Introduction

With the expanding armamentarium of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis (MS), selecting the most appropriate therapy for an individual patient has become increasingly complex and depends on multiple clinical, radiologic, and patient-specific factors. Once the decision to initiate a DMT is made, clinicians and patients must reach a shared agreement on one of two overarching therapeutic strategies: induction or escalation. Early initiation of high-efficacy therapies (HET), the induction approach, is associated with superior disease control and greater long-term disability reduction; however, it necessitates reliable treatment adherence, structured safety monitoring, and access to specialized care. In contrast, initiating treatment with lower-efficacy therapies (LET) entails fewer monitoring requirements and lower immediate risks but is associated with inferior disease control over time. Although contemporary guidelines increasingly favor early use of HET, recent studies indicate that real-world prescribing patterns particularly in rural and resource-constrained settings often diverge substantially from these recommendations.[

1,

2]

In a cohort involving 12,338 people with MS from Alberta, DMT exposure over two years was lower in rural than urban residents (27.4% vs 32.3%), with reduced neurologist contact (63.9% vs 67.7%) and tertiary MS clinic visits (51.7% vs 59.2%), alongside higher emergency department use (62.4% vs 46.3%) and hospitalizations (23.0% vs 20.4%).[

3] In another cohort (n=4,593), rural residence was associated with lower odds of receiving any DMT (OR:0.83; 95%CI:0.69–0.99), of which 39% was mediated by socioeconomic status; however, the reduction in induction/HET use was greater (OR:0.74; 95%CI:0.57–0.95) and minimally explained by socioeconomic factors (<1%).[

4] Time to treatment initiation also did not differ significantly by geography. In Newfoundland and Labrador (n=298), high-efficacy DMT use was 20.9% in semi-urban, 8.3% in urban, and 3.8% in rural patients, while moderate-efficacy DMT use was highest in rural patients(58.5%).[

5]

The data indicate that socioeconomic deprivation explains only a modest proportion of the observed disparity in HET adoption, implicating system-level constraints as the dominant drivers. These constraints likely include limited access to MS specialists, barriers to travel for longitudinal care, inadequate infusion infrastructure, and difficulties in implementing standardized safety-monitoring protocols. Notably, delays in treatment initiation do not consistently differ by geography, suggesting that the primary distortion lies not in whether therapy is initiated, but in the selection of therapy itself. This misalignment underscores the need to formally model the decision process using quantitative frameworks and to develop innovative, system-level interventions that maximize therapeutic benefit under real-world constraints.

The Game Theory Perspective

This clinical dilemma can be effectively modeled using “game theory”, the mathematical study of strategic interactions in which an individual’s outcome depends not only on their own decisions but also on the decisions of others. The power of game theory has been demonstrated across a wide range of disciplines, from economics to evolutionary biology, and its influence is underscored by the awarding of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to fifteen game theorists.

DMT selection in resource-limited settings can be conceptualized as a complex Bayesian decision-making between clinicians and patients. Clinicians form probabilistic beliefs regarding patient adherence, follow-up reliability, and system capacity, while patients face multidimensional costs related to drug access, travel, monitoring requirements, and potential adverse effects. Concurrently, health systems impose asymmetric penalties such as manpower crunches, infrastructural limitations and monitoring failures that disproportionately amplify the perceived downside of high-efficacy therapies under suboptimal conditions.

The Disease Modifying Therapy Dilemma and the Bayesian Nash Equilibrium

Consider a clinical scenario in which a neurologist must initiate a DMT and faces two strategic choices: Strategy A, early induction with a high-efficacy, high-cost therapy associated with a higher perceived risk, and Strategy B, an escalation approach using a lower-efficacy, lower-cost therapy with a lower perceived risk. Concurrently, the patient has two behavioral strategies: good compliance or poor compliance. In this context, compliance encompasses sustained medication use despite pre-existing beliefs and financial burden, avoidance of missed doses, and adherence to mandated safety and adverse-event monitoring.

The resulting payoffs differ. For the clinician, utility derives from effective disease control, patient satisfaction, and professional safety. For the patient, utility reflects clinical benefit, quality of life, treatment convenience, and financial cost. A set of strategies constitutes a Nash equilibrium when each player’s chosen strategy is optimal given the strategy of the other, such that no unilateral deviation can improve expected payoff. In settings characterized by barriers to compliance including limited access to specialized centers, inadequate monitoring infrastructure, financial constraints, and prevailing sociocultural beliefs the probability of poor compliance is substantially elevated. Under these conditions, early induction exposes clinicians to disproportionately large penalties in the event of compliance failure, whereas escalation strategies incur smaller, delayed, or less visible penalties. Consequently, escalation emerges as the Nash equilibrium.[

6] Neither the doctor nor the patient can safely switch to the aggressive strategy alone without risking a “negative payoff” as can be seen in a table of possible outcomes (

Table 1).

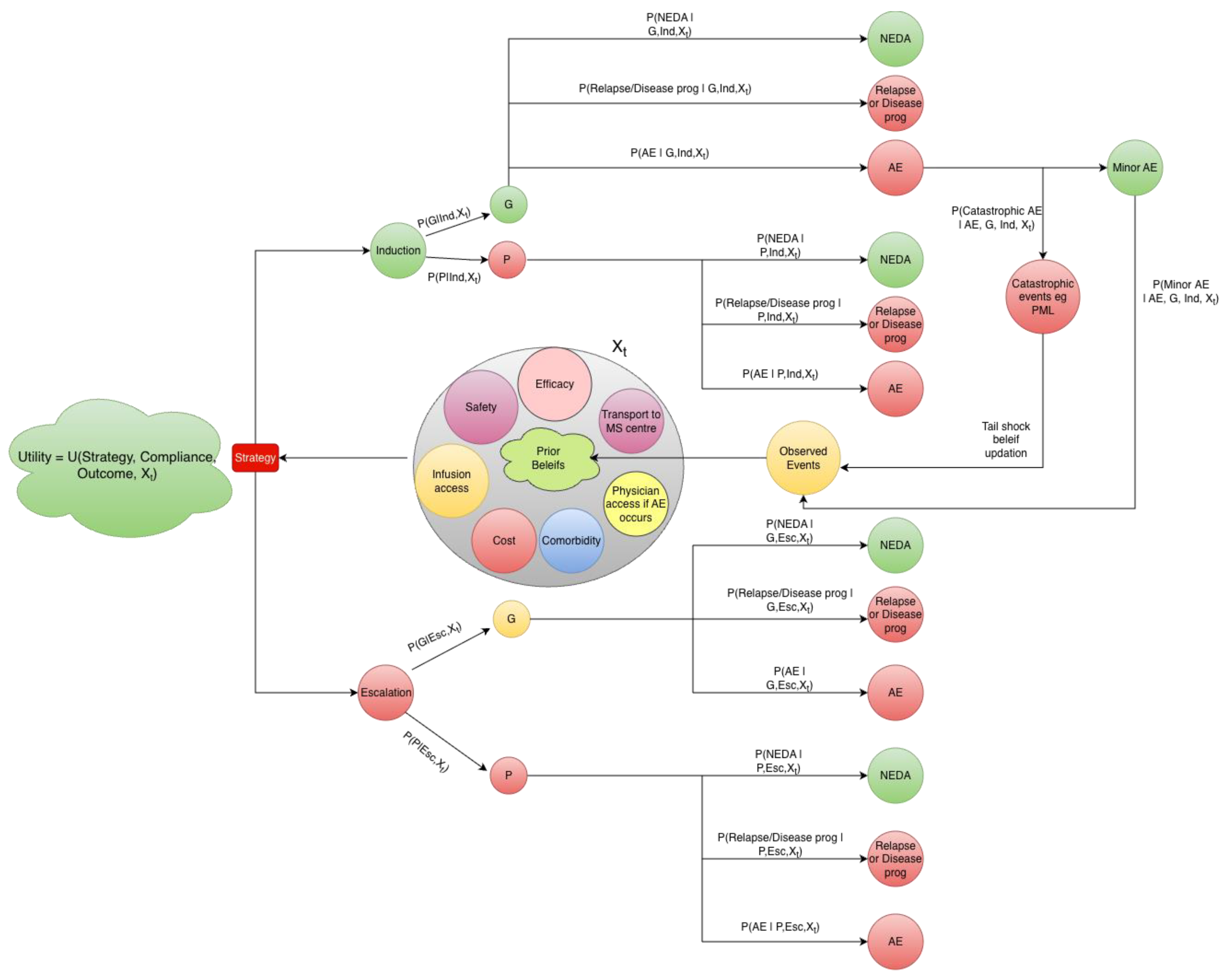

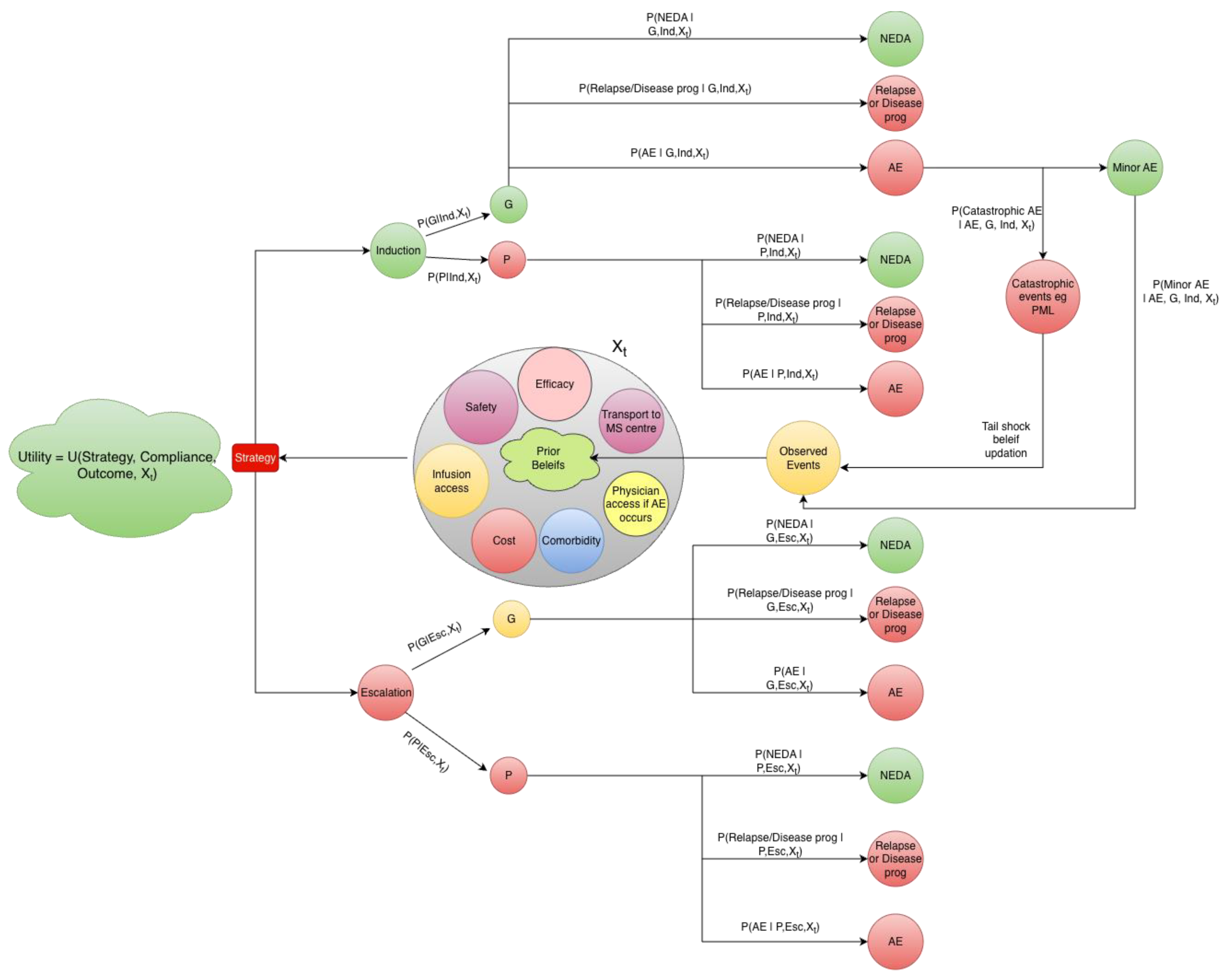

Markov Model and Tail Shocks

Clinical practice can be conceptualized as a sequence of interdependent decisions evolving over time, a structure well described by a Markov framework in which future practice patterns depend on the current state and recently observed events (

Figure 1). Within this framework, a hospital or clinic occupies one of two dominant practice states: an evidence-aligned state, characterized by readiness to initiate early HET, and a conservative escalation state, in which lower-efficacy therapies are preferentially selected. Trust in high-efficacy strategies accumulates gradually through repeated success supported by education, incentives, infrastructure, manpower, and favorable treatment experiences. In contrast, a single rare but severe “tail shock,” such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, can precipitate an abrupt transition toward conservative practice and, in some settings, may even provoke hostility or violence directed at clinicians. Once entered, the conservative state tends to function as a quasi-absorbing state, as conservative care seldom generates conspicuous acute failures, whereas the long-term harms of undertreatment remain delayed and largely invisible.

How do We Move this Equilibrium?

Altering the structure of the utility function, particularly by redistributing or attenuating penalties associated with HET can shift decision equilibria towards more favorable outcomes in resource-limited healthcare settings. Three solution pathways emerge from this framework. First, risk transfer: institutions can absorb rare but severe “tail risks” through legal protection, indemnification, and insurance mechanisms for guideline-concordant care. By externalizing catastrophic penalties, the personal expected loss faced by clinicians is reduced, enabling selection of Strategy A. Second, constraint reduction: targeted improvements in structural conditions such as transport assistance, digital connectivity, community health worker engagement, and artificial intelligence enabled symptom monitoring reduce the probability of poor adherence and monitoring failure, thereby increasing the expected utility of HET. Third, belief correction: systematic dissemination of high-quality real-world evidence from resource-limited settings demonstrating substantial effect sizes and acceptable safety margins can recalibrate perceived risk and promote adoption of evidence-aligned strategies. Encouragingly, elements of belief correction are already emerging in practice.[

7]

As illustrated in Figure-1, these interventions can be formally evaluated by parameterizing the proposed Markov decision framework with locally observed data. Health systems can assign context-specific probabilities for example, adherence rates, monitoring feasibility, relapse risk, and catastrophic adverse event rates and simulate repeated decision cycles under alternative utility configurations. By iteratively adjusting parameters representing risk transfer, constraint reduction, or belief updating, the model allows direct observation of how equilibrium behavior shifts in a given setting, identifying which interventions produce the largest gains in expected clinical utility. In this way, each institution can explore “what-if” scenarios tailored to its own infrastructure, workforce, and patient population, rather than relying on externally derived assumptions.

Broadly, this approach reframes DMT utilization as a dynamic, game-theoretic process in which clinicians and systems respond rationally to asymmetric information, uncertainty, and nonlinear penalties. Future work should explicitly model risk constraints as tunable parameters, link sequential clinical decisions to long-term outcomes using Bayesian Markov and game-theoretic frameworks, and quantify which probability shifts most effectively move systems away from conservative, quasi-absorbing equilibria. A promising extension is adaptive equilibrium mapping, in which simulated outcomes are periodically re-calibrated using incoming real-world data, allowing the model itself to learn which policy levers:legal, infrastructural, or informational, are most effective in a specific environment. Understanding DMT utilization, therefore, requires not only clinical evidence, but mathematical simulations that explicitly capture uncertainty, strategic behavior, and structural constraints, and that can be locally used to guide context-appropriate policy and practice.

References

- Filippi M, Amato MP, Centonze D, Gallo P, Gasperini C, Inglese M, Patti F, Pozzilli C, Preziosa P, Trojano M. The use of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: Recommendations from an expert Delphi consensus. J Neurol. 2025 Aug 10;272(9):565. PMID: 40783885; PMCID: PMC12336074. [CrossRef]

- Filippi M, Amato MP, Centonze D, Gallo P, Gasperini C, Inglese M, Patti F, Pozzilli C, Preziosa P, Trojano M. Early use of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies makes the difference in people with multiple sclerosis: An expert opinion. J Neurol. 2022 Oct;269(10):5382-5394. Epub 2022 May 24. Erratum in: J Neurol. 2022 Dec;269(12):6690-6691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11385-4. PMID: 35608658; PMCID: PMC9489547. [CrossRef]

- Balcom, E. F., McCombe, J. A., Kate, M., Vu, K., Martins, K. J. B., Aponte-Hao, S., Luu, H., Richer, L., Williamson, T., Klarenbach, S. W., & Smyth, P. (2024). Geographical variation in medication and health resource use in multiple sclerosis. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques, 52(2), 254–262. [CrossRef]

- Balcom, E. F., Mccombe, J. A., Kate, M. P., Vu, K., Martins, K. J., Aponte-Hao, S., Richer, L., Williamson, T., Klarenbach, S. W., & Smyth, P. S. (2025). Inequities in the use of Disease-Modifying therapy among adults living with Multiple Sclerosis in urban and rural areas in Alberta, Canada. Neurology, 104(3), e210251. [CrossRef]

- Fifield, K. E., Fudge, N. J., Arsenault, S. T., Anthony, S., McGrath, L., Snow, N. J., Clift, F., Stefanelli, M., Ploughman, M., & Moore, C. S. (2025). An overview of multiple sclerosis care in rural and urban Newfoundland and Labrador. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques, 52(6), 904–912. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Huang, W., Duan, Z., Mguni, D. H., Shao, K., Wang, J., & Deng, X. (2023). A survey on algorithms for Nash equilibria in finite normal-form games. Computer Science Review, 51, 100613. [CrossRef]

- Mohamud S, Thompson AJ, Barkhof F, Toosy AT, Ciccarelli O. Real-World Comparison of High-Efficacy Versus Non-High-Efficacy Therapies in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2025 Oct;12(10):2077-2085. Epub 2025 Jul 16. PMID: 40670294; PMCID: PMC12516238. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a Bayesian Markov decision process for disease-modifying therapy selection in resource-limited setting Figure Legend: The Strategy (Induction or Escalation) represents a decision node chosen to maximise expected utility. Following strategy selection, patient compliance is could be either good (G) or poor (P), with probabilities defined as: P(G | Induction, Xₜ) and P(P | Induction, Xₜ) for induction therapy, and P(G | Escalation, Xₜ) and P(P | Escalation, Xₜ) for escalation therapy, where Xₜ denotes the latent clinical and system context. Depending on the selected strategy, compliance state, and context, patients transition to one of three mutually exclusive clinical outcomes: NEDA:No evidence of disease activity, relapse or disease progression, or adverse event (AE). Outcome probabilities are defined as P(NEDA | Compliance, Strategy, Xₜ), P(Relapse/Progression | Compliance, Strategy, Xₜ), and P(AE | Compliance, Strategy, Xₜ), which sum to one for each strategy–compliance combination. Adverse events are further classified as minor adverse events or catastrophic adverse events (e.g., PML:progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), with severity probabilities defined as P(Catastrophic AE | AE, Strategy, Xₜ) and P(Minor AE | AE, Strategy, Xₜ). The context state (Xₜ) represents partially observed real-world factors influencing adherence, risk, and feasibility, including treatment efficacy and safety expectations, infusion access, transportation to an MS centre, access to medical care during adverse events, treatment cost, comorbidity burden, and prior beliefs informed by previous outcomes. Observed events (clinical outcomes, adverse events, and monitoring or access failures) update beliefs about Xₜ for subsequent decision cycles. Overall utility is defined as U(Strategy, Compliance, Outcome, Xₜ) and incorporates clinical benefit, patient burden, cost, monitoring feasibility, and clinician/system risk. This structure permits simulation by parameterising the conditional probabilities from trial data and real-world cohorts and evaluating expected utility for induction versus escalation under context-specific conditions.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a Bayesian Markov decision process for disease-modifying therapy selection in resource-limited setting Figure Legend: The Strategy (Induction or Escalation) represents a decision node chosen to maximise expected utility. Following strategy selection, patient compliance is could be either good (G) or poor (P), with probabilities defined as: P(G | Induction, Xₜ) and P(P | Induction, Xₜ) for induction therapy, and P(G | Escalation, Xₜ) and P(P | Escalation, Xₜ) for escalation therapy, where Xₜ denotes the latent clinical and system context. Depending on the selected strategy, compliance state, and context, patients transition to one of three mutually exclusive clinical outcomes: NEDA:No evidence of disease activity, relapse or disease progression, or adverse event (AE). Outcome probabilities are defined as P(NEDA | Compliance, Strategy, Xₜ), P(Relapse/Progression | Compliance, Strategy, Xₜ), and P(AE | Compliance, Strategy, Xₜ), which sum to one for each strategy–compliance combination. Adverse events are further classified as minor adverse events or catastrophic adverse events (e.g., PML:progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), with severity probabilities defined as P(Catastrophic AE | AE, Strategy, Xₜ) and P(Minor AE | AE, Strategy, Xₜ). The context state (Xₜ) represents partially observed real-world factors influencing adherence, risk, and feasibility, including treatment efficacy and safety expectations, infusion access, transportation to an MS centre, access to medical care during adverse events, treatment cost, comorbidity burden, and prior beliefs informed by previous outcomes. Observed events (clinical outcomes, adverse events, and monitoring or access failures) update beliefs about Xₜ for subsequent decision cycles. Overall utility is defined as U(Strategy, Compliance, Outcome, Xₜ) and incorporates clinical benefit, patient burden, cost, monitoring feasibility, and clinician/system risk. This structure permits simulation by parameterising the conditional probabilities from trial data and real-world cohorts and evaluating expected utility for induction versus escalation under context-specific conditions.

Table 1.

List of the possible outcomes in the DMT Dilemma with real world outcomes and solutions.

Table 1.

List of the possible outcomes in the DMT Dilemma with real world outcomes and solutions.

| Neurologist strategy |

Patient compliance & monitoring |

Perceived clinical outcome |

Real-world data |

Solutions/Comments |

| Early high-efficacy / induction DMT |

Good (medication taken, monitoring completed) |

Best disease control; lower relapse and disability |

High-efficacy DMT use is consistently lower in rural settings (Alberta[4]: OR =0.74 [0.57–0.95] for induction/high-efficacy therapy; NL registry: 3.8% rural vs 8.3% urban vs 20.9% semi-urban.[5] |

Evidence dissemination, lowering the perceived safety issues and development of low cost high efficacy DMTs |

| Early high-efficacy / induction DMT |

Poor (missed doses and/or missed monitoring) |

Severe adverse events, unmanaged toxicity, financial and social harm; clinician blame |

Rural patients have lower neurologist and MS clinic follow-up and higher emergency visits and hospitalizations |

Using hub and spoke telemedicine facilities, AI and digital integration and efficient community health manpower utilisation. |

| Escalation / lower-efficacy DMT |

Good |

Partial disease control; lower short-term risk |

Use of lower-efficacy or older DMTs shows little rural–urban difference (OR: 1.01 [0.83–1.23])[4] |

Current Bayesian Nash Equilibrium in resource limited setting |

| Escalation / lower-efficacy DMT |

Poor |

Slow disease progression; delayed escalation |

Overall DMT use is lower in rural patients (OR:0.83 [0.69–0.99]; for any DMT)[4] |

Belief correction with real world rural evidence about disease progression risks to favour early high efficacy DMTs. Risk transfer to control “tail shocks”. |

| Timing of treatment start |

- |

Delaying treatment can lead to increased disability |

Time to treatment initiation does not differ significantly by geography (HR: 0.89 [0.79, 1.01])[4] |

Continued clinician and patient education about evolving disease dynamics. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).