1. The Whole and Its Parts

“Jedes Sein wird uns nur durch sein Werden erkannt”: Every being can only be understood from its becoming, or how it came into being [

1]. This long-recognized thesis was popularized in the nineteenth century by the renowned German biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), who used it to defend Darwin's theory of descent and asserted that "every ontogeny is a recapitulation of the phylogeny of the life form in question" [

2]. However, while Haeckel’s conclusion was widely accepted, it was also questioned by many and eventually turned out to be a fallacy [

3]; but this falsification does not detract from the insightful relevance of the aforementioned statement.

To appreciate the particular line of reasoning in this essay, it is necessary to consider the background of the lead author as Associate Professor of medical anatomy and embryology. Throughout his career, these two scientific disciplines confronted him with an intrinsic paradox between the developmental process and the ‘product’ — the structural anatomy of the human body — yet at the time it would have been imprudent (and unnecessary) to take sides between these different views of humanity and the scientific premises that lie behind them. The idea of a developmental hierarchy, as expressed by Haeckel in the above slogan, namely that the process of

becoming in biology is conceptually superior to the phenomenon of

being (form), was thus still current in the author’s mind when joining the search for the ‘correct’ definition of fascia [

4], and the debate on whether fascia is a system, organ, or tissue [

5]; or perhaps none of these.

Upon graduating from medical school (1973) and beginning his teaching and scientific career, the combination of anatomy and embryology was still common in the Netherlands, with learned (human focused) institutes and laboratories well-established at the university’s medical faculties. Many decades later, however, it is still difficult to imagine why the intrinsic paradox of this combination was not generally recognized at the time, let alone perceived as problematic, and following more recent discussions it is clear that this ‘bug’ remains largely unappreciated. The combination of anatomy and embryology thus continue to embody the contradicting duality of “Sein” (being) and “Werden" (becoming).

This contradiction, however, is more methodological than factual because the anatomical method is inherently analytical (Greek, ανάλυση: breaking up). Here, the human body is conceptually broken into a set of component parts, and clearly thought of as such in the anatomical literature, and this is taken literally: the word

dissection means cutting up (Greek, ανατέμνω). Philosopher Daniel Dennett (1995) [

6] would undoubtedly have regarded this reductionist approach as a "good" one. This approach has led to the popular conclusion that the body as a whole should be considered as the spatial sum of its component parts, whether they are cells, tissues, organs, or systems. It is a conceptual model that has proven extremely successful in medicine, where the spatial construction of the human body can be manipulated, corrected, removed, and replaced.

As a teacher, one was expected to teach medical students that the human body is constructed from the parts that anatomists have dissected and analyzed, and anatomizing is a good term for this mental exercise. One could also consider it as the building-blocks doctrine, which implies that the body is a mere construction of parts: like a machine. The body is then the result — the product — of these assembled parts; and Dennett would undoubtedly have characterized this as a form of "bad reductionism". However, consider that almost every anatomy textbook begins with a chapter on the bony skeleton, even though — in reality — the skeleton is one of the final ‘products’ of body formation.

The

building-blocks doctrine is thus not a fact or observation, but rather, a mapping interpretation [

7]. It is NOT based on the factual reality of the processes that led to the creation or formation of the human body: because the study of embryonic development actually leads to the opposite conclusion. Of course, the conceptualization of the body as a machine — a structure that is composed of component parts — is not inherently problematic. From a medical standpoint, this model serves as a useful foundational framework for numerous medical procedures and interventions. The philosophical challenge of this mechanistic approach, however, lies in the potential misinterpretation of the conditions necessary for the

formation of a particular entity as the entity itself. The fundamental question is then whether the anatomical entity known as

the whole — in this case

The body — really is just the summation of its constituent parts.

The concept of

the embryo now offers a novel perspective on the human body. At no stage of (prenatal) development can one see that the whole arises as a collection of component parts. From the outset, the embryo demonstrates that there is an organized

AND organizing whole: the body/organism that differentiates itself into the aforementioned ‘parts’ through the processes of cell multiplication and tissue formation. The concept of differentiation is thus pivotal to understanding embryonic development and can be regarded as a significant phenomenon of

autopoiesis (self-creation

), whereby every living being exists within a process that unfolds over time [

8]. In this process, the body’s ‘parts’ (cells, tissues, organs, etc.)

differentiate themselves within the whole: the organism. The term also characterizes the self-organizing capacity of living beings.

The formation of the ‘adult’ body does not manifest itself as a set of anatomical systems and components, but is rather a lifelong sequential process of organizing and subordinating that led to the formation of organs, tissues and cells etc. This then suggests that human embryonic development does not simply commence with a cell, but rather that the single-celled zygote is

already a human organism. It is therefore imperative that the anatomical body is not regarded as a construction, like a machine, but rather that once we realize the activity-nature of a developing organism, we can see that the mature organism is also a

being-at-work (a fortunate translation of Aristotle’s term

Energeia) [

8,

9,

10].

3.0. How and From What Did Fascia, or ‘Fascial Tissue’, Originate?

So, what further insights might be obtained by applying Haeckel's thesis on the origin of forms to the study of fascia and connective tissue? From a phenomenological perspective, it is the identity of the mesenchyme that is most relevant to this subject. At the earliest stages of human development, the embryo can be regarded as a cellular structure with the morula and subsequent embryoblast composed almost exclusively of cells. During the second week following conception, the cells within the embryoblast differentiate and form two distinct cell layers — now designated as the epiblast and hypoblast — that together constitute the bilaminar germ disc. The phenomenon of cell ‘layering’ is thus an emergent characteristic that arises from this transformational process, with the epiblast and hypoblast representing the natural follow-on from embryoblast cell differentiation.

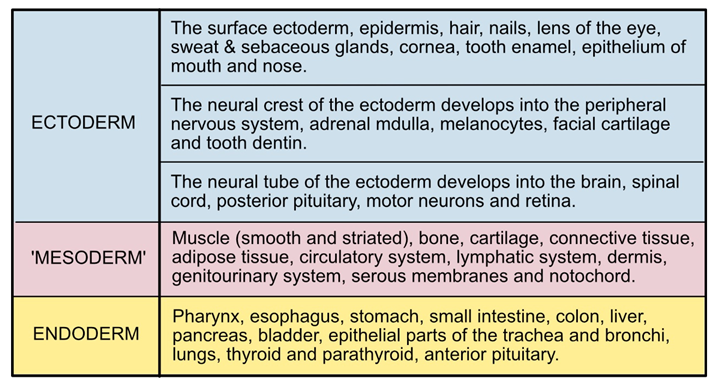

These two germ layers are then both considered as

epithelial tissues with the

ectoderm (epiblast) forming an outer ‘skin’: the substrate that subsequently develops into the epidermis and includes other derivatives such as the nervous system. The other,

endoderm germ layer (hypoblast), forms the inner ‘skin’ that subsequently develops into the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract and lung airways [

31], and which can (initially) be regarded as an epithelium with the gallbladder, liver, intestinal glands and some endocrine organs as its derivatives. Thus, in general, it can be posited that the cells within the organs derived from the ectoderm and endoderm will become predominantly parenchymatous, i.e., they fulfill what are generally considered to be the organ’s primary functions and represent a substantial proportion of the body’s cells. (At the same time, it is evident that there is much connective tissue associated with these organs, as well as blood vessels, joint capsules and lymphatic vessels).

3.1. The Inner-Tissue: Mesenchyme (Not the -Derm)

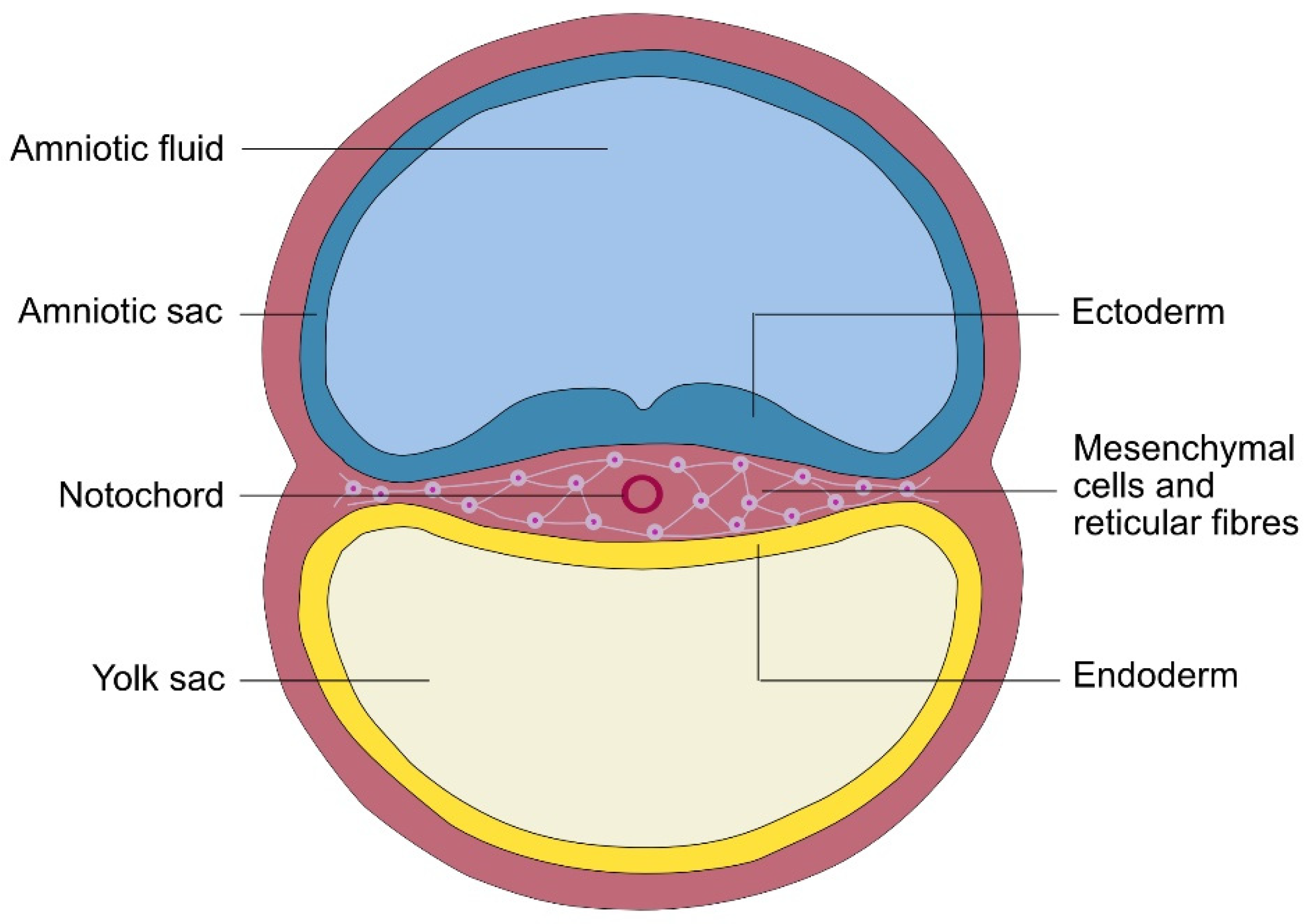

During the third week of human development, the initial mesenchyme becomes visible as a third germ layer, but which is of a completely different quality than the previous two (

Figure 1). So, while the ectoderm and endoderm can be rightly described as limiting, border or dermal (skin) tissues [

32], it is a falsity to apply this identity to the mesenchyme because it lies

between them, yet the erroneous term

mesoderm (‘meso-skin’) remains in common usage.

Virtually every embryology textbook asserts that the various organs of the body are derived from one of the three germ layers, and which are then widely regarded as equivalent units (

Table 1). So, the so-called germ layers are usually interpreted as the primary tissue elements of the human (animal) body and fit conveniently into the contrived

building-blocks doctrine, but the renowned German human embryologist Erich Blechschmidt (1904-1992) offers a different interpretation [

32].

The internal organization of most animals is characterized by a particular developmental feature: the formation of a parietal ('outer') body wall and a visceral ('internal') body wall, with the ‘limiting’ layers of ectoderm and endoderm as ‘precursors’. Blechschmidt referred to the ‘space’ between these limiting boundaries (‘skins’,

derms) as the

innerness, or

innermost (‘Innegewebe’ in German), and proposed that this characteristic feature of body organization is already manifest in the early (third week) embryo as the mesenchymal germ layer, which he described as

inner-tissue. Here, the duality of

ecto/endoderm and

mesenchyme,

boundary and

inner-tissue becomes differentiated into

parenchymal and

mesenchymal tissue, respectively, and further questions the “tripartite nature" of the early human embryo. [

34].

Phenomenologically, animals are essentially different from plant life by the formation of an ‘inner’ or internal space that manifests in anatomical, physiological, and psychological dimensions. The concept of sentience and consciousness in animals is predicated on the assumption that these creatures possess an autonomous inner-self that is capable of psychological independence from the external world. Blechschmidt is (to the authors’ knowledge) the only embryologist to allocate this novel concept to the three germ layers, and who regarded the ectoderm and endoderm as limiting (boundary) tissues, and the ‘mesoderm’ as the "

inner-tissue." For this reason, it is suggested that the mesoderm should no longer be considered as a ‘derm’ equivalent to the other two ‘layers’, but rather represents a different spatial dimension — the inner tissue or inner body — that connects and creates space. The ectoderm and endoderm are the limiting tissues (epithelia) that form a continuous boundary between the outer environment of the embryo, on the one hand, and the internal tissue on the other. Internal tissue is thus surrounded on all sides by limiting tissue and is therefore permanently

on the inside, i.e., IN the body. 'Inner-tissue' can then also be described as undifferentiated connective tissue: mesenchyme [

34]. It is thus a matter of intrigue that for multiple decades, the three germ layers were collectively referred to as a single entity, because it is clearly evident that the inner-tissue represents a distinctly separate dimension from the other two germ layers.

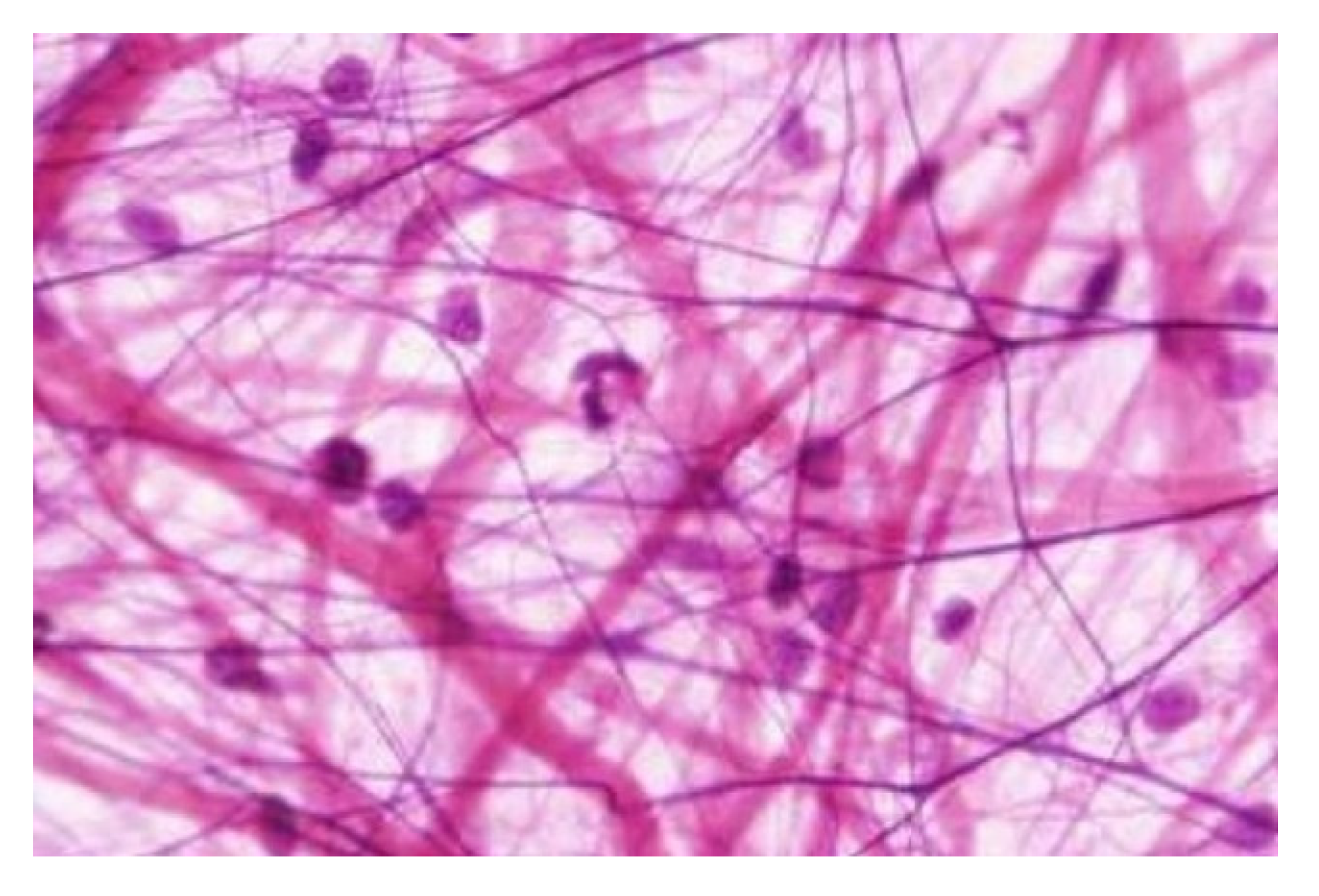

3.2. The Extracellular Matrix Ecm - Intercellular Space

Each of the mesenchyme-derived tissues and organs (of which there are many variations) is composed of the three principal constituents of the mesenchyme: cells, fibers and fluids (see

Figure 2). Here, the cells differentiate into specialized types that generate all the constituents of the so-called

extracellular matrix and

interstitium, and which surrounds them as a complex network of macro-molecules of collagen, elastin, fibronectin, proteoglycans and glycoproteins etc., and a wide range of soluble molecules. This tissue provides structural support, regulates cell functions (growth, movement and communication etc.) and facilitates tissue repair, thus acting like the body's scaffolding and chemical-signaling hub, etc. The fibers also provide a wide range of material qualities that span from

dense collagenous connective tissue to

loose elastic connective tissue.

The

interstitium also manifests itself as an intercellular

space within which the fibers undergo their formation and development [

35]. It consists primarily of fluid with varying degrees of viscosity that can vary from almost clear liquor to the more fibrous matrices of supporting chondroid and osteoid tissues, such as cartilage and bone tissue, respectively. Conversely, adipose tissue is characterized by its cellular component with the lipocytes replete with fatty substances and embedded within a loose fibrous network. However, the distinction between

extracellular matrix and

interstitium is really rather tenuous because the latter can also appear as a fibrous matrix, while the former can be more fluidic [

21]. The term

extracellular also clearly relates to something that is separate from the cells, while

intercellular space relates to a more inclusive reality.

3.3. Connection and Space

So, when we now look at muscles, the embryo, in its capacity to transcend the conventional categorization of four ‘fundamental’ tissues [

16,

19], clearly demonstrates that the concept of

muscle tissue is a variant or derivative of the original mesenchyme. It is then imperative to ascertain whether muscle tissue should also be considered as connective tissue. However, in this context, the term

connect is limited in its application.

The coelom from which the typical body cavities develop (e.g. peritoneal) is, in fact, an extensive fluid-filled interstitial space that can also be regarded as a ‘joint space’ between different tissues and organs that enables them to move against each other. Such spaces are thus characterized by a duality: they possess a separating dimension whilst simultaneously functioning as a connector. The latter can be interpreted not only functionally but also physiologically. It is imperative to consider the adhesion and contiguity that can develop between visceral organs and the visceral peritoneum (‘vacuum adhesion’). The concepts of connecting and creating space thus appear to have an enormous variety of manifestations, but can certainly be included within the basic functions of the mesenchyme because they encapsulate the intrinsic composition of the body, a category that is entirely absent in the anatomical building-blocks concept.

3.4. The Blood as Connective Tissue

As the early mesenchyme constitutes the space between the two body walls (ecto/endoderm), it establishes the environment conducive to the differentiation of cells into tissues and organs, and concurrently the mechanical and physiological connections between them. The degree of separation can vary from almost complete (articular joint space) to the physiological connection via blood and lymph vessels, among other possibilities. This then prompts a re-examination of the long-standing hypothesis that blood functions as a form of connective tissue. It has long been classified as such, and is clearly a derivative of the mesenchyme with capillaries as the fundamental structural elements of the blood tissue [

36].

The primary manifestation of capillaries is as an intricate network with an estimated combined length of up to 70,000 kilometers in the adult human body, and because they coexist with the mesenchyme throughout life, both can be described in terms that are NOT anatomical. Mesenchymal tissue may function as an

intermediary matrix and be regarded as the inner-tissue, with this concept of innerness predicated on the notion that this matrix engenders space, separation and connectivity and dos not fit in the

building-blocks concept. Both the ECM and blood facilitate the embryonic organization of differentiations throughout the body via epigenetic factors and enzymes [

37]. Capillaries emerge within specific embryonic regions that are concomitant with the mesenchyme, and as the organism undergoes further development, the capillaries become essential for traversing the spatial distances within the internal environment. There is thus a compelling argument for considering blood as a constituent and more dynamic form of the inner-connective tissue. The histological image of mesenchyme (

Figure 2) can then be interpreted as the

inner-self that the mesenchyme represents, and the archetype of the body matrix. The hypothesis is then posited that connective tissue, and by extension the fascia, functions as the inner-self.

4.0. Two Views on Fascia?

The first major anatomy book with which Andreas Vesalius (1543) [

38] ‘opened our eyes’ was with the analytical gaze of the scientific observer and entitled

De Fabrica Humani Corporis: On the structure of the human body. This seminal work offered a comprehensive analysis of the human body from a scientific perspective and set the future tone for considering the body as a construction: a scaffold, a factory of different systems and machines built up from parts [

39]. However, the fundamental question remained: “what is the initial manifestation of the inner space”? It is, of course, the same inner-tissue that manifests itself in the third week of human embryonic development, but the scientific concept under discussion has, in its initial phase, been predominantly anatomical or morphological in nature. However, as this discourse has progressed, it becomes increasingly plausible to consider the inner-tissue as a foundation for the psychological and physiological aspects of the inner-self.

It is argued that the human body is best conceptualized as a complex system intertwined with a delicate network of fibers, interstitial spaces and capillaries, in which organs are intricately connected to each other. The term

fascial web is employed to denote the fascia in a broader sense. The provision of space is imperative, as is the establishment of connections, the execution of multitasking in all locations, and, most crucially, the perpetuation of continuous connectivity among all elements. The term

ubiquitous matrix emerges and is characterized by its deviation from strict anatomical nomenclature. The duality of fascia can then be described as follows: it

conducts force and

enables movement, and it

provides space and

connects. The fascia can also be compared with a tensegrity system that possesses two dimensions, albeit in mechanical form, with the compressed struts creating a separation, and the tensioned cables creating a connection between them [

40]: a fundamental duality, or perhaps even polarity, of central and peripheral forces that are manifest in the inner-tissue of fascia [

41].

Fascia is thus more than just connective tissue, but rather a multifaceted structure or entity with unique properties and functions; and bone, muscle, blood, and lymph have all been conceptualized as manifestations of fascia because they have the same embryonic tissue origins [

42]. They also consist of cells, fibers, and a fluid interstitium/extracellular matrix; and it can be posited that such an architecture of force conduction and movement-enabling connective tissue exists throughout the body at various levels. The classic, dense, collagenous connective tissue that manifests in the body as fasciae, also manifests itself as aponeuroses, epimysium, subcutaneous fasciae, and dynaments [

5] etc. The huge variation in density and stiffness then implies that it cannot be conceptualized as a separate or distinct system, but functions as an intermediary (connecting and creating space) for example between the bony skeleton and the muscular system. So, should it be conceptualized as a separate anatomical system? That can be done but it would be a definition of fascia in a very narrow, namely

anatomical, sense,

In the context of fascia, it is imperative to acquire a comprehensive understanding that extends beyond mere physical location. The manner in which the fascial connective tissue interacts with its immediate surroundings is of particular relevance. The primary inquiry concerns the function of the element in question. Does it serve as a connecting tissue that transmits physical forces, or as a space-creating element that enables gliding/shearing mobility? This also means that defining

the fascia as a "layered body-wide multiscale network of connective tissue" [

16] and subsequently dissecting the whole into anatomical units, namely various fasciae that are together considered to form a fascia system, indicates at least an inner contradiction because this ‘ubiquitous’ principle is described in terms of a spatial construct of

building-block elements.

In the 1980s, Maastricht University (Netherlands) worked on dismantling the connective tissue into what were referred to as the Posture and Locomotion System (Footnote).

[Footnote: In Dutch and German anatomical literature, this designation is used rather than the reductionist terminology of ‘musculoskeletal system’]. At that time, this process had to be performed literally by a so-called 'sparing' dissection (recent computing methods can now provide virtual images of this process). The procedure entailed the removal of all ‘non-connective’ tissue, such as muscle and bone, in order to unveil the architectural organization of the connective tissue. The resulting connective tissue ‘skeleton’ was then conceptualized as an intermediary and complementary element between the muscle and skeletal elements, and referred to by various appellations appended to the term

fascia, such as

fascia antebrachii,

fascia lata, and

fascia perinealis. However, it was subsequently determined that this collagenous ‘connective tissue skeleton’ was continuous with the various periarticular connective tissue structures, such as ligaments and joint capsules; and it soon became evident that standard anatomical nomenclature of fasciae was functionally inadequate [

5,

26].

For example, the distal regions of the fascia antebrachii and fascia cruris are easily removed during the dissection process of ‘cleaning’, but the proximal region less so. The reason for this is that the distal portions form a local ‘gliding tissue’ between their respective muscles and tendons that allows them to adjust their positions in relation to each other. The more proximal fasciae, on the other hand, can be interpreted as aponeurotic force-conducting partitions that, in conjunction with intermuscular connective tissue partitions (e.g. septa), extend to all the underlying muscles of the forearm and lower leg.

The location of the fascia is thus as significant as the method by which it is connected to the surrounding and adjacent tissues; and because the focus of this study concerned the

architecture of the fascial layers, it fundamentally differs from the building-blocks notion of anatomy. Architecture is about the (functional) relationship between adjacent structures, while anatomy is about their location and locality; architecture therefore considered as complementary dimensions and principles. Van der Wal (2009) thus proposed the existence of ‘dynaments’ as architectural units of muscle

and connective tissue [

5]. In a recent article intended as a starting point for distinguishing a fascial system [

16], it is indicated that fascia or fasciae can have these two distinct functions in the

Posture and Locomotion System, yet the term

architecture appears only once.

The research conducted in Maastricht provided substantial evidence to support the hypothesis that the conducting dense collagenous connective tissue in the

Position and Locomotion System should not be regarded as anatomically distinct from, for example, muscle elements. In contrast, the findings indicated a greater prevalence of continuity with muscle tissue within the context of tensile force-conducting architecture. Consequently, the concept of a connective tissue skeleton should not be regarded as an additional component of the existing bone skeleton and muscular system. Rather, it should be understood as an intermediary that is functionally organized in relation to bone and muscle tissue. As previously mentioned [

43]: "A connective tissue skeleton or network, in essence, exhibits resistance to dissection and reduction. It can be regarded as a remedy for anatomical fragmentation, thereby preserving continuity." This connective tissue skeleton (or perhaps

fascial system) is not merely an additional organ or system. The representation of a separately dissected and ‘cleaned’ connective tissue skeleton of

fascia cruris, intermuscular septa, and

membrana interossea in the lower leg, as presented, for example, in the

Fascial network plastination project [

43] can thus be regarded as an artifact analogous to the ‘muscle man’ presented in many anatomical atlases (see

Figure 3).

So, two types of fascia could be defined. First: fascia in the ‘narrower’ sense as a fascial ‘system’ configured more or less as an anatomical or spatial organization that is in principle organized complementarily to other organs and tissues. Second: fascia in a ‘higher and broader’ sense: the ‘fabric’ of the body as the developmental follow-on (consequence) of the (third week) mesenchymal germ layer. In other words, fascia as the substrate of an interior or innerness of the body that /facilitates the physiological functioning of organs, and can even be thought of as the substrate of the psychological interior or inner (sentient) being.

5.0. Fascia as the Substrate of Interoception?

In numerous publications over the past several decades, fascia has been presented as both a sensory organ and the substrate of ‘interoception’ [

44,

45,

46], but a review of the literature reveals a lack of consensus on the definition of this particular form of perception (if indeed it can be considered as a ’perception’). The majority of descriptions of interoception are rooted in the perception or awareness of the inner state of the body, and are frequently associated with the internal organs, with many considering the concept of ‘fascial ubiquity’ to be fundamental to the field. Thus, in conjunction with the hypothesis that fascial connective tissue is the most densely innervated body substrate, the notion of fascia as the conduit for this awareness then emerges [

46]; but the distinction between proprioception and other related concepts is in this way becoming increasingly nebulous.

5.1. Proprioception

In classical neurophysiology, proprioception was specifically ‘localized’ in the tissues of the

Position and Locomotion System (aka musculoskeletal) and categorized as

statesthesia and

kinesthesia, respectively: the perception and awareness of the position and movement of the body and its component parts in space [

47]. However, the interpretation of the term

interoception as ‘inwardness’ does not fully align with the original tripartite classification system in neurophysiology, which was itself based on the (erroneous) three-germ-layers concept. Sensory receptors of many kinds (nociceptors, chemoreceptors etc.) are hypothesized to exist in the endodermal body domain and believed to generate information about the metabolic state of the visceral body. In contrast, the exteroceptors with their ectodermal origin, are specialized receptors that facilitate the perception of external stimuli such as sight, hearing, touch, and related sensory experiences. This categorization is then frequently encapsulated in popular discourse through the use of the term

interoception (perceptions derived from within the body) and

exteroception (those derived from the external environment). The figurative dimension that lies between these two extremes is then referred to as

proprioception.

However, the term

proprio is related to the concept of

own, or

self: a phenomenon that is further elucidated in the field of psychology, where the concept of proprioception has been increasingly intertwined with ‘body awareness’ and the concept of

body schema, and thereby linked to ‘interoception’. It thus appears that a distinction has been made between proprioception in the narrow sense (

statesthesia and

kinesthesia) and proprioception in the broader sense (

interoception and

body awareness). However, the Maastricht research contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the organization of proprioception in relation to the anatomy of the skeleton, joints, ligaments, and muscles [

24].

Proprioception, in the narrow sense (statesthesia and kinesthesia), refers to the senses or receptors through which one can perceive and experience the position, posture and changes of the body and its various ‘parts’; and includes mechanoreceptors, nociceptors and free nerve endings, yet the concept of these as proprioceptors is explicitly dismissed. The experience of posture and movement is then ‘processed’ by the brain (consciousness, ‘soul’) in order to derive meaning from the information received from the above receptors.

However, the research showed that the spatial organization of the substrate of proprioception was not aligned with specific anatomical units, such as muscles, ligaments and joints, but rather (and more logically) that the mechanoreceptors function on mechanical grounds rather than anatomical criteria. They are more related to the spatial organization and architecture of muscles and connective tissue; and this dual/polar pursuit of pressure and tension is also applicable to mechanoreceptors [

5].

Mechanoreceptors can be classified into two categories based on their sensitivity to deformation: tension-sensitive and pressure-sensitive. The aforementioned spatial organization, therefore, appears to be more related to lines of force and apparent gliding or assumed shear zones, i.e., to architecture rather than to classical anatomical units such as muscles and joints. The spatial organization of the fascia, in a narrow sense, thus facilitates force transmission and the motion of one part in relation to another. Therefore, when considering the localization of the sensory nature of the fascia, it is more beneficial to focus on the

manner in which this localization occurs rather than its

specific location. The most significant finding of this research was thus that the architecture of the connective tissue (rather than the anatomy of bones, joints, and muscles) proved instrumental to the organization of proprioception; and that the distinction between muscle receptors and joint receptors is then rendered obsolete [

5]

5.2. The Inner-Self

It is widely acknowledged that every individual possesses an inner-self, and it is also crucial to recognize animals as sentient beings, despite the fact that we are unable to directly experience this phenomenon in the latter. So, while the concept of the inner-self encompasses both psychological and physiological dimensions, the question remains over whether this inner-self is localized, or localizable. In the field of psychology, the concept of proprioception refers to a rather vague anatomical entity: the ‘inner-self’ or ‘the body’; and conversely, in the domain of (neuro) physiology, proprioception specifically pertains to the function of stature, movement, and balance. The subjective nature of the inner-self, or inner-being, however, precludes its objective measurement or documentation, which means that interoception cannot be categorized as a sensory perception; but rather, a component of consciousness and sentience, and therefore a sensation: an experience (not perception). The term interoception is thus not applicable.

Proprioception (defined as the sense of posture and movement) is distinct from other sensory experiences. It involves the perception of one's own movement based on information from the mechanoreceptors, nociceptors and free nerve endings in the skin etc. An individual can then possess a distinct awareness of the exterior of their body, and which can be characterized as an external perception or sense-of-self-as-observer. This phenomenon does not then pertain to the individual's intrinsic psychological makeup, but rather to the domain of consciousness. The experience of self-awareness, in addition to physical-body awareness, is inherently intrinsic and precludes the possibility of sharing by another individual. So, while contemporary scanning devices have become sophisticated enough to interpret cognitive processes with a high degree of accuracy, they lack the capacity to actively experience the thoughts of an individual.

In summary, it is evident that the traditional three-germ-layer model has long been considered as a fundamental paradigm in the field of psychology, but it is not as straightforward as initially believed. At the beginning of the last century, physiologists such as Charles Sherrington [

48] developed a theoretical framework that delineated three levels of sensory perception. These levels were based on a spatial arrangement of

enteroceptors that related to the endoderm,

exteroceptors related to the ectoderm, and

proprioceptors related to the intermediate area of the so-called 'mesoderm'. Enteroceptors were associated with the biochemical metabolic processes that occurred within the body, while exteroceptors involved perception of the external environment: seeing, hearing, touching and similar senses. Proprioception was thus unambiguously reserved for the tissues and organs involved in posture and movement, or ‘self-moving’; and it is evident that this tripartite division signifies the concept of ‘

intero’ in a manner that differs from the concept of mesenchyme as inner-tissue.

The aforementioned concept (

Section 3.1) posits that mesenchyme can be regarded as the

inner-tissue, and thereby expands the conception of proprioception beyond the sensory confines of posture and movement; and this approach encompasses a broader spectrum of psychological concepts that include body-schema and the inner-life. In a significant portion of the extant literature on fascia, the concept of interoception (enteroception) is employed, but psychology could just as easily utilize the term proprioception. In this context, however, it may be advantageous to distinguish between a broad, general conception of the

inner and a more limited, technical understanding that specifically relates to statesthesia and kinesthesia (

Section 5.1).

In recent publications, an increasing number of authors have referred to fascia as the ‘ubiquitous’ coherent network of connective tissue, thereby suggesting that it may serve as the substrate of the inner-self; and in the richest sense [

46], the foundation for our introspective awareness of the self. However, it is important to note that the concept of the inner-self, and consciousness as its akin, cannot be perceived or measured objectively because both of these phenomena are experiential in nature and do not fall within the purview of anatomical categories. The concept of the inner-self does not originate from anatomical principles, or dimensions equipped with sensory receptors that relay its presence to the brain (insula), as exemplified in enteroceptors that detect and communicate the physiological state of the gastrointestinal tract to this organ. This

building-block concept suggests that the brain is responsible for processing information about its internal and external environment, and serves as the central regulatory and perceptual organ of the body,.

However, consciousness and perception of the self and body are not measurable quantities that can be determined by receptors. So, while there are no

proprioceptors, there

are receptors that can transform a variety of stimuli (including mechanical) into information that the brain can use as a basis for perceptions and consciousness. Consciousness and awareness (dimensions of ‘mind’) are experiences of the first-person, while their correlation with brain-activity (dimension of ‘body’), is a reality of the third-person; and although the two are closely linked, they cannot be considered as homologous [

49]. Similarly, interoception is composed of information from different kinds of receptors that are then experienced, or translated, by the brain as an experience of the mind or soul. The concept of interoception is acknowledged, but its reality remains unconfirmed. Furthermore, the quantification of innervation density within fascia has evolved into a comparative calculation, but the quantity and density of the receptive substrate does not, in and of itself, offer any insight into functionality [

46]. As demonstrated in previous studies, the calculated density of muscle spindles per muscle offers no indication of functionality; and in this case, the question of "where" is less significant than the question of "how."

6.0. Final Considerations

According to the traditional anatomical concept, the body is the result of its component parts and organs: the building-blocks doctrine. However, if one were to examine this concept more closely, it would seem that there is nothing that holds all those organs together unless one looks for something like fascia, connective tissue or mesenchyme to perform that function. The hypothesis that everything is interconnected presupposes the concept of ubiquity, but from a philosophical perspective, it is inconsistent to first analyze the body in its entirety and then assign a specific function to another part, organ or system that serves to integrate and unify those component parts. Here, the components and the entity as a whole exhibit a dualistic relationship characterized by polarity rather than a mere relationship of either/or. The inclination to ascribe this capacity or attribute to fascia, for instance, is then pursued in conceptual frameworks such as ubiquity, network, and body-wide. However, as previously discussed, anatomical knowledge in this context is unable to offer useful insights into functionality. It thus appears to be a more rational approach to consider the body's internal structure as the underlying foundation upon which the various organs are interconnected and form a unified entity.

The attribution of qualities such as

innerness,

cohesion and

spatial organization to mesenchyme — Blechschmidt's

inner-tissue — does not in itself imply that connective tissue, fascia and (in a broad sense) wholeness of the organism are represented. It is the three germ-layers that together constitute the entire body (

Figure 1,

Table 1) with two of them forming the (endo/ecto) walls and boundaries with the external environment, while the third ‘layer’, which is not really a germ-layer but rather the mesenchyme, represents the innerness. The process of differentiation is then the fundamental mechanism that gives rise to the diversity of all possible organs and derivatives.

This assertion likewise pertains to fascia in its narrow sense. For instance, within the

Position and Locomotion (musculoskeletal) system, one may conceptualize an uninterrupted continuity that extends from the periosteum, traverses the epimysium and perimysium, and culminates at the subsequent periosteum; and this continuity can be revealed, for example, through the performance of a connective tissue-sparing dissection. Conversely, both bone tissue and bones, as well as muscle tissue and muscles, can be regarded as derivatives of that inner-tissue [

42]. In a broader sense, the fascia leads a kind of hidden existence. It is present everywhere, connecting everywhere and creating space, but does not function as just another system or organ that, amongst other things, simply provides cohesion.

A logical (and morphological examination) reveals that connective tissue, muscle tissue and blood tissue are, in fact, manifestations or components of the inner-tissue. Connective tissue can thus be considered as a distinct type of inner-tissue, but these two terms are not synonymous because

inner-tissue is a more comprehensive category than

connective tissue. The fascia, in its broadest sense, refers to the ‘hidden’ fascia, which is defined as the inner-tissue and its underlying architecture. In contrast, the fascia in a narrow sense is simply reduced to an architecture of connective tissue that manifests itself in various forms. Thus, in essence, the term

internal tissue denotes a broader category than

connective tissue, as it encompasses not only the presence of fibers but also the interstitium, which involves the formation of cavities filled with body fluids and ECM. Additionally, it includes capillaries that facilitate the circulation of blood (

Section 3.2).

6.1. Therapeutic Relevance

This is the juncture at which we may once again turn our attention to the questions that representatives of the various therapeutic disciplines within the

Fascia Research Society have asked. Here, some of these practitioners sought to identify a particular

fascia that does not appear in standard anatomical atlases. Another group sought scientific validation for the substrates they address within their Pilates, MELT and myofascial treatment modalities etc., while the aforementioned article by Stecco et al. (2025) [

16] endeavored to delineate the fascia in a comprehensive and thorough manner, but which is basically an anatomical analysis of a

fascial system in the narrow sense described here. The musculoskeletal system and the skeletal system have traditionally been the primary focus of classification and construction with anatomical knowledge providing a significant framework, and although recent developments have led to the integration of a connective tissue system that expands the scope of these studies, all the above align seamlessly with the

building-blocks concept as a foundational principle of anatomy. However, fascia in the broader sense discussed in this essay appears to be of a different order.

It is, of course, conceivable that this fascia — the ubiquitous ‘hidden’ fascia or web of inner-tissue in the human body — is really what most complementary therapists in the fascia research community (osteopaths, fascial therapists, Rolfers etc.) are looking for. In the context of anatomical, physiological and psychological enquiry, the concept of inner-life can be defined as the domain wherein the founder of Osteopathy (A. T. Still,1899, p. 61) [

50] localized the “soul” (Footnote), and a similar notion is elaborated on by Ida Rolf, who characterized it as the “Fascia is the connecting line between the psyche and the soma”.

[Footnote: Andrew Taylor Still: “The soul of man, with all the streams of pure living water, seems to dwell in the fascia of his body” [

50].

However, this approach is no longer tenable in the contemporary context, where the terms soul and spirit have become increasingly synonymous with consciousness and led to a paradigm shift in which these concepts are often viewed as being closely associated with the substrate of the brain. It is precisely in the context of the soul that the concept of ubiquity can be posited and supersedes the notion of locality in specific organs or anatomical regions, and this phenomenon can also be observed in the context of consciousness. It is thus important to consider whether there are more gradations and levels of consciousness beyond those that apply to our cerebral functioning, namely waking- and self-consciousness; but then we move into a different field than the one this article was exploring, namely the substrate of the mind and inner-self.

This line of thinking ultimately reverts to the definition of ‘

a fascia’ and that of ‘

the fasciae’ [

12]. The term

fasciae has been recognized since antiquity and is characterized by anatomical distinctiveness and clear definitions, as evidenced by numerous sources [

13,

51]. The organization of body fasciae has also been conceptualized as a system, though the nature of this ‘system’ remains to be elucidated because the enquiry pertains to the nature of

connective tissue. However, the term

connect is ambiguous and requires further elucidation to ensure a comprehensive understanding; and it is imperative to determine whether the creation of space is also regarded as a component of connective tissue. The functionality of muscle tissue must also be considered in relation to its capacity to function in a manner analogous to that of fascial tissue, while the often-quoted tensegrity model becomes more useful when the elements of such a system that connects and conducts tension are appreciated beyond just muscles, bones and connective tissue [

40].

The inner-tissue is characterized by an intrinsic polarity of connecting and separating, central and peripheral forces; yet it appears that therapists who sought to identify the fascia as a system, organ or organizational principle have found a satisfactory answer in the anatomists' efforts to categorize the fasciae of the body as an anatomically functional system. The existence of both concepts is not mutually exclusive, but rather, they coexist in two forms: a narrow and a broader sense..

6.2. Different Perspectives

The anatomical body is not generally considered as a whole, but rather regarded as a collection of parts. This entity is then regarded as the aggregate of its constituent elements with the whole being the summation of its parts, but the anatomical body is not merely a container for the functioning of its constituent organs. In this sense, the anatomical body could be considered as ‘empty’, and there is an absence of anatomical or physiological innerness, or interior, in which the organs are organized or embedded. Conversely, the opposite is observed in the embryonic body. From the outset, the embryonic body is a whole in which the organs differentiate and are interconnected, but the incorporation of fascia (a form of connective tissue) as a constituent element that fosters cohesion, does not inherently result in the formation of an interior. Nevertheless, it is regarded in this essay as the organ of innerness.

The mesenchyme, otherwise known as the

inner-tissue, is considered to be the third germ layer, and the internal space within which organs differentiate and cohere. The increased cohesion within the anatomically defined fascial system can then be considered as a pseudo-cohesion. The fact that the fascial system, as recently defined [

13,

15], is present everywhere and provides cohesive connections does not, in itself, make the body a whole. It is not scientifically tenable that the body is made up of parts, and that there is a specific organ or system that connects other parts and thereby forms a whole, or to paraphrase George Orwell in

Animal Farm: “All organs are equal, but one organ is a little more equal than the others”.

The connective tissue skeleton described by those who attempt to formulate

a fascial system actually has much more of the character of

intermediate anatomy rather than architecture. Architecture is predicated on the notion that the parts of a structure refer to the spatial organization in

context, and is a trans-anatomical principle that transcends anatomy. In the context of a

fascial part or

fascial organ, the importance of its anatomical location is less significant than the functional relationship to its environment, because spatial organization is a defining relationship that extends beyond mere anatomy. Recent definitions of the fascial system may then be adequate for therapists/practitioners who deal in simple terms of connective tissue, muscle tissue and myofascial structures, but perhaps not those who seek to scientifically demonstrate the substrate of fascia as a psychosomatic dimension of the inner-life. It is thus likely that many will recognize the broader concept of fascia presented here because it easily integrates with the underlying philosophy of osteopathy, and Still’s (1899) assertion that "The soul of man… seems to dwell in the fascia of his body” [

50,

52].

6.2.1. The Morphological Chameleon

The fascia is thus a morphological chameleon: an all-rounder that adapts to its environment through connecting and separating, filling and providing firmness, whilst at the same time being fluid. It is 'everywhere', it connects and it creates space. It 'mediates', in a mechanical way and enables movement through its spatial organization. On the one hand: anatomy, on the other, not; and as Levin (2022) put it: " Fascia is the fabric of the body; not the vestments covering the corpus, but the material that gives it form: the warp and the weft” [

53].

As mentioned previously, one can work with the fascial system (in a narrow sense) because it does justice to the anatomy of fasciae, as described in innumerable textbooks, and fully legitimizes this anatomical view. However, seeing this fascial system as a differentiation and specialization of the fascia in a broader sense that represents our inner domain or organ of inner-self, once again indicates that in order to understand the anatomy, one must also have knowledge of the becoming and emergence of this spatial organization. Each of our beings can only be understood from the perspective of becoming.

6.2.2. The Truth?

Ultimately, the conclusion of this essay boils down to a Solomonic judgment. It is impossible to consider either of the two categories as "the true" one. Both categorizations and both insights are apparently valid. However, while the more reductionist categorization (fascia as a spatial system of connective tissue structures) fits into the more holistic categorization (fascia as the web and matrix of the body), the same cannot be said in reverse. The rule that becoming explains being, and not the other way around, remains. The embryonic truth precedes the anatomical truth, but it is also both, because one cannot exist without the other.

The above considerations thus seem to imply a dichotomy related to the existence of a so-called first-person fascia (the experienced ‘hidden’ fascia as the 'fabric of the body') and a third-person fascia (the fascia as an ‘anatomical system’). This terminology is derived from neurophysiology, where it must also be accepted that a form of Cartesian split remains between the reality of the brain of the third-person and the reality of consciousness as experienced in the first-person [

49]. All too often, the

lived anatomical reality conflicts with the

studied anatomical reality. This dichotomy can be resolved or transcended when we expand the anatomical

building-blocks concept with a more fascia-centered interpretation of architectural anatomy that, for example, maps bones and muscles in a completely different way from traditional anatomical models. The embryo-approach heals and complements the analytic anatomical approach, does not deny it.

This last notion is argued in a recent article with the telling title:

Moving Beyond Vesalius: Why anatomy needs a mapping update [

7]; and following the same lines of thought, a revaluation of conventional (abstract) classifications of connective tissues similar to those presented in this essay [

21]. Where the existence of an architectural framework of tensioned fibrous tissues that encompasses a complex body-wide heterarchy of space-filling compartments under compression, now reasserts the broader significance of the fascial connective tissues. It thus seems that the long search for the ‘correct’ definition of fascia leads to a situation in which no consensus can be reached: a situation in which no single absolute 'trusth' emerges, and intrinsically contradictory concepts coexist. Referring to the subtitle of this article, a traditional approach to an appreciation of fascia as anatomical and as dissectible into its component parts; and a phenomenological one that is not about anatomy and locality but about wholeness and ‘everywhereness’ (ubiquity), and therefore not dissectible.