1. Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a highly successful procedure for alleviating pain and restoring function in patients with end-stage knee osteoarthritis [

1]. The demand for TKA is projected to continue rising, driven by an aging population and the escalating prevalence of obesity [

2]. Severe obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m

2) is a significant concern in this context, as it is independently associated with a higher risk of postoperative complications, including periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), aseptic loosening, and increased revision rates [

3,

4,

5]. The mechanical environment of the knee is profoundly altered by excess body mass, where every step can generate forces several times the body’s weight across the joint [

6]. This excessive and repetitive loading is a primary driver for the wear of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) components, a key factor in the long-term failure of TKA implants through mechanisms of osteolysis and aseptic loosening [

7,

8].

Consequently, weight management is a critical component of care. Bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective intervention for achieving substantial and sustained weight loss in individuals with severe obesity [

9]. Numerous studies, including randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses, have demonstrated that bariatric surgery performed prior to TKA can significantly reduce the risk of postoperative complications, particularly PJI [

10,

11,

12]. More recently, the advent of GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide, tirzepatide) has introduced a powerful new pharmacological option for medical weight management, with studies showing their use is associated with improved postoperative outcomes and lower complication rates after TKA [

13,

14].

While the benefits of pre-arthroplasty weight loss are well-documented, there is a paucity of data on the longitudinal biomechanical changes in patients who undergo massive weight loss after a TKA, once their initial rehabilitation is complete and their gait patterns have consolidated. Understanding these changes is crucial. Does the neuromuscular system adapt to the new, lighter body, or do established motor patterns persist? Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) provide a practical, reliable, and ecologically valid method for quantifying gait mechanics outside of a traditional laboratory, enabling detailed assessment of spatiotemporal parameters, kinematics, and kinetics [

15,

16,

17].

This case report is unique in its use of wearable inertial sensor technology to longitudinally track the functional and biomechanical outcomes of a patient who underwent bariatric surgery after having already completed the initial 6-month recovery from a unilateral TKA. We aimed to quantify the impact of a 42.5% body mass reduction on an established gait pattern, testing the hypothesis that motor programs for walking exhibit significant plasticity but can also show remarkable stability, particularly when a pattern has been ingrained post-rehabilitation [

18,

19].

2. Case Presentation

The patient is a 62-year-old male (height: 167 cm) who underwent a primary unilateral left TKA for debilitating osteoarthritis. At 6 months post-TKA (T1), his body mass was approximately 120 kg (BMI ≈ 43 kg/m2, Class III Obesity). Between the 6-month and 12-month follow-up appointments, the patient underwent bariatric surgery, resulting in a body mass of 69 kg (BMI ≈ 25 kg/m2, Normal) at the 12-month assessment (T2). The patient was independently mobile and did not use any assistive devices at either assessment point. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for this report.

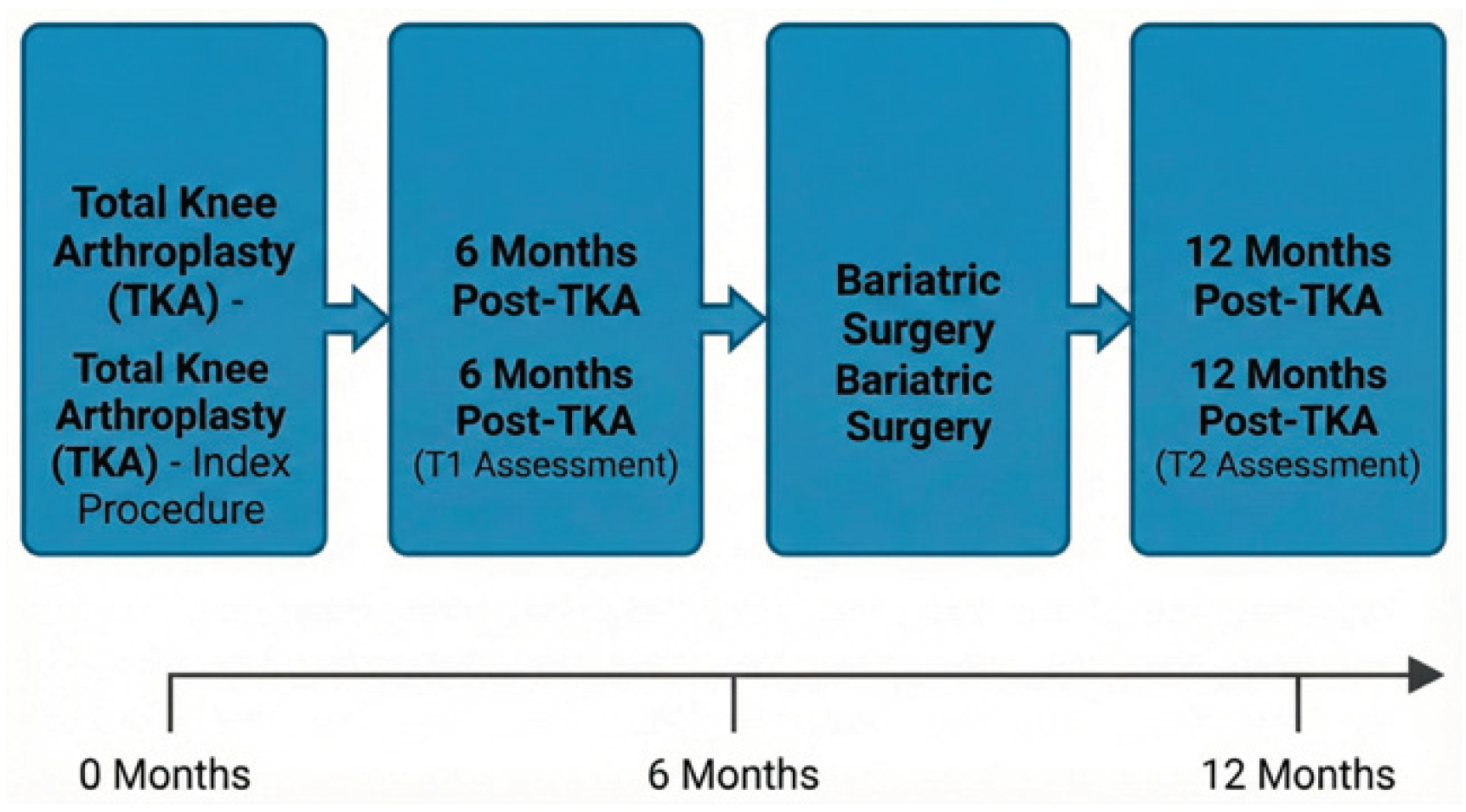

2.1. Timeline

The sequence of interventions and assessments is summarized in

Figure 1. The patient underwent left TKA at month 0, followed by the first gait assessment (T1) at 6 months post-operatively. Bariatric surgery was performed between 6 and 9 months post-TKA, and the second gait assessment (T2) was conducted at 12 months post-TKA.

2.2. Clinical Findings

Objective gait analysis was performed using the G-Walk inertial sensor system (BTS Bioengineering), with the sensor placed on the lower back (L5). Assessments included a standard walk test, a Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, and a Two-Minute Walk Test (2MWT).

2.3. Functional Mobility and Endurance

Functional tests showed remarkable stability across both time points despite the massive weight loss. The TUG test was completed in 14.95 seconds at both T1 and T2. The distance covered in the 2MWT was also identical at 105.1 meters, with an average walking speed of 1.11 m/s.

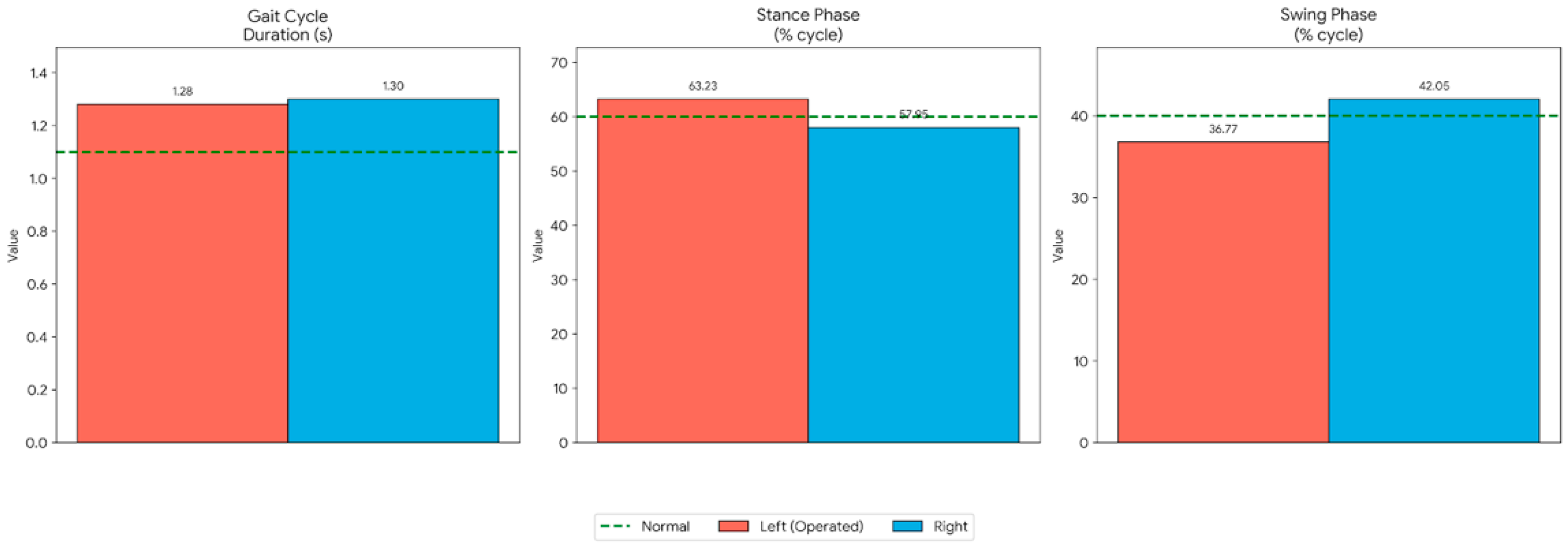

2.4. Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters

The core spatiotemporal parameters of the patient’s gait were unchanged between T1 and T2. A persistent asymmetry was noted,

Figure 2, with the operated (left) limb demonstrating a longer stance phase (63.23 ± 0.94%) compared to the non-operated (right) limb (57.95 ± 2.30%). Correspondingly, the swing phase,

Table 1, of the left limb was shorter (36.77 ± 0.94%) than the right (42.05 ± 2.30%), suggesting a stability-oriented strategy on the operated side.

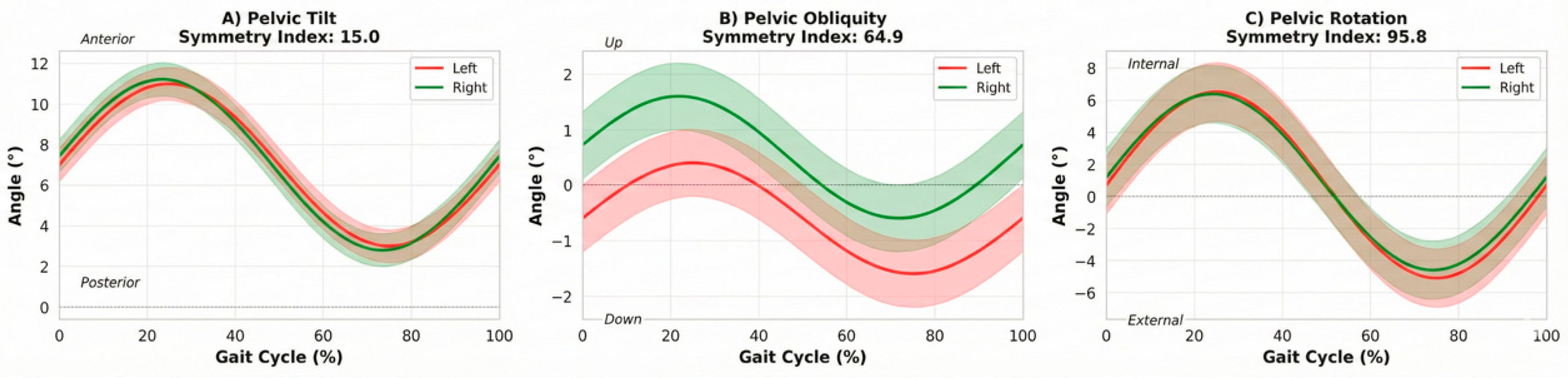

2.4. Pelvic Kinematics

Pelvic motion, a proxy for trunk control during gait, showed high consistency. Pelvic rotation symmetry was excellent (symmetry index 95.8), while obliquity (64.9) and tilt (15.0) showed lower symmetry indices, suggesting subtle compensatory movements in the frontal and sagittal planes.

Figure 3.

Pelvic kinematics during the gait cycle. (A) Pelvic tilt, (B) pelvic obliquity and (C) pelvic rotation obtained from the G-Walk system. Rotation symmetry was excellent (symmetry index 95.8), while obliquity exhibited moderate symmetry (64.9) and tilt showed a lower symmetry index (15.0), suggesting subtle sagittal plane compensations.

Figure 3.

Pelvic kinematics during the gait cycle. (A) Pelvic tilt, (B) pelvic obliquity and (C) pelvic rotation obtained from the G-Walk system. Rotation symmetry was excellent (symmetry index 95.8), while obliquity exhibited moderate symmetry (64.9) and tilt showed a lower symmetry index (15.0), suggesting subtle sagittal plane compensations.

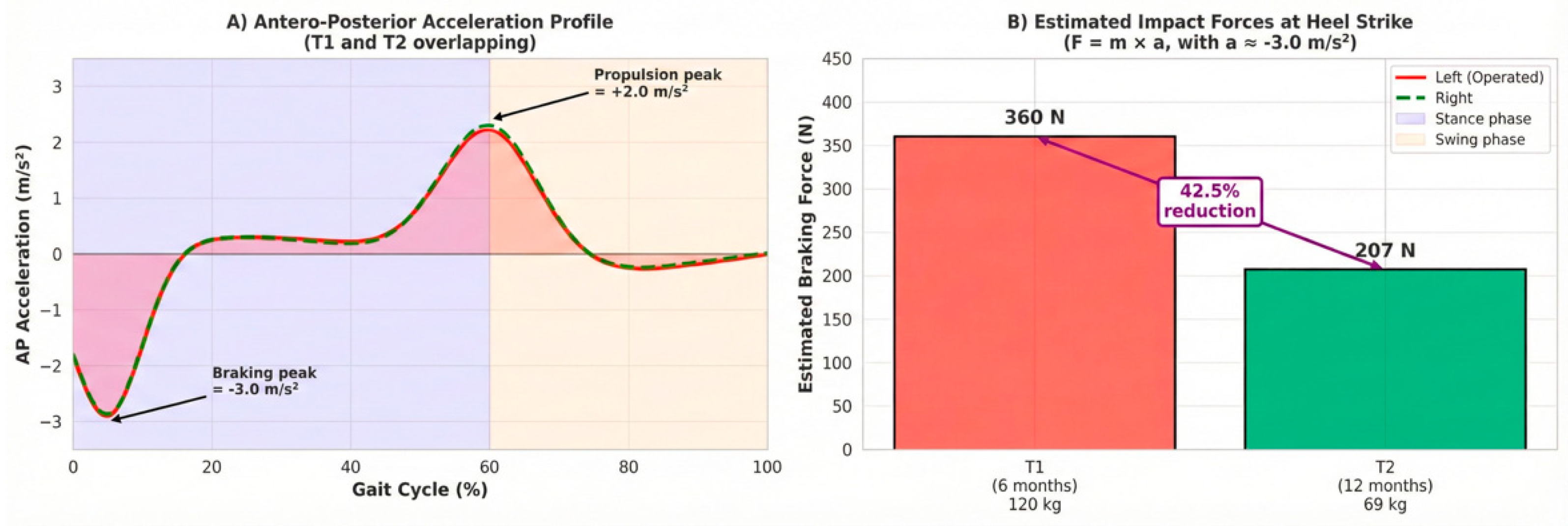

2.4. Diagnostic Assessment

Antero-posterior (AP) acceleration data were used to estimate impact forces at the knee. The peak negative acceleration during the loading response (braking phase) was consistently measured at approximately −3.0 m/s

2 at both T1 and T2. Assuming comparable acceleration magnitudes, the reduction in body mass resulted in a proportional decrease in estimated braking forces (

Figure 4).

2.5. Therapeutic Intervention

The index intervention was a primary unilateral left total knee arthroplasty. Bariatric surgery was performed between T1 and T2, leading to a 51 kg (42.5%) reduction in body mass by the 12-month follow-up.

2.6. Follow-Up and Outcomes

Using the formula F = m × a and the measured braking acceleration magnitude (~3.0 m/s

2), the estimated braking force at heel strike was ~360 N at T1 (120 kg) and ~207 N at T2 (69 kg), representing a ~42.5% reduction in mechanical loading on the knee during the loading phase of gait.

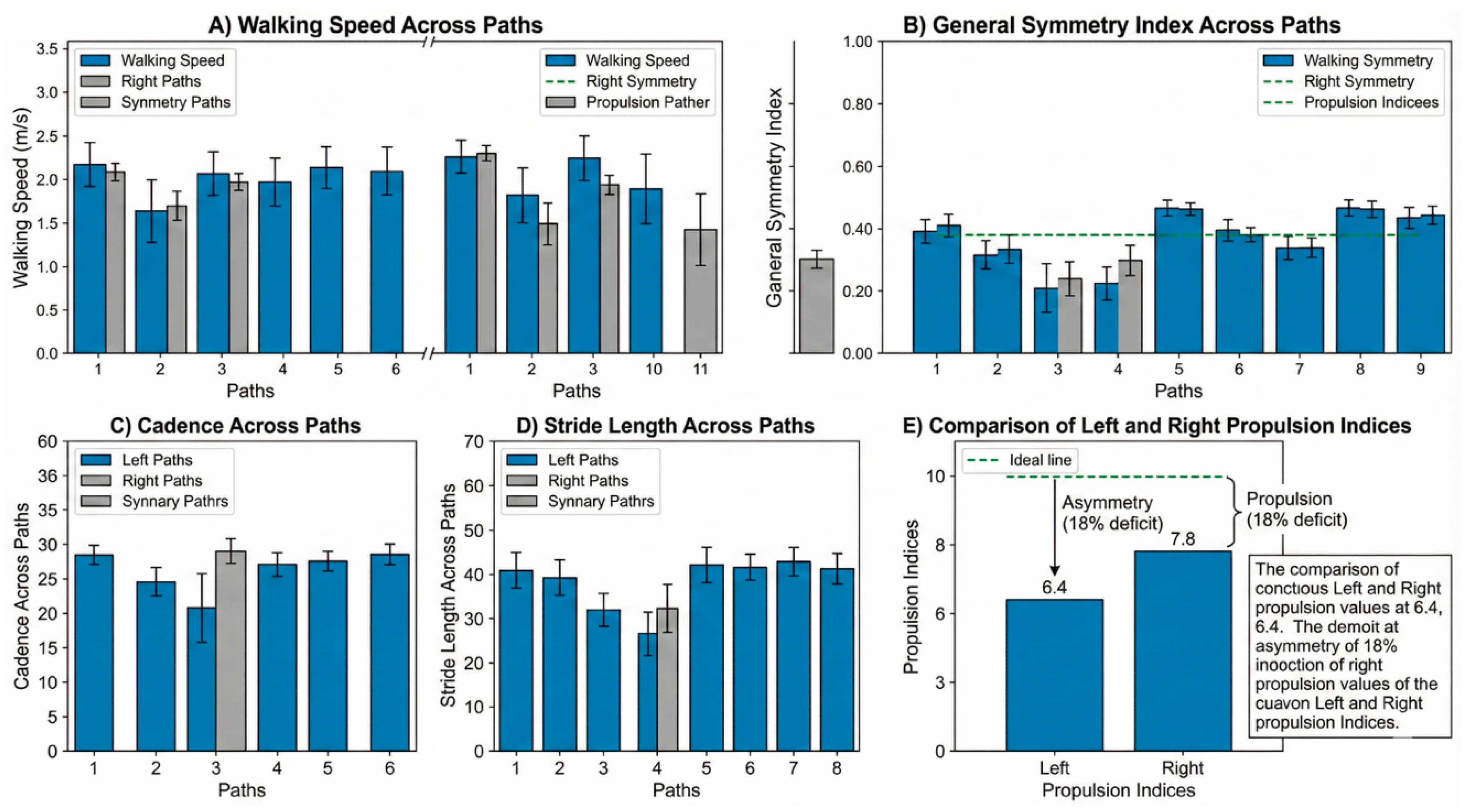

Figure 5.

Inertial-sensor analysis of the 2-minute walk test. (A) Walking speed across the 11 paths shows relatively stable values around the average speed of 1.11 m/s. (B) The general symmetry index remains high throughout the test (mean 97.8%). (C) Cadence across paths. (D) Stride length across paths. (E) Propulsion indices derived from the Walk Test. The operated left limb shows a consistently lower propulsion index (6.4) compared with the right limb (7.8), indicating a persistent but stable deficit in forward power generation during push-off.

Figure 5.

Inertial-sensor analysis of the 2-minute walk test. (A) Walking speed across the 11 paths shows relatively stable values around the average speed of 1.11 m/s. (B) The general symmetry index remains high throughout the test (mean 97.8%). (C) Cadence across paths. (D) Stride length across paths. (E) Propulsion indices derived from the Walk Test. The operated left limb shows a consistently lower propulsion index (6.4) compared with the right limb (7.8), indicating a persistent but stable deficit in forward power generation during push-off.

Table 2.

Summary of functional tests and body composition changes.

Table 2.

Summary of functional tests and body composition changes.

| Test/Parameter |

T1

(6 months)

|

T2

(12 months)

|

Interpretation |

| TUG Duration (s) |

14.95 |

14.95 |

Stable—Independent mobility |

| 2MWT Distance (m) |

105.1 |

105.1 |

Stable endurance |

| Walking Speed (m/s) |

1.11 |

1.11 |

Slightly below normal range |

| Gait Symmetry (%) |

94.1 |

94.1 |

High symmetry maintained |

| Body Mass (kg) |

~120 |

69 |

42.5% reduction |

| Estimated Impact Force (N) |

~360 |

~207 |

42.5% mechanical offloading |

| Propulsion Index (L/R) |

6.4/7.8 |

6.4/7.8 |

18% deficit in operated limb |

3. Discussion

This case report provides a unique insight into the effects of massive weight loss on a consolidated post-TKA gait pattern, expanding on several key areas of contemporary orthopedic science. The discussion is structured around four central themes: the stability of motor patterns, the clinical implications of mechanical offloading, the role of bariatric surgery in the TKA patient journey, and the utility of wearable technology in modern orthopedic practice.

3.1. Stability Of Motor Patterns and Neuroplasticity

The most striking finding is the profound stability of the patient’s functional scores and kinematic parameters. The TUG, 2MWT, walking speed, and spatiotemporal asymmetries remained virtually identical between T1 and T2, despite a 42.5% reduction in body mass. This observation lends strong support to the concept of motor program stability. Once a walking pattern is established and practiced over thousands of repetitions during the initial 6-month post-TKA rehabilitation, it becomes a deeply ingrained program within the central nervous system [

18,

20].

The work by Hortobágyi et al. [

19] on “mechanical plasticity” demonstrated that while massive weight loss does induce kinematic and kinetic changes, certain fundamental characteristics of the gait signature can persist [

19]. Our findings suggest that in a post-surgical context, where a specific rehabilitation protocol has already shaped the recovery trajectory, the established motor pattern is highly resilient to subsequent changes in body mass. The neuromuscular system appears to default to the previously learned, efficient pattern of movement, even when the mechanical demands have been significantly altered [

21,

22]. This has implications for rehabilitation, suggesting that early and correct motor pattern training post-TKA is critical, as these patterns may be long-lasting.

3.2. Mechanical Offloading and Prosthesis Survivorship

The key clinical finding is the substantial mechanical offloading of the prosthetic joint. The 42.5% reduction in estimated impact force is a direct, proportional consequence of the mass reduction, as the acceleration profile (the kinematic component) remained unchanged. This is of paramount clinical significance. Excessive and repetitive loading is a primary risk factor for the long-term failure of TKA components, specifically through polyethylene wear, which leads to particle-induced osteolysis and subsequent aseptic loosening [

7,

8,

23].

Studies have consistently shown that higher BMI is correlated with increased rates of aseptic loosening and mechanical failure [

5,

24]. By drastically reducing the mechanical load with every step, the bariatric surgery has likely improved the long-term survivorship prognosis for the patient’s knee prosthesis [

25,

26]. This mechanical relief, achieved without altering the fundamental gait kinematics, suggests that the primary benefit of late-stage weight loss is the direct reduction of cumulative stress on the implant, a factor critical for its longevity [

27].

3.3. The Role of Bariatric Surgery and Weight Management in TKA

This case highlights the synergistic relationship between bariatric surgery and TKA. While the ideal timing remains a subject of debate, the benefits are clear. Performing bariatric surgery before TKA is associated with fewer perioperative complications, particularly infections [

10,

11]. However, this case demonstrates a powerful argument for weight loss even after TKA. The significant reduction in joint loading can be framed as a long-term protective measure for the implant.

The emergence of highly effective anti-obesity medications, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, provides another promising avenue. Recent studies indicate that medically induced weight loss is also associated with a lower risk of revision surgery and improved outcomes, offering a less invasive alternative to bariatric surgery for many patients [

13,

14,

28]. The decision for weight management, whether surgical or medical, should be a central part of the conversation with any obese patient undergoing TKA, regardless of the timing.

3.4. Utility Of Wearable Sensors In Clinical Practice

This study underscores the value of using IMU-based wearable sensors for objective gait analysis in a clinical setting. Traditional functional tests like the TUG and 2MWT, while useful, failed to capture the most critical change in this patient: the massive reduction in joint loading. These tests showed stability, which could have been misinterpreted as a lack of change. The inertial sensor, however, provided the kinematic data (acceleration) that, when combined with the known change in mass, revealed the profound kinetic improvement.

As wearable technology becomes more accessible, validated, and user-friendly, it offers clinicians a powerful tool to look beyond simple timed metrics and gain deeper insights into the quality of movement and the biomechanical forces at play, allowing for more personalized and effective patient management [

15,

16,

29,

30].

This is a single-patient case report, and the impact force calculation is an estimation based on acceleration. However, the use of a validated inertial sensor system provides objective, reproducible data that strengthens the clinical observations and generates important hypotheses for future, larger-scale studies.

4. Conclusions

In a patient with a stable functional recovery 6 months after TKA, subsequent massive weight loss via bariatric surgery did not alter the established kinematic gait patterns. However, it resulted in a profound and proportional reduction in the mechanical forces acting on the knee joint. This case demonstrates that the primary benefit of late-stage weight loss in the post-TKA population may be the significant biomechanical offloading of the prosthesis, rather than an immediate change in functional mobility scores. This highlights the synergistic potential of combining TKA and weight management strategies, whether surgical or medical, to optimize long-term joint health and implant survivorship.

Author Contributions

This case report was conducted through a collaborative effort among all authors. Author AMVT conceived and designed the study, coordinated the longitudinal follow-up, and led the development of the clinical and instrumented gait assessment protocol using the wearable inertial sensor approach. Author LPR contributed to data acquisition and organization, supported the execution of the functional tests and gait assessments, and assisted in drafting the manuscript. Author RBP contributed to data curation, assisted with the preparation of figures/tables and interpretation of spatiotemporal outcomes, and revised the manuscript for methodological consistency. Author CS provided clinical oversight of the orthopedic case context and contributed to the critical appraisal of the clinical narrative and interpretation of findings. Author CSO supervised the project, reviewed the methodological and analytical approach, and provided critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere appreciation to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Evangelical University of Goiás (UniEVANGÉLICA), and the Goiás State Research Support Foundation (FAPEG) for their contribution to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Consent

All authors declare that written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editorial office of this journal.

Ethical Approval

The present study complies with the ethical guidelines and regulatory standards for research involving human beings established by the Brazilian National Health Council (Ministry of Health), originally issued in October 1996 and updated by Resolution No. 466/2012. The study was conducted after approval by the Research Ethics Committee under protocol number 6.775.127 and CAAE number 52052421.9.0000.5076. This is a prospective, observational, and comparative study, and all participants provided written informed consent, acknowledging that participation was voluntary, free of charge, and involved procedures of an experimental nature. Participants received all relevant information and were allowed to withdraw from the study or revoke their consent at any time without prejudice or harm. Absolute confidentiality of participants’ identities was ensured in accordance with ethical principles of confidentiality and privacy. The study was carried out at a tertiary referral hospital specializing in rehabilitation, in partnership with a private university in the interior of Goiás, Brazil, which provided adequate technical infrastructure and institutional support to ensure successful completion of the project, including a fully equipped motion analysis laboratory and a portable, wireless G-Walk inertial sensor (BTS Bioengineering S.p.A., Italy).

Abbreviations

| TKA |

Total Knee Arthroplasty. |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index. |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go (test). |

| 2MWT |

Two-Minute Walk Test. |

| IMU/IMUs |

Inertial Measurement Unit(s). |

| AP |

Antero-posterior. |

| PJI |

Periprosthetic Joint Infection. |

| UHMWPE |

Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. |

| GLP-1 |

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (as “GLP-1 receptor agonists”). |

| CNPq |

National Council for Scientific and Technological Development. |

| FAPEG |

Goiás State Research Support Foundation. |

| HMAP |

Municipal Hospital of Aparecida de Goiânia. |

| T1 |

First assessment time point (6 months post-TKA). |

| T2 |

Second assessment time point (12 months post-TKA). |

| L5 |

Fifth lumbar vertebra level (sensor placement site on the lower back). |

| kg/cm/m |

Kilogram/centimeter/meter (units used for body mass, height, and distance). |

| s/min |

Seconds/minutes (units used for test duration and cadence). |

| m/s/m/s2

|

Meters per second (speed)/meters per second squared (acceleration). |

| N |

Newton (force unit used for estimated braking force). |

| L/R |

Left/Right (used to report limb-specific indices). |

References

- Sivaram J et al. 2024 Long term Assessment of Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life in TKA J Pak Med Assoc. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz SM Ong KL Lau E Mowat F Halpern M 2007 Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030 J Bone Joint Surg Am . [CrossRef]

- Uvodich ME Dugdale EM Pagnano MW Berry DJ Abdel MP Bedard NA 2024 Outcomes of Obese Patients Undergoing Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty Trends Over 30 Years J Bone Joint Surg Am. [CrossRef]

- Rahman A et al. 2025 Impact of Obesity on Joint Replacement Surgery Outcomes PMC. [CrossRef]

- Firoozabadi MA et al. 2024 Does body mass index BMI significantly influence aseptic loosening in primary total knee arthroplasty BMC Musculoskelet Disord. [CrossRef]

- Adouni M et al. 2024 Effects of overweight and obesity on lower limb walking characteristics from joint kinematics to muscle activations Gait Posture. [CrossRef]

- Jones MD Buckle CL 2020 How does aseptic loosening occur and how can we prevent it Orthop Trauma. [CrossRef]

- Diconi AF et al. 2025 The Effects of Biomechanical Loading on the Tibial Insert in TKA J Arthroplasty. [CrossRef]

- Maman D Grinberg D Ginesin E Khatib M Kadar A Keren Y 2025 Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Postoperative Outcomes Complications and Revision Rates in Total Knee Arthroplasty A Big Data Analysis J Clin Med. [CrossRef]

- Dowsey MM Brown WA Cochrane A Burton PR Choong PF 2022 Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Risk of Complications After Total Knee Arthroplasty A Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Netw Open. [CrossRef]

- Liu P Meng J Tang H Xiao Y Li X Wu Y et al. 2025 Association between bariatric surgery and outcomes of total joint arthroplasty a meta analysis Int J Surg. [CrossRef]

- Lau LCM et al. 2024 Preoperative weight loss interventions before total hip and knee arthroplasty a systematic review J Orthop Surg Res. [CrossRef]

- Lee S et al. 2025 The Impact of Glucagon Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Use on Outcomes Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty J Arthroplasty. [CrossRef]

- Xie D et al. 2025 Postoperative Weight Loss and Revision Risk After Joint Arthroplasty JAMA Netw Open. [CrossRef]

- Gianzina E Kalinterakis G Delis S Vlastos I Sachinis NP Yiannakopoulos CK 2023 Evaluation of gait recovery after total knee arthroplasty using wearable inertial sensors A systematic review Knee. [CrossRef]

- Boekesteijn RJ van Gerven J Geurts ACH Smulders K 2022 Objective gait assessment in individuals with knee osteoarthritis using inertial sensors A systematic review and meta analysis Gait Posture. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y Liu Y Fang Y Chang J Deng F Liu J Xiong Y 2023 Advances in the application of wearable sensors for gait analysis after total knee arthroplasty a systematic review Arthroplasty. [CrossRef]

- Malatesta D et al. 2022 Effect of very large body mass loss on energetics mechanics and efficiency of walking in adults with obesity J Physiol. [CrossRef]

- Hortobágyi T Herring C Pories WJ Rider P DeVita P 2011 Massive weight loss induced mechanical plasticity in obese gait J Appl Physiol. [CrossRef]

- Christensen JC et al. 2023 Recovery Curve for Patient Reported Outcomes and Gait Speed After TKA J Arthroplasty. [CrossRef]

- Gill SV Walsh MK Pratt JA Tober JN Huynh NN Spaulding SJ 2016 Changes in spatio temporal gait patterns during flat ground walking and obstacle crossing 1 year after bariatric surgery Surg Obes Relat Dis. [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen P Bragge T Lyytinen T Hakkarainen M Karjalainen PA Arokoski JP 2012 Kinematic and kinetic changes in obese gait in bariatric surgery induced weight loss J Biomech. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm SK Henrichsen JL Siljander M Moore DD Karadsheh MS 2018 Polyethylene in total knee arthroplasty Where are we now J Orthop Surg Hong Kong. [CrossRef]

- van Duren BH et al. 2025 Revision Rates for Aseptic Loosening in the Obese Patient Arthroplasty Today. [CrossRef]

- Chang JS Haddad FS 2020 Long term survivorship of hip and knee arthroplasty Bone Joint J 102 B 4. [CrossRef]

- Bistolfi A et al. 2024 Vitamin E stabilized polyethylene shows similar survival rates in TKA J Exp Orthop. [CrossRef]

- Patoz A et al. 2023 The effect of severe obesity on three dimensional ground reaction forces J Biomech. [CrossRef]

- Mayfield CK Mont MA Lieberman JR et al. 2024 Medical weight optimization for arthroplasty patients a primer of emerging therapies for the joint arthroplasty surgeon J Arthroplasty. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari A et al. 2025 Monitoring Gait Recovery After Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Wearable Sensors J Orthop Res. [CrossRef]

- Guild GN III et al. 2024 Evaluating Knee Recovery Beyond Patient Reports Sensor derived Gait Metrics J Arthroplasty. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).