Introduction

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), typically delivered in ≥5 Gy fractions, has emerged as an ultra-hypofractionated option for localized prostate cancer with disease control and late gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity comparable to conventional fractionation and moderate hypofractionation (1). By concentrating dose into fewer sessions and using even larger doses, SBRT reduces clinic visits and institutional resource utilization, improving patient convenience and system efficiency (2). The large dose per fraction may also favor the low alpha/beta ratio of prostate cancer. Nevertheless, given the rectum`s immediate proximity to the prostate, concerns persist regarding unintentional rectal irradiation which may result in both early and late rectal toxicity after prostate SBRT. Warranting continued surveillance, standardized reporting and strict adherence to rectal dose-volume constraints is therefore essential to SBRT plan quality (2), (3).

Rectal spacers that are placed between the prostate and rectum have emerged as an effective tool to increase the distance between these anatomical structures in order to limit radiation-induced rectal injury (4), (5) (6).

While the dosimetric benefit of rectal spacing has been established in broad terms (5) (6), (7) (8), questions remain regarding spacer placement, its geometry, and the ability to provide a uniform base to apex separation of the prostate, and how these factors affect rectal dose distribution (9). Particularly, this separation is pertinent at the prostate apex, where the gland lies in close proximity to the anterior rectal wall, and positional deviations may result in increasing rectal dose exposure (10). Evidence ais limited in addressing whether separation at specific anatomical landmarks confers greater dosimetric benefit.

The present study was designed to evaluate the physical spacing between the prostate and the rectum and its association with rectal dose sparing, particularly at the inferior portion of the prostate, in patients undergoing SBRT with the Bioprotect balloon spacing apparatus.

Methods

Patients and Simulation

Thirty-three consecutive patients with localized prostate cancer (clinical stage T1-T2N0M0) who underwent SBRT were followed. Risk classification was assigned according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Prostate Cancer, version 2.2021 (11). All patients had low- or intermediate-risk diseases. The study was approved by the institutional review board. All patients were consented and implanted with a biodegradable balloon spacer (The BioProtect Balloon Implantation System, BioProtect Ltd.) that was positioned between the prostate and rectum under local anesthesia using transrectal ultrasound guidance (5). Computed tomography (CT) simulation and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) were done approximately one week after spacer implantation. Patients were scanned in the supine position with 1-mm slice thickness reconstruction. Patient’s preparations included full bladder and empty rectum.

Treatment Planning

Treatment planning was done using Eclipse (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and Pinnacle (Philips Medical Systems, Fitchburg, WI, USA). The prostate, organs at risk (OAR), and the balloon spacer were delineated on the planning CT images. The clinical target volume (CTV) for low-/ intermediate-risk patients comprised the prostate and proximal 2 cm of the seminal vesicles (SVs) according to the risk classification. The planning target volume (PTV) was generated by adding a margin of 3 mm posteriorly and 5 mm in all other directions around the CTV.

Radiotherapy

SBRT total dose of 36.25Gy was delivered to the PTV in five fractions of 7.25Gy each, to 95% of the PTV volume every alternate weekday. Dose constraints for organ at risk were V36.25 Gy < 5%, 32.625 Gy < 11%, V29 Gy < 20%, V27.19 Gy < 25%, V18.13 Gy < 50% for rectum, V36.25 Gy < 8%, V18.13 Gy < 40%, V37 Gy < 5 cc for bladder, and V29.5 Gy < 50% for penile bulb (PB). Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) was obtained daily for patient setup verification, and at the completion of the SBRT course to evaluate spacer position stability and anatomical consistency throughout treatment.

Prostate-Rectum Separation

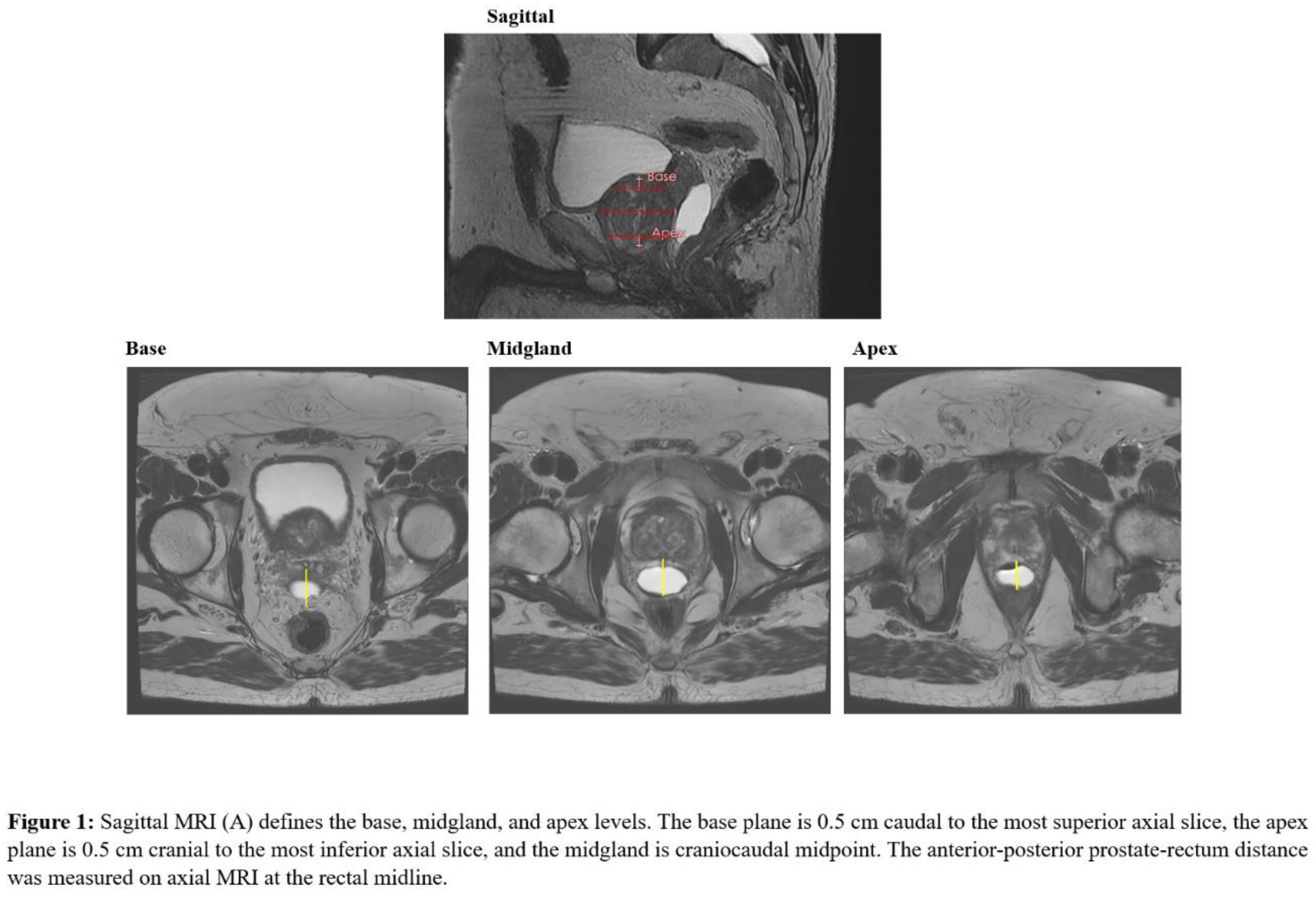

Prostate-rectum spacing was assessed in axial plane at mid-gland (center of the CTV), apex, and base. The mid-gland was defined as the central slice of the contoured prostate. To avoid partial-volume effects at the extremes of the gland, the apical plane was defined as 0.5 cm superior to the most caudal prostate slice and the base plane 0.5 cm inferior to the most cranial slice, as previously described (12). On each axial plane, spacing was measured at midline as the linear distance between the posterior prostate surface and the anterior rectal wall (

Figure 1).

Patients were stratified into three spacing categories at each axial level, defined clinically by prior studies that established a target separation of 10-14 mm (5), (8), (13) so the medium group was defined within this range, with the corresponding small and large groups <10 mm and >14 mm, respectively. Mean rectal and bladder doses (Dmean), defined as the average dose delivered to each organ, and rectal dose-volume histogram parameters V18.25 to V36.25 Gy, were compared across spacing categories to evaluate the association of perirectal separation with rectal and bladder dose distributions.

Follow-Up Protocol

Patients were seen every 3-6 months after SBRT completion. Acute genitourinary (GU) and GI radiation toxicities occurring within 90 days after SBRT completion were confirmed based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0, and included urinary frequency, retention, urgency, urinary tract pain, and incontinence, occurring within 90 days after SBRT. Acute GI toxicity was defined as intestinal-related symptoms occurring within 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient, treatment, and dosimetric characteristics, with continuous variables reported as mean, standard deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR), and range as appropriate.

Dose-volume relationships were evaluated using linear regression models, in which rectal VX values (V18.25- V36.25 Gy) and mean and maximum doses to the rectum, bladder, and penile bulb were modeled as functions of prostate-rectum separation at the apex, midgland, and base.

In a secondary analysis, prostate-rectum distance at each anatomical level was dichotomized as <14 mm versus ≥14 mm. Differences in mean percentage rectal volume at each dose level and in organ-at-risk and mean doses were compared between spacing groups using two-sided t-tests). All statistical tests were two-sided, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The patients mean age was 72 years with a mean PSA of 8.4 ng/mL. The majority of patients had intermediate-risk disease, characterized by Gleason 7 (55%) and clinical stage T1c (55%). The mean baseline IPSS (International Prostate Symptom Score) was 13.9, with moderate symptoms predominating and severe symptoms infrequent. The mean (SD) prostate volume was 56.7 (16.6)cc, while bladder and rectal volumes averaged 356.7 (288.9)cc and 67.7 (22.6)cc, respectively.

Post-implant dosimetric and anatomical parameters are summarized in

Table 2. Rectal DVH values decreased consistently across escalating dose levels, with a mean rV18.25 Gy of 8.0% declining to 0.08% at rV36.25 Gy. The mean rectal dose was 6.7%. Bladder and penile bulb mean doses were 8.0% and 3.9%, respectively. Prostate-rectum separation achieved by the spacer averaged 16.6 mm across the gland, with mean apical, midgland, and basal distances of 15.9 mm, 17.1 mm, and 17.3 mm, respectively. All baseline, dosimetric, and spacing parameters are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Post-Implant Dosimetric Parameters. Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; AUA, American Urological Association; DVH, dose–volume histogram; OAR, organ at risk.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Post-Implant Dosimetric Parameters. Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; AUA, American Urological Association; DVH, dose–volume histogram; OAR, organ at risk.

| Characteristics |

Mean (SD) |

Median (IQR) |

Min, Max |

| Age (y) |

| |

72.12 (6.65) |

73 (6.0) |

47, 85 |

| PSA (ng/mL) |

| |

8.40 (3.78) |

6.8 (5.3) |

3.3, 17.8 |

| Gleason Score, n (%) |

| 6 |

10 (30.30%) |

|

|

| 7 |

18 (54.55%) |

|

|

| ≥ 8 |

5 (15.15%) |

|

|

| Clinical T-Stage, n (%) |

| T1c |

18 (54.55%) |

|

|

| T2a |

9 (27.27%) |

|

|

| T2b |

6 (18.18%) |

|

|

| IPSS Score |

| |

13.85 (7.14) |

14.0 (11.0) |

1, 25 |

| AUA symptom score, n (%) |

| 0 |

1 (3.03%) |

|

|

| 1-7 (mild) |

13 (39.39%) |

|

|

| 8-19 (moderate) |

16 (48.48%) |

|

|

| 20-35 (severe) |

3 (9.09%) |

|

|

| Prostate Volume (cc) |

| |

56.70 (15.46) |

51.60 (17.27) |

35.4, 107.46 |

| Bladder Volume (cc) |

| |

293.29 (275.12) |

160.8 (339.3) |

19.53, 120.3 |

| Rectal Volume (cc) |

| |

68.03 (20.96) |

68.7 (23.66) |

19.53, 120.3 |

| Post-Implant Rectal DVH (%) |

| rV18.25 Gy |

8.02 (3.68) |

7.97 (4.04) |

1.35, 18.43 |

| rV21.75 Gy |

5.27 (3.11) |

5.46 (4.04) |

0.47, 15.18 |

| rV25.38 Gy |

2.93 (2.59) |

2.62 (2.72) |

0.06, 12.01 |

| rV29 Gy |

1.18 (1.30) |

0.88 (1.88) |

0.00, 5.50 |

| rV32.63 Gy |

0.46 (0.78) |

0.09 (0.61) |

0.00, 3.39 |

| rV36.25 Gy |

0.08 (0.22) |

0.00 (0.04) |

0.00, 1.10 |

| Rectal Mean Dose |

6.71 (4.15) |

5.91 (5.10) |

0.54, 19.36 |

| Post-Implant OAR Dose Volume (%) |

| Bladder Mean Dose |

8.04 (3.77) |

8.72 (5.29) |

1.22, 15.69 |

| Penile Bulb Mean Dose |

3.92 (3.09) |

2.47 (3.36) |

0.55, 12.61 |

| Post-Implant Prostate–Rectum Separation (mm) |

| Apical Distance |

15.93 (4.30) |

16.33 (5.22) |

3.60, 24.45 |

| Midgland Distance |

17.12 (4.69) |

17.21 (6.10) |

6.94, 25.90 |

| Base Distance |

17.25 (8.05) |

15.29 (7.55) |

2.78, 39.14 |

| Average Distance |

16.63 (3.55) |

16.02 (3.82) |

11.04, 23.83 |

Prostate-Rectum Distance

Prostate-rectum distance varied across anatomical levels. At the apex, two-thirds of patients (67%) achieved ≥14 mm spacing, while 15% each had <10 mm and 10-14 mm separation. At the midgland, most patients (70%) had ≥14 mm spacing, with fewer showing 10-14 mm (21%) or <10 mm (6%). At the base, ≥14 mm spacing was observed in 61% of patients, whereas <10 mm and 10-14 mm separation was each present in 18%. Overall, ≥14 mm spacing predominated across all planes.

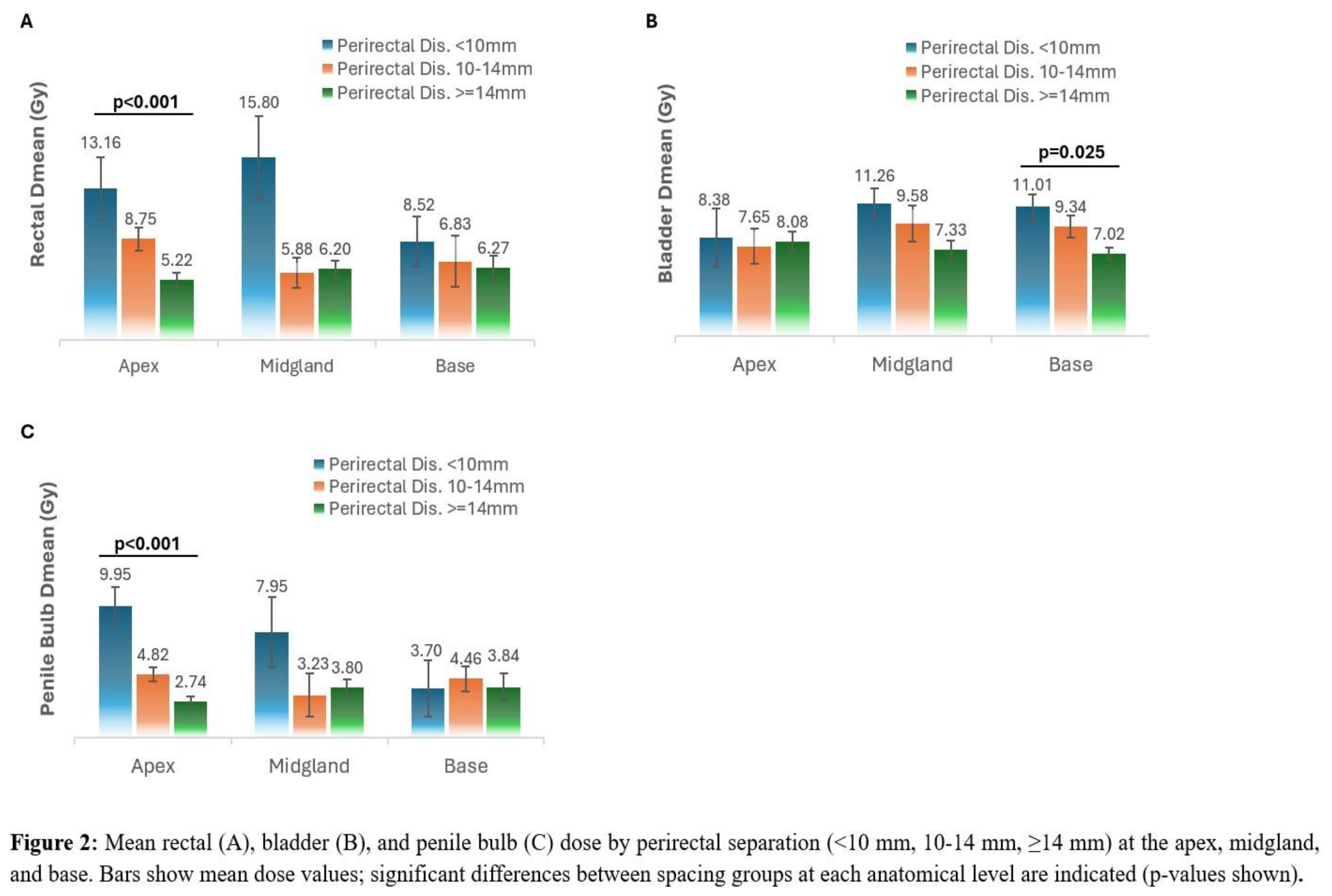

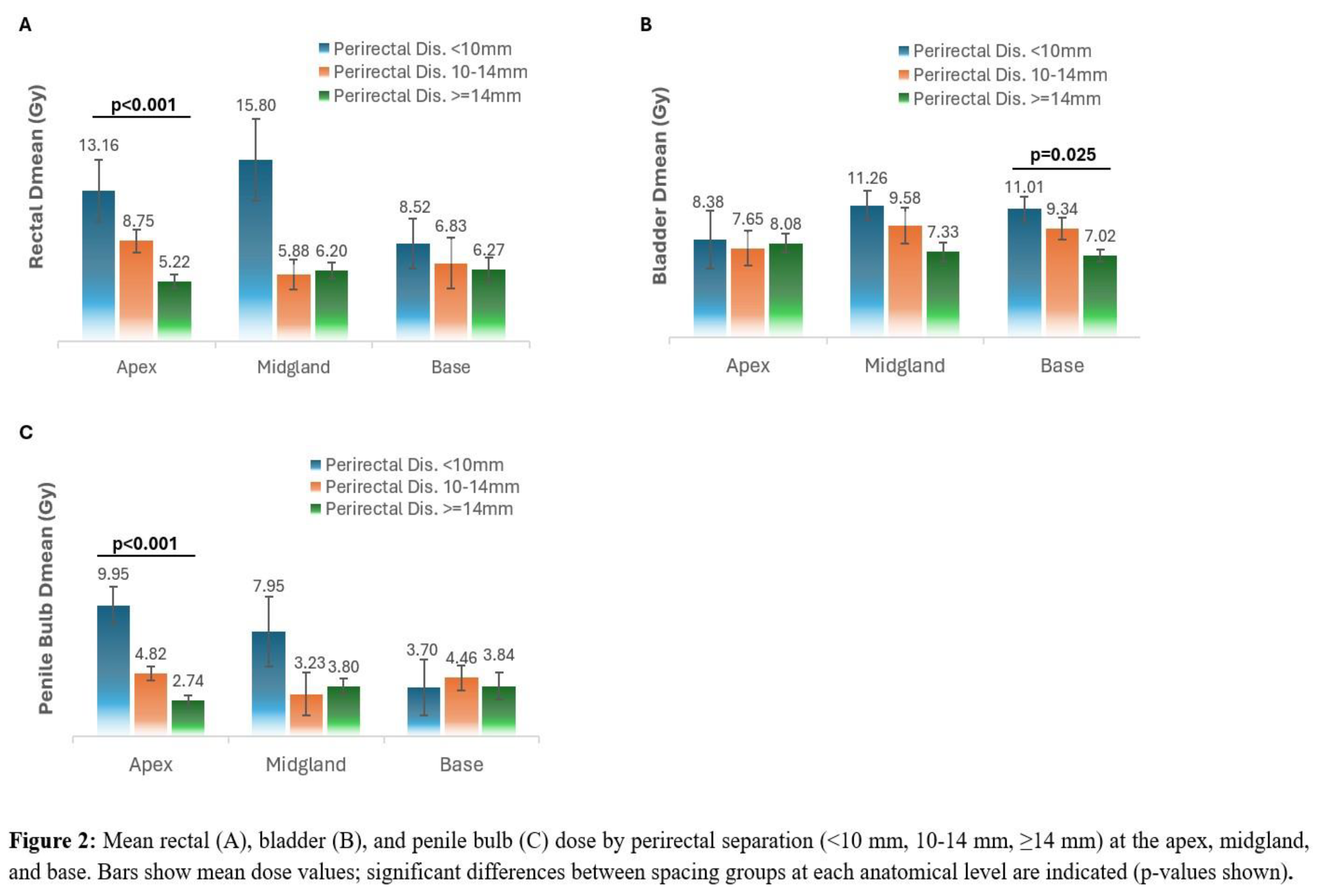

Anatomical-Level Dose Response to Spacer Separation

For both apex and midgland, increasing perirectal distance was associated with a progressive reduction in rectal volume. At the apex, patients with ≥14 mm spacing had significantly lower rectal volumes at 29 Gy, 32.63 Gy, and 36.25 Gy compared with those with <10 mm or 10-14 mm spacing (p=0.004, p=0.021, and p=0.022, respectively). The increased apical separations was also significantly associated with lower rectal Dmean (p < 0.001), with no significant change at the midgland or base (p = 0.520 and 0.397, respectively). (

Figure 2,

Table 2).

At the midgland, patients with ≥14 mm spacing had lower rectal volumes at 29 Gy (p=0.023) and 32.63 Gy (p=0.006). At lower dose levels (18.25, 21.75, and 25.38 Gy), rectal volumes tended to decrease with greater spacing, but differences did not reach statistical significance (all p>0.3). At the base, none of the rectal dose-volume endpoints differed significantly between spacing groups (all p≥0.54) (

Figure 3,

Table 2).

Table 2.

Rectal, bladder, and penile bulb dosimetry by prostate-rectum separation (<10 mm, 10-14 mm, ≥14 mm) at the apex, midgland, and base. Values are mean ± SE; bold p-values indicate statistically significant differences between spacing groups.

Table 2.

Rectal, bladder, and penile bulb dosimetry by prostate-rectum separation (<10 mm, 10-14 mm, ≥14 mm) at the apex, midgland, and base. Values are mean ± SE; bold p-values indicate statistically significant differences between spacing groups.

| |

Rectal Dose Volume |

Rectal Dose (Gy) |

Bladder Dose (Gy) |

Penile Bulb Dose (Gy) |

| Anatomical Level |

Separation |

18.25 Gy (mean ± SE) |

21.75 Gy (mean ± SE) |

25.38 Gy (mean ± SE) |

29.0 Gy (mean ± SE) |

32.63 Gy (mean ± SE) |

36.25 Gy (mean ± SE) |

Dmean

(mean ± SE) |

Dmean

(mean ± SE) |

Dmean

(mean ± SE) |

| Apex |

<10 mm |

9.0 (0.8)% |

6.5 (0.2)% |

3.9 (1.6)% |

2.4 (0.8)% |

1.1 (0.7)% |

0.3 (0.2)% |

13.1 (2.6) |

8.4 (2.5) |

9.9 (1.4) |

| 10-14 mm |

8.6 (1.5)% |

5.4 (0.6)% |

3.3 (0.6)% |

2.0 (0.3)% |

0.8 (0.5)% |

0.1 (0.1)% |

8.7 (1.0) |

7.6 (1.5) |

4.8 (0.5) |

| ≥14 mm |

7.7 (0.7)% |

5.0 (0.7)% |

2.7 (0.6)% |

0.8 (0.1)% |

0.2 (0.0)% |

0.03 (0.0)% |

5.2 (0.8) |

8.0 (0.8) |

2.7 |

| p-value |

0.479 |

0.471 |

0.417 |

0.004 |

0.021 |

0.022 |

<0.001 |

0.946 |

<0.001 |

| Midgland |

<10 mm |

8.5 (2.0)% |

6.8 (0.4)% |

4.6 (0.5)% |

3.2 (0.0)% |

1.8 (0.3)% |

0.5 (0.4)% |

15.8 (3.5) |

11.3 (1.2) |

8.0 (4.6) |

| 10-14 mm |

8.2 (0.7)% |

5.5 (0.6)% |

3.3 (0.5)% |

1.6 (0.3)% |

0.8 (0.3)% |

0.06 (0.0)% |

5.8 (1.3) |

9.6 (1.5) |

3.2 (0.9) |

| ≥14 mm |

8.0 (0.8)% |

5.0 (0.7)% |

2.7 (0.5)% |

0.8 (0.2) |

0.2 (0.0)% |

0.05(0.0)% |

6.2 (0.7) |

7.3 (0.8) |

3.8 (0.6) |

| p-value |

0.799 |

0.575 |

0.370 |

0.023 |

0.006 |

0.165 |

0.520 |

0.075 |

0.700 |

| Base |

<10 mm |

7.6 (0.4)% |

4.5 (0.4)% |

2.5 (0.0)% |

1.1 (0.6)% |

0.3 (0.2)% |

0.07 (0.0)% |

8.5 (2.1) |

11.0 (1.0) |

3.7 (2.1) |

| 10-14 mm |

8.4 (1.0)% |

6.1 (0.9)% |

3.0 (0.6)% |

0.8 (0.5)% |

0.5 (0.5)% |

0.02 (0.0)% |

6.8 (2.2) |

9.3 (0.9) |

4.5 (0.9) |

| ≥14 mm |

8.0 (1.0)% |

5.2 (0.8)% |

3.0 (0.6)% |

1.2 (0.3)% |

0.5 (0.2)% |

0.1 (0.1) |

6.3 (1.0) |

7.0 (0.8) |

3.8 (1.0) |

| |

p-value |

0.987 |

0.942 |

0.803 |

0.569 |

0.811 |

0.539 |

0.397 |

0.025 |

0.813 |

Bladder Dmean was not found to be associated with apex and midgland spacing (p = 0.946 and 0.075). However, higher separation at the base was found to be associated with a significant reduction in bladder Dmean (p =0.025). Penile bulb Dmean showed a pattern similar to the rectum, with significantly lower dose at the apex as separation increased (p< 0.001), and no significant differences at the midgland or base (p = 0.700 and 0.813).

Spacer Stability

The mean spacer balloon volume was 15.3 ± 0.37 cc at simulation and 14.7 ± 0.37 cc at the end of treatment (3.9% decrease, p = 0.09). The mean prostate-rectum distance, measured at a consistent central axial level through the prostate, was 1.67 ± 0.04 cm at simulation and 1.63 ± 0.04 cm at the end of treatment (2.4% decrease, p = 0.3).

Safety

Among 33 treated patients, no acute GI or rectal toxicities were observed, and no spacer- or procedure-related adverse events were reported. Acute grade 1 GU toxicities occurred in 3 patients (9%), consisting of mild, transient urinary symptoms such as dysuria or nocturia, all resolving to baseline by the three-month follow-up.

Late GU toxicities were observed in 2 patients (6%). One patient with history of transurethral resection of a bladder tumor (TURBT) experienced grade 1 dysuria at eight months post radiation therapy (RT), and one patient experienced urinary leakage at four months post RT and was diagnosed with grade 2 radiation cystitis at six months.

Discussion

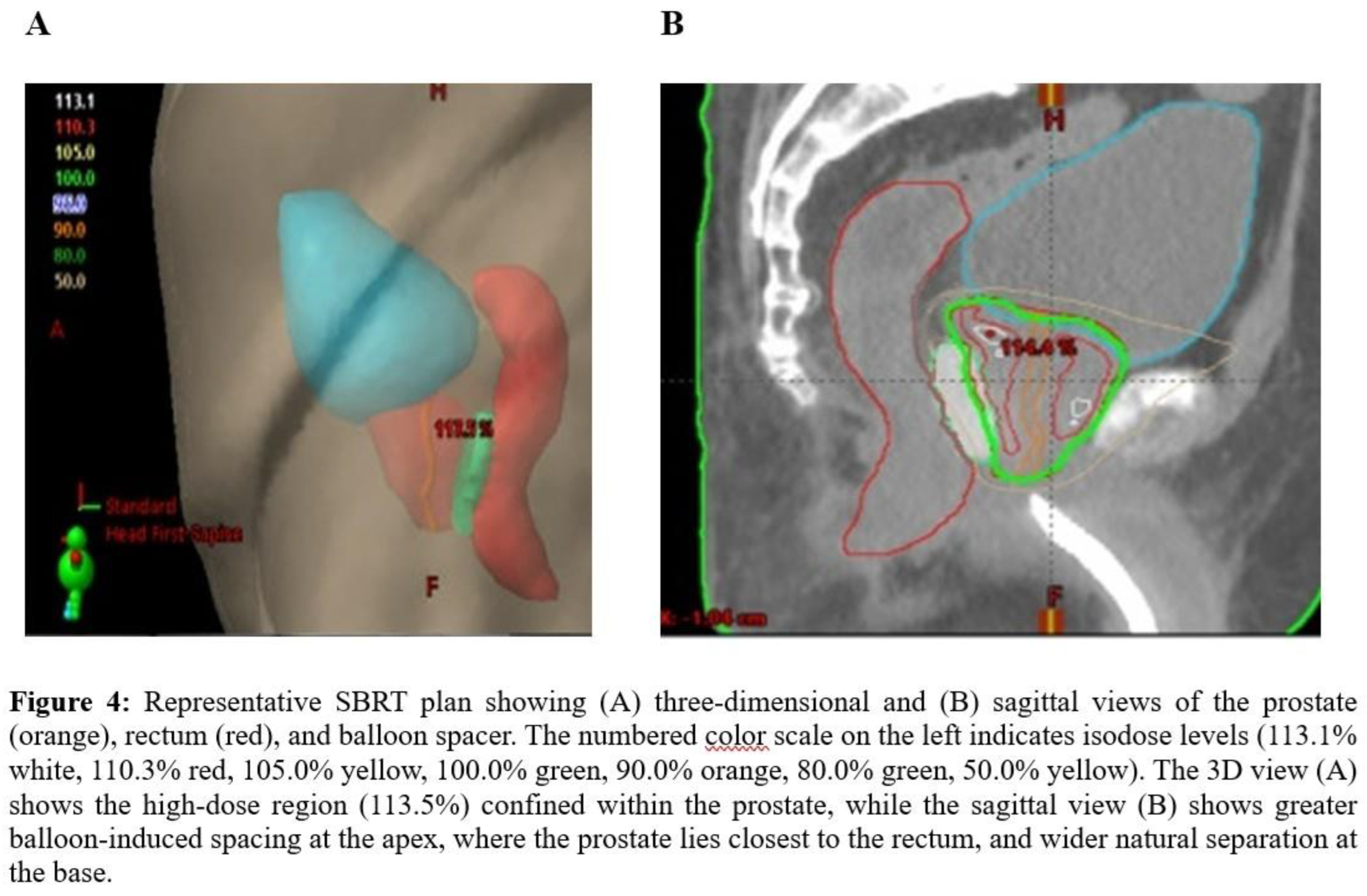

This report is the first to evaluate the utilization of the balloon rectal spacer in the SBRT setting and its benefit on rectal dose distribution at the anatomical levels of the prostate’s apex, base, and mid-gland. Since the rectal wall lies directly behind the prostate and is separated only by the thin Denonvilliers’ fascia, the treatment target frequently abuts the anterior rectal surface (14), making the apex a critical region for rectal protection. In our study, greater apical separation corresponded with lower rectal dose. Analysis of Dmean rectum and Dmean bladder showed that separation at the apex and midgland was significantly associated with rectal dose reduction, whereas separation at the base did not reach significance. In contrast, bladder dose was not associated with apex distance but declined with increasing separation at the midgland and base. These findings support an anatomical level dependency effect, with apical separation as the principal determinant of rectal protection, and more cranial, a base directed separation contributing more to bladder sparing. Moreover, since the apical spacing is increased with the use of the balloon, this separation may shift the high-dose region away from the penile bulb which is located inferiorly and slightly posterior to the prostatic apex (with its superior surface adjacent to the inferior aspect of the planning target volume) (15), (16). Hence, this separation provides an effective protection from the SBRT steep dose gradient, resulting in penile bulb Dmean reduction.

Our results extend the geometric principles described by King et al. (10). In their secondary analysis of a randomized hyaluronic-acid spacer trial, apical spacing was identified as the only post-implant characteristic independently associated with rectal V30 and early bowel quality-of-life outcomes, and patients with apical spacing at least 10 mm had fewer bowel declines than those with spacing below 10 mm. In our SBRT cohort, stratification into <10 mm, 10-14 mm, and ≥14 mm showed a progressive reduction in rectal dose at the apex and midgland, both in Dmean and across the rectal DVH, whereas DVH at the base were largely overlapping. These findings support the ≥10 mm apical threshold reported by King et al and indicate that additional, though more modest, rectal dose reduction can be achieved with apical spacing beyond 14 mm, while base spacing has limited influence. Consistent with this apical concept, Narukawa et al. (17) demonstrated in proton beam therapy that achieving greater apex separation (≥7.5 mm) with a modified hydrogel technique produced stepwise reductions in rectal V30-60 and lower rates of GI toxicity. Together, these data from SBRT, IMRT, and proton therapy support the value of apical spacing in rectal protection, while suggesting that the contribution of base separation and bladder and penile bulb dose modulation warrants further prospective study to be fully established.

Anatomical and pathological evidence further support the importance of apical spacing (18), (9), (19). Multiparametric MRI and whole-mount studies show that dominant intraprostatic lesions commonly arise in the peripheral zone with posterior-inferior extension toward the apex, which is also a frequent site of local recurrence (20), (21). The association between the rectal displacement at the prostate base and the radiation dose was less seen and can be explained anatomically as the seminal vesicles naturally increase the distance between the prostate and rectum (

Figure 4). This diminishes the added benefit of further rectal displacement (22).

Adequate target coverage is critical for tumor control. When SBRT, techniques are utilized without rectal spacing, the radiation dose is often limited, when prioritizing OARs. This may necessitate reducing the posterior treatment margin at the apex, in order to meet the rectal constraints, and minimize the rectal radiation exposure (23). This balance between treatment efficiency and safe radiation delivery without increasing the risk to nearby healthy tissues and side effects is further vital in dose-escalated RT such as with a simultaneous integrated boost(SIB). In our cohort, no replanning was required. With the utilization of the balloon, the temporary expansion of the prostate-rectal distance remained stable with a decrease of 2.4% mm and 3.6% cc in the perirectal distance at mid-gland and the balloon volume, respectively, as measured between simulation and treatment completion. These findings and are aligned with previous studies (5), (24), (25). Importantly, the displacement achieved at implantation was maintained across all fractions, enabling the preservation of the full target margin while keeping rectal exposure within tolerance. This geometric consistency is particularly important in SBRT, where only a few high-dose fractions determine total biological effect (26). While rectal spacers are designed to physically push the rectum away from the prostate, the created space may vary and is often affected by the spacer size, volume, its final position and distribution. Patient anatomy, and particularly the length of the prostate (10), (12), (27) can often effect the spacer quality and its ability to optimally achieve rectal protection. Understanding this spatial dependency is essential for optimizing dose delivery, to minimize rectal toxicity and any potential harm to proximal regions to the PTV. This is further enhanced while applying radiotherapy by means of SBRT which delivers extremely high radiation dose per fraction with steep dose gradients (28).

We found the balloon use to be safe. There were no procedural complications with an overall favorable treatment tolerance, which is in line with previous reports (6), (29). No GI or rectal toxicities were observed. GU events occurred infrequently and were mild, and self-limiting. These outcomes are similar to published SBRT series employing hydrogel spacers, where late grade ≥ 2 GI toxicity has been reported in 1-4% of patients (30), (31).

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, single-institution cohort, and modest sample size. Nevertheless, the consistent geometric-dosimetric associations observed across multiple anatomical levels strengthen the conclusion that spatial separation at the apex and midgland is the dominant determinant of rectal dose sparing in prostate SBRT. Functional and long-term quality of life assessments are needed for further evaluation of rectal protection at apex of the prostate level.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the relationship between the perirectal separation and dose sparing to organs at risk in patient undergoing SBRT. We found than an increased apical spacing, is significantly associated with lower rectal and penile bulb dose, consistent with the geometric proximity and anatomical relationship between the apex, rectum, and penile bulb. Midgland separation contributed to additional rectal dose sparing, whereas base-directed spacing was more closely related to changes in bladder dose. The anatomic relationship to increased rectal spacing at the base and its association with bladder dose reduction will be investigated subsequently. Overall, the spacer produced favorable mean dose distributions to rectum, bladder, and penile bulb where adequate separation was achieved across the entire gland length, but particularly at the apex and midgland. These findings support careful attention to spacer position and apical coverage in SBRT planning and justify further study of their relationship with gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and sexual clinical outcomes and patient’s quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, study design, supervision, and writing, original draft preparation and review and editing, E.S.; patient treatment and clinical data acquisition, E.S. and V.C.N.; treatment planning support, dosimetry, and medical physics oversight, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Astera Cancer Care / Princeton Radiation Oncology Center. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of de-identified patient data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to patient privacy and institutional restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ultra-hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the HYPO-RT-PC randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Widmark A, Gunnlaugsson A, Beckman L, Thellenberg-Karlsson C, Hoyer M, Lagerlund M, Kindblom J, Ginman C, Johansson B, Björnlinger K, Seke M, Agrup M, Fransson P, Tavelin B, Norman D, Zackrisson B, Anderson H, Kjellén E, Franzén L, Nilsson P. s.l. : Lancet., 2019, Vols. Aug 3;394(10196):385-395. [CrossRef]

- Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO Guideline, Part I: Introduction, Risk Assessment, Staging, and Risk-Based Management. Eastham JA, Auffenberg GB, Barocas DA, Chou R, Crispino T, Davis JW, Eggener S, Horwitz EM, Kane CJ, Kirkby E, Lin DW, McBride SM, Morgans AK, Pierorazio PM, Rodrigues G, Wong WW, Boorjian SA. s.l. : J Urol. , 2022, Vols. Jul;208(1):10-18.

- Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: An ASTRO, ASCO, and AUA Evidence-Based Guideline. . Morgan SC, Hoffman K, Loblaw DA, Buyyounouski MK, Patton C, Barocas D, Bentzen S, Chang M, Efstathiou J, Greany P, Halvorsen P, Koontz BF, Lawton C, Leyrer CM, Lin D, Ray M, Sandler H. s.l. : J Clin Oncol., 2018, Vol. Oct 11;36(34).

- Optimization of radiation therapy techniques for prostate cancer with prostate-rectum spacers: a systematic review. . Mok G, Benz E, Vallee JP, Miralbell R, Zilli T. s.l. : Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. , 2014, Vols. Oct 1;90(2):278-88.

- Prospective, Randomized Controlled Pivotal Trial of Biodegradable Balloon Rectal Spacer for Prostate Radiation Therapy. Song D, Dabkowski M, Costa P, Nurani R, Kos M, Vanneste B, Magel D, Sapir E, Zimberg S, Boychak O, Soffen E, Alhasso A, Tokita K, Wang D, Symon Z, Hudes R. s.l. : Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2024, Vols. Dec 1;120(5):1410-1420. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P; Vale, J; Fonseca, G; Costa, A; Kos, M. Use of rectal balloon spacer in patients with localized prostate cancer receiving external beam radiotherapy. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2024, 29, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perirectal spacers in radiotherapy for prostate cancer - a systematic review and meta-analysis. . Miszczyk M, Stando R, Francolini G, Zamboglou C, Cadenar A, Suleja A, Fazekas T, Matsukawa A, Tsuboi I, Przydacz M, Leapman MS, Rajwa P, Supiot S, Shariat SF. s.l. : Contemp Oncol (Pozn), 2025, Vols. 29(1):36-44.

- Mariados, N; Sylvester, J; Shah, D; Karsh, L; Hudes, R; Beyer, D; Kurtzman, S; Bogart, J; Hsi, RA; Kos, M; Ellis, R; Logsdon, M; Zimberg, S; Forsythe, K; Zhang, H; Soffen, E; Francke, P; Mantz, C; Rossi, P; DeWeese, T; Hamstra, DA; Bosch, W; Gay, H; Michalski, J. Hydrogel Spacer Prospective Multicenter Randomized Controlled Pivotal Trial: Dosimetric and Clinical Effects of Perirectal Spacer Application in Men Undergoing Prostate Image Guided Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015, 92(5), 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uno, M; Tamaki, Y; Nonomura, K; Yamamori, U; Burioka, H; Nagano, N; Ue, A; Sonoyama, Y; Yoshida, R; Kitajima, K; Wada, K. Effect of hydrogel-spacer implantation and uneven positioning on rectal dose in intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Cancer 2025, 16(14), 4187–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaluating the Quality-of-Life Effect of Apical Spacing with Hyaluronic Acid Prior to Hypofractionated Prostate Radiation Therapy: A Secondary Analysis. . King MT, Svatos M, Chell EW, Pigrish V, Miller K, Low DA, Orio PF 3rd. s.l. : Pract Radiat Oncol., 2024, Vols. May-Jun;14(3):e214-e219.

- NCCN Guidelines Insights: Prostate Cancer, Version 1.2021. . Schaeffer E, Srinivas S, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, Bekelman JE, Cheng H, D’Amico AV, Davis BJ, Desai N, Dorff T, Eastham JA, Farrington TA, Gao X, Horwitz EM, Ippolito JE, Kuettel MR, Lang JM, McKay R, McKenney J, Netto G, Penson DF, Pow-Sang JM, Reit. s.l. : J Natl Compr Canc Netw., 2021, Vols. Feb 2;19(2):134-143. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, CE; Folkert, MR; Lobaugh, S; Desai, NB; Kollmeier, MA; Gorovets, D; McBride, SM; Timmerman, RD; Zhang, Z; Zelefsky, MJ. Quality Metric to Assess Adequacy of Hydrogel Rectal Spacer Placement for Prostate Radiation Therapy and Association of Metric Score With Rectal Toxicity Outcomes. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023, 8(4), 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariados, NF; Orio, PF, 3rd; Schiffman, Z; Van, TJ; Engelman, A; Nurani, R; Kurtzman, SM; Lopez, E; Chao, M; Boike, TP; Martinez, AA; Gejerman, G; Lederer, J; Sylvester, JE; Bell, G; Rivera, D; Shore, N; Miller, K; Sinayuk, B; Steinberg, ML; Low, DA; Kishan, AU; King, MT. Hyaluronic Acid Spacer for Hypofractionated Prostate Radiation Therapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9(4), 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, LM; Lubich, L; Chiru, P; Ignacio, L; Sweeney, P; Chen, GT. Localization of the prostatic apex for radiotherapy planning: a comparison of two techniques. Br J Radiol. 1996, 69(825), 821–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasseray, M; Dissaux, G; Bourbonne, V; Boussion, N; Goasduff, G; Malloreau, J; Malhaire, JP; Fournier, G; Tissot, V; Pradier, O; Valeri, A; Schick, U. Dose to the penile bulb and individual patient anatomy are predictive of erectile dysfunction in men treated with 125I low dose rate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58(7), 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, JY; Spratt, DE; Liss, AL; McLaughlin, PW. Vessel-sparing radiation and functional anatomy-based preservation for erectile function after prostate radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17(5), e198-208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narukawa, T; Aibe, N; Tsujimoto, M; Shiraishi, T; Kimoto, T; Suzuki, G; Ueda, T; Fujihara, A; Yamazaki, H; Ukimura, O. Increasing rectum-prostate distance using a hydrogel spacer to reduce radiation exposure during proton beam therapy for prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2023, 13(1), 18319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H; Eriguchi, T; Tanaka, T; Ogata, T; Osaki, N; Suzuki, H; Kosugi, M; Kumabe, A; Sato, K; Ishida, M. An optimal method of hydrogel spacer insertion for stereotactic body radiation therapy of prostate cancer. Jpn J Radiol. 2024, 42(4), 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owa, S; Sasaki, T; Taniguchi, A; Omori, K; Nishikawa, T; Kato, M; Higashi, S; Sugino, Y; Toyomasu, Y; Takada, A; Nishikawa, K; Nomoto, Y; Inoue, T. Patients with a Short Distance Between the Prostate and the Rectum Are Appropriate Candidates for Hydrogel Spacer Placement to Prevent Short-Term Rectal Hemorrhage After External-Beam Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2025, 32(7), 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Z; Yuan, R; Yan, W; Zhou, Y; Zhou, Z; Ren, M; Xiao, Y; Huang, H; Huang, Y. Analysis of the origin and invasion of prostate cancer from autopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens. Transl Cancer Res. 2024, 13(2), 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y; Fukaya, K; Haraoka, M; Kitamura, K; Toyonaga, Y; Tanaka, M; Horie, S. Analysis of prostate cancer localization toward improved diagnostic accuracy of transperineal prostate biopsy. Prostate Int. 2014, 2, 114–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X; Gao, XS; Asaumi, J; Zhang, M; Li, HZ; Ma, MW; Zhao, B; Li, FY; Wang, D. Optimal contouring of seminal vesicle for definitive radiotherapy of localized prostate cancer: comparison between EORTC prostate cancer radiotherapy guideline, RTOG0815 protocol and actual anatomy. Radiat Oncol. 2014, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, J; Jameson, MG; Rivest-Henault, D; Keats, S; Rai, R; Arumugam, S; Wilton, L; Ngo, D; Liney, G; Moses, D; Dowling, J; Martin, J; Sidhom, M. Reduced motion and improved rectal dosimetry through endorectal immobilization for prostate stereotactic body radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2019, 92(1098), 20190056. [Google Scholar]

- Latorzeff, I; Bruguière, E; Bogart, E; Le Deley, MC; Lartigau, E; Marre, D; Pasquier, D. Use of a Biodegradable, Contrast-Filled Rectal Spacer Balloon in Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer Patients: Dosimetric Gains in the BioPro-RCMI-1505 Study. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 701998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchert, C; Gez, E; Bohlen, G; Scarzello, G; Koziol, I; Anscher, M; Cytron, S; Paz, A; Torre, T; Bassignani, M; Dal Moro, F; Jocham, D; Yosef, RB; Corn, BW; Kovács, G. Interstitial biodegradable balloon for reduced rectal dose during prostate radiotherapy: results of a virtual planning investigation based on the pre- and post-implant imaging data of an international multicenter study. Radiother Oncol. 2013, 106(2), 210–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, WC; Silva, J; Hartman, HE; Dess, RT; Kishan, AU; Beeler, WH; Gharzai, LA; Jaworski, EM; Mehra, R; Hearn, JWD; Morgan, TM; Salami, SS; Cooperberg, MR; Mahal, BA; Soni, PD; Kaffenberger, S; Nguyen, PL; Desai, N; Feng, FY; Zumsteg, ZS; Spratt, DE. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 6,000 Patients Treated On Prospective Studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019, 104(4), 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer-Valuck, BW; Chundury, A; Gay, H; Bosch, W. Hydrogel spacer distribution within the perirectal space in patients undergoing radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Impact of spacer symmetry on rectal dose reduction and the clinical consequences of hydrogel infiltration into the rectal wall. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017, 7(3), 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kuncman, Ł; la Pinta, C; Milder, MTW; Romero, AM; Guckenberger, M; Franzese, C; Scorsetti, M; Bruc, B; Verellen, D; Tanadini-Lang, S. Definition and requirements for stereotactic radiotherapy: a systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2025, 211, 111107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, M; Nurani, R; Costa, P; Dabkowski, M; da Silva, JVF; Zimberg, S; Keane. Multicenter, dual fractionation scheme, single core lab comparison of rectal volume dose reduction following injection of two biodegradable perirectal spacers. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2023, 24(10), e14086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, HA; Pinkawa, M; Peedell, C; Bhattacharyya, SK; Woodward, E; Miller, LE. SpaceOAR hydrogel spacer injection prior to stereotactic body radiation therapy for men with localized prostate cancer: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100(49), e28111. [Google Scholar]

- Rectal Radiation Dose and Clinical Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients Treated With Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy With and Without Hydrogel. Kundu P, Lin EY, Yoon SM, Parikh NR, Ruan D, Kishan AU, Lee A, Steinberg ML, Chang AJ. s.l. : Front Oncol, 2022, Vol. Mar 8;12:853246.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |