Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Biochemical Analysis

2.1.1. Lipid Profile

2.1.2. IGF-1

2.1.3. Ox-LDL

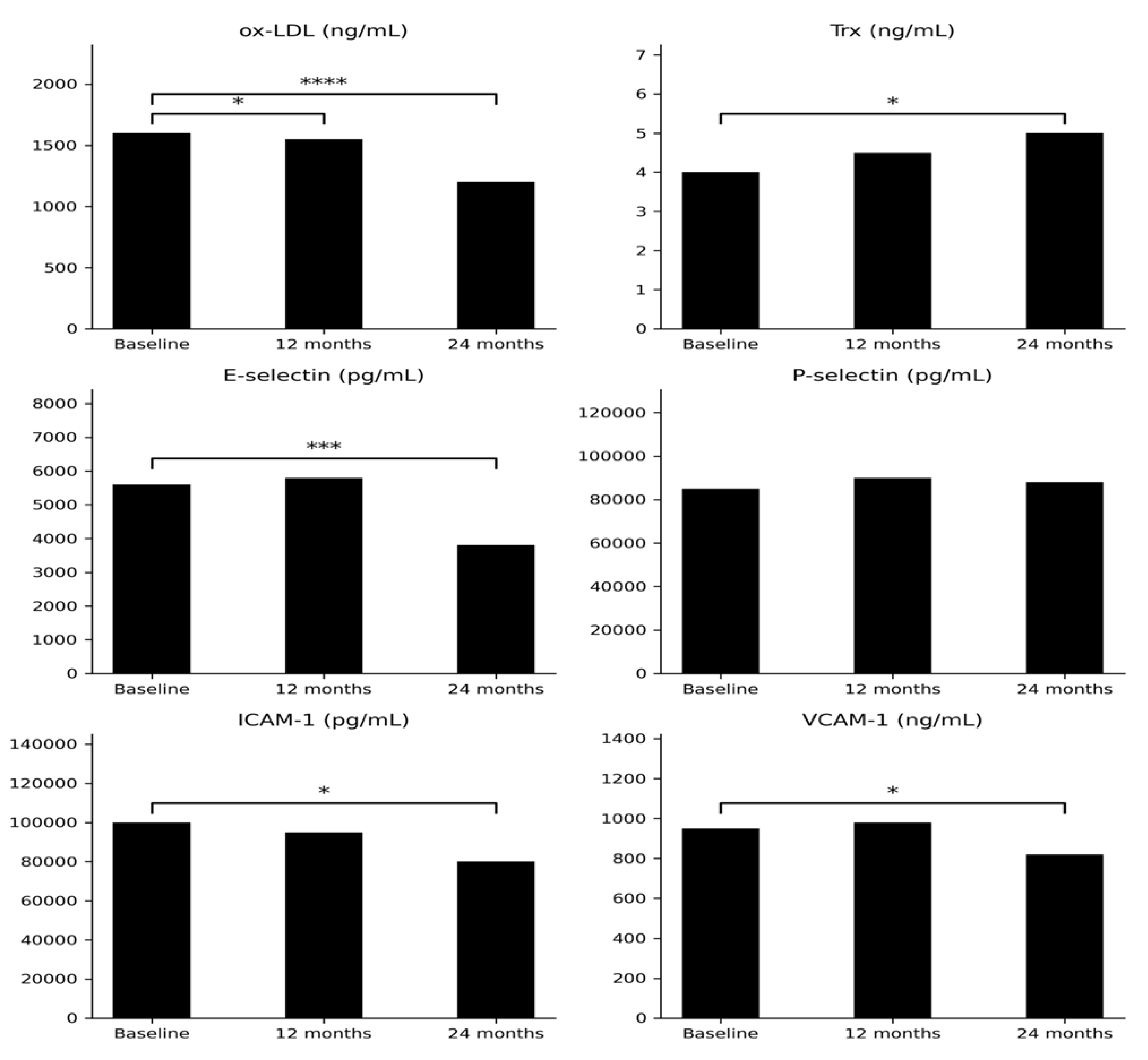

2.1.4. Thx

2.1.4. OGG-1

2.1.4. E-selectin and P-selectin

2.1.4. I-CAM1 and VCAM-1

Body Composition Evaluation

2.2. Correlations

2.2.1. Ox-LDL and Related Correlations

2.2.2. Endothelial Adhesion Molecules

2.2.3. Redox-Related Marker

2.2.4. Lipid Profile Correlations

2.2.5. Body Composition and Bone Parameters

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Studied Population

4.2. Biochemical Measurement

Statistical Analysis

Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry and Body Composition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Brooke, AM; Monson, JP. Adult growth hormone deficiency. Clin Med (Lond) 2003, 3(1), 15–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratku, B; Sebestyén, V; Erdei, A; Nagy, EV; Szabó, Z; Somodi, S. Effects of adult growth hormone deficiency and replacement therapy on the cardiometabolic risk profile. Pituitary 2022, 25(2), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, L; Tirabassi, G; Muscogiuri, G; Di Somma, C; Colao, A; Balercia, G. Impact of adult growth hormone deficiency on metabolic profile and cardiovascular risk [Review]. Endocr J 2015, 62(12), 1037–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, G; Di Somma, C; Grasso, LF; Savanelli, MC; Colao, A; Pivonello, R. The cardiovascular system in growth hormone excess and growth hormone deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest 2012, 35(11), 1021–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kościuszko, M; Buczyńska, A; Hryniewicka, J; Jankowska, D; Adamska, A; Siewko, K; Jacewicz-Święcka, M; Zaniuk, M; Krętowski, AJ; Popławska-Kita, A. Early Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of rhGH Therapy in Adult Patients with Severe Growth Hormone Deficiency: Impact on Oxidative Stress Parameters. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26(12), 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, R; Janez, A; Mikhailidis, DP; Poredos, P; Blinc, A; Sabovic, M; Studen, KB; Schernthaner, GH; Anagnostis, P; Antignani, PL; Jensterle, M. Growth Hormone, Atherosclerosis and Peripheral Arterial Disease: Exploring the Spectrum from Acromegaly to Growth Hormone Deficiency. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2024, 22(1), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, S; Morris, M; Bouloux, PM. Growth hormone deficiency and atherosclerosis--is there a link? Growth Horm IGF Res 1999, 9 Suppl A, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binay, C; Simsek, E; Yıldırım, A; Kosger, P; Demiral, M; Kılıç, Z. Growth hormone and the risk of atherosclerosis in growth hormone-deficient children. Growth Horm IGF Res 2015, 25(6), 294–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munno, M; Mallia, A; Greco, A; Modafferi, G; Banfi, C; Eligini, S. Radical Oxygen Species, Oxidized Low-Density Lipoproteins, and Lectin-like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor 1: A Vicious Circle in Atherosclerotic Process. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13(5), 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominacini, L; Rigoni, A; Pasini, AF; Garbin, U; Davoli, A; Campagnola, M; Pastorino, AM; Lo Cascio, V; Sawamura, T. The binding of oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) to ox-LDL receptor-1 reduces the intracellular concentration of nitric oxide in endothelial cells through an increased production of superoxide. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276(17), 13750–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H; Wang, ZH; Kong, J; Yang, MY; Jiang, GH; Wang, XP; Zhong, M; Zhang, Y; Deng, JT; Zhang, W. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein-dependent platelet-derived microvesicles trigger procoagulant effects and amplify oxidative stress. Mol Med. 2012, 18(1), 159–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominacini, L; Garbin, U; Pasini, AF; Davoli, A; Campagnola, M; Contessi, GB; Pastorino, AM; Lo Cascio, V. Antioxidants inhibit the expression of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 induced by oxidized LDL on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997, 22(1-2), 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschmied, J; Haendeler, J. Thioredoxin-1 and endothelial cell aging: role in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11(7), 1733–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A; Martin, SG. The thioredoxin system: a key target in tumour and endothelial cells. Br J Radiol 2008, 81 Spec No 1, S57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y; Ji, N; Gong, X; Ni, S; Xu, L; Zhang, H. Thioredoxin-1 attenuates atherosclerosis development through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. Endocrine 2020, 70(1), 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, MJ; Gordon, JL; Gearing, AJ; Pigott, R; Woolf, N; Katz, D; Kyriakopoulos, A. The expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM, and E-selectin in human atherosclerosis. J Pathol 1993, 171(3), 223–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerath, E; Towne, B; Blangero, J; Siervogel, RM. The relationship of soluble ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin and E-selectin to cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthy men and women. Ann Hum Biol. 2001, 28(6), 664–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jude, EB; Douglas, JT; Anderson, SG; Young, MJ; Boulton, AJ. Circulating cellular adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P- and E-selectin in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Eur J Intern Med 2002, 13(3), 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, MML; Ye, J; Luna, L; Hildrestrand, G; Bjørås, K; Scheffler, K; Bjørås, M. Impact of Oxidative DNA Damage and the Role of DNA Glycosylases in Neurological Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(23), 12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anene-Nzelu, CG; Li, PY; Luu, TDA; Ng, SL; Tiang, Z; Pan, B; Tan, WLW; Ackers-Johnson, M; Chen, CK; Lim, YP; Qin, RWM; Chua, WW; Yi, LX; Foo, RS; Nakabeppu, Y. 8-Oxoguanine DNA Glycosylase (OGG1) Deficiency Exacerbates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 9180267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomair, A; Alamri, A; Shaik, J; Aljafari, S; Ba Abdullah, M; Alanazi, M. Association between polymorphisms of the DNA repair genes RAD51 and OGG1 and risk of cardiovascular disease. Mol Med Rep.;Epub 2024, 29(3), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C; Wang, SR; Zhang, SY; Yu, SJ; Jiang, CX; Zhi, MH; Huang, Y. Effects of recombinant human growth hormone on acute lung injury in endotoxemic rats. Inflamm Res 2006, 55(11), 491–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, TK; Fisker, S; Dall, R; Ledet, T; Jørgensen, JO; Rasmussen, LM. Growth hormone increases vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression: in vivo and in vitro evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89(2), 909–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M; Toyomura, J; Yagi, T; Kuboki, K; Morita, T; Sugihara, H; Hirose, T; Minami, S; Yoshino, G. Role of growth hormone signaling pathways in the development of atherosclerosis. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2020, 53-54, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, DV; Spina, LD; de Lima Oliveira Brasil, RR; da Silva, EM; Lobo, PM; Salles, E; Coeli, CM; Conceição, FL; Vaisman, M. Carotid artery intima-media thickness and lipid profile in adults with growth hormone deficiency after long-term growth hormone replacement. Metabolism 2005, 54(3), 321–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, ML; Merriam, GR; Kargi, AY. Adult growth hormone deficiency - benefits, side effects, and risks of growth hormone replacement. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, Y; Sukhanov, S; Anwar, A; Shai, SY; Delafontaine, P. IGF-1, oxidative stress and atheroprotection. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010, 21(4), 245–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, ME; de'Angelis, G; Camacho-Hübner, C; Giovannelli, G; Ziveri, MA; Bacchini, PL; Bernasconi, S; Sansebastiano, G; Savage, MO. Relationships between serum IGF-1, IGFBP-2, interleukin-1beta and interleukin-6 in inflammatory bowel disease. Horm Res. 2004, 61(4), 159–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chábová, V; Perusicová, J; Tesar, V; Zabka, J; Merta, M; Rychlík, T; Zima, T; Bradová, V. Vztah plazmatických hladin IGF-I, leptinu a TNF-alfa u diabetiků [Relation between plasma levels of IGF-I, leptin and TNF-alpha in diabetics]. Cas Lek Cesk 1999, 138(7), 217–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haywood, NJ; Slater, TA; Matthews, CJ; Wheatcroft, SB. The insulin like growth factor and binding protein family: Novel therapeutic targets in obesity & diabetes. Mol Metab 2019, 19, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samerria, S; Radovick, S. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Targeting GH and IGF-1 in the Management of Obesity: Insights from the Interplay between These Hormones and Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(11), 9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M; Brixen, K; Hagen, C; Frystyk, J; Nielsen, TL. Positive associations between serum levels of IGF-I and subcutaneous fat depots in young men. The Odense Androgen Study. Growth Horm IGF Res 2012, 22(3-4), 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidlingmaier, M; Friedrich, N; Emeny, RT; Spranger, J; Wolthers, OD; Roswall, J; Körner, A; Obermayer-Pietsch, B; Hübener, C; Dahlgren, J; Frystyk, J; Pfeiffer, AF; Doering, A; Bielohuby, M; Wallaschofski, H; Arafat, AM. Reference intervals for insulin-like growth factor-1 (igf-i) from birth to senescence: results from a multicenter study using a new automated chemiluminescence IGF-I immunoassay conforming to recent international recommendations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99(5), 1712–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, BA; Johannsson, G; Shalet, SM; Simpson, H; Sonken, PH. Treatment of growth hormone deficiency in adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85(3), 933–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, JS; Jørgensen, JO; Pedersen, SA; Møller, J; Jørgensen, J; Skakkeboek, NE. Effects of growth hormone on body composition in adults. Horm Res. 1990, 33 Suppl 4, 61–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsson, G; Rosén, T; Bosaeus, I; Sjöström, L; Bengtsson, BA. Two years of growth hormone (GH) treatment increases bone mineral content and density in hypopituitary patients with adult-onset GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996, 81(8), 2865–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, F; Cuneo, RC; Hesp, R; Sönksen, PH. The effects of treatment with recombinant human growth hormone on body composition and metabolism in adults with growth hormone deficiency. N Engl J Med 1989, 321(26), 1797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, JO; et al. Growth hormone therapy in adults: metabolic effects and dose-response relationships. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994, 78(5), 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A; Holmes, SJ; Adams, JE; Shalet, SM. Long-term change in the bone mineral density of adults with adult onset growth hormone (GH) deficiency in response to short or long-term GH replacement therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1998, 48(4), 463–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R; Guo, Q; Xiao, Y; Guo, Q; Huang, Y; Li, C; Luo, X. Endocrine role of bone in the regulation of energy metabolism. Bone Res 2021, 9(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y; Lin, X. Challenges and advances in the management of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Adv Res. Epub. 2025, 71, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangasparan, S; Kamisah, Y; Ugusman, A; Mohamad Anuar, NN; Ibrahim, N'. Unravelling the Mechanisms of Oxidised Low-Density Lipoprotein in Cardiovascular Health: Current Evidence from In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(24), 13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colao, A; Di Somma, C; Savanelli, MC; De Leo, M; Lombardi, G. Beginning to end: cardiovascular implications of growth hormone (GH) deficiency and GH therapy. Growth Horm IGF Res 2006, 16 Suppl A, S41–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, L.; et al. IGF-1 reduces the apoptosis of endothelial progenitor cells induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein by the suppressing caspasse-3 activity. Cell Res 2008, 18 Suppl 1, S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberacker, T; Kraft, L; Schanz, M; Latus, J; Schricker, S. The Importance of Thioredoxin-1 in Health and Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12(5), 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andoh, T; Chock, PB; Chiueh, CC. The roles of thioredoxin in protection against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277(12), 9655–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, R; Zhang, W; Qu, X; Xiang, Y; Ji, M. Molecular Duality of OGG1: From Genomic Guardian to Redox-Sensitive Modulator in Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025, 14(8), 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Duarte, D; Madrazo-Atutxa, A; Soto-Moreno, A; Leal-Cerro, A. Measurement of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with hypopituitarism and severe deficiency adult growth hormone deficiency. Pituitary 2012, 15(4), 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, A; Di Segni, C; Bruno, C; Olivieri, G; Guidi, F; Silvestrini, A; Meucci, E; Orlando, P; Silvestri, S; Tiano, L; Pontecorvi, A. Oxidative stress in adult growth hormone deficiency: different plasma antioxidant patterns in comparison with metabolic syndrome. Endocrine 2018, 59(1), 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudling, M; Angelin, B. Growth hormone reduces plasma cholesterol in LDL receptor-deficient mice. FASEB J 2001, 15(8), 1350–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, B; Patti, L; Oliviero, U; Longobardi, S; Pardo, F; Vitale, F; Fazio, S; Di Rella, F; Biondi, B; Lombardi, G; Saccà, L. Increased arterial intima-media thickness in childhood-onset growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82(5), 1378–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, ER; et al. Endothelial function in growth hormone-deficient adults before and after growth hormone replacement therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84(12), 4531–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M; et al. Growth hormone replacement improves vascular reactivity in growth hormone-deficient adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84(6), 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C; Andersson, B; Lönn, L; Bengtsson, BA; Svensson, J; Johannsson, G. Growth hormone reduces inflammation in postmenopausal women with abdominal obesity: a 12-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92(7), 2644–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulhem, A; Moulla, Y; Klöting, N; Ebert, T; Tönjes, A; Fasshauer, M; Dietrich, A; Schön, MR; Stumvoll, M; Richter, V; Blüher, M. Circulating cell adhesion molecules in metabolically healthy obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2021, 45(2), 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K; Sera, Y; Abe, Y; Tominaga, T; Horikami, K; Hirao, K; Ueki, Y; Miyake, S. High serum concentrations of soluble E-selectin correlate with obesity but not fat distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2002, 51(7), 932–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initially | After 12 mth | After 24 mth | p* value (0 vs 12 mth) |

p** value (0 vs 24 mth) |

|

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | 47.07 (8.57-138.8) |

155.1 (36.04-265.1) |

153.19 (58.02-303.9) |

<0.001 | <0.001 |

|

Ox-LDL (ng/mL) |

1643 (1233-1910) |

1623 (1066-2154) |

1187 (919.5-1887) |

<0.05 | <0.00001 |

|

Trx (ng/mL) |

3.90 (2.66-6.88) |

4.59 (2.18-11.6) |

5.1 (2.7-10.2) |

0.38 | <0.05 |

|

E-selectin (pg/mL) |

5736 (1043-14414) |

5649 (2040-9500) |

3828 (717.4-7692) |

0.54 | <0.001 |

|

P-selectin (pg/mL) |

83493 (35819-147352) |

95089 (37656-188437) |

91296 (41620-121511) |

0.20 | 0.37 |

|

ICAM-1 (pg/mL) |

99269 (44598-130792) |

102415 (38572-146950) |

79565 (23092-129154) |

0.79 | <0.05 |

| VCAM-1 (ng/mL) | 953.8 (753.1-1258) |

1001 (761-1394) |

838.1 (532-993.7) |

0.62 | =0.05 |

|

OGG-1 (ng/mL) |

4.14 (2.53-5.7) |

5.42 (2.4-8.63) |

6.8 (3.7-12.8) |

0.65 | <0.05 |

|

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

201 (114-302) |

199 (114-295) |

200.4 (114-302) |

0.69 | 0.13 |

|

LDL (mg/dL) |

126 (65-219) |

131 (58-216) |

127 (65-219) |

0.20 | 0.49 |

|

HDL (mg/dL) |

43 (24-85) |

50 (27-80) |

46.6 (24-79) |

0.20 | 0.09 |

|

TG (mg/dL) |

120 (51-684) |

120.5 (45-326) |

153.3 (51-684) |

0.67 | 0.35 |

| Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initially | After 12 mth | After 24 mth | p* value (0 vs 12 mth) |

p** value (0 vs 24 mth) |

|

| Total mass (kg) | 78.6 (39.6-167.3) |

78.0 (62.3-156) |

86.9 (59.8-167.3) |

0.51 | 0.05 |

| Tissue fat % | 37.5 (27.4-50.4) |

38.4 (26.7-48.7) |

39.7 (27.4-60.4) |

0.04 | 0.001 |

| Fat tissue (g) | 28434 (13891-82462) |

29937 (16939-67385) |

33868 (16881-82462) |

0.08 | 0.05 |

| Lean mass (g) | 48646 (23996-81228) |

45550 (36530-84977) |

50021 (34296-81228) |

0.49 | 0.0008 |

| BMC | 2547 (1261-3778) |

2568 (1770-3650) |

2731 (1844-3778) |

0.42 | 0.72 |

| L1-L4 BMD | 1.09 (0.8-1.6) |

1.1 (0.9-1.5) |

1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

0.73 | 0.04 |

| L1-L4 T score | -1.1 (-3.4-3.2) |

-0.3 (-2.0-2.4) |

-0.1 (-2.5-3.2) |

0.17 | 0.1 |

| L1-L4 Z score | -1.1 (-3.7-3.0) |

-0.9 (-2.3-2.0) |

-0.3 (-2.2-3.0) |

0.73 | 0.13 |

| Neck BMD | 0.95 (0.7-1.4) |

0.96 (0.77-1.5) |

1.04 (0.74-1.4) |

0.29 | 0.0002 |

| Neck T score | -0.8 (-2.1-2.3) |

-0.6 (-1.9-2.5) |

-0.63 (-2.1-2.3) |

0.79 | 0.92 |

| Neck Z score | -0.9 (-2.2-2.0) |

-1.0 (-2.0-2.3) |

-0.43 (-2.1-2.0) |

0.72 | 0.0018 |

| Parameters | Initially | After 12 months | After 24 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ox-LDL (ng/mL) vs P-selectin (pg/mL) | NS | NS | p=0.02 R=0.60 |

| Ox-LDL (ng/mL) vs Lean (g) | NS | p=0.02 R=0.63 |

NS |

| E-selectin (pg/mL) vs VCAM-1 (ng/mL) | NS | NS | p=0.05 R=0.57 |

| E-selectin (pg/mL) vs HDL (mg/dL) | NS | NS | p=0.01 R=-0.67 |

| E-selectin (pg/mL) vs Waist (cm) | NS | NS | p=0.04 R=0.57 |

| Trx (ng/mL) vs Tissue (g) | NS | NS | p=0.04 R=0.71 |

| Trx (ng/mL) vs Vitamin D (mg/dL) | NS | NS | p=0.01 R=-0.69 |

| Trx (ng/mL) vs Fat (g) | NS | NS | p=0.01 R=0.71 |

| ICAM-1 (pg/mL) vs BMI (kg/m2) | NS | NS | p=0.04 R=0.55 |

| ICAM-1 (pg/mL) vs Waist (cm) | NS | p=0.03 R=0.58 |

p=0.04 R=0.57 |

| ICAM-1 (pg/mL) vs Hip (cm) | NS | NS | p=0.02 R=0.61 |

| ICAM-1 (pg/mL) vs LDL (mg/L) | NS | NS | p=0.04 R=-0.57 |

| P-selectin (pg/mL) vs BMI (kg/m2) | NS | NS | p=0.02 R=0.64 |

| P-selectin (pg/mL) vs Tissue (g) | NS | NS | p=0.03 R=0.63 |

| P-selectin (pg/mL) vs Fat (g) | NS | p=0.04 R=0.57 |

NS |

| VCAM-1 (ng/mL) vs glucose (mg/dL) | NS | NS | p=0.03 R=0.58 |

| LDL (mg/dL) vs L1-L4 Z-score | NS | NS | p=0.03 R=-0.58 |

| LDL (mg/dL) vs Lean (g) | NS | NS | p=0.01 R=-0.33 |

| HDL (mg/dL) vs IGF-1 (ng/mL) | NS | NS | p=0.02 R=-0.59 |

| HDL (mg/dL) vs Lean (g) | NS | p<0.01 R=-0.73 |

p=0.01 R=-0.68 |

| TG (mg/dL) vs L1-L4 T-score | NS | NS | p=0.03 R=0.60 |

| TG (mg/dL) vs L1-L4 Z-score | NS | NS | p=0.05 R=0.54 |

| Lean (g) vs L1-L4 BMD | NS | p<0.001 R=0.78 |

p=0.05 R=0.55 |

| Lean (g) vs L1-L4 T-score | NS | p=0.01 R=0.67 |

NS |

| Lean (g) vs L1-L4 Z-score | NS | p=0.04 R=0.53 |

NS |

| Lean (g) vs Neck BMD | NS | p<0.01 R=0.72 |

p=0.01 R=0.69 |

| Lean (g) vs Neck T-score | NS | p=0.02 R=0.68 |

p=0.03 R=0.60 |

| Lean (g) vs Neck Z-score | NS | p=0.01 R=0.67 |

NS |

| Sex | Age (years) | Treatment (before rhGH) |

Dose of rhGH | Etiology GHD | IGF-1 (ng/ml) initially | BMI (kg/m2) initially |

CO-GHD in history | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F | 41 | HCT, L, D, Es/Pg | 0.5 mg | CPGP | 68.6 | 30.9 | + |

| P2 | M | 25 | L,T | 0.5 mg | NFPM | 62.8 | 24.8 | + |

| P3 | M | 18 | T | 0.4 mg | CPH | 27.3 | 22.8 | + |

| P4 | F | 26 | HCT, L, Es/Pg | 0.6 mg | CPH | 40.1 | 29.0 | + |

| P5 | M | 19 | D, L, T, HCT | 0.3 mg | CPGP | 74.8 | 34.9 | + |

| P6 | F | 60 | HCT, L | 0.4 mg | ES | 15.11 | 24.3 | - |

| P7 | M | 20 | L, HCT, T | 0.3 mg | CPH | 91.8 | 28.1 | + |

| P8 | M | 23 | - | 0.3 mg | I | 138.8 | 25.9 | - |

| P9 | F | 38 | L, HCT, Es/Pg | 0.5 mg | NFPM | 47.07 | 24.9 | - |

| P10 | M | 18 | T | 0.2 mg | I | 120.2 | 20.4 | + |

| P11 | M | 28 | L, HCT, T, D | 0.3 mg | CPGP | 22.6 | 27.1 | + |

| P12 | M | 42 | L, T, D | 0.3 mg | CPGP | 63.0 | 54.1 | + |

| P13 | M | 36 | HCT, L, T | 0.5 mg | CPGP | 48.9 | 21.5 | + |

| P14 | M | 18 | L, HCT, D, T | 0.7 mg | CPGP | 54.4 | 24.4 | + |

| P15 | M | 25 | L, HCT, T | 0.5 mg | CPGP | 8.6 | 35.8 | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.