1. Introduction

In recent decades, climate variability and climate change have been central topics in numerous scientific studies. Global climate change, driven by both natural processes and anthropogenic influences, represents a major environmental challenge of the twenty-first century [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Increased attention from governments, the scientific community, and the general public underscores the urgency of understanding these changes and their effects [

6,

7]. Temperature fluctuations, the rate of change, and associated phenomena such as rising sea levels, floods, droughts, and aridity underscore the broader implications of climate change [

8]. Seasonal analyses reveal a consistent warming trend in near-surface air temperatures, with the most pronounced increase occurring during winter [

5].

Aridity plays a crucial role in understanding climatic conditions and natural processes, serving as both an indicator of plant growth and a determinant of landscape characteristics. Evaluation of the aridity can be managed through the widely used specific climatic parameters. Parameters in which there is a defined relationship between air temperature and precipitation are known as “aridity indices” and represent a useful tool in their quantification [

9]. However, formulation of aridity indices is not straightforward due to the nature of aridity. Use of mean annual precipitation as an index of aridity ignores the importance of air temperature and evaporation. Aridity indexes that have gained widespread acceptance directly or indirectly take into account all three factors [

10].

To quantify aridity, numerous climatic indices have been formulated, generally calculated as a ratio between some specific cli¬matic indicators. For example, the Lang Rain Factor [

11], De Martonne Aridity Index [

12], Emberger Aridity Index [

13], Gračanin’s rain factor for the vegetation period (1950) [

14], Seljanin’s hydrothermal coefficient (1958) [

15], Erinç aridity index (Erinç, 1965) [

16] and Pinna Combinative Aridity Index (Zambakas, 1992) [

17] are calculated as the ratio of precipitation and air temperature. Since these indices are derived from different climatic variables (calculated at monthly, annual scale, vegetation period), they provide heterogenous perspectives in aridity analysis. Also, there are some different approaches in determining aridity such as: Thornthwaite aridity index (1948) [

18], Budyko’s equation (1951) [

19], UNESCO aridity index (UNESCO, 1979) [

20] and FAO aridity index (FAO, 1989) [

21]. Thornthwaite (1948) [

18] introduced an aridity index as the ratio between annual precipitation and potential evapotranspiration. A few years later, Budyko (1951) [

19] offered a new approach by considering the heat and water balance equations of the Earth’s surface. The Radiational Index of Dryness (RID) was the ratio of the mean annual net radiation (i.e. the radiation balance) to the product of the mean annual precipitation times the latent heat of vaporization for water. The UNESCO aridity index is based on the ratio of average annual precipitation to potential evapotranspiration. This index, originally developed by UNESCO (1979) [

20] to map drylands, remains a widely used tool for assessing and projecting global aridity and its impacts. The FAO Aridity Index (1989) [

21] measures a region's dryness by calculating the ratio of annual precipitation to potential evapotranspiration. This index is a critical tool for assessing moisture availability, managing land resources for agriculture, and understanding the long-term impacts of climate change on water resources and drylands.

Furthermore, some other indices, such as the Johansson Continentality Index and the Kerner Oceanity Index, differentiate continental and maritime climate [

22,

23]. Recent advances in the archiving and collection of data have allowed worldwide monitoring of aridity as opposed to hindsight assessments. The most commonly used satellite measure is the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). The assessment of aridity changes using remote sensing like NDVI measures vegetation greenness, which declines in dry conditions. However, this requires images of medium-high spatial resolution over a long period of time and high-quality data derived from Landsat [

10,

24].

Since the 1950s, aridity has increased across most of the Earth’s surface, a trend intensified by the ongoing effects of global warming induced by anthropogenic activities [

25]. Sardans et al. (2024) [

26] concluded that from 1960 to 2023, 27.9% of the global land surface became significantly more arid, while 20.5% became significantly less arid. This indicates a shift towards drier climates, with humid, semi-humid, and semi-arid areas decreasing by 8.51, 1.45, and 0.53 million-km², respectively, and arid and hyper-arid areas increasing by 6.34 and 4.18 million-km², respectively. Especially vulnerable regions on global scale according to this study are Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. The spatio-temporal dynamics and variability of the aridity was investigated in details on regional scale: Greece [

27,

28,

29], Italy [

30,

31], the Iberian Peninsula [

32,

33], Turkey [23.34], Algeria [

35], the Middle East [

36], Lebanon [

37], Iran [

38,

39] and Iraq [

40]. Thornthwaite (1948) [

18] introduced an aridity index as the ratio between annual precipitation and potential evapotranspiration. Other indices, such as the Johansson continentality index and the Kerner oceanity index, differentiate between continental and oceanic climates [

22,

23].

Additionally, Mărgărit-Mircea (2021) [

41] used the Johansson Index of Continentality, the Kerner Index of Oceanity, the De Martonne Aridity Index, the Pinna Combinative Index and the UNEP Aridity Index. This study determined that the Southeastern Europe, the Balkan Peninsula, the Iberian Peninsula, the Apennine Peninsula, and Mediterranean islands consistently exhibit a dry climate according to all indices. Also, Beštáková et al. (2023) [

42] assessed the spatial distribution of arid and humid regions in Europe using the Aridity Index (1950–2019) identifying the Balkan Peninsula as predominantly arid. Numerous authors dealt with aridity occurrence in the Balkan countries, for instance in Serbia (e.g., [

43,

44,

45,

46]), Montenegro [

47], Croatia [

48,

49], Romania (e.g. [

50,

51,

52]), Bulgaria [

53].

However, it is difficult to identify similar and robust aridity research on national scale. Aridity in North Macedonia has been examined by using FAO Aridity Index in Agro-Ecological Atlas of North Macedonia [

54]. In this study, authors revealed the classes of semi-arid and dry sub-humid climate. These two classes delineate most of the agriculture areas in the central and southeast part of the country, which covers the driest areas. On the other hand, the humid class covers also some important agriculture areas in the western part of the country with more humid climatic condition. Recent studies indicate increasing of the future aridity conditions (RCP8.5 scenario) in the Southeastern Europe, including territory of North Macedonia. The Balkan Peninsula, including North Macedonia, has experienced a moderate increase in extreme climate events, particularly since the 1980s [

55]. Additionally, aridity trends are interpreted within the broader context of paleoclimatic phenomena, particularly those occurring during the Middle and Late Pleistocene. Carvalho et al. (2022) [

56] suggest strong reduction of Aridity Index for South and Southeastern Europe (2081-2100). Furthermore, [

57,

58] observed semy-dry conditions (2071-2100) according to De Martonne classes in central, south and southeastern parts of North Macedonia. The lack of adequate recent studies and above-mentioned facts justify the importance of reseach the spatio-temporal aridity patterns in North Macedonia.

For the purpose of this study, the Johansson Continentality Index, the De Martonne Aridity Index and the Pinna Combinative Index were selected as the most suitable tools for analyzing spatio-temporal conditions in North Macedonia. These climate indices were calculated using air temperature and precipitation data from 13 meteorological stations over a 30-year standard climatological interval (1991-2020) providing insight into the aridity dynamics on national scale. By examining climate data spanning several decades, this research aims to provide valuable insights into the region’s recent climate variability. Additionally, the objectives of this study are: (1) to analyze and discuss the trend characteristics of selected climate indices in details using Mann-Kendall non-parametric test; (2) to quantify the significance of changes on monthly, seasonal and annual scale; (3) to provide insight into spatial changes of indices using GIS tools and suitable interpolation technique, (4) to correlate our findings with the North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAOI) and Southern Oscillation Index (SOI). By evaluating long-term trends and identifying regional climate shifts, this research contributes to the broader understanding of climate variability and its potential impacts on natural ecosystems and human societies.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Pettitt’s homogeneity test

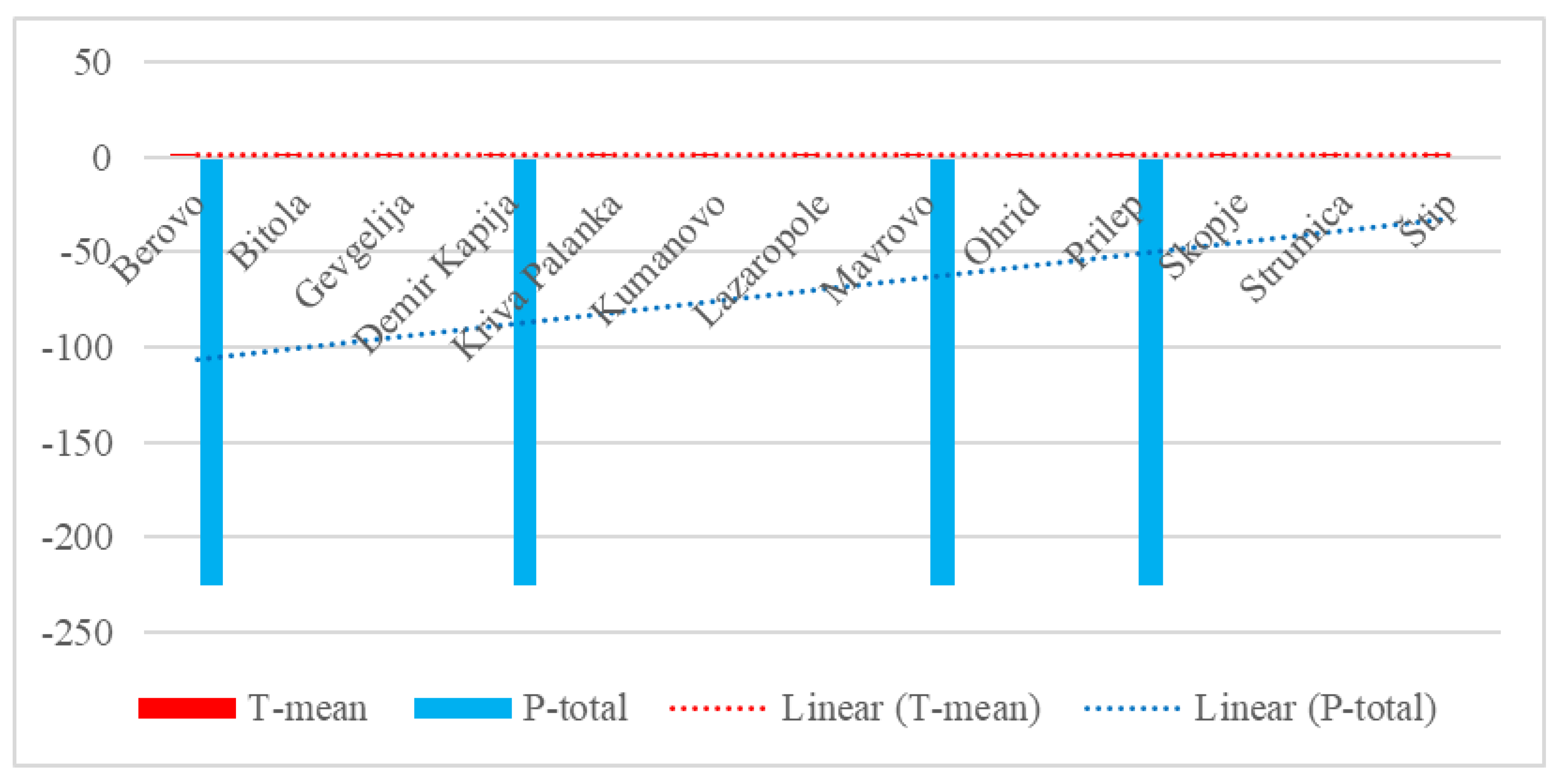

Before all calculation procedures the Pettitt’s homogeneity test was performed (

Figure 3). Application of Pettitt’s nonparametric test to annual climate series (1991–2020) from 13 meteorological stations revealed contrasting change-point behavior for air temperature and precipitation. Annual mean air temperature (T

mean) exhibited a highly coherent response, with a statistically significant change point detected in 2006 at all stations. Test statistics (K

t) ranged from 160 to 204, with p-values between 0.00013 and 0.00406, indicating rejection of the homogeneity hypothesis at the 0.05 level. Positive U

t,n discontinuities indicate an abrupt post-2006 warming, with estimated increases of 0.8–1.5 °C relative to the pre-change period. The uniform timing and magnitude of these shifts suggest a dominant regional-scale forcing, consistent with the accelerated warming observed in the Balkan region since the early 2000s.

In contrast, annual total precipitation (Ptotal) showed pronounced spatial heterogeneity. Significant change points were identified at four stations (Mavrovo, Demir Kapija, Berovo, and marginally Prilep), all occurring in 2001, with Kt values between 117 and 149 and p-values below 0.05, except for the borderline case at Prilep. Negative Ut,n discontinuities indicate post-change decreases of approximately 150–300 mm yr⁻¹. No statistically significant shifts were detected at the remaining nine stations (p = 0.067–0.522). These results highlight a clear divergence between temperature and precipitation responses, with coherent regional warming contrasted by spatially variable and locally controlled precipitation changes.

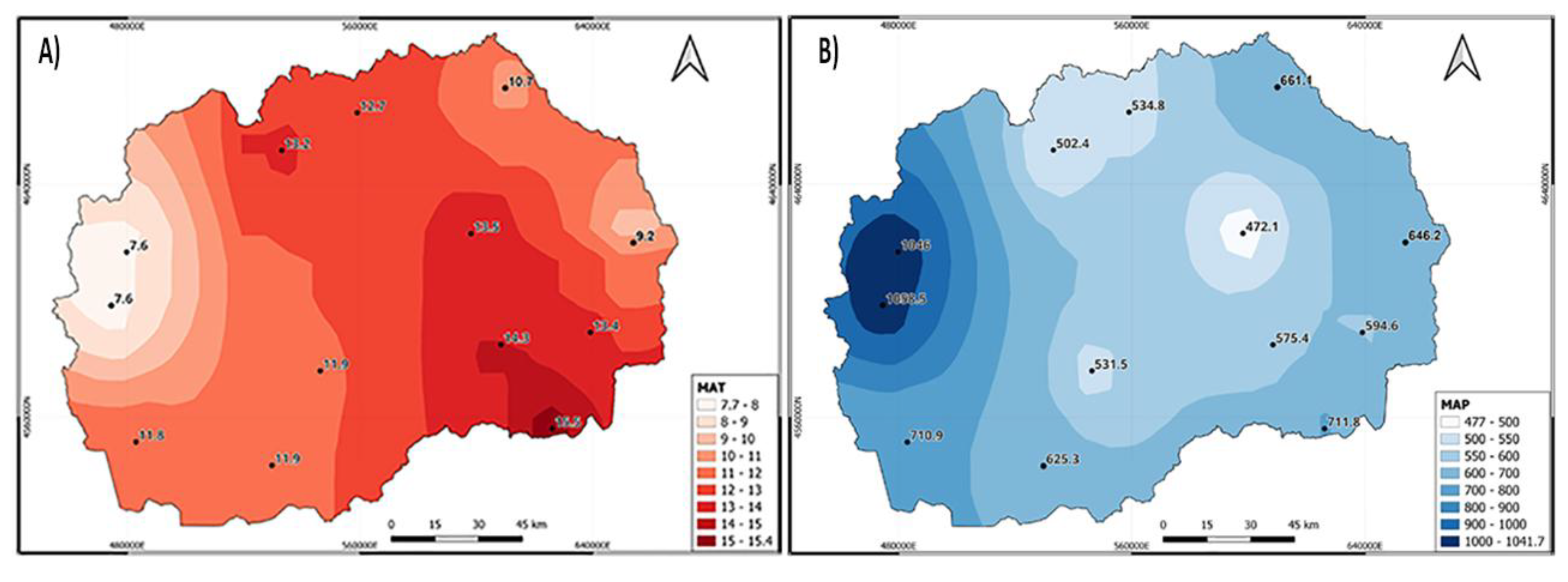

3.2. Air temperature, precipitation, and aridity classification

To evaluate the spatial variation of aridity across North Macedonia, mean annual air temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) were analyzed for the 1991–2020 reference period, providing critical insights into regional climatic patterns (

Figure 4). These parameters underpin the calculation of the I

DM. The I

DM quantifies aridity, with higher values indicating more humid conditions and lower values denoting aridity. Data from 13 meteorological stations, spanning diverse topographic settings from low-elevation valleys to high-altitude mountainous regions, were used to assess spatial variability in these parameters.

The MAP values exhibit pronounced spatial heterogeneity, driven by topographic and geographic factors. The lowest MAP, 472.1 mm, is recorded at Štip, a station in the eastern lowlands at approximately 300 m elevation. This low precipitation reflects the region’s continental climate and rain-shadow effect, as it lies leeward of the western mountains. In contrast, the highest MAP, 1,058.5 mm, is observed at Lazaropole, located in the western mountainous region at <1,330 m elevation. This elevated precipitation results from orographic forcing, where moist air masses ascending the steep topography undergo adiabatic cooling, leading to enhanced condensation and rainfall. Other high-altitude stations, such as Mavrovo (<1,250 m), also exhibit high MAP values, reinforcing the role of elevation in amplifying precipitation through orographic effects.

Similarly, MAT values display significant spatial variability, primarily influenced by elevation and proximity to Mediterranean or continental climatic influences. The highest MAT, 15.5°C, is recorded in Gevgelija, a low-elevation station (<60 m) in the southeastern part of the country, which experiences a Mediterranean climate characterized by mild winters and warm summers. In contrast, the lowest MAT, 7.6 °C, is observed at Lazaropole and Mavrovo, both situated at high altitudes in the western mountains. This lower air temperature is attributed to the environmental lapse rate, approximately 6.5 °C per 1,000 m, which reduces air temperatures at higher elevations. Additionally, Lazaropole holds the record for the absolute minimum air temperature in North Macedonia, -31.2 °C, recorded during a winter period of intense radiative cooling under clear skies and stable atmospheric conditions. At higher altitudes, dynamic atmospheric circulation over steep slopes facilitates mixing and prevents prolonged stagnation of cold air, unlike in valleys and depressions, where cold air pooling can exacerbate low air temperatures.

As a major urban and industrial center, the climate of Skopje is significantly modified by the urban heat island (UHI) effect, a phenomenon where urban areas exhibit higher air temperatures than surrounding rural regions due to anthropogenic activities and infrastructure [

76]. The UHI effect in Skopje, driven by heat-absorbing surfaces (e.g., concrete, asphalt), reduced vegetation, and waste heat from industrial and vehicular sources, elevates local air temperatures, particularly at night. Kaplan et al. (2018) [

77] estimate that Skopje’s UHI can increase air temperatures by 1–3 °C compared to nearby rural areas, exacerbating aridity by enhancing evapotranspiration rates. This urban modification compounds the semi-dry conditions indicated by Skopje’s low I

DM, posing challenges for urban water management and heat stress mitigation.

Lazaropole, with an MAT of 7.6 °C, is the meteorological station with the lowest mean annual air temperature in North Macedonia, tied with Mavrovo. Its high-altitude location fosters colder conditions, and it is also the site where the absolute minimum air temperature of North Macedonia, -31.2 °C, was recorded. This extreme is attributed to radiative cooling in winter, amplified by clear skies and the station’s elevated, exposed position. In contrast to high-altitude stations, low-elevation valleys and depressions, such as those near Skopje and Štip, experience prolonged cold air pooling due to topographic sheltering, which can lead to air temperature inversions and locally lower minimum air temperatures. However, the dynamic circulation processes over steep slopes at higher altitudes, such as in Lazaropole, promote air mixing, reducing the persistence of extreme cold compared to valley bottoms. Thus, the western mountainous stations, exemplified by Lazaropole and Mavrovo, exhibit markedly more humid climates due to high precipitation and lower air temperatures, as reflected in their elevated IDM values. In contrast, stations in the central and eastern lowlands, such as Štip and Skopje, are characterized by greater aridity, driven by lower precipitation, higher air temperatures, and, in Skopje’s case, urban-induced warming. These patterns align with regional topographic and climatic gradients, emphasizing the critical roles of elevation, continentality, and urbanization in shaping local aridity conditions across North Macedonia.

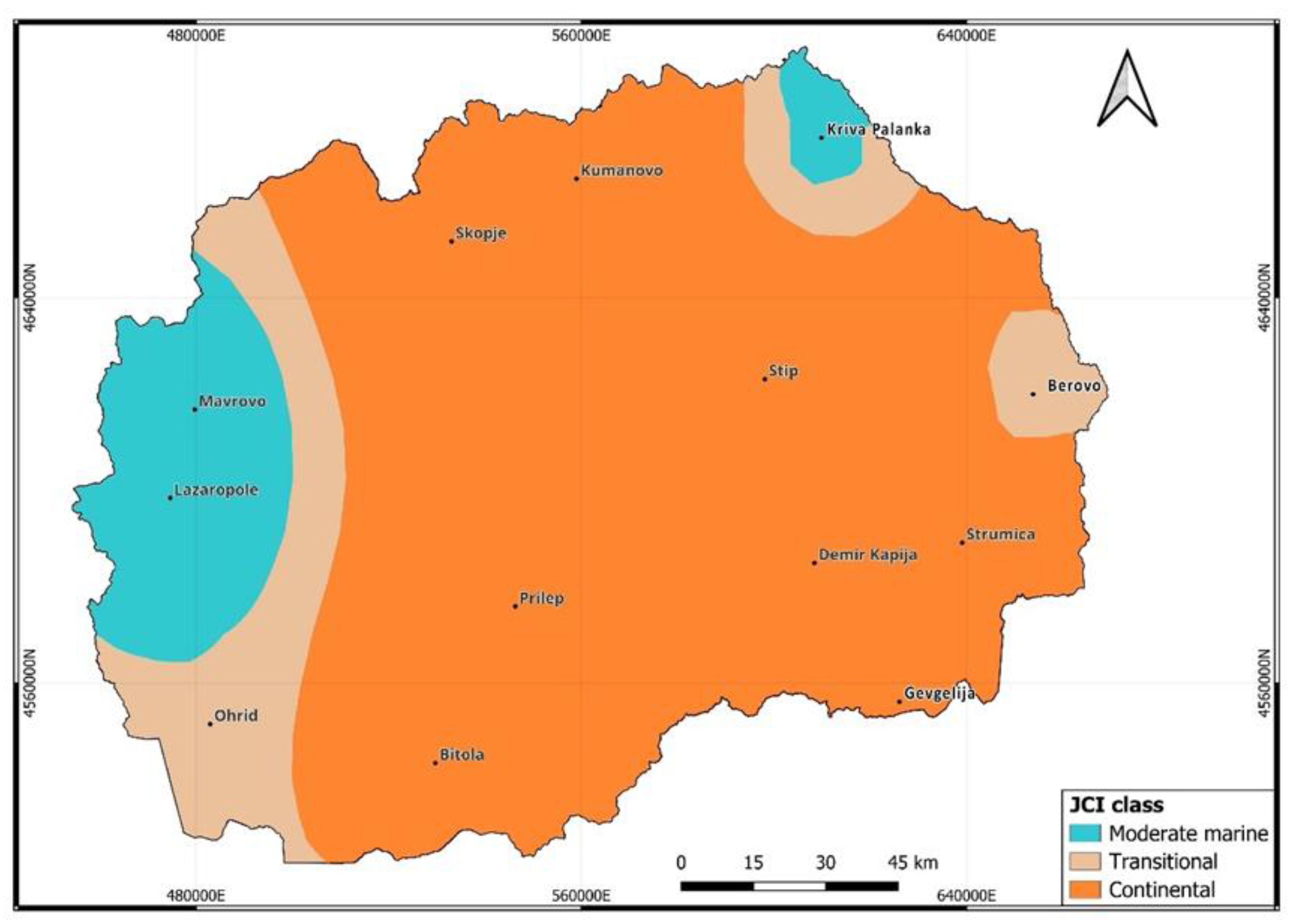

3.3. JCI distribution

The application of the Johansson Continentality Index (JCI) across North Macedonia reveals the presence of three of the four classical JCI climate classes—Moderate Marine, Transitional, and Continental—over both natural and agricultural areas (hereafter abbreviated as NatA and AgrA, respectively). The Marine class is notably absent, reflecting the minimal influence of maritime air masses within the national territory (

Figure 5).

Moderate Marine climates are primarily observed in the western highlands and northeastern uplands, where topographic complexity and elevation act to moderate thermal extremes. Stations in this category include Mavrovo (30.1), Lazaropole (27.2), and Kriva Palanka (30.9). The reduced annual air temperature range in these areas reflects a substantial attenuation of continental effects, resulting in conditions partially influenced by distant maritime air masses (

Table 6). Transitional climates occur predominantly in eastern peripheral and western regions, characterized by intermediate annual thermal amplitudes. Representative stations include Berovo (32.7) in the eastern highlands and Ohrid (32.4) in the southwestern region. These locations exhibit neither strongly continental nor distinctly marine characteristics, producing moderate seasonal air temperature variability. The Continental climate class is widespread, dominating the lowlands and central valleys of the country. Stations representing this regime include Bitola (39.4), Demir Kapija (39.7), Kumanovo (38.6), Skopje (38.8), Strumica (38.5), Štip (38.4), and Gevgelija (38.2). These areas are subject to pronounced seasonal air temperature contrasts, a consequence of their distance from maritime influences and the limited topographic shielding, which enhances the annual air temperature amplitude.

Analysis of the aggregated annual JCI revealed significant fluctuations in the thermal continental influence across the period of study. The highest JCI values were recorded in 2017 (approximately 49.33) and 2000 (approximately 47.05). These high index values indicate the most pronounced degree of continentality experienced in these specific years, reflecting maximum average annual air temperature amplitudes. Conversely, the lowest JCI value observed was 2014 (approximately 26.96). According to the categorization scheme adopted, this value places the year 2014 within the Moderate Marine climate category (JCI interval 20–32).

Thus, the JCI results demonstrate a distinct spatial gradient of continentality in North Macedonia. Moderate Marine climates are confined to the western highlands and northeastern uplands, Transitional climates are distributed in western peripheral and eastern border regions, while Continental climates dominate the central valleys and lowlands, encompassing the majority of the national territory. This spatial pattern emphasizes the integrative influence of latitude, topography, and distance from maritime sources in shaping the continentality regime across the country.

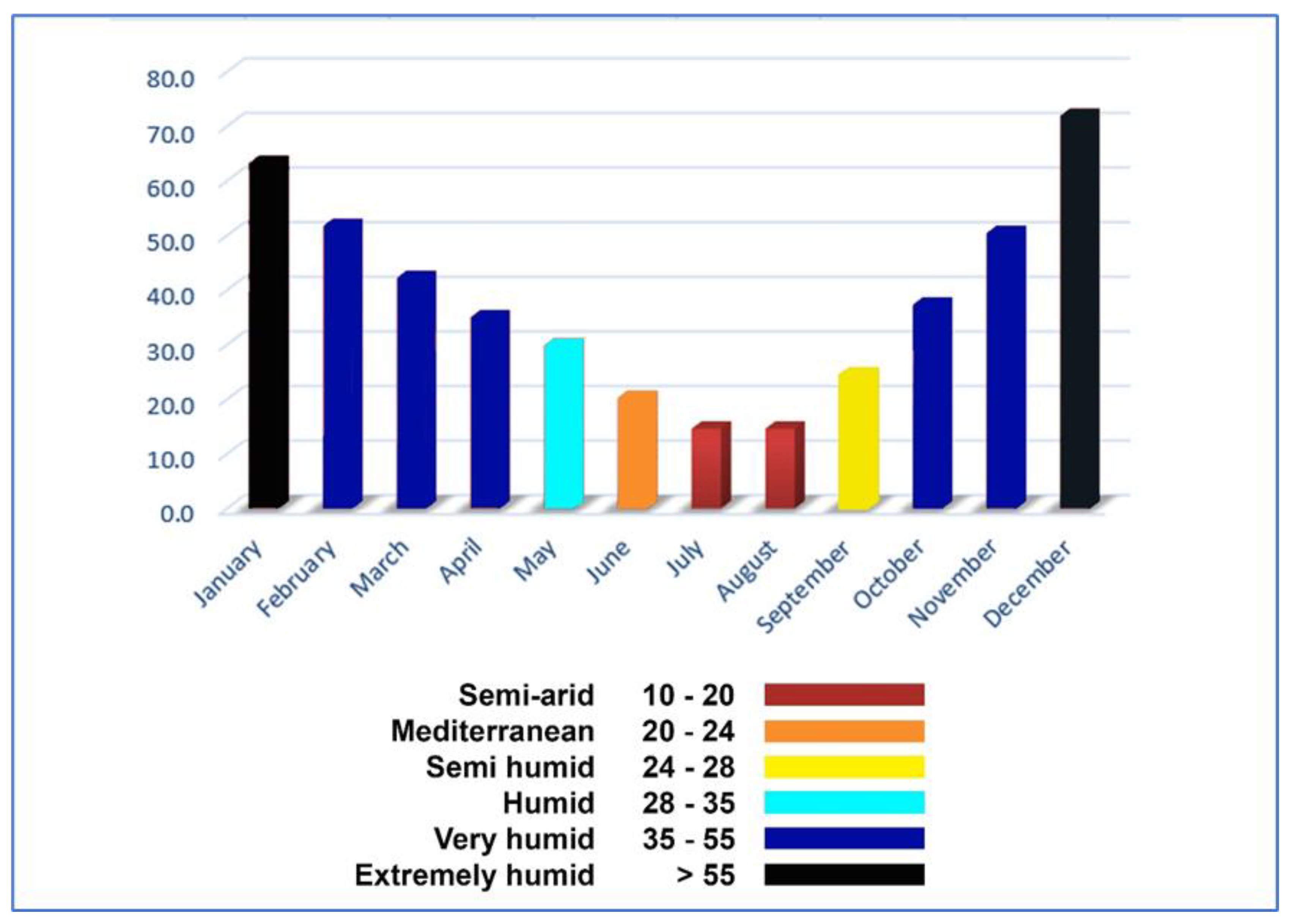

3.3. Monthly analysis

According to the monthly values of the I

DM (Im

DM), six out of seven climate types are recognized. January and December are considered extremely humid, with the maximal value of 71.9 (

Figure 6). February, March, April, October, and November are very humid, where February has the highest value reaching 51.7. May is humid. September is characterized as semi-humid. June is Mediterranean, while July and August are semi-arid, both with a value of 14.6.

The IDM reveals distinct spatial differentiation in climatic conditions across North Macedonia. The highest IDM values, 72.9 at Lazaropole and 71.6 at Mavrovo, classify these locations as extremely humid (IDM > 55), reflecting their high precipitation and cooler air temperatures driven by mountainous topography. These conditions support lush vegetation and water availability, characteristic of humid climates. In contrast, Štip (IDM = 22.2) and Skopje (IDM = 22.3) exhibit the lowest IDM values, placing them within the Mediterranean climate category (20 ≤ IDM < 24), indicative of semi-dry conditions. These lowland stations experience lower precipitation and higher air temperatures, contributing to greater aridity compared to the western highlands.

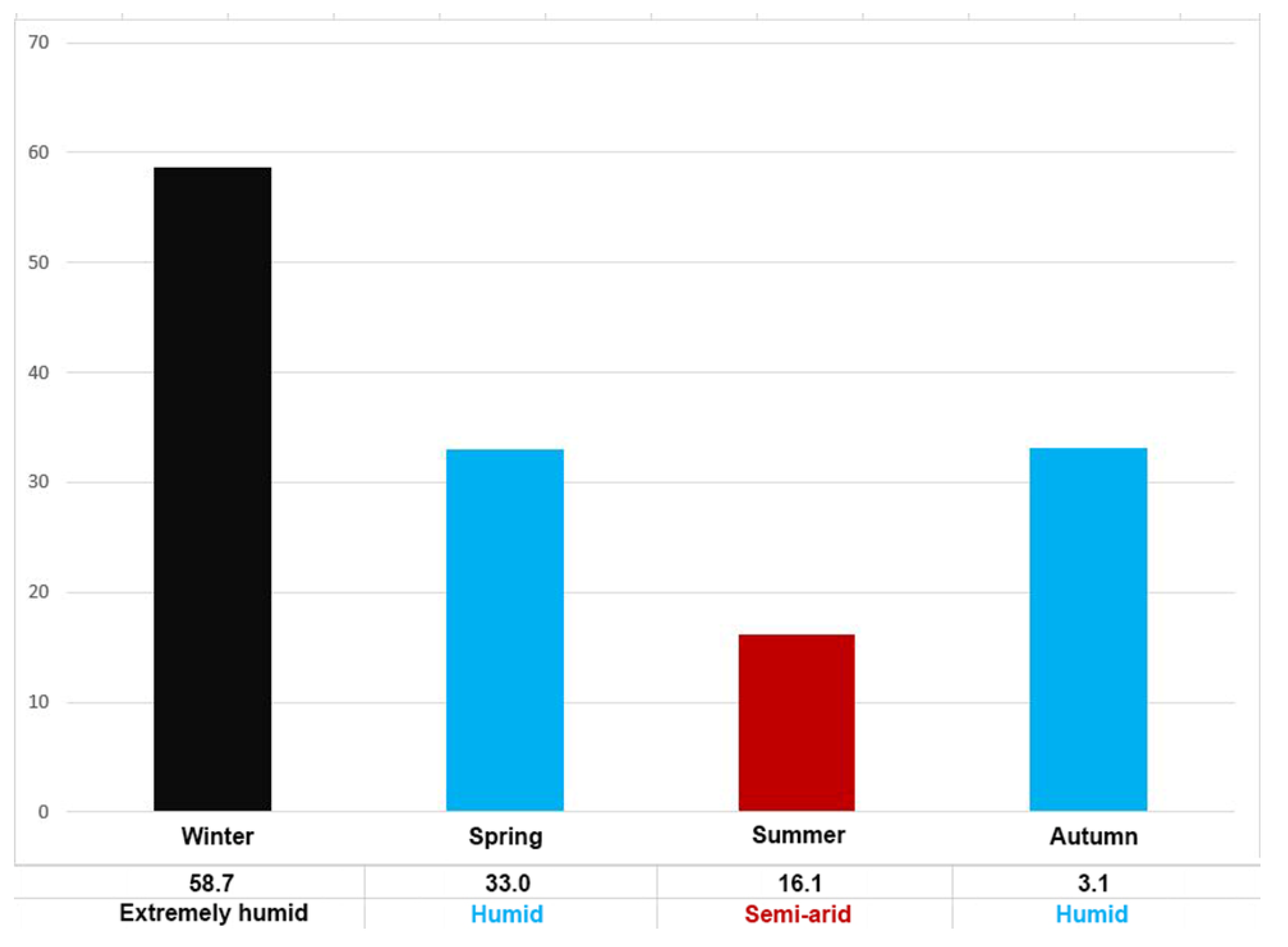

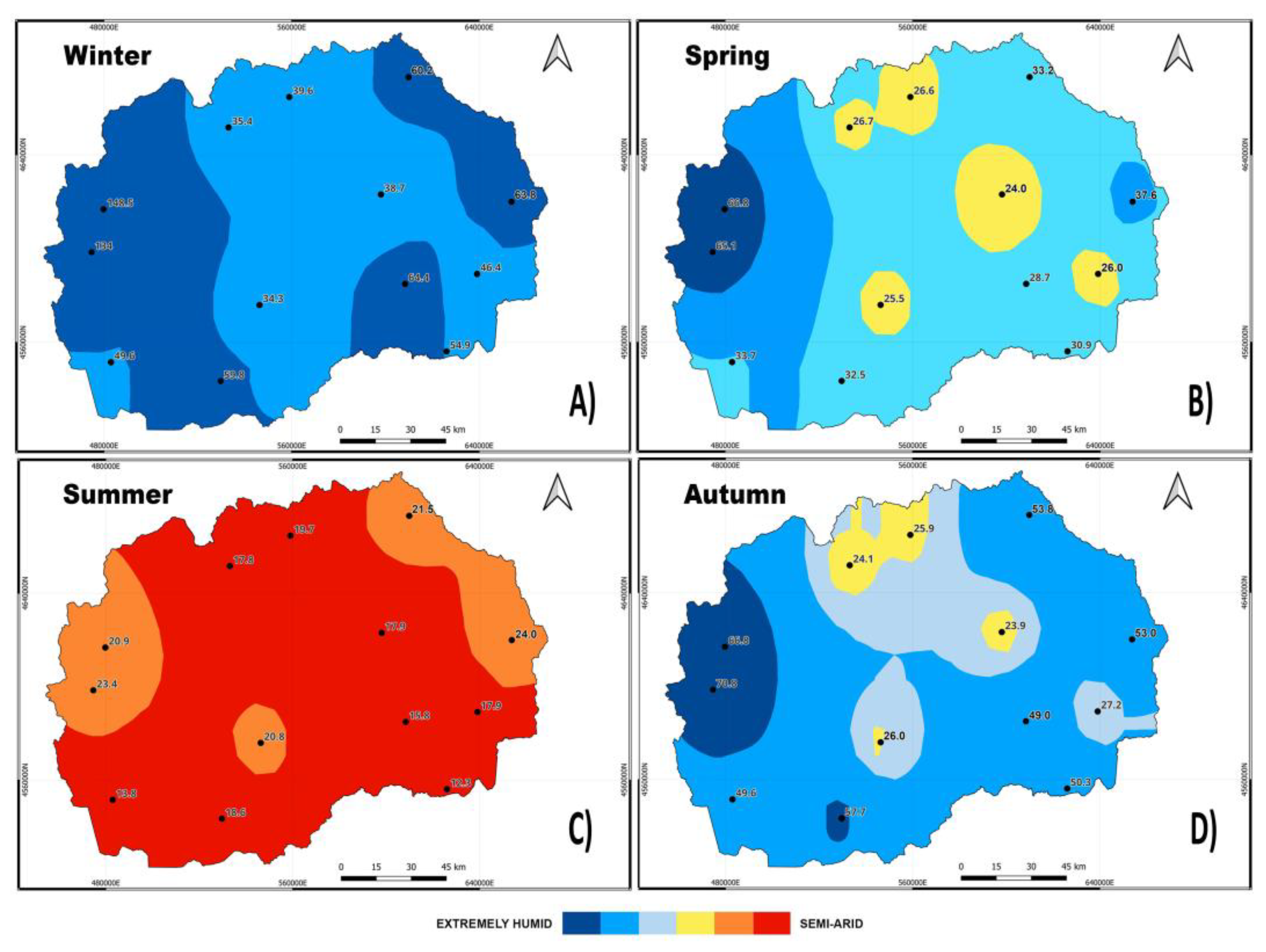

3.3. Seasonal analyses

The seasonal distribution of the Is

DM across North Macedonia reveals pronounced climatic variability controlled predominantly by topography, elevation, and regional meteorological influences (

Figure 7).

Winter is generally humid across the country, with a national mean Is

DM of 58.7 (

Table 7). Mountainous stations show extremely high humidity, with Mavrovo reaching 148.5 and Lazaropole 134.0, due to substantial precipitation (>300 mm) combined with low air temperatures (-1.2 to -0.7 °C). Lowland stations, including Skopje (35.4), Kumanovo (39.6), Prilep (34.3), and Strumica (46.4), exhibit semi-humid conditions, reflecting lower precipitation and warmer air temperatures (1–3 °C).

Spring displays generally humid conditions, national IsDM 33.0, with the highest indices in mountainous stations: Mavrovo (66.8) and Lazaropole (65.1), supported by moderate precipitation (<270 mm) and rising air temperatures (<6–7 °C). Lowland areas such as Skopje (26.7), Kumanovo (26.6), and Strumica (26.0) experience semi-humid climates due to slightly reduced rainfall and warmer air temperatures (<12–13 °C).

Summer shows the highest climatic heterogeneity, national Is

DM 16.1. Mountainous stations maintain humid to semi-humid conditions: Mavrovo (20.9), Lazaropole (23.4), while lowlands experience pronounced aridity, for example, Gevgelija (12.3), Bitola (18.6), and Štip (17.9). High air temperatures (up to 27 °C) combined with reduced precipitation (<100–130 mm seasonally) explain the low summer indices in low-altitude stations. (see

Table 8).

Autumn signals a return to humid conditions, national IsDM 33.1. Mountainous regions such as Mavrovo (66.8), Lazaropole (70.8), Berovo (53.0), and Ohrid (49.6) show the highest seasonal indices. Lowland stations including Skopje (24.1), Kumanovo (25.9), Prilep (26.0), and Strumica (27.2) maintain semi-humid climates, reflecting moderate precipitation (<150–180 mm) and air temperatures (<12–14 °C).

This analysis emphasizes the critical influence of elevation, orography, and regional geography in shaping North Macedonia's climatic variability (see

Figure 8). Humidity peaks consistently in northwestern mountainous regions during winter and spring, whereas lowlands and southern plains experience strong summer aridity. Autumn acts as a transitional season with spatial heterogeneity persisting. Such detailed seasonal patterns are crucial for hydrological heritage assessments, ecosystem management, agricultural planning, and climate adaptation strategies.

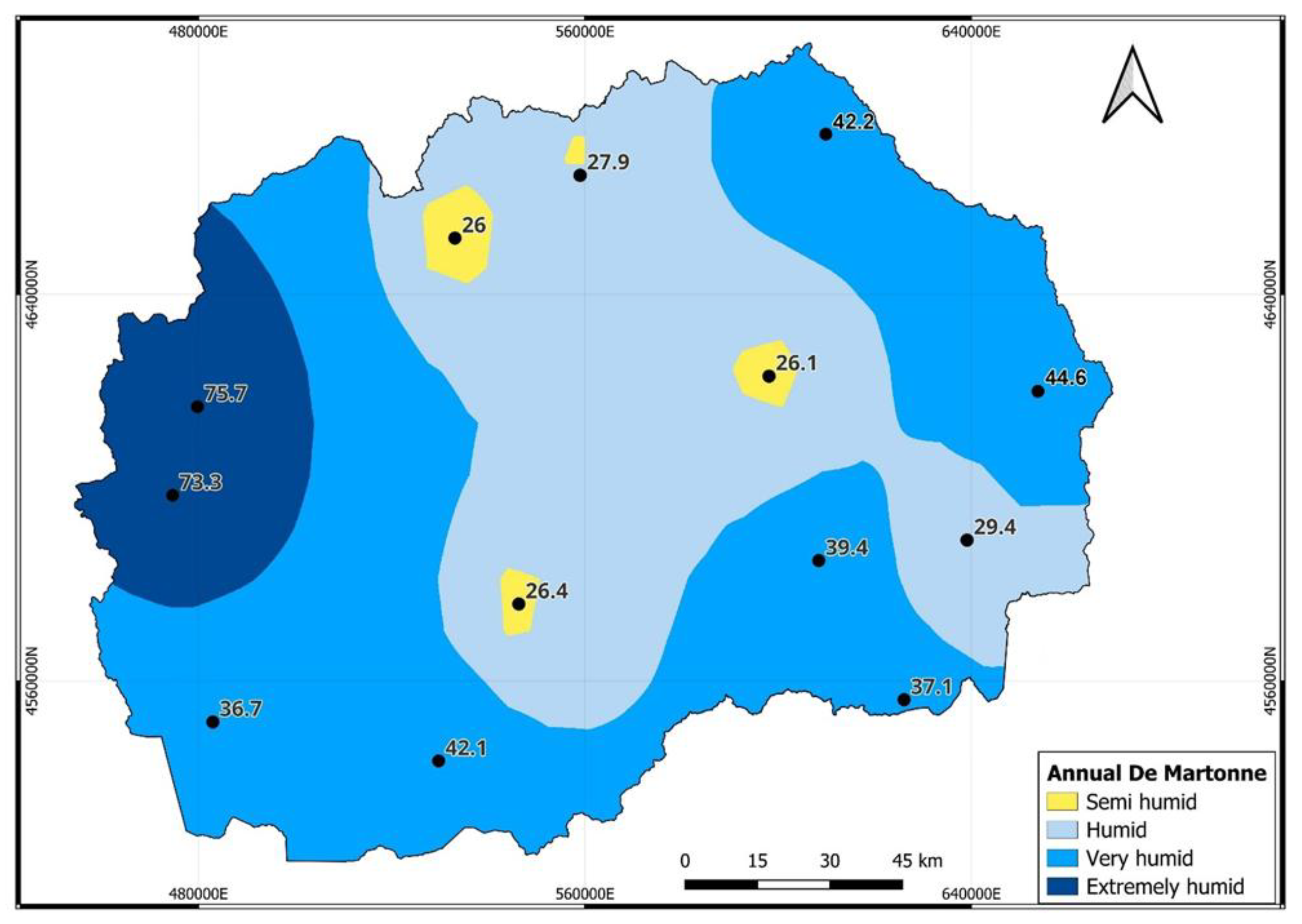

3.4. Annual De Martonne aridity index (IDM) analysis

The De Martonne aridity index (IDM) was calculated annually for 13 meteorological stations across North Macedonia, revealing significant spatial and temporal variability in hydrothermal conditions driven by altitude, precipitation patterns, and regional topography. Over the 30-year period from 1991 to 2020, annual IDM values ranged from 18.8 to 42.3, reflecting a spectrum of climatic conditions from semi-arid to very humid, with a clear spatial pattern influenced by elevation and atmospheric dynamics. The mean annual IDM across all stations, calculated as the average of the annual values, is 28.8, classifying North Macedonia’s overall climate as semi-humid on average, though with pronounced regional variations.

The highest I

DM values, indicative of the most humid conditions, are observed in the mountainous regions of western and northwestern North Macedonia. Mavrovo, with an I

DM of 75.7, and Lazaropole, with an I

DM of 73.3, both located in high-altitude areas near Mount Korab and the Bistra Mountain range, exhibit extremely humid conditions due to high precipitation and cooler air temperatures associated with mountainous terrain. Very humid climates dominate mid-altitude and mountainous regions, including Berovo with an I

DM of 44.6, Bitola at 42.1, Gevgelija at 37.1, Demir Kapija at 39.4, Kriva Palanka at 42.2, and Ohrid at 36.7, benefiting from consistent precipitation and moderate air temperatures (

Table 9). In contrast, Strumica, with an I

DM of 29.4, exhibits a humid climate, reflecting lower precipitation and warmer air temperatures compared to higher-altitude regions. Semi-humid conditions prevail in lowland areas, including Kumanovo with an I

DM of 27.9, Prilep at 26.4, Skopje at 26.0, and Štip at 26.1, indicative of drier and warmer environments. Approximately 15% of the stations (two stations, Mavrovo and Lazaropole) are classified as extremely humid, 46% (six stations) as very humid, 8% (one station, Strumica) as humid, and 31% (four stations) as semi-humid, underscoring the dominance of humid conditions in North Macedonia’s climate.

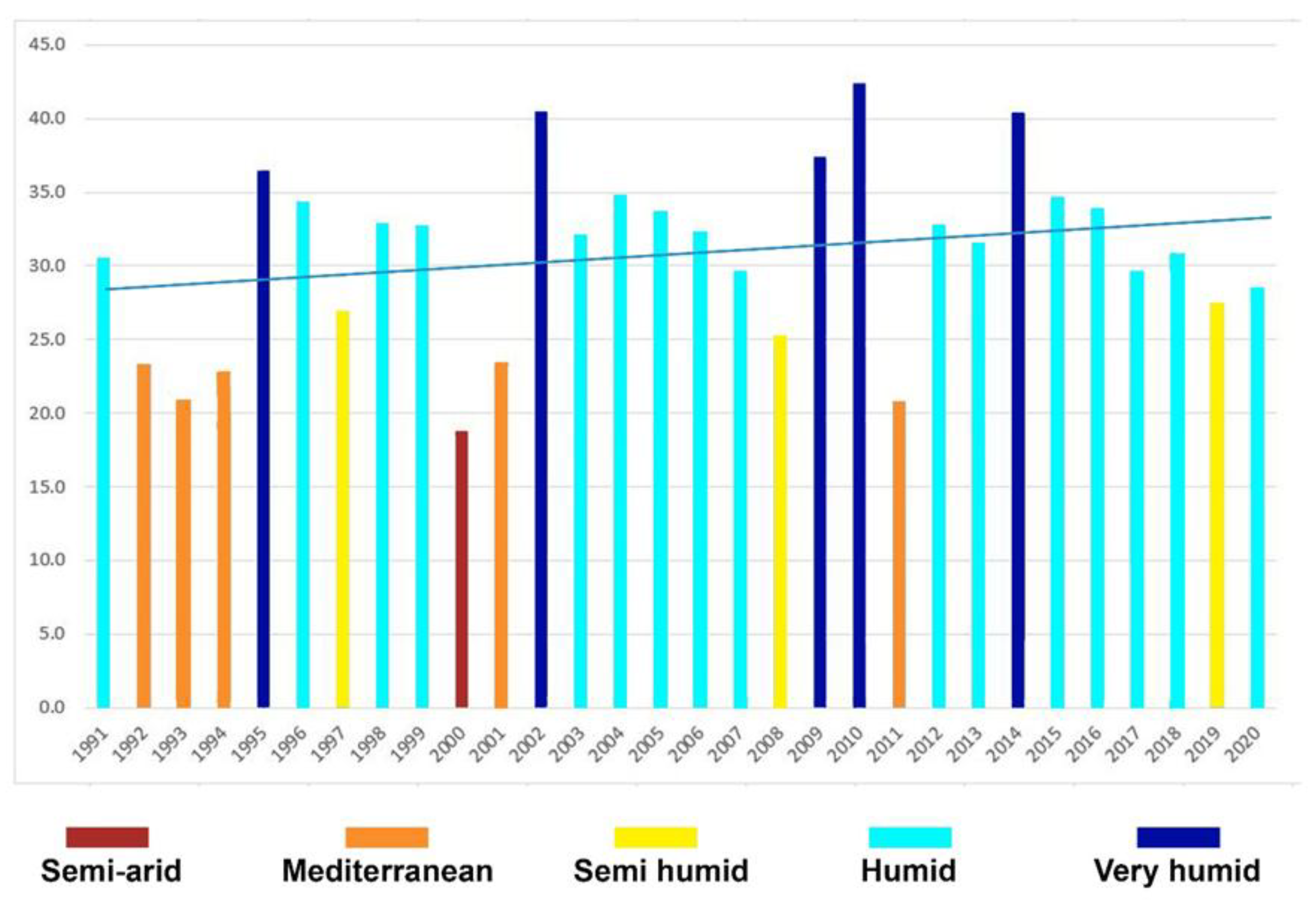

The annual variations of the I

DM over the 30-year period show significant temporal variability (

Figure 9). Of the 30 years analyzed, five years were classified as very humid (I

DM 35–55): 1995 with an I

DM of 36.5, 2002 with 40.3, 2009 with 37.2, 2010 with 42.3, and 2014 with 40.2. Sixteen years were classified as humid (I

DM 28–35): 1991 with 30.4, 1996 with 34.2, 1998 with 32.9, 1999 with 32.6, 2003 with 31.9, 2004 with 34.6, 2005 with 33.7, 2006 with 32.2, 2007 with 29.5, 2012 with 32.7, 2013 with 31.5, 2015 with 34.6, 2016 with 33.8, 2017 with 29.5, 2018 with 30.7 and 2020 with 28.4. Three years were classified as semi-humid (I

DM 24–28): 1997 with 26.8, 2008 with 25.2, and 2019 with 27.4. Five years were classified as mediterranean (I

DM (20–24): 1992 with 23.3, 1993 with 20.8, 1994 with 22.8, 2001 with 23.4, and 2011 with 20.8. One year, 2000, with an I

DM of 18.8, was classified as semi-arid, reflecting notably dry conditions consistent with regional drought patterns in the Balkans, as reported in studies such as Lukovic et al. (2013) [

78] and Milevski et al. (2015) [

79], and corroborated by the National Hydrometeorological Service – Skopje (2021) [

80]. This dry year likely resulted from significantly reduced precipitation and elevated air temperatures. The maximum I

DM value was observed in 2014, with an I

DM of 42.3, aligning with reports of exceptionally high precipitation across the region, as noted by the National Hydrometeorological Service – Skopje (2021) [

80] and the Copernicus Climate Change Service (2022) [

81]. No years were classified as arid (I

DM < 10) or extremely humid (I

DM ≥ 55), indicating that North Macedonia’s climate remains predominantly within the humid to semi-humid range.

Although this analysis provides a robust understanding of the spatial and temporal variability of the IDM, precise quantification of the area coverage for each climate type would require the development of a continuous annual IDM map using spatial interpolation methods, such as Inverse Distance Weighting or Kriging. Such mapping would enable a detailed assessment of hydrological and ecological variability, supporting improved water resource management, climate impact analysis, and sustainable land-use planning.

Overall, the annual I

DM demonstrates a clear altitudinal control on climate, with elevated and mountainous regions maintaining extremely humid to very humid conditions, mid-altitude stations exhibiting very humid climates, and lowland areas displaying semi-humid characteristics (see

Figure 10). The mean annual I

DM of 28.8, classifying the country as semi-humid, reflects the balance between the wetter, high-altitude northwest and the drier, lowland southeast. The rarity of semi-arid conditions, occurring in only one year, underscores the mitigating influence of North Macedonia’s continental and mountainous climate, which ensures a degree of moisture even in the driest periods. This pattern emphasizes the significant influence of topography and precipitation on the spatial distribution of climatic conditions in North Macedonia, providing critical insights for hydrological studies, ecological assessments, and climate adaptation strategies.

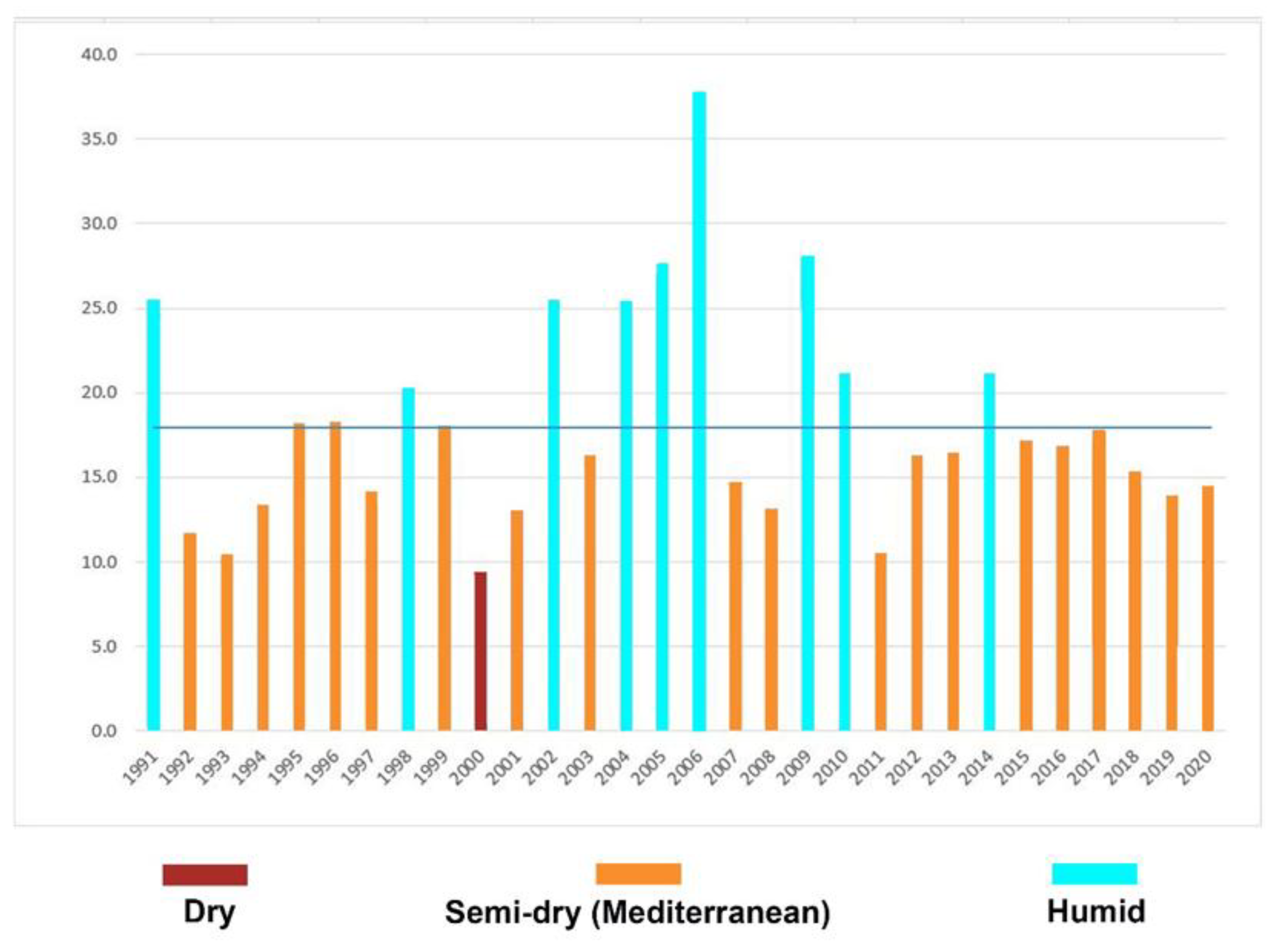

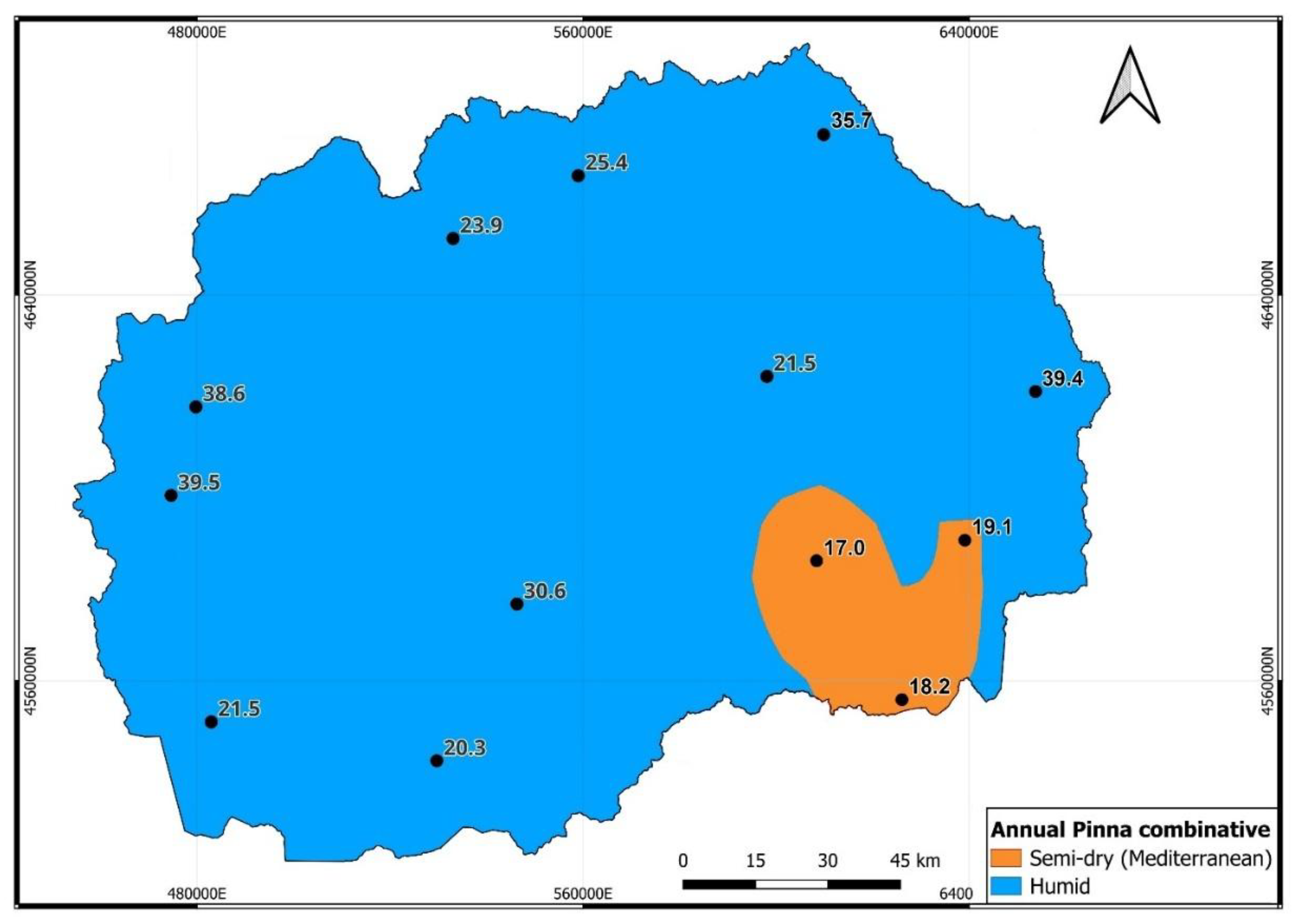

3.5. Annual Pinna combinative index (IP) analysis

The Pinna combinative aridity index (IP) was calculated annually for 13 meteorological stations across North Macedonia, revealing a diverse range of hydrothermal conditions shaped by topography and regional climatic factors. Over the 30-year period from 1991 to 2020, IP values ranged from 9.4 to 37.7, reflecting a spectrum of climatic conditions from dry to humid, with a pronounced spatial pattern driven by elevation and atmospheric influences. The mean annual IP for the entire country, calculated as the average of the annual IP values over this period, is 18.2, indicating that North Macedonia’s overall climate is semi-dry (Mediterranean) on average, though significant spatial and temporal variations exist.

The highest IP values, which indicate the most humid conditions, are observed in the mountainous regions of western and northwestern North Macedonia. Lazaropole, located in the high-altitude Bistra Mountain range, recorded the highest station-specific IP at 39.5, followed closely by Berovo at 39.4 in the Maleševo Mountains and Mavrovo at 38.6 near Mount Korab, North Macedonia’s highest peak at 2,764 m. These stations experience substantial annual precipitation, such as 1058.5 mm at Lazaropole and 1046.0 mm at Mavrovo, combined with cooler mean annual air temperatures of 7.6°C at both locations, resulting in their classification as humid (IP ≥ 20). The high elevation in these areas enhances orographic precipitation, as moist westerly air masses are forced upward, cooling and condensing to produce significant rainfall. The most humid year in the dataset was 2006, with an IP of 37.7, likely most pronounced at Lazaropole due to its consistently high IP values driven by elevation and precipitation.

In contrast, the lowest IP values are found in the southeastern lowlands, where Demir Kapija recorded an IP of 17.0, Gevgelija 18.2, and Strumica 19.1, all classified as semi-dry (Mediterranean) with IP values between 10 and 20. These stations, situated in the Vardar River Valley near the Aegean Sea, experience higher mean annual air temperatures, such as 15.5°C at Gevgelija and 14.3°C at Demir Kapija, and lower precipitation in their driest months, for example, 25.8 mm in August at Gevgelija and 30.8 mm at Demir Kapija. The driest year recorded was 2000, with an IP of 9.4, likely most pronounced at Demir Kapija, which consistently exhibits the lowest station-specific IP due to its warm, dry conditions. This year marked the only instance of fully dry conditions (IP < 10) in the 30-year period, likely driven by anomalously low precipitation and elevated air temperatures influenced by strong Mediterranean air masses. The lowest IP value, 9.4 in 2000 at Demir Kapija, reflects the extreme aridity in the southeastern lowlands during that year.

Central and northern stations, including Kumanovo with an IP of 25.4, Skopje at 23.9, Ohrid at 21.5, and Štip at 21.5, are classified as humid, with IP values ranging from 21.5 to 25.4. Prilep, with an IP of 30.6, and Kriva Palanka, with an IP of 35.7, also exhibit humid conditions, the latter driven by substantial annual precipitation of 661.1 mm despite a moderate mean air temperature of 10.7°C. Bitola, with an IP of 20.3, lies in a transitional zone between the humid northwest and semi-dry southeast.

Over the 30-year period, climatic conditions varied significantly (

Figure 11). Dry conditions, defined as I

P values below 10, occurred only in 2000 with an I

P of 9.4, representing just one year or 3.3% of the period. This exceptionally dry year, likely most pronounced at Demir Kapija, was driven by significantly reduced precipitation and higher air temperatures, possibly due to strong Mediterranean air masses affecting the southeastern lowlands. Semi-dry conditions, with I

P values between 10 and 20, were observed in 20 years, accounting for 66.7% of the period: 1992 with an I

P of 11.7, 1993 with 10.4, 1994 with 13.4, 1995 with 18.2, 1996 with 18.3, 1997 with 14.2, 1999 with 18.0, 2001 with 13.0, 2003 with 16.3, 2007 with 14.7, 2008 with 13.1, 2011 with 10.5, 2012 with 16.3, 2013 with 16.4, 2015 with 17.2, 2016 with 16.9, 2017 with 17.8, 2018 with 15.3, 2019 with 14.0, and 2020 with 14.5. These years were characterized by warmer, drier Mediterranean influences, particularly affecting southeastern stations like Demir Kapija, Gevgelija, and Strumica. Humid conditions, with I

P values of 20 or greater, prevailed in 9 years, representing 30.0% of the period: 1991 with an I

P of 25.5, 1998 with 20.3, 2002 with 25.5, 2004 with 25.4, 2005 with 27.6, 2006 with 37.7, 2009 with 28.0, 2010 with 21.2, and 2014 with 21.1. These years corresponded to periods of higher precipitation and cooler air temperatures, particularly in the mountainous northwest, with stations like Lazaropole and Mavrovo experiencing the most pronounced humidity.

The spatial distribution of I

P values reveals a clear gradient from the humid northwest to the semi-dry southeast. High mountains in the west, such as Korab, Bistra, and Šar Planina, act as barriers that capture moisture from westerly air masses, resulting in higher precipitation and cooler air temperatures. Conversely, the southeastern lowlands, influenced by the Vardar valley’s channeling of warm, dry Mediterranean air from the Aegean Sea, experience reduced precipitation and higher air temperatures, leading to semi-dry conditions. The Aegean Sea’s proximity exacerbates aridity in the southeast, particularly in summer months, as evidenced by low precipitation values. The mean annual I

P of 18.2, classifying North Macedonia as semi-dry on average, reflects the balance between the humid, high-altitude northwest and the drier southeast. The rarity of fully dry conditions, occurring in only one year, underscores the mitigating influence of the country’s continental and mountainous climate, which ensures a degree of moisture even in the driest regions (

Figure 12). The marked humidity at Lazaropole, Mavrovo, and Berovo emphasize the critical role of elevation, while the semi-dry conditions in the southeast, particularly at Demir Kapija, reflect the Aegean Sea’s influence, creating a distinct climatic gradient across North Macedonia (

Table 10).

3.6. Aridity trend

Aridity trends in North Macedonia were analyzed using the JCI, I

DM, and I

P indices through three statistical methods. First, linear trend equations were derived from mean annual JCI, I

DM, and I

P values across the region, graphically illustrating aridity changes [

43,

82,

83]. Second, the Mann-Kendall test assessed significant trends, testing the null hypothesis (H

0: no trend) against the alternative (H

a: significant trend) at α = 0.05. A p-value < α rejects H

0, confirming a trend, while p ≥ α retains H

0 [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. This robust approach, effective for missing data [

43], enhances understanding of North Macedonia’s climatic trends. Third, to refine the analysis and detect possible shifts in aridity over the study period, Pettitt’s nonparametric test was employed.

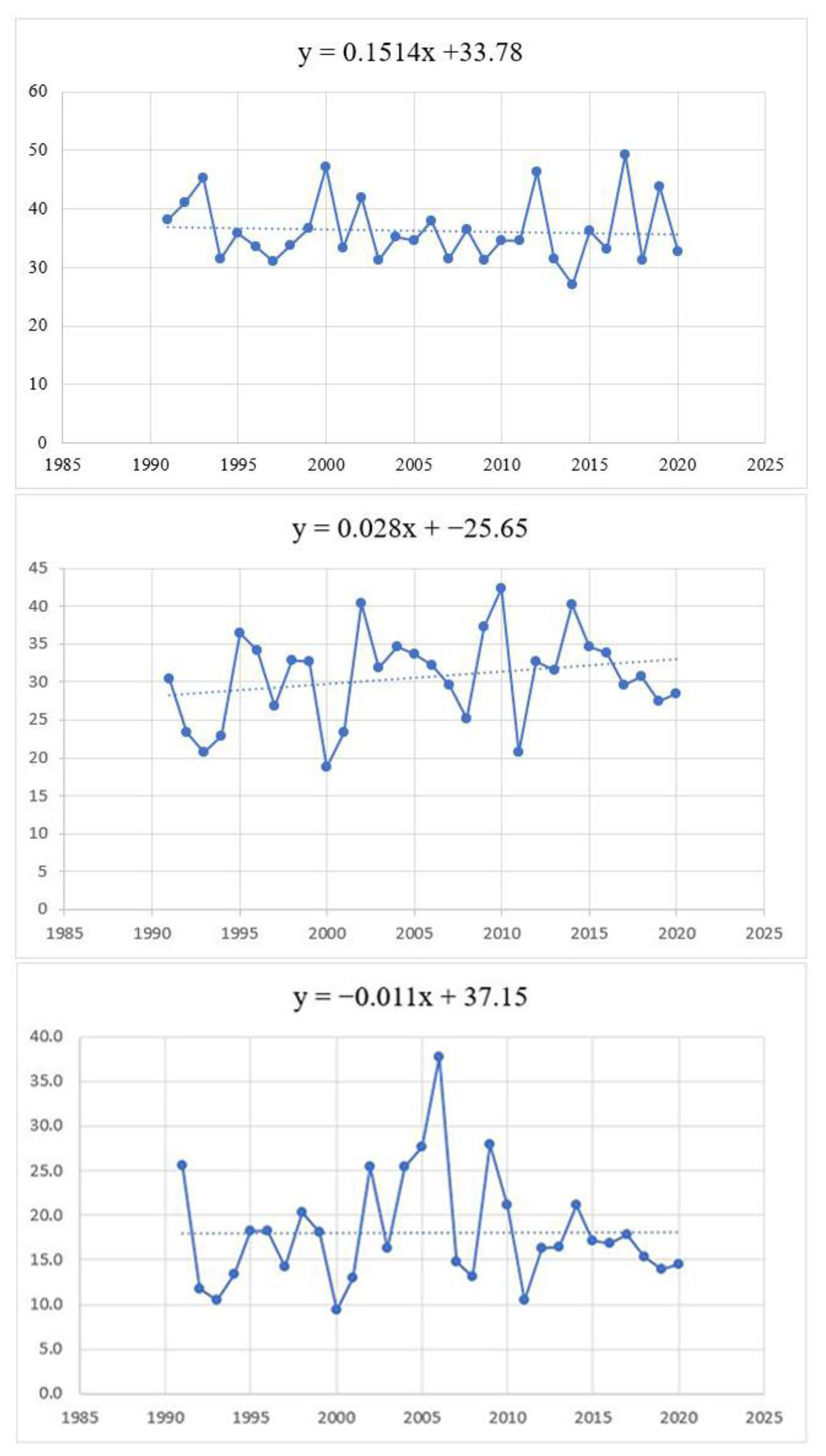

The temporal variation of aridity in North Macedonia was further analyzed using linear regression. For the I

DM, the obtained regression equation was: y = 0.028x − 25.65 and for the I

P: y = −0.011x + 37.15, where t is the time in years. For the JCI, the obtained regression equation was: y = 0.1514x +33.78. Trend lines are shown in

Figure 13. I

DM equation indicates a weak positive tendency in the I

DM, while I

P equation reflects a very weak negative tendency in the I

P, and JCI equation shows a very weak positive tendency in continentality. In all cases, the trends are extremely weak.

The Mann–Kendall (MK) test was applied to determine the statistical significance of the observed tendencies (

Table 11). As the obtained probabilities were greater than the significance level (α = 0.05, i.e. 5%), the null hypothesis H

0 of no trend cannot be rejected. The risks of committing a Type I error (rejecting H

0 while it is true) were 48.6% for the I

DM, 85.8% for the I

P, and 72.4% for the JCI, respectively. Consequently, the MK test showed that, considering all values of both indices, there is no statistically significant change in aridity trends in the last 30 years in North Macedonia.

The table summarizes Mann-Kendall trend analyses for the JCI, IDM, and IP, across 13 meteorological stations in North Macedonia (1991–2020), reporting annual averages and Sen's slope (β) estimates of long-term change. It shows no significant trends in aridity or continentality (all ZMK < 1.96, p > 0.05), underscoring overall climatic stability, with minor negative β values in low-elevation sites indicating subtle drying tendencies. This spatial pattern—characterized by wetter mountainous areas and drier, more vulnerable valleys—provides an essential reference point for understanding how ongoing climate warming may influence agricultural productivity and water availability across the region.

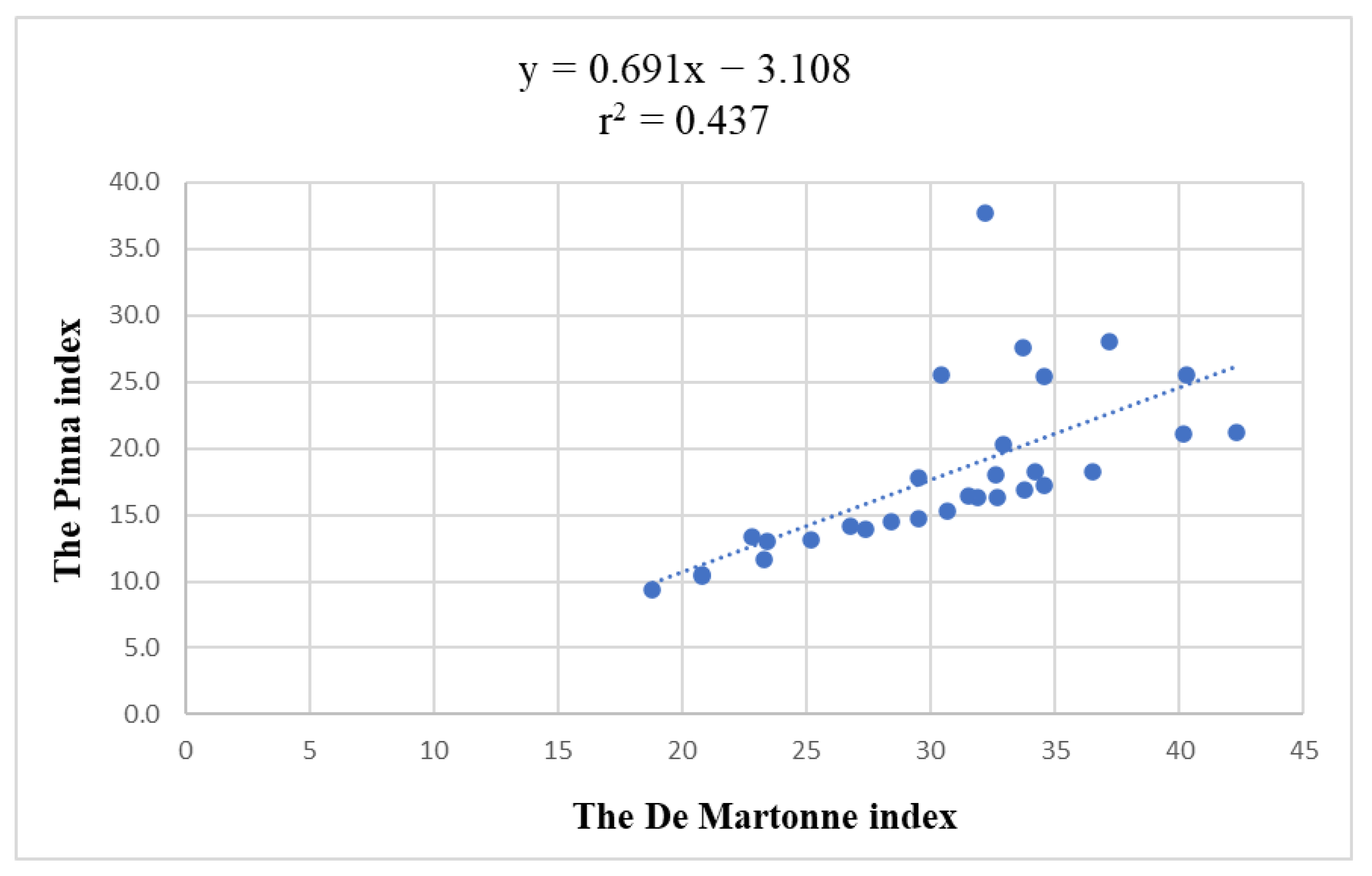

3.7. Correlation

Analysis of the I

DM and I

P for North Macedonia from 1991 to 2020 reveals stable climatic conditions, with no significant trend in aridity, indicating consistent precipitation and air temperature patterns across the region (

Figure 14). Both indices demonstrated comparable values in spatial distribution and no notable change in aridity, prompting a correlation analysis between them. The Pearson correlation coefficient r has a value of 0.66. The coefficient of determination r2 is 0.437 when the regression type is linear, as shown in

Figure 14, with the equation y = 0.691x – 3.108.

Correlation coefficients between the North Atlantic Oscillation Index – NAO [

89], El Niño-Southern Oscillation Index – SOI [

90], and seasonal and annual I

DM were determined to investigate possible relationships between aridity and atmospheric variability. To ensure transparency and reproducibility, NAOI and SOI data were sourced from NOAA's Climate Prediction Center (for NAOI) (National Centers for Environmental Information, 2023) and Physical Sciences Laboratory (for SOI) [

91], with monthly values averaged to derive seasonal indices (Winter: December–February, Spring: March–May, Summer: June–August, Autumn: September–November).

Annual correlations were derived by averaging seasonal I

DM, NAOI, and SOI values for each year. Results are shown in

Table 12. The correlation between the I

DM and the NAOI is significant (at the 5.0% level of significance) in summer (0.45). The positive correlation coefficient in summer indicates a drying effect on the I

DM in North Macedonia, potentially due to reduced precipitation under positive NAOI phases. A negative correlation coefficient in winter (−0.31, p = 0.098) suggests a wetting effect on the I

DM, though not statistically significant, reflecting increased moisture during negative NAOI phases. Since precipitation is one of the key components of the I

DM, the response of the I

DM to the NAOI can be associated with the established links between this index and precipitation dynamics [

92]. Our results align with findings from regional studies on summer precipitation patterns in the Southeastern Europe [

93]. For the SOI, a weak positive correlation in autumn (0.19) suggests minor ENSO influence during spring-like transitions in North Macedonia.

Coefficients significant at the 5% level (α = 0.05), indicating less than a 5% probability of Type I error, are presented in bold

Finding similar or identical results at regional and national scales is challenging and difficult. However, certain spatio-temporal patterns of aridity can be identified. This difficulty largely stems from the nature of the climate indices chosen for the study, as well as the specific selection criteria employed by the authors.

The spatial and temporal patterns of continentality and aridity in North Macedonia, derived from the JCI, I

DM, and I

P, reveal semi-dry conditions in lowland southeastern areas and semi-humid conditions in highlands during summer. These patterns are consistent with observations in neighboring countries. In Bulgaria, analysis of the I

DM index during 1961–2015 revealed semi-arid to arid conditions, while multiannual variability indicated decreasing aridity over the last three decades [

53]. Serbia shows pronounced continentality in lowlands with semi-dry to semi-humid climates and an absence of Mediterranean-type dry zones [

45]. In Kosovo and Metohija, semi-dry and semi-humid climates dominated during 1965–1999, with no significant aridity change [

44]. Montenegro exhibits generally humid to extremely humid conditions, except for semi-arid summer periods in coastal and adjacent inland areas, with trends indicating increasing aridity in April and August over the last sixty years [

47]. North Macedonia’s lowland summer aridity and highland semi-humid conditions correspond closely to these regional observations, supporting the consistency of hydroclimatic patterns across the region.

Expanding to South-Eastern Europe, Turkey exhibits semi-arid and dry sub-humid conditions in continental interiors and Mediterranean regions, with decreasing annual and winter precipitation since the 1970s, and seasonal increases in spring precipitation in some areas [

34]. Iraq, in contrast, is characterized by arid and semi-arid conditions covering 97% of the country, with increased dryness after 1997, particularly in northern regions [

40]. These findings reflect the sensitivity of lowland North Macedonia to summer water deficits, highlighting comparable responses to hydroclimatic variability in continental interiors and semi-arid zones.

Projections for South-Eastern Europe (1961–2050) based on multiple climate indices, including the JCI, I

DM, and I

P, indicate that the overall spatial pattern of aridity remains relatively stable, yet marked shifts toward more arid conditions are expected in the Balkan Peninsula, including North Macedonia [

65]. These large-scale trends are corroborated by ultrahigh-resolution analyses of regional bioclimate. Charalampopoulos et al. (2023) [

57], using the I

DM, projected future bioclimate changes across natural and agricultural areas, highlighting a pronounced expansion of semi-dry conditions in central, southern, and southeastern parts of North Macedonia under high-emission scenarios for the period 2071–2100. In addition, Charalampopoulos and Droulia (2025) [

58] reported increasing aridity and continentality patterns over South-Eastern Europe from 1964–2023, with semi-dry conditions expanding notably over agricultural and natural areas, particularly in Bulgaria, Serbia, and North Macedonia. The results of the present study align with these projections, demonstrating that lowland areas in North Macedonia are increasingly affected by summer aridity, whereas highlands remain comparatively buffered. This agreement underscores the robustness of the applied indices for capturing hydroclimatic gradients and supports the broader regional relevance of observed seasonal and spatial aridity trends.

Regional studies across the South-Eastern European and Mediterranean domains indicate that topography, latitude, and continentality strongly modulate seasonal aridity. In Southern Bulgaria, decreasing multiannual aridity trends were observed [

53], whereas Montenegro’s coastal summer zones exhibited semi-arid conditions [

47]. Southwestern Spain experienced increasing aridity between 1951 and 2010, particularly in historically humid northern regions, with spring and summer showing the highest water deficits [

94]. Italy shows a progressive reduction in precipitation and increasing temperatures between 1951 and 2010, leading to a widening gap between water demand and rainfall in agricultural systems [

30]. North Macedonia similarly displays summer lowland aridity, while highlands retain semi-humid conditions, confirming the generality of seasonal patterns across Mediterranean and South-Eastern European terrains. Furthermore, Greece demonstrates a gradual shift from moderate marine climates to more continental and semi-dry classes in northern and central regions, while islands remain stable [

95]. Comparable continentality–oceanity gradients were observed in the Iberian Peninsula, with maritime northern areas and continental interiors, reflecting similar topographic and latitudinal modulation of climate as seen in North Macedonia [

96]. These observations corroborate the influence of topography and latitude on spatial aridity variability, which aligns with the patterns observed in North Macedonia.

Moving eastward, Central Kazakhstan exhibits a northeast–southwest aridity gradient, with southern desert areas becoming drier and northern highlands more humid between 1960 and 2022 [

97]. Seasonal analysis revealed winter moisture gains contrasted by extreme summer aridity, consistent with North Macedonia, where lowlands are semi-dry in summer, and highlands maintain semi-humid conditions. Similarly, recent analyses across the Middle East and North Africa [

98] indicate increasing continental influences and modest aridity trends, particularly over humid regions such as the Ethiopian Highlands and Fertile Crescent, underscoring the role of large-scale circulation patterns in modulating spatial hydroclimatic.

At the European scale, continental and Mediterranean regions display heterogeneous aridity trends. In Italy, high spatial variability in aridity and continentality indices reflects mountain-induced precipitation gradients [

99]. Across Europe, long-term datasets indicate expansion of dry regions since the 1980s, particularly at low and medium altitudes in Western, Central, and Eastern Europe [

100]. According to high-resolution projections of aridity under climate change, the South Balkan Peninsula, including North Macedonia, experiences dry climates across all indices, with southern lowlands classified as semi-dry and highlands maintaining semi-humid conditions. Our findings in this study overlap with these continental-scale projections, confirming the reliability and regional representativeness of the applied indices.

Yet, certain limitations are inherent in this study. The analysis is restricted to the period 1991–2020, which constrains the assessment of longer-term trends and decadal variability. While station-based observations provide high-resolution and reliable data for the examined period, extending the temporal coverage to include earlier records or climate projections would allow a more comprehensive evaluation of hydroclimatic changes. One of the limitations is the small number of meteorological stations (13) used in the study, leading to a high degree of generalization and interpolation. Furthermore, the integration of satellite-derived datasets, such as MERRA-2 or ERA5 reanalysis products, alongside geospatial platforms like Google Earth Engine (GEE), would enable cross-validation, spatial extrapolation, and the construction of broader temporal and spatial scenarios [

4]. Incorporating these approaches would enhance the robustness and representativeness of regional aridity assessments, thereby supporting improved water resource management and climate adaptation strategies [

5,

101].

Thus, the North Macedonian patterns of semi-dry lowlands and semi-humid highlands, with summer as the critical period for water deficits, are broadly consistent with regional and extra-regional studies across South-Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, and Central Europe and Asia. This congruence validates the applicability of the JCI, IDM, and IP, indices for regional hydroclimatic assessment and underscores the relevance of these findings for water resource management, agriculture, and climate adaptation strategies.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the long-term spatio-temporal variability of aridity indices in North Macedonia from 1991 to 2020 was analyzed. For the purpose of the study datasets from 13 meteorological stations were used. Certain patterns can be identified so general conclusions can be summarized as follows:

Mean annual temperatures and mean annual precipitation sums showed spatial variability influenced by hypsometry and the proximity of major water aquatories such as Mediterranean basin. Therefore, the study area has diverse climate (from continental to mild, Mediterranean influences). However, the urban agglomeration of Skopje is affected by UHI phenomenon which leads to increasing of mean annual temperature. This fact is the cause of pronounced continentality and semi-dry conditions.

On a temporal scale the highest JCI values were recorded in 2017 and 2000 which suggest high continentality. The lowest JCI value observed was during 2014 (Moderate Marine climate class). The spatial distribution of the JCI detected three classes – moderate Marine, Transitional, and Continental climate. Moderate Marine climates are observed in the western highlands and northeastern uplands. Transitional climates is present in eastern and western regions while continental climate is dominant in the central parts of the country and in central valleys.

The monthly IDM values show the increasing of aridity from June to September. July and August belong to semi-arid classes while June is Mediterranean. This fact could have influence on agriculture in North Macedonia and create a need for expanding areas under irrigation. The seasonal values of this index indicate extremely humid climate during winter season, spring and autumn are characterized by a humid climate, while summer is characterized as semi-arid. In term of spatial changes, summer season indicates semi-arid conditions in most of North Macedonia. The annual values of the IDM indicate the following: 5 years were very humid, 16 humid, 3 semi-humid, 5 mediterranean and only one year (2000) belongs to the semi-arid category. In general, according to the IDM, North Macedonia has humid to semi-humid conditions on annual scale. Spatial distribution of the IDM indicates dominant humid, very humid and extremely humid classes.

Mean annual value of the Ip reveals dominant semi-dry (Mediterranean) influences – 20 years. Humid classes are pronounced during nine years. Similarly, just one year based on the Pinna combinative index belongs to the semi-dry conditions (2000). Spatial distribution of Ip detected humid class on almost whole meteorological stations in the country. However, three meteorological stations (Gevgelija, Demir Kapija and Strumica) showed different aridity patterns – semi-dry (Mediterranean) climate.

The MK test indicates no pronounced statistical significance in the aridity trends. The Pearson correlation test between the IDM and the NAOI is statistically significant in summer. The positive correlation in summer indicates a drying effect on the IDM in study area (linked to reduced precipitation under positive NAOI phases). A negative correlation coefficient in winter displays a wetting effect on the IDM (no statistical significance) reflecting increased moisture during negative NAOI phases.

The results of this research provide a solid basis for future studies of aridity in North Macedonia and can be of importance in numerous aspects of anthropogenic activities. Here, policy planning on a national scale, sustainable agricultural production and sustainable management of water resources (monitoring of irrigation conditions) are emphasized. Considering that increasing of aridity can be expected in the future, this will have a negative impact on traditional agriculture, which is the most widespread in the study area. Consequently, state and local authorities need to implement measures and develop plans for sustainable agriculture, particularly for crops reliant on summer precipitation (e.g. using drought-resistant crops).

Future investigations of aridity variability in North Macedonia must include a wider set of different aridity indices or implementation of remote sensing techniques in aridity detection. Also, a long-term assessment of aridity changes is desirable (by expanding used time series to the historical data). Since the aridity conditions are related to drought conditions, this phenomenon should be investigated by using the appropriate empirical methods such as: for meteorological drought (Standardized Precipitation Index, SPI), Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index, SPEI), for hydrological drought (Palmer Hydrological Drought Index, PHDI, Streamflow Drought Index SDI), for agricultural drought (Crop Moisture Index, CMI and Vegetation Condition Index, VCI). This approach provides the opportunity of comparing results between the aridity and drought and could give a valuable insight into the moisture deficit and its dynamics on a national scale.

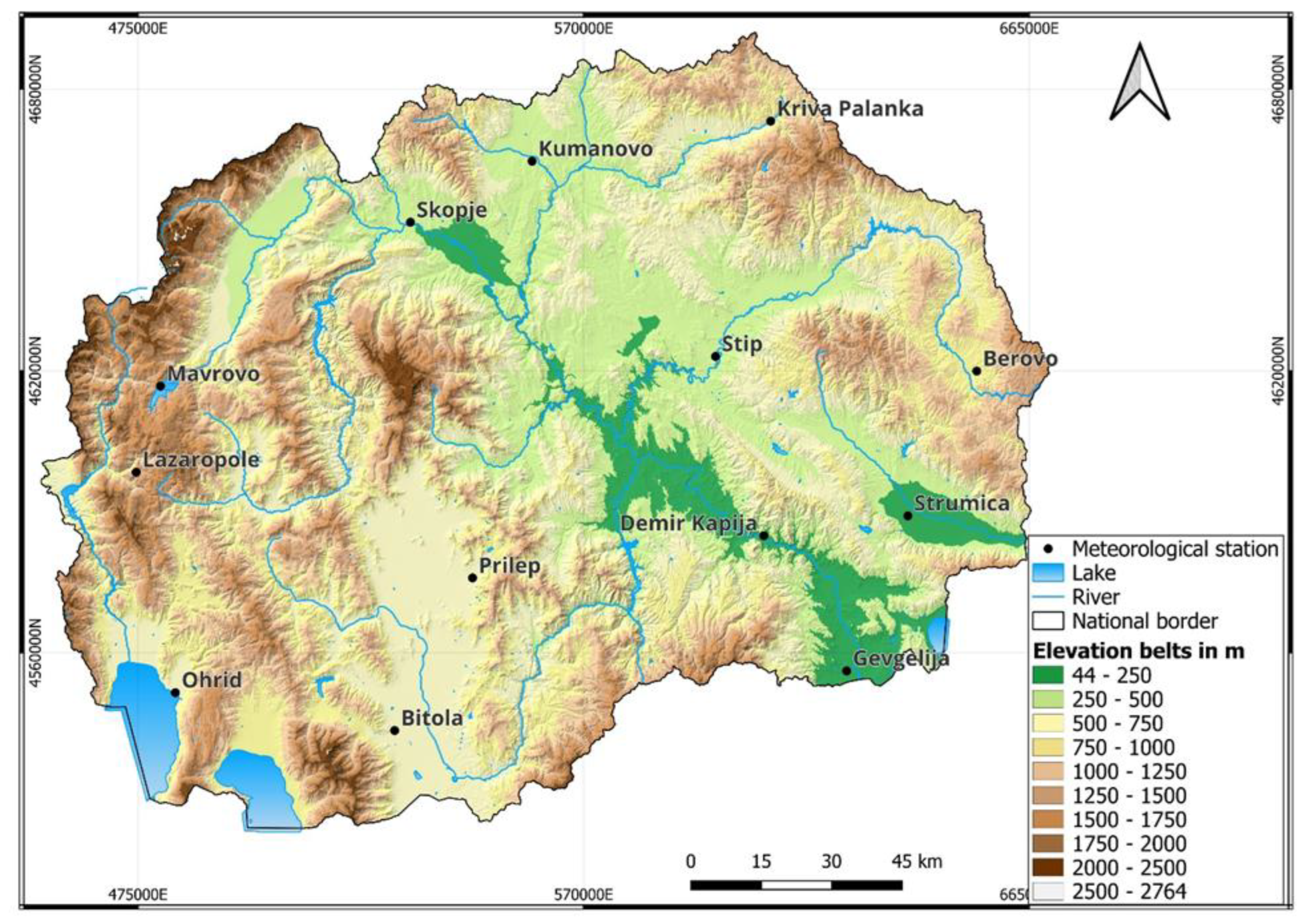

Figure 1.

Location of North Macedonia and distribution of meteorological stations.

Figure 1.

Location of North Macedonia and distribution of meteorological stations.

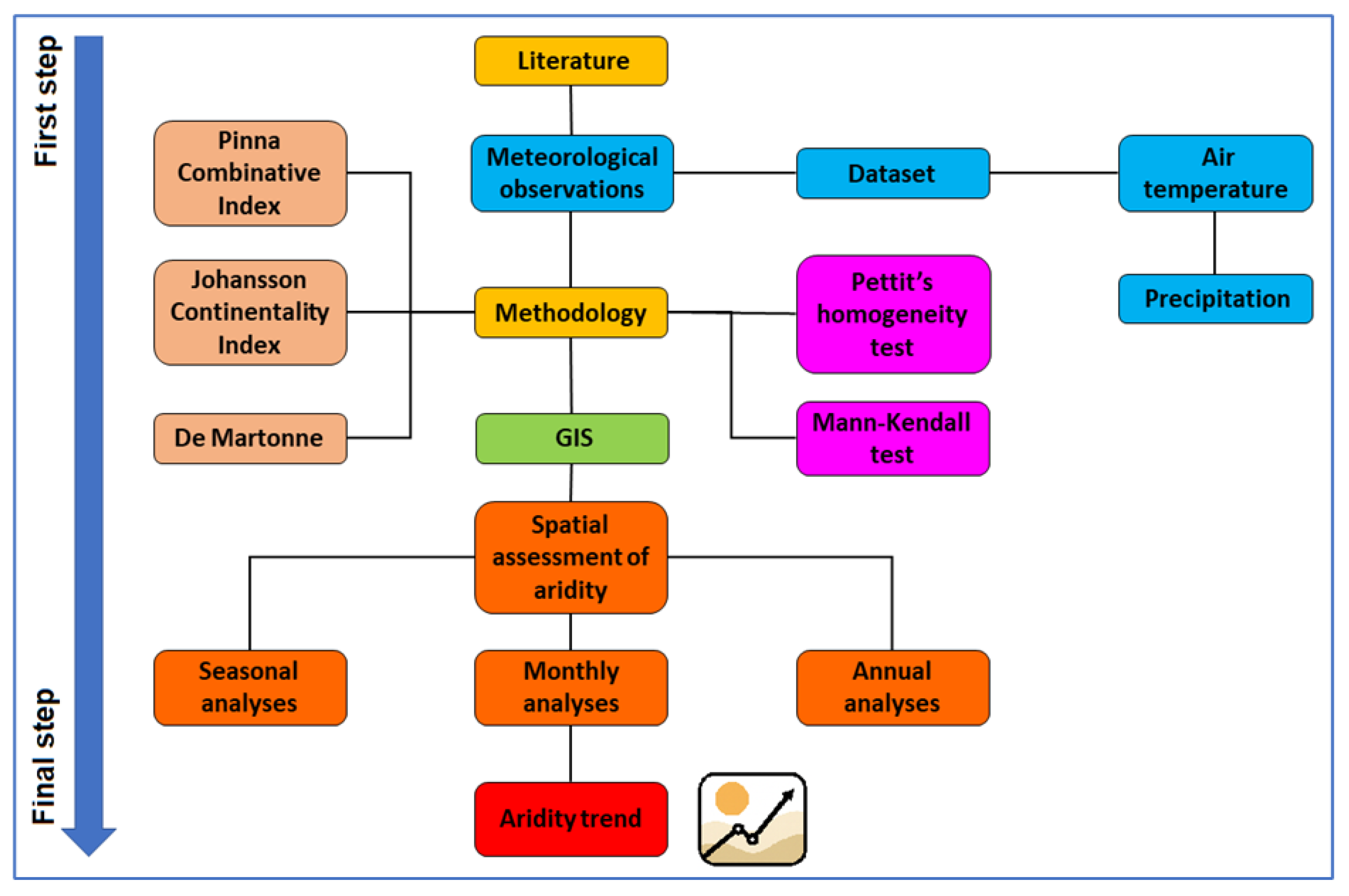

Figure 2.

Conceptual flowchart of used methodology in this study.

Figure 2.

Conceptual flowchart of used methodology in this study.

Figure 3.

Pettitt’s homogeneity test (1991-2020).

Figure 3.

Pettitt’s homogeneity test (1991-2020).

Figure 4.

Spatial variability of MAT

(A) and MAP

(B) in North Macedonia for the period 1991–2020 (according to the analyzed meteorological stations data) [

61].

Figure 4.

Spatial variability of MAT

(A) and MAP

(B) in North Macedonia for the period 1991–2020 (according to the analyzed meteorological stations data) [

61].

Figure 5.

The JCI distribution over the study area (1991–2020).

Figure 5.

The JCI distribution over the study area (1991–2020).

Figure 6.

Monthly distribution of the De Martonne aridity index.

Figure 6.

Monthly distribution of the De Martonne aridity index.

Figure 7.

Seasonal De Martonne aridity index values.

Figure 7.

Seasonal De Martonne aridity index values.

Figure 8.

Seasonal spatial distribution of IsDM; Winter

(A); Spring

(B); Summer

(C) and Autumn

(D) according to the data of meteorological stations [

61].

Figure 8.

Seasonal spatial distribution of IsDM; Winter

(A); Spring

(B); Summer

(C) and Autumn

(D) according to the data of meteorological stations [

61].

Figure 9.

Annual variation of the IDM trend in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 9.

Annual variation of the IDM trend in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 10.

Annual variation of the IDM in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 10.

Annual variation of the IDM in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 11.

Annual variation of the IP trend in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 11.

Annual variation of the IP trend in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 12.

Annual variation of the IP in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 12.

Annual variation of the IP in North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 13.

The JCI (upper), IDM (middle) and IP (bellow) graph.

Figure 13.

The JCI (upper), IDM (middle) and IP (bellow) graph.

Figure 14.

Linear regression between IDM and IP for North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Figure 14.

Linear regression between IDM and IP for North Macedonia (1991–2020).

Table 1.

List of meteorological stations.

Table 1.

List of meteorological stations.

| No. |

Meteorological station |

Latitude |

Longitude |

Altitude (m) |

| 1 |

Berovo |

41°43'00" |

022°50'56" |

837.0 |

| 2 |

Bitola |

41°02'30" |

021°21'13" |

589.0 |

| 3 |

Gevgelija |

41°08'48" |

022°30'09" |

61.0 |

| 4 |

Demir Kapija |

41°24'31" |

022°17'50" |

126.0 |

| 5 |

Kriva Palanka |

42°12'12" |

022°19'52" |

690.0 |

| 6 |

Kumanovo |

42°07'55" |

21°42'51" |

340.0 |

| 7 |

Lazaropole |

41°32'14" |

020°41'45" |

1337.0 |

| 8 |

Mavrovo |

41°42'09" |

020°45'26" |

1281.0 |

| 9 |

Ohrid |

41°06'53" |

020°47'50" |

758.0 |

| 10 |

Prilep |

41°20'01" |

021°33'13" |

675.0 |

| 11 |

Skopje |

42°00'59" |

021°23'59" |

302.0 |

| 12 |

Strumica |

41°26'31" |

022°39'55" |

223.5 |

| 13 |

Štip |

41°45'13" |

022°10'49" |

326.6 |

Table 2.

Köppen climate type.

Table 2.

Köppen climate type.

| Köppen climate type |

Description |

Mean annual temp. (°C) |

| Cfa |

Humid subtropical, hot summers, mild wet winters |

11–12 |

| Cfb |

Temperate oceanic, moderate summers, cool winters, uniform precipitation |

10–11 |

| Dfb |

Humid continental, cold winters, warm summers, pronounced seasonal contrasts |

<8 |

Table 3.

Johansson continentality index categories by [

65].

Table 3.

Johansson continentality index categories by [

65].

| JCI |

Climate classification |

| >20 |

Marine |

| (20 – 32) |

Moderate marine |

| (32–34) |

Transitional |

| <34 |

Continental |

Table 4.

De Martonne index climatic classification [

50].

Table 4.

De Martonne index climatic classification [

50].

| Climate type |

Values of IDM

|

| Arid |

IDM < 10 |

| Semi-arid |

10 ≤ IDM < 20 |

| Mediterranean |

20 ≤ IDM < 24 |

| Semi-humid |

24 ≤ IDM < 28 |

| Humid |

28 ≤ IDM < 35 |

| Very-humid |

35 ≤ IDM ≤ 55 |

| Extremely humid |

IDM > 55 |

Table 5.

The Pinna combinative index (I

p) classification [

65].

Table 5.

The Pinna combinative index (I

p) classification [

65].

| Climate type |

Values of Ip

|

| Dry |

Ip < 10 |

| Semi-dry (Mediterranean) |

10 < Ip < 20 |

| Humid |

Ip > 20 |

Table 6.

Climate classification according to JCI.

Table 6.

Climate classification according to JCI.

| Station |

JCI |

Climate classification |

| Berovo |

32.7 |

Transitional |

| Bitola |

39.4 |

Continental |

| Gevgelija |

38.2 |

Continental |

| Demir Kapija |

39.7 |

Continental |

| Kriva Palanka |

30.9 |

Moderate marine |

| Kumanovo |

38.6 |

Continental |

| Lazaropole |

27.2 |

Moderate marine |

| Mavrovo |

30.1 |

Moderate marine |

| Ohrid |

32.4 |

Transitional |

| Prilep |

37.1 |

Continental |

| Skopje |

38.8 |

Continental |

| Strumica |

38.5 |

Continental |

| Štip |

38.4 |

Continental |

Table 7.

Seasonal De Martonne index (IsDM) for each meteorological station.

Table 7.

Seasonal De Martonne index (IsDM) for each meteorological station.

| Station |

Winter IsDM

|

Spring IsDM

|

Summer IsDM

|

Autumn IsDM

|

| Berovo |

63.8 |

37.6 |

24.0 |

53.0 |

| Bitola |

59.8 |

32.5 |

18.6 |

57.7 |

| Gevgelija |

54.9 |

30.9 |

12.3 |

50.3 |

| D. Kapija |

64.4 |

28.7 |

15.8 |

49.0 |

| K. Palanka |

60.2 |

33.2 |

21.5 |

53.8 |

| Kumanovo |

39.6 |

26.6 |

19.7 |

25.9 |

| Lazaropole |

134.0 |

65.1 |

23.4 |

70.8 |

| Mavrovo |

148.5 |

66.8 |

20.9 |

66.8 |

| Ohrid |

49.6 |

33.7 |

13.8 |

49.6 |

| Prilep |

34.3 |

25.5 |

20.0 |

26.0 |

| Skopje |

35.4 |

26.7 |

17.8 |

24.1 |

| Strumica |

46.4 |

26.0 |

17.9 |

27.2 |

| Štip |

38.7 |

24.0 |

17.9 |

23.9 |

Table 8.

Seasonal IDM per year (1991-2020).

Table 8.

Seasonal IDM per year (1991-2020).

| Year |

Winter |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

| 1991 |

116.32 |

118.55 |

50.04 |

97.09 |

| 1992 |

123.50 |

112.55 |

34.84 |

105.74 |

| 1993 |

110.15 |

84.39 |

15.46 |

88.22 |

| 1994 |

65.13 |

78.67 |

27.64 |

82.51 |

| 1995 |

106.33 |

85.34 |

41.49 |

91.24 |

| 1996 |

95.66 |

102.32 |

39.52 |

88.75 |

| 1997 |

83.65 |

71.39 |

15.82 |

102.04 |

| 1998 |

93.88 |

81.04 |

16.51 |

126.98 |

| 1999 |

111.45 |

86.17 |

32.55 |

97.22 |

| 2000 |

94.75 |

70.66 |

12.57 |

80.33 |

| 2001 |

93.12 |

80.70 |

13.84 |

73.07 |

| 2002 |

109.91 |

84.51 |

23.94 |

112.92 |

| 2003 |

119.55 |

80.05 |

11.23 |

95.53 |

| 2004 |

78.83 |

77.58 |

24.59 |

100.83 |

| 2005 |

90.06 |

83.17 |

19.64 |

90.62 |

| 2006 |

87.21 |

83.61 |

23.47 |

85.29 |

| 2007 |

92.21 |

81.71 |

9.99 |

102.21 |

| 2008 |

75.45 |

78.69 |

22.56 |

93.22 |

| 2009 |

100.08 |

81.65 |

19.33 |

99.62 |

| 2010 |

95.34 |

72.19 |

12.79 |

114.73 |

| 2011 |

71.29 |

65.05 |

14.28 |

78.33 |

| 2012 |

99.70 |

80.59 |

9.61 |

100.28 |

| 2013 |

90.96 |

83.16 |

17.80 |

85.49 |

| 2014 |

80.12 |

93.88 |

29.75 |

124.93 |

| 2015 |

114.65 |

81.68 |

12.42 |

91.17 |

| 2016 |

84.45 |

80.64 |

22.84 |

79.40 |

| 2017 |

87.16 |

84.09 |

14.28 |

92.38 |

| 2018 |

106.82 |

84.60 |

20.44 |

70.21 |

| 2019 |

92.05 |

88.62 |

14.27 |

76.02 |

| 2020 |

88.94 |

84.28 |

16.63 |

76.84 |

Table 9.

Annual IsDM and climate type by station.

Table 9.

Annual IsDM and climate type by station.

| Station |

Annual IsDM

|

Climate Type |

| Berovo |

44.6 |

Very-humid |

| Bitola |

42.1 |

Very-humid |

| Gevgelija |

37.1 |

Very-humid |

| D. Kapija |

39.4 |

Very-humid |

| K. Palanka |

42.2 |

Very-humid |

| Kumanovo |

27.9 |

Semi-humid |

| Lazaropole |

73.3 |

Extremely humid |

| Mavrovo |

75.7 |

Extremely humid |

| Ohrid |

36.7 |

Very-humid |

| Prilep |

26.4 |

Semi-humid |

| Skopje |

26.0 |

Semi-humid |

| Strumica |

29.4 |

Humid |

| Štip |

26.1 |

Semi-humid |

Table 10.

Annual IP and climate type by station.

Table 10.

Annual IP and climate type by station.

| Station |

Pma (mm) |

Tma (°C) |

P′d (mm) |

T′d (°C) |

Ip

|

Climate type |

| Berovo |

646.2 |

9.2 |

40.2 |

0.7 |

39.4 |

Humid |

| Bitola |

625.3 |

11.9 |

32.9 |

22.7 |

20.3 |

Humid |

| Gevgelija |

711.8 |

15.5 |

25.8 |

26.7 |

18.2 |

Semi-dry (Mediter.) |

| D. Kapija |

575.4 |

14.3 |

30.8 |

25.9 |

17.0 |

Semi-dry (Mediter.) |

| K. Palanka |

661.1 |

10.7 |

39.4 |

2.0 |

35.7 |

Humid |

| Kumanovo |

534.8 |

12.7 |

30.1 |

3.3 |

25.4 |

Humid |

| Lazaropole |

1058.5 |

7.6 |

42.2 |

-0.7 |

39.5 |

Humid |

| Mavrovo |

1046.0 |

7.6 |

40.8 |

-1.1 |

38.6 |

Humid |

| Ohrid |

710.9 |

11.8 |

27.5 |

3.4 |

21.5 |

Humid |

| Prilep |

531.5 |

11.9 |

32.0 |

2.0 |

30.6 |

Humid |

| Skopje |

502.4 |

13.2 |

34.1 |

1.1 |

23.9 |

Humid |

| Strumica |

594.6 |

13.4 |

36.5 |

2.9 |

19.1 |

Semi-dry (Mediter.) |

| Štip |

472.1 |

13.5 |

27.2 |

3.1 |

21.5 |

Humid |

Table 11.

Statistical summary of Johansson Continentality Index (JCI), De Martonne aridity index (IDM), and Pinna index (Ip) based on Mann–Kendall statistics, and the magnitude of trends (β) calculated by Sen’s slope estimator.

Table 11.

Statistical summary of Johansson Continentality Index (JCI), De Martonne aridity index (IDM), and Pinna index (Ip) based on Mann–Kendall statistics, and the magnitude of trends (β) calculated by Sen’s slope estimator.

| Station |

Elevation (m a.s.l.) |

Index |

ZMK

|

Annual Mean |

Sen's Slope β (units/yr) |

Trend significance (α=0.05) |

| Mavrovo |

1250 |

JCI |

0.52 |

30.1 |

0.007 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.21 |

71.6 |

-0.015 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.14 |

28.4 |

-0.010 |

No |

| Lazaropole |

1330 |

JCI |

0.15 |

27.2 |

0.004 |

No |

| IDM

|

0.09 |

72.9 |

0.008 |

No |

| IP

|

0.18 |

29.1 |

0.012 |

No |

| Berovo |

837 |

JCI |

-0.08 |

32.7 |

-0.002 |

No |

| IDM

|

0.32 |

35.2 |

0.022 |

No |

| IP

|

0.27 |

24.8 |

0.018 |

No |

| Bitola |

688 |

JCI |

-0.62 |

39.4 |

-0.008 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.44 |

32.1 |

-0.030 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.36 |

23.5 |

-0.025 |

No |

| Gevgelija |

61 |

JCI |

-0.85 |

38.2 |

-0.012 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.62 |

24.8 |

-0.040 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.53 |

19.2 |

-0.035 |

No |

| D. Kapija |

165 |

JCI |

-0.98 |

39.7 |

-0.015 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.75 |

23.4 |

-0.048 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.68 |

18.1 |

-0.042 |

No |

| K. Palanka |

485 |

JCI |

0.28 |

30.9 |

0.005 |

No |

| IDM

|

0.14 |

34.7 |

0.010 |

No |

| IP

|

0.21 |

24.3 |

0.015 |

No |

| Kumanovo |

324 |

JCI |

-0.45 |

38.6 |

-0.006 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.32 |

30.5 |

-0.022 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.27 |

22.1 |

-0.018 |

No |

| Ohrid |

695 |

JCI |

0.22 |

32.4 |

0.003 |

No |

| IDM

|

0.39 |

36.8 |

0.028 |

No |

| IP

|

0.36 |

25.6 |

0.025 |

No |

| Prilep |

625 |

JCI |

-0.12 |

37.2 |

-0.001 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.18 |

33.4 |

-0.012 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.09 |

23.9 |

-0.008 |

No |

| Skopje |

247 |

JCI |

-1.41 |

38.8 |

-0.009 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.50 |

22.3 |

-0.035 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.39 |

18.7 |

-0.030 |

No |

| Strumica |

268 |

JCI |

-0.75 |

38.5 |

-0.010 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.57 |

28.6 |

-0.038 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.50 |

21.4 |

-0.032 |

No |

| Štip |

300 |

JCI |

-0.68 |

38.4 |

-0.011 |

No |

| IDM

|

-0.98 |

22.2 |

-0.065 |

No |

| IP

|

-0.85 |

18.2 |

-0.055 |

No |

Table 12.

Seasonal and annual correlation coefficients between the IDM and the North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAOI) and Southern Oscillation Index (SOI).

Table 12.

Seasonal and annual correlation coefficients between the IDM and the North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAOI) and Southern Oscillation Index (SOI).

| Index |

Winter |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

Year |

| NAOI |

-0.31 |

-0.18 |

0.45 |

-0.14 |

-0.16 |

| SOI |

0.13 |

-0.05 |

0.03 |

0.19 |

0.14 |