Introduction

Hoarding disorder (HD) refers to a persistent failure to discard possessions, a behaviour driven by a strong urge to save items or the distress that accompanies discarding them. The resulting clutter frequently blocks living spaces and limits everyday activities [

1]. Although historically viewed as a variant of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), clinical and epidemiological work over the past two decades has shown that primary hoarding differs from OCD in phenomenology, comorbidity, and treatment response, prompting its inclusion as a separate diagnosis in DSM-5 [

2,

3]. HD often presents without the classic ego-dystonic obsessions and ritualistic behaviours typical of OCD; instead, patients report emotional attachment to objects, chronic indecision, perfectionism, and limited insight [

4,

5]. Community surveys indicate a prevalence between 2% and 6% in adults, with rates rising steadily across the lifespan and carrying marked health and safety risks [

6,

7].

Twin research leaves little doubt that genetics play a sizeable part in liability to hoarding. Across adult samples, heritability estimates cluster around 30–50% [

8], yet longitudinal work points to age-dependent shifts. In a large Swedish cohort, genetic influence fell from 41% at 15 years to 29% in the mid-twenties, while environmental effects unique to each twin grew with age [

9]. Sex-specific patterns have also been noted: genetic factors were stronger in 15-year-old boys, whereas shared household factors explained a notable share of variance in girls of the same age [

9].

Molecular findings, however, lag behind those pedigree observations. The largest genome-wide association study (GWAS) so far combined seven cohorts (N ≈ 27 000) yet detected no single variant at genome-wide significance; nonetheless, it produced a SNP-based heritability of roughly 11% and revealed polygenic links with schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, and educational attainment [

10]. Candidate reports have raised glutamatergic genes such as SLC1A1 [

11], but replication remains scarce.

In parallel, increasingly powerful OCD GWASs have turned attention toward neurodevelopmental pruning pathways rather than primary glutamatergic imbalance. A re-analysis of the 2025 OCD meta-data showed strong enrichment of risk within genes that guide adolescent synaptic elimination—major-histocompatibility-complex class I, complement cascade, adhesion molecules, and astrocytic factors—whereas glutamate-related panels yielded only modest signal [

12]. These findings raise the question of whether HD shares that pruning-centred architecture or follows a separate genetic route that aligns better with its lifelong deficits in flexibility and decision-making.

To address this, the present work revisits the 2022 hoarding GWAS using the same analytic pipeline applied to OCD: (a) MAGMA for gene-level tests, (b) stratified LD-score regression and custom χ² partitioning to gauge pathway-specific heritability, and (c) S-PrediXcan to examine tissue-specific, genetically predicted expression. By holding constant our annotation sets—core drug-target focused glutamatergic genes, extended glutamatergic pathways, two curated pruning panels, and two negative-control sets (monoaminergic and housekeeping)—we aim to deliver a direct, methodologically harmonised comparison. Clarifying whether HD risk is anchored in synaptic pruning, ongoing plasticity, or an altogether different mechanism will refine its placement within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum and shape future treatment strategies.

Methods

Genetic Correlation Analysis

Genetic overlap between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and hoarding disorder was examined with cross-trait linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC). LDSC exploits the relationship between GWAS test statistics and local linkage disequilibrium (LD) to separate true polygenic signal from inflation due to population structure or sample overlap [

13,

14].

The OCD summary statistics were taken from the large 2025 meta-analysis of 53,660 cases and 2,044,417 controls [

15]. Hoarding data came from the 2022 meta-analysis of 27,651 participants with quantified hoarding symptoms [

10]. Before analysis, both sets of results were filtered to SNPs with minor-allele frequency ≥ 1% and imputation quality (INFO) ≥ 0.90 when available. Variant alleles were converted to uppercase, and Z-scores were obtained as β/SE. Effective sample size (N_eff) was either reported directly or calculated from case–control counts (N_eff = 4 / (1/cases + 1/controls)).

Allele harmonisation followed standard LDSC guidelines. SNPs were aligned by rsID; palindromic A/T and C/G variants were dropped; strand flips or sign changes were applied where necessary. Approximately 5.6 million SNPs remained that were present in both studies and in the European-ancestry LD reference panel derived from 1000 Genomes Phase 3.

Liability-scale SNP heritabilities assumed prevalences of 2% for OCD and 2–6% for hoarding. Regression intercepts (within-trait expected ≈ 1; cross-trait expected ≈ 0) were inspected for residual confounding. Block-jackknife (200 blocks) provided standard errors. All computations used a customised Python wrapper for LDSC with the publicly available European LD scores.

Gene-Based Association Testing Using MAGMA

Gene associations were evaluated with MAGMA v1.10 [

16]. Publicly available summary statistics for hoarding symptoms were taken from the PGC meta-analysis of 27,651 participants [

10]. An effective sample size of 31,188 was specified.

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were assigned to genes using NCBI37.3 (hg19) coordinates, extending 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream of each gene. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was modelled with the European subset of the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 reference panel. MAGMA’s SNP-wise mean model then aggregated variant signals into a gene Z-score while accounting for LD. We tested 18,304 protein-coding genes; consequently, genome-wide significance required p < 2.73 × 10⁻⁶ (Bonferroni). Suggestive and nominal thresholds were set at p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively.

To explore pathway-level enrichment, six a priori gene sets were analysed in MAGMA’s competitive framework, which compares the average Z-score of genes in a set with the genome-wide background after adjusting for gene length and LD. Two glutamatergic panels (23 and 130 genes), two synaptic pruning panels (38 and 262 genes), and two negative controls—monoaminergic signalling (101 genes) and housekeeping functions (182 genes)—were tested. X- and Y-linked loci were omitted because the LD reference does not include sex chromosomes. Family-wise error for the six tests was controlled with a Bonferroni threshold of p < 0.0083; false-discovery-rate (FDR) values were also computed.

Annotation Enrichment Analysis and Partitioned Heritability Analysis

Partitioned heritability was examined with an adaptation of stratified linkage-disequilibrium score regression [

17]. Summary statistics for hoarding symptoms were taken from the most recent GWAS meta-analysis of 27,651 participants [

10]. After filtering variants on INFO ≥ 0.90 and deriving Z-scores from the reported β / SE estimates, an effective sample size of 31,188 was specified.

Six binary annotations were generated. For every gene in a set, genomic coordinates (GRCh37) were extended 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) falling inside these windows were flagged. The panels comprised:

1. A core glutamatergic-drug target list (23 genes).

2. An expanded glutamatergic list (130 genes).

3. A shortened synaptic-pruning list (38 genes).

4. An expanded pruning list (262 genes).

5. A monoaminergic control list (101 genes).

6. A housekeeping control list (182 genes).

Sex-chromosome genes were omitted because the European 1000 Genomes Phase 3 LD reference lacks X and Y markers. For each annotation we calculated the mean χ² statistic of tagged SNPs and compared it with the remainder of the genome. Standard errors were obtained with a 200-block jack-knife, yielding one-sided enrichment tests. Distributional differences between annotated and background SNPs were evaluated with Mann–Whitney U statistics. Bonferroni correction for six primary tests set the significance threshold at p < 0.0083; false-discovery-rate values were also recorded. All steps—window creation, SNP assignment, regression and resampling—were executed in custom Python scripts.

For each annotation the analytic pipeline was repeated. Stratified linkage-disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) was applied, estimated the proportion of SNP-heritability (h²) explained and its standard error, conditional on the full baseline model. Enrichment was defined as the ratio of observed to expected h². Significance was evaluated with one-tailed Z-tests and with Mann–Whitney U tests comparing the χ² distribution of annotated versus background SNPs. A Bonferroni threshold of p < 0.0083 (six primary tests) controlled the family-wise error rate.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

We applied the summary-data implementation of PrediXcan, S-PrediXcan [

18], to test whether genetically regulated gene expression is associated with hoarding symptoms. GWAS summary statistics were taken from the most recent meta-analysis of hoarding symptoms [

10]. After harmonising alleles, Z-scores were calculated from the published effect estimates and standard errors; the effective sample size was 31,188.

Expression prediction weights were those released by the GTEx Consortium (v8, MASHR models) [

19]. Six neuro-behavioural tissues thought to be relevant for compulsivity and executive control were selected a priori: frontal cortex (BA9), anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), hippocampus, amygdala, nucleus accumbens and caudate. For every tissue, the accompanying SNP covariance matrix supplied by GTEx was used to account for linkage disequilibrium.

S-PrediXcan calculates a gene statistic , where w is the vector of eQTL weights, z the GWAS Z-scores and Σ the SNP covariance; the denominator ensures proper scaling. Tests were performed for each gene–tissue pair and corrected first within tissue by false-discovery rate (FDR) and, more stringently, by Bonferroni. We then mapped the resulting gene list onto six a-priori gene sets that had shown heritability enrichment in LD-score analyses: two glutamatergic panels, two synaptic-pruning panels, and two negative controls (monoaminergic and housekeeping genes). For every set we compared the distribution of absolute Z-scores with that of all other genes using one-sided Mann-Whitney tests.

Cross-Disorder Comparison

To place the hoarding findings in a broader psychiatric context, an identical analytic pipeline was run on the most recent summary statistics for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) released in 2025 [

15]. The pipeline comprised three sequential steps. First, gene-level association was calculated with MAGMA, using the same window size, SNP filters and reference LD panel that were applied in the hoarding analysis. Second, enrichment of single-variant signal within predefined annotations was quantified through both custom χ² ratio tests and stratified LD-score regression; parameter settings (baseline model, jack-knife blocks, and Bonferroni thresholds) were held constant across disorders. Third, S-PrediXcan was used to relate genetically predicted expression in six GTEx brain tissues to OCD case status, again using the identical weight sets and covariance matrices employed for hoarding. The gene sets interrogated—core and expanded glutamatergic panels, shortened and expanded pruning panels, plus monoaminergic and housekeeping controls—were unchanged. Full OCD results are presented elsewhere [

12] and allow direct, methodologically harmonised comparison of pathway effects between hoarding and OCD.

Results

Genetic Correlation Between OCD and Hoarding Disorder

After quality control, 5,551,761 shared SNPs were included (N_eff = 72,436 for OCD; 55,302 for hoarding). Liability-scale SNP heritability was 0.1093 (SE = 0.0070) for OCD and 0.0073 (SE = 0.0061) for hoarding. LDSC intercepts were close to expectations (OCD = 1.0054; hoarding = 1.0146), and the cross-trait intercept was 0.0014, indicating negligible inflation from sample overlap.

The estimated genetic correlation was r_g = 0.4655 (SE = 0.2533; Z = 1.84; p = 0.066). Although positive and of moderate magnitude, this correlation did not achieve conventional significance (p < 0.05). Thus, with current sample sizes, common-variant sharing between OCD and hoarding disorder could not be confirmed.

Overall model fit metrics (mean χ² = 1.22 for OCD, 1.03 for hoarding) and intercept values indicated that the estimates were not driven by uncontrolled stratification or cryptic relatedness.

MAGMA Findings

Of the 18,304 genes examined, none surpassed the Bonferroni threshold. Seventeen reached the suggestive level (p < 0.001) and 980 reached nominal significance. The most prominent signals were observed for CEBPA (p = 1.2 × 10⁻⁵; Z = 4.23) and SLC17A4 (p = 2.5 × 10⁻⁵; Z = 4.06). Several histone cluster genes on chromosome 6, PTPRM, MYH10, and the caveolin genes CAV1/CAV2 showed p-values between 7 × 10⁻⁵ and 8 × 10⁻⁴.

None of the six predefined sets met the Bonferroni-corrected threshold. The core glutamatergic panel showed a modest, non-significant elevation of its mean Z-score relative to the genome (one-sided p = 0.36). Within this panel, three genes—NTRK2, CYP3A4, and CYP2D6—were nominally significant. The expanded glutamatergic panel produced a similar pattern (p = 0.36) and included nine nominal genes, such as CREB3 and NTRK2. Synaptic pruning sets displayed weak trends (p = 0.52 and p = 0.23 for the short and extended versions, respectively); notable nominal hits included HLA-B, MEF2C, and TCF4. Monoaminergic and housekeeping controls did not deviate from expectation (p > 0.49). A Kruskal–Wallis comparison of Z-score distributions across all panels was non-significant (H = 0.605; p = 0.99).

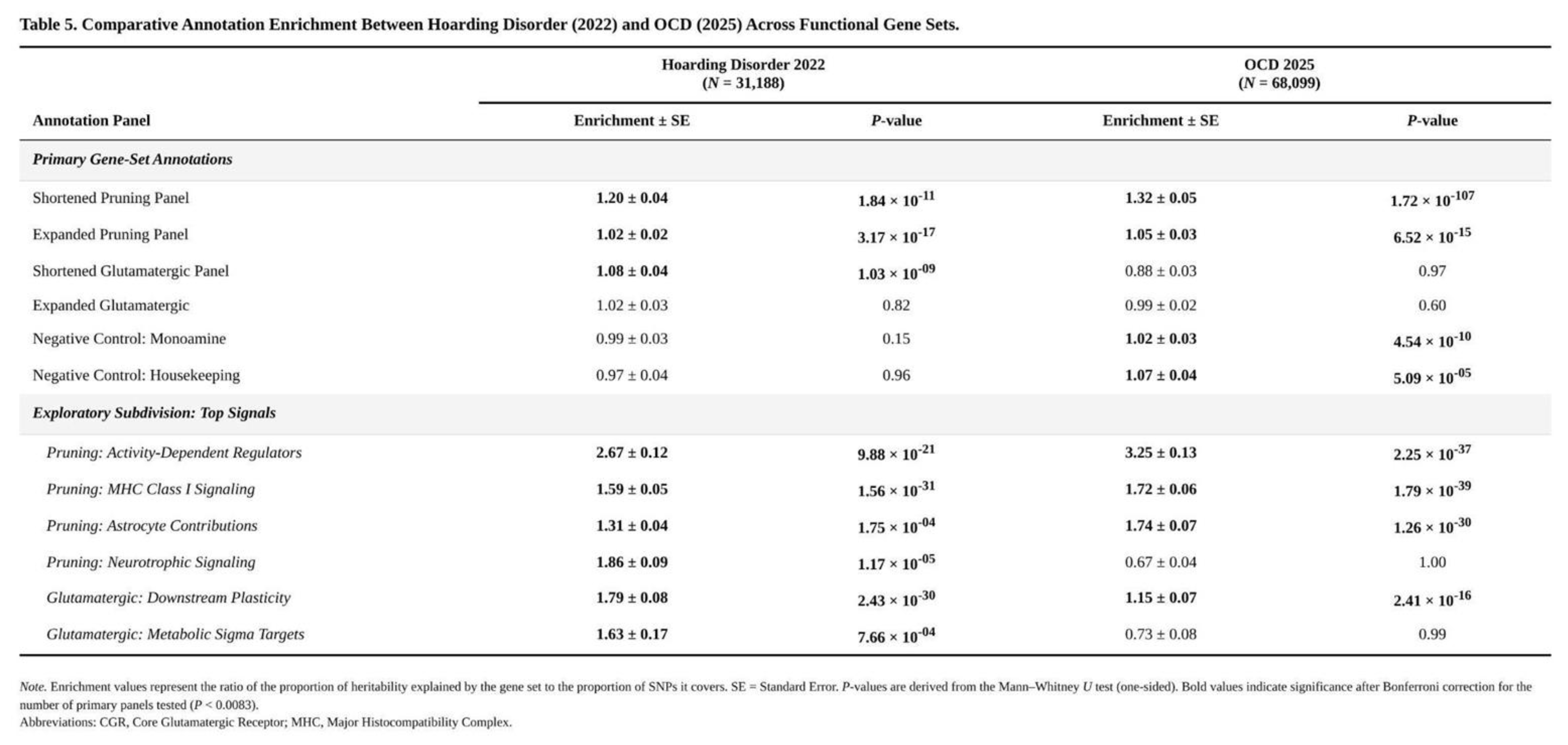

Annotation Enrichment Across Gene Sets

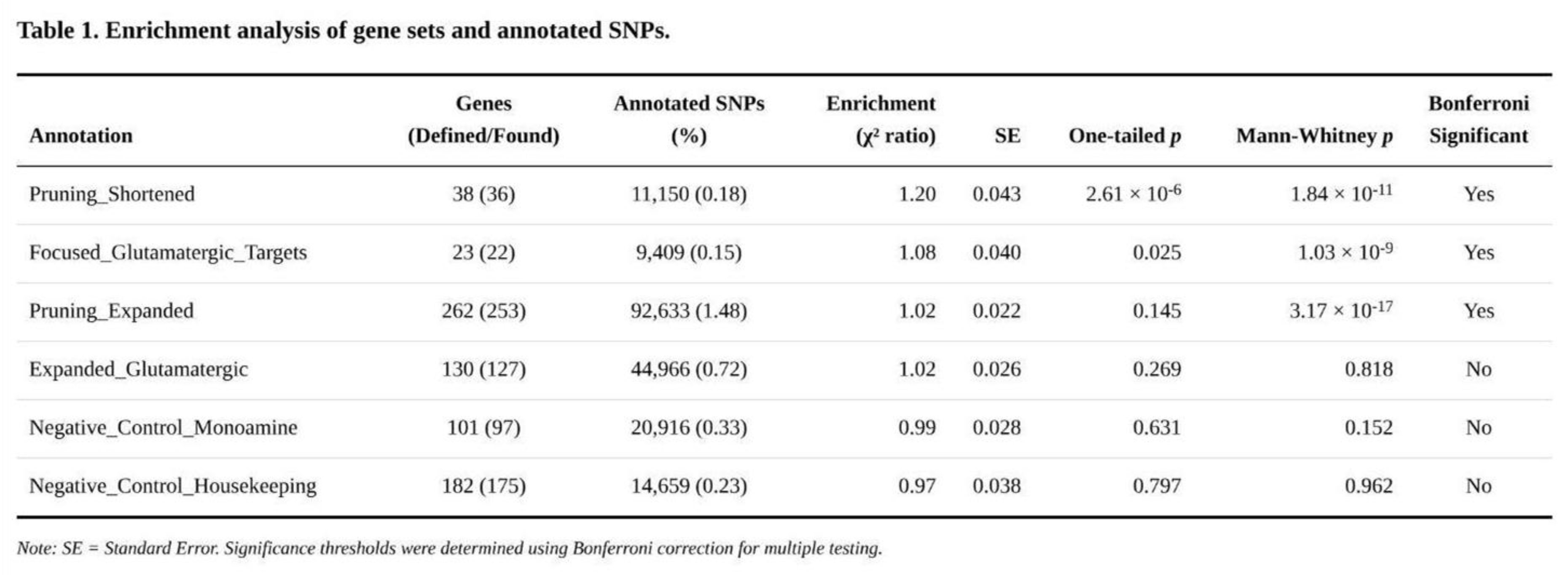

Three of the six annotations surpassed the Bonferroni threshold (

Table 1). The shortened pruning panel showed the largest effect: SNPs within its 36 mapped genes covered 0.18% of markers yet accounted for a 1.20-fold excess of χ² signal (SE = 0.043, one-sided p = 2.6 × 10⁻⁶; Mann–Whitney p = 1.8 × 10⁻¹¹). The core glutamatergic panel, comprising 22 mapped genes and 0.15% of SNPs, yielded 1.08-fold enrichment (SE = 0.040, p = 0.025; Mann–Whitney p = 1.0 × 10⁻⁹). The expanded pruning panel (253 genes, 1.48% of SNPs) produced a modest but significant 1.02-fold enrichment (SE = 0.022, p = 0.145 by jack-knife yet Mann–Whitney p = 3.2 × 10⁻¹⁷); the large U-test signal and minimal jack-knife excess suggest a broad shift in the distribution rather than a few extreme SNPs. The expanded glutamatergic set trended in the same direction (1.02-fold, p = 0.27) but did not reach significance. Neither monoaminergic nor housekeeping controls departed from expectation.

Exploratory subdivision highlighted which pathways drove the effects. Within the core glutamatergic annotation, downstream plasticity genes (e.g., NTRK2) exhibited 1.79-fold enrichment (p = 1.3 × 10⁻²⁴), and metabolic/sigma-receptor targets 1.63-fold (p = 1.4 × 10⁻⁴). Pruning annotations were propelled by activity-dependent regulators (2.67-fold, p = 2.5 × 10⁻⁴⁵), neurotrophic signalling (1.86-fold, p = 5.9 × 10⁻²¹), MHC class I components (1.59-fold, p = 8.5 × 10⁻³⁰) and astrocytic genes (1.31-fold, p = 5.0 × 10⁻¹⁸). Control panels showed flat distributions (p > 0.49), reinforcing the specificity of the synaptic and glutamatergic findings.

Partitioned Heritability Across Functional Annotations

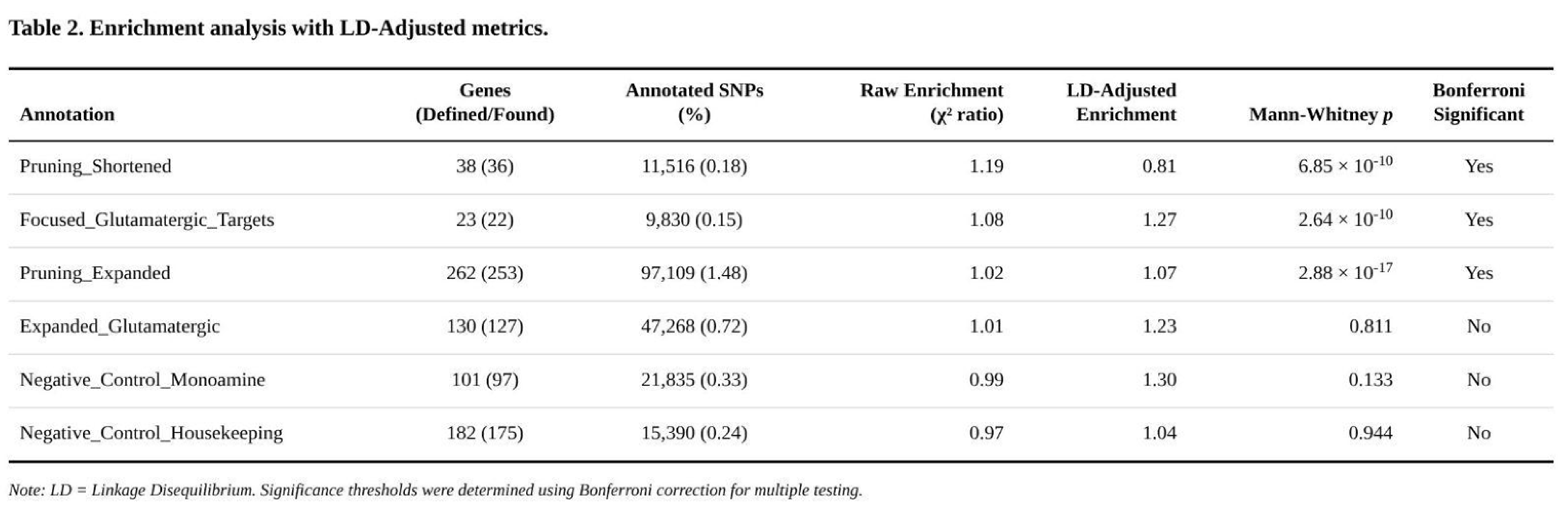

Three of the six gene-set annotations captured significantly more SNP-heritability than expected after Bonferroni correction (

Table 2). The shortened pruning panel, although covering only 0.18% of common variants, accounted for a 19% excess of χ² signal (enrichment = 1.19; Z = 4.57; Mann–Whitney p = 6.9 × 10⁻¹⁰). Core glutamatergic targets were also enriched (enrichment = 1.08; Z = 2.25; Mann–Whitney p = 2.6 × 10⁻¹⁰). The expanded pruning panel showed a modest but highly significant effect (enrichment = 1.02; Z = 1.44; Mann–Whitney p = 2.9 × 10⁻¹⁷), indicating a broad upward shift in χ² values rather than isolated outliers. The larger glutamatergic set produced only nominal evidence (p = 0.27) and both negative-control annotations were null (p > 0.13).

Exploratory subdivision of the enriched panels highlighted pathway components with the strongest signal. Within the glutamatergic core, downstream plasticity genes (e.g., NTRK2) exhibited nearly 1.8-fold enrichment, whereas sigma-receptor–metabolic genes showed ~1.6-fold enrichment. Pruning-related enrichment was driven by activity-dependent regulators, neurotrophic signalling molecules, MHC class I components and astrocyte markers, each displaying fold-enrichment between 1.3 and 2.7.

Together with earlier gene-based results, these findings suggest that common-variant risk for hoarding symptoms concentrates in loci involved in synaptic pruning and glutamatergic plasticity, whereas canonical monoaminergic and essential housekeeping pathways do not contribute detectable excess heritability.

Transcriptome-Wide Findings

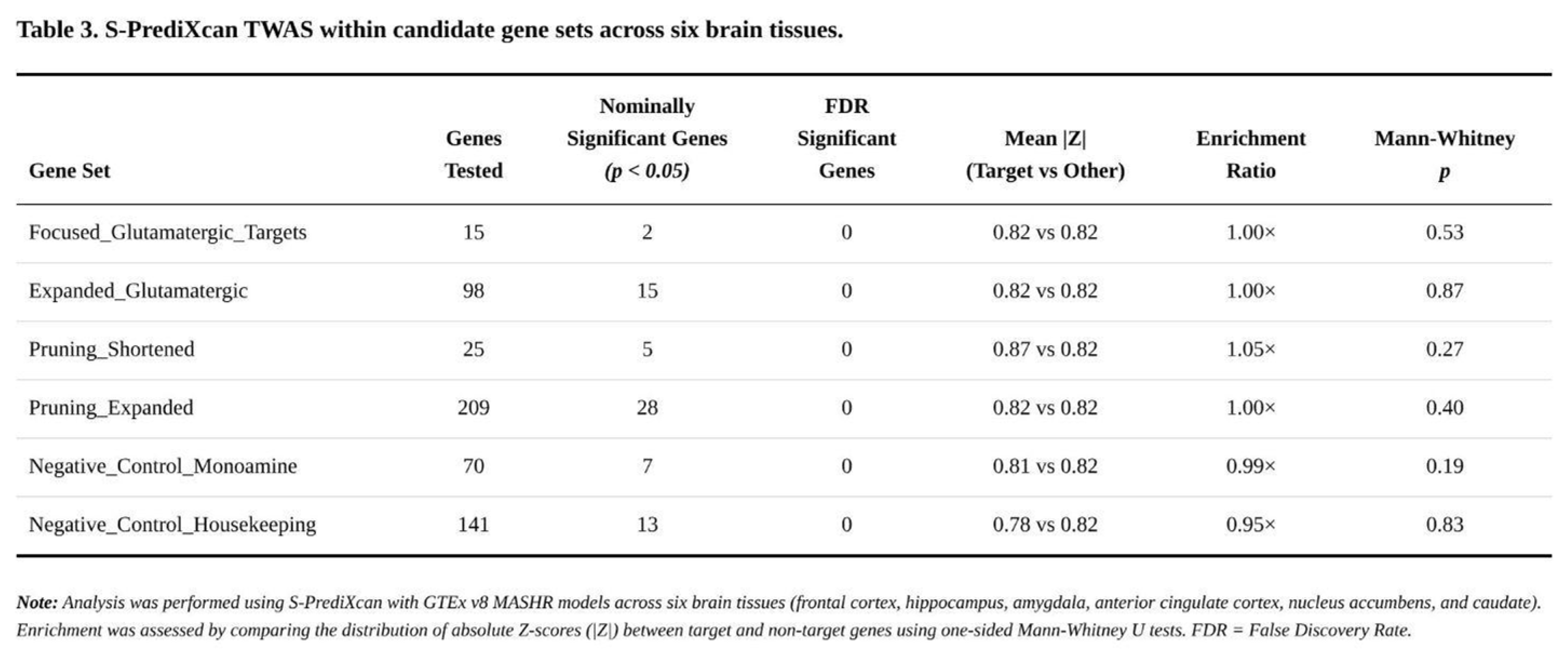

Across the six brain tissues, 62,427 gene–tissue pairs (15,753 unique genes) were analysed. None survived FDR < 0.05, and only a single association reached tissue-specific Bonferroni significance. In total, 3,620 gene–tissue pairs (≈1,652 genes) were nominally significant at p < 0.05—very close to chance expectation (

Table 3).

Within the targeted pathways, nominal signals were sparse. Among 15 core glutamatergic genes, two reached nominal significance: NTRK2 in frontal cortex (Z = –2.95, p = 0.003) and CYP2D6 in hippocampus (Z = 2.26, p = 0.024). The expanded glutamatergic panel (98 testable genes) yielded fifteen nominal hits, led again by NTRK2 and by MLST8. The shortened pruning list produced five nominal associations (e.g. HLA-B, MERTK), and the larger pruning list twenty-eight, but patterns were inconsistent across tissues.

Gene-set enrichment analyses were uniformly negative. Mean |Z| values differed by no more than 5% between targets and background (enrichment ratios 0.95–1.05); Mann-Whitney p-values ranged from 0.19 to 0.87. Control sets behaved similarly, indicating no systematic inflation.

The absence of robust TWAS signals contrasts with the modest but significant heritability enrichment previously observed in pruning- and glutamatergic annotations [

17]. Together, the results suggest that common-variant liability for hoarding symptoms may act through regulatory mechanisms not adequately captured by current brain eQTL resources, or through tissues and cell types not included in the present analysis.

Discussion

Results Interpretation and Comparison with OCD

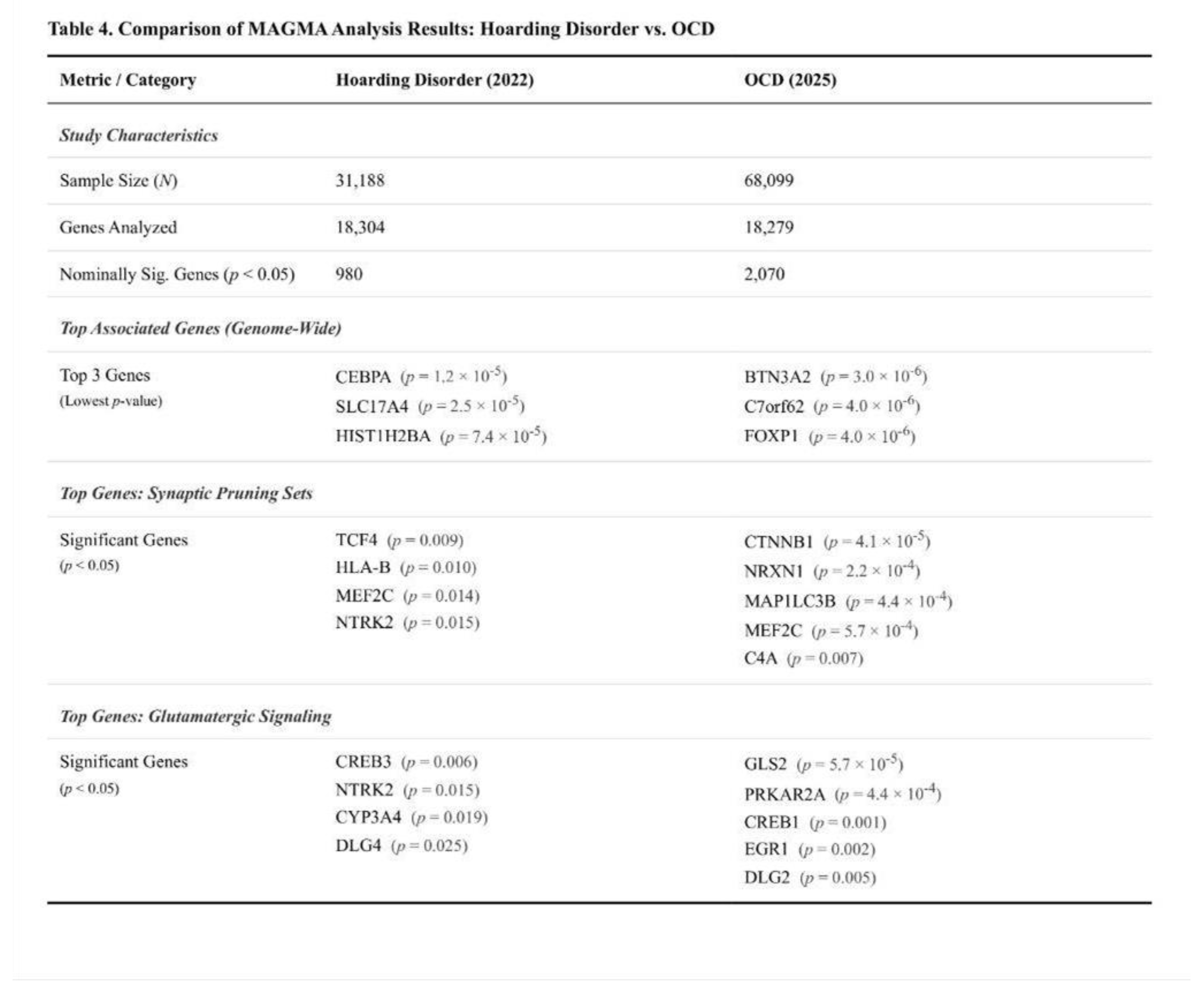

Collectively, the three complementary approaches—gene-based testing (

Table 4), stratified heritability (

Table 5), and brain-based TWAS—paint a nuanced picture of genetic overlap and divergence between hoarding symptoms and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Applying the identical analytic pipeline to the far larger 2025 OCD genome-wide meta-analysis [

12] offers an informative benchmark. The hoarding study, with an effective sample of roughly 31 000, is inevitably underpowered relative to the OCD scan (≈ 68 000 cases and controls), and this disparity is evident in weaker and noisier signals rather than a complete absence of association.

Pruning-related biology provides the clearest point of convergence. Both disorders show significant enrichment of common-variant signal within genes that regulate adolescent synaptic elimination, yet the magnitude differs. The critical (shortened) pruning panel in OCD explains about 1.32-fold more heritability than expected, compared with 1.19-fold in hoarding, and OCD shows much stronger distributional shifts in χ² statistics (

Table 4). In OCD, enrichment is driven chiefly by classical complement components, adhesion molecules and astrocytic regulators—loci that also contribute to schizophrenia and autism. Hoarding, by contrast, leans more on neurotrophic signalling, MHC class I processes and timing cues, hinting that altered reward or attachment circuitry may matter more than the cortico-striatal pruning defects highlighted in current OCD models. A modest positive genetic correlation (r_g ≈ 0.47, p ≈ 0.07) is therefore plausible but not definitive.

Glutamatergic pathways reveal the opposite pattern. Core glutamatergic targets display modest yet consistent enrichment in hoarding—especially genes mediating synaptic plasticity and sigma-regulated metabolic steps—whereas OCD shows little or no over-representation [

12]. TWAS reinforces this contrast: hoarding’s nominal associations cluster around plasticity drivers such as down-regulated NTRK2 in frontal cortex and mTOR components, whereas OCD’s signals appear in glutamate-metabolic enzymes and downstream kinase modules. These findings challenge the long-standing view that glutamatergic imbalance is primarily an OCD feature; instead, they suggest that decision-making and habit-learning networks implicated in hoarding may experience greater plasticity dysregulation.

Importantly, monoaminergic and housekeeping control panels remain null in both traits, supporting the specificity of the pruning and glutamate observations. Scattered immune and vascular hints in hoarding (e.g., CEBPA, CAV1/2) might represent peripheral influences distinct from OCD’s central synaptic-pruning emphasis, yet these require replication.

Taken together, the data endorse the current DSM-5 separation of hoarding disorder from OCD [

1] while also revealing a partially shared neurodevelopmental liability. OCD genetics converge strongly on excessive synaptic pruning within cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loops, whereas hoarding points toward disrupted plasticity and immune surveillance mechanisms. Larger, more diverse hoarding samples will be needed to confirm whether these contrasts reflect genuine etiological differences or simply the limits of present statistical power.

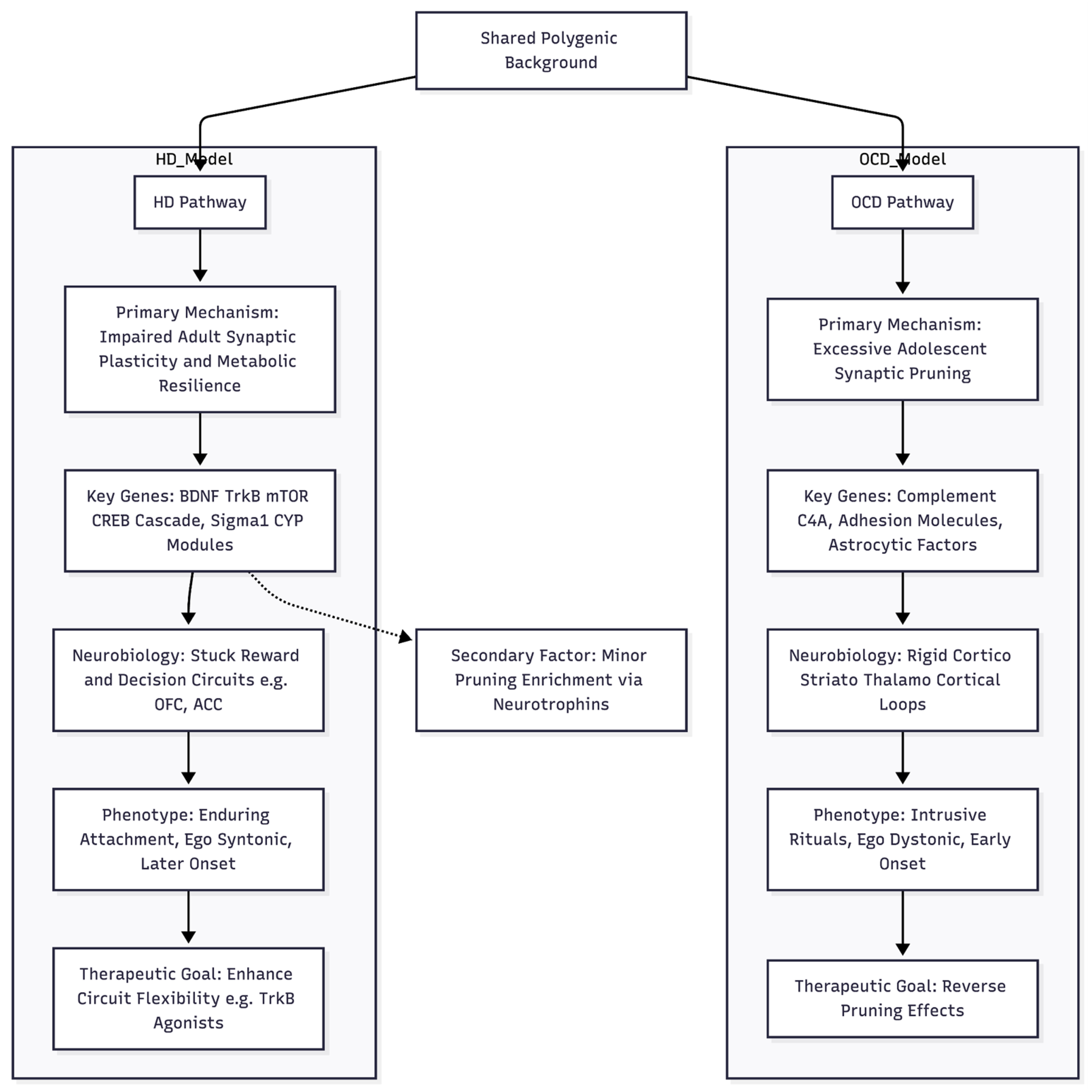

An Emerging Hypothesis for Hoarding Pathogenesis

Taken together, the current genomic results, even in the face of limited power, suggest that the biological roots of hoarding disorder may differ in important ways from the pruning-centred model now proposed for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) [

12] (

Figure 1). Whereas the OCD signal converges on activity-dependent synaptic elimination during late neurodevelopment—changes thought to stiffen cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loops and foster intrusive rituals—hoarding seems more closely tied to lifelong mechanisms of synaptic plasticity and cellular homeostasis. We therefore put forward an “under-plastic adaptation” model: common variants appear to concentrate in pathways that support ongoing synaptic remodelling and stress-responsive metabolic tuning. When these pathways falter, reward and decision circuits such as the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate and nucleus accumbens may struggle to update the emotional value of possessions.

Evidence for this view lies in the relative enrichment of glutamatergic and plasticity genes that is unique to hoarding. The focused glutamatergic panel accounts for more heritability here (1.08-fold raw; 1.27-fold after linkage-disequilibrium adjustment) and is depleted in OCD. Within that panel, a downstream plasticity subset shows the largest effect (1.79-fold, p ≈ 10⁻²⁴). Top nominal associations reinforce the theme: NTRK2 down-regulated in frontal cortex (Z = -2.95), mTOR pathway members, and scaffolding proteins such as DLG4. Sigma-1-receptor and CYP enzyme hits add a further layer of metabolic regulation. By contrast, pruning genes do contribute to hoarding but carry a different signature—stronger links to neurotrophin signalling, MHC class I surveillance and developmental timing, rather than the complement-tagging and adhesion focus seen in OCD [

12]. In hoarding, therefore, pruning may act as a secondary modifier rather than a primary driver.

This plasticity-centred profile fits clinical observations. Hoarding often begins later (mid-thirties), is usually ego-syntonic, and is closely tied to reward and habit circuits. Difficulty discarding may reflect a persistently high emotional weighting of objects when BDNF–mTOR pathways fail to revise salience in changing contexts. Metabolic hints—CYP enzymes, endoplasmic-reticulum stress genes—point to broader cellular resilience factors that have also been discussed in ageing research.

Twin data offer indirect support. Heritability for hoarding remains moderate in adulthood but is lower in adolescence and seems to decline with age [

8,

9]. Such a trend is consistent with liabilities that accumulate through impaired adult adaptation rather than fixed early wiring. Earlier candidate reports of SLC1A1 involvement [

11] likewise emphasise plasticity.

Therapeutic implications follow naturally. While OCD may benefit from agents that reverse excessive pruning—ketamine being an example—hoarding could respond better to drugs that enhance plasticity, such as TrkB agonists, mTOR activators, sigma-1 modulators or other glutamatergic regimens [

20,

21]. Coupling such agents with habit-focused behavioural work may help address the executive and learning deficits common in hoarding.

The caveat remains that hoarding samples are small; signals, though methodologically consistent, ride on a faint polygenic background. Nevertheless, their systematic contrast with OCD, together with long-standing clinical differences [

1], justifies further exploration of a plasticity–metabolic model. Larger, well-phenotyped hoarding cohorts will be needed to confirm whether plasticity deficits truly mark the disorder or merely reflect present limitations in statistical power.

Conclusion

The combined gene-based, stratified-heritability, and TWAS findings converge on a model in which hoarding disorder stems primarily from impaired adult synaptic plasticity and metabolic balance within reward- and decision-making networks. Unlike obsessive–compulsive disorder, whose common-variant risk is dominated by early synaptic pruning deficits [

12], hoarding shows its strongest enrichment in downstream glutamatergic cascades—particularly the BDNF‒TrkB‒mTOR‒CREB axis—and in sigma-1/CYP-mediated metabolic tuning.

This plasticity-centred perspective explains several long-standing clinical observations: the later average onset of hoarding, the largely ego-syntonic urge to acquire, and the frequent co-occurrence of executive-function problems. At the same time, the modest but reproducible enrichment for pruning genes clarifies why a partial genetic overlap with OCD is still observed.

Power limitations of the current hoarding GWAS temper the strength of any single signal; nevertheless, the internally consistent pattern across methods provides a coherent framework that supports the DSM-5 separation of hoarding disorder from OCD and suggests that treatment development should prioritise agents and behavioural strategies that enhance plasticity rather than those aimed at reversing excessive pruning. Future work with larger, well-phenotyped cohorts will be essential for testing and refining this hypothesis and for translating it into precision interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. .

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable. .

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Mataix-Cols, D.; Frost, R. O.; Pertusa, A.; et al. Hoarding disorder: A new diagnosis for DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety 2010, 27(6), 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertusa, A.; Frost, R. O.; Fullana, M. A.; et al. Refining the diagnostic boundaries of compulsive hoarding: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 2010, 30(4), 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, R. O.; Hartl, T. L. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1996, 34(4), 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolin, D. F.; Frost, R. O.; Steketee, G.; Fitch, K. E. Family burden of compulsive hoarding: Results of an internet survey. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2011, 46(3), 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cath, D. C.; Nizar, K.; Boomsma, D.; Mathews, C. A. Age-Specific Prevalence of Hoarding and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Population-Based Study. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry 2017, 25(3), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordsletten, A. E.; Reichenberg, A.; Hatch, S. L.; et al. Epidemiology of hoarding disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 2013, 203(6), 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iervolino, A. C.; Perroud, N.; Fullana, M. A.; et al. Prevalence and heritability of compulsive hoarding: A twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 166(10), 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, V. Z.; Nordsletten, A.; Mataix-Cols, D.; et al. Heritability of hoarding symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. PLOS ONE 2017, 12(6), e0179541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strom, N. I.; Smit, D. J. A.; Silzer, T.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of hoarding symptoms in 27,537 individuals. Translational psychiatry 2022, 12(1), 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendland, J. R.; Moya, P. R.; Timpano, K. R.; et al. A haplotype containing quantitative trait loci for SLC1A1 gene expression and its association with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 2009, 66(4), 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. (2025a). Rethinking OCD etiology: Convergent genetic findings in pruning pathways point to a neurodevelopmental paradigm shift [Preprint]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Finucane, H. K.; Anttila, V.; et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nature Genetics 2015a, 47(11), 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulik-Sullivan, B. K.; Loh, P.-R.; Finucane, H. K.; et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nature Genetics 2015b, 47(3), 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strom, N. I.; Gerring, Z. F.; Galimberti, M.; et al. Genome-wide analyses identify 30 loci associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. medRxiv 2025, 2024.03.13.24304161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, C. A.; Mooij, J. M.; Heskes, T.; Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Computational Biology 2015, 11(4), e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, H. K.; Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Gusev, A.; et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nature Genetics 2015, 47(11), 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, A. N.; Pividori, M.; Zheng, J.; et al. Integrating predicted transcriptome from multiple tissues improves association detection. PLOS Genetics 2019, 15(1), e1007889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369(6509), 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, B.; Bunn, H.; Santalucia, M.; et al. Dextromethorphan-bupropion (Auvelity) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 2023, 21(4), 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. (2025b). An oral ketamine-like approach to treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: Rationale and early clinical experience with the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen. Preprints. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).