Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Registration

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Brief Data Description

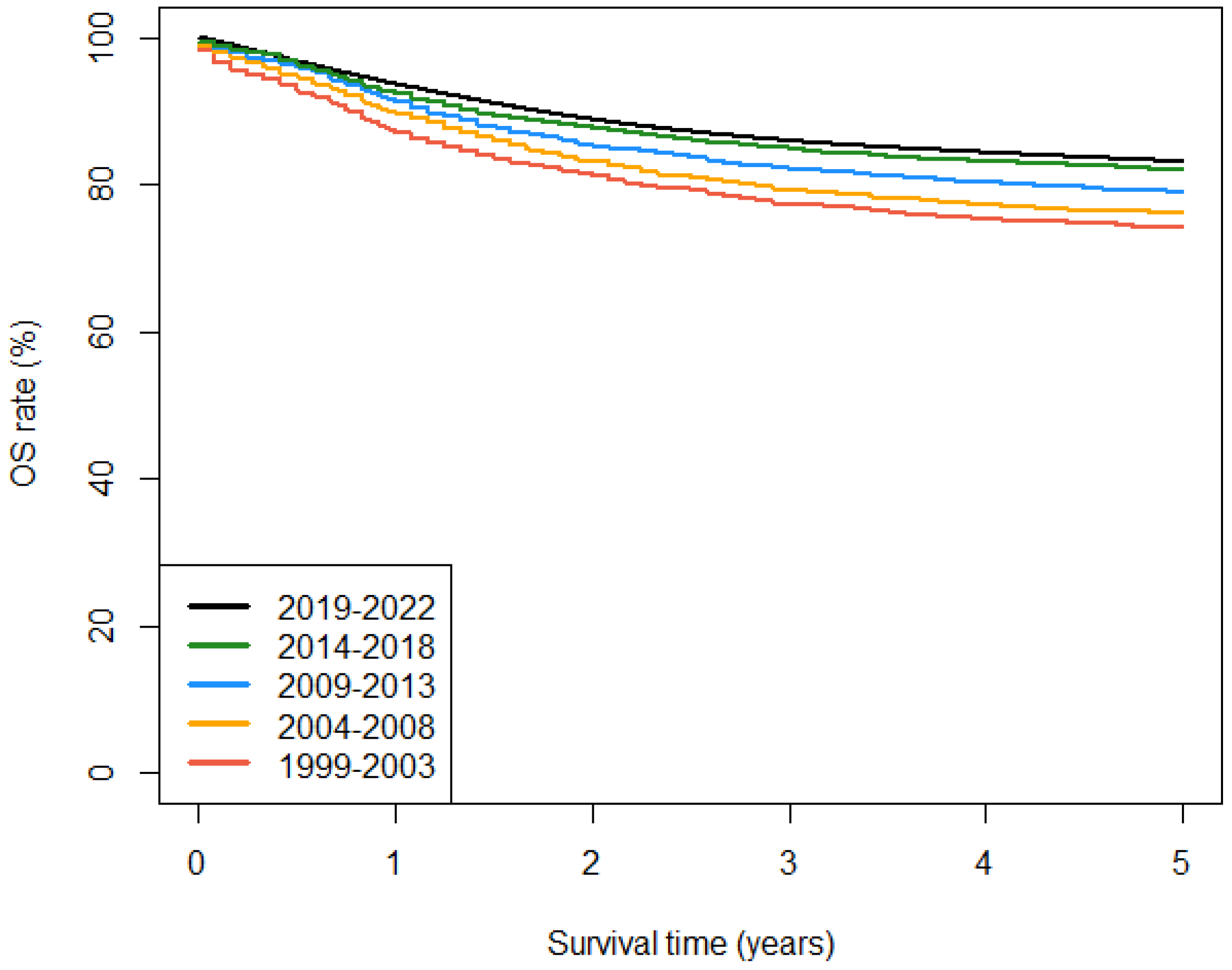

3.2. Observed Survival

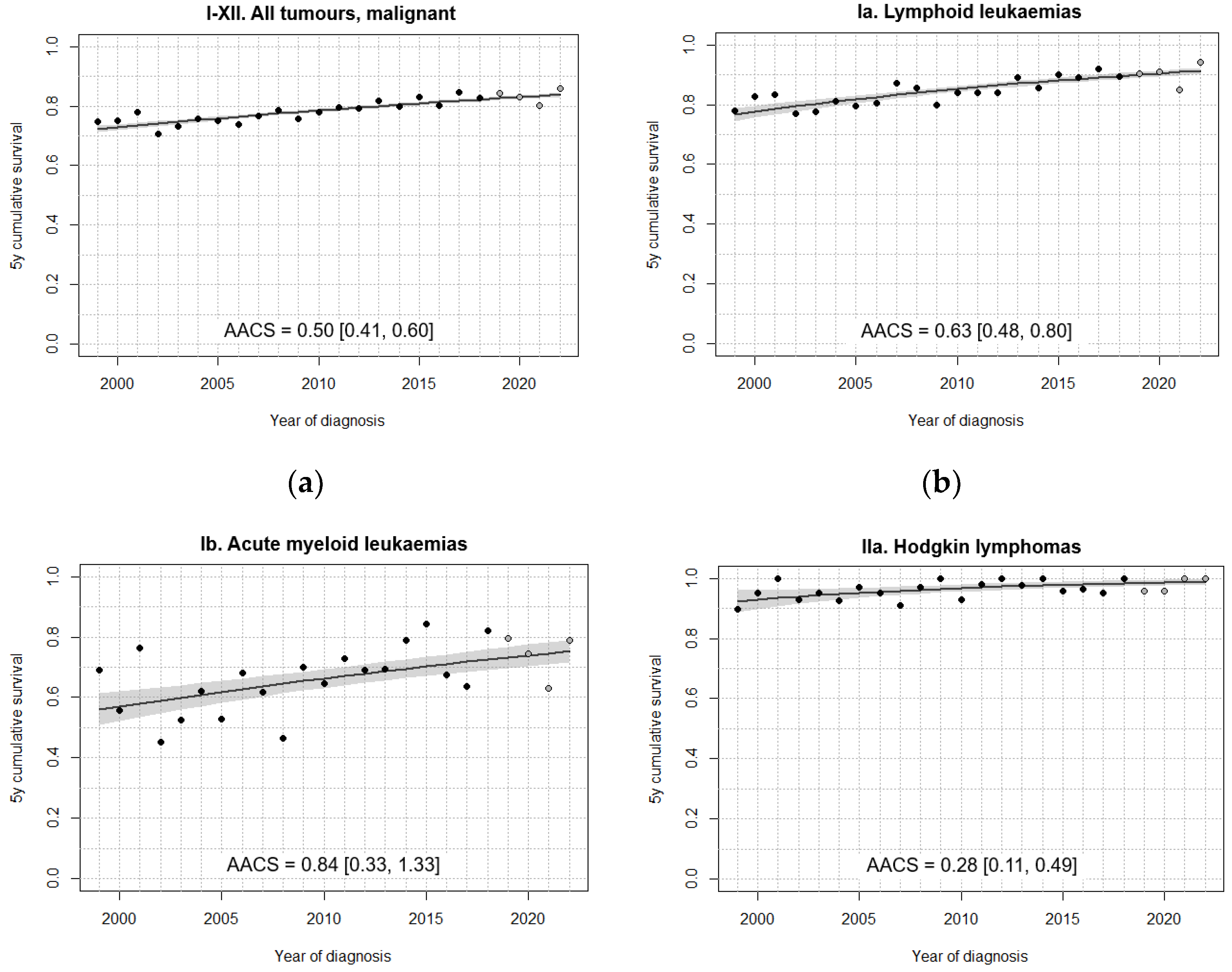

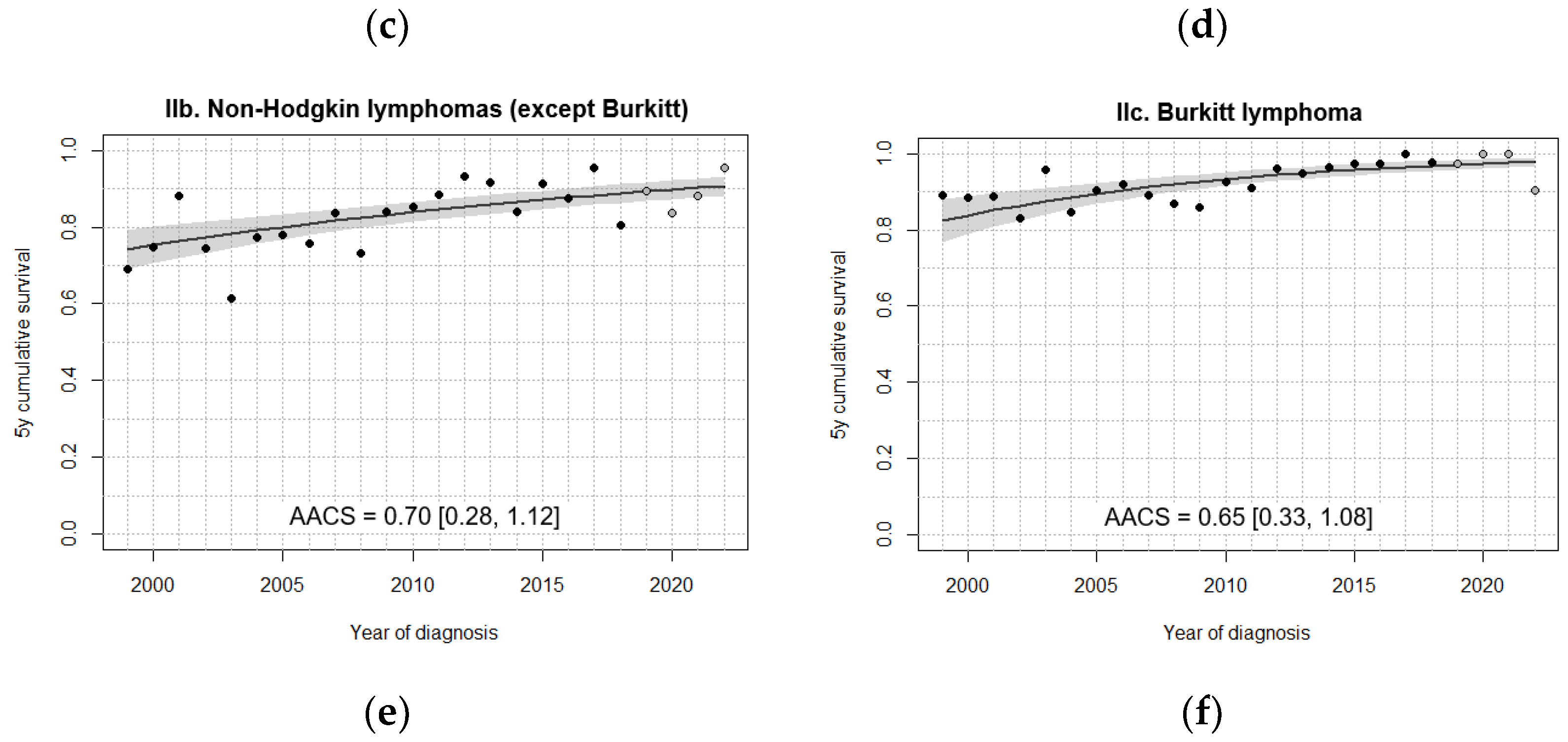

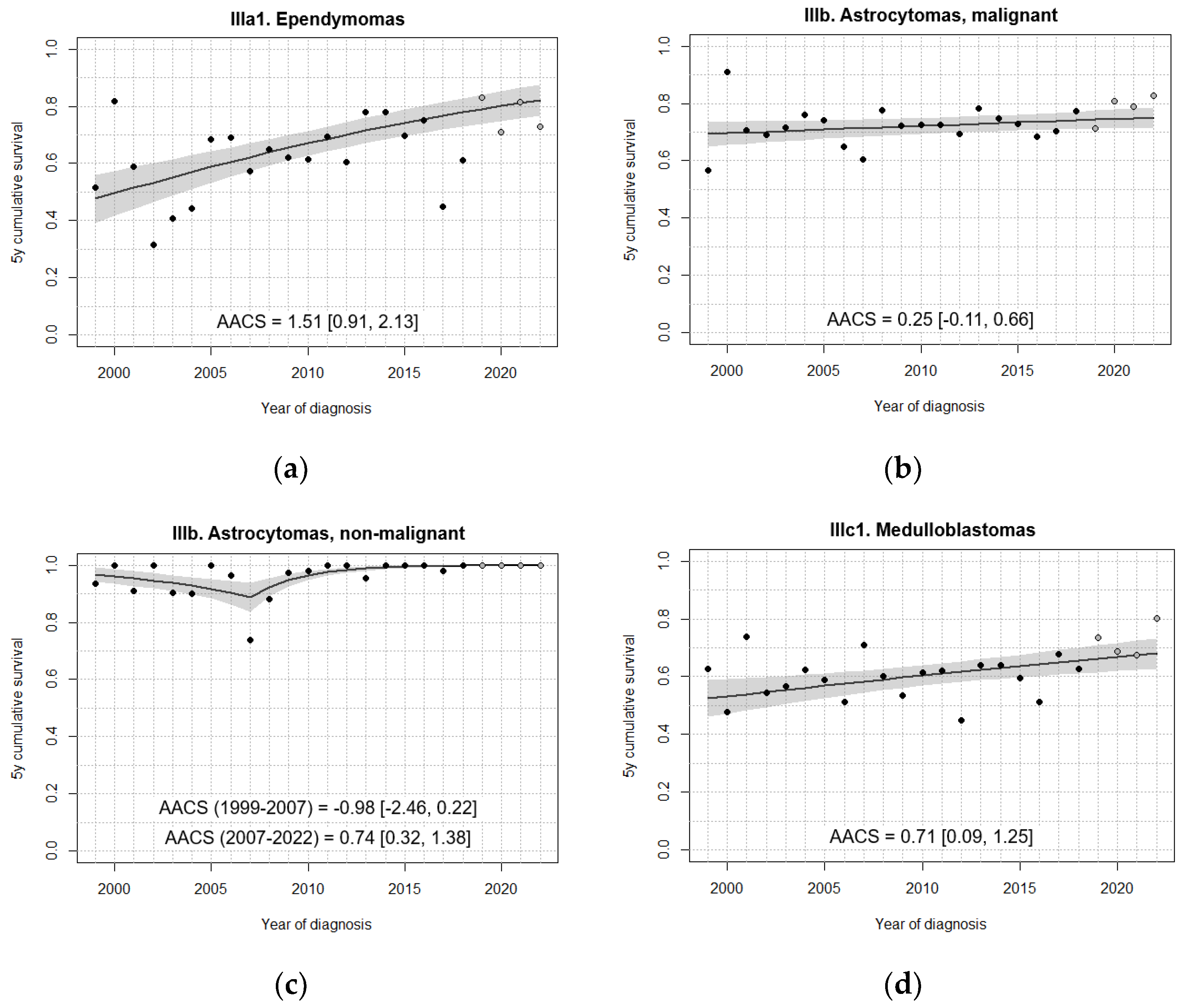

3.3. Survival Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AACS | Absolute annual change in survival |

| ALCL | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukaemia |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| BL | Burkitt lymphoma |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| GCT | Germ cell tumours |

| HIC | High-income countries |

| HL | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| ICCC | International Childhood Cancer Classification |

| ICD-O | International Classification of Diseases for Oncology |

| LBL | Lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| LL | Lymphoid leukaemias |

| NHL | Non-Hodgkin lymphomas |

| OS | Overall survival |

| RETI-SEHOP | Spanish Registry of Childhood Tumours |

| SEHOP | Spanish Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology |

Appendix A

References

- Pritchard-Jones, K; Pieters, R; Reaman, GH; Hjorth, L; Downie, P; Calaminus, G; Naafs-Wilstra, MC; Steliarova-Foucher, E. Sustaining innovation and improvement in the treatment of childhood cancer: lessons from high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14(3), e95–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steliarova-Foucher, E; Colombet, M; Ries, LAG; Moreno, F; Dolya, A; Bray, F; Hesseling, P; Shin, HY; Stiller, CA. IICC-3 contributors. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001-10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2017 Jun;18(6):e301. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30369-8. 2017, 18(6), 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete Nieto, A; Pardo Romaguera, E; Alfonso Comos, P; Valero Poveda, S; Porta Cebolla, S; Peris Bonet, R. 45 años de Estadísticas del Cáncer infantil en España. Universidad de Valencia; Valencia, 2025. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10550/112145.

- Botta, L; Gatta, G; Capocaccia, R; Stiller, C; Cañete, A; Dal Maso, L; Innos, K; Mihor, A; Erdmann, F; Spix, C; Lacour, B; Marcos-Gragera, R; Murray, D; Rossi, S; EUROCARE-6 Working Group. Long-term survival and cure fraction estimates for childhood cancer in Europe (EUROCARE-6): results from a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23(12), 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cromie, KJ; Hughes, NF; Milner, S; Crump, P; Grinfeld, J; Jenkins, A; Norman, PD; Picton, SV; Stiller, CA; Yeomanson, D; Glaser, AW; Feltbower, RG. Socio-economic and ethnic disparities in childhood cancer survival, Yorkshire, UK. Br J Cancer 2023, 128(9), 1710–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellbrock, M; Spix, C; Ronckers, CM; Grabow, D; Filbert, AL; Borkhardt, A; Wollschläger, D; Erdmann, F. Temporal patterns of childhood cancer survival 1991 to 2016: A nationwide register-study based on data from the German Childhood Cancer Registry. Int J Cancer 2023, 153(4), 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pession, A; Quarello, P; Zecca, M; Mosso, ML; Rondelli, R; Milani, L; De Rosa, M; Rosso, T; Maule, M; Fagioli, F. Survival rates and extra-regional migration patterns of children and adolescents with cancer in Italy: The 30-year experience of the Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (AIEOP) with the Italian hospital-based registry of pediatric cancer (Mod. 1.01). Int J Cancer 2024, 155(10), 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, PF. The impact of cooperative group studies on childhood cancer: Improving outcomes and quality and international collaboration. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019, 28(6), 150857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, L; O’Brien, MM. Only the beginning: 50 years of progress toward curing childhood cancer. Cell 2024, 187(7), 1584–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J; Pohl, A; Volland, R; Hero, B; Dübbers, M; Cernaianu, G; Berthold, F; von Schweinitz, D; Simon, T. Complete surgical resection improves outcome in INRG high-risk patients with localized neuroblastoma older than 18 months. BMC Cancer 2017, 17(1), 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, KW; Lautz, TB; Malek, MM; Cost, NG; Newman, EA; Dasgupta, R; Christison-Lagay, ER; Tiao, GM; Davidoff, AM. COG Surgery Discipline Committee. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2023 blueprint for research: Surgery. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2024, 71(3), e30766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, JC; Scrushy, MG; Gillory, LA; Pandya, SR. Utilization of robotics in pediatric surgical oncology. Semin Pediatr Surg 2023, 32(1), 151263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, W; Thulasi Seetha, S; Refaee, TAG; Lieverse, RIY; Granzier, RWY; Ibrahim, A; Keek, SA; Sanduleanu, S; Primakov, SP; Beuque, MPL; Marcus, D; van der Wiel, AMA; Zerka, F; Oberije, CJG; van Timmeren, JE; Woodruff, HC; Lambin, P. Radiomics: from qualitative to quantitative imaging. Br J Radiol 2020, 93(1108), 20190948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izurieta-Pacheco, AC; Ramaswamy, V; Tsang, DS; Rutka, J; Wasserman, J; Guger, S; Weidman, DR; Nathan, PC; Scheinemann, K; Bennett, J. Late Effects in Survivors of Pediatric Medulloblastoma: A Comprehensive Review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2025, e32132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K; Chen, Y; Ahn, S; Zheng, M; Landoni, E; Dotti, G; Savoldo, B; Han, Z. GD2-specific CAR T cells encapsulated in an injectable hydrogel control retinoblastoma and preserve vision. Nat Cancer 2020, 1(10), 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneuchi, Y; Yoshida, S; Fujiwara, T; Evans, S; Abudu, A. Limb salvage surgery has a higher complication rate than amputation but is still beneficial for patients younger than 10 years old with osteosarcoma of an extremity. J Pediatr Surg. 2022, 57(11), 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, DM. The role of cancer registries in cancer control. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008, 13(2), 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C; Martos, C; Ardanaz, E; Galceran, J; Izarzugaza, I; Peris-Bonet, R; Martínez, C; Spanish Cancer Registries Working Group. Population-based cancer registries in Spain and their role in cancer control. Ann Oncol. 2010, 21 Suppl 3, iii3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, A; Percy, C; Jack, A; Shanmugartnam, K; Sobin, L; Parkin, DM; Author 1, A.; Author 2, B.; International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed; 1st revision. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; WHO: Geneva; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Steliarova-Foucher, E; Colombet, M; Ries, LAG; Rous, B; Stiller, CA. Classification of tumours. In International Incidence of Childhood Cancer, Vol. III (electronic version); Steliarova-Foucher, E, Colombet, M, Ries, LAG, Moreno, F, Dolya, A, Shin, HY, Hesseling, P, Stiller, CA, Eds.; IARC: Lyon, France, 2017; Available online: https://iicc.iarc.fr/classification/.

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 763/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 July 2008 on population and housing censuses. Off J Eur Union 2008, L218, 14–20. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/763/oj (accessed on December 2025).

- Vincent, TJ; Bayne, AM; Brownbill, PA; Stiller, CA; Stiller, C. Methods. In Childhood Cancer in Britain: Incidence, Survival, Mortality.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007; pp. 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, H; Gefeller, O. An alternative approach to monitoring cancer patient survival. Cancer 1996, 78(9), 2004–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronin, K; Mariotto, A; Scoppa, S; Green, D; Clegg, L. Differences between Brenner et al. and NCI Methods for calculating period survival. Technical report 2003-02-A; Statistical Research and Application Branch, National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, F; Di Carlo, V; Stiller, C; Gatta, G; Woods, RR; Visser, O; Lacour, B; Tucker, TC; Coleman, MP; Allemani, C; CONCORD Working Group. Global survival trends for brain tumors, by histology: Analysis of individual records for 67,776 children diagnosed in 61 countries during 2000-2014 (CONCORD-3). Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25(3), 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotto, AB; Zhang, F; Buckman, DW; Miller, D; Cho, H; Feuer, EJ. Characterizing Trends in Cancer Patients’ Survival Using the JPSurv Software. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021, 30(11), 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleczek, B; Brenner, H. Model based period analysis of absolute and relative survival with R: data preparation, model fitting and derivation of survival estimates. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2013, 110(2), 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steliarova-Foucher, E; Colombet, M; Ries, LAG; Rous, B; Stiller, CA. Indicators of data quality. In International Incidence of Childhood Cancer, Vol. III (electronic version); Steliarova-Foucher, E, Colombet, M, Ries, LAG, Moreno, F, Dolya, A, Shin, HY, Hesseling, P, Stiller, CA, Eds.; IARC: Lyon, France, 2017; Available online: https://iicc.iarc.who.int/results/introduction/qualityindicators.pdf.

- Brenner, H; Gefeller, O; Hakulinen, T. Period analysis for ‘up-to-date’ cancer survival data: theory, empirical evaluation, computational realisation and applications. Eur J Cancer 2004, 40(3), 326–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peirelinck, H; Schulpen, M; Hoogendijk, R; Van Damme, A; Pieters, R; Henau, K; Van Damme, N; Karim-Kos, HE. Incidence, survival, and mortality of cancer in children and young adolescents in Belgium and the Netherlands in 2004-2015: A comparative population-based study. Int J Cancer 2024, 155(2), 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registre National des Cancers de l’Enfant. Les chiffres: statistiques de survie [Internet]. Paris (France): Registre National des Cancers de l’Enfant. Available online: https://rnce.inserm.fr/rnce/les-chiffres/ (accessed on December 2025).

- Digital, NHS. Cancer survival in England, cancers diagnosed 2016 to 2020, followed up to 2021 [Internet]. Leeds (England): NHS Digital, 2023. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/cancer-survival-in-england/cancers-diagnosed-2016-to-2020-followed-up-to-2021 (accessed on December 2025).

- Lacour, B; Goujon, S; Guissou, S; Guyot-Goubin, A; Desmée, S; Désandes, E; Clavel, J. Childhood cancer survival in France, 2000-2008. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014, 23(5), 449–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, LA; Spector, LG. Survival Differences Between Males and Females Diagnosed With Childhood Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2019, 3(2), pkz032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguid, A; Mattiucci, D; Ottersbach, K. Infant leukaemia—faithful models, cell of origin and the niche. Dis Model Mech. 2021, 14(10), dmm049189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balduzzi, A; Buechner, J; Ifversen, M; Dalle, JH; Colita, AM; Bierings, M. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia in the Youngest: Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Beyond. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 807992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure, A; Harewood, R; Stiller, CA; Gatta, G; Clavel, J; Stefan, DC; Carreira, H; Spika, D; Marcos-Gragera, R; Peris-Bonet, R; Piñeros, M; Sant, M; Kuehni, CE; Murphy, MFG; Coleman, MP; Allemani, C. CONCORD Working Group. Worldwide comparison of survival from childhood leukaemia for 1995-2009, by subtype, age, and sex (CONCORD-2): a population-based study of individual data for 89 828 children from 198 registries in 53 countries. Lancet Haematol Erratum in: Lancet Haematol. 2017 May;4(5):e201. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30067-4. 2017, 4(5), e202–e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, GN; Edmonston, DY; Dirks, GC; Boop, FA; Merchant, TE. Conformal Radiation Therapy for Ependymoma at Age ≤3 Years: A 25-Year Experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023, 116(4), 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-San-Simón, A; Ritzmann, TA; Obrecht-Sturm, D; Benesch, M; Timmermann, B; Leblond, P; Kilday, JP; Poggi, G; Thorp, N; Massimino, M; van Veelen, ML; Schuhmann, M; Thomale, UW; Tippelt, S; Schüller, U; Rutkowski, S; Grundy, RG; Bolle, S; Fernández-Teijeiro, A; Pajtler, KW. European standard clinical practice recommendations for newly diagnosed ependymoma of childhood and adolescence. EJC Paediatr Oncol. 2025, 5, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, NK; Zhang, J; Lu, C; Parker, M; Bahrami, A; Tickoo, SK; Heguy, A; Pappo, AS; Federico, S; Dalton, J; Cheung, IY; Ding, L; Fulton, R; Wang, J; Chen, X; Becksfort, J; Wu, J; Billups, CA; Ellison, D; Mardis, ER; Wilson, RK; Downing, JR; Dyer, MA; St Jude Children’s Research Hospital–Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Association of age at diagnosis and genetic mutations in patients with neuroblastoma. JAMA 2012, 307(10), 1062–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, I; Alfaar, AS; Sultan, Y; Salman, Z; Qaddoumi, I. Trends in childhood cancer: Incidence and survival analysis over 45 years of SEER data. PLoS One 2025, 20(1), e0314592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trallero, J; Sanvisens, A; Almela Vich, F; Jeghalef El Karoni, N; Saez Lloret, I; Díaz-Del-Campo, C; Marcos-Navarro, AI; Aizpurua Atxega, A; Sancho Uriarte, P; De-la-Cruz Ortega, M; Sánchez, MJ; Perucha, J; Franch, P; Chirlaque, MD; Guevara, M; Ameijide, A; Galceran, J; Ramírez, C; Camblor, MR; Alemán, MA; Gutiérrez, P; Marcos-Gragera, R; REDECAN. Incidence and time trends of childhood hematological neoplasms: a 36-year population-based study in the southern European context, 1983-2018. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1197850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R; De Lorenzo, P; Ancliffe, P; Aversa, LA; Brethon, B; Biondi, A; Campbell, M; Escherich, G; Ferster, A; Gardner, RA; Kotecha, RS; Lausen, B; Li, CK; Locatelli, F; Attarbaschi, A; Peters, C; Rubnitz, JE; Silverman, LB; Stary, J; Szczepanski, T; Vora, A; Schrappe, M; Valsecchi, MG. Outcome of Infants Younger Than 1 Year With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated With the Interfant-06 Protocol: Results From an International Phase III Randomized Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019, 37(25), 2246–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sluis, IM; de Lorenzo, P; Kotecha, RS; Attarbaschi, A; Escherich, G; Nysom, K; Stary, J; Ferster, A; Brethon, B; Locatelli, F; Schrappe, M; Scholte-van Houtem, PE; Valsecchi, MG; Pieters, R. Blinatumomab Added to Chemotherapy in Infant Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388(17), 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssenyonga, N; Stiller, C; Nakata, K; Shalkow, J; Redmond, S; Bulliard, JL; Girardi, F; Fowler, C; Marcos-Gragera, R; Bonaventure, A; Saint-Jacques, N; Minicozzi, P; De, P; Rodríguez-Barranco, M; Larønningen, S; Di Carlo, V; Mägi, M; Valkov, M; Seppä, K; Wyn Huws, D; Coleman, MP; Allemani, C; CONCORD Working Group. Worldwide trends in population-based survival for children, adolescents, and young adults diagnosed with leukaemia, by subtype, during 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual data from 258 cancer registries in 61 countries. Lancet Child Adolesc Health Erratum in: Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(7):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00165-1. 2022, 6(6), 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffmann, M; Rasche, M; Zimmermann, M; von Neuhoff, C; Creutzig, U; Dworzak, M; Scheffers, L; Hasle, H; Zwaan, CM; Reinhardt, D; Klusmann, JH. Therapy reduction in patients with Down syndrome and myeloid leukemia: the international ML-DS 2006 trial. Blood 2017, 129(25), 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, MA; Montesinos, P; Kim, HT; Ruiz-Argüelles, GJ; Undurraga, MS; Uriarte, MR; Martínez, L; Jacomo, RH; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, H; Melo, RA; Bittencourt, R; Pasquini, R; Pagnano, K; Fagundes, EM; Vellenga, E; Holowiecka, A; González-Huerta, AJ; Fernández, P; De la Serna, J; Brunet, S; De Lisa, E; González-Campos, J; Ribera, JM; Krsnik, I; Ganser, A; Berliner, N; Ribeiro, RC; Lo-Coco, F; Löwenberg, B; Rego, EM. IC-APL and PETHEMA and HOVON Groups. All-trans retinoic acid with daunorubicin or idarubicin for risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukaemia: a matched-pair analysis of the PETHEMA LPA-2005 and IC-APL studies. Ann Hematol. 2015, 94(8), 1347–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierens, A; Arad-Cohen, N; Cheuk, D; De Moerloose, B; Fernandez Navarro, JM; Hasle, H; Jahnukainen, K; Juul-Dam, KL; Kaspers, G; Kovalova, Z; Lausen, B; Norén-Nyström, U; Palle, J; Pasauliene, R; Jan Pronk, C; Saks, K; Zeller, B; Abrahamsson, J. Mitoxantrone Versus Liposomal Daunorubicin in Induction of Pediatric AML With Risk Stratification Based on Flow Cytometry Measurement of Residual Disease. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42(18), 2174–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulpen, M; Goemans, BF; Kaspers, GJL; Raaijmakers, MHGP; Zwaan, CM; Karim-Kos, HE. Increased survival disparities among children and adolescents & young adults with acute myeloid leukemia: A Dutch population-based study. Int J Cancer 2022, 150(7), 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwaan, CM; Kolb, EA; Reinhardt, D; Abrahamsson, J; Adachi, S; Aplenc, R; De Bont, ES; De Moerloose, B; Dworzak, M; Gibson, BE; Hasle, H; Leverger, G; Locatelli, F; Ragu, C; Ribeiro, RC; Rizzari, C; Rubnitz, JE; Smith, OP; Sung, L; Tomizawa, D; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, MM; Creutzig, U; Kaspers, GJ. Collaborative Efforts Driving Progress in Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015, 33(27), 2949–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauz-Körholz, C; Landman-Parker, J; Fernández-Teijeiro, A; Attarbaschi, A; Balwierz, W; Bartelt, JM; Beishuizen, A; Boudjemaa, S; Cepelova, M; Ceppi, F; Claviez, A; Daw, S; Dieckmann, K; Fosså, A; Gattenlöhner, S; Georgi, T; Hjalgrim, LL; Hraskova, A; Karlén, J; Kurch, L; Leblanc, T; Mann, G; Montravers, F; Pears, J; Pelz, T; Rajić, V; Ramsay, AD; Stoevesandt, D; Uyttebroeck, A; Vordermark, D; Körholz, D; Hasenclever, D; Wallace, WH; Kluge, R. Response-adapted omission of radiotherapy in children and adolescents with early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma and an adequate response to vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and doxorubicin (EuroNet-PHL-C1): a titration study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24(3), 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patte, C; Auperin, A; Michon, J; Behrendt, H; Leverger, G; Frappaz, D; Lutz, P; Coze, C; Perel, Y; Raphaël, M; Terrier-Lacombe, MJ; Société Française d’Oncologie Pédiatrique. The Société Française d’Oncologie Pédiatrique LMB89 protocol: highly effective multiagent chemotherapy tailored to the tumor burden and initial response in 561 unselected children with B-cell lymphomas and L3 leukemia. Blood 2001, 97(11), 3370–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minard-Colin, V; Aupérin, A; Pillon, M; Burke, GAA; Barkauskas, DA; Wheatley, K; Delgado, RF; Alexander, S; Uyttebroeck, A; Bollard, CM; Zsiros, J; Csoka, M; Kazanowska, B; Chiang, AK; Miles, RR; Wotherspoon, A; Adamson, PC; Vassal, G; Patte, C; Gross, TG. European Intergroup for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; Children’s Oncology Group. Rituximab for High-Risk, Mature B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Children. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382(23), 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, E; Burkhardt, B; Zimmermann, M; Meyer, U; Woessmann, W; Klapper, W; Wrobel, G; Rosolen, A; Pillon, M; Escherich, G; Attarbaschi, A; Beishuizen, A; Mellgren, K; Wynn, R; Ratei, R; Plesa, A; Schrappe, M; Reiter, A; Bergeron, C; Patte, C; Bertrand, Y. Results and conclusions of the European Intergroup EURO-LB02 trial in children and adolescents with lymphoblastic lymphoma. Haematologica 2017, 102(12), 2086–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, A; Schrappe, M; Ludwig, WD; Tiemann, M; Parwaresch, R; Zimmermann, M; Schirg, E; Henze, G; Schellong, G; Gadner, H; Riehm, H. Intensive ALL-type therapy without local radiotherapy provides a 90% event-free survival for children with T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: a BFM group report. Blood 2000, 95(2), 416–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm-Welk, C; Mussolin, L; Zimmermann, M; Pillon, M; Klapper, W; Oschlies, I; d’Amore, ES; Reiter, A; Woessmann, W; Rosolen, A. Early assessment of minimal residual disease identifies patients at very high relapse risk in NPM-ALK-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood 2014, 123(3), 334–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, B; Taj, M; Garnier, N; Minard-Colin, V; Hazar, V; Mellgren, K; Osumi, T; Fedorova, A; Myakova, N; Verdu-Amoros, J; Andres, M; Kabickova, E; Attarbaschi, A; Chiang, AKS; Bubanska, E; Donska, S; Hjalgrim, LL; Wachowiak, J; Pieczonka, A; Uyttebroeck, A; Lazic, J; Loeffen, J; Buechner, J; Niggli, F; Csoka, M; Krivan, G; Palma, J; Burke, GAA; Beishuizen, A; Koeppen, K; Mueller, S; Herbrueggen, H; Woessmann, W; Zimmermann, M; Balduzzi, A; Pillon, M. Treatment and Outcome Analysis of 639 Relapsed Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas in Children and Adolescents and Resulting Treatment Recommendations. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13(9), 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knörr, F; Brugières, L; Pillon, M; Zimmermann, M; Ruf, S; Attarbaschi, A; Mellgren, K; Burke, GAA; Uyttebroeck, A; Wróbel, G; Beishuizen, A; Aladjidi, N; Reiter, A; Woessmann, W. European Inter-Group for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Stem Cell Transplantation and Vinblastine Monotherapy for Relapsed Pediatric Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Results of the International, Prospective ALCL-Relapse Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020, 38(34), 3999–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mato, S; Castrejón-de-Anta, N; Colmenero, A; Carità, L; Salmerón-Villalobos, J; Ramis-Zaldivar, JE; Nadeu, F; Garcia, N; Wang, L; Verdú-Amorós, J; Andrés, M; Conde, N; Celis, V; Ortega, MJ; Galera, A; Astigarraga, I; Perez-Alonso, V; Quiroga, E; Jiang, A; Scott, DW; Campo, E; Balagué, O; Salaverria, I. MYC-rearranged mature B-cell lymphomas in children and young adults are molecularly Burkitt Lymphoma. Blood Cancer J 2024, 14(1), 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaford, E; Maycock, S; Alexander, S; Beishuizen, A; Wistinghausen, B; Minard-Colin, V; Rigaud, C; Phillips, CA; Ford, JB; Kearns, PR; Lawson, A; Williams, E; Ahmed, Z; Muzaffar, M; Parsons, R; Gore, L; Scobie, N; Buenger, V; Allen, C; Mellgren, K; Bollard, CM; Auperin, A; Billingham, L; Burke, GAA. A global study of novel agents in paediatric and adolescent relapsed and refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Glo-BNHL). Blood 2023, 142 Suppl 1, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirlaque MD, Peris-Bonet R, Sánchez A, Cruz O, Marcos-Gragera R, Gutiérrez-Ávila G, Quirós-García JR, Almela-Vich F, López de Munain A, Sánchez MJ, Franch-Sureda P, Ardanaz E, Galceran J, Martos C, Salmerón D, Gatta G, Botta L, Cañete A, The Spanish Childhood Cancer Epidemiology Working Group. Childhood and Adolescent Central Nervous System Tumours in Spain: Incidence and Survival over 20 Years: A Historical Baseline for Current Assessment. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15, 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15245889.

- Ritzmann TA, Chapman RJ, Kilday JP, Thorp N, Modena P, Dineen RA, Macarthur D, Mallucci C, Jaspan T, Pajtler KW, Giagnacovo M, Jacques TS, Paine SML, Ellison DW, Bouffet E, Grundy RG. SIOP Ependymoma I: Final results, long-term follow-up, and molecular analysis of the trial cohort-A BIOMECA Consortium Study. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24, 936-948. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noac012.

- Merchant TE, Bendel AE, Sabin ND, Burger PC, Shaw DW, Chang E, Wu S, Zhou T, Eisenstat DD, Foreman NK, Fuller CE, Anderson ET, Hukin J, Lau CC, Pollack IF, Laningham FH, Lustig RH, Armstrong FD, Handler MH, Williams-Hughes C, Kessel S, Kocak M, Ellison DW, Ramaswamy V. Conformal Radiation Therapy for Pediatric Ependymoma, Chemotherapy for Incompletely Resected Ependymoma, and Observation for Completely Resected, Supratentorial Ependymoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37, 974-983. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01765.

- Gnekow AK, Walker DA, Kandels D, Picton S, Giorgio Perilongo, Grill J, Stokland T, Sandstrom PE, Warmuth-Metz M, Pietsch T, Giangaspero F, Schmidt R, Faldum A, Kilmartin D, De Paoli A, De Salvo GL; of the Low Grade Glioma Consortium and the participating centers. A European randomised controlled trial of the addition of etoposide to standard vincristine and carboplatin induction as part of an 18-month treatment programme for childhood (≤16 years) low grade glioma—A final report. Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:206-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.019. Erratum in: Eur J Cancer. 2018;90:156-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.11.017.

- Grill J, Massimino M, Bouffet E, Azizi AA, McCowage G, Cañete A, Saran F, Le Deley MC, Varlet P, Morgan PS, Jaspan T, Jones C, Giangaspero F, Smith H, Garcia J, Elze MC, Rousseau RF, Abrey L, Hargrave D, Vassal G. Phase II, Open-Label, Randomized, Multicenter Trial (HERBY) of Bevacizumab in Pediatric Patients With Newly Diagnosed High-Grade Glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36, 951-958. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0611.

- Dhall G, Grodman H, Ji L, Sands S, Gardner S, Dunkel IJ, McCowage GB, Diez B, Allen JC, Gopalan A, Cornelius AS, Termuhlen A, Abromowitch M, Sposto R, Finlay JL. Outcome of children less than three years old at diagnosis with non-metastatic medulloblastoma treated with chemotherapy on the “Head Start” I and II protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50, 1169–1175. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21525.

- Dhall G, O’Neil SH, Ji L, Haley K, Whitaker AM, Nelson MD, Gilles F, Gardner SL, Allen JC, Cornelius AS, Pradhan K, Garvin JH, Olshefski RS, Hukin J, Comito M, Goldman S, Atlas MP, Walter AW, Sands S, Sposto R, Finlay JL. Excellent outcome of young children with nodular desmoplastic medulloblastoma treated on “Head Start” III: a multi-institutional, prospective clinical trial. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22, 1862-1872. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noaa102.

- Leary SES, Packer RJ, Li Y, Billups CA, Smith KS, Jaju A, Heier L, Burger P, Walsh K, Han Y, Embry L, Hadley J, Kumar R, Michalski J, Hwang E, Gajjar A, Pollack IF, Fouladi M, Northcott PA, Olson JM. Efficacy of Carboplatin and Isotretinoin in Children With High-risk Medulloblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial From the Children’s Oncology Group. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7, 1313-1321. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2224.

- Alfonso-Comos P, Cañete A, Briz-Redón Á, Romaguera EP, Segura V, Ramal D, Martínez de Las Heras B, Fernández-Teijeiro A; Spanish Neuroblastoma Working Group. Incidence and survival among children with neuroblastoma in Spain over 22 years. BMC Cancer. 2025;25, 1548. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-025-14877-4.

- Schaiquevich P, Francis JH, Cancela MB, Carcaboso AM, Chantada GL, Abramson DH. Treatment of Retinoblastoma: What Is the Latest and What Is the Future. Front Oncol. 2022;12:822330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.822330.

- Ora I, van Tinteren H, Bergeron C, de Kraker J; SIOP Nephroblastoma Study Committee. Progression of localised Wilms’ tumour during preoperative chemotherapy is an independent prognostic factor: a report from the SIOP 93-01 nephroblastoma trial and study. Eur J Cancer. 2007 Jan;43, 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.033. Epub 2006 Nov 2. PMID: 17084075.

- van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Hol JA, Pritchard-Jones K, van Tinteren H, Furtwängler R, Verschuur AC, Vujanic GM, Leuschner I, Brok J, Rübe C, Smets AM, Janssens GO, Godzinski J, Ramírez-Villar GL, de Camargo B, Segers H, Collini P, Gessler M, Bergeron C, Spreafico F, Graf N; International Society of Paediatric Oncology — Renal Tumour Study Group (SIOP–RTSG). Position paper: Rationale for the treatment of Wilms tumour in the UMBRELLA SIOP-RTSG 2016 protocol. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14, 743-752. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2017.163.

- Zsíros J, Maibach R, Shafford E, Brugieres L, Brock P, Czauderna P, Roebuck D, Childs M, Zimmermann A, Laithier V, Otte JB, de Camargo B, MacKinlay G, Scopinaro M, Aronson D, Plaschkes J, Perilongo G. Successful treatment of childhood high-risk hepatoblastoma with dose-intensive multiagent chemotherapy and surgery: final results of the SIOPEL-3HR study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28, 2584–2590. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4857.

- Zsiros J, Brugieres L, Brock P, Roebuck D, Maibach R, Zimmermann A, Childs M, Pariente D, Laithier V, Otte JB, Branchereau S, Aronson D, Rangaswami A, Ronghe M, Casanova M, Sullivan M, Morland B, Czauderna P, Perilongo G; International Childhood Liver Tumours Strategy Group (SIOPEL). Dose-dense cisplatin-based chemotherapy and surgery for children with high-risk hepatoblastoma (SIOPEL-4): a prospective, single-arm, feasibility study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14, 834–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70272-9.

- Brock PR, Maibach R, Childs M, Rajput K, Roebuck D, Sullivan MJ, Laithier V, Ronghe M, Dall’Igna P, Hiyama E, Brichard B, Skeen J, Mateos ME, Capra M, Rangaswami AA, Ansari M, Rechnitzer C, Veal GJ, Covezzoli A, Brugières L, Perilongo G, Czauderna P, Morland B, Neuwelt EA. Sodium Thiosulfate for Protection from Cisplatin-Induced Hearing Loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378, 2376-2385. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801109.

- Meyers RL, Maibach R, Hiyama E, Häberle B, Krailo M, Rangaswami A, Aronson DC, Malogolowkin MH, Perilongo G, von Schweinitz D, Ansari M, Lopez-Terrada D, Tanaka Y, Alaggio R, Leuschner I, Hishiki T, Schmid I, Watanabe K, Yoshimura K, Feng Y, Rinaldi E, Saraceno D, Derosa M, Czauderna P. Risk-stratified staging in paediatric hepatoblastoma: a unified analysis from the Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18, 122-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30598-8.

- Rangaswami AA, Trobaugh-Lotrario AD, Maibach R, O’Neill AF, Aronson DC, Meyers RL, Krailo MD, Piao J, Hiyama E, Hishiki T, Ansari M, Lopez-Terrada D, Czauderna P, Malogolowkin M, Häberle B. Validation of the stratification for newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma: An analysis from the Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC) database. EJC Paediatric Oncology. 2025 ;5:100206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcped.2024.100206.

- Schmid I, O’Neill AF, Watanabe K, Aerts I, Branchereau S, Brock PR, Dandapani M, Fresneau B, Geller J, Hishiki T, Ingham D, Kraal K, Ronghe M, Tiao G, Trobaugh-Lotrario A, Rangaswami A, Sullivan MJ, Zsiros J, Hiyama E, Malogolowkin M, Ansari M. Global consensus from the PHITT consortium surrounding an interim chemotherapy guidance for the treatment of children with hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular neoplasm—not otherwise specified (HCN-NOS), hepatocellular carcinoma and fibrolamellar carcinoma after trial closure. EJC Paediatric Oncology. 2025;5:100235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcped.2025.100235.

- Smeland S, Bielack SS, Whelan J, Bernstein M, Hogendoorn P, Krailo MD, Gorlick R, Janeway KA, Ingleby FC, Anninga J, Antal I, Arndt C, Brown KLB, Butterfass-Bahloul T, Calaminus G, Capra M, Dhooge C, Eriksson M, Flanagan AM, Friedel G, Gebhardt MC, Gelderblom H, Goldsby R, Grier HE, Grimer R, Hawkins DS, Hecker-Nolting S, Sundby Hall K, Isakoff MS, Jovic G, Kühne T, Kager L, von Kalle T, Kabickova E, Lang S, Lau CC, Leavey PJ, Lessnick SL, Mascarenhas L, Mayer-Steinacker R, Meyers PA, Nagarajan R, Randall RL, Reichardt P, Renard M, Rechnitzer C, Schwartz CL, Strauss S, Teot L, Timmermann B, Sydes MR, Marina N. Survival and prognosis with osteosarcoma: outcomes in more than 2000 patients in the EURAMOS-1 (European and American Osteosarcoma Study) cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2019;109:36-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.027.

- Salazar J, Arranz MJ, Martin-Broto J, Bautista F, Martínez-García J, Martínez-Trufero J, Vidal-Insua Y, Echebarria-Barona A, Díaz-Beveridge R, Valverde C, Luna P, Vaz-Salgado MA, Blay P, Álvarez R, Sebio A. Pharmacogenetics of Neoadjuvant MAP Chemotherapy in Localized Osteosarcoma: A Study Based on Data from the GEIS-33 Protocol. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Dec 12;16, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16121585.

- Palmerini E, Meazza C, Tamburini A, Márquez-Vega C, Bisogno G, Fagioli F, Ferraresi V, Milano GM, Coccoli L, Rubio-San-Simón A, Gallego O, Llinares Riestra ME, Manzitti C, Mora J, Vaz-Salgado MÁ, Luksch R, Mata C, Pierini M, Carretta E, Cesari M, Paioli A, Marrari A, Scotlandi K, Serra M, Asaftei SD, Gambarotti M, Picci P, Ferrari S, Valverde C, Ibrahim T, Broto JM. Is There a Role for Mifamurtide in Nonmetastatic High-Grade Osteosarcoma? Results From the Italian Sarcoma Group (ISG/OS-2) and Spanish Sarcoma Group (GEIS-33) Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43, 3113-3122. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-25-00210.

- Mora J, Castañeda A, Perez-Jaume S, Lopez-Pousa A, Maradiegue E, Valverde C, Martin-Broto J, Garcia Del Muro X, Cruz O, Cruz J, Martinez-Trufero J, Maurel J, Vaz MA, de Alava E, de Torres C. GEIS-21: a multicentric phase II study of intensive chemotherapy including gemcitabine and docetaxel for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma of children and adults: a report from the Spanish sarcoma group (GEIS). Br J Cancer. 2017;117, 767-774. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.252.

- Brennan B, Kirton L, Marec-Bérard P, Gaspar N, Laurence V, Martín-Broto J, Sastre A, Gelderblom H, Owens C, Fenwick N, Strauss S, Moroz V, Whelan J, Wheatley K. Comparison of two chemotherapy regimens in patients with newly diagnosed Ewing sarcoma (EE2012): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400, 1513-1521. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01790-1.

- Oberlin O, Rey A, Sanchez de Toledo J, Martelli H, Jenney ME, Scopinaro M, Bergeron C, Merks JH, Bouvet N, Ellershaw C, Kelsey A, Spooner D, Stevens MC. Randomized comparison of intensified six-drug versus standard three-drug chemotherapy for high-risk nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma and other chemotherapy-sensitive childhood soft tissue sarcomas: long-term results from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology MMT95 study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30, 2457–2465. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3287. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2025;43, 1398. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-25-00440.

- Bergeron C, Jenney M, De Corti F, Gallego S, Merks H, Glosli H, Ferrari A, Ranchère-Vince D, De Salvo GL, Zanetti I, Chisholm J, Minard-Colin V, Rogers T, Bisogno G; European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG). Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma completely resected at diagnosis: The European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group RMS2005 experience. Eur J Cancer. 2021;146:21-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.12.025.

- Ferrari A, Brennan B, Casanova M, Corradini N, Berlanga P, Schoot RA, Ramirez-Villar GL, Safwat A, Guillen Burrieza G, Dall’Igna P, Alaggio R, Lyngsie Hjalgrim L, Gatz SA, Orbach D, van Noesel MM. Pediatric Non-Rhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Standard of Care and Treatment Recommendations from the European Paediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG). Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:2885-2902. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S368381.

- Ferrari A, Merks JHM, Chisholm JC, Orbach D, Brennan B, Gallego S, van Noesel MM, McHugh K, van Rijn RR, Gaze MN, Martelli H, Bergeron C, Corradini N, Minard-Colin V, Bisogno G, Geoerger B, Caron HN, De Salvo GL, Casanova M. Outcomes of metastatic non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas (NRSTS) treated within the BERNIE study: a randomised, phase II study evaluating the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2020;130:72-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.029.

- Calaminus G, Frappaz D, Kortmann RD, Krefeld B, Saran F, Pietsch T, Vasiljevic A, Garre ML, Ricardi U, Mann JR, Göbel U, Alapetite C, Murray MJ, Nicholson JC. Outcome of patients with intracranial non-germinomatous germ cell tumors-lessons from the SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 trial. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19, 1661-1672. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox122.

- Calaminus G, Kortmann R, Worch J, Nicholson JC, Alapetite C, Garrè ML, Patte C, Ricardi U, Saran F, Frappaz D. SIOP CNS GCT 96: final report of outcome of a prospective, multinational nonrandomized trial for children and adults with intracranial germinoma, comparing craniospinal irradiation alone with chemotherapy followed by focal primary site irradiation for patients with localized disease. Neuro Oncol. 2013 Jun;15, 788–796. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/not019.

- Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, Stratton KK, Bishop K, Krull KR, Alfano CM, Gibson TM, de Moor JS, Hartigan DB, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Rowland JH, Oeffinger KC, Mariotto AB. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24, 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1418.

- Williams, AM; Liu, Q; Bhakta, N; Krull, KR; Hudson, MM; Robison, LL; Yasui, Y. Rethinking Success in Pediatric Oncology: Beyond 5-Year Survival. J Clin Oncol. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(20):2283. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01230. 2021, 39(20), 2227–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IARC Quality Indicators | Recommended values | RETI-SEHOP, 1999-2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopically verified cases (%) | 85-98 | 89.5 |

| Cases ascertained from death certificate only (%) | <5 | - |

| Proportion of unspecified cases (NOS %) * | <10 | 2.1 |

| Cases aged 0 years (%) | 5-15 | 10.9 |

| Non-malignant CNS cases (%)† | 20-40 | 32.7 |

| Diagnostic group | 5-year OS rate (%) [95% CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2003 | 2004-2008 | 2009-2013 | 2014-2018 | 2019-2022* | |

| I-XII. All tumours | 75.4 [73.9, 76.9] | 76.6 [75.3, 77.9] | 80.1 [79.0, 81.2] | 83.5 [82.5, 84.5] | 84.6 [83.4, 85.7] |

| I-XII. All tumours, malignant | 74.1 [72.6, 75.7] | 76.1 [74.8, 77.5] | 78.9 [77.7, 80.1] | 82.0 [80.9, 83.1] | 83.1 [81.8, 84.3] |

| I. Leukaemias | 75.8 [72.8, 78.7] | 77.8 [75.4, 80.2] | 82.1 [80.0, 84.1] | 86.7 [85.0, 88.5] | 86.6 [84.6, 88.7] |

| Ia. Lymphoid leukaemias | 79.9 [76.8, 82.9] | 83.0 [80.6, 85.5] | 84.7 [82.6, 86.8] | 89.2 [87.4, 91.0] | 89.8 [87.8, 91.9] |

| Ib. Acute myeloid leukaemias | 59.5 [51.5, 67.5] | 59.3 [52.8, 65.8] | 67.6 [61.3, 73.9] | 75.0 [69.3, 80.6] | 72.5 [65.6, 79.5] |

| II. Lymphomas | 86.4 [83.2, 89.6] | 87.7 [84.8, 90.6] | 93.1 [91.0, 95.2] | 94.0 [92.0, 95.9] | 94.4 [92.2, 96.5] |

| IIa. Hodgkin lymphomas | 94.6 [91.3, 97.8] | 94.0 [90.5, 97.4] | 97.6 [95.5, 99.7] | 97.3 [95.1, 99.4] | 97.8 [95.6, 99.9] |

| IIb. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (except Burkitt) | 75.7 [68.6, 82.7] | 78.4 [72.0, 84.7] | 88.7 [84.2, 93.3] | 87.0 [82.2, 91.7] | 87.7 [82.4, 93.0] |

| IIc. Burkitt lymphoma | 86.7 [80.6, 92.8] | 90.0 [85.4, 94.7] | 92.4 [88.4, 96.4] | 97.6 [95.3, 99.9] | 97.4 [94.5, 100] |

| III. CNS | 66.6 [63.1, 70.2] | 66.6 [63.5, 69.7] | 70.7 [68.1, 73.3] | 76.0 [73.6, 78.3] | 78.2 [75.6, 80.9] |

| III. CNS, malignant | 54.2 [49.6, 58.8] | 58.6 [54.7, 62.5] | 59.6 [56.2, 63.0] | 63.7 [60.4, 67.1] | 66.2 [62.5, 69.9] |

| III. CNS, non-malignant | 92.3 [88.7, 95.8] | 82.9 [78.7, 87.2] | 94.0 [91.7, 96.4] | 99.1 [98.2, 100] | 99.4 [98.6, 100] |

| IIIa. Ependymomas and choroid plexus tumour | 62.4 [52.3, 72.6] | 62.2 [53.1, 71.3] | 69.8 [61.9, 77.7] | 74.9 [67.6, 82.2] | 78.6 [70.6, 86.5] |

| IIIa. Ependymomas and choroid plexus tumour, malignant | 53.5 [41.9, 65.1] | 57.1 [47.0, 67.2] | 65.3 [56.3, 74.2] | 66.9 [57.6, 76.1] | 72.1 [61.9, 82.3] |

| IIIb. Astrocytomas | 79.9 [75.1, 84.7] | 78.4 [73.8, 82.9] | 85.3 [82.1, 88.6] | 84.7 [81.7, 87.8] | 88.5 [85.3, 91.7] |

| IIIb. Astrocytomas, malignant | 68.9 [61.6, 76.2] | 69.9 [63.3, 76.6] | 74.1 [68.5, 79.6] | 73.2 [68.2, 78.2] | 77.0 [71.1, 83.0] |

| IIIb. Astrocytomas, non-malignant | 94.7 [90.6, 98.8] | 89.7 [84.5, 94.8] | 98.1 [96.3, 99.9] | 99.6 [98.7, 100] | 100 |

| IIIc. Intracranial and intraspinal embryonal tumours | 47.5 [39.6, 55.5] | 54.4 [47.7, 61.0] | 49.5 [43.7, 55.3] | 52.9 [46.3, 59.5] | 63.6 [56.1, 71.1] |

| IIId. Other gliomas | 44.5 [31.3, 57.8] | 50.0 [40.7, 59.3] | 53.8 [45.8, 61.7] | 60.4 [53.1, 67.7] | 50.1 [42.2, 57.9] |

| IV. Peripheral nervous cell tumours | 72.2 [67.5, 76.9] | 73.6 [69.3, 78.0] | 75.7 [71.6, 79.8] | 82.3 [78.6, 86.1] | 85.1 [80.9, 89.3] |

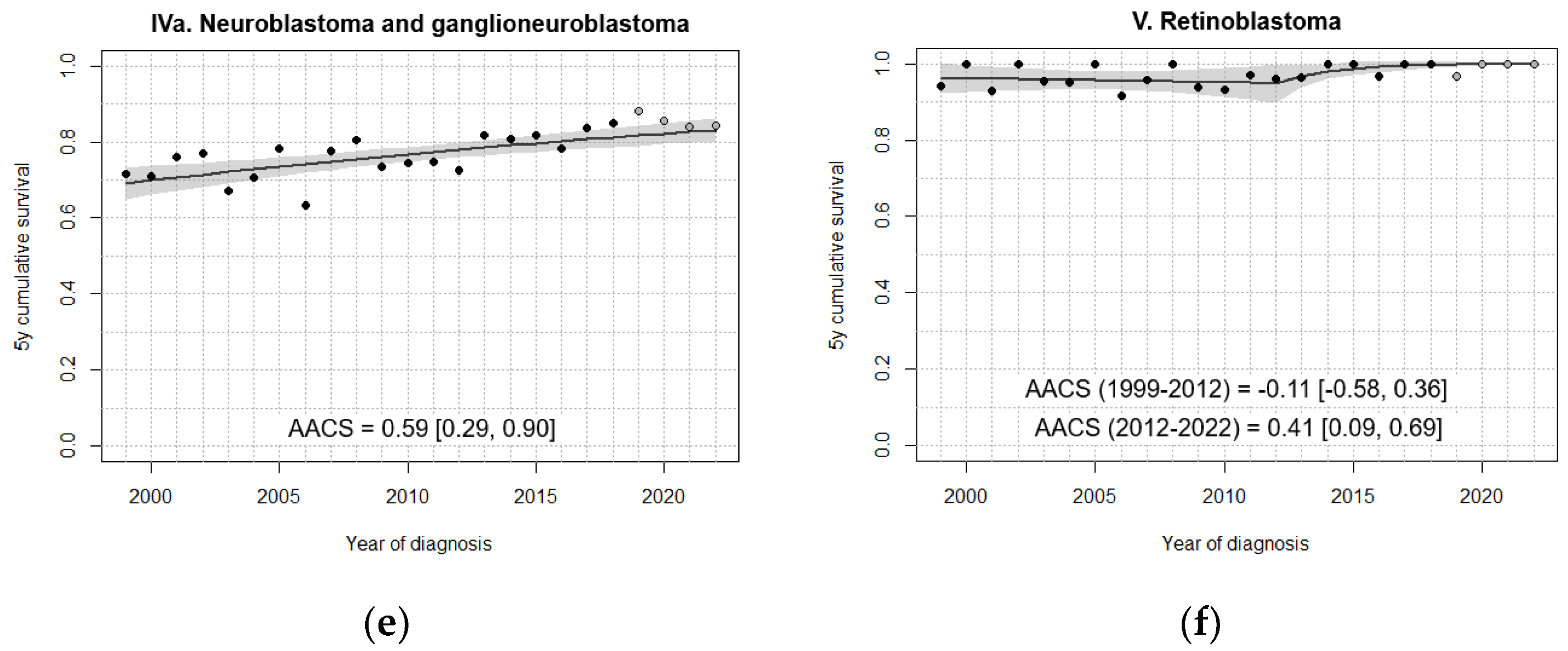

| IVa. Neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma | 72.1 [67.4, 76.8] | 73.6 [69.3, 78.0] | 75.5 [71.4, 79.7] | 82.0 [78.2, 85.8] | 84.9 [80.6, 89.2] |

| V. Retinoblastoma | 96.9 [93.4, 100] | 96.9 [93.9, 99.9] | 95.4 [92.0, 98.7] | 99.3 [98.0, 100] | 99.0 [97.2, 100] |

| VI. Renal tumours | 87.1 [81.6, 92.5] | 89.2 [85.3, 93.0] | 91.9 [88.7, 95.2] | 93.9 [90.9, 96.9] | 92.5 [88.8, 96.3] |

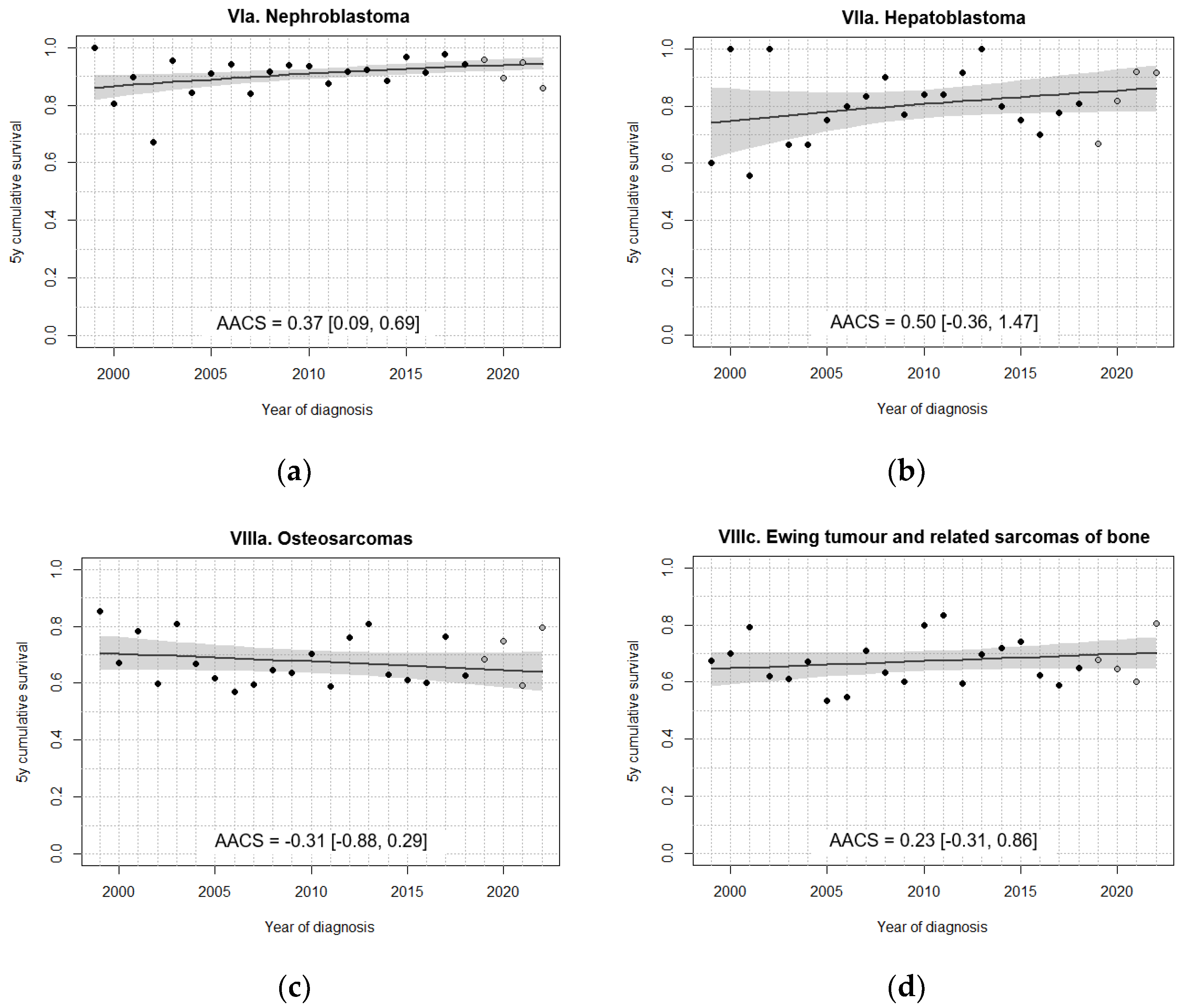

| VIa. Nephroblastoma | 86.7 [81.1, 92.3] | 89.0 [85.1, 92.9] | 91.8 [88.5, 95.1] | 93.7 [90.6, 96.8] | 92.8 [89.0, 96.6] |

| VII. Hepatic tumours | 69.2 [55.8, 82.7] | 75.1 [64.5, 85.7] | 86.1 [78.1, 94.1] | 74.8 [64.5, 85.2] | 79.8 [68.6, 91.0] |

| VIIa. Hepatoblastoma | 74.4 [60.7, 88.1] | 79.7 [69.4, 89.9] | 86.8 [78.8, 94.9] | 76.6 [65.5, 87.7] | 81.1 [69.3, 92.9] |

| VIII. Malignant bone tumours | 70.8 [65.0, 76.6] | 62.0 [56.1, 67.8] | 71.0 [65.8, 76.2] | 67.9 [62.8, 72.9] | 69.1 [63.4, 74.8] |

| VIIIa. Osteosarcomas | 72.8 [64.2, 81.4] | 63.0 [53.9, 72.0] | 69.8 [61.7, 77.8] | 65.8 [58.1, 73.5] | 69.0 [60.4, 77.7] |

| VIIIc. Ewing tumour and related sarcomas of bone | 68.2 [60.2, 76.3] | 61.8 [54.0, 69.6] | 70.5 [63.4, 77.6] | 67.2 [60.0, 74.5] | 66.2 [58.1, 74.3] |

| IX. Soft tissue sarcomas and other extraosseous sarcomas | 64.0 [57.6, 70.4] | 72.6 [67.1, 78.1] | 69.0 [63.8, 74.3] | 75.9 [71.1, 80.6] | 77.5 [72.2, 82.8] |

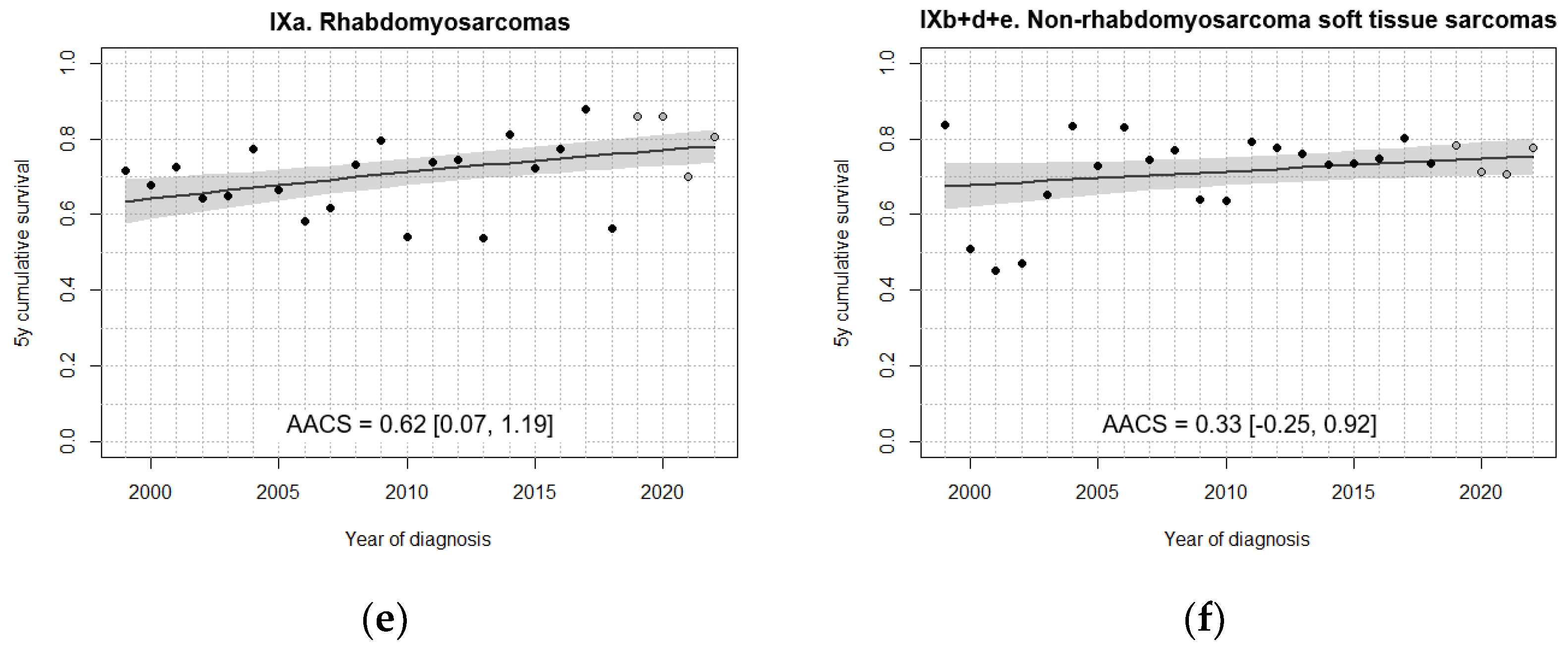

| IXa. Rhabdomyosarcomas | 66.5 [58.2, 74.8] | 67.9 [60.1, 75.6] | 67.3 [60.0, 74.7] | 77.5 [70.8, 84.3] | 78.8 [71.3, 86.4] |

| IXb+d+e. Non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas | 60.5 [50.4, 70.5] | 78.3 [70.8, 85.9] | 70.7 [63.2, 78.1] | 73.9 [67.1, 80.7] | 75.8 [68.1, 83.4] |

| X. Germ cell tumours | 84.1 [77.3, 90.8] | 86.4 [80.8, 91.9] | 93.4 [89.5, 97.4] | 89.8 [85.3, 94.3] | 96.3 [93.0, 99.5] |

| Xa. Intracranial and intraspinal germ cell tumours | 75.7 [61.9, 89.5] | 73.3 [60.4, 86.3] | 93.8 [86.9, 100] | 81.0 [71.3, 90.7] | 92.7 [84.7, 100] |

| Xb. Extracranial and extragonadal germ cell tumours | 80.0 [65.7, 94.3] | 86.5 [75.4, 97.5] | 86.7 [75.8, 97.6] | 90.2 [81.0, 99.3] | 93.9 [85.8, 100] |

| Xc. Gonadal germ cell tumours | 93.3 [86.1, 100] | 95.3 [90.1, 100] | 98.4 [95.3, 100] | 97.2 [93.3, 100] | 100 |

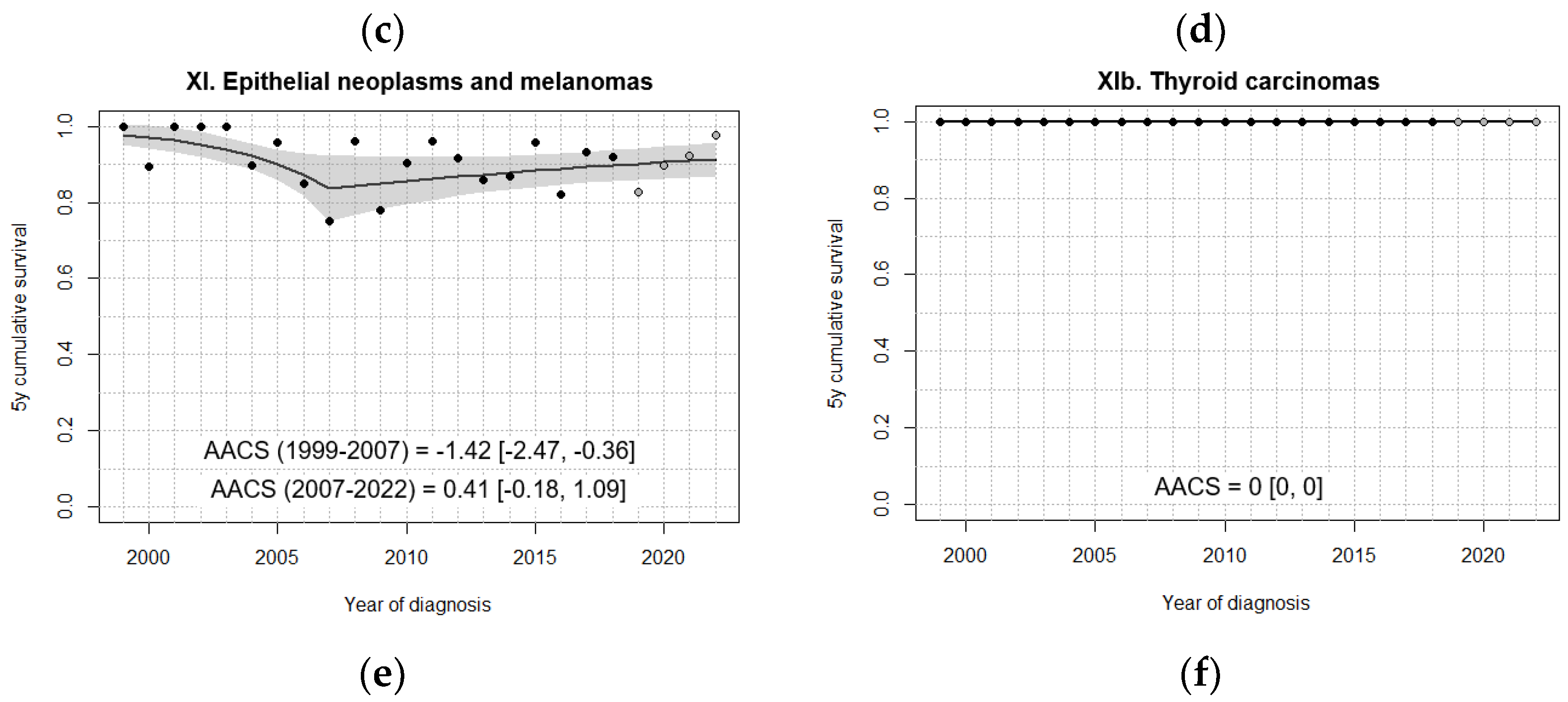

| XI. Epithelial neoplasms and melanomas | 98.3 [94.8, 100] | 90.6 [84.8, 96.5] | 88.1 [82.0, 94.2] | 90.7 [85.9, 95.5] | 89.8 [84.1, 95.5] |

| XIb. Thyroid carcinomas | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Diagnostic group | 5-year OS rate (%) [95% CI] | P log-rank |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 1-4 years | 5-9 years | 10-14 years | ||

| I-XII. All tumours | 81.4 [79.1, 83.7] | 83.4 [82.1, 84.6] | 81.3 [79.9, 82.8] | 80.5 [79.0, 82.0] | 0.02 |

| I-XII. All tumours, malignant | 80.7 [78.3, 83.1] | 82.4 [81.1, 83.7] | 79.5 [77.9, 81.1] | 78.8 [77.2, 80.5] | 0.005 |

| I. Leukaemias | 60.0 [52.2, 67.8] | 89.7 [88.0, 91.4] | 86.3 [83.9, 88.7] | 77.4 [74.1, 80.7] | <0.0001 |

| Ia. Lymphoid leukaemias | 55.8 [44.8, 66.9] | 91.6 [89.9, 93.2] | 88.5 [86.1, 90.9] | 78.8 [75.0, 82.7] | <0.0001 |

| Ib. Acute myeloid leukaemias | 61.1 [48.9, 73.3] | 74.8 [67.5, 82.2] | 74.2 [66.2, 82.1] | 70.3 [62.4, 78.2] | 0.2 |

| II. Lymphomas | 93.5 [90.0, 97.1] | 94.7 [92.5, 96.8] | 92.7 [90.6, 94.9] | 0.5 | |

| IIa. Hodgkin lymphomas | - | 98.2 [95.8, 100] | 97.0 [95.1, 98.9] | - | |

| IIb. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (except Burkitt) | 88.1 [81.2, 95.0] | 92.3 [87.9, 96.7] | 83.5 [77.6, 89.4] | 0.06 | |

| IIc. Burkitt lymphoma | 97.7 [94.6, 100] | 94.3 [90.7, 97.9] | 93.6 [88.7, 98.6] | 0.4 | |

| III. CNS | 63.4 [56.0, 70.8] | 74.0 [71.0, 77.0] | 71.1 [68.1, 74.1] | 79.0 [75.6, 82.4] | <0.0001 |

| III. CNS, malignant | 47.7 [38.3, 57.1] | 65.5 [61.7, 69.3] | 58.1 [54.0, 62.1] | 65.6 [60.4, 70.8] | <0.0001 |

| III. CNS, non-malignant | 94.6 [88.5, 100] | 96.9 [94.6, 99.2] | 96.1 [93.9, 98.2] | 97.8 [96.0, 99.7] | 0.5 |

| IIIa. Ependymomas and choroid plexus tumour | 51.5 [34.5, 68.6] | 67.2 [58.7, 75.8] | 81.0 [71.3, 90.7] | 86.7 [77.5, 95.9] | 0.0003 |

| IIIa. Ependymomas and choroid plexus tumour, malignant | 31.8 [12.4, 51.3] | 63.4 [54.1, 72.7] | 76.5 [64.8, 88.1] | 81.3 [67.7, 94.8] | <0.0001 |

| IIIb. Astrocytomas | 81.1 [70.6, 91.7] | 92.1 [89.3, 95.0] | 81.9 [77.9, 85.8] | 80.0 [74.6, 85.3] | 0.0001 |

| IIIb. Astrocytomas, malignant | 72.7 [57.5, 87.9] | 87.7 [83.2, 92.2] | 65.8 [59.1, 72.5] | 61.0 [51.9, 70.1] | <0.0001 |

| IIIb. Astrocytomas, non-malignant | 95.0 [85.5, 100] | 98.6 [96.6, 100] | 98.9 [97.4, 100] | 100 | 0.3 |

| IIIc. Intracr/intrasp embryonal tumours | 27.5 [13.7, 41.3] | 44.4 [37.4, 51.3] | 56.9 [49.7, 64.1] | 64.8 [54.5, 75.2] | <0.0001 |

| IIId. Other gliomas | 72.1 [63.0, 81.2] | 41.5 [33.2, 49.7] | 65.5 [55.9, 75.0] | <0.0001 | |

| IV. Peripheral nervous cell tumours | 92.3 [89.6, 95.0] | 68.1 [63.3, 73.0] | 63.2 [52.0, 74.5] | 86.4 [72.0, 100] | <0.0001 |

| IVa. Neuroblastoma/ganglioneuroblastoma | 92.3 [89.5, 95.0] | 68.0 [63.1, 72.8] | 62.1 [50.7, 73.6] | 82.4 [64.2, 100] | <0.0001 |

| V. Retinoblastoma | 97.6 [94.8, 100] | 97.0 [94.3, 99.6] | - | - | - |

| VI. Renal tumours | 89.5 [83.0, 96.0] | 94.7 [92.1, 97.3] | 91.4 [86.6, 96.3] | 91.3 [79.8, 100] | 0.3 |

| VIa. Nephroblastoma | 89.5 [83.0, 96.0] | 94.6 [92.0, 97.3] | 91.0 [85.9, 96.1] | 88.2 [72.9, 100] | 0.2 |

| VII. Hepatic tumours | 78.7 [66.3, 91.1] | 93.5 [87.3, 99.7] | 72.2 [51.5, 92.9] | 47.1 [23.3, 70.8] | 0.0002 |

| VIIa. Hepatoblastoma | 77.6 [64.7, 90.5] | 93.2 [86.7, 99.6] | 75.0 [53.8, 96.2] | - | - |

| VIII. Malignant bone tumours | 65.0 [50.2, 79.8] | 75.0 [68.8, 81.2] | 67.1 [62.4, 71.8] | 0.2 | |

| VIIIa. Osteosarcomas | - | 70.0 [59.8, 80.3] | 67.5 [60.8, 74.2] | - | |

| VIIIc. Ewing tumour and related sarcomas of bone | 66.7 [49.8, 83.5] | 76.6 [68.4, 84.8] | 64.9 [58.1, 71.7] | 0.1 | |

| IX. Soft tissue sarcomas and other extraosseous sarcomas | 68.3 [57.1, 79.5] | 74.2 [67.8, 80.6] | 76.5 [69.9, 83.0] | 69.3 [63.0, 75.6] | 0.3 |

| IXa. Rhabdomyosarcomas | 80.0 [62.5, 97.5] | 74.4 [66.8, 82.1] | 73.6 [64.6, 82.7] | 64.1 [52.7, 75.6] | 0.3 |

| IXb+d+e. Non-rhabdomyosarcoma STS | 63.3 [49.4, 77.2] | 72.0 [59.6, 84.5] | 80.1 [70.7, 89.4] | 71.6 [64.1, 79.2] | 0.1 |

| X. Germ cell tumours | 89.4 [81.4, 97.4] | 86.8 [78.2, 95.3] | 91.6 [85.6, 97.5] | 94.5 [90.5, 98.5] | 0.3 |

| Xa. Intracr/intrasp germ cell tumours | - | 89.4 [80.6, 98.2] | 90.5 [82.5, 98.4] | - | |

| Xb. Extracranial and extragonadal germ cell tumours | 89.1 [79.0, 99.2] | 82.0 [67.6, 96.3] | - | - | - |

| Xc. Gonadal germ cell tumours | 100 | 100 | 92.9 [83.3, 100] | 98.5 [95.5, 100] | 0.2 |

| XI. Epithelial neoplasms and melanomas | 70.4 [51.9, 88.8] | 89.2 [82.0, 96.3] | 92.8 [88.7, 96.9] | 0.003 | |

| XIb. Thyroid carcinomas | - | 100 | 100 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).