 is also being investigated experimentally as a treatment for depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [

74,

75]

IL-7 supports T and B cell survival and proliferation, and is elevated in immune dysregulation, such as HIV [

76,

77]. Though typically reduced in depression, excessive IL-7 activity may sustain chronic inflammatory responses and has been previously linked to high-risk schizophrenia, correlating with the severity of positive symptoms [

78,

79]. In our study it was linked to a 12% higher risk of depression in Stage 1. Group differences were initially significant but lost significance after correction. IL-7’s predictive value was limited over time. According to literature, its association with depressive symptoms may vary by sex and blood fraction, with opposing trends in men and women [

80].

4.5. Chemokines – Cell Migration to the CNS

RANTES is a chemokine secreted by activated T cells. It recruits immune cells to inflammation sites and activates microglia and astrocytes in the CNS [

81]. In Stage 1, its increase was linked to reduced risk of low mood (measured both by the HADS scale and subjectively) and energy loss but higher risk of cognitive impairment. In Stage 2, higher RANTES predicted a 1% increase in anxiety and cognitive disorders. RANTES levels were highest in the TBEV group, though depressive symptoms were more frequent in controls. Based on these results it is possible that RANTES has a biphasic effect, meaning that initially it may be protective, but its chronic elevation may promote low-grade CNS inflammation and prolonged immune activation, possibly leading to neurotoxicity, persistent cognitive deficits, and heightened anxiety. These results align with some of the previous findings in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and ischemic stroke [

82,

83,

84]

MIP-1α is a proinflammatory CC chemokine produced by various immune and glial cells. It modulates inflammation and acts as a chemoattractant. In our study it was linked to a 74% reduced risk of cognitive impairment in Stage 2, despite no significant group differences in its levels. Our findings stand opposite to previous studies which associate MIP-1α with cognitive decline [

85,

86], possibly due to differences in immune activation phase (acute vs. resolving), clinical context, or characteristics of the study population. In a resolving inflammatory state, MIP-1α may support neuroprotection through microglial clearance of damaged structures, promoting neuronal pathway reorganization, or contributing to the regulation of the local neuroimmune environment [

87].

IP-10 (CXCL10) is induced by IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β, and it recruits Th1 cells and NK cells. In the brain, it is produced by astrocytes and microglia [

88]. In our research it was associated with a 1% reduced risk of depression (measured by the HADS) per unit increase in Stage 1. Its levels were higher in the COVID-19 and HCV groups, though depressive symptoms were not more severe in those groups than in controls. Interestingly, more depressive symptoms were seen in controls (statistically not significant), despite lower IP-10. The literature on IP-10 and depression is inconsistent, with studies showing either elevated or unchanged IP-10 levels in individuals with depression [

88,

89]. It is possible that in our study, IP-10 reflected a well-regulated Th1 response, and the single time-point cytokine measurement did not capture the full dynamics of the immune response. Environmental and psychological factors occurring between stages may also have influenced the results. Moreover, some studies suggest a potential neuroprotective role of IP-10 during infection, which in the context of pathogen-induced psychiatric symptoms, could help reduce the risk of depression [

90].

IL-8 is a pro-inflammatory chemoattractant produced by microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells. It facilitates the migration of immune cells across the BBB [

91]. In our study, a 1-unit increase in IL-8 was linked to an 8% higher risk of cognitive impairment in Stage 2, consistent with prior findings [

91,

92,

93]. IL-8 levels were lowest in TBEV and control groups, highest in COVID-19. Despite this, cognitive decline was greatest in TBEV, possibly due to direct neurotropism and glial damage. Previous studies have reported elevated IL-8 levels in TBEV, particularly in CSF, while serum levels may not fully reflect localized neuroinflammation [

94]. Our findings suggest that cognitive impairment may result not only from cytokine activity but also from direct CNS injury and other mechanisms. Notably, one randomized clinical trial found that higher IL-8 levels might have protective effects against depression in low-dose endotoxin studies, especially in women [

95,

96]. Similarly, in our cohort, the lowest IL-8 levels were linked to the greatest cognitive decline.

4.6. Cluster Analysis

The conducted cluster analysis identified two distinct inflammatory profiles: one comprising 14 individuals, characterized by elevated cytokine levels, and another, larger cluster of 55 individuals with low cytokine concentrations. Patients in the high-inflammation cluster were more likely to have had COVID-19 or TBEV infections, suggesting that these pathogens may have the greatest potential to induce substantial immunological disturbances. However, not all patients in COVID-19 or TBEV groups exhibited markedly elevated cytokine levels.

No significant differences were found between clusters in psychiatric diagnoses or symptom severity, suggesting that a globally elevated inflammatory profile does not directly translate into clinical symptoms. Individual cytokine effects, which were found significant in regression analyses, may be modulated by opposing mediators (e.g., IL-1β offset by IL-10 or RANTES), resulting in a balanced immune response and a stable clinical outcome. The lack of differences in psychiatric symptoms based on global inflammatory profiles, despite significant associations for selected cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, sIL-2Rα, IL-17, IL-10), highlights the need for composite immunological markers, such as the IL-10/TNF-α ratio, which better captures the pro-/anti-inflammatory balance and may offer more predictive value than individual cytokine levels. Similar strategies have been used in previous studies on treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and chronic fatigue syndrome, where cytokine ratios or interaction patterns proved more sensitive predictors than absolute cytokine levels [

97].

The findings suggest that cytokine dysregulation and inflammation may play a predisposing rather than determining role in the development of psychiatric symptoms. Symptom development likely results from a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and environmental factors – including individual resilience, perceived stress levels, and the presence or absence of additional burdens. This aligns with the “three-hit hypothesis”, a conceptual model in which the development of conditions such as depressive-anxiety disorders or schizophrenia is influenced by an interaction of (1) genetic vulnerability (first hit), (2) early environmental factors, such as childhood trauma (second hit), and (3) later-life stressors or environmental insults (third hit) [

98,

99]. Cytokine effects in relation to psychiatric disorders appear to be context-dependent and not necessarily reflected by the average inflammatory profile in serum. It is important to underscore that the classification of certain cytokines as “pro-inflammatory” does not automatically imply a detrimental effect on mental health or overall patient well-being. Under specific conditions, particularly at appropriate concentrations and temporal stages of infection, some cytokines may in fact exert neuroprotective or homeostatic functions, mitigating pathogen-induced damage. This has been observed for cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-12(p40), RANTES, MIP-1α, and IL-8. Thus, the severity of viral illness and immune activation do not directly predict psychiatric outcomes. This aligns with other studies on COVID-19, which also highlight the multifactorial origins of psychiatric symptoms after viral infections [

49]. Furthermore, the variability in the predictive value of individual cytokines observed in our study, as well as the inconsistency with findings from other works, suggests that cytokines considered in isolation are unreliable biomarkers for psychiatric disorders. Inflammation and viral infections likely represent only partial components of the complex etiopathogenesis of mental illness, and no single causal pathway is expected to account for their development.

To advance the current understanding, future research should adopt integrative methods, e.g., proteomic, metabolomic, and genetic approaches, aligned with modern immunological insights. Emerging models like the neuroimmune-metabolic-oxidative (NIMETOX) pathway (Maes et al.) emphasize the interplay of neuroimmune, metabolic, and oxidative stress dysregulation in disorders such as MDD, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia and should be considered in the development of updated pathophysiological models of psychiatric disorders [

100]. Their framework moves beyond viewing depression as purely inflammatory, focusing instead on imbalances between Immune-Inflammatory Response System (IRS), Compensatory Immune Response System (CIRS), and Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress (O&NS). In line with our findings, they also advise against relying on isolated biomarkers, advocating for composite indicators instead [

97,

101].

5. Conclusions

This study did not confirm the impact of the viruses on the development of psychiatric disorders. Moreover, we did not observe a dominant role of SARS-CoV-2 in psychiatric disorder development, nor differences in symptom prevalence between infections. Despite distinct cytokine profiles and neurotropic properties, no virus-specific patterns of psychiatric diagnoses emerged. While some cytokines were linked to symptom risk, these associations were inconsistent with clinical presentation and insufficient as standalone biomarkers. The findings highlight the multifactorial nature of post-viral psychiatric symptoms, shaped by immunological, psychological, and environmental factors. A linear “cytokine → symptom” model is inadequate, and based on current knowledge, it is not feasible to use a single time-point measurement of inflammatory cytokines in the blood to predict the emergence of psychiatric disorders. Future research should adopt a systems-based approach, integrating composite markers and models like NIMETOX and IRS/CIRS/O&NS to better capture the complexity of psychiatric pathophysiology.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, both the total sample size and subgroup sizes were small, reducing statistical power and restricting the ability to draw causal inferences and the generalizability of the results to broader populations until validated in larger, adequately powered cohorts. Therefore, the findings of the study should be interpreted as exploratory and considered a basis for generating of further hypotheses. Differences in age, substance use, and comorbidities across groups may have influenced results. The study did not account for hospitalization details, medication use, social support, socioeconomic status, or coping strategies. Biomarkers were measured at a single time point, limiting insight into inflammatory dynamics. Using both HADS and subjective symptom ratings may have introduced inconsistencies. COVID-19 history was based on self-report without antibody testing, possibly missing asymptomatic cases. The high number of analyses increases the risk of type I error. Some limitations, especially group differences, reflect patterns seen in the general population, making the study more representative of real-world clinical samples. Even though the single-time-point cytokine measurement was intentional and aimed at testing its predictive value for post-viral psychiatric outcomes, it did not allow to capture the full dynamics of the immune response in infected patients and remains a key limitation of this study.

Supplementary Materials

The supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; methodology, P.L. and N.W.; formal analysis, P.L.; investigation, P.L.; data curation, P.L.; M.M.; J.A.; J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, P.L.; J.A.; J.K.; visualization, P.L.; supervision, N.W. M.Ż-P.; R.F.; A.M-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Medical University of Bialystok, grant number B.SUB.24.182. The financial sponsor played no role in the design, execution, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Białystok (APK.002.78.2023) on 16th February 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository. The data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30939122.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Davis, H. E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J. M.; Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 2023, 21(3), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Sillett, R.; Zhu, L.; Mendel, J.; Camplisson, I.; Dercon, Q.; Harrison, P. J. Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1 284 437 patients. The Lancet. Psychiatry 2022, 9(10), 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninger, K. A. Influenza and schizophrenia. An analysis of post-influenzal “dementia precox,” as of 1918, and five years later further studies of the psychiatric aspects of influenza. 1926. The American Journal of Psychiatry 1994, 151(6 Suppl), 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninger, K. A. REVERSIBLE SCHIZOPHRENIA. Https://Doi.Org/10.1176/Ajp.78.4.573 2006, 78(4), 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, R. (2004). Historical review: Autointoxication and focal infection theories of dementia praecox. The

World Journal of Biological Psychiatry : The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of

Biological Psychiatry, 5(2), 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Lorkiewicz, P.; Waszkiewicz, N. Viral infections in etiology of mental disorders: a broad analysis of cytokine profile similarities – a narrative review. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2024, 14, 1423739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Pol, A. N. Viral infection leading to brain dysfunction: more prevalent than appreciated? Neuron 2009, 64(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valyi-Nagy, T.; Dermody, T. S. Role of oxidative damage in the pathogenesis of viral infections of the nervous system. Histology and Histopathology 2005, 20(3), 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.; Laksono, B. M.; de Vrij, F. M. S.; Kushner, S. A.; Harschnitz, O.; van Riel, D. The neuroinvasiveness, neurotropism, and neurovirulence of SARS-CoV-2. Trends in Neurosciences 2022, 45(5), 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisiforou, A.; Charalambous, E. G.; Zanos, P. Shattering the Amyloid Illusion: The Microbial Enigma of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis—From Gut Microbiota and Viruses to Brain Biofilms. Microorganisms 2025, 13(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisiforou, A.; Spyrou, G. M. Systems Bioinformatics Reveals Possible Relationship between COVID-19 and the Development of Neurological Diseases and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Viruses 2022, 14(10), 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa Mesquita, R.; Francelino Silva Junior, L. C.; Santos Santana, F. M.; Farias de Oliveira, T.; Campos Alcântara, R.; Monteiro Arnozo, G.; Rodrigues da Silva Filho, E.; Galdino dos Santos, A. G.; Oliveira da Cunha, E. J.; Salgueiro de Aquino, S. H.; Freire de Souza, C. D. Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in the general population: systematic review. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 2021, 133(7–8), 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, R.; Bunya, N.; Tagami, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Yamakawa, K.; Endo, A.; Ogura, T.; Hirayama, A.; Yasunaga, H.; Uemura, S.; Narimatsu, E. Associated organs and system with COVID-19 death with information of organ support: a multicenter observational study. BMC Infectious Diseases 2023, 23(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, J.; Radke, J.; Dittmayer, C.; Franz, J.; Thomas, C.; Mothes, R.; Laue, M.; Schneider, J.; Brünink, S.; Greuel, S.; Lehmann, M.; Hassan, O.; Aschman, T.; Schumann, E.; Chua, R. L.; Conrad, C.; Eils, R.; Stenzel, W.; Windgassen, M.; Heppner, F. L. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nature Neuroscience 2021, 24(2), 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks, S. M.; Rosas-Hernandez, H.; Alejandro Ramirez-Lee, M.; Cuevas, E.; Talpos, J. C. Can SARS-CoV-2 infect the central nervous system via the olfactory bulb or the blood-brain barrier? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2021, 95, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuna, L.; Jakab, J.; Smolic, R.; Wu, G. Y.; Smolic, M. HCV Extrahepatic Manifestations. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology 2019, 7(2), 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Faheem, M.; Ibrahim, S. M.; Iqbal, W.; Rauff, B.; Fatima, K.; Qadri, I. Hepatitis C virus and neurological damage. World Journal of Hepatology 2016, 8(12), 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarlott, L.; Heald, E.; Forton, D. Hepatitis C virus infection, and neurological and psychiatric disorders – A review. Journal of Advanced Research 2017, 8(2), 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogovic, P.; Strle, F. Tick-borne encephalitis: A review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. World Journal of Clinical Cases: WJCC 2015, 3(5), 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustijanac, E.; Buršić, M.; Talapko, J.; Škrlec, I.; Meštrović, T.; Lišnjić, D. Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathogenesis, Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Prevention. Microorganisms 2023, 11(7), 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. H.; Haroon, E.; Raison, C. L.; Felger, J. C. Cytokine Targets in the Brain: Impact on Neurotransmitters and Neurocircuits. Depression and Anxiety 2013, 30(4), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Koyama, Y.; Shimada, S. Inflammation From Peripheral Organs to the Brain: How Does Systemic Inflammation Cause Neuroinflammation? Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14, 903455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Desse, S.; Martinez, A.; Worthen, R. J.; Jope, R. S.; Beurel, E. TNFα disrupts blood brain barrier integrity to maintain prolonged depressive-like behavior in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2018, 69, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, N. F.; Wilson, G. K.; Murray, J.; Hu, K.; Lewis, A.; Reynolds, G. M.; Stamataki, Z.; Meredith, L. W.; Rowe, I. A.; Luo, G.; Lopezramirez, M. A.; Baumert, T. F.; Weksler, B.; Couraud, P.; Kim, K. S.; Romero, I. A.; Jopling, C.; Morgello, S.; Balfe, P.; McKeating, J. A. Hepatitis C Virus Infects the Endothelial Cells of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Gastroenterology 2011, 142(3), 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M. N.; Pearce, B. D.; Biron, C. A.; Miller, A. H. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunology 2005, 18(1), 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Gomez, R.; Williams, G.; Lembke, A.; Lazzeroni, L.; Murphy, G. M.; Schatzberg, A. F. HPA Axis in Major Depression: Cortisol, Clinical Symptomatology, and Genetic Variation Predict Cognition. Molecular Psychiatry 2016, 22(4), 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvederi Murri, M.; Pariante, C. M.; Dazzan, P.; Hepgul, N.; Papadopoulos, A. S.; Zunszain, P.; Di Forti, M.; Murray, R. M.; Mondelli, V. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and clinical symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37(5), 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpekoulis, G.; Frakolaki, E.; Taka, S.; Ioannidis, A.; Vassiliou, A. G.; Kalliampakou, K. I.; Patas, K.; Karakasiliotis, I.; Aidinis, V.; Chatzipanagiotou, S.; Angelakis, E.; Vassilacopoulou, D.; Vassilaki, N. Alteration of L-Dopa decarboxylase expression in SARS-CoV-2 infection and its association with the interferon-inducible ACE2 isoform. PloS One 2021, 16(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorkiewicz, P.; Waszkiewicz, N. Biomarkers of Post-COVID Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlberg Weidenfors, J.; Griška, V.; Li, X.; Pranckevičienė, A.; Pakalnienė, J.; Atlas, A.; Franzén-Röhl, E.; Piehl, F.; Lindquist, L.; Mickienė, A.; Engberg, G.; Schwieler, L.; Erhardt, S. Dysregulation of the kynurenine pathway is related to persistent cognitive impairment in tick-borne encephalitis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2025, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisiforou, A.; Zanos, P. From Viral Infections to Alzheimer’s Disease: Unveiling the Mechanistic Links Through Systems Bioinformatics. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, 230 Suppl 2, S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L. M. T. Gut Bacteria and Neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022, 10(9), 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, M.; Aurora, N.; Herrera, L.; Bhatia, M.; Wilen, E.; Wakefield, S. Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clinics and Practice 2017, 7(4), 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J. R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P. J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. The Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8(5), 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czupryna, P.; Grygorczuk, S.; Krawczuk, K.; Pancewicz, S.; Zajkowska, J.; Dunaj, J.; Matosek, A.; Kondrusik, M.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A. Sequelae of tick-borne encephalitis in retrospective analysis of 1072 patients. Epidemiology and Infection 2018, 146(13), 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonka, J.; Piotrowski, D.; Janczewska, E.; Pisula, A.; Musialik, J.; Jaroszewicz, J. Significant Decrease in the Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression after Hepatitis C Eradication. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11(11), 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, G.; M, T. Inflammatory theory of depression. Psychiatria Polska 2018, 52(3), 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. J.; Buckley, P.; Seabolt, W.; Mellor, A.; Kirkpatrick, B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biological Psychiatry 2011, 70(7), 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabbernia, A.; Taslimi, S.; Brietzke, E.; Ashrafi, M. Cytokine alterations in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of 30 studies. Biological Psychiatry 2013, 74(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Z.; Ji, J.; Wen, C. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: The Current Evidence and Treatment Strategies. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coperchini, F.; Chiovato, L.; Croce, L.; Magri, F.; Rotondi, M. The cytokine storm in COVID-19: An overview of the involvement of the chemokine/chemokine-receptor system. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2020, 53, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Levis, B.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Krishnan, A.; Neupane, D.; Bhandari, P. M.; Negeri, Z.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression subscale (HADS-D) to screen for major depression: systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A. A.; Haug, T. T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2002, 52(2), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research, 4th Ed.). ed; n.d.; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A. L.; Mcnamara, M. S.; Sinclair, D. A. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging 2020, 12(10), 9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Nalla, L. V.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, N.; Singh, A. A.; Malim, F. M.; Ghatage, M.; Mukarram, M.; Pawar, A.; Parihar, N.; Arya, N.; Khairnar, A. Association of COVID-19 with Comorbidities: An Update. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2023, 6(3), 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, K.; Cuapio, A.; Sandberg, J. T.; Varnaite, R.; Michaëlsson, J.; Björkström, N. K.; Sandberg, J. K.; Klingström, J.; Lindquist, L.; Gredmark Russ, S.; Ljunggren, H. G. Cell-Mediated Immune Responses and Immunopathogenesis of Human Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus-Infection. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SF, P.; YC, H. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2020, 130(5), 2202–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M., Skorniewska, Z., De Deyn, T., Hampshire, A., Trender, W. R., Hellyer, P. J., Chalmers, J. D., Ho,

L. P., Horsley, A., Marks, M., Poinasamy, K., Raman, B., Leavy, O. C., Richardson, M., Elneima, O.,

McAuley, H. J. C., Shikotra, A., Singapuri, A., Sereno, M., … Turnbull, A. (2024). Cognitive and psychiatric

symptom trajectories 2–3 years after hospital admission for COVID-19: a longitudinal, prospective cohort

study in the UK. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(9), 696–708. [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Smith, S. M.; Prohl, A. K.; Peters, J. M.; Warfield, S. K.; Scherrer, B.; Harrison, P. J. A structural brain network of genetic vulnerability to psychiatric illness. Molecular Psychiatry 2021, 26(6), 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeshima, T.; Kim, H.-C. Involvement of Genetic and Environmental Factors in the Onset of Depression. Experimental Neurobiology 2013, 22(4), 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, S. J.; Jackman, N. A.; Claycomb, R. J. Interleukin-1β in Central Nervous System Injury and Repair. European Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease 2012, 1(2), 195. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4465544/.

- Zunszain, P. A., Anacker, C., Cattaneo, A., Choudhury, S., Musaelyan, K., Myint, A. M., Thuret, S., Price,

J., & Pariante, C. M. (2012). Interleukin-1β: a new regulator of the kynurenine pathway affecting human

hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of

Neuropsychopharmacology, 37(4), 939–949. [CrossRef]

- Zunszain, P. A.; Anacker, C.; Cattaneo, A.; Choudhury, S.; Musaelyan, K.; Myint, A. M.; Thuret, S.; Price, J.; Pariante, C. M. Interleukin-1β: a new regulator of the kynurenine pathway affecting human hippocampal neurogenesis. In Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Neuropsychopharmacology, 2012; Volume 37, 4, pp. 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figiel, I. Pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha as a neuroprotective agent in the brain. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis 2008, 68(4), 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.; Muhammad, M. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha: A Major Cytokine of Brain Neuroinflammation. Cytokines 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Fischer, R.; Naudé, P. J. W.; Maier, O.; Nyakas, C.; Duffey, M.; Van Der Zee, E. A.; Dekens, D.; Douwenga, W.; Herrmann, A.; Guenzi, E.; Kontermann, R. E.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Eisel, U. L. M. Essential protective role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 in neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113(43), 12304–12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, V.; Mohand-Said, S.; Hanoteau, N.; Fuchs, C.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Eisel, U. Neurodegenerative and neuroprotective effects of tumor Necrosis factor (TNF) in retinal ischemia: opposite roles of TNF receptor 1 and TNF receptor 2. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2002, 22(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, H. Advances in the study of IL-17 in neurological diseases and mental disorders. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1284304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisman, A.; Hauptmann, J.; Regen, T. The role of IL-17 in CNS diseases. Acta Neuropathologica 2015, 129(5), 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M. H.; Zheng, Q. F.; Jia, X. Z.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y. C.; Wang, C. Y.; Lin, Q. Y.; Zhang, F. Y.; Zhao, R. B.; Xu, H. W.; Zhou, J. H.; Yuan, H. P.; Zhang, W. H.; Ren, H. Neuroprotection effect of interleukin (IL)-17 secreted by reactive astrocytes is emerged from a high-level IL-17-containing environment during acute neuroinflammation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175(2), 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Jung, Y. O.; Kim, D.-J.; Kang, C.-M.; Moon, Y.-M.; Heo, Y.-J.; Oh, H.-J.; Park, S.-J.; Yang, S.-H.; Kwok, S. K.; Ju, J.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Sung, Y. C.; Kim, H.-Y.; Cho, M.-L. IL-12p40 Homodimer Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Arthritis. The Journal of Immunology Author Choice 2015, 195(7), 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X. Novel functions of grass carp three p40 isoforms as modulators of Th17 signature cytokine expression in head kidney leukocytes. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2020, 98, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, V.; Noonan, D. M.; Abdalalem, E.; Goletti, D.; Sansone, C.; Calabrone, L.; Albini, A. The multifaceted nature of IL-10: regulation, role in immunological homeostasis and its relevance to cancer, COVID-19 and post-COVID conditions. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1161067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, S.; Correia-Neves, M.; Mesquita, A. R.; Palha, J. A.; Sousa, N. Interleukin-10: a key cytokine in depression? Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology 2009, 2009, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N. S.; Casserly, B.; Ayala, A. The Compensatory Anti-inflammatory Response syndrome (CARS) in Critically ill patients. Clinics in Chest Medicine 2008, 29(4), 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, A. K.; Ciurkiewicz, M.; Herder, V.; Khan, M. A.; Hensel, N.; Claus, P.; Beckstette, M.; Teich, R.; Floess, S.; Baumgärtner, W.; Jung, K.; Huehn, J.; Beineke, A. Intact interleukin-10 receptor signaling protects from hippocampal damage elicited by experimental neurotropic virus infection of SJL mice. Scientific Reports 2018, 8:1(8(1)), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Iwata, S.; Hidese, S.; Ishiwata, S.; Ide, S.; Tanaka, H.; Sonomoto, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Nakayamada, S.; Ikenouchi, A.; Hattori, K.; Kunugi, H.; Yoshimura, R.; Tanaka, Y. Reduced homovanillic acid, SDF-1α and SCGF-β levels in cerebrospinal fluid are related to depressive states in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 2023, 62(10), 3490–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ho, R. C. M.; Mak, A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Journal of Affective Disorders 2012, 139(3), 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. F.; Solmi, M.; Sanches, M.; Machado, M. O.; Stubbs, B.; Ajnakina, O.; Sherman, C.; Sun, Y. R.; Liu, C. S.; Brunoni, A. R.; Pigato, G.; Fernandes, B. S.; Bortolato, B.; Husain, M. I.; Dragioti, E.; Firth, J.; Cosco, T. D.; Maes, M.; Berk, M.; Herrmann, N. Evidence-based umbrella review of 162 peripheral biomarkers for major mental disorders. Translational Psychiatry 2020, 10(1), 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X. N.; Lu, Y.; Tan, C. T. Y.; Liu, L. Y.; Yu, J. T.; Feng, L.; Larbi, A. Identification of inflammatory and vascular markers associated with mild cognitive impairment. Aging 2019, 11(8), 2403–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyman, O.; Sprent, J. The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nature Reviews. Immunology 2012, 12(3), 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. H.; Cantrell, D. A. Signaling and Function of Interleukin-2 in T Lymphocytes. Annual Review of Immunology 2018, 36, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Song, C. Low-Dose IL-2 Attenuated Depression-like Behaviors and Pathological Changes through Restoring the Balances between IL-6 and TGF-β and between Th17 and Treg in a Chronic Stress-Induced Mouse Model of Depression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, Vol. 23(Page 13856, 23(22)), 13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, S.; Zanardi, R.; Mandelli, A.; Aggio, V.; Finardi, A.; Lorenzi, C.; Borsellino, G.; Carminati, M.; Manfredi, E.; Tomasi, E.; Spadini, S.; Colombo, C.; Drexhage, H. A.; Furlan, R.; Benedetti, F. Low-dose interleukin 2 antidepressant potentiation in unipolar and bipolar depression: Safety, efficacy, and immunological biomarkers. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2024, 118, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaspina, A.; Moir, S.; Chaitt, D. G.; Rehm, C. A.; Kottilil, S.; Falloon, J.; Fauci, A. S. Idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia is associated with increases in immature/transitional B cells and serum levels of IL-7. Blood 2006, 109(5), 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, L. A.; Grant, R. M.; Deeks, S. G.; Schmidt, D.; De Rosa, S. C.; Herzenberg, L. A.; Herndier, B. G.; Andersson, J.; Mccune, J. M. Increased production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T-cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nature Medicine 2001, 7(1), 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. O.; Jeffries, C. D.; Addington, J.; Bearden, C. E.; Cadenhead, K. S.; Cannon, T. D.; Cornblatt, B. A.; Mathalon, D. H.; McGlashan, T. H.; Seidman, L. J.; Tsuang, M. T.; Walker, E. F.; Woods, S. W.; Heinssen, R. Towards a psychosis risk blood diagnostic for persons experiencing high-risk symptoms: preliminary results from the NAPLS project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2015, 41(2), 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, S.; Qusar, M. M. A. S.; Shahriar, M.; Islam, S. M. A.; Bhuiyan, M. A.; Islam, M. R. Altered serum interleukin-7 and interleukin-10 are associated with drug-free major depressive disorder. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2020, 10, 2045125320916655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. R.; Wiechmann, A.; Edwards, M.; Johnson, L. A.; O’Bryant, S. E. IL-7 and Depression: The importance of gender and blood fraction. Behavioural Brain Research 2016, 315, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Angelosanto, J. M.; Nadwodny, K. L.; Blackburn, S. D.; Wherry, E. J. A Role for the Chemokine RANTES in Regulating CD8 T Cell Responses during Chronic Viral Infection. PLOS Pathogens 2011, 7(7), e1002098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokami, H.; Ago, T.; Sugimori, H.; Kuroda, J.; Awano, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kiyohara, Y.; Kamouchi, M.; Kitazono, T. RANTES has a potential to play a neuroprotective role in an autocrine/paracrine manner after ischemic stroke. Brain Research 2013, 1517, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, D.; Thirumangalakudi, L.; Grammas, P. RANTES upregulation in the Alzheimer’s disease brain: a possible neuroprotective role. Neurobiology of Aging 2008, 31(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, V.; Copani, A.; Besong, G.; Scoto, G.; Nicoletti, F. Neuroprotective activity of chemokines against N-methyl-D-aspartate or β-amyloid-induced toxicity in culture. European Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 399(2–3), 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, E.; Faivre, E.; Dutar, P.; Alves Pires, C.; Demeyer, D.; Caillierez, R.; Laloux, C.; Buée, L.; Blum, D.; Humez, S. The Chemokine MIP-1α/CCL3 impairs mouse hippocampal synaptic transmission, plasticity and memory. Scientific Reports 2015, 5:1(5(1)), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvig, H. V.; Aam, S.; Alme, K. N.; Askim, T.; Beyer, M. K.; Ellekjær, H.; Ihle-Hansen, H.; Lydersen, S.; Mollnes, T. E.; Munthe-Kaas, R.; Næss, H.; Saltvedt, I.; Seljeseth, Y. M.; Thingstad, P.; Wethal, T.; Knapskog, A. B. Plasma Inflammatory Biomarkers Are Associated With Poststroke Cognitive Impairment: The Nor-COAST Study. Stroke 2023, 54(5), 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousman, S. S.; David, S. MIP-1α, MCP-1, GM-CSF, and TNF-α Control the Immune Cell Response That Mediates Rapid Phagocytosis of Myelin from the Adult Mouse Spinal Cord. The Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21(13), 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkovic, V. M.; Stanton, E. H.; Nothdurfter, C.; Rupprecht, R.; Wetzel, C. H. The Role of Chemokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20(9), 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, S. P.; Nerurkar, L.; Krishnadas, R.; Johnman, C.; Graham, G. J.; Cavanagh, J. Chemokines in depression in health and in inflammatory illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry 2017, 23:1(23(1)), 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, W.; Mendez, M. J.; Gossman, Z. C.; Chomyk, A.; Boylan, B. T.; Kidd, G. J.; Phares, T. W.; Bergmann, C. C.; Trapp, B. D. Neuroprotection by Preconditioning in Mice is Dependent on MyD88-Mediated CXCL10 Expression in Endothelial Cells. ASN Neuro 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S. J. Role of interleukin 8 in depression and other psychiatric disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 2021, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baune, B. T.; Ponath, G.; Golledge, J.; Varga, G.; Arolt, V.; Rothermundt, M.; Berger, K. Association between IL-8 cytokine and cognitive performance in an elderly general population—The MEMO-Study. Neurobiology of Aging 2008, 29(6), 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, N. S. N.; Gyanwali, B.; Lai, M. K. P.; Chai, Y. L.; Chong, J. R.; Chong, E. J. Y.; Chen, C.; Tan, C. S.; Hilal, S. Association of Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-8 with Cognitive Decline in an Asian Memory Clinic Population. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD 2023, 92(2), 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]