Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

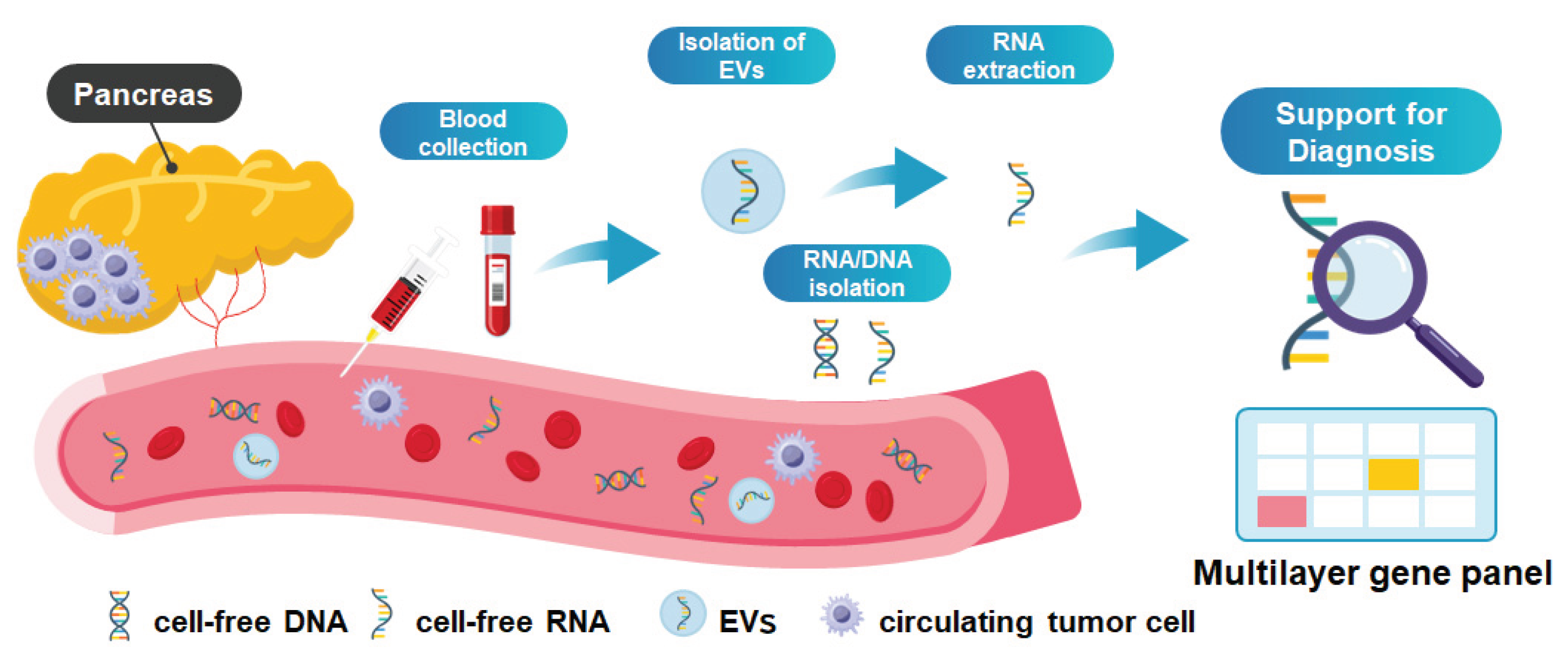

Despite extensive technological advances and an ever-growing body of literature, liquid biopsy has yet to achieve reliable early detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA). Numerous studies have investigated circulating tumor-derived components, including cell-free DNA (cfDNA), cell-free RNA (cfRNA), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and circulating tumor cells (CTCs), primarily using peripheral blood samples; however, their clinical utility for early-stage disease remains limited. The fundamental obstacles are biological rather than purely technical: early PDA and its precursor lesions, such as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN), are characterized by minimal tumor burden, low levels of nucleic acid shedding, and substantial background signals from non-neoplastic tissues. Increasing analytical complexity through multilayered liquid biopsy approaches, including analyses from pancreas-associated fluid, has not consistently translated into improved diagnostic performance and, in some cases, has amplified issues related to specificity, reproducibility, and interpretability. Moreover, molecular alterations detected in body fluids may reflect clonal expansion without inevitable malignant progression, raising concerns regarding overdiagnosis and clinical decision-making. Pre-analytical variability, lack of standardization, and limited access to tumor-adjacent fluids further hinder clinical implementation. Liquid biopsy should therefore be regarded as a complementary modality rather than a substitute for histopathological diagnosis, with its precise clinical role in early detection still ill-defined. In this review, we critically examine why liquid biopsy has not yet succeeded in early PDA detection, highlighting the key biological, technical, and clinical barriers that must be addressed to move the field beyond exploratory research toward meaningful clinical application.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Liquid Biopsy Using ctDNA: Current Limitations and Strategies to Address Them

3. Liquid Biopsy Using EV and RNA: Complementary Approaches and Remaining Challenges

4. Recent Application and Studies as Liquid Biopsy

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDA | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

| cfRNA | cell-free RNA |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| CTCs | circulating tumor cells |

| PanIN | pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia |

| IPMN | intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms |

| DF | duodenal fluid |

| PJ | pancreatic juice |

| CGP | cancer genome profiling |

| TAT | turnaround time |

| VAF | frequency |

| CHIP | clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential |

| dPCR | digital PCR |

| ncRNAs | non-coding RNAs |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| lncRNAs | long non-coding RNAs |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| APO2-iTQ | APOA2 isoform index |

| GnP | gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| CNV | copy-number variation |

| MCTA-Seq | methylated CpG tandem amplification and sequencing |

| GPC1 | Glypican-1 |

References

- Ignatiadis, M.; Sledge, G.W.; Jeffrey, S.S. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic - implementation issues and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siravegna, G.; Marsoni, S.; Siena, S.; Bardelli, A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017, 14, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Pan, Q.; Zhao, B. Liquid biopsy techniques and pancreatic cancer: diagnosis, monitoring, and evaluation. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Takeda, Y.; Ono, Y.; Isomoto, H.; Mizukami, Y. Current status of molecular diagnostic approaches using liquid biopsy. J Gastroenterol 2023, 58, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrmann, J.F.; Schmidt, C.M.; Mao, X.; Irajizad, E.; Loftus, M.; Zhang, J.; Patel, N.; Vykoukal, J.; Dennison, J.B.; Long, J.P.; et al. Lead-Time Trajectory of CA19-9 as an Anchor Marker for Pancreatic Cancer Early Detection. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1373–1383 e1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2010, 362, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisawa, T.; Wood, L.D.; Itoi, T.; Takaori, K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2016, 388, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Huang, C.; Cui Zhou, D.; Hu, Y.; Lih, T.M.; Savage, S.R.; Krug, K.; Clark, D.J.; Schnaubelt, M.; Chen, L.; et al. Proteogenomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell 2021, 184, 5031–5052 e5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, K.C.; Bardeesy, N.; Mizukami, Y. Diversity of Precursor Lesions For Pancreatic Cancer: The Genetics and Biology of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2017, 8, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topham, J.T.; Renouf, D.J.; Schaeffer, D.F. Circulating tumor DNA: toward evolving the clinical paradigm of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2023, 15, 17588359231157651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Ortiz, M.V.; Cano-Ramirez, P.; Toledano-Fonseca, M.; Aranda, E.; Rodriguez-Ariza, A. Diagnosing and monitoring pancreatic cancer through cell-free DNA methylation: progress and prospects. Biomark Res 2023, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrba, L.; Futscher, B.W.; Oshiro, M.; Watts, G.S.; Menashi, E.; Hu, C.; Hammad, H.; Pennington, D.R.; Golconda, U.; Gavini, H.; et al. Liquid biopsy, using a novel DNA methylation signature, distinguishes pancreatic adenocarcinoma from benign pancreatic disease. Clin Epigenetics 2022, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Tsuchikawa, T.; Kuraya, T.; Kuwabara, S.; Nakanishi, Y.; Asano, T.; Matsui, A.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Predictors of Long-Term Survival in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma after Pancreatectomy: TP53 and SMAD4 Mutation Scoring in Combination with CA19-9. Ann Surg Oncol 2022, 29, 5007–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, Y.; Ono, Y.; Morikawa, T.; Motoi, F.; Higuchi, R.; Yamamoto, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Karasaki, H.; Mizukami, Y.; Unno, M.; et al. Serine/Threonine Kinase 11 Plays a Canonical Role in Malignant Progression of KRAS-mutant and GNAS-wild-type Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Ann Surg 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Cao, C.; Lin, J.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, C.; Yang, R.; Zhu, D.; Wang, F.; et al. Development and Validation of a Cell-Free DNA Fragmentomics-Based Model for Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2025, 43, 2863–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Ikeda, M.; Bando, H.; Kato, K.; Morizane, C.; Esaki, T.; Komatsu, Y.; Kawamoto, Y.; Takahashi, N.; et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA sequencing in advanced gastrointestinal cancer: SCRUM-Japan GI-SCREEN and GOZILA studies. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wu, L.R.; Yan, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Chu, T.; Kwong, L.N.; Patel, A.A.; Zhang, D.Y. Limitations and opportunities of technologies for the analysis of cell-free DNA in cancer diagnostics. Nat Biomed Eng 2022, 6, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, S.E.; Lechner, J.M.; Williams, T.; Fernando, M.R. A stabilizing reagent prevents cell-free DNA contamination by cellular DNA in plasma during blood sample storage and shipping as determined by digital PCR. Clin Biochem 2013, 46, 1561–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ulrich, B.C.; Supplee, J.; Kuang, Y.; Lizotte, P.H.; Feeney, N.B.; Guibert, N.M.; Awad, M.M.; Wong, K.K.; Janne, P.A.; et al. False-Positive Plasma Genotyping Due to Clonal Hematopoiesis. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 4437–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, P.; Li, B.T.; Brown, D.N.; Jung, B.; Hubbell, E.; Shen, R.; Abida, W.; Juluru, K.; De Bruijn, I.; Hou, C.; et al. High-intensity sequencing reveals the sources of plasma circulating cell-free DNA variants. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, J.; Muinelo, L.; Dalmases, A.; Jones, F.; Edelstein, D.; Iglesias, M.; Orrillo, M.; Abalo, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Brozos, E.; et al. Plasma ctDNA RAS mutation analysis for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2017, 28, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, C; Takahashi, O.Y.K. Six-color multiplex digital PCR assays for screening and identification of multiple driver mutations associated with pancreatic carcinogenesis. Clin Chem. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Yan, I.; Haga, H.; Patel, T. Long noncoding RNA in liver diseases. Hepatology 2014, 60, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Role of Non-coding RNAs in Oncology. Cell 2019, 179, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Yeri, A.; Cheah, P.S.; Chung, A.; Danielson, K.; De Hoff, P.; Filant, J.; Laurent, C.D.; Laurent, L.D.; Magee, R.; et al. Small RNA Sequencing across Diverse Biofluids Identifies Optimal Methods for exRNA Isolation. Cell 2019, 177, 446–462 e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesteruk, K.; Levink, I.J.M.; de Vries, E.; Visser, I.J.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Cahen, D.L.; Fuhler, G.M.; Bruno, M.J. Extracellular vesicle-derived microRNAs in pancreatic juice as biomarkers for detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology 2022, 22, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yan, I.K.; Kogure, T.; Haga, H.; Patel, T. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of long non-coding RNA ROR modulates chemosensitivity in human hepatocellular cancer. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Li, Y.; Liao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Qian, L.; Zhao, J.; Zong, H.; Kang, B.; et al. Plasma extracellular vesicle long RNA profiling identifies a diagnostic signature for the detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2020, 69, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Zhu, Z.; Roy, S.; Jun, E.; Han, H.; Munoz, R.M.; Nishiwada, S.; Sharma, G.; Cridebring, D.; Zenhausern, F.; et al. An Exosome-based Transcriptomic Signature for Noninvasive, Early Detection of Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1252–1266 e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Hirano, S.; Nakamura, T.; Asano, T.; Okazaki, R.; Yoshida, K.; Kawase, T.; Kurahara, H.; Oi, H.; et al. A noninvasive urinary microRNA-based assay for the detection of pancreatic cancer from early to late stages: a case control study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 78, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Liu, F.; Fan, J.; Sun, D.; Liu, C.; Lyon, C.J.; Bernard, D.W.; Li, Y.; Yokoi, K.; Katz, M.H.; et al. Nanoplasmonic Quantification of Tumor-derived Extracellular Vesicles in Plasma Microsamples for Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring. Nat Biomed Eng 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; McAndrews, K.M. The role of extracellular vesicles in cancer. Cell 2023, 186, 1610–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.S.; Ciprani, D.; O'Shea, A.; Liss, A.S.; Yang, R.; Fletcher-Mercaldo, S.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Fernandez-Del Castillo, C.; Weissleder, R. Extracellular Vesicle Analysis Allows for Identification of Invasive IPMN. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1345–1358 e1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Inuzuka, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Sawamoto, K.; Taniue, K.; Ono, Y.; Asai, F.; Koyama, K.; Sato, H.; Kawabata, H.; et al. Liquid Biopsy for Pancreatic Cancer by Serum Extracellular Vesicle-Encapsulated Long Noncoding RNA HEVEPA. Pancreas 2024, 53, e395–e404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Matsuzaki, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yoneoka, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Shimizu, H.; Uehara, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Ikeda, S.I.; Sonoda, T.; et al. Integrated extracellular microRNA profiling for ovarian cancer screening. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiro, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Oh, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Atsumi, J.; Nagashima, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Nara, S.; Hijioka, S.; Morizane, C.; et al. Clinical development of a blood biomarker using apolipoprotein-A2 isoforms for early detection of pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol 2024, 59, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Hayashida, Y.; Umaki, T.; Okusaka, T.; Kosuge, T.; Kikuchi, S.; Endo, M.; Tsuchida, A.; Aoki, T.; Itoi, T.; et al. Possible detection of pancreatic cancer by plasma protein profiling. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 10613–10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Okusaka, T.; Rinaudo, J.A.; Huang, Y.; Marsh, T.; Sanada, M.; Sasajima, Y.; Nakamori, S.; Shimahara, M.; et al. Plasma biomarker for detection of early stage pancreatic cancer and risk factors for pancreatic malignancy using antibodies for apolipoprotein-AII isoforms. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 15921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, K.; Shimizu, A.; Tsushima, K.; Kobayashi, M. Potential of Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 and Serum Apolipoprotein A2-Isoforms in the Diagnosis of Stage 0 and IA Pancreatic Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Terashima, T.; Morinaga, S.; Miyagi, Y.; Yoshida, E.; Yoshimura, T.; Seiki, M.; Kaneko, S.; Ueno, M.; et al. EphA2 Proteolytic Fragment as a Sensitive Diagnostic Biomarker for Very Early-stage Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma. Cancer Res Commun 2023, 3, 1862–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhao, X.; Luo, N.; Xiao, M.; Feng, F.; An, Y.; Chen, J.; Rong, L.; Yang, Y.; Peng, J. Circulating cell-free DNA methylation analysis of pancreatic cancer patients for early noninvasive diagnosis. Front Oncol 2025, 15, 1552426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehiro, Y.; Suenaga, S.; Kunimune, Y.; Yada, S.; Hamamoto, K.; Tsuyama, T.; Amano, S.; Matsui, H.; Higaki, S.; Fujii, I.; et al. CA19-9 in Combination with Methylated HOXA1 and SST Is Useful to Diagnose Stage I Pancreatic Cancer. Oncology 2022, 100, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachida, S.; Yoshinaga, S.; Shiba, S.; Urabe, M.; Tanaka, H.; Takeda, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Sakamoto, Y.; Hijioka, S.; Haba, S.; et al. KRAS Mutations in Duodenal Lavage Fluid after Secretin Stimulation for Detection of Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Ohtsuka, T.; Asano, K.; Kimura, H.; Ohuchida, K.; Kitada, H.; Ideno, N.; Mori, Y.; Tokunaga, S.; Oda, Y.; et al. S100P in Duodenal Fluid Is a Useful Diagnostic Marker for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2017, 46, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideno, N.; Mori, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Ohtsuka, T. Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Role of Biomarkers in Pancreatic Fluid Samples. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Dong, Z.; Zhen, L.; Xia, G.; Huang, X.; Wang, T.; Guo, H.; Yang, B.; Xu, C.; Wu, W.; et al. Combined Exosomal GPC1, CD82, and Serum CA19-9 as Multiplex Targets: A Specific, Sensitive, and Reproducible Detection Panel for the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2020, 18, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Xu, L.; Jin, L.; Xu, K.; Tang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wang, J. Exosomal circular RNA hsa_circ_0006220, and hsa_circ_0001666 as biomarkers in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. J Clin Lab Anal 2022, 36, e24447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makler, A.; Narayanan, R.; Asghar, W. An Exosomal miRNA Biomarker for the Detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makler, A.; Asghar, W. Exosomal miRNA Biomarker Panel for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Detection in Patient Plasma: A Pilot Study. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shi, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Nagelschmitz, J.; Doelling, M.; Al-Madhi, S.; Mukund Mahajan, U.; Pech, M.; Rose, G.; et al. Human multiethnic radiogenomics reveals low-abundancy microRNA signature in plasma-derived extracellular vesicles for early diagnosis and molecular subtyping of pancreatic cancer. Elife 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.D.; Patel, B.; Crnogorac-Jurcevic, T. Extracellular Vesicle-Derived miRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Systematic Review of Methodological Rigour and Clinical Applicability. Biomark Insights 2025, 20, 11772719251381960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Ota, Y.; Kogure, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Iwamoto, H.; Yamakita, K.; Kitano, Y.; Fujii, S.; Haneda, M.; Patel, T.; et al. Circulating extracellular vesicle-encapsulated HULC is a potential biomarker for human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci 2020, 111, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analysis target | Molecular target | Type of clinical sample | Potential roles for liquid biopsy for PDA diagnosis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cfDNA | cfDNA fragmentation pattern | plasma | Machine learning models integrating cfDNA fragmentation patterns, including fragment sizes and end motifs. | Yin et al (2025) [15] |

| cfRNA / EV | 13 miRNAs (5 cfRNA and 8 EV RNA) | plasma / serum | The combination of 13-miRNA signature archived an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.98 in training cohort and 0.93 in validation cohort for PDA detection. | Nakamura et al (2022) [29] |

| EV | EV miRNA-based detection set | urine | Machine learning of urinary extracellular vesicle miRNA combinations showed high diagnostic accuracy for PDA, including early-stage disease. | Baba et al (2024) [30] |

| EV | MUC5AC | plasma | MUC5AC in plasma EVs was shown to distinguish high-grade IPMNs from low-grade IPMNs with high sensitivity and specificity. | Yang et al (2021) [33] |

| EV | lncRNA HEVEPA | serum | HEVEPA expression was upregulated in serum EVs from PDA patients compared to healthy controls and IPMN patients, achieving an AUC of 0.86. | Takahashi et al (2024) [33] |

| protein | APO2-iTQ | blood | APOA2 isoform index (APO2-iTQ) has been implemented as an adjunctive marker for PDA diagnosis in Japan. | Hanada et al. (2024) [39] |

| protein | EphA2-NF | serum | EphA2-NF is associated with poor prognosis among patients receiving GnP treatment, and has potential clinical utility as both a diagnostic and prognostic marker. | Sato et al. (2023) [40] |

| cfDNA | methylated CpG tandem amplification | plasma | Methylation scoring and typing system achieved a sensitivity of 97% and 86% for patients in the discovery and validation cohorts, respectively, with a specificity of 100% in both cohorts for PDA. | Hu et al. (2025) [41] |

| cfDNA | methylated Homeobox A1 (mHOXA1) and methylated somatostatin (mSST) | serum | Analysis of mHOXA1 and mSST combination with CA19-9 showed to be useful to detect early stage of PDA. | Suehiro et al. (2022) [42] |

| cfDNA | KRAS | DF | KRAS mutation analysis of DF collected after secretin administration showed high diagnostic accuracy for PDA. | Yachida et al. (2025) [43] |

| protein | S100P | DF | The sensitivity and specificity of S100P protein expression in DF for diagnosing stages 0/IA/IB/IIA PDAC were 85% and 77%, respectively, with an AUC of 0.82. | Ideno et al. (2020) [45] |

| EV | Glypican-1 (GPC1) | serum | GPC1-positive EVs, in combination with CD82 and CA19-9, have demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy for differentiating PDA from chronic pancreatitis (AUC 0.942). | Xiao et al. (2020) [46] |

| EV | circRNAs (circ_0006220 and circ_0001666) | plasma | circ_0006220 and circ_0001666) were found to correlate with CA19-9 levels, tumor size, and lymph node metastasis; the combination of these two circRNAs yielded an AUC of 0.884 for PDA diagnosis. | Hong et al. (2022) [47] |

| EV | 10 miRNAs | plasma | Ten miRNAs highly expressed in the body fluids of patients with PDA was selected using public databases; These miRNAs were identified and verified as EV-miRNA candidates for early detection. | Makler et al. (2022) [48] |

| EV | 4 miRNAs | plasma | EV-miRNA panel comprising four miRNAs (miR-93-5p, miR-339-3p, and miR-425-5p/3p) achieved diagnostic accuracy comparable to or greater than CA19-9 (AUC 0.885). | Makler et al. (2023) [49] |

| EV | molecular clustering of miRNAs | plasma | CT imaging features (radiomics) with the expression analysis of plasma EV-derived miRNAs (e.g., miR-1260b), improved the accuracy of differentiating malignant from benign pancreatic lesions to an AUC > 0.90. | Xu et al. (2025) [50] |

| EV | miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-10b, miR-451a) | blood | Systematic review demonstrated the utility of plasma and serum EV-derived miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-10b, miR-451a) in the diagnosis of PDA. | Patel et al. (2025) [51] |

| EV | HULC | serum | EV encapsulated HULC in serum was increased in serum derived from patients with PDA with AUC of 0.92. | Takahashi et al. (2020) [52] |

| DF; duodenal fluid, | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).