1. Introduction

Maritime shipping is the backbone of modern trade, and the container is the physical unit that makes global logistics predictable and scalable.

When a container’s contents are misdeclared, the failure is not only administrative, because the wrong cargo can ignite, react, leak, corrode containment, or disable fire suppression on a vessel.

Industry reporting and recent incidents have linked a meaningful share of shipboard fires to undeclared or misdeclared dangerous goods, including batteries and flammable chemicals [

1,

2].

Ports and carriers respond with layered controls, including shipper vetting, document review, and non-intrusive inspection (NII) imaging for selected containers.

Those controls are effective when they work together, but they often operate as separate systems with different owners, different data semantics, and different thresholds.

The result is a gap between what the scan suggests, what the paperwork states, and what the operator can confidently decide in a short decision window.

This gap is where multimodal AI is a natural fit, because it can learn cross-checks between physical signatures and declared descriptions in a way that simple rules and single-modality models cannot.

DHS has articulated an “AI-enabled paradigms” view of non-intrusive screening that emphasizes integrated workflows, decision support, and the use of multiple signals rather than a single sensor [

3].

At the same time, the shipping industry is deploying AI screening on booking data to identify misdeclared and undeclared high-risk shipments before loading, paired with common inspection standards [

1,

4].

These trends point to a clear opportunity: build an end-to-end framework that connects port-side NII signals with carrier-side document intelligence so that risk is detected earlier, acted on consistently, and learned from over time.

This paper focuses on hazardous misdeclaration in maritime containers because the impact is measurable in fires, claims, operational delays, and safety outcomes, and because ports already collect the core signals needed for improvement.

The contributions include a modular multimodal architecture, a practical feedback-driven data lifecycle, an edge-first deployment pattern for low-latency operations, and an evaluation protocol based on recall at fixed false-alarm budgets.

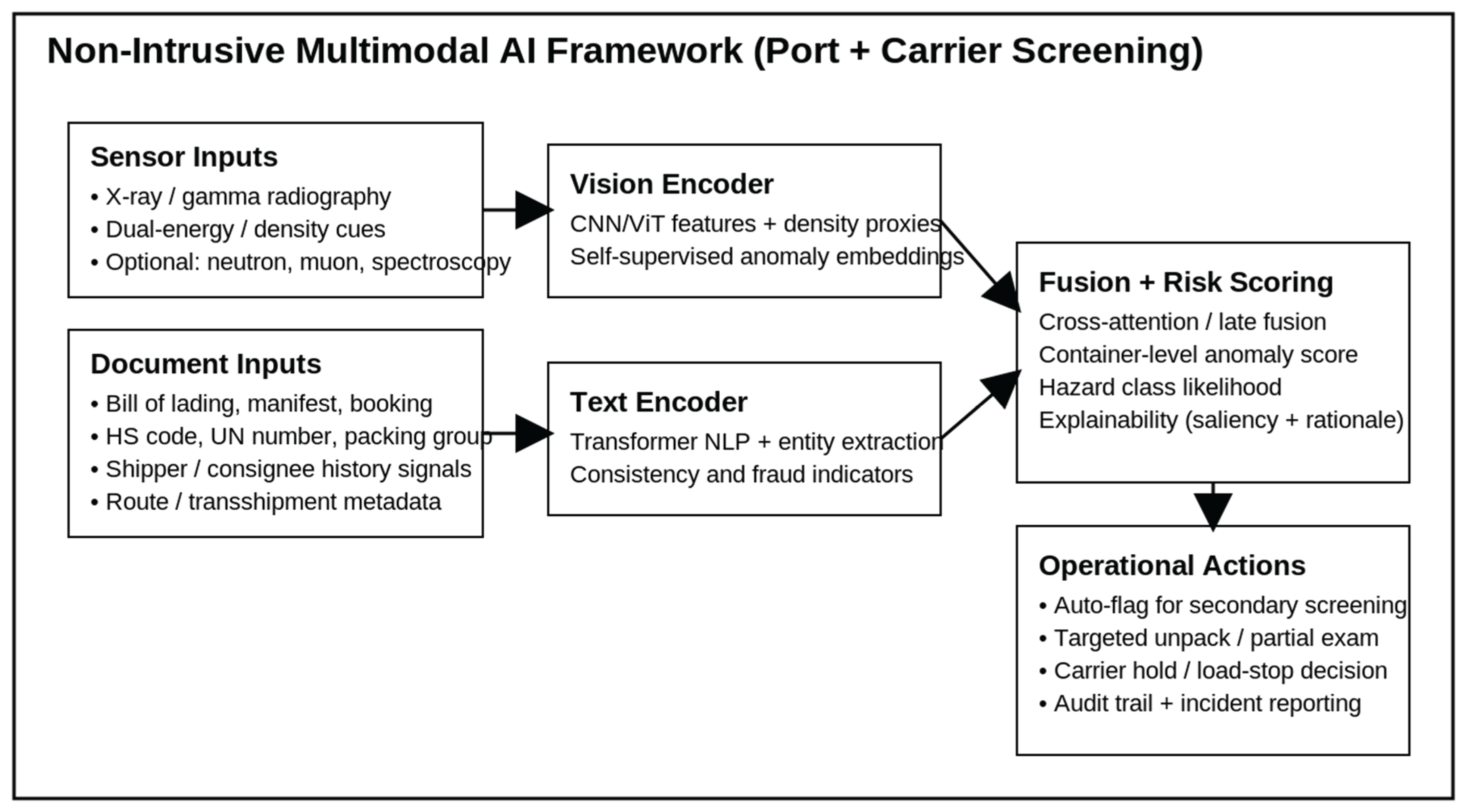

Figure 1.

High-level architecture that fuses NII imaging and shipping documents for container-level risk scoring and operational actions.

Figure 1.

High-level architecture that fuses NII imaging and shipping documents for container-level risk scoring and operational actions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Automated Analysis of Cargo Radiography

Automated analysis of X-ray cargo imagery has been studied for over a decade, but it remains challenging because cargo images are cluttered, vary widely by commodity, and include dense occlusions.

Early work framed the problem as an inspection challenge and explored machine learning pipelines for tasks like empty container verification and threat object detection [

5].

Surveys described the field as comparatively immature relative to medical imaging, noting that limited labeled datasets and high variability slowed progress and complicate deployment validation [

6].

A key issue is that the “normal” class is extremely broad, because legitimate trade includes almost every shape, density, and packing pattern imaginable.

For that reason, many researchers shifted from closed-set classification toward anomaly detection, where the model learns what is typical for a lane or commodity segment and flags unusual deviations.

Representation-learning and patch-level anomaly detection have been explored as a way to detect deviations from normal cargo patterns without needing labels for every threat [

7].

A recent self-supervised framework for X-ray cargo anomaly detection and localization shows strong generalization to novel anomalies, which is relevant for misdeclaration scenarios where threats evolve [

8].

Modern object detectors are also being adapted for contraband detection in security images, including improvements based on contemporary YOLO variants [

9].

2.2. Document Intelligence and Trade Fraud Analytics

Customs and trade communities have studied how machine learning can support detection of strategic goods and suspicious trade patterns using declaration attributes and bill of lading signals [

10].

Fraud analytics often focuses on misclassification, valuation anomalies, route risk, and mismatches between description and statistical norms.

Work on goods misclassification and HS code assessment suggests that textual product descriptions and taxonomy structure can detect inconsistencies and support improved classification [

11].

In the maritime domain, document fields are frequently incomplete or noisy, and a model must be robust to shorthand, spelling errors, and deliberate vagueness.

2.3. Industry and Government Context

Industry adoption is accelerating, with the World Shipping Council launching a cargo safety program that uses AI-powered cargo screening combined with common inspection standards to identify misdeclared and undeclared high-risk shipments before loading [

1,

4].

DHS has published guidance describing AI-enabled paradigms for non-intrusive screening, including the idea of extracting more value from sensor data and integrating multiple signals into decision support [

3].

What remains less developed in the open literature is an end-to-end multimodal framework that explicitly fuses port-side NII imaging with carrier-side document intelligence for hazardous misdeclaration in containers.

3. Problem Definition and Threat Model

We define a hazardous misdeclared container as a container whose physical contents include goods that meet dangerous goods criteria but are declared as non-hazardous or are declared under an incorrect hazard class.

We also include cases where the hazard is declared but packaging, quantity, or segregation requirements are inconsistent with the declaration, because these still create safety risk.

The practical objective is to rank containers by risk and provide explanations so that limited inspection capacity is applied where it matters most.

Threat actors include intentional misdeclaration to avoid fees or scrutiny, accidental misdeclaration due to poor classification, and third-party tampering during transshipment.

The framework assumes strict latency limits, sparse and delayed labels, and continuous drift in commodities and routes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Modalities and Data Sources

The imaging modality can be X-ray or gamma radiography produced by common NII scanners used at ports and border crossings [

3,

5].

When dual-energy imaging is available, the system can derive effective atomic number cues that help distinguish organics, metals, and mixed loads.

Optional modalities can include neutron-based inspection for material identification and muon tomography for dense object localization, but these are treated as enhancements rather than requirements.

The document modality includes bill of lading text, manifest lines, booking descriptions, HS codes, declared weights and volumes, route legs, transshipment metadata, and shipper-consignee history.

The system benefits from structured dangerous goods fields when present, including UN numbers, hazard classes, packing groups, and limited quantity flags.

4.2. Imaging Preprocessing

Raw radiographs are normalized using scanner calibration parameters, and scan artifacts are reduced with de-striping and noise suppression suitable for low-dose images.

Images are tiled into patches to support both local anomaly localization and global container embeddings.

When multiple views are available, the model treats them as a set and uses attention pooling to build a single container representation.

4.3. Document Preprocessing

Text is normalized to resolve spelling variants and common abbreviations, because booking descriptions are often short and noisy.

Named entity recognition extracts commodity mentions, chemical names, battery indicators, packing keywords, and temperature-control markers.

A consistency layer computes features such as description specificity, HS–keyword mismatch, and weight–volume plausibility relative to claimed goods.

4.4. Vision Encoder

The vision encoder is a CNN or ViT backbone trained to produce density-aware embeddings.

Self-supervised pretraining is recommended because labeled hazardous examples are rare, and anomaly objectives can generalize across commodities [

8].

An auxiliary head produces a saliency map that highlights regions that contributed most to the risk score.

4.5. Text Encoder

The text encoder is a transformer that produces embeddings for extracted claims and for raw description context.

An auxiliary head estimates a document inconsistency score and preserves provenance so the system can point to the exact phrase that drove an alert.

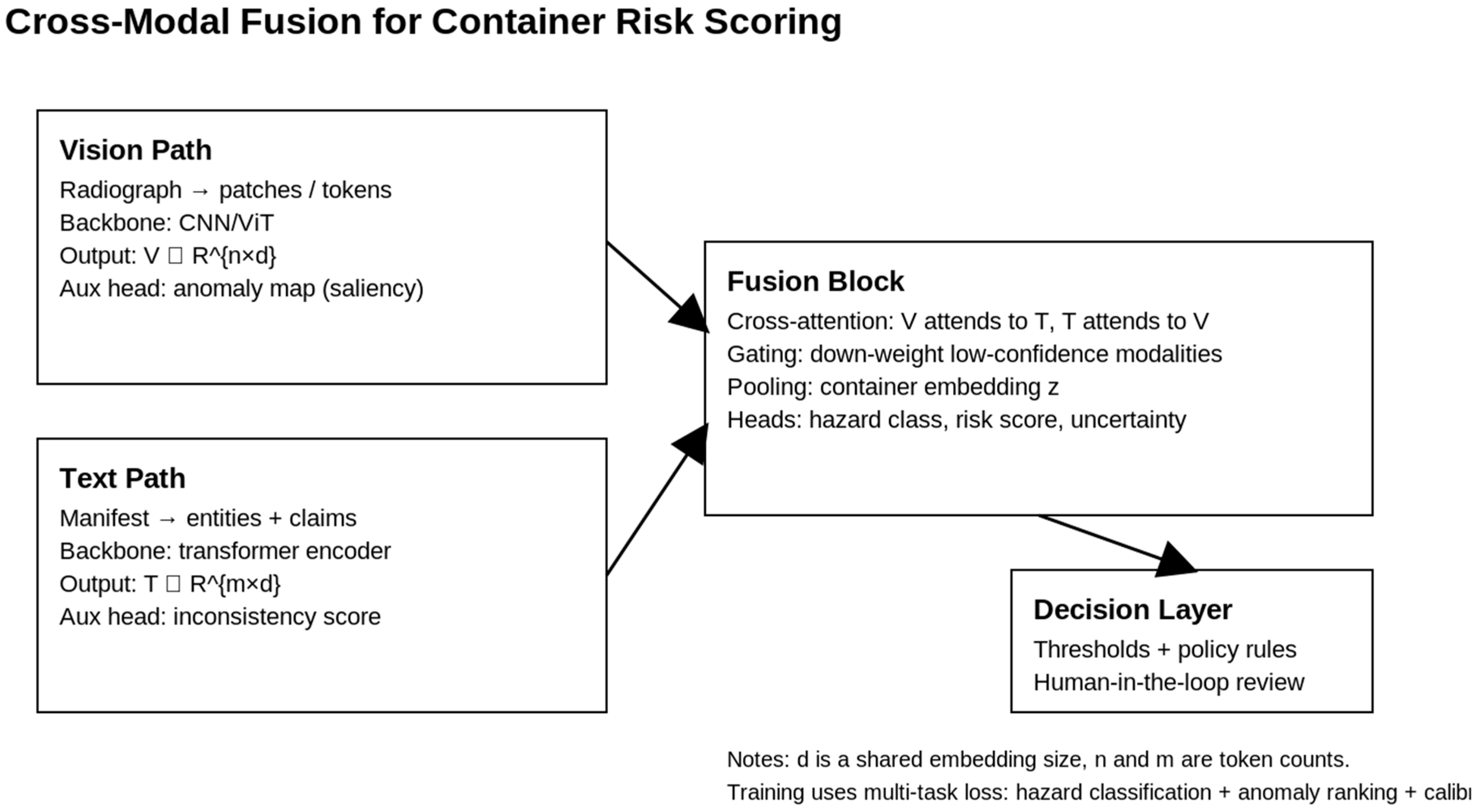

4.6. Fusion and Risk Scoring

Fusion is performed using cross-attention so that visual tokens can attend to textual claims and vice versa.

The system outputs a container risk score, a hazard-class distribution, and an uncertainty estimate.

Uncertainty is used to control escalation rules, because uncertain cases should defer to human review rather than silently deciding.

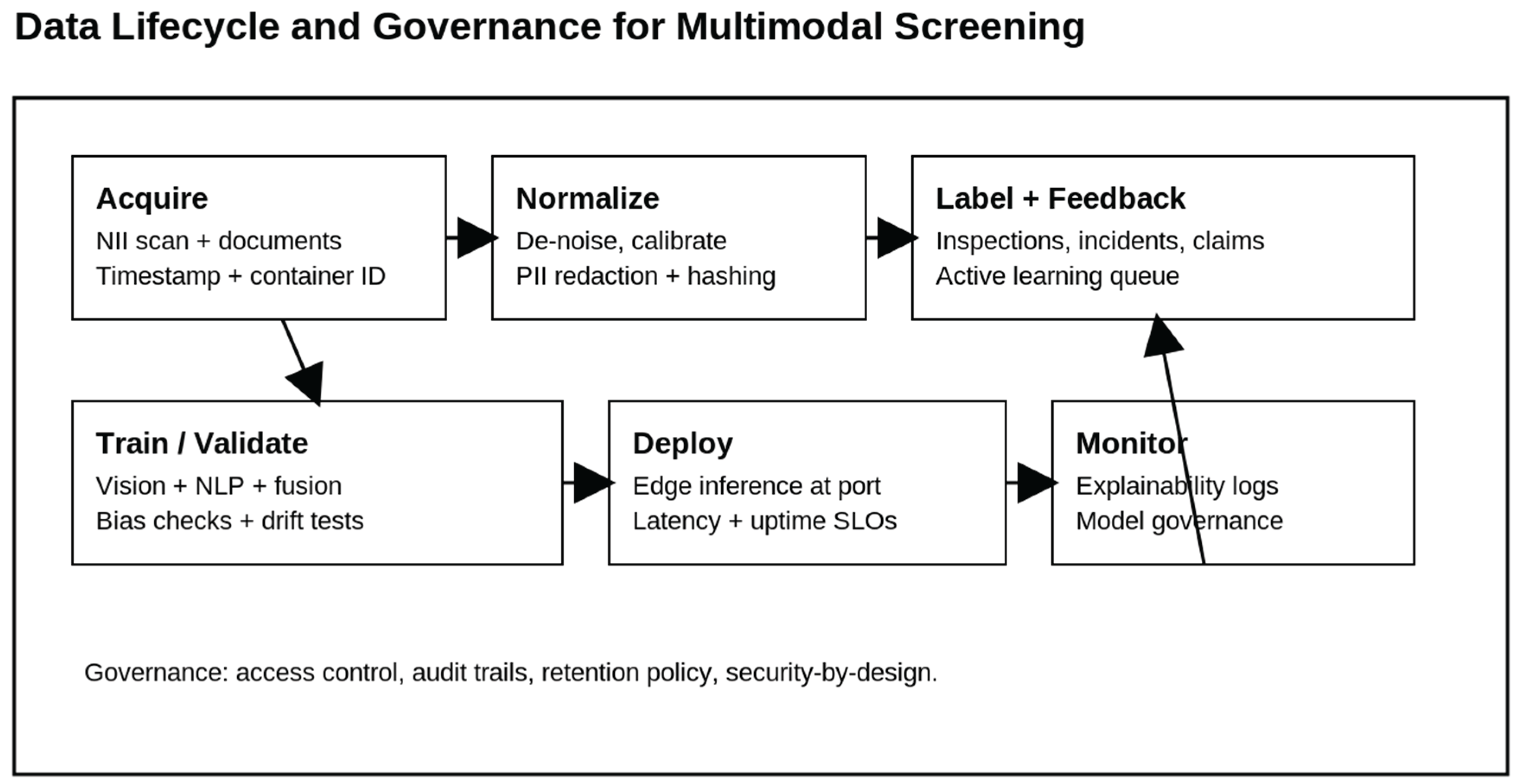

Figure 2.

Data lifecycle that treats labeling, feedback, and governance as first-class parts of a multimodal screening system.

Figure 2.

Data lifecycle that treats labeling, feedback, and governance as first-class parts of a multimodal screening system.

Figure 3.

Cross-modal fusion model that checks scan signals against document claims to produce a calibrated risk score and explainability artifacts.

Figure 3.

Cross-modal fusion model that checks scan signals against document claims to produce a calibrated risk score and explainability artifacts.

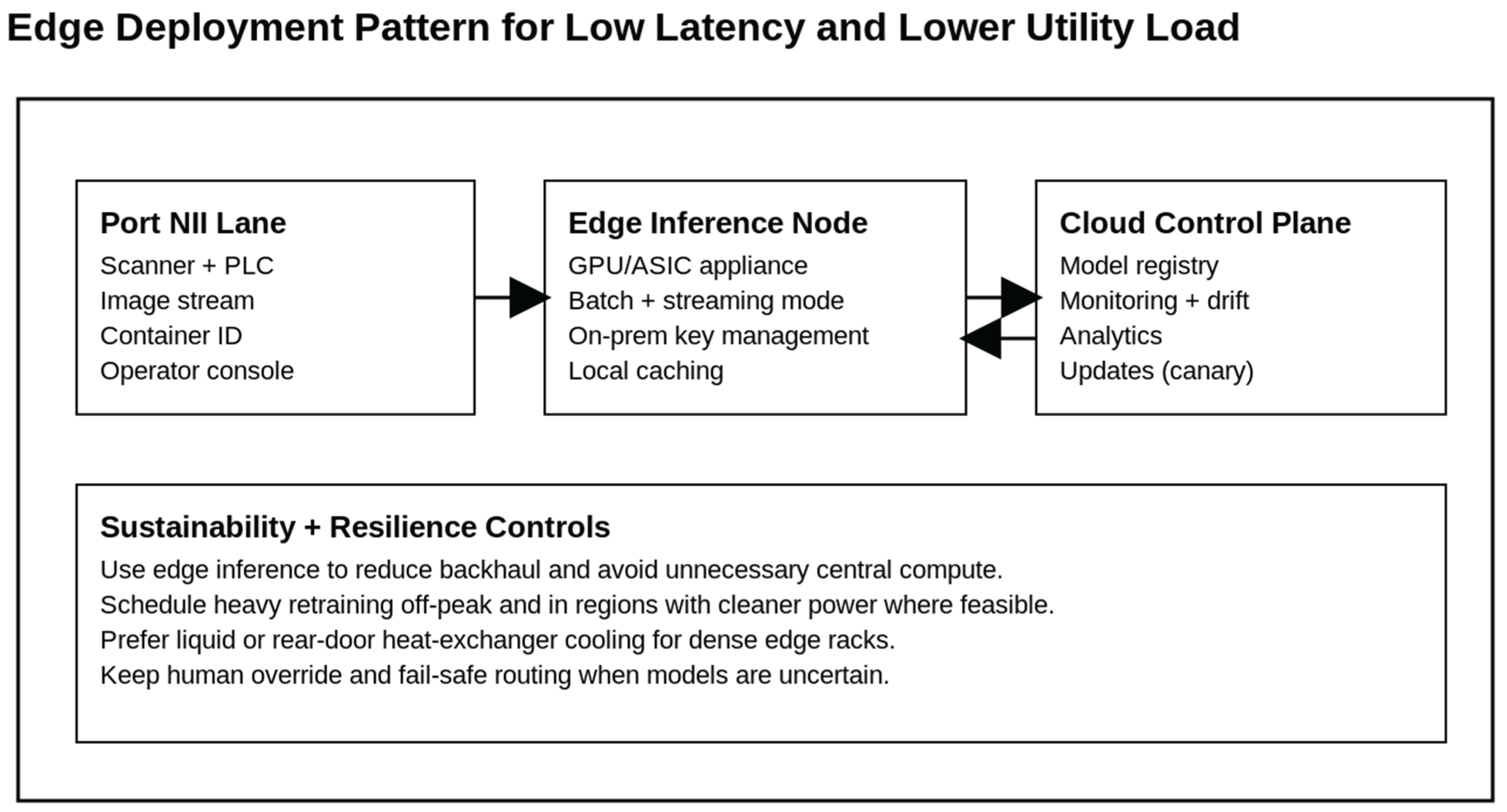

5. Deployment, Latency, and Utility Constraints

Ports and nearby cities face infrastructure constraints, including power availability and water constraints that affect cooling and expansion planning.

For this reason, the framework assumes most inference happens at the edge, close to scanners and operator consoles, rather than in distant centralized data centers.

Edge inference reduces end-to-end latency by avoiding long network paths, and it reduces backhaul bandwidth costs for high-resolution imaging streams.

The cloud still plays a role as a control plane for model versioning, monitoring, and analytics, but it does not need to process every container in real time.

This division aligns with DHS guidance that highlights integrating AI into screening workflows while respecting operational constraints [

3].

Figure 4.

Edge deployment pattern that prioritizes low latency, resilience, and reduced unnecessary centralized compute.

Figure 4.

Edge deployment pattern that prioritizes low latency, resilience, and reduced unnecessary centralized compute.

6. Experimental Design and Evaluation Plan

A credible evaluation for hazardous misdeclared cargo must reflect that true hazardous cases are rare, inspection resources are limited, and labels are delayed.

The evaluation plan uses three dataset tiers: synthetic radiographs for controlled hazard injection, de-identified operational scans with inspection labels, and carrier document data with audit and incident-derived labels.

Baselines include unimodal imaging anomaly detection, unimodal text risk scoring, and late-fusion ensembles, with comparisons to strong self-supervised cargo anomaly methods when available [

8].

The primary metric is recall at fixed false-alarm rates, because ports operate with a finite secondary inspection budget and need predictable workload.

Secondary metrics include precision–recall AUC, calibration error for uncertainty estimates, and time-to-decision for routing.

7. Discussion and Limitations

Fusion is a good fit for misdeclaration because the defining signal is mismatch between physical reality and declared description.

Radiography provides strong shape and density cues, but it may not uniquely identify chemical composition in all cases, especially for dense mixed loads.

Documents can be missing, delayed, or intentionally vague, and HS codes may be assigned at a coarse level, so document signals must be treated as probabilistic.

A staged adoption path that starts in shadow mode, then moves to assisted triage with clear thresholds, is a practical way to build trust.

8. Conclusions

Hazardous misdeclaration in maritime containers is a safety issue that can be reduced by connecting the signals that already exist in ports and carrier systems.

This paper presented a modular multimodal framework that fuses non-intrusive inspection imaging with shipping document intelligence to produce calibrated container risk scores with explanations.

The approach aligns with DHS guidance on AI-enabled paradigms for non-intrusive screening and with emerging industry adoption of AI screening for dangerous goods [

1,

3].

Future work should focus on partner-driven field trials and releasing open synthetic benchmarks that enable comparison without exposing sensitive operational data.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- World Shipping Council. World Shipping Council Launches Industry-First Cargo Safety Program to Prevent Ship Fires. 15 September 2025. Available online: https://www.worldshipping.org/news/world-shipping-council-launches-industry-first-cargo-safety-program-to-prevent-ship-fires (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Financial Times. Shipping Industry Enlists AI to Tackle Rising Number of Cargo Fires. 15 September 2025. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/8e9c70f1-af80-4e9b-8171-59b1ad54aaf6 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. AI-Enabled Paradigms for Non-Intrusive Screening. February 2025. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2025-02/25_0211_st_ai-enabled_paradigms_for_non-intrusive_screening.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- World Shipping Council. Cargo Safety Program. Available online: https://www.worldshipping.org/cargosafetyprogram (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Jaccard, N.; Wastell, D.; et al. Tackling the X-ray Cargo Inspection Challenge Using Machine Learning. Proc. SPIE 9844, 2016. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1502135/1/NJ_TWR_SPIE.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Rogers, T.W.; Jaccard, N.; et al. Automated X-ray Image Analysis for Cargo Security: Critical Review and Future Promise. 2016. Available online: https://ar5iv.labs.arxiv.org/html/1608.01017 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Andrews, J.T.A.; Morton, E.J.; Griffin, L.D. Representation-Learning for Anomaly Detection in Complex X-ray Cargo Imagery. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316613573_Representation-learning_for_anomaly_detection_in_complex-x-ray_cargo_imagery (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Gaikwad, B.; Patra, A.; Crawford, C.R.; Miller, E.L. Self-Supervised Anomaly Detection and Localization for X-ray Cargo Images: Generalization to Novel Anomalies. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2025, 140, 109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Deng, H.; Zhang, G. A Contraband Detection Scheme in X-ray Security Images Based on Improved YOLOv8s Network Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, C.; et al. Machine Learning for Detection of Trade in Strategic Goods: An Approach to Support Future Customs Enforcement and Outreach. World Customs Journal. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldcustomsjournal.org/api/v1/articles/116422-machine-learning-for-detection-of-trade-in-strategic-goods-an-approach-to-support-future-customs-enforcement-and-outreach.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Spitsakova, M.; Haav, H.-M. Using Machine Learning for Automated Assessment of Misclassification of Goods for Fraud Detection. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343580788_Using_Machine_Learning_for_Automated_Assessment_of_Misclassification_of_Goods_for_Fraud_Detection (accessed on 21 December 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).