Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supply Chain

2.2. Logistics

2.3. Digitalization of SC&LS

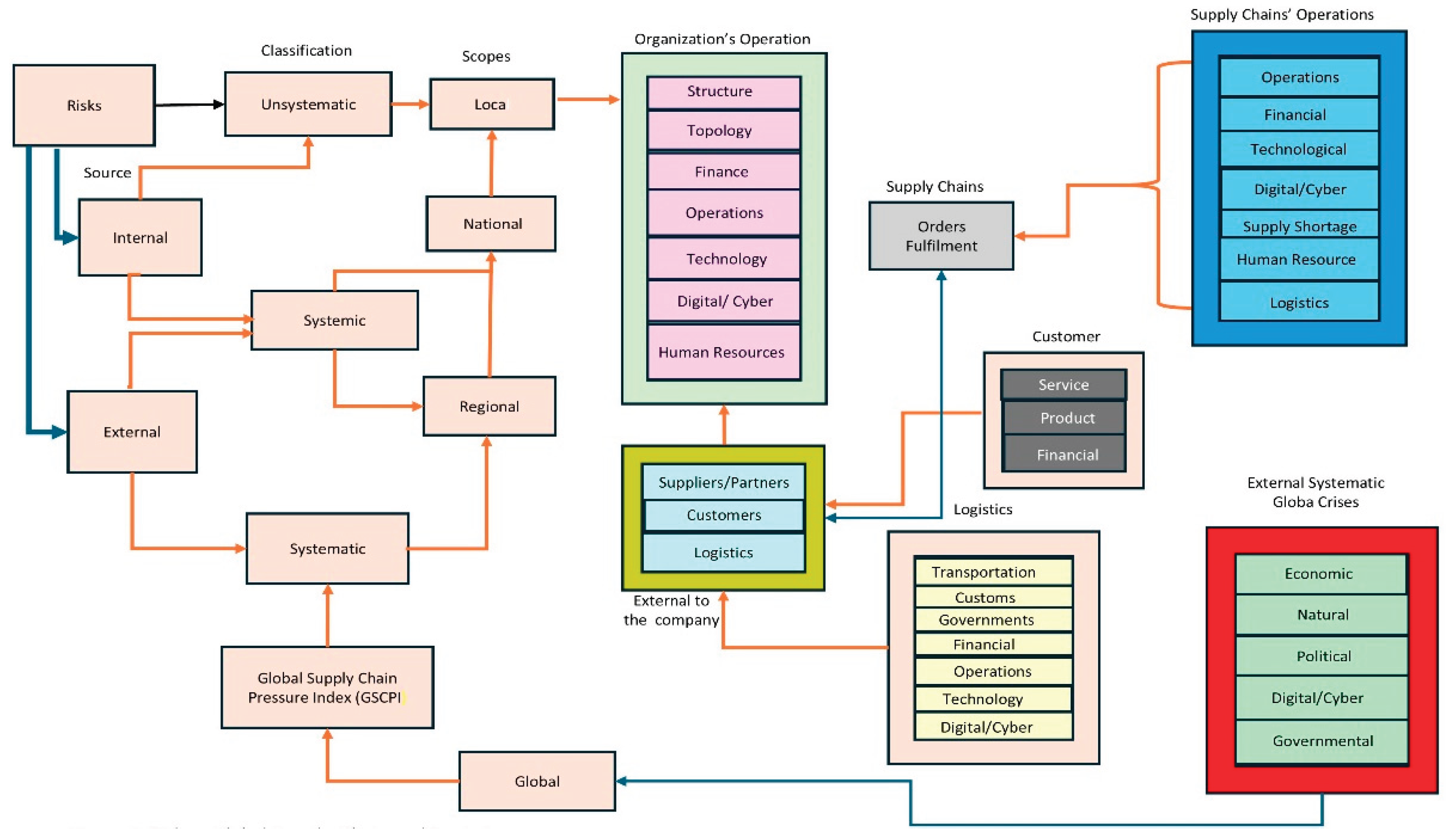

2.4. Risks

2.5. Pressure on SC&L System

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

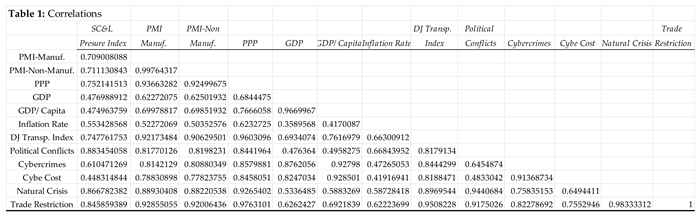

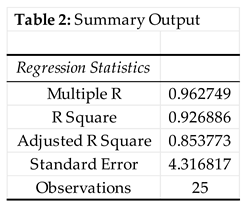

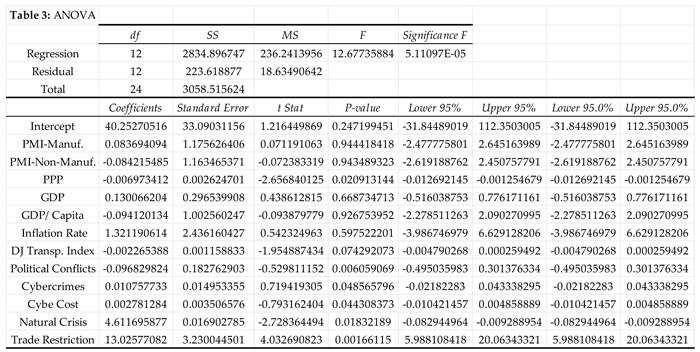

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Discussion

4. Summary

References

- Benjamin, R.; Wigand, R. Electronic markets and virtual value chains on the information superhighway. MIT Sloan Management Review 1995, 36, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Heri, N. The effect of fragmentation as a moderator on the relationship between supply chain management and project performance. ADI Journal on Emerging Innovation 2024, 6(1), 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, M.; Madura, J.; 3. Learning banks’ exposure to systematic risk: Evidence from the financial crisis of 2008. Journal of Financial Research. 2014, 37(1), 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C. Impacts of September 11. In Tourism in the Muslim world; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Mishra, P.; Arora, N. Linkages between environmental issues and zoonotic diseases: with reference to COVID-19. Pandemic. Environmental Sustainability 2021, 4(3), 455–467. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42398-021-00165-x. [CrossRef]

- Saadat, R.; Rawtani, D.; Hussain, C.; 6. Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 728, 138870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadare, F.; Okoffo, E. Covid-19 face masks: A potential source of microplastic fibers in the environment. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 737(1), 140279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 8. United Nations Trade Development. 2024. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdr2024_en.pdf.

- McKibbin, W.; Fernando, R. The global economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic Modelling 2023, 129, 106551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, D. The Twenty-First Century Sanity, Therapy, Love, by Capra and Kirsner. In eBook, 1st Edition; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Bose, D. A review of the sustainable development goals to make headways through the COVID-19 pandemic era. In Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy.; Wiley Online Library, 2023; Volume 42, 4, p. e14093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, R. Social insanity. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism 2004, 15(3), 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itskovich, E. Economic inequality, relative deprivation, and crime: An individual-level examination. Justice Quarterly 2025, 42(4), 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broćić, M. Alienation and activism. American Journal of Sociology 2023, 128(5), 1291–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E. Democrats Panic Social Instantly. 2025. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pT17JrXtOeo.

- World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2025/.

- Benigno, G.; Giovanni, J.; et al. A new barometer of global supply chain pressures. In Liberty Street Economics.; Federal Reserve Bank of New York., 2022; Volume 17, Available online: https://metaintelligence.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/frbny-barometer_global_supply_chain_pressures.pdf.

- Forrester, J.; Optner, S. Systems Analysis; Prentice: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bucklin, P. A theory of distribution channel structure; IBER Special Publications: Berkeley, CA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, K.; Webber, M. Supply-chain management: logistics catches up with strategy. In The roots of logistics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 183–194. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-27922-5_15.2012.

- Houlihan, J. International Supply Chains: A New Approach. Management Decision 1988, 26(3), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Riley, D. Using Inventory for Competitive Advantage through Supply Chain Management. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Materials Management 1985, 15(5), 16–26. Available online: https://sci-hub.se/10.1108/eb014615. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G. Integrating the Supply Chain. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management. 1989, 19(8), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Modarress, B. JIT Brings Problems and Solutions. In Purchasing World; March 1990; pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, S. T. Estimating discrete-choice models of product differentiation. The RAND Journal of Economics 1994, 25(2), 242–262. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2555829. [CrossRef]

- LaLonde, B. J.; Pohlen, T. Issues in supply chain costing. The International Journal of Logistics Management 1996, 7(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. The agile supply chain: competing in volatile markets. Industrial marketing management 2000, 29(1), 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarress, B.; Ansari, A.; Ansari, A. Examining Sustainability Alignment of Supplier Selection Criteria during Industrial Revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15(22), 15930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sharma, M. Prioritizing alternatives to improve supply chain flexibility. Production Planning & Control. 2014, 25(2), 176–192. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard Business Review 2008, 86(1), 78. Available online: https://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/data/sw-library/cognos/pdfs/articles/art_the_five_competitive_forces_that_shape_strategy.pdf.

- Gunasekaran, A.; McGaughey, R. TQM is suppy chain management. The TQM magazine. 2003, 15(6), 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, S.; Gereffi, G.; Raj-Reichert, G. Introduction to the handbook on global value chains. In Handbook on global value chains; Edward Elgar Publishing; pp. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Zamora, A. Value chain analysis: A brief review. Asian Journal of Innovation and Policy 2016, 5(2), 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Fernandez-Stark, K. Global value chain analysis: a primer. 2016. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10161/12488.

- Dias, P.; Henriques, P.; et al. Obesity and Public Policies: The Brazilian Government’s Definitions and Strategies. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2017, 33, e00006016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibowo, I. Operational Management in the Digital Era: Strategic Integration with Entrepreneurship. Journal Ilmiah Multidisiplin Indonesia (JIM-ID) 2023, 2(02), 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kain, R.; Verma, A. Logistics management in supply chain–an overview. Materials today: proceedings 2018, 5(2), 3811–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellram, L.; Cooper, M. Supply chain management, partnership, and the shipper-third-party relationship. The international journal of logistics management 1990, 1(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A.; Kumar, M. Lean six sigma and industry 4.0 integration for operational excellence: evidence from Italian manufacturing companies. Production Planning and Control. 2021, 32(13), 084–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, N.; Anass, C.; et al. Supply chain management in the Industry 5.0 era: strategic implications. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Economics 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/426390921/GSCM.

- Modarress; Ansari; Ansari. Sustainable Development and Ecological Deficit in the United Arab Emirates. Sustainability 2021, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Modarress, B.; Ansari, A.; Ansari, A. Impacts of Technological Convergence on Human Development for Sustainable Economy. Sustainability and Climate Change 2021, 15(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jjami, R.; Boussalham, K. Resilient supply chains in Industry 5.0: Leveraging AI for predictive maintenance and risk mitigation. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research 2024, 6(4), 25116. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, L.; Puertas, R.; García, L. The importance of the Logistics Performance Index in international trade. Applied economics. 2014, 46(24), 2982–2992. [Google Scholar]

- Rashwan, M. APICS definition of Supply Chain Management. 2017. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/apics-definition-supply-chain-management-mohamed-rashwan.

- Wagner, S.; Bode, C. An empirical examination of supply chain performance along several dimensions of risk. Journal of Business Logistics 2008, l. 29(1), 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, G. Pure logistics: the science of war preparation; Barakaldo Books, 2022; Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/3545290/pure-logistics-the-science-of-war-preparation-pdf.

- Ghiani, G.; Laporte, G.; Musmanno, R. Introduction to Logistics Systems Planning and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Berkeley, CA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://download.e-bookshelf.de/download/0000/5687/47/L-G-0000568747-0002356833.pdf.

- Langley, J.; Holcomb, C. Creating logistics customer value. Journal of Business Logistics 1992, 13, 1–27. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1280779.

- 53; Cooper, J. Logistics and distribution planning: strategies for management. Logistics & Distribution Planning: Strategies for Management., 2nd ed.; Kogan Page, 1994; Available online: https://openlibrary.org/books/OL16693428M/Logistics_and_distribution_planning.

- Lambert, D.; Stock, J. Strategic logistics management, 4th ed.; Irwin/McGraw-Hill, 2000; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Strategic-Logistics-Management-Irwin-Marketing/dp/0256088381.

- Bowersox, J.; Closs, J. Logistical management: The integrated supply chain process; McGraw-Hill College, 1966; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3440920.

- Kukovič, D.; Topolšek, D.; et al. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for logistics, examining the general definition of subcategories. Business Logistics in Modern Management. 2014, 111–122. Available online: https://ojs.srce.hr/index.php/plusm/article/view/3903.

- Novack, R.; Rinehart, L.; Wells, M. Rethinking Concept Foundations in Logistics Management. Journal of Business Logistics 1992, 13(2), 233–267. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Poist, R. Socially responsible logistics: an exploratory study. Transportation Journal. 2002, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 59; Serrano, A.; Dusko, K.; et al. Evolution of military logistics. Logistics 2023, 7(2), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 60; Volland, J.; Fügener, A.; Schoenfelder, J.; Brunner, J. Material logistics in hospitals: A literature review. Omega 2017, 69, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, A.; Cabral, J.; Costa, Á. Logistic optimization in tourism networks. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering 2022, 10, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Kopczak, L. From logistics to supply chain management: the path forward in the humanitarian sector. Fritz Institute 2005, 15(no. 1), 1–15. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2642736.

- Herold, M.; Breitbarth, T.; et al. Sport logistics research: reviewing and line marking of a new field. The International Journal of Logistics Management. 2020, 31(2), 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Research on the impact of smart logistics on the manufacturing industry chain resilience. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 9052. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-93806-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau Logistics. What is Logistics? 2024. Available online: https://www.logisticsbureau.com/what-is-logistics/.

- Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. Springer Nature Link; 2018; Available online: https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-1-349-94186-5_366.

- Desai, H.; Remer, B.; et al. Vehicle Routing for the Last-Mile Logistics Problem. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.05464. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.; Garg, R.; Sachdeva, A. Framework to precede collaboration in supply chain. Benchmarking: An International Journal. 2018, 25(8), 2635–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Ngai, E.; Cheng, T. Developing an e-logistics system: a case study. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications. 2007, 10(4), 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, J.; DeWitt, W.; et al. Defining Supply Chain Management. Journal of Business Logistics 2001, 22(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarocka, M.; Wang, H. Definition and Classification Criteria of Logistics Services for the Elderly. Engineering Management in Production and Services 2018, 21(10(4)). Available online: https://reference-global.com/2/v2/download/pdf/10.2478/emj-2018-0023. [CrossRef]

- 72; Erceg, A.; Sekuloska, J. E-logistics and e-SCM: how to increase competitiveness. LogForum, Scientific Journal of Logistics 2019, 15(1), 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/search.html?PROD_isoorg_en%5Bquery%5D=iso%20definition.

- Tubis, A.; Grzybowska, K.; Król, B. Supply chain in the digital age: A Scientometric–Thematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15(14), 11391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, B. Digitalization in logistics. In Project management in logistics and supply chain management: Practical guide with examples from industry, trade and services; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2022; pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Yue, X.; et al. Smart supply chain management: A review and implications for future research. International Journal of Logistics Management 2016, 27(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Göçer, F. Digital Supply Chain: Literature Review and a Proposed Framework for Future Research. Computers in Industry 2018, 97, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Ukko, J.; et al. Managing the digital supply chain: The role of smart technologies. Technovation 2020, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederico, F.; Garza-Reyes, J.; et al. Performance measurement for supply chains in the Industry 4.0 era: a balanced scorecard approach. International journal of productivity and performance management. 2021, 70(4), 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, A.; Mangan, J.; Christopher, M. The self-thinking supply chain. Supply Chain Management: International Journal 2019, 24(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Rüsch, M. Industry 4.0 and the current status as well as future prospects on logistics. Computers in industry. 2017, 89, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, A. Smart manufacturing. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56(2), 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardakçi, H. Benefits of digitalization in international logistics sector. International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research 2020, 5(06), 1476–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Seidel, T.; et al. Logistics networks: coping with nonlinearity and complexity. In Managing Complexity: Insights, Concepts. Applications.; Springer, 2008; pp. 119–136. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-540-75261-5_6.

- Eckert, V.; Curran, C.; Bhardwaj, S. Tech breakthroughs megatrend: how to prepare for its impact. PricewaterhouseCoopers. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/techmegatrend.

- Wamba, S.; Queiroz, M. Industry 4.0 and the supply chain digitalization: a blockchain diffusion perspective. Production Planning & Control. 2020, 33(2-3), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- . [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, B.; Hong, P. Does ownership structure matter for firm technological innovation performance? The case of Korean firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review 2012, 20(3), 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Social Network Analysis: Organizational Implications in Tourism Management. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 2021, 29(2), 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, G.; Spens, K. Identifying challenges in humanitarian logistics. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2009, 39(6), 506–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Chen, B. Ecological Network Analysis for a Virtual Water Network. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49(11), 6722–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzio, G.; O’Bray, L.; Borgwardt, K. Biological network analysis with deep learning. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2021, 22(2), 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilkenny, M.; Fuller-Love, N. Network analysis and business networks. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 2014, 15(21(3)), 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollashahi, H.; Fakhrzad, M. The competition among supply chains regarding environmental, social, and resilience aspects in a supply chain network design problem. Journal of Modelling in Management 2025, 20(1), 182–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Korine, H.; Szulanski, G. Interunit communication in multinational corporations. Management Science 1994, 40(1), 96–110. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2632847. [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Bartlett, C. The multinational corporation as an interorganizational network. Academy of Management Review. 1990, 15(4), 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G. The Management of Innovation; Tavistock, London, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Optimal and hierarchical controls in dynamic stochastic manufacturing systems: A survey. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 2002, 4(2), 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, T.; et al. Structural investigation of supply networks: A social network analysis approach. Journal of Operations Management 2011, 29(3), 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, L.; Ghezzi, C.; et al. Topology aware adaptive security. In Proceedings of the 9th international symposium on software engineering for adaptive and self-managing systems, 2014; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Bell, M.; Bliemer, M. Network science approaches modelling the topology and robustness of supply chain networks: review and perspective. Applied Network Science. 2017, 2(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, P.; Thakkar, J. J.; Ghosh, K. K. Analysis of supply chain sustainability in the context of supply chain complexity, with an inter-relationship study using the Delphi method and interpretive structural modeling for the Indian mining and earthmoving machinery industry. Resources Policy 2020, 68, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiendahl, H.; Scholtissek, P. Management and control of complexity in manufacturing. CIRP annals 1994, 43(2), 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, E.; White, C.; et al. Prevalence and patterns of higher-order drug interactions in Escherichia coli. NPJ systems biology and applications 2018, 4(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J. A Primer on Hyperloop Travel: How far off is the Future? In Rudin Center for Transportation Policy & Management; New York University, 2024; Volume 105. [Google Scholar]

- Idoughi, D.; Kolski, C.; Seffah, A. Design principles of web-based services in large-scale e-logistics processes. IFAC Proceedings 2010, 9(8), 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, H. The Impact of Perceived Risk, Perceived Benefit, and Trust on Customer Intention To Use Tokopedia Apps. Jurnal Bisnis Strategi 2022, 31(2), 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Aven, T.; Renn, O. On risk defined as an event where the outcome is uncertain. Journal of Risk Research. 2009, 12(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.; Renn, O. Systemic risks: Intersections between science and society with policy implications for sustainability. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources 2020, 23(2), 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Global supply chain survey. 2023. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor market trends. 2024. Available online: https://www.bls.gov.

- World Bank. Commodity price forecasts. 2024. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org.

- Gartner. Supply chain analytics. 2024. Available online: https://www.gartner.com.

- Johnson, S. Systems integration and the social solution of technical problems in complex systems. The business of systems integration 2023, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 115; Hudnurkar, M.; Deshpande, S.; et al. Supply chain risk classification schemes: A literature review. Operations and Supply Chain Management: An International Journal. 2017, 10(4), 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 116; Renn, O. Systemic risks: The new kid on the block. Environment: science and policy for sustainable development 2016, 58(2), 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook on systemic risk; Fouque, J., Langsam, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2013; Available online: https://openlibrary.org/books/OL28506093M/Handbook_on_Systemic_Risk.

- 118; Tummala, R.; Mak, C. A risk management model for improving operation and maintenance activities in electricity transmission networks. Journal of the Operational Research Society. 2001, 52(2), 125–134. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/254139.

- Kleindorfer, P.; Saad, G. Managing disruption risks in supply chains. Production and operations management 2005, 14(1), 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Shen, S. Supply chain risk assessment and control of port enterprises: Qingdao port as case study. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 2018, 34(3), 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Hensher, D. Risk management in public–private partnerships. Australian Accounting 2015, 25(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Risk Governance Council Guidelines for Governing Systemic Risks; EPFL International Risk Governance Center: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2018.

- Renn, O.; Laubichler, M.; et al. Systemic risks from different perspectives. Risk analysis 2020, 42(9), 1902–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, I. Intelligent policy making for a complex world: Pragmatism, evidence, and learning. Political Studies 2009, 57(4), 699–719. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/polstu/v57y2009i4p699-719.html. [CrossRef]

- 126; Schweizer, J.; Renn, O. Editorial: Systemic risks and risk communication. International Journal of Performability Engineering 2015, 11(6), 521–522. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285582152_Guest.Editorial?en-.

- 127; Scholz, R. Digital threat and vulnerability management: The SVIDT method. Sustainability 2017, 9(4), 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanze, J. Resilience in flood risk management–Exploring its added value for science and practice. FLOODrisk - 3rd European Conference on Flood Risk Management, 2016; Available online: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2016/02/e3sconf_flood2016_08003.pdf.

- Kleisner, K.; Tureček, P.; 129. Cultural and biological evolution: What is the difference? Biosemiotics 2017, 10(1), 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinke, A.; Renn, O. The coming of age of risk governance. Risk Analysis 2019, 41(3), 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, T. The structure of scientific revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1977; p. 962. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2022. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2022-annual-report.pdf.

- World Bank. 2023. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099092823161580577.

- Our World in Data. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/.

- International Telecommunication Union. 2025. Available online: https://council.itu.int/2025/en/.

- United Nations Data. 2025. Available online: https://council.itu.int/2025/en/.

- Statista. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).