Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

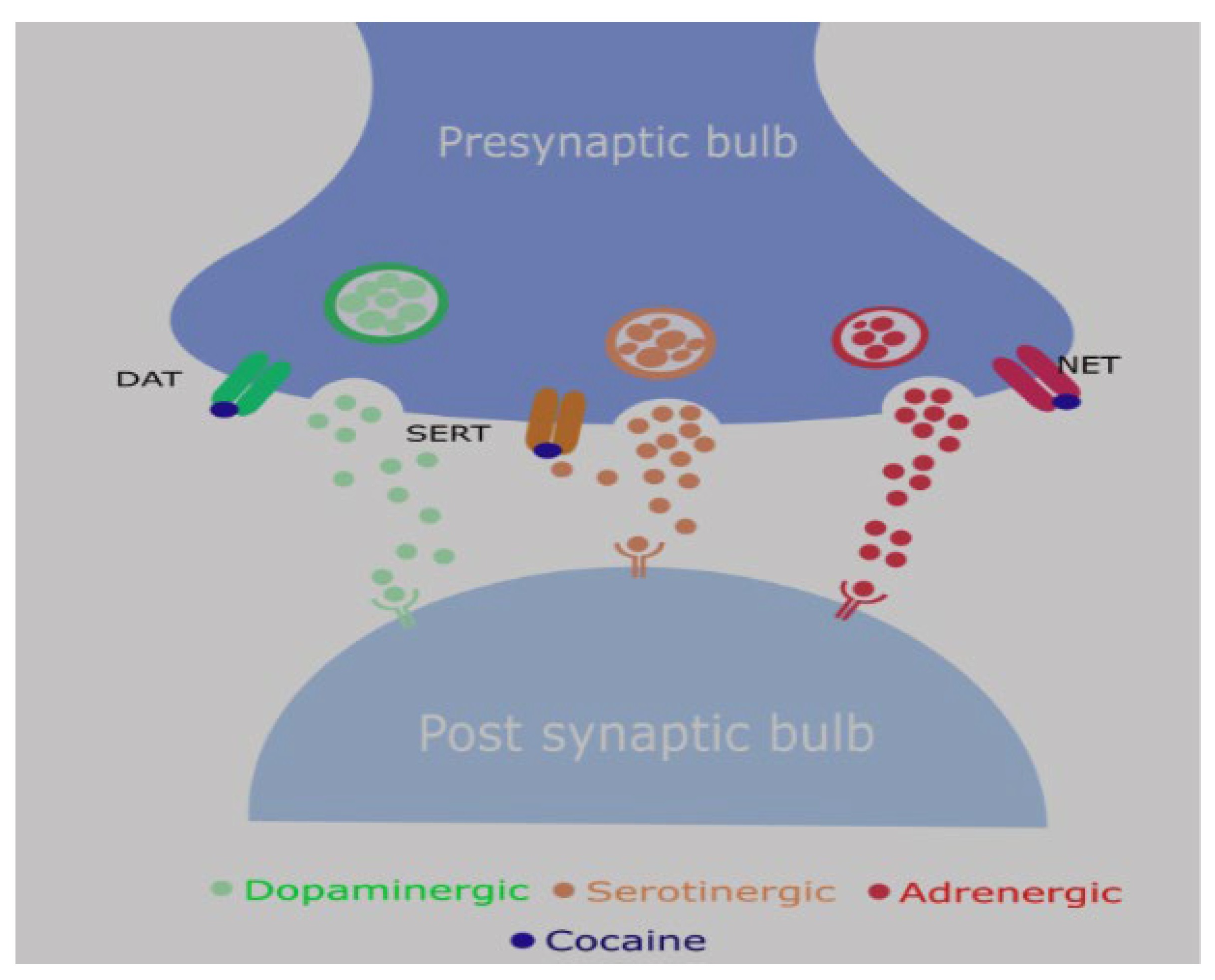

- Neurotransmitter reuptake inhibition: Cocaine blocks presynaptic reuptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin by inhibiting their transporters (DAT, NET, SERT) [1].

- Reward pathway: Increased dopamine in the mesolimbic system due to blockade of dopamine transporter → euphoric rush (addictive potential) followed by dysphoric crash

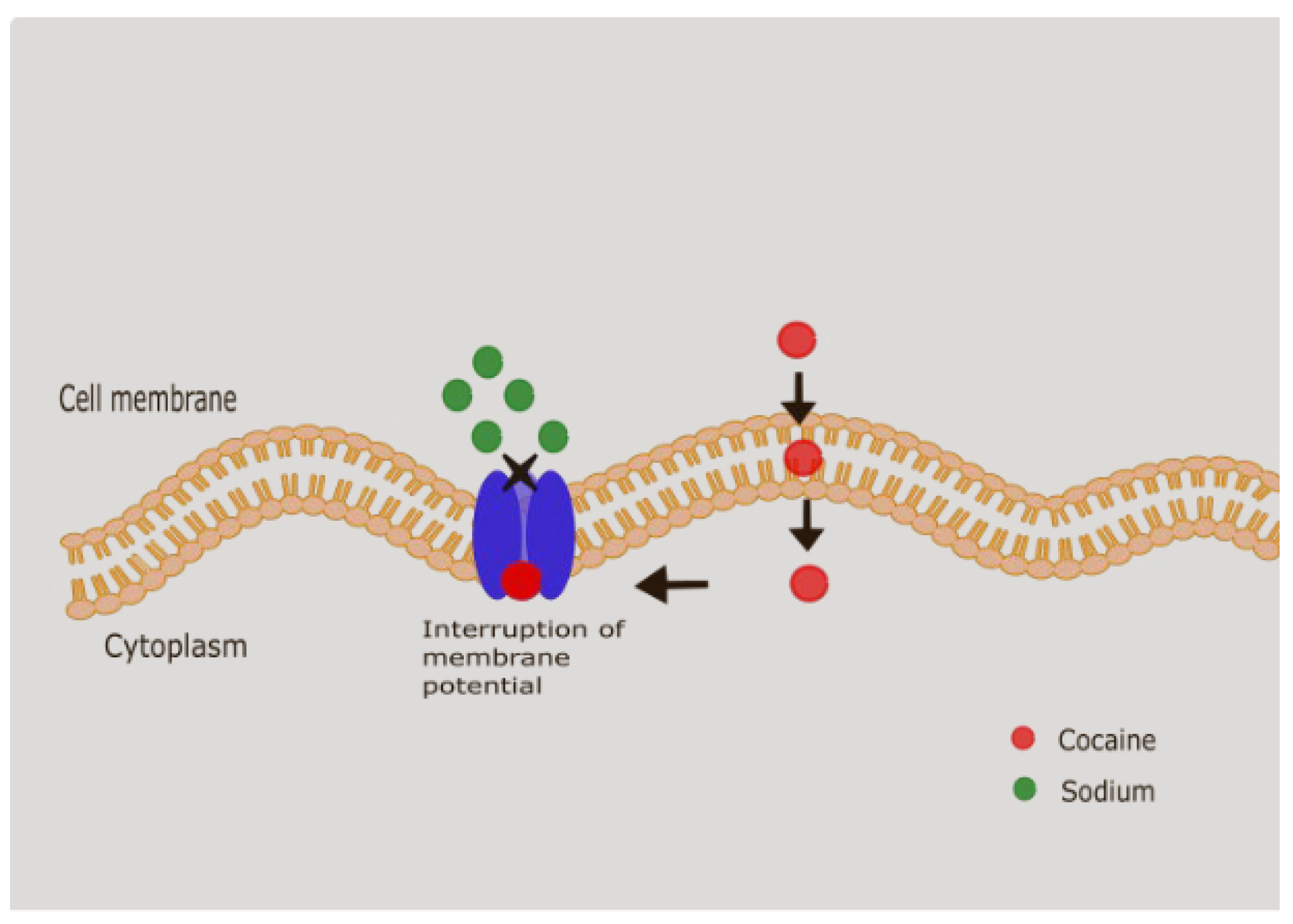

- Local anesthetic effect: Sodium channel blockade in excitable membranes → used historically in ophthalmology and ENT.

- Cocaine can also target NMDA, sigma and kappa opioid receptors. The clinical implications of these are still being explored.

- Thrombosis and Platelet Aggregation: It activates platelets by increasing the expression of platelet factor 4, thromboglobulin B, and P-selectin. It has been shown to induce endothelial dysfunction by increasing endothelin-1 expression with concurrent decrease in nitric oxide [3]. It also increases the levels of fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and decreasing the levels of protein C and antithrombin III. These changes in the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems create a pro-thrombotic state, which increases the risk of thrombosis [4,5]. It can also increase the sensitivity of platelets to other agonists, such as ADP and collagen [4].

- Oxidative Stress: Cocaine has been shown to increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in a variety of cell types, including hepatocytes and endothelial cells. This increase in oxidative stress can lead to cellular damage and death, and it may play a role in the direct cytotoxic effects of the drug.

- Hepatotoxic Metabolites: Cocaine is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes, and some of its metabolites, such as norcocaine and cocaethylene, are more hepatotoxic than the parent compound. These metabolites can cause direct injury to the hepatocytes, leading to a spectrum of liver injury, from mild hepatitis to acute liver failure.

- Intranasal insufflation (“snorting”)

- Common recreational route.

- Onset: 5–10 min; Duration: 30–60 min.

- 2.

- Smoking (crack cocaine)

- Rapid pulmonary absorption.

- Onset: seconds; Duration: 5–15 min.

- Intense “rush” but short-lived → high addictive potential.

- 3.

- Intravenous injection

- Immediate bioavailability, peak plasma concentration within seconds.

- High risk of overdose, infection, and vascular injury.

- 4.

- Oral ingestion

- Less common recreationally; sometimes seen in “body packers/mules.”

- Erratic absorption due to first-pass metabolism; slower onset.

- 5.

- Rectal (“plugging”) or vaginal use

- Reported in some cases.

- Leads to unpredictable absorption, sometimes severe toxicity.

-

Absorption:

- ○

- Inhalation/smoking (crack) → rapid absorption via pulmonary circulation.

- ○

- Intranasal insufflation → slower absorption, bioavailability ~30–60%.

- ○

- Intravenous injection → immediate systemic availability.

- ○

- Oral/rectal → erratic absorption due to first-pass metabolism. [6]

- Distribution: Highly lipophilic → rapidly crosses blood–brain barrier. Volume of distribution ~1–3 L/kg.

-

Metabolism:

- ○

- Primarily in liver via plasma and hepatic esterases.

- ○

- Major metabolites: benzoylecgonine (inactive, urinary marker), ecgonine methyl ester [6].

- ○

- With alcohol co-use → cocaethylene forms (longer half-life, more cardiotoxic).

-

Elimination:

- ○

- Plasma half-life: ~40 to 90 mins. [6]

- ○

- Metabolites excreted in urine; detectable for 2–3 days, longer in chronic users.

- CNS effects: Euphoria, increased alertness, hypervigilance, decreased fatigue, but also anxiety, agitation, and seizures at high doses. The intense vasoconstriction caused by cocaine can cause ischemic infarctions, intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage, movement disorders (crack dancing) and seizures (by lowering seizure potential). [7]

- Cardiovascular effects: Tachycardia, hypertension, coronary vasospasm, arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia/infarction.

- GI effects: Mesenteric vasoconstriction → ischemia, infarction, perforation,small bowel hematomas, intussusception, hemorrhage, acute pancreatitis.

- Other systemic effects: Hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis, renal injury.

- Ischemic/Vascular: Mesenteric ischemia/infarction, colonic ischemia, ischemic/ hemorrhagic colitis, Vascular thrombosis

- Ulcerative/Perforative: Peptic ulcer disease, Gastric, duodenal, small and large bowel perforations

- Inflammatory/Fibrotic: Enteritis, enterocolitis, strictures, retroperitoneal fibrosis

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic

- Splenic

- Other: GAVE, IBD mimic

- ▪

- Ischemic/ Vascular

2. Ulcerative and Perforative Complications

3. Fibrotic and Obstructive Conditions

| Study | Findings |

| Silva et al [35] | esophageal stricture following an episode of gastric ulcer |

| Hurtado et al [33] | combined pyloric stenosis with prepyloric and duodenal perforation. |

| Aldana et al [36] | Gastric outlet obstruction/ duodenal stenosis due to chronic cocaine abuse requiring roux-en-Y anastomosis. |

| Perysinakis et al [37] | chronic bowel ischemia manifesting as small bowel obstruction due to extensive intestinal wall fibrosis. |

| Ruiz-tovar et al [38] | sigmoid colon stenosis due to chronic ischemic colitis. |

4. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Complications

- Cocaine is N-demethylated to norcocaine (NCOC) in liver and kidney.

- NCOC undergoes further oxidation to N-OH-NCOC and NCOC-NO·.

-

These metabolites:

- ○

- Enter redox cycling, generating ROS → oxidative stress → cell death.

- ○

- Or form highly reactive ions that bind irreversibly to proteins → hepatocyte death.

Mitochondrial Involvement

- Mitochondria might be the major target of cocaine hepatotoxicity.

-

Cocaine can mediate mitochondrial cytotoxicity by the following mechanism

- ○

- Inhibiting mitochondrial respiration → ATP depletion → necrosis.

- ○

- ROS generation → oxidative stress.

- ○

- Activation of apoptosis (caspase-3 activation, cytochrome c release).

5. Splenic Complications

6. Other Complications

References

- Roque Bravo R, Faria AC, Brito-Da-costa AM, Carmo H, Mladěnka P, Dias da Silva D, et al. Cocaine: An Updated Overview on Chemistry, Detection, Biokinetics, and Pharmacotoxicological Aspects including Abuse Pattern. Vol. 14, Toxins. MDPI; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ali AA, Flint A, Elmasry M, Ghali M. Acute haemorrhagic ischaemic colitis secondary to cocaine use. BMJ Case Rep [Internet]. 2023 Sep 4;16(9):e255704. Available from: https://casereports.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bcr-2023-255704. [CrossRef]

- Dy IA, Wiernik PH. Cocaine-levamisole thrombotic vasculopathy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38(8):780–2. [CrossRef]

- Bhullar A, Nahmias J, Kong A, Swentek L, Chin T, Schellenberg M, et al. Cocaine use in trauma: the vices-paradox revisited. Surgery (United States). 2023 Oct 1;174(4):1056–62. [CrossRef]

- Bachi K, Mani V, Jeyachandran D, Fayad ZA, Goldstein RZ, Alia-Klein N. Vascular disease in cocaine addiction. Vol. 262, Atherosclerosis. Elsevier Ireland Ltd; 2017. p. 154–62. [CrossRef]

- Cone EJ. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cocaine [Internet]. Vol. 19, Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1995. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jat/article/19/6/459/774170. [CrossRef]

- Büttner A. Neuropathological alterations in cocaine abuse. Curr Med Chem [Internet]. 2012;19(33):5597–600. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22856656. [CrossRef]

- Wattoo MA, Osundeko O. Cocaine-induced intestinal ischemia. West J Med [Internet]. 1999 Jan;170(1):47–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9926736.

- Osorio J. Cocaine-Induced Mesenteric Ischaemia [Internet]. 2000. Available from: http://karger.com/dsu/article-pdf/17/6/648/2668335/000051980.pdf.

- Kaufman MJ, Siegel AJ, Mendelson JH, Rose SL, Kukes TJ, Sholar MB, et al. Cocaine administration induces human splenic constriction and altered hematologic parameters [Internet]. Vol. 85, J. Appl. Physiol. 1998. Available from: http://www.jap.org. [CrossRef]

- Ellis CN, McAlexander WW. Enterocolitis associated with cocaine use. Vol. 48, Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2005. p. 2313–6.

- Angel W, Angel J, Shankar S. Ischemic bowel: Uncommon imaging findings in a case of cocaine enteropathy. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(2):38–43. [CrossRef]

- Hoang MP, Lee EL, Anand A. Histologic spectrum of arterial and arteriolar lesions in acute and chronic cocaine-induced mesenteric ischemia: report of three cases and literature review. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998 Nov;22(11):1404–10.

- Edgecombe A, Milroy C. Sudden death from superior mesenteric artery thrombosis in a cocaine user. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2012 Mar;8(1):48–51. [CrossRef]

- Myers SI, Clagett GP, James Valentine R, Hansen ME, Anand A, Chervu A, et al. Chronic intestinal ischemia caused by intravenous cocaine use" Report of two and review of the literature cascs. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Elramah M, Einstein M, Mori N, Vakil N. High mortality of cocaine-related ischemic colitis: A hybrid cohort/case-control study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jun;75(6):1226–32. [CrossRef]

- Niazi M, Kondru A, Levy J, Bloom AA. Spectrum of Ischemic Colitis in Cocaine Users. [CrossRef]

- Endress C, Gray DGK, Wollschlaeger G. Bowel lschemia and Perforation After Cocaine Use [Internet]. 1992. Available from: www.ajronline.org.

- Deivasigamani S, Irrinki S, Shah J, Sakaray Y. Rare cause of acute abdomen-cocaine-induced small intestinal perforation with coexisting lower gastrointestinal bleed: An unusual presentation. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Feb 10;14(2). [CrossRef]

- Fishel R, Hamamoto G, Barbui A, Jijl V. Cocaine Colitis Is This a New Syndrome?

- Ullah W, Abdullah HMA, Rauf A, Saleem K. Acute oesophageal necrosis: A rare but potentially fatal association of cocaine use. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [CrossRef]

- Bathobakae L, Ozgur SS, Bashir R, Wilkinson T, Phuu P, Yuridullah R, et al. Cocaine Gut: A Rare Case of Cocaine-Induced Esophageal, Gastric, and Small Bowel Necrosis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2024 Jan 1;12. [CrossRef]

- Naidu PK, Frankel LR, Roorda S, Renda M, Mckenney MG. Cocaine Use and Incarceration: A Rare Cause of Bowel Ischemia, Perforation, and Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Cureus. 2022 Aug 29; [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vieira A, Camacho-Ramírez A, Díaz-Godoy A, Calvo-Durán A, Pérez-Alberca CM, de-la-Vega-Olías C, et al. Bowel ischaemia and cocaine consumption; case study and review of the literature. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. 2014 May;106(5):354–8.

- Saud Khan M, Khan Z, Khateeb F, Moustafa A, Taleb M, Yoon Y. Recurrent levamisole-induced agranulocytosis complicated by bowel ischemia in a cocaine user. American Journal of Case Reports. 2018 Jun 1;19:630–3.

- Chander B, Aslanian HR. Gastric perforations associated with the use of crack cocaine. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) [Internet]. 2010 Nov;6(11):733–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21437024.

- Lee HS, LaMaute HR, Pizzi WF, Picard DL, Luks FI. Acute gastroduodenal perforations associated with use of crack. Ann Surg [Internet]. 1990 Jan;211(1):15–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2403771. [CrossRef]

- Sharma R, Organ CH, Hirvela ER, Henderson VJ. Clinical Observation of the Temporal Association between Crack Cocaine and Duodenal Ulcer Perforation. [CrossRef]

- Mao RMD, Roberts GJ, Hranjec T, Hennessy SA. Incidence of Cocaine Use in Perforated Peptic Ulcer Disease at a Large Safety-Net Hospital. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Oct;227(4):e136–7. [CrossRef]

- Uzzaman MM, Alam A, Nair MS, Meleagros L. Gastric Perforation in a Cocaine User. Vol. 6, Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2010.

- Gaduputi V, Tariq H, Ihimoyan A. Atypical Gastric Ulcer in an Elderly Cocaine User. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:1–3. [CrossRef]

- Schuster KM, Feuer WJ, Barquist ES. Outcomes of cocaine-induced gastric perforations repaired with an omental patch. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2007 Nov;11(11):1560–3. [CrossRef]

- Berdugo Hurtado F, Barrientos Delgado A, López Peña C. A large perforated gastric ulcer due to cocaine use. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2022 Jul 1;114(7):431–2.

- Mabrouk MY, Guellil A, Haitam S, Deflaoui T, Jabi R, Bouziane M. Peritonitis on sigmoidal perforation in a cocaine user: A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2024 Feb 1;115. [CrossRef]

- Appel-Da-Silva MC, D’Incao RB, Antonello VS, Cambruzzi E. Gastrointestinal complications and esophageal stenosis after crack cocaine abuse. Vol. 45, Endoscopy. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Tolaque-Aldana YP, Hernández-Rodarte V, Jáquez-Quintana JO. Crack cocaine abuse as an undescribed cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2022;114(9):550–1. [CrossRef]

- Perysinakis I, Saridakis G, Giannarakis M, Kritikou G, de Bree E. Cocaine-Induced Chronic Bowel Ischemia Manifesting As Small Bowel Obstruction. Cureus. 2024 Apr 25; [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Candela F, Oliver I, Calpena R. Sigmoid colon stenosis: a long-term sequelae of cocaine-induced ischemic colitis. Am Surg. 2010 Sep;76(9):E178-9. [CrossRef]

- Goraya MHN, Malik A, Inayat F, Ishtiaq R, Zaman MA, Arslan HM, et al. Acute pancreatitis secondary to cocaine use: a case-based systematic literature review. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021 Aug 1;14(4):1269–77. [CrossRef]

- Valente MJ, Carvalho F, Bastos M d L, de Pinho PG, Carvalho M. Contribution of oxidative metabolism to cocaine-induced liver and kidney damage. Curr Med Chem [Internet]. 2012;19(33):5601–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22856659. [CrossRef]

- Carpano F, Giacani E, Moro D, Gurgoglione G, De Simone S. Heat shock protein (HSP) and its correlation to cocaine-related death: a systematic review. Clinica Terapeutica. 2024;175(4):10–5.

- Verma A, Bennett J, Örme AM, Polycarpou E, Rooney B. Cocaine addicted to cytoskeletal change and a fibrosis high. Vol. 76, Cytoskeleton. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2019. p. 177–85. [CrossRef]

- Tamargo JA, Sherman KE, Sékaly RP, Bordi R, Schlatzer D, Lai S, et al. Cocaethylene, simultaneous alcohol and cocaine use, and liver fibrosis in people living with and without HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Mar 1;232. [CrossRef]

- Cocaine-Induced Acute Hepatitis and Thrombotic Microangiopathy. JAMA [Internet]. 2005 Feb 16;293(7):793. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.293.7.797. [CrossRef]

- Patel KH, Thomas KC, Stacey SK. Episodic Cocaine Use as a Cause of Venous Thromboembolism and Acute Liver Injury. American Journal of Case Reports. 2023;24. [CrossRef]

- Novielli KD, Chambers C V. Splenic infarction after cocaine use. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 1991 Feb 1;114(3):251–2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1984755. [CrossRef]

- Homler HJ. Nontraumatic splenic hematoma related to cocaine abuse. West J Med [Internet]. 1995 Aug;163(2):160–2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7571571.

- Ballard DH, Smith JP, Samra NS. Atraumatic splenic rupture and ileal volvulus following cocaine abuse. Clin Imaging. 2015 Nov 1;39(6):1112–4. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro BN de F, Correia RS, Salata TM, Antunes FS, Marchiori E. Subcapsular splenic hematoma and spontaneous hemoperitoneum in a cocaine user. Radiol Bras [Internet]. 2017 Apr;50(2):136–7. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0100-39842017000200136&lng=en&tlng=en. [CrossRef]

- Lee Ramos J, Farr M, Shin SH, Ahmed N. Atraumatic splenic rupture in young adult following cocaine use. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019 Jan 1;65:168–70.

- Karthik N, Gnanapandithan K. Cocaine Use and Splenic Rupture: A Rare Yet Serious Association. Clin Pract. 2016 Aug 11;6(3):868. [CrossRef]

- Azar F, Brownson E, Dechert T. Cocaine-associated hemoperitoneum following atraumatic splenic rupture: A case report and literature review. Vol. 8, World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Khan AN, Casaubon JT, Paul Regan J, Monroe L. Cocaine-induced splenic rupture. J Surg Case Rep. 2017 Mar 1;2017(3).

- Kravchenko T, Chaudhry A, Khan Z. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding from gastric antral vascular ectasia following cocaine use: case presentation and review of literature. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2023 Aug 31;65(4):681–5. [CrossRef]

- Chivero ET, Ahmad R, Thangaraj A, Periyasamy P, Kumar B, Kroeger E, et al. Cocaine Induces Inflammatory Gut Milieu by Compromising the Mucosal Barrier Integrity and Altering the Gut Microbiota Colonization. Sci Rep. 2019 Dec 1;9(1). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).