Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Comparative Proteomic Analysis

2.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes In the hippocampal samples

| Functions | Proteins | Key references supporting functions |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis & metabolic enzymes | Ldha, Ldhb, Aldoa, Eno1, Eno2, Eno3, Pgam1, Tpi1, LOC500959, RGD1565368, Mdh1 | [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] |

| Mitochondrial ATP production & heme metabolism | Atp5b, Abcb6 | [33,34] |

| Proton transport & pH regulation | Atp6v1a, Atp6v1b2, Car2 | [35,36,37] |

| Cytoskeleton structure, dynamics & axon guidance | Tubb5, Tubb2a, Tubb2c, Tubb3, Capzb, Wdr1, Dpysl2, Dpysl3 | [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Vesicle trafficking, GPCR signaling and neurotransmission | Nsf, Gnb1, Gnb3, Pla2g4c | [46,47,48,49] |

| Cell signaling regulators | Mapk1, Pebp1, Ywhag, Cdca7l | [50,51,52,53] |

| Stress response, neuroprotection & glial structure | Park7, Gfap | [54,55] |

| GABA metabolism | Aldh5a1 | [56] |

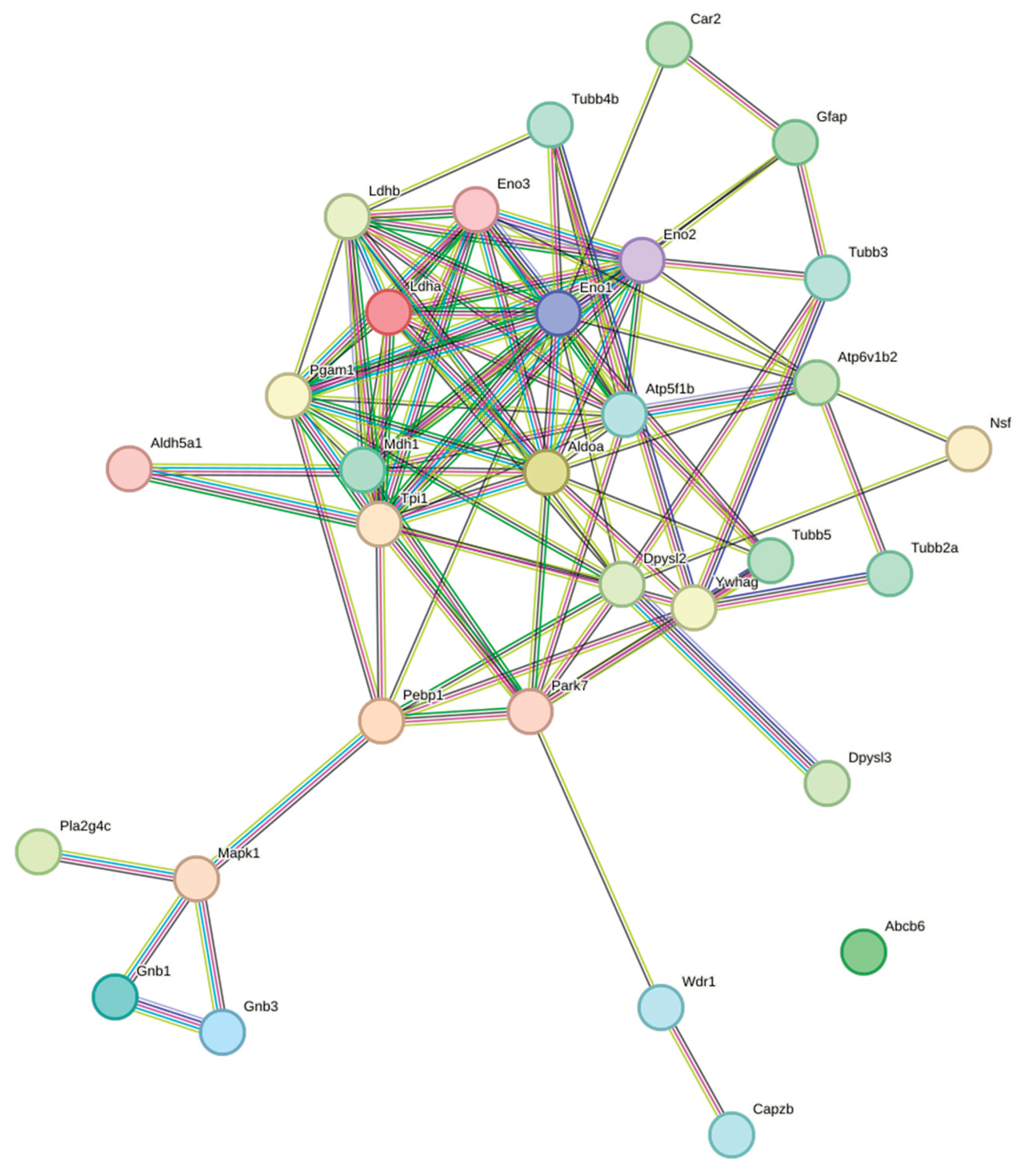

- Ldha ↔ Ldhb (score: 0.99)

- Pgam1 ↔ Eno1 (score: 0.99)

- Tpi1 ↔ Aldoa (score: 0.989)

- Eno1 ↔ Aldoa (score: 0.973)

- Wdr1 ↔ Capzb (score: 0.929)

- Tubb3 ↔ Gfap (score: 0.849)

- Atp5f1b ↔ Atp6v1b2 (score: 0.96)

- Dpysl2 ↔ Dpysl3 (score: 0.904)

- G-Protein Signaling—Connected module:

- Gnb1 ↔ Gnb3 (score: 0.811)

- Mapk1 interactions with Gnb1 and Gnb3

3. Discussion

- Glycolytic enzymes hub—central to seizure-induced metabolic crisis

- 2.

- Cytoskeletal module (Wdr1–Capzb, Tubb3–Gfap)—loss of dendritic spine and epileptogenesis

- 3.

- Interaction of ATP synthase ↔ V-ATPase (Atp5f1b ↔ Atp6v1b2)—ionic homeostasis and acidosis

- 4.

- CRMP family (Dpysl2 ↔ Dpysl3)—axonal sprouting and network reorganization

- 5.

- The G-protein/MAPK1 signaling node: control of inhibitory tone and excitability

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- allosteric modulators of Gβγ signalling [89],

- (d)

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Pilocarpine Protocol

4.3. Groups

4.1. Sample Preparation

4.2. Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis (2-DE)

4.3. Image Analysis for Proteome Determination

4.4. In-Gel Digestion

4.5. Nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis

4.6. Interactome

4.7. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beghi, E. The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology 2019, 54, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Pfander, M.; Arnold, S.; Henkel, A.; Weil, S.; Noachtar, S. Clinical features and EEG findings differentiating mesial from neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2002, 4, 189–195.

- Tatum, W. O. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 29, 356–365. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. V.; Shinnar, S.; Hesdorffer, D. C.; Bagiella, E.; Bello, J. A.; Chan, S.; Xu, Y.; MacFall, J.; Gomes, W. A.; Moshé, S. L.; Mathern, G. W.; Pellock, J. M.; Nordli, D. R.; Frank, L. M.; Provenzale, J.; Shinnar, R. C.; Epstein, L. G.; Masur, D.; Litherland, C.; Sun, S.; FEBSTAT Study Team. Hippocampal sclerosis after febrile status epilepticus: the FEBSTAT study. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 178–185. [CrossRef]

- Blumcke, I.; Spreafico, R.; Haaker, G.; Coras, R.; Kobow, K.; Bien, C. G.; Schramm, J.; et al. Histopathological findings in brain tissue obtained during epilepsy surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1648–1656. [CrossRef]

- Bruxel, E. M.; do Canto, A. M.; Bruno, D. C. F.; Geraldis, J. C.; Lopes-Cendes, I. Multi-omic strategies applied to the study of pharmacoresistance in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia Open 2021, e12536. [CrossRef]

- Houser, C. R. Granule cell dispersion in the dentate gyrus of humans with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 1990, 535, 195–204. [CrossRef]

- Chipaux, M.; Szurhaj, W.; Vercueil, L.; Milh, M.; Villeneuve, N.; Cances, C.; Auvin, S.; Chassagnon, S.; Napuri, S.; Allaire, C.; Derambure, P.; Marchal, C.; Caubel, I.; Ricard-Mousnier, B.; N’Guyen The Tich, S.; Pinard, J. M.; Bahi-Buisson, N.; de Baracé, C.; Kahane, P.; Gautier, A.; Hamelin, S.; Coste-Zeitoun, D.; Rosenberg, S. D.; Clerson, P.; Nabbout, R.; Kuchenbuch, M.; Picot, M. C.; Kaminska, A. Epilepsy diagnostic and treatment needs identified with a collaborative database involving tertiary centers in France. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 757–769. [CrossRef]

- Canto, A. M.; Godoi, A. B.; Matos, A. H. B.; Geraldis, J. C.; Rogerio, F.; Alvim, M. K. M.; Yasuda, C. L.; Ghizoni, E.; Tedeschi, H.; Veiga, D. F. T.; Henning, B.; Souza, W.; Rocha, C. S.; Vieira, A. S.; Dias, E. V.; Carvalho, B. S.; Gilioli, R.; Arul, A. B.; Robinson, R. A. S.; Cendes, F.; Lopes-Cendes, I. Benchmarking the proteomic profile of animal models of mesial temporal epilepsy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 454–467. [CrossRef]

- Kwan, P.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Berg, A. T.; Brodie, M. J.; Allen Hauser, W.; Mathern, G.; Moshé, S. L.; Perucca, E.; Wiebe, S.; French, J. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1069–1077. [CrossRef]

- Temkin, N. R. Preventing and treating posttraumatic seizures: the human experience. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 10–13. [CrossRef]

- Mus-Veteau, I. Heterologous expression and purification systems for structural proteomics of mammalian membrane proteins. Comp. Funct. Genomics 2002, 3, 511–517. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Y.; Smith, P.; Murphy, M.; Cook, M. Global expression profiling in epileptogenesis: does it add to the confusion? Brain Pathol. 2010, 20, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Alzate, O. Neuroproteomics. In Neuroproteomics; Alzate, O., Ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, 2010; Chapter 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56022/.

- Banote, R. K.; Larsson, D.; Berger, E.; Kumlien, E.; Zelano, J. Quantitative proteomic analysis to identify differentially expressed proteins in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2021, 174, 106674. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Basit, M.; Nisar, M. A.; Khurshid, M.; Rasool, M. H. Proteomics: technologies and their applications. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2017, 55, 182–196. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wen, F.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Wei, Y. Q. A review of current applications of mass spectrometry for neuroproteomics in epilepsy. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2010, 29, 197–246. [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, E. A.; Leite, J. P.; Bortolotto, Z. A.; Turski, W. A.; Ikonomidou, C.; Turski, L. Long-term effects of pilocarpine in rats: structural damage of the brain triggers kindling and spontaneously recurrent seizures. Epilepsia 1991, 32, 778–782. [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, E. A.; Fernandes, M. J.; Turski, L.; Naffah-Mazzacoratti, M. G. Spontaneous recurrent seizures in rats: amino acid and monoamine determination in the hippocampus. Epilepsia 1994, 35, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ari, Y. Limbic seizures and brain damage produced by kainic acid: mechanisms and relevance to human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 1985, 14, 375–403. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. V.; Cabral, F. R. Ictogênese, epileptogênese e mecanismo de ação das drogas na profilaxia e tratamento da epilepsia. J. Epilepsy Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 14, 39–45. ISSN 1676-2649.

- STRING: Functional Protein Association Networks. Available online: https://string-db.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Vander Heiden, M. G.; Cantley, L. C.; Thompson, C. B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [CrossRef]

- Markert, C. L.; Shaklee, J. B.; Whitt, G. S. Evolution of a gene. Multiple genes for LDH isozymes provide a model of the evolution of gene structure, function and regulation. Science 1975, 189, 102–114. [CrossRef]

- Penhoet, E. E.; Kochman, M.; Rutter, W. J. Molecular and catalytic properties of aldolase C. Biochemistry 1969, 8, 4396–4402. [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, V. Multifunctional α-enolase: its role in diseases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001, 65, 710–725.

- Hattori, M.; et al. [Title]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 5198–5202.

- Marangos, P. J.; Schmechel, D. E.; Brightman, M. W. Glycolytic enzymes in synaptosomal and mitochondrial fractions: evidence for functional compartmentation. J. Neurochem. 1978, 30, 1657–1665.

- Hitosugi, T.; Zhou, L.; Elf, S.; Fan, J.; et al. Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 coordinates glycolysis and biosynthesis to promote tumor growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 345–352. [CrossRef]

- Orosz, F.; Gergely, J.; Kovács, L. Triose-phosphate isomerase: a critical enzyme in glycolysis. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006, 91, 281–311.

- Sirover, M. A. New insights into an old protein: the functional diversity of mammalian glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1810, 741–751.

- Minárik, P.; Tomášková, N.; Kollárová, M.; Antal, P. Malate dehydrogenases—structure and function. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2002, 21, 257–265.

- Walker, J. E. The ATP synthase: the understood, the uncertain and the unknown. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 551–575.

- Krishnamurthy, P. C.; Du, G.; Fukuda, Y.; Sun, D.; Sampath, J.; Mercer, K. E.; Wang, J.; Sosa-Pineda, B.; Murti, K. G.; Schuetz, J. D. Identification of a mammalian mitochondrial porphyrin transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 11403–11408. [CrossRef]

- Forgac, M. Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 917–929. [CrossRef]

- Nishi, T.; Forgac, M. The vacuolar (H+)-ATPases—nature’s most versatile proton pumps. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Lindskog, S. Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 74, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Luduena, R. F. Multiple forms of tubulin: different gene products and covalent modifications. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1998, 178, 207–275.

- Tischfield, M. A.; et al. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. Cell 2010, 140, 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Breuss, M.; Heng, J. I. T.; Poirier, K.; et al. Mutations in the β-tubulin gene TUBB5 cause microcephaly with structural brain abnormalities. Neuron 2012, 75, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Katsetos, C. D.; Dráberová, E.; Legido, A.; et al. Tubulins in the central and peripheral nervous system: clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic implications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 196, 195–214. [CrossRef]

- Wear, M. A.; Yamashita, A.; Kim, K.; Maéda, Y.; Cooper, J. A. How capping protein binds the barbed end of the actin filament. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 149, 541–554.

- Okada, K.; Obinata, T.; Abe, H. XAIP1: a Xenopus homologue of yeast actin-interacting protein 1, involved in actin filament dynamics. Cell 1999, 99, 533–545.

- Cole, A. R.; Knebel, A.; Morrice, N. A.; et al. GSK-3 phosphorylation of the Alzheimer epitope within collapsin response mediator proteins regulates axon elongation. Neuron 2004, 44, 821–835. [CrossRef]

- Minturn, J. E.; Fryer, H. J. L.; Geschwind, D. H.; Hockfield, S. TOAD-64, a protein expressed early in neuronal differentiation, is related to unc-33, a C. elegans gene involved in axonal outgrowth. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 6757–6766. [CrossRef]

- Whiteheart, S. W.; Schraw, T.; Matveeva, E. A. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) structure and function. Nature 1994, 370, 530–535.

- Clapham, D. E.; Neer, E. J. G protein βγ subunits. Nature 1997, 389, 467–469. [CrossRef]

- Siffert, W.; Rosskopf, D.; Siffert, G.; Busch, S.; Moritz, A.; Erbel, R.; Sharma, A. M.; Ritz, E.; Wichmann, H. E.; Jakobs, K. H.; Horsthemke, B. Association of a human G-protein β3 subunit variant with hypertension. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 45–48. [CrossRef]

- Pickard, R. T.; Strifler, B. A.; Kramer, R. M.; Sharp, J. D. Molecular cloning of a novel human cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 8823–8831. [CrossRef]

- Shaul, Y. D.; Seger, R. The MEK/ERK cascade: from signaling specificity to diverse functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 465–480. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K.; Janosch, P.; McFerran, B.; Rose, D. W.; Mischak, H.; Sedivy, J. M.; Kolch, W. Mechanism of suppression of the Raf/MEK/extracellular signal–regulated kinase pathway by the Raf kinase inhibitor protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999, 1, 72–78.

- Aitken, A. 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996, 21, 415–417.

- Osthus, R. C.; Karim, B.; Prescott, J. E.; Smith, B. D.; McDevitt, M.; Huso, D. L.; Dang, C. V. The Myc target gene JPO1/CDCA7 is essential for neoplastic transformation by Myc. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 4870–4880.

- Zhou, W.; Zhu, M.; Wilson, M. A.; Petsko, G. A.; Fink, A. L. The oxidation state of DJ-1 regulates its chaperone activity toward α-synuclein. Cell 2006, 127, 321–332. [CrossRef]

- Eng, L. F.; Ghirnikar, R. S.; Lee, Y. L. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: GFAP-thirty-one years (1969–2000). J. Neuroimmunol. 2000, 111, 15–28.

- Chambliss, K. L.; Gibson, K. M. Disorders of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1992, 15, 495–513. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D. M.; Vogel, H. J.; Hokin, L. E. Metabolic Pathways: Energetics, Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle, and Carbohydrates, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967; ISBN 9780122992513.

- Masino, S. A.; Kawamura, M. Jr.; Wasser, C. D.; Pomeroy, L. T.; Ruskin, D. N. Adenosine, ketogenic diet and epilepsy: the emerging therapeutic relationship between metabolism and brain activity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009, 7, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Martins-de-Souza, D.; Gattaz, W. F.; Schmitt, A.; Novello, J. C.; Marangoni, S.; Turck, C. W.; Dias-Neto, E.; Harris, L. W.; Guest, P. C.; Bahn, S. Proteome analysis of schizophrenia patients’ Wernicke’s area reveals an energy metabolism dysregulation. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 17. [CrossRef]

- Ross, B. M.; Eder, K.; Moszczynska, A.; Mamalias, N.; Lamarche, J.; Ang, L.; Pandolfo, M.; Rouleau, G.; Kirchgessner, M.; Kish, S. J. Abnormal activity of membrane phospholipid synthetic enzymes in neurological disorders. J. Neurochem. 1997, 68, 675–683. [CrossRef]

- Adibhatla, R. M.; Hatcher, J. F. Altered lipid metabolism in brain injury and disorders. Subcell. Biochem. 2008, 49, 241–268.

- Talib, L. L.; Yassuda, M. S.; Diniz, B. S.; Forlenza, O. V.; Gattaz, W. F. Cognitive training increases platelet phospholipase A2 activity in healthy elderly subjects. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008, 4(4 Suppl.), P3-349.

- Neves, S. R.; Ram, P. T.; Iyengar, R. G protein pathways. Science 2002, 296, 1636–1639. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Carneiro, J. E.; Persike, D. S.; Litzahn, J. J.; Cassel, J.-C.; Nehlig, A.; Fernandes, M. J. d. S. Hippocampal proteome of rats subjected to the Li-pilocarpine epilepsy model and the effect of carisbamate treatment. Pharmaceuticals2017, 10(3), 67. [CrossRef]

- During, M. J.; Spencer, D. D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 1993, 33, 444–451. [CrossRef]

- Sada, N.; Lee, S.; Katsu, T.; Otsuki, T.; Inoue, T. Epilepsy treatment. Neuron 2015, 86, 1364–1371. [CrossRef]

- Menard, L.; Hentschke, M.; Halley, P.; Hartmann, M. N.; Zuber, M.; Rossier, J.; Walther, S.; Vogt, K.; Schwab, M.; Seifritz, E.; et al. Developmental switch of the hippocampal GABAergic system and its impact on adult behavior. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4999. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Nelson, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Kang, H.; Cho, Y.; Park, H.; Lee, J. M.; Ha, S. Y.; Choi, J.; et al. Metabolic regulation of neuronal excitability through astrocyte–neuron lactate transport. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 517–528. [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Burger, R.; Votaw, J.; Zündorf, G.; Wagner, R. Regional cerebral blood flow and metabolism in epilepsy. Brain Res. 1995, 702, 149–155.

- Ross, J. M.; McCormack, S.; Dillin, A.; Rothman, J. E. Defective mitochondrial function and neuronal vulnerability in epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 11825–11837.

- Glier, C.; Shorvon, S.; Lee, D. Metabolic alterations in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 128–134.

- Stafstrom, C. E.; Rho, J. M. The ketogenic diet as a model of metabolic therapy in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 1087–1091. [CrossRef]

- Pontrello, C. G.; Gavornik, J. P.; Hu, J.; Greer, C. A. Regulation of neuronal excitability by astrocyte-derived factors. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 13060–13071.

- Zeng, L. H.; Rensing, N. R.; Wong, M.; Sun, X.; Kwon, C. H.; Baldwin, R.; Gambello, M. J.; Wong, M. The mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway mediates epileptogenesis in a model of tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 1070–1079.

- Nadkarni, A. V.; McIntosh, J. R. An efficient method for three-dimensional reconstruction of cellular organelles. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 130, 1429–1439.

- Oberheim, N. A.; Wang, X.; Goldman, S.; Nedergaard, M. Astrocytic complexity distinguishes the human brain. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 627–636. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.; Schilling, K.; Steinhäuser, C. Astrocyte dysfunction in neurological disorders: a molecular perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Somjen, G. G. Ion regulation in the brain: implications for epilepsy. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 1065–1096.

- Merkulova, M.; Dubovik, T.; Uvarov, P.; et al. Altered astrocytic signaling in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2018, 59, 96–107. [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.; Hentschke, M.; Buck, F.; et al. Metabolic control of neuronal excitability by astrocytes. Nat. Cell Biol.2021, 23, 123–133.

- Ziemann, A. E.; Allen, J. E.; Dahlem, T. J.; et al. Seizure-induced ATP depletion in neurons. Cell 2008, 134, 1063–1074. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. M.; Rodriguez, A.; Varela, M.; et al. Astrocyte-neuron metabolic interactions in epilepsy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7742. [CrossRef]

- Thiry, A.; Greco, C.; Vincent, M. Autocrine and paracrine signaling in neuronal metabolism. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 1518–1524.

- Yamashita, N.; Hori, T.; Kudo, Y.; et al. Astrocytic glutamate transporters and neuronal excitability. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 12169–12179.

- Brittain, J. M.; Chen, L.; Stephenson, A.; et al. GABA transporter regulation and seizure susceptibility. J. Neurosci.2011, 31, 15697–15707. [CrossRef]

- Niwa, M.; Fukuda, T.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Metabolic modulation of neuronal activity. J. Neurochem. 2017, 142, 798–813. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, N. A.; Reichenbach, A.; Pannasch, U. Astrocytic regulation of synaptic transmission. Neuropharmacology2018, 135, 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Bettler, B.; Kaupmann, K.; Mosbacher, J.; Gassmann, M. Molecular structure and function of GABA(B) receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 835–867. [CrossRef]

- Chalifoux, J. R.; Carter, A. G. GABA(B) receptor modulation of synaptic function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 63–87.

- Brooks-Kayal, A. R.; Shumate, M. D.; Jin, H.; Rikhter, T.; Dichter, M. A. Selective changes in GABA(A) receptor subunit expression in epilepsy. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 1166–1172.

- Sweatt, J. D. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004, 14, 311–317. [CrossRef]

- Pitkänen, A.; Lukasiuk, K. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis and potential treatment targets. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 173–186.

- Löscher, W. The pharmacology of anti-epileptic drugs revisited. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 367–382.

- Fredholm, B. B.; Dunwiddie, T. V.; Bergman, B.; Lindström, K. Levels of adenosine and adenine nucleotides in slices of rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1984, 295, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Turski, W. A.; Czuczwar, S. J.; Kleinrok, Z.; Turski, L. Cholinomimetics produce seizures and brain damage in rats. Experientia 1983, 39, 1408–1411. [CrossRef]

- Leite, J. P.; Cavalheiro, E. A. Effects of conventional antiepileptic drugs in a model of spontaneous recurrent seizures in rats. Epilepsy Res. 1995, 20, 93–104.

- Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Candiano, G.; Bruschi, M.; Musante, L.; Santucci, L.; Ghiggeri, G. M.; Carnemolla, B.; Orecchia, P.; Zardi, L.; Righetti, P. G. Blue silver: A very sensitive colloidal Coomassie G-250 staining for proteome analysis. Electrophoresis2004, 25, 1327–1333. [CrossRef]

| GeneCards | Protein name | Changes | IP | MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ldha | L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | ∅ | 5.5 | 36874 |

| Pebp1 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | ∅ | 5.2 | 20902 |

| Aldoa | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | ⇩ | 9.3 | 39783 |

| Pla2g4c | Cytosolic phospholipase A2 gamma (Fragment) | ⇩ | 5.2 | 37522 |

| Abcb6 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 6, mitochondrial | ⇩ | 9.3 | 93305,18 |

| Mdh1 | Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic | ⇩ | 6 | 36631 |

| Gnb1 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit beta-1 | ⇩ | 5.4 | 38151 |

| Gnb3 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit beta-3 | ⇩ | 5.3 | 38125 |

| Eno1 | Alpha-enolase |  |

6 | 47440 |

| - | Enolase |  |

10.3 | 34166 |

| Eno3 | Beta-enolase |  |

7.9 | 47326 |

| Eno2 | Gamma-enolase |  |

4.8 | 47510 |

| Aldh5a1 | Isoform Short of Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |  |

9.4 | 53391 |

| Park7 | Protein DJ-1 |  |

6.2 | 20190 |

| Mapk1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 |  |

6.5 | 41648 |

| Tpi1 | Triosephosphate isomerase |  |

7.9 | 27345 |

| Nsf | Vesicle-fusing ATPase |  |

6.5 | 83170 |

| Pgam1 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 |  |

6,6 | 28928 |

| Ywhag | 14-3-3 protein gamma |  |

4.6 | 28456 |

| Ldhb | L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain |  |

5.5 | 36874 |

| RGD1565368 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-like |  |

9.3 | 36045 |

| Dpysl2 | Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 |  |

5.8 | 62638 |

| Dpysl3 | Isoform 1 of Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 3 |  |

5.9 | 62327 |

| Atp6v1b2 | V-type proton ATPase subunit B, brain isoform |  |

5.4 | 56857 |

| Car2 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 |  |

6.9 | 29267 |

| Gfap | Isoform 1 of Glial fibrillary acidic protein |  |

5.1 | 49984 |

| Tubb5 | Isoform 1 of Tubulin beta-5 chain |  |

4.6 | 50095 |

| Tubb2a | Tubulin beta-2A chain |  |

4.6 | 50274 |

| Tubb2c | Tubulin beta-2C chain |  |

4.6 | 50225 |

| Tubb3 | Tubulin beta-3 chain |  |

4.6 | 50842 |

| Atp5b | ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial |  |

4.9 | 56318 |

| Tpi1 | Triosephosphate isomerase |  |

7.9 | 27345 |

| LOC500959 | Triosephosphate isomerase |  |

6.4 | 27306 |

| Capzb | F-actin-capping protein subunit beta |  |

5.4 | 30952 |

| Wdr1 | WD repeat-containing protein 1 |  |

6.1 | 66824 |

| Atp6v1a | V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunit A |  |

5.2 | 68564 |

| Cdca7l | Cell division cycle-associated 7-like protein (Cdca71) |  |

5.8 | 50854 |

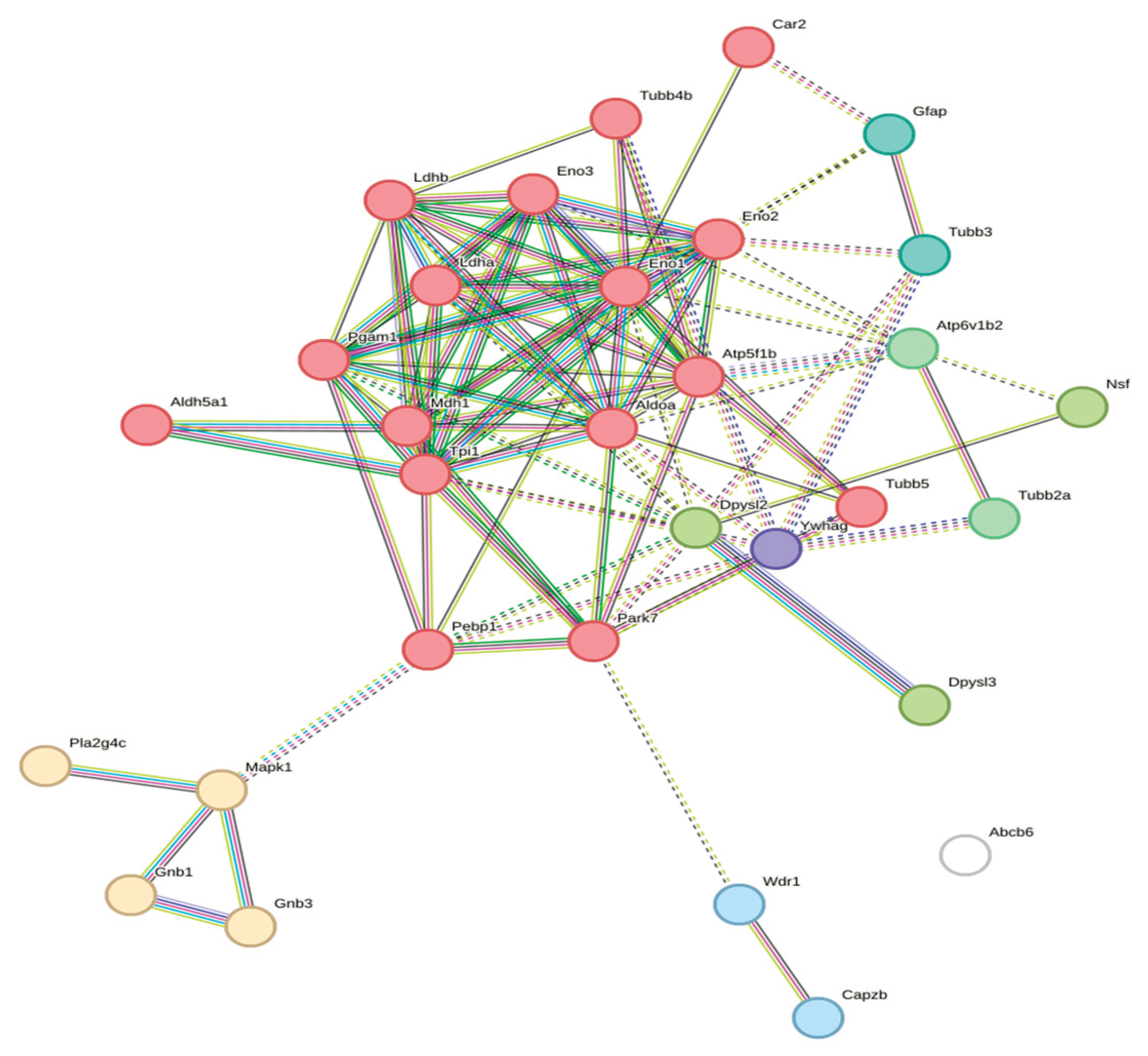

| Cluster | Proteins | Functional Annotation | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Red) | Pebp1, Pgam1, Eno1, Tpi1, Park7, Atp5f1b, Tubb5, Eno3, Tubb4b, Eno2, Ldha, Aldoa, Ldhb, Mdh1, Aldh5a1, Car2 | NAD Metabolism; Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 16 |

| 2 (Gold) | Mapk1, Gnb3, Gnb1, Pla2g4c | Thrombin Signaling; PAR Signaling | 4 |

| 3 (Olive) | Dpysl2, Nsf, Dpysl3 | CRMP in Sema3A Signaling; Hydantoinase | 3 |

| 4 (Green) | Atp6v1b2, Tubb2a | Vesicular Transport; Microtubules | 2 |

| 5 (Blue) | Tubb3, Gfap | Neuronal Cytoskeleton | 2 |

| 6 (Cyan) | Wdr1, Capzb | Actin Filament Regulation | 2 |

| 7 (Purple) | Ywhag | 14-3-3 Adaptor (Isolated) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).