1. Introduction

Although gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) have been widely used in contrast-enhanced MRI examinations, safety concerns–particularly related to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF)–have been raised regarding their use in patients with renal impairment [

1]. Various GBCAs differ in chelate stability, molecular structure, and physicochemical properties, which affect gadolinium retention and excretion from the body [

2]. Current clinical practice and international guidelines preferentially recommend macrocyclic GBCAs due to their higher kinetic stability and low risk of NSF [

3]. Although gadoxetate disodium, a more recently introduced linear ionic GBCA, is classified as a group III (likely very low risk but insufficient confirmatory evidence) by the American College of Radiology (ACR), several recent studies have reported that gadoxetate disodium is safe for NSF in patients with renal impairment [

4,

5,

6].

If gadolinium is not adequately excreted and consequently retained in the body, it can accumulate in skin tissue, which has been associated with NSF, as well as deposition in brain tissues manifesting as T1 hyperintensity in the globus pallidus and dentate nucleus. In patients with renal impairment, prolonged gadolinium retention may increase the likelihood of dissociation of free Gd3+ from its chelate, which may increase the risk of NSF and brain tissue deposition [

7]. Therefore, it is important to rapidly eliminate gadolinium from the body and minimize its retention in these patients.

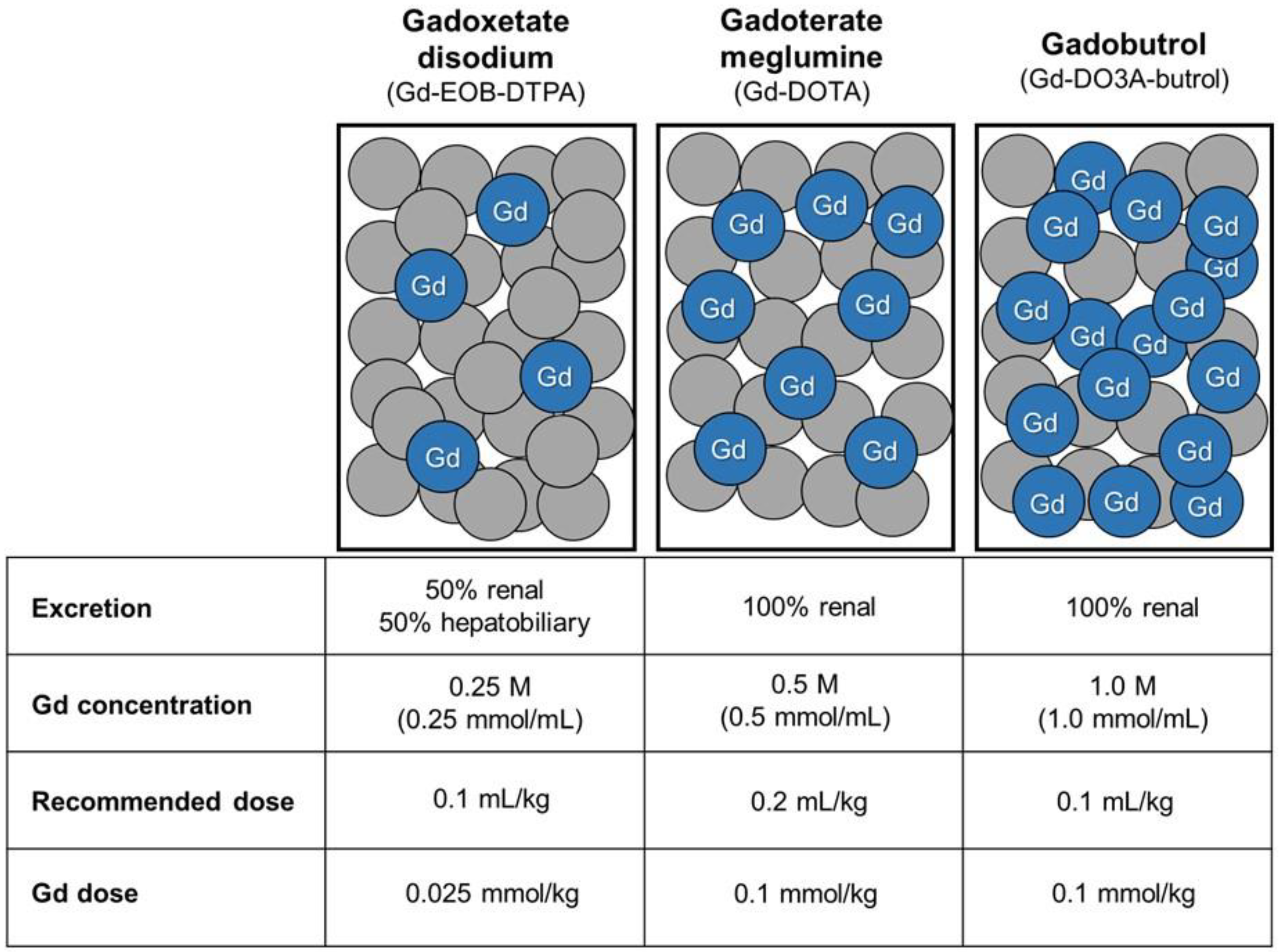

Most GBCAs are eliminated through renal excretion via glomerular filtration, but some GBCAs have a dual excretion pathway in which they are also excreted through the hepatobiliary system [

3]. Gadoxetate disodium is a hepatocyte-specific GBCA, approximately 50% of which is taken up by functioning hepatocytes and excreted into bile [

3,

8]. Previous experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that these dual excretion pathways may facilitate compensatory elimination in the setting of renal dysfunction, potentially reducing gadolinium retention in patients with impaired renal function [

9,

10,

11]. Additionally, because the gadolinium concentration of gadoxetate disodium is lower (0.25 M) than that of other GBCAs (0.5 or 1.0 M), the total molar dose of gadolinium administered to the patient is lower when the same volume is injected.

Our institution developed a tailored GBCA administration protocol that considers excretion pathways and gadolinium concentrations for patients with renal impairment. The institutional protocol was designed to prioritize the use of gadoxetate disodium, a GBCA with dual excretion pathway and lower gadolinium concentration, for more efficient excretion in patients with renal impairment and normal serum bilirubin levels.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the long-term safety and clinical outcomes of this institutional protocol. We investigated whether this tailored approach, implemented over an 8-year period, effectively prevents the occurrence of NSF and gadolinium deposition in brain tissue in patients with renal impairment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

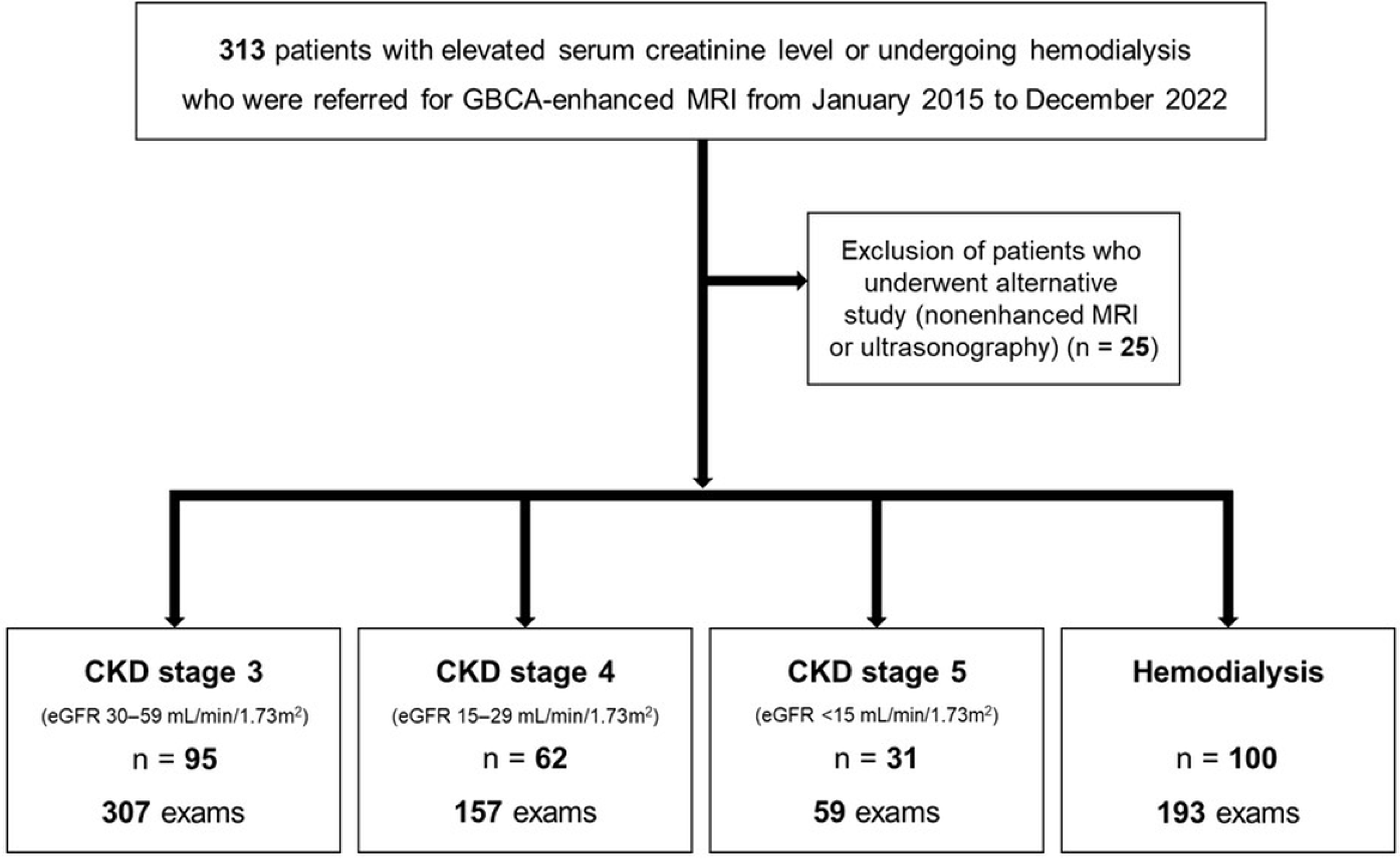

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board, and the requirement for informed consent was waived. Since 2015, all GBCA-enhanced MRI examinations at our institution have been performed in accordance with a tailored GBCA administration protocol developed for patients with renal impairment or undergoing hemodialysis. Patients with elevated serum creatinine or undergoing hemodialysis who were referred for GBCA-enhanced MRI were consecutively recruited from January 2015 to December 2022 (

Figure 1).

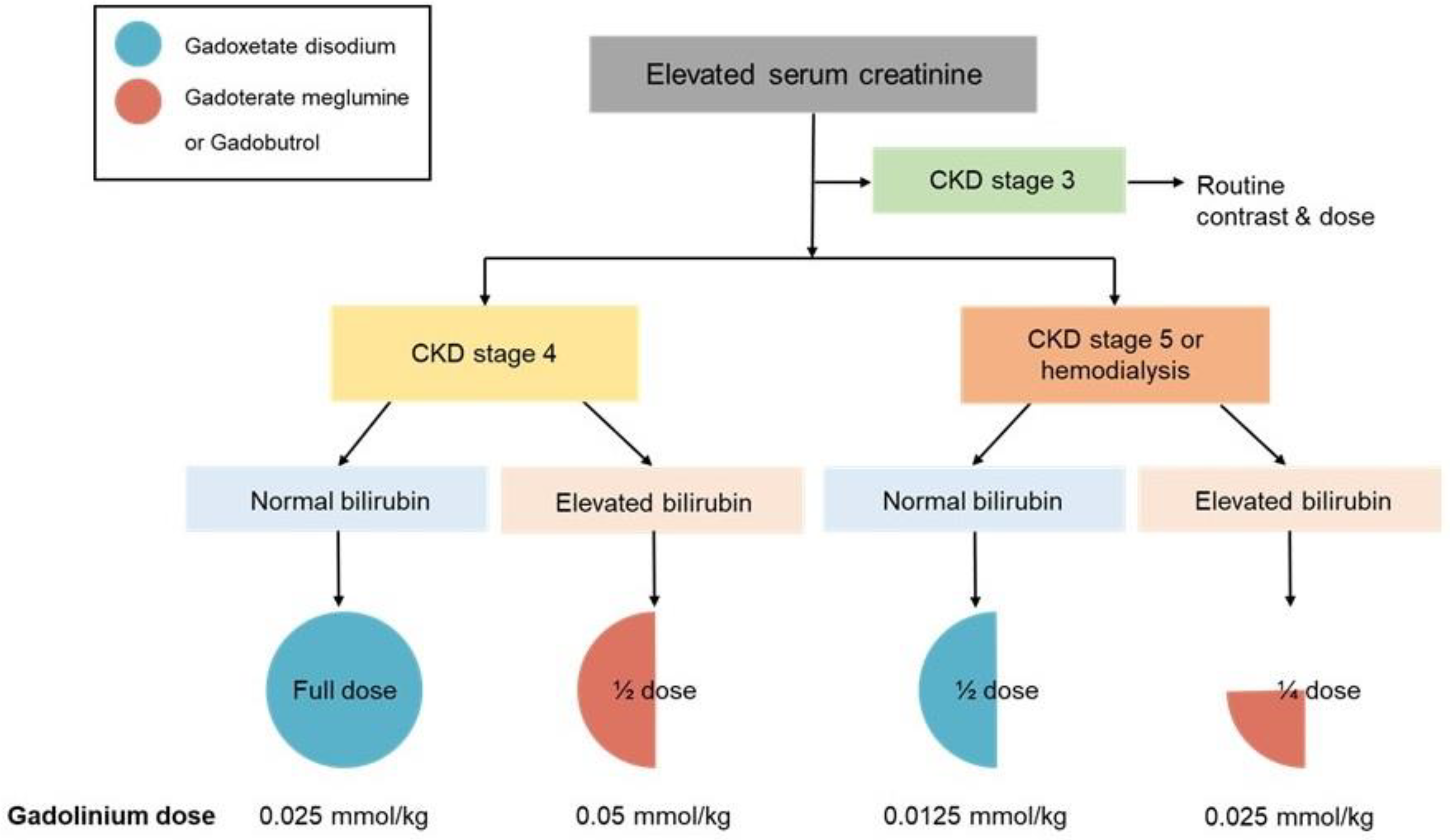

The institutional protocol recommended specific GBCAs at an adjusted dose based on the chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage and serum bilirubin levels. For patients with CKD stage 3, full-dose GBCAs were administered as in patients with normal renal function. For patients with CKD stage 4, a full dose of gadoxetate disodium was recommended in patients with normal serum bilirubin levels, whereas a half-dose of gadoterate meglumine or gadobutrol was administered in patients with elevated serum bilirubin levels. For patients with CKD stage 5 or undergoing hemodialysis, a half-dose of gadoxetate disodium was recommended in patients with normal serum bilirubin levels, while a quarter-dose of gadoterate meglumine or gadobutrol was used in those with elevated serum bilirubin levels (

Figure 2). Because gadoxetate disodium has a lower molar concentration (0.25 M) than macrocyclic GBCAs, including gadoterate meglumine (0.5 M) and gadobutrol (1.0 M), a relatively higher volumetric dose of gadoxetate disodium was administered in patients with normal bilirubin levels; however, the total administered gadolinium dose remained lower (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

All patients underwent serum creatinine and bilirubin testing within three days prior to MRI examination. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation using the serum creatinine level [

12]. CKD stages were defined as follows: stage 1, eGFR >90 mL/min/1.73m2; stage 2, eGFR 60–89 mL/min/1.73m2; stage 3, eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73m2; stage 4, eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73m2; and stage 5, eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2. Because eGFR is not a reliable indicator of renal function in patients undergoing hemodialysis, eGFR was not used for staging in these patients. The follow-up period was determined as the interval between the date of the GBCA-enhanced MRI examination and the date of the last outpatient visit or hospitalization.

2.2. Clinical Outcomes

To identify NSF cases, we conducted a comprehensive review of the patients’ electronic medical records. The diagnosis of NSF was based on the clinicopathological scoring system outlined by Girardi et al. [

13]. Patients were considered positive for NSF only if evaluated by a board-certified dermatologist and confirmed by deep skin biopsy. Cases of NSF mentioned only as a differential diagnosis or probable diagnosis without histological confirmation were excluded.

Gadolinium deposition in brain tissues was evaluated in patients who (1) underwent brain MRI examinations both before and after GBCA-enhanced MRI or (2) underwent brain MRI as the initial GBCA-enhanced study and had subsequent follow-up brain MRIs. T1 hyperintensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus was evaluated on pre-contrast images. Because T1 hyperintensity in these regions may be observed in various other clinical conditions [

7], cases in which only post-GBCA brain MRI was available or gadolinium deposition could not be reliably identified were excluded from the brain deposition analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation with range, and categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage. The risk of NSF in patients with renal impairment was calculated per patient and examination, with the upper bound of 95% confidence interval (CI) determined using the Wilson score without continuity correction [

14].

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 313 patients were referred for GBCA-enhanced MRI examinations. Among them, 288 patients underwent 716 GBCA-enhanced MRI examinations in accordance with our institutional protocol, while 25 patients underwent alternative imaging studies, including nonenhanced MRI or ultrasonography (

Figure 1). The mean age of the 288 patients at the time of GBCA-enhanced MRI was 64.6 ± 11.7 years (range, 29–93 years), and 187 (64.9%) were men. Baseline demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1. The cohort included 95 patients with CKD stage 3, 62 with CKD stage 4, 31 with CKD stage 5, and 100 patients undergoing hemodialysis (

Figure 1). Among the 288 patients, 149 (51.7%) patients underwent more than one GBCA-enhanced MRI examination in accordance with the tailored GBCA administration protocol during the study period (

Table 2). Sixty patients (20.8%) had undergone GBCA-enhanced MRI examinations prior to the implementation of this protocol. During the study period, the mean cumulative gadolinium dose was 0.070 ± 0.093 mmol/kg (range, 0.0125–0.9 mmol/kg) for the entire cohort and 0.025 ± 0.023 mmol/kg (range, 0.0125–0.1625 mmol/kg) specifically for patients with CKD5 or undergoing hemodialysis.

In patients with CKD stage 4, 152 full-dose gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MRI examinations and 5 half-dose gadoterate meglumine or gadobutrol-enhanced MRI examinations were performed. In patients with CKD stage 5 or those undergoing hemodialysis, 242 half-dose gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MRI examinations and 10 quarter-dose gadoterate meglumine or gadobutrol-enhanced MRI examinations were performed.

Table 3 summarizes the distribution of GBCAs with adjusted doses based on renal function and serum bilirubin levels across different anatomical regions.

The mean follow-up period for all GBCA-enhanced MRI examinations was 27.5 ± 31.0 months (range, 0–120 months).

3.2. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF)

No cases of NSF were identified among patients with renal impairment who underwent MRI following our institutional protocol. Consequently, the overall risk of NSF in this population was 0% (95% CI, 0%–1.32 %). Among patients with CKD stages 4, 5, and undergoing hemodialysis, the upper bound of 95% CI was 1.95 % per patient (n = 193) and 0.93 % per examination (n = 409).

3.3. Gadolinium Deposition in Brain Tissue

Assessment of gadolinium deposition in brain tissue was performed in 26 patients (15 with CKD stage 5 or undergoing hemodialysis, 4 with CKD stage 4, and 7 with CKD stage 3) who had available pre- and post-GBCA brain MRI or follow-up imaging. These patients underwent an average of 3.9 ± 1.8 GBCA-enhanced MRI examinations, and the mean interval between the GBCA-enhanced MRI and the follow-up brain MRI was 27.8 ± 17.1 months (range, 12–61 months). No cases demonstrated new T1 hyperintensity in the globus pallidus or dentate nucleus on follow-up brain MRI compared with baseline examinations.

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated the long-term clinical safety of a tailored GBCA administration protocol that considers excretion pathways and gadolinium concentrations in patients with renal impairment. Over an 8-year period, no cases of NSF were identified among 288 patients with renal impairment, including 131 patients with CKD stage 5 or undergoing hemodialysis. In addition, no evidence of gadolinium deposition in brain tissues was observed during a mean follow-up of 27.8 months.

GBCAs are administered in a chelated form to reduce the toxicity of free gadolinium ions [

15]. The stability of the chelate and pharmacokinetic properties influences gadolinium retention and elimination. In patients with normal renal function, most administered gadolinium is rapidly eliminated. However, in patients with renal impairment, reduced clearance may result in prolonged retention and increased susceptibility to tissue deposition [

16,

17]. Therefore, strategies that facilitate alternative excretion pathways and minimize total gadolinium exposure are particularly important in this patient population. Our GBCA administration protocol was designed to address these concerns by tailoring GBCA and dosing based on renal function and serum bilirubin levels.

Although most GBCAs are eliminated through renal excretion, certain agents, including gadoxetate disodium and gadobenate dimeglumine, exhibit an additional hepatobiliary excretion pathway [

8]. The physiological significance of this alternative pathway becomes particularly evident when renal function is compromised. Experimental studies using animal models with impaired renal or hepatic function have demonstrated compensatory excretion of these agents through alternative pathways, resulting in more rapid elimination compared with purely renally excreted GBCAs. Mühler et al. reported that in animals with renal vessel ligation, gadoxetate disodium showed significantly greater elimination and lower retention 8 hours after injection compared with gadopentetate dimeglumine (1.3% vs. 96.3% retention) [

9]. Similarly, Kirchin et al. confirmed that biliary excretion increases proportionally when renal pathways are occluded [

10]. Complementing these experimental observations, a clinical pharmacokinetic study by Gschwend et al. have shown that hepatobiliary excretion of gadoxetate disodium may partially compensate for impaired renal clearance in patients with mild to moderate renal impairment [

11]. Collectively, based on these findings, we developed our institutional protocol to prioritize these dual excretion pathway agents according to the serum bilirubin levels in patients with renal impairment. By strategically utilizing the hepatobiliary excretion pathway, this tailored GBCA administration protocol aims to facilitate gadolinium elimination and minimize systemic retention in patients with renal impairment.

Although gadoxetate disodium is categorized as a group III agent (likely very low risk but with limited confirmatory evidence) by the ACR and as an intermediate-risk agent by the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR), clinical evidence regarding its safety in patients with renal impairment is steadily accumulating [

4,

5,

6,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Lauenstein et al. found no NSF cases in a prospective study of 278 patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment [

18], and Starekova et al. demonstrated similar safety outcomes even with double-dose administrations in 183 patients with severe renal impairment [

4]. The absence of NSF observed in the present study is consistent with these previous findings and further supports the accumulating data on the safety of gadoxetate disodium in patients with renal impairment. The present study differs from previous studies in that it evaluated a tailored GBCA administration protocol considering excretion pathways and gadolinium concentrations.

Another safety concern associated with GBCA administration is gadolinium deposition in brain tissues. Since the initial report by Kanda et al. [

23], several studies have demonstrated an association between repeated GBCA administration and increased T1 hyperintensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus. These findings have been consistently reported; however, their clinical significance remains unclear, and no clear neurological and cognitive sequelae have been identified to date [

7].

There have been several limitations in this study. First, this study was a retrospective study, with no direct comparison with a control group receiving GBCAs without dose adjustment. However, when our institutional protocol was developed 10 years ago, it would have raised ethical concerns, given limited safety evidence at the time. In addition, the primary aim of this study was not comparative efficacy but the evaluation of long-term safety outcomes following implementation of a tailored GBCA administration protocol in the actual clinical setting. Second, the number of patients included the assessment of gadolinium deposition in brain tissue was relatively small. Although a substantial number of patients with renal impairment underwent brain MRI, this study analyzed only patients who had available brain MRI examinations both before and after GBCA exposure in accordance with our institutional protocol. This strict inclusion criteria were necessary to ensure clear longitudinal comparisons and to exclude pre-existing T1 hyperintensities that may also occur in various other clinical conditions. Third, although gadoxetate disodium is primarily indicated as a hepatobiliary-specific agent, its clinical utility was extended to non-hepatobiliary imaging–including brain and musculoskeletal MRI–within our institutional protocol to prioritize patient safety. In our study, both the image quality and contrast enhancement of these areas were clinically acceptable and sufficient for reliable radiological interpretation. Meanwhile, the clinical feasibility of adjusted GBCA dose in patients with renal impairment has been demonstrated in previous studies [

21,

24]. Notably, previous studies have shown that reduced amount of dual excretion contrast agents, including half-dose of gadoxetate disodium and quarter dose of gadobenate dimeglumine, can be used in patients with renal impairment without compromising diagnostic image quality [

21,

24]. Finally, delayed onset of NSF has been reported 10 years after GBCA exposure [

25,

26], so cases NSF with delayed onset may have been missed; however, such occurrences considered very rare, and the relatively long follow-up period of this study provides relatively high confidence in safety.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that a tailored GBCA administration protocol can be associated with favorable long-term safety outcomes in patients with renal impairment. Over an 8-year period, no cases of NSF and evidence of gadolinium deposition in brain tissues were observed. Therefore, our institutional GBCA administration protocol, which strategically considers excretion pathways and gadolinium concentrations to facilitate rapid elimination and minimize retention of gadolinium, may contribute to safer clinical management of patients with renal impairment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H.L. and J.W.K.; Methodology, C.H.L. and J.W.K.; Formal analysis, J.W.K.; Investigation, J.W.K.; Resources, C.H.L.; Data curation, J.W.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.W.K.; Writing—review and editing, C.H.L.; Visualization, J.W.K.; Supervision, C.H.L.; Project administration, C.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Guro Hospital (protocol code 2022GR0430 and date of approval: 19 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBCA |

Gadolinium-based contrast agent |

| NSF |

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis |

| ACR |

American college of radiology |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| eGFR |

Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| ESUR |

European Society of Urogenital Radiology |

References

- Matsumura, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Shimada, F.; et al. Safety of gadopentetate dimeglumine after 120 million administrations over 25 years of clinical use. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 2013, 12, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, E.; Caranci, F.; Giordano, F.; et al. Gadolinium retention in the body: What we know and what we can do. Radiol. Med. 2017, 122, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, J.C.; Rodby, R.A.; Yee, J.; et al. Use of intravenous gadolinium-based contrast media in patients with kidney disease: Consensus statements from the American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation. Radiology 2021, 298, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starekova, J.; Bruce, R.J.; Sadowski, E.A.; et al. No cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after administration of gadoxetic acid. Radiology 2020, 297, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.Y.; Tseng, J.H.; Huang, B.S.; et al. Risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with impaired renal function undergoing fixed-dose gadoxetic acid–enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom. Radiol. (NY) 2021, 46, 3995–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, I.D.; Macleod, C.A.; Sathiadoss, P.; et al. Risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in oncology patients receiving gadoxetic acid and updated risk estimate in patients with moderate and severe renal impairment. Abdom. Radiol. (NY) 2022, 47, 1196–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Moon, W.J. Gadolinium deposition in the brain: Current updates. Korean J. Radiol. 2019, 20, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrychowicz, A.; Lubner, M.G.; Brown, J.J.; et al. Hepatobiliary MR imaging with gadolinium-based contrast agents. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 35, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühler, A.; Heinzelmann, I.; Weinmann, H.J. Elimination of gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-DTPA in a rat model of severely impaired liver and kidney excretory function: An experimental study in rats. Invest. Radiol. 1994, 29, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchin, M.A.; Lorusso, V.; Pirovano, G. Compensatory biliary and urinary excretion of gadobenate ion after administration of gadobenate dimeglumine (MultiHance®) in cases of impaired hepatic or renal function: A mechanism that may aid in the prevention of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Br. J. Radiol. 2015, 88, 20140526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwend, S.; Ebert, W.; Schultze-Mosgau, M.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and imaging properties of Gd-EOB-DTPA in patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Invest. Radiol. 2011, 46, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Radiology Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. Available online: https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Girardi, M.; Kay, J.; Elston, D.M.; et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Clinicopathological definition and workup recommendations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 1095–1106.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, R.G. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: Comparison of seven methods. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Siebenhandl-Wolff, P.; Tranquart, F.; et al. Gadolinium: Pharmacokinetics and toxicity in humans and laboratory animals following contrast agent administration. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aime, S.; Caravan, P. Biodistribution of gadolinium-based contrast agents, including gadolinium deposition. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2009, 30, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazella, M.A. Current status of gadolinium toxicity in patients with kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauenstein, T.; Ramirez-Garrido, F.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis risk after liver magnetic resonance imaging with gadoxetate disodium in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment: Results of a prospective, open-label, multicenter study. Invest. Radiol. 2015, 50, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieda, N.; van der Pol, C.B.; Walker, D.; et al. Adverse events to the gadolinium-based contrast agent gadoxetic acid: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 2020, 297, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, J.S.; Dohanish, S.; Balzer, T.; et al. Safety of gadoxetate disodium: Results from the clinical phase II–III development program and postmarketing surveillance. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 42, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.D.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.; et al. Half-dose gadoxetic acid–enhanced liver magnetic resonance imaging in patients at risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2015, 84, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz-Peer, G.; Neruda, A.; Watschinger, B.; et al. Prevalence of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following intravenous gadolinium contrast media administration in dialysis patients with end-stage renal disease. Eur. J. Radiol. 2010, 76, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Ishii, K.; Kawaguchi, H.; et al. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: Relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology 2014, 270, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Campos, R.O.; Heredia, V.; Ramalho, M.; et al. Quarter-dose (0.025 mmol/kg) gadobenate dimeglumine for abdominal MRI in patients at risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Preliminary observations. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 196, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, M.; Jones, J.R.; Weinreb, J.C. Gadolinium deposition and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A radiologist’s primer. Radiographics 2020, 40, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.N.; Gagnon, A.L.; Darling, M.D.; et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis manifesting a decade after exposure to gadolinium. JAMA Dermatol 2015, 151, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).