1. Introduction

Orthopedic trauma typically involves volumetric muscle loss (VML), defined as the surgical or traumatic loss of muscle tissue (>20%) resulting in functional impairment [

1]. Skeletal muscles commonly sustain mild or moderate injury and have remarkable regenerative capabilities; however, in VML, the tissue architecture is disrupted, impairing regenerative capacity. The etiology of VML is the loss of muscle fibers and native elements such as satellite cells and extracellular matrix components (ECM), resulting in the permanent loss of contractile tissue. Consequently, due to the characteristics of VML, such as prolonged inflammation and persistent strength deficits, patients often experience disfigurement and/or chronic disability [

1,

2,

3]. Clinical options for reconstructing or repairing muscle tissue following VML are extremely limited. As a result, VML contributes to permanent disability in civilian and military patients [

4].

In a previous studies, fibrin-laminin hydrogels were developed for VML treatment [

5,

6,

7]. Implantation of LM-111 (450 μg/mL) enriched fibrin (FBN450) hydrogels supported myogenic protein expression, increased the ratio of contractile tissue to fibrotic tissue, increased the quantity of neuromuscular junctions, and resulted in a higher quantity of small to medium sized myofibers (500 – 2000 μm

2). Overall, the FBN450 hydrogel enhanced functional muscle regeneration, improving muscle force by ~60% compared to the untreated VML group at 28 days post-injury. Collectively, these results showed that an acellular therapy, such as the FBN450 hydrogels, can provide a promising therapeutic treatment for VML.

To improve regeneration and function following trauma, the synergistic application of both regenerative and rehabilitation strategies is being explored [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In a previous study, we optimized an electrical-stimulation eccentric-contraction training (EST) program by implementing the regimen 14 days post-VML injury for 4 weeks. Briefly, the training program consisted of altering the mechanical load on VML-injured muscles by modulating the stimulation frequency (50 Hz, 100 Hz, & 150 Hz) for a total of 20 eccentric contractions per bout. Our results show that the implementation of the electrical stimulation protocol at a high frequency (150 Hz) improves muscle mass (~39%) and muscle function (~34%) compared to a non-trained VML sham group [

15].

We hypothesized that the regenerative therapy (FBN450 hydrogel) would support myofiber hyperplasia, while the rehabilitation technique (EST) would concurrently drive hypertrophy of these regenerated fibers. This combinatorial approach was expected to yield superior muscle mass and strength. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the extent of functional repair and regeneration following the combined application of FBN450 and EST in a rodent VML model.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study is to investigate the efficacy of combining a regenerative therapy, FBN450 hydrogel, with a rehabilitation program, EST, for functional repair of VML in a rodent model. Although FBN450 [

5] and EST [

15] have previously demonstrated improved regeneration and function when used individually, the combined application of these therapies in this study unexpectedly hindered muscle recovery.

The lack of synergistic improvement in the hydrogel plus EST group, despite the well-documented benefits of EST in untreated [

15] and biosponge-treated [

8] VML models, suggests a fundamental breakdown in the regenerative rehabilitation paradigm. In previous studies, we have observed a lack of integration between the hydrogel and the surrounding muscle tissue [

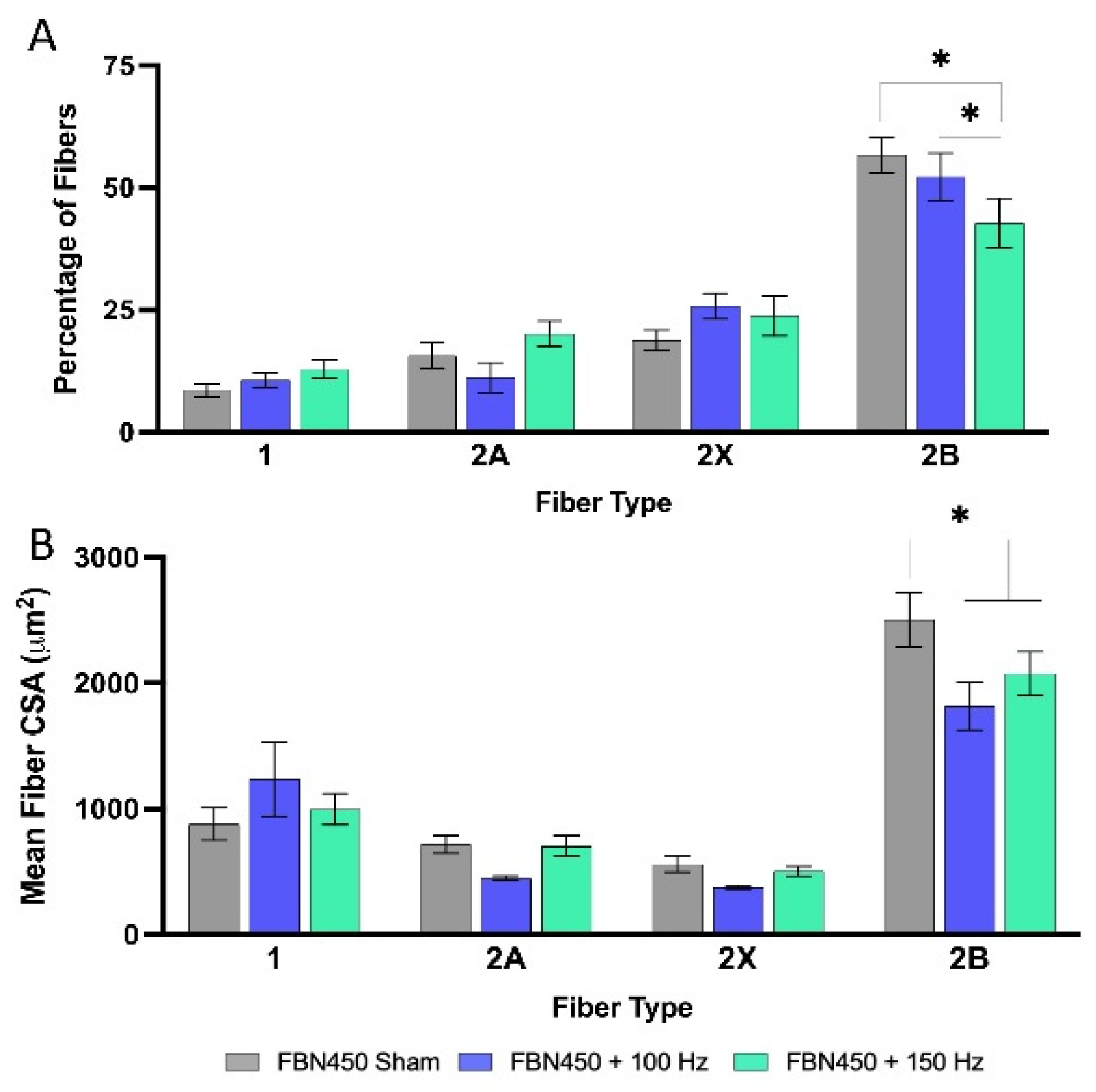

5]. Therefore, by remaining physically separated from the surrounding musculature, the hydrogel likely created a structural discontinuity that might have prevented the seamless transfer of mechanical cues. This is most clearly evidenced by the significant decrease in the percentage of Type 2B myofibers and in cross-sectional area (CSA). Type 2B fibers are highly glycolytic and the most sensitive to mechanical unloading [

24]. Therefore, their atrophy following the combined application of hydrogel and EST suggests that the hydrogel shielded the surrounding musculature from mechanical stress. Rather than the muscle experiencing the mechanical loading of eccentric exercise, the hydrogel may have absorbed or dampened these forces, effectively keeping the surrounding musculature in a state of functional disuse.

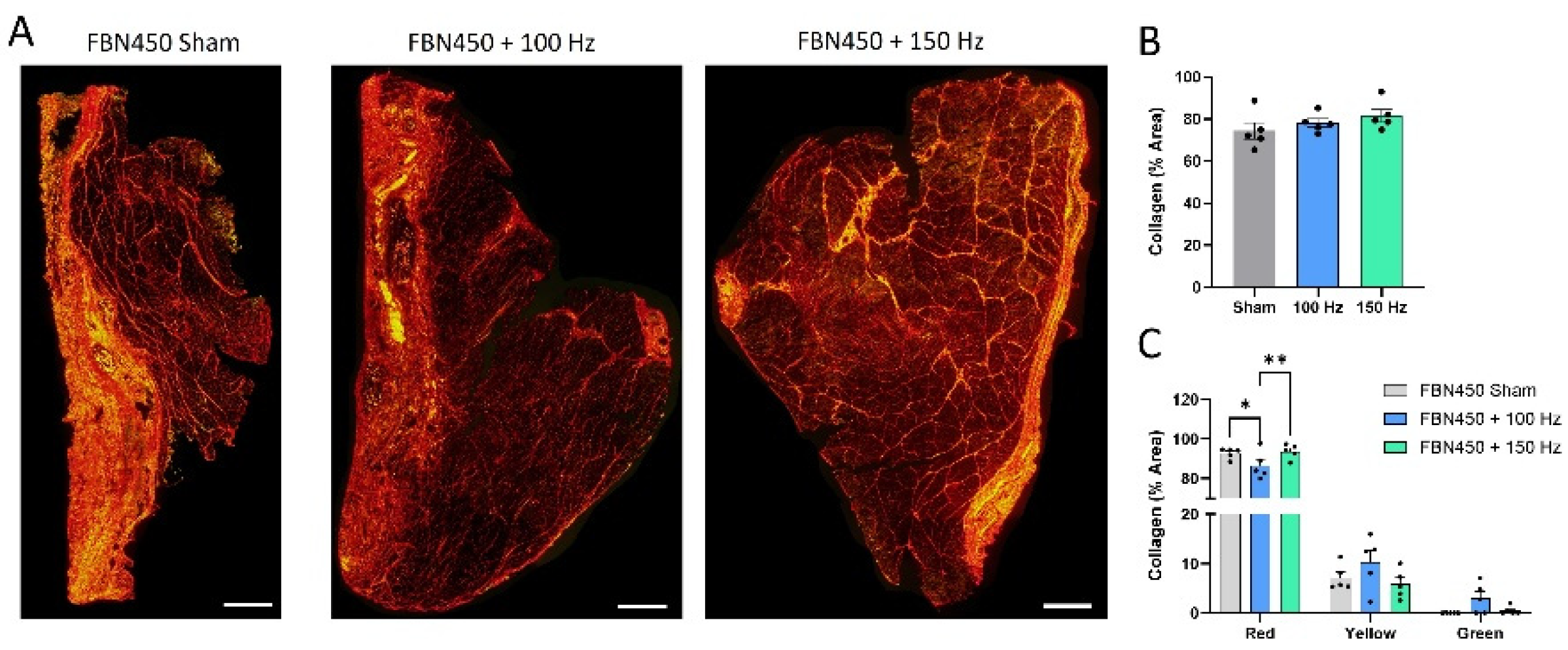

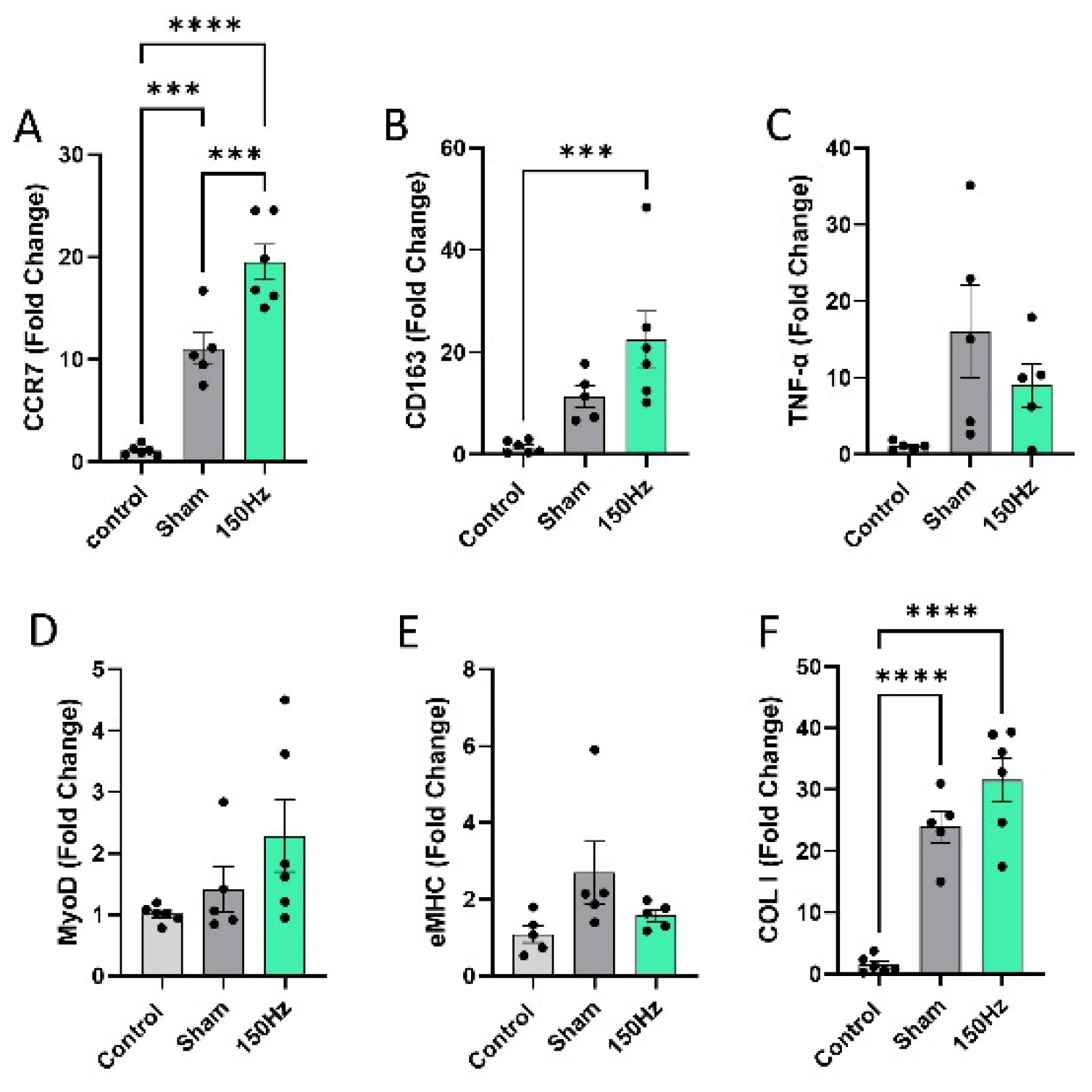

This mechanical shielding appears to have fundamentally altered the cellular response to rehabilitation. While hydrogel and EST can separately and individually drive myogenesis [

5,

15], their combined application led to a significant elevation in Collagen 1 gene expression without increased myogenic gene expression. Interestingly, while Collagen 1 gene expression was upregulated, total collagen protein levels remained similar across groups. This suggests a state of high-turnover remodeling where fibrotic signaling is accelerated, but potentially coupled with an equal rate of degradation, resulting in a disorganized extracellular matrix rather than functional tissue bridging.

The immunological profile of the hydrogel + EST group further explains this regenerative failure. The simultaneous elevation of M1-like (i.e., CCR7) and M2-like (i.e., CD163) macrophage markers suggests both a heightened and stalled inflammatory response. In a healthy healing trajectory, a clear transition from a pro-inflammatory M1 phase to a pro-regenerative M2 phase is required [

25,

26]. The persistent presence of both markers indicates a chronic foreign-body response, likely exacerbated by the hydrogel's mechanical motion during EST. We speculate that interfacial micromotion between the non-integrated hydrogel and the host tissue led to recurrent micro-trauma, which further drove pro-inflammatory signaling. This persistent inflammatory signaling is known to be antagonistic to myogenesis and can actively drive myofiber atrophy.

Ultimately, these results reveal a selective synergy between biomaterials and eccentric exercise. While the biosponge scaffolds used in previous studies likely allowed for better load-sharing and cellular infiltration [

8], the FBN450 hydrogel lacked the mechanical and structural features necessary for a synergistic effect with EST. Our findings demonstrate that synergy is not an inherent or guaranteed property of combining a scaffold with exercise. Instead, it is an emergent outcome dependent on the biomaterial’s mechanical and physical properties with the rehabilitative stimulus. If the biomaterial fails to integrate or share the mechanical load, as seen with the FBN450 hydrogel, the relationship between the scaffold and exercise can become antagonistic, leading to activation of inflammatory and fibrotic pathways. This highlights a critical need to engineer biomaterials that are specifically tuned to synchronize with rehabilitation. In fact, many studies have successfully combined biomaterials with various rehabilitation approaches in both humans and animal models [

13].

Furthermore, we speculate that the timing of the intervention likely turned the eccentric training regimen into a secondary insult. At 14 days post-injury, the hydrogel was only partially present at the defect site [

5]. We posit that the intense EST program may have accelerated the remodeling and degradation of the biomaterial before functional tissue bridging could occur. Consequently, the defect site became a void, leaving the injured muscle vulnerable to an intense training regimen that aggravated an already traumatic and chronic injury. In contrast, the FBN450 sham group, undisturbed by premature mechanical loading via EST, had ample time to elicit its regenerative capabilities, ultimately resulting in improved function. These findings highlight the necessity of a synchronized approach to recovery, where the intensity and timing of rehabilitation are calibrated to the structural integrity and biological stage of the implanted scaffold.

The current study is not without limitations, particularly regarding the intervention's fixed temporal window. While we hypothesized that the 14-day post-injury time point would represent a viable therapeutic window, the lack of real-time monitoring of the hydrogel’s structural integrity remains a constraint. Future research should use non-invasive imaging modalities (such as ultrasound) to track the hydrogel's degradation kinetics and host-tissue integration longitudinally [

27]. This would allow for a more objective determination of when the scaffold has successfully transitioned from a passive filler to an integrated, load-bearing conduit capable of withstanding the mechanical stresses of EST.

Building upon the findings of this study, several future directions are warranted to optimize the selective synergy between the FBN450 hydrogel and EST. A critical next step is to investigate whether the electrical stimulation protocol should be delayed, perhaps beginning at 21 days post-injury rather than 14 days. This extended undisturbed period might provide the regenerative therapy ample opportunity to fully integrate with the remaining musculature and establish a robust cellular niche before being subjected to mechanical strain due to EST. By allowing the hydrogel to elicit its full regenerative capacity and stabilize the defect site, a later introduction of EST may yield the functional improvements that were absent in the current study.

Conversely, while an earlier introduction of the training protocol could, in theory, provide more exercise sessions and lead to greater strength gains, previous studies suggest that this approach should be handled with caution [

28,

29]. Starting EST too soon after injury may inadvertently accelerate remodeling and premature hydrogel degradation, thereby creating a void at the defect site during a critical phase of myogenesis. This highlights a complex trade-off in regenerative rehabilitation, where the muscle requires early mechanical stimulus to prevent atrophy, but the biomaterial requires stability to facilitate repair. Future studies should therefore focus on identifying the goldilocks zone, an optimal time window in which the mechanical properties of the scaffold are sufficient to support load and the biological state of the muscle is primed to receive a hypertrophic stimulus provided by exercise.

Collectively, our findings reveal that synergy in regenerative rehabilitation is a conditional phenomenon, dependent on a match between the biomaterial’s properties and the intensity and timing of the rehabilitative stimulus. Successful recovery requires a synchronized approach to activate myogenesis rather than fibrotic and inflammatory cascades.

Figure 1.

Schematic representaction of the experimental design.

Figure 1.

Schematic representaction of the experimental design.

Figure 2.

(A) Muscle sections were stained with H&E at 42-days post-injury. The defect region is shown in the magnified images. (B) The muscle mass of the VML injured TA muscles was measured on 42-days post-injury (n=5 – 6 muscles/group). No significant differences were observed between the different groups. Data Analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA.

Figure 2.

(A) Muscle sections were stained with H&E at 42-days post-injury. The defect region is shown in the magnified images. (B) The muscle mass of the VML injured TA muscles was measured on 42-days post-injury (n=5 – 6 muscles/group). No significant differences were observed between the different groups. Data Analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA.

Figure 3.

Eccentric torque increases with each bout. (A) The Δ eccentric torque between bout 8 and bout 1 is reported, showing no differences between the 100 Hz and 150 Hz program when a hydrogel is introduced. The blue and green dotted lines represent the Δ eccentric torque for untreated VML injured muscles following EST training for 4 weeks. Data analysis was performed using an impaired t-test. (B) Average eccentric torque reported at each bout. Data analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA. (C) Peak isometric torque production was measured, and raw data was collected and normalized to body weight. The FBN450 Sham group resulted in the highest recovery in torque production compared to the FBN450 + 100 Hz and FBN450 + 150 Hz. Data analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA. Significance between FBN450 Sham group and FBN450 + 150 Hz is indicated by * (p<0.05). The symbol (#) indicates difference from all other groups.

Figure 3.

Eccentric torque increases with each bout. (A) The Δ eccentric torque between bout 8 and bout 1 is reported, showing no differences between the 100 Hz and 150 Hz program when a hydrogel is introduced. The blue and green dotted lines represent the Δ eccentric torque for untreated VML injured muscles following EST training for 4 weeks. Data analysis was performed using an impaired t-test. (B) Average eccentric torque reported at each bout. Data analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA. (C) Peak isometric torque production was measured, and raw data was collected and normalized to body weight. The FBN450 Sham group resulted in the highest recovery in torque production compared to the FBN450 + 100 Hz and FBN450 + 150 Hz. Data analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA. Significance between FBN450 Sham group and FBN450 + 150 Hz is indicated by * (p<0.05). The symbol (#) indicates difference from all other groups.

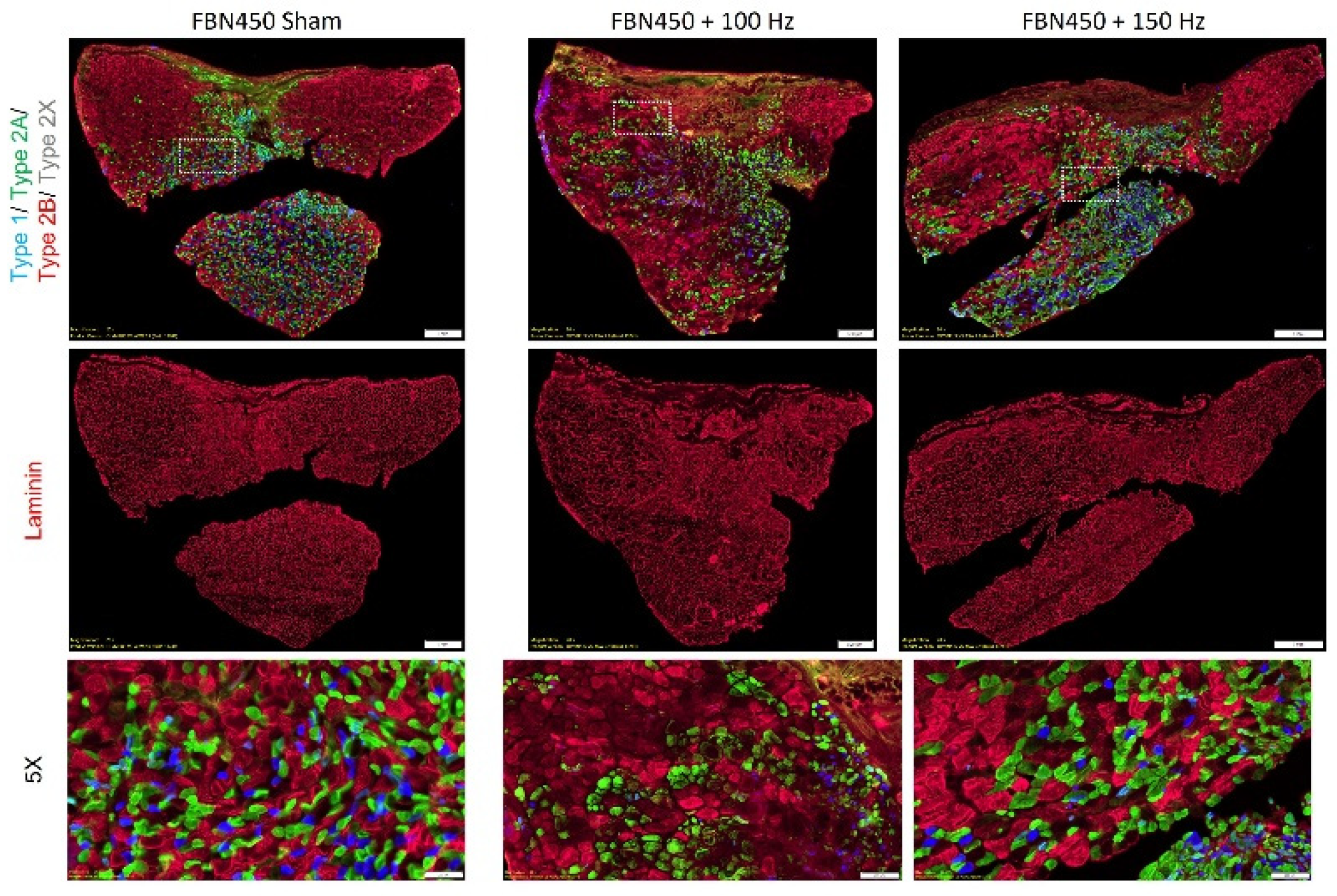

Figure 4.

Muscle sections were stained for various fiber types and laminin (n = 5 – 6 muscles/group) at day 42 post-injury.

Figure 4.

Muscle sections were stained for various fiber types and laminin (n = 5 – 6 muscles/group) at day 42 post-injury.

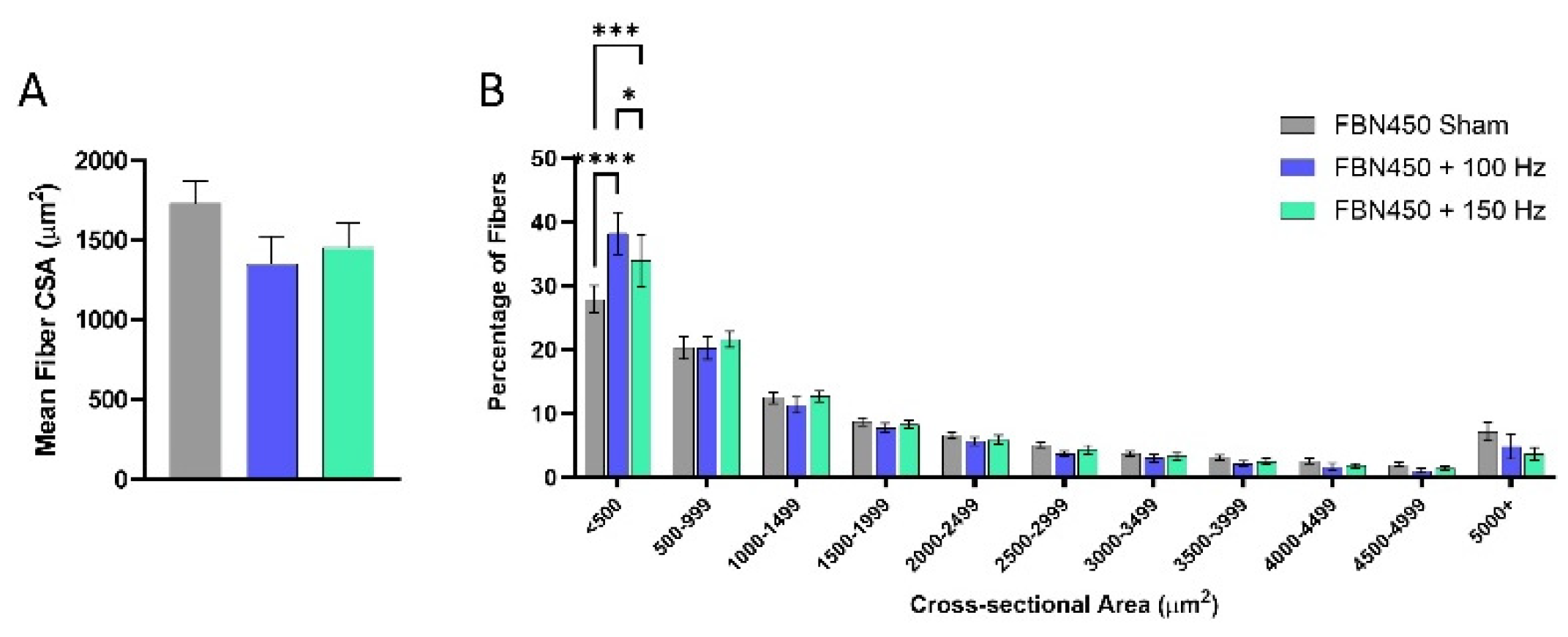

Figure 5.

The mean fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) (A) and global fiber size distribution (B) were quantified using a custom designed image analysis MATLAB program. The CSA distribution analysis showed that myofibers in the size range <500 μm2 were increased in the FBN450 treated muscles following electrical stimulation training at 100 Hz and 150 Hz compared to the FBN450 Sham muscles. Data analysis for the mean fiber CSA was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA. Data analysis for the fiber size distribution was performed using a two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Figure 5.

The mean fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) (A) and global fiber size distribution (B) were quantified using a custom designed image analysis MATLAB program. The CSA distribution analysis showed that myofibers in the size range <500 μm2 were increased in the FBN450 treated muscles following electrical stimulation training at 100 Hz and 150 Hz compared to the FBN450 Sham muscles. Data analysis for the mean fiber CSA was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA. Data analysis for the fiber size distribution was performed using a two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Figure 6.

The percentage and mean fiber CSA of 2B fibers increased in the FBN450 Sham group. (A) The percentage of fiber type specific fibers in each treatment group and the (B) fiber type specific mean fiber CSA was determined using a custom-designed image analysis MATLAB program. Data analysis was performed using a two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Figure 6.

The percentage and mean fiber CSA of 2B fibers increased in the FBN450 Sham group. (A) The percentage of fiber type specific fibers in each treatment group and the (B) fiber type specific mean fiber CSA was determined using a custom-designed image analysis MATLAB program. Data analysis was performed using a two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

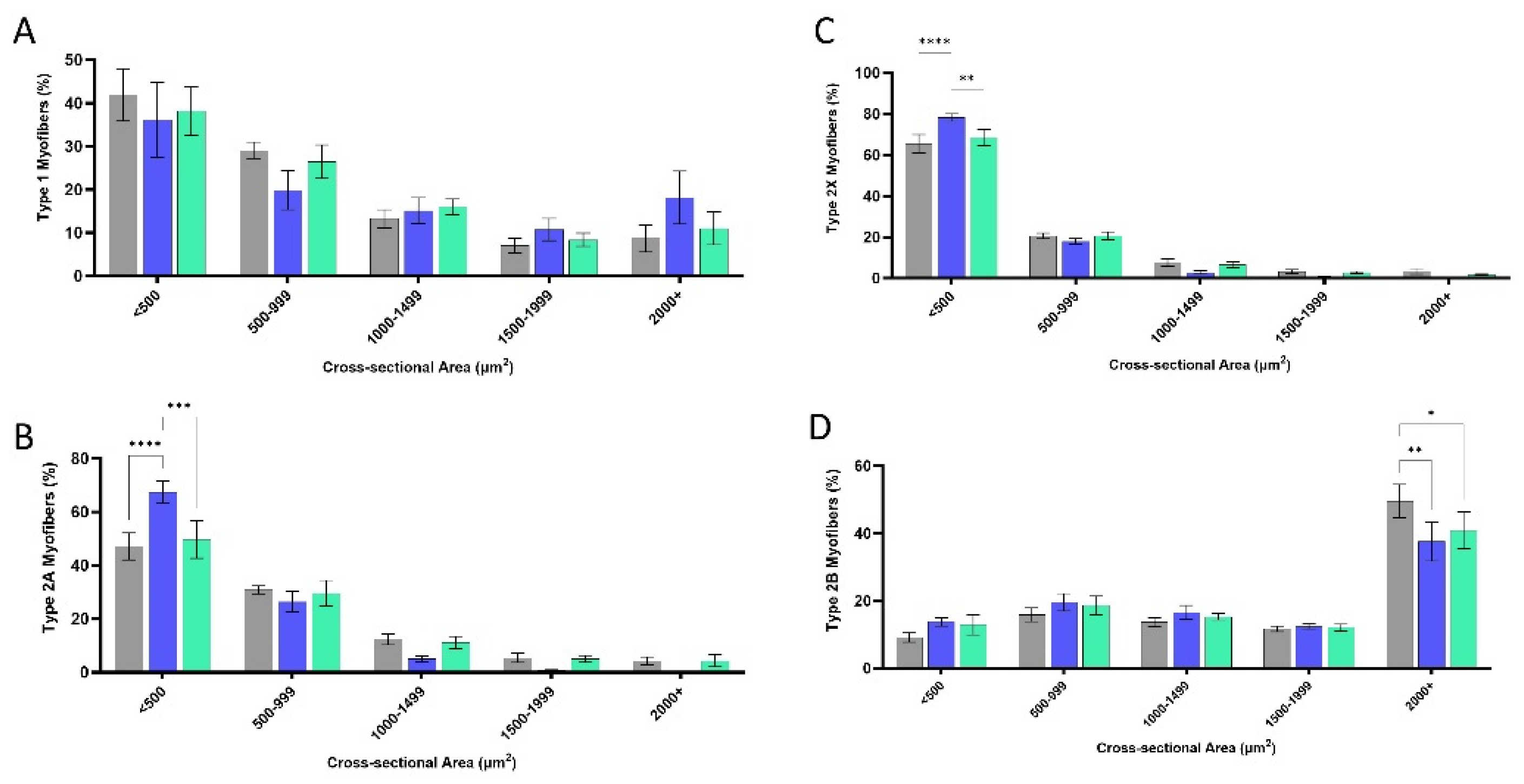

Figure 7.

Fiber size distributions for (A) type 1, (B) type 2A, (C) type 2B, and (D) type 2X were quantified using MyoQuant MATLAB program. Data analysis was performed using a two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Figure 7.

Fiber size distributions for (A) type 1, (B) type 2A, (C) type 2B, and (D) type 2X were quantified using MyoQuant MATLAB program. Data analysis was performed using a two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Figure 8.

Muscle cross-sections were stained with (A) Picrosirius Red (PSR) and imaged using polarized microscopy. (B) Total collagen area fraction was determined using thresholding by a custom MATLAB program. (C) Total area fraction of collagen separated into red, yellow, and green regions are quantified.

Figure 8.

Muscle cross-sections were stained with (A) Picrosirius Red (PSR) and imaged using polarized microscopy. (B) Total collagen area fraction was determined using thresholding by a custom MATLAB program. (C) Total area fraction of collagen separated into red, yellow, and green regions are quantified.

Figure 9.

Gene expression analysis of (A) proinflammatory marker CCR7, (B) anti-inflammatory marker CD163, (C) inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, (D) myoblast marker MyoD, (E) embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC), and (F) collagen type 1 (COL1) was performed 6 weeks post-injury. Data analysis was performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Figure 9.

Gene expression analysis of (A) proinflammatory marker CCR7, (B) anti-inflammatory marker CD163, (C) inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, (D) myoblast marker MyoD, (E) embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC), and (F) collagen type 1 (COL1) was performed 6 weeks post-injury. Data analysis was performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significance between groups is indicated by * (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequence for primers used for qRT-PCR.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequence for primers used for qRT-PCR.

| Gene |

Forward sequence (5’-3’) |

Reverse sequence (3’-5’) |

Amplicon length (bp) |

| 18s |

GGCCCGAAGCGTTTACTT |

ACCTCTAGCGGCGCAATAC |

173 |

| CCR7 |

GCTCTCCTGGTCATTTTCCA |

AAGCACACCGACTCATACAGG |

107 |

| CD163 |

TCATTTCGAAGAAGCCCAAG |

CTCCGTGTTTCACTTCCACA |

101 |

| TNF-α |

ACTCGAGTGACAAGCCCGTA |

CCTTGTCCCTTGAAGAGAACC |

184 |

| MyoD |

CGTGGCAGTGAGCACTACAG |

TGTAGTAGGCGGCGTCGTA |

133 |

| eMHC |

TGGAGGACCAAATATGAGACG |

CACCATCAAGTCCTCCACCT |

180 |

| COL1 |

CTGGTGAACGTGGTGCAG |

GACCAATGGGACCAGTCAGA |

123 |