Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric condition defined by unstable emotions, self-image and relationships, alongside marked impulsivity and self-injury. Although only 1–2 % of adults meet diagnostic criteria, the disorder is over-represented in clinical settings and is often complicated by mood or anxiety comorbidity, making treatment difficult and costly [

1]. Family and twin studies point to a substantial genetic contribution: heritability estimates cluster between 40 % and 60 %, yet environmental stressors, especially early adversity, clearly interact with this liability [

2].

Molecular work has lagged behind. The first genome-wide association study (GWAS) with adequate quality control, published by Witt and colleagues in 2017, contained fewer than 1,000 cases. It reported no genome-wide significant single-nucleotide polymorphisms but did reveal polygenic overlap with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia [

3]. A much larger meta-analysis is now available. Drawing on more than 12,000 cases, [

4] identified eleven novel risk loci and affirmed polygenic risk correlations with externalizing behaviors and somatic conditions. These data allow more focused, hypothesis-driven re-examinations.

Two biological themes deserve particular attention. First, glutamatergic synaptic plasticity: long-term potentiation and depression at NMDA- and AMPA-receptor synapses are central to emotional learning [

5]. Magnetic-resonance spectroscopy has linked altered anterior-cingulate glutamate to impulsivity in BPD, while other imaging studies implicate NMDA dysfunction in mentalization problems [

6,

7]. Second, excessive synaptic pruning: gene variants in complement component 4 (C4) raise schizophrenia risk by enhancing microglia-mediated elimination of synapses [

8]. Given parallels in developmental timing and stress exposure, similar pruning processes may influence BPD.

Using the [

4] summary statistics, we therefore applied three complementary tools—MAGMA gene-set tests, LD-score heritability partitioning and transcriptome-wide association studies—to custom panels that index (i) glutamatergic plasticity, (ii) complement-mediated pruning and (iii) negative-control pathways. Our goal was to clarify whether either mechanism shows enriched genetic signal in BPD and, if so, to outline how these findings might fit into an updated aetiological model.

Methods

Genome-Wide Association Study Summary Statistics

We re-analysed publicly available summary statistics from the largest meta-analysis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) to date, which combined 12,339 clinically diagnosed cases with more than one million controls [

4]. A cohort was selected in which cases with comorbid bipolar disorder or schizophrenia had been removed. The data set, formatted on the GRCh37/hg19 genome build, contained 5,915,125 autosomal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that passed basic quality control and possessed valid p-values. An effective sample size of 41,521 was derived from the study authors' Neff_half value (Neff = 2 × Neff_half).

MAGMA Gene and Gene-Set Analysis

Gene-based testing was conducted with MAGMA version 1.10 [

9]. SNPs were assigned to genes if they lay within 35 kb upstream or 10 kb downstream of an annotated transcription start or stop site, using NCBI 37.3 coordinates. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was modelled with the European reference panel from 1000 Genomes Phase 3. MAGMA's mean-SNP model, which aggregates single-marker statistics into a gene-level test under a fixed-effects framework, was applied.

Seven a priori gene sets were evaluated competitively. Two captured glutamatergic signalling: the original candidate glutamate-related (CGR) set of 23 genes and an expanded glutamate/synaptic plasticity list of 130 genes. Three addressed synaptic pruning processes: a shortened set of 38 core pruning genes, a broader list of 262 pruning-related genes, and a "specific pruning" subset of 225 genes that excluded 37 overlapping with the expanded glutamate collection. Finally, two negative controls were included—a 104-gene monoaminergic list and 184 brain housekeeping genes. All sets were assembled from earlier molecular and genetic literature.

Competitive enrichment compared the mean gene Z-scores for each set with those of all other protein-coding genes via a one-sided t-test. Gene-level significance adhered to Bonferroni correction for 18,264 tested genes (p < 2.74 × 10⁻⁶). Gene-set p-values were adjusted for seven hypotheses with both Bonferroni (p < 0.0071) and Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedures.

Partitioned Heritability Analysis

We applied stratified linkage disequilibrium (LD) score regression [

10] to determine whether specific biological pathways account for more borderline personality disorder (BPD) heritability than expected by chance. Summary statistics from the largest BPD genome-wide association meta-analysis currently available (12,339 cases, > 1 million controls; [

4]) served as input. After standard quality control, 5,915,125 autosomal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) remained; the effective sample size was 41,521.

Seven prespecified gene sets were evaluated. Two captured glutamatergic mechanisms—(i) 23 original candidate glutamate-related (CGR) genes centred on NMDA/AMPA signalling and (ii) 130 genes spanning broader glutamate and synaptic-plasticity cascades. Three addressed synaptic pruning—(iii) a 38-gene core list, (iv) an expanded 262-gene list, and (v) a 225-gene "pruning-specific" subset obtained by removing 37 genes shared with the expanded glutamate set. Two negative-control sets were included: (vi) 101 monoaminergic genes and (vii) 182 housekeeping genes expressed in brain tissue. Coordinates were taken from GRCh37/hg19 and extended 10 kb upstream and downstream of each transcript. LD scores for European ancestry were calculated from 1000 Genomes Phase 3.

For every annotation, stratified LD score regression produced an enrichment statistic—the ratio of the proportion of SNP heritability to the proportion of SNPs in the set—along with a jack-knife standard error. One-tailed p-values tested whether enrichment exceeded one. Chi-square values for SNPs in a set were compared with those outside the set using Mann–Whitney U tests. All seven tests were Bonferroni-corrected (α = 0.0071).

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study

We investigated whether genetically regulated expression in key brain regions contributes to borderline personality disorder (BPD). Summary-PrediXcan (S-PrediXcan; [

11]) was applied to the borderline GWAS meta-analysis of 12,339 cases and more than one million controls [

4]. Prediction weights were taken from GTEx version 8 MASHR models [

12]. Seven neuroanatomical tissues—frontal cortex (BA9), anterior cingulate (BA24), broader cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, nucleus accumbens and caudate—were analysed.

After harmonising alleles, single-variant statistics (log-odds/SE) were converted to z-scores and projected onto gene models. Seven pre-specified gene sets were evaluated post hoc: (1) 23 original glutamate-related targets, (2) 130 gene glutamate/synaptic-plasticity expansion, (3) 38-gene shortened pruning list, (4) 262-gene expanded pruning list, (5) 225-gene pruning-specific subset (pruning minus glutamate overlap), and two negative-control sets, monoaminergic (101 genes) and housekeeping (182 genes).

Gene-tissue p-values were obtained from S-PrediXcan z-scores. We controlled the false-discovery rate (FDR) across all gene-tissue pairs using Benjamini–Hochberg (q < 0.05) and applied a per-tissue Bonferroni threshold. Enrichment in absolute z-scores for each target set versus the remaining genome was tested with one-sided Mann–Whitney U statistics.

Results

MAGMA Gene and Gene-Set Analysis

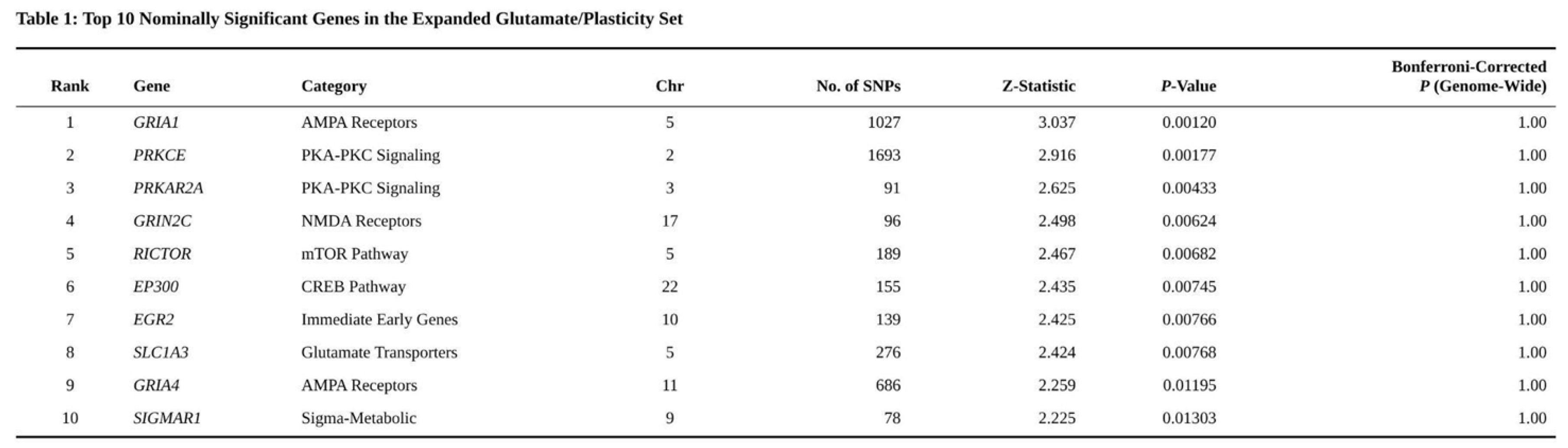

Of the 18,264 genes analysed, eight surpassed the Bonferroni threshold. Lead signals mapped to SGCD (p = 4.8 × 10⁻⁹), MMAB (p = 9.2 × 10⁻⁹) and MVK (p = 1.3 × 10⁻⁸), mirroring loci reported in the original GWAS. A further 185 genes displayed suggestive evidence (p < 0.001), while 2,253 reached nominal significance (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1. Please add table caption.

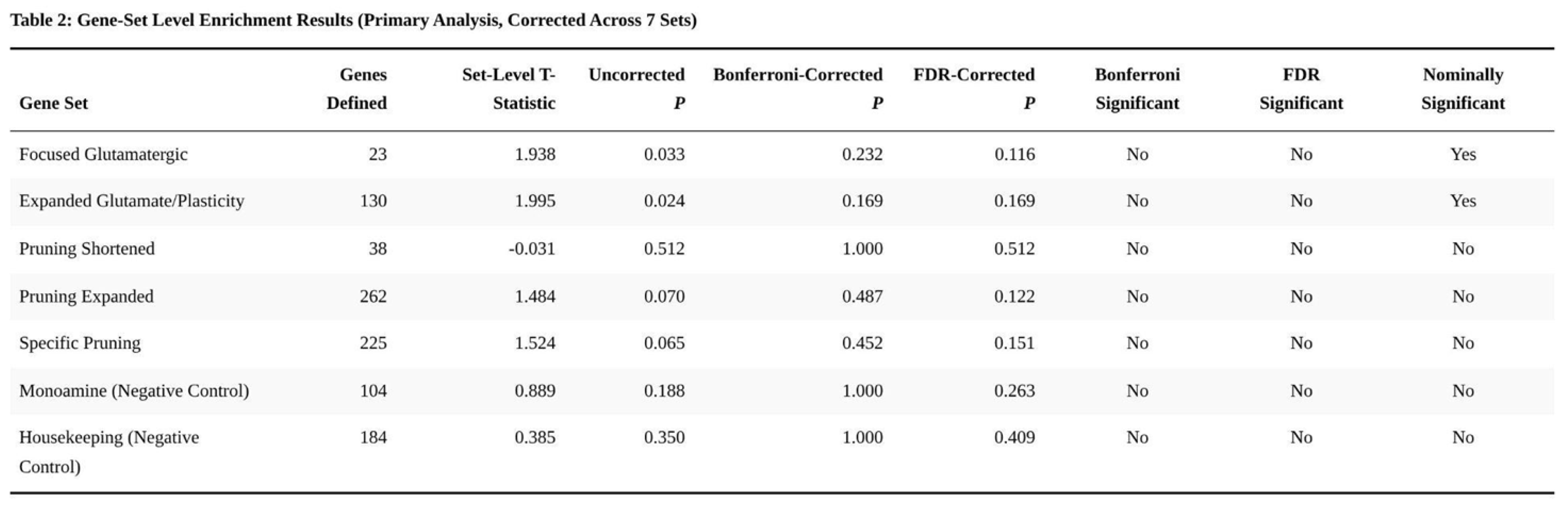

Nominal enrichment emerged for the Focused Glutamatergic targets (p = 0.033) and the expanded glutamate/plasticity set (p = 0.024). These signals were largely driven by GRIA1 (p = 0.0012) and GRIN2C (p = 0.0062). After Bonferroni adjustment for seven tests, neither set remained significant (corrected p = 0.232 and 0.169, respectively), nor did either survive FDR control (Table 2).

No pruning-related collection showed statistical evidence of enrichment (shortened pruning p = 0.512; expanded pruning p = 0.070; specific pruning p = 0.065), and both negative-control sets were non-significant (monoamine p = 0.188; housekeeping p = 0.350).

Supplementary non-parametric comparisons echoed these findings: CGR genes carried modestly higher Z-scores than monoamine (Mann–Whitney p = 0.042) or housekeeping genes (p = 0.038), yet a Kruskal–Wallis test across all seven groups was unremarkable (p = 0.579).

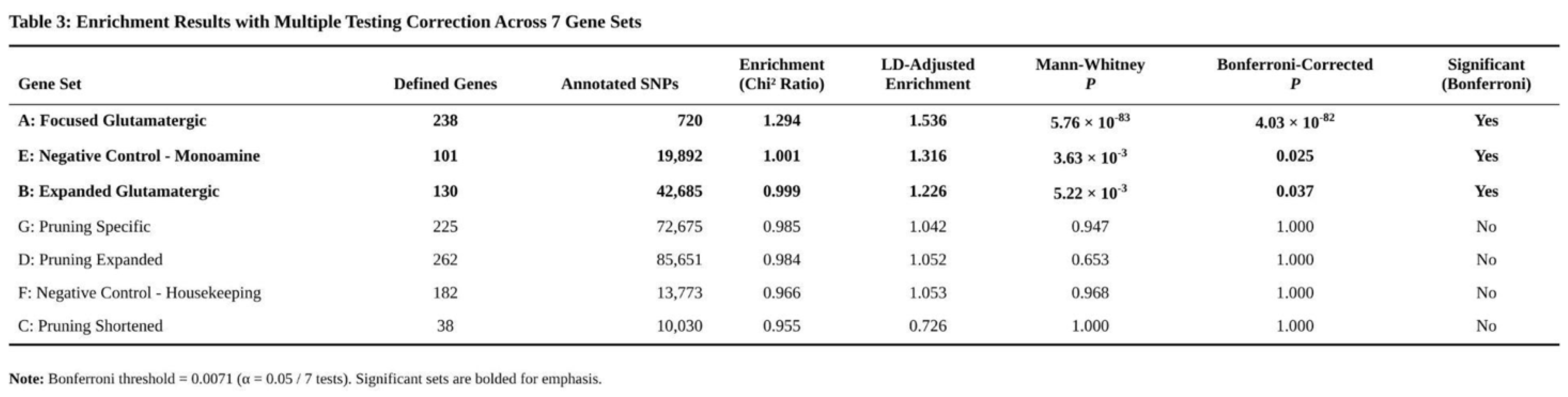

Partitioned Heritability by Pathway

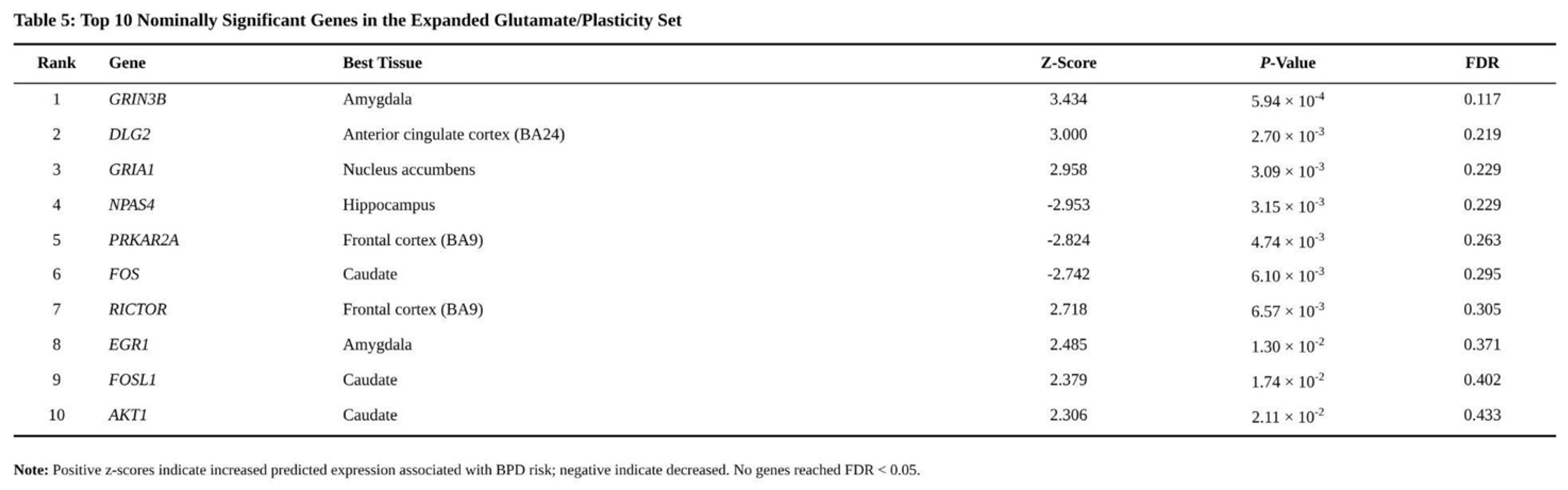

Three of the seven gene sets showed significant enrichment after multiple-test correction (Table 3). The 23-gene CGR list yielded the strongest effect: 1.54-fold enrichment (0.15 % of SNPs) with U = 2.9 × 10^7, p = 5.8 × 10^–83 (Bonferroni-adjusted p ≈ 4 × 10^–82). The 130-gene glutamate/synaptic-plasticity set was also enriched (1.23-fold; 0.72 % of SNPs; p = 0.0052; adjusted p = 0.037). Unexpectedly, the monoaminergic control set showed a comparable 1.32-fold enrichment (0.34 % of SNPs; p = 0.0036; adjusted p = 0.025), suggesting shared polygenic influences across psychiatric phenotypes.

No pruning-related set reached significance: the 38-gene core list showed 0.73-fold enrichment (p ≈ 1.0), the 262-gene expanded list 1.05-fold (p = 0.653), and the 225-gene pruning-specific list 1.04-fold (p = 0.947). The housekeeping control was similarly null (1.05-fold; p = 0.968). Non-parametric comparisons echoed these findings; overall differences in chi-square distributions among all seven sets were non-significant (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.579).

Transcriptome-Wide Associations in Targeted Gene Sets

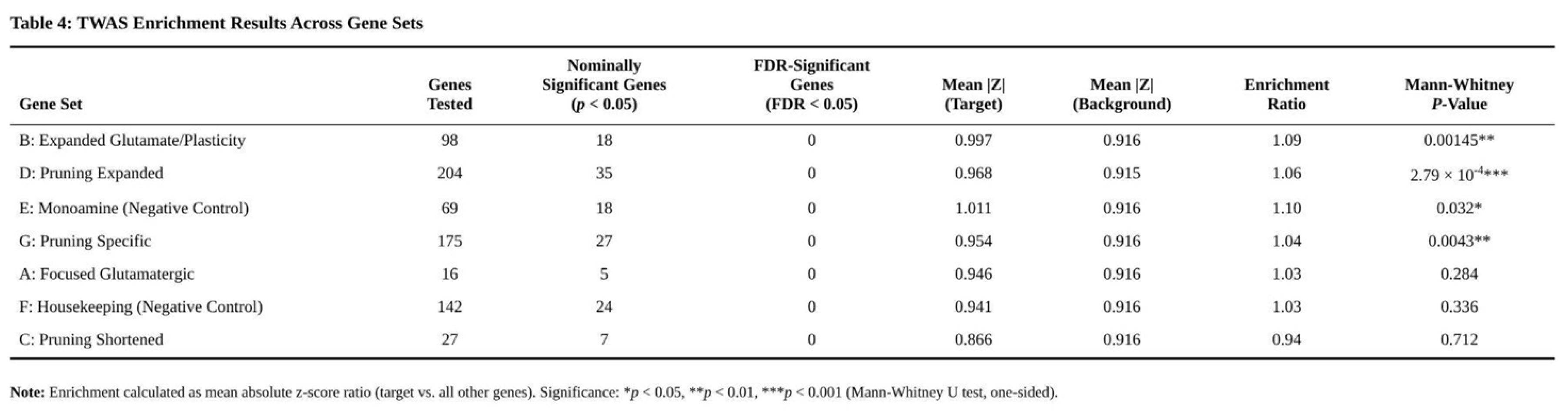

Roughly 70,000 gene-tissue combinations (≈16,000 genes) were assessed. Ninety associations reached the global FDR threshold, representing 43 unique genes, and 25 of these (12 genes) remained significant after tissue-specific Bonferroni correction. None belonged to the seven hypothesis-driven sets, underscoring the subtlety of transcriptomic effects in BPD.

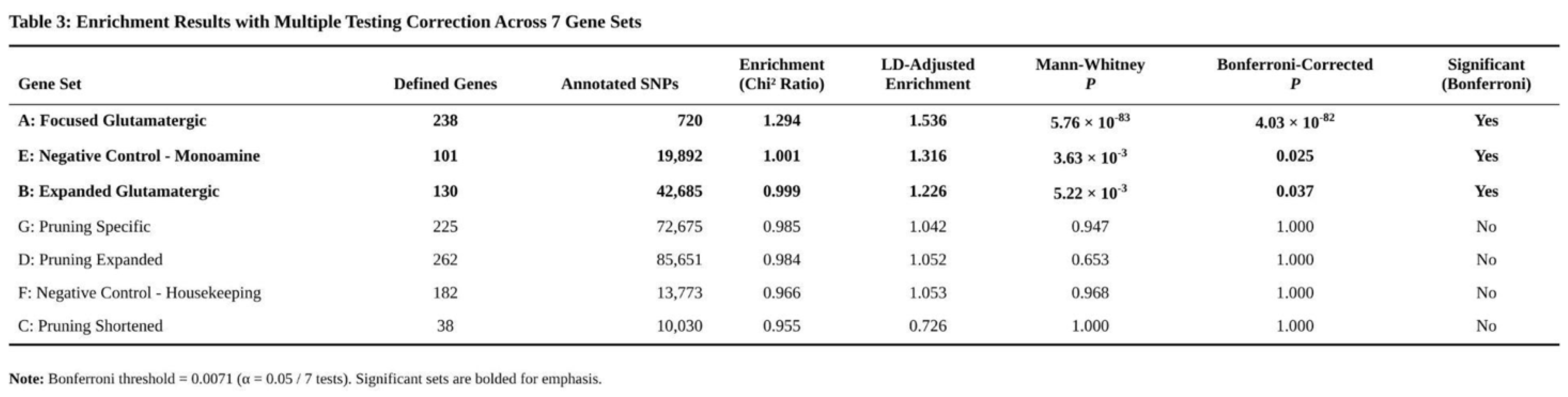

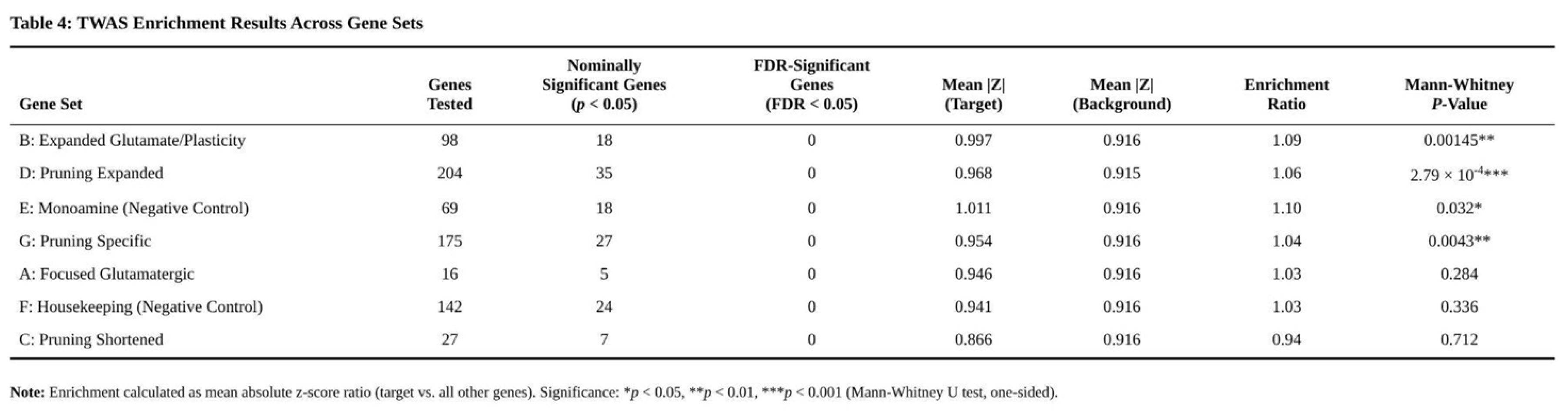

Nevertheless, enrichment analyses identified a signal in glutamatergic pathways (Table 4). The 130-gene glutamate/synaptic-plasticity set showed a 1.09-fold increase in mean absolute z-score relative to background (U = p = 0.00145). Eighteen genes were nominally associated (p < 0.05), notably GRIN3B in amygdala (z = 3.43, higher predicted expression), DLG2 in anterior cingulate (z = 3.00), GRIA1 in nucleus accumbens (z = 2.96) and NPAS4 in hippocampus (z = −2.95). The original 23-gene glutamate list displayed weaker enrichment (1.03-fold, p = 0.284); five members, including GRIA1 and GRIN2A, were nominally significant.

Results for pruning candidates were mixed. The 262-gene expanded pruning set yielded modest enrichment (1.06-fold, p = 2.8 × 10⁻⁴) with 35 nominal hits—examples include EFNA1 in amygdala (z = 3.68) and TAP2 in amygdala (z = −3.31). When glutamatergic overlap was removed (pruning-specific subset), enrichment dropped to 1.04-fold (p = 0.0043). The 38-gene shortened pruning list showed no signal (0.94-fold, p = 0.712).

Control sets offered perspective. Monoaminergic genes were unexpectedly enriched (1.10-fold, p = 0.032), whereas housekeeping genes were not (1.03-fold, p = 0.336). Across enriched sets, positive z-scores predominated in ionotropic receptor genes (e.g., GRIN3B, GRIA1), while negative z-scores appeared in regulatory or scaffolding components (e.g., NPAS4, DLG2) (Table 5).

In summary, S-PrediXcan points to a diffuse, polygenic contribution from glutamatergic and synaptic-plasticity genes in BPD, with no single gene achieving experiment-wide significance after stringent correction.

Discussion

General Interpretations of Results

The three analytical streams—gene-based testing, stratified LDSC, and brain-focused TWAS—converged on a single message: common variation influencing glutamatergic signalling and synaptic plasticity probably contributes to borderline personality disorder (BPD) risk. In MAGMA, the canonical glutamate list and its plasticity expansion both showed nominal competitive enrichment driven by loci such as GRIA1 and GRIN2C, although neither set survived the stringent multiple-test correction applied across all hypotheses. LDSC offered firmer evidence, yielding LD-adjusted enrichments between 1.23- and 1.54-fold for the same annotations. TWAS extended the pattern into functional space; plasticity genes carried slightly larger absolute z-scores in seven emotion-relevant cortical and sub-cortical tissues, with scattered nominal hits—including higher predicted expression of GRIN3B and GRIA1 and lower predicted expression of NPAS4 and DLG2—yet no gene cleared the transcriptome-wide FDR threshold.

In contrast, multiple pruning definitions—whether the concise 38-gene list, a broad 262-gene panel, or a pruning-specific subset that excluded glutamatergic overlap—consistently failed to enrich in any method. This stands in marked contrast to schizophrenia and autism, where pruning signals typically surface, and suggests that excessive synaptic elimination is unlikely to be a central genetic theme in BPD.

Two points warrant caution. First, the monoaminergic "negative-control" set displayed modest enrichment in LDSC and TWAS, hinting at non-specific polygenic inflation that often accompanies cross-disorder GWAS. Second, the absence of genome-wide significant single-gene findings and reliance on set-level trends underline the highly polygenic, small-effect nature of BPD. Even so, agreement across three orthogonal techniques strengthens confidence that glutamatergic plasticity, rather than pruning pathways, deserves closer scrutiny.

Integrating Neurobiological Evidence

Published work supports a central role for glutamate in BPD-relevant circuits. NMDA-dependent plasticity has been linked to mentalization problems [

7] and ACC glutamate correlates with impulsivity [

6]. Reviews of stress biology show that glucocorticoids bidirectionally modulate glutamatergic strength, causing either excitotoxic overdrive or plasticity failure [

13]. Neurotrophic cascades (mTOR, CREB, BDNF/NGF) also pivot on balanced glutamate signalling [

14,

15]. These themes mirror the mixed directions in our genetic data.

A bidirectional Plasticity Hypothesis

We therefore propose that common variants in plasticity genes disturb glutamate-dependent learning in limbic–prefrontal loops in two opposite ways. Alleles that enhance AMPA/NMDA throughput may lock fear or rejection memories by excessive long-term potentiation; alleles that weaken scaffolding or trophic support may blunt long-term depression and prevent updating of maladaptive schemas. The net result is emotional lability, hyper-reactivity and impaired recovery—core clinical features of BPD.

At the molecular level, hyper-plastic alleles could overactivate CaMKII/mTOR, risking excitotoxicity, whereas hypo-plastic alleles could dampen CREB transcription and limit synaptic remodelling. Circuit-level consequences include amygdala hypersensitivity, rigid prefrontal control and fragile hippocampal contextualisation.

Potential Mechanistic and Clinical Implications

The genetic tilt we see toward synaptic plasticity meshes well with earlier work that ties NMDA-receptor glitches to the mood swings and "mind-reading" difficulties so common in borderline personality disorder (BPD) [

7]. Should these results hold up, they hint at a fresh treatment angle: drugs that tune glutamate and boost plasticity—ketamine, memantine, riluzole, and similar agents already explored in mood disorders—may also calm the storm in BPD [

16]. In the long run, clinicians might even sort patients by a polygenic "plasticity score" to predict who will benefit most from such medications.

Looking at the circuitry as a whole, our data offer a way to explain the wild swings between raw emotion and numb detachment that characterise BPD. On one side, ramped-up AMPA and NMDA currents could sear memories of fear or abandonment into the network; on the other, a pared-down postsynaptic scaffold leaves the system less able to remodel and bounce back. The result is a brain that over-learns the bad and under-updates the good, trapping the person in a cycle of reactivity with little room for recovery.

Limitations and Future Directions

Caution is warranted. Many enrichments were nominal and occasionally paralleled by signal inflation in a monoaminergic control set, hinting at residual cross-trait confounding, despite a cohort was used in which cases with comorbid bipolar disorder or schizophrenia had been removed. The primary GWAS on which we relied remains in preprint form, and replication in larger, ethnically diverse cohorts is essential, particularly for rare variants and cell-type–specific effects. In addition, several top loci unrelated to glutamatergic biology (for example, SGCD, FOXP2) underscore the polygenic and heterogeneous nature of BPD. Finally, mechanistic hypotheses should be tested through multimodal work—combining genetics with spectroscopy, functional imaging and pharmacological challenge—to evaluate whether glutamatergic plasticity truly mediates symptom expression.

Conclusion

Taken together, our analyses extend BPD genetics beyond broad cross-disorder overlap, highlighting synaptic plasticity genes as plausible contributors while casting doubt on a central role for pruning pathways. Although the effect sizes are small, the convergence across analytic methods provides a rationale for integrating glutamatergic plasticity into etiological models and therapeutic trials.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

References

- Gunderson, JG; Herpertz, SC; Skodol, AE; et al. Borderline personality disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4, 18029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distel, M.A.; Trull, T.J.; Derom, C.A.; Thiery, E.W.; Grimmer, M.A.; Martin, N.G.; Willemsen, G.; Boomsma, D.I. Heritability of borderline personality disorder features is similar across three countries. Psychol. Med. 2007, 38, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, SH; Streit, F; Jungkunz, M; et al. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder reveals genetic overlap with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, F; Awasthi, S; Hall, AS; et al. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder identifies 11 loci and highlights shared risk with mental and somatic disorders. medRxiv 2025;2024, 11.12.24316957. [Google Scholar]

- Malenka, RC; Bear, MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron 2004, 44, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerst, M.; Weber-Fahr, W.; Tunc-Skarka, N.; Ruf, M.; Bohus, M.; Schmahl, C.; Ende, G. Correlation of Glutamate Levels in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex With Self-reported Impulsivity in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder and Healthy Controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosjean, B.; Tsai, G.E. NMDA neurotransmission as a critical mediator of borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007, 32, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekar, A.; Bialas, A.R.; De Rivera, H.; Davis, A.; Hammond, T.R.; Kamitaki, N.; Tooley, K.; Presumey, J.; Baum, M.; Van Doren, V.; et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 2016, 530, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, C.A.; Mooij, J.M.; Heskes, T.; Posthuma, D. MAGMA: Generalized Gene-Set Analysis of GWAS Data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulik-Sullivan, B.K.; Loh, P.R.; Finucane, H.K.; Ripke, S.; Yang, J.; Patterson, N.; Daly, M.J.; Price, A.L.; Neale, B.M.; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, A.N.; Dickinson, S.P.; Bonazzola, R.; Zheng, J.; Wheeler, H.E.; Torres, J.M.; Torstenson, E.S.; Shah, K.P.; Garcia, T.; Edwards, T.L.; et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popoli, M.; Yan, Z.; McEwen, B.S.; Sanacora, G. The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, R.S.; Monteggia, L.M. A Neurotrophic Model for Stress-Related Mood Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manji, H.K.; Quiroz, J.A.; Sporn, J.; Payne, J.L.; Denicoff, K.; Gray, N.A.; Zarate, C.A., Jr.; Charney, D.S. Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for Difficult-to-Treat depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 53, 707–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanacora, G.; Zarate, C.A.; Krystal, J.H.; Manji, H.K. Targeting the glutamatergic system to develop novel, improved therapeutics for mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |